This chapter is Lise M. Sparrow’s challenge to Peter Adler’s model of “multicultural man,” which describes an intercultural person as someone who lives on the boundary with fluid and mobile identity and embraces marginality as the most desirable stage of identity development. This form of multicultural identity, according to her, typically reflects the experience of White men and does not resonate with many women and ethnic minorities. In her analysis of student writings and in-depth interviews with 20 people, she discovers that the multicultural women identity reported by her respondents is strikingly different from Adler’s conceptualization. Whereas the multicultural White man spoke of marginality as the mental capacity to detach from social realities, the multicultural women expressed that the socio-cultural context is equally important, if not more, than the cognitive capacity for self-reflection in its influence on their personal experiences and social identities. Although the “multicultural man” identity is achieved through transcending cultural identities, the multicultural female interviewees verbalized their identities as rootedness and belonging and their desires to reconnect to the religions, languages, and ethnic traditions with which they had grown up. Sparrow visualizes multicultural women’s identity in the image of a tree, that is, deeply rooted in community while adjusting their growth to the environment and expanding connections with others. Through her analysis of the narratives of the multicultural women, she invites communication scholars and students to reconsider the issues of marginality, in-betweeness, uniqueness, commitment to community action in the conceptualization of inter-cultural identity development.

In 1977, Peter Adler characterized the experience of what he called “multicultural man.” His article was an important think-piece for the field of intercultural communication. His articulate description of a “new kind of man,” who might “embody the attributes and characteristics that prepare him to serve as a facilitator and catalyst for contacts between cultures” (Adler, 1977, p. 38), provided for the basis for considerable discussion about the types of persons best suited for working across cultures and was included in a primary text used in intercultural communication courses (Samovar & Porter, 1985) and in many compilations of intercultural training materials.

In his article, “Beyond Cultural Identity: Reflections on Cultural and Multicultural Man,” Adler (1977) suggested that the conditions of contemporary history may be creating “a new kind of man” whose identity is based not on a “belongingness,” which implies either owning or being owned by culture, but on a style of self-consciousness that is capable of negotiating ever new formations of reality. This person, he said, “lives on the boundary,” is “fluid and mobile,” and committed to people’s essential similarities as well as their differences. “What is new about this type of person and unique to our time is a fundamental change in the structure and process of identity” (Adler, 1977, p. 26).

More recently, Janet Bennett’s work (1993) on “cultural marginality” cites the story of Barack Obama, the first black elected president of the Harvard Law Review. She says he seems to claim for himself “an identity that is beyond any single cultural perspective” and posits that he and other “constructive marginal … are coming to terms with the reality that all knowledge is constructed and that what they will ultimately value and believe is what they choose” (J. Bennett, 1993, p. 128).

Milton Bennett (1993) similarly argues that these marginals, who have reached the final stage of development with respect to his model of intercultural sensitivity, are “outside all cultural frames of reference by virtue of their ability to consciously raise any assumption to a meta-level (level of self-reference)” (p. 63). Adler and the Bennetts represent important current thinking about what it is to be multicultural and of the constructivist view of identity development.

As an instructor of intercultural communication, I initially found these articles to be exceptionally useful with the students in our master’s degree programs at the School for International Training, most of whom had lived overseas extensively and spoke many languages other than English. More than 20% of the student body comes each year from outside the United States, and of the Americans, the ethnic and racial diversity has increased markedly over the past decade. Differences in gender, age, sexual orientation, and religious affiliation have also become a much more explicit part of informal conversation as well as of the curriculum. Managing these personal and cultural differences has become a central challenge for participants in our programs and has inevitably forced students to become more self-aware and to make conscious choices about their interactions with others.

As such, in the context of our courses, Adler’s view of what it means to be a multicultural person faced considerable scrutiny. Students in our programs questioned the article both because it was based solely on the experiences of men and because many of Adler’s assumptions about what it takes to work effectively in intercultural settings did not match their own experiences overseas. Though the Bennetts’ more recent work on marginality explicitly addresses the inherent challenges to identity of extended multicultural experience, students often questioned whether one could really choose to act on one’s values if those values were not recognized in the contexts in which they lived as professionals.

One Taiwanese woman, for example, in a final paper for a course entitled “Culture, Identity and Ethnic Diversity” reflected on her dependence on men for her identity:

It was necessary in the high-context Chinese culture … for a man to designate my status identity.

Students of color similarly claim that the opportunity to construct an individual identity is a luxury available only to those in dominant social categories. A Somali woman interviewed as part of the study described in the latter part of this paper, talked about cultures in a similar way, as limiting her interactions:

In order for me to function I have to be able to do what these people do while I still feel comfortable … I always have to check and when I check I think, did I say or do that right?

International students add that the very concept of an individual identity is Eurocentric. A woman from Hong Kong wrote in her final paper:

Unlike American culture which recognizes individual identity as rooted in personal accomplishment … (in my) society one’s identity is rooted in groups … my identity was not my own to establish and/or earn.

As those with unclear membership in any one culture have talked about the importance of connection, rather than marginality. One man wrote:

I have found that even as I seem to free myself from the particulars of my life, the particulars always remain in my life and nurture it much like a plowing of weeds nurture a garden. My particulars are always part of my life … the ultimate protection from the insufferable hubris of “terminal uniqueness.”

The fact that Anglo-American men in our program have tended to identify strongly with Adler’s description of a multicultural person has also been of great interest to me, especially given that women, people of color and international students generally state that individuality and self-constructed identity are neither possible nor desirable from their points of view.

In response to these diverse critiques, I eventually stopped including the Adler article in the students’ core curriculum. Nonetheless, students in our program have continued to express a compelling desire to define what it means to be a multicultural person and to discuss to what extent the solutions posed by the Bennetts’ “constructive marginality” are valid for women and ethnic minorities. It is the purpose of this paper to consider these differences in the experiences of multicultural identity, both through a review of literature related to the definition of self and the development of identity, and through the results of a small research project. Inasmuch as Adler states that his multicultural man’s disembodied mind may very well represent “an affirmation of individual identity at a higher level of social, psychological and cultural integration” (Adler, 1977, p. 38), it would seem important to continue to explore his as well as alternative views of identity and to explore the intrapsychic dilemmas of such people. Questions which I hope to address in this paper are first, whether the ideal of a free-acting individual is in itself a Western or male viewpoint and second, whether it is an optimal view at all. In his paper Adler enjoins others to further research and exploration. That was the essential purpose of the study which is the subject of this paper.

Review of Literature

As stated above, Adler’s description of the multicultural person has been paralleled in the recent description by Janet Bennett (1993) of “cultural marginality,” and in the final “integration stage” of the “Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity” described by Milton Bennett (1993). In discussing the last stage of his model, M. Bennett (1993) states that “people can function in relationship to cultures while staying outside the constraints of any particular one” (p. 60). Tillich (1966) also suggested that the future will demand that one live with tension and movement:

It is in truth not standing still, but rather a crossing and return, a repetition of return and crossing, back and forth—the aim of which is to create a third area beyond the bounded territories, an area where one can stand for a time without being enclosed in something tightly bounded. (p. 111)

Yoshikawa (1987) similarly posits an integration of Eastern and Western perspectives in which the communicator “is not limited by given social and cultural realities” but operates in “the sphere of ‘between’ where the limitation and possibility of man and culture unfold … [and] one has a transcending experience” (p. 328).

