Chapter 6

Trust Formation: The Beneficiary Principle

Chapter Contents

Definition of the Beneficiary Principle

Exceptions to the Beneficiary Principle

The task of understanding the components needed to form an express trust continues in this chapter with a discussion of another essential element: the beneficiary principle and its exceptions. The beneficiary principle is the notion that, generally speaking, an express trust must exist for the benefit of an individual (or individuals) as opposed to a purpose or cause.

As You Read

As you read, focus on the following:

![]() the definition of the beneficiary principle: the central idea That English law prefers trusts to be for the benefit of an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary rather than for a defined purpose;

the definition of the beneficiary principle: the central idea That English law prefers trusts to be for the benefit of an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary rather than for a defined purpose;

![]() how the beneficiary principle links in to the other requirements needed to declare an express trust; and

how the beneficiary principle links in to the other requirements needed to declare an express trust; and

![]() exceptions to the beneficiary principle: what they entail, how they apply and their relevance to today’s world.

exceptions to the beneficiary principle: what they entail, how they apply and their relevance to today’s world.

Definition of the Beneficiary Principle

The beneficiary principle is the concept that a private, express trust must be for the benefit of a beneficiary who the trustees can either ascertain or is at least ascertainable. In practical terms, this means that the settlor must settle property on trust for the benefit of an individual or individuals (or, on some occasions, a company1) who are sufficiently well defined so that the trustees can understand the identity of the people for whom they are administering the trust.

This requirement can be contrasted with a trust being set up to pursue a purpose. English law traditionally frowns upon trusts being for the benefit of a purpose. As a general rule, a trust set up for a purpose instead of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries will be void. These principles can be illustrated by Re Astors Settlement Trusts.2

Viscount Astor purported to declare a trust in February 1945 of most of the issued shares in The Observer Limited, a company owning a national newspaper. The trust provided that the shares were to be held for a number of purposes including, for instance, ‘the establishment, maintenance and improvement of good understanding sympathy and co-operation between nations’ and ‘the preservation of the independence and integrity of newspapers’. Crucially, the trust was only established for purposes and it was not possible to say that any human beneficiary would directly benefit from the trust.

Roxburgh J held that the trust was void since there was no human beneficiary who could benefit from the trust. He relied on the earlier leading case of Bowman v Secular Society Ltd3 in which Lord Parker had said:4

A trust to be valid must be for the benefit of individuals … or must be in that class of gifts for the benefit of the public which the courts in this country recognize as charitable in the legal as opposed to popular sense of that term.

Roxburgh J examined the reasoning behind Lord Parker’s statement. He pointed out that at the heart of a trust was a series of equitable rights that a beneficiary enjoyed. These equitable rights had been ‘hammered out’5 in litigated cases over many years. Taken as a whole, the people who enjoyed the equitable rights under a trust — the beneficiaries — had the ability to enforce them against the trustees if the trustees refused to honour these rights voluntarily. Human beneficiaries could take court action against recalcitrant trustees. Roxburgh J confirmed that a trust required that there had to be a physical person who was a beneficiary and who could, if necessary, take such court action against the trustees to enjoy their equitable rights. Trusts for purposes, as Viscount Astor had declared, gave rise to no single individual enjoying equitable rights which meant there was no human person who had the right to take court action against the trustees if they failed in their duties as trustees.

Suppose Scott settles £100,000 on trust. He appoints Thomas as his trustee. Scott provides in the declaration of trust that he wants the money to be invested by Thomas and the proceeds to be used each year for the development of world peace.

No doubt this is a worthwhile purpose, but such a trust would be void since it infringes the beneficiary principle. Suppose Thomas refused to invest the money according to Scott’s wishes. Who would then enforce the trust against him? There is no-one to do so because there is no human beneficiary who could take court action against him. Remember that, as settlor, Scott cannot take action against the trustee for breach of trust because the settlor (unless he has expressly reserved such a power to himself in the trust documentation) has no involvement in the trust once it has been established.

Rationale of the beneficiary principle

The main reason behind the requirement that a trust should have a human beneficiary benefiting from it has been shown in the examination of the judgment of Roxburgh J in Re Astors Settlement Trusts.6 His view, echoing that of Lord Parker in Barlow v Secular Society Ltd,7 reaffirmed the long-established position set out in Morice v Bishop of Durham8 that, as far as a trust was concerned, ‘[t]here must be somebody, in whose favour the court can decree performance’.

In this sense, equity is acting with a mixture of both pragmatism and pre-planning. Equity realises that not all trustees may act in the best interests of the beneficiaries but they may instead act to benefit themselves. For example, some trustees may simply fail in their obligations towards the trust by, for example, failing to take proper advice before investing trust money. If the trustees fail in their duties towards the trust, regardless of whether the trustees themselves benefit personally from their failings, there has to be someone who can take action against them. That person cannot be the settlor for, as we have seen, the settlor generally steps out of the trust once he has set it up. By almost a process of elimination, the only person left in the relationship to ensure that the trustees keep to the right track is the beneficiary. There is no-one else to take action against the trustees: for example, the court will not of its own instigation take action; neither is there an officer of the government whose job it is to hold trustees of private trusts accountable.

English law, therefore, embodies the idea that there must be someone who can take action against the trustees into one of the ingredients required to declare a trust: the beneficiary principle. The corollary of the principle, as illustrated by the facts of Re Astors Settlement Trusts, is that English law does not like trusts for purposes as a general concept.

There is a second reason for the law of trusts embodying the beneficiary principle. It is more of a legalistic reason. In Chapter 2 you saw how the concept of a trust involves split ownership: that the trustee holds the legal title to the property and the beneficiary enjoys the equitable interest. An equitable interest will, therefore, always exist in a trust. There must be someone who can enjoy that equitable interest as it cannot exist without it attaching to a beneficiary. An equitable interest cannot simply ‘float’ around without being owned because, of course, equity abhors a vacuum. The beneficiary principle, therefore, ensures that someone owns the equitable interest in the property of the trust. It is possible to see this second reason as being tied to the same underlying principle as certainty of object that was considered in Chapter 5. At their heart, both concepts require a beneficiary to be present in a valid trust.

The third reason given for the existence of the beneficiary principle is related to the rules against perpetuity.9 The rule against perpetuity which is relevant here is the rule against inalienability. This provides that the capital of the trust must reach the beneficiaries for them to enjoy at some point in the future. The idea behind this rule is that a trust must come to an end at some point. If the trust does not come to an end within the time period contemplated by this rule, it will be void for offending the rule against inalienability.

Trusts which do not have any identifiable beneficiaries but are instead for a purpose offend the rule against inalienability. This is because a purpose may well last forever, which will require the money to be reinvested time and again. As such, the money is tied up for the purpose instead of being available in the wider economy. The beneficiary principle thus supports the rule against inalienability by ensuring that there should be an identifiable beneficiary who will eventually take the legal title in the trust property and use the trust property in the wider economy.

Exceptions to the Beneficiary Principle

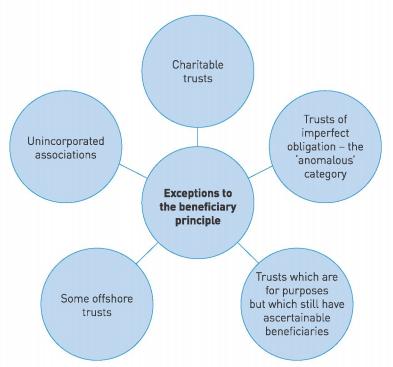

The general rule is that there must be a human beneficiary for there to be a valid declaration of trust. However, for almost every rule there is an exception. There are five main exceptions, see Figure 6.1.

