9

How to Develop and Support Your Network-Oriented Workplace

THIS CHAPTER is written for leaders who want to move from the old command-and-control way of working toward a more collaborative culture. But no matter what your role or level, you’ll benefit from getting a look at what leaders are thinking and how you can contribute more to your organization’s success.

Strategic Connections focuses on how to create the face-to-face relationships, built on trust, that lead to the most productive collaboration. We asked a leader at a large consulting firm, “How do you make sure your employees know how to develop trust with each other?” Looking surprised, he replied, “It’s part of our corporate mandate!”

After reading this book, you won’t assume that just because you tell people to collaborate they’ll know how to do it and will leap into action. Listing “a collaborative culture” as a company imperative or value isn’t enough. Why? Because trust-building, the precondition for collaboration, is a learned skill set, one that involves specific steps and nuanced concepts.

In any relationship, the risk you’re willing to take and the value you derive are both determined by the Stage of Trust you’ve reached. The challenge arises because most people don’t have any system or method for gauging the Stage of Trust they’ve achieved or for managing the trust-building process.

The 8 Competencies featured in the first eight chapters of this book deliver the trust-building methodologies and best networking practices you need. As employees master these state-of-the-art skills, your calls for increased collaboration will no longer fall on deaf ears.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to assess the networker identity of your organization. It’s a product of your systems, policies, and workplace climate. You’ll discover ways to develop and support your employees as they connect, converse, and collaborate to create the new value on which your organization depends for future success.

Are you seeing the demise of command-and-control and the rise of the connected, collaborative workplace? It’s the next big advance in the evolution of organizations. Many people and organizations are heralding the coming of the Network-Oriented Workplace. In this book, we quote thinkers who are exploring it—Alex Pentland, Ben Waber, Rob Cross, Ron Burt, Adam Grant—and organizations that are sketching its broad outlines—The Conference Board, the Corporate Executive Board, McKinsey, IBM, and many others.

A Network-Oriented Workplace doesn’t happen automatically. You can’t buy it. You can’t mandate it. But when you tear down the barriers and build up the foundation and infrastructure, you can create the environment in which employees can build, enhance and strengthen their networks—individual networks from which your organization will realize substantial benefits.

And the Word Is…

Because of its historical connections with job-hunting, careering, and sales, the term “networking” may put people off. We’ve noticed, as we’ve talked with leaders in corporations, professional services firms, and government agencies, that some are substituting other terms for “networking,” like “partnering,” “horizontal integration,” “silo-smashing,” “relationship management,” “social acumen,” “connectivity,” “teamwork,” and even “collaboration.”

We see collaboration as the outcome of networking, not synonymous with it. Our definition has evolved over the two decades we’ve been teaching networking skills:

Networking is the deliberate and discretionary process of creating, cultivating, and capitalizing on trust-based, mutually beneficial relationships for individual and organizational success.

The Need for a Network-Oriented Workplace

“I am convinced we have the right strategy. I am convinced we have the right offerings. I am convinced we have the right people. But what keeps me awake at night is the ability of people in my organization to work together to deliver.” That’s what the CEO of a multinational telecommunications company in South Asia said.

As we talk with other C-suite leaders in companies across the globe, we hear the same frustrations about how their organizations fail to optimize their potential because their people fail to work together effectively. What’s happening in your organization? Are you satisfied with your people’s strategy execution, innovation, engagement, and competiveness?

THE FAILURE OF STRATEGY EXECUTION

In 2013, the Economist Intelligence Unit issued a report, “Why Good Strategies Fail: Lessons for the C-Suite.” The research queried 587 senior executives around the globe and found that 61 percent acknowledged that their firms struggle to bridge the gap between strategy formulation and its day-to-day implementation.

A May 2000 Harvard Business Review article, “Cracking the Code of Change,” puts the failure rate even higher. Authors Michael Beer and Nitin Nohria write, “Despite some individual successes… change remains difficult to pull off, and few companies manage the process as well as they would like. Most of their initiatives—installing new technology, downsizing, restructuring, or trying to change corporate culture—have had low success rates. The brutal fact is that about 70 percent of all change initiatives fail.”

What’s the reason for these abysmal statistics? In their 2010 book, Strategic Speed: Mobilize People, Accelerate Execution, authors Jocelyn Davis, Henry Frechette, and Edwin Boswell researched organizations around the world that were considered successful at speedy strategy execution. The researchers discovered that the “X-factor” that determined success was the attention their leaders paid, not to strategy development, process improvement, or installing new technologies, but to people.

The X-factor is the attention leaders pay to people.

THE STAGNATION OF INNOVATION

In a Business Week article, “CEOs Say Investing in Innovation Is Not Paying Off,” author Bernhard Warner says only 18 percent of CEOs are happy with their results; the other 82 percent are disappointed. What goes wrong?