These theories are based in the “radical constructivist” view (von Glasersfeld, 1984) of communication which suggests that it is, in fact, possible to escape the influence of one’s own reality. M. Bennett (1993) describes the optimal stage of identity as that in which people “are outside all frames of reference by virtue of their ability to consciously raise assumption to a meta-level (level of self-reference). In other words, there is no natural cultural identity for a marginal person” (p. 63). The assumption of these theories is that marginality and the experience of transcendence are not only possible but that they are “the most powerful position from which to exercise intercultural sensitivity” (M. Bennett, 1993, p. 65).

This Cartesian concept of a mind, detached from experience, capable of determining an objective reality, while still the ideal model of many intellectual and ethical theories based on work with White Western male respondents (Kohlberg, 1976; Levinson, 1978; Murray, 1938; Perry, 1970; Rogers, 1956; Spence, 1985), has, however, been brought into question recently by feminists (Benack, 1982; Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger & Tarule, 1986; Gilligan, 1982; Josselson, 1987; Loevinger, 1962; Marcia, 1980). The importance of a sense of belonging and relationship, both to one’s own background and ultimately to that of others, is highlighted as optimal in many current racial and ethnic identity development theories (Myers et al., 1991; Hecht, Collier & Ribeau, 1993). Cross-cultural research (Geertz 1976; Kakar, 1989, 1991; Sampson, 1985; Schweder, 1991; Schweder & Bourne, 1982), and post-modern educators also suggest that cultural and sociopolitical factors influence identity development (Freire, 1985; Giroux, 1983; Katz, 1985; Leung, 1990; Nieto, 1992). Similarly, within the field of communication as well, the “social constructionist” view (Gergen & Davis, 1985; Hoffman, 1993; Schweder, 1991) suggests that the very frames of reference we use to construct our identities are rooted in our social experiences. Research in bilingual and feminist education, psychology and intercultural competence have, in fact, consistently shown that it is in “connection” (Belenky et al., 1986), interaction (Bateson, 1972; Hoffman, 1993) and “sharing meaning” (Collier & Thomas, 1988) that growth, mediation and communication occur.

Cross-Cultural Differences in the Concept of Self

The idea that a mind can isolate itself from its experience has also been problematized frequently by those outside Western cultural paradigms. Balagangadara (1988) suggests, in stark contrast to this concept, that while:

the Western man feels the presence of “something deep inside himself” even if he is unable to say what it is [and] builds an identity for such a self [which] is what makes such an endowed organism unique … By contrast, the Easterner would experience nothing, or some kind of hollowness, the psychological identity of such a self is a construction of the “other,” an agent is constituted by the actions which an organism performs, or … is the actions performed and nothing more. (p. 103)

Further, he states, those actions are without meaning unless construed or “ascribed” in some way by another.

Similarly, in his paper contrasting concepts of self in China and the United States, Pratt (1991) states:

The Chinese construction of the self and location of personality appears to be derived primarily from the cultural, social, and political spheres of influence which an emphasis on continuity of family, societal roles, the supremacy of hierarchical relationships, compliance with authority, and the maintenance of stability. The resulting self finds an identity that is externally ascribed, subordinated to the collective, seeks fulfillment through the performance of duty, and would have little meaningful existence apart from ordained roles and patterns of affiliation. If this is true, the Chinese self is, largely, an externally ascribed, highly malleable, and socially constructed entity—part of an intricate composite that, like a hologram, is representative of the whole, even when removed from it. (p. 302)

In contrast, he says the individual in the United States “is recognized as the starting point for construing the social order, and the self is considered a psychological construct as much as an artifact of cultural, social and political influences” (p. 302). The intricate holographic conception of self within China poses a stark contrast to the psychologically constructed conception within the United States.

Rosaldo (1982) also contrasts the Ilongot concept of the self to the traditional Western model:

What Ilongots lack from a perspective such as ours is something like our notion of an inner self continuous through time, a self whose actions can be judged in terms of sincerity, integrity, and commitment … Ilongots do not see their inmost hearts as constant causes, independent of their acts … what matters is the act itself and not the personal statement it purportedly involves. (p. 228)

Finally, Geertz (1976) makes a similar contrast with the Javanese, Balinese and Moroccan concepts of self:

The Western conception of the person as a bounded, unique, more or less integrated motivational and cognitive universe, a dynamic center of awareness, emotion, judgment and action organized into a distinctive whole and set contrastively both against other such wholes and against its social and natural background, is, however incorrigible it may seem to us, a rather peculiar idea within the context of the world’s cultures. (p. 225)

These examples provide the basis for questioning whether the concept of an individuated self, capable of free choice and action is not a construct of Western languages and cultures.

African American Views of the Self

Looking at this same issue within the American context, one finds that African Americans, as one example, also cite contrasts with the dominant Western view of the self. Hecht et al. (1993) posit that African Americans by and large identify themselves not so much as individuals, but as linked across time and space, and as altering self-concept in relation to the situation and in “relationship to other members of the group and to members of other groups” (p. 40). Asante (1987) extends this by emphasizing the contextually determined interrelationship of feeling, knowing and acting and posits that, in contrast to M. Bennett’s (1993) position that we are best served by a meta-stance outside our experience, “in Afrology (sic 1) the study of an object is best performed when all three components are interrelated.” Asante further states: “One becomes human only in the midst of others” (p. 79). bell hooks (1990) similarly contrasts Adler’s emphasis on marginality with her African American community growing up, and with her need as she grew up to understand both the dominant White culture and her own African American culture, and to see both as part of a whole:

We looked both from the outside in and the inside out. We focused our attention on the center as well as on the margin. We understood both. This mode of seeing reminded us of the existence of a whole universe, a main body made up of both margin and center (p. 149).

Gender Differences in the Concept of Self

Current research into Western female identity also contrasts that of Western men. Relating directly to the issue of marginality, Chodorow (1978) asserts that boys have the early challenge of disconnecting themselves from an identification with their mothers while girls are encouraged to “maintain more connected, fluid relationships” (Enns, 1991, p. 212). Miller (1986) extends this to say that, in contrast to men, women are “trained to be involved with emotions, to sense physical, emotional and mental growth and ultimately have a greater recognition of the essential cooperative nature of human existence” (p. 38).

Belenky et al. (1986) put forth a view of female identity, much like that of hooks, that is situated in and develops through relationship: “You let the inside out and the outside in.” In women they say, “there is an impetus to try to deal with life, internal and external, in all its complexity” (Belenky et al., 1986, p. 128). In emphasizing the differences between men and women’s moral development, Gilligan (1982) has been perhaps most successful in pointing out both the impetus for men to develop a sense of individual self-identity and for women to emphasize contextual and relational aspects of experience and ultimately, of choice: “For Stephen leaving childhood means renouncing relationships in order to protect his freedom of self-expression. For Mary, ‘farewell to childhood’ means renouncing freedom of self-expression in order to protect others and preserve relationships” (p. 157). She notes that for women: “The standard of judgment that informs their assessment of self is a standard of relationship, an ethic of nurturance, responsibility, and care” (p. 159).

