CHAPTER 4

Visual Design

From concept to finished art, designers must always ask themselves: do the visuals being developed work with the look and feel of the game? Visuals refer to the characters, props, environments, and interfaces built for the project.

Occasionally, an existing character is the starting point for a game, such as Marvel Comics' Thor or Luke Skywalker from the Star Wars sagas. An entire cavalcade of characters and exotic worlds had already been created for the Lord of the Rings trilogy. Those examples are well thought out, deeply developed entities that have their personalities and abilities clearly mapped. In such situations, the game and its gameplay usually develop around them.

In other types of design, the concept for the gameplay comes first, and then characters, environments, and so on are developed to match what the look and feel should be. Either way, the end result should be the same: a good balance between art and gameplay, to appeal to the demographic for which the project is being designed and to be appropriate for the gameplay style. All the elements have to work together to ensure that the final product is compelling and fun.

- Developing concept art

- Previsualization

Developing Concept Art

Coming up with the concepts for innovative characters, props, environments, and interfaces is an important first step for beginning an original game design. These initial sketches help to carve out what the world will look like, where play will take place, and how the gamer will be able to interact with that world through the interfaces and avatars. Beyond the written word, where interpretation can be subject to the reader's own experience and imagination, actually seeing the first passes on art quickly gets the whole team on the same page.

According to game designer Daniel Cook in “Evolutionary Design” (in Game Design, www.gamedev.net), “The most common mistake of modern games is that they mistake setting for game design. A great plot does not make a great game. Nor does a great player model or animation engine. These merely provide contextual support for the game's reward system. If the rest of the game design is broken, a multi-million dollar investment in setting will still fail to produce an enjoyable game.”

By now it's clear how important gameplay is, yet it's also highly subjective. Designers are faced with the task of building characters and other visual elements that will enhance the elusive quality of gameplay.

Many designers rely heavily on what has already been produced, claiming that visuals or gameplay that don't have a degree of familiarity won't appeal to gamers. Taking what has already been done but adding a twist to it, adding a little fresh design, tends to be the norm with many current games.

Being aware of this trend affects how concept work is approached in this industry. You'll be challenged to come up with designs that meet the needs of the project and are new and fresh, while also having a degree of familiarity.

Where Do You Start?

To begin the process of coming up with the concept art, you need to know some basic information:

- Who is the game being designed for (demographic)?

- What is the gameplay style (discussed at length in Chapter 2, “Gameplay Styles”)?

In addition to those two points, you should work with as much information as is available: backstory (or lore), script, goals of the game, and platform. (Platforms, or systems used to play games, are described in Chapter 10, “Designing Games for Varied Distribution”).

Based on that information, you can make decisions regarding the look. Will it be cartoony, realistic, bright, somber, complicated, or intense?

It isn't uncommon for the concept artist to prepare three different preliminary versions of any visual that can work with the look and feel of the project. Three examples provide enough variety that the team can choose which one is going in the best direction for the needs of the project, or pick elements from two or all three that can be used to make another pass at the concept work. Starting with at least three variations also helps prevent the project from getting locked down too quickly with a specific look.

The concept work can be pencil sketches, sculptures, 3D models, or any other media that can convey the look and feel of the visual to people on the team. The concept artist usually includes color as well, because that can be such an important component of how the visual fits in with the game's look and feel. Color choices are often made based on how photoreal or stylized the game will look, so including them during the concept phase is a significant step.

Designer and animator Richard Sternberg started with this information for the game Frozen, created by Star Mountain Studios:

Backstory (Lore) The story places a novice reporter, Samantha (Sam) Bloodworth, in Antarctica. Sam must reach safety after a volcano has exploded, stranding her on the remains of a shattered ice shelf.

Demographic Everyone (no specific demographic).

Gameplay Style Puzzle with a strong storyline.

Sternberg began with a modified Poser model to sketch in the initial design for Samantha. Figure 4.1 shows the original concept for Sam: a loose pencil sketch (left); the vector art adapted from that sketch, for cleaner line work (center); and the final color version, which was painted in Photoshop (right).

FIGURE 4.1 Development of the character Sam from initial pencil sketch to line art (created as vector work in Flash) to the final version, painted in Photoshop

For the gameplay, Sam needed to be adventurous and athletic, on the young side, and dressed for the brutal weather that is prevalent in Antarctica, hence the dark glasses and parka (seen in the final version at right in Figure 4.1). There is enough realistic detail to help get across quickly that she is in a cold and dangerous environment; however, the bright colors and her energetic look work well with this being a lighthearted, fast-paced game.

The software program Poser allows artists to pose a 3D model of a human or a wide variety of animals in various action positions as a drawing reference.

Sam was designed as a 2D character and subsequently animated in Flash. The game Frozen is Flash based.

“We used to spend so much of our time on gameplay and today's games seem to put too much emphasis on graphics and sound. It's the game that makes a game fun, sometimes they forget that.”

This comment by Larry Kaplan, one of the cofounders of Activision, reinforces the importance of balance between designing the visuals and the gameplay.

A good example of how this lack of balance can affect the success of a game can be found with PlayStation's Rise to Honor, which starred Jet Li (and no offense to Jet, because this author is a huge fan of his films!). The game captured the sweeping cinematic look and feel of an intense action film; however, the gameplay was repetitive and boring.

Looking at different platforms is a useful approach to get another perspective on design work for games. The platform is the system used to play the game. Frozen was designed for PCs (home computers), which tend to use good-sized monitors. The amount of real estate available allows for more graphics than something designed for a smaller, handheld device.

