Thinking Dialectically About Culture and Communication

In this chapter, Judith N. Martin and Thomas K. Nakayama advocate the dialectical approach to contemporary research on culture and communication. They offer a comprehensive review of four existing paradigms of intercultural communication: (1) functionalist, (2) interpretive, (3) critical-humanistic, and (4) critical-structuralist in light of the research goal, the intellectual root, the conceptualization of culture, and the relationship between culture and communication. Then, they envision four different ways of research collaboration among paradigms: (1) liberal pluralism, (2) inter-paradigmatic borrowing, (3) multi-paradigmatic collaboration, and (4) a dialectical perspective. It is the argument of Martin and Nakayama that the dialectical approach to culture and communication phenomena offers the possibility of simultaneously engaging in multiple research paradigms. In their view, such a combined and integrative approach is better equipped to account for six dialectics in intercultural interactions: (1) cultural-individual, (2) personal/social–contextual, (3) differences–similarities, (4) static–dynamic, (5) present-future/history-past, and (6) privilege–disadvantage dialectics.

A survey of contemporary research reveals distinct and competing approached to the study of culture and communication, including cross-cultural, intercultural, and intracultural communication studies (Asante & Gudykunst, 1989; Y. Y. Kim, 1984).1. Culture and communication studies also reflect important metatheoretical differences in epistemology, ontology, assumptions about human nature, methodology, and research goals as well as differing conceptualizations of culture and communication, and the relationship between culture and communication. In addition, questions about the role of power and research application often lead to value-laden debates about right and wrong ways to conduct research. Whereas these debates signal a maturation of the field, they can be needlessly divisive when scholars use one set of paradigmatic criteria to evaluate research based on different paradigmatic assumptions (Deetz, 1996). The purpose of this essay is to focus attention on the metatheoretical issues and conceptualizations that underlie these various debates and to explore strategies for constructive interparadigmatic discussions.

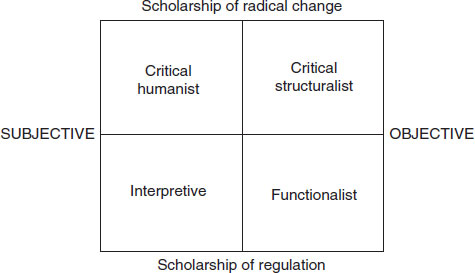

In order to highlight the various metatheoretical assumptions of culture and communication research, we first identify four research paradigms based on Burrell and Morgan’s (1988) framework categorizing sociological research. Although this framework has been borrowed often by communication researchers and provides a useful “map” to differentiate and legitimate theoretical research, a word of caution is in order. As Deetz (1996) notes, Burrell and Morgan’s emphasis on the incommensurability of these paradigms has resulted in a tendency to reify research approaches and has led to “poorly formed conflicts and discussions” (p. 119). Therefore, we present this framework, not as a reified categorization system, but as a way to focus attention on current issues and to legitimate the various approaches.

We will first briefly describe the framework and the resulting four paradigms. For each paradigm, we identify concomitant metatheoretical assumptions and research goals, describe how research in this paradigm conceptualizes culture and the relationship between culture and communication and then give examples of current research conducted from this paradigm. It is important to note that the research examples given are illustrative and do not necessarily reflect the scope and depth of each area.

Four Paradigms

Burrell and Morgan (1988) propose two dimensions for differentiating metatheoretical assumptions of sociological research: assumptions about the nature of social science and assumptions about the nature of society. The assumptions about the nature of social science vary along a subjective–objective dimension, and these categories have been described ad nauseam in communication scholarship (Deetz, 1994). As described by Burrell and Morgan, objectivism assumes a separation of subject (researcher) and object (knowledge), a belief in an external world and human behavior that can be known, described, and predicted, and use of research methodology that maintains this subject-object separation. On the other hand, subjectivist scholarship sees the subject–object relationship not as bifurcated but in productive tension; reality is not external, but internal and “subjective,” and human behavior is creative, voluntary, and discoverable by ideographic methods. Gudykunst and Nishida (1989) used this subjective-objective distinction to categorize then-current culture and communication research.

Burrell and Morgan’s (1988) second and less discussed dimension describes assumptions about the nature of society—in terms of a debate over order and conflict. Research assuming societal order emphasizes stability and regulation, functional coordination and consensus. In contrast, research based on a conflict or “coercion” view of society attempts to “find explanations for radical change, deep-seated structural conflict, modes of domination and structural contradiction” (p. 17).

Figure 12.1 Four Paradigms of Culture and Communication Research (adapted from Burrell & Morgan, 1988, p. 22).

According to Burrell and Morgan, the intersection of these two dimensions yields for distinctive paradigms (see Figure 12.1). They use the term paradigm to mean strongly held worldviews and beliefs that undergird scholarship, using the broadest of the various Kuhnian meanings (Kuhn, 1970). They also identify several caveats: These paradigms are contiguous but separate, have some shared characteristics but different underlying assumptions, and are therefore mutually exclusive (pp. 23–25).

It is important to note that researcher usually adhere more or less to the assumptions of a specific paradigm. For example, as Gudykunst and Nishida (1989) point out, probably no contemporary intercultural communication research is strictly functionalist. Rather, it is more useful to think the boundaries among the four paradigms as irregular and slightly permeable, rather than rigid.

Functionalist Paradigm

As discussed by many communication scholars, functionalist research has its philosophical foundations in the work of social theorists such as Auguste Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Emile Durkheim. It assumes that the social world is composed of knowable empirical facts that exist separate from the researcher and reflects the attempt to apply models and methods of the natural sciences to the study of human behavior (Burrell & Morgan, 1988; Deetz, 1994; Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989; Mumby, 1997). Research investigating culture and communication in this tradition become dominant in the 1980s and is identified by various (and related) labels: functionalist (Ting-Toomey, 1984), analytic-reductionistic-quantitative (Y. Y. Kim, 1984), positivist (Y. Y. Kim, 1988), objective (Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989), and traditional (B. J. Hall, 1992).

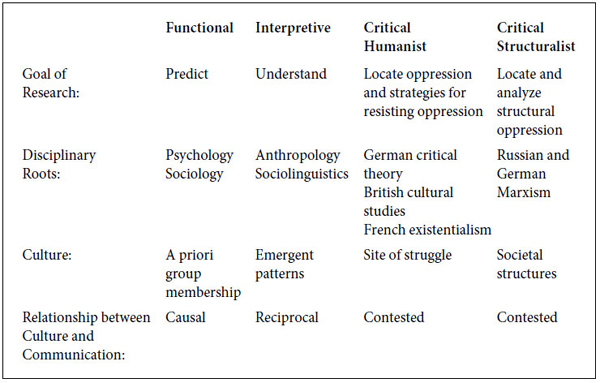

As noted in Figure 12.2, research in this tradition builds on social science research, most notably in psychology and sociology (see Harman & Briggs, 1991). The ultimate goal is sometimes to describe, but often to predict human behavior. From this perspective, culture is often viewed as a variable, defined a prior by group membership many times on a national level (Moon, 1996), and includes an emphasis on the stable and orderly characteristics of culture. The relationship between culture and communication is frequently conceptualized as causal and deterministic. That is, group membership and the related cultural patterns (e.g., values like individualism-collectivism) can theoretically predict behavior (Hofstede, 1991; U. Kim, Triandis, Kăğitçibaşi, Choi, & Yoon, 1994).

Figure 12.2 Four Paradigmatic Approaches to the Study of Culture and Communication.