Recent research in intercultural adjustment (Mendenhall & Oddou, 1985; Parker & McEvoy, 1993) also supports the view that marginality is a trait more typical of men and that, in fact, the relational and communication skills associated more often with women are the most appropriate precursors to adjustment and interaction with host country nationals. Parallel to gender-related research in psychology (Gilligan, 1982; Miller, 1986), Kealey’s (1990) study in cross-cultural effectiveness reported that:

women are more highly rated than men on many of the skills and attitudes associated with women than men overseas; relation-building, flexibility and appreciation for contextual variation were attributes cited both as present to a greater extent in women than in men and as contributing significantly to overseas effectiveness. (p. 29)

Postmodern Views of Identity

Parallel to these gender-related distinctions one finds that models of psychological development (Erikson, 1964; Kegan, 1982) based on research with White men, have consistently emphasized the development of an individuated self, one optimally capable of making increasingly abstract moral decisions (Kohlberg, 1976). Similarly, radical constructivists (von Glasersfeld, 1984; Watzlawick, 1984) describe a self which constructs its own unique meaning from experience and then is responsible for the implications of that meaning. However, for social constructionists (Gergen, 1982; Hoffman, 1993), who claim to offer a postmodern view of identity: “the line between individual and social becomes tenuous … an idea is constructed together with others; then is internalized in the private mind; then rejoins the common mind; and so forth” (Hoffman, 1993, p. 204).

Social psychologists (Hecht et al., 1993) have also proposed an “interpenetration” model of development and say that “the self and society cannot be defined apart from each other.” These latter theorists focus on ethnic and racial identities and highlight the distinction between identities that are “internally defined (subjective, perceived, or private identity) and those that are externally imposed (objective, actual, or public identity).” These views “allow[s] for both the individual and the social perspectives, the dialectic between the levels and the interpenetration of each level as well as structural properties of interactional and societal systems” (Hecht et al., 1993, pp. 42–43).

Similarly, critical theory (Poster, 1989), which is concerned with the sociopolitical dimensions of identity, suggests that human beings “participate willingly at the level of everyday life in the reproduction of their own dehumanization and exploitation” (Giroux, 1983, p. 157) and that society defines and limits self-definition as a means of maintaining dominant cultural paradigms. What they term post-modern “subjectivity” “relates to issues of identity, intentionality and desire (and) is a deeply political issue that is inextricably related to social and cultural forces that extend far beyond the self-consciousness of the so-called humanist” (Giroux, 1991, p. 30). Through the lens of these theories one might say that only members of dominant paradigms can have the luxurious illusion of objectivity or of a self which is free of social realities.

Complexities of Identity

As a final contrast, Myers et al. (1991) examine the “complexity” of the impact of race, gender and ethnicity on identity and suggest that “the optimal conceptual system” is seen as multidimensional: “encompassing ancestors, those yet unborn, nature, and community” (Myers et al., 1991, p. 55) and that it is in connection with the spiritual, rather than individual awareness, that one transcends culture. Social identity theories (Brown & Levinson, 1978; Hardiman & Jackson, 1992; Hecht et al., 1993; Hoare, 1991; Kim, 1981; Phinney, 1990) however, point to the impact of these physiological and social realities on one’s capacity to self-define and negotiate identity, and that even spiritual beliefs are socially constructed.

Perhaps appropriately, Gergen (1982) states:

it is becoming increasingly apparent to investigators in this domain that developmental trajectories over the lifespan are highly variable; neither with respect to psychological functioning nor overt conduct does there appear to be transhistorical generality in lifespan trajectory. … A virtual infinity of developmental forms seems possible, and which form emerges may depend on confluence of particulars, the existence of which is fundamentally unsystematic. (p. 161)

Identity development theory, for example, suggests, that White and Black identity development differ (Hardiman, 1982; Hardiman & Jackson, 1992; Tatum, 1992), as do male and female identity development (Chodorow, 1978; Enns, 1991; Gilligan, 1982), and further that ethnic identity and multiple minority identities create complex variations and alternatives to standard developmental models (Martinez, 1994; Reynolds & Pope, 1991; Root, 1992). Ivey, Ivey and Simek-Morgan (1993) have, in fact, developed a `multicultural cube’ in which some 19 factors: five contextual variables, nine multicultural issues and four developmental stages interact in determining the identity of one individual. Ultimate stages in these various trajectories tend to point to the capacity to integrate cultural identities within oneself, rather than to transcend them as constructivists suggest is possible.

In summary, it appears that to speak of multicultural identity apart from social realities is increasingly difficult once one focuses on non-Western, non-dominant experiences of identity. “Interpenetration” (Asante, 1987) and “interaction” (Hecht et al., 1993, p. 46) tend to bespeak these identity processes.

Interviews With Multicultural People

Research Methodology

The small study discussed here was a further investigation and documentation of the experiences of women and people of color with respect to the experience of multicultural identity. Initial data which contributed to this investigation were approximately 300 essays written for a course mentioned previously entitled “Culture, Identity, and Ethnic Diversity,” taught by the author. In these essays students were to define culture, its influence in their lives and to describe ways culture affected choices they could see themselves making in the future. Having compiled and examined these essays, all written by students with at least 2 years of intercultural experience and having determined that women and people of color articulated experiences at greatest variance from the Adler article, and from the experiences of Anglo-American men, a series of interviews was carried out. While Adler had focused on the experiences of four men, 20 in-depth interviews totaling up to 6 hours for each person were the final source of data for this study.

In addition to interviews with four men who were of Western backgrounds similar to those described by Adler, six other men from more varied ethnic and cultural backgrounds, and 10 women were interviewed. Some were from biracial families, and some were bicultural. All had lived extensively (defined as 2 years minimum) in at least three cultures and were at least bilingual, the criteria used in the initial identification of multicultural people for the study. Respondents came originally from Australia, Canada, China, Colombia, India, Iran, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Malaysia, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Uganda, the United States, Viet Nam, Zaire, Saudi Arabia, and South Africa. Adler speaks of his individuals having “embraced only to let go [of] one frame of reference in favor of yet another.” The premise of this study was that the challenges posed by life in three cultures, complemented by those of operating effectively in at least two languages assured the same kind of shift and the development of a multicultural identity.

Rather than pre-dispose the interviewees to a particular way of describing their experiences, a methodology called “in-depth interviewing,” developed by Irving Seidman (1991) was selected. He notes: “At the root of in-depth interviewing is an interest in understanding the experience of other people and the meaning they make of that experience” (p. 8). The three-part interviews, each part up to 2 hours in length, were intended specifically to help portray a social constructionist view of reality. The interviewer encouraged narrative description to highlight how respondents remember and make meaning of their experiences. In this study, for example, the interviewer began with the query “what is it like to be a multicultural person,” and followed in later interviews with questions relating to their sense of “self.” Seidman insists that only by engaging deeply with a person and by recording and studying the way they construct and explain their experiences can we come to a deeper understanding of human experience and of how meaning is made of human dilemmas.

While he suggests an open-ended form of questioning which “reflectively” (Rogers, 1980) follows the thoughts of the interviewee in exploring a particular issue, the technique of “circular questioning” (Tomm, 1985) was also used. This form of questioning is based on the idea that selves are created in interaction and is intended to highlight contextual and relational aspects of human experience. Rather than suppose that there is one answer to any question the interviewer follows the themes of the interviewee while seeking constantly to contextualize answers. Sample questions in response to the recounting of a particular event might be: did you respond the same way to members of your family when you were in Africa, when you were a student, etc? The interviewer consistently clarifies the contexts and asks for descriptions of interlocutors, and for the degree of which an interviewee would make choices or behave according to consistent values or in relation to contextual variation. While the methodology allowed for the social constructionist view of identity to be expressed, the range of possible answers allowed for the constructivist model of identity to emerge as well, which it did in some instances. In fact, those with views similar to Adler were still able to describe their experiences in ways which denied the impact of context or relationship, while others for who these factors played important roles were allowed to flesh out intricacies of their experiences in ways which more quantitative interview methodologies may not have allowed.

