Chapter 13

Tracing and Actions Against Strangers to the Trust

Chapter Contents

Actions Against Strangers to the Trust

This chapter considers two subjects, both connected to remedies: (i) the process of tracing and (ii) personal remedies against strangers to the trust. Tracing is the ability to follow property into another’s hands. Personal remedies against a stranger to the trust continues the study of personal actions against individuals who have assisted in the commission of a breach of trust by the trustee. This latter subject builds upon personal actions against the trustee himself discussed in Chapter 12.

As You Read

Look out for the following issues:

![]() what tracing is, what it involves and why it might be more advantageous for a beneficiary to pursue on some occasions as an alternative to a personal action against the trustee;

what tracing is, what it involves and why it might be more advantageous for a beneficiary to pursue on some occasions as an alternative to a personal action against the trustee;

![]() how tracing leads to different remedies at common law and in equity. At common law, tracing may give rise to an action for money had and received; in equity, it renders the recipient of the property liable to account for it as a constructive trustee; and

how tracing leads to different remedies at common law and in equity. At common law, tracing may give rise to an action for money had and received; in equity, it renders the recipient of the property liable to account for it as a constructive trustee; and

![]() how equity might enable a claim to be taken against anyone helping a trustee in committing a breach of trust, or for receiving trust property.

how equity might enable a claim to be taken against anyone helping a trustee in committing a breach of trust, or for receiving trust property.

Tracing

Chapter 12 considered how a beneficiary might pursue a trustee personally for a breach of trust. On occasion, even if a trustee would otherwise be found liable for a breach of trust, it may not be worthwhile for the beneficiary to bring an action against him. If, for instance, the trustee has been made bankrupt, the beneficiary is in no stronger a position than the rest of the trustee’s creditors who are owed by him. The beneficiary will simply have to wait his turn in the queue of general creditors. Alternatively, if the trustee has breached the terms of the trust and has then disappeared, any action against him personally will be all but impossible to commence.

Fortunately, another process is available. It is a proprietary action. This means that it is a right in rem in that it attaches itself to the property itself that has been misused. It is known as ‘tracing’.

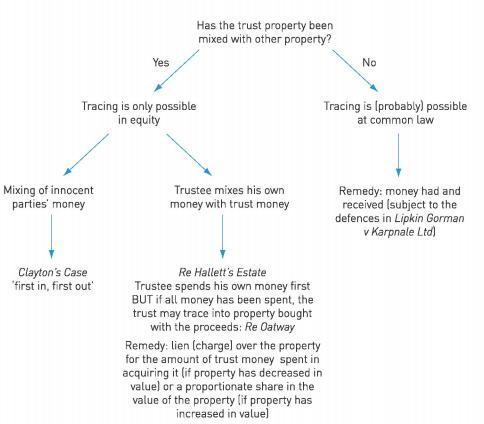

Tracing may occur at common law or in equity. Common law tracing involves the trustee pursuing the legal title to property which has found its way into the wrong hands. Equitable tracing offers someone who has benefited from a fiduciary relationship (for example, a beneficiary) the ability to follow the equitable interest in property which has been misappropriated.1

As tracing is a proprietary claim, the claim is not against the recipient of the property personally but instead against the actual property. So, for example, this means that in the event of the trustee’s bankruptcy, the beneficiary is able to circumvent the trustee’s other creditors by claiming that the trust property itself should be returned to the trust and should not be available as part of the trustee’s personal assets to be distributed to his general creditors.

‘Tracing’ was defined by Millett LJ in Boscawen v Bajwa.2 To Millett LJ, tracing was neither a remedy nor a claim in its own right. It was, instead, a process. This process could be pursued not just against a wrongdoer but anyone who had knowingly assisted in a breach of trust or who had received the property, knowing that it was really trust property. ‘Tracing’, said Millett LJ, was:

the process by which the plaintiff traces what has happened to his property, identifies the persons who have handled or received it, and justifies his claim that the money which they handled or received (and, if necessary, which they still retain) can properly be regarded as representing his property.3

What can be shown from this definition is that tracing is where the claimant follows his property and brings a claim to have it — or its value — returned to the trust. It does not matter how many people have handled the property provided that, generally, the trust property remains identifiable. The claim to the property is ‘based on the retention by him of a[n] … interest in the property which the defendant handled or received.’4

A successful tracing claim does not depend on proving that the defendant has been enriched by the claimant’s property. Tracing is not dependent on principles of the law on unjust enrichment5 being met. It can be illustrated diagrammatically in the following example.

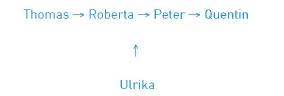

Thomas is a trustee administering a trust on behalf of Ulrika, the beneficiary. Thomas commits a breach of trust by selling trust property to Roberta and then disappears with the proceeds of sale. Roberta sells the trust property to Peter who, in turn, sells it to Quentin. Each of the purchasers is aware that the property is trust property.

Ulrika may, in theory, bring an action against Thomas personally for breach of the trust. But such an action would be difficult as he has disappeared. Instead, Ulrika’s better claim would be against Quentin. She would seek to trace the trust property into Quentin’s hands.

Tracing may be undertaken against the wrongdoer or anyone who has knowingly acquired an interest in the trust property or knowingly assisted in the breach of trust. In Boscawen v Bajwa, Millett LJ identified three defences that a defendant subjected to a tracing process may put forward:

![]() the tracing exercise is not valid because, in reality, the claimant has no claim against the property;

the tracing exercise is not valid because, in reality, the claimant has no claim against the property;

![]() the defendant is a bona fide purchaser of the property without notice of the trust and there-fore takes the property free from the trust; and/or

the defendant is a bona fide purchaser of the property without notice of the trust and there-fore takes the property free from the trust; and/or

![]() the defendant has innocently changed his position since he acquired the trust property.6

the defendant has innocently changed his position since he acquired the trust property.6

If none of these defences succeed, the claimant is entitled to a remedy. What the remedy is depends on whether the claimant traces at common law or in equity.

At common law, the remedy that tracing leads to is restitutionary. It is for money had and received. The money that the defendant has received must be returned by him to the claimant. Nowadays, this remedy that the claimant enjoys is subject to the defendant successfully arguing that he has innocently changed his position as a result of the money being given to him, or that he acted in good faith and provided full consideration for the money.7

If tracing is pursued in equity, the main remedy that the claimant enjoys is a personal one against the recipient of the property. That would entail the recipient paying equitable compensation to the beneficiary or restoring the trust fund to the value it was worth before the breach of trust occurred.

The claimant may wish to have the trust property returned to him. Thus he may pursue a proprietary remedy against the property itself, or what it has subsequently turned into if the recipient of it has used it in some way. To do so, he must prove that the property is still in the defendant’s hands. If this can be shown, the court may order that the defendant holds the property on constructive trust for the claimant and further compel the defendant to transfer it to him. If the defendant has, however, used the trust property in some way, other proprietary remedies may be open to the claimant to pursue. In Boscawen v Bajwa, Millett LJ gave the example of where trust property had been used to improve a building. The beneficiary may ask the court for a charge over the building to the amount by which the building has increased in value.

Key Learning Point

Tracing is merely the road along which a claimant must travel to seek his remedy. It is not the remedy in itself. The remedy awarded depends if the claimant traces at common law or in equity.

At common law, tracing leads to a claim for money had and received by the defendant. The defendant must return the money he has received — or what remains of it.

In equity, the remedy is normally equitable compensation or, alternatively, a declaration that the defendant holds the money on constructive trust for the claimant and must return it to him.

In both cases, the claimant may generally enjoy an ‘uplift’ if the money has been success-fully used by the defendant to generate further money.