Research in this paradigm often focuses on extending interpersonal communication theories to intercultural contexts or discovering theoretically based cross-cultural differences in interpersonal communication (Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989; Y. Y. Kim, 1984; Shuter, 1990; Ting-Toomey & Chung, 1996), or both. Researchers have also investigated international and cross-national mediated communication (see McPhail, 1989) and development communication (see Rogers, 1995). Most functionalist research is conducted from an “etic” perspective. That is, a theoretical framework is externally imposed by the researcher and research often involves a search for universals (Brislin, 1993; Headland, Pike, & Harris, 1990; Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989).

Probably the best known and most extensively exemplars of functionalist research programs are those conducted by W. B. Gudykunst and colleagues, extending uncertainty reduction theory (recently labeled anxiety-uncertainty management) to intercultural contexts (Gudykunst, 1995), and communication accommodation theory, a combination of ethnolinguist theory and speech accommodation theory (Gallois, Franklyn-Stokes, Giles, & Coupland, 1988; Gallois, Giles, Jones, Cargile, & Ota, 1995; Giles, Coupland, & Coupland 1991). See also extensions of expectancy violation theory (Burgoon, 1995) and similarity-attraction theory to intercultural contexts (H. J. Kim, 1991).

Another type of functionalist research seeks cross-cultural differences using theoretical constructs like individualism and collectivism as a basis for predicting differences (see U. Kim et al., 1994). For example, Stella Ting-Toomey and colleagues have conducted extensive research identifying cultural differences in face management (Ting-Toomey, 1994) and conflict style (Ting-Toomey, 1986; Ting-Toomey et al., 1991). Min-Sun Kim and colleagues have investigated cultural variations in conversational constraints and style (M.-S. Kim, 1994; M.-S. Kim & Wilson, 1994; M.-S. Kim et al., 1996). For the most recent complication of functionalist research, see Wiseman (1995).

There are a few research programs like Y. Y. Kim (1988, 1995) that do not fit neatly into one category. Although she designates her systems-based theory of cultural adaptation as distinctive from both functionalist and interpretive paradigms (Y. Y. Kim, 1988), one could argue that this theory is based primarily on functional social psychological research on cultural adaptation, and has generated primarily functionalist research (Y. Y. Kim, 1995).

Interpretive Paradigm

Culture and communication research in the interpretive paradigm gained prominence in the late 1980s. As noted in Figure 12.2, interpretive (or “subjective”) researchers are concerned with understanding the world as it is, and describing the subjective, creative communication of individuals, usually using qualitative research methods. The philosophical foundations of this tradition lie in German Idealism (e.g., Kant) and contemporary phenomenology (Merleau-Ponty, 1962), hermeneutics (Dilthey, 1976; Gadamer, 1976, 1989; Schleiermacher, 1977), and symbolic interactionism (Mead, 1934). Interpretivism emphasizes the “knowing mind as an active contributor to the constitution of knowledge” (Mumby, 1997, p. 6). Culture and communication research in this tradition has been described and labeled as interpretive (Ting-Toomey, 1984), holistic-contextual-qualitative (Y. Y. Kim, 1984), humanist (Y. Y. Kim, 1988), and subjective (Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989).

The goal of interpretive research is to understand, rather than predict, human communication behavior. Culture, in the interpretive paradigm, is generally seen as socially constructed and emergent, rather than defined a priori, and it is not limited to nation-state collectives. Similar to functionalist research, interpretivists emphasize the stable, orderly characteristics of culture, reflecting an assumption of the social world as cohesive, ordered, and integrated. Communication is often viewed as patterned codes that serve a communal, unifying function (Carbaugh, 1988a; B. J. Hall, 1992). The relationship between culture and communication is seen as more reciprocal than causal, where culture may influence communication but is also constructed and enacted through communication. Research is often conducted from an “emic” or insider perspective, where the framework and interpretations emerge from the cultural community (Headland, Pike, & Harris, 1990). The interdisciplinary foundations of this research are found in anthropology and sociolinguistics.

The sociolinguistics theory of Dell Hymes (1972) has been particularly influential on the strongest exemplar of interpretive research—ethnography of communication studies conducted by Gerry Philipsen and colleagues. They study cultural communication (vs. inter or cross-cultural communication). That is, their goal is generally to describe communication patterns within one speech community, for example, Philipsen’s (1976) classic study of communication in “Team-sterville,” Donal Carbaugh”s (1988b, 1990a) numerous studies of U.S. (primarily European American) communication patterns, from “talk show communication” to more general studies.

However, some interpretive scholars are interested in intercultural communication, cross-cultural comparisons, or both. See, for example, Braithwaite’s (1990) meta-analysis of the role of silence in many cultural groups, Fitch’s (1994) cross-cultural comparisons of directives, and Katriel’s (1986) studies of Israeli and Arab patterns of speaking, M. J. Collier’s (1991, 1996) work on communication competence, as well as Barnlund and colleagues’ descriptive studies of contrasts between Japanese and European American communication (Barnlund, 1975, 1989).

It should be pointed out that some interpretive research programs reflect functionalist elements, One could argue that Collier’s (1991, 1996) work, Hecht and colleagues’ research on ethnicity and identity (Hecht, Larkey, & Johnson, 1992; Hecht, Collier, & Ribeau, 1993), and Barnlund’s (1989) research on Japanese American contrasts have produced emic, insider descriptions, but also seem to imply behavior as deterministic, sometimes linked a priori to cultural group membership. In addition, some of their studies do explicitly predict behavior, conducted from a functionalist position, but the frameworks and hypotheses are based on previous, emic research findings (e.g., Hecht, Larkey, & Johnson, 1992).

Other examples of interpretive theories are coordinated management of meaning (Cronen, Chen, & Pearce, 1988), rhetorical studies (e.g., Garner’s [1994] and Hamlet’s [1997] descriptions of African American communication. For recent complications of interpretive research, see Carbaugh [1990b] and González, Houston, & Chen [1997]).

Recent culture and communication research reflects a renewed interest in research issues not usually addressed by functionalist or interpretive research. These concerns of context, power, relevance, and the destabilizing aspects of culture have led to research based on the remaining two paradigms.2. First, there seems to be a growing recognition of the importance of understanding contexts of intercultural interaction. Although functionalist researchers sometimes incorporate context as a variable (e.g., Martin, Hammer, & Bradford, 1994), and interpretive researchers address “micro” contexts, there has been little attention paid to larger, macro contexts: the historical, social, and political contexts in which intercultural encounters take place (an exception is Katriel, 1995).

Secondly, there is an increasing emphasis on the role of power in intercultural communication interaction and research, reflecting current debates among many communication scholars (Deetz, 1996; Mumby, 1997). In functionalist research, power is sometimes incorporated as a variable (see Gallois et al., 1995) and is alluded to in some interpretive research, e.g., Orbe’s (1994, 1998) research on African American male communication as “muted groups communication,” and notions of third-culture building (Casmir, 1993; Shuter, 1993). The recognition of the role of power is commensurate with a notion of destabilizing and conflictual characteristics of culture. Culture is seen not as stable and orderly, but as a site of struggle for various meanings by competing groups (Ono, 1998).

Scholars have also pointed out the possible consequences of power differentials between researchers and researched: How researchers’ position and privilege constrain their interpretations of research finding (Crawford, 1996; González & Krizek, 1994; Moon, 1996; Rosaldo, 1989) and how voices of research participants (many times less privileged) are often not heard in the studies about them (Tanno & Jandt, 1994).