It needs to be noted, however, that there are significant limitations to the study. It was a small, though in-depth study into the lives of only 20 people. More often than not interviewees were not being interviewed in their native languages, and in the majority of the interviews, the interviewer was not of the same race or ethnic background of the interviewee. These factors can be seen to have limited the comfort of the interviewees in describing their life experiences and the reliability of the results. While involvement in some form of intercultural work was a criteria for identifying skilled interculturalists in the selection of the interviewees and they varied widely in terms of their backgrounds, all are or were students, teachers, trainers or managers in one of three contrasting (one urban, one suburban and one rural) college communities. This was significant in that it may also have limited the types of responses received.

There are also limitations to this paper inasmuch as it is difficult in other than thematic and anecdotal ways to describe the human experience described in a qualitative study of this kind. While differences in age, gender, race and class of the respondents in this study provide a contrast to Adler’s work, this paper cannot adequately address the complexity of multicultural experience nor can the conclusions be seen as anything more than suggestions of what is means to be, as were Adler’s men, multicultural within the United States context, or of directions for further study.

Four Women

In his article, Adler described four men, two of whom he had interviewed, and two of contemporary significance, Norman O. Brown and Carlos Castaneda. In further describing the results of this study, representative case studies of four women will be provided. This will be followed by a summary of themes which were highlighted in both the students’ essays and in the interviews conducted.

Case Study 1 Marhaba is a Somali woman in her early twenties. She was born in the United States when her parents were students and was taken with her younger sister, at the age of three, to live with her father’s parents in Tanzania. Her parents finished their studies in the U.S. and later divorced. Five years later she moved with her grandparents to Somalia. Her mother then returned to Somalia and lived both with her own parents and in the house of her ex-husband’s parents with her two daughters. At that point, Marhaba spent time in the homes of both her grandparents. She finished high school at a French lycée, fluent in French, the Swahili of her paternal grandparents, and Somali, and was somewhat familiar with English. As her father had remained in the United States she was able, at the age of sixteen to join him and his new family, to attend a well-known U.S. university and to pursue a Master’s Degree and teaching credential.

At the time she was interviewed she was working supervising teachers and student-teaching. She was proud of her background and yet clearly sensitive to ethnic and cultural differences in the classroom she taught. She expressed anger at her college advisor who seemed racially biased and judgmental towards international students. She was articulate about the experience of change. She spoke of life as “a lottery, like gambling,” because people went from positions of power to jail, from riches to poverty “like a roller coaster” in Somalia. As such she talks about always learning: “there’s always something to learn from here and there’s always something to learn from home.

Case Study 2 To Duc Hanh is a Vietnamese woman, 63 years old at the time of the interview. She was schooled in a French Catholic boarding school in Viet Nam and later attended university at the Sorbonne. In France she married a Vietnamese man and returned to Viet Nam to raise a family. She later divorced and in 1975 escaped Viet Nam and has lived for the past 18 years in California. She has received a doctoral degree in education from the University of California at Berkeley and currently teaches multicultural education to teachers of LEP (Limited English Proficiency) students. Holding herself graciously and speaking in an educated English, she refers often in conversation to French philosophers and American psychologists, and speaks enthusiastically of Vietnamese poetry and music:

there is no such thing as “I” in Vietnamese … we define ourselves in relationship … if I talk to my mother, the “I” for me is “daughter.” the you is for mother, it’s in a relationship always. If I talk to my children the mother would be me and the daughter or son would be them.

As she speaks of her present life in the United States, however, she notes a change:

Since the elements and the needs of my family are changing then my responsibilities and duties are changing and so I change: I perceive myself as creating my own identity … and a person who is choosing and creating my own self.

Case Study 3 Ayse is an ethnic East Indian woman who was raised in Uganda and was forced, as a teenager, to leave in 1972. As a refugee, she worked initially in a chicken factory in England and later attended secondary school there. In 1975, she was able to join her family in Canada where she attended University. Having received her Master’s Degree in the U.S., she is in her early forties and teaches English as a Second Language in Canada. She speaks articulately about the place of language in her identity. At home, she says she spoke Kachi, bastardized with Swahili. Though she rarely uses them now, she grew up speaking Hindi and Gujarati as well. At her father’s garage in Uganda she spoke Swahili and in school and all during her studies she has used English.

Though her accent in recognizably East Indian she notes that, never having been to India, she feels far closer to Africa, though it is her Muslim faith which she refers to as home. She has married a man of her same faith who similarly escaped from Uganda to England and finally, Canada. In their shared faith and relationship she notes, she is most herself. She grants her faith credit for the strength needed to endure her painful life as refugee, and for the opportunity to earn a Master’s Degree now to be a teacher of Afghani refugees.

Case Study 4 Susanna Harrington was born in South America and lived and travelled with her family throughout the continent as the child of a diplomat. As a teenager she travelled frequently between counties after her parents’ divorce. More recently, she has married an American man, received her Master’s Degree in the U.S. and works as a teacher of English as a Second Language in an American high school. Many of her students are Hispanic, mainly Puerto Ricans. She speaks compellingly of her shock at the ignorance of her first American students who assumed all Hispanics were servants or laborers and with sadness at the effects of her parents’ divorce. Now in her thirties, she is enthusiastic about her young daughter, takes great solace in her relationship to her husband and his family, and is inspired by the commitment to humanity she shares with them:

I have learned to deal better with issues of power. I am aware that I have been the oppressor and the oppressed in different instances in my life. It is my intention to strive for equality in the classroom and to avoid imposing my agenda or power on students.

Analysis of Interviews and Essays

These women reflect the numerous factors and complexities involved in multicultural experience. Education, divorce, political turmoil and diplomacy along with economic fluctuations, intermarriage, business and tourism combine in infinite ways to provide the impetus for individuals to take on multicultural lives. The very fact that this study included the experiences of women and people of color meant also that the sociopolitical dimensions of identity came to light in most interviews. A woman of nobility and prestige in her home country had to struggle with visa problems and racism as an instructor at a Southern university. Another woman from a comfortable middle class family suffered the degradation of a grueling factory job as a refugee. Similarly, women in intercultural partnerships found themselves without the familiar support of customs to support their expectations of their partners.

Nonetheless, it was obvious, both from the students’ essays and from the interviews with men that Adler’s portrait of multicultural men was in many ways accurate. All the Western men expressly articulated an aspect of the experience of marginality, especially as a sense of detachment. While women spoke of reconnecting with the religions, languages and ethnic traditions they had grown up with, the men interviewed tended, like Adler’s men, to find connection and integration through the kinds of mental exercises described by Bennett (1979) and George Kelly (1955): “the creative capacity of the living thing to represent the environment, not merely to respond (author’s italics) to it … (to) do something about it if it doesn’t suit him” (Kelly, 1955, p. 15).

One man, of Caribbean origin found his belonging in an Eastern religious practice, a Saudi man in Hindu poetry, a Japanese man in Western philosophy. Similar to Adler’s four men, the four Western men interviewed had each chosen lives apart from their native cultures yet linked to some form of intercultural communication. In reviewing both the essays and the other experiences described for this study, however, significant differences began to emerge and transcripts were culled for themes common to all or most of the respondents.

