Chapter 12

Remedies for Breach of Trust Against Trustees

Chapter Contents

Monetary Remedies Available for Breach of Trust

Exclusion of Liability for Breach of Trust

Defences and Mitigating Circumstances for Breach of Trust

As shown in Chapters 8 and 9, being a trustee is an onerous responsibility and is subject to numerous duties, of both a fiduciary and non-fiduciary nature. Breach of one of these duties is something that a trustee should obviously guard against. This chapter is the first of two to consider a beneficiary’s remedies for breaches of trust. It focuses on the remedies the beneficiary might pursue against the trustee whilst Chapter 13 considers the remedies the beneficiary might use to recover lost trust property and personal remedies against non-trustees.

As You Read

As you read this chapter, look out for the following key issues:

![]() what a breach of trust is, when a trustee is liable, the extent of a trustee’s liability and how the beneficiary must show that he has suffered loss in order to take successful action against a trustee;

what a breach of trust is, when a trustee is liable, the extent of a trustee’s liability and how the beneficiary must show that he has suffered loss in order to take successful action against a trustee;

![]() how a trustee may rely on an exemption clause to exclude his liability for breach of trust; and

how a trustee may rely on an exemption clause to exclude his liability for breach of trust; and

![]() the defences and mitigating circumstances that a trustee may rely on in an action taken against him for breach of trust.

the defences and mitigating circumstances that a trustee may rely on in an action taken against him for breach of trust.

Breach of Trust

A trustee is subject to a number of duties, of both a fiduciary and non-fiduciary nature.1 A breach of trust will have occurred when ‘the trustees made decisions which they should not have made or failed to make decisions which they should have made’.2

In Nestle v National Westminster Bank plc3 Staughton LJ recognised that it may be difficult to prove that either a trustee had made a decision when he should not have done so, or failed to make a decision when he should have done so. The difficulty of proving either event, however, was not a reason to absolve a beneficiary from proving it.

Suppose Scott sets up a trust in his will, settling £100,000 on trust for the benefit of Vikas during his life with remainder to Ulrika. He appoints Thomas as his trustee.

An animal lover all his life, Scott sets out in a term of the trust that Thomas must not invest any money into organisations that test medicines on animals.

Whilst administering the trust, Thomas becomes aware that shares in MedicalResearch plc are increasing in value. This is a company that uses animals in medical research. He therefore decides to purchase a large amount for the benefit of the trust.

Suppose after purchasing the shares in MedicalResearch plc, the shares then fall significantly in value. The beneficiaries might decide to take action against Thomas in order to recover their loss.

In purchasing the shares, Thomas prima facie committed a breach of trust. It was a term of the trust that he must not invest in such a company. The beneficiaries may sue him for breach of trust to recover the Loss to the trust fund.

Who is liable for a breach of trust?

If only a sole trustee exists, clearly that trustee must be liable for every breach of trust that he commits. If there are two or more trustees, the general rule remains that only the trustee who has committed the breach of trust will be liable for it. However, all of the trustees may be liable for any breach of trust that occurs, even if it was only committed by one of them, in the following circumstances:

[a] if one trustee leaves a matter to a co-trustee without enquiring as to what has happened and a breach of trust occurs. For example, in Hale v Adams,4 trust property was sold and the money received by only one of the trustees. The money was then lost by that trustee. The trustee who did not receive the money made no enquiry of the receiving trustee about what had happened to the sale proceeds. The court held that both trustees were liable for breach of trust. Effectively, both trustees had received trust property when the property was sold and even the ‘innocent’ trustee should be responsible for its loss;

[b] if one trustee is aware of a breach of trust by a co-trustee and does nothing to remedy it (Styles v Guy5); or

[c] if a trustee allows the trust funds to remain in the sole control of a co-trustee. In English v Willats,6 trust property was sold but the sale proceeds were paid only to one of two trustees. The non-receiving trustee was held liable to make good the loss to the trust fund.

A further example of one trustee allowing a co-trustee to manage the trust fund by themselves occurred in Bahin v Hughes.7

The facts concerned a trust established in the will of Robert Hughes. He settled £2,000 on trust for the money to be held for the benefit of his wife for her lifetime and afterwards for his children. The trustees were Eliza Hughes, Mr and Mrs James Burden and Mr Edward Edwards.

Eliza managed the trust on a daily basis. She advised the beneficiary and the other trustees that a good investment would be for the money to be lent by way of mortgage over eight houses in Wood Green, Middlesex. It transpired, however, that all of the properties over which the money was lent were leasehold. At that time, the types of investments in which trust funds could be placed were curtailed and the terms of the trust did not allow investment in leasehold properties.

The leasehold houses were not sufficiently valuable to be used as security for the money lent by way of the mortgage and so the trust fund suffered a loss. The beneficiaries brought an action for breach of trust against all of the trustees, on the basis that the trustees should never have invested in an unauthorised investment. Mr Edwards felt that he should not be liable for the loss suffered by the trust, as the decision to invest was taken only by Eliza Hughes. He therefore claimed an indemnity from her for any money he had to pay to the trust fund.

The two questions for the court were (i) was Mr Edwards liable for the breach of trust and (ii) could he claim an indemnity from the acting trustee, Eliza Hughes?

The Court of Appeal held that Mr Edwards was responsible for the breach of trust. The court took the view that the trust was entitled to look to the trustees to repay the loss. As a trustee, Mr Edwards could not be treated any differently from any of the other trustees. As regards the position between the trustees and the beneficiaries, all of the trustees were responsible for the loss.

The position between the trustees themselves was more difficult. The court concluded that Mr Edwards should not be entitled to an indemnity from Eliza Hughes. The court felt that, even though Eliza had made the investment, Mr Edwards was just as much at fault for the loss occasioned to the trust fund as she was. He had done nothing to enquire about the investment, let alone prevent it, until six months after the mortgages had been entered into.

Bahin v Hughes confirms that the courts view who is liable for a breach of trust from the beneficiaries’ standpoint. The beneficiaries are the innocent parties if a breach of trust has occurred. They should be permitted the greatest possible number of opportunities to take action against to restore the trust fund to its pre-breach position. In that regard, the liability of trustees is joint and several: the beneficiaries may sue either all of the trustees or any of them individually for their loss.

With regard to indemnities between trustees, the decision confirms that, prima facie, a trustee is not liable to indemnify another trustee against loss which the first trustee may have caused. That remains the general principle. That is because all trustees are equally responsible for administering the trust. If one mismanages the trust so that loss is caused, it is probable such mismanagement has only occurred because other trustees have allowed it to happen through their inactivity. For a trustee, therefore, inactivity is just as much a risk as taking incorrect positive action.

The issue of a ‘guilty’ trustee indemnifying an innocent trustee for breach of trust that the former has committed has moved on since Bahin v Hughes. Section 1 of the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978 gives a general right to a person who is jointly and severally liable to receive a contribution (as opposed to complete indemnity) from the guilty party. The contri-bution that the guilty party is to make to the innocent party is to be adjudged on a ‘just and equitable’ basis by the court.8 The court may decide, however, that such contribution could amount to a ‘complete indemnity’.9

Suppose that Mr Edwards cLaimed a contribution from ELiza Hughes towards the compensation he had to pay to the trust fund. If the facts of Bahin v Hughes were repeated nowadays, it wouLd be open to the court to decide that Mr Edwards shouLd receive a contribution from Eliza to represent the breach of trust that she committed. The Act does not alter who the beneficiaries may sue so the beneficiaries would retain the right to sue both Eliza and Mr Edwards jointly or simply one of them.

The court might order Eliza to make a contribution to Mr Edwards for the compensation he has had to pay to the trust fund, on the basis that the investment in the leasehold properties was effectively all Eliza’s doing.