Third, there is a recognition that intercultural communication research should be more relevant to everyday lives, that theorizing and research should be firmly based in experience, and in turn, should not only be relevant to, but should facilitate, the success of everyday intercultural encounters (see Ribeau, 1997).

These issues have led to a growing body of research based on Burrell and Morgan’s (1988) remaining two paradigms, radical humanist and radical structuralist, both of which stress the importance of change and conflict in society.3. This research reflects the increasing influence of European critical theory, e.g., Bourdieu (1991), Derrida (1976), Foucault (1980), Habermas (1970, 1981), and British cultural studies, e.g., S. Hall (1977, 1985) and Hebdige (1979). These “critical” scholars have influenced communication scholarship, primarily in media studies (see Grossberg, Nelson, & Treichler, 1992; Lull, 1995) and organizational communication (e.g., Deetz, 1996; Mumby, 1988, 1997; Wert-Gary et al., 1991), but critical ideas have been less integrated into mainstream intercultural communication scholarship (some exceptions are Lee, Chung, Wang, & Hertel, 1995; Moon, 1996). So these two paradigms are less clearly defined.4. The research goal of both paradigms is to understand the role of power and contextual constraints on communication in order ultimately to achieve a more equitable society. Research in both paradigms emphasize the conflictual and unstable aspects of culture and society.

Critical Humanist Paradigm

As noted in Figure 12.2, critical humanist research has much in common with the interpretive viewpoint, as both assume that reality is socially constructed and emphasize the voluntaristic characteristic of human behavior (Burrell & Morgan, 1988). However, critical humanist researchers conceive this voluntarism and human consciousness as dominated by ideological superstructures and material conditions that drive a wedge between them and a more liberated consciousness. Within this paradigm, the point of academic research into cultural differences is based upon a belief in the possibility of changing uneven, differential ways of constructing and understanding other cultures. Culture, then, is not just a variable, not benignly socially constructed, but a site of struggle where various communication meanings are contested (Fiske, 1987, 1989, 1993, 1994).

Founded largely upon the work by Althusser (1971), Gramsci, (1971, 1978), and the Frankfurt school (Habermas, 1970, 1981, 1987; Horkheimer & Adorno, 1988; Marcuse, 1964), critical humanist scholars attempt to work toward articulating ways in which humans can transcend and reconfigure the larger social frameworks that construct cultural identities in intercultural settings. From this paradigmatic perspective, there is a rapidly developing body of literature investigating communication issues in the construction of cultural identity. Unlike interpretive identity research (e.g., Carbaugh, 1990a; Collier & Thomas, 1988), critical research assumes no “real” identity, but only the ways that individuals negotiate relations with the larger discursive frameworks (e.g., Altman & Nakayama, 1991). An example of this research is Nakayama’s (1997) description of the competing and contradictory discourses that construct identity of Japanese Americans. Hegde’s work (1998a, 1998b) on Asian Indian ethnicity and Lee’s (1999) on Chinese also explore the contradictory and competing ways in which identity is constructed.

This scholarship often draws directly from cultural studies scholars like Stuart Hall (1985), who tells us that he is sometimes called “Black,” “colored,” “West Indian,” “immigrant,” or “Negro” in differing international contexts. There is no “real” Stuart Hall in these various ways of speaking to him, but only the ways that others place and construct who he is. His identity and his being are never to be conflated.

Other examples of research in this paradigm are critical rhetorical studies, e.g., Nakayama and Krizek’s (1995) study of the rhetoric of Whiteness, and Morris’s (1997) account of being caught between two contradictory and competing discourses (Native American and White). Finally, there is also a growing body of popular culture studies that explore how media and other messages are presented and interpreted (and resisted) in often conflicting ways. See, for example, Flores’s (1994) analyses of Chicano/a images as represented by the media or Peck’s (1994) analysis of various discourses represented in discussions of race relations on Oprah Winfrey. Additionally, very recent postcolonial approaches to culture and communication represent a critical humanist perspective (see Collier, 1998b). It should be noted that studies in this tradition have focused primarily on cultural meanings in textual or media messages, rather than on face-to-face intercultural interactions.

Critical Structuralist Paradigm

Critical structuralist research also advocates change—but from an objectivist and more deterministic standpoint:

Whereas the radical humanists forge their perspective by focusing upon “consciousness” as the basis for a radical critique of society, the radical structuralists concentrate upon structural relationships within a realist social world. (Burrell & Morgan, 1998, p. 34)

Largely based upon the structuralist emphasis of Western Marxists (Gramsci, 1971, 1978; Lukács, 1971; Volosinov, 1973), this approach emphasizes the significance of the structures and material conditions that guide and constrain the possibilities of cultural contact, intercultural communication, and cultural exchange. Within this paradigm, the possibilities for changing intercultural relations rest largely upon the structural relations imposed by the dominant structure (Mosco, 1996). As noted in Figure 12.2, culture is conceptualized as societal structures. So, for example, interactions between privileged foreign students and U.S.-American students cannot be seen as random, but rather are a reflection of structural (cultural) systems of privilege and economic power. These larger structural constraints are often overlooked in more traditional intercultural communication research. When power and structural variables are incorporated into functionalist research (e.g., communication accommodation theory, diffusion of innovation), they are conceptualized as somewhat static, and the goal is not to change the structures that reproduce the power relations.

The focus, like that of critical humanism, is usually on popular culture texts rather than interpersonal interactions. For this reason, this scholarship has traditionally been defined as mass communication and not intercultural communication per se (see Asante & Gudykunst’s, 1989, distinction between international and intercultural communication). These scholars largely examine economic aspects of industries that produce cultural products (e.g., advertising, media) and how some industries are able to dominate the cultural sphere with their products (Fejes, 1986; Meehan, 1993). An example is Frederick’s (1986) study on the political and ideological justifications leading to the establishment and maintenance of Radio Marti, the U.S. radio presence in Cuba. Another example is Nakayama and Vachon’s (1991) study of the British film industry between World War I and World War II. They compare the quality of films produced in Britain and in the United States during this time. Based on a paradigmatic assumption that economic structures constrain the kinds of texts (e.g., films) that are possible, they argue that British films were inferior during this time, due to explicit economic strategies (e.g., Lend-Lease Act) to undermine the British film industry.

We should note that postmodern approaches (Mumby, 1997) to communication studies may represent the future of culture and communication research, but at this point, it is too early to articulate the relationship between the framework outlined here and a postmodern position.

Beyond the Paradigms

Understanding these four paradigmatic perspectives allows us to locate the source of many scholarly debates, helps to legitimize and also identify strengths and limitations of contemporary approaches, and presents the possibility of interparadigmatic dialogue and collaboration. The source of debates can be clearly seen in the dramatic difference s among these four perspectives (see Figure 12.2). How can identifying or acknowledging the existence of these traditions lead to more productive research? There are probably a variety of responses or directions one may advocate with respect to interparadigmatic research. We have identifies four positions that we think can challenge our way of thinking about culture and communication research: liberal pluralism, interparadigmatic borrowing, multiparadigmatic collaboration, and a dialectic perspective.

Liberal pluralism is probably the most common and the easiest, a live-and-let-live response. This position acknowledges the values of each paradigmatic perspective, that each contributes in some unique way to our understanding of culture and communication. One could point out that research in the functionalist paradigm has provided us with some useful snapshot images of cultural variations in communication behavior, that interpretive research has provides many insights into communication rules of various speech communities and contexts. However, one would also have to acknowledge that because cultures are largely seen as static and cultural behavior as benign in those two paradigms, the structural dynamics that support any culture are often overlooked. Critical researchers fill this gap by focusing on important structural and contextual dynamics, but provide less insight on intercultural communication on an interpersonal level.

