The Masculine–Feminine Construct in Cross-Cultural Research

The Emergence of a Transcendent Global Culture

In this chapter, James W. Chesebro, David T. McMahan, Preston Russett, Eric J. Schumacher, and Junliang Wu explore the increased visibility of alternative modes of sexuality across cultures and reassess and reconceptualize the widely accepted masculinity–femininity construct in cross-cultural communication research. They open their essay with a discussion on the burgeoning representations in popular culture that transgress the traditional dichotomy of sexuality and gender. Substantiated by their extensive review of literature, Chesebro and his colleagues disclose the prevalent and potent role of mediated communication in shaping, defining, or even regulating gender and mode of sexuality. They suggest that social movements in conjunction with advancement in communication technology have gradually transformed the binary categorization of gender and sexuality and deliberate the need to modify the conventionally assumed masculinity–femininity construct. Through a cross-cultural comparison of gender-ambivalent media personas in the United States and China, Chesebro and his associates propose to employ the concept of androgyny for understanding gender and sexuality as it recognizes the co-existence of masculine and feminine traits in each individual and views the application of sex roles as active choices and expressions according to situational appropriateness.

Unmistakably, our relationships with and towards gender and sexuality affect us every day. Issues of gender and sexuality flood our national and international media. These issues can be ironic and controversial. For example, television networks in the United States selectively censor expressions of sexuality, footage of pop star Adam Lambert kissing his male keyboardist, while broadcasting other expressions of sexuality, footage of pop stars Britney Spears and Madonna kissing (Itzkoff, 2009). These issues can be landmark moments. In late 2009, an openly gay politician was celebrated in Texas for making history after securing a public position within the American government (McKinley, 2009).

In cross-cultural or intercultural communication studies, not every one of these popular culture events possesses the same power and significance. Events must be readily perceived as representative anecdotes of the enduring values, roles, shared knowledge system, and convention patterns of interaction of a culture if they are to be potentially understood and treated as cross-cultural communication elements. Indeed, some have even maintained that a value must be transmitted from one generation to another if it is to “qualify” as an important variable in cross-cultural communication research (Aldridge, 2004, p. 87).

Accordingly, we anticipate that a diversity of sexual issues can and do emerge from a plethora of topics and situations. In a short span of several months, for example, we can see popular newspapers report imbalanced representations of women in the arts, insufficient benefits for gay couples, escalating instabilities in contemporary American marriages, widespread rape in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Africa, and a continued oppression and suppression of women in Burundi and around the globe (see, e.g., Delmeiren, 2009; Gettleman, 2009; Hymowitz, 2009; Kristof & WuDunn, 2009; Teachout, 2009). Within and across these issues of gender, power, and sexuality—if they are to be treated as a cultural issue—we would expect, at a minimum, that these inequalities persist over time. Indeed, this focus on the enduring is frequently appropriate when dealing with cross-cultural communication. At the same time, change can exert an influence on how we think of nation-state cultures interacting and communicating with each other. Indeed, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, Ting-Toomey (1999) urged researchers to pay particular attention to how various changes might influence the study of cross-cultural communication:

As we enter the 21st century, there is a growing sense of urgency that we need to increase our understandings of people from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds. … With rapid changes in global economy, technology, transportation, and immigration policies, the world is becoming a small, intersecting community. … In order to achieve effective intercultural communication, we have to learn to manage differences flexibly and mindfully. (p. 3)

As we shall argue in this essay, we are particularly convinced that our diverse communication technology systems are gradually, but decisively, fostering adjustments and transformations in how we consider gender and sexuality—the specifically the masculine–feminine construct—in cross-cultural communication research. A case study aptly illustrates our major claim in a concise and vivid fashion.

Transcending Dichotomies, Melting Divides: A Case Study as a Point of Departure

In The Fatherhood Institute’s The Fatherhood Report 2010–2011, an emerging and ongoing interest in the blending and dissolution of divides between traditionally conceived gender roles is intentionally highlighted and emphasized (The Fatherhood Institute, 2010). Across the globe, the male has typically been relegated to breadwinner. Historically, for example, cultures have deemed males predominantly responsible for obtaining financial security while females are cast predominantly, if not consistently, only as caregivers. However, in the analysis offered by The Fatherhood Institute (2010), the divide between mother and father as caregiver and breadwinner may have negative social effects, especially on children. For instance, The Fatherhood Institute’s research findings suggest that a multitude of positive outcomes for children, ranging from few behavioral problems to higher self-esteem, when fathers diverge from purely masculine roles and provide “sensitive and competent care beyond the role of breadwinner” (The Fatherhood Institute, 2010).

In direct or indirect response, as expressed across The Fatherhood Report 2010–2011, contemporary parents across the globe are aspiring to share care-giving responsibilities both in the home and the workplace. From Sweden to Denmark to Greece and beyond, cultures can be seen integrating parental leave for both men and women while others press governments for more even representation for women in political and economic offices. Within this context, The Fatherhood Institute maintains that a host of world cultures are increasingly seeking and promoting balance and diversity in gender roles. At the same time, other research institutions have reported the existence of various inequalities in job opportunities for women despite an ongoing interest in equal rights (Pew Research Center, 2010, p. 14).

The interest in equal partnerships in family and work relations for both genders reflects a broader shift in our relationships towards traditionally opposed gender constructs of femininity and masculinity. In various pockets across the globe, alternative expressions of sexuality and gender are increasing in visibility (and accessibility). In popular culture, we have online sensations like Lady Gaga and Justin Bieber, consciously or unconsciously, embracing and projecting both masculine and feminine traits. On American television, Fox’s Glee (Murphy, Falchuk, Loreto, & Brennan, 009), disguised as a weekly high school musical, brazenly promotes and navigates a wide spectrum of alternative modes of sexuality. In China, the “tomboy” pop singer and winner of Super Girl winner Li Yuchun also challenges traditional ideals and customs. At times, like international icon David Bowie before them, these performers champion androgyny and its versatile appeal.

The media often react and respond to these shows and artists, incestuously extending the exploration of sexuality and gender in popular discourse. Some view this mounting exposure of alternative modes of sexuality in the media as productive while others label it dangerous. When long-established constructs are opposed with alternatives, agitated traditionalists often react passionately. For instance, on Fox News in America, the infamous political commentator Bill O’Reilly (2012) recently condemned Glee (2009) for the program’s “recurring theme that alternative lifestyles may be a big positive.”

So, while we fully admit that transformations in gender and sexual roles are extremely controversial, we are also convinced that profound cultural transformations are at stake. In many ways, these gender and sexual role transformations can be traced back to the sexual freedom of the 1960s that underwent variations through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. In the twenty-first century, with the advent of global and digital communication technologies, human interactions have become more immediate, involving, and personal. In our view, the transformations we are now witnessing are worth exploring, for we believe that what we are viewing now is a gradual but decisive reduction in the explanatory power of the masculine–feminine dichotomy as a mechanism for describing, interpreting and evaluating gender and sexual roles within various cultures.

