Chapter 16

Cy-près

Chapter Contents

Cy-près and General Charitable Intention

This chapter builds upon the discussion of charities in Chapter 15 and specifically looks at the doctrine of cy-près. This is a doctrine which can apply when a charitable gift fails. The doctrine broadly operates to enable the property in the gift to be transferred to another charity with similar objects.

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

![]() how the doctrine of cy-près may be defined;

how the doctrine of cy-près may be defined;

![]() how, if it applies, cy-près ensures that the charitable gift will not revert to resulting trust; and

how, if it applies, cy-près ensures that the charitable gift will not revert to resulting trust; and

![]() how the provisions of the Charities Act 2011 give the doctrine of cy-près application than that under the common law.

how the provisions of the Charities Act 2011 give the doctrine of cy-près application than that under the common law.

Definition of Cy-près

Cy-près means ‘as near as possible’. The general principle is that if a charitable gift has failed because it cannot be carried out by the trustees of the testator’s will exactly according to his wishes, the trustees may make an application to the Charity Commission1 to apply the gift to another charity whose objects are, as near as possible, to that charity whom the donor intended to benefit. In this way, it may be said that as much charitable good as possible in the circumstances will still come from the donor’s gift as the donor intended.

The application of cy-près to the gift means that a resulting trust2 of that property to the donor’s estate is disapplied.

Cy-près will not apply in every situation where a charity fails. It will only apply if the donor of the gift showed a general charitable intention in giving his gift or establishing his charitable trust.

If the charitable gift has not failed, cy-près has no application. There are three occasions when it has been held that the gift has not failed. These are where:

[a] the charity continues in another form;

[b] there is a gift for the purposes of an unincorporated assocation;3 or

[c] the charitable institution has been described incorrectly.

These exceptions to when cy-près may be used will be considered first.

Glossary — testator/testatrix

These terms are used throughout this chapter. A testator is a male who has written his will; a testatrix a female who has done the same.

Exceptions to Cy-près

The charity continues in another form

If the charity continues in another form, the charitable gift will not have failed. This occurred in Re Faraker.4

Mrs Faraker left £200 in her will to ‘Mrs Bailey’s Charity Rotherhithe’. There was no charity by that name in Rotherhithe, but there was a similarly named ‘Hannah Bayly’s Charity’. The latter charity had been established originally to benefit poor widows in Rotherhithe. Some six years before Mrs Faraker’s death, Hannah Bayly’s Charity had been merged with 13 other charities in the Rotherhithe area and the combined charity’s object was to aid the poor in that area. It was admitted that Mrs Faraker had meant to leave the money to Hannah Bayly’s Charity, but the issue for the court was whether the gift had lapsed when that charity had merged with the others.

The Court of Appeal held that the gift had not lapsed. Hannah Bayly’s Charity was not, said Cozens-Hardy MR, extinct. All that had happened was that its objects had changed. These objects had changed lawfully as a scheme to merge the charity with the 13 others had been approved by the Charity Commissioners. Mrs Faraker did not give her money to a particular charity; she gave it to a charity which was simply identified by a particular name. The gift to the charity had not failed at all. It was only if the charity had failed by, for example, there ceasing to be any poor widows in Rotherhithe, that the doctrine of cy-près could apply.

There is a gift for the purposes of an unincorporated association

A gift left for the purposes of an unincorporated association will not be subject to the cy-près doctrine as long as those purposes continue. This occurred in Re Finger’s Will Trusts.5

Georgia Finger divided her residuary estate in her will into 11 equal parts and left them to charitable insitutions. Amongst the recipients were the National Radium Commission and the National Council for Maternity and Child Welfare. Both of these organisations no longer existed by the time of her death. Her executors sought directions as to whom the sums left to those two bodies should be paid.

The National Radium Commission was an unincorporated association which was charitable. Appoving the obiter comments of Buckley J in Re Vernon’s Will Trusts,6 Goff J held that a gift to an unincorporated charity could be seen to be a purpose trust whose purpose would not fail but could be carried on by another charitable insitution because the original gift was to further particular purposes. This was subject to two provisos. First, if the testatrix’s intention was to benefit a particular institution which had ceased to exist at the date of her death, the gift could not take effect as a purpose trust. It had to be established that the testatrix wanted to benefit the purpose in general, as opposed to the particular institution. Second, the charitable purpose still had to exist now even though the particular institution to whom the gift was left had disappeared.

The gift to the National Council for Maternity and Child Welfare failed because this body was incorporated. Goff J held that this meant the testatrix’s intention was to benefit that particular institution and not charitable purposes in general. When that institution ceased to exist, the gift had to fail.

As the gift had failed, Goff J considered whether he could find a general charitable intention by the testatrix. He held that she did have a general charitable intention by leaving the whole of her residuary estate to charitable institutions. Consequently, the doctrine of cy-près could apply to the gift for the National Council for Maternity and Child Welfare. A scheme was proposed to pay that gift to the National Association for Maternal and Child Welfare, which Goff J approved.

The charitable institution has been described incorrectly

If the donor incorrectly describes the recipient institution but it is clear that the donor intended to benefit only that particular organisation, the gift can still take effect to that organisation under a scheme. This can be shown by the decision of Megarry V-C in Re Spence.7

Beatrice Spence left half of her residuary estate in her will for the benefit of the patients at ‘The Blind Home, Scott Street, Keighley’. No such exact institution existed. There was, however, a Keighley and District Association for the Blind which had existed for decades. It had a blind home at 31 Scott Street, Keighley. Megarry V-C quickly held that the actual home was the same as that described by Miss Spence in her will and it should benefit.