A boutique studio based in the UK, Mobile Pie (www.mobilepie.com/) creates original games (own-IP as well as licensed) for mobile platforms. The company designs and creates almost everything in-house, including characters, environments, and user interfaces.

According to Creative Director Will Luton, the artists at Mobile Pie take a very pragmatic approach to designing assets for games, going from the macro to the micro. To begin the design process, Mobile Pie answers the following questions:

- What is the goal of the game?

- What is the gameplay style?

- Who is it for (demographic)?

- What is the theme?

Assets are characters, props, environments, and interfaces.

Your demographic, or audience, helps define the game's style. Understanding demographics means understanding the audience's age group, gender, and other key characteristics.

When the answers to these questions are clear, Mobile Pie generates an asset list and uses that to help prioritize how to segue the project into production. The asset list contains the number and types of characters, props, and other elements they may need to create. As color is worked into the art, reference images are used to help generate a palette.

KEEP THE DEMOGRAPHIC IN MIND AS YOU DESIGN

In Game Over, Nina Huntemann notes, “You know what's really exciting about video games is you don't just interact with the game physically—you're not just moving your hand on a joystick, but you're asked to interact with the game psychologically and emotionally as well. You're not just watching the characters on screen; you're becoming those characters.”

When designing art for characters, keep in mind that the gamer is going to use your design to interact with the game itself, so that design needs to work for the demographic and gameplay style.

Theme refers to the setting or ambience.

Reference images can include a color palette or a look from a similar project.

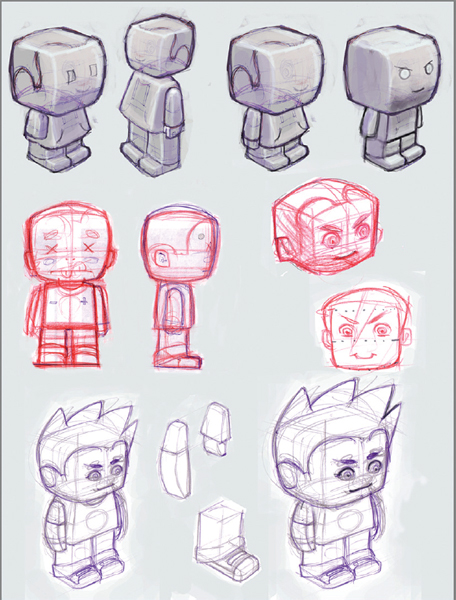

The main thing to keep in mind in the early stages of developing the concept art is that this process is flexible. The goal is to keep things loose with room for change if it's needed, while giving enough detail to give a clear indication of what the final character can look like. Figure 4.2 shows an example of Mobile Pie's process. The character is roughed in with a pencil sketch.

FIGURE 4.2 At this early stage of development, the concept art is roughed in as a pencil sketch, which helps keep things flexible.

While working on the concept stage of developing characters (or props, environments, or interfaces), keeping the work loose in the beginning is paramount. Don't try to settle too quickly on the finished look. The art director may still want substantial variations to take place. Nothing is more frustrating than investing an enormous amount of time in creating really finished-looking art during this early phase, only to have the client or art director review the project and decide that it isn't what they want. This type of error can lead to burnout.

Working smart—doing the upfront assessment of what the character should look like based on the macro-to-micro concept—is an excellent way to go. After creating a rough sketch, Mobile Pie takes it into a digital paint package or a 3D program, and a more finished product begins to take shape. This is a typical workflow for any game-design studio. Figure 4.3 shows an early render built in 3ds Max.

Photoshop and Illustrator are examples of digital paint programs.

FIGURE 4.3 This image shows the final 3D version of the character.

One of the final stages of Mobile Pie's concept phase is mocking up screens to show all the elements in place. Because all the elements created for the project need to work together, you should generate mocked screens as soon as possible to see how well the art meshes with the gameplay. Figure 4.4 is an example of one of these mockups, created in Photoshop, showing characters and background pieces together.

FIGURE 4.4 Mockups pull together concept work in all phases of design, from rough pencil sketches to more finished work, and help show the interplay of the art with the gameplay.

After going through the concept phases of designing assets for the game, a pipeline is created to help determine who will do what when it comes to developing the images further. The pipeline is examined in greater depth in Chapter 9, “Game Production Pipelines”; however, it's good to begin to get a rudimentary understanding of this workflow now.

The pipeline for any project is the hierarchy of the workflow.

The pipeline helps the creative director and artists focus their efforts where they're needed most. There is a lot of work to send back and forth between client and developer, so Mobile Pie, like many organizations, finds ways to effectively communicate not only the images but also the comments related to them. During the critical phase of creating final art, Mobile Pie uses a private blog that hosts comments along with the images to facilitate communication.

Methods for communication between team members or the client and developer vary from studio to studio. Some companies maintain a private website with a login feature, where work is posted and team members or the client can log in to view work in progress. Others use the blogging system, FTP sites, or simply email work back and forth. There are also services that allow users to send large files, such as MailBigFile and Dropbox. Dropbox has a drag-and-drop feature: users can drag files into their dropbox and share access with others who can pull those files onto their own computer systems as needed.

Inspiration and Originality

Many times, I have counseled students to avoid drawing from memory. Artists or students occasionally draw what they think something should look like (how they remember it) instead of what it actually looks like. It's also too common for artists new to concept work to simply create a variation of a character they're familiar with from another game or similar medium, such as animation or a comic book.