Preview

The impact of these recurring themes requires further research, but we believe these ongoing popular expressions of alternative modes of sexuality, no matter how selective, are significant to global communications research now and into the future. In this chapter, we examine these issues by way of a four part analysis.

First, we explore the increased visibility in alternative modes of sexuality across cultures with an emphasis on reassessing our conceptions of the masculinity–femininity construct so pervasive in cross-cultural communication research. Within this context, we examine changes in sexuality and gender as represented and stimulated by the media and popular culture.

Second, we examine how one cross-cultural researcher operationally defined the masculinity–femininity construct and how it functioned as a research model which has been conceptually employed by cross-cultural communication analysts. We initially examine Hofstede’s (2001) database and the analysis of his data for establishing the masculinity–femininity dichotomy in the first place and then we examine Ting-Toomey’s (1999) treatment of this construct an outstanding example of how the masculinity–feminist construct has been employed conceptually in explaining cross-cultural communication. In this context, we provide a critical analysis of the masculine–feminine construct and render an overall value of this construct.

Third, we examine the emergence global television–Internet franchises as technologies with a global reach as well as a standardizing, promoting, and therefore transforming cultural systems. And, we specifically argue that these franchises are a powerful force in terms of the masculine– feminine construct.

Fourth and finally, we transition to a discussion of androgyny as a construct of unique and immediate interest for cross-cultural communications research and understanding. We firmly believe that the notion of androgyny functions as a far more useful and explanatory term for accounting for how gender identities are changing on a global level.

With this preview in mind, we turn first to the description of the newer forms of gender and sexual roles that have been emerging on the various new global communication technologies particularly since the twenty-first century.

Mediated Communication, Gender Roles, and Sexuality

Media are a ubiquitous part of many people’s lives. Indeed, communication is now predominantly transmitted through media systems which influence perceptions and understandings of messages, knowledge, and realities. Accordingly, “these systems are ultimately the mechanism that can mediate and regulate the symbols that shape, define, and even regulate” gender and modes of sexuality (Borisoff & Chesebro, 2011, p. 67). In the following section, we examine the pervasiveness of media in our lives. We also explore how gender and sexuality have been symbolically conveyed through such media systems as film, music, and the Internet.

The Pervasiveness of Media

Media are a pervasive presence and constitute a primary component of our everyday environment. From a global perspective, consumption of such media as print, radio, film, and television varies considerably among cultures and nation states (see McMahan & Chesebro, 2003). Within the United States, much of a person’s day is spent using media. By way of example, a report from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010) shows that the average total media use among 8–18-year-olds is 7 hours and 38 minutes each day. When concurrent media use—using more than one media system at the same time—is measured, total daily media exposure rises to 10 hours and 45 minutes.

While cultural and nation-state differences remain, the extensive use of digital media and the Internet is steadily becoming a global phenomenon. At the end of 2011, the number of Internet users throughout the world had reached over 2.25 billion people, an increase of over 528 percent since the year 2000 (Internet World Stats, 2011). The prevalence and increased consumption of digital media are especially evident when cell phone usage to gain access to such media is examined (Kohut et al., 2011). For instance, Magni and Atsmon (2010) reported that by the end of 2009, the number of Internet users in China had reached 384 million people, 233 million of whom accessed the Internet on handheld devices.

Beyond their significance as a pervasive part of life, it is important to recognize the influence of media as mediating communication systems that cultivate specific images and understandings of gender and sexuality. In what follows, we will examine the ways in which gender and modes of sexuality are represented and understood through three media systems.

Masculine and Feminine Images in Film

The most successful films of recent decades have been dominated by men portraying traditionally masculine characters. These characters are presented as protectors and survivors, with muscular physiques, broad shoulders, and extreme physiological energy. Masculine prestige and social status are achieved through physical dominance, individual perseverance, and control of others.

Exemplifying these images are two archetypical-masculine characters portrayed by Sylvester Stallone, Rocky and Rambo. Through six movies appearing over a thirty-year period (1976–2006), Rocky rises from obscurity to become boxing’s heavyweight champion. In doing so, physical strength, self-determination, individuality, and personal achievement are emphasized and dominate the conception of masculinity. The character of Rambo appeared in a total of four films over a twenty-six-year period. Rambo is a courageous soldier who refuses to attack until an enemy draws first blood, at which point fury and unyielding violence become justified. In these and more recent action films starring such actors as Vin Diesel, Dwayne Johnson, and Jason Statham, masculinity is depicted as encompassing power, physical strength, control, and determination.

While traditionally masculine images of men in film have been pervasive, exceptions have and continue to emerge. Noting numerous performances by Tom Hanks, Borisoff and Chesebro (2011) note that through his characters “the masculine male can and does serve others and the community, reveals the limitations of the male as an active and controlling agent, and suggests that there is humor and enjoyment in simply living with others” (p. 75). Exceptions to traditional masculinity in film also pertain to body image. A number of successful male actors such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Johnny Depp are small in stature and lack muscular definition, possessing such traditionally feminine facial characteristics as fuller lips, narrow jaws, defined cheekbones, and smooth skin. Also emerging in film are portrayals of male characters who not only counter the muscular physique of action heroes but also portray warmth, kindness, and nurturing behaviors traditionally associated with femininity. Examples of such characters include those portrayed by Jack Black and Zach Galifianakis. These characters tend to be short, overweight, and scraggily in appearance, possess child-like traits, and are essentially asexual.

While depictions of men in film have tended to be extremely masculine, depictions of women have tended to be extremely feminine. Women characters tend to play supportive roles, generally used to bolster the masculine depiction of men. They tend to be portrayed physically weaker and dependent on men for security and guidance. While there have been films depicting women as action heroes, these characters still are often placed in a diminished role in favor of a male character and are often placed in situations in which they must depend on a male character for survival.

Masculine and Feminine Representations Through Music

Whereas film has tended to reinforce traditional notions of gender and sexuality, music has provided a forum through which gender and sexual norms have been challenged and through which profound shifts in the comprehension and categorization of gender and sexuality have occurred. For instance, in past decades, male performers created personas based on sexual promiscuity, control, and authority. More recently, male performers are representative of the ever-changing nature of masculinity and sexuality, becoming decidedly more vulnerable, nurturing, and wholesome. Justin Bieber and The Jonas Brothers are examples of musicians typifying this shift in masculinity.

Emerging into the music industry through YouTube, Justin Bieber has been referred to as “the first real teen idol of the digital age, a star whose fame can be attributed entirely to the Internet” (Suddath, 2010, p. 49). Eschewing strength, domination, and physical control, Bieber’s image is created through his small build and stature, smiles rather than sneers, moppish hair, and consistently wide eyes. Furthermore, the lyrics of his songs embrace sincerity, dependence, and commitment rather than control and dominance.