You may have heard the empty box story. This classic tale also points to the people factor. Consumers complained about buying boxes of soap and finding them empty. To solve the problem, engineers were told to find a way to spot the empties among the boxes flowing along on the assembly line on their way to the shipping department. The assembly line workers watched the engineers working away. Nobody asked the workers for a solution. Over many months, the engineers developed an x-ray machine with high-resolution monitors crewed by two people to identify the empty boxes. The cost? Astronomical!

One day, as they waited for the new equipment to be installed, a worker found an industrial fan sitting unused in a storage closet. He brought it to the assembly line and switched it on. When the blast of air hit a box that was empty, it flew off the line. Problem solved.

“Innovation only occurs in a ‘sympathetic environment,’” say authors Jeff Mauzy and Richard Harriman in their book, Creativity, Inc.: Building an Inventive Organization. “The ideal creative climate nurtures intrinsic motivation, assures the safety necessary for curiosity, holds high expectations for creativity, and provides the support critical to evaluation.”

THE PROBLEM OF ENGAGEMENT

You’re probably painfully aware of the statistics. Gallup Inc.’s worldwide studies in 2013 covered 1.4 million workers in 34 countries. Only 13 percent of employees were “engaged”—psychologically committed to their jobs and organizations and likely to be making positive contributions. Some 63 percent were “not engaged”—lacking the motivation to invest their energies to achieve their organizations’ goals. And the second largest group of 25 percent were classified as “actively disengaged”—unhappy, unproductive, and likely to spread negativity.

Jack Welch, former CEO of General Electric, said, “There are only three measurements that tell you nearly everything you need to know about your organization’s overall performance: employee engagement, customer satisfaction, and cash flow.… It goes without saying that no company, small or large, can win over the long run without energized employees who believe in the mission and understand how to achieve it.”

One of our associates told us about an exercise he devised for a leadership workshop. He divided the participants in half. In a whisper, he told one group, “You are Renters” and the other, “You are Homeowners.” Both groups were given the same situations to respond to:

![]() A water stain has appeared on the kitchen ceiling.

A water stain has appeared on the kitchen ceiling.

![]() The paint on the exterior of the house is beginning to peel.

The paint on the exterior of the house is beginning to peel.

![]() Robberies in the area are on the increase and your next-door neighbor is the most recent victim.

Robberies in the area are on the increase and your next-door neighbor is the most recent victim.

The responses from the two groups were diametrically opposed. The Renters said they’d make a formal complaint to the landlord, withhold the rent until the problem was fixed, and leave the neighborhood. The Homeowners, on the other hand, said they’d fix the stain themselves, ask friends over to help paint the house one weekend, and talk to the neighbors about setting up a neighborhood watch group.

Sadly, the reality is that most people in organizations are “Renters.” They lack a feeling of ownership in the business. They are unengaged.

THE CHALLENGE OF COMPETITION

Competitiveness includes making the most of your resources. In a workshop in Sydney, we asked a group of leaders, “What does the lack of networking cost you?” An executive from a large bank jumped in and said, “I can answer that question for you with a specific number. We’ve just completed an internal audit to determine the costs of duplication of processes, based on various parts of the bank doing their own thing and not leveraging what someone else already has done. The cost of that duplication? $35 million!” What does the lack of networking competency cost your company?

Competitiveness also includes making the most of your human capital. Many organizations are asking a wide range of employees, not just the sales force, to bring in the business. The COO of an IT company in India said, “The people who are most intimate with the customer’s business are our project managers working on customers’ sites. They are absolutely in the best position to identify potential incremental business opportunities. Although we have asked and keep asking them to keep their eyes and ears open for business opportunities, nothing is happening. I have come to the realization that we need a minor revolution for them to really embrace the business development aspects of their job. Merely directing them to do this is not enough.”

Unfortunately, that COO’s experience is not unusual. People in what we’ve labeled “the quiet careers,” such as engineering, accounting, and IT, are particularly resistant to taking on a business development role. They often see “selling” as incompatible with their professional identity and lack the skills to uncover opportunities.

All of these areas of concern—strategy execution, innovation, engagement, and competitiveness—have something in common. All can be impacted by improving face-to-face networking on the part of employees.

Take another look at The Big Picture in Chapter 8 for an overview of how to achieve greater collaboration. As employees master The 8 Competencies, they learn how to teach trust, cultivate relationships, and build networks. They connect, they converse, and ultimately, they collaborate to contribute to the big business issues.

What’s Your Organization’s Networker Identity?

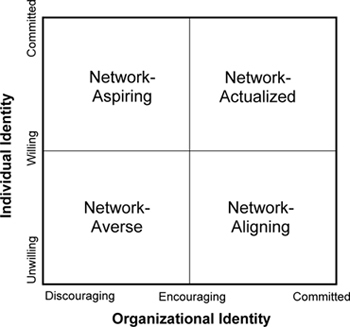

In Chapter 1, we explained the process individuals go through as they commit to a networker identity. Organizations also need to go through the process of finding their networker identity. Use the diagram to pinpoint where your organization is now and see the possibilities.

