Chapter 2

Planning for Risk Management

“You can observe a lot just by watching.”

—YOGI BERRA

Planning for risk involves paying attention. When we don’t watch, projects fail.

How many? One frequently quoted statistic is 75 percent. The original source for this assertion is a study done in 1994 by the Standish Group and documented in “The CHAOS Report.” There are reasons to be skeptical of this number, starting with the fact that if three of four projects actually did fail, there would be a lot fewer projects. What the Standish Group actually said in its study was that about a quarter of projects in the sample were cancelled before delivering a result. In addition to this, roughly half of the projects were “challenged,” producing a deliverable but doing it late, over budget, or both. The remaining quarter of the projects they viewed as successful.

Although the Standish Group has done further research over the years with similar results, the actual picture for projects is probably not quite so bleak. The Standish Group studied only large IT projects, those with budgets more than US$2 million. In addition, the survey information did not come from the project leaders but was reported by the executives responsible for the organizations where the projects were undertaken. Larger projects are more prone to fail, and US$2 million is a big IT project (especially in 1994). The source of the data also raises a question about what was being compared to what. Were the projects in fact troubled, or were they doomed from the start by unrealistic expectations that were never validated? Whatever the true numbers for failed projects are, however, too many projects fail unnecessarily, and better risk management can help.

Although unanticipated “acts of God” doom some projects, most fail for one of three reasons:

• They are actually impossible.

• They are overconstrained (“challenged” in the Standish Group model).

• They are not competently managed.

A project is impossible when its objective lies outside of the technical capabilities currently available. “Design an antigravity device” is an example. Other projects are entirely possible, but not with the time and resources available. “Rewrite all the corporate accounting software so it can use a different database package in two weeks using two part-time university students” is an overconstrained project. Unfortunately, there are also projects that fail despite having a feasible deliverable and plausible time and budget expectations. These projects fail because of poor project management—simply because too little thought is put into the work to produce useful results.

Risk and project planning enable you to distinguish among and deal with all three of these situations. For projects that are demonstrably beyond the state of the art, planning and other analysis data generally provide sufficient information to terminate the project or at least to redirect the objective (buy a helicopter, for example, instead of developing the antigravity device). Chapter 3, on identifying project scope risks, discusses these situations. For projects with unrealistic timing, resource, or other constraints, risk and planning data provide you with a compelling basis for project negotiation, resulting in a more plausible objective (or, in some cases, the conclusion that a realistic project lacks business justification). Chapters 4, 5, and 6, on schedule, resource, and other risk identification, discuss issues common for these overconstrained projects. Dealing with “challenged” projects by negotiating a realistic project baseline is covered in Chapter 10.

The third situation, a credible project that fails because of faulty execution, is definitely avoidable. Through adequate attention to project and risk planning, these projects can succeed. Well-planned projects begin quickly, limiting unproductive chaos. Rework and defects are minimized, and people remain busy performing activities that efficiently move the project forward. A solid foundation of project analysis also reveals problems that might lead to failure and prepares the project team for their prompt resolution. In addition to making project execution more efficient, risk planning also provides insight for faster, better project decisions. Although changes are required to succeed with the first two types of projects mentioned earlier, this third type depends only on you, your project team, and application of the solid project management concepts in this book. The last half of this book, Chapters 7 through 13, specifically addresses these projects.

Project Selection

Project risk is a significant factor even before there is a project. Projects begin as a result of an organization’s business decision to create something new or change something old. Projects are a large portion of the overall work done in organizations these days, and there are always many more attractive project ideas than can be funded or adequately staffed at any given time. The process for choosing projects both creates project risk and relies on project risk analysis, so the processes for project selection and project risk management are tightly linked. Selecting and maintaining an appropriate list of active projects requires project portfolio management.

Project selection affects project risk in a number of ways. Poor project portfolio management exacerbates a number of common project risks:

• Too many projects competing for scarce resources

• Project priorities that are misaligned with business and technical strategies

• Inadequately staffed or funded projects

• Unrealistically estimated organizational capabilities

Project risk management data is also a critical input to the project selection process. Project portfolio management uses project risk assessment as a key criterion for determining which projects to put into plan at any given time. Without high-quality risk data and realistic estimates for candidate projects, excessive numbers of projects will be undertaken and many of them will fail. The topic of project portfolio risk management is explored in Chapter 13.

Overall Project Planning Processes

The project selection process is a major source of risk for all projects, but the overall project management approach is even more significant. When projects are undertaken in organizations lacking adequate project management processes, risks will be unknown and probably unacceptably high. Without adequate analysis of projects, no one has much idea of what “going right” looks like, so it is not possible to identify and manage the risks—the things that may go wrong. The project management processes provide the magnifying glass you need to inspect your project to discover its possible failure modes.