Charitable trusts

Charitable trusts are a major topic of the law of trusts in their own right and are considered separately in Chapter 15.

There are two key requirements for a trust to be charitable under the Charities Act 2011:

[a] there must be a charitable purpose as defined under s 3(1) of that Act; and

[b] the charity must be able to demonstrate, through its activities, a sufficient benefit to the public or a section of it, under s 2(1)(b ) of the Act.

Most trusts which meet these requirements of charitable status do not, of course, have defined human beneficiaries and some, at first glance, do not directly benefit humans at all.

Consider some of the most well-known charities in England and Wales such as the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), Barnardo’s or Cancer Research UK.

It cannot be said that any of these charitable trusts have defined human beneficiaries. Instead, they exist to benefit society as a whole through their daily activities.

Yet such trusts are permitted to exist and, in addition, can be granted charitable status which, as will become apparent,10 enables them to enjoy significant tax-saving advantages.

The reasons why such trusts are permitted even though they infringe the beneficiary principle are two-fold:

[a] as a matter of public policy, charities should be encouraged to exist due to the good works that they undertake. If charities were not allowed to exist, their good works would either fall to the government to implement or simply lapse. Either may not be as beneficial to society as a whole as allowing a charity which understands its respective area to exist. In addition, should the government have to provide such services, the increased cost would fall to the tax-payer; and

[b] The main reason underpinning the beneficiary principle is that there has to be somebody who can, if needed, take legal action to force the trustees to honour their obligations in administering the trust correctly. As far as charities are concerned, a separate mechanism exists to ensure that charitable trustees administer their charitable trust correctly. The Charity Commission is the relevant body responsible for overseeing charities and, if action is required to be taken against a charity’s trustees, such action is taken by the Attorney-General, one of the government’s legal officers. The Attorney-General acts on behalf of the Crown, whose overall responsibility it is to ensure that property belonging to a charity is administered correctly.

Trusts of imperfect obligation

A trust of an imperfect obligation is a trust which has no defined human beneficiary and which would, at first glance, appear to infringe the beneficiary principle since such a trust is for a purpose. These trusts are permitted to exist. They are an ‘anomalous’ 11 category of trusts which may, albeit sometimes quite loosely, benefit the public in some way. The reason why such purpose trusts are permitted to exist has not been fully explained judicially. In Re Astors Settlement Trusts,12 Roxburgh J acknowledged that the explanation put forward by the well-regarded academic Sir Arthur Underhill that such trusts were judicial ‘concessions to human weakness or sentiment’ 13 may well be correct. In addition, these types of trust are usually of small enough scope to be able to be controlled by the court if necessary.

Such trusts fall into three main categories:

[a] trusts relating to tombs and monuments;

[b] trusts for the provision of masses in private; and

[c] trusts benefiting a specific animal.

These purpose trusts are trusts which still, however, need to meet the other requirements to form a valid express trust. So they must comply with any requirements of formality, adhere to the principles of certainty and meet the rules against perpetuity. It would seem that the only requirement which is relaxed in their favour is the need to have a human beneficiary benefiting from the trust.

Trusts relating to tombs and monuments

These types of trust arise where property is left on trust with the purpose of providing for the establishment and/or upkeep of specific memorials in churches.

In Re Hooper,14 Harry Hooper left £1,000 on trust for trustees to invest and use the income for four purposes:

[a] the upkeep of his parents’ grave in Torquay cemetery;

[b] the upkeep of a vault and monument, also in Torquay cemetery, in which his wife and daughter were buried;

[c] the upkeep of a grave and monument in a churchyard near Ipswich in which his son was buried; and

[d] the care of a tablet and a window in a church at Ilsham, which were devoted to the memories of some of his family members.

The issue for the High Court was whether this trust was valid. Clearly, there could be no defined human beneficiaries of the trust, as all the people to whom the trust referred had already predeceased Mr Hooper.

Maugham J held that the trust overall was valid. In a short judgment, the reasoning why the trust was valid was not especially detailed. He followed an earlier High Court decision15 which had reached the same result and Maugham J was guided by matters of pragmatism:

The case does not appear to have attracted much attention in text-books, but it does not appear to have been commented upon adversely, and I shall follow it.16

The fourth part of the trust was, however, held to be charitable. Again, there is no explanation given by Maugham J but it may be presumed that he felt that it was for a valid charitable purpose (presumably for the advancement of religion) and could be said to benefit a section of the public through their enjoyment of viewing the tablet and the window in the church.

This latter part of the decision illustrates that the courts prefer, if possible, not to recognise valid trusts of imperfect obligation, but instead hold them to be valid charitable trusts. Indeed, the courts have no wish to extend these categories of purpose trust and prefer to keep them within narrow confines as illustrated by Re Endacott.17

In this case, Albert Endacott wrote his will in which he left his residuary estate (worth approximately £20,000) to North Tawton Devon Parish Council for them to provide ‘some useful memorial to myself’.The Court of Appeal held that the obligatory nature of Mr Endacott’s bequest meant that a trust had been created. The issue was whether such a trust could be valid given that there was no human beneficiary who could enforce the trust. It was clearly a trust for a purpose.

The Court of Appeal held that the trust could not be valid. It was a type of trust which left far too much open to be decided in the future. No-one could police this type of trust over what the North Tawton Devon Parish Council chose to spend the money on.

Lord Evershed MR believed that the categories of trusts of imperfect obligation ought not to be extended in the future. A cardinal principle in English law was that a trust required an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary to enforce it. Trusts of imperfect obligation were an exception to that requirement but, as an exception, they had to be kept within narrow confines. Harman LJ went further, saying that all categories of trusts of imperfect obligation:

stand by themselves and ought not to be increased in number, nor indeed followed, except where the one is exactly like another.18

He summed up his true feelings on cases of trusts of imperfect obligation, calling them ‘troublesome, anomalous and aberrant’.19

The decision also illustrates that the courts will have little sympathy for purpose trusts of a capricious nature.

It appears, then, that trusts involving the establishment or upkeep of memorials will be permitted, but only when such trusts are well defined so that they can be said to be managed by the court if necessary. Widely drafted trusts involving awarding the recipient a great deal of discretion over the type of memorial to be established will not be permitted.

Trusts for the provision of Masses in private

This second type of trust of imperfect obligation is based upon a particular type of ceremony in the Catholic Church: the Mass.

Typically, a settlor will set up a trust in which money is left to the Catholic Church which helps to meet the additional costs of a priest being available to conduct a separate Mass for the soul(s) of the person named in the trust. The souls who are usually mentioned in the trust are those of the settlor’s spouse, family and friends and perhaps the settlor themselves. These types of trust are usually created in the settlor’s will and so only take effect on the settlor’s death. There is no living beneficiary who would be able, if necessary, to enforce the trust. This is a further example of a trust for a purpose: the purpose being to pray for the souls mentioned in the trust.

That this type of trust could exist as a trust of imperfect obligation was decided by the House of Lords in Bourne v Keane.20 This area had been wrapped up in the historical development of the Church of England in its break-away from the Catholic Church. Previous case law, espe-cially West v Shuttleworth,21 had decided that leaving property to the Roman Catholic Church to pay for a priest to say Masses constituted a ‘superstitious use’ which was not permitted under the preamble to the Chantries Act 1547. By way of departure from this previous jurisprudence, the House of Lords in Bourne v Keane decided that the Chantries Act 1547 had not been enacted with the intention to prevent property being left for such masses to be said.

