Chapter 4

Trust Formation: Capacity and Formalities

Chapter Contents

The Fundamental Requirements Needed To Form an Express Trust

Formality Requirements on the Declaration of a Trust

Formality Requirements on the Disposition of an Equitable Interest

This, together with the next three chapters, considers arguably the most fundamental part of trusts law: how to form an express trust. It is essential that you grasp how the requirements to form an express trust operate as this is key to understanding this most vital area.

As You Read

In this chapter, you start to consider how the most widely used type of trust, the express trust, is formed. The express trust is a like a jigsaw: only when all of the pieces of the jigsaw are placed together will you see the main picture. It will take until (and including) Chapter 7 to understand how each component part of the express trust comes together. Here, look out for:

![]() the fundamental requirements to form an express trust. An understanding of these component parts is essential;

the fundamental requirements to form an express trust. An understanding of these component parts is essential;

![]() capacity: who can declare a trust, who may be trustees and who can benefit from a trust; and

capacity: who can declare a trust, who may be trustees and who can benefit from a trust; and

![]() formalities: how, in some types of trust, the law imposes formal requirements if the declaration of trust is going to be enforceable.

formalities: how, in some types of trust, the law imposes formal requirements if the declaration of trust is going to be enforceable.

The Fundamental Requirements Needed to Form an Express Trust

The nature of an express trust was discussed in Chapter 2.

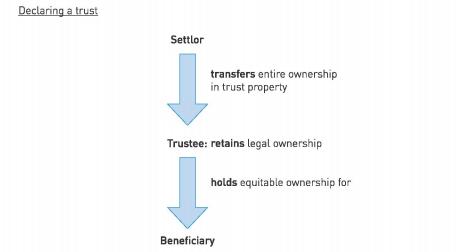

The diagram showing how an express trust is formed is set out below, in Figure 4.1.

The diagram at Figure 4.1 is a straightforward illustration of how an express trust is formed. The key transactions in the diagram need to be examined.

The settlor transfers the entire ownership in the trust property to a trustee

This part of the setting up of the express trust can be broken down into two critical stages, in which the settlor:

[a] declares the express trust; and

[b] constitutes the express trust.

Both stages need to be done properly if a valid express trust is created. Again, both stages have several parts to them. When the settlor declares an express trust, they need to adhere to four requirements. The express trust must comply with:

![]() formal requirements;

formal requirements;

![]() the three certainties;

the three certainties;

![]() the beneficiary principle; and

the beneficiary principle; and

![]() the rules against perpetuity.

the rules against perpetuity.

Formal requirements

The formal requirements needed for a trust depend upon the type of property which is to be the subject matter of the trust. To take the following examples:

[a] if the trust property is a chattel, that chattel needs to be delivered to the trustee and there must be an intention by the settlor to give the chattel to him;

[b] in the case of shares, any shares must be transferred to the trustee by making use of a Stock Transfer Form;1 and

[c] if the trust property is land, the terms of the trust must be evidenced in writing and declared by some person able to declare the trust.2 This requirement is considered later in this chapter.

The three certainties

It must be clear that there is certainty that the settlor intended to create a trust rather than simply intending to give the property away to someone. This is known as ‘certainty of intention’. It must also be certain what the subject matter of the trust is, or in other words, precisely what property the settlor placed on trust. Finally, the requirements of certainty mean that it must be possible to say who is going to benefit from the trust or, in legal parlance, certainty of object must be present. These certainty requirements are known as ‘the three certainties’. They are considered in detail in Chapter 5. As we shall see, the requirements of certainty are largely present to help the trustees administer the trust. The trustees must be able to be sure that the settlor intended to create a trust, what property the settlor expected his trustees to administer for the beneficiaries and lastly, who the beneficiaries are who will benefit from the trust.

The beneficiary principle

This principle requires that trusts in English law should usually be established for the benefit of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries. This means that they have already been identified, or are capable of being identified, as individuals or as being a member of a class of persons. In practical terms, this means that a trust should normally benefit an individual or individuals. Sometimes a trust may benefit a company because, in law, a company is generally seen to be a legal individual. A trust cannot normally be set up for a purpose, as opposed to an individual. Trusts for purposes generally do not comply with the beneficiary principle and will be void. There are exceptions to this requirement to have an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary and these exceptions are considered, along with the beneficiary principle itself, in more detail in Chapter 6.

The rules against perpetuity

These are three rules which exist to ensure that a trust will start and come to an end at some point in the future. It is generally thought to be a bad thing to allow a trust to last forever. In the past, trusts were often used to manage property (usually vast estates of land) for wealthy families. The intention behind such trusts was to ensure the land remained in the same family. The danger with this intention is that, if this practice were widespread, it would be difficult for property to circulate freely in the economy. In a market economy, it is important that all types of property, both land and personal property, are allowed to be bought and sold easily and that there are as few restrictions on this ability to buy and sell as possible. The rules against perpetuity are considered in a chapter on the companion website.

Provided the settlor meets these four requirements, the express trust will have been declared successfully.

The settlor then needs to go on to ensure the trust is constituted. In theory, this is a relatively simple requirement. It means that the property of the trust must be properly transferred to the trustee. Constitution of a trust is needed so that the ownership of the trust property can be placed with the trustee and then the trustee can start to hold the equitable interest in the property on behalf of the beneficiary. Without transferring the property to the trustee, there can be no constitution, since the trustee would not own any property to administer on behalf of the beneficiary.

Of course, nowadays most express trusts are professionally drawn up by solicitors or accountants. This means that the requirements that the trust is properly declared and constituted should all be capable of being met in a document drawn up by the adviser. For such professionally drawn-up trusts, it is artificial to see the stages needed to declare a trust as coming one after the other: in truth, all the requirements to declare the trust and constitute it will be recorded in the same document. Nevertheless, to understand how such a modern trust may be drawn up, it is important to break down the separate requirements of declaring and constituting a trust and examine them in depth in the following chapters. The following four chapters, then, are all connected with this central theme of forming an express trust.

The trustee holds the property on behalf of the beneficiary

Once the trust has been validly declared and constituted by the settlor, it is ready to be used. That means that the trustee is subject to a number of duties and obligations, but enjoys some rights too in terms of administering the trust. The duties that the trustees are under, together with the rights that they enjoy, can be found in Chapters 8 and 9.

Correspondingly, as soon as the trustee holds the equitable ownership in the property for the beneficiary, the beneficiary can, provided his interest is vested, start to enjoy the property. If he is only entitled to enjoy the property for his lifetime, he is said to have a ‘life interest’ and can enjoy just the income from it. If, on the other hand, the beneficiary is entitled to enjoy the trust property entirely, he is said to have an ‘absolute interest’ in the property and can benefit from both the income from the trust property and enjoy the proceeds from its capital too.

This begs the question: what type(s) of property can be left on trust?

Trust Property

Figure 4.1 illustrates the settlor transferring trust property to the trustee to hold on trust for the beneficiary’s enjoyment.

An express trust can be declared of virtually any property in which the settlor holds a legal interest. As mentioned, from the advent of trusts being first used, often trust property would amount to land. Wealthy families have made use of the trust for centuries as an attempt to ensure that land remained in their hands. But trusts do not have to have land as their property. ‘Trust property’ is used in a very wide sense.

Trust property may, for example, include the following, as well as land:

[a] Chattels. Sometimes these are known as ‘choses in possession’. They can be taken into the possession of someone or they are capable of being possessed. They are items which are not fixed to a piece of land, but are instead independent. In other legal systems, such as in France, they are known as ‘movables’ precisely because they can be moved about rather than being immovable, like land. This book that you are currently reading is a chattel, as is the chair upon which you are sitting to read it. If something is affixed to the land with the intention that it enhances the land, it ceases to be a chattel. For example, the washbasin and bath in your bathroom would not be seen as chattels since they are fixed to the land with the objective of enhancing the land.

