CHAPTER 2

What Gets in

Our Way?

For many of us, conflict is a dirty word. Some of us try to escape conflict by burying our heads, turning away, not bringing it up. Others try to get out of the situation as quickly as possible by force of will—I’ll just tell them what to do and be done with it. Why do we work so hard to get rid of conflict?

Again and again, business books and journals praise the advantages of engaging in constructive conflict resolution. Authors and researchers tell us how conflict can improve productivity and performance, strengthen teamwork, and become a catalyst for creative problem solving. We read and nod our heads in agreement. We attend seminars and workshops about it all the time. Yes, we believe all of this in theory. So why is it so hard to apply the theories in our own workplaces? This book is not about “Get over conflict so that you can get your team back to work.” Rather, this book is about learning to see conflict as an inevitable, essential part of the work itself. But, first, a story.

I have said it before, and I’ll say it again. Conflict is inevitable. When what you want, need, or expect gets in the way of what I want, need, or expect, we have a conflict. Why don’t we resolve all of our conflicts when they first arise as mere disagreements, before they flare into bigger problems? Four stumbling blocks often get in our way: fear, blame, assumptions, and habits.

Fear as a Stumbling Block

We can easily address disagreements and misunderstandings. We listen, we find a way forward, we move on to the next item on the to-do list. Unless that doesn’t work. If we don’t listen, or find a way forward, it can take time before we see the situation as a conflict. By that time, frustration has mounted, the problem looms larger, and fear sets in. That fear can spin us swiftly into panic or anger, driving us to take drastic action quickly.

Tre and his staff spent a couple of years reacting unconsciously to their fears. When confusion, contention, or indecision arose, Tre’s immediate response was to kick into gear, yelling at someone on the team about what must be done immediately to fix the problem, to fix it his way and on his timetable. When the boss yelled at them, the staff’s reaction was to get busy and to get quiet. What did Tre fear? What did staff members fear? In a conflict, what do we fear?

![]() We fear change and the loss that change might bring.

We fear change and the loss that change might bring.

![]() We fear making a mistake and being seen as incompetent.

We fear making a mistake and being seen as incompetent.

![]() We fear losing face—losing our reputation or our pride, honor, dignity.

We fear losing face—losing our reputation or our pride, honor, dignity.

![]() We fear being hurt. We fear being hurt physically. We fear the words that might hurt. The emotional memories of pain live in our hearts long after the physical pain has healed.

We fear being hurt. We fear being hurt physically. We fear the words that might hurt. The emotional memories of pain live in our hearts long after the physical pain has healed.

![]() We fear what the conflict might say about the other person, or about our relationship.

We fear what the conflict might say about the other person, or about our relationship.

![]() We fear hurting someone else. We might fear our own physical strength and the damage we could do. We might fear saying something that can’t be pulled back out of the air once it has been spoken.

We fear hurting someone else. We might fear our own physical strength and the damage we could do. We might fear saying something that can’t be pulled back out of the air once it has been spoken.

![]() We fear how the conflict might affect the future, and our future relationships.

We fear how the conflict might affect the future, and our future relationships.

![]() We fear being disrespected or dismissed; we fear being embarrassed.

We fear being disrespected or dismissed; we fear being embarrassed.

![]() We fear losing control; we fear feeling powerless.

We fear losing control; we fear feeling powerless.

![]() We fear being seen as weak, incompetent, or unworthy.

We fear being seen as weak, incompetent, or unworthy.

![]() We fear being abandoned. We fear being unlovable.

We fear being abandoned. We fear being unlovable.

Consider this: Anger is a secondary emotion, often caused by the fears named here. In reaction to that anger, we have two automatic responses: fight or flight.

Some of us prefer the fight mode. Put your dukes up and start swinging. The best defense is a good offense. Win before they know what hit them. If a staff member disagrees with your idea, cut him off, let him know immediately that you are right, and the question is settled. To thwart the possibility of an argument, let him know, then and there, who is boss—in no uncertain terms. In the face of conflict with his staff, Tre came in swift and firm and demanding, leaving no room for further discussion.