The horizontal axis on Figure 9–1 shows the continuum of attitudes your organization might hold toward networking. That continuum ranges from Discouraging through Encouraging to Committed.

In organizations that are Discouraging, leaders are unaware of the benefits strong employee networks can deliver. Leaders, still in a command-and-control mode, may seriously doubt whether internal and external networking are legitimate business activities. Leaders are uncomfortable with networking because they don’t feel they can control it. Policies and procedures act as barriers to networking, and it’s both disregarded and unrewarded.

FIGURE 9–1. What’s Your Network Identity?

In organizations that are Encouraging, leaders have discovered the value of employee networks, are removing barriers and disincentives, and are putting many support systems in place. Typically, these organizations have spent considerable money on technologies for connecting and collaborating. Overshadowed by these technologies, face-to-face networking may not yet be highly valued. Leaders may wrongly believe that employees have all the skills they need to network and collaborate and that simply asking them to put those skills to work will get results.

Leaders may wrongly believe that employees have networking skills.

In organizations that are Committed, leaders expect collaboration; act as role models for networking; remove barriers to connecting up, down, and across the organization; and revise policies and systems so they are “networking-friendly.” Once organizations have reached this level of commitment, they have aligned their environment with their intentions.

But intentions, infrastructure, and imperatives alone are not enough. When organizations call for collaboration without developing the skills and the networker identities of employees, their aspirations remain unrealized.

At the center of building a Network-Oriented Workplace is training. Leaders who want to reinforce the importance of face-to-face networking as a high-value business strategy recognize that building the capacity and competence of employees is essential. This training gives employees the specific skills and enterprise-wide focus necessary for their—and their organization’s—success.

On the vertical axis in Figure 9–1, you can see the continuum of employee attitudes, from Unwilling through Willing to Committed. This continuum reflects the attitudes of employees toward the value of face-to-face networking and reveals their beliefs about whether they personally can use networking to make a difference, not only for themselves, but also to benefit their organizations.

Employees who are Unwilling typically focus on tasks more than on relationships and have negative mindsets—for a host of reasons—toward networking. These employees see themselves as non-networkers. They may feel that networking conflicts with their image of themselves as professionals. Many classify themselves as shy or introverted and don’t realize that networking skills are competencies that they can learn.

Employees who are Willing recognize that networking could help them get their jobs done and advance their careers. As organizations demand more in the way of collaboration and business development from them, these employees decide that they need to get on board. They are ready to take on the role of networker, if only they knew how. Though open to the idea of networking, they haven’t yet felt comfortable and confident with the network-building process. They need the organizational acknowledgment and support that only you can give.

Employees who are Committed are convinced of the value of building trust-based relationships with people inside and outside their organizations. They know that networking is skill-based, not inborn and not limited by personality type. They are seeking ways to collaborate with others to improve everybody’s results. These employees believe that they could contribute more to their organization’s success. But the impact they can deliver is unrealized because the organizational environment doesn’t yet elicit their best.

Use the diagram to analyze where your organization and your employees are now. Are they:

![]() Network-Averse? You have unwilling, unskilled employees and an environment that discourages people from cultivating and capitalizing on networking.

Network-Averse? You have unwilling, unskilled employees and an environment that discourages people from cultivating and capitalizing on networking.

![]() Network-Aligning? Leaders are committed to the value of networking. Connecting technologies are ubiquitous, and policies and procedures are being revamped to support a networking culture. This is a fertile environment, but your employees are dragging their feet. Leaders may assume that employees lack motivation, but what they really lack is know-how and the opportunity to develop their network identities. Their resistance means that you don’t get the outcome you want when you say, “Collaborate.”

Network-Aligning? Leaders are committed to the value of networking. Connecting technologies are ubiquitous, and policies and procedures are being revamped to support a networking culture. This is a fertile environment, but your employees are dragging their feet. Leaders may assume that employees lack motivation, but what they really lack is know-how and the opportunity to develop their network identities. Their resistance means that you don’t get the outcome you want when you say, “Collaborate.”

![]() Network-Aspiring? Your employees are willing to believe in or have committed to the value of networking. They are eager to use networking to get their work done and to advance their careers, but are missing that wide-angle view that helps them see how to work on initiatives and goals beyond their own jobs. Since organizational policies are unfriendly, most networking is “under the radar.” It’s still an untapped resource for creating the kind of collaboration you need to excel.

Network-Aspiring? Your employees are willing to believe in or have committed to the value of networking. They are eager to use networking to get their work done and to advance their careers, but are missing that wide-angle view that helps them see how to work on initiatives and goals beyond their own jobs. Since organizational policies are unfriendly, most networking is “under the radar.” It’s still an untapped resource for creating the kind of collaboration you need to excel.

![]() Network-Actualized? When both the individuals and the organization commit to their networker identities and when employees are trained and organizational systems support networking, then the organization’s networking goals will be fully realized—and it will experience the growth and profitability that result when people collaborate to execute strategy, innovate, engage, and compete.