There were differences in the ways marginality was described as well as in the ways individuals managed entry into new situations. The “marginality” mentioned by non-dominant respondents came more often in relation to lack of privilege within particular social contexts than to an abiding sense of “marginal” identity per se. Similarly, while they articulately spoke of their learned abilities to shift in relation to their surroundings, most all defined themselves in terms of their genders, families, their languages and religions and, often, in relation to the expectations of different contexts. While able to transcend cultural viewpoints and adjust to cultural differences, they viewed themselves as significantly rooted in the customs and values of certain communities and as committed using their global contacts to improve those same communities. Ayse, for example, maintained her commitment to the Muslin community even while living in Canada, Hanh to Vietnamese refugees while living in California.

Experiences With Sexism, Racism, Prejudice and Stereotyping

Some people patronize you, some want to protect you, some want to ignore you or ignore part of you … and I am aware of their attitude and say that’s the way they are and that is where they are at this moment in their life.

(Hahn, see Section 2.2.2.)

M. Bennett’s (1993) work suggests that this experience of not being accepted is a type of marginality which can be transcended by the development of intercultural sensitivity which, in turn, helps them “construe the experience of personal ‘differentness’ as a natural outgrowth of highly developed sensitivity to cultural relativity” (p. 65) and that “if there is to be a ‘meta-ethic’ (Barnlund, 1979) that can restrain … cultural-value conflict and guide respectful dialogue, it must come from those whose allegiance is only to life itself” (p. 65).

Women, in particular, however, in spite of their commitments to intercultural communication spoke consistently of their identities in relation to contexts of being excluded or included on the basis of their race, religion, ethnicity and gender. A biracial woman wrote in her essay:

I ponder if others see me first as a Black woman and then as a person who eats, drinks, breathes, etc.

Regardless of their self-perceptions both men and women of color inevitably mentioned having had to struggle in the United States with the focus on race and ethnicity. Often having originated in cultures where they were members of the majority, and in some cases of the elite, this shift to minority status had often been unanticipated. For Susanna, for example, whose life within a diplomatic family had taught and allowed her the vantage point of the type of intermediary described by Adler and Bennett, it was a painful realization that her role as a teacher was limited by her students’ assumptions that she was a Hispanic immigrant and by their prejudices associated with this stereotype.

Another example of this forced awareness came to light in interviews with three black Africans. For all three, coming to the United States was disturbing as they were unaccustomed to a culture adapted so much to Whiteness. Not only did they struggle in mundane ways, e.g. finding cosmetics and hair products to fit their needs but they described the stereotyping of African Americans in our society as more exaggerated than in their countries. Having come from post-colonial countries where blacks are dominant, two were able to keep perspective on their experiences and maintain a sense of self-esteem. For one Zairean woman who comes from nobility in her native culture and who lives and teaches in a large urban setting, the issue of maintaining self-esteem in the face of constant oppression is an abiding issue. She sees her and her husband’s struggles with lawyers and employment as at least partially caused by racism. Similarly, a Kenyan woman consciously made choices to choose relationships with Africans and European Americans before struggling with the dilemmas raised as they confronted the experiences of African Americans in the U.S. A third, a South African man, who had grown up under apartheid, who had developed a sense of self-esteem in the anti-apartheid movement, had the capacity to maintain a very strong commitment to South African nationalism and still work with European Americans doing anti-oppression and literacy work in the U.S.

Similarly, three others of international backgrounds, who had grown up with privilege, were initially shocked by the prejudice and racism they encountered because of their lack of linguistic competence and ethnic backgrounds. Hanh still reports frustration at the attitudes of people she meets:

I have been here 18 years and if somebody had been to Viet Nam and spoke the language they would think they knew that country very well. Americans are still WHITE AMERICA. Anglo-America. Americans still think of me as a foreigner. You see even though I’m a citizen and I’ve been here some are still very surprised that I know English, use funny words and joke in English. They say how did you do it. Eighteen years and they can’t believe I know all of that?

Many of the women also spoke of having been abused, others of having been denied privileges both in their native cultures and in North America because of their gender. Their multicultural perspectives did not exempt them from the perceptions of women and people of color held by their various host cultures. Hanh reported:

I was married to a man who was extremely traditional. Coming back from France, he was for the first 3 years the perfect French gentleman, then he became again the master of the house and wanted me to obey him.

The woman from Zaire commented on her experience as a professional in a way that was reflective of some of the other women’s experiences as well:

I had a job at the university teaching men. Women would see me as smart and send me to sit with the men and superior. So I needed to sit with the men and discuss with them. So I would discuss with them and they would tell me I’m still a woman. So I didn’t have any place where I could identify myself.

Struggles with prejudice were reported again and again as women accustomed to privilege and status confronted oppressive sociopolitical realities. These realities and the experiences of marginality they caused posed a harsh contrast to the privileged men in the Adler article, whose multicultural experiences were a result of choice and education, and whose marginality was a “style of self-consciousness” (Adler, 1977, p. 26).

Ayse, having lived through many difficult experiences, stated firmly:

I may behave differently, I may try to fit into the mold but … over the years I have come to know that I will not be pushed down, I will not be trampled … you respect who I am and I will respect you.

While this firmness of stance reflects the type of self-reflectiveness encouraged by Bennett it also reflects the constant social pressures on those with non-dominant status. It also suggests that while ``mediation … (is) accomplished best by someone not enmeshed in any reference group (Bennett)’’ we must also consider the extent to which social realities limit the choice and options of mediators and examine critically the fact that most successful international mediators are currently male.

Shifting Identities According to Context

The multicultural style of identity is premised on a fluid, dynamic movement of the self, an ability to move in and out of contexts, and an ability to maintain some inner coherence through varieties of situations.

(Adler, 1977, p. 37)

Respondents, both in essays and interviews within this study, also spoke of their experiences of constructing new identities, but always within existing cultural definitions. While many spoke specifically of the influence of language proficiency on their adjustment and comfort in new cultures, there was also frequent mention of the concept of an almost chameleon-like capacity to blend in and become harmonious with different settings. Susanna describes this well:

I think of myself not as a unified cultural being but as a communion of different cultural beings. Due to the fact that I have spent time in different cultural environments I have developed several cultural identities that diverge and converge according to the need of the moment.

Shifts in identity seemed to happen intuitively and many seemed to take this capacity for granted. Another woman, for example, involved in a bicultural marriage entitled her essay: “The phone is ringing, who will I be?,” indicating the extent to which the person with whom she was about to communicate determined a temporary identity. Other women asked such questions to help them respond, as “in what setting,” “give me an example of a situation.” For the women in this study their concepts of identity were statements of relationship. In contrast to Adler’s men who saw themselves as somewhat empowered to choose which milieus would affect them, these women saw themselves as choosing who and how to be in whatever relationship and often considered others as holding or wielding power from which they might be excluded. This adjustment was sometimes described as painful. One Anglo-American student gave her essay the title “Where can I really be me?,” as she felt her marriage to a man from another culture asked to give up aspects of self which had had importance. Marhaba states fatalistically:

I don’t think people change who they are. You can try to change but I think I am still the same person … but I’m aware. I can never change who I am but I can change my awareness. I’m with this person now and I’m going to be careful how I handle this because I don’t know how I’m going to handle it but I am aware.