Regular review of the overall methods and processes used to manage projects is an essential foundation for good risk management. If project information and control is sufficient across the organization and most of the projects undertaken are successful, then your processes are working well. For many high-tech projects, though, this is not the case. The methods used for managing project work are too informal and they lack adequate structure. Exactly what process you choose matters less than that you are using one. If elaborate, formal, PMBOK®-inspired heavyweight project management works for you, great. If agile, lightweight, adaptive methodologies provide what you need, that’s fine too. The important requirement for risk management is that you adopt and use an effective project management process.

For too many technical projects, there is indifference or even hostility to planning. This occurs for a number of reasons, and it originates in organizations at several levels. At the project level, other types of work may carry higher priority, or planning may be viewed as a waste of time. Above the project level, project management processes may appear to be unnecessary overhead, or they may be discouraged to deprive project teams of data that could be used to win arguments with their managers. Whatever the rationalizations used, there can be little risk management without planning. Until you have a basic plan, most of the potential problems and failure modes for your project will remain undetected.

The next several pages provide support for the investment in project processes. If you or your management need convincing that project management is worthwhile, read on. If project planning and related management processes are adequate in your organization, skip ahead.

At the Project Level

A number of reasons are frequently cited by project leaders for avoiding project planning. Some projects are not thoroughly planned because the changes are so frequent that planning seems futile. Quite a few leaders know that project management methodology is beneficial, but with their limited time they feel they must do only “real work.” An increasingly common reason offered is the belief that in “Internet time,” thinking and planning are no longer affordable luxuries. There is a response for each of these assertions.

Inevitable project change is a poor reason not to plan. In fact, frequent change is one of the most damaging risk factors, and managing this risk requires good project information. Project teams that have solid planning data are better able to resist inappropriate change, rejecting or deferring proposed changes based on the consequences demonstrated using the project plan. When changes are necessary, it is easier to continue the work by modifying an existing plan than by starting over in a vacuum. In addition, many high-tech project changes directly result from faulty project assumptions that persist because of inadequate planning information. Better understanding leads to clearer definition of project deliverables and fewer reasons for change.

The time required to plan is also not a valid reason to avoid project management processes. Although it is universally true that no project has enough time, the belief that there is no time to plan is difficult to understand. All the work in any project must always be planned. There is a choice as to whether planning will be primarily done in a focused, early-project exercise, or by identifying the work one activity at a time, day by day, all through the project. All necessary analysis must be done by someone, eventually. The incremental approach requires comparable, if not more, overall effort, and it carries a number of disadvantages. First, tracking project progress will at best be guesswork. Second, most project risks, even those easily identified, come as unexpected surprises when they occur. Early, more thorough planning provides other advantages, and it is always preferable to have project information sooner than later. Why not invest in planning when the benefits are greatest?

Assertions about “Internet time” are also difficult to accept. Projects that must execute as quickly as possible need more, not less, project planning. Delivering a result with value requires sequencing the work for efficiency and ensuring that the activities undertaken are truly necessary and of high priority. There is no time for rework, excessive defect correction, or unnecessary activity on fast-track projects. Project planning, particularly on time-constrained projects, is real work.

Above the Project Level

Projects are undertaken based on the assumption that whatever the project produces will have value, but there is often little consideration of the type and amount of process that projects need. In many high-tech environments, little to no formal project management is mandated, and often it is even discouraged.

Whenever the current standards and project management practices are inadequate in an organization, strive to improve them. There are two possible ways to do this. Your best option is to convince the managers and other stakeholders that more formal project definition, planning, and tracking will deliver an overall benefit for the business. When this is successful, all projects benefit. For situations where this is unsuccessful, a second option is to adopt greater formalism just for your current project. It may even be necessary to do this in secret, to avoid criticism and comments like, “Why are you wasting time with all that planning stuff? Why aren’t you working?”

In organizations where expenses and overhead are tightly controlled, it can be difficult to convince managers to adopt greater project formalism. Building a case for this takes time and requires metrics and examples, and you may find that some upper-level managers are highly resistant even to credible data. The benefits are substantial, though, so it is well worth trying; anything you can do to build support for project processes over time will help.

If you have credible, local data demonstrating the value of project management or the costs associated with inadequate process, assemble it. Most organizations that have such data also have good processes. If you have a problem that is related to inadequate project management, it is likely that you will also not have a great deal of information to draw from. For projects lacking a structured methodology, few metrics are established for the work, so mounting a compelling case for project management processes using your own data may be difficult.

