3.1 Introduction to Requirement Patterns 19

3.2 The Anatomy of a Requirement Pattern 21

3.3 Domains 29

3.4 Requirement Pattern Groups 31

3.5 Relationships Between Requirement Patterns 32

In all but trivial systems you'll have requirements that are similar in nature to one another or that crop up in most systems—and probably lots of them. For example, you might have a number of inquiry functions, each with its own requirement. When specifying a business system, a significant proportion of the requirements fall into a relatively small number of types. It's worthwhile to make an effort to specify all the requirements of one type in a consistent manner. To do this, we introduce the notion of a requirement pattern, to allow us to describe how each requirement that uses it should be defined.

Requirement pattern: an approach to specifying a particular type of requirement.

A requirement pattern is applied at the level of an individual requirement, to guide the specifying of a single requirement at a time. For example, if you have a requirement for a certain report, you can engage the report requirement pattern to help you specify it. Once you've written the requirement (and any extra requirements it suggests), the pattern's job is done, and you can put it away and move on. But when a software designer or developer comes to decide how to implement the requirement, the pattern is available to give them some hints relevant to their job, if they wish. A tester can similarly use the pattern for ideas on how to test it.

What are the benefits of using requirement patterns? First, they provide guidance: suggesting the information to include, giving advice, warning of common pitfalls, and suggesting other matters you ought to consider. Second, they save time: you don't have to write each requirement from scratch, because the pattern gives you a suitable starting point, a foundation to build on. Third, patterns promote consistency across requirements of the same type. Of these, guidance is of the greatest value. Saving specification time and increasing consistency are nice, but sound guidance that leads to much better requirements can avoid immense trouble and work later on.

The guidance provided by a requirement pattern usually goes deeper than just "say this…." It can give background insight into the problem at hand. It can raise questions you ought to ask yourself. In some cases it can lead you to write a requirement (or several) very different from the one you first envisaged. Answering a big question often raises a number of smaller questions. A requirement pattern is a response to a big question and aims to give both the big answer and the smaller questions.

Some requirement patterns either demand or invite the specification of extra requirements: both follow-on requirements that expand on the original requirement, and systemwide pervasive requirements to support the pattern itself (for instance, for an underlying feature needed by all requirements of this type). It is therefore useful to be aware of which patterns you have used (perhaps by keeping a simple list), so you can run through them asking yourself whether each one needs its own extra supporting requirements and whether you have defined them. This topic is explained in more detail in the Extra Requirements section later in this chapter.

Patterns can vary in their level of detail (their preciseness) and their value. Some types of requirements can be defined in great detail, and instances of them vary little. Others have something worthwhile in common but vary to such an extent that we can't prescribe what they ought to say. These variations are natural. To justify itself, a pattern simply needs to be of value; it doesn't have to do everything a pattern could possibly do. On the other hand, just because we encounter a particular type of requirement repeatedly does not mean a pattern for it would automatically have value. If it's hard to encapsulate what the requirements have in common, it's hard to provide guidance on how to specify requirements of this type.

Where do requirement patterns come from? This book defines patterns for a range of common types of requirements, which can be used as they stand. Other patterns may become publicly available in due course. Or you can write your own—see the "Writing New Requirement Patterns" section in Chapter 4 for guidance. You can also modify existing patterns to suit your own preferences and circumstances.

This section describes what a requirement pattern contains, how it is organized, and why. Bear in mind that it talks about patterns and how to write them, not the requirements that might result from a pattern. A requirement pattern is considerably more substantial than a requirement. Writing a requirement pattern is correspondingly a lot more involved, too. Indeed, writing a requirement pattern deserves much thought. To be useful as a guide to writing requirements, it needs to take into account all the situations and variations that are likely to be encountered in the type of requirement for which it's written.

A requirement pattern needs to say when to use the pattern and how to write requirements based on it. It can also give hints on how to implement and how to test requirements of this type. To convey these sorts of information, each requirement pattern contains the following sections:

Basic details The pattern manifestation, owning domain, related patterns (if any), anticipated frequency of use, pattern classifications, and pattern author.

Applicability In what situations can the pattern be applied? And when can it not be applied?

Discussion How do we write a requirement of this type? What does a requirement of this type need to consider?

Content What must a requirement of this type say? What extra things might it say? This is the main substance of the pattern.

Template(s) A starting point for writing a requirement of this type—or more than one if there are distinct alternative ways.

Example(s) One or more representative requirement written using this pattern.

Extra requirements What sorts of requirements often follow on from a requirement of this type? And what pervasive systemwide requirements might define something for all requirements of this type?

Considerations for development Hints for software designers and engineers on how to implement a requirement of this type.

Considerations for testing What do we need to bear in mind when deciding how to test this type of requirement?

Preceding all of this we have the pattern name, which appears in the title of the whole pattern. Each requirement pattern needs a unique name so that it can be referred to unambiguously. A pattern name should be meaningful—to clearly capture the nature of the pattern. A pattern's name should also be as concise as possible—preferably a single word, but not more than three. It's also recommended that each pattern name be a noun-phrase. The name of a pattern for functional requirements reflects the function name (for example, "inquiry" for the pattern that guides how to specify an inquiry function).