Although the value of each paradigmatic tradition is acknowledged in this position, there is litter attempt to connect the ideas from one paradigm to another, or to explore how ideas from one paradigm may enrich the understanding of research from other paradigms. This is analogous to African Americans and Whites acknowledging and respecting both Kwanzaa and Christmas traditions, but never actually talking to each other about the cultural significance of these holidays.

There is a strong belief underlying this position that the best kind of research is firmly grounded in solid paradigmatic foundations. As many have noted, paradigmatic beliefs are strong and deeply felt, a sort of faith about the way that world is and should be, and it take extensive study and experience to become proficient in research in one paradigm (Burrell & Morgan, 1988; Deetz, 1996).

A second position is that of inteparadigmatic borrowing. This position is also strongly committed to paradigmatic research, but recognizes potential complementary contributions from other paradigms. Researchers taking this position listen carefully to what others say, read research from other paradigms and integrate some concerns or issues into their own research. This is seen in currently functionalist and interpretive research that has been influenced by critical thinking, for example, Katriel’s (1995) essay on the importance of integrating understanding of macro-contexts (historical, economic, political) in cultural communication studies, or Collier’s recent essay incorporating notions of history and power differentials in ongoing studies of interethnic relationships (1998a) and cultural identity (1998b). This borrowing is analogous to a traveler abroad learning new cultural ways (e.g., learning new expressions) that they incorporate into their lives back home. However, the researcher, while borrowing, is still fundamentally committed to research within a particular paradigm.

A third position is multiparadigmatic collaboration. This approach is not to be undertaken lightly. It is based on the assumption that any one research paradigm is limiting, that all researchers are limited by their own experience and worldview (Deetz, 1996; Hammersly, 1992), and the different approaches each have something to contribute. Unlike the other positions, it does not privilege any one paradigm and attempts to make explicit the contributions of each in researching the same general research question. Though this sounds good, it is fraught with pitfalls. Deetz (1996) warns against “teflon-coated multiperspectivalism” that leads to shallow readings (p. 204). Others have warned against unproductive synthetic (integrative) and additive (pluralistic, supplementary) approaches (Deetz, 1996; B. J. Hall, 1992).

Although it would be nice to move across paradigms with ease, most researchers are not “multilingual.” However, one could argue that culture and communication scholars are particularly well positioned for interparadigmatic dialogue and multiparadigmatic collaboration; that they, of all researchers, should have the conceptual agility to think beyond traditional paradigmatic (cultural) boundaries. In a way this approach reminds us of our interdisciplinary foundations, when anthropologists like E. T. Hall used linguistics frameworks to analyze nonverbal interaction—a daring and innovative move (Leeds-Hurwitz, 1990).

Because it is unlikely that any one researcher can negotiate various paradigms simultaneously and conduct multiperspectival research, one strategy is collaborative research in multicultural terms (Deetz, 1996; Gudykunst & Nishida, 1989). An example of this is a current investigation of Whiteness where scholars from different research traditions (a critical position, an ethnographic perspective, and a social scientific tradition) and representing ethnic and gender diversity are investigating one general research question, “What does being White mean communicatively in the United States today?” (Nakayama & Krizek, 1995; Martin, Krizek, Nakayama, & Bradford, 1996).

In this collaborative project we are conducting a series of studies using multiple questions, methods, and perspectives, but, more importantly, different paradigmatic assumptions. However, each study meets the paradigmatic criteria for one research orientation, representing what Deetz (1996) described as an ideal research program—where complementary relations among research orientations are identified, different questions at different moments are posed, but at each moment answering to specific criteria of an orientation. This multiparadigmatic orientation permits a kind of rotation among incompatible orientations and has led to new insights about the meaning of Whiteness in the U.S. today.

A fourth position is a dialectic perspective. Like multiparadigmatic research, this position moves beyond paradigmatic thinking, but is even more challenging in that it seeks to find a way to live with the inherent contradictions and seemingly mutual exclusivity of these various approaches. That is, a dialectic approach to accepted that human nature is probably both creative and deterministic; that research goals can be to predict, describe, and change; that the relationship between culture and communication is, most likely, both reciprocal and contested. Specifically, is there a way to address the contextual and power concerns of the critical humanists-structuralists in everyday interpersonal interactions between people from different cultural backgrounds? We propose a dialectic approach that moves us beyond paradigmatic constraints and permits more dynamic thinking about intercultural interaction and research.

Toward a Dialectical Perspective5.

The notion of dialect is hardly new. Used thousands of years ago by the ancient Greeks and others, its more recent emphases continue to stress the relational, processual, and contradictory nature of knowledge production (Bakhtin, 1981; Baxter, 1990; Cornforth, 1968). Aristotle’s famous dictum that “rhetoric is the counterpart of dialectic” emphasizes the significant relationship between modes of expression and modes of knowledge. Dialectic offers intercultural communication researchers a way to think about different ways of knowing in a more comprehensive manner, while retaining the significance of considering how we express this knowledge.

Thus, a dialectical approach to culture and communication offers us the possibility of engaging multiple, but distinct, research paradigms. It offers us the possibility to see the world is multiple ways and to become better prepared to engage in intercultural interaction. This means, of course, that we cannot become enmeshed into any paradigm, to do so flies in the face of dialectic thinking.

We are not advocating any single form of dialectic. The adversarial model utilized in forensic rhetoric may be appropriate in some instances, whereas a more inward, therapeutic model discussed by psychoanalysts may be needed in other situations. Different dialectical forms lead to differing kinds of knowledge. No single dialectical form can satisfy epistemological needs within the complexity of multiple cultures. To reach for a singular dialectical form runs counter to the very notion of dialectical “because dialectical thinking depends so closely on the habitual everyday mode of thought which it is called on to transcend, it can take a number of different and apparently contradictory forms” (Jameson, 1971, p. 308).

Yet, a dialectical approach offers us the possibility of “knowing” about intercultural interaction as a dynamic and changing process. We can begin to see epistemological concerns as an open-ended process, as a process that resists fixed, discrete bits of knowledge, that encompasses the dynamic nature of cultural processes. We draw from the work of critical theorists who initially envisioned their theory as a “theory of contemporary socio-historical reality in which itself was constantly developing and changing” (Kellner, 1989, p. 11). For critical theorists, as well as ourselves, there are many social realities that coexist among the many cultures of the world. Thus, “dialectics for critical theory describe how phenomena are constituted and the interconnections between different phenomena and spheres of social reality” (Best & Kellner, 1991, p. 224).

A dialectical perspective also emphasizes the relational, rather than individual aspects and persons. In intercultural communication research, the dialectical perspective emphasizes the relationship between aspects of intercultural communication, and the importance of viewing these holistically and not in isolation. In intercultural communication practice, the dialectical perspective stresses the importance of relationship. This means that one becomes fully human only in relation to another person and that there is something unique in a relationship that goes beyond the sum of two individuals. This notion is expressed by Yoshikawa (1987) as the “dynamic inbetweenness” of a relationship—what exists beyond the two persons. Research on the notion of their-culture building is one attempt to develop a relational dialectic approach to intercultural interactions (Belay, 1993; Casmir, 1993; Shuter, 1993, Starosta, 1991).

Finally, the most challenging aspect of the dialectical perspective is that it requires holding two contradictory ideals simultaneously, contrary to most formal education in the United States. Most of our assumptions about learning and knowledge assume dichotomy and mutual exclusivity. Dichotomies (e.g., good–evil, subjective–objective) form the core of our philosophical, scientific, and religious traditions.