Tracing v Following

Tracing is different from following. As Lord Millett said in Foskett v McKeown, ‘[f]ollowing is the process of following the same asset as it moves from hand to hand’.8 In contrast, ‘[t]racing is the process of identifying a new asset as the substitute for the old’.9

The recent decision in Sinclair Investments (UK) Ltd v Versailles Trade Finance Ltd (in administrative receiv-ership)10 gave the Court of Appeal the opportunity to comment generally on tracing and in particular on (i) when a proprietary interest arises and (ii) what would constitute sufficient notice to defeat a bona fide purchaser’s claim that he bought without notice in good faith.

The facts concerned a fraudulent investment scheme. Versailles Group plc owned the defendant trading company. The main shareholder of Versailles Group plc was Mr Carl Cushnie. Versailles Group plc sought investments from both individuals and banks. Their money would be given to another company, Trading Partners Ltd, again controlled by Mr Cushnie, who would buy goods and resell them. Any money not used to buy goods was to be placed in a bank account. The investors would receive a share of the profits on the goods bought and resold. The defendant company managed the workings of Trading Partners Ltd.

In fact, the money received by Trading Partners Ltd was passed to the defendant company but it was not used as agreed. Instead, it was used to pay the profits to the investors, stolen by Mr Cushnie (to buy a house in Kensington, London, for nearly £10 million) or sent to other companies controlled by Mr Cushnie. Effectively, Mr Cushnie was using the investors’ funds simply to circulate around between the other investors, himself and his other companies. The purpose of such circulation was to inflate (falsely) the value of the defendant’s turnover. Mr Cushnie eventually floated the company and it was listed on the London Stock Exchange. He sold some of his shares for nearly £29 million and distributed the proceeds to various parties including effectively himself and various banks who had advanced loans to him.

Eventually, in 2000, Versailles Group plc collapsed as the scale of the fraud (involving hundreds of millions of pounds) became clear. The traders were owed nearly £23 million. The banks were owed £70.5 million. The claimant in the action was one of the traders that were owed money.

The claimant brought two claims. The first is relevant here: that it was entitled to the proceeds of the shares that Mr Cushnie had sold and which proceeds had subsequently been distributed to, inter alia, various banks. The claimant’s case was that Mr Cushnie held the proceeds on constructive trust for it. This claim was based on Mr Cushnie, as a director, owing fiduciary duties to Trading Partners Ltd not to make a secret profit and not to misuse funds.11 Breach of these duties resulted in a £29 million gain for Mr Cushnie. The claimant said that it was entitled to trace its money through these shares to the eventual recipients (the banks).

Delivering the only substantive judgment of the Court of Appeal, Lord Neuberger MR held tracing required the party to show that he had owned an interest in property which could then be followed. A ‘consistent line’12 of previous Court of Appeal decisions had stated that a beneficiary of a fiduciary’s duties could not claim a proprietary interest in property unless the beneficiary had originally enjoyed an equitable interest in that property. If the beneficiary had owned no interest in the property, his remedy was limited to equitable compensation for breach of fiduciary duty.

Mr Cushnie had not acquired the shares in Versailles Group plc with any money that had originally been owned by Trading Partners Ltd. The claim for the profits of £29 million that Mr Cushnie gained was based on the transaction in which that profit was made. That gave rise to a duty to pay equitable compensation only. As Trading Partners Ltd had not provided the money to purchase the shares originally, there could be no tracing of any of their property to be done through to the eventual profit Mr Cushnie made.

In reaching this conclusion, Lord Neuberger MR disagreed with the Privy Council’s earlier decision in Attorney-General for Hong Kong v Reid.13 Mr Reid was a solicitor who worked as the Acting Director of Public Prosecutions in Hong Kong. He accepted substantial bribes for not prosecuting certain individuals. He purchased three properties in New Zealand with the bribes. The Crown brought an action claiming the value of those properties, which were worth HK ![]() 12.4 million. The properties had increased in value from when Mr Reid had originally purchased them.The Privy Council held that the claimant could trace the bribe into the properties.

12.4 million. The properties had increased in value from when Mr Reid had originally purchased them.The Privy Council held that the claimant could trace the bribe into the properties.

The Privy Council decided that a recipient of a bribe held the legal title in that bribe, but that equity would insist that the recipient of the bribe should hold the bribe on trust for the person to whom his fiduciary duties were owed. In this case, that was the Government of Hong Kong. It could not be the provider of the bribe as he had committed a criminal act in offering the bribe. If the bribe was used and increased in value, the beneficiary had to be entitled to that gain as well as the original bribe, to prevent the ‘guilty’ individual from benefiting from breach of his fiduciary duties.

Lord Neuberger MR doubted that the reasoning of the Privy Council was correct in that case. The decision was odd in that the Government of Hong Kong was held to be entitled to recover both the bribe and its gain even though it had never enjoyed an equitable interest in the money used in the bribe. It had never had any proprietary interest in the original money which had, as a bribe, been paid to the corrupt employee by a third party.

Lord Neuberger MR thought that where the beneficiary did not have any equitable interest in property, he could not pursue a proprietary claim. His claim was limited to that of equitable compensation for the breach of fiduciary duty that the fiduciary had committed by conducting the transaction. This conclusion reflected many earlier Court of Appeal cases.14

Making connections

In delivering his judgment, Lord Neuberger MR reminded the court of the doctrine of precedent. There had been a number of Court of Appeal decisions over the previous 95 years deciding that tracing could only occur if the tracing party could show that he had previously owned an interest in the property. Then a Privy Council decision in Attorney-General for Hong Kong v Reid had decided that such Court of Appeal cases were wrongly decided.

Lord Neuberger MR believed that the Court of Appeal must follow its own previous decisions in preference to one of the Privy Council. This had been decided earlier in Young v Bristol Aeroplane Company Ltd15 It was, if necessary, to be left to the Supreme Court to overrule a Court of Appeal decision if it felt it was wrong, not for the Court of Appeal effectively to do that itself by following a Privy Council decision in preference to its own.

Whilst Lord Neuberger MR was not stating anything radical, the effect of his words is perhaps radical, for it involved the rejection of a principle decided by Law Lords sitting as the Privy Council just 17 years previously.

Lord Neuberger MR hesitantly thought that the actual result in Attorney-General for Hong Kong v Reid might be justified on a policy ground, presumably that a corrupt employee in receipt of a bribe should not be allowed to keep the bribe or any profit generated by its use. But the reasoning underpinning the employer acquiring that profit was suspect. It did not depend on tracing. He thought that if the beneficiary, as the employer in Attorney-General for Hong Kong v Reid, was to benefit from the gain made by the fiduciary (the employee), that should be reflected by an increase in the award of equitable compensation, as opposed to holding that tracing could occur without the beneficiary enjoying a proprietary interest in the original trust property. This last point was entirely new as it seems to have been rejected in the earlier leading Court of Appeal decision in Lister v Stubbs.16

Bona fide purchaser for value without notice

In a purely obiter part of his judgment, Lord Neuberger MR addressed the type of notice required for a bona fide purchaser for value of assets to take free of an interest. The banks’ alternative argument was that, when they received the proceeds from the shares sold by Mr Cushnie in partial discharge of their loans, they received it as a bona fide purchaser for value without notice of the Trading Partners’ equitable claim to the money. Strictly this part of the judgment was unnecessary, as Lord Neuberger MR had already decided that there was no tracing claim. But if there was, he considered whether the banks would have had a good defence, based on whether they had notice of Trading Partners’ interest. This depended on what ‘notice’ constituted. It meant whether the banks knew, or should be taken to have known, of the relevant facts surrounding their repayments by Mr Cushnie. But it also revolved around whether the banks should have been taken to know the relevant legal consequences of accepting the money in partial discharge of their loans (i.e. if they knew that the money was paid to them under suspicious circumstances, should then they be taken to have known that the money was probably owned by another party and susceptible to a tracing claim).