The number of sections in each pattern has been deliberately kept to a minimum to make them as easy to read and to follow as possible.

The Basic Details section of a requirement pattern is simply a convenient vehicle for all those items that can be answered briefly (rather than clogging up our patterns with lots of tiny subsections). In fact, the items lumped together here are a mixed bag. The items indicated by an asterisk (*) are omitted from all the patterns in this book, either because they are obvious from the context (the chapter they're in) or because they're the same in every case.

There can be more than one manifestation of a particular requirement pattern, which means different variants or versions. This item tells us which manifestation we have before us, to distinguish it from others. The first manifestation of a pattern is referred to as the "Standard" one. The manifestation can convey one or more of the following things: (See the Requirement Patterns and Diversity of Approaches section later in this chapter and "Tailoring Requirement Patterns" in Chapter 4 for more.) "Pattern manifestation" is omitted from all the patterns in this book. All should be regarded as being "Standard." | |

Belongs to domain*: | Every requirement pattern belongs in a domain, and this states which one. Many requirements for which patterns are used need some sort of supporting infrastructure. For example, requirements for reports imply the existence of an underlying reporting infrastructure for producing those reports. Requirements should be defined for the infrastructure itself. (See the next section, Domains and Infrastructures, for more information.) One purpose of identifying whether a particular pattern implies the presence of supporting software is to prompt you to consider whether the requirements for that software have been adequately specified. "Belongs to domain" is omitted from all the patterns in this book because it is clear from the chapter in which the pattern resides. This item becomes essential if the domain cannot be determined from its context, such as a single pattern that resides in a stand-alone document. |

This lists any other requirement patterns that apply to related situations. If it would be helpful, this item can also say a little about how the patterns relate to each other. | |

Anticipated frequency: | How many times is this pattern likely to be used in a typical requirements specification? For rarely used patterns, this is best stated as an absolute number, or an absolute number for each occurrence of a parent requirement. For more commonly used patterns, expressing it as a percentage of the requirements is more useful and easier. Often the frequency is best expressed as a range (of absolute numbers or percentages). This item is also at liberty to point out circumstances in which the frequency might fall outside the normal range. For most patterns, this value is indicative only; it might vary considerably from one system to another. Don't lose sleep if your number of requirements falls outside the suggested range. The frequencies stated for the requirement patterns in this book derive from a diverse set of real-world requirements specifications. Sometimes the actual numbers encountered have been adjusted to create a broader range, to bear in mind factors not present in the specifications studied. |

Each requirement pattern can be classified in multiple ways, and this item lists all that apply to the main type of requirement covered by the pattern. No attempt is made to apply these classifications to any of the extra requirements described in the pattern. See the "Requirement Pattern Classifications" section later in this chapter for more information about how to use classifications. Classification lists are given in a standard format of "Name: Value", separated by semicolons. For example: Functional: Yes; Performance: Yes This format is concise, readable, and easy to follow. It allows new classifications to be added without changing the standard structure of requirement patterns. | |

Knowing who wrote a pattern can help you decide whether you want to use it. For patterns written in-house, it tells you who to go to for help. For manifestations other than the first, this identifies both the original author and who tailored it. The pattern author is omitted from all the requirement patterns in this book but should be included in all patterns whose authorship isn't obvious. |

The Applicability section describes the situations in which the requirement pattern can be applied. It should be clear and precise. Conciseness helps too, to let the reader form as quickly as possible a picture of when to use this pattern. It's advisable for the first sentence to capture the essence of the matter, and for the rest to clarify and expand it—just like a requirement, in fact. All such statements in this book begin with, "Use the «Pattern name» to…."

Normally, a requirement pattern is applicable in only one clear situation: two different situations usually demand two different patterns. That's not to say that all the requirements that use a pattern will look the same—far from it, because there may be considerable variations between them. Some might have optional extra clauses, and they might vary greatly in their size and complexity. However, they will all share the same underlying nature.

The "Applicability" section can also state situations in which the pattern should not be used, if there's any danger of the pattern being misapplied. If there are no situations of this kind, this statement is omitted. All such statements in this book begin with, "Do not use the «Pattern name» to…."

The Discussion section of a requirement pattern tells you how to write a requirement of this type. It explains everything it can that's likely to help someone who wants to specify a requirement of this type. It generally opens with an overview, to set the scene. It can describe a process to follow, if figuring what to write in such a requirement isn't straightforward. It can raise topics to which to give special thought. It can mention potential pitfalls. The quantity of this discussion material can vary enormously from one requirement pattern to another: from one paragraph to many pages; it all depends on the nature of the requirement and what there can usefully be said about it.

The Content section is a detailed list of each item of information that a requirement of this type must convey. Each content item begins with a name by which to refer to the item, followed by an indication of whether it's optional, and then general descriptive material. It is presented like this:

Item 1 name Item 1 description.

Item 2 name (optional) Item 2 description.