Others of us take the flight option instead. It feels much more comfortable, much easier to avoid the difficult moments than to open up the possibility of differences that might explode into some unknown territory, where the monsters of unbridled emotion leap up to take over the discussion. Jack, the HR director, asked us how, if the SMT was so upset, could Tre have been given such positive ratings on the survey? The answer? Intimidated by his authority and the way he used it, they had chosen flight. Tre had warned them when the survey came out to give him a positive review. Fearing his wrath, they silenced their concerns and gave the “right” answers.

In a heated dispute, if the fears are high enough, there is that moment in the middle of the fight where one person threatens the other. If we know each other well, if we’ve been working together long enough, or if one of us has a position of power or authority over the other, we’ve got lots of ammunition. Even the possibility of this kind of threat can create the fear of having any type of conflict.

Hanging over the employee’s head is that nuclear threat, “You’re fired!” The vagaries of the marketplace over the past few years have taught us that the security we count on from our jobs is not as secure as it once was. For Debbie, the Deputy Commissioner, the threat she heard from the SMTs was not “You’re fired” but “I’m leaving.” There are other catastrophic threats: “I’ll kill you for that”; or “I’ll take my friends with me when I go”; or “I’ll steal the company clients or secrets, or destroy the computer database on my way out.”

Fear can be a real showstopper when it comes to conflict. It stops even our willingness to entertain differences of opinion that may open up into a confrontation. The very thought of conflict is just too risky. The fight or flight options we turn to in response to that fear are often more likely to create increased conflict than to resolve it. We lose valuable opportunities to find creative solutions and build staff commitment.

Eleanor Roosevelt once gave this advice: “Do one thing every day that scares you.” For those of us who are held captive by our fear of conflict, this wisdom can move us into taking positive action to address those situations that we are not handling well.

Consider This

![]() In your own work environment, what are the situations that you fear?

In your own work environment, what are the situations that you fear?

![]() In those situations, what do you fear?

In those situations, what do you fear?

![]() Identify one situation that’s a little scary that you would like to address in a different way.

Identify one situation that’s a little scary that you would like to address in a different way.

Blame as a Stumbling Block

Tuesday, May 11, 2010. Three executives in business suits filed into a U.S. Senate hearing room and took their places at a large table behind name tents and microphones. Each was committed to assigning blame to the other two. Meanwhile, 1,000 miles away and 1 mile below the surface of the water, oil continued to gush into the Gulf of Mexico at 60,000 barrels per day. BP Oil pointed to Transocean’s blowout preventer, Transocean blamed the cement and casing that Halliburton supplied, Halliburton pointed back at BP and Transocean. Blame spewed in the hearing room almost as furiously as the oil from the broken pipe on the ocean floor. But blame did not fix the problem.

When a conflict, a problem, or a disagreement arises, our first instinct is to figure out who is to blame. If we can pin the blame on someone or something else, then we don’t have to deal with it any more—it’s their fault, not ours. Let them figure it out. Watching the effects of this approach is enlightening—and disheartening. In an office where the boss hears any discussion of a difficulty, a mistake, or a problem and immediately begins to look for someone to blame, staff shut down. No one wants to raise an issue that needs to be addressed for fear of being blamed. Staff become demotivated as they grow anxious about who will be next.

In one office where I worked, the penalty for a mistake was banishment from the inner circle. Once blame was fixed, the project was assigned to someone else. That someone else would quickly become overloaded with work and then grow resentful, while others saw the boss’s actions as favoritism. On the other hand, some of us are more inclined to take the blame. “It’s my fault.” “I don’t have the skill.” “I made the mistake.” Here again, assigning the blame to one’s self does nothing to address the conflict or the problem.

It is a fine line to walk between accepting responsibility, holding people accountable for their actions, and shifting into blame solely for the sake of blame. In managing employees, holding them accountable for their actions and making clear their responsibilities in getting the work done is essential. However, many times, the “blame game” just keeps us from dealing with the real issues at hand.

Assigning blame to someone else is a delicious temptation. It looks like the conflict will be much easier to address or to resolve if we can first figure out whose fault it is. Then, if we can fix the individual, the problem is solved. When we look further into the conflict, however, nine times out of ten we have had some role in creating, contributing to, or exacerbating the situation.

