Chapter 17

Equitable Remedies and Proprietary Estoppel

Chapter Contents

This chapter concerns two topics: the general remedies that equity offers to the legal system together with the proactive remedy that particularly concerns the recovery of land or shares: proprietary estoppel.You may have studied the topic of equitable remedies in contract law so, hopefully, this chapter should act as something of a reminder to you about these principles.

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

![]() the nature of the general remedies that equity offers and how they each achieve a different objective;

the nature of the general remedies that equity offers and how they each achieve a different objective;

![]() tthe ingredients required to establish a successful claim in proprietary estoppel; and

tthe ingredients required to establish a successful claim in proprietary estoppel; and

![]() tthe flexibility of proprietary estoppel in offering a range of remedies should a claimant establish a successful cause of action.

tthe flexibility of proprietary estoppel in offering a range of remedies should a claimant establish a successful cause of action.

Equitable Remedies

The common law offered a ‘rough and ready’ remedy for a successful claimant: damages. This remedy continues to this day so that, for example, a claimant suing for breach of contract will be awarded damages with the aim of placing him in the position he should have been in had the contract been honoured and not breached.1 The common law remedy of damages is, of course, good for providing compensation to right a wrong, but it is a poor remedy to try to pre-empt a wrong from initially occurring.

Equity developed a number of different remedies which are designed to be proactive instead of reactive, as damages at common law. Moreover, equitable remedies attempt to give the claimant a more tailored remedy than common law damages. As Lord Selbourne LC put it in Wilson v Northampton & Banbury Junction Railway Company,2 equitable remedies exist ‘to do more perfect and complete justice’ than common law damages.

Equitable remedies are only available at the court’s discretion and to claim an equitable remedy, the claimant must show that common law damages will not be an adequate remedy in their own right. Equity, of course, also developed its own version of damages, called equitable compensation, but this has been discussed in Chapter 12 and will not be considered further here.

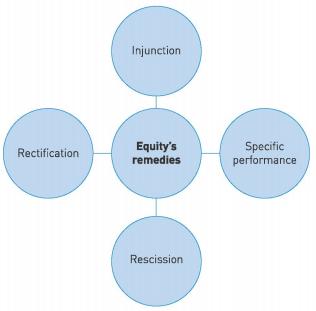

The remedies equity offers are illustrated in Figure 17.1 (overleaf).

Each of these remedies must be considered.

Injunction

There are five main types of injunction: prohibitory, mandatory, quia timet, search orders and freezing orders. All can be awarded on an interim or a permanent basis.

An interim (formerly ‘interlocutory’) injunction is awarded before the main trial of the claim occurs and, as such, is of a temporary nature. If an interim injunction is to be granted, the court will require an undertaking from the claimant that (i) he will pay the defendant damages if it turns out at trial that the claimant had no basis to restrain the defendant by way

of an injunction and (ii) as a result of the injunction being granted, the defendant has suffered loss. In American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd,3 Lord Diplock said the court was always trying to balance two competing interests in awarding an interim injunction:

[a]the protection the claimant needed and which would not be compensated adequately by the award of damages at a later trial; and

[b]the fact that granting an interim injunction deprived the defendant of being able to exercise his legal rights (by, say, continuing to trade in a particular product) which would not be adequately compensated by the claimant’s undertaking to pay him damages if the defendant were to be successful at trial.

A permanent injunction, as the name suggests, is of a permanent nature and is awarded to a successful claimant after a trial of the claim.

An injunction is used to enforce a legal or equitable right. As Lord Denning MR said in Mareva Compania Naviera SA v International Bulkcarriers SA; The Mareva,4 ‘[t]he court will not grant an injunction to protect a person who has no legal or equitable right whatever’.

Prohibitory injunction

A prohibitory injunction is designed to prevent a party from undertaking an action. This type of injunction was considered by Lord Diplock in American Cyanamid Co v Ethicon Ltd5. The case concerned a patent.

Glossary — A patent

A patent is a term from the law relating to intellectual property. If you hold a patent, you enjoy a period of time in which you have the monopoly over your invention. No-one else may compete directly with you and market a copy of your hopefully lucrative invention.

The claimant company had the benefit of a patent over a type of surgical suture. The defendant company was in the process of launching a competitor suture into the British market. The claimant sought an interim injunction preventing it from doing so, claiming that the defendant’s suture infringed its patent. The High Court awarded the injunction, but the Court of Appeal reversed it, holding that the claimant’s patent had not been infringed. The claimant appealed to the House of Lords. The House of Lords granted the injunction.

The only substantive opinion was delivered by Lord Diplock. He said that in deciding to grant an interim injunction, the court had to be satisfied that ‘the claim is not frivolous or vexatious, in other words, that there is a serious question to be tried’.6 The court should go no further than this: in particular, the court’s task was not to try to decide which party would succeed at trial as this involved relying on untested witness statements.

Provided the court was satisfied that there was a ‘serious question to be tried’, the court then had to consider whether the ‘balance of convenience’7 meant that the injunction should be granted or refused. Lord Diplock set out the following two principles:

[a]if it seemed that the claimant would succeed at trial but damages would compensate him adequately, the injunction should be refused; but

[b] if damages would not be an adequate remedy, but it seemed likely that the defendant would succeed at trial and be adequately compensated by the claimant’s undertaking to pay him damages, the court should normally grant the injunction.

The key to these principles is whether damages would be an adequate remedy for the claimant at trial. If damages are an adequate remedy, no injunction should be awarded. Conversely, if they are not, the injunction should be granted.

If the court was in doubt as to whether damages were an adequate remedy, the ‘balance of convenience’ test applied. One party was, of course, always liable to suffer disadvantages from an interim injunction being granted. The extent of the disadvantages suffered were a ‘significant factor’8 in deciding where the balance of convenience lay over whether or not to grant the injunction. The court could, provided the parties‘ arguments over the extent of their disadvan-tages were equal, take into account how strong each of their arguments were in each party’s witness statements. But the court was to go no further than this and, particularly, was not conduct a trial of the action.

The trial judge had taken into account such factors that the defendant’s sutures were not yet in the UK market and they had no ongoing business that an interim injunction would prevent from continuing. This meant that the granting of an injunction against the defendant would not mean factories closing and a workforce being denied employment. The claimant was in the process of establishing a growing market in the UK of this particular type of suture. Had the defendant been able to market its product before the trial of the action to ascertain if the patent had been infringed, the claimant’s opportunity to take a share of that market would have been stunted. These factors indicated that, on the balance of convenience, the trial judge’s injunction should be restored.

Although the case concerned an interim injunction, many of Lord Diplock’s views may apply equally to a permanent injunction. The key test must surely be the same for both types of prohibitory injunction: Are damages a remedy that will adequately compensate the claimant? If not, the injunction should be granted; if they are, the injunction should be refused.

The injunction, especially the prohibitory injunction, has been much in the news recently, due to the rise of the so-called ‘super-injunction’. The grant of such an injunction is usually requested by well-known celebrities to prevent the press from publishing stories about them. The injunctions have been termed ‘super-injunctions’ because the court has, on occasions, restricted the press from reporting which celebrity has been granted an injunction and the subject-matter of the injunction. Well-known celebrities who have had super injunctions granted in their favour include the footballer Ryan Giggs and the TV personality Jeremy Clarkson.

The danger with super-injunctions is, of course, that they infringe the free reporting of legal news stories and, due to the fact that a claimant must give an undertaking to pay damages, are restricted to the wealthy who can afford to give such an undertaking.

Do you think that the super-injunction is really an example of a ‘sledge-hammer to crack a nut’?