The Jonas Brothers’ image and music also diverge from traditional notions of masculinity. Through a series of submissive and pleading songs such as “Please Be Mine,” males are reflected as having a desperate need for meaningful relationships and true love. Additionally, “the Jonas Brothers’ publicly articulated commitment to sexual abstinence until after marriage has conveyed an image of a kind of wholesomeness, if not innocence, that stands in direct contrast to the more traditional commitment to lustfulness that characterizes a traditional conception of masculinity” (Borisoff & Chesebro, 2011, p. 75).

More so than masculinity, femininity has been consistently dynamic and exploratory in the music industry. For instance, since her debut album in 1983, Madonna has presented myriad representations of femininity and frequently provided an array of masculine and androgynous images and behavior. Undergoing continuous change, she has drawn attention to change itself as part of the human condition and to the dynamic and transformative nature of gender and sexuality. Taylor Swift and Lady Gaga provide two more recent examples of the expanding nature of femininity, with each offering distinct views of femininity and how it can be conveyed.

The youngest winner of the Grammy for album of the year and solo female country singer, Taylor Swift conveys the traditional conception of femininity as innocent, chaste, and pure. At the same time, as a performer and lyricist, her model of femininity is paradoxical and more complicated than it may initially appear. She has been aggressive in her outreach to fans, connecting with them interpersonally through online interactions. Moreover, her lyrics reflect and legitimize the experiences of women her age, serving as a mobilizing force and spirit. While conveying innocence associated with traditional femininity, her determined pursuit of success through digital means along with the sense of unity created through her lyrics serve to promote a powerful social and political identity for both her and her fans.

Meanwhile, known for theatrical behavior, outlandish wardrobe, and socially conscious music and outreach, Lady Gaga was named one of the 100 most influential and powerful people in the world by both Time magazine and Forbes magazine just two years following the release of her debut album. Embracing and using the digital realm in the creation of her persona has enabled her to cross genres and cultures with ease and to undergo constant and unrelenting personal change. Through these transformations, she continuously transcends and challenges notions of gender and sexuality. She occasionally appears as her male alter-ego, Jo Calderone, who even has his own Twitter account. She often wears the trapping of a traditionally feminine woman, but the extreme designs of her outfits, makeup, and jewelry suggests defiance and aggression toward traditional norms. Finally, her music videos have included lesbian and partially nude scenes, perhaps a knowing wink to audiences regarding early questions pertaining her biological sex and perhaps informing them that it ultimately does not matter.

Masculinity and Femininity on Social Networking Sites

Briefly following the emergence of the Internet, Chesebro (2000) enthusiastically proclaimed “the Internet is the single most pervasive, involving, and global communication system ever created by human beings, with a host of untapped and unknown political, economic, and sociocultural implications” (p. 8). This prescient statement continues to hold true, with Internet penetration expanding throughout the world and its influence touching nearly every aspect of life. Among its influences, the Internet is rapidly becoming the primary means through which relating takes place. Consequently, it has a profound impact on the ways in which gender and sexuality are portrayed, experienced, developed, and understood.

Social networking sites epitomize the relational aspect of the Internet and readily demonstrate the construction of gender and sexuality online. Social networking sites are becoming a global phenomenon, with billions of registered users worldwide. A survey conducted by The Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project found that at least 25 percent of adults within fifteen of the twenty-one countries included in the study used social networking sites. Within two of these countries, Israel and the United States, half of all adults used social networking sites (Kohut et al., 2011).

Globally, the use of social networking sites according to biological sex is not known. Within the United States, however, a slight statistical difference exists among adult Internet users, with 69 percent of women using social networking sites, compared to 60 percent of men (Madden & Zickuhr, 2011). Teenage Internet users display no statistical difference when it comes to biological sex overall, with 83 percent of girls using social networking sites, compared to 78 percent of boys. However, when age is used in conjunction with biological sex, a statistical difference emerges, with 92 percent of teenage girls between the ages of 14 and 17 compared to 85 percent of teenage boys between the ages of 14 and17 (Lenhart et al., 2011). With no statistical difference discovered among younger children and only slight differences among other groups, it is likely there will soon be no difference when it comes to biological sex and the use of social networking sites.

A comparatively new phenomenon, it is difficult for definitive and comprehensive claims to be made about the ways in which gender and sexuality are displayed, developed, and understood though social networking sites. However, some three initial observations can be made at this point.

First, many of these sites restrict divergence and transformation of gender and sexuality through the use of hegemonic labels. When completing one’s profile, the categories provided for romantic relationships tend to be limited to those describing heterosexual relationships. When it comes to gender, users must often choose between either male or female. One social networking site, Google+, allows users to select male, female, or other. However, being described as “other” devalues those whose gender orientation is neither male nor female. Naturally, though, completing a personal profile is only one component of social networking sites, and users of any technology overcome inherent limitations when adapting it to their own uses and needs.

Second, regardless of potential inherent limitations, these sites are places where issues of gender and sexuality emerge. For example, Geidner, Flook, and Bell (2007) found that the number of friends a person listed on a social networking site can be perceived as a measure through which masculinity is conveyed. As with other media systems, body image is extremely important in the construction of masculine and feminine identities. Both men and women place great significance on the selection of profile photographs, with women generally viewing them with more importance than men (Pempek, Yermolayeva, & Calvert, 2009; Siibak, 2009; Whitty, 2009).

Third and finally, gender appears to be a factor when determining the prosocial value of comments posted by friends on a user’s page. Women are perceived as more attractive when these comments are positive and less attractive when these comments are negative. However, when negative comments involving such socially undesirable behavior as drinking in excess and promiscuity are posted on the wall of men, perceptions of attractiveness actually increase (Walther, Van Der Heide, Kim, Westerman & Tong, 2008). This finding is most likely the result of males performing activities traditionally associated with masculine behavior.

These traditional notions of masculinity and femininity stem from what we have identifying as the masculine–feminine construct, especially within a cross-cultural context. It is now especially important to identify the uses and origins of this construct.

The Masculine–Feminine Construct in Cross-Cultural Communication Research

Many researchers (Ting-Toomey, 1999; Hofstede, 2001) have explored and studied national cultures based on key variables constructed from poles of cultural value dimensions. Hofstede (2001) explored “the differences in thinking and social action” in over fifty nations using five dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism vs. collectivism, masculinity vs. femininity, and long-term orientation vs. short-term orientation. He described masculinity and femininity as one of the most important polar sets of cultural values, distinguishing cultures and communication systems by affecting human thinking, feeling, and acting. He believed masculinity–femininity as a cultural dimension is empirically verifiable, and each country could be positioned somewhere between their poles (Hofstede, pp. xix–xx). Hofstede defined masculinity and femininity as follows:

Masculinity stands for a society in which social gender roles are clearly distinct: Men are supposed to be assertive, tough, and focused on material success; women are supposed to be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. Femininity stands for a society in which social gender roles overlap: Both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life. (2001, p. 297)

A masculine culture values achievement outside the home, encouraging both males and females to be tough, aggressive, and competitive. Hofstede’s Masculinity Index (MAS) ranks Japan as the most masculine country, with a score of 95/100 (2001, p. 286). It is the only Asian country to break the top ten. A feminine culture like Sweden (with a masculinity score of 5/100), on the other hand, may value modesty, negotiation, compromise, nurturing, and harmony. The Nordic countries are all on the feminine end of the spectrum, unlike many western European countries like Germany.