The point is that in order to create a new type of character, it's important to reach outside of your current frame of reference and strive for something new and original. How many times have you sat down to draw, say, a house or a dog, and had it always be the same type of house or dog?

Designing Original Characters

It's understandable to have a fear of coming up with something new. It's comfortable to keep drawing the same things over and over, kind of like doing a loving portrait of an old friend. But put yourself in the shoes of gamers who will immerse themselves in the world of the game you're creating and interact with the characters you're designing. You sit down to play, install a new game, marvel at the splash art, and are swept away by the intro music and stunning opening cinematics. Then you become entranced and amazed at some remarkable new character you've never seen before. And the best part is, you get to interact with this character.

Having well-designed characters—their appearance and also how they move, sound, and interact with other elements of the game—lends itself to making the game not only playable, but re-playable, and that is one of the components of successful gameplay.

Where to Find Inspiration for Original Designs

Sometimes, though, your task may be to create an orc or elf or dragon or knight—a type of character that has been used frequently in games. Even in these cases, don't limit yourself by falling back on doing variations of what others have done. Where do you go for inspiration if your only source for ideas might be the last game you played?

The world. No: the universe all around you!

There is so much from which to derive inspiration that you'll do yourself a disservice if you don't explore other sources of motivation. You can

- Observe microscopic life that you can only see under a microscope. Some great beasties live in a petri dish.

- Look in the sky, marvel at the beautiful cloud formations, and imagine what those might look like animated.

- Leaf through a book about strange and unusual plant or animal life (make sure you select a book with lots of photos).

- Listen to a piece of music that inspires you.

- Watch the sublime movements of a dancer.

Inspiration is all around you.

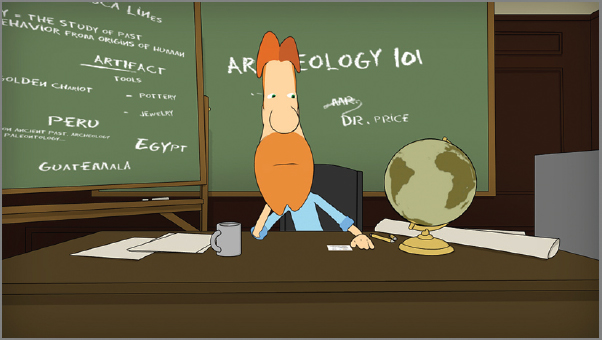

You may also derive stimulation from how other creative people have worked at creating original work. Franklin Sterling III, an artist and designer living in Los Angeles, creates 2D/3D work for books and the simulation industry (we discussed simulation in gameplay styles in Chapter 2). Sterling is an avid fan of Matt Groening, the creator of Life in Hell and The Simpsons, and derives inspiration from the simple yet acerbic quality of Groening's work. Figure 4.5 shows a character named Weldon Price, whom Sterling created for an animated series of shorts titled Out There that is being adapted to a side-scrolling Flash adventure game by the same name.

FIGURE 4.5 Weldon Price is a character whose inspiration came from the unique storyline for Out There.

Out There is a funny, lighthearted adventure about mild-mannered Price, who travels the world with his uncle. He literally falls into one escapade after another from the dilapidated balloon they travel in. As quaint, sweet, and nonthreatening as Weldon appears, his origins were strongly influenced by the conceptual methods H. R. Giger used while creating his award-winning monster for the film Alien.

Giger's frightening creation was built on a design from an earlier painting he had done called Necronom IV and was further designed based on studies he made of old Rolls Royce parts, rib bones, and snake vertebrae.

What inspired Sterling about that process was how Giger was able to study shapes and create such a fantastic creature. So what shape did Sterling settle on?

A peanut.

Sterling felt it was an odd shape and might work, so he used that shape to design Weldon Price.

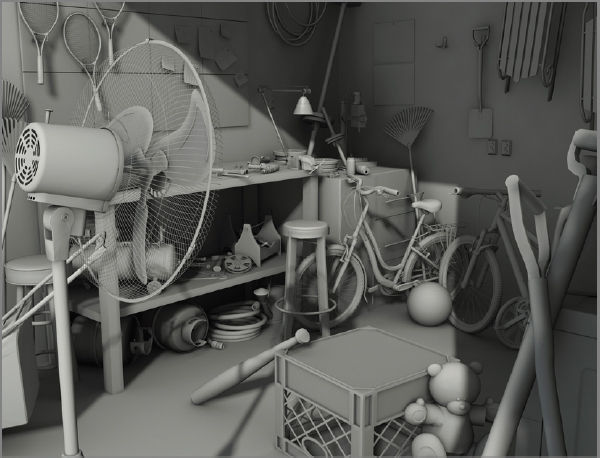

Not all of Sterling's work is based on such simple concepts. In a project called The Red Bedspread that he is working on with fellow writer Karen Soliday, the lead character, named Henry Theodore Finch, is a little boy about 5 or 6 years old who overhears his dad talking about how he lost his job.

Believing this “job” is some sort of tangible object that his dad misplaced, he puts on a cape (the red bedspread) and searches all over town for the object. The character design and environments are more complex, which suits this character, who must go through the emotional ups and downs of helping his unhappy father. Sterling wanted to have the character interact with a more complex background as well, so he designed the initial layouts, shown in Figure 4.6, in 3ds Max. The image appears gray because it has not been painted with color or texture yet.