Lord Neuberger MR did not believe it was right automatically to say that the banks either knew or should have known of the legal consequences of accepting the money from Mr Cushnie. He said the question was whether:

a reasonable person with their attributes (i.e. those of a responsible large bank with the benefit of highly experienced insolvency practitioners as their appointed administrative receivers) should either have appreciated that a proprietary claim probably existed or should have made inquiries or sought advice, which would have revealed the probable existence of such a claim.17

Lord Neuberger MR held that the trial judge had been right to conclude that the banks were bona fide purchasers for value and took the money without notice of Trading Partners‘ claim. In terms of the facts, it had subsequently been made clear that the transactions made by the group of companies were fraudulent, but that was not apparent at the time the banks accepted the money from Mr Cushnie. As those facts were not clear at the time, it could not be said that the banks should have appreciated the potential legal consequence that the money paid by Mr Cushnie might have been owned by Trading Partners Ltd.

Tracing may occur at common law or in equity.

Tracing at Common Law

Tracing at common law involves following the legal interest in the trust property into another’s hands and claiming that it, or the property it has subsequently become, should be returned to the trust. As it is the legal interest in trust property that is being traced, action will normally be taken by the trustee. Millett LJ has described there being ‘no merit in having distinct and different tracing rules at law and in equity’18 but be that as it may, it seems that different rules do exist. The ability to trace the legal interest of trust property at common law is curtailed more than the right to trace the beneficial interest of the trust property in equity.

The ability to trace at common law

The right to trace trust property at common law is said to arise from the decision in Taylor v Plumer.19 The decision in that case was given by the Court of King’s Bench (a common law court) and so it was, for many years, assumed that the common law therefore gave its own right to trace trust property. It has subsequently been accepted by Millett LJ20 in the Court of Appeal’s decision of Trustee of the Property of F C Jones & Sons (A Firm) v Jones, that the Court of King’s Bench was actually applying equitable principles. Millett LJ’s view was that equity was following the law, as per its maxim, but the law happened not to be declared until much later.

The facts concerned the instruction by the defendant to a Mr Walsh, a stockbroker, to purchase Exchequer bills on his behalf. The defendant gave him £22,200 to effect the purchase. Mr Walsh spent £6,500 on the purchase of Exchequer bills. But then he had a different plan, for his own personal gain. He was insolvent. He planned to use the remainder of the money in the purchase of American government bonds and gold bullion. He duly did so, but not before he had exchanged some of the defendant’s money for a banker’s draft which he then used to buy the gold bullion. He then proceeded to Falmouth, where he was due to board a ship to begin a new life in America.

The defendant heard about Mr Walsh’s plan and managed to send a police officer to intercept him. Mr Walsh surrendered the bullion and the American bonds.

The case came about because Mr Walsh had been made bankrupt. His trustee in bankruptcy brought an action at common law, seeking the court’s decision on whether he was entitled to some or all of the American bonds and bullion. His claim was that they were owned by Mr Walsh and, upon his bankruptcy, passed to the trustee in bankruptcy. The defendant argued that the bonds and bullion were rightfully his, as they had been bought with his money.

Lord Ellenborough CJ held that the defendant was entitled to retain the bonds and bullion as his own property. The property given to Mr Walsh had been subject to a trust in favour of the defendant and the trust still stood. It made no difference that the original money that the defendant had given Mr Walsh had changed its composition into American government bonds and bullion for as Lord Ellenborough said:

if the property in its original state and form was covered with a trust in favour of the principal, no change of that state and form can divest it of such trust.21

Tracing was available to trace the legal interest in the defendant’s money into the subsequent property — the bonds and bullion — that the trustee (Mr Walsh) had purchased with it.

Tracing depended, however, on there being a clear link between the original trust property and what that property had been turned into. Here there was a clear link: it was clear that the bonds and bullion were only purchased with the defendant’s money and so the money had been turned into those bonds and bullion.

Where, however, it was not possible to show such a link between the original trust property and what that property had turned into, tracing would not be available. Such an occasion would be where the trust property was turned into money and the money was then mixed with other money. Lord Ellenborough CJ said this gave rise to a ‘difficulty of fact and not of law’22 in that it was then simply not possible to say which of the mixed money was the original trust property. All that would remain would be ‘an undivided and undistinguishable mass of current money’23Tracing original trust property which had been mixed with other money would need to wait for the development of the later equitable rules on tracing.

Key Learning Point

The common law will, therefore, permit tracing to occur provided that the trust property remains clearly identifiable. It is not the case that the common law will not permit money to be traced, merely that the money must have been kept separate from any other money.

Money was kept separate in Banque Belge pour L’Etranger v Hambrouck.24

The facts concerned a company called A M Pelabon which had its bank account with the claimant bank. The company’s chief assistant accountant, Mr Hambrouck, fraudulently forged a number of the company’s cheques and made them payable to himself. He paid the cheques in and, over a period of two years, appropriated £6,680 from the company to himself in this manner. He then wrote cheques to his mistress, Mademoiselle Spanoghe. She paid the cheques into her personal bank account. By the time the fraud was discovered, £315 remained in her account. The claimant bank brought an action for the recovery of that sum. They wished to trace the legal title of the money and reclaim it. The trial judge found the claimant could trace the money. Mlle Spanoghe appealed, claiming that because the money had passed through two bank accounts before it reached her, it was not possible to identify the money which she received as the claimant’s original money.

Two Lords Justices in the Court of Appeal rejected the proposition that tracing could not occur at common law. Atkin LJ pointed out that the only restriction on tracing money identified in Taylor v Plumer was where the trust money could no longer be ascertained. Equity had summoned up the courage since that case25 to go further and hold that tracing could occur in equity where trust money had been mixed with other money and it was difficult to identify the original trust money. Yet here there was no difficulty in identifying the original trust money. The same money belonging to A M Pelabon had been paid into Mr Hambrouck’s personal account. There had never been any other money in his bank account. He withdrew cheques on that account to pay them to his mistress. She paid them into her personal account and again, there was never any other money in that account. The money in Mlle Spanoghe’s account could, clearly, be ascertained as trust money. The process of tracing could thus be undertaken. The remedy in the case was for the claimant to have a claim for money had and received against Mlle Spanoghe.

Not all of the judges in the Court of Appeal reached the same conclusion, illustrating that tracing at common law remains a difficult concept. Scrutton LJ thought that tracing at common law was not possible on the facts, as the money had probably changed its identity when Mr Hambrouck paid it into his own bank account. Scrutton LJ thought that tracing was permitted in equity on the facts of the case.

That tracing at common law remains separate and distinct from tracing in equity and that it can only occur provided the original trust property remains ascertainable was emphasised by the Court of Appeal in Trustee of the Property of F C Jones & Sons (A Firm) v Jones.26

The facts concerned speculation in potato futures. A firm of potato growers was in financial difficulties. One of the partners of the firm gave his wife, the defendant, a cheque for £11,700 drawn on the firm’s account. She used the money to speculate on the London potato futures market. She was very successful at this and the original money grew into a sum of £50,760 which she paid into a deposit account that she had opened. The Official Receiver demanded the money, saying that the original sum had been released by the partnership in breach of trust to her as it had been released to her after the partnership was effectively bankrupt.The Official Receiver’s argument was that it was not the partnership’s money to release to the defendant as it became his when the partnership became bankrupt. As a proprietary action, the Official Receiver wished to trace the original sum into what it had turned into, thus ensuring a large ‘uplift’ if the whole successful investment could be traced.

All three Lords Justices in the Court of Appeal held that the defendant had no legal or equitable title to the money. The defendant held no ownership in the original money at all. The legal title was vested in the Official Receiver when the firm committed an act of bankruptcy. As such, its only claim was to trace the legal title in the original money into the profit which had been made. The £11,700 had not been mixed with any other money during the transactions and it was clearly traceable at common law. The Official Receiver could follow the £11,700 from the hands of the defendant into the broker who invested the money on the London potato futures market and from the profit generated there back to the account into which that profit had been paid.

The Court of Appeal held that the Official Receiver was entitled to all of the profit made by the defendant. That was due to the nature of the claim. The Official Receiver’s claim was a chose in action and it constituted the right not to claim merely the original amount but also the balance, whether or not that represented a profit or loss.