More difficult was the subsequent issue of whether the money could only be used for the home at Scott Street, Keighley or whether it had to be put towards the charity’s general funds, as the charity also ran another home in Bingley. Megarry V-C held that Miss Spence’s intention was that only the patients at the particular home in Keighley should benefit from her gift. As this was not quite how she had described her intention in her will, he ordered that a scheme should be made under which the gift could be paid for the benefit of the patients at the home owned by Keighley and District Association for the Blind at Scott Street, Keighley.

Cy-près was not relevant to this part ofher residuary estate as the gift had not failed as such.

If none of these exceptions are valid and the gift has failed because the recipient no longer exists, prima facie, the gift will return to the donor’s estate on a resulting trust. If, however, it can be said that the donor displayed a general charitable intention in their gift, a cy-près scheme will be ordered by the court so that the gift may instead be transferred to another recipient and not returned to the donor’s estate.

Cy-près and General Charitable Intention

General charitable intention must be shown before a gift can be transferred to another recip-ient. A proposed transfer of the gift to another recipient is called a ‘scheme’. In Re Lysaght,8 Buckley J defined general charitable intention as:

a paramount intention on the part of the donor to effect some charitable purpose which the court can find a method of putting into operation, notwithstanding that it is impracticable to give effect to some direction by the donor which is not an essential part of his true intention — not, that is to say, part of his paramount intention.9

If a general charitable intention can be found, another charitable recipient can receive the gift provided their charitable objects are broadly the same as the original recipient intended by the testator.

Suppose Scott Leaves £100,000 in his will for the advancement of education at Derbyshire School. Derbyshire School closed before Scott’s death but after he wrote his will.

The gift would be charitable as it is for the advancement of education under s 3(1)(b) of the Charities Act 2011 and it is for the public benefit.

As the school has closed, the gift cannot be administered by Scott’s trustees in the manner anticipated by Scott. Whether the gift can be applied cy-près to another similar institution depends on whether Scott displayed a general charitable intention in his will.

If it could be shown that Scott intended to benefit educational charity in general, then the gift could be applied cy-près to another institution. If, on the other hand, it was only Derbyshire School that Scott intended to benefit, no cy-près scheme can be ordered as Scott did not display a general charitable intention.

Buckley J’s words show that the court draws a distinction between where the testator includes an essential provision in his gift that the entire gift depends upon for it to be administered. In such a case, no general charitable intention can be shown and the gift cannot be applied cy-prts if it fails. Such would be the case in the example above if the court concluded that the only way of effecting the gift would be the now-impossible task of paying the money to Derbyshire School because Scott had intended that only that school should benefit from his generosity. In contrast, if the testator merely indicates how he would like the gift to be administered, he does display a general charitable intention because the precise means of how the gift should be applied are not essential to the gift being administered. In such a case, the gift can be applied cy-près.

Buckley J also emphasised that general charitable intention did not mean that the testator could only leave an original gift which benefited either ‘charity’ in the most general terms or one particular head of charity again in general terms. ‘General’ is used in contrast to a particular set of instructions being given so that the gift can only be administered in a certain way. Provided no set of instructions was given by the testator, it can usually be said that he had a general charitable intention.

General charitable intention can be demonstrated by the donor or under the provisions of s 62 of the Charities Act 2011.

General charitable intention by the donor

Key Learning Point

General charitable intention must be considered in two situations: (i) subsequent failure and (ii) initial failure.

Subsequent failure occurs when the gift fails after the testator has died but before his estate (property) is distributed. This is, of course, usually a comparatively short period of time.

Initial failure covers a much wider timescale. It occurs where the recipient of the gift had ceased to exist at the date of the testator’s death but was still in existence when the testator wrote his will.

Subsequent failure

‘Subsequent failure’ is so called because the gift fails subsequent to the testator’s death, but before his estate is distributed by his personal representatives. If this occurs, the gift can readily be applied for an alternative charitable institution. The phrase ‘subsequent failure’ was used by Kay LJ in describing how the gift had failed after the testator’s death in Re Slevin.10

In the case, a gift was left in a will of £200 ‘to the Orphanage of St Dominic’s, Newcastle-on-Tyne’. The orphanage closed after the testator’s death, but before his estate was distributed. The issue for the Court of Appeal was whether the gift could be applied cy-près to another charity, or whether it would fall back to the estate as a resulting trust as the object had ceased to exist.

In giving the judgment of the Court of Appeal, Kay LJ compared the position to that of an individual who had been left a legacy under a will and who had died after the testator but before the money was given to him. The money would belong to the individual from the point of the testator’s death. Such money would not fall back into the estate under a resulting trust.

The same principle could be applied to an institution. The institution became the equitable owner of the £200 at the date Mr Slevin died. When the orphanage ceased to exist, its property had to be administered by the Crown whose task was to apply it for a similar charitable purpose as that undertaken by the orphanage.

Re Slevin was followed by Romer J in Re King,11 which considered the issue of a surplus of money remaining after the charitable purpose of the gift had been fulfilled.

Here the testatrix left her entire estate on trust to provide a stained glass window in the church in Irchester for certain members of her family and herself. There was approximately £300 remaining of her residuary estate after the cost of providing the window had been deducted from it. The executors sought directions as to whether the entire gift was charitable or not and if it was, whether the surplus could be applied cy-près in providing a further stained glass window in the church. The next-of-kin (who, if successful, would have received the surplus) argued that a general charitable intention on the testatrix’s behalf had to be found if the surplus was to be applied cy-près and that simply leaving a gift to make and install a stained glass window showed no general charitable intention.