Network-Actualized? When both the individuals and the organization commit to their networker identities and when employees are trained and organizational systems support networking, then the organization’s networking goals will be fully realized—and it will experience the growth and profitability that result when people collaborate to execute strategy, innovate, engage, and compete.

So, how do you, a leader, help your organization become Network-Actualized? By creating connections, sparking conversations, and fostering collaboration you can establish the conditions that are necessary for the Network-Oriented Workplace. Figure 9–2, Actions for Leaders, provides the outline for the rest of the chapter.

FIGURE 9–2. Actions for Leaders

Create Connections

What can happen when you connect the right people? Can you make face-to-face encounters more likely? Do people have time to connect? The answers to these questions reveal the actions you can take.

BRING STAKEHOLDERS TOGETHER

When Contacts Count polled 100 human resources managers, 91 said they saw a need to strategically manage the creation, maintenance, and growth of social capital in their organizations, yet 81 said their organizations did not have a well-defined, enterprise-wide strategy for developing the social capital of employees.

You can be the catalyst for creating that strategy. Bring together everyone who has a stake in developing the networking capabilities of employees, everyone whose initiatives will benefit as employees become more proficient and productive at networking. As you envision your team, think about including people from training and development, talent management, business development, sales, and marketing. Consider inviting people who manage innovation efforts, leadership development programs, orientation, employee resource groups, mentoring and diversity programs, and internal face-to-face or online networks. Who else do you need to get buy-in from? Who would be good champions? Whose expertise, such as corporate communications, do you need? The group that you have pulled together will be your KeyNet as you set your strategy and make your to-do list.

Be the catalyst for an enterprise-wide strategy for developing the social capital of employees.

What will you say as you recruit people? What will the agenda for your first meeting need to include? Your KeyNet will be an example of the kind of collaboration that you want to encourage in your organization. Will coming together to work on ways to support networking be a simple task? That will depend on the attitude your organization currently has toward networking. If your organization is Discouraging, you may find the going tough; if it’s Encouraging or Committed, you should have an easier time of it. The amount of time you’ll need to spend will also depend on where you start. Think of this project as ongoing.

SYNC THE SYSTEMS

How will you align the infrastructure with your commitment to a networked, collaborative culture? This question will put lots of items on the KeyNet’s agenda. Do we need to change our hiring policies, so that we attract people who already have a collaborative mindset? How about job descriptions and performance evaluations? Don’t they need to mention networking? Do we need to adjust how people are compensated? Use your KeyNet’s expertise to surface all of the areas you’ll need to consider.

MAKE SPACE

In the book Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson, Apple’s cofounder says, “There’s a temptation in our networked age to think that ideas can be developed by email and iChat.… That’s crazy. Creativity comes from spontaneous meetings, from random discussions. You run into someone, you ask what they’re doing, you say ‘wow,’ and soon you’re cooking up all sorts of ideas.”

Creating the physical environment in which these spontaneous meetings occur is something many organizations are already doing.

In February 2013, Yahoo’s head of human resources Jackie Rees sent a memo to staff who had been working from home. It said in part, “To become the absolute best place to work, communication and collaboration will be important, so we need to be working side-by-side. That is why it is critical that we are all present in our offices. Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings. Speed and quality are often sacrificed when we work from home. We need to be one Yahoo, and that starts with physically being together.” Working from home was cancelled.

What else can you do bring employees together?

How can your physical plant make connections happen?

Google’s Bay View campus in California was designed to maximize what real estate head David Radcliffe calls, “casual collisions of the workforce.” In an article in Vanity Fair magazine, Radcliffe says, “You can’t schedule innovation. We want to create opportunities for people to have ideas and be able to turn to others right there and say, ‘What do you think of this?’”

And what if your employees were encouraged to run into people outside the organization?

“Collisions” are also part of the vocabulary at Zappos, the online store. CEO Tony Hseih believes in setting the stage for casual contact. At the Las Vegas office, three entrances were blocked, making sure that employees bumped into each other at the one remaining. It is evident that the company prioritizes collisions over convenience. Hsieh also wanted his people to collide with businesspeople in the neighborhood. One of the closed entrances was at the end of the skywalk from the parking garage into the building. Employees were rerouted to sidewalks, a move that increased their chances for random encounters with people in the wider community. Hseih advises, “…meet lots of different people without trying to extract value from them. You don’t need to connect the dots right away. But if you think about each person as a new dot on your canvas, over time, you’ll see the full picture.”

In hierarchical organizations, access to others was restricted, resulting in the walled-off departments or functions known as “silos” or “stovepipes.” What can your KeyNet do to eliminate such barriers and promote connecting? How can you arrange your space so people will connect?