In contrast, a dialectical perspective recognizes a need to transcend these dichotomies. This notion, well known in Eastern countries as based on the logic of “soku” (“not-one, not-two”), emphasizes that the world is neither monistic nor dualistic (N. Nakayama, 1973, pp. 24–29). Rather, it recognizes and accepts as ordinary, the interdependent and complementary aspects of the seeming opposites (Yoshikawa, 1987, p. 187). In the following sections, we apply the dialectical perspective to intercultural communication theory and research.

A Dialectical Approach to Studying Intercultural Interaction

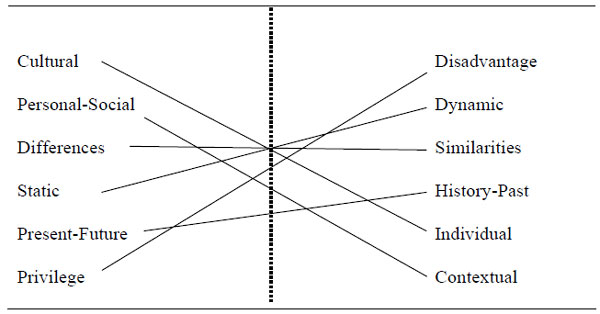

Interpersonal communication scholars have applied a dialectical approach to relational research (Baxter, 1988, 1990; Baxter & Montgomery, 1996; Montgomery, 1992) and identified basic contradictions or dialectics in relational development (autonomy–connection, novelty–predictability, openness–closedness). Although we do not advocate a simple extension of this interpersonal communication research program, we have identified six similar dialectics that seem to operate interdependently in intercultural interactions: cultural–individual, personal/social–contextual, differences–similarities, static–dynamic, present-future/history-past, and privilege–disadvantage dialectics. These dialectics are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive but represent an ongoing exploration of new ways to think about face-to-face intercultural interaction and research.

Cultural–Individual Dialectic

Scholars and practitioners alike recognize that intercultural communication is both cultural and individual. In any interaction, there are some aspects of communication that are individual and idiosyncratic (e.g., unique nonverbal expressions or language use) as well as aspects that are shared by others in the same cultural groups (e.g., family, gender, ethnicity, etc.). Functionalist research has focused on communication patterns that are shared by particular groups (gender, ethnicity, etc.) and has identified differences between these group patterns. In contrast, critical communication scholars have resisted connecting group membership with any one individual’s particular behavior, which leads to essentializing.

A dialectical perspective reminds us that people are both group members and individuals and intercultural interaction is characterized by both. Research could investigate how these two contradictory characteristics work in intercultural interactions. For example, how do people experience the tension between wanting to be seen and treated as individuals, and at the same time have their group identities recognized and affirmed (Collier, 1991)? This tension is often at the heart of the affirmative action debate in the United States—a need to recognize cultural membership and at the same time be treated as an individual and not put in boxes.

Personal/Social–Contextual Dialectic

A dialectical perspective emphasizes the relationship between personal and contextual communication. There are some aspects of communication that remain relatively constant over many contexts. There are also aspects that are contextual. That is, people communicate in particular ways in particular contexts (e.g., professors and students in classrooms), and messages are interpreted in particular ways. Outside the classroom (e.g., at football games or at faculty meetings), professors and students may communicate differently, expressing different aspects of themselves. Intercultural encounters are characterized by both personal and contextual communication. Researchers could investigate how these contradictory characteristics operate in intercultural interactions.

Differences–Similarities Dialectic

A dialectic approach recognizes the importance of similarities and differences in understanding intercultural communication. The field was founded on the assumption that there are real, important differences that exist between various cultural groups, and functionalist research has established a long tradition of identifying these differences. However, in real life there are a great many similarities in human experience and ways of communicating. Cultural communication researchers in the interpretive tradition have emphasized these similar patterns in specific cultural communities. Critical researchers have emphasized that there may be differences, but these differences are often not benign, but are political and have implications for power relations (Houston, 1992).

There has been a tendency to overemphasize group differences in traditional intercultural communication research—in a way that sets up false dichotomies and rigid expectations. However, a dialectical perspective reminds us that difference and similarity can coexist in intercultural communication interactions. For example, Israelis and Palestinians share a love for their Holy City, Jerusalem. This similarity may be overweighed by the historical differences in meanings of Jerusalem so that the differences work in opposition. Research could examine how differences and similarities work in cooperation or in opposition in intercultural interaction.

For example, how do individuals experience the tension of multiple differences and similarities in their everyday intercultural interactions (class, race, gender, attitudes, beliefs)? Are these aspects or topics that tend to emphasize one or the other? How do individuals deal with this tension? What role does context play in managing this tension?

Static–Dynamic Dialectic

The static–dynamic dialectic highlights the ever-changing nature of culture and cultural practices, but also underscores our tendency to think about these things as constant. Traditional intercultural research in the functionalist tradition and some interpretive research have emphasized the stability of cultural patterns, for example, values, that remain relatively consistent over periods of time (Hofstede, 1991). Some interpretive research examines varying practices that reflect this value over time (e.g., Carbaugh’s study of communication rules on Donahue discourse, 1990a). In contrast, critical researchers have emphasized the instability and fleetingness of cultural meanings, for example, Cornyetz’s (1994) study of the appropriation of hip-hop in Japan.

So thinking about culture and cultural practices as both static and dynamic helps us navigate through a diverse world and develop new ways of understanding intercultural encounters. Research could investigate how these contradictory forces work in intercultural interactions. How do individuals work with the static and dynamic aspects of intercultural interactions? How is the tension of this dynamic experienced and expressed in intercultural relationships?

Present-Future/History-Past Dialectic

A dialectic in intercultural communication exists between the history-past and the present-future. Much of the functionalist and interpretive scholarship investigating culture and communication has ignored historical forces. Other scholars added history as a variable in understanding contemporary intercultural interaction, for example, Stephan and Stephan’s (1996) prior intergroup interaction variable that influences degree of intergroup anxiety. In contrast, critical scholars stress the importance of including history in current analyses of cultural meanings.

A dialectical perspective suggests that we need to balance both an understanding of the past and the present. Also the past is always seen through the lens of the present. For example, Oliver Stone’s film, Nixon, was criticized because of the interpretation Stone made of (now) historical events and persons. As Stone pointed out, we are always telling our versions of history.

Collier’s (1998a) investigations of alliance in ethnic relationships reveal the tensions of the present and past in ethnic relationships. This and other research reveal the importance of balancing an understanding the history, for example, of slavery and the African diaspora, the colonization of indigenous peoples (Morris, 1997), the internment of Japanese Americans (Nakayama, 1997), relationships between Mexico and the U.S., as well as maintaining a focus on the present in interethnic relationships in the United States. How do individuals experience this tension? How do they balance the two in everyday interaction? Many influential factors precede and succeed any intercultural interaction that gives meaning to that interaction.