Romer J had no doubt that the gift was charitable. He also held that the surplus could be applied cy-près for a second window in the church. He referred to Re Slevin and held that the decision in that case was authority for a more general principle that if a gift was left for a charitable purpose which was otherwise well provided for without the gift, the gift would be applied cy-près. He thought that was the case here.

It must be questioned whether the principle in Re Slevin is necessarily as wide as propounded by Romer J in Re King. The institution had ceased to exist after the testator’s death in Re Slevin but this was largely irrelevant as it had already had the gift given to it at the point of the testator’s death. Clearly, the church in Re King had not ceased to exist after the date of the testatrix’s death but the gift had still been given to it at the date of her death. A perhaps narrower interpretation needs to be applied to Re Slevin than that propounded in Re King. It is suggested that all the principle in Re Slevin consists of is that once property is given to an institution, the institution may keep it (because equitable ownership has passed) and if the institution then ceases to exist, it may be applied as a cy-près scheme for the purposes of a similar charitable organisation.

Initial failure

Initial failure occurs when the recipient institution had ceased to exist before the testator’s death. If it can be shown that the testator intended to benefit charity generally in his will, another charitable organisation can receive the gift under a cy-près scheme. If, on the other hand, no general charitable intention can be shown, the gift will simply return to the testator’s estate under a resulting trust.

Some of the case law under this heading is difficult to reconcile with other decided cases. In all cases, however, the court is attempting to decide whether the testator showed a general charitable intention or simply a specific desire to benefit one particular charity. If the latter and the institution has ceased to exist after the testator’s death, no cy-près scheme can be permitted.

Instances where general charitable intention has been found …

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Biscoe v Jackson12 is one of the earliest which shows this distinction between a general purpose and a particular recipient.

Joseph Jackson left £10,000 in his will to his trustees to establish a soup kitchen and cottage hospital in Shoreditch, London. Unfortunately, no land could be found in Shoreditch to establish either the hospital or soup kitchen. The issue was whether a cy-près scheme could be ordered to vary the gift.

The Court of Appeal held that the testator had shown a general charitable intention by his gift. Cotton LJ explained that the testator had shown a general intention to benefit the poor and sick of Shoreditch. The testator had simply pointed out how he wished the gift to be effected: by the creation of a soup kitchen and hospital.

If, therefore, the testator has shown a charitable intention with simply a desire as to how that should be carried out and it is impossible to accede to the testator’s desire, a cy-près scheme can alter the mechanism suggested by the testator to implement his gift for a similar charitable purpose.

Such general charitable intention was shown again in Re Roberts.13 Jane Roberts left her residuary estate on trust to be split into six equal parts and then to be applied to six named charities. One part was to be applied to the ‘Sheffield Boys Working Home (Western Bank, Sheffield)’. The home had been closed and sold some 16 years before the testatrix died, but after she had made her will. The money held by the trustees of the home mainly went to the Sheffield Town Trust to create a fund called the ‘Sheffield Boys Working Home Fund’ with a request that the income from it should be used to benefit boys’ organisations in the city. A small balance was retained by the two trustees of the home.

Wilberforce J held that the courts had gone ‘very far’ 14 in cases to avoid reaching the conclusion that a gift to a charity had lapsed. He held that the trust of the home still continued, as the trustees had retained a small amount of money to meet expenses after the home itself was sold. Re Faraker had decided that the Charity Commissioners had no general power to bring a charitable trust to an end; Wilberforce J held that neither did the particular trustees on the exact terms of this trust. Consequently, the trust of the home still existed.

He said that despite the precise wording of the gift leaving money for the home, the gift was actually for the purposes of the institution as opposed to the home itself. He cited the decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Lucas,15 which had held that it was always a question of construction of the testator’s words in his will as to whether the gift was for the purposes of a specific institution or whether general charitable intention had been shown. On the facts, he thought that the testatrix had shown an intention to benefit a charitable purpose, not just its physical building.

As the testatrix had intended to benefit the charity in general as opposed to its physical building and as the trust continued to exist, the funds could be administered by a cy-près scheme.

The issue here is always whether the testator intended to benefit charity in general or a particular institution. A gift to several charities and one non-charitable organisation may suggest in itself that the testator had a general charitable intention. Megarry V-C referred to this as ‘charity by association’ in Re Spence.16 It can be illustrated by the contrasting decisions in Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts.17 and Re Jenkins’ Will Trusts.18

In Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts, Phyllis Sattherthwaite wrote her will in which she left all of her residuary estate to animals, claiming that she hated the human race. She asked her bank manager to prepare for her a list of animal charities and he did so by referring to the London telephone directory. She divided her residuary estate into nine equal parts and left each part to what she thought was an animal charity. One of the ‘charities’ was the London Animal Hospital. This was not a charity at all, but a private veterinary practice. Mr Rich, the owner of the London Animal Hospital, claimed the share of the money.

The Court of Appeal held that the testatrix’s aim was to benefit a purpose as opposed to any individual. Harman and Russell LJJ thought that due to the other recipients of the testatrix’s residuary estate being charitable in nature, a general charitable intention could be inferred. A cy-près scheme would be ordered so that another similar charity could benefit.