A question the interviewer asked of all the interviewees was whether or where there was a place where they felt they were completely themselves. One woman flipped the response in a way that was reflective of many others, responding that she would more accurately respond to a question phrased: “With whom or where do you like best, the person who you find yourself being?” For most respondents, in fact, responses affirmed a recognition that who they were was a reflection of the situation in which they found themselves. For many, for example, it was “at home,” for others it was a place where there were other interculturalists, for others it was a place or relationship which allowed them to express more fully all the parts of themselves. In some accounts there was a sense of satisfaction that they had “become a better person” in new contexts but, concomitantly, that that identity could exist only in the new context. An example of this was clear in the accounts of a Malaysian woman who had been increasingly abused by her husband and abandoned by her parents as she achieved success as a professor in Malaysia and yet was dismayed by the extent to which these same achievements were taken for granted in an American university setting.

For the multicultural women in this study, context, at least as much, if not more than any cognitive capacity for self reflection, affected their social identity, self-esteem, and experiences of marginality as well. Overall these responses reflect views of identity which are interactive with and responsive to context, in which the construction of identity is less conscious than it is intuitive, and wherein self-awareness comes after the fact as reflection, rather than as a “choice” in immediate response to a new context.

Having Deep Roots

Adler ends his article with a quote from Harold Taylor (1969) which states that “There is a new kind of man in the world, conscious of the age that is past and aware of the one now in being, aware of the radical differences between the two” (p. 39). Implicit in this statement is the “willingness to accept the lack of precedent” or as von Glasersfeld (1984) proposes, the existence of “cognitive organisms that are capable of constructing for themselves, on the basis of their own experience, a more or less reliable world” (p. 38). Similar to Adler and Bennett these authors propose the existence of a mental, imaginative capacity to transcend reality and construct new possibilities.

While every woman interviewed was committed to some form of global transformation, they also spoke of the importance of family, relationships, and community. Mostly women of color, they saw themselves as socially marginal to dominant cultures in many instances but rather than valuing that marginality as a form of freedom or opportunity for detachment, they worked to redefine their lives, relationships, and communities to create and foster a sense of belonging. Marhaba speaks of her race:

For a person who’s black … it’s very important for someone not to disregard it. [it’s ridiculous to] say we are human beings and the other things (just) come with it.

and a Latin American woman of her gender, “I guess, at core, I am a mother, a daughter and ultimately, a woman.”

All female respondents, in fact, used concepts such as “rootedness” or “belonging” to describe themselves and talked, without exception of the challenges of connecting with others and of not judging others who failed to treat them with respect. The respondents had all demonstrated competence through their professions and had worked effectively in intercultural settings. Many spoke of grounding their lives in meaningful relationships. One woman spoke at length of her ethnicity and religion as central to her life, as a focus from which she could embrace others. Another spoke of the importance of settling down, having a family and living in community as essential for her as she continued her work in intercultural settings. Ayse notes:

As a result of all these differences and having been forced to adapt to this new culture, I have developed another cultural identity which is capable of surviving in this new environment but that has its roots in the past. This identity functions like a second personality that appears when it is necessary to adopt a culturally appropriate behavior in the new culture.

Two women who had been refugees spoke of parts of themselves which were developed in their native cultures and which they had found ways of nurturing in their new environments, largely through associating with members of their native cultures. The Zairean woman said clearly:

That’s my roots, that’s where I come from, that speaks to me, that is home, although I feel very much a citizen of the world.

When asked if she ever feels marginal or disconnected, Ayse notes that she doesn’t think of connection abstractly as much as in terms of groups or individuals:

I can always connect with some people. I start with one or two rather than with groups.

Adler (1977) described multicultural man as “a person who is always in the process of becoming a part of and apart from a given cultural context” (p. 31). The women in this study, on the other hand, clearly strive to root themselves in aspects of their identity which give them a sense of power and possibility. For some women it was their relationships to their families that provided a “sense of home”; for many women of color it was a commitment and bond with others of their race or ethnic background; for others, it was their religion; for others, their work. Ayse remarks:

While I am aware that I am visibly different from others I have found many things in others which are the same.

Commitment to Others

A strength of multicultural women is their capacity to reflect on and work with sociopolitical realities. By virtue of their life experiences the women in the study had become aware of themselves and their capacities as well as of the extent to which sociopolitical realities affect their lives. The receptivity and support of their host communities, or, alternatively, the prejudice or hostility found in different contexts and relationships shaped aspects of their identities and served to either foster or prevent growth in certain areas. To some extent each one had found an identity through teaching which allowed them to relate to others and serve as guides in the multicultural realities of their students. Having successfully negotiated the storms of cultural adjustment and language acquisition, these women had discovered a variety of ways to help others with the same challenges. While some were motivated by a certain degree of anger, others by a need for self-sufficiency, all spoke of a compelling desire and commitment to make their experiences of use to others.

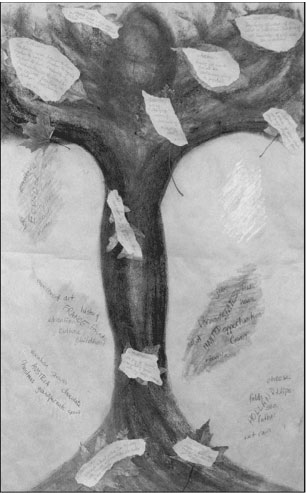

An Alternative Image

While a clear-cut graphic design was chosen by Adler to portray the solitary concept of identity described by Adler, definitions of self of the women interviewed suggest a more organic image, perhaps a plant or tree rooted and grounded in aspects of self which connect them to others and to community. The image in Fig. 25.1 was created life-size by a female student depicting her identity for an intercultural communications course. Just as Adler’s men claim multifaceted and evolving identities, women tend to move from their grounding in gender, ethnicity, religion and race into the multiple and dynamic circumstances which serve to further affect and shape their identities. The women interviewed in this small study spoke repeatedly in metaphors reminiscent of roots which grow deeper and deeper as allowed by the receptiveness, or “soil” of a situation. One older woman found she worked more and more to develop connections to her native culture as she grew older, realizing that the strength she gained allowed her to grow and to reach more deeply into and appreciate aspects of American culture as well.

The image of a tree to depict multicultural women’s identity, whose commitments are strengthened as they deepen their connections and roots in community also suggests a contrast to the marginal men of Adler’s article who stand outside relationship to maintain their senses of self. Much like biological trees, the length of whose roots into the earth and height above the earth are often equivalent in, these multicultural women reflect uniquely adapted identities and commitments to global interaction. Just as trees adjust their growth to climate and season, women’s ways of expressing themselves grow in relation to their experiences of relationship and community. Similarly, the intricate root and branch systems which grow in relationship to the soil and elements, reflect the dynamic complexity and individuality of organisms whose development happens in relationship to context, a concept essential to biological models of development (Maturana & Varela, 1987) as well and suggestive of the more chaotic view of communication. According to Barnlund’s (1981) ecological approach to communication, “the environmental dimension deserves far more attention than it receives” (p. 124). This is echoed in the interviews which embody identities profoundly affected by their relations to interpersonal experiences and sociopolitical realities.

Further Considerations

For interculturalists, maintaining a positive self concept is an essential challenge. While this small study offers some insights into the relation of sociopolitical realities to the self-definitions of multicultural persons, four issues present themselves for further consideration. “Marginality,” “in-betweenness,” and “uniqueness” are terms used by Adler, Bennett, and radical constructivists to highlight a definition of a highly individuated and optimal human capable of mediating effectively between cultures. “Commitment” is similarly used in reference to human unity, rather than to specific communities. These terms take on new meaning in the lives of women and people of color and are deserving of further research, as will be briefly discussed below.

