CHAPTER 2

Gameplay Styles

Gamers tend to be loyal fans of particular gameplay styles. Some prefer shooters, others like intricate story-based games, and still others love to beat the clock with timed action or strategy games.

Game designers understand that players tend to keep playing the same types of games, so they do a great deal of market research to find which gameplay styles are the most popular or profitable. In addition, knowing which games don't do as well, and studying those, can provide valuable insights before you invest time and money into designing your own games.

In this chapter, you'll explore different gameplay styles and some of the elements common to them. I encourage you to try as many play styles as you can to experience them for yourself. In addition, we'll take a look at the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) and how game companies voluntarily allow this organization to review and categorize their products based on the content of the game.

We looked at the history of games to provide insight into how and why certain games developed the way they did. With the introduction of digital technology and literally millions of gamers with a vast array of likes and dislikes, appreciating gameplay styles is an important aspect of understanding effective design.

- What defines a gameplay style?

- Clustering gameplay types

- Playing for fun and to learn

- Entertainment Software Rating Board

What Defines a Gameplay Style?

This concept is a bit elusive; however, the core understanding of what a game-play style is becomes easier if you think of it this way: games that have similar challenges with similar methods for winning or besting the challenge tend to be classified the same way. Games can also be classified by the kinds of people who like to play them. Using that method for categorizing a game is known as understanding the demographic for the product.

In a game, the player usually has a goal that he or she is attempting to achieve. To reach the goal, players make decisions during gameplay that affect the outcome. The player may need to slay an enemy or collect items or repeat a certain action until a specific score is reached in order to move to the next level or achieve the final goal—winning the game!

We'll examine the following categories in greater detail. Although they don't include all styles, large numbers of gamers play them:

- Role-playing games

- Action games

- Adventure games

- Action-adventure games

- Shooters

- Simulations

- Strategy games

Role-Playing Games

A role-playing game (RPG) is an extremely popular style whose attributes can be found in other games, including adventure and action-adventure. An RPG's unique qualities lie in allowing a gamer to assume the role of a character (such as a wizard, warrior, or knight) in the game, which is usually set within an illusory world that is highly influenced by the narrative (story) that drives the game.

ONLINE RESOURCES FOR RPG FANS

Fans of RPGs can exchange information about them at www.rpg.net. Most of the commercial RPGs, including Final Fantasy, World of Warcraft, and EverQuest, have official sites with fan forums where players can swap tips, movies showing gameplay, screenshots, art, and strategies for playing the games.

The origins of the style can be found in tabletop games where players use trading cards or carefully written descriptions and storylines and then discuss how their characters react in different situations. Dungeons & Dragons, created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, was released in 1974 by Tactical Studies Rules, Inc. This highly popular game, often known simply as D&D, is an excellent example of one of these tabletop games. One player is the Dungeon Master, who assumes the role of the storyteller and adjudicator.

Gamers still gather to play tabletop games, especially D&D. Information about when and where they gather, along with storylines, can be found at the Wizards of the Coast website, www.wizards.com.

Live-action games of the RPG type are also quite popular and are known as live action role play (LARP). Devoted gamers refer to themselves as LARPers; they write and then play out elaborate storylines while dressing as characters and interacting with each other.

Action Games

Action games challenge players through physical challenges, testing their hand-eye coordination and reaction time. Action games include shooters, discussed later, along with fighting games and platform games.

Platform games like Donkey Kong show the playing field from the side. The gamer navigates an avatar through a series of obstacles—for example, jumping from platform to platform—while evading hazards.

An early, successful action game was an arcade amusement called Space Invaders, designed by Tomohiro Nishikado and released in 1978. During game-play, the player manipulated a laser cannon that moved from side to side across the bottom of the screen. The goal was to shoot as many aliens as possible as they descended toward the bottom in rows. If the player succeeded in shooting all the aliens during this timed game, he won. However, if any alien touched the ground, the game ended instantly and the aliens were declared the victors. The popularity of this game is one of the reasons shooters tend to be thought of as their own category.

Figure 2.1 shows what the alien creatures from Space Invaders looked like. They were extremely simple, made from just a few pixels; because of the game's limited memory, that was all the designers had to work with.