Russell LJ offered an additional explanation. He thought that if a name under which a person was working was descriptive, as Mr Rich’s London Animal Hospital, any testamentary gift should be taken not as an intention to benefit either the particular business or its owner but instead a charitable purpose, because it would appear to the outside world as though the business was charitable. The difficulty with this analysis is how it can be reconciled with the testatrix’s intention. It is, perhaps, stretching the point to suggest she showed a general charitable intention by specifically naming a recipient which constituted a mere example of the type of charity she wished to benefit.

This decision may be contrasted with Re Jenkins‘ Will Trusts. Here, Frances Jenkins left her residuary estate to be divided into seven equal parts. One part was to be given to the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection for them to use to obtain an Act of Parliament to abolish animal testing. This was not a charitable purpose as abolishing vivisection was a political aim.19 The issue was whether this gift could be applied cy-près as the other six gifts were charitable.

Buckley J held that the gift could not be applied cy-près. Simply because other charitable gifts had been left by the testatrix did not mean that this particular one was also charitable. As he put it, ‘[i]f you meet seven men with black hair and one with red hair you are not entitled to say that here are eight men with black hair’.20 The testatrix had not shown a general charitable intention simply by leaving other gifts for charitable purposes.

It is hard to reconcile Re Jenkins‘ Will Trusts with Re Satterthwaite. The latter was decided only 12 days before the former and the decision of the Court of Appeal in Re Satterthwaite does not appear to have been cited to Buckley J in Re Jenkins’ Will Trusts.

Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts suggests that it is relevant to consider the other bequests that the testator made in his will as they must throw light upon the testator’s general intention. Re Jenkins’ Will Trusts questions how other gifts can be relevant to the one specific gift in question.

Which decision do you think takes the correct approach — and why?

Instances where no general charitable intention has been found …

In Re Spence, Miss Spence left the other half of her residuary estate for the benefit of the patients at ‘the Old Folks’ Home at Hillworth Lodge, Keighley’. Hillworth Lodge had been closed down as a home for aged persons after Miss Spence had executed her will, but before she died. The Home had not been run as, or by, a charity.

Megarry V-C held that the gift itself was for charitable purposes but that, as it could not be given when Miss Spence died, the gift would fail unless a general charitable intention could be found on her part. He could not find a general charitable intention. He said that it would be difficult to find a general charitable intention where there was only one other gift the court had to consider: in Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts21 a general charitable intention had been found partly because the testatrix had left eight other charitable gifts. There was more evidence of a general charitable intention the greater the number of other clearly charitable gifts were left.

Megarry V-C compared gifts which had been left to particular institutions and those left to particular purposes, both of which existed at the time the testator made the will but had ceased by the time the testator had died. The court was reluctant to sieve out of a gift to a particular institution an intention to benefit charity generally. The same was true for a gift left for a particular purpose, as in this instance. It could clearly be said that Miss Spence intented to benefit the aged persons at Hillworth Lodge, Keighley. It would be something of a leap to say that she had a general charitable intention. As such, no cy-près scheme was ordered and this part of her residuary estate passed as on intestacy.

If the testator takes care in his will to describe a particular recipient, the court will find it difficult to construe a general charitable intention if the institution then ceases to exist before the testator dies, as was shown by the decision of the High Court in Re Harwood.22

The testatrix left £200 to ‘the Wisbech Peace Society, Cambridge’. The society had ceased to exist before she died. The issue was whether the testatrix had demonstrated any general charitable intent as she had left a list of other charitable societies in her will who should benefit from legacies.

Farwell J held that a cy-près scheme for the gift could not be ordered. He held that where the testatrix had ‘gone out of her way to identify the object of her bounty’,23 there was no room to imply a general charitable intent from her gift. She intended to benefit the Wisbech Peace Society and that was all.

On the other hand, her other legacy to the ‘Peace Society of Belfast’ could be applied cy-près. This society had never existed. Farwell J held that the testatrix intended to benefit any society which promoted peace in Belfast. She thus demonstrated a general charitable intention and so her gift could be applied cy-près.

The consequences of cy-près applying

If a general charitable intention is found to exist and cy-près is, therefore, applicable, the court (or the Charity Commission) will authorise a scheme to ensure that, in most cases, a charitable recipient with similar charitable objects receives the charitable gift.

It is not always the case, however, that the recipient of the gift has to be a different organisation from that intended by the testator if the recipient does still exist. This occurred in Re Lysaght24 where the gift failed largely for administrative reasons. cy-près may, after all, apply where it is impossible to carry the testator’s gift into effect as desired by the testator.

The facts in Re Lysaght concerned Rosalind Lysaght’s purported gift to the Royal College of Surgeons to establish scholarships for students to study medicine. Her gift had a number of conditions attached to it. The contentious one was in clause 11(D) that any recipient of a scholarship could not be either Jewish or Roman Catholic. The gift failed because the Royal College of Surgeons declined to accept it on such terms.

Buckley J held that the overall purpose of the testatrix was to establish medical scholarships through the Royal College of Surgeons. This purpose evidenced a general charitable intention on her part. The criteria she included, of which those in clause 11(D) were part, did not detract from this intention: they were merely there to administer the gift.

Normally, a trustee could not modify the terms of a trust: the trustee’s task was to administer it only and if he did not wish to do so, his normal course of action would be to step down from the office of trusteeship to be replaced by a trustee who will administer the trust. But here the testatrix had made it clear that her scholarships could only be administered by the Royal College of Surgeons.