Tracing was the process which gave the Official Receiver the ability to follow the legal title in the original sum to the profit made. Nourse LJ pointed out that the remedy granted to the Official Receiver was that it had a right to claim for money had and received.

If the ability to ascertain the trust property has been lost, tracing will not be permitted at common law. This was emphasised in Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson.27

Agip (Africa) Ltd was part of the larger Italian oil giant, Agip SPA. It held permits to drill for oil in Tunisia. It also had a bank account at the Banque du Sud in Tunis. Its chief accountant, Mr Zdiri, fraudulently altered payment orders signed by directors of the claimant (the payment orders were instructions to the claimant’s bank to pay a certain recipient) to make payments to different recipients instead. The different recipients were companies controlled by the defendants. This fraud occurred over many years, but between March 1983 and when the fraud was discovered in January 1985, ![]() 10.5 million was fraudulently taken by this method. The action in the case concerned the ability of the claimant to recover nearly

10.5 million was fraudulently taken by this method. The action in the case concerned the ability of the claimant to recover nearly ![]() 519,000 — the final payment before the fraud was discovered — from the defendant.

519,000 — the final payment before the fraud was discovered — from the defendant.

The companies controlled by the defendants were shell companies which did not trade. They seem to have been established simply for receiving, and then distributing, the money fraudulently received from the claimant. The companies each had a bank account with Lloyds Bank in London. The procedure of transferring the money from the claimant to the companies is set out in Figure 13.1 below.

In giving the substantive judgment of the Court of Appeal, Fox LJ pointed out that tracing at common law did not depend on the existence of a fiduciary relationship. Liability depended simply on the fact of the defendant receiving the claimant’s money. As tracing at common law hinged upon receipt, it was irrelevant that the defendant had not retained the money. It also did not matter whether the defendant had acted honestly or not.

But what was essential for tracing to occur at common law was that the money had to be clearly identified in the defendant’s hands. This was not the case here. The money had been mixed in the New York clearing system. The original payment order had been taken into the Banque du Sud. That bank then instructed Lloyds Bank to credit the companies’ accounts. Lloyds Bank duly did so, but because of the time difference between the US and the UK, it would be some time later that Lloyds Bank would be reimbursed the amount by which it had credited the companies’ accounts. Lloyds Bank therefore paid the companies with its own money — money that was different from that original payment order taken into the Banque du Sud. That payment order was mixed into the New York clearing system and then came out later from the clearing system to reimburse Lloyds Bank. The original money and the money which found its way to the companies controlled by the defendants was not the same. Consequently, tracing at common law could not be established.

The claimant did, however, successfully argue that tracing could be permitted in equity.28

The remedy at common law if tracing is successful

The remedy at common law is restitutionary in nature. It is that the claimant may bring an action against the defendant for money had and received. This is founded on principles of unjust enrichment. The defendant, through the misuse of the claimant’s money, has unjustly enriched himself at the claimant’s expense and should return the money to the claimant.

Such remedy was awarded by the Court of Appeal against Mrs Jones in Trustee of F C Jones & Sons (A Firm) v Jones where it was held that the claimant could claim the additional money that had been made with the original investment. That was due to the nature of the claim the claimant enjoyed. The claimant’s chose in action could be taken against the balance left in the account, whether that was greater or lesser than the original investment. As Lord Goff explained in Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale Ltd:29

‘tracing’ or ‘following’ property into its product involves a decision by the owner of the original property to assert his title to the product in place of his original property.

The claim for money had and received has existed for centuries. It is based upon a simple premise: the principle that the defendant cannot, in good conscience, retain the money he has received.30 Money had and received is a personal claim against the defendant.

In Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale Ltd,31 the House of Lords held that two defences might apply to such a claim. These are either that the defendant has acted in good faith and for valuable consideration — or is, in other words, a bona fide purchaser of a legal estate for value without notice (the so-called ‘equity’s darling’) — or where the defendant has innocently changed his position.

The facts concerned the activities of Mr Norman Cass, who was a partner in the claimant firm of solicitors. Unbeknownst to his other partners, he was a compulsive gambler and, between March and November 1980, he helped himself to over £323,000 from the firm’s client account (he was later to repay approximately £100,000 of this sum). He went to the defendant’s Playboy Club, in London, whereupon he converted the money to gambling chips, which he used to place bets. Some bets he won but ultimately the net amount of his losses amounted to nearly £151,000 which, on a different way of looking at the matter, were the winnings that the Club enjoyed from his custom. Mr Cass absconded but was brought to trial and convicted of theft. His firm, however, was anxious to recover the money he had misappropriated from its client account. The firm brought proceedings against the Club’s owners for money had and received in respect of the net amount stolen by Mr Cass from the client account: nearly £223,000. To arrive at this remedy, the firm sought to trace the money from their client account via Mr Cass to the Club’s owners.

The first issue for the House of Lords to resolve was who had legal title to the money taken from the firm’s client account. The firm needed to show that it had legal title, so it could trace that title into the hands of the defendants, the Club’s owners. The defendants argued that legal title to the money passed to Mr Cass immediately when it was withdrawn from the account as he had no authority from the rest of the partners to withdraw it.

Lord Goff was of the opinion that the firm did have legal title in the money. Before Mr Cass withdrew the money, the relationship between the bank and the firm was that of debtor and creditor: the bank owed a debt to the firm. This was a chose in action. The firm could have taken action at any point, if necessary, against the bank to enforce that chose in action. Due to this, the firm must have enjoyed legal ownership to the chose in action and hence to the money it represented. As the firm owned the legal title to the money, it could trace this money through Mr Cass to the defendants.

The defendants advanced two arguments as part of their defence:

[a] they maintained that when Mr Cass exchanged the money for their chips, they provided valuable consideration for his money. If he had received valuable consideration for the money, they owed the claimant nothing; and

[b] they said that a claim for money had and received could be denied by the court on broad grounds if the court felt that it would be unjust or unfair to order the defendants to repay the money to the claimant. Specifically, on the facts, the defendants argued that they had innocently changed their position as a result of receiving the money and it would be unfair to order them to repay it to the claimant.

The first argument was accepted by a majority of the Court of Appeal but rejected by the House of Lords. Lord Goff explained that s 18 of the Gaming Act 1845 rendered contracts for gaming or wagering void in English law. As such, there was no contract between the Club and Mr Cass. The Club had provided no consideration to Mr Cass in the form of a chance of winning. If Mr Cass’ bet was unsuccessful, the Club’s promise to him was only to pay him if his bet won and so was of no effect. If his bet won, due to the Gaming Act, Mr Cass would have no legal right to call for his winnings to be paid to him and in paying the winnings, the Club was making a gift of them to him.

As to the second argument, Lord Goff denied that the court had ‘carte blanche’32 to reject claims for money had and received simply on the basis that it might be unjust or unfair to the defendants. He said the claim could only succeed if the defendants had been unjustly enriched. Such a claim did not depend on any wrongdoing by the defendants to the claimant.

Lord Goff thought that a general defence of innocent change of position should be recognised in English law. This principle had already been recognised in other common law jurisdictions, such as the United States, Canada and New Zealand. The defence would be applicable where:

an innocent defendant’s position is so changed that he will suffer an injustice if called upon to repay or to repay in full, the injustice of requiring him to repay outweighs the injustice of denying the plaintiff restitution.33

Lord Goff was, however, unwilling to limit the defence to specific situations and preferred that it should be developed on a case-by-case basis. He did, however, confirm that the defence would not be available where a defendant had changed his position in bad faith, such as where the defendant had dissipated the claimant’s money knowing that doing so was wrong. He stated the defence as being open

to a person whose position has so changed that it would be inequitable in all the circumstances to require him to make restitution, or alternatively to make restitution in full.34

The fact that a defendant has just spent the money that he has been given would not, however, make the defence available to the defendant. The money might have been paid away in the ‘ordinary course of things’,35 which would not invoke the defence.