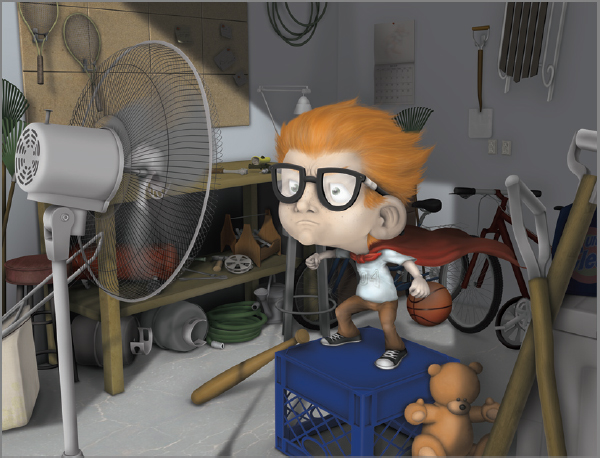

The character of H. T. Finch is certainly more complex than Sterling's Weldon Price character. He sports Chuck Taylor shoes along with tape holding his thick glasses together, to help show his vulnerability. The character was generated as a pencil sketch and composited over the background on a layer in Photoshop. The character and background were then painted out completely in Photoshop, and Sterling was able to use the shading of the shapes he had created in 3ds Max to help paint a believable world with correct perspective. Figure 4.7 shows the final render.

FIGURE 4.6 The design for the environments in The Red Bedspread were created with 3ds Max, so that the artist could create believable volume and perspective.

FIGURE 4.7 The finished art for The Red Bedspread was accomplished by rendering the 3ds file as a 2D image and then painting over the gray mesh in Photoshop to create the final world where Finch exists.

RENDERING 2D IMAGES FROM 3D SOURCES

Quite a few 2D backgrounds or characters can be designed in 3D. One of the advantages of this approach is that the camera in the 3D program can be moved around the image to get just the right angle the artist wants to use to then paint the finished 2D piece. The focal length of the camera lens can also be adjusted. 35 mm is the standard length for the lens and is meant to mimic the way humans normally see things. Changing the focal length of the camera allows the viewer to create the impression of being closer to or farther away from objects, without physically moving closer or farther away. Changing the focal length tends to be something to adjust when rendering out backgrounds, however, it can be used to alter the appearance of a character or prop.

Once the render has been created from the 3D program and opened in Photoshop, then the following steps are one approach to creating beautiful images that show believable volume (shadow and highlight) and perspective.

- Open the image in Photoshop.

- Duplicate the layer.

- Multiply the top layer. (This will leave the shadows. Multiply can be found in the blending modes at the top of the layer menu.)

- Create layers underneath and paint in color or add real textures.

- The multiplied layer on top will automatically provide believable shadows over the paint and texture layers underneath.

Reading can be another source of inspiration. Nick Kozis, animator and character designer, says, “Choose anything from novels, short stories, and poetry. Do whatever it takes to get your imagination working. At this point I just read and try to limit my visual exposure to the subject matter. I enjoy focusing on what I am reading and let my imagination run wild. In doing this I try and get a fresh look. With the amount of visual references available to artists these days, it's easy for anyone's work to become derivative.”

Nick Kozis offers his process for creating a character, along with some resources and advice for designers.

Start with the basics: “Visually, when I begin to develop a character, I like to start with the basics.” “In this case the character is posed in a standing position. The best are 3/4 front stances.”

Use a variety of references: “There are a lot of photo references that are available for artists. Try and show the character in an action.” “After I establish a pose I can use, I begin to gather references of subjects that I would find interesting to draw. I combined some photos of dinosaurs and images of tribal humans. It's important to have as much detail in your reference materials as possible. The more you are looking at, the more you may use in your final painting.”

Think about your character from the inside out: “A good practice is to start looking at skeletal structures. Then look at muscular systems, followed by textiles and costumes. Work a design from the inside out. This will give your imagined characters a degree of believability.”

Love what you're doing: “You should always draw what interests you. If you want to get good, challenge yourself. Embrace the process and don't worry about the end product. The process is everything; if you love doing it, you will get good at it.”

Nick also recommends looking at what others in the field are doing. This is part of staying current. It's good practice to be aware of how other artists work, study their methods, and pick up tips on how they derive inspiration from blogs and sites like www.conceptart.org, where numerous projects are posted with comments on how they were created.

Staying current also means understanding what trends exist in the industry. Trends give you information on what kinds of games are popular; what kinds of characters, props, and environments are popular; and what the next big interest is likely to be. Popular culture is another good indicator. The Harry Potter books swept the world with their tales of magic and spawned a series of über-successful movies and games. Graphic novels, classic stories, popular movies, fashion trends, comic books, toys—whatever people are talking about (and you can easily uncover this by reading blogs or news sites or walking through the mall) can be a source of inspiration.

Functionality of Characters

What types of things does this character need to do?

When you work as a professional in the game industry, you're essentially a professional problem solver. Your problem is how to design the character's functionality to best meet the needs of the project. One of the first ways to determine this is to understand some of the physical things the character must do in the game. Does your character need to do any of the following?

- Jump

- Run

- Fly

- Swim

- Turn invisible

- Talk

- Sing

- Dance

- Carry one weapon, or two, or three

What your character needs to be able to do is story- or gameplay-driven, but how you portray these actions depends on your platform. Examples of platforms are

A platform is the playback system used to play a game.