Buckley J held that her insistence that scholarship recipients must not be Jewish or Catholic would have defeated the testatrix’s paramount intention that the gift be administered by the Royal College of Surgeons. It would have destroyed the trust. Hence he held that the court would order a cy-près scheme under which the gift could still be given to the Royal College without the conditions as to religion attached to it.

The cy-près scheme will, therefore, be used flexibly by the court to deal with a charitable gift that cannot be carried into operation precisely according to the testator’s instructions.

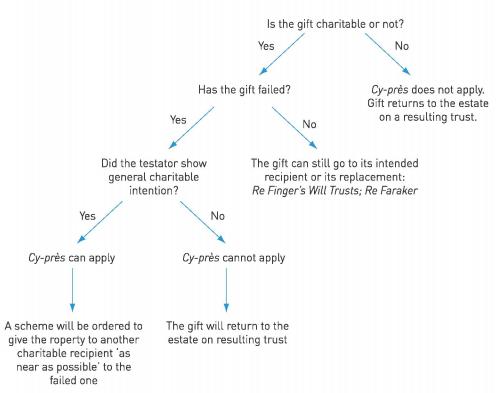

A summary of the doctrine of cy-près can be found at Figure 16.1.

Charities Act 2011, s 62

Section 62 of the Charities Act 2011 has widened out when a cy-près scheme may be permitted. Before the first predecessor of this section was enacted,25 it used to be the case that a cy-près scheme would only be permitted if it was absolutely impossible or impracticable to carry out the testator’s intention. A cy-près scheme could not be put into effect just because it was thought that using the money in a different way would be a better use of the testator’s gift. This principle was illustrated in Re Weir Hospital.26

Benjamin Weir left two houses for the purposes of converting them into a dispensary or cottage hospital for the benefit of the residents of Streatham. He also left his residuary estate (£100,000) to maintain the dispensary or hospital. The trustees of the trust initially used one house as a dispensary, but then suggested a cy-près scheme to the Charity Commissioners under which the other house would be used as a nurses’ home and the majority of the residuary estate would be used to enlarge the general hospital which was located outside the parish of Streatham.

The Charity Commissioners approved the cy-près scheme, but the Court of Appeal held that it was ultra vires (outside) the main purposes of the testator’s will and had to be discharged. A cottage hospital could still be established using the testator’s houses and his money used to maintain it. The Charity Commissioners, who themselves had suggested the scheme to the trustees, merely considered it more desirable to benefit the general hospital. cy-près was not applicable in such circumstances. As Cozens-Hardy MR put it, ‘there can be no question of cy-près until it is clearly established that the directions of the testator cannot be carried into effect’.27

It was neither for the court nor the Charity Commissioners to weigh up the advantages or disadvantages of the testator’s charitable gift. If at least one purpose intended by the testator remained, his gift had to be administered for that purpose. A cy-près scheme could not be used to disregard the testator’s intentions unless those intentions simply could not be carried out.

Section 62 of the Charities Act 2011 widens out when cy-près may be applied.28 Section 62(1) provides the following five alternate circumstances where, although the testator’s intended use of the gift might not have failed entirely, the doctrine of cy-près may nonethe-less still be applied. These are where ‘the original purposes of a charitable gift can be altered’:

[a] where the original purposes, in whole or in part –

[i] have been as far as may be fulfilled; or

[ii] cannot be carried out, or not according to the directions given and to the spirit of the gift,

[b] where the original purposes provide a use for part only of the property available by virtue of the gift,

[c] where (i) the property available by virtue of the gift, and (ii) other property applicable for similar purposes, can more effectively be used in conjunction, and to that end can suitably, regard being had to the appropriate considerations, be made applicable to common purposes,

[d] where the original purposes were laid down by reference to (i) an area which then was but has since ceased to be a unit for some other purpose, or (ii) a class of persons or to an area which has for any reason since ceased to be suitable, regard being had to the appropriate considerations, or to be practical in administering the gift, or

[e] where the original purposes, in whole or in part, have, since they were laid down —

[i] been adequately provided for by other means, or

[ii] ceased, as being useless or harmful to the community or for other reasons, to be in law charitable, or

[ii] ceased in any other way to provide a suitable and effective method of using the property available by virtue of the gift, regard being had to the appropriate considerations.

Each of these circumstances must be considered. As a preliminary point, however, s 62 cannot be used as a method of altering administrative arrangements in a charitable gift. Its objective is to enable the court to apply the gift for similar charitable purposes as the testator intended, as Re JW Laing Trust29 illustrates.

John Laing established a trust under which he left what became a considerable sum of money (approximately £24 million) to trustees to distribute to Christian evangelical causes. The trust was established with a provision which required the capital sum to be distributed within ten years of the settlor’s death. After his death, the trustees sought the court’s approval to remove this stipulation either under the equivalent of s 62(1)(e)(iii) or the court’s inherent jurisdiction.

Peter Gibson J held that the ‘original purposes’ of the gift within the meaning of s 62 meant those ‘for which the property given is applicable’.30 ‘Purposes’ did not include administrative directions on the trustees as to when the distribution of the property had to occur. The direction that the property had to be distributed within a certain time was concerned with how the property was to be distributed — not for what purpose. As such, it was an administrative provision that could not be altered by s 62.31

Section 62(2) sets out that the ‘appropriate considerations’ in paragraphs (c), (d)(ii) and (e)(iii) refer to two distinct matters: (i) the ‘spirit of the gift’ and (ii) social and economic circumstances prevailing at the time the scheme is proposed. Neither matters were new to the Charites Act 2011. That regard must be had to the ‘spirit of the gift’ was mentioned in the Charities Act 1960 32 and the explicit need to take into account social and economic factors was first enacted in the Charities Act 2006, s 15.