[b] Money. Often trusts are set up with just money as their property.

[c] Choses in action. These are things which are dependent on the holder of them taking legal enforcement action (as opposed merely to taking physical possession of them) in order to obtain the rights associated with them. For instance, a share in a company is a chose in action. To obtain the money that it is worth, you would have to take legal action against the company and the company would pay you the value of it. The share certificate that you may have in your possession is merely evidence that you own a certain share in the company. Another example of a chose in action would be an insurance policy. Again, you would need ultimately to take legal action against the insurance company to enforce it.

All of these types of property are forms of ‘personal’ property, or ‘personalty’, so called because the rights in the property are enjoyed personally by the owner. The other type of property is known as ‘real’ property, or ‘realty’, which consists only of freehold land. This is called real property because the rights in it are real — they are rights that are enjoyed in the property itself, as against the whole world.

Often the property of a trust will be a mixture of all these different types of property. It is important to understand that not every trust will have land as its property.

Suppose Scott writes his will. He appoints Thomas and Vikas to be his trustees and provides that they are to hold on trust:

![]() his gold watch for his cousin, Amy;

his gold watch for his cousin, Amy;

![]() all of his shares in British Airways plc for his sister, Bethany;

all of his shares in British Airways plc for his sister, Bethany;

![]() £100,000 in his bank account for his son, Charlie; and

£100,000 in his bank account for his son, Charlie; and

![]() the house known as 4 Barlow Close, Derby, for his wife, Deborah.

the house known as 4 Barlow Close, Derby, for his wife, Deborah.

These are examples of Scott declaring four express trusts: one in favour of each of the four beneficiaries. Providing the four requirements for a valid declaration are fulfilled, constitution of the trust will occur after Scott’s death. Each of the four trusts has a different type of property. Only the final one has land as its trust property.

Capacity

It must be asked whether anyone can declare a trust, whether anyone can administer a trust and whether anyone can benefit from a trust. The capacity of each of the three main parties to an express trust — the settlor, the trustee and the beneficiary — must be examined.

The issue of capacity focuses on two concerns: whether the person under consideration has to be a particular age and whether the person must have mental stability in order to have capacity.

Capacity of the settlor

The general principle is that anyone can be a settlor of a trust and thus create a trust, provided they are at least 18 years old and are not mentally incapable. Of course, the settlor must own property and therefore must own the legal (or at least the equitable) interest in the property which they wish to settle on trust.

Children

It is possible for a child to settle personalty on trust. This trust is, however, voidable by the child, either before the child reaches 18 years old or within a reasonable time of reaching that age. This was shown in Edwards v Carter.3

Here, Albert Silber declared a trust in contemplation of a marriage between his son, Martin Silber and Lady Lucy Vaughan. The terms of the trust were that Albert was to pay the trustees the sum of £1,500 each year whilst Lady Lucy or any of their children were alive. The trustees were to pay that money, in turn, to Martin during his life and then, after his death or bankruptcy, to Lady Lucy and their children. The trust went on to say that if Albert left Martin further property under his (Albert’s) will, that property was to be held by the trustees in place of the annual sum of £1,500. This trust was declared by Albert whilst Martin was still a child. Approximately one month after the trust was declared, Martin became an adult.

The terms of the trust effectively gave Martin a life interest in the money only, with remainder to his wife and any children that they might have. It obviously also provided that any further property Martin might acquire from his father upon his father’s death was to be held on the same basis. Martin was, consequently, declaring a trust of property that he might acquire in the future.

Albert died in May 1887, nearly four years after declaring the trust. Martin attempted to repudiate the trust in July 1888 which, by then, was nearly five years after the trust had been declared.

The House of Lords held that Martin could not repudiate the trust. Whilst they affirmed the rule that a contract was voidable before a child reached 18 years old, or within a reasonable time of reaching 18 years old, their Lordships held that Martin had waited too long before repudiating the contract. Lord Watson explained the issue of repudiation as:

If he [the former child] chooses to be inactive, his opportunity passes away; if he chooses to be active, the law comes to his assistance.4

For our present purposes, the case illustrates that a child can be a settlor of a trust of personalty. The child also has the ability to repudiate the trust, either before he reaches 18, or within a reasonable time of reaching 18. What is a reasonable time will be a question of fact for the court to resolve: the House of Lords found it unnecessary in the case to set down what period of time was reasonable in every case.

A child cannot own the legal estate in realty. Under Sched 1, para 1 of the Trusts of Land and Appointment of Trustees Act 1996, any realty conveyed to a child will be held automatically on trust for them, so they will only be able to enjoy an equitable interest in the property. Since a child is himself a beneficiary of such a trust and is unable to deal with the legal estate in the realty, the most a child can do with realty is to declare a trust of their equitable interest.

Mentally incapacitated individuals

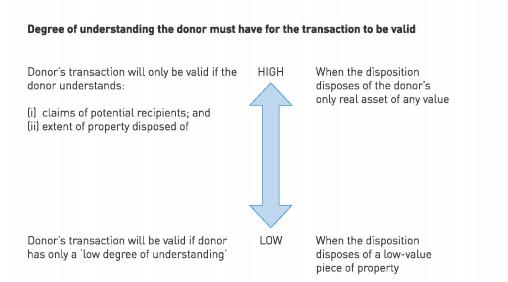

Whether or not a person suffering from mental capacity has the ability to declare a trust was considered in Re Beaney.5 The High Court held that whether a trust would be recognised depended on the size of the property being given away.

In the case, Mrs Maud Beaney owned her own home in Cranford, Middlesex. She had three children: Valerie (the eldest), Peter and Gillian. Mrs Beaney suffered from an ‘advanced state of senile dementia’6 from October 1972 until her death in 1974.

In May 1973, Mrs Beaney was admitted to hospital. Whilst there, Valerie claimed that her mother had decided to give her house to her. Valerie explained that this was in case the house needed to be sold at a future point to provide funds for the cost of her mother’s care. Valerie asked a solicitor to draw up a document, formally transferring the house into her name. The solicitor brought the document to Mrs Beaney and explained to her that if she signed it, its effect would be to give the house to Valerie absolutely. The solicitor asked Mrs Beaney twice whether she understood the nature of the document and on both occasions, Mrs Beaney confirmed that she did. The solicitor, Valerie and a third witness believed that Mrs Beaney understood what she was doing when she signed the transfer document.

After her death, Peter and Gillian argued that Mrs Beaney had lacked capacity to transfer the house to Valerie. They said that their mother was confused, as illustrated by her calling her family by incorrect names, having a tendency to get into the wrong bed whilst in hospital and by her handwriting being practically illegible. Valerie maintained that her mother did have capacity to transfer the house to her. She argued that the house was now hers, to the exclusion of Peter and Gillian.

Judge Martin Nourse QC held that the transfer of the property to Valerie was void due to a lack of capacity on Mrs Beaney’s part.

He said that there were different degrees of understanding required for lifetime transfers of property. The degree of understanding required was related to the actual transfer which was proposed. How much the individual transferring the property had to understand about the transaction varied depending on the value of the property being transferred and its relation to that individual’s other assets. He said:

at one extreme, if the subject matter and value of a gift are trivial in relation to the donor’s other assets a low degree of understanding will suffice. But, at the other extreme, if its effect is to dispose of the donor’s only asset of value and thus, for practical purposes, to pre-empt the devolution of his estate under his will or on his intestacy, then the degree of understanding required is as high as that required for a will …7

When writing a will, Martin Nourse QC reminded the court that the degree of understanding required was that the testator had to understand the claims of all potential recipients of his property and the extent of the property of which he was disposing. The requirements for understanding are summarised in Figure 4.2 below.