But there is nothing in the Act to compel the court to order that one trustee makes a contribution to the other. Remember that on the facts of Bahin v Hughes, the court decided that Mr Edwards was as guilty of the breach of trust as Eliza Hughes. If that remained the decision of the court, Eliza would not have to contribute to the sum Mr Edwards would have to pay to the trust fund. The 1978 Act merely gives the court more flexibility to apportion the loss between the trustees; it does not compel the court to do so.

A trustee is not always liable for breach of trust …

For a trustee to be liable for breach of trust, it must be shown that the trust fund has suffered loss. A true loss must be shown to have occurred from the actual decisions that the trustee took. It is not enough to demonstrate that the trust fund might possibly have increased more in value had the trustee taken different decisions, as Nestle v National Westminster Bank plc10 demonstrates.

The case concerned a trust established by William Nestle in his will. William died in 1922, but established a trust benefiting his family. The defendant was the trustee. In 1986, the claimant, William’s granddaughter, Edith Nestle, became the beneficiary entitled to the remainder interest under the trust. At that point in time, the trust fund was worth £269,203. The claimant alleged, however, that the trust fund should have been worth over £1 million had the defendant not committed various breaches of trust. She claimed that the trustee had breached the trust by failing to act with proper care and skill. In particular, she alleged that the trustee had failed to keep the investments under review, had misinterpreted its investment powers under the terms of the original trust and the Trustee Investments Act 1961 and had failed to keep an appropriate balance between the capital and income interests. Accordingly, the claimant claimed compensation for the difference between what the fund was actually worth and what she alleged it should have been worth.

The trustee was, of course, subject to the duty originally set out by Lindley LJ in Re Whiteley:11

to take such care as an ordinary prudent man would take if he were minded to make an investment for the benefit of other people for whom he felt morally bound to provide.

The trustee was also bound to balance the interests of both the life tenants and the claimant as the remainderman.12 Professional trustees, such as the defendant, were subject to a higher duty of care and skill than a lay trustee, as they charged for their time and skill in administering the trust.13

All three Lords Justices in the Court of Appeal did not believe that the trustee had showered itself with glory in the administration of this particular trust. The trustee had misinterpreted its original power of investment in the trust. It believed that it could only invest the trust funds in a limited range of companies but, on a true construction of its powers, it could in fact have invested the funds in any type of company. As the trustee had very wide powers of investment specifically granted to it in the trust instrument, the restrictions on investments introduced by the Trustee Investments Act 1961 did not apply. Overall, Dillon LJ thought it ‘inexcusable’14 that the trustee had not sought legal advice over what it could invest in. Staughton LJ put it in these black-and-white terms:

Trustees are not allowed to make mistakes in law; they should take legal advice, and if they are still left in doubt they can apply to the court for a ruling.15

Both Lords Justices also thought the bank failed to review the investments regularly.

However, the trustee’s failings were not enough to make the bank liable to pay compensation. The question for the court to decide was:

whether the onus remains on the [claimant] to prove loss for which fair compensation should be paid, or whether it is enough for her to claim compensation for loss of a chance …that she would have been better off if the equities had been properly diversified.16

All three members of the Court of Appeal held that the claimant had to prove that she had suffered actual loss. The difficulty was that the claimant could offer no proof that the trust fund had suffered any loss. ‘Loss’ would be occasioned, according to Leggatt LJ, where the trust fund failed to make a gain less than that which would have been made by a prudent businessman investing the trust fund. No evidence could be led which showed that the bank had caused such a loss.

All that the claimant could show was that, with the benefit of hindsight, other investments the bank may have made would have given her (as remainderman) a better return. That was not sufficient. Staughton LJ confirmed that hindsight could not be used against a trustee to show that the trustee could perhaps have produced a greater return for the trust fund than actually occurred, ‘the trustees’ performance must not be judged with hindsight: after the event even a fool is wise, as a poet said nearly 3,000 years ago’.17

It also had to be recognised that investment policies naturally changed over a period of time, to deal with issues brought about by wider economic views. Investing in shares, for example, had been seen to be particularly risky in the 1920s and 30s and it was not appropriate to look back and criticise the trustees for their choice of investments with today’s values in mind, where investing in shares is considered to be much less adventurous.

The decision in the case is perhaps best summarised by the words of Leggatt LJ, that ‘[a] breach of duty will not be actionable, and therefore will be immaterial, if it does not cause loss’.18

Monetary Remedies Available for Breach of Trust

Background to monetary awards

Traditionally, equity saw no role for itself in awarding damages: that was the function of the common law. Equity’s role was to provide a remedy which would actually enforce equitable obligations themselves. Hence the courts of equity developed their own peculiar remedies, such as decrees of specific performance and injunction. The remedy of specific performance enables a party to compel another party to adhere to the terms of a contract. An injunction usually prevents a party from committing an act. These remedies are considered in depth in Chapter 17.

With these specific remedies in mind, equity’s original preference for a remedy against a trustee who had committed a breach of trust was to order the trustee to restore the actual property to the fund.19 If the trustee was not able to restore the specific property to the trust fund, the trustee could, instead, pay a monetary sum to the value of the loss the fund suffered.20 This evolved into a second right of requiring the trustee to pay equitable compensation to the individual beneficiary.

Strict common law issues of causation, foreseeability of loss and remoteness of damage do not readily apply to equitable compensation. All there has to be in equity is, according to Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Target Holdings Ltd v Redferns (A Firm),21

some causal connection between the breach of trust and the loss to the trust estate for which compensation is recoverable, viz. the fact that the loss would not have occurred but for the breach.

‘Compensation’: Restoration v equitable compensation

Traditionally, equity made a distinction between the two remedies of restoring the trust property and equitable compensation. The terminology can be confusing. Both remedies are examples of compensation in the broadest sense of making good a party’s loss. ‘Restoration’ refers to equity holding the trustee to account to the trust fund for a loss that he has caused to the trust. The remedy is for the trustee to restore to the trust fund either the property that he has caused to be taken from it, or a monetary payment instead. The trust fund must be restored to its full value as long as the trust subsists. ‘Equitable compensation’ refers to compensation payable by the trustee to a beneficiary instead of to the trust fund and is usually payable after the trust has come to an end.

Key Learning Point

The right to equitable compensation is the right for the beneficiaries to sue the trustee personally for loss that he has caused to the trust fund.

By contrast, restoration of the trust property is a right that the beneficiaries enjoy against the trust property itself. It is said to be a right in rem: a right ‘in the thing itself’.

The liability of the trustee to restore the trust fund and/or pay equitable compensation was discussed by the House of Lords in Target Holdings Ltd v Redferns (A Firm).22

The facts concerned a commercial property transaction of two plots of land in Birmingham. Mirage Properties Ltd agreed to sell the plots to Crowngate Developments Ltd. The purchase was not straightforward and went via a series of other companies, with the price increasing in stages at each step in the transaction.

The defendants were the solicitors acting for Crowngate, as well as the claimant (it is entirely usual for the same firm of solicitors to act for both buyer and lender in such a transaction). The claimants were the lenders for the purchase of the land, who were fully aware of all of the companies involved in the property transaction.

The claimant sent the loan money to the defendants in readiness for the purchase of the land to occur. Redferns had the implied authority of the claimant to pay the money across to Crowngate when it purchased the property.

The problem was that Redferns paid the loan money away too early: before the purchase of the land was completed. This was a breach of trust. Redferns admitted this but argued that the claimant did have a mortgage — secured by a legal charge — over the two properties in Birmingham. In this sense, therefore, the claimant had attained what it originally wanted to attain from the transaction: its money had been lent and secured by way of a legal charge.