…

It's useful for the description to justify the item, to explain its purpose if it's not obvious: if the writer of a requirement understands why it's needed, they are more likely to write it (and to write it well). The description can also suggest what to say about the item in the requirement, offer advice, and generally say anything that might help. The order in which the elements of the content are described is implicitly the best order for them to appear in a requirement.

The aim of a requirement template is to allow you to copy it into a requirement description to use as a starting point. A template is a fill-in-the-blanks definition for a requirement that is deemed to be typical of the type.

The Content section of a pattern can describe various optional topics a requirement might need to address but that aren't relevant in all requirements. When deciding which of these topics to include in a template, our guide is efficiency: to minimize the effort in using the template. If a topic is likely to be needed in only a small percentage of requirements, it's best left out of the template. But we must bear in mind that it's much easier to delete an unwanted item than to type in an item for which we have no starting point. A useful rule of thumb is to include a starting point for a topic in the template if at least 20 percent of requirements are likely to possess it.

Be warned that templates for documents or parts of documents are dangerous, because they can lull you into avoiding the thinking you really need to do, or they give you the impression that all the thinking has already been done. Another pitfall is that you end up saying what the template writer felt should be said when they had a different situation in mind. Nevertheless, if taken with a suitably large pinch of salt, using a template can save a little time when writing a requirement.

Each template is shown within a table like the one below, which is in a form suitable for direct copying into a requirement:

Summary | Definition |

|---|---|

The format of the summary | The format of the definition |

Additional explanatory notes can follow the table.

Here's an example of a template, from the inquiry requirement pattern, that demonstrates the main aspects:

Summary | Definition |

|---|---|

«Inquiry name» inquiry | There shall be an [«Inquiry name»] inquiry that shows «Information to show». Its purpose is «Business intent». For each «Entity name», the inquiry shall show the following:

|

Both the summary and the definition can contain placeholders for variable information, which are indicated by being enclosed in double-angled brackets and in italics—for example, «Entity name» or «Description». Each placeholder must have the same name as that used in the list of content items in the Content section (or sufficiently similar that they can be readily matched up). The summary format typically comprises two parts:

A fixed word or brief phrase related to the name of the pattern.

A brief description to distinguish this requirement from all others of this type.

A template can contain optional parts: items of information that are not needed in all cases. This is indicated by surrounding each option part in square brackets: [like this]. This is indicative only; it doesn't mean that everything not in square brackets is always essential. Conversely, an optional item might be essential in a particular situation for which you're writing a requirement.

When a requirement can contain a list of items, a sequence number is added to the name of each one (as with '«Information item 1»' in the example above), to allow the template to show more than one. An ellipsis (…) indicates that the list continues and might contain as many items as are needed.

A requirement pattern can contain several alternative templates, each tailored to a particular situation. For example, there might be one for a simple case, one containing every possible item, and one or more in between.

Each requirement pattern contains at least one—usually more—example requirement definitions that demonstrate use of the pattern in practice. For instance, a typical requirement that uses the pattern may be very simple, but some might need to say more; in such a case, we might give examples of each.

Each example is shown within a box like the one below, containing information exactly as they would appear in real requirements of which they are representative:

Summary | Definition |

|---|---|

Summary for the example | The definition of the example |

Anything that follows the box (like this) is explanatory material that is not part of the example requirement itself. There ought to be no need for notes to make clear the meaning of any requirement, because requirements should be self-explanatory, but notes can be used to point out an aspect of a requirement that renders it a useful example.

Example requirements need not be consistent with one another. Each one is present to demonstrate a representative situation. Spanning a range of possibilities often demands requirements from different sorts of system and sometimes requirements that conflict with one another. All examples are intended to be good examples; there are no examples of what not to do. Examples are also intended to be realistic, which means not simplified when being added to a requirement pattern. Sometimes this involves the inclusion of extra clauses that might make an example look a little long-winded; this is preferable to giving an example that says less than one would want in practice.

Some requirement patterns contain real-world examples that can be copied directly into requirements specifications and then modified as you see fit. For example, the comply-with-standard requirement pattern has examples for a range of frequently used, general-purpose standards. A list of examples, then, can serve as a body of knowledge to be tapped at will and not just as representatives that show you what such requirements might look like.

In many situations, one requirement isn't sufficient to say all that must be said: you might (or, in some cases, always) need to specify additional requirements to spell out the implications properly. The Extra Requirements section in a requirement pattern explains what sorts of extra requirements should be considered and in what circumstances. It provides guidance on what to do beyond simply specifying the main requirement. What other things should you think about? What more needs to be said? If there's nothing further to specify, a requirement pattern's Extra Requirements section can be empty.

For example, a requirement that mandates compliance with a particular standard (see the comply-with-standard requirement pattern) is rarely sufficient. Just what does that standard say? Which parts are relevant to our system? What must our system do to satisfy this standard? We need detailed requirements that reflect the answers to these questions. The Extra Requirements section of the comply-with-standard pattern is the place that points out what further work needs to be done.