In the case itself, Edward Egan made a will in which he left £200 to Westminster Cathedral and his residuary estate to the Jesuit Fathers. In both instances, the money was left for Masses to be said.

The House of Lords held that such gifts were valid. As Lord Birkenhead LC pointed out, gifts to the Catholic Church to build a new church or provide for an altar in an existing church had long been held to be valid (albeit as valid charitable gifts). He said that it would be an ‘absurdity’ if:

a Roman Catholic citizen of this country may legally endow an altar for the Roman Catholic community, but may not provide funds for the administration of that sacra-ment which is fundamental in the belief of Roman Catholics, and without which the church and the altar would alike be useless.22

A more recent case which has considered this issue is Re Hetherington.23 The case concerned the will of Margaret Hetherington. She was described as a ‘devout Roman Catholic’,24 so it was not surprising that she desired to benefit the Catholic Church in her will. Two clauses of her will are relevant here. First, she left £2,000 to the Roman Catholic Church Bishop of Westminster ‘for the repose of the souls of my husband and my parents and my sisters and also myself when I die’. Second, she left her residuary estate to the Roman Catholic Church St Edward’s Golders Green ‘for Masses for my soul’. The issue for the High Court was whether such provisions in the will could validly take effect as trusts of imperfect obligation.

Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson, V-C, held that the provisions of Mrs Hetherington’s will could take effect as valid charitable trusts. They were plainly for the benefit of religion. In addi-tion, there was nothing in the will which provided the Masses had to be said in private. Where a gift for the benefit of religion could be celebrated either privately or publicly, the Vice-Chancellor followed the earlier decisions in Re White25 and Re Banfield26 and held that the service should be carried out in public. Through attending the service, members of the public could benefit from the spiritual nature of the religious rite. This public benefit meant that Mrs Hetherington’s trusts could be seen to be of a charitable nature and were valid on this basis.

The decision again illustrates the reluctance of the courts in modern times to find examples of trusts of imperfect obligation. Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson again referred to trusts of imperfect obligation as ‘trusts of the anomalous class’27 which suggests he had little appetite to keep this category of trust alive by adding further examples to it. On the facts, it was not necessary to hold that Mrs Hetherington’s were further examples of trusts of imperfect obligation and the Vice-Chancellor instead preferred to recognise the trusts as examples of more soundly-established charitable trusts.

Think about whether the decision in Re Hetherington, to prefer the trust as being of a charitable nature, is necessarily consistent with the House of Lords decision in Bourne v Keane. Whilst the House of Lords did not extensively consider the issue of whether Edward Egan’s gift could have charitable status, Lord Buckmaster did appear to rule out that possibility when he said that ‘[i]n the present case, no general charitable intention is disclosed’.

The Vice-Chancellor in Re Hetherington held that where the trust was silent on whether the Masses could be said in public or in private, they should be said in public since this would provide sufficient benefit on members of the public who attended to mean that the trust could have charitable status.

Yet the facts in neither case suggested that the settlor had made any express intention clear as to whether the Masses were to be said in public or private.

The House of Lords in Bourne v Keane appears to have assumed that the Masses were to be said in private and that there was no public benefit to be attained from the services. At the very least, the decision in Re Hetherington stretches the settlor’s intentions by providing that the Masses can be said in public where the settlor has not provided that the service must be held in private. Lord Buckmaster in Bourne v Keane had presumably thought that such a development was not a possibility on the facts before him.

Trusts to benefit a specific animal

Trusts established to benefit animals in general (e.g. the RSPCA) will usually have charitable status as enhancing animal welfare is a charitable purpose under s 3(1)(k) of the Charities Act 2011. Public benefit in protecting animals was explained by Swinfen Eady LJ in Re Wedgwood28 in that such a trust:

tends to promote and encourage kindness towards [animals], to discourage cruelty … and thus to stimulate humane and generous sentiments in man towards the lower animals, and by these means promote feelings of humanity and morality generally, repress brutality, and thus elevate the human race.29

Trusts set up to benefit only one particular type of animal — for example, the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds — are usually considered charitable too for the same reasons.

The category of trust considered here is that which is established to protect the settlor’s personal animals. These trusts cannot be charitable as they do not benefit the public but rather just the settlor. Such trusts were recognised as valid trusts of imperfect obligation in Re Dean.30

Mr William Dean was an animal lover. He provided in his will that his freehold land should be held on trust. It was to be subjected to an annual sum of £750 being taken out of the income from it and given to his trustees so that they would have sufficient money to be able to look after his eight horses and his dogs. The trust was to last for 50 years from his death.

North J held that the trust could take effect as a valid trust. He said that there had been other cases in which sums of money had been validly left on trust despite the trusts having had no beneficiary to enforce them. He quoted a trust to build a monument as an example. He did not see any reason why a similar type of trust which could not be enforced should not be valid.

The more general comments that North J made to the effect that a trust could be valid despite having no beneficiary to enforce it should probably be treated with caution nowadays, given the Court of Appeal’s reluctance in Re Endacott31 to sanction the recognition of further categories of trusts of imperfect obligation. Nevertheless, the principle in Re Dean still stands and it is possible, therefore, to have a valid trust in favour of the settlor’s personal animals.

It seems that North J entirely ignored the perpetuity point in the case. This trust could have come into effect more than 21 years from Mr Dean’s death, so should have been held to have been invalid.

People often leave large sums of money in their wills for the benefit of their pets. In 2010, it was reported in America that multi-millionaire Gail Posner had bequeathed Conchita, her pet Chihuahua, a house worth $8.3 million and a separate sum of $3 million for her maintenance. Her son, Bret, had been left $1 million and he is in the process of bringing an action to try to increase his share of his mother’s estate, at Conchita’s expense.

Prima facie, such a trust in favour of Conchita would be valid in English law pursuant to Re Dean.

Other categories of trust of imperfect obligation?

The main categories of trust of imperfect obligation which have been recognised by the courts have been considered. There are other examples where such trusts have been held to be valid, but these are mostly one-off situations and are peculiar to the facts of the individual cases. Such examples include:

![]() A trust for the promotion and furtherance of fox hunting as occurred in Re Thompson.32 Here the testator left £1,000 to his friend, George Lloyd, in order that the money should be applied in whatever manner Mr Lloyd thought fit to promote and further fox hunting. In a short judgment, Clauson J took the pragmatic consideration that the gift to Mr Lloyd was ‘of a nature to which effect can be given’.33 The overriding points in the case seem to be that the gift was clearly defined by the testator and the judge thought that it should be upheld. Nowadays, as indicated in Re Endacott, unless a further case had precisely the same facts as Re Thompson, it is likely that the court would be more inquisitive as to whether the trust should be valid than just considering whether the trust had been clearly defined. Given that hunting wild mammals with dogs has now been banned by Parliament,34 it is unlikely that a future trust which promotes traditional fox hunting with hounds would be upheld.

A trust for the promotion and furtherance of fox hunting as occurred in Re Thompson.32 Here the testator left £1,000 to his friend, George Lloyd, in order that the money should be applied in whatever manner Mr Lloyd thought fit to promote and further fox hunting. In a short judgment, Clauson J took the pragmatic consideration that the gift to Mr Lloyd was ‘of a nature to which effect can be given’.33 The overriding points in the case seem to be that the gift was clearly defined by the testator and the judge thought that it should be upheld. Nowadays, as indicated in Re Endacott, unless a further case had precisely the same facts as Re Thompson, it is likely that the court would be more inquisitive as to whether the trust should be valid than just considering whether the trust had been clearly defined. Given that hunting wild mammals with dogs has now been banned by Parliament,34 it is unlikely that a future trust which promotes traditional fox hunting with hounds would be upheld.