- Your PC

- Cell phones or other mobile devices

- A console—like a PlayStation or Wii

- A video arcade machine

Be sure you know what the technology you'll be working with can support. Small games designed for mobile applications like cell phones or iPads need to have simple, larger graphics with clear, easy-to-see movements. Some game engines can support complex movements, whereas others are limited to simple ones.

The concept drawings for your characters should be expanded to include action poses. And if the gameplay will be complex enough to show close-ups of the characters, the concept drawings should provide variations in the faces to include an emotional range and lip sync.

Again, I can't stress enough that in order to do this well, you need to avoid copying too much what is already out there. Go back to the basics. Use a mirror to study your own face while you form vowels and consonants or show emotion. Watch other people or animals while you're out and about, and notice their body language. These things will give you ideas for how to pose your characters and design faces for intrinsic movements.

As the concept is refined, additional sketches can include a lineup of characters, to indicate how large they are next to each other, along with different outfits, props, and any items that may be worn, held, or interacted with.

Designing props goes through the same type of process. The gameplay style and storyline describe what kinds of props are needed (for a shooter, you need shooting props; what kind will depend on the setting and other story details). As with character detail, platform limitations affect prop design.

Functionality of the Interface

Even in the early phases of doing concept work, you need to focus your attention on the design of the interfaces. These visual elements also need to fit in with the game's look and feel and are a major component of how gamers will interact with the game.

An interface can be any of the following:

- Sign-in screen

- Options page (where the player can change video and audio settings, among other functions)

- Toolbar

- Maps

- Navigation panes

- Inventory panes

During the initial phases of designing visuals for the game, the type of game-play and the goals of the game indicate which types of interfaces the game will need. For example, if the player must collect a certain number of elements before the game can be won, then an interface needs to be designed to hold those elements (such as an inventory bag or bank). Interface design will be covered in greater depth in Chapter 6, “Gameplay Navigation.”

Backgrounds

Creating concepts for games—especially ones that involve moving characters in real time through 3D space—can often mean elaborate and sweeping backgrounds to help convey the grandeur or complexity of the story.

Naughty Dog games, located in Santa Monica, California (a subsidiary of Sony Computer Entertainment America LLC), created the video game series Uncharted. Uncharted 3, released in 2011 and designed for the PlayStation, is a big, bold action-adventure game about fortune hunter Nathan Drake, who travels from one climatic extreme to another in search of treasure.

Figure 4.8 is a concept painting for the game that shows not only the multifarious environment, but also the character Nathan Drake and elements of gameplay (the gaping hole to be explored).

FIGURE 4.8 The incredible distance, level of detail, and atmosphere help add to the immersive quality of Uncharted 3.

OH WOW! ROOMS

Often, the complex, elaborate paintings created as part of the concept are grouped together and hung in one room called the Oh WOW! room while production is underway on a project. People coming on board a project who want to get a sense of what the game is all about can immerse themselves quickly in the look and feel of the game by hanging out in the Oh WOW! room for a while. Oh WOW! rooms can also be digital. These concept pieces (background, characters, and props) can certainly be viewed digitally as well.

Fans can enjoy collections of the paintings that are gathered and printed in books that are sold with collector's editions of games. These pieces can also be used in game trailers, posted online for fans to enjoy, and given away in contests. What fan wouldn't want an original concept piece used to inspire a game?

Methods for creating concepts for backgrounds depend on a few things:

- 2D or 3D

- Gameplay style

- Demographics

- Genre

- Playback systems

Again, as with the characters, some of your parameters for the concepts are based on the game's technology and whether it's 2D or 3D.

If you're working on developing backgrounds for 2D games, you'll need to know if the game background will remain static or will move, as in a side-scroller like the Mario Bros. games. Backgrounds in games are not only stages for the action taking place; they can also become an integral part of the gameplay. Characters or other elements from the game may need to interact with the background, as in adventure games where doors open or parts of the background move or fall away to reveal clues. Hidden object games' (HOGs') backgrounds tend to have dozens of items that need to be found, laced throughout the environment.

When designing backgrounds, come up with the look for the environments: those concept pieces that often find their way into Oh WOW! rooms. From there, you can begin to come up with more detailed layouts that the designers can use as temp art pieces to begin actually building the game.

Until finished art is ready to put into the game, temp art can be roughed out and used during game builds.

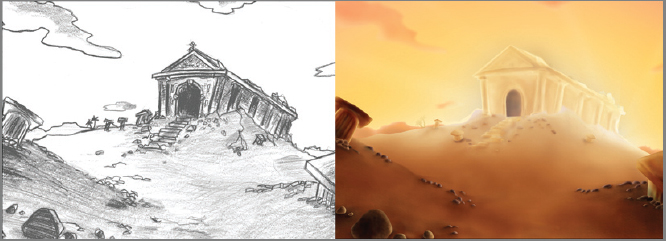

If the game is 3D, then background designers work with either a 3D package or the game engine itself. For many backgrounds, especially 2D, creating a pencil sketch and then painting that in a software package like Photoshop is an ideal way to go. You can see the result of that approach in Figure 4.9, a background created by Franklin Sterling III for his Out There project.

Maya, 3ds Max, and CINEMA 4D are examples of 3D packages. Crytek is an example of a game engine.

FIGURE 4.9 Out There needed to have a large-world look (the main characters literally travel the globe) while remaining simple enough to work with the character design.