Pixels (those tiny squares you see when you zoom in on an image) are the smallest units of data in a game. Different color combinations are used to create graphics.

FIGURE 2.1 The block-like appearance of the Space Invaders aliens is due to the small number of pixels used to make them.

In earlier games, resolution was very low because that was all the technology at the time could support. Space Invaders used a black-and-white raster display (the grid of pixels) and ran at a resolution of 224×260 pixels. By today's standards, that is a small display; modern console games are typically 1280×720 or 1920×1080 and use millions of colors.

Resolution refers to how many pixels are used to make up the entire screen you're viewing.

Because there were so few games for early designers to study when making new ones, their inspiration tended to come from a variety of sources. Nishikado was inspired by the video game Breakout and the movies The War of the Worlds and Star Wars when he designed the look for the characters. We'll talk more about inspiration in Chapter 4, “Visual Design.”

The blocky Space Invader images became iconic and were often used in films and TV shows to represent any creature or alien in a computer game.

Although action games can include first-person playing approaches, for the most part they tend to allow gamers to navigate levels using an avatar and a third-person point of view (POV). This avatar, the protagonist, is then maneuvered through various levels to do any or all of the following:

- Overcome obstacles

- Collect items (things needed like a key to enter the next level or power ups)

- Defeat bad guys and bosses

- Solve puzzles

Figure 2.2 shows a graphic from the game Call of Duty 4, Modern Warfare, a highly popular game from Activision. During gameplay, gamers go on military-type missions and race through flying bullets, explosions, and various forms of combat while shooting, jumping, dodging, and sometimes dying. For the most part, action games require skill and excellent hand-eye coordination to maneuver the avatar through these physical challenges.

The design of these games includes not only the avatar's abilities (physical capabilities such as jumping, wielding a weapon, and so on) but also unique environments for the levels. Levels tend to have very different looks. A gamer may successfully navigate his or her avatar through a level that looks like a jungle to move on to the next level, which may be the meteor-pelted surface of the moon or a seafloor on a distant planet. This type of eye candy provides a visual stimulus to gamers who are highly focused on the fast-paced skills required to maneuver their avatars through the perilous environments.

Action games often feature levels with distinctive looks and are often designed with obstacles that can be negotiated at high speeds—again, requiring excellent hand-eye coordination.

FIGURE 2.2 In Call of Duty 4, Modern Warfare, you can see how accurate the game is with explosions, realistically geared players, and plenty of action.

Adventure Games

Adventure games tend to allow players to move at their own pace through the various parts of the world, solving puzzles, unearthing treasures, and experiencing the story as it unfolds. Because of this slower pace, players can really study the environments, so the worlds are often more elaborate, richly illustrated, and quite often filled with things to explore, click, and open.

This form of gameplay originated in the 1970s with designer Will Crowther in his Colossal Cave Adventure, also known as ADVENT or Adventure. Colossal Cave Adventure was based in part on the layout of Mammoth Cave in Kentucky. Although the game was partially an exploration of a real place, there was an element of fantasy, with elves and wizards roaming the twisty mazes that cut through caves.

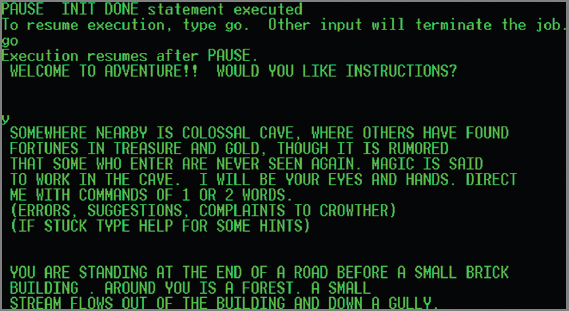

In Figure 2.3, you can see a sample from this text-based game. Text-based games are also known as interactive fiction because instead of using a mouse or other control device to navigate, players type in commands.

FIGURE 2.3 Colossal Cave Adventure is an example of a text-based game.

The opening text provided instructions on how to interact with the computer using commands of one or two words. In order to move around in the game, the player typed in commands such as Enter if the game told them they were near a door, or compass directions (north, south, and so on) to navigate to new areas of the game. Many early players sketched out a map on paper to track their travels as they dialogued with the computer.