![]() A trust for the promotion of non-Christian religious ceremonies: Re Khoo Cheng Teow.35 Here, clause 5 of Mr Khoo Cheng Teow’s will directed that a building at 56 Church Street, Singapore, be rented out and the money raised should be used for the furtherance of ‘reli-gious ceremonies according to the custom of the Chinese called Sin Chew’. Terrell J held that there was no reason why such a trust should not be valid:

A trust for the promotion of non-Christian religious ceremonies: Re Khoo Cheng Teow.35 Here, clause 5 of Mr Khoo Cheng Teow’s will directed that a building at 56 Church Street, Singapore, be rented out and the money raised should be used for the furtherance of ‘reli-gious ceremonies according to the custom of the Chinese called Sin Chew’. Terrell J held that there was no reason why such a trust should not be valid:

it is fitting and proper that the same validity should be accorded to gifts for the performance of ceremonies which are an essential feature of the religious rites of the Chinese …36

The decision illustrates that equity will not distinguish between different faiths and religions. A trust for the private performance of any recognised religious ceremony can thus be valid.

The categories of case that will be upheld as trusts of imperfect obligation are now closed, following Re Endacott and, following Re Hetherington, it seems that the courts will, wherever possible, prefer to recognise a trust which can be interpreted as having a public element to it as charitable rather than as a further example of a noncharitable purpose trust. This is all part of the general principle which is to dissuade settlors from establishing trusts without ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries to enforce them.

Purpose trusts but which nonetheless have ascertainable beneficiaries

As has been considered, the main reason why purpose trusts are not upheld in English law is because there is no-one who can compel the trustees to administer the trust if they refuse to do so. Unless the trust has charitable status or can be seen to fall within one of the ‘anomalous’ categories of trusts of imperfect obligation, the general principle used to be that any other trust established for a purpose would fail. This was shown in Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales.

The facts involved the will of Francis Leahy. Under clause 3, he left his property called ‘Elmslea’ in Bungendore, Australia, together with his furniture, on trust:

for such order of nuns of the Catholic Church or the Christian Brothers as my executors and trustees shall select …

The Privy Council held that the trust created by Mr Leahy was a trust for a purpose. It did not benefit specific individuals, but instead was a trust of property which was to be held on trust for the purpose of whichever order of nuns or Christian Brothers that the trustees actually selected. To hold that the trust was for the benefit of individuals would be to go against the evidence available on the facts in three ways:

[a] the wording used by Mr Leahy spoke of the property being held for an ‘order’ of nuns or Christian Brothers. This suggested the property being held on trust for the order’s purposes as opposed to the individual members of such an order;

[b] if the trust was a trust benefiting individuals, as opposed to a purpose, the trust would have to benefit all of the members of the chosen orders of nuns or Christian Brothers who were living, no matter where they were located across the world. It was thought that this was unlikely to have been Mr Leahy’s intention. No doubt he wished to benefit nuns or members of the Christian Brothers who were based closer to him in New South Wales; and

[c] Elmslea was a substantial property, consisting of approximately 730 acres of land, a 20-room main building and several outbuildings. It was unlikely that Mr Leahy’s intention was to divide that size of property up between individuals. It was unlikely he would have seen that the nuns or Christian Brothers would have themselves personally owned the equitable interest in his property. Instead, it was far more likely that, as a whole, the property might be used for the purpose of benefiting an entire order of nuns or Christian Brothers.

Overall, Mr Leahy’s intention was to benefit an order to help secure and further its work in the future. As such, Mr Leahy had created a purpose trust. Such a trust would be invalid in law.37 Despite Mr Leahy seemingly setting out that the trust was for individuals, the court would look to the substance of the trust and see that it was essentially a trust for purposes. After all, equity looks to the substance and not the precise form in which a document is drafted. As the trust was for purposes, it had to fail.

This point was, however, reconsidered by Goff J in Re Denley’s Trust Deed38 where he suggested that not every purpose trust would automatically fail.

The facts concerned a trust deed made in August 1936 by Charles Denley and others in which land located in Gloucestershire was settled on trust for the purpose of a sports or recreation ground. Under clause 2(c) of the trust deed, the land could be used by two categories of person:

primarily for the benefit of the employees of [a company] and secondarily for the benefit of such other person or persons (if any) as the trustees may allow.

As in Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales, the provision seemed, at first sight, to benefit individuals. But, as in that previous case, it could be argued that the trust was a trust for a purpose — namely, that the land had been placed on trust to be used as a sports and recreation ground.

Goff J, however, held that the trust was valid. In doing so, he held there was a distinction between two different types of purpose trust:

[a] a type of purpose trust where, although it does benefit an individual, the benefit is ‘so indirect or intangible … as not to give those persons any locus standi to apply to the court to enforce the trust’.39 In such a case, the purpose trust would fail since it would infringe the beneficiary principle. There would be, in practical terms, no-one who had sufficient authority to ensure the trustees honoured the terms of the trust as it could not be said that any beneficiary directly benefited enough from the trust to be able to take court action; and

[b] a type of purpose trust which will be enforced by the court because the trust is ‘directly or indirectly for the benefit of an individual or individuals’.40 Goff J felt that this type of purpose trust was ‘outside the mischief of the beneficiary principle’.41

The beneficiary principle existed to ensure that there was someone who could force the trus-tees to honour the terms of the trust. In this trust, Goff J believed that the court could force the trustees to administer the trust in the two ways fundamental to the trust’s existence:

[a] by restraining any use of the land which the court felt was improper; and/or

[b] by ordering the trustees to allow the employees and such other persons to use the land as a recreation or sports ground.

Who were the beneficiaries in Re Denley’s Trust Deed?

The result reached by Goff J in Re Denleys Trust Deed was perhaps the right one on the facts. It enabled Mr Denley’s wish that the land be left to a club for the benefit of others to be carried out. Yet the decision in the case is not without difficulty.

As will be seen in Chapter 10, the rule in Saunders v Vautier42 enables all adult beneficiaries, provided they are of sound mind and together absolutely entitled to the trust property, to join forces to bring the trust to an end. Who could bring the trust to an end if they so desired in Re Denley’s Trust Deed?

Goff J accepted the first group of people, the employees of the company, were correctly regarded as beneficiaries. He held that the second group of people were the objects of a power of appointment. As discussed in Chapter 2 , such people have a hope of being chosen to be able to benefit from the power and only once chosen do they became full beneficiaries of the trust.

The only people who could bring the trust to an end in Re Denley’s Trust Deed would be those people who fell within the first category of beneficiaries — the employees. Those who fell within the second category — anyone else whom the trustees may permit to use the land — would not be beneficiaries unless and until they were so chosen by the trustees to benefit from the trust.

The consequence this has is that all of the beneficiaries in the first category could bring the trust to an end under the rule in Saunders v Vautier because only they would (together) be absolutely entitled to the trust property. This cannot have been Mr Denley’s intention when setting up the trust. As those in the second category may not yet have all been chosen, they would not be classed as beneficiaries and therefore would have no right to bring the trust to an end.

Any such action by the employees would mean the employees would defeat the purpose for which the land had been left on trust, which was not only to benefit them but also anyone else that the trustees decided could use the land. The settlor’s wishes in setting up the trust would then be ignored. Such a result would be surprising, but such a consequence appears to be the logical result of the decision in the case.