Hofstede (2001) asserted that the level of masculinity in a country is also a measure of gender differentiation within that country. He found the values of men and women working the same job in high-MAS countries tended to be more different than in low-MAS countries (p. 285–286). He also found that men and women in Nordic countries actually switch gender roles, with women scoring higher on the masculinity index. Furthermore, gender differences are most pronounced in younger people, with both men and women becoming less ego-oriented and more social-oriented over time (p. 289–291).

The aggressive and ego-centered nature of masculine countries should not be confused with Hofstede’s (2001) variable of individualism, which is defined an individual’s relationship with the collective group, not the tender/tough duality. For example, the United States ranks fifteenth in masculinity with a score of 62/100, but ranks first in individualism, whereas, Japan may be the most masculine country, but it ranks twenty-second in individualism.

Gender differences are social, but obviously biological differences in sex exist as well. Men are, on average, taller, and stronger than women, while women generally have greater finger dexterity and faster metabolisms (Hofstede, 2001, p. 280). These absolute and statistical biological differences allow women and men to serve different gender roles in society. Men are supposed to be assertive, competitive, and tough; whereas women are supposed to be more concerned with taking care of the home, children, and people in general (Hofstede, 2001, p. 280). Table 21.1 presents the summary of value connotations of masculinity and femininity found in Hofstede’s (2001) surveys.

Table 21.1 Summary of Value Connotations of MAS Differences Found in Surveys and Other Comparative Studies

Low MAS |

High MAS |

Cooperation at work and relationships with boss important. |

Challenge and recognition in jobs important. |

Living area and employment security important. |

Advancement and earnings important. |

Values of women and men hardly different. |

Values of women and men very different. |

Lower job stress. |

Higher job stress. |

Belief in group decisions. |

Belief in individual decisions. |

Preference for smaller companies. |

Preference for large corporations. |

Private life protected from employer. |

Employer may invade employees’ private lives. |

Belief in Theory Y (employees enjoy the physical and mental challenges of work). |

Belief in Theory X (management assumes employees dislike and avoid work). |

Promotion by merit. |

Promotion by protection. |

Work not central in a person’s life space. |

Work very central in a person’s life space. |

Relational self: empathy with others regardless of their group. |

Self is ego: not my brother’s keeper. |

Among elites and consumers, stress on cooperation. |

Among elites and consumers, stress on advancement. |

Schwartz’s values surveys among teachers and students: low mastery. |

Schwartz’s surveys: high mastery: ambitious, daring, independent. |

Inglehart’s world value survey analysis: well-being values. |

Inglehart’s WVS analysis: survival values. |

Higher well-being in rich countries. |

Higher well-being in poor countries. |

Achievement in terms of quality of contacts and environment. |

Achievement in terms of ego boosting, wealth, and recognition. |

Gordon’s male students: more benevolence. |

Gordon’s male students: greater need for recognition. |

IRGOM manager’s life goals: service. |

IRGOM manager’s life goals: leadership and self-realization. |

Higher norms for emotional stability and ego control. |

Lower norms for emotional stability and ego control. |

In practical terms, these distinctions are intended to describe the gender and social roles of men and women do in everyday life. In this conception, gender roles take an important place in the family raised in a masculine culture, emphasizing a strong gender differentiation between males and females. For example, boys may prevail in performance games and girls in relationship games. In contrast, a feminine culture stresses a weak gender differentiation in the socialization of children. Students in a masculine culture would pay more attention to the student’s academic performance in school, while social adaptation is important for students in a feminine culture.

Reflecting how Hofstede’s conception and research findings have been employed, Ting-Toomey (1999) described Hofstede’s cultural dimensions as “a first systematic empirical attempt to compare cultures on an aggregate, group level” in business groups (p. 66). She argued that one should be aware of flexible gender roles while communication in a feminine culture and focus on achievements while in a masculine culture. While using Hofstede’s cultural dimensions, Ting-Toomey (1999) focused on the individualism–collectivism value, which she said informs “self-conception.” She used Hofstede extensively, but spent little time on the masculinity–femininity value.

While Hofstede can give us considerable insight into how different cultures communicate, his data is limited. Hofstede administered questionnaires to IBM employees in over fifty countries between 1967 and 1973 to collect his data on cultural values (2001, p. 40). As we have suggested, tremendous and dramatic social transformations in gender and sexual roles have occurred since the first call for a “sexual revolution” at the end of the 1960s. Additionally, IBM’s comparatively well-trained employees are not necessarily representative of an entire population. Moreover, using countries as distinct units does not take distinct ethnic and racial groups within countries into account. Hofstede argued that his data has strongly correlated with other studies and, while about forty years old, stands the test of time because cultural communication is developed from centuries of tradition (2001, p. 73). Finally, Hofstede’s dimensions are constructs, and they are not inherent to culture. Additional values may exist should a scholar wish to search for them.

Some scholars may insist the communication system is often dominated, if not controlled, by diverse cultural systems. The dichotomy of masculinity and femininity is one of the core values of communication systems, largely determining behaviors, feelings, and values. Indeed, masculinity and femininity can function persuasively because they are reinforced by the unique norms, rules, traditions, symbols, and heroes of each culture. In cross-cultural communication, accordingly, such dichotomy or “opposition pairs” might be useful for solely characterizing national cultures.

While employing the cultural dichotomy to differentiate nations appeared to be appropriate, the values of masculinity and femininity appear to change over time. In the U.S., where masculinity often dominates the cultural system, the concepts of masculinity and femininity have been altered, reflecting the changes of social positions. Men start to pay more attention to social relations while women become more independent and competitive. The New York Times underscored the change, noting that “what men want” has changed in seven decades. Today, men desire mutual attraction with women and have less need for dependable character. More people know feminism as “the movement that brought women more work.” In the United States, women have been making strides in education and the workforce for decades.

A 2011 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center found women are more likely than men to enroll in and complete college (Wang & Parker, 2011). Specifically, in 2010, 36 percent of women aged 25–29 had completed a bachelor’s degree, compared to 28 percent of men in the same age group. Plus, half of all women who graduated from a four-year school rated the U.S. higher education system as being “good” or “excellent” compared to 37 percent of men. Women were also more likely to call their education “useful.” More women in higher education means more women in the workforce, working similar hours as men, earning more money and more highly valuing their careers.