TAKE TIME

It’s one thing to make the physical space conducive to connections, but do people have the time to stop and talk or will they pass on by? We call these times ChoicePoints—moments when people decide whether or not to interact. If people choose not to interact, what’s to blame? Billable hours are the bugaboo in many firms. Productivity goals and tight deadlines hurry employees along. To take the time to connect, people will have to receive repeated reassurance that networking is working. In the Harvard Business Review article, “IDEO’s Culture of Helping,” the authors point out that a certain amount of “slack” in employees’ schedules pays off and allows people to engage in unplanned ways.

Will employees stop and talk or will they pass on by?

How can you provide time for networking? Can you increase the number of social events, volunteer projects, and sports activities to induce connections? And can you designate networking time at corporate gatherings?

Spark Conversation

As a leader, what can you do to refocus on the definition, raise the quality, and influence the content of conversation?

TALK “WITH” NOT “AT”

By definition, conversation is two-way. Moving from “command and control” to “connect and collaborate” means moving from monologues to dialogues. One kind of dialogue you as a leader can promote is the top-to-bottom kind of conversation: from management to employees.

Jack Stahl, former CEO of Revlon, Inc., and author of Lessons on Leadership, writes:

A good leader spends significant time meeting and talking with people up, down, and across their organization. By being visible in this way, the leader is positioned to ask questions of his or her people to learn about their challenges, where they are struggling and any barriers to success. The leader can then provide coaching to those individuals and has the ability to help solve any systemic roadblocks that can prevent success for the larger organ ization. I found I can talk to over one hundred people per week in one-on-one conversations simply by taking advantage of every opportunity to talk with people, before and after meetings, in the hallways, to and from the offices, and even in elevator conversations.

Note that Stahl’s approach involves more than telling; it involves asking, listening, and coaching.

In their book, Talk, Inc., Boris Groysberg and Michael Slind write, “A new source of organizational power has come to the fore. Our term for that power source is organizational conversation. Instead of handing down commands or imposing formal controls, many leaders today are interacting with their workforce in ways that call to mind an ordinary conversation between two people.” Keeping those ideas in mind will help you have more valuable give-and-take conversations with employees.

Another kind of dialogue involves employees talking with one another. Once you’ve created the space and time for connection, you can home in on the quality of these exchanges.

IMPROVE THE QUALITY

Conversation in an organization improves as employees gain skill in asking questions and listening.

The bar is also raised when leaders “are fostering and facilitating conversation-like practices throughout their company—practices that enable a company to achieve higher degrees of trust, improved operational efficiency, greater motivation and commitment among employees, and better coordination between top-level strategy and frontline execution,” say Groysberg and Slind in Talk, Inc. “The power of organizational conversation isn’t the kind of power that manifests itself as control over a person or a process. Rather, it’s the kind of power that makes a person or a process go. It’s energy, in other words. It’s fuel. In organizational terms, conversation is what keeps the engine of value creation firing on all cylinders.”

In 1995, Juanita Brown and David Isaacs stumbled upon a conversation process. They went on to develop what’s now called World Café. Organizations around the world use this free process. Yours can adopt it, too. See the website at www.theworldcafe.com for instructions.

Peter Senge of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Sloan School of Management and author of The Fifth Discipline provides a testimonial: “World Café conversations are the most reliable way I have yet encountered for all of us to tap into collective creating.… I have been repeatedly struck by the ease of beginning a World Café–style dialogue—how readily people shift into heartfelt and engaging conversation.”

How will you promote high-quality conversations?

TELL THE STORY

In the command-and-control environment, people tried to control the messages being sent from the organization to the outside world. Now, with the variety of communication technologies available to everyone, a cacophony of voices with a jumble of opinions and a mishmash of information—and misinformation—emanates from people inside your organization to those outside. There’s no way to control that flow, but you can educate employees. One of the ways employees can impact your big issues is to tell your story—if they’ve learned it. The employee might be talking to potential clients or customers at a civic association meeting or to a neighbor who serves on the city council over the back fence. When people ask that employee, “What’s new at YourCorp?” what’s he going to say?

You can’t control information flow, but you can educate employees.

When we quizzed a group of employees about 10 of their firm’s biggest achievements and latest news (taken directly from the firm’s website), we found that people were aware of—and therefore could talk about—only 30 percent of their own company’s successes.

In Talk, Inc., the authors quote Andy Burris, VP of Corporate Marketing and Communications at McKesson Corporation. He says, “Ultimately, we would like to create a thirty-five thousand employee virtual sales force.… We aim to boost the level of business literacy throughout the organization. How do we make sure that someone in accounts payable knows enough to be dangerous?… If that person happens to be at a backyard barbecue with a neighbor who happens to be a physician, we want that person to know enough about what we offer to physician’s practices that he or she can engage in meaningful conversation.”

How can you increase the business literacy of your employees? And do you act as a role model, habitually finding and telling stories about your organization? Stories have staying power. They stick in the listeners’ minds. They create a picture that can attract the best employees and clients. In today’s organizations, storytelling is a skill everyone needs to master.