The decisions in Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales and Re Denley’s Trust Deed seem to be contradictory. The first followed traditional jurisprudence in holding that a trust for purposes was void, whilst the second took a more subtle approach, in finding that there could be two types of purpose trust. Where there were sufficiently defined people who could benefit from the purpose trust so that it could be said that they would have standing to bring a court action to enforce the trust against the trustees, such purpose trust would be valid.

The approach in Re Denley’s Trust Deed was applied by the High Court in Re Lipinski’sWill Trusts.43 This suggests that the more modern approach is indeed to recognise purpose trusts if it can be said that they benefit sufficiently well-defined individuals.

Re Lipinski’s Will Trusts concerned the will of Harry Lipinski, in which he left half of his residuary estate on trust for the Hull Judeans (Maccabi) Association. The Association was a club which provided social, cultural and sporting activities for young people of the Jewish faith in Hull. The Association was obliged by the terms of the will to use the money for constructing new buildings and/or making improvements to its existing buildings. Clearly, this was a trust for a purpose and so would, at first glance, seem to be void.

Applying Re Denley’s Trust Deed, Oliver J held that the trust was valid. He made the same distinction in terms of the two types of purpose trust as Goff J had done:

There would seem to me to be, as a matter of common sense, a clear distinction between the case where a purpose is prescribed which is clearly intended for the benefit of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries … and the case where no beneficiary at all is intended (for instance, a memorial to a favourite pet) or where the beneficiaries are unascertainable …

A trust for the purpose of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries would be valid; a trust where no beneficiary was intended at all or where the beneficiary was unascertainable would generally be void.

The trust in the case was valid. The members of the Association were entirely ascertainable — they were the people who had joined the Association. They had the necessary connection with the Association that they would have been able to bring court action against the trustees of the Association had the trustees failed to administer the trust correctly.

In summary, the more recent cases of Re Denley’s Trust Deed and Re Lipinski suggest a more pragmatic approach is taken by the court in order to recognise some purpose trusts. Such an approach is to be welcomed, since it upholds the settlor’s intentions in declaring the trust. The decision in Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales will, however, still stand if the purpose of the trust has no ascertainable beneficiaries (i.e. it is of an abstract nature and it cannot be said that any beneficiary at all has any standing to enforce the trust before the court).

Offshore trusts

Certain trusts may be governed in offshore jurisdictions. These generally involve islands located in various parts of the world whose residents and organisations based there may enjoy lower taxation than, say, in England and Wales. Trusts established in such jurisdictions may benefit from those lower rates of taxation.

The Cayman Islands has been at the forefront of developing a trust known as the ‘Special Trusts Alternative Regime’ or ‘STAR’ trust. These trusts, which must be created in writing containing a declaration stating that the law is to apply to them, allow trusts to be established specifically for a purpose to be carried out. The trust may also be for the benefit of people or it can be for the benefit of a mixture of persons and purposes. The trust may be charitable or non-charitable.

Whilst specifically designed to permit non-charitable purpose trusts, then, STAR trusts still have one eye to the beneficiary principle in English law. All STAR trusts must have an ‘enforcer’ as one of their parties, in addition to the settlor and trustee(s). The central idea in the beneficiary principle is that there has to be someone who can compel the trustees to perform the trust. In a STAR trust, regardless of whether there are individual beneficiaries, the person whose task it is to compel performance of the trust is the enforcer. The beneficiaries, in fact, may not themselves enforce the trust unless they happen to be the enforcers of the trust as well. It is the presence of the enforcer which deals with the same aim as the main reason for the beneficiary principle in English law.

In order to keep the trustees on the straight and narrow road of administering the trust correctly, s 9 of the Special Trusts Alternative Regime states that the enforcer enjoys the following rights:

[a] to bring applications to court to enforce the trust; and

[b] to be advised about the terms of the trust and to have information about the trust given to them. The enforcer may also inspect and take copies of the trust documents.

The STAR trust is gaining in popularity in offshore jurisdictions. The Channel Island of Jersey has adopted a similar trust regime to STAR in the Trusts (Amendment No. 3) (Jersey) Law 1996 and it is likely that Guernsey will follow the lead set by Jersey in the near future.

English law, however, seems wedded to the beneficiary principle, albeit with significant exceptions applying on a legal and practical level on a day-to-day basis.

Unincorporated associations

Re Lipinski’s Will Trusts showed that a trust for the purposes of an unincorporated association could be valid. There has been much debate over the years as to how unincorporated associations can hold their property.

First, a preliminary issue: what is an unincorporated association? In Conservative and Unionist Central Office v Burrell,44 Lawton LJ defined it as:

two or more persons bound together for one or more common purposes, not being business purposes, by mutual undertakings each having mutual duties and obligations, in an organisation which has rules which identify in whom control of it and its funds rests and upon what terms and which can be joined or left at will.45

In straightforward terms, an unincorporated association is a club or society, which has members. We are considering here such associations which have not been established for charitable purposes. Associations established for charitable purposes will enjoy charitable status (see Chapter 15) and since they enjoy charitable status, can validly hold property. Non-charitable associations would seem to be examples of purpose trusts: they are clubs set up for a purpose in which officers of the club hold property. These types of purpose trust are permitted in English law, as an exception to the beneficiary principle.

The principle of how an unincorporated association can hold property was considered by Cross J in Neville Estates Ltd v Madden.46 He believed that there were three possibilities:

[a] the property could be held between the members of the association as joint tenants in equity. That would mean that any member could sever his share and claim a part of it as his own personal property. This would seem to be a little odd and go against the concept that all of the property in total is held for the purposes and benefit of the association;

[b] the property could be a gift to the existing members of the association and be governed by the association’s rules. Such rules formed a contract between the members. This would have the result that each member’s share would pass to the other members on his death or resignation from the association. Each member would not be allowed to claim it for himself personally; or

[c] the property could be given to the association on the basis that it was to be given for the association itself and not for the members‘ benefit. A gift of property on this basis would be void since it would constitute a purpose trust.

This discussion was taken further by Brightman J in Re Rechers Will Trusts.47 The case concerned the will of Eva Recher. She left part of her residuary estate to an organisation she described as ‘The Anti-Vivisection Society, 76 Victoria Street, London, SW1’. The issue for the High Court was whether such a trust could be valid. It seemed at first sight that such a trust would be void as it was a trust for the purposes of the society, instead of ascertained or ascertainable individuals.

Building on Cross J’s analysis in Neville Estates Ltd v Madden, Brightman J summarised counsels‘ arguments that suggested that a gift to an unincorporated association could be held in four possible ways:

[a] as a gift to the existing members of the association. The present members would need to hold their shares in equity as joint tenants or tenants in common. If they held the gift as tenants in common, then each member could take his share of the association with them if they decided to leave. The same result would be reached if they held their shares as joint tenants, as a leaving member could decide to sever their share. Brightman J did not think Mrs Recher’s intention in this case was to benefit the members of the association personally in this way so that they could personally take an individual benefit from her gift. Instead, she had decided to benefit the association itself. Cases which fall in this category are rare as the donor of the gift (like Mrs Recher) does not usually wish to benefit the members of the association personally;

[b] as a gift to all of the members of the association, both now and in the future. Yet as Brightman J pointed out, such a gift would fail since it would infringe the rules against perpetuity as potentially the effects of the gift would never come to an end. Construing the gift in this way would, again, defeat the testatrix’s intentions of wishing to benefit the association;

[c] as a gift to the trustees or other officers of the association so that they might hold the gift on trust for the purposes of the association. This type of gift too would fail since it would, as a purpose trust, breach the beneficiary principle; or

[d] as a gift to the members of the association in equity but on the basis that the gift is held according to the rules of the association. Individual members would not be able to take their share if they left the association and their property would simply accrue to the other members if they died or resigned from the association. The rules of the association would form a contract between the members.