There are two types of extra requirements:

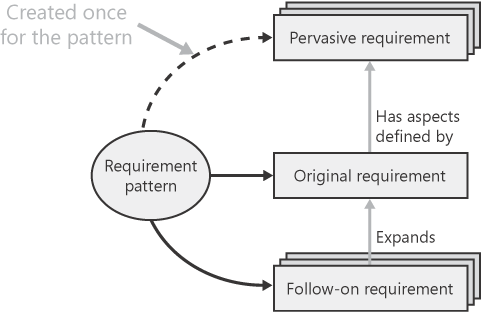

Type 1: Follow-on requirements These come after the original requirement and define additional things about it. They expand the original requirement. For ease of reading, follow-on requirements should come immediately after the original requirement.

Type 2: Pervasive requirements These are defined once for the whole system and define things that apply implicitly to all requirements of this type. Usually there is only one pervasive requirement for a particular aspect (for example, "Every page on every report shall show the company logo"), but sometimes there are more, with each applying in clearly defined circumstances (for example, "Every page on every report to an agent shall show the agent's company logo," in addition to the previous example). The use of pervasive requirements of this sort means that each original requirement has fewer topics to cover and can be simpler. They save repetition, and as a result they avoid the chance of inconsistency in their areas.

Pervasive requirements can also be "catch-alls" that define implicit functions for all instances of this pattern. For example, "All data shall be displayable on some inquiry or another."

An extra requirement could itself be written with the assistance of a requirement pattern. It can have extra requirements of its own.

Figure 3-1 shows how use of a pattern can result in an original requirement plus two sets of extra requirements: follow-on requirements that add details about the original requirement, and pervasive requirements that define common aspects shared by all original requirements of this type.

You should group related pervasive requirements together, either before all the original requirements to which they relate or after them all. The pervasive requirements for a requirement pattern might look as though they belong in the specification for an infrastructure supporting the domain in which the pattern lives, but actually they should be kept separate. The infrastructure's requirements define what the infrastructure can do; the pervasive requirements define what our system needs (because another system might use that same infrastructure differently). That's fine, although if both systems use the same instance of software that implements the infrastructure, it can impose extra functional demands on that software. In such cases, you can place the pervasive requirements in a separate "common" requirements specification that both systems refer to.

Take care to alert all readers to the presence of pervasive requirements—especially developers, because pervasive requirements often have profound design and development implications. Imagine how you'd feel upon discovering that some characteristic you demanded for every user function was possessed by none of them. So,

Don't rely on readers reading the whole requirements specification. A developer might read only those parts that look relevant to them, plus the introduction.

Don't bury important pervasive requirements where they might be missed (such as at the end of the requirements specification).

Make references to relevant pervasive requirements from elsewhere as you see fit.

Explain in the requirements specification's introduction the significance of pervasive requirements and the importance of not missing them.

Consider putting all the pervasive requirements in one place and pointing all developers unequivocally to it.

Consider highlighting each pervasive requirement in some way, such as a clear statement at the end of the requirement's definition. For example, "This is a pervasive requirement" or "This requirement applies across the whole system" or "This requirement applies to all user functions in the system".

An Extra Requirements section can contain its own example requirements to demonstrate what each kind of extra requirement might look like. If so, follow-on and pervasive requirements should be kept separate and clearly labeled so that they won't get mixed up. Example pervasive requirements are often suitable for direct copying into a requirements specification. In rare cases, the number of pervasive requirements in a pattern could run to a dozen or more.

In extreme cases, the follow-on requirements resulting from a single original requirement could involve more work than all the other requirements put together. For example, complying with a demanding standard (for, say, safety) might be a massive undertaking and much harder than building a simple system that has the functionality you need.

The Considerations for Development section is intended to assist a developer who needs to design and implement software to satisfy a requirement of this type. It gives them hints and suggestions and points out things not to forget. The Considerations for Development section should be written in the language of developers.

The best way to look at this section is as the sort of guidance a very experienced developer would give to a junior developer. If a grizzled, seen-it-all engineer were asking a wet-behind-the-ears graduate to implement a requirement of this type and giving them advice on how to tackle it, what would they say? The amount to be said varies greatly from one requirement pattern to another. In some cases, the requirement is self-explanatory; in others, there are various pitfalls to point out.

This section can also point out things that a development representative could look out for when reviewing requirements. Is a requirement being unreasonable? If it's likely to be impractical to implement, press to have the requirement changed.

A requirement pattern is a useful place to explain how to test requirements of its type. This section is aimed at testers. It is written primarily with user acceptance testing in mind, because that's the sort of testing that can be done most closely against the requirements. But it can be used for other sorts of testing, too.

Since requirements vary considerably in their nature, they vary as much in the ways they need to be tested. Each "Considerations for Testing" section aims to convey three sorts of information:

Points to look out for when reviewing a requirement of this type. If a requirement is likely to be difficult to test, suggest how it can be reframed to make testing easier.

Overall guidance on how to approach the testing of this type of requirement.

Notes on matters to bear in mind and (where possible) tips on how to deal with them.

Universal requirement patterns can discuss testing only in general terms—because a pattern knows nothing about a particular organization's testing practices, the testing tools it uses, the nature of the environment in which the system will run, or the nature of the system.

