Chapter 7

Constitution of a Trust

Chapter Contents

Constituting the Trust and the Relationship with Creating a Trust

When is a Trust Completely Constituted?

How a Trust is Completely Constituted

This chapter addresses the final ingredient necessary to form an express trust: that the trust must be constituted. At its most fundamental level, all this means is that the settlor must transfer legal ownership in the trust property to the trustee (or, alternatively, hold it on trust for the beneficiary himself). The trustee will then hold the property on trust for the beneficiary. Yet settlors have often failed either to transfer the ownership of the trust property to a trustee clearly or confirm that they are now holding the property as a trustee. The issue is to what extent equity is prepared to step in and recognise a trust despite its two maxims that it will not perfect an imperfect gift or assist a volunteer.

As You Read

Look out for the following key issues:

![]() what is meant by a trust being ‘completely constituted’ and how that has changed from a rigid, objective requirement in the nineteenth century to a more flexible concept in contemporary case law;

what is meant by a trust being ‘completely constituted’ and how that has changed from a rigid, objective requirement in the nineteenth century to a more flexible concept in contemporary case law;

![]() how this topic is underpinned by two equitable maxims: that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift and will not assist a volunteer; and

how this topic is underpinned by two equitable maxims: that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift and will not assist a volunteer; and

![]() how and when a trust can be completely constituted.

how and when a trust can be completely constituted.

Constituting the Trust and the Relationship with Creating a Trust

The essential requirements for the creation of an express trust are that the trust must be both declared and constituted. The requirements to declare a trust have been considered in the previous three chapters. They are that the trust must:

[a] be established by a settlor with mental and physical capacity who must, if the type of trust property requires it (for example, land 1 ad here to any necessary formalities;2

[b] comply with the three certainties. The settlor must intend to declare a trust, that the trust property and the intended beneficial interests in it must be sufficiently certain and that the objects of the trust must also be clear, so that in all cases the trust can be administered by the trustees; 3

[c] adhere to the beneficiary principle which, as a general rule, provides that the trust must be intended to benefit ascertainable human beneficiaries, as opposed to pursue a purpose;4

[d] not infringe the rules against perpetuity. The most significant of these is that the trust property must nowadays vest in its intended beneficiaries within a fixed perpetuity period of 125 years from when the trust comes into effect.5

Complying with these four requirements ensures that the express trust has been properly declared. In addition, the trust must be completely constituted. The trust will not be valid unless it has been constituted.

Constitution of a Trust

Key Learning Point

A trust is constituted when the trust property is transferred from the settlor to the trustee or the settlor holds the property on trust for the beneficiaries. At this point, the trustee becomes the legal owner of the property and holds it on trust for the beneficiary who, of course, has an equitable interest in it.

To understand why a trust must be completely constituted, the relationship between the trust and a gift has to be examined. Equity has two maxims which underpins its treatment of gifts and these also apply to trusts. Those are:

[a] equity will not perfect an imperfect gift; and

[a] equity will not assist a volunteer.

The relationship between a gift and a trust

There is a relationship between a gift and a trust, which was explained by Arden LJ in Pennington v Waine:6 ‘[a] gift can be made either by direct assignment, by a transfer to trustees or by a [self] declaration of trust.’7

This dictum can be illustrated by Figure 7.1. In all of the following examples in Figure 7.1, assume that the benefactor wishes to benefit the recipient by the amount of £10,000.

Both the second and third examples in Figure 7.1 involve the settlor setting up a trust. In Arden LJ’s first method of declaring a trust, the property which forms the subject of the gift (£10,000) is transferred to trustees, whereas in her second method, the settlor physically keeps hold of the money himself but on the basis that he declares himself to be a trustee of it.

There are fundamental differences between a gift and a trust. As can be seen from Figure 7.1, a gift involves the donor giving away the property entirely. The donor thus gives away all rights and liabilities in the property to the donee. The donee receives both legal and equitable interests in the property and it becomes his to do with as he generally wishes. The donee is the absolute owner of the property.

A trust, on the other hand, means that whilst the settlor gives away the rights and liabilities in the property to a trustee, the ownership in the property is split. The trustee retains the legal interest and the beneficiary acquires an equitable interest. The trustee then administers the trust for the beneficiary’s benefit. The beneficiary’s rights in the property are limited to the interest he enjoys. If, for instance, the beneficiary has only a life interest in the property, he can enjoy only the income from the trust property for his lifetime. If this was the case in Figure 7.1, the beneficiary would simply receive the interest on the £10,000, rather than the capital sum of £10,000. It is only when a beneficiary becomes entitled to the absolute interest in the trust property that he may seek, provided he is over 18 years of age and mentally capable, to call for the legal interest in the trust property to be transferred to him, merge the legal and equitable interests together and end the trust. This is known as the rule in Saunders v Vautier. 8 vIt is not until that point that the interests will be joined together again.

As trusts are effectively part of the overarching notion of a gift, the equitable maxim that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift applies to all trusts in the same way as making a straightforward gift.

The notion that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift illustrates that equity will not assist everyone on each occasion.9 Equity will not ‘right’ a ‘wrong’. If a trust has not been constituted correctly by a settlor, equity will not finish the job of setting up the trust correctly for them. The trust will not, therefore, have been completely constituted by the settlor and, as such, it will not have been validly created.

Equity will also not assist a volunteer. A volunteer is someone who has not provided any consideration in the transaction. Again, if a settlor has failed to constitute the trust completely, the beneficiary, albeit wholly innocent, will not be allowed to claim any beneficial interest in the trust property. The beneficiary in these circumstances is a volunteer. He has provided no consideration for the transaction and equity will not help him. This appears to flow from part of the general principles of the law of consideration where, to enjoy rights in English law, one must generally have given something to acquire those rights. If the trust is not completely constituted, the beneficiary will have acquired no rights in the trust property and has no basis on which to enforce any such rights.

Constitution of a trust can be broken down into two distinct parts:

![]() When is a trust completely constituted?

When is a trust completely constituted?

![]() How is a trust completely constituted?

How is a trust completely constituted?

When is a Trust Completely Constituted?

As You Read

When you read this part of the chapter, bear in mind:

![]() the fundamental concept that, whilst it is equity that recognises a trust, equity traditionally took the position of an onlooker as opposed to an intervener. Due to its equitable maxims, equity would not assist a defective trust to be created because to do so would infringe the principles of not assisting a volunteer and perfecting an imperfect gift;

the fundamental concept that, whilst it is equity that recognises a trust, equity traditionally took the position of an onlooker as opposed to an intervener. Due to its equitable maxims, equity would not assist a defective trust to be created because to do so would infringe the principles of not assisting a volunteer and perfecting an imperfect gift;

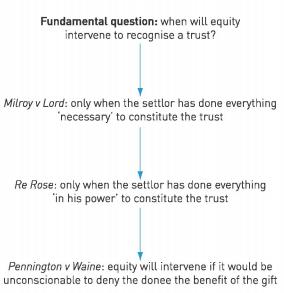

![]() the original — and objective — principle for equity to recognise a trust as having been completely constituted was that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the trust property to the trustees;

the original — and objective — principle for equity to recognise a trust as having been completely constituted was that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the trust property to the trustees;

![]() how that objective principle has been eroded over the years by the inclusion of a more subjective element which meant that a trust would be constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything in his power’ to create the trust; and

how that objective principle has been eroded over the years by the inclusion of a more subjective element which meant that a trust would be constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything in his power’ to create the trust; and

![]() the more recent development of the Court of Appeal in the key case of Pennington v Waine which appears to develop a new test based on the equitable concept of ‘unconscionability’ to ascertain whether the trust should be seen to be constituted or not. This test seems to result in equity taking an interventionist approach to the constitution of a trust and infringe its two guiding maxims in this area.

the more recent development of the Court of Appeal in the key case of Pennington v Waine which appears to develop a new test based on the equitable concept of ‘unconscionability’ to ascertain whether the trust should be seen to be constituted or not. This test seems to result in equity taking an interventionist approach to the constitution of a trust and infringe its two guiding maxims in this area.