INSIST ON BRINGBACK

If you could look down on your organization from on high, what would the information flow look like? You’ve learned how you can influence the quality and accuracy of information flowing outward. How about increasing the inward flow of valuable business intelligence? We call that “BringBack.” In command-and-control organizations, the battlements not only keep information from leaving, they also prevent information from entering. In the best companies, employees know that part of their role is to gather ideas from the outside world and give those ideas to their colleagues inside. Every day, legions of employees go to conferences, professional association meetings, civic events, and many other outside activities—usually at their organization’s expense. How much money are you spending? What are you getting in return?

BringBack is the inward flow of valuable business intelligence.

In a 2013 Associations Now magazine article, “Intelligence by Design,” author Kristin Clarke writes:

The idea that intelligence gathering is everyone’s business has infiltrated every staff level at the Consumer Electronics Association (CEA).… The culture was purposefully put in place by CEO Gary Shapiro, who has created what may be one of the most organized, robust internal intelligence-gathering and analysis systems within the association community.

“If we’re investing in having one of our employees travel, for instance, they know they’re expected to go way beyond whatever their single purpose in going is,” Shapiro says. “They always have a dual purpose—to gather intelligence on behalf of the association, to see how [something] is done elsewhere and come back and report on it.” Sales staff in particular must share comprehensive written reports about what they’ve seen and heard which CEA summarizes and circulates widely across departments.

How can you significantly increase your organization’s BringBack, so that you get a better ROI from networking and professional development events?

Foster Collaboration

Once you’ve made connections happen and raised conversation to the next level, you’re ready for the final steps to collaboration: Paint the vision, invite employees to join in, and keep an eye on the progress.

KNOW YOUR LIMITS

You’re not in command-and-control mode any more. You can’t manage your employees’ networks. In recent literature about collaborative and connected organizations tapping into the power of networks, there’s great confusion about how leaders relate to these networks. We’ve seen other authors imply that leaders can and should be much more in control of the individual employee’s networks than is desirable or even possible. Can leaders really “help employees develop and sustain” their networks? Can leaders really “align and direct” employee networks? Can leaders really “connect their employees to the right collaborators?” Should leaders really “remove people from” employee networks or “appoint network leaders?”

The answer to these questions is a resounding “No!” Each employee will manage his or her own networks. The minute you interfere in any of those ways, you turn networking into a job assignment. If, however, you provide training in trust-building and network-building skills, employees will know how to configure and use their networks to contribute the most to the organization. Of course, some people are going to be better at networking than other people—even after training—so do feel free to coach and mentor.

ANSWER “WHY?” AND “WHAT?”

Employees have two big questions: “Why should we collaborate?” and “Exactly what does collaboration look like?”

Simon Sinek, author of Start with the Why and popular TED Talk speaker, puts forward a very compelling argument that the most inspiring leaders, those that are able to get people to act towards achieving goals, start by answering the “Why?” question.

Coming up with the answer to “Why do we need to collaborate?” is part of your role as a leader. The more you can dramatize and illustrate the “Why,” the more you’ll be able to inspire your employees to action. You also might want to include a vivid description of the pain that can ensue when people don’t collaborate. A huge and compelling example comes from the investigations after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Investigators pointed a finger at the U.S. intelligence agencies for failing to collaborate and share information as one reason the attacks succeeded. The Australian bank executive revealing the $35 million cost of duplication is another supersize example. Don’t rely just on examples from other organizations; show employees how collaboration—or the lack of it—will impact or has impacted your own organization. Your goal: Make sure employees “see” the benefits of collaboration clearly and “feel” the pain that absence of collaboration could bring. Answering “Why?” should give people a line of sight from what they are doing to what your organization is trying to achieve.

Dramatize and illustrate the “Why?”

1. Why collaborate? To increase competitiveness. It’s Monday morning. The mood is somber. The partners of a mid-sized accounting firm listen to a report on the grim quarterly results. All statistics point to missed targets and another decline in revenues. They can no longer accept the trend as a temporary aberration. Something needs to change. How are they going to bring in the business? The group is asked for ideas. They give only rationalizations: “The economy is sluggish.” “Our best clients are cutting back.” They need new solutions… game changers… bold, courageous moves.

2. Why collaborate? To execute strategy. Sam, the project delivery manager in IT at a major bank, talks with his wife about the latest restructuring in the division. “It feels a bit like leaving New York on a Boeing 747 and having to rebuild the aircraft mid-flight and touchdown in London without losing any time,” he says, shaking his head. To reduce costs, Sam has been told to lay off 60 percent of his U.S. employees and offshore their work to software engineers in India.

“How am I going to manage this change and still deliver the project by March?” Sam worries aloud. “The remaining people are struggling with their emotions. It’s hard for them to see their friends go out the door. Not only that, they are going to have to work a lot harder as we go through this transition. And I’ll be managing people I can’t see, have never met, don’t know the capabilities of, and who are in a different time zone and from a different culture.” “So what are you going to do, Sam?” asks his wife. “I don’t know,” he says. “All I know is that my success will be based on how I execute this change and still deliver the project on time. Be prepared for me to be home a lot less.”