An organization may well find it worthwhile to tailor—or rewrite—the "Considerations for Testing" sections in its patterns to suit the ways it does testing (taking into account, in particular, whatever tools it uses for testing) and the expertise and culture of those responsible for testing. Indeed, by taking into account the organization's individual situation, it's possible to write sections that are far more than considerations for testing; they can become instructions on how to test requirements of the requisite type. If you aim to do this, you may find it more useful to leave the Considerations for Testing section alone and add (or replace it with) your own "Testing Instructions" section. This could be augmented by additional artifacts to use when testing this type of requirement, such as tailored forms for writing test cases.

There is much to be gained by organizing our requirement patterns rather than presenting a monolithic list of them. We do this by assigning every requirement pattern to a domain. Each domain has a theme, which all its patterns share, but the nature of the theme can vary greatly from one domain to another. The domains used in this book—each with its own chapter in Part II—are Fundamental, for things that any kind of system might need; Information, for several aspects of the storage and manipulation of information (data); Data entity, on how to treat specific kinds of data; User function, for a couple of common types of functions, plus accessibility; Performance; Flexibility; Access control; and Commercial, for business-oriented matters. This shouldn't be regarded as a definitive list: new domains might be needed if further requirement patterns are written. For example, if requirement patterns were to be written for a particular industry, they would deserve their own domain (or possibly more than one). The applicability of a domain can range from very broad to very narrow: from nearly all systems, through systems in one industry, to just a couple of systems in a single company.

When you begin specifying a system, you can look through all the requirement pattern domains (in this book, plus any extras you have from elsewhere) and decide which ones are relevant to your system. If it's a noncommercial system, you might decide to drop the Commercial domain. The set of requirement patterns that are available for use in your system depends on the domains you decide are relevant. Regard only the patterns in your chosen domains as available. Conversely, if you want to use some other pattern, it can force you to add a domain you hadn't previously recognized, which can alert you to extra topics you need to address (such as an infrastructure it depends upon). Identifying the available patterns is more useful if you have patterns in specialized domains; the patterns in this book are too general for drawing up a list of relevant domains to make much of a difference.

Each domain needs an introduction to explain its theme. It can then describe features that are common to all its patterns. The size of an introduction could be anywhere from one short paragraph to many pages; it depends solely on how much there is to say. The domain also needs to describe any infrastructure(s) its patterns depend upon (or, more properly, the requirements produced by these patterns), as discussed in the next section.

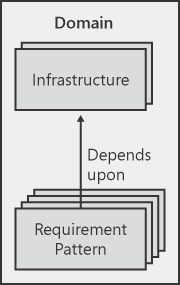

Some types of requirements depend upon infrastructures, as discussed in the Infrastructures section of Chapter 2. A requirement pattern gives us the opportunity to identify any infrastructure(s) its type of requirement depends upon, which saves having to figure them out for individual requirements. We can go further and discuss each infrastructure—things to bear in mind when you specify requirements for the infrastructures your system needs. It's not possible to go into detail or specify actual requirements because they will vary considerably according to the demands of each organization and each system. They're called infrastructure overviews to make this clear.

Rather than expect that each requirement pattern describes any infrastructure it needs, we pass the burden of explanation up to the domain the pattern belongs to. This is because each infrastructure tends to be needed by more than one pattern in the domain. To avoid repetition, each type of infrastructure is described in only one domain. Each chapter of patterns in this book contains a subsection for each infrastructure in its domain. This book discusses three infrastructures: information storage (in Chapter 7 user interface, and reporting (both in Chapter 8). The key concepts relate to each other as shown in Figure 3-2.

A requirement pattern is free to use infrastructures in other domains. It's always good practice to avoid mutual dependencies, so if anything in one domain depends on another domain, nothing in the latter domain should depend on the former—that is, if you can avoid it. An infrastructure can also depend upon another infrastructure.

What should such an infrastructure overview say? Its role is to give guidance and advice to someone who's going to specify requirements for an infrastructure of this kind for a particular system, to suggest topics for requirements to cover. At a minimum, it should state what a calling system expects from the infrastructure: what it's there for, and its main functions. For problems for which there are obvious alternative solutions, the overview should avoid making judgments.

Each infrastructure overview is divided into the following subsections:

Purpose An explanation of why the infrastructure exists, the role it plays.

Invocation requirements Suggestions for sorts of requirements that define how a system will interact with the infrastructure—for those functions that the infrastructure must make available to a system—plus any other capabilities systems might want from it (such as access control). The needed functions can be regarded collectively as the interface (or interfaces) the infrastructure needs to make available to callers.

Implementation requirements Some ideas on the other features the infrastructure needs in order to stand on its own feet (for example, inquiry, maintenance and configuration functions). These are brief and merely hint at the likely main areas of functionality to think about when defining the infrastructure itself.

For example, for a reporting infrastructure, our invocation requirements might be very simple: just a function that lets our system request the running of a chosen report. The implementation requirements, on the other hand, would be far more extensive, addressing the complexities of various ways of delivering a report to a user, other ways of requesting reports, designing reports, and so on. (These topics are discussed further in the "Reporting Infrastructure" section in Chapter 8.) To take the analogy of building a house, one of the infrastructures we'd want is an electricity supply. In this case, the invocation requirements would cover how many sockets we want in each room, and the implementation requirements would deal with the parts you can't see, such as the connection to the power grid and adherence to building quality regulations.