Mandatory injunction

A mandatory injunction compels performance of an obligation. A comparison between prohibitory and mandatory injunctions, together with interim and final injunctions, was made by Megarry J in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham.9

The claimant had built a large number of houses in Caerphilly, South Wales. The estate was laid out in an ‘open plan’ style, which meant that each house owner had covenanted not to construct a fence, or any other erection, in front of the building line of each house. The problem was that Welsh mountain sheep and horses began to graze in the gardens of the properties. The defendant constructed a fence to prevent this occurring. The claimant sought an injunction to compel the defendant to remove the fence. The injunction sought was of a mandatory nature because it would have forced the defendant to comply with the obligation he had entered into not to construct a fence.

Megarry J refused to grant the injunction. This was largely due to the fact that the claimant had delayed for four months after issuing his claim before seeking the interim injunction it required. This suggested that even the claimant thought that the matter was not of an urgent nature.

Megarry J distinguished between prohibitory and mandatory injunctions. The latter were harder to obtain. The very nature of a mandatory injunction meant that it was used to correct what had happened in the past, so inflicting an additional cost on a defendant in having to take steps to undo his previous actions. A prohibitory injunction looked to the future: it sought to prevent future conduct from occurring and so imposed no cost onto a defendant to undo actions he had previously undertaken.

There were also theoretical differences between mandatory and prohibitory injunctions. A mandatory injunction obliged a defendant to carry out positive steps; a prohibitory injunction was an order to refrain from continuing an activity.

Megarry J said that in deciding whether or not to grant a mandatory injunction, the court would assess whether granting the injunction produced a ‘fair result’.10 The court would take into account how trivial the damage was to the claimant seeking the injunction, the detriment granting it would have on the defendant, as well as the benefit the claimant would gain from having the injunction granted. The general principle was that it was far harder to obtain a mandatory than a prohibitory injunction.

Further differences could be made between interim and final injunctions. Megarry J made the following points about an interim injunction:

[a]an interim injunction ‘for a mandatory injunction was one of the rarest cases that occurred’;11

[b]the case ‘had to be unusually strong and clear before a mandatory injunction will be granted’.12 That was because the court had to take into account that the injunction may not be awarded following a full trial of the claimant’s claim;

[c]before granting the interim mandatory injunction, the court had to ‘feel a high degree of assurance that at trial it will appear that the injunction was rightly granted’;13 and

[d]if an interim mandatory injunction was granted, it would not usually be extended at trial, as by then the defendant will have been ordered to take a particular step which, by the stage of trial, he should have normally taken. In contrast, a prohibitory injunction would usually be continued at trial for there would still be a purpose in preventing the defendant from continuing with his behaviour.

An injunction will not be granted where its effect would be to grant an order of specific performance if the court could not validly grant that order of specific performance. For example, specific performance will not be ordered to enforce a contract for personal services,14 as was shown in Page One Records Ltd v Britton.15

Here a pop group called ‘The Troggs’ engaged the claimant as their manager. Approximately two years later, the group sought to dismiss the claimant as their manager and appoint another manager in its place. The group’s argument was that the manager had breached its fiduciary duties to the group. The claimant applied for a mandatory injunction to compel the group to honour the contract between them (and, therefore, to prevent the group from using the services of the other manager) which was to last for a further three years.

Stamp J refused to grant the injunction. His judgment shows a lack of general sympathy with the group. In fact, the group had not demonstrated even a prima facie case that the manager had breached its contract. It was, in fact, likely that the claimant would have a successful claim for damages against the group for wrongfully terminating the contract between them. But that did not mean that the claimant could also claim a mandatory injunction.

Stamp J held that he could not grant an injunction where its effect would be to grant an order for specific performance of the contract if the particular contract could not be subjected to an order for specific performance. To grant such an injunction here would have that consequence. A contract for personal services cannot be subject to an order for specific performance, as it is tantamount to forcing a party to work for another which is akin to slavery. Granting a mandatory injunction here would have the same consequence: it would force the manager to work for the group.

The comments by Megarry J in Shepherd Homes Ltd v Sandham, together with the decision in Page One Records Ltd v Britton, provide a useful analysis of the court’s approach to mandatory and prohibitory injunctions. A mandatory injunction seems to be a rarely sighted creature, mostly due to the fact that its very nature imposes on the defendant a cost of undoing actions that he has already taken. The court is, in addition, wary of granting interim mandatory injunctions when the defendant may well succeed at trial of defending the claim for the injunction. It is unfair to compel a defendant to incur the additional costs of undoing his actions when he may successfully defend such a claim at trial.

Quia timet injunction

This Latin phrase means ‘because he fears’. This type of injunction is granted because the claimant can show that he fears that the defendant will take a particular course of action. An injunction to this effect was upheld by the Supreme Court in Secretary of State for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs v Meier.16

The defendants were travellers who occupied part of Hethfelton Wood, Dorset. The wood belonged to the Forestry Commission. The Forestry Commission sought a possession order to repossess the wood from the travellers, together with an injunction preventing them from returning to the wood to occupy it again.

The Supreme Court upheld the decision of the majority in the Court of Appeal to grant the injunction against the travellers returning to the wood. As Lord Neuberger MR put it:

where a trespass to the claimant’s property is threatened, and particularly where a trespass is being committed, and has been committed in the past, by the defendant, an injunction to restrain the threatened trespass would, in the absence of good reasons to the contrary, appear to be appropriate.17

The court, thought Lord Neuberger MR, was not bound not to grant the injunction simply because it believed that the injunction was unlikely to be enforced if it was breached. It was, he said, likely in this case that the two usual methods of enforcing the breach of an injunction — the seizing of the defendant’s property and/or the imprisonment of the defendant — were unlikely to happen here. That is because the defendants were unlikely to have significant assets and given that a number of defendants had young dependent children, imprisonment could be seen to be disproportionate to the breaking of the injunction. Nonetheless, this did not mean that the injunction had to be refused. The court could still take the view that the defendants would be more likely to refrain from further trespasses if the injunction was granted. The injunction might, in any event, act as a deterrent to the defendant from trespassing onto the claimant’s land as they might be afraid of being imprisoned if they breached the injunction.

Of course, the problem with this injunction was that it was likely that the court would not know the identities of some of the trespassers. This caused no difficulty for the Supreme Court.Lord Rodger, in particular, disagreed with the earlier view of Wilson J in Secretary of State for the Environment, Food & Rural Affairs v Drury18 that the injunction would be ‘useless’ as you could not ask the court to imprison a ‘probably changing group of not easily identifiable travellers’. There was no evidence here that an injunction against a potentially changing group would fail to work. It could be effectively served upon them, by being displayed in the wood, for example, so they would know about it.

Search orders (formerly Anton Piller orders)

This type of injunction enables a claimant to enter a defendant’s premises and search for documents if the claimant believes the defendant might destroy the documents before trial. This type of injunction was recognised by the Court of Appeal in Anton Piller KG v Manufacturing Processes Ltd.19

The claimant was a German company who manufactured computer components. The defendant was their English agent. It transpired that the defendant intended to disclose confidential information to two competitors of the claimant. The claimant sought an interim injunction to prevent this from occurring. They also sought an order permitting them to enter into the defendant’s premises, search for incriminating documents that they feared the defendant would destroy before trial and seize such material. The Court of Appeal granted the injunction and granted permission for the claimant to enter the defendant’s premises.

Lord Denning MR pointed out that the court’s order might look like a ‘search warrant in disguise’,20 but was at pains to explain that no court could grant an order which permitted a person to force their way into another’s premises without the latter’s consent. Instead, the order allowed the claimant to enter into the defendant’s premises. The defendant could refuse to give his permission to such an entry or could challenge the validity of the court order. If the order had been validly granted, the defendant risked being held in contempt of court for failing to comply with it.