Crowngate became insolvent and so was unable to repay the loan lent to it by the claimant. As mortgagee, the claimant could — and did — sell the two plots of land, but only for £500,000. It therefore sought to recover its £1.2 million loss from the defendant.

The claimant argued that when Redferns paid out the mortgage money in breach of trust, they were liable to restore the trust fund in the sum of the whole of the money that they paid out. The claimant further argued that the common law principles of causation did not apply and that it made no difference that the claimant had achieved its objective in securing a mortgage over the land.

The actual litigation in the case concerned the claimant’s application for summary judgment against the defendant.

Glossary: Summary judgment

Summary judgment is where judgment is given against a party because it is categorically clear that the party has committed a wrong, such as a breach of contract or breach of trust. There is consequently no need for a full trial to determine the issue.

At first instance, Warner J thought that the claimant had a very good claim for summary judgment for the breach of trust, but nonetheless gave the defendant permission to defend the action on the condition they deposited £1 million in court. The defendant appealed against his refusal to give them unconditional permission to defend the claim.

By a majority, the Court of Appeal dismissed Redferns’ appeal. Giving the leading judgment, Peter Gibson LJ held that, in general, the liability of a trustee for breach of trust was not to pay damages but instead the correct measure of liability was either:

[a] to restore the trust fund to the value of what had been lost. This was to be the entire amount of the fund’s loss such that the fund would be reconstituted with the total amount it had in it immediately before the breach of trust occurred; or

[b] pay the beneficiary equitable compensation for his loss. The beneficiary was to be returned to the position he was in but for the breach of trust. Thus causation was itself broadly relevant but the common law rules of causation were not relevant.

On the facts, the Court of Appeal held that as money had been paid by a trustee to a third party stranger, there was an immediate loss to the trust fund which could only be remedied by the trustee restoring the same amount to the fund. The court gave judgment to the claimant for £1.49 million less the £500,000 that the claimant had made when it sold the land as mortgagee. Peter Gibson LJ felt that equity could be sufficiently flexible to take into account the amount the claimant had made when it subsequently sold the land, after the breach of trust had occurred. Redferns appealed to the House of Lords.

Lord Browne-Wilkinson delivered the only substantive opinion of the House of Lords. He stated that the principles underlying the common law’s award of damages and equity’s award of compensation were two-fold and were the same: (i) the defendant’s act must cause the damage and (ii) the claimant had to be put back into the position he would have been in had the damage not been committed. It had to be shown that the defendant was at fault for causing the claimant’s loss. If no loss could be shown, the beneficiary would enjoy no right to recompense.

Lord Browne-Wilkinson rejected the first conclusion reached by the majority of the Court of Appeal that, in a case such as this where the commercial purpose of the transaction had come to an end, the whole of the trust fund should be restored if a breach of trust had occurred. When Redferns paid the money, the commercial purpose of the transaction came to an end. From that point on, there was no obligation to force Redferns to reconstitute the entire trust fund. Such an obligation would lead to over-compensation for the beneficiary, for the whole £1.7 million would need to be reconstituted by Redferns, despite the fact that the claimant’s loss was ‘only’ £1.2 million as it had successfully sold the land for £500,000.

The trustee’s liability to restore the trust fund by reconstituting it was only appropriate in the case of a traditional family trust, where the fund was held for multiple beneficiaries (such as to A for life, remainder to B) and they all had to benefit from being compensated. Restoration of the entire loss reflected that all beneficiaries needed to be compensated for the breach of trust. It was inappropriate in a modern, commercial use of the trust where the trust had come to an end and where there was only one beneficiary. Restoration of the trust fund was not the appropriate remedy here.

Do you think Lord Browne-Wilkinson’s decision in Target Holdings Ltd v Redferns (A Firm) is compelling? Look back to Chapter 2 and the uses to which trusts are put in today’s world. Could restoration of the trust fund not be appropriate in some modern, commercial trusts?

As regards the Court of Appeal’s second argument of paying compensation to a beneficiary, Lord Browne-Wilkinson did not agree that ‘one “stops the clock” at the date the moneys are paid away’23 when assessing the measure of compensation. He acknowledged that as soon as a trustee commits a breach of trust causing loss to the trust fund, the beneficiary has a right of action against him. But that did not mean that the measure of equitable compensation due to the beneficiary was also fixed at that point in time. Instead, the amount of compensation was to be measured at the later date of the trial. It was at that later point that an amount could be awarded which would put the estate or beneficiary back into the position they were in before the breach was committed. Lord Browne-Wilkinson quoted with approval from the judgment of McLachlin J in the decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Canson Enterprises Ltd v Boughton & Co:24

The basis of compensation at equity, by contrast, is the restoration of the actuaL value of the thing Lost through the breach. The foreseeable value of the items is not in issue. As a result, the Losses are to be assessed as at the time of trial, using the fuLL benefit of hindsight.

Taking this into account, at this stage, Redferns were entitled to defend the claim against the claimant. It could not be proven, without a full trial into the issue, that the claimant had actually suffered any loss as a result of Redferns’ actions. The claimant had lent the money and had ultimately secured it by way of a legal charge. However, Lord Browne-Wilkinson ended his opinion by saying obiter that whilst this was the strict result, it was probable at trial that the claimant would be able to show a causal link between Redferns’ breach of trust and the claimant’s loss. If this was the case, then the claimant’s remedy would be equitable compensation of £1.2 million: the loss of £1.7 million less the value of the land of £500,000 which the claimant had recovered when it sold the two plots. Such an amount was the amount of loss at the date of the trial, as opposed to the loss of £1.7 million when the breach of trust occurred.

Summary

‘Compensation’ in the broadest sense in equity consists of two rights that the trust enjoys: the trustee may be liable to account to the trust fund for the loss suffered or, alternatively, may have to pay equitable compensation to the beneficiaries personally.

The trustee’s liability to restore the loss to the trust fund he has caused it was said by Lord Browne-Wilkinson in Target Holdings Ltd v Redferns (A Firm) to be the beneficiary’s ‘only right’25 of monetary remedy against a trustee in the case of a traditional trust where the trusts were still subsisting. When a traditional trust comes to an end, the beneficiary is not usually entitled to have the trust fund restored. There is no need, as the beneficiary becomes absolutely entitled to the trust property. As such, he is instead entitled to equitable compensation should the trustee have breached the trust.

Equitable compensation is a personal right of action against the trustee to compensate the beneficiary for the breach of trust he has caused. It must be shown that the trustee caused the loss but the detailed common law requirements on causation do not apply. In more modern trust examples where the trust has arisen — and since ended — due to the commercial nature of a transaction, the decision in Target Holdings Ltd v Redferns (A Firm) suggests the courts are more inclined to award equitable compensation against the trustee rather than order him to restore the trust fund. Equitable compensation will be assessed as the loss to the trust fund at the date of trial, taking into account any reduction in the loss that may have occurred.

Making connections

The measure of compensation for breach of trust is interesting. An express trust is formed on the broad notion of a contract between the settlor and the trustee that the equitable interest should be held on trust for the beneficiary. But the measure of compensation is based more upon tortious principles than contractual ones. When paying damages to a beneficiary, the measure is said to be returning the beneficiary to the position he would have been in but for the breach of trust. This is similar to how damages in tort are assessed: they are based on returning the innocent party to the position he was in before the tort was committed against him.

Awarding equitable compensation on tortious principles is logical. It has to be correct that the beneficiary is returned, insofar as money can do so, to the position he was in before the breach of trust occurred.