As You Read

As you read the following part of this chapter, considering paragraphs (c), (d)(ii) and (e)(iii) of s 62, ask yourself whether the courts were perhaps already taking into account social and economic factors when they came to approve the various cy-près schemes even before this requirement was mentioned explicitly by s 15 of the Charities Act 2006.

Where the original purposes have been carried out or cannot be carried out

An example of the identical predecessor to s 62(1)(a)(ii) was considered in Re Lepton’s Charity,33 where the High Court discussed the meaning of the phrase ‘spirit of the gift’.

Joseph Lepton wrote his will in 1715 and provided that his land in Pudsey, Yorkshire, should be left to his trustees to pay a Protestant dissenting minister the annual sum of £3 and to distribute any other profits from the land to the poor and aged in Pudsey. Mr Lepton died the following year, when the annual income from his land was £5.

By 1968, the annual income from the trust had increased to £791. The trustees brought an action asking whether the testator’s direction that an annual sum of £3 be paid to the minister was really a charitable gift of £3 per annum or three-fifths of the annual income of the land. The trustees also wanted a scheme approved whereby £100 per annum would be paid to the only Protestant dissenting meeting place in Pudsey, the Congregational chapel. They brought their action under the previous identical provisions to s 62(1)(a)(ii) and s 62(1)(e) (iii).

Pennycuick V-C considered the meaning of the phrase ‘spirit of the gift’ in paragraphs (a) (ii) and (e)(iii) meant ‘the basic intention underlying the gift’.34 That intention could be ascertained from the terms of the testator’s will and any admissible evidence. He also thought that paragraph (e)(iii) simply expanded upon paragraph (a)(ii) and was not distinct from it.

The phrase ‘the original purposes of a charitable gift’ applied to the trusts as a whole and not to each of the recipients — the minister and the poor — separately. That was because the testator had left one sum of money to be divided between two recipients. He had effectively left only one gift. The question for the court was whether the original purposes could not be carried out in relation to the basic intention of the testator underlying the gift or whether, in the language of paragraph (e)(iii), the gift ‘ceased to provide a suitable and effective method of using the property’.35

Pennycuick V-C held that the testator’s intention was to split one amount of money so that the minister would get a ‘modest but not negligible sum’. When the testator’s gift took effect in the will, the minister would receive a three-fifths share of the money. As Pennycuick V-C put it, the testator’s ‘intention is plainly defeated when in the conditions of today the minister takes a derisory £3 out of a total of £791’.

He thought that the conditions for cy-près to operate had been satisfied. £100 was a reasonable amount for the minister to receive at the time of the decision and a scheme would be ordered to that effect. The poor and aged of Pudsey would continue to receive the rest of the annual income.

The decision of Pennycuick V-C is interesting in amalgamating paragraphs (a)(ii) and (e) (iii). It is suggested that the paragraphs are not necessarily the same. Paragraph (a)(ii) seems to suggest that the original purposes of the gift cannot be carried out from the very beginning of the gift taking effect. Paragraph (e)(iii), on the other hand, talks about the purposes ceasing, which suggests that they have been at least capable of being carried out but they are no longer capable of being carried out. If this is right, the facts of Re Lepton’s Charity Charity suggest that the cy-près scheme should more properly have been ordered under paragraph (e)(iii). It is, admittedly, true that on the facts of Re Lepton’s Charity this was probably a distinction without a difference.

If the original purposes provided for a use for part only of the property

Here, the whole property has been given as a charitable gift but the testator has only provided a use for part of it. It makes logical sense for a scheme to be ordered, perhaps to enlarge the charitable purpose to cover the whole gift.

Where the property and other property can be used more effectively together

Again, a scheme can be ordered here, where it makes sense to mix the property left by the testator with other property. The recipient charity can only benefit more from such an approach being adopted.

Where the original purposes were set out by reference to an area or a class of people which have ceased to be suitable

The meaning of this paragraph was considered by the High Court in Peggs v Lamb.36

Various pieces of land had been used since time immemorial (1189) for the benefit of freemen and their widows in Huntingdon. The Charity Commissioners had recognised the gift of the land as a charity. However, by 1991, the number of freemen had reduced to such an extent, and the value of the income from the land increased to such an extent for those few freemen, that the Charity Commissioners doubted that the gift of the land could still be seen to be charitable. Various parts of the land had been sold for housing development. Too much benefit was being paid to too few people, regardless of their need: for example, in 1900, 34 freemen received about £17 each, but in 1990, each freeman received £31,750. The Charity Commissioners suggested that the trustees of the trust apply for a cy-près scheme that the income should only be paid to freemen of Huntingdon in need and the surplus to the poor and sick of the borough.

Morritt J held that the trust of the land was a charitable trust:37 the land was originally a gift for the benefit of all of the freemen and the widows of Huntingdon. He followed Pennycuick V-C’s definition of ‘spirit of the gift’ in Re Lepton’s Charity and held that the original purposes of the gift were general charitable purposes for freemen and their widows in Huntingdon.

A scheme for the gift could be ordered under paragraph (d). When the land was first assumed given to the trust, freemen constituted a large section of society. The declaration of a trust to benefit such freemen was practicable at the time. But the importance and number of freemen had declined over the centuries.