In the opening story, the Senior Leadership Team came in with their lists of complaints about Tre, going back over the previous three years. Yes, there was a lot they could blame him for. But then the HR Director had a challenging question for each SMT member: “Why didn’t you raise this sooner?” As frustrated as they were with their boss, they too had some responsibility to tackle the difficult issues before they became too big. Time spent assigning blame is only time not spent in finding a way forward.

Over the years, I have conducted hundreds of these interviews in all kinds of offices. My first task is usually to conduct an assessment, to understand what the issues and concerns are, so that I can put together a plan for helping everyone get back to work. Naomi was the first one, the only one, who did not start by blaming others for the challenges her office faced. It took courage for her to move out of the comfort zone of blame and begin to examine the situation to see what responsibility she might have.

Consider This

![]() How often do you find yourself assigning blame? When is it useful, when is it not?

How often do you find yourself assigning blame? When is it useful, when is it not?

![]() Instead of assigning blame, have you considered what part you play in this conflict?

Instead of assigning blame, have you considered what part you play in this conflict?

![]() Given where you are now, how can you best address the situation?

Given where you are now, how can you best address the situation?

Assumptions as Stumbling Blocks

Third on the list of stumbling blocks is our eagerness to make assumptions. We make assumptions unconsciously and take action without thinking. This creates conflict and makes working through differences more difficult. Consider this example.

When I heard this story, I could only imagine how this woman’s face flushed with embarrassment when she realized her mistake. We have all been there ourselves, making an assumption, stepping into our response, and quickly discovering how foolish we have been.

How quickly we move from seeing or hearing a piece of information and translating it into, I know what that means, then taking swift action—saying or doing something we may later regret. We each carry a host of built-in assumptions that inform our thinking and our actions. Many of these assumptions are useful in getting us through the day. We need to organize information into manageable categories and expectations. For example, we assume that equipment will work when we count on it, that others in the office will show up and complete the tasks assigned to them. Life would be too difficult to navigate if we didn’t have sets of assumptions about how the world works and what behavior to expect from others.

We carry many assumptions—ideas that we take for granted—based on our experience or culture. Some of our assumptions are about conflict itself. For some of us, the thought of losing in a conflict is devastating. If we questioned that assumption, though, we might discover that often life goes on fairly comfortably even without winning every contest. We carry assumptions about how others see us and those assumptions often drive our behaviors. If we challenge those assumptions, we may discover that others do not even notice actions that loom large in our own minds. We may assume that if we stand up to someone who disagrees or if we say something the person doesn’t like, that person will leave. But sometimes it takes courage to step out in the face of these assumptions, to change our behavior and see what the results might be.

Managers carry assumptions about information and communication. Sometimes managers assume that people in the office don’t really need to know what is going on within the broader organization, that all they need to know is the task they have been given to do. Other times, managers assume that others know critical information, operating under some vague notion that “everybody knows that.” These assumptions can be particularly appealing and dangerous for managers—appealing because communication takes time, and if people already know, or don’t need to know, it can save a lot of time. It’s also dangerous because, in the absence of accurate and timely information, employees will fill the void with rumors, gossip, and assumptions of their own making.

We have expectations or fixed ideas about people who talk differently or dress differently from how we do. Sometimes those assumptions morph into stereotypes, out of which we create prejudices. This often happens when we are dealing with people we don’t trust or don’t know very well. Our assumptions—the meaning that we unconsciously attach to our differences—lead us into saying or doing things that can be wrong, sometimes disastrously wrong, as in the story of the woman at the Cosmos Club.

“He’s a narcissist.” “She’s just lazy.” “He’s rude.” “She is a liar.” “He’s such a whiner, or a coward, or a bully, or….” Feel free to insert your own list here. It is perilously easy to slip into these fundamental attribution errors—deciding that the reason someone acts the way he does is because of a permanent character flaw, rather than for situational reasons. Before assuming and assigning some negative label, begin by considering that this person has good reasons for his behavior by asking yourself: “Why might a sensible, reasonable person act this way?” Better yet, talk to the person to find out, in a nonconfrontational way, what’s going on, or how he sees the situation. Don’t assume you know why others are acting (or have acted) the way they do.