Applied to the facts, Lord Goff believed that the defendants should prima facie be liable in an action for money had and received for the amount of money that Mr Cass had taken to the Club less the amount the Club had paid him in winnings. That meant that the claimant could recover approximately £151,000. In respect of the remainder of the original £323,000 that Mr Cass had originally taken to the Club, the Club had innocently changed its position.

As can be seen, the defence of change of position is related to a broader balancing act as to whether it is fairer that either the claimant or defendant should lose out. In cases such as Lipkin Gorman v Karpnale Ltd, the court was involved in a difficult balancing act, given that both claimant and defendant were innocent parties of Mr Cass’ deception. In the end, the claimant did not recover all its losses but neither did the defendant have to pay out more than it had taken from Mr Cass. Such a decision, according to Lord Goff, ‘may not be entirely logical, but it is just’.36

Tracing in Equity

In Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson,37 Fox LJ explained the main difference between tracing at common law and in equity:

Both common law and equity accepted the right of the true owner to trace his property into the hands of others while it was in an identifiable form. The common law treated property as identified if it had not been mixed with other property. Equity, on the other hand, will follow money into a mixed fund and charge the fund.38

In this sense, therefore, equity offered greater scope to the process of tracing. The common law, as shown on the facts of Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson, would not permit tracing if the property had been mixed, which often occurred in a bank account. The property no longer remained clearly identifiable. This was summed up in a memorable dictum by Atkin LJ in Banque Belge pour L’Etranger v Hambrouck:39

But if in 1815 [in Taylor v Plumer] the common law halted outside the bankers‘ door, by 1879 equity had had the courage to lift the latch, walk in and examine the books: In re Hallett’s Estate.

Whilst tracing in equity offers a clear advantage over tracing at common law — in that tracing into mixed funds can occur — it also comes with an additional requirement that must be satisfied. It is that there has to be a fiduciary relationship which enables the claim in equity to arise. Equity enables the claimant to trace the beneficial interest in the property and to do that, the claimant must show that a fiduciary relationship exists under which he is entitled to an equitable interest in the property.

Equity allowed tracing to occur on the facts in Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson. There was a fiduciary relationship between Agip (Africa) Ltd and its chief accountant, Mr Zdiri. Such a relationship enabled the equitable interest in the money to be traced through the bank clearing system in New York, even though it was mixed there with other money.

In a typical trustee-beneficiary relationship, the fiduciary nature of the relationship is obvious between the parties. But it is this fiduciary relationship which gives rise to the equitable interest in the trust property being held for the beneficiary and enables the beneficiary to trace that trust property into another’s hands.

It is possible to use equity to trace into unmixed funds. This is where the equitable interest in the money had been kept clearly separate from other money. In such a situation, equity adheres to its maxim that it follows the law. The same result will be reached as if tracing had occurred at common law, which is that tracing will be permitted albeit this time it is the tracing of the equitable, as opposed to legal, interest.

It is really where money has been mixed that equity came into its own with regard to tracing.

Tracing in mixed funds: two innocent parties

Where money has been mixed with other money and there is some remaining in the bank account but it is insufficient to meet the demands of two or more creditors, the general rule is that the money that has been paid in first has been withdrawn first. This principle comes from Clayton’s Case.40 It is sometimes known as ‘first in, first out’

Suppose Francesca receives £500 from Anna on Monday and the same amount from Bernard on Tuesday. Francesca pays both amounts into the same bank account. On Wednesday, Francesca pays £500 to Clare.

The rule in Clayton’s Case deals with the £500 remaining in the account after the payment to Clare has been made. The rule states that the remaining money belongs to Bernard in equity: ‘first in, first out’. Anna’s money was paid in first and is therefore deemed to be withdrawn first when Francesca pays Clare on Wednesday. Bernard’s money remains untouched.

As can be shown, the rule of Clayton’s Case is merely a rule of convenience. It is essentially a rule of chance: Anna loses out simply because her money is deemed to be used first.

The facts of Clayton’s Case concerned whether a deceased former partner’s estate could be liable for a debt incurred before the partner died. It was a case which involved the consideration and discussion of principles of partnership and banking law, as the partnership in question ran a banking business.

The principle in Clayton’s Case was accepted as applying to fiduciaries in Re Hallett’s Estate.41 Jessel MR described the principle as a ‘convenient rule’42 but one which was effectively only a presumption, which would apply subject to particular evidence being led to the contrary. So ‘first in, first out’ could be disapplied if it could be proven on the facts of the case that it should not apply, as occurred in Re Hallett’s Estate itself.43

The principle from Clayton’s Case was applied in Re Stenning.44 Mr Stenning was a solicitor who paid both his clients‘ and his own money into the same bank account that he held at the Bank of England. When he died, his estate was insolvent and he owed more money than he had in the account. Mrs Sydney Smith was one of his clients. She claimed £448 from the account. Her claim, along with those of Mr Stenning’s other clients, was that Mr Stenning held their money on trust for them. The trust should operate to ‘ring fence’ their money so that they would be paid before Mr Stenning’s general creditors.

Mr Stenning had paid in Mrs Smith’s money — £448 — to the account in March 1890. By the end of August 1890, he had subsequently deposited other sums of money, belonging to his other clients, but had also withdrawn significant sums. His account had always been in credit for more than the money Mrs Smith claimed but not by enough money to repay all of his clients. Mr Stenning died on 1 November 1890.

North J held that Mrs Smith had no claim to the money she had paid Mr Stenning, despite his account being in credit for more than her claim. The actual decision in the case was that there was, on the facts, no trust of the money created, but that there was simply a loan of the money from Mrs Smith to Mr Stenning. However, as obiter dicta, North J thought that the money left in the account could not, on the principle coming from Clayton’s Case and Re Hallett’s Estate, belong to Mrs Smith. After Mr Stenning had paid her money into the account, he had paid in other clients‘ money. He had then withdrawn money. On the ’first in, first out’ principle, the withdrawals that he had made had made use of Mrs Smith’s money first, as it was the first to be paid in to the account. As such, she had no claim against the money remaining in the account, as her money had been used first.

Tracing in mixed funds: Where the trustee mixes his own money with a beneficiary’s

In this scenario, there are not two innocent parties: the trustee has mixed his own money with that of the beneficiary. If the principle in Clayton’s Case was to apply, then it would simply be down to mere chance as to which party would lose out. For example, suppose a trustee paid in £500 of a beneficiary’s money to his own bank account and added £500 of his own money. He then spends £500. The rule in Clayton’s Case would state that the trustee spent the beneficiary’s money first, leaving his own money untouched. Such a result would be unjust. It would enable the trustee to use another’s money for his own purposes with no effective sanction for the beneficiary, except for pursuing a personal remedy against the trustee.

The rule in Clayton’s Case does not apply to the situation where a trustee mixes trust money with his own money. The trustee’s personal money is deemed to be spent first. This was established in Re Hallett’s Estate.45

Mr Hallett was a solicitor and a trustee of some Russian bonds belonging to a Mrs Cotterill. Without her permission, he sold the bonds and placed the proceeds into his own personal bank account, in so doing, mixing Mrs Cotterill’s money with his own. He then withdrew money from the account, using the money for his own purposes. After his death, the account was in credit, with more money in it than represented the proceeds of sale from Mrs Cotterill’s bonds, but if Clayton’s Case was applied to the facts, it would result in Mr Hallett having spent Mrs Cotterill’s money before his own.