According to data released by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, men and women who were married and childless in 2010 had almost exactly the same working hours when combining paid and unpaid work: 8 hours and 11 minutes for men and 8 hours and 3 minutes for women (Konigsberg, 2011). Married men still do less domestic work than women, but their contribution at home has tripled in the past forty years. For example, married men with children now spend on average 6.4 hours caring for their children, compared to 2.6 hours in 1965 and 3 hours in 1985. Married women with children spend about 12 hours/week caring for children.

A 2012 Pew Research Center report found 66 percent of women aged 18–34 consider career a high priority, compared with 59 percent of young men (Patten & Parker, 2012). The study also found that women make up nearly half the labor force but still earn less than men. The earning gap is considerably better for women aged 18–34, who earn more than 90 percent as much as men. Women aged 35–64 still only earn 80% percent as much as men of the same age.

Mundy (2012) argued that women will soon become the primary breadwinners in American families. She cites the growing trends of women in education and the workplace, especially growths in women-dominated fields like healthcare (p. 6). Conversely, male dominated fields like construction and manufacturing are dwindling.

Hence, such growing trends of competitive and tough women in a masculine culture may well indicate a changing dichotomy. Sometimes such dichotomy has been merged and presented in one country. China, for example, is a masculine culture, scoring 66/100 in Hofstede’s (2001) masculinity index. Competition, achievement, and recognitions are significant in the Chinese culture. In the Chinese education system, the college entrance exam creates a fierce competition for students. Nearly 10 million students will be battling for an estimated 6.6 million university places (Liang, 2010). Both parents and students take the entrance exam seriously because it largely determines the future career path of young adults. Chinese students often push themselves to prepare for the exam, sacrificing luxury time to get into a respected college.

While China primarily maintains a competitive strategy in dealing with education and economic development, harmony has always been a central value of Chinese society, repeatedly influencing the Chinese people. Kirkbride, Tang, and Westwood (1991) argued, “we suggest that conformity, collectivism, harmony and shame combine to create a social pressure and expectation which influence Chinese people to be less openly assertive and emotional in conflict situations” (p. 371). Chesebro, Kim, and Lee (2007) further pointed out that China used a consensus or compromise strategy in the short run and collaboration in the long term in dealing with the North Korea nuclear testing problem. Whereas, the United States, as a masculine country, used competition in the short term and confrontation in the long term while dealing with North Korea’s nuclear testing.

Each country develops its own culture, supporting unique communication systems. It may be true that cultural differences between countries are enormous, especially between the West and the East. China and the United States, two countries normally thought to be at odds. Indeed, the differences between China and the United States are tremendous. Geographically, China and U.S. are literally on the opposite sides of the world. Politically, China is a socialist country, while capitalism is considered as the central value to the United States.

However, no country or culture can survive without interaction and communication. Accordingly, intercultural communication has become a significant research domain. Specially, with the development of digital technology and the Internet, the nature of sexuality is being globalized, absorbing values from other cultures. Thus, it is inappropriate to solely label a country on either masculinity or femininity and the emerging value-androgyny should receive more attention. Such changes have been reflected from some global programming, such as the global television franchises.

A Global Transformation of Gender and Sexual Roles

Gender and sexuality roles are not easily transformed, especially on a global scale. However, the emergence of global systems such as the Internet and its related social networking sites, such as Facebook, suggests that a far more broadly based and rapid socialization system may now exist. We think a key to such massive transformation systems resides in the development of international franchise systems.

Global Television–Internet Franchises

During the last decade, reality-competition television shows have been replicated across the globe for nations as program adaptations, clones, and imitations. The “Idol” and the “Got Talent” franchises have spawned shows in over forty territories worldwide (Fremantle Media). Such television formats might have successfully extended beyond geographic boundaries and crossed multiple cultures. Sen (2012) explained that mass media, which together constitute an ecumenical vehicle of culture with an insatiable appetite for profit, would generate forms (formats) of art that travel with ease and translate into every context. Therefore, emerging global programming and media technology have definitely impacted the dichotomy of masculinity and femininity. In most of these competition shows, contestants have equal rights to participate, compete, and be the “best of the field,” regardless of social classes and gender differences. Moreover, one of the Idol adaptions, Super Girl, was originally produced only for women. Super Girl encouraged them to be confident and independent. While globalization has changed masculinity and femininity, the power of androgyny has risen simultaneously. Ding (2007) once said “Li Yuchun, the winner of Super Girl’s 2005 season, and her “tomboy-style” became symbols of Super Girl. Although some Chinese authorities believed that her “attitude, originality, and androgyny” were challenging the country’s traditional customs’ (Chinaview. cn), Time Asia Magazine reported, “the influence brought by the ‘Li Yuchun phenomenon’ goes far beyond her voice in China.”

Global Values of These Franchises in Terms of Sexuality

Global values seem to blur the concept of sexuality with the rise of globalization, which develop and perhaps redefine masculinity and femininity. Wu (2012) initialized eleven common values from two worldwide talent shows, America’s Got Talent and China’s Got Talent, arguing that digital technologies appear to transcend some traditional cultural distinctions. Table 21.2 provides an overview and definition of these eleven values.

Table 21.2 The Foundation for a Global Culture: Eleven Commonly Shared American and Chinese Cultural Values

Categories |

Values |

Definitions |

References |

Power Distance |

Equality |

A guarantee to each individual of precisely the same share of an essential resource, such as food. |

Burrell, J. (2010). Evaluating shared access: Social equality and the circulation of mobile phones in rural Uganda. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15, 230–250. |

Individualism and Collectivism |

Individualism |

A social pattern that consist of loosely link individuals who view themselves as independent of collectives. |

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO; Westview. |

Collectivism |

A social pattern consisting of closely linked individuals who view themselves as parts of one or more collectives (family, co-workers, tribe, nation. |

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and Collectivism. Boulder, CO; Westview. |

|

Masculinity and Femininity |

Achievement |

Reach the summit, win the race. |

Vendler, Z. (1957). Verbs and times, Philosophical Review, 66, 143–160. |

Competition |

The effort of two or more parties acting independently to secure the business of a third party by offering the most favorable terms. |

Webster’s, p. 268. |

|

Uncertainty Avoidance |

Creativity |

Uniqueness and imagination. |

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. |

Transparency |

Openness, letting people see the process creation of those products. |

Allen, D. S. (2008). The trouble with transparency: The challenge of doing journalism ethics in a surveillance society. Journalism Studies, 9, (3). |

|

Long-Term and Short-Term Orientation |

Pleasure/Enjoyment |

A judgment for which the underlying dimension represents degrees of preference. |

Parducci, A. (1995). Happiness, pleasure, and judgment: The contextual theory and its applications. Florence, KY: Psychology Press. |

Spirituality |

Fantasy |

Something imaginary, not grounded in reality. |

Bormann, E.G. (1985). The force of fantasy: Restoring the American dream. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. |

Morality/Ethnic |

To coexist with others, show respect for them as part of one’s life, and give an anthropological dimension to one of the supreme categories of understanding-relation. |

Pasquali, A. (1997) The moral dimension of communicating, communication ethnics and universal values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. |

|

Universality |

Globalization |

The widening, deepening and speeding up of worldwide interconnectedness, in all aspects of contemporary social life, from the cultural to the criminal, the financial to the spiritual. |

Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D., & Perraton, J. (1999). Global transformations: politics, economics, and culture. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. |

Commonalities between the two rarely similar countries, China and America, may indeed constitute the foundation for a set of truly global values. The eleven values such as equality and pleasure are all presented in the shows simultaneously, along with achievement and competition, the two core values of masculinity and femininity. These values might have been intermingled and well integrated by the programming. Hence, masculinity and femininity do not work out individually, instead, they work dependently with other values as a unit. In all, new concepts of masculinity, femininity, and androgyny are facing a challenge, led by the technology and globalization.