Figure 25.1 An Alternative View of Multicultural Identity.

Marginality

Marginality, the concept that “in each human being there obtains a core which is separable and different from everything else” and its concomitant “reflexivity; the self is aware of itself as a self” (Balagangadara, 1988) is central to the work of interculturalists (Adler, 1977; J. M. Bennett, 1993; M. J. Bennett, 1993) and is fundamental to constructivism (Watzlawick, 1984), upon which so much of intercultural communication theory is based. This small study would suggest that men are more likely to have that sense of separateness and that that is in part a result of their dominant status in Western societies.

As such, definitions of self are inextricably linked to the cultures and languages as they describe the self, and within those cultures and languages, the freedom to define oneself is dependent on relationships of power: “Our beliefs and values are inextricably caught up in networks of power and desire, and resistance to power and desire” (Gee, 1990, p. iii). For the women in this study, context, these “networks of power and desire,” affect their social identity, self-esteem and experiences of marginality at least as much, if not more than, any cognitive capacity for self-reflection.

In-Betweenness

This brief study also suggests that most multicultural people will inevitably experience minority status in the course of their lives, and will be affected, as were the women in this study, by the rocky soils of human interaction. While the work of Adler states that the experience of multiculturalism as such results in “in-between attitudes” (Dawson, 1969) or “dynamic in-betweenness” (Yoshikawa, 1987), the experiences of the respondents in this study suggest otherwise. Social identity theories (Banks, 1988; Hardiman & Jackson, 1992; Myers et al., 1991) also suggest that the final stages of identity development are instead integrative, and that the “in-betweenness” is a stage preceding the optimal, similar to that of Janet Bennett’s “encapsulated marginality” (J.

M. Bennett, 1993). This suggests that the re-connection to one’s social identities from a vantage point of appreciation and belonging is necessary both for self-esteem and for professional work with and beyond issues of prejudice and exclusion.

Furthermore, “empathy” (Bennett, 1979; Fantini, 1991; Kealey 1990) is often on the list of characteristics of effective interculturalists. While Bennett (1979) has suggested this “empathy” can be learned as an intuitive imaginative skill, respondents in this study suggest that women with multicultural backgrounds are most effective in communities of belonging to which they have personal connection and experience. Similarly Parker and McEvoy (1993) found that “prior international experience and the amount of time spent with host country nationals” (p. 374) facilitate both cultural adjustment and work effectiveness. This research highlights that true empathy and interpersonal skills rise naturally and organically from healthy relationships with one’s own family and communities of origin and from a commitment to significant interaction with others.

Uniqueness

The results of this study suggest that multicultural identity as a “sense of uniqueness” can have as much to do with the contextual variations in which humans find themselves, and with the linguistic competency and strategies for appropriate interaction which they have learned, as with an unusual capacity for cognitive or emotional detachment.

An interesting variation on the experience of uniqueness was articulated in the interview with a Russian woman, who was later in life identified as “gifted,” as she described her struggles as an adolescent within a restrictive educational system. As two of Adler’s men might be classified as “geniuses” within our culture’s definitions, and gifted in the “psychophilosophical” domain described by Adler (1977, p. 29), other research (Csikszentmihaly, Rathunde & Whalen, 1993) might consider giftedness in relationship to experience of uniqueness. The “very gifted” often interact in rarefied margins of society and typically struggle with issues of belonging. Whether this capacity for complex cognitive creativity is the same as a multicultural perspective deserves further investigation.

Furthermore, it became clear in this study that individuals develop in a variety of ways, depending on almost infinite variables, and that their ways of understanding and describing their development can vary significantly. Gender, religion, racial and ethnic backgrounds, socioeconomic status and language competence all interact within specific contextual realities to configure personal and social identities. We might then expect that the definitions of self will be as varied as the cultures and subcultures whose languages describe them, and that there will be increasing variations on the experience of multiculturalism and perhaps a need for a “chaos theory” of identity. Jenkins suggested, in fact, that there is no one analysis, no final set of units, no one set of relations, no claim to reducibility, in short no unified account of anything (Jenkins, 1974, p. 787), and Barnlund (1981) proposed that: “The study of human communication concerns the process by which meanings are formed within and among people and the conditions that determine their character and consequences” (p. 92) He further urges: “Two caveats are in order: One is that figure and ground are essential to each other: without figure there is no ground and without ground no figure is discernible” (p. 93).

Similarly the experiences of the people in this study would suggest that uniqueness exists only in relation to something recognized as familiar. For most people in this study their capacity to work effectively depended on their relationship to their context and host culture, and in turn that the more clearly they could define who they were in terms of social variables and context, the more clearly they were able to define and articulate universal values which they hoped to embody and promote.

Commitment to Community Action

Although M. Bennett’s (1993) statement that “cultural mediation … be accomplished best by someone … not enmeshed in any reference group” (p. 65) and Adler’s (1977) that “these ‘mediating’ individuals incorporate the essential characteristics of multicultural man” (p. 38) may be seen as an ideal; members of non-dominant groups may, nonetheless, be unable to fulfill them because of the identities ascribed to them in specific contexts. Janet Bennett’s portrayal of Barack Obama effectively portrays the former characteristics, yet he is beset by conflict within his circumstances:

European-American students complain that too much attention is paid to his race: African American students are angered that he failed to select more African-Americans for positions at the Review. Some question his motives … some point to his record of social responsibility and apparent commitment to community work and political affairs.

Nonetheless, respondents in this study portray another form of effective intercultural endeavor, one highly referenced to community yet holding the vision of enhanced possibilities gained from broader social experience. Nancy Adler’s work (1997) researching global women leaders also suggests that women leaders often, in fact, symbolize unity and connection within their own countries while also demonstrating the capacity to work effectively internationally:

Chamorro’s ability to bring all the members of her family together for Sunday dinner each week achieved near legendary status in Nicaragua (Saint-Germain, 1993, p. 80) … (and) Aquino, as widow of the slain opposition leader was seen as the only person who could credibly unify the people of the Philippines following Benigno Aquino’s death.

(pp. 23–24)

The lives of Waangari Maatai in Kenya and Vezna Terselic in Croatia provide a similar contrast. Having started the “Green Belt Movement” in Africa, a widespread movement of women planting trees to re-engender the wildlife and lifestyle of Kenyans, Maatai has now gone on to become a global leader in environmental circles and thus, a prominent Kenyan political figure. Similarly, Terselic, who is coordinator of the Anti-War Campaign in Croatia, an organization whose purpose is the mediating of grievances incurred during the recent war, has been nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize and has gained global stature for her commitment to the peaceful resolution of global conflict. The people in this study point also to the importance of balancing “dynamic in-betweenness” (Yoshikawa, 1987) with the motivation and commitment to work with one’s local communities for positive social change.

The second purpose of this study was the identification of characteristics essential to working effectively within international and multicultural communities and a deeply rooted understanding of the uniqueness and potentials of individual communities becomes immediately evident in the successful commitments of the respondents in this study. Community development theory also points inevitably to issues of appropriateness and sustainability, both logical extensions of these attributes. In concert with an appreciation for other realities, and an experienced view of the global condition, this sense of belonging and commitment might ultimately provide the type of integrative action and commitment needed in the current complex global environment.