The Court of Appeal held that, in such a case, the principle in Clayton’s Case could not apply. The trustee had to be deemed to have withdrawn the money which he had a right to withdraw first, before he touched any other money. That would mean that he withdrew his own money first, before a beneficiary’s. Jessel MR gave the following example to explain his decision:

The simplest case put is the mingling of trust moneys in a bag with money of the trustee’s own. Suppose he has a hundred sovereigns in a bag, and he adds to them another hundred sovereigns of his own, so that they are commingled in such a way that they cannot be distinguished, and the next day he draws out for his own purposes £100, is it tolerable for anybody to allege that what he drew out was the first £100, the trust money, and that he misappropriated it, and left his own £100 in the bag? It is obvious he must have taken away that which he had a right to take away, his own £100.46

Clayton’s Case was a presumption which could only apply unless there was evidence led to the contrary against it. Such was a case where money was mixed between an innocent party and a non-innocent party, namely a fiduciary who had committed a breach of trust.

In Sinclair Investments (UK) Ltd vVersaillesTrade Finance Ltd (in administrative receivership),47 the defendant fiduciary argued that once money was mixed with that owned by the defendant, it became so unclear which money was which that tracing was not possible. It was impossible to tell which money was that of the claimant’s. The defendant argued that all of the money had simply disappeared into a ‘black hole’ or ‘maelstrom’.

In delivering the only substantive judgment in the Court of Appeal, Lord Neuberger MR rejected that argument. He said he accepted the general contention that for tracing to be successful, there had to be a ‘clear link’48 between the claimant’s property and the resulting asset into which the claimant claims the money has been put. He continued:

However, I do not see why this should mean that a proprietary claim is lost simply because the defaulting fiduciary, while still holding much of the money, has acted particularly dishonestly or cunningly by creating a maelstrom.49

Moreover, in such a situation where the fiduciary has mixed trust money with his own, ‘the onus should be on the fiduciary to establish that part, and what part, of the mixed fund is his property’.50

Once the claimant had shown that its money had been mixed by the defendant with its own, the burden of proof switched to the defendant to show that — on the balance of probabilities — the money in the account was not the claimant’s.

It is thus not open to a fiduciary to claim that the beneficiary’s money has simply been ‘swallowed up’ by his own money in the same account so that the ability to trace has been lost. The fiduciary is under an onus to prove that the mixed money is not trust money.

Tracing in mixed funds: Where a trustee purchases property with mixed funds

Suppose a trustee, having mixed trust money with his own, decides to purchase property with the mixed funds. If Re Hallett’s Estate applied to this position, it would result in the purchased property being owned by the trustee himself (because by the decision in that case, the trustee would be deemed to spend his own money first). This would be a surprising conclusion as it would provide an opportunity for trustees to breach trusts quite easily with the knowledge that tracing could not occur.

The High Court in Re Oatway51 held that in such a position, the beneficiary may successfully trace his money into the purchased property.

As can be seen, the facts of a number of these cases give solicitors a poor reputation! Mr Oatway was a solicitor who was trustee of a trust. In breach of trust, he advanced £3,000 to his co-trustee in return for security in the form of a mortgage. The mortgage was redeemed, to the amount of £7,000, which Mr Oatway paid into his own account.

From that account, Mr Oatway bought shares for £2,137 in the Oceana Company. They were sold for £2,474. Mr Oatway died insolvent. The co-trustee brought an action, arguing that the sum of £2,474 should be held for the trust. The problem with this argument was that Mr Oatway’s account had been in credit to the sum of £6,635 when the shares were purchased. It was, therefore, alleged that Mr Oatway bought the shares with his own money, following Re Hallett’s Estate.

Joyce J held that the shares belonged to the trust. He said that (i) if money was withdrawn by a trustee and invested by him and (ii) the remainder of the balance in the bank account had been spent by the trustee, then (iii) the trust could trace its money into the investment. The investment was trust property.

To the argument that Mr Oatway’s account was in credit when the shares were purchased and were therefore purchased with his own money, Joyce J held that Mr Oatway had never been entitled to withdraw the purchase money for the shares from the account before the trust money had properly been reinstated. The trust money had first priority in the account and that should have been repaid to the trust initially. Only after that was done could Mr Oatway have purchased property. As this was never done, the property purchased by Mr Oatway belonged to the trust.

It is of some academic debate as to whether Re Oatway conflicts with, or follows, Re Hallett’s Estate. Re Hallett’s Estate established that the trustee had to spend money to which he had a right before trust money. If applied to Re Oatway, that would result in the Oceana shares being held for the trustee personally. Yet the decision in Re Oatway was that the property bought by the trustee belonged to the trust. On one level, this seems to be a triumph of pragmatism over jurisprudence. On another, however, it is possible to see Re Oatway as following Re Hallett’s Estate. The policy behind both decisions is the same: to give the innocent beneficiary the right to trace their equitable interests into what remains of their original property.

Do you think that Re Oatway follows or contradicts Re Hallett’s Estate?

Tracing in equity: The remedy

If it is possible to trace mixed money in equity, the beneficiary is entitled to a remedy. The remedies were set out by Jessel MR in Re Hallett’s Estate.52

If no mixing of the beneficiary’s money with other money has occurred, equity’s remedy is to offer the beneficiary the choice of either the property itself (that is, what the trust property has turned into) or to have a charge over the property to the value of the trust money spent in acquiring the property.

If the beneficiary’s money has been mixed with other money, Jessel MR believed that the beneficiary could only have a charge (or ‘lien’) over the property to the extent of the amount of trust money spent in acquiring the property. The beneficiary could not have the property itself, because the property had not been purchased with only trust money. This was consid-ered further by the House of Lords in Foskett v McKeown.53

The facts initially concerned a scheme for the development of land in the Algarve, Portugal. Purchasers gave a total of £2.6 million to Timothy Murphy for the money to be used to build and develop a resort. Mr Murphy bought a life assurance policy and, in breach of trust, used £20,440 to pay two premiums for it. The policy paid £1 million when Mr Murphy died. The property development scheme in the Algarve was not carried out. Accordingly, the purchasers sought to trace their money into the life assurance proceeds. They wanted their remedy to be the whole of the £1 million paid out by the life assurance company. The problem with this argument was that as the purchasers’ money had been mixed with Mr Murphy’s own money, the dictum from Jessel MR in Re Hallett’s Estate provided that the purchasers could only have a charge over the proceeds to the extent of the amount spent in acquiring the policy. Thus the purchasers’ claim would be limited to £20,440.

Lord Millett described the action as a ‘textbook example of tracing through mixed substi-tutions’.54 There was an express trust under which Mr Murphy held the purchasers’ money in a bank account. He mixed the money with his own money and bought an insurance policy. The purchasers’ original money could be traced through to the eventual proceeds from that policy, which were paid to Mr Murphy’s children.

Lord Millett thought that there was no justification for limiting the beneficiary’s right to a charge over an asset if that asset had been bought using trust money mixed with the trustee’s own funds. He said:

Where a trustee wrongfully uses trust money to provide part of the cost of acquiring an asset, the beneficiary is entitled at his option either to claim a proportionate share of the asset or to enforce a lien upon it to secure his personal claim against the trustee for the amount of the misapplied money.55

It made no difference if the trust money was initially mixed with the trustee’s own money and an asset was then purchased or if, as on the facts of the case, the asset was bought over a period of time with the payments being made, on a sequential basis, from trust money and then the trustee’s own money.

Mr Murphy’s children could not claim that they were innocent of any wrongdoing in this case as a successful defence. As Lord Millett pointed out, the children were volunteers of Mr Murphy and they could stand in no better position than him, as they derived title to the money from him.

Prima facie the whole of the insurance proceeds were trust property as the policy had been bought partly with trust money. But Lord Millett said that in the case of money, it may be possible to have a pro rata division of the proceeds of the policy between the wrongdoer (or his children, in this case) and the beneficiaries.

The proceeds of the policy (£1 million) could be divided between the children and the purchasers in proportion to the contributions they had each contributed to the premiums of the policy. This was because the ‘policy’ in this case did not represent the strict contract of insurance between Mr Murphy and the insurance company. Instead it represented the chose in action that Mr Murphy enjoyed against the company in return for paying the insurance premiums. The purchasers were able to trace their money through the payment of the insur-ance premiums to the proceeds paid out by the insurance company. The purchasers’ beneficial interest arose as soon as Mr Murphy used their money to pay the insurance premium. They attained a share in the chose in action that he enjoyed against the insurance company because their money was partly used in acquiring that chose in action. The purchasers were entitled to the same proportion of the insurance proceeds as Mr Murphy had used in acquiring his chose in action against the insurance company.They were not to be limited to a lien over the proceeds, as Jessel MR had suggested in Re Hallett’s Estate.