Safeguards had to be applied when the claimant executed the court’s order. When serving the order on the defendant, the claimant had to be accompanied by his solicitor who, as an officer of the court, could ensure that the order was correctly executed. The defendant should be given the chance to consider the order and to take legal advice upon it. If the defendant refused permission to allow the claimant to enter his premises, the claimant could not force his way in.

Such an order as was granted in the case should only be made, according to Ormrod LJ, when three criteria are satisfied:

First, there must be an extremely strong prima facie case. Secondly, the damage, potential or actual, must be very serious for the applicant. Thirdly, there must be clear evidence that the defendants have in their possession incriminating documents or things, and that there is a real possibility that they may destroy such material before any application inter partes can be made.21

The Anton Piller order, then, is a temporary order requested by one party without notice to the other, to enter their premises, search for incriminating documents and seize them before the actual trial of the action occurs.

The essence of the Anton Piller order is now embodied in s 7 of the Civil Procedure Act 1997. The High Court may make an order permitting a party to enter into premises for the purposes of searching for evidence or to make a copy, photograph, sample or other record of such evidence.22 Whilst this is a statutory right enjoyed by claimants, it appears to leave the original Anton Piller order untouched.

Freezing orders (formerly Mareva injunctions)

Freezing orders are designed to prevent a party from dealing with his assets so as to prevent the other party from claiming them. As such, this is a type of interim injunction. It is granted to the claimant to prevent the defendant from dissipating his assets before the trial of the action can be heard. It is designed to stop the defendant from frustrating the litigation that the claimant is about to pursue.

The leading case remains the decision of the Court of Appeal in Mareva Compania Naviera SA v International Bulkcarriers SA; The Mareva.23

The facts concerned the charter of a ship, The Mareva. The claimant owners chartered it to the defendants. The defendants themselves sub-chartered it to the President of India. The President duly paid the charter fee to the defendants. The defendants, in turn, paid some of their charter fee but not all of it. The claimant claimed the unpaid part of the charter fee (![]() 30,800) together with damages for wrongful repudiation of the contract. The defendant had retained a sizeable sum in its bank in London and the claimant sought an interim injunction preventing the defendant from disposing of that money.

30,800) together with damages for wrongful repudiation of the contract. The defendant had retained a sizeable sum in its bank in London and the claimant sought an interim injunction preventing the defendant from disposing of that money.

Lord Denning MR held that the court had a very wide right to grant an injunction. This included applying for an interim injunction to force the defendant to retain money even though the claimant had not established that he was actually entitled to the money at trial. Lord Denning MR explained the injunction as follows:

If it appears that the debt is due and owing, and there is a danger that the debtor may dispose of his assets so as to defeat it before judgment, the court has jurisdiction in a proper case to grant an [interim] judgment so as to prevent him disposing of those assets.24

This was a ‘proper case’ for the injunction to be granted. The charterers had their money in a bank and they could have moved it to another country at any point, making it highly unlikely that, in practical terms, the owners would be able to recover the money owed to them. The injunction would be granted until a full trial of the claimant’s claim took place.

Since the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 came into effect, Mareva injunctions have been known as ‘freezing orders’. Rule 25.1(f) of the Civil Procedure Rules 1998 specifically provides that the court may now make a freezing order which has the effect of:

[a]restraining a party from removing from the jurisdiction assets located there; or

[b] restraining a party from dealing with any assets whether located within the jurisdiction or not.

This rule makes it clear that such an order can apply to assets even if they are not located within the jurisdiction. The extension of a Mareva injunction to assets located outside of the jurisdiction of the court25 was confirmed by the Court of Appeal in Derby & Co Ltd v Weldon (Nos 3 and 4).26 There the Court of Appeal held that it was not a prerequisite to the granting of a Mareva injunction that the defendant had to have assets within the jurisdiction.

The claimant alleged that the defendant had defrauded it in dealings in the cocoa market. At first instance, Sir Nicholas Browne-Wilkinson V-C had granted a worldwide Mareva injunction against a Luxembourg-based company defendant, but had refused to grant such an injunction against a Panamanian defendant. Neither company had any assets within the jurisdiction of the court. But Browne-Wilkinson VC believed that a Mareva injunction could ultimately be enforced under the European Convention on Jurisdiction and the Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters27 against the Luxembourg company, but there was no effective enforcement mechanism against the Panamanian company.

Lord Donaldson MR held that a Mareva injunction could be granted against foreign defendants and should be granted against both foreign defendants in this case. In deciding whether to grant a Mareva injunction, whether or not that injunction could be enforced abroad was not the primary consideration for the court. The essential point was that if a defendant refused to honour the Mareva injunction, he could be denied the right to defend the claimant’s claim at trial. This in itself was an effective enforcement mechanism against a defendant. Neither was it relevant that a defendant may have no assets. A Mareva injunction operated in personam against the defendant personally, so it was appropriate that it could be made against the defendant wherever he was in the world.

A freezing order may now, therefore, be made against a defendant who has assets located anywhere in the world. Indeed, the order would also seemingly apply against a defendant who appears to have no assets (although, if the claimant knows this, it is difficult to see why the claimant would seek the injunction initially).

Guidance as to when the court should permit a worldwide freezing order to be enforced was given by the Court of Appeal in Dadourian Group International Inc v Simms28 (these are known as the Dadourian guidelines). In delivering the judgment of the court, Arden LJ thought that there were eight guidelines that the court should take into account. These are:

[i]the granting of permission to enforce a worldwide freezing order should be ‘just and convenient’29 to ensure the worldwide freezing order is effective. In addition, it must be oppressive to the parties in the English proceedings or to third parties who might be joined into proceedings abroad;

[ii]the court needs to consider all relevant circumstances and options;

[iii]the court should balance the claimant’s interests with those of the other parties to the proceedings, including any party likely to be joined in the foreign proceedings;

[iv]the court should normally withhold its permission i f the claimant would obtain a better remedy in the foreign court than in Enland;

[v]the claimant’s evidence in support of his application should contain all necessary information to enable the court to make an ‘informed’30 decision. This would, for example, include evidence as to the law and practice of the foreign court;

[vi]the standard of proof required was that the claimant must show that there was a ‘real prospect’31 of assets existing within the foreign court’s jurisdiction;

[vii]there usually had to be a risk that the assets might be dissipated; and

[viii]usually the claimant should notify the defendant that he intended to seek the enforcement of the worldwide freezing order but in urgent cases, this could be omitted. In such a case, the defendant should be allowed the ‘earliest practicable opportunity’32 to have the matter reconsidered by the court.

These guidelines were not, as Arden LJ made clear at the end of her judgment, an exhaustive list. The court should consider any other issue which needed consideration in an individual case.

Specific performance

Specific performance is an order of the court to one party to a contract that it must adhere to the terms of a contract. An order for specific performance will be rarely granted, as normally damages at common law will be an adequate remedy in the event that the contract is breached. The claimant must show that damages are not an adequate remedy to invoke equity’s jurisdiction to grant an order for specific performance. To do that, the claimant usually has to show that the contract concerns unique property, where the payment of damages cannot adequately compensate the claimant for the defendant’s breach of contract.