3. Why collaborate? To innovate. At lunch in the cafeteria, a group of colleagues talks about the company’s new product, 4TUNE. The marketing team’s announcement enthusiastically promises that “this new game console will change the world,” as anyone can use it to produce studio-quality music at home. Piggybacking on the popularity of music reality TV in Asia, the company is betting everything on a successful launch of 4TUNE there.

“Why did they keep this a secret for so long?” asks Jiro. “Anyone who has ever been to China will know that 4TUNE is destined to fail.” “It’s probably because the product development people don’t expect anyone outside their closed circle to have an innovative idea in their brain,” laughed Susan. “Well, I’m not going to say anything now. It’s too late for that,” chimed in Garima. “They obviously don’t value the opinions of others in this company, so why bother?”

Tony listens with a puzzled look on his face. “You all are crazy. I think 4TUNE is very cool.” Jiro responds, “4TUNE is indeed a cool piece of equipment, Tony. It’s not the machine we objecting to; it’s the name.” Still puzzled, Tony says, “What do you mean?” “Well” says Jiro, “In China and in other Asian countries, the number ‘four’ is an inauspicious number. In fact, many buildings don’t have a fourth floor… and if they do, it’s usually vacant. People avoid using four, because it sounds like the word for death. That number in the name will stop people from buying the product.”

4. Why collaborate? To engage people. The division head of a large financial services firm is pleased when Charlie sticks his head in the door and asks, “Have you got a minute?” He’s one of her young and eager rising stars. He always has something valuable to share and always “tells it like it is.” He sits down and slides a memo across her desk. She skims the top line: “It’s with deep regret.…” Charlie says, “Bad news, I’m afraid. I am handing in my resignation. I’ve accepted a similar role with MetroBank.” The division head is shocked. “Why Charlie?” she asks, almost pleading. He explains, “Look, I’m tired of begging for cooperation. I have trouble getting anything done. I want to work in an environment where there’s more collaboration and camaraderie.”

Answering the question “What does collaboration look like?” is just as important as explaining why collaboration is vital. There’s no point in asking people to collaborate if they don’t know exactly what behaviors that entails.

Use these three ways to highlight what collaboration really looks like.

1. Find examples in your own organization, no matter how small or local they might be. As you shine the spotlight on these efforts, you encourage others, even in different work areas, to use the same methods.

2. Find examples in your industry. Research association and trade publications to find out how others collaborate, so that you can publicize those ideas to people in your organization. Get in touch with successful collaborators and interview them to get tips. You could even bring in these people to talk at employee meetings.

3. Find examples through people in your ProNet. When Sondra went to her alumni meeting, she met Leon. Although she was in banking and he was in healthcare, she found that he had a wealth of good ideas for initiating more collaborative processes, especially when people were still learning how to build trust cross-functionally.

To show what collaboration is, tell the stories about how people are coming together to create new value: how they are saving the day, solving the problem, or serving the client. The collaborative organization must have a compelling collaborative vision.

ELICIT BUY-IN

Employees may understand the benefits and may have been trained in the skills, but you’ll still need to get their buy-in. Note that the word “discretionary” appears in our definition of networking.

More than 30 years ago, Daniel Yankelovich and John Immerwahr, in their book Putting the Work Ethic to Work, described discretionary effort and its impact on organizational success. They defined it as the amount of effort individuals expend over and above the minimum they need to do to keep their jobs. Giving discretionary effort is a choice employees make. It can’t be mandated by the organization. Even though networking may appear on people’s job descriptions and may figure in their performance evaluations, it’s still discretionary. Individual employees will decide, every day, whether they will take advantage of a ChoicePoint and stop and have a conversation in the hallway, for example. Leaders have been trying to tap into this discretionary effort for many decades. The 63 percent of employees who are “not engaged” are not exerting much discretionary effort.

Networking is a discretionary act.

A Network-Oriented Workplace is an environment in which people will choose to exert extra effort to share information, resources, support, and access to intentionally create new value with others inside and outside the organization. Why? It’s a case of “riding the horse the way it’s going.” People are social animals; they build relationships. By training and inspiring them to do that better and more often, we help them take off at a gallop. It’s easier to elicit incremental improvement than wholesale change.

