When I was a first-level manager more than twenty years ago, I was asked to analyze an acquisition candidate that our company wanted to purchase. I felt confident that I had done a good job with my analysis, which I presented to my boss. Afterward, he called me in to his office to provide some feedback, telling me that I had done an excellent job and thanking me for my thorough work. “So what is the company going to do about this acquisition candidate?” I asked him.

My manager told me that the company was moving ahead with the acquisition. “It's a good candidate, and I think you agree,” he said. And then he told me the purchase price: $100 million.

I thanked my boss for giving me this additional information, but reminded him that my analysis had concluded that we should not pay more than $75 million for the company. Any amount above that number did not make sense to me. My boss responded that he appreciated my input, but that there were “extenuating factors.” We were going to pay $100 million.

Although I was tempted to walk away at that point, I felt that it was my responsibility to understand the company's rationale for paying more than $75 million. After all, as a publicly traded company, we needed to be good stewards for our shareholders. Further, overpaying for the acquisition would undermine the success of the deal. Paying a higher price could be justified only with more sales, an increased profit margin, a greater cash flow, or some combination of these. Absent those things, I could not justify in my mind paying the higher price.

“Harry, you have to understand,” my boss told me. “They have made up their minds. They are going to pay $100 million.”

This solidified in my mind the mythical “they,” the men and women everyone always talked about. They (aka “those guys”) had decided; they were moving ahead ... Who were “those guys”? In this instance, those guys included division presidents and senior people far above me, including the CEO.

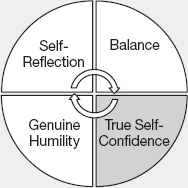

When I thought back on my analysis, I was confident that I had derived an appropriate valuation. I had also spoken with others in order to gain balance and perspective as I made my evaluation. Finally, having reflected on the situation, I felt sure that my ego was not driving me to push my viewpoint. I truly believed that my analysis indicated the right thing to do. So I told my boss, “I am going to speak to the CEO about this.”

My boss told me that he didn't think this was such a good idea. After all, senior management agreed to do the deal. But my mind was made up: I had to tell the CEO what I thought about the decision. I knew that the worse-case scenario was that I would be fired for speaking my mind. Obviously this was not the outcome I wanted. Nor was I looking to swoop in and gain the credit for saving the company from making a move that was too costly. I had been asked to do a job, and I was determined to see it through to the best of my ability so that the results of the analysis were understood by “those guys” with the power to decide. I was also incredibly curious about why they had made this decision. Once it was clear in my mind that, no matter what, I needed to tell others what I thought was important for them to know, it was surprisingly easy to move forward, even though doing so meant I was jumping a half-dozen levels to speak with the CEO.

My decision to escalate the issue to a higher level was not driven by a desire to show the bosses a thing or two. Rather, it was a result of having true self-confidence, which allowed me to draw on my strengths and abilities to influence others. With true self-confidence I knew that speaking to the CEO about the acquisition candidate was not only appropriate but also the right thing to do.

TRUE SELF-CONFIDENCE

TRUE SELF-CONFIDENCE