Brightman J held that the gift to the Association should be considered to be held on the basis of the fourth proposition, perhaps due to reasons of policy:

It would astonish a layman to be told that there was a difficulty in his giving a legacy to an unincorporated non-charitable society which he had … supported without trouble during his lifetime.48

Brightman J was guided by the concept that an association would be governed by a set of rules. Such rules would form a contract between the members of the association. As with any other contract, the one between the members could be varied even to the extent that the members could agree to wind up the association. The gift to the association should be seen here to be a type of gift to the members, to be held on the terms of the contract between them. The money should be seen to be an addition to the association’s funds.

There is now a presumption that this fourth category is the one that governs gifts to unincorporated associations following the effective approval of Re Recher’s Will Trusts by the House of Lords in Universe Tankships Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers’ Federation (The Universe Sentinel).49

But, surely this category infringes s 53 (1)(c) of the Law of Property Act 1925 as when one member leaves, their share accrues to the new member joining. But, to comply with s 53(1)(c), should there not be a requirement that the assignment of this equitable interest should be in writing?

The logical extent of the contract between the members was that the members could, if they so desired, agree between themselves to close the association permanently. In that event, the members would be entitled to divide the assets of the association between themselves. Brightman J thought that whilst such a possibility was remote and Mrs Recher undoubtedly would not have known that such a possibility existed when she wrote her will, such a conclusion had to stand as the logical consequence of finding that the gift was held on the basis of a contract between the association’s members.

In fact, the consequence that the members of the association had to have the right to divide the association’s funds between themselves was of vital significance. This prevented the gift to the association being void for infringing perpetuity, as Cross J explained in Neville Estates Ltd v Madden.50

Any gift to an unincorporated association can, therefore, be valid provided that it is seen to be a gift not to the association for its purposes but instead as a gift to its members. To be seen as a gift to its members, on the terms of the contract between them, the members have to have the right to dissolve the association and split its assets between them.

If the members cannot divide the association’s assets between themselves then it will not be possible to say that the gift is to the members but instead the gift will be to the association itself. Such a gift will infringe the beneficiary principle and will be void, as illustrated by Re Grant’s Will Trusts.51

Wilson Grant was a long-term member of the Labour Party. By his will, he left all his property to the ‘Labour Party property committee for the benefit of the Chertsey Headquarters of the Chertsey and Walton Constituency Labour Party’. This Chertsey and Walton Constituency Labour Party was an unincorporated association. Crucially, the rules of the association provided that its rules could only be changed to ensure that they reflected those made by the central Labour Party at its annual party conference or by its National Executive Committee. The actual members of the association did not have the power to alter the rules of the association by their own choice.

Vinelott J held that Mr Grant’s property could not be said to have been left to the members of the Chertsey and Walton Constituency Labour Party with the intention that they should benefit from it on the basis of their contractual membership. The members did not have complete freedom to do as they liked with property left to them, since their rules were governed by the national Labour Party. This meant that, for example, the national Labour Party could have requested that the Constituency Party’s property be transferred to it and the members would not have had the contractual right to resist such a transfer. The members also had no contractual right to divide the property amongst themselves in equity. The gift from Mr Grant was void. It was a trust for the purposes of the Labour Party and infringed the beneficiary principle.

Re Grant’s Will Trusts illustrates that not every gift to an unincorporated association will be construed as a gift to its members according to the terms of their contractual relationship with each other. The contractual relationship must be a genuine one, giving the members the ultimate freedom to dispose of the property if they so choose. The default principle from Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales will apply if this is not the case.

This means that a gift left on trust for the association’s purposes will rebut the fourth category of how the property should be held and so the settlor will have (inadvertently) created a private purpose trust.

Dissolution of an unincorporated association

The issue which must be considered now is who owns the property of an unincorporated association when it is dissolved. It should be borne in mind that often the cases concern a mixture of donations, where the property of the association has been given by both members and non-members.

Donations primarily by non-members

The first modern case on funds given by predominently non-members was Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund.52

The facts concerned a serious road traffic accident in December 1951, when a bus ran into a column of Royal Marine cadets marching along a road in Gillingham, Kent. Twenty-four of the cadets were killed and a number of the others were injured. The mayors of the neigh-bouring towns launched an appeal through the Daily Telegraph for donations to offset the cost of the funerals of those cadets who had died and to help provide care for those who had been left disabled. A total of nearly £9,000 was raised. Most of the money had come from anonymous donors through street collecting boxes. Only £2,400 was spent from the money as the cadets pursued successful legal claims against the bus company for compensation.

The issue was what should happen to the surplus funds.

Making connections

The fund in Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund was not charitable as it had no charitable purpose (as defined in law) and neither did it provide a general benefit to the public.

Had it been charitable, it is likely that the surplus money could have given instead to a charity with a similar object as the fund had. This is known as the cy-près doctrine and is discussed in Chapter 16.

The choice faced by Harman J was whether the funds should be returned to the donors under a resulting trust or instead be paid to the Crown as bona vacantia (ownerless property). He held that the donations should be returned to the original donors under a resulting trust.

Harman J stated that the general principle was that where money was held upon trust and the trust did not exhaust the whole of the money, it had to be returned to the original settlor under the doctrine of the resulting trust. This was based on the settlor not parting with the beneficial interest in the money. He parted solely with the legal title and only to the extent that his wishes were carried out — that the money was used for the purposes for which he gave it. If those purposes failed, the money had to be returned to him.

It made no difference that each donor was anonymous and could not be found. The resulting trust in his favour still existed. The money could not, as Harman J put it, ‘change its destination and become bona vacantia’.53 If the donor could not be found, the trustees had to pay the money into court and wait for the beneficiary to come forward.

The trustees did pay the surplus funds into court. The money remained there until the late 1990s when, eventually, the money that remained was spent on renovating the cadets’ graves and in constructing a new memorial to them.

The decision in Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund might well be seen to be a logical application of the resulting trust. But the difficulty with the decision of Harman J is two-fold. First, the decision leads to the practical problem that the money has to be returned to anonymous donors and must be paid into court until those donors come forward. Quite how an anonymous donor can remember, let alone prove, years after the event that they donated a sum into a street collecting box must be open to debate. The donations will (and, on the facts of the case, did) remain in the court’s control for decades after the court’s decision. Second, the imposition of a resulting trust — for, as Harman J admitted, it is imposed — goes against the donor’s intentions when they gave the money. When placing money in a collecting box, the donor never expects to see it again. It is odd that a trust can be imposed which entirely contradicts the settlor’s intentions.

Donations by both members and non-members

The imposition of a resulting trust was considered again by Goff J in Re West Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts.54 This case considered funds contributed by both members and non-members.

Here the West Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund existed to provide benefits to widows, children and dependent widowed mothers of officers of the West Sussex Constabulary police force. On 1 January 1968, the force was merged with other forces to form a singular Sussex Constabulary. The trustees brought an action seeking the court’s approval to its scheme to wind up the unincorporated association pursuant to a meeting of its members in June 1968. Goff J held that that meeting was abortive as by that time, the association had no members given that the force had already been merged. The issue was what was to happen to the property of the association.