As a general rule, an order for specific performance will not be granted if the court’s constant supervision is required in monitoring whether the order is implemented by the defendant: Co-operative Insurance Society Ltd v Argyll Stores (Holdings) Ltd.33

The defendant traded as ‘Safeway’ and had a supermarket in the Hillsborough Shopping Centre, Sheffield. The claimant was its landlord. The 35-year lease provided that the defendant would keep the supermarket open. Safeway operated the leading store in the shopping centre to which customers would be drawn. It was essential that the store continued to trade so that the landlord could attractively market the remaining units in the shopping centre to other potential business tenants. Unfortunately, the supermarket was loss-making, so the defendant decided to close it. The claimant applied for an order for specific performance, claiming that damages for the defendant’s breach of the lease would not be an adequate remedy. The Court of Appeal granted the order for specific performance, but this was reversed unanimously by the House of Lords.

Lord Hoffman confirmed that it had been the usual practice of the courts not to grant an order for specific performance (or a mandatory injunction) compelling a party to continue to run their business because such an order would require the court’s constant supervision. This would take the form of the claimant often coming to the court seeking the court’s further punishment of the defendant for breaching the order of specific performance. The only weapon of punishment open to the court would be to treat the defendant as being guilty of contempt of court. This sanction by the court was not, perhaps, appropriate for a corporate defendant who would have to waste time and money in running their business (at a loss) simply to comply with a court order.

In addition, the loss that the defendant incurs in continuing to run the business may be far greater than the detriment the claimant would suffer through the defendant breaching his contract with the claimant. The aim of the law of contract was not to punish the defendant in his wrong-doing but to give the claimant adequate (but no more) compensation for his loss. Requiring the defendant to continue to run a loss-making business was punishing him whilst not essentially compensating the claimant.

Lord Hoffman held that an order for specific performance should not be granted if it required a defendant to continue an activity over a period of time. On the other hand, it could be granted where it required the defendant to achieve a one-off objective. Specific performance had been ordered, for example, in relation to a tenant’s repairing covenants in a lease34 because the court just had to satisfy itself that the work had been carried out.

Lord Hoffman described the remedy of specific35 Certain types of contract can be considered where specific performance will, and will not, usually be granted. They are contracts concerning:

[a] thesaleofland;

[b] the sale of chattels;

[c] the sale of shares; and

[d] employment obligations.

The sale of land

The breach of a contract for the sale of land36 will normally merit an order for specific perform-ance being granted for it. Such a contract is made in English law when both parties exchange their own part of the contract. After that point, the contract is prima facie specifically enforceable if one party should breach the contract by refusing to sell the land to the other.

The rationale behind this is that all land is seen as unique. No amount of damages can adequately compensate a claimant if the defendant refuses to sell the land to him for the claimant cannot go and buy another identical piece of land on the open market.

The sale of chattels

A contract for the sale of chattels will be subject to an order for specific performance if the chattel is unique so that damages are not an adequate remedy for the buyer if the seller subsequently decides not to sell his property. This was decided in Falcke v Gray.37

Mr Falcke rented a house from Mrs Gray. It was a term of the contract that, at the end of the tenancy, Mr Falcke should have the opportunity to purchase two china jars for the total sum of £40. Mrs Gray was ignorant of their true value, but Mr Falcke was a dealer in such curiosities. Before the lease ended, Mrs Gray sold the jars to a third party for £200. Mr Falcke sought an order for specific performance of that contractual obligation, with the aim of securing the delivery from the third party of the jars.

The Vice-Chancellor confirmed that a court of equity would give an order for specific performance for a contract for the sale of chattels on the same basis as any other contract: if damages at common law were an adequate remedy, the claimant must be content with such a remedy. If damages were not an adequate remedy, the court of equity could order that the contract be specifically performed. Damages were an adequate remedy if the buyer could go into the market and purchase comparable items; if he could not, damages were not an adequate remedy. Here the contract was for the purchase of ‘articles of unusual beauty, rarity and distinction’38 so damages were not an adequate remedy for non-performance of the contract.

An order for specific performance would normally have been granted in the case, as the items were unique. On the facts, the order was refused as the claimant had not offered a fair price and in doing so, could not claim the assistance of a court of equity. After all, according to the equitable maxim,39 he who seeks equity must do equity. The claimant had not acted equitably in deliberately offering a non-competitive price and so specific performance was refused.

Section 52 of the Sale of Goods Act 1979 now contains a specific statutory provision enabling the court to grant an order of specific performance for specific or ascertained goods. Section 52(3) provides that the order may be ‘unconditional, or on such terms and conditions as to damages, payment of the price and otherwise as seem just to the court’. The section probably adds little to the pre-existing law on specific performance for the sale of specific or ascertained goods.

The sale of shares

In a contract for the sale of shares, whether an order for specific performance is likely to be awarded depends on whether damages would be an appropriate remedy. Again, this follows a similar principle to that already considered: if the shares are unique in nature, an order for specific performance is likely to be granted, as damages would not be an adequate remedy.

Shares in private limited companies are usually seen to be unique in nature. If the company is private, its shares are not freely traded on a stock market. This means that damages are not an adequate remedy should a contract for the sale of such shares be breached by the seller. As the shares are not available for sale on the open market, the buyer cannot use any damages awarded to purchase alternative shares.40

In contrast, shares in a public limited company are traded on the open market. This means that if a seller of a contract for the sale of such shares breaches the contract, damages are an adequate remedy for the buyer as the buyer can freely purchase alternative shares instead.

Employment obligations

Employment contracts are not usually subject to an order for specific performance. Section 236 of the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992 provides categorically that the court cannot make an order of specific performance or grant an injunction if its effect is to ‘compel an employee to do any work or attend at any place for the doing of any work’. Consequently, if an employee breaches his employment contract, the usual remedy for the employer is that of common law damages.

There are two reasons why contracts of employment are not susceptible to an order for specific performance or injunction. The first is that the court usually views an order that a party perform his employment obligations towards his employer as tantamount to slavery. As Fry LJ explained in De Francesco v Barnum:41

I have a strong impression and strong feeling that it is not in the interests of mankind that the rule of specific performance should be extended to forcing people to maintain permanent and continuous relations which they are unwilling to maintain. I think the courts are bound to be jealous in case they should turn contracts of service into contracts of slavery …

The second reason is more pragmatic: that it is difficult, if not impossible, for the court to judge whether an employee would be upholding any order for specific performance or injunction made against him, as Megarry J explained in C H Giles & Co Ltd v Morris:42

If a singer contracts to sing, there could no doubt be proceedings for committal if, ordered to sing, the singer remained obstinately dumb. But if instead the singer sang flat, or sharp, or too fast, or too slowly, or too loudly, or too quietly, or resorted to a dozen of the manifestations of temperament traditionally associated with some singers, the threat of committal would reveal itself as a most unsatisfactory weapon: for who could say whether the imperfections of performance were natural or selfinduced? To make an order with such possibilities of evasion would be vain; and so the order will not be made.43

The facts of the case concerned a contract for the sale of shares in a company called Invincible Policies Ltd to the claimant company. Invincible owned a subsidiary company, Trafalgar Insurance Co Ltd. A term of the contract was that Mr C Giles would be appointed as both the Managing Director of Invincible and as a director of Trafalgar. The entire share sale contract was eventually subject to an agreed order of specific performance made between the claimant and defendants. But the defendants then refused to appoint Mr Giles to be the director of both companies. Their defence was that an order for specific performance for a contract of employment had been granted by the judge and such an order should not have been made. The question for Megarry J was whether the presence of the employment clause in the overall contract prevented the court from making an order of specific performance for the whole share sale agreement.

Megarry J drew a distinction between ordering specific performance of a contract for personal services and for the overall contract for the sale of shares. Specific performance could be ordered for the contract as a whole, even though it could not be ordered for a particular provision of the agreement, because it related to personal services. The personal services element was simply one element of the overall contract and the balance lay in ordering specific performance of the entire agreement.