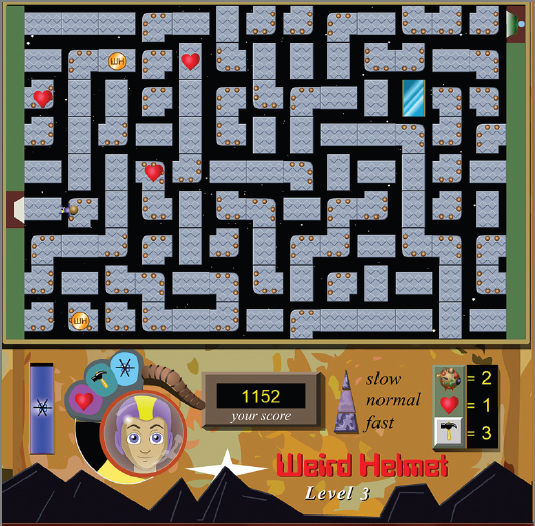

While creating backgrounds, it's important to understand which paint package will be used for the final render. Photoshop, using raster images, can be used to create massive amounts of detailed textures and lighting. Vector images tend to be flatter, although you can create some truly astounding lighting and impressions of depth and distance with a bit of clever manipulation of the software, particularly using gradients. Figure 4.10 shows a background from the game Weird Helmet, created by Star Mountain Studios. The background was created first as a pencil layout and then painted in Flash. All of the texture shown on the toolbar at the bottom was created as separate, small vector pieces. The finished effect is one of an aged, highly textured background, but because it is vector, it is highly scalable and a much smaller file size than a raster image.

FIGURE 4.10 The background for Weird Helmet needed to convey an impression of being in outer space using just flat color and vector art.

Even though a game may be designed strictly for 2D gameplay, occasionally a more realistic world needs to be created. Although pencil layouts work well for this, using a 3D package to build a rough layout of the environment works exceptionally well. One of the benefits is that the designer can rotate the camera inside the environment and decide which view is best for the scene being worked on for the game.

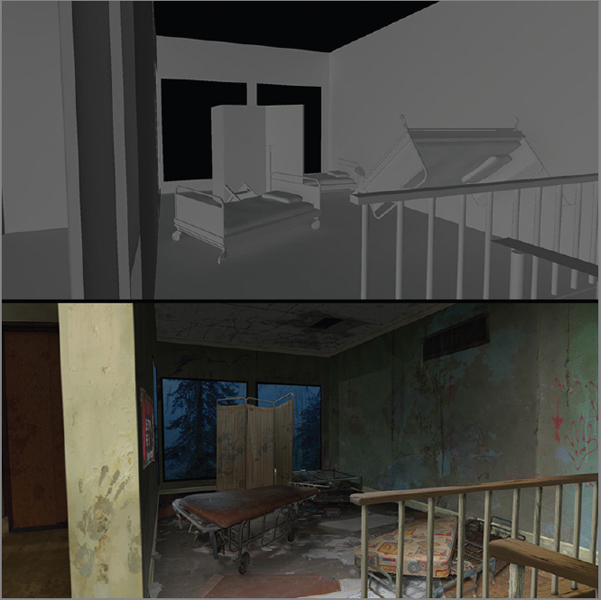

In addition, if a 3D package is used, the camera's focal length can be shortened to make the background look warped, curvy, and somewhat comical; or lengthened to appear more photorealistic. The camera can look down into the environment, showing establishing shots or areas of the room where clues in the game may be hidden; or dropped low to look up, giving a spookier appearance. Figure 4.11 shows the rough 3D render for a background from a haunted-hospital game created by Star Mountain Studios along with the finished version. Once the camera angle was decided on and the image was captured, the final paint was done using matte painting techniques in Photoshop.

FIGURE 4.11 For the background in this haunted-hospital game, the rooms were roughed out using Maya, the camera was rotated to provide the desired angle, and then one frame was rendered out. That frame was used as the layout for the 2D paint.

Backgrounds designed for full 3D movement are trickier. Designers are aware that they have to deal with the x- and y-axes (up and down/right to left), as well as the z-plane (depth). Games that allow for 3D movement render each frame as the game is played, so the game engines are usually used to lay them out and paint them; but many of the more detailed assets, such as houses and foliage, are built in a 3D package and then imported into the engine.

Another approach for creating backgrounds uses an engine with elements that can be used to build the background. The company Crytek has an engine that will create all types of backgrounds, from dense jungle to a wide range of architectural building styles. Figure 4.12 shows a background created using the Crytek engine. During gameplay, the scene you're seeing is redrawn in real time, frame by frame, as you, the controller, move through the environment.

FIGURE 4.12 This background was created using the Crytek engine.

Understand the Physics of the World

While working on concepts for a game, keep in mind the physics of the world you're creating. Is it underwater, in outer space, or in high winds? Is there weather, and if so, what kind? These things are essential to understanding what needs to be in the worlds you're creating—including props and backgrounds.

In addition, by reading the lore or script, you'll note that perhaps a character or characters always fly through the world; if so, you'll need to consider designing bird's-eye views (what the world looks like when the character is flying through treetops or between mountain peaks). By the same token, your character may travel the world by boring through the Earth's crust, in which case you'll need to design worm's-eye views for some of your scenes.

Understanding basic perspective is also critical when doing drawings. Because part of your job, when creating backgrounds for a game, is to give the sense of depth and distance, reviewing one-point, two-point, and three-point perspective is helpful. One-point perspective shows a dead-on view of the world, as if you're standing on railroad tracks and seeing how they disappear on the horizon line. Two-point perspective gives a more interesting three-quarter view, and three-point helps you draw bird's-eye and worm's-eye views.