Restoration v equitable compensation: A strategic choice

Assuming actions for either restoration or equitable compensation are available, the beneficiary should bear in mind the following principles as to whether to pursue an action in rem for restoration of the trust property or personally against the trustee for equitable compensation:

[a] As equitable compensation is a personal right of action against the trustee, it is only worth pursuing such a remedy if the trustee is solvent. If the trustee is insolvent, whilst the wronged beneficiary may still sue the trustee, he will simply wait with the rest of the trustee’s creditors before he is paid and will receive no preferential treatment as a beneficiary of a trust. On the other hand, as restoration of the trust property is a right in rem against the property itself, this will enable the beneficiary to claim the actual property of the trust or a sum of money representing it. If the trustee has gone insolvent, this means that the beneficiary will effectively sidestep the queue of the trustee’s other creditors by pursuing the trust property itself.

[b] Restoration of the trust fund will usually be appropriate if the trustee is in breach of a fiduciary duty.26 For example, making a secret profit will mean that the trustee holds that gain on constructive trust for the benefit of the actual trust. The profits must be restored to the trust.

[c] Equitable compensation is normally appropriate for breach of a non-fiduciary duty.27 For instance, if the trustee has failed to account to the beneficiaries with information about the trust, it would be hard to see how the trustee could be liable to restore anything to the trust. The more appropriate — and only — action in such circumstance would be for the trustee to pay equitable compensation to the trust.

Where the two remedies are available, the trust must choose between restoration and equitable compensation

It is normally the case that action cannot be taken against the trustee for both the restoration of the trust fund as well as equitable compensation. The two remedies are alternatives to each other.28 This was made clear by the decision of the Privy Council in Tang Man Sit v Capacious Investments Ltd.29

The facts concerned 22 houses built, as a joint venture, by Mr Tang and Capacious Investments Ltd in Kam Tin, Yuen Long, New Territories. Mr Tang owned the land on which they were built and Capacious provided the finance for their construction. The houses were finished in 1981. There was an agreement between the two parties that 16 of the houses would be transferred by Mr Tang to Capacious but this never happened. Instead, as the houses were empty, Mr Tang proceeded to let all 16 of them out as homes for the elderly. Capacious did not know of these lettings. The houses were over-occupied and deteriorated in value, as they were not kept in good repair. Capacious therefore brought an action against Mr Tang for, inter alia, a declaration that it was entitled to the equitable interest in the houses from when the agreement to transfer them was entered into, an account of the secret profit made by Mr Tang by letting the properties out and compensation for breach of trust.

What Capacious was claiming was that it wanted both the secret profit made by Mr Tang to be restored to the trust fund and equitable compensation for the breach of trust that Mr Tang had committed by letting the properties out without its knowledge or permission. Capacious argued that it was entitled to compensation for breach of trust because had Mr Tang not breached the trust in failing to transfer the properties to them and letting the properties out, Capacious could itself have let the properties. The Court of Appeal of Hong Kong held that Capacious was not entitled to both remedies. They were alternatives. Capacious had accepted the account of secret profits (HK ![]() 1.8 million) and was now precluded from also claiming compensation for breach of trust. But Capacious was able to claim an additional amount of HK

1.8 million) and was now precluded from also claiming compensation for breach of trust. But Capacious was able to claim an additional amount of HK ![]() 11 million compensation representing the diminution in value of the properties. Both parties appealed to the Privy Council.

11 million compensation representing the diminution in value of the properties. Both parties appealed to the Privy Council.

Delivering the opinion of the Judicial Board, Lord Nicholls agreed with counsel for Mr Tang that there was a difference between restoration of the trust fund by an account of a secret profit and an award of compensation. Restoration of the trust fund by an account of the secret profit was where a party chose to accept however much money the guilty party had made for the secret use of the trust property. Compensation for breach of trust would, on the other hand, equal the amount the claimant himself would have made for the same period had he been able to use the property himself. Lord Nicholls described the two remedies as ‘alternative, not cumulative’.30

The facts of this particular case were different from normal, however. The trial judge had ordered that Mr Tang deliver both an account of his secret profit and pay compensation for breach of trust. The judge had not required, as he should have done, Capacious to choose which remedy it wanted. When Mr Tang therefore duly handed over the HK ![]() 1.8 million as an account of his secret profit, it could not be said that in accepting that sum, Capacious chose that as their remedy as they were ignorant of their need to make a choice. It would be unfair on Capacious if they were now said to have accepted that sum as their remedy in the case, given that the award for compensation was much larger.

1.8 million as an account of his secret profit, it could not be said that in accepting that sum, Capacious chose that as their remedy as they were ignorant of their need to make a choice. It would be unfair on Capacious if they were now said to have accepted that sum as their remedy in the case, given that the award for compensation was much larger.

The Privy Council held that an account of a secret profit and compensation for breach of trust were alternative remedies. It was only on the particular circumstances of this case, caused by the trial judge’s error in awarding both to Capacious, that Capacious was held to be entitled to both.

Exclusion of Liability for Breach of Trust

If a trustee would otherwise be prima facie liable for breach of trust, it would not be unnatural for him to seek to protect himself in some way.

An exemption clause may either exclude entirely, or otherwise restrict, a trustee’s liability for breach of his duties in carrying out the trust. The clause may exclude or restrict liability for breach of a fiduciary or non-fiduciary duty. Such clauses are usually included in trust deeds where professional trustees are appointed to administer the trust. At first glance, it appears that the inclusion of an exemption clause by a professional trustee results in the trustee having the best of both worlds: charging for their time and skill in administering the trust, whilst at the same time stating that they are not to be liable, or that their liability will be limited, if they breach the trust. On the other hand, the ability of a trustee to benefit from an exemption clause helps to make the role of trustee more attractive and generate competition in the market of professional trusteeship.31

The leading case on the subject is the decision of the Court of Appeal in Armitage v Nurse.32 Paula Armitage enjoyed an interest under a trust of a piece of land and £30,000. She brought an action for breach of trust against the trustees for failing to prioritise her interests as a beneficiary over interests of other members of her family, who were not beneficiaries under the particular trust. Her allegation was that this breach of trust resulted in her suffering loss.

The trustees sought to rely on an exemption clause in clause 15 of the trust deed, which stated that no liability would attach to them unless it was ‘caused by [the trustees’] own actual fraud’.

In giving the only substantive judgment of the court, Millett LJ held that the meaning of the words of the exemption clause was that it absolved the trustees from liability provided they had not acted dishonestly. The trustee, relying on clause 15, could be excluded from liability for breach of his duties, ‘no matter how indolent, imprudent, lacking in diligence, negligent or wilful he may have been, so long as he has not acted dishonestly’.33 Millett LJ did not believe that the trustee had acted dishonestly, but was guilty of gross (serious) negligence. The next issue for the court was, therefore, whether it was permissible in English law for a trustee to rely on an exemption clause excluding liability for gross negligence.

Making connections

In your studies of contract law, you have probably considered that it is not possible for liability to be excluded for a fraudulent misrepresentation. Fraudulent misrepresentations are those that are essentially made dishonestly. The judgment of Millett LJ in Armitage v Nurse that a trustee cannot exclude liability for being dishonest is a related concept: both involve attempts to exclude dishonesty which, as a matter of policy, should not be permitted or encouraged.

Millett LJ did not believe that any previous English or Scottish decision had decided as a matter of policy that a trustee could not rely on an exemption clause which would absolve his responsibility for gross negligence. Clause 15 would be given effect, therefore, to absolve the trustees of responsibility ‘for all loss or damage to the trust estate except loss or damage caused by their own dishonesty’.34 As Paula did not go so far as to allege that the trustees had been dishonest, the clause was sufficient to absolve them for liability for the loss to the trust fund.