Maniac Mansion, the first video game released by Lucasfilm Games, utilized an engine called SCUMM that allowed players to point and click instead of having to type so many commands.

The film Big opened with a boy playing a game that had the look and feel of Maniac Mansion combined with Colossal Cave Adventure.

Contrast the text in Figure 2.3 with the richly illustrated Myst III, Exile in Figure 2.4.

FIGURE 2.4 Myst features serenely quiet yet exotic-looking backgrounds that depict highly realistic environments just begging to be explored.

Myst, created by Robyn and Rand Miller and released in 1993 by Cyan, was a groundbreaking adventure game. What made the game such a phenomenon were the intricate and highly realistic worlds that gamers could move through as they solved puzzles to unlock more levels, or worlds, to explore. One of the unique aspects of the game was that it had several different endings, depending on what choices the player made during gameplay.

In Figure 2.4, notice the extremely realistic textures, the sky, and the curious structure in the center, entreating you to notice it and to come explore inside. The game is quiet, mostly a visual tour de force, with beautiful imagery like this at every turn.

Some of the adventure games available today are Telltale Games' Jurassic Park and Back to the Future, Pendulo Studio's The Next Big Thing, and Microids' Dracula 3: The Path of the Dragon and Still Life.

Action-adventure Games

Action-adventure games are a hybrid of action games and adventure games and may be the broadest type of game design in the industry. Adventure games tend to be more slowly paced and are focused primarily on storylines and problem-solving to get through the levels. When designers add some of the action elements described earlier to an adventure game, players can immerse themselves in the narrative of the game, experience more and varied personality types with their avatars, and enjoy faster-paced gameplay than in an adventure game while also solving puzzles and often experiencing a detailed and elaborate storyline. Tomb Raider, God of War, and The Legend of Zelda are prime examples of action-adventure games.

Fast-paced games can wear out a player, but slower ones can become boring. Action-adventure games combine fast moments with more in-depth storylines.

Shooters

A shooter typically falls under the action game genre; however, it's a separate category here because of the massive number of games designed this way. These games tend to be violent and are usually played as first-person shooters.

Shooters are a subset of action games. They're combat games played in either a linear or a sandbox style.

Many people consider Wolfenstein 3D to be the first game produced as a shooter. It was created in 1992 by id Software and published by Apogee Software. Figure 2.5 shows a screenshot from the game with its simple graphics and easy-to-read statistics running along the bottom. Although basic-looking by today's standards, for its time, the highly textured graphics were innovative. During gameplay, the player saw a hand holding a weapon in front of him as he moved through the 3D world. That method of gameplay has been used extensively in subsequent shooters.

The first-person shooter point of view is often called FPS POV.

FIGURE 2.5 Wolfenstein 3D amazed players with the ability to turn in a complete circle in real time.

In Wolfenstein 3D, you played a World War II POW named William “B. J.” Blazkowicz, attempting to escape from a German castle—Castle Wolfenstein. Along the way, you picked up and used weapons including a knife, pistol, machine gun, and Gatling gun. Addictive and a massive hit for its time, the game holds a solid niche in game development history because of its success. In 1993, id followed on its success with Wolfenstein by releasing DOOM.

At the time, DOOM was unique because more than one gamer could play. Players entered the game from their own computers using phone-line hookups or local area network connections (LANs).

As these shooters developed into more elaborate, complex games, the abilities the characters could exhibit increased as well. Instead of moving over static backgrounds and observing gameplay from a bird's-eye view, gamers could run around inside a world—jump, duck, dodge, turn corners, and go through doors to encounter new locations as if they were immersed in the setting themselves.

Shooters can be played from a first-person POV or a third-person POV, as in Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell.

Designers interested in creating shooters should keep in mind that the more immersive the game is, the more popular it tends to be. The more complete the immersion, the more the gamer can suspend disbelief. In World of Warcraft, for example, the environment changes to reflect time of day and exhibits weather that can include rain, snow, or fog. The game even has world events with quests and in-game prizes celebrating Halloween, Winter Festival, and so on. In the game Thief, conversations are overheard as the thief sneaks quietly about in the shadows, adding believability to that world. The more immersive a game is, the more players form an emotional attachment to their characters and feel like they're moving through a real world, regardless of how stylized it may be.