Applied to the facts here, Mrs Beaney was disposing of her home, which was her only real asset. The degree of understanding she needed to have for that transaction to be effective was as high as if she were writing her will. The reason for this was that she was effectively circumventing the need for a will, by divesting herself of her only real property by the transfer to her daughter. Mrs Beaney needed to understand first, that her other children might have at least moral claims to her home and second, that she was giving away her only real asset. She had effectively no other property of her own. The evidence of her confusion led to the conclusion that she could not have understood these two crucial issues. At best, the judge found that all she could have grasped was that the transfer had ‘something to do with the house’ and that the effect of it was ‘to do something which her daughter Valerie wanted’.8

Re Beaney was applied by the High Court in the more recent case of Re Sutton.9 This latter case illustrates how the test of whether the donor understands the nature of his gift is applied. Here, Norman and Rosalie Sutton lived in a bungalow in Tangmere, West Sussex. The house was in Norman’s sole name. He transferred it in August 1997 to his son, Mark, who later transferred it into his and his wife’s joint names. Norman and Rosalie continued to live in the bungalow. Norman died in 2005. Afterwards, Rosalie brought an action, claiming that the transfer of the house should be set aside. She argued that Norman lacked capacity when he signed the transfer.

The judge, Christopher Nugee QC, found that, unlike Mrs Beaney, the bungalow that was transferred was not Norman’s only real asset. He had several other investments. Yet the judge found that the house was his main asset. As such, the degree of understanding that Norman had to have to show capacity was a high one. It had to be shown that he understood not only the ‘general nature of the transaction but also the claims of other potential donees’.10

The judge pointed out that the burden of proof that a person lacked capacity lay with the person seeking to prove that the document was invalid. The evidence in this case was that Rosalie had to help Norman physically sign the document transferring the property to Mark. Mark admitted that he did not discuss the transaction with Norman and he was concerned that his father did not understand the effect of the document he was signing. Various entries from a diary kept by Rosalie confirmed Norman’s deteriorating mental health before and around the time that he signed the transfer document. A consultant neurologist’s view was that by the summer of 1997, Norman had significant cognitive decline which would have impaired his ability to understand a legal document and he did not believe that Norman would have had the high degree of understanding required from Re Beaney to ensure that the transfer he signed was valid.

Christopher Nugee QC accepted this evidence and held that Norman lacked capacity. In terms of the concrete proof that was needed for the transfer to have been valid, he said that Norman would have needed to understand that he was giving away the bungalow to Mark and that, as a consequence, neither he nor Rosalie would have had any right to remain in the house. To deprive himself and his wife of their matrimonial home was a serious consequence and, as such, Norman needed to demonstrate a high degree of understanding. The evidence showed that he did not have this.

The parties in the case not only wanted the judge to declare the transaction invalid but also that it was void.

Glossary: Void or Voidable?

If a document is void, that means that the document was never valid. It was of no effect at any time. Everything goes back to square one: it is as though there never was a transaction at all.

If, on the other hand, a document is voidable, this means that a document is valid, but that it may be set aside at the bequest of the innocent party. A good example occurs if the document was made as a result of a misrepresentation. The innocent recipient of the misrepresentation may well wish to have the document set aside — or, alternatively, they may be content to leave the document to have its normal legal effect. Such is possible if a document is voidable. ‘Voidable’ gives the innocent party some flexibility over whether they wish to rely on the document or not.

By the time of the hearing, Rosalie and Mark had been reconciled. The hearing was really about taxation and, in particular, the payment of capital gains tax.

Glossary: Capital Gains Tax

This tax is generally payable whenever an item is sold which has increased in value since it was purchased. A typical example might be a rare painting that was bought in 2000 for £1 million and is sold today for £3 million. Capital gains tax (CGT) is charged on the gain made — £2 million.

Reliefs exist and exemptions apply which mean that often no CGT is charged on everyday transactions. For instance, if a house is bought and then later sold, the principal private residence exemption will apply to the gain made. This means that no CGT is payable on the gain, provided that the owner used the house as his main residence whilst he owned it.

For more information on capital gains tax, see www.hmrc.gov.uk/cgt/.

Rosalie and Mark feared that if the transaction was held to be valid, Mark would have acquired the bungalow in 1997. That would mean that, by the hearing date in 2009, he would have owned the property during the 12 years in which house prices increased significantly. In turn, that would mean that he would have made a large gain on the property so that when he sold it, CGT would be due from him. He would not have been able to make use of the principal private residence exemption since he had remained living in his own house. If, on the other hand, the transaction could be declared void, then the property had never been transferred to him, he did not own it now and so he would not be liable for any CGT when the property was eventually sold.

The court in Re Beaney had seemingly declared the transaction void. But Christopher Nugee QC pointed out that the judge in the earlier case had emphasised that it made no difference on the facts whether the transaction was void or voidable. Re Beaaey could not be taken as authority that lack of capacity made a lifetime transfer void.

Christopher Nugee QC found that he did not need to express a decided view about whether the gift here by Norman to Mark was void or voidable. Such a declaration was only required by the parties in their efforts to avoid tax. Holding the transaction as invalid due to incapacity and that it should consequently be set aside was enough to dispose of the case. But he reviewed contradictory English and Australian authorities. He preferred the argument from the Australian courts11 that lack of capacity made the gift voidable, as opposed to void. Being an equitable issue, a gift being voidable would enable the doctrine of laches to be applied if the innocent party took too long to apply to the court for a declaration that the document was voidable.

Glossary: Laches

The doctrine of laches (delay) applies where an equitable remedy is sought. It may prevent the innocent party from seeking their remedy if they have delayed too long in applying for it, after their right to pursue their remedy has arisen. This principle is discussed further in Chapter 1 (under equitable maxim (vii) that delay defeates equities) and in Chapter 12.

If laches applied, gifts such as those made here could be kept alive, notwithstanding the lack of the donor’s capacity, because the donor failed to take action to set the gift aside within a reasonable period of time. Tantalisingly, by expressing no firm view, the High Court left this consequence open as a possibility if such gifts were seen to be voidable, as opposed to being void.

The usual practice, if possible, is to avoid scenarios such as those found in Re Beaney and Re Sutton. An alternative mechanism exists under the Mental Health Act 1983 where someone suffering from mental incapacity can place their affairs under the control of the Court of Protection. A disposition of their property then requires the court’s permission for that disposition to be valid. In that manner, a person suffering from mental incapacity may have their affairs controlled so that there will be no questions raised if dispositions do have the permission of that court.

Capacity of the trustee[s]

Generally, anyone can be a trustee of a trust provided they are 18 years of age or older and of sound mind. Section 34(2) of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that the maximum number of trustees of land at any one time is four. Where more than four people are named as trustees, the trustees will consist of the first four named only. As an exception, charitable or ecclesiastical trusts of land may have an unlimited number of trustees.12

Normally, it is good practice to have at least two trustees, so that one may both assist and keep a watchful eye over the other.

Having at least two trustees is useful if the trust property contains land. If the land is sold, the purchase money will be paid to the trustees and then the buyer can overreach the equitable interests of the beneficiaries under the trust.13 That means that the buyer will buy the land free from the trust, which is his objective. Overreaching the beneficial interests can only occur provided that there are at least two trustees of the trust or the trust is managed by a trust corporation.

Children as trustees

It appears that a child cannot be deliberately appointed to be a trustee, under s 20 of the Law of Property Act 1925. This section provides that:

The appointment of an infant to be a trustee in relation to any settlement or trust shall be void, but without prejudice to the power to appoint a new trustee to fill the vacancy.