The case established that there was no reason in terms of public policy why a clearly worded exemption clause could not exclude or restrict liability for trustees at least as far as negligence was concerned. Millett LJ believed that a clause which went further and sought to exclude the trustees’ liability for fraud or dishonesty would not be effective and it would mean that the deed did not effectively create a trust:

The duty of the trustees to perform the trusts honestly and in good faith for the benefit of the beneficiaries is the minimum necessary to give substance to the trusts …35

Millett LJ did provide a warning in obiter comments about the use of trustee exemption clauses:

the view is wideLy heLd that these cLauses have gone too far, and that trustees who charge for their services and who, as professionaL men, wouLd not dream of excLuding LiabiLity for ordinary professionaL negLigence shouLd not be abLe to reLy on a trustee exemption cLause excLuding LiabiLity for gross negLigence.36

He did, however, believe that for such clauses to be denied effect was a step that only Parliament could take.

The issue of the extent to which trustee exemption clauses should be permitted has been considered twice by the Law Commission in recent years.37 In making its final recommendations for reform, the Law Commission took into account the responses to its earlier Consultation Paper which included:

[a] general unease about the use of trustee exemption clauses, especially if the settlor was unaware of the clause in the trust deed or its meaning;

[b] the idea that, ultimately, it should be the settlor’s decision whether or not to include an exemption clause for the trustee’s benefit rather than that decision being imposed upon the settlor by Parliament; and

[c] that the Commission’s notion that instead of relying on an exemption clause, trustees should insure against being sued for breach of duty may be difficult to implement in practice due to the possible unavailability or high cost of such insurance.

As a result, the Law Commission recommended what might be considered at first glance to be something of a ‘light-touch’ idea of regulation. Its key recommendation38 was that the settlor should be made aware of ‘the meaning and effect’ of any exemption clause that the trustee wished to be included in the trust deed. This would only take the form of a rule of practice. This means that a breach of the rule would be enforced not through the courts but through the trustee’s or trust draftsman’s professional body. Being subject to the possibility of receiving a sanction from a professional body was thought to be sufficient impetus for the professional draftsman to make a settlor aware of an exemption clause.

The Society of Trust and Estate Practitioners (STEP) had, by the time of the Law Commission’s finaL report, aLready adopted its own ruLe obLiging its members to draw a settLor’s attention to a trustee exemption cLause.

The ruLe appLies where a STEP member either ‘prepares, or causes to be prepared’ a trust or wiLL which (i) contains a charging cLause or gives the STEP member a financiaL interest in the trusteeship and (ii) contains a trustee exemption cLause.

The rule provides that STEP members are obliged to ensure that they use ‘reasonable endeavours’ to advise the settlor of the existence of the exemption clause and that the STEP member has ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing the settlor ‘has given his full and informed acceptance’ to the clause before he signed the trust deed.

In a statement given by the Ministry of Justice on 14 September 2010, the government accepted the Law Commission’s recommendations in its final report.

Such regulation of exemption clauses is to be welcomed. Sanction by a professional body for not advising the settlor of the meaning and effect of an exemption clause should act as a sufficient deterrent against breach of the rule. The issue is whether the Law Commission and the government should have gone further in perhaps recommending the abolition of trustee exemption clauses altogether. It must be asked whether a settlor really has any practical choice but to agree to an exclusion clause if he wants his trust to make use of the skills that the appointment of a professional trustee brings. Pragmatically, due to the divergence of views in its consultation exercise, any stronger recommendation would have been impossible for the Law Commission to make. No doubt this is an area likely to see further change in future as trustees may attempt to use exemption clauses of wider application, albeit with the settlor’s alleged blessing.

Defences and Mitigating Circumstances for Breach of Trust

Once it has been established that a trustee has committed a breach of trust that has resulted in a loss being occasioned to the trust fund, the trustee is prima facie liable either to restore that loss to the fund or to pay equitable compensation to the affected beneficiary.

The trustee may, however, be able to take advantage of one or more of the following defences that may be open to him, depending on the facts of the case:

[a] the rule in Re Hastings-Bass39 (although that rule has been severely curtailed by the decision of the Court of Appeal in Futter v Futter40);

[b] indemnity by a co-trustee;

[c] indemnity if the breach of trust is committed by a solicitor-trustee;

[d] indemnity if the breach of trust is committed by a beneficiary-trustee;

[e] participation by or consent of a beneficiary in the breach of trust;

[f] release by the beneficiary;

[g] impounding the interest of a beneficiary;

[h] the Trustee Act 1925, s61;

[i] the Limitation Act 1980, s21; or

[j] the doctrine of laches.

Each of these must now be considered.

The (curtailed) rule in Re Hastings-Bass

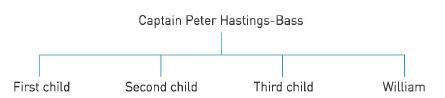

In 1974, the Court of Appeal decided in Re Hastings-Bass that trustees could enjoy a second bite at the cherry if they had made a decision that subsequently turned out to have the consequences which they were originally intending to avoid. The relevant parties in Re Hastings-Bass are illustrated in Figure 12.1.

The case concerned a trust that had been established in 1947. The trust property was originally to be held on a protected life interest for Captain Peter Hastings-Bass and after his death for such of his sons as he should appoint. Captain Hastings-Bass had four children and he appointed his son William to benefit from the trust. After the appointment had occurred, the trustees (using their power under s32 of the Trustee Act 1925) transferred £50,000 from the trust to a second trust that had been set up for William’s benefit. This was done to save the estate duty payable on Captain Hastings-Bass’ death. The problem with this course of action was that the new trust infringed the rules against perpetuity, according to the later decision of the House of Lords in Re Pilkington’s Will Trusts41 (because William was not a ‘life in being’ at the date the 1947 trust had been created).

The Inland Revenue argued that, as the rules against perpetuity had been infringed, the £50,000 remained in the original 1947 trust. The trustees argued that, although the rules against perpetuity had, unwittingly, been infringed, a valid life interest in the £50,000 in William’s favour had still been created. Thus no estate duty was due as the beneficial interest had still been assigned from Captain Hastings-Bass to William.

The Court of Appeal held that no estate duty was due to be paid. The trustees had advanced the money to William’s second trust using their powers under s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925. Such an advancement could still take effect as, in itself, it did not infringe the rules against perpetuity. The advancement was free-standing and was not touched by the rules against perpetuity. The trustees’ exercise of their discretion under s 32 was valid and the advancement of the money to William was effective.

The Court of Appeal laid down that the court should not generally interfere with the exercise of a trustee’s discretion, even if the exercise of that discretion did not have the full effect that the trustee intended, as had occurred here. The only times the court should interfere was when:

(1) what he [the trustee] has achieved is unauthorised by the power conferred upon him, or (2) it is cLear that he wouLd not have acted as he did (a) had he not taken into account considerations which he shouLd not have taken into account, or (b) had he not faiLed to take into account considerations which he ought to have taken into account.42

The decision of the Court of Appeal in the case was, of course, designed to address the particular issue that had been presented to the court: William’s second trust had failed but the question was whether the power of advancement exercised by the trustees under s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925 could still be valid. The court held it could.

The problem was that subsequent decisions took the dictum of Buckley LJ and applied it as the ratio decidendi of the case. Buckley LJ’s words were used to justify that the court would not interfere with the exercise of a trustee’s discretion unless the trustee had accomplished something he plainly could not or:

[a] he had taken into account matters he should not have taken into account; or

[b] he had failed to take into account matters he should have considered.

The turning of Buckley LJ’s words into ratio was achieved in the decision of Warner J in Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans43 where he described Buckley LJ’s dictum as ‘a principle which may be labelled “the rule in Hastings-Bass” ‘.44 The ‘principle’ was set out by Lloyd LJ (in the High Court) in Sieff v Fox45 as:

Where trustees act under a discretion given to them by the terms of the trust, in circumstances in which they are free to decide whether or not to exercise that discretion, the court will interfere with their action if it is clear they would not have acted as they did had they not failed to take into account considerations which they ought to have taken into account, or taken into account considerations which they ought not to have taken into account.