The original test — has the settlor done ‘everything necessary’ to constitute the trust?

Originally, a trust would only be completely constituted when the settlor did everything necessary for the trust property to be transferred to the trustee or to declare himself a trustee. It is only when it could be said that the settlor had taken all necessary steps that the trust could be considered binding on the settlor. What was required was an objective assessment of whether all necessary steps had been taken by the settlor: it is only if they were taken that the trust would have been completely constituted.

This test of whether the settlor had taken all necessary steps to transfer the property to a trustee or to declare himself trustee of it was set out in Milroy v Lord.10

The case concerned an attempt by a resident of New Orleans, Thomas Medley, to set up a trust of 50 of the shares that he owned in the Bank of Louisiana. By a deed dated 2 April 1852, Thomas purported to transfer the shares to his father-in-law, Samuel Lord, so that Samuel would hold the shares on trust for Thomas’ English niece, Eleanor Dudgeon. That meant that the income from the shares — the dividends that the Bank may declare — would be paid to Eleanor. Acting upon this declaration of trust, Thomas gave the share certificates to Samuel. Thomas also gave Samuel both a general power of attorney to act on his behalf in relation to his financial affairs and a specific power of attorney in relation to the dividends which may have been paid by the Bank of Louisiana.

Glossary: Power of Attorney

A power of attorney is a document in which a person (the donor) may appoint another to act on their behalf. The recipient thus stands in the donor’s shoes and acts as if he was the donor.

The power might be general or specific. A general power of attorney enables the recipient to act on the donor’s behalf to manage all of the donor’s affairs. A specific power of attorney is where the donor limits the recipient to acting for him in relation to defined property.

The problem in the case arose because the Bank of Louisiana’s constitution provided that for shares to be transferred into the name of a recipient, the actual share certificates being transferred had to be sent to the Bank. In addition, if a transfer was to be made by a person using a power of attorney, the original power of attorney also had to be lodged with the Bank when the application to transfer the shares was made.

The share certificates were never sent to the Bank. But Samuel Lord acted as though the trust had been properly established. He received the dividends declared by the Bank and paid them over to Eleanor, who by now had married and had become Eleanor Milroy.

Thomas Medley died in 1855. Samuel Lord continued to be willing to honour the trust. It was Thomas’ executor, Mr Otto, who objected to the trust. His argument was that there had been no successful creation of a trust, but instead simply an incomplete gift. This was based on the fact that the share certificates had never been transferred fully into the trustee’s name. All that had occurred was that the settlor had physically handed over the share certificates to the trustee. No legal transfer had taken place. Such a transfer could only be undertaken by the Bank of Louisiana receiving the old share certificates in Thomas Medley’s name and issuing new ones in the name of Samuel Lord. Equity could not perfect this imperfect gift. In addition, Eleanor had provided no consideration for the gift of the shares from her uncle and, as such, she was a volunteer. Equity should not assist a volunteer.

The Court of Appeal agreed with Mr Otto’s argument. The legal ownership in the shares had never passed to Samuel. As the trust had not been constituted, he could not be considered to be a trustee of the shares for Eleanor.

In a well-known dictum, Turner LJ set out when a trust could be considered to be completely constituted:

I take the law of this Court to be well settled, that, in order to render a voluntary settlement valid and effectual, the settlor must have done everything which, according to the nature of the property comprised in the settlement, was necessary to be done in order to transfer the property and render the settlement binding upon him.11

Of course, Samuel Lord had had the benefit of two powers of attorney granted by Thomas Medley under which Samuel could have stepped into Thomas’s shoes and instructed the Bank of Louisiana to transfer the shares into his name. But Samuel had not actually used his authority under either of the powers of attorney to transfer the legal ownership of the shares into his name.

It also made no difference that Samuel had considered himself a trustee of the shares from the moment that the ‘trust’ had been declared by Thomas, by paying the dividends declared by the Bank to Eleanor. This action, too, was irrelevant. It could not ‘right’ the ‘wrong’ of the trust being incompletely constituted by Thomas when it was originally set up.

Equity would not intervene to correct the imperfections of this attempted trust. To do so would infringe its two maxims. The trust had to be completely constituted by the settlor himself for it to be recognised by equity. It would only be completely constituted if the settlor had done ‘everything necessary’ to transfer the legal title in the trust property to the trustee.

Making connections

Look again at the dictum Turner LJ uses for what a settlor must do to create a valid trust in Milroy v Lord. There appear to be two requirements:

[a] the settlor must have done everything ‘necessary to be done’ to transfer the property.This appears to be an objective test, focussing on whether the settlor has done everything physically necessary to transfer the legal title to the trustee; and

[b] the settlor’s actions must be undertaken with the mental element that his actions under-taken should be done with an intention that the trust should becoming binding upon him.

Do you think there is an element of cross-fertilisation with certainty of intention here? At its roots, certainty of intention requires the settlor to display an intention to create a valid trust. It appears that the actions the settlor takes in constituting the trust must be undertaken with a similar intention. Perhaps, however, there is a distinction that can be made. Certainty of intention focuses on an objective intention by the settlor to declare a trust. Intention in constituting the trust requires the settlor to acknowledge that he is, in effect, putting the trust property beyond his own reach. He can do this either by transferring the property physically to a trustee or, alternatively, retaining the legal interest for himself whilst confirming that the beneficial interest is held on trust for the beneficiary.

It is the words of Turner LJ that the settlor must have done ‘everything necessary’ for the trust to be completely constituted and therefore be recognised by equity that the courts have focused on in succeeding cases.

The next significant case in which Turner LJ’s words were examined was Re Fry.12 Ambrose Fry was an American resident who owned shares in Liverpool Borax Ltd. He wanted to give his shares away. He signed transfer documents to transfer 2,000 shares to his son, Sydney and the remainder to Cavendish Investment Trust Ltd (‘the Investment Trust’). The transfer documents eventually found their way to Liverpool Borax Ltd who refused to register the transfer of the shares due to wartime restrictions then in place. Before any shares in the company could be registered in a new owner’s name, the consent of the United Kingdom Treasury had to be obtained. This required Mr Fry to complete and return a number of supplementary docu-ments. Although he did so, he died before the Treasury had given its consent to the transfers of the shares.

The action came before Romer J. Sydney and the Investment Trust argued that Mr Fry had done everything he could possibly have done to affect the transfers of the legal interests in the shares to those two recipients. It was out of Mr Fry’s control that the Treasury had not given its consent. The case could, they argued, be distinguished from Milroy v Lord where the share certificates had never reached the company for them to be transferred into the recipient’s name.

Romer J cited the test propounded by Turner LJ in Milroy v Lord and asked 13 ‘[H]ad every-thing been done which was necessary to put the transferees into the position of the trans-feror?’ He answered the question almost immediately:

[I]t is impossible, in my judgment, to answer the questions other than in the negative. The requisite consent of the Treasury to the transactions had not been obtained, and, in the absence of it, the company was prohibited from registering the transfers. In my opinion, accordingly, it is not possible to hold that, at the date of the testator’s death, the transferees had …. acquired a legal title to the shares in question.….14

As an alternative, Sydney and the Investment Trust argued that Mr Fry had done enough to transfer just the equitable interest in the shares to themselves. Applying Turner LJ’s test again to this argument, Romer J again came to the conclusion that everything necessary to be done to transfer the shares into the names of Sydney and the Investment Trust had not been done. The Treasury’s consent had not been obtained to the transfer taking place. Until that consent was given, ‘everything necessary’ to be done had not been done.