The association had raised its funds by four methods:

[a] members’ subscriptions;

[b] entertainment proceeds;

[c] collecting boxes; and

[d] donations from other parties, including legacies from others’ wills.

The members of the association argued that the doctrine of the resulting trust should govern the ultimate destination of the funds. This would mean that money raised by the first method would be held on trust for the present (and possibly past) members.

Goff J rejected this proposition. He reiterated that the basis of the holding of property between members of an unincorporated association was the law of contract, not trusts. Contractually, all members who had died had received their contractual entitlement from the association, either because their widows and dependants had received benefits or because they did not leave a widow and/or dependant. The present members held the property of the association on a contract between themselves so it was not appropriate for a resulting trust to apply when the association was dissolved. The subscriptions had to go bona vacantia to the Crown. Goff J left open the possibility of the surviving members making a claim that the contract had been frustrated or, alternatively, that there had been a total failure of consideration,55 when the association was dissolved. Goff J then dealt with the contributions from non-members.

For the money raised from entertainment, he chose not to follow the judgment of Harman J in Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund56 and held that there was no resulting trust of the money to those who made the contributions. He held that in this situation again, the relationship between the donor and the association was one based on the law of contract, not trusts. The donor had donated money in return for being entertained not on the basis of any trust. The donor had, once again, received their contractual entitlement by being entertained.

Donors who had given the money through street collecting-boxes were taken to have parted with all property in the money once they placed it in the box. Goff J followed Upjohn J in Re Hillier’s Trusts,57 who decided that such a donor had no intention of having the money returned to him if there was a surplus after the object of the association had been achieved. This remained the case even if the association’s objects had never been achieved. When placing his donation in the street collecting box, the donor’s intention was to part entirely with all property in the money. As such, there was no room later to argue that he should have it returned to him under a resulting trust. Goff J quoted Denning LJ in the Court of Appeal in Re Hillier’s Trust58 who had explained the position with characteristic clarity that ‘[w]hen a man gives money on such occasion, he gives it, I think, beyond recall. He parts with his money out-and-out.’

The resulting trust doctrine was only appropriate for the fourth category of donations, by specific (traceable) donors, including legacies in wills. Such donations could be returned to them under a resulting trust on the basis that those donors could be seen to be giving a donation for a specific purpose. If that purpose failed, then the money should be held on resulting trust for them.

The decision in Re West Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts was distinguished by Walton J in Re Bucks Constabulary Widows’ and Orphans’ Fund Friendly Society (No. 2).59 The facts were similar to the Re West Sussex case in that funds were contributed to a scheme which benefited widows and orphans of the deceased members of the scheme who had worked as police officers. The fund was dissolved and the issue was what happened to the surplus.

Walton J adopted Brightman J’s analysis of how an unincorporated association held property in Re Rechers Will Trusts.60 The members held it between themselves according to the contract which existed between them — known as the rules of the association. It made no difference whether the members had contributed property to the association or it came from a non-member. A donation from a non-member would be treated as a gift to the association’s funds which would be held between the members according to the contract between them.

Given that the members held the property of the association on a contract between them whilst the association existed, it followed that when the association was dissolved, the assets of the society would continue to be held by that contract for the now former members. The funds were not ownerless property (bona vacantia) which had to go to the Crown: the members still owned the property of the association. The property had to be distributed to the members who were still alive. Deceased members could have no claim as their membership of the association would have terminated automatically on their death.

Walton J said that he was ‘wholly unable to square [the decision of Goff J in Re West Sussex] with the relevant principles of law applicable’ as far as the contributions from the members were concerned.

It is suggested that the decision in Re Bucks Constabulary is to be preferred over Re West Sussex and Re Gillingham Bus Disaster. It is surely beyond argument now that the law of contract governs the ownership of the property of an unincorporated association. It is, therefore, hard to see why this contract should terminate once the association was dissolved and either a resulting trust imposed or the concept of bona vacantia dictate the destination of the association’s property.

Walton J held that all members of the association should receive the property in equal shares. If the contract between the members (the rules of association) was silent on the issue, then all members of the fund had an equal entitlement to it.

Walton J considered what would happen to an association’s funds if the members of the association dwindled to just one. He thought that:

if a society is reduced to a single member neither he, nor still less his personal representatives on his behalf, can say he is or was the society and therefore entitled solely to its fund.61

In such a scenario, therefore, the society’s assets would become ownerless and had to go to the Crown as bona vacantia.

This last point has, however, been considered expressly by the High Court in Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney-General.62

Mrs Hanchett-Stamford was the last surviving member of the Performing and Captive Animals Defence League, an unincorporated association formed in 1914 in order to prevent the use of animals performing in circuses or in films. The League was not charitable as its objects were political in nature.

The League had had many members, particularly during the 1960s but slowly membership had declined to where the claimant was the only member. She was elderly and lived in a nursing home. The League, however, still had assets worth over £2 million. The issue was what would happen to the association’s property at this point.

Lewison J held that as the last surviving member of the association, the assets belonged to Mrs Hanchett-Stamford absolutely.

Lewison J rejected Walton J’s obiter view that, where an association had only one member remaining, its property could not belong to that member. Such a view led to an inconsistent conclusion which seemed to depend simply on chance as to how many members of the association remained:

It leads to the conclusion that if there are two members of an association which has assets of, say £2m, they can by agreement divide those assets between them and pocket £1m each, but if one of them dies before they have divided the assets, the whole pot goes to the Crown as bona vacantia.63

Such a conclusion could make no logical sense: the ultimate ownership of the money could not depend on the numbers of members of the association.

Lewison J restated that the assets of an unincorporated association belong to its members whilst they are alive. If the association is dissolved, those members are entitled to share in the assets of the property. This principle would not change if the number of members of the association fell to one.

In addition, Lewison J considered the application of Article 1 of the First Protocol of the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. This provides that ‘No one shall be deprived of his possessions except in the public interest and subject to the conditions provided for by law …’ He felt that if he was to decide the case other than by holding that Mrs Hanchett-Stamford was entitled to the assets of the association, there would be a breach of Article 1.

Lewison J’s views are, with respect, sensible. The views of Walton J in Re Bucks Constabulary on the notion that if the membership of an association fell to one the assets of that association should go to the Crown as bona vacantia were obiter and seemingly contradicted the logical principle that if the members hold the association’s property between them on the basis of a contract, it should ultimately make no difference at all quite how many members there are.

Summary

It therefore seems that the following conclusions may be reached about the destination of property when an unincorporated association is dissolved:

[a] that the association’s trustees hold the property on trust for the members during its existence. The equitable interest held by the members is held on the basis of the contract between them;

[b] funds contributed to the association (if given by the members or by anonymous donors) should be seen as given to the members to be held on the terms of their contract on a once-and-for-all basis;

[c] on a dissolution of the association, subject to any rule of the association to the contrary, the funds should be returned to the surviving members in equal shares; and

[d] it makes no difference if there is only one surviving member of the association.

Points to Review

You have seen:

![]() What the beneficiary principle is: how English law generally insists that trusts must be for the benefit of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries;

What the beneficiary principle is: how English law generally insists that trusts must be for the benefit of ascertained or ascertainable beneficiaries;

![]() How the beneficiary principle is an essential part of an express, non-charitable trust in English law. Exceptions do exist but these exceptions are self-contained and are usually only permitted where there is at least someone who has standing to enforce the trust against the trustees; and

How the beneficiary principle is an essential part of an express, non-charitable trust in English law. Exceptions do exist but these exceptions are self-contained and are usually only permitted where there is at least someone who has standing to enforce the trust against the trustees; and

![]() How STAR trusts are a comparatively new device which allow trusts to be established for a purpose without any ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary. If such trusts were to be embraced by English law, there would be a great number of permitted purpose trusts. Such trusts are, however, yet to be considered by the English courts or Parliament in any real depth. The beneficiary principle, as we have seen, seems too well entrenched to be subjected to the STAR regime displacing it.