Designers create immersive games by providing overlapping stimuli, such as realistic movement from characters or animals coupled with weather and sounds. Psychologists call this immersive feeling presence.

Simulations

As previously noted in this book, simulations were developed primarily to help train people for difficult jobs. The military regularly uses them to prepare people for battle combat or operating large vehicles like tanks or jets and also to simulate using complex weapons systems without having to fire a single live round.

Simulators and simulation games are somewhat different. A simulator is a machine or device that mimics as closely as possible the real thing, like the cockpit of a plane. Figure 2.6 shows the game Navy Field: Resurrection of the Steel Fleet. This game has the player commanding a World War II ship to experience battle at sea. Although this game has RPG elements (the sailors you can interact with), the experience is essentially meant to replicate what a naval skirmish is like, right down to the historically accurately designed ships and weaponry, so this game would be considered a “simulation” as opposed to a “simulator.”

FIGURE 2.6 In Navy Field, all the ships and weapons are as accurate as possible to enhance the experience of entering into a conflict.

Simulation games try to mimic real situations and tend to fall into one of these categories:

Management/Construction SimCity, developed by designer Will Wright, is an example of a management/construction simulation game. In this game, you design whole cities. You also place inhabitants in the cities and look after their wants and needs.

Life Wolf, developed by Manley & Associates, Inc., allows a player to live like a wolf. The player uses the wolf's senses to make decisions about how to evade hunters, or track down and kill prey in order to survive.

Vehicle Abrams Battle Tank, developed by Dynamix, is a somewhat arcade-type game that allows a player to simulate driving a tank and deploying on missions to bombard the enemy or escort friendlies.

Other types of simulation games focus on medicine, politics, science, police work, exploring space, diving in the ocean, and so on. The premise behind their design is that the player is the one making the decisions that affect not only his own outcome but also the outcomes for any virtual inhabitants of the world and often the environment itself.

Simulation games, although designed to represent reality, can be used to teach or are played for fun.

Strategy Games

Chess is a classic example of a strategy game; as discussed in Chapter 1, “Game Design Origins,” so is the game Go. In this game style, the primary goals for the players are to determine methods for overcoming conflicts through planning and tactics. Strategy games tend to be designed for two players and are known as turn-based games—one player takes a turn and implements his strategy, and then the other player gets to play.

Gamers can play against each other in a strategy game or go head-to-head with a computer. In 1996, chess champion Garry Kasparov lost to the computer Deep Blue.

Sample strategy games include Silent Storm, The Battle for Wesnoth, Civilization, and Age of Wonders. The game Civilization, created by Sid Meier and released by MicroProse, is often referred to as Civ. The object of the game is to build an empire that will last; however, this empire is in competition with other civilizations. These civilizations compete for resources and technology and can go to war with each other for territory and other goods that can help them thrive.

Clustering Game Types

So far in this chapter, we've looked at ways games can be categorized by their style. We can also categorize games according to their purpose and who the game is intended for.

Designing for a Specific Audience

Instead of focusing solely on gameplay style, designers can choose to cater to a broader audience—casual, core, or hardcore gamers. Players may choose casual games to play, whether they're maze games or word puzzles or hidden-object games. By the same token, players can gravitate toward hardcore games that require substantial amounts of time to play through or have a darker or more violent game style, such as action or adventure games.

There are casual action games, and there are hardcore action games. They're differentiated by the level of intensity and immersion. You can use the same approach to categorize games in any of the gameplay styles we have looked at as either casual, core or hardcore. As a game designer, you may choose a certain type of gameplay to focus on, or you may determine what groups of different types of people tend to favor. By looking at a broader cluster of people, you may find ways to overlap or merge play styles to create unique and successful hybrids.

Casual Games

A casual game appeals to gamers who like an easy-to-learn, light game that doesn't require a large amount of time to play. Casual games can fit any genre. The only distinction that sets them apart is that these games tend to be played for a short amount of time and are meant to be a fun diversion in the player's day. Although most games that are considered casual games tend to be light and fun, any game that players like to delve into for brief durations could be considered a casual game.