MONITOR THE PROGRESS

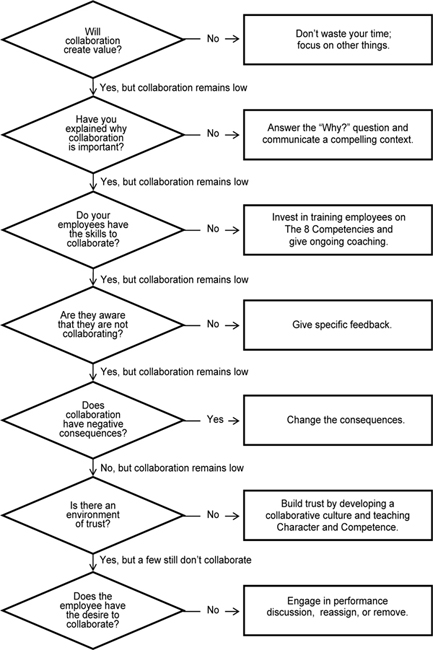

As you’re fostering a collaborative environment, you’ll want to check on the progress. Figure 9–3, Getting to Collaboration, is a diagnostic flow chart to help you consider why collaboration might be stalled and to suggest actions you could take to get things moving.

Your KeyNet will find it helpful to ask these questions:

![]() Will collaboration create value? If the whole organization is committed to the Network-Oriented Workplace, the answer must be “yes.” But that doesn’t mean that every effort or task must involve collaboration. It’s a tool to be used judiciously. Sometimes getting people to collaborate diminishes value by increasing costs and slowing down progress. If there is no value created, then don’t waste your time. However, if there’s evidence that value could be created by collaboration but collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

Will collaboration create value? If the whole organization is committed to the Network-Oriented Workplace, the answer must be “yes.” But that doesn’t mean that every effort or task must involve collaboration. It’s a tool to be used judiciously. Sometimes getting people to collaborate diminishes value by increasing costs and slowing down progress. If there is no value created, then don’t waste your time. However, if there’s evidence that value could be created by collaboration but collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

![]() Have you explained why collaboration is important? If you’ve answered the “Why?” question effectively and showed how it fits (created the context) but collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

Have you explained why collaboration is important? If you’ve answered the “Why?” question effectively and showed how it fits (created the context) but collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

![]() Do your employees have the skills to collaborate? If you have invested in training and coaching your people and they’ve reached a high level of competency but collaboration is still not happening, then consider the next question.

Do your employees have the skills to collaborate? If you have invested in training and coaching your people and they’ve reached a high level of competency but collaboration is still not happening, then consider the next question.

![]() Are they aware that they are not collaborating? Blind spots exist for both individuals and groups. As a leader, you can provide feedback to them, so that they are aware of their behavior. If you’ve provided feedback and collaboration is still low, consider the next question.

Are they aware that they are not collaborating? Blind spots exist for both individuals and groups. As a leader, you can provide feedback to them, so that they are aware of their behavior. If you’ve provided feedback and collaboration is still low, consider the next question.

![]() Does collaboration have negative consequences? Sometimes there are hidden downsides to collaborating. You’ll need to discover what they might be and eliminate them. If there are no negative consequences and collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

Does collaboration have negative consequences? Sometimes there are hidden downsides to collaborating. You’ll need to discover what they might be and eliminate them. If there are no negative consequences and collaboration remains low, then consider the next question.

![]() Is there an environment of trust? Trust is necessary for employee networks to develop to their full potential. Trust between employees can be destroyed by certain management actions, like downsizing, which pits employee against employee. To develop a networking culture means that not only do employees have the skills to teach and learn about each other’s Character and Competence, but also that the environment doesn’t value competition over collaboration. If there has been no disruption of trust and if employees have trust-building skills, then consider the next question.

Is there an environment of trust? Trust is necessary for employee networks to develop to their full potential. Trust between employees can be destroyed by certain management actions, like downsizing, which pits employee against employee. To develop a networking culture means that not only do employees have the skills to teach and learn about each other’s Character and Competence, but also that the environment doesn’t value competition over collaboration. If there has been no disruption of trust and if employees have trust-building skills, then consider the next question.

![]() Does the employee have the desire to collaborate? At the end of the day, you can create all the conditions for collaboration, and you may still find people who are resistant. Reassign them into jobs that demand less or no collaboration, give one-on-one performance coaching, or remove them from the organization.

Does the employee have the desire to collaborate? At the end of the day, you can create all the conditions for collaboration, and you may still find people who are resistant. Reassign them into jobs that demand less or no collaboration, give one-on-one performance coaching, or remove them from the organization.

As you move forward, continue to monitor and measure the impact of collaboration. Be sure to share success stories with employees to keep the enthusiasm high.

Your role as you take the lead in developing and supporting networking in your company is a big one. Your actions will include—but aren’t limited to—the ones listed here. You’ll find, we’re sure, additional ways to create connections, spark conversations, and foster collaboration.

Organizations are floundering as the command-and-control mindset of the past breaks apart. Many are struggling to pull together a comprehensive view of managing in the new hyperconnected and collaborative workplace.

In 1960, management guru Douglas McGregor wrote in his groundbreaking book, The Human Side of Enterprise, “Fads will come and go. The fundamental fact of man’s capacity to collaborate with his fellows in the face-to-face group will survive the fads and one day be recognized. Then, and only then, will management discover how seriously it has underestimated the true potential of its human resources.”

Half a century later, you can help to realize this human potential through your strategic connections.