Re Fry appears to be a straightforward application of the principle set out in Milroy v Lord, albeit with a harsh result. Romer J himself confessed that he arrived at his conclusion that there was an imperfect gift ‘with regret’, 15 but found that there was no other logical decision at which he could arrive. Mr Fry had indeed done everything that he could have done: the share certificates had been sent to the company and all necessary forms completed to obtain the Treasury’s consent to the transfer had been completed and despatched to the Treasury. But ‘everything necessary’ to be done had not been done. The Treasury’s consent was the final piece of the jigsaw and that piece had not been put into place.

The case illustrates the objectivity of the test in Milroy v Lord. The number of steps to effect the gift or create the trust that the settlor may have taken are irrelevant. So too is the fact that the settlor may not, as Mr Fry was, be in a position to take any additional steps to complete the gift or constitute the trust. The key is whether ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the legal title in the property to the trustee has been done or not. There are no shades of grey in the answer: just a black-and-white ‘yes’ or ‘no’. If the answer is ‘no’, equity will not step in to help claimants in the place of Sydney and the Investment Trust because equity will not assist a volunteer or perfect the imperfect gift.

The changing concept of ‘everything necessary’

The courts, however, started to shift from this solidly objective approach to whether ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the property had been done to a test which encapsulated a more subjective element to it. The first case in which this shifting approach was seen was Re Rose.16

The facts concerned two transfers of shares in a company by Eric Rose. In the first transfer, he gave 10,000 shares to his wife, Rosamond, by way of gift. In the second, he gave a further 10,000 shares to his wife and another recipient, so that they could be held on trust for his wife and his son. Both transfer documents were executed on 30 March 1943, but the transfers were not registered by the company until 30 June 1943. When Mr Rose died, the Inland Revenue claimed tax on the transfers. A new tax had become effective on 10 April 1943.

Counsel for Mrs Rose argued that no tax should be payable on either of the transfers as they were effective when the documents to transfer the shares were executed on 30 March 1943. The difficulty with this argument was that it seemed to run contrary to the principle in Milroy v Lord. According to Turner LJ’s dictum in Milroy v Lord, the transfers would not be effective until ‘everything necessary’ to be done to transfer the property had been done. Until that point, the property would remain in the hands of Mr Rose. ‘Everything necessary’ to be done in the case of a share transfer included the company registering the transfer of the shares from the former to the new owner. This step was not taken until the end of June, by which time the new tax had come into operation.

The Court of Appeal distinguished Milroy v Lord, holding that its ratio did not apply in the present case. Mr Rose’s transfer was always intended to take effect immediately upon its execution on 30 March 1943. As such, the transfer was a way of signalling that he was willing to give away all of his rights in the shares. Between the execution of the transfer and the date of registration of it by the company, Mr Rose became a trustee of the legal interest for the transferees. Evershed MR quoted with approval the decision of Jenkins J in a different case entitled Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose,17 in which he said that the decisions in Milroy v Lord and Re Fry:

turn on the fact that the deceased donor had not done all in his power, according to the nature of the property given, to vest the legal interest in the property in the donee. In such circumstances it is, of course, well settled that there is no equity to complete the imperfect gift.18

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Rose19 was, therefore, to add a twist to the decisions in Milroy v Lord and Re Fry. It made a distinction between gifts made where there were potentially more steps for the donor to take and those where the donor had taken all of the steps that he personally could take. Milroy v Lord and Re Fry were examples of the former situation. In Milroy v Lord, there was more for the donor to do to perfect the transfer: he needed to use the correct form and start the procedure again. In Re Fry, the donor needed to obtain the Treasury’s consent to the proposed transfer of the shares, which he failed to obtain. Jenkins J had explained in Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose that both of those earlier cases had actually focused on whether the donor had done everything he could possibly do to perfect the gift. In that manner, the facts in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose could be distinguished from Milroy v Lord and Re Fry. In both of those former cases, the donor had, in fact, done everything he could have done to perfect the gift. The remaining steps needed to be undertaken to perfect the gifts were to be undertaken by other individuals.

The decisions in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose brought a subjective element into Turner LJ’s dictum by asking whether the donor had done everything that he could do in order to constitute the gift or trust. If he had done so, then the gift would be perfected or the trust constituted.

In either situation, equity’s maxims of not perfecting an imperfect gift and not assisting a volunteer would still be honoured. There was no need for equity to intervene to perfect the gift or assist the beneficiary as the trust had been completely constituted by the settlor doing everything in his power to transfer the legal title in the property to the trustee.

The difficulty is that such a subjective approach does not sit easily with the decision in either Milroy v Lord or Re Fry. There is no hint in Turner LJ’s test in Milroy v Lord of a subjective element being mentioned: the test seems entirely objective. In Re Fry, it is arguable that Mr Fry had indeed done everything in his power that he could have done to bring about the transfers of the shares, but still Romer J held that the objective test in Milroy v Lord had not been satisfied. Whilst bringing in an element of subjectivity may have led to the ‘right’ result on the facts in both Re Rose; Midland Bank Executor and Trustee Co Ltd v Rose and Re Rose, it is hard to see how it is supported by previous authority. The decision in Re Rose was, however, approved obiter by Lord Wilberforce in Vandervell v IRC 20 where he said that Mr Vandervell had done everything in his power to constitute the trust when he orally directed his trustees to transfer the shares to the Royal College of Surgeons.

The beginnings of equity’s interventionist approach: a new test based on conscience’

A more interventionist approach was started by the decision of the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarani21

The facts revolved around Thakurdas Choithram Pagarani, an Indian man who established a chain of supermarkets around the world. He became very wealthy as a result and, having made provision for his family, wanted to leave much of his money to charity. To do so, he established a charitable foundation, Choithram International Foundation. On the same day, he confirmed orally that he wanted to give all of his wealth to the Foundation, which the Foundation could use for various charitable purposes.

The difficulty arose because the shares and money he instructed to be transferred to the Foundation were not transferred. Mr Pagarani gave instructions to his accountant to undertake the transfers but some of the transfers were never made until after his death. The issue for the court was whether the gifts made by Mr Pagarani could be perfected by those transfers entered into after his death. The High Court of the British Virgin Islands and the Court of Appeal of the British Virgin Islands had both held that Mr Pagarani had made incomplete gifts to his Foundation. The Privy Council disagreed.

In delivering the opinion of the judicial Board, Lord Browne-Wilkinson found that the facts did not fall squarely within the principle of Milroy v Lord. There was no complete gift effected by Mr Pagarani to another recipient nor did he declare himself a trustee of the property for the Foundation. Instead, when Mr Pagarani had expressed the desire to give the money and shares to the Foundation, he intended to give that property to the trustees of the Foundation for them to hold on trust for the Foundation’s charitable purposes. That was the only logical way to construe Mr Pagarani’s words. Lord Browne-Wilkinson explained that the maxim that equity would not assist a volunteer was a simplification of that principle as far as trusts were concerned:

Until comparatively recently the great majority of trusts were voluntary settlements under which beneficiaries were volunteers having given no value. Yet beneficiaries under a trust, although volunteers, can enforce the trust against the trustees. Once a trust relationship is established between trustee and beneficiary, the fact that a beneficiary has given no value is irrelevant.22

This explained why a beneficiary had standing to enforce a trust against a trustee, despite the beneficiary having given no consideration and therefore being a volunteer, ‘the donor has constituted himself a trustee for the donee who can as a matter of trust law enforce that trust’.23

By holding the shares and money designed for the Foundation in his own name, Mr Pagarani had effectively appointed himself a trustee of that property for the Foundation. This trust was completely constituted even though the trust property was not also vested in the names of the other trustees of the Foundation. Lord Browne-Wilkinson explained that the issue depended on conscience:

There can in principle be no distinction between the case where the donor declares himself to be sole trustee for a donee or a purpose and the case where he declares himself to be one of the trustees for that donee or purpose. In both cases his conscience is affected and it would be unconscionable and contrary to the principles of equity to allow such a donor to resile from his gift.24

The issue as to whether the gift was perfect therefore depended on whether it would be conscionable for the donor to change his mind and reclaim the gift from the donee. If it would be unconscionable for the donor to do so, the gift would be constituted.

Decisions of the Australian courts have followed this line of thinking. Comments ofYoung CJ in the Supreme Court of New South Wales decision in Blackett v Darcy25 confirmed that the maxim that ‘equity will not assist a volunteer’ did not completely sum up the maxim in its entirety:

It must always be remembered that the rule that equity does not assist a volunteer is not a complete statement of the law and is only relevant if the donee requires the assistance of a court of equity in order to gain the property.26

An illustration of the point made by Young CJ arose on the facts of Djordjevic v Djordjevic.27 A father gave his son two cheques, totalling AUS ![]() 120,000. The son paid the cheques into his own account. Later, the father tried to reclaim the money from his son. He alleged that he only ever intended to lend his son the money, so that his son could pay for a house for his father at an auction that he was to attend. The son’s evidence was that his father gave him the money so that he could buy himself a property in which to live whilst at university.

120,000. The son paid the cheques into his own account. Later, the father tried to reclaim the money from his son. He alleged that he only ever intended to lend his son the money, so that his son could pay for a house for his father at an auction that he was to attend. The son’s evidence was that his father gave him the money so that he could buy himself a property in which to live whilst at university.

Simos J preferred the son’s evidence and held that there was a complete gift of the ![]() 120,000 to the son. As the cheques were paid by the father’s bank, the gift was complete. Although the son was a volunteer in that he had provided no consideration for the money from his father, equity would recognise the gift. However, equity was not assisting a volunteer and did not need to assist a volunteer because the gift was already perfect. His father had transferred both legal and equitable interests in the money to the son. All equity had to do was to recognise the gift as perfect.

120,000 to the son. As the cheques were paid by the father’s bank, the gift was complete. Although the son was a volunteer in that he had provided no consideration for the money from his father, equity would recognise the gift. However, equity was not assisting a volunteer and did not need to assist a volunteer because the gift was already perfect. His father had transferred both legal and equitable interests in the money to the son. All equity had to do was to recognise the gift as perfect.

Equity’s interventionist approach taken further: The key case of Pennington v Waine28

This test, based on conscience, has been developed further by the decision of the Court of Appeal in Pennington v Waine. The Court of Appeal focused heavily on the broad principle of unconscionability underpinning equitable principles to come to the conclusion that this broader test could be used to determine if a gift should be perfected or a trust completely constituted.

The facts concerned a family transaction between an aunt and her nephew. Ada Crampton wanted to give 400 shares in Crampton Bros (Coopers) Ltd to her nephew, Harold. She also wanted to make him a director of the company which, as the majority shareholder, she had the power to do. In September 1998, Ada instructed Mr Pennington, one of the company’s auditors, to prepare the necessary forms to make Harold a director of the company and to transfer the shares to him. Mr Pennington duly prepared the forms, Harold signed them and returned them to him. Mr Pennington confirmed in writing to Harold that there were no further steps that Harold had to undertake. The problem arose because the stock transfer form, used to transfer the shares from Ada to Harold, should have been sent to the company for registration. This was never done; instead, it remained on Mr Pennington’s file.

Ada wrote her will in November 1998 in which she left the balance of her shares in the company to other individuals. She made no mention of the 400 shares, presumably because she thought she had transferred them to Harold. Shortly after she had executed her will, Ada died.

The issue for the Court of Appeal was whether or not the gift to Harold of the 400 shares was effective. If it was not effective, the gift would fall into the residuary estate under her will and would go to those residuary beneficiaries. The problem was, of course, that Ada had not done ‘everything necessary’ which should have been done to complete the gift. ‘Everything necessary’ here would have involved the company registering the transfer of shares into Harold’s name. If the more subjective test in Re Rose had been applied, arguably Ada could not show that she had met that either — she had not done everything ‘in her power’ to transfer the shares to Harold as this would have entailed sending the form to the company for registration, rather than sending it to her accountant.

In giving the leading judgment of the court, Arden LJ reviewed the authorities and concluded that the test underpinning them all was based on unconscionability. If it would be unconscionable, as against the donee of the gift, for the donor to change his mind, then equity would perfect the imperfect gift. Arden LJ quoted29 a dictum from Lord Browne-Wilkinson in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini:30 ‘[a]lthough equity will not aid a volunteer, it will not strive officiously to defeat a gift.’

There can be no comprehensive list of factors which makes it unconscionable for the donor to change his or her mind: it must depend on the court’s evaluation of all the relevant considerations.31

Here the relevant considerations were that it was Ada’s decision to give the shares to Harold, she advised Harold she was going to give him the shares, she executed the relevant transfer forms and Mr Pennington had specifically advised Harold that he need do nothing more to receive them. Given these circumstances, it would have been unconscionable, as against Harold, for Ada to have changed her mind and revoked her gift. As such, equity would intervene and perfect the imperfect gift. It would also, of course, assist Harold as a volunteer who had provided no consideration for the gift. Ada became a constructive trustee of those shares in Harold’s favour from the point she signed the transfer form due to the fact that by that stage, it would have been unconscionable for her to revoke the gift.

Pennington v Waine is a landmark decision. The Court of Appeal sanctioned equity’s interven-tion for the first time both to perfect an imperfect gift and assist a volunteer. Before this decision, the courts took the view that equity merely recognised a gift or trust that a settlor had to constitute correctly himself. But there can be no doubt that the gift in Pennington v Waine was not completely constituted, as the documents never reached the company for the legal title to be transferred.

Do you think that Arden LJ was right to apply the principle of conscience from the decision of the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini?

In the latter case, Mr Pagarini had always owned the trust property himself. It was perhaps not surprising that when he declared that he wanted the property to go to the Foundation, that wish should be sufficient to hold that the property was held by him on trust and also vested in the Foundation’s other trustees. Mr Pagarani’s situation was novel but there was, ultimately, an express declaration of trust and a trustee of that trust. But in Pennington v Waine, there was no question of a trust being set up. There was, unlike in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini, no declaration of trust and no trustee. Ada definitively wished to gift the shares to Harold. It was a much bigger step in Pennington v Waine for the court to hold that the entire transfer of the gift should be recognised on the basis of conscience than it was in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini to hold that property already vested in one trustee should also be seen to be held by the other trustees.

Arguably, the Court of Appeal in Pennington v Waine wrongly applied the principle from T Choithram International SA v Pagarini to the same situation that had been addressed clearly on a number of occasions (for example, in both Milroy v Lord and even Re Rose). On this basis, can you support the decision in Pennington v Waine?

Pennington v Waine was considered by the High Court in Curtis v Pulbrook.32

The case concerned purported transfers of shares in Farnham Royal Nurseries Ltd by Henry Pulbrook to his wife and daughter. Henry was a director of the company. He was also a trustee of a trust of whom the Towns family were beneficiaries. Henry transferred 14 shares in the company to his daughter, Alice. He issued a new share certificate with her name on it and signed a stock transfer form transferring the shares to her, albeit that the stock transfer form only came to light some two years after the purported transfer had occurred. He transferred a further 300 shares in the company to his wife, Anucha using similar documentation. In the meantime, Henry had (unlawfully) made substantial payments from Mr and Mrs Towns’ personal joint bank account, using a power of attorney that had been executed appointing him their attorney. Henry and Anucha then emigrated to Thailand. The Towns sought the return of these share transfers, arguing that the shares had never been transferred to the recipients. The issue was whether legal and/or equitable title to the shares had been successfully transferred to Alice and Anucha.

Briggs J found that one of the reasons Henry tried to transfer the shares to Anucha was fear of a claim by the Towns against him that he had misused the power of attorney to withdraw money from their personal joint account. Henry thought they would sue him, and so he tried to divest himself of what he thought were assets that he owned.

Briggs J held that legal title to the shares had not been transferred to Alice or Anucha. Although a director of the company, Henry had had no authority to issue new share certificates to anyone or record their names as new shareholders on the company’s register. On the facts of the case, a minimum of two directors’ approval was needed to transfer legal title in shares to a new recipient.

Equitable title had not been transferred either. Briggs J analysed the judgment of Arden LJ in Pennington v Waine as stating that equitable title could be transferred on one of three occasions:

[a] the principle in Re Rose: where the donor had done everything necessary to transfer title to the donee so that further assistance of the donor to perfect the transfer was not needed;

[b] where the donee had undertaken an act of detrimental reliance, so that it could be said that the donor’s conscience was affected and a constructive trust could be imposed. Briggs J held that this category is what the facts of Pennington v Waine seemed to fall into; and

[c] where ‘by a benevolent construction an effective gift or implied declaration of trust may be teased out of the words used’.33This is the category that Briggs J held that the decision of the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini fell into.

It could not be said that categories (i) or (iii) applied to the transfer of shares here. In terms of category (i), the critical stock transfer forms transferring the titles to either recipient were omitted at the time the transfer of the shares purportedly took place. Briggs J did not feel that any ‘benevolent construction’ could be applied in Henry’s favour here, presumably because of his alleged motivation for the transfer of the shares at least to his wife. Category (ii) could not be relied upon by either Alice or Anucha because neither of them had undertaken any reliance on the purported transfer of the shares to themselves. As such, the equitable interests in the shares had not been transferred to Alice or Anucha.

It seems that Briggs J felt that the decision in Pennington v Waine had to fall into the ‘detri-mental reliance’ category largely because it did not fall into either of the other categories he listed. But it is hard to see how Harold relied to his detriment in the earlier case. Whilst it might be said that Harold may well have been happy to receive notification that he was to receive a gift of shares from his aunt, it is hard to see how he relied on such a letter to his detriment.

It is, therefore, interesting to note that Briggs J felt that he could not see that:

the existing rules about the circumstances when equity will and will not perfect an apparently imperfect gift of shares serve any clearly identifiable or rational policy objective.34

He also felt that this area of law might need to be examined further by a higher court.

Briggs J’s analysis of Pennington v Waine is interesting, as it confirms the case as equity preparing to intervene to perfect an imperfect gift on the basis of detrimental reliance. He was clear that the decision in Pennington v Waine led to an entirely separate method of equity perfecting an imperfect gift than had been allowed by the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini.

Do you think Arden LJ in Pennington v Waine would have regarded her judgment as developing an entirely separate method of perfecting an imperfect gift to that set out by the Privy Council in T Choithram International SA v Pagarini? Or do you think her judgment merely applies the principle from T Choithram International SA v Pagarini?

Summary of when a gift will be perfect

There have been significant inroads made to the original principle in Milroy v Lord that ‘everything necessary’ must be done to perfect a gift or constitute a trust. The test is based on the idea that if it would be unconscionable for the donor to recall the gift, the gift is perfect. The donor will hold the gift as a constructive trustee for the donee. Using the fundamental equitable doctrine of unconscionability (as occurred in Pennington v Waine) may accord with basic notions of equitable justice and fairness but does little to create the certainty afforded by the decision in Milroy v Lord. It rails against the two equitable maxims that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift or assist a volunteer and it must be asked to what extent those two maxims now have any application in relation to the constitution of a trust. The key case law in this area is summarised in Figure 7.2.

How a Trust is Completely Constituted

A trust may be constituted in either of the two ways described by Arden LJ in Pennington v Waine and illustrated in Figure 7.1. They are:

[a] transfer oflegal ownership in the trust property to a trustee; or

[b] retention of the legal ownership in the trust property by the settlor where the settlor declares that he himself is the trustee.

The aim of either method is to help establish the trust properly. If complied with, both methods provide that the beneficiary should have the benefit of an equitable interest in the trust property and that the trustee should administer the trust in the beneficiary’s favour.

Each method must be considered in turn.

Transfer of legal ownership to a trustee

Normally this should be a straightforward transaction between the settlor and trustee. If there are any formalities to be observed in the transfer of a particular type of trust property, then they must be complied with. For example, if the trust property is land, s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 provides that any declaration of trust of land must be in writing and signed by a person able to declare the trust, who will normally be the settlor. If the trust property is shares, they must be transferred using a stock transfer form. 35 If the property is a chattel, delivery of that chattel must be undertaken.

The key, however, is that legal title to the trust property must be vested in the trustee. Again, the equitable maxims that equity will not assist a volunteer and will not perfect an imperfect gift underpin this area.

There are three ways in which the legal title may be vested in the trustee which may be seen to be out of the ordinary. Provided, however, that the trustee receives the legal title to the trust property, the trust will still be constituted. It does not matter, therefore, that these ways look, at first glance, a little out of the ordinary. These three ways are:

[a] where the trust property is vested in the trustee by circumstance;

[b] the rule in Strong v Bird;36

[c] the doctrine of donatio mortis causa.

It is only in (c) that equity really does perfect the imperfect gift. As will be seen, in the first two situations, the courts have argued in successive decisions that the gift has already been perfected so that there is no need for equity to intervene.

Where the trust property is vested in the trustee by circumstance

It seems not to matter how the trust property gets to the trustee, provided that the legal title to the property is actually vested in him, as the facts in Re Ralli’s Will Trusts 37 illustrate. A family tree of the relevant parties in Re Ralli’s Will Trusts is set out in Figure 7.3 below.

Mr Ralli left his residuary estate on trust with a life interest for his wife and remainder in equal shares to his two daughters, Helen and Irene. Irene’s husband, Pandia Calvocoressi, was appointed as a trustee of that trust.

Separately, just before she married, Helen declared a trust in which she was to have a life interest with remainder to any children she might have or, in default, to Irene’s children. She promised to transfer any property she might acquire above the value of £500 to that trust. Pandia Calvocoressi was one of the trustees of the trust.

Helen died in 1956, followed by Mr Ralli’s widow four years later. Pandia Calvocoressi brought an action for directions in the High Court. Certain investments, representing Helen’s share of Mr Ralli’s estate, had matured. The question was whether the money should be held on Helen’s trust, or whether the money fell outside that trust and should be given to Helen’s personal representatives for them to administer on behalf of her estate. Helen had never transferred her residuary interest in her father’s trust to her trustees; instead, all she had done was promise to transfer the property to them. The beneficiaries under the trust were, of course, mere volunteers.

Buckley J held that the money belonged to the beneficiaries under Helen’s trust, not to the beneficiaries of Helen’s estate. The money had originally come from the estate of Mr Ralli. The legal ownership of the money had been vested in Pandia Calvocoressi as personal representa-tive for Mr Ralli. It did not matter that he may have held the money originally in his capacity as personal representative for Mr Ralli as opposed to his other capacity as trustee of Helen’s trust. All that mattered was that Mr Calvocoressi had legal title to the money: ‘[h]e is at law the owner of the fund, and the means by which he became so have no effect upon the quality of his legal ownership.’38

In this manner, legal ownership of the fund had been transferred to Mr Calvocoressi. He could now hold the money on trust for the beneficiaries of Helen’s trust.

Buckley J did not believe that his decision meant that equity was assisting volunteers. Equity was not intervening. The beneficiaries under Helen’s trust were entitled to the money as of right in equity because their trustee enjoyed the legal interest as the money had been vested in him.

Re Ralli’s Will Trusts illustrates that it is really a matter of fact whether the trustee has the legal ownership of the trust property. As long as he does, the trust is constituted. Even if he holds the legal title by accident, that seems not to matter. The fact that the legal title in the trust property had been transferred was in issue here; not the motive that may have led to the change of ownership.

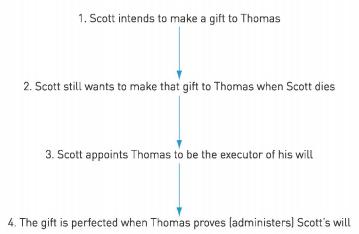

The rule in Strong v Bird39

The rule in Strong v Bird was summed up by Young CJ in the Australian case of Blackett v Darcy40 as:

if a testator intends to make a gift but does not make a complete gift before his or her death and still has the intention of making the gift at the time of death and appoints the donee as executor, then equity will assist the donee [in recognising the gift].41

This can be illustrated by the flowchart in Figure 7.4.

In Strong v Bird, the defendant lived with his stepmother in his house. She paid him £212 each quarter for her board and lodgings. He needed to borrow money so she lent him £1,100. She was to pay £100 less per quarter for her board and lodgings until the loan had been completely repaid. For the next two quarters following the making of the loan, the stepmother

paid £100 less from her board and lodgings money. Then she changed her mind and said that she would prefer to pay the full amount. The defendant accepted this. Four years later, the step-mother died, having continued to pay the full amount of her board and lodgings money. She appointed the defendant the sole executor of her will. The issue for the Court of Chancery was whether the defendant still owed the £900 to his step-mother’s estate.

Sir George Jessel MR held that the £900 debt was extinguished and that the defendant could retain the money. He relied on the old common law concept that the defendant in appointing the executor was, in this action, releasing him from the money owed. Equity would follow the law’s conclusion provided the defendant could show his step-mother had a ‘continuing intention to give’ the money to him which Jessel MR found that there was, on the facts of the case, by the stepmother always paying full board and lodgings to him.

Jessel MR did not believe this was a case of equity perfecting an imperfect gift:

the transaction is perfected, and he does not want the aid of a Court of Equity to carry it out, or make it complete, because it is complete already, and there is no equity against him to take the property away from him.42

Equity was not perfecting the gift. The gift was perfected by the process of the testator choosing the same person to be his executor as the donee of the gift and that same individual then proving the testator’s will. Legal title to the gift had been transferred by that process. As the gift is perfect, there was no remit for equity to interfere and take it away from the donee. But on the facts, it is surely the case that the defendant was a volunteer to the gift as he had not provided any consideration for his step-mother’s release of him from the debt he owed.43 The decision in the case, however, is probably right on its facts. Had the stepmother’s estate wanted to recover the £900, ultimately it would have had to sue for it. That would have meant the defendant — as her executor — suing himself, in his capacity of debtor. Such an action would have been absurd.

The rule in Strong v Bird has been considered in more recent cases such as in Re Ralli’s Will Trusts 44 and applied, somewhat reluctantly, by the decision of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in Blackett v Darcy45 where Young CJ said:

My view is that the rule in Strong v Bird should not in this 21st century be extended at all … I am bound to apply it, but as I say, it seems to me the prevailing view is that it is an anomalous rule and should not be extended.46

The rule was extended by the decision in Re James47 to apply to administrators as well as execu-tors. This was a strange extension of the rule. Any executor is deliberately chosen by the testator. It is this deliberate act of choice that helps to perfect the gift to the donee/executor. An administrator is someone appointed by the court to administer the estate of the deceased who has died without making a will (intestate). It is therefore good fortune if someone is appointed an administrator who also happens to owe money to the deceased. The act of the deceased deliberately choosing an individual to administer his estate is missing entirely if the deceased dies intestate. This point was made by Walton J in Re Gonin:48

It is often a matter of pure chance which of many persons equally entitled to a grant of letters of administration finally takes them out. Why, then, should any special tenderness be shown to a person so selected by law and not the will of the testator, and often indifferently selected among many with an equal claim?49

Walton J did, however, apply the rule leaving it to a higher court to address whether his doubts over the extension of the rule in Re James were well-founded or not.

Donatio mortis causa

This is the third example of how a trust may be constituted or a gift perfected in an unconven-tional manner.

Buckley J described donatio mortis causa as follows in Re Beaumont:50

It may be said to be of an amphibious nature, being a gift which is neither entirely inter vivos nor testamentary. It is an act inter vivos by which the donee is to have the absolute title to the subject of the gift not at once but if the donor dies.51

Here equity probably is perfecting an imperfect gift. The donor has made it clear to the donee that the property is to be his if the donor dies. The executor of the donor’s will becomes a trustee of the property for the donee. The donee merely has an equitable interest in the prop-erty whilst the donor’s executor holds the legal title on trust for the donee.

Three requirements for donatio mortis causa to apply were set out by Nourse LJ in Sen v Headley:52

First, the gift must be made in contemplation, although not necessarily in expecta-tion, of impending death. Secondly, the gift must be made upon the condition that it is to be absolute and perfected only on the donor’s death, being revocable until that event occurs and ineffective if it does not. Thirdly, there must be delivery of the subject matter of the gift, or the essential indicia of title thereto, which amounts to parting with dominion and not mere physical possession over the subject matter of the gift.53

The third requirement in Sen v Headley was not met on the facts of Re Beaumont itself.

Mr Beaumont was very ill and expected to die. He called his niece to his room and instructed her to write a cheque for £300 in favour of Mrs Ewbank. He duly signed the cheque but did so in shaky handwriting. The cheque was not cashed by Mr Beaumont’s bankers because the bank manager was not sure that the signature was genuine. He asked for evidence that it was. Before that evidence could be presented, Mr Beaumont died. The issue was whether the gift of the cheque to Mrs Ewbank was perfect.

Whilst it had been made in contemplation of death, the gift was held not to be perfect because it did not concern any property of the donor’s. A cheque could not be described as property as it did not pass any rights to the recipient. It was described by Buckley J as only a ‘revocable mandate’.54 Mr Beaumont could have changed his mind and stopped the cheque at any point during his lifetime. As such, he had not transferred any rights — legal or equitable — to Mrs Ewbank which she could enforce against Mr Beaumont’s executor after his death.

Donatio mortis causa is a doctrine which must be applied with care. If successful, it permits gifts to be made without the need to comply with s 9 of the Wills Act 1837. Section 9 provides, inter alia, that an individual’s will must be in writing, have been signed by the testator and the signature must be witnessed by at least two witnesses present at the same time as each other and the testator. These requirements are stringent because the testator is undertaking a process by which he is giving away all of his property. The process needs careful consideration by the testator and it must be clear that the testator was not unduly pressured into disposing of his property to recipients that he would rather not benefit. In addition, the testator must have mental capacity to write his will.

At first glance, donatio mortis causa appears to circumvent the requirements to create a valid will with ease. But the requirements of the Court of Appeal in Sen v Headley restrict it. At the same time, however, the decision also extended the doctrine to apply to land as well as personal property.

The facts concerned a house in Ealing, London, owned by Bob Hewitt. He had married but he and his wife had divorced. During their lengthy separation period, Mr Hewitt had lived with Mrs Sen, as man and wife, for 10 years. Whilst this ended in 1964, they continued to have a close relationship. In November 1986, Mr Hewitt was cared for in hospital and Mrs Sen visited him every day. Whilst he was there, he instructed her to bring him a set of his keys from his house. Unbeknownst to her, he put them into her handbag and she found them after his death. Shortly before he died, he had told her that she was to have the house and its contents. She was to find the deeds to the house in a steel box, the only key for which was on the key ring that he had put in her bag.

Mr Hewitt died intestate. Mrs Sen claimed that the doctrine of donatio mortis causa should apply to the gift of the house to her. The problem was that Mr Hewitt had not directly given Mrs Sen any property. He had not given her the title deeds to the house. Instead, he had simply given her the only key to the box in which the deeds were kept. At first instance, Mummery J held that that fact was fatal to Mrs Sen’s claim.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Nourse LJ did not doubt that Mr Hewitt had parted with dominion of the title deeds. The questions, he said, were whether in doing so, Mr Hewitt had parted with dominion of the house and whether land could pass by way of a donatio mortis causa.

Nourse LJ stressed that a parting of dominion was needed, not just a parting of possession of the property. Parting of dominion implied that the donor parted with control of the property, not just physical possession of it. Moreover, parting with dominion was different when dealing with tangible and intangible property. When dealing with intangible property, such as a chose in action, parting with the title document of the property would be sufficient to indicate a parting with dominion. Such was the case here. Mr Hewitt had parted with dominion of the title deeds to the house by giving Mrs Sen her own keys to the house and the only one to the steel box and in doing so, he had parted with dominion of the house.

Land could be the subject of a donatio mortis causa. There was no policy reason preventing this, according to Nourse LJ:

A donatio mortis causa of land is neither more nor less anomalous than any other. Every such gift is a circumvention of the Wills Act 1837. Why should the additional statutory formalities for the creation and transmission of interests in land [contained in sections 52 and 53 Law of Property Act 1925] be regarded as some larger obstacle?55

The issue of certainty in relation to wills fulfilling the requirements of s 9 of the Wills Act 183 7 or an inter vivos declaration of trust containing land complying with s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925 was not a vital consideration in the doctrine of donatio mortis causa as the doctrine was relied upon so infrequently. Mrs Sen could, therefore, enjoy the house under the doctrine.

The facts of Sen v Headley concerned unregistered land. The decision of the Court of Appeal is probably therefore confined to unregistered, as opposed to registered, land. As physical title documents (the Land Certificate) were abolished in registered land by the Land Registration Act 2002, do you think that registered land could be subject to a donatio mortis causa as there is nowadays nothing physically to hand over to a recipient?

Donatio mortis causa is really the only doctrine in which the courts acknowledge that equity does perfect an imperfect gift. Equity also assists a volunteer. As Nourse LJ stated in Sen v Headley, the doctrine is ‘anomalous’ to those equitable maxims. In all other instances, the courts regard gifts as already perfected by the donor and there is no need for equity to intervene to perfect them.

| |

Do you think the court is really only perfecting an imperfect gift and assisting a volunteer where the doctrine of donatio mortis causa applies? Read again the sections on where the trustee simply happens to become the legal owner of the property through circumstance and the rule in Strong v Bird. Do you think the court may be perfecting imperfect gifts and assisting volunteers in both of those situations?

Retention of the legal ownership in the trust property where the settlor declares that he himself is the trustee

This was the second way in which Arden LJ described that a trust may be constituted in Pennington v Waine. The settlor changes hats to become the trustee. He assumes the duties, rights and obligations of a trustee. Whilst he will always remain the settlor of the trust, from this point going forwards, he is the trustee. Obviously, there is no transfer of legal title in the trust property: it remains with the one and same person.

Perhaps the best way of the settlor declaring himself to be a trustee and constitute the trust is to execute a written document, regardless of whether a written document is actually required as a matter of law. This brings certainty to the transaction and it is not only clear that the settlor is now the trustee of the trust, but also when he assumed the duties, rights and obligations of being a trustee.

In normal life, however, many trusts are declared informally by both individuals and businesses.

Self-declaration by an individual

Equity will recognise an individual declaring themselves to be a trustee. This occurred in Paul v Constance.56

Doreen Paul and Dennis Constance were in a relationship together. They were embarrassed to open a bank account in joint names as they were not married. The bank opened the account in Dennis’ name alone. Doreen could still withdraw from the account provided she showed the bank staff a note of authorisation from Dennis. They paid what they regarded as money belonging to both of them into the account and also made withdrawals for both their benefits.

Dennis had been married to, and was not divorced from, Bridget before meeting Doreen. Dennis died intestate so his widow, Bridget, was responsible for administering his estate. Bridget claimed that, as the bank account was in Dennis’ sole name, the entire contents of it belonged solely to him. That money, she argued, became part of Dennis’ estate which she was bound to administer according to the laws of intestacy, as opposed to any of it belonging to Doreen.

Doreen disagreed. She argued that whilst the legal title of the money had been in Dennis’ sole name, a trust had been created of it with her and Dennis owning the beneficial interests.

The Court of Appeal upheld the trial judge’s finding that there was an express selfdeclaration of trust by Dennis in favour of both himself and Doreen. Dennis had then held the trust property (the money) as trustee on trust for himself and Doreen. In his judgment, Scarman LJ pointed out that:

one should consider the various things that were said and done by the [claimant] and the deceased during their time together against their own background and in their own circumstances.57

Certain facts led to the conclusion that Dennis had orally declared an express trust. The key fact was that Dennis had said to Doreen on more than one occasion ‘This money is as much yours as mine’.

Equity will look at all the circumstances of each case to decide if the settlor has declared himself to be a trustee. There must be sufficient evidence of a self-declaration of trusteeship and there are limits to how informal a declaration of trust can be. This was illustrated in Jones Lock.58

The case concerned a businessman who, after being admonished by his son’s nanny for failing to bring his son a present from his business trip said, ‘Look you here, I give this [cheque for £900] to baby; it is for himself, and I am going to put it away for him ….’. He then placed the cheque in his safe.

The issue was whether these words could be seen to be a declaration of himself as a trustee. The court held the words were not sufficient to declare the businessman a trustee of the money. The words were, according to Lord Cranworth LC, simply a ‘loose conversation’ 59 that the businessman had had with his son’s nanny.

Jones v Lock can be said to be authority for the proposition that the court will not treat a failed gift as a declaration of trust. Look back again at the facts of Re Rose. Did the Court of Appeal not treat a failed gift as a valid declaration of trust in that case?

Declaring oneself to be a trustee means that one retains no equitable rights in the trust property. The legal right in the trust property is retained, but the equitable interest is held on trust for the new beneficiary. The court has to be absolutely sure that there was a true declaration of trust: that the settlor truly intended to give away all the equitable interest he enjoyed in the property for the benefit of another. This was not the position in Jones v Lock: it could not be said that the father intended to assume all of the duties and responsibilities of a trustee.

Self-declaration by a business

Equity will recognise a declaration by a business that it now holds property on trust even if that trust is declared informally. This was illustrated in Barclays Bank Ltd v Quistclose Investments Ltd.60

The facts concerned a company called Rolls Razor Ltd that was in financial difficulties. It approached Quistclose Investments Ltd for a loan that it could use to pay dividends to its shareholders. Quistclose agreed to make the loan, but only on the basis that the money had to be used for the payment of Rolls Razor’s dividends. It then sent Rolls Razor a cheque representing the loan money. Rolls Razor duly paid the cheque into its bank, Barclays. Barclays was aware that the money was only to be used for one specific purpose. Before Rolls Razor could use the money to pay the dividends, it became insolvent. Barclays sought to use the money located in Rolls Razor’s account in part payment of Rolls Razor’s overdraft. Quistclose objected, arguing that Rolls Razor had declared itself to be a trustee of the money, with Quistclose as the beneficiary. The trust was declared by Rolls Razor making the purpose of the loan money clear to Barclays when the cheque was paid into its account.

In the House of Lords, Lord Wilberforce held that there were two types of trust on the facts. The ‘primary’ express trust arose in favour of the shareholders to whom the dividends were due. This trust had failed, as Rolls Razor had not paid the shareholders before it went insolvent. Consequently, a ‘secondary’ trust applied, which was a resulting trust of the money in favour of Quistclose.

The Quistclose decision was analysed by Lord Millett in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley.61 The facts concerned a loan of £1 million from Twinsectra Ltd for the purposes of enabling an entrepreneur, Mr Yardley, to purchase land in the Midlands. Mr Yardley was dealing with two solicitors, unconnected to each other, in relation to the loan. He first instructed a solicitor called Mr Leach but, during the transaction, approached a second solicitor, Mr Sims, to act on his behalf. Mr Sims was also a business associate of his. The money was advanced to Mr Sims, who transferred it to Mr Leach. Part of the money was in fact used to buy property but a substantial amount (over £357,000) was not. Twinsectra brought proceedings to recover that sum from Mr Leach. Their argument was that a Quistclose trust had been created when they advanced the money to Mr Sims. They had made it clear that the money was only to be advanced for the purpose of enabling MrYardley to buy property. When that purpose was not fulfilled, following Quistclose, the money should be returned to them.

The House of Lords held that a Quistclose trust had, indeed, been created.

Lord Millett pointed out that a court would not hold that there was a self-declaration of trust in every case where money was advanced for a particular purpose. Lenders were often interested in knowing the purpose of a loan simply to decide whether they should take a commercial risk in lending the money. Indeed, the general rule was that money lent to a borrower was free from a trust and it was at the borrower’s discretion to do with the money as he wished. To ascertain if there had been a self-declaration of trust by the lender, ‘[t]he question in every case is whether the parties intended the money to be at the free disposal of the recipient.… .’62

There was clear evidence here that the money was not to be at the free disposal of Mr Sims. Twinsectra had made it clear that the money was only to be used for purchasing property. Equity would recognise the trust because, according to Lord Millett: ‘[i]t is unconscionable for a man to obtain money on terms as to its application and then disregard the terms on which he received it.’63

Twinsectra had, therefore, created a trust with itself as the beneficiary.

Lord Millett then went on to explain the true nature of the Quistclose trust and where the equitable interest lay while the purpose of the trust is being put into effect. He said that there were ‘formidable difficulties’64 in holding that there were two successive trusts in Quistclose. For example, there was no clear answer to the question of what would happen to the equitable interest in the trust property if the primary trust was for a purpose and that purpose failed. He thought there were four possibilities as to where the equitable interest may be. These are set out in Figure 7.5.

Lord Millett rejected the idea that the equitable interest had passed to the borrower. If the borrower had the equitable interest as well as the legal title to the money, they would have

absolute ownership of it and would be able to use the money as they wished. This was plainly not the case in such arrangements: the borrower is able to use the money only for the purposes expressly stated by the lender. The money would also be part of the borrower’s estate if the borrower became insolvent. The arrangement between the borrower and lender was designed to protect the lender from this risk.

The equitable interest could not have passed to the contemplated beneficiary. The facts of Twinsectra showed that such a possibility was not capable of being fulfilled. The details of the trust were too imprecise to pinpoint quite who was to benefit from this particular trust, so: ‘[i]t is simply not possible to hold money on trust to acquire unspecified property from an unspecified vendor at an unspecified time.’65

The equitable interest could not be held in suspense. Lord Millett said that such an assertion failed to take into account the role of the resulting trust. The main task of the resulting trust was to fill in a gap in beneficial ownership. This meant that equitable interests could not be suspended.

Instead, Lord Millett held that the equitable interest remained throughout with the lender. That was the reason why the lender could enforce the trust. He said:

As Sherlock Holmes reminded Dr Watson, when you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. I would reject all the alternative analyses, which I find unconvincing for the reasons I have endeavoured to explain, and hold the Quistclose trust to be an entirely orthodox example of the kind of default trust known as a resulting trust. The lender pays the money to the borrower by way of loan, but he does not part with the entire beneficial interest in the money, and in so far as he does not it is held on a resulting trust for the lender from the outset.66

The borrower was under a duty to use the money according to the lender’s wishes. If that purpose failed, the money had to be returned to the lender.

In the Quistclose arrangement, then, there was only one trust: a resulting trust in the lender’s favour. Within the trust, the borrower enjoys a power to apply the money for a particular purpose.

As we have seen, it is possible for there to be a self-declaration of trust by both an individual and a business. The courts are cautious about holding that a declaration of trust has occurred, especially where money has been advanced. The courts’ inclination is to state that legal and equitable interests in the money have been transferred by way of a gift to the recip-ient, rather than a trust created. If, however, the evidence clearly points to a trust being created, it will be recognised.

Points to Review

You have seen that:

![]() to be properly formed, an express trust must be (a) constituted and (b) declared. In its most basic form, constituting the trust means the settlor either transferring the property to the trustee or the settlor himself holding the property on trust for the beneficiary;

to be properly formed, an express trust must be (a) constituted and (b) declared. In its most basic form, constituting the trust means the settlor either transferring the property to the trustee or the settlor himself holding the property on trust for the beneficiary;

![]() constitution of a trust revolves around the two equitable maxims that equity will not assist a volunteer and that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift; and

constitution of a trust revolves around the two equitable maxims that equity will not assist a volunteer and that equity will not perfect an imperfect gift; and

![]() the two key issues are when and how a trust is properly constituted. For the former, the courts have moved from a narrow interpretation of the settlor having to do ‘everything necessary’ (Milroy v Lord) to a looser, more flexible (but less certain) test of whether it would be ‘unconscionable’ for the court to deny the beneficiary’s interest (Pennington v Waine). The question now is to what extent the equitable maxims survive in relation to when a trust is constituted. For the latter, the courts will recognise both formal and informal ways of self-declarations of trust, in both business and non-business scenarios.

the two key issues are when and how a trust is properly constituted. For the former, the courts have moved from a narrow interpretation of the settlor having to do ‘everything necessary’ (Milroy v Lord) to a looser, more flexible (but less certain) test of whether it would be ‘unconscionable’ for the court to deny the beneficiary’s interest (Pennington v Waine). The question now is to what extent the equitable maxims survive in relation to when a trust is constituted. For the latter, the courts will recognise both formal and informal ways of self-declarations of trust, in both business and non-business scenarios.

Making connections

This chapter considered when and how a trust may be constituted. Constitution is one of the two essential ingredients in forming an express trust. The other essential ingredient is that the settlor must declare the trust. Declaration involves the settlor having capacity, complying with any necessary formalities, adhering to the three certainties, fulfilling the beneficiary principle and ensuring that the trust meets the requirements of the rules against perpetuity. These requirements are discussed in Chapters 4 to 6 (together with the chapter on perpetuities on the companion website). If you are unsure about any of these requirements, you should re-read those respective chapters.