According to the Casual Games Association, www.casualgamesassociation.org, the majority of casual gamers are female, are over 30, and play via the Internet.

The majority of games that people tend to jump into for short periods of time are card games, maze games, puzzles, and so on. Angry Birds (shown in Figure 2.7), which was designed as a mobile game by Rovio but can also be played on a home computer using Google Chrome, is a popular casual game.

FIGURE 2.7 In Rovio's casual game Angry Birds, the graphics are brightly colored and simple but highly engaging.

The goal is to slingshot different types of birds at pigs hiding in crude structures they have built to keep the birds out. The birds are angry because the pigs stole their eggs. This is a casual game because the gameplay is lighthearted and can be enjoyed in short chunks of time.

Hardcore and Core Games

Hardcore games tend to be extremely large and complex and can take months, if not years, to play through. Hardcore games are often dark, violent, multifaceted, and made up of elaborate storylines and intricate characters with a wide array of talents/skills.

Examples of hardcore games are Halo (developed by Bungie Game and published by Microsoft Game Studios) and Gears of War (developed by Epic Games and published by Microsoft Game Studios).

Like hardcore games, core games immerse gamers for hours at a time. Core games are less dark and intense. The violence in core games tends to be more cartoon-based than in hardcore games.

According to Satoru Iwata, CEO of Nintendo, the Wii U (successor to the Wii) was designed for the core (also known as midcore) gamer.

Both hardcore and core games are favored by gamers who like to compete not only with the elements of the game but also with each other. These types of games can garner fans who create intricate websites devoted to their character or characters, guilds, in-game achievements, stats, and so on. These fan sites are filled with tips on how to master the game, screenshots showing in-game accomplishments, and blogs.

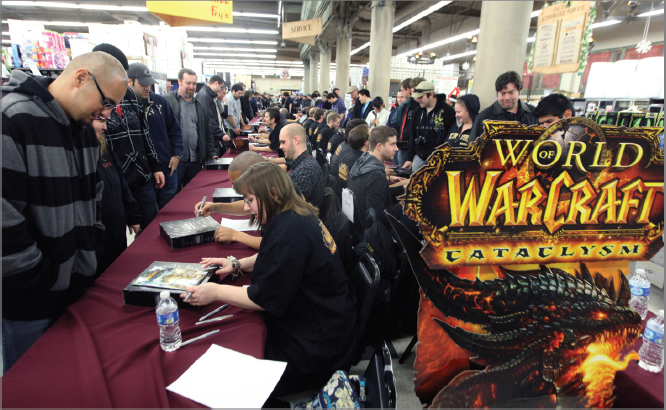

Figure 2.8 shows avid gamers queuing up to try Cataclysm, the 2011 release of the game World of Warcraft, from Blizzard Entertainment. World of Warcraft (WoW) is considered by many to be a core game; but because it has such a huge following, and gamers have admitted to playing for hours, sometimes days, at a time, some critics think it belongs in the hardcore category. However, even with its massive number of fans, as evidenced by this image, WoW lacks the dark, violent elements that are the benchmark for hardcore games.

WoW boasts fantasy characters such as dragons, orcs, and trolls, but it also has time travel and modern components like motorcycles and cars. World of Warcraft is the reigning champ of subscribed-to multiplayer online games.

Because there are so many players, World of Warcraft is grouped into realms (individual servers) that can hold up to 20,000 gamers.

Multiplayer Games

Massively multiplayer online games (MMOG) and massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) have grown substantially in popularity as more and more people have gained high-speed access to the Internet.

FIGURE 2.8 Fans of Blizzard's World of Warcraft lined up in droves to get a first look at Cataclysm when it debuted.

Multiplayer online games tend to be real-time games that allow players to not only move through elaborate worlds, solve puzzles, experience intricate storylines, and master quests, but also interact socially. Players can talk to each other in the guises of their characters during play.