Beyond the subtle blending, if not merger, of masculine and feminine traits portrayed in these media system, it is also important to note that these global franchises function as profound and pervasive persuasive models and systems. The participatory and amazing degree of involvement in these musical competitions is aptly measured by the number of contestants who apply to appear on the programs. For many, contestants rehearse and plan for these appearances in a host of diverse prior performance settings, often for years. And, for viewers, there is a quest to find a favorite hero/heroine from the diverse contestants. Indeed, these talent competitions are among the most popular television shows in virtually all of the countries in which they occur. Indeed, referring to these “global television formats,” Brennan (2012) notes that, because these formats employ “entertainment” rather on information or education modes, they are appropriate understood—for both participants and viewers—as “formatted pleasure” programs.

All of these findings suggest to us that it is at least worth exploring the notion that masculinity itself may be undergoing a transformation for some men in which products designed to create a more erotic image for men are simultaneously viewed as providing a form of more acceptable, less aggressive, and pleasurable kind of masculinity. Simultaneously, for women, more competitive, higher education, career-oriented and independent choices suggest that the traditional distinction between masculine and feminine may be undergoing significant transformations.

Changing Conceptions of Sexuality: The Emergence of Androgyny

As is true of virtually all social mores and norms, human interactions and communication continually change. We may value some of these changes while we disapprove of and seek to eliminate other changes. Sex-role changes are particularly sensitive issues for many people, and any change is likely to be examined with suspicion. Since the late 1960s, a host of changes in sex roles has been noted. For example, employing measures of assertiveness, Twenge (2001) has argued that women’s scores on assertiveness and dominance scales have increased from 1968 through 1993. She has concluded that, “women’s scores have increased enough that many recent samples show no sex differences in assertiveness.” While men’s scores have not been demonstrated to change, for women this change in assertiveness and dominance constitutes a “social change” that is “internalized in the form of a personality trait” (p. 133). In a broader context, Ivy and Back-lund (1994, p. 58) have observed that “in traditional views of development,” sex roles are cast as either “male or female.” In this conception, the masculine “involves instrumental or task-oriented competence,” and it “includes such traits as assertiveness, self-expansion, self-protection, and a general orientation of self against the world.” In contrast, “femininity is viewed as expressive or relationship-oriented,” whose “corresponding traits include nurturance and concern for others, emphasis on relationships and the expression of feelings, and a general orientation of self within the world.” Ivy and Backlund (1994, p. 58) have concluded that these “traditional views” perpetuate “the male–female dichotomy and limit individuals’ options in terms of variations in identities.” Indeed, in our view, it is now extremely difficult to find anyone who wants to be only “task-oriented” or “relationship-oriented.” At least in the popular parlance, most people now seem to seek a balance between the instrumental and the expressive. In other words, in our experience, people seem to prefer that a task-orientation approach occur within a context of concern for others.

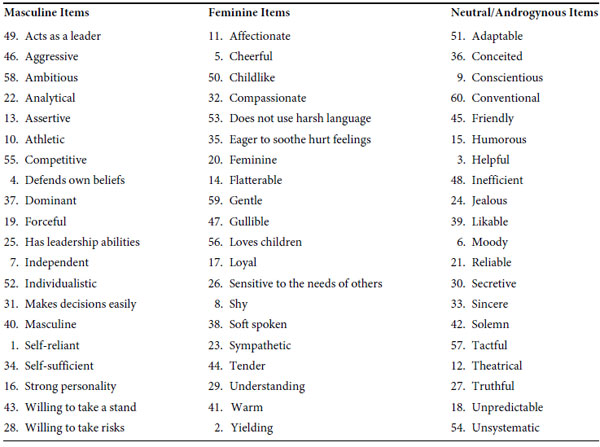

However, it is particularly difficult to find a single concept or notion that reflects the transition that is occurring at the cultural level in masculinity and femininity. We have selected the notion of androgyny. In this regard, androgynous people are often viewed as those who “having characteristics or nature of both male and female” (Webster’s, 1991, p. 84). Yet, such a definition of androgyny brings to mind a host of stereotypes. As we mentioned at the outset of this essay, while the precise issue is sexual preference, a performer such as Adam Lambert is viewed as androgynous, because he wears mascara, has stylized hair, tight clothing, and a slight build. Or, a high fashion model, such as Pejic, who models both male and female clothing, is considered “blessed with beauty” (Morris, 2011). Pejic’s long blond hair and physique allow him to “pass” as a woman. In such cases, transvestite is grouped with the androgynous. While we appreciate the flexibility that a term such as androgyny can possess, we also think that the term can apply to less dramatic and vivid personality types. For example, the Pew Research Center (2008) reported—based upon a representative sample of 2,250 adults living in the continental United States—that people now perceive women as more effective leaders than men. Identifying key traits associated with effective leadership (see Table 21.3), people decisively believe that women are more likely to possess these traits.

Table 21.3 Items for the Masculinity, Femininity, and Neutral/Androgyny: Scales of the Bem Sex-Role Inventory (BSRI)

The terms the Pew Research Center employed to characterize leadership can easily be equated to the cluster of interlocking masculine and feminine terms. In regard to the qualities wanted in leadership, the traits reflect an androgynous rather than either a masculine or feminine perspective. This androgynous leadership style is composed of masculine traits (decisive or makes decisions easily, willing to take a stand, willing to take risks, assertive, intelligent, or analytical), feminine traits (compassionate, outgoing, sensitive to the needs of others, understanding, warm, eager to soothe hurt feelings), and gender-neutral traits (honest, hardworking, creative).