When several requirement patterns have features in common, we can create a requirement pattern group and use it as a place to describe all of their common aspects, to save repeating them in each individual pattern. A requirement pattern group is not a requirement pattern: you can't create requirements of this type. But the definition of a group can contain any of the following sections that appear in the definition of a requirement pattern: Extra Requirements Considerations for Development and Considerations for Testing. The rule is to include whichever of these sections in which something valuable can be said and to omit the rest. Whenever one of these sections is present in the group, it's worth including a note in the equivalent section in each pattern based on the group as a reminder to refer to it.

The difference between a domain and a requirement pattern group is that the patterns in a domain share a common theme, whereas those in a group have detailed features in common. The patterns in a group don't need to belong to the same domain. (For those familiar with Java programming, the relationship between requirement patterns and domains is akin to that between classes and packages: every class belongs to a package just as each pattern belongs to a domain. Also, a requirement pattern can build upon a pattern belonging to a different domain, just as a Java class can extend a class in a different package.)

When you use a requirement pattern, it generally says everything you need to know to create a requirement of that type. But a pattern might refer to other patterns for several reasons. Two fundamental types of relationship between requirement patterns exist:

Refers to A requirement pattern can mention another pattern somewhere in its definition. There are several reasons why a requirement pattern might refer to another:

A requirement defines something that contains (has) something else defined by another requirement.

A requirement that's an instance of one pattern uses information defined in requirements that are instances of a second pattern. For example, a requirement that defines a data structure might use a value of a kind defined by a data type requirement.

A requirement might suggest the creation of an extra requirement of a type for which a pattern is available.

A divertive pattern might persuade you to create a requirement using a different pattern. (See the "Divertive Requirement Patterns" section later in this chapter.)

A requirement pattern could refer to another pattern that contains relevant discursive information on a particular topic.

Extends A requirement pattern builds upon (or is a specialization of) another pattern. In object-oriented terms, this is an inheritance relationship. Instead of extending another pattern, a requirement pattern can build upon (extend) a requirement pattern group. (In object-oriented terms, the group acts like an abstract base class for the pattern.) A requirement pattern is not allowed to extend more than one pattern or group.

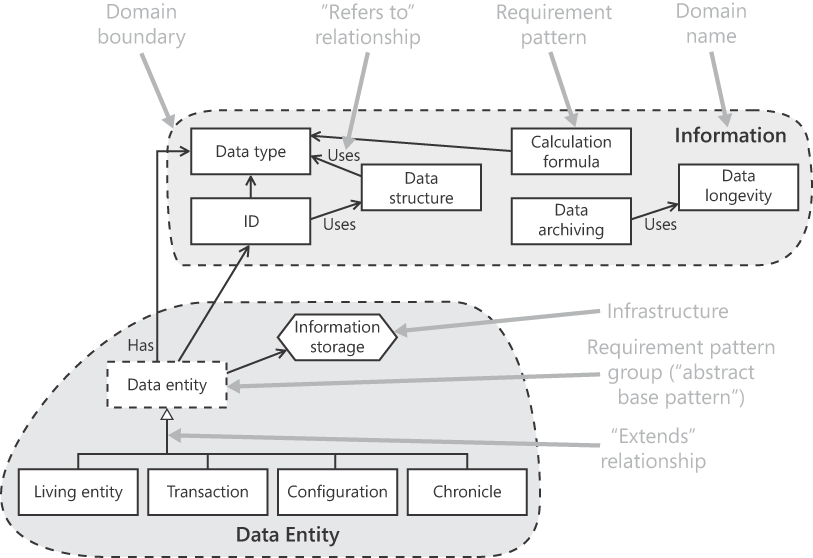

We can draw a collection of patterns and infrastructures and the relationships between them in a diagram. Figure 3-3 is an example that shows two domains, with elements of the notation annotated. Inheritance is the most important type of relationship. For simplicity, every other type of relationship is shown as "Refers to," though its role can be indicated by a label on the link. When showing several domains on one diagram, it can become impractical to show all the relationships. In such a case, show all relationships within each domain and all extends relationships, but omit refers to relationships between domains as you see fit. For readers familiar with object-oriented concepts (or UML), this is akin to a class diagram showing relationships between classes.

In Figure 3-3, "Data entity" is not a pattern. It's a requirement pattern group: a place for describing the common features of the four patterns that build on it. Any descriptive information that applies to all patterns in a group should be given for the group, rather than repeated for each pattern. Also, by convention, labels for relationships between requirement patterns are placed nearer the subject of the relationship, rather than the object. So, it is a Data entity that has an ID (rather than vice versa). The hexagonal shape of "Information storage" denotes it as an infrastructure.

See the beginning of Part II of this book for a diagram of this sort for all the requirement patterns in this book. Each of the eight domain chapters contains a diagram of this sort in its introduction, with annotations giving a brief explanation of each pattern, pattern group, and infrastructure.