What the ‘rule’ in Hastings-Bass meant was that if the trustees’ decision had unintended consequences — such as it subsequently gave rise to a large charge to taxation — the trustees could apply to the court to have their decision set aside on the basis that they had failed to take into account matters they should have done or had taken into account factors they should have ignored. For trustees, the ‘rule’, as developed, was effectively a ‘get out of jail free’ card. No cases after Hastings-Bass went to the Court of Appeal or higher as trustees were content to take advantage of the ‘rule’ as interpreted in Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans. HM Revenue & Customs did not take issue with the ‘rule’ for many years even though invariably the application of it meant that their tax revenue declined a little.

The ‘rule’ has, however, been reviewed and heavily curtailed by the recent decision of the Court of Appeal in Futter v Futter46 which was the first case since Hastings-Bass itself in which HM Revenue & Customs intervened.

The facts concerned two trusts established for the benefit of Mark Futter, his wife and their children. The trusts were offshore. When money is moved back into UK jurisdiction, a taxation charge will normally arise. These trusts were expected to be subject to a high charge to capital gains tax (CGT) when the money was brought back into the UK.

The trustees, therefore, attempted a pre-emptive strike by, in the case of the first trust, enlarging Mark’s life interest so that he became entitled to the whole trust absolutely. In relation to the second trust, the trustees exercised their power of advancement under s 32 of the Trustee Act 1925 by appointing £12,000 to each of Mark’s three children. Mark and his children would, prima facie, be liable to pay CGT, but the intention was to offset their gains by losses they incurred by selling other property.

Unfortunately, their solicitors made an error. Section 2(4) of the Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992 provides that losses cannot be offset against gains made in such circumstances. The result was that a large gain was made and a high amount of CGT was due. The trustees therefore instituted proceedings seeking a declaration that their transactions were void, relying on a part of the Hastings-Bass ‘rule’ — namely, that they had failed to take into account considerations which they should have taken into account and so the court should interfere with their decision and declare the transactions void.

In delivering the leading judgment of the Court of Appeal, Lloyd LJ held that the ratio of Hastings-Bass was limited to the particular circumstances that the court had had to consider in that former case. The ratio was that, when considering exercising their powers of advancement, trustees had to consider whether any sub-trust created by it did operate to benefit the person receiving the advancement. Just because the other intended consequences had not happened (such as effective creation of a whole new trust in Hastings-Bass) did not mean that the advancement could not take effect to the recipient in its own right. The exercise by the trustees of their power of advancement would still be good. As Lloyd LJ pointed out,47 the issue for the court to decide in Hastings-Bass was narrow: it was merely concerned with whether a true advancement had occurred or not. Any wider words used by Buckley LJ could not, therefore, be considered to be part of the ratio.

Lloyd LJ felt that subsequent cases (in particular Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans) had focused too much on the more general words of Buckley LJ in Hastings-Bass and had considered those words to be the ‘principle’ arising from the case. The Court of Appeal overruled Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans and sought to state the limitations of when the original rule in Hastings-Bass might be used.

According to Lloyd LJ, the correct principle was that:

[a] The trustees’ failure to take into account (a) something they should have considered or, alternatively, (b) taken something into account that they should not have done rendered their acts voidable, not void. This meant that in future only beneficiaries would have standing to challenge the trustees’ decisions as opposed to trustees wishing to have a ‘second bite of the cherry’ by setting their earlier decision aside.

[b] Beneficiaries could only show that the trustees’ actions were voidable if they could show that the trustees had breached their fiduciary duties to the trust.

[c] It would be a breach of a fiduciary duty for trustees to fail to take into account a relevant matter (such as failing to consider an adverse taxation consequence as a result of the trustees’ decisions).

[d] If the trustees obtained and followed professional advice on the issue, the trustees would not be in breach of their fiduciary duties. If there was no breach of fiduciary duties, the beneficiaries would have no claim against the trustees for breach of trust. The trustees’ actions would not, therefore, be voidable and capable of being set aside. They would have to stand.

CuriousLy, LLoyd LJ recognised that there wouLd be a distinction between the trustee who sought and foLLowed professionaL advice and the one who simpLy bLundered on by himseLf. Where professionaL advice was sought and foLLowed, there was to be no breach of fiduciary duty and, therefore, no right of action against the trustee to have the decision set aside. But where no advice was sought, that might be a breach of fiduciary duty and an action might occur against the trustee for breach of fiduciary duty, Leading to the trustee’s decision being set aside.

Do you think this is necessariLy Logical?

Applying the ‘correct principle’ to the facts of the case, the issue for the Court of Appeal was whether the trustees failed to have regard to the relevant taxation consequences of their decisions and whether that could constitute a breach of fiduciary duty on their part.

The Court of Appeal held that the taxation consequences of their decisions were relevant factors for the court to take into account but that the trustees had sought and followed professional legal advice before making the advancements to the beneficiaries. It could not be said that there was a breach of fiduciary duty by the trustees. They had acted on proper advice. The real problem lay not with the trustees but in that the advice was incorrect.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Futter v Futter has both legal and pragmatic consequences. Legally, it essentially reverses the enlargement of the Hastings-Bass principle as developed in Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans and takes it back to the original position in Hastings-Bass itself. Trustees may not now seek to set aside decisions they have taken on the basis that they failed to take into account a relevant matter, or took into account an irrelevant matter when they made the original decision, unless it can be shown that they committed a breach of a fiduciary duty. This will not be possible if the trustees obtained and followed professional advice.

Pragmatically, trustees under the Hastings-Bass rule as interpreted in Mettoy Pension Trustees Ltd v Evans enjoyed a ‘get out of jail free’ card. They could set aside their decisions if they subsequently turned out to be wrong. That will no longer be the case, unless it can be demonstrated that they breached their fiduciary duties when reaching the decision. Beneficiaries are not, however, deprived of a remedy by the decision in Futter v Futter. Instead, their remedy now will normally be to sue the trustees for negligence in place of breach of trust.48

Indemnity by a co-trustee

As already mentioned,49 s 1 of the Civil Liability (Contribution) Act 1978 provides that an ‘innocent’ party may receive a contribution from a ‘guilty’ party for the loss that the guilty party has caused. This means that if an innocent trustee is obliged to restore the trust fund or pay equitable compensation, he may claim a contribution from the guilty trustee who has actually caused the loss to the trust fund. If both trustees are equally guilty of the breach of trust, the contribution will usually be for half of the loss sustained by the trust if one trustee has been obliged to restore the entire loss to the trust fund.

Whether one trustee is bound to offer a complete indemnity to the other will depend on ‘what is just, as between the two, and this depends on what they have respectively done’ according to Lindley LJ in Chillingworth v Chambers.50

But the awarding of such an indemnity will, it is suggested, rarely be appropriate.51 In Bahin v Hughes,52 Fry LJ thought the courts should be ‘very jealous’ of holding one trustee generally liable to indemnify another due to the risk of the trustees concentrating more on arguing between themselves over who is liable to the trust rather than focussing on undertaking their duties. In Bahin v Hughes,53 Cotton LJ gave the example of one trustee effectively stealing money from the trust for his own personal use. In such a situation, the guilty trustee would be liable to indemnify the other trustee should the innocent one have to restore the loss to the trust fund. Whilst refusing to set down any limits of when an indemnity would be ordered against a guilty trustee, the Court of Appeal in that case thought that it was only appropriate where a guilty trustee obtained a personal benefit from the breach of trust or, where there was a relationship between the trustees which justified the court in holding that the guilty trustee was solely responsible for the breach of trust. One such relationship is where one of the trustees is a solicitor.