Previsualization

Previsualization (previs) is an overarching term that refers to any aspect of designing the concept work for the game's visual elements and making decisions about how the final work needs to be produced. If, during the concept phase, art is created to show examples of a character as a 2D element and also as a 3D element, then a decision must be made about how the final design will be implemented: 2D or 3D. Once that decision is made—let's say the decision is 3D—then the final design and production of the character go to the artist or department that specializes in creating 3D work.

TYPES OF PREVIS

Previs can be broken down into five categories:

Pitchvis Shows potential for an unproduced project; a pitch

D-Vis Design visualization

Technical Previs Dimensional work

On-Set Previs Real-time work, usually done on the fly during production

Postvis Refinement after production is underway

Because there are so many specialties when it comes to creating a game animation, 3D model building and rigging, 2D and 3D environments, programming, animation, sound, and so on, previs helps sort out who is going to make what.

When you're planning a scene for a trailer or deciding how sequences in the game need to be executed, the mechanics of actually building it is one of the things previs can help sort out. During the previs phase of development, decisions are made such as who will build the 2D elements, 3D, animation, music, dialogue, sound effects, special effects, and so on. There are a great many details to track while building a game, and using previs to refine what needs to be done, by whom, and when is critically important.

Previs can indicate what needs to be done, and it can also point out gaps for design elements that had not been considered yet, or show problems with production that may be too expensive or pointless to pursue.

Storyboards

When it comes to designing characters and planning how they will work together with other characters, bosses, quest givers, and anything else they might interact with in the game, entire sequences may need to be boarded out (depicted in a storyboard) to gain a clearer understanding of how the story is being told, how actions need to be planned for, and what other elements need to be designed, redesigned, or eliminated.

Storyboards are essentially blueprints, or roadmaps, if you will, that can communicate to members of a design and production team what needs to be created and how events will unfold. They help save time and money once a project goes into production, because they indicate what things need to be created and where people need to focus their time: they can also provide insight to help you eliminate unnecessary elements.

Games, like most projects, have one or more creative directors associated with the endeavor. After making creative decisions, their most important goals are as follows:

- Communicate the vision to other members of the team.

- Allow team members to offer feedback, based on the vision, on ways to implement, change, or enhance the design.

Storyboards are an important tool to accomplish both of those goals.

You may wonder how a game can be boarded out if characters can go in different directions. Don't think of them like storyboards created for a movie or TV show, where the story and action unfold in a linear manner from opening scene to final credits. Storyboards for games help plan actions and events that need to be created by the character/prop designers, background artists and animators, engine designers, and game coders.

Your flowchart (see Chapter 3, “Core Game Design Concepts”) helps point out decision points in the game. Storyboards are created to help design more detailed interactions for major plot points.

Storyboards are also used extensively for cutscenes (also called cinematics or in-game movies) and trailers for games.

ORIGINS OF CUTSCENES

The first cutscenes in games were created as a type of intermission, or interlude, during gameplay.

In 1980, the game Pac-Man had little animated movies that showed Pac-Man being chased around by the ghosts he battled during gameplay. These original cutscenes were silent; it wasn't until Donkey Kong, in 1981, that audio was added to them.

World of Warcraft: Cataclysm has cutscenes throughout the game; however, when your unique character reaches a plot point where the cutscene starts, the game engine drops your character directly into the movie. You don't interact with the other characters or elements of the scene, but it makes it more fun to see your character moving around in the movie.

Usually, cutscenes are linear movies that play from start to finish without interaction. Technology is coming that will allow players to interact with them.

Just as for film or TV production, game storyboards tend to be a combination of graphics and text. The graphics are loose drawings that provide a visual blueprint of what is going on in the scene; they can be drawn over several panels to show progressions of the actions. The text is generally any dialogue that is spoken, voice-over narrations, instructions for things that need to be created for the scene (effects, animations, assets, and so on), and identifiers, such as the scene number or date.

Again, at this stage of production, the storyboards are meant to be a flexible design tool. They communicate the vision of the project to other members of the team, and they also identify gaps in the gameplay, or what I like to call boat anchors—graphics, animation, or any gameplay element that doesn't work and will drag down the whole project.

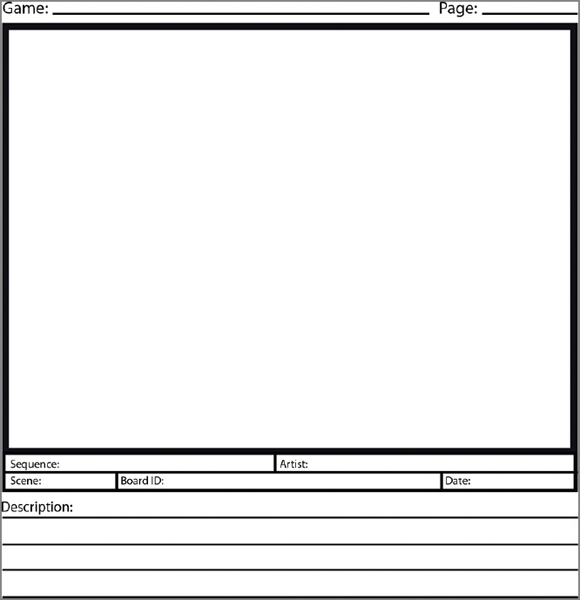

Figure 4.13 shows a basic storyboard panel template. You can create your own storyboard, stringing together several panels on a vertical or horizontal page, depending on which works best for you.