One of the first efforts to establish an alternative to the male–female and related masculinity-femininity bipolar framework was provided by Sandra L. Bem in 1974. Bem argued that, “Both in psychology and in society at large, masculinity and femininity have long been conceptualized as bipolar ends of a single continuum; accordingly, a person has had to be either masculine or feminine, but not both” (p. 155). Employing a term that has upset many, Bem continued her line of thought and proposed that, “many individuals might be ‘androgynous’; that is, they might be both masculine and feminine, both assertive and yielding, both instrumental and expressive—depending on the situational appropriateness of these various behaviors” (p. 155). Therefore some individuals might be androgynous, while other individuals might continue to be explicitly and strongly masculine or feminine.

At the same time, she reasoned, even strongly sex-typed individuals might find it reasonable and effective to limit their solely masculine or feminine sex roles under certain conditions. As Bem argued, “strongly sex-typed individuals might be seriously limited in the range of behaviors available to them as they move from situation to situation” (p. 155). To establish her claims, in a preliminary condition, Bem compiled a list of “approximately 200 personality characteristics” that “seemed to be both positive in value and either masculine or feminine.” She also compiled a list of 200 characteristics that “seemed to be neither masculine nor feminine”—or gender “neutral”—of which “half were positive in value and half were negative” (p. 156). Using these 400 characteristics, individuals were asked to evaluate the desirability (using a seven point Likert-type scale from 1, “not at all desirable,” to 7, “extremely desirable”) of each characteristic for both men and women (e.g., “In American society, how desirable is it for a man to be truthful?” “In American society, how desirable is it for a woman to be sincere?”). Using these ratings, a characteristic was qualified as masculine, for example, only if a statistically significant amount of both males and females applied it to men, but not to women. The same criteria were used to differentiate feminine characteristics. In the final compilation, twenty personality traits made up the masculinity scale, twenty made up the femininity scale, and twenty were selected for the social desirability scale. The traits for this scale were “independently judged by both males and females to be no more desirable for one sex than for the other” (p. 157). Table 21.3 provides the complete list of these sixty characteristics classified as “masculine items,” “feminine items,” or “androgynous items.”

At two different universities, on a seven point Likert-type scale, a total of 917 undergraduate male and female college students (61 percent were males) were asked to determine how well each of the sixty masculine, feminine, and neutral personality characteristics given described him or herself. The results of these self-assessments were classified as either “masculine,” “feminine,” “undifferentiated,” or “androgynous.” The definitions of these categories are provided in Table 21.3.

Among a host of conclusions and implications, Bem established that more than masculine and feminine modes of sexuality existed. She additionally established that masculine and feminine are not bipolar terms along a single continuum. Sexuality, in the context provided by Bem, could also involve undifferentiated and androgynous modes of sexuality. In all, the world of sex roles changed dramatically, becoming a multidimensional set of options and possibilities for all individuals based on circumstances and personal preferences. For some, androgyny itself can be a confusing, if not upsetting, attribute. Seeking to create a more receptive attitude about androgyny, Ivy and Backlund (1994) suggest:

Let’s explore … [the] androgyny concept within gender-role transcendence a bit further. It may make the concept more understandable if you envision a continuum with masculinity placed toward one end, femininity toward the other end, and androgyny in the middle. You don’t lose masculine traits or behaviors if you become androgynous, or somehow become masculine if you move away from the feminine pole. Androgyny is an intermix of the feminine and the masculine. Some androgynous individuals may have more masculine than feminine traits, and vice versa. (pp. 59–60)

Another way to think of androgyny is to perceive it as one of four options or choices that might be selected in any given situation. In some cases, you may decide that a more masculine approach is required and likely to be the most effective strategy. In other cases, a more feminine strategy will be the best choice. In yet another set of circumstances, an androgynous approach—in which both masculine and feminine traits are employed—will function the best. And, finally, in some cases, a sex-role emphasis might be completely inappropriate, you may decide that a more undifferentiated approach will produce the most positive outcome. In other words, rather than believing that individuals are inherently one sex role or another at all times and in all places, we can become more effective communicators when we begin to view sex roles as a choice or option, just as we consciously consider, select, and judge any other kind of strategy for its effectiveness.

In terms of communication practices, we do think an increasing number of people are learning to adopt a rich array of masculine and feminine traits depending upon the people and circumstances they encounter as exemplified by the Pew Research Center (2008) report on leadership traits mentioned earlier.

Moreover, women continue to occupy the dominant leadership position in the home, but a wider variety of sex-role strategies are employed. Morin and Cohn (2008) have reported that “in 43% of all couples it’s the woman who makes decisions in more areas [at home] than the man. By contrast, men make more of the decisions in only about a quarter (26%) of all couples. And about three-in-ten couples (31%) split decision-making responsibilities equally” (p. 1).

Diana Lee (2005) has reported that “androgyny seems to have found its way to global mainstream.” Among those representing this androgynous style, Lee includes Michael Jackson, David Beckham, Angelina Jolie, Boy George, David Bowie, Prince, Sharon Stone, Milla Jovovich, and Uma Thurman. In her view, androgyny combines “both masculinity and femininity as traits of a unified gender that defies social roles and psychological attributes.” While some have argued that an androgynous system will make men and women “interchangeable,” suppress “physicality,” make men “neuter” themselves, and make “ambitious women postpone procreation” (Paglia, 2010), we are not as negative, and we think a host of equally valid alternatives are also possible, including the individualization of men and women beyond gender categories. In all, as we suggest throughout this chapter, people are more likely to become more effective communicators if they can condition and train themselves to view the application of sex roles as an opportunity to make choices and develop strategies that can be judged as more or less effective depending upon the people and circumstances encountered. As Bem (1974) put it nearly forty years ago, “In a society where rigid sex role differentiation has already outlived its utility, perhaps the androgynous person will come to define a more human standard of psychological health” (p. 162).

Conclusion

We cannot leave this discussion of androgyny as a global value without some major qualifications. First, we do not believe that the mix of masculine and feminine traits is universally recognized nor do we think it will be for some time. We do believe, however, that a precise use of terminology should underscore androgyny as an emerging and apt descriptor for many of the styles and roles conveyed through global media systems and especially through global television franchises. At the same time, as we characterize the images and roles of media performers from the 1960s through the first decade of the twenty-first century, we do detect significant departures from traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. From our perspective, a blending of gender and sexual roles is evident, and the most apt label for these changes is androgyny. These transformations—fostered by digital communication technologies such as television franchises—are decidedly global in nature and they now stretch across a fifty-year period. Particularly for younger people throughout the world, we see no reason to believe these gender and sexual role transformations are temporary or likely to return to the more traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. We suspect we are now at the threshold of a new set of changes in gender and sexual roles. We would at least recommend that cross-cultural communication researchers be open to the possibility that some significant transformations may be occurring in at least the masculinity-femininity construct that has dominated this research domain for so many decades.

References

Aldridge, M. G. (2004). What is the basis of American culture? In F. E. Jandt (Ed.), Intercultural communication: A global reader (pp. 84–98). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bem, S. L. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42 (2), 155–162.