The decision of the House of Lords was of benefit to the purchasers for they were able to claim a much larger share of the proceeds than in fact they had (unknowingly) contributed to the premiums. This was due to their ability to trace their money not only into the premiums but further into the proceeds from the policy. In addition, in stating that their remedy was not limited merely to a lien over their share of the proceeds, the House of Lords provided an effective, immediate, remedy for the purchasers.

Summary flowchart

The essential elements of tracing are summarised in the flowchart below.

Actions Against Strangers to the Trust

The discussion of tracing considered the ability to follow trust property and reclaim it from a recipient of it. Tracing at common law involved the trustee tracing the legal title; tracing in equity concerned a beneficiary, or someone else in a fiduciary relationship, tracing the beneficial title.

Another category of claim also exists if someone has not breached the trust themselves but has either assisted in the breach of trust or simply received trust property. These are claims against so called ‘strangers’ to the trust. There are two actions that equity permits:

[a] a claim of’accessory liability‘ (formerly ’knowing assistance56; and

[b] a claimof’recipientliability‘ (formerly’knowingreceipt’57

These claims are personal actions against the strangers to the trust. Both claims originate from a dictum of Lord Selborne LC in Barnes v Addy58 as quoted by Lord Nicholls in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan:59

[The responsibility of a trustee] may no doubt be extended in equity to others who are not properly trustees, if they are found … actually participating in any fraudulent conduct of the trustee to the injury of the [beneficiary]. But … strangers are not to be made constructive trustees merely because they act as the agents of trustees in transactions within their legal powers, transactions, perhaps of which a court of equity may disapprove, unless those agents receive and become chargeable with some part of the trust property, or unless they assist with knowledge in a dishonest and fraudulent design on the part of the trustees.

Key Learning Point

Accessory liability, then, is assisting in a breach of trust. Accessory liability can only arise when there has been a breach of trust and the accessory has actual knowledge of that breach. It is fault-based and depends on the accessory knowing that he has behaved dishonestly in assisting in the commission of a breach of trust.

Recipient liability occurs where a stranger to the trust receives trust property (or its proceeds which have been traced) or deals with it for his own use and benefit. This is a restitutionary-based claim and is not dependent on fault on the part of the stranger.

An example of how accessory or recipient liability can arise may be explained using the facts of Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson.

The claimant was defrauded out of millions of dollars by its chief accountant, Mr Zdiri. The money passed into Lloyds Bank in London and from there it went into the accounts of a number of companies, all of which seemed to be formed simply for the purpose of accepting the money. The three defendants in the case were the partners and an employee of Jackson & Co, a firm of accountants in the Isle of Man, who set up the companies on the instructions of a French client.

Agip’s claim was made against the three defendants for both recipient and accessory liability. Such claims were needed as it was not the defendants personally who received the money from the claimant but companies set up by them. The defendants were, conse-quently, strangers to the trust.

The claim for recipient liability failed at first instance, as the defendants had not received trust property personally. The claim for accessory liability was upheld at the Court of Appeal; the defendants had assisted, knowingly, in a fraudulent design.

Accessory liability

Accessory liability is a subject with which the highest courts have grappled over the last twenty years. As Fox LJ said in Agip (Africa) Ltd v Jackson,60 a person will be liable for accessory liability where he ‘knowingly’ assists in a ‘fraudulent design’ on the trustee’s part, even though he does not personally receive trust property.

As You Read

Accessory liability depends on the assistor to the breach of trust being dishonest. The courts have, over the last 20 years, grappled with (i) what ‘dishonest’ should mean in this context and (ii) what it is that the assistor has to ‘know’ about being dishonest. Look out for these two issues as you read this part of the chapter.

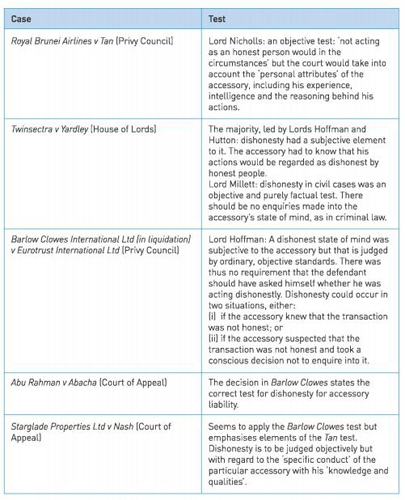

The first recent case where this was considered was Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan.61

The Privy Council’s first attempt to define ‘dishonesty’ …

Royal Brunei Airlines entered into an agreement with Borneo Leisure Travel (‘BLT’) to act as its agent for selling passenger and cargo transportation on its aircraft. Mr Tan was the managing director and main shareholder in BLT. BLT was obliged to account to the airline for all sales it made and, in return, was paid a commission. The sales money was to be held by BLT on trust for the airline, in a separate account. In fact, BLT paid money that it received from customers into its general bank account and, instead of paying the money to the airline, used some of the money for its own purposes, in breach of trust.

BLT breached the contract with the airline in failing to pay money to it. The airline termi-nated the contract and began an action to recover the money due. BLT went insolvent. The airline’s action was therefore against Mr Tan personally. The allegation was that Mr Tan had been guilty of accessory liability. He had assisted BLT in breaching the trust with the airline. The issue for the Privy Council was whether BLT had had a ‘dishonest and fraudulent design’ as it was only if this was the case and Mr Tan had known about it that he could be considered guilty of accessory liability.

In delivery the opinion of the Privy Council, Lord Nicholls lamented that the formulation given by Lord Selborne in Barnes v Addy had been applied so rigidly by the courts. He said that in the case of a breach of trust, a trustee would always be liable, unless excused either by an exemption clause or by the courts. The issue of a trustee’s liability did not, therefore, depend on the trustee being dishonest or fraudulent. Rather, it was the person accused of accessory liability that had to be shown knowing that in assisting a breach of trust, he was acting dishonestly and fraudulently. It should be the accessory’s state of mind that was in issue, not that of the trustee. It was the case that a trustee whom the accessory was assisting would, in fact, usually be dishonest but the real test was whether the accessory was dishonest or not.

Lord Nicholls defined ‘dishonesty’ as ‘not acting as an honest person would in the circumstances’.62 He said it was an ‘objective standard’.63 As such, individuals could not set their own standards of what was honest and what was not. It involved an assessment of ‘what a person actually knew at the time’.64 The honest person would be ‘expected to attain the standardwhich would be observed by an honest person placed in those circumstances’.65 The court would, however, have regard to the ‘personal attributes’ of the person, ‘such as his experience and intelligence and the reason why he acted as he did’.66

The question was whether a person dishonestly assisted in a breach of trust, not whether he ‘knowingly’ assisted in a breach of trust. Asking whether the breach was committed ‘knowingly’ involved questions of the type of knowledge required; the issue was simpler phrased as one of whether the person acted dishonestly or not.

On the facts, Mr Tan had acted dishonestly in helping with the breach of trust committed by BLT in using money for its own purposes instead of paying it straight to the airline. Mr Tan had known that the money should not have been used in that way.

The objective standard of dishonesty set out in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan was revisited by the House of Lords in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley.67

The House of Lords’ attempt to define ‘dishonesty’…

The facts concerned a loan from Twinsectra Ltd for the purposes of enabling Mr Yardley to purchase land. In breach of the trust that existed between Twinsectra Ltd and the solicitor receiving the loan money (Mr Sims), Mr Sims transferred the money to Mr Leach. Part of the money was in fact used to buy property but a substantial amount, over £357,000, was not. Twinsectra brought proceedings to recover that sum. Their claim against Mr Leach was that he had dishonestly assisted the breach of trust committed by Mr Sims in releasing the money early to him.