This applies to all express trusts, regardless of the type of property left by the settlor on trust. The decision in Re Vinogradoff14 would seem to suggest, however, that a child can be a trustee of an implied trust.

Here, a grandmother decided to transfer War Loan shares into hers and her granddaughter’s joint names. Rather contradicting this transfer, the grandmother then purported to leave the same shares to another recipient in her will. After she died, the grandmother’s executors brought an action seeking to ascertain whether the granddaughter did have any interest in the shares. The court held that she enjoyed no equitable interest in the shares and instead, the granddaughter held the shares on resulting trust for the grandmother’s estate. The granddaughter was just four years old and must surely be one of the youngest trustees ever known.

Section 36 of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that a trustee who is an infant may be replaced as a trustee. For the draftsman of the Act to provide that an infant trustee is capable of being replaced confirms that it must be possible to have children as trustees. It appears, however, that the combined effect of this provision, s 20 of the Law of Property Act 1925 and Re Vinogradoff is that children can be trustees of implied trusts only and are liable to be replaced by adult trustees.

Trust corporations

The reasons why settlors place property on trust have changed over the centuries. In its original form, the use was probably a means by which paying tax could be avoided. The trust became a device in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries where this aim could still be achieved but could also be a mechanism for retaining property within the same family (subject to perpetuity requirements being met). More modern functions of the trust have been discussed in Chapter 2, but perhaps the general focus of the trust nowadays has reverted to its original function: to be used as a means of tax avoidance.

Due to this, it is becoming an increasingly common practice that settlors do not appoint individuals to manage trusts but instead use trust corporations.

Section 68(18) of the Trustee Act 1925 defines a ‘trust corporation’ as:

the Public Trustee or a corporation either appointed by the court in any particular case to be a trustee, or entitled by rules made under subsection (3) of section four of the Public Trustee Act, 1906, to act as custodian trustee …

In practice, trust deeds usually give a wider meaning to the term than the Trustee Act 1925. This means that trust corporations are generally large organisations such as banks, insurance companies and other financial institutions which are incorporated in the UK. Such organisations have specialist staff who invest in and manage property on a daily basis. The theory is a trust managed by such a trust corporation will be managed more effectively and, perhaps, more professionally than a trust managed by individual trustees who, despite being wellmeaning, may not naturally have the skills required to administer property for the benefit of others.

The appointment of a trust corporation to administer a trust has a convenient legal consequence if the trust wishes to dispose of property which is land. Section 14(2)(a) of the Trustee Act 1925 provides that a trust corporation, as a sole trustee, can give a valid receipt for the money arising from a sale of land. The beneficial interests under the trust are then overreached and the buyer of the land will take the land free from the trust. If individual trustees are appointed instead of a trust corporation, the same sub-section of the Act provides that the valid receipt is needed from at least two trustees in order that the beneficial interests under the trust are overreached.

It is possible to appoint a trust corporation to be a trustee alongside an individual or individuals. Due to the legal advantage of appointing a trust corporation in relation to the sale of trust property, however, such a dual appointment is rare.

Member-nominated trustees

The general rule is that anyone may be a trustee provided they are over 18 years of age and are of sound mind, so that they may hold property.

An exception exists in relation to occupational pension schemes. These are pension schemes which are established by employers to provide benefits to their employees when the employee retires. Benefits are usually paid to person(s) the employee chooses through a Letter of Wishes if the employee dies during the time he is a member of the scheme albeit that the trustees are not bound to follow the employee’s choice in the Letter of Wishes and may pay the proceeds to the employee’s personal representatives instead. Occupational pension schemes are a form of discretionary trust.

At least one-third of all of the trustees of an occupational pension scheme must be member-nominated, pursuant to s 241 of the Pensions Act 2004. This type of trustee must be appointed following a process of election in which the members of the scheme — both presently paying into the pension and those in retirement — may participate. Usually member-nominated trustees will be members of the pension scheme themselves. 15 Section 241(7) specifically states that member-nominated trustees enjoy exactly the same rights to manage the trust as the other trustees.

The requirement of occupational pension schemes to contain member-nominated trustees was as a result of the circumstances surrounding Robert Maxwell and the occupational pension scheme of the Daily Mirror newspaper.

Robert Maxwell was a publisher who owned the Mirror group of newspapers in the 1980s and early 1990s. He was found dead in the sea off the Canary Islands in November 1991, after which his media empire began to unravel. It appears that he took money (approximately £400 million) from the Daily Mirror’s occupational pension scheme to fund both his businesses and his own personal lifestyle. This resulted in the amount of money in the scheme being reduced and left some of his employees with a greatly reduced retirement provision.

As a result of this, member-nominated trustees were introduced to give members of occupational pension schemes a greater sense of security that their retirement funds were being protected by people who were in the same position as themselves — members of the scheme-and who would, therefore, have a natural interest in safeguarding and administering the trust.

Capacity of the beneficiaries

Anyone can be a beneficiary. This means that children can benefit from a trust, as can mentally incapacitated individuals. Even if the property of the trust is land, children are only prevented from holding a legal estate in land and not an equitable one.16 Companies may also benefit from a trust.

Having considered who create, administer and benefit from a trust, it is time now to turn to the first of the requirements that will be considered over the creation of an express trust: requirements as to formality.

Formalities

As a preliminary point, the difference between creating an express trust and assigning an equitable interest under a trust must be understood. That is illustrated in Figure 4.3 below.

Assigning an equitable interest, then, is an act undertaken by the beneficiary once the trust is in existence. The reason for drawing this distinction between the creation of a trust and the assignment of an equitable interest under a trust that already exists is because, generally speaking, there are no written formality requirements that must be fulfilled on the declaration of a trust, unless the trust property consists of land. There are, however, always requirements of formality 17 that must be met on the assignment of an equitable interest.

Formality Requirements on the Declaration of a Trust

The fundamental position is that there are no requirements of writing that a settlor must meet when he declares a trust. That means that a trust can be declared entirely orally. Provided the other requirements to declare an express trust are met (three certainties, beneficiary principle and the rules against perpetuity), then the trust will be effectively declared. Naturally, proving that an express trust which has been declared orally actually exists is a practical problem that a settlor would have to address if required but declaring a trust orally is legally possible.

Making connections

Think back to the facts of Paul v Constance,18 that was considered earlier in Chapter 2. Both the trial judge and the Court of Appeal had little difficulty in finding that Mr Constance had declared a trust orally of money in his bank account by the words ‘This money is as much yours as mine’. Mr Constance held the money as trustee on behalf of himself and Mrs Constance.

There is, however, an exception to the rule that there are no writing requirements to declare a valid trust. That is when all or part of the trust property is land. In that case, the Law of Property Act 1925 s 53(1)(b) provides:

a declaration of trust respecting any land or any interest therein must be manifested and proved by some writing signed by some person who is able to declare such trust or by his will …

This paragraph shows:

[a] the requirement that a declaration of trust should be in writing applies to any trust concerning land, no matter what tenure of land is at issue. In other words, the requirement of writing applies to both freehold and leasehold land that forms trust property;

[b] strictly, the exact terms of the trust need not be written down when the trust property concerns land. As more and more trusts are professionally drawn up nowadays, it will frequently be the case that the exact terms of the trust are written down in a formal document. That is not necessary to comply with the requirements of the Law of Property Act 1925. All that is needed is that the terms of the trust must be ‘proved’ or evidenced in writing. It is possible, for instance, that a trust of land could meet the requirements of the Act by having its main terms embodied in a simple note written by the settlor to the trustee. It would, for example, be possible for the settlor to write the terms of a trust on a ‘post-it’ note;

[c] the requirement that the terms of a trust concerning land must be written down applies to trusts declared both during the settlor’s lifetime and in his will. Of course, s 9 of the Wills Act 183 7 already imposes more strict requirements on the writing of a will, including the requirement that the signature of the testator is witnessed by at least two witnesses present at the same time as the testator. These stricter requirements of the Wills Act 1837 apply to a trust declared in a will; and

[d] if an express trust ofland is not evidenced in writing, it will be unenforceable as opposed to void. This effectively means that the trust does exist but the beneficiary is dependent on the trustee’s moral integrity to honour the terms of the trust. A court will generally not enforce an express trust of land which does not meet the requirements set out in this sub-section.

The Law of Property Act 1925 s 53(1)(b) applies only to a trust of land declared as an express trust. It does not apply to constructive or resulting trusts, even if they contain land as their property. This is set out in s 53(2), ‘[t]his section does not affect the creation or operation of resulting, implied or constructive trusts’.

This has the effect that all constructive and resulting trusts of land can still be valid without their terms being written down.

The effect of a trust involving land being declared only orally was considered in Rochefoucauld v Boustead.19

The facts concerned land owned in Sri Lanka by the Comtesse de la Rochefoucauld. The land was sold by the mortgagee (lender) to the defendant in 1873. The land was used for coffee production and, in the years following the sale, the defendant accounted to the Comtesse for some of the profits made from the coffee growing. The Comtesse’s claim was that the defendant owned the lands on trust for her, using this account of profits to her as evidence for her claim. The defendant went bankrupt in 1880. The defendant’s trustee in bankruptcy claimed the lands as belonging to the defendant absolutely, so that they could be used in order to pay the defendant’s creditors. The lands were sold. The Comtesse brought an action in 1894, claiming that the defendant owned the land on trust for her from when he bought them in 1873 and, as such, he now owned the proceeds of sale from the land for her in the same capacity. In response to her claim, the defendant argued that the land had been originally transferred to him as absolute owner and, in any event, the equivalent then of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 192520 applied to the claimant’s claim. This meant that any trust of the land would have been required to have been set out in writing and, since it was not, there could be no trust of the land in the claimant’s favour.

The Court of Appeal disagreed with the trial judge and held that there was an express trust in favour of the claimant. She had transferred the land to the defendant subject to the terms of a trust. In delivering the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Lindley LJ explained:

[a] section 7 of the Statute ofFrauds 1677 (the predecessor to s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925) did not require a trust to be declared in writing when it was first established by the settlor. It only required that the trust should be proved in writing by a written document signed by the settlor. Such a document could be dated at any time:21 it did not have to be contemporaneous with the date the trust was established;

[a] the requirement that the trust must be proved in writing could not outweigh a fraud. The requirement of writing would not be allowed to ‘trump’ the maxim that equity will not permit a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. The defendant could not, consequently, hide behind s 7 and argue that no written document meant the trust was invalid when he knew the land was transferred to him as a trustee. As Lindley LJ said:

Consequently, notwithstanding the statute, it is competent for a person claiming land conveyed to another to prove by parol (i.e. oral) evidence that it was so conveyed upon trust for the claimant, and that the grantee, knowing the facts, is denying the trust and relying upon the form of conveyance and the statute, in order to keep the land himself;22 and

[a] Letters written between the claimant and defendant could establish that a trust actually existed. Those would fulfil s 7. Once the actual existence of a trust had been established, the exact terms of it could be added to by the claimant’s oral evidence.

The principles which arise in this case are equally applicable to s 53(1)(b). Overall, the case illustrates the principle that equity will not permit someone to deny the existence of a trust just because the precise requirements of a statute have not been met.

The principle arising from Rochefoucauld v Boustead was taken one stage further in the decision of the High Court in Hodgson v Marks.23 Here, the beneficiary’s action was not against the actual person who had defrauded her, but against a third party. The High Court held that the principle in Rochefoucauld could still apply.

In this case, Mrs Beatrice Hodgson was an elderly widow who took a lodger, John Evans, into her home. It seems that Mr Evans was of a controlling nature, for example, following Mrs Hodgson when she went out shopping and also persuading her to give him, over time, her life savings for him to invest. Twelve months after taking him in, Mrs Hodgson trusted him so much that she transferred her home into his name. According to Mr Evans, this was done to allay his fear of Mrs Hodgson’s nephew from evicting Mr Evans from the house.

Mrs Hodgson believed that she had verbally agreed with Mr Evans that the house would continue to be hers, albeit registered at HM Land Registry in his name. Four years later, Mr Evans sold the house (allegedly with vacant possession) to Mr Marks. Mr Marks and Mrs Hodgson then slowly realised that each of them had competing claims in the house. Mr Marks’ view was that he had bought the property from the registered proprietor with vacant possession and he was entitled to it. Mrs Hodgson’s case was that she still owned the equitable interest under a trust. Her difficulty was that since this was a trust of land, s 53(1) (b) required the trust to be proved in writing and signed by some person able to declare the trust. There had, of course, been nothing written down by either her or Mr Evans to evidence the creation of a trust. She wanted a declaration from the court that Mr Marks was bound to transfer the house to her.

Ungoed-Thomas J found that Mrs Hodgson had transferred the house to Mr Evans but that she had never intended to make a gift of the property to him entirely and that she had always intended to retain the beneficial interest in the house. He held that Mr Evans possessed only the legal interest in the property for himself and that he held the equitable interest for Mrs Hodgson.

Counsel for Mr Marks had argued that the principle in Rochefoucauld v Boustead only applied where the individual who had caused the fraud was trying to deny the existence of a trust. That was not the position here. Here, it was not Mr Evans being subjected to the principle in Rochefoucauld v Boustead but instead a third party, Mr Marks. Mr Marks was an entirely innocent buyer of the house.

Ungoed-Thomas J rejected this submission. He said whoever relied on s 53(1)(b) to deny the existence of a trust in circumstances like those in the case was, by definition, using the statute as an instrument of fraud — they were using the statute to try to prevent any recognition of the trust. It was not necessary that that principle should be confined simply to those who had committed the fraud. Ungoed-Thomas J held that Mrs Hodgson’s oral evidence would be allowed to clarify the written conveyance of the house to Mr Evans because to exclude her oral evidence would be to hide behind the writing requirements of s 53(1)(b) and permit the statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. As Ungoed-Thomas J put it,24 ‘extrinsic evidence is always admissible of the true nature of any transaction’. His decision actually went further than that in Rochefoucauld v Boustead on this issue of the type of evidence needed to establish a trust. In Rochefoucauld, it was the letters written between the parties that were relied on primarily to establish the trust whereas in Hodgson v Marks, the verbal evidence of Mrs Hodgson was accepted on its own to create a trust.

The actual result in the High Court went against Mrs Hodgson, since it was held that she had failed to satisfy the requirements of being in ‘actual occupation’ of the property under the terms of s 70(1)(g) of the Land Registraton Act 1925. Her occupation of the property had not been apparent to Mr Marks when he had visited the property before he bought it. As such, she had no overriding interest to remain in the house. She appealed to the Court of Appeal.25

Mrs Hodgson was successful at the Court of Appeal. The decision of the Court largely rested upon the fact that she was in actual occupation of the property under s 70(1)(g) of the Land Registration Act 1925 and did enjoy an interest in the land which overrode that of the buyer, Mr Marks.