How STAR trusts are a comparatively new device which allow trusts to be established for a purpose without any ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary. If such trusts were to be embraced by English law, there would be a great number of permitted purpose trusts. Such trusts are, however, yet to be considered by the English courts or Parliament in any real depth. The beneficiary principle, as we have seen, seems too well entrenched to be subjected to the STAR regime displacing it.

Making connections

This chapter considered another piece of the jigsaw in trust formation and, specifically, in the requirements to a valid declaration of trust.

There is a close connection between the concept of there being an ascertained or ascertainable beneficiary in a trust and certainty of object. In both cases, there has to be someone who should benefit from the trust so that, in turn, that person can enforce the trust against the trustees if necessary. That circular system enables the trust to be administered correctly since it provides an in-built control over the trustees‘ powers.

The rules against perpetuity have also been hinted at during this chapter. These are considered in detail in the chapter on the companion website. The rule of perpetuity which addresses inalienability, that provides that the property must pass to the beneficiaries within a certain time, is of particular relevance.

Chapter 7 discusses the final requirement to form an express trust: that the trust must be constituted.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

The best reading is contained in the primary sources listed below. It is always good to consider the decisions of the courts themselves as this will lead to a deeper understanding of the issues involved. A few secondary sources are also listed, which you may wish to read to gain additional insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Primary sources

Re Astors Settlement Trusts [1952] Ch 534.

Re Denley’s Trust Deed [1969] 1 Ch 373.

Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232.

Re Grants Will Trusts [1980] 1 WLR 360.

Re Horley Town Football Club [2006] EWHC 2386 (Ch).

Leahy v Attorney-General for New South Wales [1959] AC 457.

Re Recher’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 526.

Secondary sources

Simon Baughen, ‘Performing animals and the dissolution of unincorporated associations: The ‘contract-holding theory’ vindicated’ (2010) Conv 3, 216–233. This article reviews how an unincorporated association holds property and how its property should be distributed when it is wound up. It also looks at when assets can be distributed to non-members.

James Brown, ‘What are we to do with testamentary trusts of imperfect obligation?’ (2007) Conv Mar/Apr 148–160. A look at trusts of imperfect obligation and their interaction with the rules against perpetuity together with a practical demonstration of the extent to which such trusts are used today.

Simon Gardner, ‘A detail in the construction of gifts to unincorporated associations’ (1998) Conv Jan/Feb 8–12. This article was written in response to that by Professor Paul Matthews (below) and looks specifically at the relevance of the donor’s intentions to how the gift to the unincorporated association should be construed. You are advised to read Professor Matthews’ article before this one.

B Heape, ‘Non charitable purpose trusts in the Channel Islands’ (2008) JLR February. An interesting look at how Jersey and Guernsey treat private purpose trusts.

Alastair Hudson, Equity & Trusts (7th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) ch 4.

Paul Matthews, ‘A problem in the construction of gifts to unincorporated associations’ (1995) Conv Jul/Aug 302–308. This considers the decision in Re Denley and compares how a gift may be given to the members of an association with it being given to the association itself, as an addition to its funds.

Mohamed Ramjohn, Text, Cases and Materials on Equity & Trusts (4th edn, Routledge-Cavendish, 2008) ch 13.

1 See the comment of Viscount Simonds in Leahy v A-G for New South Wales [1959] AC 45 7 at 478.

2 Re AstorsSettlement Trusts [1952] Ch 534.

3 Bowman v Secular Society [1917] AC 406.

4 Ibid at 441.

5 Re AstorsSettlement Trusts [1952] Ch 534 at 541.

6 Ibid.

7 Bowman v Secular Society [1917] AC 406.

8 Morice v Bishop of Durham 9 Ves 399 at 405; 32 ER 656.

9 This topic is addressed in depth on the companion website.

10 See Chapter 15.

11 Roxburgh J in Re Astors Settlement Trusts [1952 ] Ch 53 4 at 541.

12 Re Astor’s Settlement Trusts [1952] Ch 534.

13 Ibid at 547, quoting from Underhill’s Law of Trusts, 8th edn, p 79.

14 Re Hooper [1932] 1 Ch 38.

15 Pirbright v Salwey [1896] WN 86.

16 Re Hooper [1932] 1 Ch 38 at 40.

17 Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232.

18 Ibid at 250–251.

19 Ibid.

20 Bourne v Keane [1919] AC 815.

21 West v Shuttleworth 2 My & K 684; 39 ER 1106.

22 Bourne v Keane [1919] AC 815 at 861.

23 Re Hetherington [1990] Ch 1.

24 Ibid by Sir Nicolas Browne-Wilkinson V-C at 7.

25 ReWhite [1893] 2 Ch 41.

26 Re Banfield [1968 ] 1 WLR 846 .

27 Re Hetherington [1990] Ch 1 at 10.

28 ReWeAgwtxd [1915] 1 Ch 113.

29 Ibid at 122.

30 Re Dean (1889) LR 41 ChD 552.

31 Re Endacott [1960] Ch 232.

32 Re Thompson [1934] Ch 342.

33 Ibid at 344.

34 Hunting Act 2004, s 1.

35 Re Khoo Cheng Tern [1933] 2 MLJ 119.

36 Ibid at 122.

37 Although, on the facts, s 37D of the Conveyancing Act 1919–1954 (New South Wales, Australia, legislation) saved the provision in the case itself.

38 Re Denley’s Trust Deed [1969] 1 Ch 373.

39 Ibid at 383.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid.

42 Saunders v Vautier (1841) 4 Beav 115; 49 ER 282.

43 Will Trusts [1976] 3 WLR 522.

44 Conservative and Unionist Central Office v Burrell [1982] 1 WLR 522.

45 Ibid at 525.

46 Neville Estates v Madden [1962] Ch 832.

47 Re Recher’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 526.

48 Ibid at 536.

49 Universe Tankships Inc of Monrovia v International Transport Workers’Federation (The Universe Sentinel) [1983] 1 AC 366.

50 Neville Estates Lti v Madden [1962] Ch 832 at 849.

51 Re Grants Will Trusts [1980] 1 WLR 360.

52 Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund [1958] Ch 300 (affirmed at [1959] Ch 62 (CA)).

53 Ibid at 313.

54 ReWest Sussex Constabulary’s Widows, Children and Benevolent (1930) Fund Trusts [1971] Ch 1.

55 Nowadays this would be seen as a restitutionary claim as opposed to a claim in the law of contract.

56 Re Gillingham Bus Disaster Fund [1958] Ch 300.

57 Re Hillier’s Trusts [1954] 1 WLR 9.

58 Re Hillier’s Trust [1954] 1 WLR 700 at 714.

59 Re Bucks Constabulary Widows’and Orphans’Fund Friendly Society (No. 2) [1979] 1 WLR 936.

60 Re Recher’s Will Trusts [1972] Ch 526.

61 Re Bucks Constabulary Widows’and Orphans’Fund Friendly Society (No. 2) [1979] 1 WLR 936 at 943.

62 Hanchett-Stamford v Attorney-General [2009] Ch 173.

63 Ibid at 185.