The majority in the House of Lords thought that Mr Leach was not guilty of dishonesty. Lord Hoffman thought that dishonesty required:

more than knowledge of the facts which make the conduct wrongful. [Dishonesty requires] a dishonest state of mind, that is to say, consciousness that one is trans-gressing ordinary standards of honest behaviour.68

Mr Leach had ‘buried his head in the sand’ according to Lord Hoffman.69 He thought that the loan money was at the free disposal of Mr Yardley. Such behaviour may have been misguided, but it did not constitute dishonesty.

Lord Hutton, with whom the other Lords in the majority agreed, thought that Lord Nicholls in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan had not defined ‘dishonesty’ as having entirely objective connotations to it. If he had, he would not have seen it necessary to have regard to the accessory’s personal experience and intelligence. Lord Hutton thought that Lord Nicholls had intended to define dishonesty as including knowledge by the accessory that he knew that what he was doing was dishonest, ‘dishonesty requires knowledge by the defendant that what he was doing would be regarded as dishonest by honest people … .’70

This, therefore, introduced a subjective element into the test for dishonesty and aligned it more closely to the test for dishonesty in criminal law, as developed by Lord Lane CJ in R v Ghosh.71 Lord Hutton pointed out, however, that an accessory could not escape liability simply by arguing that he did not believe his actions to be dishonest if he knew that they would ‘offend the normally accepted standards of honest conduct’.72

In his dissenting speech, Lord Millett argued that the test for dishonesty in criminal law focused on the defendant’s state of mind. Yet dishonesty in civil matters had previously focused on the defendant’s outward conduct instead. Dishonesty came from the defendant’s wrongdoing, not what was in his mind. He did not believe that Lord Nicholls in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan had brought in a test of dishonesty equivalent to the criminal standard, requiring an assessment of the defendant’s state of mind. He thought Lord Nicholls’ test for dishonesty focused solely on the defendant’s conduct. His state of mind was thus irrelevant. It was of no consequence that the defendant had not thought about what he was doing and that he had given no consideration as to whether he was acting honestly or not. Lord Millett thought that considering the accessory’s state of mind had no place in a civil action. Mens rea was a part of criminal law, not civil. Outward wrongdoing was sufficient to constitute dishonesty.

The two divergent views of Lord Nicholls’ opinion in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan were not helpful. Lord Millett’s dissenting speech is carefully crafted and logically argued. On the other hand, the views of the majority perhaps pragmatically achieved the more palatable result on the facts of the case.

Lord Nicholls’ words as interpreted in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley were reviewed again by the Privy Council in Barlow Clowes International Ltd (in liquidation) v Eurotrust International Ltd.73

The Privy Council’s second attempt at ‘dishonesty’ …

The case concerned an investment scheme set up by Barlow Clowes International Ltd, which was run by Peter Clowes. He purported to offer high rates of return in an investment scheme. Investors deposited a total of £140 million with the company, but most of the money was used by Mr Clowes personally, to fund his own business ventures and extravagant lifestyle. In 1988, the investment scheme collapsed. Mr Clowes was convicted and imprisoned. Some of the £140 million was paid away through a company called International Trust Corporation (‘ITC’), which acted through its two directors. ITC, controlled by a Mr Henwood, made several payments to businesses controlled by Mr Clowes. The liquidator of Barlow Clowes International Ltd brought proceedings alleging that ITC and Mr Henwood dishonestly assisted Mr Clowes in the breach of trust by misusing investors’ money. Mr Henwood was found not guilty of dishonestly assisting in the breach of trust on appeal in the Isle of Man. The liquidator of Barlow Clowes appealed against that decision to the Privy Council.

In delivering the opinion of the Privy Council, Lord Hoffman confirmed that the trial judge had summarised the law correctly. She had referred to Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan and had said that dishonesty required a dishonest state of mind by the person assisting in the breach of trust. That could occur either through knowing that the transaction was not honest or being suspicious that the transaction is not honest coupled with a ‘conscious decision’74 not to make enquiries about the transaction which would confirm it to be dishonest. Lord Hoffman said:

Although a dishonest state of mind is a subjective mental state, the standard by which the law determines whether it is dishonest is objective. If by ordinary stand-ards a defendant’s mental state would be characterised as dishonest, it is irrelevant that the defendant judges by different standards.75

Mr Henwood argued that he could not be characterised as dishonest. His defence was that he felt himself obliged to carry out Mr Clowes’ instructions. He never gave any conscious thought as to whether the money he was being instructed to invest belonged to Mr Clowes or was really money belonging to other investors who believed their money was being invested in other securities. He relied on part of Lord Hutton’s speech in Twinsectra Ltd v Yardley where Lord Hutton had said that dishonesty required that ‘the defendant must himself appreciate that what he was doing was dishonest by the standards of honest and reasonable men’76 and that dishonesty requires knowledge by the defendant that what he was doing would be regarded as dishonest by honest people …77

Lord Hoffman acknowledged that there might have been ‘an element of ambiguity’78 in Lord Hutton’s remarks in Twinsectra but what Lord Hutton meant in the decision was that the defendant’s

knowledge of the transaction had to be such as to render his participation contrary to normally acceptable standards of honest conduct. It did not require that he should have had reflections about what those normally acceptable standards were.79

Mr Henwood’s knowledge was, on the facts, contrary to normally acceptable standards of honest conduct. His knowledge of Mr Clowes and his companies meant that he was at least suspicious about where Mr Clowes’ money came from. But Mr Henwood chose not to investigate further. That was contrary to normally acceptable standards of honest conduct. No additional requirement existed that Mr Henwood had to reflect upon what normally accepted standards of honest conduct were.

Two years later, the Court of Appeal in Abu Rahman v Abacha80 believed that the decision of the Privy Council in Barlow Clowes represented a correct statement of the law of dishonesty in England.

Lord Hoffman’s opinion in Barlow Clowes International Ltd (in liquidation) v Eurotrust International Ltd maintained that Lord Hutton’s speech in Twinsectra followed the test of dishonesty set out in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan. It is hard to see how it did. The test set out in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan seems to have been objective with some elements of subjectivity included in it. The majority in Twinsectra suggested that it was not possible to have a purely objective test of whether a person’s state of mind was dishonest or not — by definition, when considering a person’s state of mind, what he subjectively believed had to creep in somewhere. The decision in Barlow Clowes sought to prevent Twinsectra being taken to its logical conclusion which was to argue that the subjective element meant that the defendant had to have consciously considered whether his conduct was dishonest. Had that argument been accepted, it would have raised the threshold for the test of dishonesty to a high level to be satisfied. The rejection of this argument in Barlow Clowes was probably right but it was undoubtedly wrong to say that the majority in Twinsectra followed the test laid down in Royal Brunei Airlines v Tan.

The Court of Appeal’s attempt at ‘dishonesty’: Barlow Clowes applied

This issue of dishonesty has been revisited recently by the Court of Appeal in Starglade Properties Ltd v Nash.81

Roland Nash was the sole director and shareholder of Larkstore Ltd. It developed houses on a site in Hythe, Kent, relying on a report into the suitability of the land prepared by Technotrade Ltd. Unfortunately, a landslip happened and the houses were damaged. The house owners sued Larkstore. Larkstore, in turn, wanted to sue Technotrade Ltd, but their report was prepared for the previous owners of the site, the claimant company. So the claimant, Larkstore and Mr Nash entered into an arrangement whereby the claimant would transfer its contractual rights to Larkstore, in return for which Larkstore would hold any successful litigation proceeds on trust for itself and the claimant in equal shares. Larkstore went insolvent, after its claim had been settled by Technotrade. In breach of trust, Larkstore distributed the money to its other creditors, the majority of which had a connection to Mr Nash. The claimant sued Mr Nash for dishonestly assisting in the breach of trust.