In delivering the only substantive opinion of the court, Russell LJ did not disagree with the trial judge that there was an express trust but offered alternative solutions:

[a] Since Mrs Hodgson never intended to give the house away to Mr Evans, he must have held it on trust for her. Instead of that being an express trust, it could be said to be an implied resulting trust. Section 53(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925 specifically states that resulting trusts of land do not have to be proved in writing. The oral evidence of Mrs Hodgson would be more than sufficient to establish a resulting trust of her home in her favour. If an attempted express trust had failed due to it not being evidenced in writing, that presented an opportunity for a resulting trust to apply; or

[b] A resulting trust might arise due to Mrs Hodgson never actually giving the equitable interest in her house away. There was therefore no ‘disposition’ of the equitable interest or any declaration of trust within the meaning of s 53(1)(b). Russell LJ merely offered this as a suggestion but declined to hold that it was directly applicable to the facts in the case.

Russell LJ did not answer the question as to whether the principle in Rochefoucauld v Boustead applied only to those in direct receipt of the property. Mr Marks did not, on the facts, know about Mrs Hodgson’s interest in the property and relying on s 53(1)(b) in such circumstances probably could not be seen to be acting fraudulently. As Russell LJ put it,26 ‘[q]uite plainly Mr Evans could not have placed any reliance on section 53, for that would have been to use the section as an instrument of fraud’.

No opinion was offered on whether a third party would, in theory, be prevented from relying on s 53(1)(b) to deny the existence of a trust if in fact they had knowledge of the trust.

Summary of the main principles of s 53(1)(b) of the Law of Property Act 1925

A trust with its property as land must, therefore, be proved in writing as a general rule, to comply with s 53(1)(b). There are exceptions to that principle:

[a] The principle in Rochefoucauld v Boustead applies the equitable maxim that equity will not permit a statute to be used as an instrument of fraud. It is submitted that this principle would extend to third parties, such as Mr Marks, if they had knowledge of the fraud which had been committed. The equitable maxim itself is phrased generally and there is nothing in it to limit it simply to those who have personally committed the fraud; and

[b] a trust ofland created by an implied (resulting or constructive) trust is not required to be evidenced in writing due to s 53(2) of the Law of Property Act 1925.

Formality Requirements on the Disposition of an Equitable Interest

Consider again the diagram showing the lifetime disposition of an equitable interest in Figure 4.3. The nature of this transaction, of course, is fundamentally different from the declaration of an express trust. An express trust may be declared orally unless, as we have seen, the trust property consists of land.

The requirements of the disposition of an equitable interest are more strict than declaring a trust. Any disposition of an equitable interest must be in writing, under s 53(1)(c) of the Law of Property Act 1925. This provides:

a disposition of an equitable interest or trust subsisting at the time of the disposition, must be in writing signed by the person disposing of the same, or by his agent thereunto lawfully authorised in writing or by will.

The important requirements of this paragraph are:

[a] Any disposition of an equitable interest has to be in writing. This is different from s 53(1) (b), where the declaration of a trust merely had to be proved in writing. This requirement enabled the trust in Rochefoucauld v Boustead to be established because there was enough to indicate the existence of a trust in letters passing between the parties in the case to meet the statutory requirement that the trust could be proved through writing. Yet under s 53(1)(c) the actual disposition itself must be in written form;

[b] The disposition of the equitable interest must be signed by the person disposing of it. Again, this is a more onerous requirement than in s 53(1)(b) where the writing required for a trust of land to be declared could be signed by ‘some person who is able to declare such trust’. Section 53(1)(b) does not necessarily mean that the settlor has to sign the written document declaring the trust; and

[c] When disposing of an equitable interest, the actual nature of the property which is the subject of that equitable interest is irrelevant. All dispositions of equitable interests in any type of property — not just land, as under s 53(1)(b) (regarding declaration of trusts) — must be in writing.

Once again, s 53(2) may ‘save’ some equitable dispositions if they have not been written down since that sub-section confirms that the requirements of s 53(1)(c) do not apply to the operation of resulting or constructive trusts. It is due to s 53(2) that there is cross-over between the case law which is considered under s 53(1)(c) and which has already been considered in the context of implied trusts in Chapter 3.

The policy reason underpinning s 53(1)(c) is that the trustees ought to know who owns the equitable interest in the trust property. If their task is to administer the trust, it is probably useful if they know for whom they are administering it! Requiring each disposition of an equitable interest to be in writing helps to keep a track of who owns the equitable interest which, in turn, assists the trustees in administering the trust. If the court has to step in to administer the trust because the trustees fail to do so, such evidence again is vital so that the court can see who the current beneficiaries are.

Most of the case law in this area is concerned with whether or not there has been a ‘disposition’ within s 53(1)(c). It is only if there has been a disposition of the equitable interest that the requirement of writing applies. It is clear that where a beneficiary transfers his equitable interest to another person directly, as shown in Figure 4.3, that will be a disposition of the equitable interest and it will only be valid if it has been written down. There are, however, variations on this straightforward transfer that have occurred and now need to be considered. The question is always whether what has been done amounts to a disposition.

Where the beneficiary asks the trustee to hold their equitable interest for another person

In this scenario, the beneficiary does not transfer their equitable interest directly to a recipient but instead asks the trustee to hold the equitable interest on trust for that other person. This situation is shown in Figure 4.4 below.

The literal view: Grey vInland Revenue Commissioners27

This situation arose in Grey v Inland Revenue Commissioners. The case concerned six trusts that Mr Hunter had declared. Five of the trusts were for the benefit of each of Mr Hunter’s grandchildren; the sixth was for the benefit of any grandchildren that might be born in the future. Some years after declaring the trusts, Mr Hunter transferred to the trustees 18,000 shares in a company. He then orally instructed the trustees to split the shares into six equal parts and to hold the shares on each of the six trusts that he had previously established. This verbal instruction was later confirmed in a document.

The Inland Revenue wanted stamp duty to be paid on the document confirming the transfer of the shares. They argued that the document effected the disposition of the shares from Mr Hunter to the trusts for his grandchildren. As the document operated in this way, stamp duty was payable on it.

Glossary: Stamp Duty

Stamp duty was a tax payable on documents which transferred land or shares. It was charged on the value of the transaction which the paper document effected. It was, for the vast majority of transactions, replaced on 1 December 2003 by Stamp Duty Land Tax for transfers of land and Stamp Duty Reserve Tax for shares purchased electronically. Stamp duty itself only exists nowadays for shares purchased using a paper form. Such instances will be rare. These changes were made due to the increasing use of electronic forms for the transfer of land and shares.

The trustees of the trusts argued that no stamp duty was due to the Inland Revenue because the document which Mr Hunter subsequently entered was merely confirmatory of the oral transfer of the shares which had taken place earlier. Since stamp duty applied only to documents, nothing was due since the transfer had occurred verbally and the document merely operated as a confirmation that the transfer had taken place. The Inland Revenue’s response to that was that the transfer consisted of a disposition of an equitable interest and, under s 53(1)(c), such disposition was only effective if done in writing. That meant that the document recording the transfer of the shares was actually doing something and was not merely confirmatory in nature, if the shares were to be effectively transferred. As the document was active, stamp duty could be charged upon it.

The case reached the House of Lords. Viscount Simonds held that ‘disposition’ in s 53(1) (c) had to be given its natural meaning. That meant that the direction from Mr Hunter to his trustees to hold the shares on the trusts of his grandchildren was a ‘disposition’. To be valid, such a disposition had to be in writing. Thus the document which Mr Hunter later entered into was the only effective act to transfer the shares to the grandchildren. As the document was effective and not merely confirmatory, stamp duty was due.

Lord Radcliffe mused that the oral actions of Mr Hunter could, in theory, amount to a declaration of trust and, since the trust property was not land, such declaration could be valid even though it was not in writing. But he thought that where the beneficiary exhausted his equitable interest by his oral direction to the trustees, as had occurred here, that could also amount to a disposition of the equitable interest which, to be valid, had to be in writing to comply with s 53(1)(c).