Morritt J held that the spirit — or original intention — of the gift was to benefit the borough of Huntingdon. He held that it would be consistent with that intention to enlarge the beneficiaries of the gift to the entire inhabitants of the borough. The original class of persons was now unsuitable to benefit from the trust so a scheme could be ordered under paragraph (d) in favour of a new class. That new class was still within the spirit of the original gift.

Where the original purposes of the charitable gift have ceased

This paragraph consists of three parts:

[a] where the original purpose is now being provided for by other means;

[b] where the original purpose has ceased as being ‘useless or harmful to the community’; and

[c] where the original purpose has ceased ‘in any other way’ to be a ‘suitable and effective method’ of using the property for the intended gift.

As already noted, Pennycuick V-C in Re Lepton’s Charity was of the view that (iii) was merely an expansion of the right contained in paragraph (a)(ii).

The application of paragraph (e)(iii) was considered by the Court of Appeal in Varsani v Jesani.38

The facts of the case concerned the religious followers of the Swaminarayan faith as taught by its founder in the UK, Shree Muktajivandasji Swaminarayan. A charitable trust had been declared in 1967 of property for the faith which mainly consisted of a temple in London. The followers of the faith had split into two groups in 1985, with the minority group refusing to accept the authority of the then leader of the faith. The two groups were also divided on which group should continue to use the temple. Both groups wanted the court to resolve which group could use the temple.

The Court of Appeal commented on the applicability of s 13 of the Charities Act 1993 (the immediate and near identical predecessor to s 62). The enactment of this section had replaced the previous case law, exemplified in decisions such as Re Weir Hospital, which decided that cy-prè could only apply if performing the charitable gift was impossible or impractical. There was no need for the court to decide if it was impossible or impractical for the gift to be performed. Section 13 of the Charities Act 1993 widened out the applicability of cy-près. On the facts, the test now was to be found in paragraph (e)(iii): had the original purpose of the gift ceased to provide a suitable and effective use of the property, regard being had to the spirit of the gift?

Both Morritt and Chadwick LJJ commented on the phrase ‘the spirit of the gift’. Morritt LJ said it was only used in certain paragraphs of s 13 — these were paragraphs where the court had to make a ‘value judgment’.39 He said it meant the court had to have regard to ‘the basic intention underlying the gift or the substance of the gift rather than the form of words used to express it or conditions imposed to effect it’.40

The ‘spirit of the gift’ also referred to when the gift was originally given, not at the stage of litigation. The court sought to ascertain the spirit in which the donor gave the gift. That could generally be ascertained from the trust document and other evidence of the circumstances in which the gift was made.

The purposes of the gift when it was given was to promote the Swaminarayan faith through Muktajivandasji’s teachings and worship in a temple in London. Until the group split, those purposes were a suitable and effective method of using the temple as a place of worship. Now the groups could no longer worship together and so the temple could no longer be used to pursue the original purposes. The court did enjoy jurisdiction to make a cy-près scheme under paragraph (e)(iii).

Charities Act 2011, s 63

Section 63 of the Charities Act 2011 specifically deals with the application of cy-près to a charitable gift given by an anonymous donor or by a donor who has executed a document disclaiming the return of the gift in the event of the gift failing. The purpose of s 63 is that surplus money arising from when a charity fails may be applied cy-près without the need to seek the original donor’s consent.

An anonymous donor under s 63 of the Charities Act 2011 would include a person who contributes to a charity through a collecting tin in a street or who buys a lottery ticket to support the good cause.

The application of s 63 is not restricted to such persons, however. It also applies to people who cannot be identified or found after making a charitable gift to a charity which has then failed or simply fulfilled its purpose. It additionally applies to those people who, despite being identifiable, have expressly stated that they do not want their gift returned to them if the charity fails.

If money remains after the purpose has failed or been fulfilled, the trustees may make a cy-près scheme to deal with the money raised.

In all cases, before a cy-prèts scheme can be made by the charity trustees, the trustees must show that the gifts originally belonged to the donors. For people who have made their gift through a collecting box or via a ‘lottery, competition, entertainment, sale or similar money-raising activity’, s 64(1) states that such property will be ‘conclusively presumed’ to belong to the donors who cannot be identified. Similarly, if the donor has executed a disclaimer specifically stating that they do not want their gift returned if the charity fails, the property can be taken as belonging to them when they made the gift.41 There is no need for the charity’s trustees to seek those donors out. In all other cases,42 the trustees must show that they have tried to trace the donors and that the donors cannot be identified or found, according to s 63(1)(a). The advertisements must be in a format and for a content prescribed in regulations made by the Charity Commission.43 Providing no donors come forward within that time period, their gifts can be applied cy-près.

Section 65 of the Charities Act 2011 provides that the donor can request the return of his gift instead of it being given cy-près to another charity if his original charity fulfils its purpose or otherwise fails. To do so, the original gift must have been given for ‘specific charitable purposes’ and the charity must have made it clear originally that it would apply the gift cy-prts if its original, specific charitable purpose failed.44

If the charity’s purposes fail and the trustees do offer the donor the return of his gift but he refuses it or cannot be found, he is treated as though he has executed a disclaimer of the gift under s 65(6).