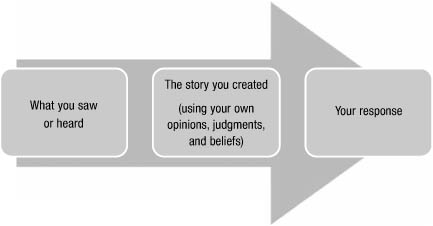

Figure 2-1. Assumptions often drive behavior.

As managers, the lure of assumptions can carry more risk. In general, we assume that “we” are right and “they” are wrong. If you are a manager or a supervisor, it can seem even more important to be right, or to maintain the appearance of being right. Sometimes, managers feel that their authority will be questioned if they are not always right. The need to maintain this facade can undermine a person’s credibility, rather than increase it. It takes more confidence and strength for someone to admit that she doesn’t have all the answers than to try to look like she does. You might want to test this idea for yourself. Listen to the people whom you respect and admire. Are they willing to admit when they don’t have an answer or when they make a mistake? At times it is assumptions that start a conflict in the first place. Someone hears or sees something, makes a snap judgment about it, and takes action. We may not find out for a long time that our interpretations of the event were dead wrong. Figure 2-1 illustrates this flow of action.

Someone else sitting in that meeting could have seen the same incident and have created a totally different story about what was happening. Within a few minutes, the administrative assistant walked into the room with a birthday cake for another employee, and I realized what the note was about—and how foolish my own assumptions had been.

These stories point out another dangerous set of assumptions: assuming that we know why someone is doing what he or she is doing. These assumptions sound like: “She’s avoiding me because she doesn’t like people like me.” “He’s trying to get me in trouble.” “She wants my job.” “He thinks I’m not very smart.” “I know why she’s doing that.” As a mediator, I often have to remind people to speak for themselves, from their own experience, to describe what they saw or heard without taking the story into what they thought was happening or what they thought was intended.

Sometimes I help people imagine all of the possibilities about what else might be going on in a situation—to help them question the story they are telling themselves about what has occurred and how they have filled it with their own assumptions. In Chapter 13, “Reaching Agreement: A Solution-Seeking Model,” and Chapter 15, “Saying What Needs to Be Said,” I offer further guidance on examining your assumptions.

Consider This

Try this example: “She has the information I need. She didn’t answer my e-mail because she wants me to fail. She’s always wanted this project and resented me because the boss gave it to me. She is a snake. Don’t trust her with anything.”

![]() What assumptions is the speaker making about the information?

What assumptions is the speaker making about the information?

![]() What assumptions is the speaker making about the e-mail?

What assumptions is the speaker making about the e-mail?

![]() What assumptions is the speaker making about the project?

What assumptions is the speaker making about the project?

![]() What assumptions is the speaker making about her?

What assumptions is the speaker making about her?

In an argument, this swift conversion from observable facts to “story” to action can take over and fly far beyond any place for meaningful dialogue. As I discuss further in Chapter 10, “Rethinking Anger,” when we are overwhelmed with our own emotions, we don’t have access to rational thought. Our hearing is blocked. In those moments, someone says one thing and what we hear is something totally different. The difficulty, or the challenge, is that these assumptions can spring spontaneously to our minds, usually without our even being aware of what we have done.

How do you keep from being driven by your assumptions? You slow down. You start by getting curious. You ask lots of questions. And then you listen to the answers. Before you jump to conclusions, you think about what you are thinking and why—what opinions or judgments you are bringing to what you have seen or heard.

Sometimes it’s easier to start by looking back. You can think about a situation in which you had a difficult conversation. You can identify where it got out of control or started going in a direction you didn’t want it to go. What happened there? What part did you play? What were you thinking? Reflecting on past experiences can help slow you down in future situations. Then you can more easily spot the assumptions you readily make before you act on them.

Consider This

![]() Think of a recent miscommunication you had. Briefly describe what happened. What did you see and hear? Identify just the observable facts, removing all of your opinions and judgments.

Think of a recent miscommunication you had. Briefly describe what happened. What did you see and hear? Identify just the observable facts, removing all of your opinions and judgments.

![]() What did you think and feel in that moment?