Rescission

Rescission is an equitable remedy which enables both parties to a contract to be restored to their pre-contract positions in the event that one party commits a repudiatory breach of contract. It is most often applied in cases where there has been a misrepresentation made by one party to the other before the contract was entered into or the contract was entered into as a result of duress or undue influence by the other party.

In order to rescind the contract, the general principle is that the claimant must make it clear to the defendant that he intends to rescind the contract or, if that is not possible, he must do some overt act to make his intention to rescind plain.44

Rescission may apply providing none of the bars to rescission themselves apply. The bars to rescission are:

[a]affirmation;

[b]laches;

[c]where restitutio in integrum is impossible; or

[d]where a bona fide purchaser of a legal estate for value without notice acquires an interest in the property.

Affirmation

The contract cannot be rescinded if the innocent party has affirmed it. Affirmation may be express or implied. Express affirmation occurs where the innocent party confirms categorically that he wishes to continue with the contract, notwithstanding the repudiatory breach that has been committed. Implied affirmation occurs where the innocent party does some act showing that he intends to continue with the contract, as occurred in Long v Lloyd.45

Stanley Long bought a second-hand lorry from the defendant.The defendant had described the lorry as being in ‘exceptional condition’ and also that it was ‘in first-class condition’. These descriptions were found to be innocent misrepresentations. Two days after the contract of sale had been concluded, the lorry needed a replacement part. The defendant agreed to pay half of the costs of the part. The following day, the lorry broke down again, following which the claimant sought to rescind the contract of sale.

The Court of Appeal held that the claimant had lost his right to rescind the contract. His right to rescind was impliedly lost when the claimant, knowing the condition of the lorry after it had been repaired the first time, then used it again afterwards. Pearce LJ held that that second occasion amounted to a ‘final acceptance’46 of the lorry ‘for better or for worse’.

Laches

This is equity’s doctrine of delay. Where a party seeks an equitable remedy he must bring his action without undue delay. If he delays unduly in bringing his claim, he will not be entitled to an equitable remedy. This doctrine is discussed further in Chapter 12.47

Where restitutio in integrum is impossible

For rescission to be awarded to a claimant, it must be possible to restore both parties to their pre-contractual positions. That is known as restitutio in integrum. If it is not possible to restore both parties to substantially their pre-contractual positions, the claimant will not be able to rescind his contract.

Suppose Scott buys a truffle, after being told by Terry that the truffle is a fine Italian one. On eating it, Scott discovers that it is not an Italian truffle at all, but has in fact been dug up in Derbyshire.

Terry’s misrepresentation would make the contract with Scott voidable. Scott would normally be entitled to rescind the contract. But here, as Scott has eaten the truffle, it is impossible to place both parties into their pre-contractual positions. As such, rescission cannot be awarded and Scott will have to be content to claim damages at common law (or under the Misrepresentation Act 1967) for Terry’s misrepresentation.

Where a bona fide purchaser of a legal estate for value without notice acquires an interest in the property

If an honest purchaser for value acquires a legal estate in the property which is the subject matter of the contract and does so before the claimant exercises his chance to rescind the contract, the claimant cannot claim to rescind the contract any longer. His claim is defeated by that of the bona fide purchaser, who is also known by the somewhat romantic name of ‘equity’s darling’.

Rectification

Rectification is an equitable remedy which allows mistakes in documents to be corrected by the court. The typical case is that involving a mutual misunderstanding — where the parties are at cross-purposes with each other in forming the written contract.

The nature of an order for rectification was originally set out by James V-C in Mackenzie v Coulson48 where he said:

Courts of Equity do not rectify contracts; they may and do rectify instruments purporting to have been made in pursuance of the terms of contracts. But it is always necessary for a plaintiff to show that there was an actual concluded contract antecedent to the instrument which is sought to be rectified; and that such contract is inaccurately represented in the instrument.49

The claimant had, therefore, to show that the written document did not accurately reflect the actual contract made between the parties before the written document was entered into.

This requirement of showing that there had to be a prior contract agreed between the parties was considered by the Court of Appeal in Joscelyne v Nissen.50 There a father agreed to transfer his business to his daughter, in return for which she would pay him a pension and certain household expenses, such as his gas and electricity bills. The actual written contract failed to mention the household bills specifically and the daughter stopped paying them when the parties argued with each other. The father sought rectification of the written agreement. The daughter argued that rectification was not possible as there had been no ‘concluded contract antecedent’ before the written agreement entered into between them.

Russell LJ held that there was a ‘strong burden of proof’51 on the party seeking rectification of the contract, but that it was not a prerequisite to rectification that an actual concluded contract needed to be proven before the written contract could be rectified. It would be sufficient that one party was able to show some form of ‘outward expression of accord’52 without going so far as to prove that a definitive contract existed before the written agreement was entered into.

This ‘strong burden of proof’ was qualified by Brightman LJ in Thomas Bates Ltd v Wyndham’s (Lingerie) Ltd.53 He held that the standard of proof that the claimant had to show was the normal civil one of the balance of probabilities. But he pointed out that, in reality, what the claimant was trying to do was to prove that a written contract was mistakenly drafted. As such, a high evidential requirement of ‘convincing proof’54 from the claimant was set by the courts to counteract the contradictory written contract.

The courts have also considered rectification in the event of a unilateral (one-sided) mistake. Rectification will be rarely ordered. As Slade LJ explained in Agip SpA v Navigazione Ata Italia SpA (The Nai Genova):55

in the absence of estoppel, fraud, undue influence or a fiduciary relationship between the parties, the authorities do not in any circumstances permit the rectification of a contract on the grounds of unilateral mistake, unless the defendant had actual knowledge of the existence of the relevant mistaken belief at the time when the mistaken plaintiff signed the contract.56

This is because the consequences of an order of rectification are very serious for the nonmistaken party. The order would amend the contract, probably to their disadvantage, when they had no awareness that there was ever anything amiss with the written contract.

To obtain an order for rectification for unilateral mistake, the claimant must show that the defendant knew of the mistake when entering into the written agreement. In Commission for the New Towns v Cooper (Great Britain Ltd),57 Stuart-Smith LJ reiterated that actual knowledge of the mistake was required. But this could also include the defendant shutting its eyes to the obvious or wilfully or recklessly omitting to do what an honest and reasonable person would have done. Only then would an order rectifying the agreement be made.

In GeorgeWimpey UK Ltd v V I Construction Ltd,58 George Wimpey UK Ltd entered into an agreement with V I Construction Ltd to buy a plot of land for £2,650,000. The claimant was to develop the land and build 231 flats on it. Added to the purchase price was to be a further sum if the claimant sold flats with ‘enhancements’: for example, the higher up in the block the flats were built, the higher the price they commanded. In turn, that would mean thatV I Construction Ltd would receive a further overall payment from George Wimpey UK Ltd after the flats had all been sold. Unfortunately, the written contract between the parties failed to take into account the enhancements, to George Wimpey’s disadvantage. The company therefore sought rectification of the contract, on the basis of its unilateral mistake about which, it argued, the defendant must have known. George Wimpey said that the defendant had acted unconscionably in not pointing out the mistake to them.

The Court of Appeal refused to order rectification. George Wimpey had failed to show convincingly that the defendants had either shut their eyes to an obvious error in failing to include the enhancements in the contract price or had wilfully and recklessly failed to make such enquiries as an honest and reasonable man would make. Far more convincing proof was needed for rectification to be ordered than the defendant simply acting unconscionably.

