In this closing chapter, Tu Weiming addresses two compelling forces influencing the dilemmas of the human condition, namely, globalization and localization in a similar way as discussed by Tehranian (Chapter 27). He makes explicit that globalization is not homogenization and paradoxically heightens and accentuates local awareness. It is his contention that we must take seriously the presence of primordial ties (e.g., race, ethnicity, gender, language, land, age, and faith) that make us concrete human beings in the process of globalization. He maintains that it is only through genuine dialogue as mutual learning that we will be able to achieve unity in diversity and build an integrated global community. For him, humanity, reciprocity, and trust constitute the common ground on which global ethics can be explored. He delineates four sets of fundamental ethical principles based on these four themes: (1) liberty/justice, (2) rationality/sympathy, (3) legality/civility, and (4) rights/responsibility. Tu concludes his superb essay by underlining the importance of the art of listening and face-to-face communication as indispensable ways of accessing the cumulative wisdom of the elders and learning to be fully human through character building.

As we move beyond the dichotomies of globalization and localization, developed and developing, capitalism and socialism, we become an increasingly interconnected global village. By transcending the assumed dichotomies of tradition and modernity, East and West, North and South and us and them, we can tap the rich and varied spiritual resources of our global community as we strive to understand the dilemmas of the human condition. At a minimum, we realize that the great religious traditions that had significantly contributed to the “Age of Reason”—the Enlightenment of the modern West—contain profound meaning for shaping the lives of people throughout the world. Christianity, Judaism, Islam and Greek philosophy are and will remain major founts of wisdom for centuries to come. Other ways of life, notably Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism, are also equally vibrant in the contemporary world and will most likely continue to flourish in the future. Moreover, scholars as well as policy makers have recognized that indigenous forms of spirituality—such as African, Shinto, Maori, Polynesian, Native American, Inuit, Mesoamerican, Andean and Hawaiian—are also sources of inspiration for the global village.

Western, non-Western and indigenous traditions are all immensely complex, each rich in fruitful ambiguity. Actually, the monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam) all originated from the East and symbolize an age-long process of substantial transformations. Similarly, the Hindu, Buddhist, Confucian and Daoist ways of life are each the unfolding of a spectacular spiritual vision involving fundamental insights, elaborate rituals, social institutions and daily practice. Our awareness of the richness and variety of the spiritual resources available to the global community enables us to rise above our hegemonic and exclusive arrogance and seek the advice, guidance and wisdom of other traditions. Furthermore, we also fully acknowledge the danger of inter- and intrareligious conflicts that seriously threaten the stability of local, national and regional communities, creating major challenges to cultivating hope worldwide. The need for a dialogue is obvious.

Globalization and the Human Condition

Accompanying the rapid globalization of the last decade was an increasingly heated debate over its merits and demerits. Globalization has produced new bodies of knowledge, falsified “self-evident” conventional truths and created myths and misperceptions of its own. Forces of globalization include the explosion in information and communications technologies, rapid expansion of the market economy, dramatic demographic change, relentless urbanization throughout the world and the trend toward more open societies. In the economic sphere, private capital in direct investments and portfolio funds has grown rapidly, the reduction of tariff barriers has become a pervasive worldwide phenomenon, the demand for transparency of financial institutions is increasing, and concerns about corruption are spreading.

These by-products of economic globalization have exerted great pressure on governments to become more publicly accountable, thus creating new possibilities for democratization. As a result, civil societies, symbolized by the formation of transnational NGOs, have emerged as important actors in national, regional and international politics. Surely, the idea that “the rising tide carries all boats” seems to be working. While the rich are getting richer, the poor are not necessarily becoming poorer. Some countries that have opened their economies, reduced tariff barriers and encouraged two-way foreign trade seem to have benefited from the new global situation. However, we recognize that open borders for goods do not yet apply sufficiently to agricultural products, a development that would be welcome, of course, and benefit the countries of the South. Already, in the last thirty years, some industrialized states and some developing countries have made strides in eradicating abject poverty in the direction of development and peace. It seems that we are moving from an old world of division and walls to a brave new world of connections and webs.

Yet, with 20 percent of the world’s population earning 75 percent of the income and 25 percent earning less than 2 percent, 31 percent illiterate, 80 percent living in substandard housing, more than a billion people living on less than a dollar a day and nearly a billion and a half people without access to clean water, the state of the world is far from encouraging. Furthermore, the widening gap between the haves and have-nots and the rampant commercialization and com-modification of social life, including the life of family, school and religious institution, undermine the civic solidarity of developing countries and threaten the moral fabric of societies in developed countries. Anxiety over the loss of cultural identity and the weakening of communal ties is widespread, and retreat to ethnic and other parochial loyalties has become an easy way of dealing with such anxieties. Can globalization lead us to a more promising land or will it generate more conflicts and contradictions in our already tension-ridden world? Is there a better way to manage globalization so that its blessings are spread more uniformly?

From Westernization and Modernization to Globalization

Globalization is an intensification of the process of human interaction involving travel, trade, migration, and dissemination of knowledge that have shaped the progress of the world over millennia.

Amartya Sen, The New York Review of Books, July 2000

Present-day globalization may well have to be seen in a larger historical perspective. The spread of Buddhism from Benares, Christianity from Jerusalem and Islam from Mecca are historic cases in point. Globalization was also seen in commercial, diplomatic and military empire-building. Indeed, the intercivilizational communication among missionaries, merchants, soldiers and diplomats in premodern times was instrumental in fostering proto-globalization long before the advent of the industrial and information revolutions. The fifteenth-century maritime exploration significantly contributed to bringing the world together into a single “system.” Similarly, colonialism and imperialism have brought once disparate peoples into close contact with each other. Western Europe has substantially reshaped human geography and left an indelible imprint on the global community.

Modernization theory, formulated in the 1950s in the United States, asserts that the “modernizing” process that began in the modern West was actually “global” in its transformative potential. The shift from the spatial idea of Westernization to the temporal concept of modernization is significant, suggesting that developments that first occurred in Western Europe, such as industrialization, cannot be conceived simply as “Western” because they were on their way to becoming Japanese, Russian, Chinese, Turkish, Indian, Kenyan, Brazilian and Iranian as well. This was precisely why the nongeographic idea of temporal modernization seemed to better capture the salient features of Westernization as a process of global transformation.

However, implicit in modernization theory was the assumption that development inevitably moves in the same direction as progress and, in the long run, the world will converge into one single civilization. Since the developed countries, notably the United States, were leading the way, modernization was seen as essentially Westernization and particularly Americanization. This narrative is, on the surface, very persuasive because the characteristics of modernity and the achievements of modernization, as defined by the theorists, are not merely Western or American inventions. Market economy, democratic polity, civil society and individual rights are arguably universal aspirations.