Borisoff, D. J., & Chesebro, J. W. (2011). Communicating power and gender. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

Brennan, E. (2012). A political economy of formatted pleasures. In T. Oren & S. Shahaf (Eds.), Global television formats: Understanding television across borders (pp. 71–89). New York, NY: Routledge.

Chesebro, J. W. (2000). Communication technologies as symbolic form: Cognitive transformations generated by the Internet. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, 1, 8–13.

Chesebro, J. W., Kim, J. K., & Lee, D. (2007). Strategic transformations in power and the nature of international communication theory, China Media Research, 3(3), 1–13.

Delmeiren, C. (2009, October 22). Rape troubles nearly all in South Africa. The Gallup Poll. Retrieved October 22, 2009 from http://www.gallup.com/poll.

Ding, Y. X. (2007). A critical comparison of American Idol and Super Girl: A cross-cultural communication analysis of American and Chinese cultures (Unpublished master’s thesis). Ball State University, Muncie, IN.

Fatherhood Institute, The. (2010, December). The fatherhood report 2010–2011: The fairness in families index. Retrieved December 2010 from www.fatherhoodinstitute.org.

Geidner, N. W., Flook, C. A., & Bell, M. W. (2007, April). Masculinity and online social networks: Male self-identification on Facebook.com. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Eastern Communication Association, Providence, RI.

Gettleman, J. (2009, August 5). Latest tragic symbol of unhealed Congo: Male rape victims. The New York Times, pp. A1, A7.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequence: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hymowitz, K. S. (2009, July 3). Losing confidence in marriage. The Wall Street Journal, p. W11.

Internet World Stats. (2011, December 31). Retrieved May 10, 2012, from http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

Itzkoff, D. (2009, November 28). CBS is criticized for blurring of video. The New York Times, p. C2.

Ivy, D. K., & Backlund, P. (1994). Exploring genderspeak: Personal effectiveness in gender communication (4th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Kirkbride, P. S., Tang, S. F. Y., & Westwood, R. I. (1991). Chinese conflict preferences and negotiating behavior: Cultural and psychological influences. Organization Studies, 12, 365–386.

Kohut, A., Wike, R., Horowitz, J. M., Simmons, K., Poushter, J., Barker, C., Bell, J., & Gross, E. M. (2011). Global digital communication: Testing, social networking popular worldwide. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Konigsberg, R, D. (2011). Chore wars: Men are now pulling their weight at work and at home. So why do women still think they are slacking off? The New York Times.

Kristof, N. D., & WuDunn, S. (2009, August 23). The women’s crusade. The New York Times Magazine, pp. 28–39.

Lee, D. (2005, March). Androgyny becoming global? Retrieved from http://uniorb.com/RCHECK/RAdrogyne.htm.

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., Smith, A., Purcell, K., Zickuhr, K., & Raine, L. (2011). Teens, kindness and cruelty on social networking sites: How American teens navigate the new world of digital citizenship. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Liang, L, H. (2010). Chinese students suffer as university entrance exams get a grip. Retrieved from the Guardian website at http://www.guardian.co.uk/education/2010/jun/28/chinese-university-entranceexams.

Madden, M., & Zickuhr, K. (2011). 65% of online adults use social networking sites. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Magni, M., & Atsmon, Y. (2010, February 24). China’s Internet obsession. Harvard Business School, 88(2). Retrieved May 10, 2012 from http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2010/02/chinas_internet_obsession.html.

http://www.nytimes.com/imagepages/2012/02/12/opinion/sunday/12-coontz-gfx.html.

McKinley, J. C., Jr. (2009, December 13). Houston is largest city to elect openly gay mayor. The New York Times, p. A34.

McMahan, D. T., & Chesebro, J. W. (2003). Media and political transformations: Revolutionary changes of the world’s cultures. Communication Quarterly, 51, 126–153.

Morin, R., & Cohn, D’V. (2008, September 25). Gender and power: Women call the shots at home; on the jobs, leadership preferences are mixed. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org.

Morris, A. (2011, August 14). The prettiest boy in the world. New York Magazine. Retrieved January 12, 2012 from http://nymag.com/print/?/fashion/11/fall/andreji-pejic.

Mundy, L. (2012). The richer sex: How the new majority of female breadwinners is transforming sex, love, and family. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Murphy, R., Falchuk, B., Loreto, D. D., & Brennan, I. (2009). Glee [Television series]. Los Angeles, CA: Fox.

O’Reilly, B. (2012, April 19). The O’Reilly factor [Television broadcast]. United States: Fox News Channel.

Paglia, C. (2010, June 27). No sex please, we’re middle class. The New York Times, p. WK12.

Patten, E., & Parker, K. (2012, April 19). A gender reversal on career aspirations. Pew Social and Demographic Trends. Retrieved from www.pewsocialtrends.org/2012/04/19/a-gender-reversal-on-career-aspirations.

Pempek, T. A., Yermolayeva, Y. A., & Calvert, S. L. (2009). College students’ social networking experiences on Facebook. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30, 227–238.

Pew Research Center. (2008, August 25). Men or women: Who’s the better leader? Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/932/men-or-women-whos-the-better-leader.

Pew Research Center. (2010, July 1). Gender equality universally embraced, but inequalities acknowledged. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, Global Attitudes Project.

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010, January). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. Menlo, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Sen, B. (2012). Idol worship: Ethnicity and difference in global television. In T. Oren & S. Shahaf (Eds.), Global television formats: Understanding television across borders (pp. 203–222). New York, NY: Routledge.

Siibak, A. (2009). Constructing the self through photo selection: Visual impressions management on social networking websites. Cyberpsychology: Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 3, 1–9.

Suddath, C. (2010, May 17). Music pop star 2.0: The Internet-fueled rise of Justin Bieber. Time, 175(19), 49–50.

Teachout, T. (2009, July 25). Does Broadway need women? The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved July 27, 2009 from http://online.wsj.com/home-page.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1999). Communicating across cultures. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Twenge, J. M. (2001, July). Changes in women’s assertiveness in response to status and roles: A cross-temporal meta-analysis, 1931–1993. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(1), 133–145.

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2011, August 17). Women see value and benefits of colleges; men lag on both fronts, survey finds. Pew Social and Demographic Trends. Retrieved from: www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/08/17/women-see-value-and-benefits-of-college-men-lag-on-both-fronts-survey-finds.

Walther, J. B., Van Der Heide, B., Kim, S-Y., Westerman, D., & Tong, S. T. (2008). The role of friends’ appearance and behavior on evaluations of individuals on Facebook: Are we known by the company we keep? Human Communication Research, 34, 28–49.

Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. (1991). Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

Whitty, M. T. (2008). Reveal the “real” me, searching for the “actual” you: Presentations of self on an internet dating site. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(4), 1707–1723.

Wu, J. (2012). The Impact of global media on American and Chinese cultures: An axiological analysis of America’s Got Talent and China’s Got Talent (Unpublished master’s thesis). Ball State University, Muncie, IN.