Summary of equitable remedies

A discussion of the range of equitable remedies shows that each of them is only awarded in exceptional circumstances, when an award of damages at common law would not adequately compensate the claimant. Each equitable remedy has its own hurdles over which a successful claimant must jump to secure success.

Proprietary Estoppel

Proprietary estoppel is an equitable cause of action that enables a claimant to claim an interest in property. It was described by Lord Scott in Cobbe v Yeoman’s Row Management Ltd59 as:

[a]n ‘estoppel’ bars the object of it from asserting some fact or facts, or, sometimes, something that is a mixture of fact and law, that stands in the way of some right claimed by the person entitled to the benefit of the estoppel. The estoppel becomes a ‘proprietary’ estoppel — a sub-species of promissory estoppel — if the right claimed is a proprietary right, usually a right to or over land but, in principle, equally available in relation to chattels or choses in action.

Making connections

You may recall promissory estoppel from your studies of contract law. That doctrine was devel-oped by Denning J in his landmark decision in Central London Property Trust Ltd v High Trees House Ltd.60 It enables a defendant to keep a claimant to his promise not to collect a full debt due to him from the defendant, in certain circumstances.

As such, promissory estoppel is reactive in nature. Birkett LJ described it as a ‘shield and not a sword’ in Combe v Combe.61 Proprietary estoppel, on the other hand, is proactive in nature. It enables a claimant to claim an interest in property which, as Lord Scott states, is normally land.

As Lord Walker pointed out in Thorner v Major,62 promissory estoppel is based on the existing legal relationship between the parties. Proprietary estoppel, on the other hand, need not be based on a legal relationship at all: it is instead based on property owned by the defendant.

The relationship between the two types of estoppel: Promissory and proprietary

Promissory estoppel is sometimes called ‘estoppel by representation’ whereas proprietary estoppel is sometimes known as ‘estoppel by acquiescence’. The notion underpinning proprietary estoppel is that the defendant has stood idly by whilst the claimant has undertaken some action which is inconsistent with his strict legal rights in relation to property. The defendant has acquiesced in the claimant undertaking such action but then refuses to recognise the claimant’s claim for an interest in the property. The defendant can be estopped (through his acquiescence) from denying the claimant a claim to the property. When the claim of proprietary estoppel was originally recognised by the courts in the nineteenth century,63 it was as a response to the defendant defrauding the claimant of the right or interest in the property he had acquired by his actions. The basis of the claim is that the defendant cannot now defeat the claimant’s interest in property which he had previously encouraged the claimant to acquire.

Several judges believe that proprietary estoppel is a species of promissory estoppel. Lord Scott certainly thought so in Cobbe vYeoman’s Row Management Ltd as did Oliver J in Taylors Fashions Ltd v Liverpool Victoria Trustees Co Ltd.64 This view is based on the notion that all estoppels are based on a promise not to enforce strict legal rights. Other members of the judiciary believe that estoppel itself may be divided into two parts: promissory and proprietary. This was probably the view of Lord Walker in Thorner v Major65 and was certainly the analysis led by Lord Denning MR in Crabb v Arun District Council.66 The latter believed that estoppel as a concept was based on broad principles of equity mitigating the effects of the common law. Promissory estoppel did not give rise to a cause of action but proprietary estoppel does.

The requirements to establish proprietary estoppel

These were confirmed by Lord Walker in Thorner v Major67 as being three-fold:

a representation or assurance made to the claimant; reliance on it by the claimant; and detriment to the claimant in consequence of his (reasonable) reliance.

However, Robert Walker LJ (as he then was) in the earlier Court of Appeal decision in Gillett v Holt68 had recognised that it was often not possible to break these requirements down into ‘watertight compartments’.69 He said that ‘the quality of the relevant assurances may influence the issue of reliance, that reliance and detriment are often intertwined’ and that ‘[i]n the end the court must look at the matter in the round’.70

As You Read

Be aware that the inherent difficulty with any type of estoppel is that it is an example of an equitable principle varying strict legal rights (which have often been written down) between the parties. In the case of proprietary estoppel, that variation is particularly powerful as it means that a claimant can acquire an interest in property. As will be shown, such a dramatic consequence has not dissuaded the courts from recognising a claimant’s claim in proprietary estoppel and the higher courts have dealt with a number of cases since the turn of the millennium.

Each of three elements to establish a claim in proprietary estoppel must be considered.

A representation

Given Lord Walker’s requirements for a claim in proprietary estoppel to arise, one might consider that a specific, defined representation was needed as the first ingredient for a successful claim. Naturally, a specific representation will always assist a claimant, but case law shows that it is normally difficult to pin-point when a precise representation was made to the claimant. The cases here may be broken down into two broad groups: where words are used to encourage the claimant to believe he will acquire a proprietary interest and where no such words are used.

The defendant’s assurance must concern specific property owned by him.71 Yet the doctrine of proprietary estoppel will not be restricted to cases where the defendant has defined precisely the extent of the property to which his assurance relates, as Lord Neuberger explained in Thorner v Major:

it would represent a regrettable and substantial emasculation of … proprietary estoppel if it were artificially fettered so as to require the precise extent of the prop-erty the subject of the alleged estoppel to be strictly defined in every case.72

Indeed, it was held by the High Court in Re Basham73 that a proprietary estoppel could arise for an individual’s entire residuary estate. However, the decision in this case was described in MacDonald v Frost74 as having to be treated with the ‘utmost caution’75 and in the latter case, the High Court thought that it was inconsistent with the views expressed by the House of Lords in Thorner v Major that the property generally had to be precisely defined.

Words …

If a claim in proprietary estoppel is to be based on words, those words cannot be too general to the extent that it is impossible to say that the defendant ever made the claimant any promise with regard to specific property. This is illustrated by Lissimore v Downing.76

Here, Kenneth Downing (a successful rock star with Judas Priest) commenced a relationship with Sarah Lissimore. During the course of that relationship, he drove her to the edge of his country estate in Shropshire and said ‘I bet you never thought all of this would be yours in a million years’. At times during their relationship, he also used phrases such as she ‘did not need to worry her pretty little head about money’ and repeatedly referred to her as the ‘Lady of the Manor’. When the parties split up, she brought a claim in proprietary estoppel against him, claiming a share of the property.

The High Court held that she had not established any entitlement to a claim. The words used by the rock star were simply too general to found a claim in proprietary estoppel. It was impossible to say from those words that he ever intended that she should have a share in any specific property. The words referred to both parties enjoying the property together, not sharing the equitable interest of it.

This case may be contrasted with the decision of the Court of Appeal in Gillett v Holt.77

Mr Holt met Mr Gillett in 1952 when Mr Gillett was only 12 years old. Mr Holt was a farmer. The two men got on very well, to the extent that their close friendship lasted some 40 years. Mr Gillett gradually took on more day-to-day responsibility at Mr Holt’s farm, to the point where Mr Holt retired from farming and was content to leave running the business to Mr Gillett. On seven occasions, Mr Holt explained to Mr Gillett that he would be entitled to the farming business, together with the farmhouse, when Mr Holt died.

In 1992, Mr Holt met a Mr Wood, whom he liked. Mr Holt liked Mr Wood. His friendship with Mr Gillett began to deteriorate and, three years later, Mr Gillett was sacked by Mr Holt from the farming business. Mr Holt also made a will, making Mr Wood the main beneficiary and leaving nothing at all to Mr Gillett. Mr Gillett brought a claim in proprietary estoppel against Mr Holt.

At first instance, Carnworth J held that he could not find an irrevocable promise by Mr Holt to Mr Gilllett that the latter would inherit the farming business. Carnworth J thought that such an irrevocable promise was essential for Mr Gillett to establish a claim. Mr Gillett was successful in his appeal to the Court of Appeal.