Indemnity if the breach of trust is committed by a solicitor-trustee

If one of the trustees is a solicitor and the other trustees rely on the solicitor’s advice, the solicitor-trustee may be liable to indemnify the other trustees should they be sued for breach of trust. This was established in Lockhart v Reilly.54

The indemnity owed by the solicitor-trustee is based on the notion that the other trustees have followed the solicitor’s advice but the advice was negligent. As a matter of policy, it is probably right that lay trustees would follow the advice of such a professional trustee and should, if that advice turns out to be wrong and causes the trust loss, be indemnified if they are sued for that loss.

Indemnity if the breach of trust is committed by a beneficiary-trustee

The general position is that a trustee who is also a beneficiary will be liable to indemnify the other trustee for loss occasioned to the trust. Moreover, the indemnity must be for the extent of the beneficiary’s interest in the trust property and not just for the extent of the gain the trustee-beneficiary has received: Chillingworth v Chambers.55

In this case, the claimant and defendant were the trustees of the will of John Wilson. He left money on trust for the benefit of his wife for life and thereafter for his five children in equal shares. The trust contained a power to invest by way of granting mortgages over leasehold property. The claimant was also the husband of one of John’s daughters.

During the administration of the trust, the two trustees decided to lend £8,650 to a builder who was constructing eight leasehold houses. In 1881, the claimant became beneficially entitled to a share in John’s trust as his wife (one of John’s daughters) died. In 1883, the claimant brought an action for the removal of the defendant as a trustee. The action failed but the court ordered accounts to be drawn up in relation to the trust. During this process, the eight mortgages were sold on but there was a deficit of £1,580. The court ordered that both trustees were equally liable for that loss to the trust fund. The loss was actually made good from the money that the claimant was now beneficially entitled to. The issue for the Court of Appeal was whether the claimant could claim an indemnity from the defendant. The claimant alleged that the defendant had previously made loans to the builder but had not been repaid. He said that the defendant had induced him to advance the trust money to the builder so that the builder could repay the defendant’s personal loans. The claimant’s case was that the defendant effectively held the trust money himself and that he should, therefore, bear all of the loss that the fund had sustained.

The Court of Appeal did not accept that there had been a breach of trust in lending the money to the builder. The builder was merely obliged to repay the money lent, as any contract for a loan would entail. As no breach of trust had occurred by the defendant, there was no obligation on him to indemnify the claimant.

The decision backfired on the claimant. The Court of Appeal held that the claimant was entitled to no indemnity from the defendant. As Lindley LJ explained:

If I request a person to deaL with my property in a particuLar way, and Loss ensues, I cannot justLy throw that Loss on him. Whatever our LiabiLities may be to other peopLe, stiLL, as between him and me, the Loss cLearLy ought to faLL on me.56

Moreover, the Court of Appeal decided that it was the claimant who had to bear the loss. The loss was not to be limited to the benefit the claimant had received but the indemnity the claimant had to provide was to the extent of his share of the beneficial interest in the trust property.

Participation by or consent of a beneficiary in the breach of trust

If a beneficiary himself is party to, or consents in, a breach of trust committed by a trustee, the trustee is not liable to make good the breach of trust. To consent to a breach of trust, the beneficiary must:

[a] be aged 18or older and have mental capacity;

[b] freely consent to the breach of trust having occurred; and

[c] have the necessary knowledge required of the breach having happened to consent to it.

It is the third requirement — the type and extent of knowledge that the beneficiary must possess — that the courts have considered in most detail.

The issue was considered by Wilberforce J in Re Pauling’s Settlement Trusts.57 The facts concerned alleged breaches of trust that Coutts & Co had made when administering a trust set up in 1919 by two parents for their lives with remainder to their four children. The family had always lived beyond their means. A considerable number of advancements were made by the trustee to the two eldest children, Francis and George; some of the money advanced was used for the benefit of the family as a whole by, for example, purchasing a home in the Isle of Man and paying off the family’s overdraft. The allegation against the trustee was that it had breached its duty of balancing the interests of the life tenants (the parents, who had the overdraft liability) and the remaindermen (the children, whose capital interest was being advanced to pay off the overdraft). The children claimed that the trustee should repay the amounts it had advanced in breach of trust.

Wilberforce J held that the advancement to purchase the house in the Isle of Man was a breach of trust as the property had been placed into the parents’ names without Francis’ and George’s consent. Other advances that were placed into the parents’ bank account to pay off their overdraft also constituted a breach of trust as advancing money for such a reason was not a solid exercise of the trustee’s fiduciary power of advancement.

But despite these prima facie breaches of trust, Wilberforce J then said he had to consider whether he could hold the trustee liable for them. He thought not. He held that the court’s duty was to:

consider aLL the circumstances in which the concurrence of the [beneficiary] was given with a view to seeing whether it is fair and equitabLe that, having given his concurrence, he shouLd afterwards turn round and sue the trustees …58

In terms of the knowledge that the beneficiary had to possess when giving his consent to a breach of trust occurring, Wilberforce J held that it was not necessary for the beneficiary to know that he was agreeing to a breach of trust. All that was needed was that the beneficiary had to understand fully what he was agreeing to. There was no requirement that the beneficiary should benefit personally from the breach of trust.

On the facts, it was held that the trustee had to replace the money advanced used to purchase the home in the Isle of Man as such advancement had occurred in breach of trust without Francis’ and George’s independent consent. The trustee was not liable to restore to the trust the other sums advanced as Francis and George had known about them, were both aged over 21 and had given their free consent to them.

Release by the beneficiaries

The decision in Re Pauling’s Settlement Trusts shows that it is possible for a beneficiary to consent to a breach of trust and if that occurs, the beneficiary cannot then take action against the trustee to recover sums lost as a result of that breach.

The facts of Re Pauling’s Settlement Trusts showed the beneficiary consenting to the breach of trust as it occurred. It may be that the beneficiary is initially unaware of the breach of trust but becomes aware of it after it has happened. In such a situation it is, in some circumstances, open to the beneficiaries to give their consent to the breach of trust after the event. Such consent would operate to release the trustee from liability from the breach of trust.

In order to release the trustee from a breach of trust, the beneficiaries must all act together and must all be over 18 years of age and be mentally capable. They must also have knowledge of all of the facts of the breach of trust.

A trustee might wish to be formally released by beneficiaries for any potential breaches of trust he may have committed if he wishes to retire as a trustee. Any trustee retiring will usually continue to be liable for any breaches of trust he may have committed whilst a trustee, so beneficiaries should, it is suggested, be reluctant to grant such release.

Impounding the interest of a beneficiary

Impounding the interest of a beneficiary originally applied only if that beneficiary was also a trustee who had committed a breach of trust.

If a trustee-beneficiary had committed a breach of trust, his interest was liable to be impounded by the court. That meant that he was not entitled to enjoy his beneficial interest until he rectified the breach of trust. His interest, then, was taken as a type of insurance policy for the other beneficiaries: if the trustee made good his breach of trust, he was entitled to enjoy the interest; if not, he forfeited it. The court remains entitled to impound the trustee’s beneficial interest under its inherent jurisdiction as a successor to the Court of Chancery.59 The ability to impound a beneficial interest was widened by s 62 of the Trustee Act 1925. Section 62(1) provides:

Where a trustee commits a breach of trust at the instigation or request or with the consent in writing of a beneficiary, the court may, if it thinks fit, make such order as to the court seems just, for impounding all or any part of the interest of the beneficiary in the trust estate by way of indemnity to the trustee or persons claiming through him.

Section 62 applies to any beneficial interest, where the beneficiary has asked the trustee to breach the trust. The power to impound under the section means there is now an effective sanction against any beneficiary who requests or consents to a breach of trust. But the court has a wide discretion over whether to order the impounding of the beneficiary’s interest. If such an order is made, the beneficiary will be deprived of their equitable interest in order that it can be used to make good the loss to the trustee arising from the breach of trust. Before ordering the impounding of the beneficiary’s interest, the court must be satisfied that the beneficiary knew all of the facts surrounding the breach of trust but the beneficiary need not be aware that a breach of trust would arise.60

Trustee Act 1925, s 61

Section 61 of the Trustee Act 1925 provides a statutory defence that a trustee may use. The section provides that the court has a discretion to excuse a trustee ‘either wholly or partly’ from liability for the breach of trust if the trustee ‘has acted honestly and reasonably and ought fairly to be excused for the breach of trust’.

Section 61 is often pleaded as a defence by a trustee who is prima facie liable for a breach of trust but the fairly stringent requirements of the section mean that it is rarely successful. It is often the twin requirements that the trustee must have acted both (i) honestly and (ii) reasonably that will prevent the court from exercising its discretion to relieve the trustee from liability. For example, in Re Pauling’s Settlement Trusts, as part of their defence, Coutts & Co pleaded that they should be absolved from liability under s 61. Wilberforce J was quite prepared to accept that the bank had acted entirely honestly in advancing the money to the children but the bank’s actions were not reasonable in advancing the money where the breaches of trust were found. His judgment also makes clear that s 61 contains a third separate requirement if it is to be used successfully: liability ought fairly to be excused by the court. This third requirement will always be a value judgment on the facts of the case and Wilberforce J did not think it was right that the bank should have been excused from liability on the facts of this particular case.

Commenting on virtually identical New Zealand provisions to s 6161 in the High Court of Wanganui in Berube v Gudsell,62 McGechan J confirmed that the onus of proof of establishing this defence lay on the trustees. His view was that the court should be slow to allow a trustee to claim this defence:

the court granting reLief, and thus depriving a beneficiary of redress, shouLd act cautiousLy. A cavaLier attitude to trust administration shouLd not be encouraged.

Limitation Act 1980, s 21

Section 21 of the Limitation Act 1980 provides a general defence that a trustee who has committed a breach of trust may be able to rely on. It provides,63 generally, that an action for a breach of trust must be commenced against the trustee within six years from when the breach occurred. There are exceptions to this six-year time limit:

[a] Where the beneficiary is entitled to a future interest under the trust, the time limit commences not from the breach of trust but from when the beneficiary’s interest falls into their possession.

[b] No time limitation is prescribed for taking action for a fraudulent breach of trust or, alternatively, to recover trust property (or its proceeds) from a trustee where that property or proceeds remain in his possession.

It is equity’s doctrine of laches that governs when a beneficiary may take action against a trustee who has committed a fraudulent breach of trust or who has taken trust property and retains it (or its proceeds).

The doctrine of laches

Laches is the doctrine of equity that prevents equity intervening and providing a remedy to a beneficiary after more than a reasonable time period has passed since the cause of action originally arose. It is based on the equitable maxim that ‘delay defeats equities’. The policy behind the doctrine is that as time passes, it is unfair that litigation may be brought against parties as (i) it is often more difficult to prove allegations the longer the time has passed and (ii) even if the party has a solid case against a trustee, it is probably right that at some point in time, the trustee is allowed to move on notwithstanding the wrong he may have committed against the trust. The nature of the doctrine of laches was discussed by the House of Lords in Fisher v Brooker.64

The facts of the case concerned what the trial judge, Blackburne J, described as a song which verged on having acquired ‘cult status’.65 The claim in the action concerned the copyright to the song ‘AWhiter Shade of Pale’, a song which is renowned for its introductory organ solo. The song was sung by the group Procul Harum. The main body of the music was composed by Gary Brooker, but the famous eight-bar organ solo at the start, together with the organ melody underpinning the song, was added by another member of Procul Harum, Matthew Fisher.

Matthew Fisher did not, for a long time, force the issue about who owned the copyright in the song, which had made a considerable amount of money for Mr Brooker and their record label. During 2005, however, he wrote to Mr Fisher and the group’s music label, claiming a share of the copyright in the music and wanting a share of the royalties stretching back over six years before he made his claim. Mr Fisher recognised that he could not claim for royalties arising any further back in time due to the Limitation Act 1980. Blackburne J awarded Mr Fisher a 40 per cent share in the copyright of the music. Mr Brooker appealed to the Court of Appeal, which decided that his delay in pursuing his claim prevented him from being awarded a share in the musical copyright. It was against this decision, inter alia, that Mr Fisher appealed to the House of Lords.

The House of Lords allowed the claimant’s appeal and restored the declaration given by the trial judge awarding Mr Fisher a 40 per cent share in the music. In giving the main substantive opinion of the House, Lord Neuberger thought that ‘some sort of detrimental reliance is usually an essential ingredient of laches’.66 There was none on the facts suffered by Mr Brooker.

Lord Neuberger also pointed out that laches could only bar an equitable remedy, whilst here the claimant’s claim was based on a statutory claim: a declaration under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The doctrine of laches did not apply to the facts in the case, as the claimant was not claiming an equitable remedy. Lord Neuberger quoted67 the requirements set down by Lord Selborne LC in Lindsay Petroleum Co v Hurd for laches to apply. The court had to consider:

the length of the delay and the nature of the acts done during the interval, which might affect either party, and cause a balance of justice or injustice in taking the one course or the other, so far as relates to the remedy.68

Mr Brooker could not show any acts undertaken from when the song was written to 2005 which might have affected him adversely. Even if he could have shown such acts, Lord Neuberger was of the view that the benefit Mr Brooker obtained from Mr Fisher’s delay in bringing proceedings would outweigh any prejudice.

Fisher v Brooker therefore shows that the doctrine of laches is only applicable when an equitable remedy is being sought; it will not enable a defendant to allege delay for every claim a claimant makes. It might be used as a defence by a trustee charged with a breach of trust (as the remedy sought would normally be equitable compensation or a restoration of the trust property) but if it is to be used successfully, the trustee would normally have to show that he has suffered detrimental reliance on the beneficiary’s delay in bringing an action against him. The court must also be satisfied that the balance of justice requires the doctrine to be used.

Points to Review

You have seen:

![]() what a breach of trust is and that a trustee, if liable, is liable to restore the trust property to the trust or pay equitable compensation to the beneficiaries;

what a breach of trust is and that a trustee, if liable, is liable to restore the trust property to the trust or pay equitable compensation to the beneficiaries;

![]() that a trustee may rely on an exemption clause to limit or restrict his liability for breach of trust; and

that a trustee may rely on an exemption clause to limit or restrict his liability for breach of trust; and

![]() that a trustee may rely on a number of defences and other mitigating circumstances when charged with a breach of trust.

that a trustee may rely on a number of defences and other mitigating circumstances when charged with a breach of trust.

Making connections

This chapter has considered the remedies that may be taken against a trustee personally for breach of trust. The risk inherent with those remedies is that it may, for instance, not be worthwhile for a beneficiary to pursue them as they depend on the trustee being sufficiently solvent to remedy the breach of trust.

The beneficiary may, as an additional or alternative remedy, wish to take action to recover the trust property if it has been transferred into another party’s hands. Another option for the beneficiary might be to take action against any assistance that the trustee may have had in breaching the trust. These remedies are considered in Chapter 13.

Useful Things to Read

Useful Things to Read

The best reading is contained in the primary sources Listed beLow. It is aLways good to consider the decisions of the courts themseLves as this wiLL Lead to a deeper understanding of the issues invoLved. A few secondary sources are aLso Listed, which you may wish to read to gain additionaL insights into the areas considered in this chapter.

Primary sources

Armitage v Nurse [1998] Ch 241.

Chillingworth v Chambers [1896] 1 Ch 685.