Points to Review

You have seen:

![]() that when a charitable gift fails, the doctrine of cy-près may apply which will enable an alternative charity which is ‘as near as possible’ to the recipient of the original gift to benefit from that gift. This contrasts with a non-charitable trust where the gift will usually go back to the settlor on a resulting trust basis;

that when a charitable gift fails, the doctrine of cy-près may apply which will enable an alternative charity which is ‘as near as possible’ to the recipient of the original gift to benefit from that gift. This contrasts with a non-charitable trust where the gift will usually go back to the settlor on a resulting trust basis;

![]() for cy-près to be applicable, the testator must have held a general charitable intention to benefit charity. This is particularly important if the gift has failed initially; and

for cy-près to be applicable, the testator must have held a general charitable intention to benefit charity. This is particularly important if the gift has failed initially; and

![]() that it used to be the case that it must be impossible or impractical to apply the gift for the original charity for cy-près to be applied. This impossibility or impracticability has been widened out by the circumstances in s 62 of the Charities Act 2011 which now defines when cy-prèsmay apply.

that it used to be the case that it must be impossible or impractical to apply the gift for the original charity for cy-près to be applied. This impossibility or impracticability has been widened out by the circumstances in s 62 of the Charities Act 2011 which now defines when cy-prèsmay apply.

Making connections

Cy-près is concerned with when a charitable gift fails. It is important to understand when a gift will be classed as charitable and when not. This is discussed in Chapter 15.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

The best reading is contained in the primary sources listed below. It is always good to consider the decisions of the courts themselves as this will lead to a deeper understanding of the issues involved. A few secondary sources are also listed, which you may wish to read to gain additional insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Primary sources

Re Lysaght [1966] Ch 191.

Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts [1966] 1 WLR 277.

Re Jenkins’ Will Trusts [1966] Ch 249.

Varsani v Jesani [1999] Ch 219.

Charities Act 2011, ss 62–65.

Secondary sources

Elise Bennett Histed, ‘Finally barring the entail?’ (2000) LQR 445–473. An article of interest to those who enjoy legal history as it considers the history of the cy-près doctine and the notion of barring the entail, a concept which may have been touched upon in your studies of land law.

Jonathan Garton, ‘Justifying the cy-près doctrine’ (2007) Tru. L.I. 134–149. An interesting article which discusses how the cy-près doctrine has been justified in case law.

Alastair Hudson, Equity & Trusts (7th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) ch 25.9.

John Picton, ‘Kings v Bultitude — a gift lost to charity’ [2011] 1 Conv 69–74 (note). This article examines the decision of the High Court in the recent case of Kings v Bultitude [2010] EWHC 1795 (Ch) that a charitable gift to an independent church which had ceased to exist after the testator’s death could not be saved by the cy-près doctrine. The article asks whether the gift could, in fact, have been saved.

Mohamed Ramjohn, Text, Cases and Materials on Equity & Trusts (4th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2008) ch 17.

Paul Ridout, ‘Settling the tab’ (2011) T.E.L & T.J. 127 (Jun), 14–17. This article considers the judgment of the court in White v Williams (No. 2) [2011] EWHC 494 (Ch) concerning the transfer of a place of worship from one charitable trust to another. It looks at how to prepare a cy-près scheme from a practitioner’s point of view.

1 Originally it was the Court of Chancery which authorised cy-près schemes, but the Charitable Trusts Act 1860 s 2 permitted the Charity Commissioner s to do so.

4 Re Faraker [1912] 2 Ch 488.

5 Re Finger’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 286.

6 ReVemon’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 300.

7 Re Spence [1979] Ch 483.

8 Re Lysaght [1966] Ch 191.

9 Ibid at 202 (emphasis added).

10 Re Slevin [1891] 2 Ch 236.

11 Re King [1923] 1 Ch 243.

12 Biscoe v Jackson (1887) LR 35 Ch D 460.

13 Re Roberts [1963] 1 WLR 406.

14 Ibid at 412.

15 Re Lucas [1948] Ch 424.

16 Re Spence [1979] Ch 483 at 494.

17 Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts [1966] 1 WLR 277.

18 Re Jenkin’s Will Trusts [1966] Ch 249.

19 See Chapter 15 at pp 424–426.

20 Ibid at 256.

21 Re Satterthwaite’s Will Trusts [1966] 1 WLR 277.

22 Re Harwocd [1936] Ch 285.

23 Ibid at 287.

24 Re Lysaght [1966] Ch 191.

25 Charities Act 1960, s 13.

26 Re Weir Hospital [1910] 2 Ch 124.

27 Ibid at 132.

28 An identical provision giving the court the power to use the cy-près doctrine was first enacted in s 13 of the Charities Act 1960.

29 Re JW Laing Trust [1984] Ch 143.

30 Ibid at 150.

31 Peter Gibson J did, however, hold that the cour t could remove the condition as to distribution in the exercise of its inherent jurisdiction.

32 Charities Act 1960, s 13.

33 Re Lepton’s Charity [1972] Ch 276.

34 Ibid at 285.

35 This question was formulated by Pennycuick V-C at 285.

36 Peggs v Lamb [1994] Ch 172.

37 He relied on the decision of the House of Lords in Goodman v Mayor of Saltash 7 App Cas 633.

38 Versani v Jesani [1999] Ch 219.

39 Ibid at 234.

40 Ibid.

41 Charities Act 2011, s 63(1)(b).

42 Unless the Charity Commission orders that it is unreasonable either in relation to the (small) amount s involved or in relation to the time lapse since the gifts were given, for such advertisements to be made : s 64(2).

43 Charities Act 2011, s 66(4),(6).

44 Ibid, s 65(1).