FIGURE 4.13 This image shows a form of storyboard template.

Boards may be more or less elaborate, depending on the needs of the project. Some storyboards are just walls covered in sticky notes or 3×5 cards tacked to a corkboard. Some people write directly on the wall, while others scribble on tablecloths during lunch. I have seen all kinds of storyboards in numerous formats. Again, it all comes down to someone communicating a vision and information to someone else. In other words, although I'm showing you a template here, that doesn't mean you have to use it. You may choose to design your own and fill it with the data your project deems important.

In professional game production, once boarding has begun, dollars are being spent; therefore, the most focused, efficient method for producing storyboards is the way to go.

Animatics

Animatics are a previs tool used to help show timing. Storyboards can communicate massive amounts of information—what characters, props, and backgrounds are needed for specific parts of the game; camera angles; and how cutscenes will work. One of the things storyboards can't do effectively is show the timing involved.

You may write on your storyboard how long an event will take; however, that information tends to be difficult to perceive. Experiencing events over time is tough to communicate unless you can show someone how long an event will need to take place. That's where animatics come in.

Taking storyboards and animating the images using a time-based editing program allows the designer the luxury of showing how long an action or event really takes. In addition, the camera can move (zoom in or out, pan, and so on), and transitions between scenes can be added (cut, dissolve, or other transition effects).

There are several editing programs to choose from when creating an animatic, including After Effects, Final Cut Pro, Premiere, and Movie Maker.

While timing is worked out in this process, along with camera moves and transitions, audio is also added, such as dialogue, voice-over, music, and sound effects, to further enhance the movie.

Pitches and Vertical Slices

If you're in the process of pitching a game idea to try to sell the concept, a previs reel can help by creating a movie with movement and audio that draws your audience into the world you want to create. Should you get the opportunity to take the next step in a pitch—that is, to let someone get a sense of your game's gameplay—you'll want to create what is known as a vertical slice. Essentially, it's a short section of your game that has been produced as a playable piece. It might be a level, or a boss fight, or just moving through a section of the world to clearly show someone how the gameplay works.

The vertical slice is still part of the previs stage, because after it's completed, changes continue to be implemented. The vertical slice is just enough of the game to give a sense of the gameplay; it isn't meant to represent what the final game would look like. Often, vertical slices are full of temp art, animation, and audio.

In this business, talking about a game doesn't do much to further getting it made if you're seeking assistance from other artists, designers, coders, financial backers, and so on. You can wave your arms around all you want; but once you show someone how things will work with your previs reel, or let them run around in the game and play a piece of it with the vertical slice, your brainchild will speak for itself.

We revisited the concept of gameplay and how everything you do related to designing a game should support that. Characters can indeed be stars of the game; however, all that you do when it comes to designing and creating them needs to support gameplay. The same approach should be kept in mind when you're creating backgrounds or other elements that support the game, such as cutscenes and trailers.

Studying articles about design and development is an excellent thing to do as you continue to learn about designing and producing games, whether you're interested in character creation, world building, or the game itself.

Sites like www.gamasutra.com provide excellent articles and blogs related to all phases of game design and development, from the pitch to production to post-mortems. They show in depth how existing games were created—including the pros and cons. You should study games that are well received and have good design. You should also study games that have poor design, to learn what to avoid. This is very important!

When you do research about how games are made, pitched, marketed, and so on, you can get ideas about how to apply the same principles to your own projects, or where you might like to work in the industry based on some of the jobs and challenges you discover.

ADDITIONAL EXERCISES

Coming up with a unique look for a character can be a wonderful challenge, and fun as well. Pick one of the following scenarios:

- You're a timid little animal living underground on a distant planet. The colony, which contains thousands of other timid animals, is running out of water. Your grandfather told you tales of a secret well, deep in a dangerous mountain range, far from the safety of your colony. You decide to travel on your own to find the precious liquid that can save everyone. What do you look like?

- You exist in the dreams of a little girl living in a poor part of a big city. While she sleeps, you whisper to her, telling her how special and wonderful she is, and that she will grow up to be an important person. She does: she becomes president of the United States. Now she faces an unusual crisis: the first alien visitors have reached our planet, and they're hostile. You resurface in her dreams to help give her strength and support during these hard times. What do you look like?

While you work on your design, list the special attributes your character should have, and use those to help you sketch what your character will look like.

Another fun exercise is to select a favorite character from classical literature, such as Hercules, Icarus, or the Minotaur. Read stories related to these characters, and uncover the following:

- Where did the character live? (Determine the setting: what the world this character moved through and interacted with looked like.)

- What special abilities did the character have?

- Did the character have flaws?

- What things did this character need to do?

Based on what you uncover, come up with two or three different sketches, and see how one drawing alone can't work. Coming up with different looks shows you how diverse design can be and that you don't need to be limited based on pre-existing drawings of similar characters.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Why is it a good idea to come up with more than one initial concept design for any game asset?

- To avoid getting locked too early into a design that may later prove impractical

- To have a variety to choose from

- To keep as flexible as possible while the design process evolves

- All of the above

- True or false. A vertical slice is just a small section of a finished game.

- Demographic means _____________________.

- The geography created for the environments

- Genre

- Who the audience is

- A demo of the game

- True or false. When designing a character, supporting gameplay should always take precedence.

- Which of the following is not a type of previs?

- Pitchvis

- D-Vis

- Concept-vis

- Postvis