Typical metrics that may be useful in supporting your case relate to achieving specifications, managing budgets, meeting schedules, and delivering business value. Project processes directly impact the first three, but only indirectly influence the last one. The ultimate value of a project deliverable is determined by a large number of factors in addition to the project management approach, many of which are totally out of the control of the project team. Business value data may be the best information you have available, though, so make effective use of what you can find.

Even if you can find or create only modest evidence that better project management processes will be beneficial, it is not hopeless. There are other approaches that may suffice, using anecdotal information, models, and case studies.

Determining which approaches to use depends on your situation. There is a wide continuum of beliefs about project management among upper-level managers. Some managers favor project management naturally. These folks will require little or no convincing, and any approach you use is likely to succeed. Other managers are highly skeptical about project management and will heavily focus on the visible costs (which are unquestionably real) while doubting the benefits. The best approach in this case is to gather local data, lots of it, that shows as clearly as possible how high the costs of not using better processes are. Trying to convince an extreme skeptic that project management is necessary may even be a waste of time, for both of you. Good risk management in such a skeptical environment is up to you, and it may be necessary to do it “below the radar.”

Fortunately, most managers are somewhere in the middle, neither “true believers” in project management nor chronic process adversaries. The greatest potential for process improvement is with this ambivalent group. Using anecdotal information, models, case studies, and other information can be effective.

Anecdotal information Building a case for more project process with stories depends on outlining the benefits and costs, and showing there is a net benefit. Project management lore is filled with stated benefits, among them:

• Better communication

• Less rework

• Lowered costs, reduced time

• Earlier identification of gaps and inadequate specifications

• Fewer surprises

• Less chaos and firefighting

Finding situations that show where project management delivered on these or where lack of process created a related problem should not be hard.

Project management does have costs, some direct and some more subtle, and you will need to address these. One obvious cost is the “overhead” it represents: meetings, paperwork, time invested in project management activities. Another is the initial (and ongoing) cost of establishing good practices in an organization, such as training, job aids, and new process documentation. Do some assessment of the investment required and summarize the results.

There is a more subtle cost to managers in organizations that set high project management standards: the shift that occurs in the balance of power in an organization. Without project management processes, all the power in an organization is in the hands of management; all negotiations tend to be resolved using political and emotional tactics. Having little or no data, project teams are fairly easily backed into whatever corners their management chooses. With data, the discussion shifts and negotiations are based more on reality. Even if you choose not to directly address this “cost,” be aware of it in your discussions.

Answering the question “Is project management worth it?” using anecdotal information depends on whether the benefits can be credibly shown to outweigh the costs. Your case will be most effective if you find the best examples you can, using projects from environments as similar to yours as possible.

Models Another possible approach for establishing the value of process relies on logical models. The need for process increases with scale and complexity, and managing projects is no exception to this. Scaling projects may be done in a variety of ways, but one common technique segregates them into three categories: small, medium, and large.

Small projects are universal; everyone does them. There is usually no particular process or formality applied, and more often than not these simple projects are successful. Nike-style (“Just Do It”) project management is good enough, and although there may well be any number of slightly better ways to approach the work (apparent in hindsight, more often than not), the penalties associated with simply diving into the work are modest enough that it doesn’t matter much. Project management processes are rarely applied with any rigor, even by project management zealots, as the overhead involved may double the work required for the project.

Medium-size projects last longer and are more complex. The benefits of thinking about the work, at least a little, are obvious to most people. At a minimum, there is a “to do” list. Rolling up your sleeves and beginning work with no advance thought often costs significant additional time and money. As the “to do” list spills over a single page, project management processes start to look useful. At what exact level of complexity this occurs has a lot to do with experience, background, and individual disposition. Many mid-size projects succeed, but the possibility of falling short of some key goal (or complete project failure) is increasing.

For large projects, the case for project management should never really be in doubt. Beyond a certain scale, all projects with no process for managing the work will fail to meet at least some part of the stated objective. For the largest of projects, success rates are low even with program management and systems engineering processes in addition to thorough project management practices.

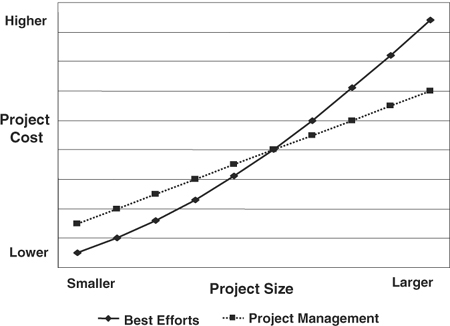

For projects of different sizes, costs of execution with and without good project management will vary. Figure 2-1 shows the cost of a “best effort,” or brute force, approach to a project contrasted with a project management approach. The assumption for this graph is that costs will vary linearly with project scale if project management is applied, and they will vary geometrically with scale if it is not. This figure, though not based on empirical data, is solidly rooted in a large amount of anecdotal information.