Conclusion

This paper began with the articulation of the concerns voiced by students in a course on cultural identity, who claimed that the 1977 article by Peter Adler on multicultural identity did not adequately address the complexities of this experience. Similarly, the review of related literature called for deeper exploration into the factors that influence multicultural identity development. Analysis of the contents of student essays and interviews with multicultural people highlighted gender differences and the ways in which multicultural people define marginality, shift their identities, define their roots and ultimately commit to lives of service to others. Ultimately, the terms marginality, in-betweenness and uniqueness as they relate to multicultural identity are in need of further consideration. There must also be a broader investigation of the nature and value of multicultural experience and identity than that described in Adler’s 1977 article, one more in line with post-modern views of chaos, relativity and social constructionism. While the Cartesian capacities for objectivity, detachment, and cognitive sophistication which he described are valuable attributes in an interculturalist, the results of this study and its brief investigation of research into non-Western and multicultural identity development theories suggest that the capacity for subjectivity, connection and commitment to specific communities provide an important complement to Adler’s ideas. It is hoped that this study will suggest the importance of ongoing exploration of multiculturalism and its relationship to positive social change.

References

Adler, P. S. (1977). Beyond cultural identity: Reflections on cultural and multicultural man. In R. W. Brislin (Ed.), Culture learning: Concepts, application and research (pp. 24–41). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Asante, M. K. (1987). The Afrocentric idea. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Balagangadara, S. N. (1988). Comparative anthropology and moral domains: An essay on selfless morality and the moral self. Cultural Dynamics, 1(1), 98–128.

Banks, J. A. (1988). Multiethnic education: Theory and practice. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Barnlund, D. C. (1981). Toward an ecology of communication. In C. Wilder-Mott & J. H. Weakland (Eds.), Rigor and imagination: Essays from the legacy of Gregory Bateson (pp. 87–126). New York: Praeger.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine.

Benack, S. (1982). The coding of dimensions of epistemological thought in young men and women. Moral Education Forum, 7, 3–24.

Belenky, M. J., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing. New York: Basic Books.

Bennett, J. M. (1993). Cultural marginality: Identity issues in intercultural training. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (2nd ed., pp. 109–135). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Bennett, M. J. (1979). Overcoming the golden rule: Sympathy and empathy. In D. Nimmo (Ed.), Communication year-book (Vol. 3, pp. 407–422). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

Bennett, M. J. (1993). Towards ethnorelativism: A developmental model of intercultural sensitivity. In R. M. Paige (Ed.), Education for the intercultural experience (2nd ed., pp. 21–71). Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. (1978). Universals in language usage: Politeness phenomena. In E. Goody (Ed.), Questions and politeness (pp. 56–289). London: Cambridge University Press.

Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering: Psychoanalysis and the sociology of gender. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Collier, M. J., & Thomas, M. (1988). Cultural identity: An interpretive perspective. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication [International and Intercultural Communication Annual, Vol. 12] (pp. 99–120). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Csikszentmihaly, M., Rathunde, K., & Whalen, S. (1993). Talented teenagers: The roots of success and failure. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Dawson, J. L. M. (1969). Attitude change and conflict. Australian Journal of Psychology, 21, 101–116.

Enns, C. Z. (1991). The “new” relationship models of women’s identity: A review and critique for counselors. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69, 209–217.

Erikson, E. H. (1964). Insight and responsibility. New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

Fantini, A. E. (1991). Becoming better global citizens: The promise of intercultural competence. Adult Learning, 2(5), 15–19.

Freire, P. (1985). The politics of education: Culture, power, and liberation. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Gee, J. (1990). Social linguistics and literacies: Ideology in discourses. Bristol, PA: Falmer Press.

Geertz, C. (1976). From the native’s point of view: On the nature of anthropological understanding. In K. H. Basso & H. A. Selby (Eds.), Meaning in anthropology (pp. 221–237). Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press.

Gergen, K. J. (1982). Towards transformation in social knowledge. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Gergen, K. J., & Davis, K. E. (1985). The social construction of the person. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Giroux, H. (1983). Theory and resistance in education: A pedagogy for the opposition. South Hadley, MA: Bargin & Garvey.

Giroux, H. (1991). Postmodernism, feminism, and cultural politics: Redrawing educational boundaries. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Hardiman, R. (1982). White identity development: A process-oriented model for describing the racial consciousness of White Americans. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Hardiman, R., & Jackson, B. W. (1992). Racial identity development: Understanding racial dynamics in college classrooms and on campus. In M. Adams (Ed.), Promoting diversity in college classrooms: Innovative responses for the curriculum, faculty, and institutions (pp. 21–37). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hecht, M. L., Collier, M. J., & Ribeau, S. A. (1993). African American communication: Ethnic identity and cultural interpretation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hoare, C. (1991). Psychological identity development and cultural others. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 45–53.

Hoffman, L. (1993). Exchanging voices: A collaborative approach to family therapy. London: Karnac Books.

hooks, b. (1990). Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston, MA: South End Press.

Ivey, A., Ivey, M. B., & Simek-Morgan, L. (1993). Counseling and psychotherapy: A multicultural perspective. Needham Heights, MA: Simon & Schuster.

Jenkins, J. (1974). Remember that old theory of memory, well, forget it? American Psychologist, 29, 785–795.

Josselson, R. (1987). Finding herself: Pathways to identity development in women. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kakar, S. (1989). Intimate relations: Exploring Indian sexuality. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kakar, S. (1991). Western science, Eastern minds. The Wilson Quarterly, 15(1), 109–116.

Katz, J. H. (1985). The sociopolitical nature of counseling. The Counseling Psychologist, 13(4), 615–624.

Kealey, D. J. (1990). Cross-cultural effectiveness: A study of Canadian technical advisors overseas. Quebec: Canadian International Development Agency.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kelly, G. A. (1955). A theory of personality. New York: Norton.

Kim, J. (1981). Process of Asian American identity development: A study of Japanese American women’s perception of their struggle to achieve positive identities as Americans of Asian Ancestry. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Kohlberg, L. (1976). Moral stages and moralization: The cognitive-developmental approach. In T. Lickona (Ed.), Moral development and behavior: Theory, research and social issues (pp. 31–53). New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Leung, E. K. (1990). Early risks: Transition from culturally/linguistically diverse homes to formal schooling. Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minority Students, 7, 35–51.

Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Knopf.

Loevinger, J. (1962). Ego development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Martinez, I. (1994). Quien soy? Who am I? Identity issues for Puerto Rican adolescents. In P. E. Salett & D. R. Koslow (Eds.), Race, ethnicity and self: Identity in multicultural perspective (pp. 89–116). Washington, DC: National Multicultural Institute.

Maturana, H. R., & Varela, F. J. (1987). The tree of knowledge: The biological roots of human understanding. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (1985). The dimensions of expatriate acculturation: A review. Academy of Management Review, 10, 39–47.

Miller, J. B. (1986). Toward a new psychology of women (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Beacon.

Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Myers, L., Speight, S., Highlen, P., Cox, C., Reynolds, A., Adams, E., & Hanley, C. (1991). Identity development and worldview: Toward an optimal conceptualization. Journal of Counseling and Development, 70, 54–63.

Nieto, S. (1992). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of multicultural education. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Parker, B., & McEvoy, G. M. (1993). Initial examination of a model of intercultural adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 17(3), 355–379.

Perry, W. G. (1970). Forms of intellectual and ethical development in the college years. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Phinney, J. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 499–514.

Poster, M. (1989). Critical theory and poststructuralism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.