Privilege–Disadvantage Dialectic

As individuals, we carry and communicate various types of privilege and disadvantage, the final dialectic. The traditional intercultural communication research mostly ignores issues of privilege and disadvantage (exceptions include Pennington, 1989; Gallois et al., 1995), although these issues are central in critical scholarship. Privilege and disadvantage may be in the form of political, social position, or status. For example, if members of wealthy nations travel to less wealthy countries, the intercultural interactions between these two groups will certainly be influenced by their differential in economic power (Katriel, 1995). Hierarchies and power differentials are not always clear. Individuals may be simultaneous privileged and disadvantaged, or privileged in some contexts, and disadvantaged in others. Research could investigate how the intersections of privilege and disadvantage work in intercultural encounters. Women of color may be simultaneously advantaged (education, economic class) and disadvantaged (gender, race), for example (Houston, 1992). How are these various contradictory privileges and disadvantages felt, expressed, and managed in intercultural interactions? How do context and topic play into the dialectic? Many times, it may not be clear who or how one is privileged or disadvantaged. It may be unstable, fleeting, may depend on the topic, or the context.

Dialectical Intersections

So how do these different dialectics work in everyday interaction? These dialectics are not discrete, but always operate in relation to each other (see Figure 12.3). We can illustrate these intersections with an example of a relationship between a foreign student from a wealthy family and a U.S.-American professor. Using this example we can see how contradictories in several dialectics can occur in interpersonal intercultural interaction. In relation to the personal/social–contextual dialectic, both the student and professor are simultaneously privileged and disadvantaged depending on the context. In talking about class material, for example, the professor is more privileged than the student, but in talking about vacations and travel, the wealthy student may be more privileged.

Figure 12.3 Intersections of Six Dialectics of Intercultural Interaction.

To focus on another set of dialects, if the topic of international trade barriers comes up, the student may be seen as a cultural representative than an individual and, in this conversation, cultural differences or similarities may be emphasized. When the topic shifts, these relational dialectics also shift—within the same relationship.

These important dialectical relational shifts have not been studies in previous research, and this is what makes the dialectical perspective different from the other three positions identified earlier (liberal pluralism, interparadigmatic borrowing, and multiparadigmatic research). That is, this approach makes explicit the dialectical tension between what previous research topics have been studied (cultural differences, assumed static nature of culture, etc.) and what should be studied (how cultures change, how they are similar, importance of history). The dialectical perspective, then, represents a major epistemological move in our understanding of culture and communication.

Conclusion

In this brief essay we have tried to challenge culture and communication scholars to consider ways that their production of knowledge is related to the epistemological advances made by those in other paradigms. Whereas there cannot be any easy fit among these paradigmatic differences, it is important that we not only recognize these differences, but also seek ways that these epistemological differences can be productive rather than debilitating. Information overload can be daunting, but our dialectical perspective offers intercultural scholars, as well as students and practitioners, a way to grapple with the many different kinds of knowledge we have about cultures and interactions.

In his own thinking about dialectical criticism, Fredric Jameson (1971) observes that “there is a breathlessness about this shift from the normal object-oriented activity of the mind to such dialectical self-consciousness—something of the sickening shudder we feel in a elevator’s fall or in the sudden dig up in an airliner” (p. 308).

This sudden fall in the ways we think about intercultural communication means letting go of the more rigid kinds of knowledge that we have about others and entering into more uncertain ways of knowing about others.

Notes

1.Cross-cultural communication denotes studies identifying cultural differences in communication phenomena, both interpersonal and mediated, e.g., Fitch’s (1994) study of directives in Boulder, Colorado, and Bogata, Colombia. Intercultural communication has focused on the interaction of individuals from various cultural backgrounds in interpersonal contexts, e.g., Houston’s (1997) study of Black-White women’s interaction, as well as mediated, for example, Pennington’s (1989) media study of Jesse Jackson’s negotiations with Syria for release of an American POW. Intracultural/cultural communication studies identify communication patterns within particular cultural communities, for example, Philipsen’s (1976) studies of White, working class male talk in a Chicago neighborhood.

2.These are not necessarily new issues. Scholars had emphasized the need to examine power differentials in intercultural encounters, e.g., Asante, 1987; Folb, 1982; Kramarae, 1981; Smith (aka Asante), 1973, but they were largely ignored (see Moon, 1996); Ribeau, 1997). Concerning relevance, A. G. Smith (1981), in an indictment of intercultural communication research, stated that the appropriate focus of scholars should be on “relevant” topics—on eliminating poverty, oppression, and not on understanding sojourner communication and other “frivolous” topics.

3.We use the terms critical humanist and critical structuralist to emphasize the critical theory foundations of these paradigms.

4.One could argue that critical voices have been present in critical ethnography (Conquergood, 1991) and critical rhetoric (McKerrow, 1989), which often address the intersection of culture and communication. This, of course, brings up the question of the boundaries of the study of culture and communication, which is beyond the scope of this essay. What is the appropriate focus for the study of culture and communication? Will cultural studies, critical ethnography, etc., be incorporated along with intercultural communication research to form a larger area of study? Or will intercultural communication researchers simply borrow some of their ideas and retain more narrow boundaries?

5.Some of the material concerning the six dialectics appear in J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama, & L. A. Flores (1998). A dialectical approach to intercultural communication. In J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama, & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 5–14). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

References

Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and philosophy (B. Brewster, Trans.). New York: Monthly Review Press.

Altman, K. E., & Nakayama, T. K. (1991). Making a critical difference: A difficult dialogue. Journal of Communication, 41(4), 116–128.

Asante, M. K. (1987). The Afrocentric idea. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Asante, M. K., & Gudykunst, W. B. (1989). Preface. In M. K. Asante & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 7–16). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M. M. Bakhtin. (M. Holquist, Ed., and C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Barnlund, D. C. (1975). Public and private self in Japan and United States: Communicative styles of two cultures. Tokyo: Simul Press.

Barnlund, D. C. (1989). Communicative styles of Japanese and Americans: Images and realities. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Baxter, L. A. (1988). A dialectical perspective on communication strategies in relationship development. In S. W. Duck (Ed.), A handbook of personal relationships (pp. 257–273). New York: Wiley.

Baxter, L. A. (1990). Dialectical contradictions in relationship development. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 69–88.

Baxter, L. A., & Montgomery, B. M. (1996). Relating: Dialogues and dialectics. New York: Guilford Press.

Belay, G. (1993). Toward a paradigm shift for intercultural and international communication: New research directions. Communication Yearbook, 16, 437–457.

Best, S., & Kellner, D. (1991). Postmodern theory: Critical interrogations. New York: Guilford Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Braithwaite, C. A. (1990). Communicative silence: A cross cultural study of Basso’s hypothesis. In D. Carbaugh, (Ed.), Cultural communication and intercultural contact (pp. 321–328). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brislin, R. W. (1993). Understanding culture’s influence on behavior. New York: Harcourt Brace.

Burgoon, J. K. (1995). Cross-cultural and intercultural applications of expectance violations theory. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 194–214). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Burrell, G., & Morgan, G. (1988). Sociological paradigms and organizational analysis. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Carbaugh, D. (1988a). Comments on “culture” in communication inquiry. Communication Reports, 1, 38–41.

Carbaugh, D. (1988b). Talking American. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Carbaugh, D. (1990a). Communication rules in Donahue discourse. In D. Carbaugh (Ed.), Cultural communication and intercultural contact (pp. 119–149). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Carbaugh, D. (Ed.). (1990b). Cultural communication and intercultural contact. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Casmir, F. L. (1993). Third-culture building: A paradigm shift for international and intercultural communication. Communication Yearbook, 16, 407–428.

Collier, M. J. (1991). Conflict competence within African, Mexican and Anglo American friendships. In S. Ting-Toomey & F. Korzenny (Eds.), Cross-cultural interpersonal communication (pp. 132–154). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Collier, M. J. (1996). Communication competence problematics in ethic friendships. Communication Monographs, 63, 314–337.

Collier, M. J. (1998a). Intercultural friendships as interpersonal alliances. In J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama, & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 370–379). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Collier, M. J. (1998b). Researching cultural identity: Reconciling interpretive and postcolonial perspectives. In D. V. Tanno & A. González (Eds.), Communication and identity across cultures (pp. 122–147). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Collier, M. J., & Thomas, M. (1988). Cultural identity in intercultural communication: An interpretive perspective. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (p. 94–120). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Conquergood, D. (1991). Rethinking ethnography: Towards a critical cultural politics. Communication Monographs, 58, 179–195.

Cornyetz, N. (1994). Fetishized Blackness: Hip hop and racial desire in contemporary Japan. Social Text, 41, 113–140.

Cornforth, M. (1968). Materialism and the dialectical method. New York: International Publishers.

Crawford, L. (1996). Personal ethnography. Communication Monographs, 63, 158–170.

Cronen, V. E., Chen, V., & Pearce, W. B. (1988). Coordinated management of meaning: A critical theory. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 66–98). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Deetz, S. (1994). The future of the discipline: The challenges, the research, and the social contribution. Communication Yearbook, 17, 565–600.

Deetz, S. (1996). Describing differences in approaches to organization sciences: Rethinking Burrell and Morgan and their legacy. Organization Science, 7, 119–207.

Derrida, J. (1976). Of grammatology (G. Spivak, Trans.). Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Dilthey, W. (1976). Selected writing (H. P. Rickman, Ed. & Trans,). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fejes, F. (1986). Imperialism, media and the good neighbor: New Deal foreign police and United States shortwave broadcasting to Latin America. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Fiske, J. (1987). Television culture. New York: Methuen.

Fiske, J. (1989). Understanding popular culture. Boston, MA: Unwin Hyman.

Fiske, J. (1993). Power plays, power works. New York: Verso.

Fiske, J. (1994). Media matters: Everyday culture and political change. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Fitch. K. L. (1994). A cross-cultural study of directive sequences and some implications for compliance-gaining research. Communication Monographs, 61, 185–209.

Flores, L. A. (1994). Shifting visions: Intersections of rhetorical and Chicana feminist theory in the analysis of mass media. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia, Athens, GA.

Folb, E. (1982). Who’s got the room at the top? Issues of dominance and nondominance in intracultural communication. In L. A. Samovar & R. E. Porter (Ed.), Intercultural communication: A reader (3rd ed., pp. 132–141). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977 (C. Gordon, L. Marshall, J. Mepham, & K. Soper, Trans.). New York: Pantheon Books.

Frederick, H. (1986). Cuban-American radio wars: Ideology in international telecommunications. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Gadamer, H. G. (1976). Philosophical hermeneutics (D. E. Linge, Ed. & Trans.). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Gadamer, H. G. (1989). Truth and method. New York: Crossroad Publishing.

Gallois, C., Franklyn-Stokes, A., Giles, H., & Coupland, N. (1988). Communication accommodation in intercultural encounters. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 157–185). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Gallois, G., Giles, H., Jones, E., Cargile, A. C., & Ota, H. (1995). Accommodating intercultural encounters: Elaborations and extensions. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 115–147). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Garner, T. (1994). Oral rhetorical practice in African American culture. In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (pp. 81–91). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Giles, H., Coupland, N., & Coupland, J. (Eds.). (1991). Contexts of accommodation: Developments in applied sociolinguistics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

González, A., Houston, M., & Chen, V. (Eds.). (1997). Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

González, C., & Krizek, R. (1994, February). Indigenous ethnography. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Western Communication Association, San Jose, CA.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks.(Q. Hoare & G. N. Smith, Trans.). New York: International.

Gramsci, A. (1978). Selections from cultural writings. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Grossberg, L., Nelson, C., & Treichler, P. (Eds.). (1992). Cultural studies. New York: Routledge, Chapman, & Hall.

Gudykunst, W. B. (1995). Anxiety/uncertainty management (AUM) theory: Current status. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8–58). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gudykunst, W. B., & Nishida, T. (1989). Theoretical perspectives for studying intercultural communication, In M. K. Asante & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 17–46). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Habermas, J. (1970). On systematically distorted communication. Inquiry, 13, 205–218.

Habermas, J. (1981). Modernity versus postmodernity. New German Critique, 22, 3–14.

Habermas, J. (1987). The theory of communicative action: Lifeworld and system. (Vol.2. T. McCarthy, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Hall, B. J. (1992). Theories of culture and communication. Communication Theory, 2, 50–70.

Hall, S. (1977). Culture, media, and the “ideological effect.” In J. Curran, M. Gurevitch, & J. Woollacott (Eds.), Mass communication and society (pp. 315–348). London: Edward Arnold.

Hall, S. (1985). Signification, representation, ideology: Althusser and the post-structuralist debates. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 2, 91–114.

Hamlet, J. D. (1997). Understanding traditional African American preaching. In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed., pp. 94–98). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Hammersly, M. (1992). What’s wrong with ethnography? New York: Routledge, Chapman, & Hall.

Harman, R. C., & Briggs, N. E. (1991). SIETAR survey: Perceived contributions of the social sciences to intercultural communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 15(1), 19–28.

Headland, T., Pike, K., & Harris, M. (Eds.). (1990). Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture: The meaning of style. London: Methuen.

Hecht, M. L., Larkey, L., & Johnson, J. (1992). African American and European American perceptions of problematic issues in interethnic communication effectiveness. Human Communication Research, 19, 209–236.

Hecht, M. L., Collier, M. J., & Ribeau, S. A. (1993). African American communication: Ethnic identity and cultural interpretation. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Hegde, R. (1998a). Translated enactments: The relational configurations of the Asian Indian immigrant experience. In J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama, & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 315–322). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

Hegde, R. (1998b). Swinging the trapeze: The negotiation of identity among Asian Indian immigrant women in the United States. In D. V. Tanno & A. González (Eds.), Communication and identity across cultures (pp. 34–55). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. (1988). Dialectic of enlightenment (J. Cumming, Trans.). New York: Continuum.

Houston, M. (1992). The politics of difference: Race, class, and women’s communication. In L. F. Rakow (Ed.). Women making meaning (pp. 45–59). New York: Routledge, Chapman, & Hall.

Houston, M. (1997). When Black women talk with White women: Why dialogues are difficult. In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed., pp. 187–194). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Hymes, D. (1972). Models of the interaction of language and social life. In J. J. Gumperz & D. Hymes (Eds.), Directions in sociolinguistics: The ethnography of communication (pp. 35–71). New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Jameson, F. (1971). Marxism and form. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Katriel, T. (1986). Talking straight: “Dugri” speech in Israeli Sabra culture. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Katriel, T. (1995). From “context” to “contexts” in intercultural communication research. In R. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 271–284). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kellner, D. (1989). Critical theory, Marxism and modernity. Baltimore, MA: Johns Hopkins, University Press.

Kim, H. J. (1991). Influence of language and similarity on initial interaction attraction. In S. Ting-Toomey & F. Korzenny (Eds.), Cross-cultural interpersonal communication (pp. 213–229). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kim, M.-S.(1994). Cross-cultural comparisons of the perceived importance of interactive constraints. Human Communication Research, 21, 128–151.

Kim, M.-S., & Wilson, S. R. (1994). A cross-cultural comparison of implicit theories of requesting. Communication Monographs, 61, 210–235.

Kim, M.-S., Hunter, J. E., Miyahara, A., Horvath, A.-M., Bresnahan, M., & Yoon, H.-J. (1996). Individual vs. culture level dimensions of individualism/collectivism: Effects on preferred conversational styles. Communication Monographs, 63, 28–49.