Viscount Simonds applied the literal rule of interpretation to the word ‘disposition’ in Grey v IRC. Remember, however, the policy reason underpinning s 53(1)(c): that dispositions of equitable interests should be in writing so that the trustees always know who owns the equitable interest. Why was writing needed on the facts of this case? Mr Hunter had instructed the trustees explicitly to transfer the equitable interest to his grandchildren so they already knew the new owners of the equitable interest. In light of this, do you think that Grey v IRC was rightly decided? Was Viscount Simonds‘ interpretation of ’disposition‘ too one-dimensional? Should the House of Lords have reflected more deeply on the policy reasons behind the sub-section?

A potential shift away from the literal view: Oughtred vInland Revenue Commissioners28

This issue was considered again by the House of Lords, in an opinion delivered just two days after those in Grey v IRC in the case of Oughtred v Inland Revenue Commissioners. The facts concerned a mother and son’s shareholding in a private company. Shares were held by trustees for the mother, Phyllis Oughtred, as to 100,000 ordinary shares and a further 100,000 preference shares for her life, with remainder to her son, Peter. In order to save tax, Peter agreed that he would surrender his remainder interest in all of those shares, in return for which he would be entitled to 44,190 ordinary shares and 28,510 preference shares from his mother’s separate personal shareholding. This agreement was made orally. Eight days later, documents were executed formalising the transaction: the first being a document in which the trustees acknowledged that they now held Peter’s former shares on trust for Mrs Oughtred; the second being an actual transfer of those shares to Mrs Oughtred.

The Inland Revenue claimed stamp duty on the document transferring the shares to Mrs Oughtred. Their view was that Peter had disposed of his equitable (reversionary) interest in the 200,000 shares by transferring his equitable interest to the trustees. Transfers of equitable interests had to be in writing under s 53(1)(c) and this was the only document available which would satisfy that requirement. It therefore fell within the meaning of ‘disposition’ within that paragraph.

Lords Radcliffe and Cohen were in the minority in their opinions. Lord Radcliffe analysed the matter in this way:

[a] Originally, Peter owned a reversionary interest in the shares (i.e. an interest that he was entitled to enjoy at a later point in his life, after his mother had died);

[b] He orally agreed to transfer those shares to Mrs Oughtred. This oral agreement gave his mother an equitable interest in his reversionary interest;

[c] Mrs Oughtred now had a right in the shares. The shares were a unique item, such that if Peter had refused to transfer them, his mother could have obtained the remedy of specific performance in relation to the agreement reached with him;

[d] In being subjected to this theoretical action of specific performance, Peter became a trustee sub modo (i.e. subject to a condition or qualification) of that right for his mother. He had no option but to transfer the shares to her from that point onwards and had he not done so, she could have sued him for breaching that trust. Such a trust which arose was an implied constructive trust, arising by operation of law;

[e] Section 53(2) of the Law ofProperty Act 1925 specifically permitted such implied trusts to circumvent the requirements of writing in s 53(1);

[f] Peter’s trusteeship was confirmed as fully established when he received the promised shares from his mother; and

[g] As such, Peter continued to hold the shares on trust for his mother, a trust that was never required to be in writing due to it not consisting of land. The written documents did not, in Lord Radcliffe’s view, confirm that the trustees had been instructed to dispose of Peter’s equitable interest to his mother because the trustees never had any rights to dispose of at all. Peter always retained the rights in the shares, which he transferred to his mother.

The majority of their Lordships took a different view. Lord Denning took, for him, a rather strict view in that he believed that s 53(1)(c) required a disposition of an equitable interest to be in writing and such a requirement could not be circumvented by s 53(2). The written document transferring the shares to Mrs Oughtred therefore fell within the confines of s 53(1)(c).

Lord Jenkins, giving the leading speech of the majority, believed that even if Peter was a constructive trustee of the shares for his mother, this would not prevent a subsequent written transfer of the shares taking place. On the facts, a written transfer of the shares had taken place; since it had actually occurred, it was this document that was liable to stamp duty. To explain his view, Lord Jenkins used the analogy of a typical conveyancing transaction. When a house is agreed to be sold, at the point the agreement is made between the seller and buyer, the seller becomes a constructive trustee of the house for the buyer. It remains standard practice for the parties later to execute a formal transfer document. That latter document attracts stamp duty. Stamp duty does not become unpayable just because a constructive trust has already risen of the rights in the house in favour of the buyer. That analogy could be applied here. Even if Peter was a constructive trustee of the shares for his mother, the fact that they then entered into a transfer document in which he transferred his shares to the trustees for them to hold on trust for her meant that such a document could be considered to attract stamp duty.

Lord Jenkins believed that a beneficiary who enjoyed rights in property by virtue of a constructive trusteeship had a ‘lower’ category of rights than a beneficiary who had had an equitable interest properly transferred to them:29

In truth, the title secured by a purchaser by means of an actual transfer is different in kind from, and may well be far superior to, the special form of proprietary interest which equity confers on a purchaser in anticipation of such transfer.

To support this view, he explained that a purchaser of shares in a private company, as here, only enjoyed rights such as being able to vote at general meetings of the company when he was a full owner of the shares, as opposed to being entitled to them under a constructive trust.

Lord Jenkins was of the view that if the subject matter of the transaction could only be transferred by a written document, then any instrument executed in performance of the transaction would be subjected to stamp duty. This caught the documentation that had been executed in the case.

It appears, then, that it will not be sufficient to transfer an equitable interest orally if a written document is a normal and integral part of the means necessary to transfer that interest. The shares here were intended to be transferred by written document and the oral disposition by Mrs Oughtred to Peter was not sufficient to fulfil s 53(1)(c).

The minority view given credence: Re Holt’s Settlement30

That having been said, Megarry J appears to have been sympathetic to the views of the minority in Re Holt’s Settlement and did believe that it was possible to transfer some equitable interests orally, due to the transferor becoming a constructive trustee of them.

The facts concerned the variation of a trust (considered in more detail in Chapter 10). A settlor established a trust with a life interest for his daughter (a Mrs Wilson) with remainder interests for Mrs Wilson’s children equally provided they reached the age of 21. Mrs Wilson wished to vary the trust by, amongst other matters, surrendering her interest in half of the income from the trust and increasing the contingency age that her children might enjoy the trust property by nine years. That meant that the children would have to reach the age of 30 before they could enjoy the property, assuming that by then Mrs Wilson herself had died.

The three children were all infants. As will be seen,31 under the Variation of Trusts Act 1958, the court must approve a variation of a trust on behalf of an infant, since the child has no capacity to give their own consent.

In approving the variation of the trust, Megarry J accepted that such a variation did create a ‘disposition’ of an equitable interest by Mrs Wilson to her children. He realised that the House of Lords had given a wide meaning to that word in Grey v Inland Revenue Commissioners.32 But he thought that such disposition did not have to be in writing under the terms of s 53(1)(c). He thought that there was ‘considerable force’33 in the argument advanced by Lord Radcliffe in Oughtred v Inland Revenue Commissioners.34 He said that where the equitable interest passed under an agreement that could be enforced by a court order of specific performance, the equitable interest passed when that agreement was made. The means by which the equitable interest passed was by a constructive trust. Since constructive trusts did not have to be in writing by virtue of s 53(2), no writing was needed to pass the interest.

Megarry J appears to confirm in Re Holt’s Settlement that the transfer of an equitable interest need not be in writing if it passes by virtue of an agreement which would be specifically enforceable by a court order. A constructive trust is the mechanism by which the equitable interest passes and that species of trust is exempt from writing requirements under s 53(2).

Does this albeit limited exception go against the main principle underlying s 53(1)(c)? The concept behind the paragraph was to ensure that it is possible to say with certainty who owns the equitable interest at any point in time, since there should be a written document in evidence to prove that fact. If exceptions such as the transfer of an equitable interest by an unwritten constructive trust are allowed to exist, does this not make establishing the identity of the equitable owner harder on some occasions?

In addition, Megarry J’s view cannot be reconciled with that of Lord Denning in Oughtred v Inland Revenue Commissioners, who said that:

I should have thought that the wording of section 53 (1) (c) … clearly made a writing necessary to effect a transfer: and section 53 (2) does not do away with that necessity.35

Which view do you think is right?

A more modern view on the relationship between s 53(1)(c) and s 53(2)

The relationship between s 53(1)(c) and s 53(2) was considered more recently by the Court of Appeal in Neville v Wilson.36 The facts concerned a family dispute over a company’s shares. A company named J E Neville Ltd took over another company, Universal Engineering Co (Ellesmere Port) Ltd, in the late 1950s by buying all of its issued shares, which numbered 1,640. One hundred and twenty of those shares in Universal were held by two of its directors on trust, with J E Neville Ltd as the beneficiary.

In 1965, the directors of Universal met and, at the request of J E Neville Ltd, agreed to transfer all of the shares in Universal to the shareholders of J E Neville Ltd. The problem was that the 120 shares were not included within this transfer and the equitable interest in them remained in J E Neville Ltd.

Four years later, the shareholders of J E Neville Ltd informally agreed to dissolve that company. This occurred in the following year. Its assets were distributed between its shareholders. The issue for the court was whether the company still owned the equitable interest in the 120 shares at that point in time. If it did, they passed to the Crown as bona vacantia under s 354 of the Companies Act 1948. The alternative argument was that the informal agreement to dissolve the company disposed of all of J E Neville Ltd’s assets, including those 120 shares. The problem was that this agreement was not in writing. Insofar as the agreement purported to transfer the equitable interest in those 120 shares, it had to be in writing to comply with s 53(1)(c).

The Court of Appeal held that the agreement reached in 1969 was to dissolve J E Neville Ltd and that, from that point onwards, it was never intended that the company should be left with any assets. For this reason, the agreement to dissolve the company must have included the 120 shares in dispute.

Whilst the agreement was not in writing, the Court of Appeal held that it could be saved by s 53(2). When making the agreement to dissolve the company, each shareholder of J E Neville Ltd became a constructive trustee of their shareholding for the recipients of the assets of that company. That meant that s 53(2) could apply and the agreement did not need to be in writing.

Giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Nourse LJ examined the decisions of the various courts in Oughtred v Inland Revenue Commissioners.37 He accepted Lord Radcliffe’s view that s 53(2) could effectively override s 53(1)(c), although he recognised Lord Denning’s rejection of that concept. Overall, he thought that as a matter of policy s 53(2) should be able to apply in certain cases to override s 53(1)(c). He said:

Why then should subsection (2) not apply? No convincing reason was suggested in argument and none has occurred to us since. Moreover, to deny its application in this case would be to restrict the effect of general words when no restriction is called for, and to lay the ground for fine distinctions in the future. With all the respect which is due to those who have thought to the contrary, we hold that subsection (2) applies to an agreement such as we have in this case.38

Consequently, it seems as though the view that s 53(2) can override s 53(1)(c) and can prevail where it is possible to hold that an agreement to transfer an equitable interest is capable of being specifically performed and a constructive trusteeship is created. Such agreements, which transfer only the equitable interest, appear not to have to be in writing, following Neville v Wilson.

Does s 53(1)(c) apply where the legal estate is transferred from one trustee to another recipient?

The final transaction to be considered in relation to s 53(1)(c) is whether a legal estate, transferred by one trustee to another recipient, constitutes a ‘disposition’ within the meaning of the section, given that it also transfers with it the equitable interest in the trust property. This arose in Vandervell v Inland Revenue Commissioners.39

The facts of this case have been considered in detail in Chapter 3. In brief, Mr Vandervell wanted to sponsor the establishment of a Chair in Pharmacology with the Royal College of Surgeons. He asked his bank, as trustee, to transfer the shares in which he owned the equitable interest to the Royal College. A right was retained for Vandervell Trustees Ltd to repurchase the shares from the Royal College for £5,000. One issue for the House of Lords was whether s 53(1)(c) applied to the transaction to transfer the shares to the Royal College. This depended on whether there was a transfer of the equitable interest by the bank when it transferred the shares to the Royal College.

Lord Upjohn explained the reasoning behind the enactment of s 53(1)(c):

the object of the section … is to prevent hidden oral transactions in equitable interests in fraud of those truly entitled, and making it difficult, if not impossible, for the trustees to ascertain who are in truth his beneficiaries.40

Lord Upjohn said that s 53(1)(c) did not apply to the situation that Mr Vandervell found himself in. It did not apply to where an equitable owner, owning under a bare trust, asked his trustee to deal with the whole legal and equitable interest together.

Glossary: Bare trust

A bare trust exists where the equitable owner is over 18 years old, enjoys mental capacity and owns the absolute interest in the trust property but the property is still managed by a trustee. The equitable owner has a right, under Saunders v Vautier,41 to bring the trust to an end and enjoy the trust property themselves. For some reason, the equitable owner chooses not to exercise that right but to leave the trust subsisting.

Section 53(1)(c) had no application to the situation where the legal and equitable interests were ‘glued’ together. The section only applied where the equitable interest was being dealt with on its own, separately from the legal estate. Consequently, an oral direction by Mr Vandervell to the bank as his trustee was sufficient to transfer the equitable ownership in the case. It was because the legal estate was also being transferred at the same time. There was no requirement, where the two interests were transferred together, for the writing requirements of s 53(1)(c) to be fulfilled. By being asked to transfer the equitable interest to another beneficiary, the trustees would know the new location and ownership of the equitable interest.

Lord Upjohn took into account the policy reasoning behind s 53(1)(c) in Vandervell v IRC and, in so doing, applied the ‘mischief’ rule of statutory interpretation and asked what was the mischief the statute was designed to prevent? It was to prevent hidden oral transactions. Yet the mischief rule generally only applies if the literal meaning of the statute is not clear. In Grey v IRC, Viscount Simonds thought that the literal meaning of the statute was perfectly clear: all dispositions of equitable interests had to be in writing to fulfil s 53(1)(c). Whilst there seems to have been no legal reason to apply the mischief rule in Vandervell v IRC, it is suggested that its application gives a more sensible result to the facts and reflects the policy behind the statute. Do you think that rules of statutory interpretation should be ‘bent’ in this almost Machiavellian manner where the end justifies the means?

The result, however, of the first case was that Mr Vandervell still owned the equitable interest in the shares, due to the existence of a resulting trust in his favour. In 1961, Vandervell Trustees Ltd exercised the option to buy back the shares from the Royal College. The trustees used £5,000 from Mr Vandervell’s children’s trust. The Royal College transferred the shares to the trustee company which then held them on the trusts for the children. The trustee company advised the Inland Revenue of this transaction. In ReVandervell’sTrusts (No. 2) ,42 the Inland Revenue claimed that despite this transaction occurring, Mr Vandervell had not divested himself of the equitable interest in his shares. It claimed that it was not until four years later, when Mr Vandervell executed a formal document transferring the equitable interest to the trustee, that he had complied with s 53(1)(c).

In the Court of Appeal, Lord Denning MR held that the resulting trust on which the shares had been held for Mr Vandervell came to an end when the trustees exercised the option to buy back the shares and the shares were registered in the children’s names. This was a declaration of a new trust by the trustees in favour of the children — not the disposition of an equitable interest. Since the trust property was money, this declaration could be created orally since s 53(1)(b) only applied to declaring trusts of land.