Requirements can be classified in various ways (for example, by dividing them into functional and nonfunctional ones). Using requirement patterns has the advantage that if we classify the patterns, we automatically classify the requirements that use those patterns. Classifications tell us a little about the nature of the requirements that result from using each requirement pattern.

Other ways of using these classifications include finding requirements according to their classification and producing statistics. People like statistics (some people, at least, and they tend to be senior executives it's worth our while keeping happy). Statistics on the requirements for a system can be useful in a variety of ways. They can give a rough picture of the scale and complexity of the system. To do this, we need to tag each requirement with whatever values are needed for all the sorts of statistics we want. (Requirements management tools typically do this by letting you define extra requirement "attributes." Then you enter the value of each attribute for each requirement. It's a tedious business.) Using requirement patterns can save some of this effort, because all requirements created using a pattern have attributes in common. They need be defined only once, when the pattern is written. This information is recorded in the "Pattern classifications" section of each pattern.

Once requirements are tagged in this way, it's also possible to search on the classifications to find all the requirements that match your criteria. How you transport this classification information from the patterns to your requirements depends on how you store the requirements. (This is left as an exercise for the reader!) A straightforward way is to copy the requirements into a spreadsheet, add a column identifying the requirement pattern used by each requirement (if any), and add a column for each classification. (Sorting on the pattern name makes it easier to apply classification values many at a time.)

The requirement patterns in this book contain classifications according to a small number of basic classification schemes that are defined below. You can define extra classification schemes of your own and classify patterns according to them. If you do, write proper definitions in a similar manner to those below, and make them available in the same place as the requirement patterns that refer to them.

Classifications can be defined that assist anyone who uses requirements, including developers. As a result, it's not necessary for everyone to understand every classification. For this reason, each classification has its primary audience explicitly stated. If you're not part of this audience, don't worry if you can't follow what it's for or if you're not interested in it.

Requirement pattern classifications need to be properly and precisely defined, or else any statistics based on them can't be regarded as reliable. Each classification needs the following defined for it:

Name: | A self-explanatory, unique name for the classification. |

Audience: | An explanation of who is likely to be most interested in this classification: who it's aimed at. |

Purpose: | A description of what the classification is intended to be used for. |

Allowed values: | A definition of the values that a pattern may have for this classification, and explanations of their meanings. The most common way is to define a list of individual values. Numeric or alphabetic or other kinds of values may be used, provided it's clear to the reader what each value means. |

Default value: | This is the value assumed for this classification if it's not present (explicitly stated) in a pattern. This saves cluttering patterns with explicit mentions of classifications that are meaningful for relatively few patterns (that is, the few that have a significant value for it). |

There are three requirement pattern classifications used in this book, which we now describe using this format.

It is good practice to keep the size of each requirement's definition within moderate bounds; one that runs to ten paragraphs is way too long. A requirement pattern may identify several pieces of information, although a typical requirement of its type might possess only one or two. From time to time you might have a requirement that possesses more and, as a result, is unreasonably large. In this situation, it makes sense to split the requirement into two or more requirements.

The way to do this is to retain the initial requirement but to cut out parts and make them into additional requirements, which are refinements of the main requirement. Each refinement requirement should specify one extra aspect. And each refinement should identify the requirement it builds on. For readability, the main requirement should be immediately followed in the specification by its refinements. This practice makes sense whether or not you're using a requirement pattern—but when you are, you can regard the pattern as applying to both the main requirement and the refinements. If a requirement pattern suggests that several pieces of information be present, this is satisfied if all are present in one of the requirements or another. A second reason for splitting a requirement is if different parts of it have different priorities.

Depending on the nature of the system you're specifying, up to a quarter of all requirements could be refinements of other requirements. If you use a very fine level of requirements granularity, you'll increase the number of requirements and with it the percentage of requirements that are refinements.

Usually when you apply a requirement pattern, the result is a requirement that matches what you asked for. However, a pattern could be sneakier than this: it could try to lead you away from the obvious and towards an alternative, better way of formulating what you want. It explains the difficulties that the obvious way causes (usually for developers), and it provides advice on how to avoid these problems by using requirements that are stated in different terms but that aim to achieve the same underlying aim. A divertive requirement pattern can either explain the alternative itself or it can divert you to a different requirement pattern entirely—or both.

Requirement patterns can be much more valuable than just saying, "If you want to require X, this is what to write…." They can be like having an expert sitting at your shoulder saying, "Hang on! If you specify it like that, you're asking for trouble. Let me explain. Why don't you try this instead?" Several of the performance patterns are divertive, because the most obvious ways to specify performance are often a nightmare to satisfy. (For example, "The system shall be available 24×7" gives developers little idea of what they must do to achieve it.)

There's no single right or best way of formulating or expressing requirements. For a given system, there's no single perfect set of requirements to define it. Different requirements approaches might break down a problem in different ways, resulting in requirements that vary in their level of granularity and the way they're expressed. The term "requirements approach" as used in this section simply means a way of going about the specifying of requirements in general or certain types of requirements in particular. Each approach could have its own set of requirement patterns. They might simply be the approach's own distinct manifestations of recognized standard patterns, or they might be patterns specific to the approach.