Kim, U., Triandis, H. C., Kăğitçibaşi, I., Choi, S.-C., & Yoon, G. (Eds.). (1994). Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kim, Y. Y. (1984). Searching for creative integration. In W. B. Gudykunst & Y. Y. Kim (Eds.), Methods for intercultural communication research (pp. 15–28). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kim, Y. Y. (1988). On theories in intercultural communication. In Y. Y. Kim & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Theories in intercultural communication (pp. 11–21). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kim, Y. Y. (1995). Cross-cultural adaptation: An integrative theory. In R. L. Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 170–194). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kramarae, C. (1981). Women and men speaking: Frameworks for analysis. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lee, W. S. (1999). One Whiteness veils three uglinesses: From border-crossing to a womanist interrogation of colorism. In T. K. Nakayama & J. N. Martin (Eds.), Whiteness: The communication of social identity (pp. 279–298). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lee, W. S., Chung, J., Wang, J., & Hertel, E. (1995). A sociohistorical approach to intercultural communication. Howard Journal of Communications, 6, 262–291.

Leeds-Hurwitz, W. (1990). Notes on the history of intercultural communication: The Foreign Service Institute and the mandate for intercultural training. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 76, 262–281.

Lukács, G. (1971). History and class consciousness: Studies in Marxist dialectics. (R. Livingston, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lull, J. (1995). Media, communication, culture: A global approach. New York: Columbia University Press.

Marcuse, H. (1964). One dimensional man. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Martin, J. N., Krizek, R. L., Nakayama, T. K., & Bradford, L. (1996). Exploring Whiteness: A study of self-labels for White Americans. Communication Quarterly, 44, 125–144.

Martin, J. N., Hammer, M. R., & Bradford, L. (1994). The influence of cultural and situational contexts on Hispanic and non-Hispanic communication competence behaviors. Communication Quarterly, 42, 160–179.

Martin, J. N., Nakayama, T. K., & Flores, L. A. (1998). A dialectical approach to intercultural communication. In J. N. Martin, T. K. Nakayama, & L. A. Flores (Eds.), Readings in cultural contexts (pp. 5–14). Mountain View, CA: Mayfield.

McKerrow, R. (1989). Critical rhetoric: Theory and praxis. Communication Monographs, 56, 91–111.

McPhail, T. L. (1989). Inquiry in international communication. In M. K. Asante & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 47–60). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Mead, G. H. (1934). Mind, self, and society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Meehan, E. R. (1993). Rethinking political economy: Changes and continuity. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 105–116.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception (C. Smith, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Moon, D. G. (1996). Concepts of culture: Implications for intercultural communication research. Communication Quarterly, 44, 70–84.

Montgomery, B. M. (1992). Communication as the interface between couples and culture. Communication Yearbook, 15, 475–507.

Morris, R. (1997). Living in/between. In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed., pp. 163–176). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Mosco, V. (1996). The political economy of communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mumby, D. K. (1988). Communication and power in organizations: Discourse, ideology, and domination. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Mumby, D. K. (1997). Modernism, postmodernism, and communication studies: A rereading of an ongoing debate. Communication Theory, 7, 1–28.

Nakayama, N. (1973). Mujuntek isousoku no ronri. Kyoto, Japan: Hyakkaen.

Nakayama, T. K. (1997). Dis/orienting identities: Asian Americans, history, and intercultural communication. In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed., p. 14–20). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Nakayama, T. K., & Krizek, R. L. (1995). Whiteness: A straight rhetoric. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 81, 291–309.

Nakayama, T. K., & Vachon, L. A. (1991). Imperialist victory in peacetimes: State functions and the British cinema industry. Current Research in Films, 5, 161–174.

Ono, K. (1998). Problematizing “nation” in intercultural communication research. In D. Tanno & A. González (Eds.), Communication and identity across cultures (pp. 34–55). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Orbe, M. P. (1994). “Remember, it’s always Whites’ ball”: Descriptions of African American male communication. Communication Quarterly, 42, 287–300.

Orbe, M. P. (1998). Constructing co-cultural theory: An explication of culture, power, and communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Peck, J. (1994). Talk about racism: Framing a popular discourse of race on Oprah Winfrey. Cultural Critique, 5, 89–126.

Pennington, D. L. (1989). Interpersonal power and influence in intercultural communication. In M. K. Asante & W. B. Gudykunst (Eds.), Handbook of international and intercultural communication (pp. 261–274). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Philipsen, G. (1976). Speaking “like a man” in Teamsterville: Culture patterns of role enactment in an urban neighborhood. Quarterly Journal of Speech, 61, 13–22.

Ribeau, S. A. (1997). How I came to know “in self realization there is truth.” In A. González, M. Houston, & V. Chen (Eds.), Our voices: Essays in culture, ethnicity, and communication (2nd ed., pp. 21–27). Los Angeles, CA: Roxbury.

Rogers, E. (1995). Diffusion of innovations (4th ed.). New York: Free Press.

Rosaldo, R. (1989). Culture and truth: The remaking of social analysis. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Schleiermacher, F. D. E. (1977). Hermeneutics: The handwritten manuscripts (J. Duke & J. Forstman, Trans). Missoula, MT: Scholar Press for the American Academy of Religion.

Shuter, R. (1990). The centrality of culture. Southern Communication Journal, 55, 237–249.

Shuter, R. (1993). On third-culture building. Communication Yearbook, 16, 429–436.

Smith, A. L. (aka M. K. Asante). (1973). Transracial communication. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Smith, A. G. (1981). Content decisions in intercultural communication. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 47, 252–262.

Starosta, W. J. (1991, May). Third culture building: Chronological development and the role of third parties. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association, Chicago, IL.

Stephan, W. G., Stephan, C. W. (1996). Intergroup relations. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Tanno, D. V., & Jandt, F. E. (1994). Redefining the “other” in multicultural research. Howard Journal of Communications, 5, 36–54.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1984). Qualitative research: An overview. In W. B. Gudykunst & Y. Y. Kim (Eds.), Methods for inter-cultural communication research (pp. 169–184). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1986). Conflict communication styles in Black and White subjective cultures. In Y. Y. Kim (Ed.), Inter-ethic communication: Current research (pp. 75–88). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S. (Ed.). (1994). The challenge of facework: Cross-cultural and interpersonal issues. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Ting-Toomey, S., & Chung, L. (1996). Cross-cultural interpersonal communication: Theoretical trends and research directions. In W. B. Gudykunst, S. Ting-Toomey, & T. Nishida (Eds.), Communication in personal relationships across cultures (pp. 237–262). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ting-Toomey, S., Gao, G., Trubisky, P., Yang, Z., Kim, H. S., Lin, S. L., & Nishida, T. (1991). Culture, face maintenance and styles of handling interpersonal conflicts: A study in five cultures. International Journal of Conflict Management, 2, 275–296.

Volosinov, V. N. (1973). Marxism and the philosophy of language (L. Matejka & I. R. Titunik, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wert-Gary, S., Center, C., Brashers, D. E., & Meyers, R. A. (1991). Research topics and methodological orientations in organizational communication: A decade in review. Communication Studies, 42, 141–154.

Wiseman, R. L. (Ed.). (1995). Intercultural communication theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yoshikawa, M. J. (1987). The double-swing model of intercultural communication between the East and the West. In D. L. Kincaid (Ed.), Communication theory: Eastern and Western perspectives (pp. 319–329). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.