These types of games can encompass any and all of the gameplay styles discussed in this chapter. The first game to launch online with graphics was NeverwinterNights, which debuted on America Online (AOL). Other, lighter versions of MMOG exist, such as FarmVille, shown in Figure 2.9, which most players discover through Facebook and which is actually considered a social game. In this game, developed by Zynga, players can grow crops, sell their harvest, and produce livestock.

Social games run on a social network (like Facebook) and earned their name from that distribution platform as opposed to the games being “social.”

Whereas World of Warcraft is a for-profit game (garnering profits in excess of $2.2 billion), and players pay for the initial installation then remain connected through a monthly subscription, FarmVille is free to play. Social games like FarmVille make money through the sale of virtual goods to players and by selling ads.

FIGURE 2.9 In the social game FarmVille, players grow crops and interact with each other online to keep moving forward in the game.

Playing for Fun and to Learn

Learning theory suggests that we learn more and learn better when we have some fun doing it. Based on that theory, game designers are developing better-designed, more interesting educational games. Because these games aren't dull or boring, they have more staying power (people want to play them, and the more you play, the more information sticks).

The value of learning by playing is being embraced by more than the educational industries. These types of games are developed now to help train workers as well as students.

Most designers have adopted the term digital game-based learning instead of educational computer games.

Serious Games

Although this category sounds foreboding, serious games can be fun. Essentially, you can think of them as games that have problems designed into them that gamers need to solve. The term serious was derived from the book Serious Games, written by Clark Abt and released by Viking Press in 1970.

The term gamification has been coined by serious game designers to describe how players use the mechanics of the game to help solve problems.

As you learned in Chapter 1, military leaders use games like Kriegspeil to help train troops. The business sector has also embraced gaming as an approach to training methods for all kinds of jobs, from accountants to surgeons to human resource managers and so on.

Because people do learn from playing games, developing games that help them solve problems and thereby better society or improve workers' job performance is becoming big business.

The Serious Games Initiative, a summit for game designers, first met at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C., in 2002. Its purpose is to provide a forum where designers can discuss serious game design.

Educational Games

When designing educational games, you want to focus on making a fun game. If the design isn't fun, students won't play, and no learning can take place.

The goal for educational game design is not to teach, but to have fun. Learning is a byproduct of repeating the gameplay.

Incidental learning is a phenomenon associated with playing games. Marc Prensky, noted author of Don't Bother Me, Mom—I'm Learning (Paragon House, 2006) and Teaching Digital Natives (Corwin, 2010), says of gamers, “They learn to make good decisions under stress, they learn new skills, they learn to take prudent risks, they learn scientific deduction, they learn to persist to solve difficult problems, dealing with large amounts of data, they learn to make ethical and moral decisions and to even manage, in many games, businesses and other people.” Prensky points out, quite well, that the conditions a game sets up offer learning opportunities even if the game doesn't appear to teach, reinforce, or test specific knowledge.

In the early 1990s, when home computers were becoming more common and educational games were being designed for that market, the creativity fell off substantially. Too often, games were designed as “drill and kill” games and earned the unfortunate moniker of “chocolate-covered broccoli.”

Since then, the educational-games industry has been going through a significant learning curve. Many contend the industry is still learning how best to design games that can teach but are also fun to play.

Online sites that group several game choices together are contributing significantly to advancing good digital game-based learning. Students, parents, and instructors can peruse these sites and read reviews about the games, understand the teaching objective for each game, and then play for free or try before they buy.

One such site can be found at www.funbrain.com, which is part of the Education Network and caters to K–8 students. The site hosts games to help improve math and reading skills. It also provides resources to parents and instructors and launched Diary of a Wimpy Kid.

Educational games designed with a combination of learning material and entertaining gameplay are often referred to as edutainment.