We can accommodate a diversity of requirements approaches—to let the proponents of each approach create whatever requirement patterns they wish, including their own manifestations of existing patterns. And by recognizing different approaches explicitly, we make the available choices clearer to analysts.

Nevertheless, the greater agreement there is on standard patterns (and the fewer different manifestations of patterns), the better. It's perhaps a testament to the excellence of the choices for design patterns made by Gamma et al. that there's been no apparent call for variants (although lots of extras have appeared), and thus accommodating diverse sets hasn't been necessary. In allowing for multiple requirements approaches, I'm heading off potential criticism of the requirement patterns given here. I can cite it as proof that there's no single "right" set of requirement patterns. If anyone doesn't like them, they can devise their own alternatives without demanding to replace the ones here. There's room for many schools of thought.

To avoid potential confusion, don't mix material for multiple requirements approaches in the same requirement pattern. It is clearer to have multiple manifestations of the pattern and to pick only one to use on your system.

When creating a new pattern (or manifestation of an existing pattern) for a particular requirements approach, state the approach it relates to in the "Manifestation" section of the pattern. Note that when a manifestation is created for a different approach, it takes on a life of its own and might go through a succession of versions independent of the manifestation for the original "standard" approach.

Where two sets of requirement patterns exist that cover the same ground, there are two ways they can be organized:

One domain specification can contain both sets of requirement patterns. (A "domain specification" is a document, or part of a document, that contains its requirement patterns and a section about each of its infrastructures. Each of the eight domain chapters that follows is a domain specification.)

There can be two manifestations of the domain specification, each containing one set of the requirement patterns.

The second way is easier and less confusing to use (and thus less liable to have an analyst apply the wrong manifestation of a pattern). The second way also allows each manifestation of the infrastructure specification to be tailored to the methodology its patterns use, which is useful if the infrastructure's own requirements use these patterns (which they might).

It is perfectly possible to write use cases for some requirement patterns, those that result in requirements that demand the presence of a well-defined function (or, indeed, more than one function). For example, for the inquiry requirement pattern we could write a use case that shows the steps in a typical inquiry. Use cases for requirement patterns are always generalizations, an official UML concept that means they are written to apply in any circumstance that fits, using an "is-a-kind-of" relationship.

One requirement pattern might demand the presence of more than one function for each of the resulting requirement. For example, the configuration requirement pattern implies the presence of create, read (inquire), update, and delete functions (commonly called CRUD) for each item of configuration data. We can write a use case for each of these functions, and four use cases will suffice for all configuration, rather than attempting to write four for each type of configuration (or, more likely, writing use cases for a few but not the rest).

It makes sense to write requirement pattern use cases to suit your particular environment. To attempt to write universally applicable use cases risks them being so high-level as to be of no practical value. For example, a universal "create configuration data" use case has little to say—perhaps just an actor entering the data and the system storing it in a data store. But if we have a browser-based user interface with remote users and a Web server that is outside our system's scope, the use cases will look very different. Also, the use cases' preconditions might insist the actor be logged in and authorized to access this type of configuration data—to satisfy particular security requirements. (All this illustrates how hard it is to write detailed use cases without bringing in elements of the solution, even though use cases are meant to reflect only the problem to be solved.) No use cases have been written for the requirement patterns in this book.

A business rule is a definition of one aspect of how a business operates. For example, a business rule could define how a particular business should act in a given situation (such as when a customer credit card payment is rejected) or a constraint (such as a policy of not selling to anyone under sixteen). A business rules approach to building systems recognizes the importance of business rules, with a view to making it easier to understand and change how the business works. In an ideal world, you'd be able to modify your business rules and all affected systems would instantly jump in line. It's a very attractive prospect. There exist business rules products to help you do this. They act a bit like a guru who knows your business inside-out and of whom you can ask questions, but there's a lot more to it than that. That's not to say you need a specialized product to adopt a business rules approach. Two places to go for more information are http://www.brcommunity.com and http://www.businessrulesgroup.org.

Quite a few types of requirements reflect business rules, including several covered by requirement patterns in this book. So why not say which ones they are? The trouble is that there isn't a single agreed-upon set of business rule types. There are many, and it would be arbitrary to pick one. (The same argument applies when you consider mentioning in an individual requirement how it maps to a business rule.) One could create a requirement pattern classification for a selected business rule scheme to indicate how each pattern relates to a business rule. My excuse for not doing so in this book is not wishing to offend any scheme I left out.

It's also worth pointing out that adopting a particular business rule classification scheme might not happen until after the requirements have been written. Consider the case where you invite tenders from three prospective suppliers. The first might use one business rules scheme. The second might use a different one. And the third might not think in business rules terms at all.

Nevertheless, if your organization has made a commitment to using a particular business rule scheme, you can write requirements in a way that's friendly to that scheme (and, if you wish, mention the type of business rule that each requirement reflects, where applicable). If you're committed to using a business rule product, you can treat it as an infrastructure that your system must interface to. Then, just like for any infrastructure, you can specify requirements for what you need from it, and use those requirements as your basis for choosing the most suitable product.