In giving the main judgment of the court, Robert Walker LJ held that it did not have to find an irrevocable promise on the part of the defendant as an initial step. The court merely had to find a promise made by the defendant. The claimant’s detrimental reliance on that promise then turned the promise into being irrevocable.

There were numerous examples of the types of promise required for Mr Gillett to establish a successful claim here. The assurances made by Mr Holt were repeated a number of times, usually before many witnesses. The assurances were also unambiguous. Moreover, as Robert Walker LJ put it, the assurances ‘were intended to be relied on, and were in fact relied on’.78

Representations over a number of years were also the subject of Jennings v Rice.79 Here the representations were perhaps not as explicit as in Gillett v Holt.

Mrs Royle lived in Shapwick, Somerset. She died a childless widow. After the death of her husband, she met Mr Jennings and initially employed him to tend her garden. Over a period of nearly 30 years, his duties increased as Mrs Royle became more incapacitated. He started to run errands for her and eventually, after a burglary at her home, she persuaded him to sleep overnight at the property to act as a quasisecurity guard for her. Mr Jennings did this latter task for nearly three years, until Mrs Royle’s death in 1997.

For the vast majority of their relationship, Mrs Royle paid Mr Jennings no wage at all. Instead she said words to the effect that ‘he would be all right’ and that ‘this will all be yours one day’.

At first instance, the trial judge found that Mr Jennings had established a claim in proprietary estoppel and that he should be awarded £200,000 to satisfy the equity (the claim) that had arisen in his favour. The trial judge held that such assurances by Mrs Royle were sufficient to satisfy the first requirement of raising a proprietary estoppel. This finding was undisturbed by the Court of Appeal.

Making connections

It is, at first glance, odd that virtually the same words were used in both Lissimore v Downing and Jennings v Rice but with entirely different results: no claim was established in the former case, but was in the latter. This, it is suggested, exemplifies the principle that the court considers a claim of proprietary estoppel ‘in the round’.80 It is true that the words used by the defendant are important, but they cannot be judged solely on their own. They must be viewed in the context of the facts of the case to ascertain whether the defendant did create an expectation in the claimant’s mind that he would be entitled to a share in the defendant’s property. The claimant’s expectation can be evidenced by whether he subsequently relied on the defendant’s words to his detriment. As will be shown, no reliance occurred in Lissimore v Downing whilst there was substantial reliance in Jennings v Rice.

This is all part of the same notion that equity always considers words in the context in which they are used. This has been demonstrated, for instance, in terms of certainty of intention in forming an express trust (see Chapter 5).

The recent decision of the House of Lords in Thorner v Major81 illustrates that the court will take into account the peculiarities of the parties to determine if an assurance has been made. This was a case in which words were spoken, but to say that they were unclear is an understatement. The House of Lords held that a combination of words and the defendant’s conduct could constitute the requisite assurances on which the claimant could rely.

The facts concerned two members of the Thorner family, Peter and David. Peter was a farmer of land in Cheddar, Somerset. In 1976, David began to help him with the farming business. He did so for 29 years, without being paid. As the years passed, David’s responsibilities increased. Peter was described by the trial judge as being ‘a man of few words’82 and, in addition, had a habit of not talking about the subject matter directly in a conversation.

A key event occurred in 1990 when Peter gave David the bonus notice on two life assurance policies and said to him ‘That’s for my death duties’. The trial judge found that, in so doing, Peter had indicated to David that he would be his successor to the farm. David understood the remark to mean that he would inherit the farm on Peter’s death. As a consequence of this comment, David did not pursue other farming opportunities which may have benefited him more, but continued to work for Peter. Peter later died intestate and David brought a claim in proprietary estoppel for the farm, together with various assets of the farming business.

The trial judge held that David’s claim in proprietary estoppel should succeed, but the Court of Appeal reversed this decision. Lloyd LJ held that an assurance had to be ‘clear and equivocal’83 in order to establish a claim in proprietary estoppel. David appealed to the House of Lords.

The House of Lords agreed that David’s appeal must succeed. Lord Walker said that the necessary assurance did not have to be clear and unequivocal, but that it had to be ‘clear enough’.84 He quoted (with approval) Hoffman LJ’s exposition of such a test in Walton v Walton85 that:

The promise must be unambiguous and must appear to have been intended to be taken seriously. Taken in its context, it must have been a promise which one might reasonably expect to be relied upon by the person to whom it was made.

Peter’s assurances were intended to be taken seriously by David and were to be relied upon by him. As such they were clear enough. Lord Rodger emphasised86 that the test was not whether the words were clear enough to an outsider, but to the person to whom they were addressed. It was David who had to form a reasonable view that the words used by Peter amounted to an assurance that he would receive the farm on Peter’s death.

It is the point that the court will take into account the parties‘ backgrounds when considering the nature of the assurance that may explain the otherwise contradictory decision of the House of Lords in Cobbe v Yeoman’s Row Management Ltd,87 a case decided just eight months before Thorner v Major but in which a different conclusion was reached as to whether there was an assurance and, seemingly, on the requirements for a valid assurance in proprietary estoppel.

Mr Cobbe negotiated with Yeoman’s Row Management Ltd to apply for (and obtain) plan-ning permission to convert a block of flats into townhouses. Provided planning permission was obtained, Yeoman’s Row was to sell the land to Mr Cobbe for £12 million. Mr Cobbe was then to develop the townhouses, whereupon any proceeds of the sales over an agreed amount were to be split equally between the parties. This agreement was not recorded in writing. Mr Cobbe obtained planning permission, having spent time and money in so doing. At that point, Yeoman’s Row wanted to renegotiate the agreement. It wanted £20 million as payment upfront, together with a higher share of the proceeds from the sale of the townhouses. Mr Cobbe brought a claim in proprietary estoppel, claiming the company was estopped from denying its agreement with him.

Etherton J and the Court of Appeal held that Mr Cobbe’s claim in proprietary estoppel was made out. The House of Lords allowed the defendant’s appeal.

Lord Scott held that any right Mr Cobbe had could ‘be described as neither based on an estoppel nor as proprietary in character’.88 The fatal problem for Mr Cobbe was that no final agreement was ever reached between the parties. The parties knew that the oral deal that they had reached was always subject to a final, written contract being concluded. There was nothing that the defendant was estopped from denying. In addition, he had no proprietary interest to protect as he was not able to make out that the defendant owned the property on trust for him.

Lord Scott expressly rejected the views of the Court of Appeal and Etherton J that a remedy in proprietary estoppel could be granted simply on the unconscionable conduct of the defendant. He said:

To treat a ‘proprietary estoppel equity’ as requiring neither a proprietary claim by the claimant nor an estoppel against the defendant but simply unconscionable behaviour is, in my respectful opinion, a recipe for confusion.89

Lord Walker made the same point in starker terms:

[proprietary estoppel] is not a sort of joker or wild card to be used whenever the court disapproves of the conduct of a litigant …‘90

Mr Cobbe had to show that he had received an assurance from the defendant to be entitled to a certain interest in land. He could not. All he could show was that, if and when he obtained planning permission, the parties would then negotiate a formal contract for the development of the land. Until that point, he had no interest in the land at all. Whilst Lord Scott agreed91 with the Court of Appeal and Etherton J that such conduct by the defendant was unconscionable, that was not enough to found a claim in proprietary estoppel.