Events in recent decades clearly show that the competitive market has been a major engine for economic growth. They also show that democratization is widespread, that a vibrant civil society encourages active participation in the political process and that respect for the dignity of the individual is a necessary condition for social solidarity. These developments may have prompted several scholars to argue that there is no longer any major ideological divide in the world: Capitalism has triumphed, market economy and democratic polity are the waves of the future and “history” as we know it has ended.

Nevertheless, the euphoric expectation that the modernizing experience of one civilization would become the model for the rest of the world was short-lived. Samuel Huntington’s warning of the coming clash of civilizations was perhaps intended to show that as long as conflicting worldviews and value systems exist, no nation, no matter how powerful and wealthy, can impose her particular way upon others. In the twenty-first century, the most serious threats to international security will not be economic or political but cultural. At first blush, the “clash of civilizations” theory seems more persuasive than the “end of history” advocated by Francis Fukuyama, because it acknowledges that culture is important and that religious difference must be properly managed. Unfortunately, its underlying thesis is still “the West and the rest,” and it recommends a course of action that presumes that the West will eventually prevail over its adversaries.

Warnings about imminent civilizational conflict make a dialogue among civilizations not merely desirable, but necessary. Even the most positive definition of modernization—market economy, democratic polity, civil society and individual rights and responsibilities—allows room for debate and discussion about its feasibility. The free market evokes questions of governance; democracy can assume different practical forms; styles of civil society vary from culture to culture; and whether dignity must be predicated on the doctrine of individual rights has no easy answer. Modernization is neither Westernization nor Americanization. The fallacy of “the West and the rest,” like that of “us and them,” is its inability and unwillingness to transcend the “either-or” mentality. Globalization compels us to think otherwise.

Westernization and modernization are clearly antecedents of globalization, but between them is a quantum leap in terms of the rate of change and the depth of conceptual transformation. Information technology, the prime mover of economic development, has had far-reaching political, social and cultural implications. Although the promise that the “knowledge economy” can help poor countries leapfrog over seemingly intractable stages of development has yet to become a reality, information exchange at all levels has substantially increased throughout the world. Similarly, although geography still matters greatly in economic interchange and income distribution, new information and communications technologies have the potential to significantly change international income inequalities. An axiom of our age is that the lines of wealth, power and influence can be redrawn on the world map in such a way that the rules of the game themselves must be constantly revised. Especially noteworthy is the great emancipatory and destructive potential of emergent globalizing technologies. Robotic machines and computers can sequence the human genome, design drugs, manufacture new materials, alter genetic structures of animals and plants and even clone humans, thus empowering small groups of individuals to make profound positive and negative impacts on the larger society.

Conceptually, globalization is not a process of homogenization. For now, at least, the idea of convergence—meaning that the rest of the world will eventually follow a single model of development—is too simplistic to account for the complexity of globalizing trends. Surely, environmental degradation, disease, drug abuse and crime are as thoroughly internationalized as science, technology, trade, finance, tourism and migration. The world has never been so interconnected and interdependent. Yet, the emerging global village, far from being integrated, let alone formed according to a monolithic pattern, is characterized by diversity and, recently, by a movement towards assertiveness of one’s identity. The contemporary world is, therefore, an arena where the forces of globalization and its opposite—localization—are exerting tremendous pressure on individuals and groups.

Local Awareness, Primordial Ties and Identity

One important reason for this diversity and increased assertiveness of one’s identity is that globalization accentuates local awareness, consciousness, sensitivity, sentiment and passion. The resurfacing of strong attachments to “primordial ties” may not have been caused by globalizing trends, but it is likely to be one of their unintended consequences.

We cannot afford to ignore race, gender, language, land, class, age and faith in describing the current human condition. Racial discrimination threatens the solidarity of all multiethnic societies. If it is not properly handled, even powerful nations can become disunited. Gender equality has universal appeal. No society is immune to powerful women’s movements for fairness between the sexes. Linguistic conflicts have ripped apart otherwise stable communities in developed as well as in developing countries. The struggle for sovereignty is a pervasive phenomenon throughout the world. The membership of the United Nations would be expanded several times if all separate identities were to seek international recognition. The so-called North–South problem exists at all levels—international, regional, national and local. The disparity between urban and rural is widening in developing countries; urban poverty presents a major challenge to all developed countries. Generation gaps have become more frequent—the conventional way of defining a generation in terms of a thirty-year period is no longer adequate—and the struggle between generations more intense. Fissures among siblings are often caused by lifestyles influenced by different “generations” of music, movies, games and computers. Religious conflicts occur not only between two different faiths but also between divergent traditions of the same faith. Not infrequently, intrareligious disputes are more violent than interreligious ones.

In short, the seemingly intractable conditions, the “primordial ties,” that make us concrete living human beings, far from being eroded by globalization, have become particularly pronounced in recent decades.

Globalization may erode the authority of the state, and alter the meaning of sovereignty and nationality, but it increases the importance of identity. The more global our world becomes, the more vital the search for identification.

Elmer Johnson, President, Aspen Institute

Indeed, it is impractical to assume that we must abandon our primordial ties in order to become global citizens. Further, it is ill advised to consider them necessarily detrimental to the cosmopolitan spirit. We know that our strong feelings, lofty aspirations and recurring dreams are often attached to a particular group, expressed through a mother tongue, associated with a specific place and targeted to people of the same age and faith. We also notice that gender and class feature prominently in our self-definition. We are deeply rooted in our primordial ties, and they give meaning to our daily existence. They cannot be arbitrarily whisked away more than one could consciously choose to be a totally different person.

Since the fear that globalization as a hegemonic force will destroy the soul of an individual, group or nation is deeply experienced and vividly demonstrated by an increasing number of people—for example, riots in Seattle against the World Trade Organization in December 1999 and protests in Davos against the World Economic Forum in January 2000—we need to take seriously the presence of primordial ties in the globalizing process. Only by working with them, not merely as passive constraints but also as empowering resources, will we benefit from a fruitful interaction between active participation in global trends that are firmly anchored in local connectedness.

Realistically, primordial ties are neither frozen entities nor static structures. Surely, we are born with racial and gender characteristics, and we cannot choose our age cohort, place of birth, first language, country’s stage of economic development or faith community. Ethnicity and gender roles, however, are acquired through learning. Moreover, our awareness and consciousness of ethnic pride and the need for gender equality is the result of education. Our sensitivity, sentiment and the passion aroused by racial discrimination and gender inequality, no matter how strong and natural to us personally, are the results of socialization and require deliberate cultivation. This is also true with age, land, language, class and faith. They are all, under different circumstances and to varying degrees, culturally constructed social realities. In this sense, each primordial tie symbolizes a fluid and dynamic process. Like a flowing stream, it can be channeled to different directions.

While primordial ties give vibrant colors and a rich texture to the emerging global community, they also present serious challenges to the fragile world order and to human security. The United Nations, which arose from the cosmopolitan spirit of internationalism, is compelled to deal with issues of identity charged with explosive communal feelings. The pervasiveness of racial prejudice, gender bias, age discrimination, religious intolerance, cultural exclusivity, xenophobia, hate crimes and violence throughout the world makes it imperative that we understand in depth how globalization can enhance the feeling of personal identity without losing the sense of integrally belonging to the human family. Primordial ties are, of course, not a static notion.

We recognize that the concept of change is inherent in every culture and civilization, and that to a large extent, the fear of change is intertwined with the notion of enemy. We also recognize that civilizations have adapted to changes, so much so that they now share views on many issues.

Globalization has brought countries and civilizations increasingly closer to one another. More similarities and a host of fundamental common values are discovered in the course of convergence of civilizations. … The development of globalization will create broader space for the development of civilizations, each with its own unique characteristics.

Song Jian

Perhaps one of the most salient dimensions of globalization is economic globalization. It is often measured by aggregate growth, productivity rates and returns on capital investment. Other indicators, such as eradication of poverty, employment, health, life expectancy, education, social security, human rights and access to information and communication are essential to improve the quality of life. The idea of the stakeholder, rather than shareholder, can enable an ever-expanding network of people to participate in this potentially all-inclusive process. We may not be the beneficiaries of market economy, but we all have a stake in maintaining the quality of life of this earth.

Undeniably, global economic institutions can enhance the quality of life; they were established to favor financial stability and eventually to foster balanced economic growth. Obviously, there are apparent winners and losers in a competitive market, and the pervasiveness of the cultural and linguistic influence of a particular region in a given moment may be unavoidable. But, if globalization is perceived as the domination of the powerful either by design or by default, it will not be conducive to international stability. Since globalization is not homogenization, imagined or real hegemonism is detrimental to the cultivation of a culture of world peace. The Dialogue among Civilizations is intended to reverse this unintended negative consequence of globalization.

Dialogue as Mutual Learning

Ordinary human experience tells us that genuine dialogue is an art that requires careful nurturing. Unless we are intellectually, psychologically, mentally and spiritually well prepared, we are not in a position to engage ourselves fully in a dialogue. Actually, we can relish the joy of real communication only with true friends and like-minded souls.

How is it possible for strangers to leap across the so-called civilizational divide to take part in genuine dialogue, especially if the “partner” is perceived as the radical other, the adversary, the enemy? It seems simple minded to believe that it is not only possible, but realizable. Surely, it could take years or generations to completely realize the benefits of dialogical relationships at the personal, local, national and intercivilizational levels. At this time, we propose only minimum conditions as a turning point on the global scene.

Our urgency is dictated by our concerns for and anxieties about the sustainability of the environment and the life prospects of future generations. We strongly believe in the need for a new guardianship with a global common interest. We hope that, through dialogue among civilizations, we can encourage the positive forces of globalization that enhance material, moral, aesthetic and spiritual well-being, and take special care of those underprivileged, disadvantaged, marginalized and silenced by current trends of economic development. We also hope that, through dialogue among civilizations, we can foster the wholesome quests for personal knowledge, group solidarity, self-understanding and individual and communal identities.

We have learned from a variety of interreligious dialogues that tolerating difference is a prerequisite for any meaningful communication. Yet, merely being tolerant is too passive to transcend the narrow vision of the “frog in the well.” We need to be acutely aware of the presence of the other before we can actually begin communicating. Awareness of the presence of the other as a potential partner in conversation compels us to accept our coexistence as an undeniable fact. This leads to the recognition that the other’s role (belief, attitude and behavior) is relevant and significant to us. In other words, there is an intersection where the two of us are likely to meet to resolve divisive tension or to explore a joint venture. As the two sides have built enough trust to see each other face-to-face with reciprocal respect, the meeting becomes possible. Only then can a productive dialogue begin. Through dialogue, we can appreciate the value of learning from the other in the spirit of mutual reference. We may even celebrate the difference between us as the reason for expanding both of our horizons.

Dialogue, so conceived, is a tactic of neither persuasion nor conversion. It is to develop mutual understanding through sharing values and creating a new meaning of life together. As we approach civilizational dialogues, we need to suspend our desires to sell our ideas, to persuade others to accept our beliefs, to seek their approval of our opinions, to evaluate our course of action in order to gain agreement on what we cherish as true and to justify our deeply held convictions. Instead, our purpose is to learn what we do not know, to listen to different voices, to open ourselves up to multiple perspectives, to reflect on our own assumptions, to share insights, to discover areas of tacit agreement and to explore best practices for human flourishing. Only then can we establish mutually beneficial relationships based on reciprocity.

Diversity and Community

We need to remind ourselves, time and again, that neither the historical contingencies and the changing circumstances, nor the differences in color, ethnicity, language, educational background, cultural heritage and religious affiliation among us, mitigate against our common humanity. Our genetic codes clearly indicate that, by and large, we are made of the same stuff. The idea that we humans form one body not only with our fellow human beings but also with other animals, plants, trees and stones—“Heaven and earth and the myriad things”—expresses a cosmic vision as well a poetic sense of interconnectedness. We may even be able to trace all our ancestries to one source, if not to the African mother as proposed by some scholars. The African proverb that the earth is not only bequeathed to us by our ancestors but also entrusted to us by generations to come elegantly illustrates the undeniable fact that we have lived and will continue to live on this planet together.

While we affirm our common humanity, we are wary of faceless or abstract universalism. We are acutely aware that diversity is necessary for human flourishing. Just as biodiversity is essential for the survival of our planet, cultural and linguistic diversity is a defining characteristic of the human community as we know it. However, socially derived and culturally constructed perceptions of differences are used for setting individual against individual, group against group and majorities against minorities. The resultant discrimination yields to strife, violence and systematic violation of basic rights. While we celebrate diversity, we condemn ethnocentric and other exclusivist forms of chauvinism.

The space between faceless universalism and ethnocentric chauvinism is wide and open. This is the arena in which intercivilizational dialogues can take place. Great ethical and religious traditions have shaped the spiritual landscape of our world for millennia. Communication across ethnic, linguistic, religious and cultural divides has been a salient feature of human history. Despite tension and conflict between and among the divides, the general trend toward more contact and interaction across these divides has never diminished. Historically, each great ethical and religious tradition has encountered different belief systems and faith communities. Indeed, their vitality has often resulted from these encounters. By learning from others, the horizon of a given tradition became significantly broadened. For example, Christian theology benefited from Greek philosophy, Islamic thought was inspired by Persian literature and Chinese intellectual history was enriched by Indian ideas with the arrival of Buddhism in the first century.

Nevertheless, the fear of the other has also led to strife and prolonged struggle. So-called inter-religious wars are common throughout history. The peaceful interaction of two major civilizations, such as the Indian transformation of the Sinic cultural universe and the introduction, assimilation and incorporation of Mahayana Buddhist schools into the Chinese spiritual landscape, is rare. Since harmony among religions is essential for cultivating a culture of hope for the human family, interreligious dialogues are an integral part of the Dialogue among Civilizations. The opportunity for all religions, including emerging ones, to affirm unity of purpose for the promotion of the common public good is unprecedented in human history. More recently, globalization has substantially increased the density of interreligious communication.

The idea of the “common public good” is predicated on the advent of a global community. A global village, as an imagined virtual reality, is not a community. The term “community” ideally implies that people live together, share an ethos and a practicable civic ethic and are unified in their commitment to the common good. Such a unity of purpose, however, allows for diversity in lifestyles and differences in belief, so long as the diversity and differences do not infringe upon the fundamental freedoms and rights of others. Although we are far from realizing a true sense of community in the global village, we hope that global and local trends congenial to this development continue to accelerate, and that traditional and modern practices appropriate to it continue to spread.

As we reflect upon the past and meditate on the future we would want for our children, the question that looms large in our minds is: How can we embrace diversity by living responsibly—respectful of others’ traditions and yet faithful to our own—in the emerging global community? Real acceptance of diversity compels us to move beyond genuine tolerance to mutual respect and, eventually, to celebratory affirmation of one another. Ignorance and arrogance are the major roots of stereotyping, prejudice, hatred and violence in religious, cultural, racial and ethnic contexts. While physical security, economic sustenance and political stability provide the context for social integration, real community life emerges only if we are willing to walk across the divides and act responsibly and respectfully towards one another. Through dialogue, we learn to appreciate others in their full distinctiveness and to understand that diversity, as a marvelous mixture of peoples and cultures, can enrich our self-knowledge. Dialogue enhances our effort to work toward an authentic community for all.

African traditional religion is increasingly recognized for its contribution to the world. No longer seen as despised superstition which had to be superseded by superior forms of belief, today its enrichment of humanity’s spiritual heritage is acknowledged. The spirit of Ubuntu—that profound African sense that we are human only through the humanity of other human beings—is not a parochial phenomenon, but has added globally to our common search for a better world.

Nelson Mandela

The Dialogue among Civilizations presupposes the plurality of human civilizations. It recognizes equality and distinction. Without equality, there would be no common ground for communicating; without distinction, there would be no need to communicate. While equality establishes the basis for intercivilizational dialogues, distinction makes such joint ventures desirable, necessary, worthwhile and meaningful. As bridge-builders committed to dialogue, we recognize that there are common values in our diverse traditions that bind us together as women, men and children of the human family. Our collaborative effort to explore the interconnectedness of these values enables us to see that diversity empowers the formation of an open and vibrant community. Our own experience in multicultural encounters, our shared resolve to break down divisive boundaries and our commitment to address perennial social concerns have helped us to identify the values critical to the promulgation of responsible community.

Common Values

As never before in history, the emerging world community beckons us to seek a new understanding of the global situation. In the midst of a magnificent diversity of cultures, we are one human family with a common destiny. As our world becomes increasingly interdependent, we identify ourselves with the whole global community as well as with our local communities. We are both stakeholders of our own respective countries and of one world in which the local, national, regional and global are intricately linked. A shared vision of common values can provide and sustain an ethical foundation for a dialogue among civilizations. We recognize that the complexity of contemporary life may generate tensions between important values. The task of harmonizing diversity with unity is daunting; the conflict between private interests and the public good may seem unresolvable; and the choice between short-term gains and long-term benefits is often difficult. Yet, we believe that a new sense of global interdependence is essential for our ongoing collaborative effort to foster a worldwide mindset of hope.

From the Ten Commandments to Buddhist, Jain, Confucian, Hindu, and many other texts, violence and deceit are most consistently rejected, as are the kinds of harm they make possible, such as torture and theft. Together these injunctions, against violence, deceit, and betrayal, are familiar in every society and every legal system. They have been voiced in works as different as the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Icelandic Edda, and the Bhagavad-Gita.

Sissela Bok, Common Values, 1995

We affirm, from the outset, that we are for the protection of individual freedoms, for guarantees of fundamental rights and for the recognition of and respect for the equal worth of every human being. These are the Enlightenment values of the modern West and underlie a market economy, a democratic polity and civil society. While none of them is fully realized in any given society, they are universal aspirations. Indeed, liberty, rights and personal dignity have universal appeal, but so also do duty, human responsibility and the good of the community. They provide us with a fuller agenda to begin our reflection. The cultivation of a sense of duty and the protection of individual freedoms can work together to allow the human spirit to soar without the danger of social disintegration. The encouragement of human responsibility and the guarantee of fundamental rights can complement each other to give people a secured space for thought and action without threatening the fabric of social cohesiveness. The requirement that each act responsibly to one another (the community) and the recognition of and respect for the equal worth of every human being offer a balanced approach to the relationship between self and society.

Without the individual impube, community stagnates; without the sympathy of the community, individual impube fades away.

William James

The mutually beneficial interplay between self and society assumes a new shade of meaning in our time. We need to examine it in personal, local, national, regional and global contexts. We also recognize that transcendence of the divisiveness of self-interest requires moving beyond national and regional as well as personal and local concerns. Global forces beyond our comprehension easily overwhelm us and “ethnic and religious conflicts” beyond our control easily immobilize us, as if we cannot escape the predicament of the two extreme forms of destruction: domination and disintegration. Nevertheless, we hope that, with the advent of a dialogical global community, we can, for the first time, talk about the human family in the realistic sense of communication and interconnection. We want to stress that globalization has frightening aspects. It may bring about hegemonism and monopolism, for example, but this is not inevitable. Similarly, despite bigotry and exclusivism in identity politics, the authentic quest for identity is a noble calling and an educational experience for our children and us.

Our eyes grow heavy with weeping,

yet a brook can make us smile.

A skylark’s song bursting heavenward

makes us forget it is hard to die.

There is nothing now that can pierce my flesh.

With love, all turmoil ceased.

The gaze of my mother still brings me peace.

I feel that God is putting me to sleep.

Gabriela Mistral, “Serene Words”

We choose to reject faceless universalism, hegemonic control and monopolistic behavior on the one hand and ethnocentric bigotry, religious exclusivism and cultural chauvinism on the other. We believe that positive forces in globalization and authentic quests for identity can create a virtuous circle uplifting the human spirit in the coming decades. Wholesome globalization, which celebrates diversity and enhances community, is a matter of confluence, of mutual learning and recognition of the rich and varied human heritage. This allows for lateral and reciprocal relationships among civilizations and makes genuine dialogue possible. In such a dialogical mode, the echoes of each civilization awaken, encourage and inspire the others. The resultant sympathetic resonance is a truly cosmopolitan harmony, cross-cultural and trans-temporal. To this end, we wish to note that the most fundamental and pervasive value underlying all common values is humanity.

To understand the profoundly rich meaning of humanity, we begin with an exploration of the Golden Rule. Whether stated in the positive (“do unto others what you would want others to do unto you”) or the negative (“do not do unto others what you would not want others to do unto you”), the Golden Rule is shared by virtually all the great ethical and religious traditions. It was identified by the Parliament of World Religions in 1993 as the basic principle in the emerging global ethic. We believe that the awareness, recognition, acceptance and celebration of the other in our own self-understanding, implicit in the Golden Rule, help us to learn to be humane.

Humanity, Reciprocity and Trust

Learning to be humane (or, straightforwardly, “human”) is a defining characteristic of all classical education, East or West. It is a profoundly meaningful challenge in the contemporary world as we move beyond perhaps the most brutish century in human history. The idea of humanity, perceived inclusively and holistically, is applicable to every person under all circumstances. While we transcend race, language, gender, land, class, age and faith in asserting our conviction that the dignity of the human person is inviolable, we need to learn to treat each individual person humanely, whether a poor old white man, a Chinese merchant, a Jewish rabbi, a Muslim mullah, a rich young black woman or anyone else. This requires an ability to see difference not as a threat but as an opportunity to broaden humanity.

Our learned capacity to reject stereotyping, prejudice, hatred and violence in religious, cultural, racial and ethnic contexts is predicated on the value of reciprocity. Reciprocity is an integral component of the Golden Rule, a guiding principle present in all of our spiritual traditions. Strictly speaking, however, the Golden Rule stated in the negative—“do not do unto others what you would not want others to do unto you”—is required for true reciprocity. This seemingly passive attitude considers the integrity of the other without imposing our will, even if we honestly believe that our way is the best for everybody. This self-restraint is predicated on the belief that what is best for me may not be appropriate for my neighbor. In matters of taste or preference, this is easily understandable, but, in the context of religious pluralism, even faith cannot be exempted from the principle of reciprocity. Indeed, the spirit of dialogue can be dampened if the intention to proselytize overwhelms the necessity to listen and to learn first.

Nevertheless, the Golden Rule stated in the positive need not be in conflict with the spirit of reciprocity at all. While “do unto others what you would like others to do unto you” does not give us the license to impose our faith prematurely on anyone else, it instructs us to be concerned about others and actively involved in their well-being. Reciprocal respect, necessary for genuine dialogue, enables us to engage others in true partnership. Only when our conversational partners feel understood and appreciated can we take an active role in involving them in a mutually beneficial joint venture. Thus, the Golden Rule stated in the negative allows for creative engagement and the Golden Rule stated in the positive prevents the passivity of indifference toward the suffering of the other. Whether stated in the negative or in the positive, the Golden Rule cultivates interpersonal trust.

Trust enables dialogue to occur, to continue and eventually to bear fruits. It is the backbone of true communication. Without trust, we can do little to facilitate any meaningful communication. Trust is not blind. It is a rational choice to enter into communication with the other. It is the minimum condition for transcending the psychology of fear. Unless we can move out of our self-imposed cocoons and face up to the challenges of the unknown, we will never be able to rise above our egoism, nepotism, parochialism and ethnocentrism. Mistrust inhibits any cross-cultural collaborative effort and stunts the growth of a culture of peace. Trust is a commitment to the possibility of an ever-enlarging community. It is the source of mutual respect and understanding. Trust enables us to accept the other as an end rather than a means to an end.

Trust is not opposed to a healthy dose of skepticism or the critical spirit, but it is never hostile to the other or cynical about the actual state of affairs. Despite tensions and conflicts in the world, trust involves a willingness to explore commonality and shareability with those who are stereotyped as radical others. Trust is the courage to enter into a joint venture with a stranger who is conventionally labeled as the enemy. Through trust, we respect the integrity of the other as a matter of principle and also as an end in itself. While a trusting person may sometimes be disappointed and deceived, it does not deflect him or her from the commitment to continuous communication within and beyond family, society and nation. Trust involves keeping promises and seeing one’s action through. Yet, it is dictated by a higher principle of rightness. If promise-keeping will be harmful to the overall well-being of a person (for example, lending money to a drug abuser), it is right to break the promise. Similarly, if an initiated action is likely to lead to disastrous consequences, such as the development of an environmentally unsound power plant, discontinuing the action is right.

To assume trust in the integrity of the other is to be fair-minded and respectful. It is the beginning of true dialogue. The need for trust in any business transaction or contractual agreement is obvious, but trust in interpersonal and cross-cultural communication is even more important. While legal actions can be taken to remedy commercial misconduct or a breach of contract, all possibility of communication simply evaporates between persons and cultures when trust is absent. A sense of fairness can generate a spirit of trust; with trust, it is easy to put justice into practice. Similarly, a humane person is trusting and trustworthy. Motivated by sympathy and compassion, a humane person establishes an ever-expanding network of interpersonal and cross-cultural relationships. Trust is implicit in these relationships. With trust, legal constraints are simply preventive measures. When interchange among peoples and cultures is conducted in good faith, civility pervades the process and mutual learning ensues. If we have faith in the Dialogue among Civilizations, we can learn not merely from the wisdom of our own tradition but also from the cumulative wisdom of the entire human community.

Humanity and trust engender the ethos of mutual flourishing in interpersonal relationships at both individual and communal levels. They are the preconditions for discussing common values. Without humanity and trust, there is no underlying common ground for exploring values as a joint spiritual venture of like-minded dialogical partners. In light of this discussion, we wish to identify the following sets of common values for focused investigation: liberty/justice, rationality/sympathy, legality/civility and rights/responsibility. Since the values of liberty, rationality, legality and rights have been more thoroughly elucidated in contemporary political discussions, we choose to emphasize the importance of justice, sympathy, civility and responsibility as equally significant values for the emergence of the global community. We believe, if fully recognized, these four common values can help to facilitate dialogue among civilizations; such dialogue can substantially enhance the possibility of realizing a global ethic.

Toward a Global Ethic

Liberty and Justice If humanity helps us to relate meaningfully with our fellow human beings, justice is the practical method of putting this value into concrete action. A humane world is necessarily just. Gender inequality and racial discrimination are unjust. So are major discrepancies in income, wealth, privilege and accessibility to goods, information or education.

Since the widening of the gap between the haves and have-nots is an unintended negative consequence of globalization, we are particularly concerned about the marginalized, disadvantaged and silenced individuals and groups in the human family. They deserve our focused attention and our persistent support. We believe that the more influential and powerful an individual, a group, a nation or a region is, the more obligated he, she or it is to improve the well-being of the human community. It is not practicable or even just to impose an arbitrary principle of egalitarianism on individuals and groups, but it seems only right to ask that the beneficiaries of globalization share their resources more equitably with the world. Justice means that public policies tend toward benefiting the weaker. It is humane and just to figure out ways to empower the marginalized, underprivileged, disadvantaged and silenced.

Justice as fairness is a call to higher standards of behavior. The eradication of poverty is a prominent just cause in the emerging global community. How can we help to build capacities to enable the poor to rise out of their poverty? How can we educate women and girls so that they can break away from the vicious cycles of population pressure and economic underdevelopment? How can we encourage the leadership of the North and successful economies elsewhere to recognize that the elimination of poverty, regardless of where it occurs, is integral to their national interests? How can we appeal to the conscience of people worldwide to see that poverty anywhere is a global concern? Such questions need to be addressed at local, national, regional and global levels.

We think these questions are being slowly addressed. The commitment at the 1995 Social Summit in Copenhagen to “accelerate the development of Africa and the least developed countries” is predicated on a realistic model of interdependence. If we consider ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious diversity as a global asset, Africa could not be solely characterized as the continent of the HIV epidemic, poverty, underemployment and social disintegration alone. It could also be recognized as a rich reservoir for human spirituality and the cumulative wisdom of the elders. The African spirit, symbolized by the geological and biological diversity of the tiny area around Cape Town, South Africa, said to be comparable in richness to the vast area of Canada, ought to be a source of inspiration for a changed mindset that addresses social development as a global joint venture. The fate of Africa is important for non-Africans as well because, without a holistic sense of human flourishing, we cannot properly anchor our security, let alone our well-being, in the global community as a whole. Indeed, Africa has provided such lessons.

When the Prophet Muhammad sent his oppressed followers to the African Christian King Negus of Abyssinia for safety, and they received his protection, was that not an example of tolerance and cooperation to be emulated today? …

The nature of interaction between the strands of our religious heritage could help lay solid foundations for the establishment of a world order based on mutual respect, partnership, and equity. On a continent battling against the scourge of underdevelopment, AIDS, ecological disaster, and poverty, competition amongst religions will be utterly misplaced. Tolerance and cooperation, on the other hand, will give the moral leadership so gravely needed.

Nelson Mandela

It is neither romanticism nor sentimentalism that compels us to focus our attention on Africa. While sympathy, empathy and compassion propel us to form solidarity with our brothers and sisters in agony, justice impels us to recognize that our well-being is at stake if even a corner of the world, let alone a continent, is in grave peril. A limited short-term rational calculation may fail to show any tangible linkage between Africa’s problems and the self-interests of other regions, but common sense tells us that, since interdependence has become a fact of life in the global community, ignorance and neglect of a substantial part of the world is detrimental to human security in the long run. Indeed, the abusive treatment of any one of us diminishes the sacredness of humanity as a whole.

Dialogue among civilizations is inclusive. It is an open invitation to all members of the global community. Justice, founded on fairness, assures us that all willing participants are allowed in the dialogue without discrimination. Justice, based on fairness, further encourages wider participation by actively involving those on the periphery. Those who perceive dialogue as an exercise in futility or merely a dispensable luxury, because the burning issues of basic survival overwhelm them, could particularly benefit from positive engagement in an ongoing dialogue. In fact, their presence in a fair-minded interchange (sharing stories for example) can help to improve the behavior, attitudes and beliefs of those immune to the plight of the marginalized. At the same time, the causes of and solutions to urgent problems can be put in a new light. Often, injustice on the part of political leadership (the lack of transparency, public accountability and fair play) is the main reason for economic and social crises. The issues can be more clearly identified and more effectively managed from a comparative cultural perspective.

Rationality and Sympathy Human beings have often been defined as rational animals. The ability to know our self-interest, to maximize our profit in a free market or to calculate our comparative advantages indicates that we are capable of instrumental rationality. Rationality, or more appropriately reasonableness, is also essential for interpersonal relationships, acquisition of knowledge, political participation and social engagement. Humaneness, however, involves sympathy, empathy and compassion as well. Humanity as a value cannot be realized through rationality alone. The ability to treat a concrete person humanely is not the result of rational choice but of sensitivity, conviction, commitment and feeling.

Attachment to and intimacy with those who are close to us is one of the most natural and common human experiences. We cannot bear the suffering of those we love. This sense of commiseration is often confined to our children, spouse, parents, immediate kin and close friends. If we can extend this personal feeling to commiserate with those we like, to those we care for, to those we barely know and even to strangers and beyond, our sense of interconnectedness will be greatly enhanced. We may never truly experience the lofty ideal of forming one body with humanity, but if we aspire to the moral dictum that we should treat all human beings as brothers and sisters, we will try to establish harmonious relationships with an ever-extending network of interconnectedness. The need for dialogue among civilizations is based on care for the other.

It is often assumed that while rationality is objectively verifiable and publicly accountable, sympathy, as a matter of the heart, is personal and private. Surely, as an emotive state, sympathy cannot be easily described in precise language or rigorously defined in quantitative terms. Nor can it necessarily be demonstrated as a generalizable quality of the human psyche. We all hope that human beings learn to be sympathetic, but we cannot ensure the universality of sympathy across race, culture and religion. Under the influence of Greek philosophy, for example, we are willing to assert that human beings are rational animals, but we are reluctant to insist that sympathy is a defining characteristic of human nature as well.

However, in a comparative civilizational perspective, both Confucianism and Buddhism maintain that sympathy, empathy and compassion are at the same time the minimum requirement and the maximum realization of the human way. According to Confucian and Buddhist modes of thinking, human beings are sentient beings. Sensitivity, rather than rationality, is the distinctive feature of humanity. We feel; therefore we are. Through feeling, we realize our own existence and the coexistence of other human beings, indeed birds, animals, plants and all the myriad things in the universe. Since this feeling of interconnectedness is not merely a private emotion but a sense of fellowship that is intersubjectively confirmable, it is a commonly shareable value.

In a deeper sense, sympathy is not a learned capacity but a naturally endowed quality of the heart-and-mind. It is natural to feel the suffering of others. Even if we are hardened by circumstances beyond our control and desensitized by frequent exposure to atrocities, our ability to respond to tragic events is never totally lost. Yet, one of the saddest human tragedies is the temporary loss of any sympathy toward the perceived enemy. In the case of a psychopath or a terrorist obsessed with revenge and retaliation, the victim (often the innocent victim) is so “dehumanized” that inflicting pain, suffering and death upon him or her is deemed inevitable or even desirable. It is not the absence of instrumental rationality, self-righteousness and moral indignation (of course in the most distorted forms imaginable) but the total lack of sympathy, empathy and compassion that makes the actions of such a human being so inhumanly devastating. The cultivation of sympathy, through education, as a way of recovering the original heart-and-mind endowed in human nature is essential for nurturing a global mindset of peace.

Obviously, it is naïve to believe that the cultivation of sympathy can actually combat terrorism. Yet, undeniably, politically manipulated and “religiously charged” terrorism is motivated by a firm belief that extraordinarily violent measures are necessary to right perceived wrong. Otherwise how could intelligent men and women of faith be so thoroughly “brainwashed” that they design elaborate schemes to murder innocent people by committing suicide themselves? The psychopathology, or sheer madness, underlying such desperate action is most frightening. The hatred is so intense that the ultimate suffering—death by suicide—is employed as a strategy to inflict the maximum damage. The idea of “live and let live” is inverted. Human intelligence demands that we probe deeply into the mindset of these terrorists in order to understand how they actually end up choosing cruel and dehumanizing action. Several common values are distorted and abused to justify the inevitability of such an outrageous act: sincerity, commitment, moral indignation, rationality, sacrifice, righteousness and daring; yet, sympathy, empathy and compassion for anyone considered as “other” are totally absent. These essential features of humanity are completely rejected by the tough-minded terrorists.

Without sympathy, empathy and compassion, sincerity degenerates into obsessiveness, commitment into fanaticism, moral indignation into aggressive anger, rationality into an instrument of destruction, sacrifice into massive suffering, righteousness into arrogance and daring into brutality. Humanity as sensitivity and sensibility nurtures other values so that sincerity, commitment, moral indignation, rationality, sacrifice, righteousness and daring can enrich our inner resources and strengthen our resolve to cultivate a mindset of peace through personal transformation.

Legality and Civility The rule of law is essential for the maintenance of order. The demand for transparency in the market economy, for public accountability in a democratic polity and for due process in civil society strongly indicates that, without the rule of law, it is difficult to assure security, good governance and the protection of rights. Yet law, as the minimum condition for orderliness, cannot in itself generate public-spiritedness or a sense of responsibility. The cultivation of a civic ethic is necessary for people who seek the fullness of life in communal harmony. Since a multiplicity of traditions guides the thoughts and actions of the world’s peoples, legality without civility cannot inspire public-spiritedness. A legal system devoid of a civic ethic can easily degenerate into excessive litigiousness.

Civility complements the rule of law and provides legality with a moral base. It is the proper way to deal with fellow citizens. If positive global trends—those that enhance communication and interconnection without increasing hegemonism—help to bring about an ever-expanding connected community, civility is the key to sustaining such a process. Without civility, genuine dialogue is impossible. Civility is indispensable in intercultural communication. Our willingness to suspend judgment, to critically examine our own assumptions, to appreciate what has been said without drawing up premature conclusions, to inquire further into the relevant points and to reflect on the meaning of the interchange is congenial to the cultivation of a civic ethic.

Humanity enables us to establish a reciprocal relationship with the other; justice helps us to put our humane feelings for the other into action; and civility provides the proper form of interpersonal communication. Without civility, competition becomes a brutal task of domination and tension, and an adversarial system quickly degenerates into a hostile struggle for power. Laws in themselves may well encourage compliance, but the cultivation of civility is essential for the smooth functioning of a harmonious society. As we envision a global civil society in which the lateral relationships of all cultures, including newly emerging ones, facilitate mutual learning, hope for perpetual peace is being fostered.

The emergence of a global civil society, as reflected in the creative imagination, enthusiastic participation and dynamic activity of nongovernmental organizations at Rio (environment and development, 1992), Cairo (population, 1994), Copenhagen (social development, 1995) and Beijing (women, 1995) strongly suggests that newer players on the international scene, transcending ethnic, linguistic, cultural and religious boundaries, require new rules of the game to help negotiate a terrain replete with tension and conflict with a tolerable level of civility. We cannot depend only on clearly specified laws and regulations to guide our conduct in this unfamiliar territory. A common sense of decency and hospitality, taught in virtually all the spiritual traditions, provides a basis for dialogue and communication.

In the language of civility, diplomacy between nations is translated into politeness between individuals. Fear of the other breeds the unhealthy desire to dominate. Anger easily leads to violence and the psychology of suspicion is a major cause for aggression. While vigilance is necessary for navigating in troubled waters, civil action rather than military or legal action is the only sustainable approach to enduring interpersonal relationships. An ethic of civility is not a substitute for the rule of law, but, without the spirit of civility, law-abiding citizens can be aloof, indifferent and even rude. Civility encourages humanity, reciprocity and trust and at the same time complements legality.

Rights and Responsibility While rights-consciousness is essential for cultivating autonomy, independence and personal dignity, the emphasis on the idea of a freely choosing and rights-bearing individual without any sense of obligation, duty or responsibility is not congenial to social solidarity or human flourishing. Since the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, advocacy of human rights has become a salient feature of modern consciousness. The state’s advocacy of human rights is no longer confined to a handful of developed countries. Most United Nations members subscribe to some, if not all, of the international human rights agreements. Even regimes with blatant violations of human rights are compelled by public opinion to pay lip service to those rights. The spirit of our time encourages rights discourse to spread to all corners of the world and to embrace all of humanity, transcending race, gender, class, age and faith.

However, human rights have evolved from political rights to encompass economic rights and, eventually, cultural and group rights. While the original United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is comprehensive in its coverage, the actual process of implementation has been painfully slow, even among nations most articulate in promoting human rights as a universal human aspiration. Although the claims that countries can have different concepts of human rights and that we ought not demand that all nations comply with universal standards of human rights are subject to criticism, how to coordinate and integrate political rights with economic, social, cultural and group rights is of vital importance for a cross-cultural dialogue.

Underlying the necessity and desirability of an international dialogue on human rights is the question of the responsibility and, by implication, duty and obligation of all dialogical partners. While rights-consciousness with its multifaceted dimensions emerged rather recently in human history, all spiritual traditions developed a mature sense of responsibility or duty-consciousness early in human civilization. Some of the criticism leveled against the human rights discourse may have been motivated by the specific desire of political leaders to underscore deference to authority as a cornerstone for stability.

It is a truism to note that countries at different stages of economic development or with different historical traditions and cultural backgrounds have different perceptions and practices of human rights. However, human rights, as a defining characteristic of modernity, must not be subject to dictatorial or authoritarian polity. Placing an equal emphasis on rights and responsibility is a balanced approach to human flourishing and an effective way of cross-cultural dialogue.

Indeed, rights without responsibility may lead to a form of self-indulgence, indicative of egocentrism at the expense of harmonious social relationships. The moral strength of rights-consciousness lies in its generalized appeal to the dignity of the individual versus the coercive power of the state. Often human rights advocates are inspired by a sense of justice not for themselves but for the marginalized and the silenced who, constrained by forces beyond their control, are incapable of defending themselves. Underlying the rights discourse is the recognition that all fellow human beings are interconnected. Implicit in the recognition is a sense of responsibility for those not fortunate enough to demand that their rights be protected. Persons with the idea of inalienable rights solely motivated by self-interest easily turn out to be egoists.

The principle deduced from the above is that the privilege of rights entails responsibility. Are those who are more powerful and influential more obligated for the well-being of the collectivity variously defined, from the family to the global community? Several countries have specified nonjudiciable rights, such as job security and economic prosperity, in their constitutions. Unlike freedoms of speech, assembly and religion, however, one cannot demand that the government grant nonjudiciable rights as a matter of principle. They are, nevertheless, legitimate aspirations of ordinary citizens that, by and large, responsible governments try to attain. Again, it is highly advisable that the beneficiaries of a particular society assume the responsibility for its weak and underprivileged. Similarly, do the “winners” of the global market economy cultivate a duty-consciousness consonant with their power, influence and accessibility to technology, information, ideas and material resources?

Wisdom

Humanity and trust underlie the common values. Without them, liberty/justice, rationality/sympathy, legality/civility and rights/responsibility will not have the wholesome ethical environment in which to become fully realized. Yet, the acquisition of common values requires a kind of personal intelligence that has been the focus of philosophical reflection since the dawn of human civilization. The Socratic ideal to “know thyself” entails the spiritual exercise and moral self-cultivation, the humanist way of learning, to be fully human. While intelligence signifies the ability to learn from experience, to acquire and retain knowledge and to use the faculty of reason in solving problems, it is through personal intelligence as wisdom that human beings have survived and flourished. In light of the grave dangers that seriously threaten our viability as a species, the need for wisdom is compelling.

Wisdom connotes holistic understanding, profound self-knowledge, a long-term perspective, common sense and good judgment. A spark of inspiration may elucidate an aspect of the world’s situation, but a comprehensive grasp of the human condition requires continuous education. A fragmented approach to learning is inadequate. Personal knowledge, the kind of experiential self-awareness that is both communal and critical, can only be cultivated through persistent effort. If we go after short-term gains at the expense of long-term benefits, we may be smart, but never wise. Although thinking in a long-term perspective implies a prophetic vision, wisdom, far from being speculative thought, always brings about concrete results. The ability to take a variety of factors into account in making judgments is a sign of wisdom. While healthy dialogue requires suspension of preconceived opinions, the nonjudgmental attitude does not mean the absence of good judgment. The judgment of the wise is measured and balanced; it is the middle path transcending opinionated extremes.

Advances in science and technology have so significantly broadened our horizons and deepened our awareness of the world around us that many feel that the wisdom of the great religions and philosophical traditions is irrelevant to our modern education. Surely, globalization has greatly expanded the data, information and knowledge available for our use and consumption, but it has also substantially undermined the time-honored ways of learning, especially the traditional means of acquiring wisdom. We cannot confuse data with information, information with knowledge and knowledge with wisdom; we need to learn how to become wise, not merely informed and knowledgeable. There are three essential ways to acquire wisdom worth special attention in our information age.

First is the art of listening. Listening requires more patience and receptivity than seeing. Without patience, we may listen but fail to grasp the message, let alone the subtle meaning therein; without receptivity, the message will not register in the inner recesses of our hearts and minds even if we manage to capture what is said. Through deep listening, we genuinely encounter others. Indigenous peoples, for example, can teach us how to listen not only to one another but also to the voice of nature. Only through deep listening will we truly comprehend what is communicated through the ear.

The second is face-to-face communication. Talking directly with another is the most common and simplest way to communicate, but it is also the most challenging and rewarding. Conversation over the telephone, or using even more sophisticated electronic devices, is no substitute for a face-to-face talk. A partner is required for this kind of communication. Face-to-face communication is the most enduring method of human interaction and, in the last analysis, the most authentic way of transmitting values. If it is relegated to the background, there is little chance that we can become wise.

The art of listening and face-to-face communication are the indispensable ways to access the third timeless way of learning: the cumulative wisdom of the elders. Precisely because we are exposed to so much data, information and knowledge in the modern world, our need to acquire wisdom is more urgent than ever. The wisdom of the great religious and philosophical traditions teaches us how to be fully human. The cumulative wisdom of the elders refers to the art of living embodied in the thoughts and actions of a given society’s exemplars. Only through exemplary teaching, teaching by example rather than by words, can we learn to be fully human. We cannot afford to cut ourselves off from the spiritual resources that make our life meaningful. We emulate those who exemplify the most inspiring ways of being fully human in our society, not only with our brain, but also with our heart and mind, indeed our entire body. This form of embodied learning cannot be done by simulation alone. Understandably, language, history, literature, classics, philosophy, religion and cultural anthropology—subjects in the liberal arts education—help us to acquire wisdom and are never outdated.

Learning to be fully human involves character building rather than the acquisition of knowledge or the internalization of skills. Cultural as well as technical competence is required to function well in the contemporary world. Ethical as well as cognitive intelligence is essential for personal growth; without the former, the moral fabric of society will be undermined. Spiritual ideas and exercises as well as adequate material conditions are crucial for the well-being of the human community. Cultural competence is also highly desirable. Even if we do not possess literacy, a sense of history, a taste for literature or a rudimentary knowledge of the classics, we can still live up to the basic expectations of citizenship, but our participation in our nation’s civic life will be impoverished. Ethical intelligence is necessary for social solidarity. Spiritual ideas and exercises are not dispensable luxuries for the leisure class; they are an integral part of the life of the mind that gives a culture a particular character and a distinct ethos.

The values specified above are selective rather than comprehensive. Acting in accordance with these values is necessary for an effective and enriching dialogue among civilizations; these values can also be cultivated through the actual process of the dialogue. They are common values that have been articulated by all spiritual traditions in different contexts and historical situations. These values can be taught through example, story sharing, religious preaching, ethical instruction and, most of all, dialogue.

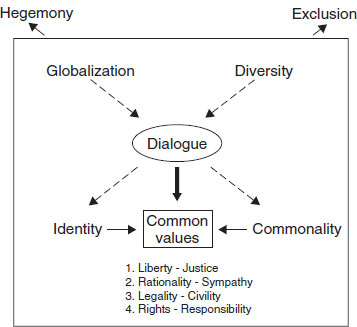

Figure 32.1

The ideas in this chapter can be shown in a simple diagram with two propositions: (1) Globalization may lead to faceless homogenization that is ignorant about differences and arrogant about hegemonic power; through dialogue, it may also lead to a genuine sense of global community. (2) The quest for identity may lead to pernicious exclusion, with ethnocentric bigotry and exclusivist violence; through dialogue, it may also lead to an authentic way of global communication and a real respect for diversity.