Figure 2-1. Cost benefit for project management.

The figure has no units, because the point at which the crossover occurs (in total project size and cost) is highly situational. If project size is measured in effort-months, a common metric, a typical crossover might be between one and four total effort-months.

Wherever the crossover point is, the cost benefit is minor near this point, and negative below it. For these smaller projects, project management is a net cost or of small financial benefit. (Cost may not be the only, or even the most important, consideration, though. Project management methodologies may also be employed for other reasons, such as to meet legal requirements, to manage risk better, or to improve coordination between independent projects.)

A model similar to this, especially if it is accompanied by project success and failure data, can be a compelling argument for adopting better project management practices.

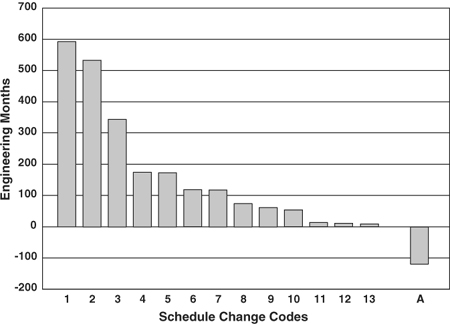

Case studies To offset the costs of project management, you need to establish measurable (or at least plausible) benefits. Many studies and cases have been developed over the years to assess this, including the one summarized in Figure 2-2. The data in this particular study was collected over a three-year period in the early 1990s from more than two hundred projects at Hewlett-Packard. For every project included, all schedule changes were noted and characterized. All changes attributed to the same root cause were aggregated, and the summations were sorted for the Pareto diagram in the figure, displaying the magnitude of the change on the vertical axis and the root causes along the horizontal axis.

Additional project effort—hundreds of engineer months—was associated with the most common root causes. The codes for the root causes, sorted by severity, were:

1. Unforeseen technical problems

2. Poor estimation of effort/top-down schedules

3. Poor product/system design or integration problems

4. Changing product definition

5. Other

6. Unforeseen activities/too many unrelated activities

Figure 2-2. Schedule change Pareto diagram.

7. Understaffed, or resources not on time

8. Software development system/process problems

9. Related project slip (also internal vendor slip)

10. Insufficient support from service areas

11. Hardware development system/process problems

12. Financial constraints (tooling, capital, prototypes)

13. Project placed on hold

A. Acceleration

Not every one of these root causes directly correlates with project management principles, but most of them clearly do. The largest one is unforeseen technical problems, many of which were probably caused by insufficient planning. The second, faulty estimation, is also a project management factor. Although better project management would not have eliminated all these slippages, it surely would have reduced them. The top two reasons in the study by themselves represent an average of roughly five unanticipated engineer-months per project; reducing this by half would save thousands of dollars per project. Similar conclusions may be drawn from the analysis of the Project Experience Risk Information Library (PERIL) database later in this chapter and throughout this book.

Case study data such as these examples, particularly if it directly relates to the sort of project work you do, can be convincing. You likely have access to data similar to this, or could estimate it, for rework, firefighting, crisis management, missing work, and the cost of defects on recent projects.

Other reasons for project management One of the principal motivators in organizations that adopt project principles is reduction of uncertainty. Most technical people hate risk and will go to great lengths to avoid it. One manager who strongly supports project management practices uses the metaphor of going down the rapids of a white-water river. Without project management, you are down in the water—you have no visibility, it is cold, it is hard to breathe, and your head is hitting lots of rocks. With project management, you are up on a raft. It is still a wild ride, but you can see a few dozen feet ahead and steer around the worst obstacles. You can breathe more easily, you are not freezing and are less wet, and you have some confidence that you will survive the trip. In this manager’s group, minimizing uncertainty is important and planning is never optional.

Another motivator is a desire (or requirement) to become more process oriented. Current standards and legal requirements for enterprise risk management in the United States and worldwide make adoption of formal processes for risk management obligatory. (The direct connection of this to project risk management is explored in Chapter 13.) In firms that provide solutions to customers, using a defined methodology is a competitive advantage that can help win business. In some organizations, evidence of process maturity is deemed important, and standards set by organizations such as the Software Engineering Institute for higher maturity are pursued. In other instances, specific process requirements may be tied to the work, as with many government contracts. In all of these cases, project management is mandatory, at least to some extent, whether the individuals and managers involved think it is a good idea or not.

The Project Management Methodology

Project risk management depends on thorough, sustained application of effective project management principles. The precise nature of the project management methodology can vary widely, but management of risk is most successful when consistent processes are adopted by the organization as a whole, because there will be more information to work with and more durable support for the ongoing effort required. If you need to manage risk better on your project and it proves impossible to gain support for more effective project management principles broadly, resolve to apply them project by project, with sufficient rigor to develop the information you need to manage risk.

Defining Risk Management for the Project

Beyond basic project planning, risk management also involves specific planning for risk. Risk planning begins by reviewing the initial project assumptions. Project charters, datasheets, or other documents used to initiate a project often include information concerning risk, as well as goals, staffing assumptions, and other information. Any risk information included in these early project descriptions is worth noting; sometimes projects believed to be risky are described as such, or there may be other evidence of project risk. Projects that are thought to be low risk may involve assumptions leading to unrealistically low staffing and funding. Take note of any differences in your perception of project risk and the stated (or implied) risks perceived by the project sponsors. Risk planning builds on a foundation that is consistent with the overall assumptions and project objectives. In particular, work to understand the expectations of the project stakeholders, and adopt an approach to risk management that reflects your environment.

Stakeholder Risk Tolerance

Organizations in different businesses deal with risk in their own ways. Start-ups and speculative endeavors such as oil exploration generally have a high tolerance for risk; many projects undertaken are expected to fail, but these are compensated for by a small number that are extremely successful. More conservative organizations, such as governments and enterprises that provide solutions to customers for a fee, are generally risk averse and expect consistent success but more modest returns on each project. Organizational risk tolerance is reflected in the organizational policies, such as pre-established prohibitions on pursuing fixed-price contract projects.

In addition, the stakeholders of the project may have strong individual opinions on project risk. Although some stakeholders may be risk tolerant, others may wish to staff and structure the work to minimize extreme outcomes. Technical contributors tend to prefer low risk. One often-repeated example of stakeholder risk preference is attributed to the NASA astronauts, who observed that they were sitting on the launch pad atop hundreds of systems, each constructed by the lowest bidder. Risk tolerance frequently depends on your perspective.

Planning Data

Project planning information supports risk planning. As you define the project scope and create planning documents such as the project work breakdown structure, you will uncover potential project risks. The planning processes also support your efforts in managing risk. The linkages between project planning and risk identification are explored in Chapters 3 through 6.

Templates and Metrics

Risk management is easier and more thorough when you have access to predefined templates for planning, project information gathering, and risk assessment. Templates that are preloaded with information common to most projects make planning faster and decrease the likelihood that necessary work will be overlooked. Consistent templates created for use with project scheduling applications organizationwide make sharing information easier and improve communication. If such templates exist, use them. If there are none, create and share proposed versions of common documents with others who do similar project work, and begin to establish standards.

Risk planning also relies on a solid base of historical data. Archived project data supports project estimating, quantitative project risk analysis, and project tracking and control. Examples of metrics useful for risk management are covered in Chapter 9.

Risk Management Plan

For small projects, risk planning may be informal, but for large, complex projects, you should develop and publish a written risk management plan. A risk management plan includes information on stake-holders, planning processes, project tools, and metrics, and it states the standards and objectives for risk management on your project. While much of the information in a risk plan can be developed generally for all projects in an organization, each specific project has at least some unique risk elements.

A risk plan usually starts by summarizing your risk management approach, listing the methodologies and processes that you will use, and defining the roles of the people involved. It may also include information such as definitions and standards for use with risk management tools; the frequency and agenda for periodic risk reviews; any formats to be used for required inputs and for risk management reports; and requirements for status collection and other tracking. In addition, each project may determine specific trigger events and thresholds for metrics associated with project risks, and the budgets for risk analysis, contingency planning, and risk monitoring.

Another aspect of risk planning is ensuring that risk management plans include adequate attention to project opportunities. The uncertainty inherent in projects means that some things may go better than expected. Considering project options that represent better opportunities can be at least as important to managing project risk as managing potential threats. Project opportunity management is discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

The PERIL Database

Good project management is based on experience. Fortunately, the experience and pain need not all be personal; you can also learn from the experience of others, avoiding the aggravation of seeing everything firsthand. The Project Experience Risk Information Library (PERIL) database provides a step in that direction.

For more than a decade, in conducting workshops and classes on project risk management, I have been collecting data anonymously from hundreds of project leaders on their past project problems. Their descriptions included both what went wrong and the amount of impact it had on their projects. I have compiled this data in the PERIL database, which serves as the foundation for this book. The database describes a wide spectrum of things that have gone wrong with past projects, and it provides a sobering perspective on what future projects will face. Since the version of the PERIL database I used in the first edition of this book, the number of included cases has nearly tripled, to well over 600.

Some project risks are easy to identify because they are associated with familiar work. Other project risks are more difficult to uncover because they arise from new, unusual, or otherwise unique requirements. The PERIL database is valuable in helping to identify at least some of these otherwise invisible risks. In addition, the PERIL database summarizes the magnitude of the consequences associated with key types of project risk. Realistic impact information can effectively counteract the generally optimistic assessments typically used for project risks. Although some of the specific cases in the PERIL database relate only to certain types of projects or may be unlikely to recur, some close approximation of these situations will be applicable to most technical projects.

Sources for the PERIL Database

The information in the PERIL database comes primarily from participants in classes and workshops on project risk management, representing a wide range of project types. Slightly more than half the projects are product development projects, with tangible deliverables. The rest are information technology, customer solution, or process improvement projects. The projects in the PERIL database are worldwide, with a majority from the Americas (primarily United States, Canada, and Mexico). The rest of the cases are from Asia (mostly Singapore and India) and from Europe and the Middle East (from about a dozen countries, but largely from Germany and the United Kingdom). As with most modern projects, whatever their type or location the projects in the PERIL database share a strong dependence on new or relatively new technology. The majority of these projects also involved software development. There are both longer and shorter projects represented here, but the typical project in the database had a planned duration between six months and one year. Although there are some large programs in PERIL, typical staffing on these projects was rarely larger than about twenty people.

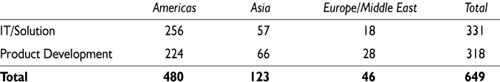

The raw project numbers in the PERIL database are presented in the following table.

Although the PERIL database represents many projects and their risks, with only 600 examples, it is far from comprehensive. The database contains only a small fraction of the thousands of projects undertaken by the project leaders from whom it was collected, and it does not even represent all the problems encountered on the projects that are included. Because of this, analysis of the data in the PERIL database is more suggestive of potential project risks than definitive. Despite this, the overall analysis of the current data corroborates the conclusions reached from the earlier, smaller database, so the broad trends appear to be holding up.

Also, as with any data based on nonrandom samples, there are inevitable sources of bias. The database contains a bias for major project risks, because the project leaders were asked to provide information on significant problems. Trivial problems are excluded from the data by design. There is also potential bias because each case was self-reported. Although all the information included is anonymous, some embarrassing details or impact assessment may well have been omitted or minimized. In addition, nearly all of the information was reported by people who were interested enough in project and risk management to invest their time participating in a class or workshop, so they are at the least somewhat skilled in project management. This could cause problems related to poor project management to be underrepresented.

Even considering these various limitations and biases, the PERIL database does illuminate a wide range of risks typical of today’s projects. It is filled with constructive patterns, and the biggest source of bias—a focus on only major problems—accurately mirrors accepted strategies for risk management. Nonetheless, before blindly extending the following analysis to any particular situation, be aware that your mileage may vary.

Measuring Impact in the PERIL Database

The problem situations that make up the PERIL database resulted in a wide range of adverse consequences, including missed deadlines, significant overspending, scope reductions, and a long list of other undesirable outcomes that were not easily quantified. Although such an extensive assortment of misery may be fascinating, it is difficult to pummel into a useful structure. To this end, I chose to normalize all the quantitative data in the database using only time impact, measured in weeks of project slippage. This tactic makes sense in light of today’s obsession with meeting deadlines, and it was an easy choice because by far the most prevalent serious impact reported in this data was deadline slip. Focusing on time is also appropriate because among the project triple constraints of scope, time, and cost, time is the only one that’s completely out of our control—when it’s gone, it’s gone.

For cases where the impact reported was primarily something other than time, I either worked with the project leader to estimate an equivalent project slippage or excluded the case from the database. For example, when a project met its deadline by using significant overtime, we estimated the slippage equivalent to working all those nights, weekends, and holidays. If a project found it necessary to make significant cuts to the project scope, we estimated the additional duration that would have been required to retain the original scope. Where such transformations are included in the PERIL database, we used conservative methods in estimating the adjustments.

To better reflect the reality of typical projects, the time data in the PERIL database also excludes extremes. In keeping with the theme of focus on major risk, projects that reported a time slippage of less than a week were not included. On the assumption that there are probably better options for projects that overshoot their deadlines by six months or more, the cases included that reported longer slips are capped at twenty-six weeks. This prevents a single case or two from inordinately skewing the analysis, while retaining the root cause of the problem. Because of their enormous and disruptive potential impact, these and other significant cases will receive more detailed attention later in this book.

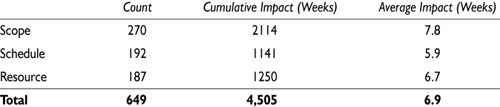

The average impact for all records was roughly seven weeks, representing almost a 20 percent slip for a typical nine-month project. The averages by project type were consistently close to the average for all of the data, with product development projects averaging a bit more than seven weeks and IT and solution projects slightly less than seven weeks. By region, projects in the Americas and in Europe and the Middle East averaged slightly more than seven weeks. Asian projects were slightly better, but still nearly six weeks. This data by region and project type includes average impact, in weeks.

Risk Causes in the PERIL Database

Although the consequences of the risks in the PERIL database are consistently reported based on time, the risk causes were varied and abundant. One approach to organizing this sort of data uses a risk breakdown structure (RBS) to categorize risks based on risk type. The categories and subcategories I have used to structure the database form an example of an RBS. Each reported problem in the database is characterized in the hierarchy based on its principal root cause. The top level of the hierarchy is organized similarly to the first half of this book, around the project triple constraints of scope, schedule (or time), and resource (or cost). The database subdivides these types of risks based on further breakdown of the root causes of the risks. For most of the risks, determining the principal root cause was fairly straightforward. For others, the problem reported was a result of several factors, but in each case, the risk was assigned to the project parameter that was most significant.

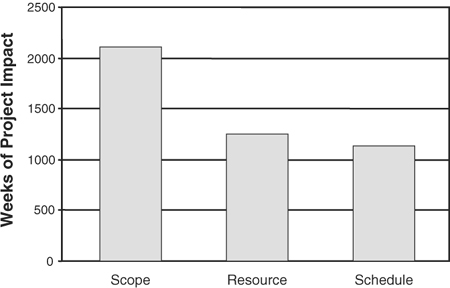

Across the board, risks related to scope issues were dominant. They were both most frequent and, on average, most damaging. Although schedule risks were next most numerous, on average resource risks were slightly more harmful. The typical slippage for risks within each major type represented from about a month and a half to two months.

The total impact of all the risks is a bit more than 4,500 weeks—almost ninety years—of slippage. A Pareto chart summarizing total impact by category is shown in Figure 2-3.

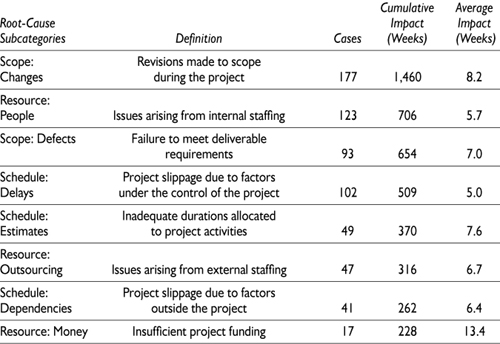

Within each of these three categories the data is further subdivided based on root-cause categories, using the following definitions.

Figure 2-3. Total project impact by root-cause category.

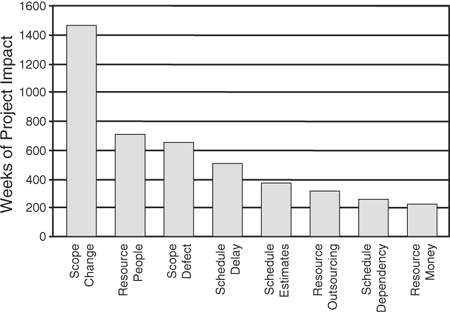

A Pareto of the cumulative impact data is shown in Figure 2-4. By far the largest source of slippage in this Pareto chart is scope change; it is more than twice as large as the next subcategory. One positive aspect of this data is that the top five subcategories are all things that are at least partially within the purview of the project leader. This suggests that more focus on the things that you can control as a project leader can significantly reduce the number and magnitude of unpleasant surprises you’ll encounter during your projects. This idea, along with further decomposition of these risk root-cause categories, is explored through the next three chapters, with scope risks discussed in Chapter 3, schedule risks in Chapter 4, and resource risks in Chapter 5.

Figure 2-4. Total project impact by subcategory.

Big Risks

Most books on project risk management spend a lot of time on theory and statistics. The first edition of this book departed from that tradition by focusing instead on what actually happens to real projects, using the PERIL database as its foundation. The point was to illuminate significant sources of actual project risk, with specific suggestions about what to do about the most serious problems—the “black swans.”

Calling such risks “black swans” has been popularized of late by the writings of Nassim Nicholas Taleb. The notion of a black swan originated in Europe before there was much knowledge of the rest of the world. In the study of logic, the statement “All swans are white” was used as the example of something that was incontrovertibly true. Because all the swans observed in Europe were white, a black swan was deemed impossible. It came as something of a shock when a species of black swans was later discovered in Australia. This realization gave rise to the metaphorical use of the term “black swan” to describe something erroneously believed to be impossible.

Taleb’s primary subject matter (discussed in depth in his 2001 book, Fooled by Randomness) is financial risk, but his concept of a black swan as a “large-impact, hard-to-predict, rare event” is nonetheless applicable to project risk management. It is a mistake to consider a situation as impossible merely because it happens rarely or has not happened yet. In projects, it is common for project leaders to discount major project risks because they are estimated to have extremely low probabilities. But these risks do occur—the PERIL database is full of them—and the severity of problems they cause means that ignoring them can be unwise. When these risks do occur, the same project managers who initially dismissed them come to perceive them as much more predictable—sometimes even inevitable.

In the next three chapters, we will heighten visibility of these project-destroying “black swans” by singling out the most severe 20 percent of the risks in the PERIL database—the 127 cases representing the most schedule slippage. The definition of a “large-impact, hard-to-predict, rare event” is a useful starting point, but as the database shows, these most damaging risks are not as rare as might be thought, and they need not be so difficult for project managers to predict if they get appropriate attention in the risk management process.

Half of the “black swans,” sixty-four, are scope risks. Schedule and resource risks are fewer, each constituting about a quarter of the total. These risks caused projects to slip at least three months, and they account for over half of the total damage in the PERIL database, almost 2,500 weeks of accumulated slip. The next three chapters will dig into the details of these risks, with the goal of improving your chances of identifying them in future projects. In the second half of the book, we will explore response tactics for dealing with these and other significant project risks.

A Second Panama Canal Project: Sponsorship and Initiation (1902–1904)

“A man, a plan, a canal. Panama.”

—FAMOUS PALINDROME

Successful projects are often not the first attempt to do something. Often, there is a recognized opportunity that triggers a project. If the first attempted project fails, it discourages people for a time. Soon, however, if the opportunity remains attractive another project will begin, building on the work and the experiences of the first project. A canal at Panama remained an attractive opportunity. When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, he decided to make successful completion of a Central American canal part of his presidential legacy. (And so it is. He is the “man” in the famous palindrome.)

As much as the earlier French project failed because of lapses in project management, the U.S. project ultimately succeeded as a direct result of applying good project principles. The results of better project and risk management on this second project will unfold throughout the remainder of this book.

Unlike the initial attempt to build a canal, the U.S. effort was not a commercial venture. Maintaining separate U.S. navies on the East and West coasts had become increasingly costly. Consolidation into a single larger navy required easy transit between the Atlantic and Pacific, so Theodore Roosevelt saw the Panama Canal as a strategic military project, not a commercial one. The U.S. venture considered several routes, but as the French had done, they selected Panama.

Theodore Roosevelt was a more typical project sponsor than Ferdinand de Lesseps. He delegated the management of the project to others. His greatest direct contribution to the project was in “engineering” the independence of Panama from Colombia. (This “revolution” was accomplished by a pair of gunboats, one at Colon on the Gulf of Mexico and another at Panama City on the Pacific. Without the firing of a single shot, the independent nation of Panama was created in 1902. Repercussions of this U.S. foreign policy decision persist, more than a century later.) To get the project started quickly, Roosevelt also moved to acquire the assets of the Nouvelle Compagnie (which returned some relief to shareholders of the original company, but not much).

“I took the isthmus!” Roosevelt said. He then went to the U.S. Congress to get approval to go forward with the building of the canal. Following all this activity and the public support it generated, Congress had little choice but to support the project. Although the specifics for the project were still vague, the intention of the United States was clear: to build a canal at Panama capable of transporting even the largest U.S. warships, and to build it as quickly as was practical.

Insight into Roosevelt’s thinking concerning the project is found in this quote from 1899, two years before his presidency:

Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in the gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat.

Project sponsors often aspire to “dare mighty things.” They are much more risk tolerant than most project leaders and teams. Good risk management planning serves to balance the process of setting project objectives, so we undertake projects that are not only worthwhile and challenging but also possible.