What did you think and feel in that moment?

![]() What were your assumptions? What judgments or opinions did you have about the other person’s intentions?

What were your assumptions? What judgments or opinions did you have about the other person’s intentions?

![]() What did you do?

What did you do?

![]() What else might have been going on? Identify several alternate possibilities or explanations.

What else might have been going on? Identify several alternate possibilities or explanations.

![]() What could you do differently next time?

What could you do differently next time?

Habits as Stumbling Blocks

The fourth stumbling block to dealing with conflict effectively is habit. We have automatic responses and reactions when differences arise or conversations become tense. We are quick to spring into action and wonder later, “How did that happen?” My husband pointed out to me in the middle of an argument that I was physically backing out of the room. “Where are you going?” I realized it wasn’t just with him that I left the scene whenever possible. I saw in this moment my sometimes unconscious tendency to avoid conflict. Once I could recognize this, I became more aware of my pattern in other situations as a habit and continue to work to change it.

From a very early age, we all learned how to deal with conflicts and disagreements. We watched parents and dealt with siblings. Through trial and error, and lots of practice, we found out how to get our needs met—what worked and what didn’t. We discovered how to manage when what others (parents, siblings, teachers, aunts, uncles…) wanted got in the way of what we wanted. We were taught the unwritten rules of the house and the community. We also found out that what worked in our own home probably didn’t work in someone else’s home. We learned who we could turn to and how to get a response.

We learned what to value. Success? Winning? Harmony? Creativity? Hard work? Achievement? We also learned what was not important. We learned by noticing what got us attention or approval, and what didn’t. We learned by watching our parents or others around us. Those who grew up with brothers and sisters learned a lot about how to get along—the oldest learned a different set of skills and strategies than the middle child or the youngest.

Often, when I coach people through conflicts in work situations, they begin to recognize the patterns from their past. Sammy will see that the difficulties he has dealing with his boss replicate the arguments and challenges he had with his father. Karen will realize that her problems with a co-worker are just like the ones she had with her sister.

By the time we were old enough to get jobs, those habits of thought and behavior had been deeply set. We had practiced the ones that worked, over and over again. We had abandoned the ones that didn’t—in our home, in our position in the family, in our own culture. If it didn’t work, if it wasn’t rewarded, we pretty quickly stopped doing it.

All of us want attention; all of us want to be special. Some of us got praise and attention for performing well in school. Others of us were rewarded for being quiet, or friendly, or kind. There were others who got attention for being bad—for getting into trouble. Even if it was negative attention, at least somebody noticed. So that behavior, too, was reinforced. We bring those patterns and habits with us to the workplace, along with our briefcases and lunch bags.

Hence, someone who learned that avoiding conflict was the best way to get through the day will do the same at work. Another who got her needs met by being confrontational will use that same approach on the job when the chips are down. These patterns become well-worn behavioral grooves. In a moment of disagreement, we don’t need to think; we just respond and move on to the next task. In Chapter 3, “What We Need: The Satisfaction Triangle,” I explore further these patterns of response and give you some tips on how to manage them more effectively.

The challenge of these habits is made more difficult when the working relationship has not been working very well for a long time. When only one person in a relationship is aware of the problems faced in resolving differences productively, and tries to change that pattern by responding in a new way, using new skills and tools, the likely reaction will be resistance. The second person will often dig in, continuing to respond in a negative way because the dysfunctional dance of conflict has become comfortable, even if it is not productive. To change that dance, the first person will need to maintain a strong commitment to changing that behavior until the second may eventually shift as well.

I end this chapter almost where I began it. You can read and talk about better ways to respond to conflict, using books and journals and seminars, and with tools and processes and formulas for better managing conflict. Yet, do you still find yourself caught in dysfunctional conflicts? Until you understand the patterns and habits you have developed over a lifetime, and consider ways to put them aside, you are likely to continue repeating your mistakes. It’s time to change.

![]() Where are your most challenging conflicts at work?

Where are your most challenging conflicts at work?

![]() What triggers your automatic negative responses?

What triggers your automatic negative responses?

![]() What patterns and habits do you see reflected in these negative responses?

What patterns and habits do you see reflected in these negative responses?