Entertainment Software Rating Board

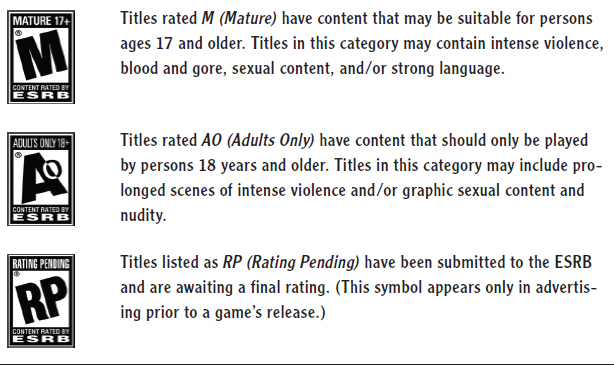

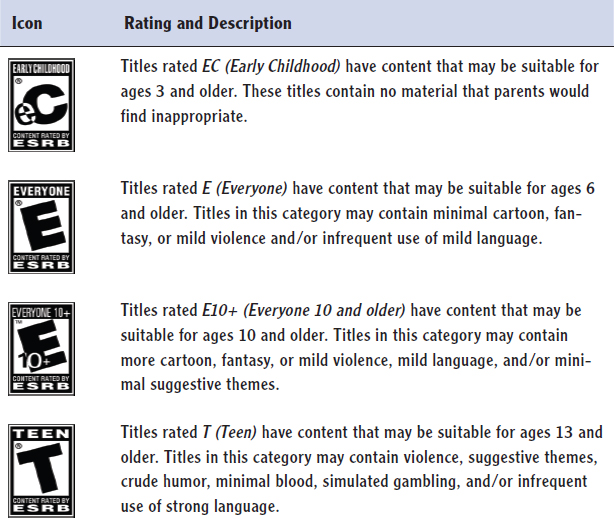

As noted, certain types of games tend to be violent. The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) rates games based on this and other criteria.

The ESRB was formed in 1994 as a nonprofit self-regulating organization by the Entertainment Software Association (ESA). To learn more about ESRB, visit www.esrb.org.

When designing games, you should understand what ESRB ratings mean and why they're important. Table 2.1 displays the seven ESRB ratings icons along with a definition of each rating.

Source: www.esrb.org

Although the rating system is voluntary, most commercial game producers choose to have their games rated because the majority of retailers in the United States and Canada only stock games that have the ESRB ratings on them. To get a rating, a producer fills out an ESRB questionnaire with information about aspects of the game that deal with drugs, sex, and violence. The producer submits the game, along with video showing scenes in the game that deal with any of those things, and scripts from the game. Three reviewers who are not associated with the games industry go over the material and then submit their findings to the ESRB along with their recommendations for what rating the game should receive.

Game designers should be aware of how the system works and how these ratings are derived, because in order sell your finished product through any retailer, you'll most likely be asked to produce your rating.

Designers often rework games that receive an unexpected or undesirable rating and submit their games multiple times until they hit the requirements for the rating they're after. Most games are targeting a specific audience to gain the most fans and/or sales; therefore, these designers want to make sure they have the ESRB rating on the box that lets a specific audience know the game they're buying is truly designed for them.

You can decide what gameplay style may work best for an original game based on examples from existing games, and there is absolutely no reason you can't combine styles. Some games match the criteria for certain gameplay styles, but there are no hard and fast rules. These categories exist to help designers make choices on the best way to design their games. They also exist to help gamers search for new games based on their experiences with similar titles.

ADDITIONAL EXERCISE

Go online and take a look at some of the sites where you can play games, such as www.kongregate.com, www.bigfishgames.com, www.candyland.com, www.gamenode.com, and www.addictinggames.com. Review the categories these sites use to classify their games. Pick at least three different games from different categories and play them, taking note of what type of gameplay style you believe the product to be. Does it match how the game was categorized? If not, why do you think the game was placed in the category where you found it?

Pick two games from one category—say, two adventure games or two action games. Play them both for at least an hour or two, and then compare how the games are similar and how they differ based on the way the gameplay styles were described in this chapter.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

- Which is credited with being the first adventure game?

- Wolfenstein 3D

- Colossal Cave Adventure

- Civilization

- World of Warcraft

- True or false. If a game design becomes more immersive, it allows the player to suspend disbelief.

- Which type of game tends to be turn-based?

- Simulation

- Adventure

- Action

- Strategy

- True or false. The ESRB rating system is required for any game sold in the United States.

- What term do psychologists often use when referring to how immersive a player believes a game is?

- Spatial acceptance

- Delusion

- Presence

- Make-believe