At first glance, it is perhaps difficult to reconcile the decision in Cobbe with that in Thorner v Major. In the former, the House of Lords appears to be insisting quite strictly on fairly rigid requirements to establish a claim in proprietary estoppel; it seems in the latter that a fairly loose statement from one party to the other sufficed. Yet it is suggested that the cases can be reconciled, on the basis that the court considers the issue ‘in the round’, taking into account the parties‘ attributes. In Cobbe, the House of Lords appreciated that both claimant and defendant were experienced commercial negotiators who would have been well aware that their initial oral deal was not a binding agreement justifying the intervention of the equity in terms of proprietary estoppel. In Thorner v Major, it was important that the defendant would have known that the claimant would have understood his fairly oblique assurances. An assurance is always required as a key ingredient to establish a proprietary estoppel, but the court will consider that assurance in the light of the parties‘ backgrounds and personal attributes. Certainly this was how Lord Neuberger understood the matter in Thorner v Major:

it is sufficient for the person invoking the estoppel to establish that he reasonably understood the statement or action to be an assurance on which he could rely.92

No words …

On occasions, no words — or no clear words — pass between defendant and claimant on which the claimant can found a claim. But he must still identify an assurance that the defendant has given him, relating to the defendant’s property.

An example of an assurance arising from conduct occurred in Crabb v Arun District Council.93

The facts involved a disputed right of access to a piece of land near Bognor Regis. A piece of land was divided into two smaller pieces and a right of access reserved onto a new road from the northern piece. The southern piece would have been effectively landlocked without a similar right of access to the new road. The new road was on land owned by the defendant. At a site meeting, the claimant and defendant reached an agreement in principle that the claimant could have access to the new road directly from the southern piece of land. The trial judge found as a fact that there was no definitive assurance spoken by the defendant to that effect but, nonetheless, the parties proceeded as though a right of access had been granted. The defendant constructed a fence along the boundary between their road and the southern piece of land but left a gap for the right of access for the claimant and initially installed a pair of gates across that right of access. Unfortunately, the parties had a disagreement, resulting in the defendant dismantling the gates and erecting a fence across the right of access. This left the southern piece of land with no access to it.

The claimant brought an action in proprietary estoppel. There was no specific verbal or written assurance he could point to so instead his action was based on the defendant’s conduct of leaving a gap and constructing the gates as recognition of a right of access in the claimant’s favour.

In the Court of Appeal, Lord Denning MR explained that proprietary estoppel did not require the claimant to go so far as to show that he had entered into a contract with the defendant. The claimant had simply to rely on the defendant’s words or conduct. Here the defendant’s conduct could raise an estoppel in the claimant’s favour. The construction of the gates led the claimant to believe that he was entitled to enjoy a right of access to the new road.

Reliance

It is not enough for the claimant to show that the defendant made an assurance to him that he would have an interest in specific property. In addition, the claimant must rely on that representation, to his detriment. It is the detrimental reliance that turns an initially revocable promise into an irrevocable assurance. The reliance must be reasonable but in Thorner v Major, Lord Neuberger thought that it would be ‘rare’J94 for the court to decide that no estoppel arose because the defendant could not reasonably have expected the claimant to rely on his assurance.

Reliance was considered by Robert Walker LJ in Gillett v Holt. He said that this meant that there had to be a ‘sufficient link’95 between the assurance given by the defendant and the detriment suffered by the claimant. The link was straightforward. It could be said to be akin to offer and acceptance in contract where the defendant had used words to encourage the claimant to believe he would have an interest in his property. If no words were used, the link could be provided by the defendant otherwise encouraging the claimant to spend money on the property.

Detriment

The claimant must act to his detriment in relying on the assurance. This suggests that the claimant must go beyond what would normally be expected in the relationship between the parties.96

Robert Walker LJ defined detriment as follows in Gillett v Holt:

it is not a narrow or technical concept. The detriment need not consist of the expenditure of money or other quantifiable financial detriment, so long as it is something substantial. The requirement must be approached as part of a broad inquiry as to whether repudia-tion of an assurance is or is not unconscionable in all the circumstances.97

The detriment must be causally connected to the assurance. The time for judging whether detrimental reliance has occurred is at the point where the defendant tries to go back on his assurance. Robert Walker LJ explained that whether or not the detriment is substantial enough ‘is to be tested by whether it would be unjust or inequitable to allow the assurance to be disregarded’.98

Clear cases of detrimental reliance have emerged from some cases. In Inwards v Baker,99 the Court of Appeal held that it occurred when a son built a new bungalow on land owned by his father, after being encouraged to do so by a verbal assurance by his father that he could construct a property on it.

A similar decision was reached in Pascoe v Turner.100 Here, Samuel Pascoe began an affair with another woman but told his current partner, Ms Turner, that a house in Tuckingmill, Cornwall, together with its contents, was hers. The Court of Appeal held that her actions of continuing to live in the house, spending money on redecorating and making substantial improvements to it, were evidence of detrimental reliance on her part.

These cases were evidence of short-term detrimental reliance and the spending of money as a result of assurances being made. Longer-term detrimental reliance can also be illustrated in Gillett v Holt.101 The facts of this case also show that the spending of considerable time can also be seen to be detrimental reliance.

In Gillett v Holt, Robert Walker LJ held that detrimental reliance could, of course, only come after the assurance made to the claimant. Anything done beforehand could only be by way of (useful) background. But detriment could clearly be found by looking at the cumulative effect of the claimant’s actions. Mr Gillett spent considerable sums on the farmhouse, believing that he would acquire it on Mr Holt’s death. He effectively provided Mr Holt with a family for 30 years, after he married and had children of his own, all of whom continued to have a close relationship with Mr Holt. Both Mr and Mrs Gillett worked for Mr Holt for this long period of time, spurning opportunities to earn a better living elsewhere and failing to plan for their futures, precisely because they believed they would be entitled to a proprietary interest in Mr Holt’s property. There was more than adequate evidence of detrimental reliance over a long period of time.

The short-term spending of time appears generally not to amount to detrimental reliance, probably because it is not seen to be sufficiently substantial. For example, Mrs Rosset’s alternative claim in Lloyds Bank plc v Rosset102 was that she was entitled to a share of the house based on proprietary estoppel. Her evidence of detrimental reliance — supervising builders undertaking renovation works — was rejected by the House of Lords. It simply was not substantial enough.

Neither was detrimental reliance found on the facts in Lissimore v Downing. Miss Lissimore argued that she gave up her employment only because she had been promised an interest in Mr Downing’s property. Yet this was not done on the strength of an assurance from Mr Downing that he would provide for her forever, but because she disliked her job. She also argued that she had undertaken gardening works as well as helping to manage the estate and the accounts. None of this was evidence of detrimental reliance on an assurance to share the property beneficially. It simply evidenced the parties sharing a relationship. Viewed against the other evidence of Mr Downing’s reluctance to part with a share in his £2 million estate, it could not be argued in the round that any claim in proprietary estoppel had been made out.

Remedies

If a successful claim is made out in proprietary estoppel, the court’s task is, according to Scarman LJ in Crabb v Arun District Council,103 to do ‘the minimum equity to do justice’ to the claimant. In the same case, Lord Denning MR described that equity was at its ‘most flexible’104 in terms of awarding a remedy. In the case itself, for instance, the claimant was awarded an easement to access the new road.

In Sledmore v Delby,105 Hobhouse LJ stated that the remedy awarded must also be propor-tionate to the assurance made by the defendant and the detrimental reliance expended by the claimant. Proportionality of the result was described as the ‘most essential requirement’106 of the court’s task to achieve justice between the parties. It is a question of doing justice for both parties, not just the claimant.

Robert Walker LJ analysed the appropriate remedy available to the claimant in Jennings v Rice. He thought that the cases could be broken down into two areas: