Chapter 5

The Power of Process

Structure

The odd couple is a cultural chestnut: one partner is fastidious and methodical and the other, while not necessarily messy, is freewheeling and less rigid in organization. At work, the gap in styles can seem serious, with one employee adhering strictly to process and making a list of measured steps toward a goal, while a colleague prefers heart-racing sprints to deadlines.

Is one way superior? Does the methodical march to the finish line guarantee more detail and accuracy, or does working fast sharpen focus and eliminate waste? The Birkman, as always, believes there is value in everyone’s preference, no matter where they fall on the spectrum it measures as Structure.

The person scoring high in Structure brings to the table a calm and orderly working environment. This relational Component was once labeled Insistence because the high scorers on this trait insist on following systems and procedures. These employees tend to say, “I’m organized, and I’ll get this done my way.” They often earn praise for creating order out of chaos. But don’t assume they appreciate Structure for the sake of Structure or accept your idea of Structure. Many high Structure employees would rather work under their own system than be pushed to adjust to a Structure already in place. And because these high scorers are so good at putting plans in place and following through with them in a consistent and organized fashion, Structure serves as a kind of enforcement ability. It is another way to exert authority. High Structure people might be the insistent accountant who complains about your late expense-report receipts—which you feel you have absolutely no time to do.

As with the other Components, the Birkman can find value on either end of the spectrum. Components possess inherent strengths, needs, and stressors. They just play out differently depending on your score. Considerable strengths accompany low Structure qualities as well as high Structure ones.

Low Structure people bring flexibility, spontaneity, and an ability to improvise and quickly shift course. Often they are creative and function best—even thrive—when they have a great deal of freedom and elasticity in the way they do their job. Because many C-level executives are low Structure, they need staffers who have high Structure scores to help them stay organized, maintain their systems, and get things done.

Not craving Structure doesn’t mean people are disorganized. They may have their own perception of being organized. They just don’t need a rigid environment to do their best, and they don’t want one. They also are the types who might think rules are made to be broken. Healthy organizations balance flexibility with procedure to suit both styles of Structure employees, creating an atmosphere that is organized enough to give a sense of security without stifling anyone’s way of being productive. Executives have to make sure their company or organization can accommodate the variety of talent working in it. This is especially important when jobs and whole industries are going through major transformations.

STEPPING ASIDE

A senior executive at a university health center in Salt Lake City had to learn how to rein in some of her high Structure proclivities in order to get out of the way of her reports. Utah consultant Patricia A. Russell’s client was a high-ranking executive who paid close attention to detail, and that meticulous way of working allowed her to build a strong career in the medical field. She climbed up the ladder at the hospital, where she was considered a conscientious and dedicated leader. She set lofty goals for herself and her team, and felt she was helping the team members achieve those goals by organizing their work in great detail, including to-do lists and thorough verbal instructions.

Invariably she was frustrated by what she saw as her reports’ lack of initiative and their failure to be creative. The employees, for their part, felt that they were micromanaged and that any creative spark they had was immediately doused by directives. “Frustrated” is how they described themselves. They weren’t given the freedom or encouragement to find their own solutions to problems or discover innovative ways to achieve the set goals. As individuals, each felt unappreciated and disrespected. No one could figure out why the goals, clearly within their capabilities, were being missed. And the situation didn’t improve even when they started working harder.

The dynamics of the Structure Component that Patricia explained to the executive and her team was a revelation to them. The boss understood that despite her good intentions, her high score for Structure Usual Behavior, coupled with her very high Structure Need, showed how her overattention to detail stifled her team. In light of this discovery, she began to give her reports the breathing room they needed to do their best.

The boss still set goals for them, but she stopped dictating exactly how they were to be achieved. When she relaxed the reins a bit and started trusting the creative energy of her team members, they began to flourish. They worked together to meet their goals using their own ideas and initiative. So dramatic was the improvement that the chief executive reported it had an immediate impact on the bottom line: a 6 percent group improvement in revenue over several months and a 5 percent increase on average in employee satisfaction, according to the consultant. That is the power of Structure—at both ends of the spectrum.

DETAILS, DETAILS

Bob Brewer of Oxford, Mississippi, also counseled a chief executive with Structure issues. This executive had atypical scores in relation to Need and Usual Behavior, a so-called reversal. The CEO’s profile showed he tended to think in more detail than he communicated. The CEO knew precisely what he wanted his staff to do and always thought that he spelled it out. But in fact he thought about things so much that when he got ready to present them, he’d give them a once-over lightly, assuming too much knowledge on the part of the others.

When he would say later, “I told you how to do this,” they’d reply, “No, you didn’t.”

“He was forever amazed when the staff brought back something different from what, in his mind, he had asked for,” says Bob. The situation improved almost immediately when the consultant developed simple feedback tools to ensure clarity and completeness. He gave them a simple dialogue as a pattern. Before they left the boss’s office, the boss would ask one question: “What did I just tell you to do?” The staff would then tell him what they understood the assignment to be. They then corrected any misunderstanding.

“It took them five minutes to learn how to do that once they knew the problem,” Bob says. “That engendered considerably more peace in the relationship and more efficiency in their work together.”

MESSY COMPROMISE

Opposing Structure scores come up frequently in couples counseling. “I bet it’s close to 70 percent of the time a low Structure will marry a high Structure,” says Bob Bolling of Houston. “Perhaps it’s because they admire [the traits they don’t have] in another person.”

Bob resolved the odd-couple conundrum with his own wife with one agreement: all of the so-called public rooms in their home are to be kept at the high Structure standards of his wife. His office is sacred ground to him, and he gets to keep it however he likes. “She closes the door when people come over,” he says.

The issue of clashing Structure styles isn’t as easily compartmentalized in the workplace. The bigger issue isn’t any one score but how scores interact. Consultant Steve Cornwell of Atlanta counseled Shannon Woolard when she was hired as the director for Summit Management Corporation, also in Atlanta, which owns and manages a portfolio of hotels throughout the southeast United States. She was responsible for the performance of the company’s sales team and from the start wanted to optimize their work. Of the six members of her sales team, one didn’t seem to want to follow procedure. The woman got all her work done, but she wasn’t diligent about the paperwork required of all the reports. That lack of conformity was throwing a wrench in the overall process and was beginning to hurt her reputation among her colleagues. After the team members took the Birkman, however, they saw that she was the only employee on the staff who did not have a high Structure score.

“They all thought she wasn’t a team player, but it was just that she had to do it another way,” Steve says. “She was very relieved that everyone understood that about her, and afterward they looked at her differently.”

“The Birkman Method allowed everyone to get to know one another in a very in-depth way,” says Shannon.1 “We still have conflict, and the Birkman provides insight into how to guide us to quicker resolutions in an environment that is about reinforcing positive behavior verses focusing on what someone did wrong.”

Steve also helped a new executive with Structure issues. Jonathan Kupersmith opted for monthly coaching sessions when he was promoted to president of B2T Training in Alpharetta, Georgia. He wanted to avoid any missteps as a new leader. But before Steve could address those issues, he had to figure out how best to coach this new client. Jonathan had very low Structure scores, and Steve knew he had to tread lightly, especially not giving him a to-do list after every coaching session, his usual way of working. “I’m very high Structure and would have intimidated him if I did what I wanted to,” says Steve.

Instead, they kept sessions free flowing. Each session ended with Jonathan telling the consultant what he wanted to accomplish before the next session. “This way I wasn’t imposing tasks and structure on him that would have otherwise put him in stress and set the stage for an unsuccessful coaching experience,” says Steve.

Steve focused on helping Jonathan align his strengths with his job. It was clear that because of his low Structure personality, he needed to surround himself with administrative-support people who could carry out his ideas and keep order in his daily workday. He also wanted to make sure that the work his reports did fit their own strengths “instead of what they think the company needs,” Steve says. “That means figuring out what they need for success to reach their personal goals as well as the company’s goals.”

Low Structure employees seem to find their own paths to success no matter how much their process comes under fire. And their process often draws fire. Robert Hudson of Louisville, Kentucky, worked for two decades as a successful district manager for Burger King in New York and Miami, and for PepsiCo in Philadelphia. He says he always felt he was working in a style different from most other people in his workplace, especially because of his proclivity to ignore protocol and refuse to go through direct line communication. “Even getting good results, I wasn’t seen as politically correct,” he says. “Some in the upper echelon didn’t like the concept of doing anything it takes—from landscaping to remodeling to unconventional promotions—to expand my restaurant franchises.”

When someone suggested he take the Birkman, he found out exactly how his preferred style of working clashed with that of his colleagues. His Birkman showed he had a low Structure combination, with scores of 16 for Usual Behavior and 29 for Need. “It is hard for a person like me to fit into a corporation,” he says. “I found it difficult to balance my disregard for the rules with my desire to get results and find innovations to improve the business.”

Eventually he quit the food business and went into business for himself. Today he owns M&H Marketing, a Louisville, Kentucky, consulting firm that helps medical practices expand revenue. “I can maintain a flexible and responsive schedule,” he says. “I surround myself with detail people so they can do that work for me, and I can concentrate on exploring new ideas and options. I like working outside the chain of command!”

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Structure can have a big impact on how a team functions and clears a path to success. Wilson Wong of Atlanta recalls when he was asked to help a media company with a team that wasn’t performing well. He gave a Birkman to the twelve team members and saw that their varied Need for Structure scores was an issue.

The several who had low Structure scores in their Usual Behavior were keeping busy but had no direction from their team leader, who also was low Structure. “Everyone was doing their own thing, and nothing was getting done. They didn’t have any routine structure as a group, and they had high Activity scores with high Change scores, so they started on things immediately and with lots of energy—and would shift gears a lot.”

The team leader had an Authority profile that showed a particular kind of boss whom Wilson recognized: “They say, ‘Bring me a rock, any rock; no, not that one; no, not that one; I don’t know what I want, but I’ll know it when I see it.’”

To make it clear to the teammates what the source of their dysfunction was, Wilson had them do one of his “food for thought” exercises where teams prepare a multiple-course meal together and he observes how they handle it. He gave each of the twelve team members a menu for a four-course meal and also gave them a deadline. Then he sat back and watched. As expected, they split up and went in all different directions, with little discussion among them. The only planning the leader did was to get the table set. As it got close to deadline, they started turning to shortcuts. When it came time to start serving the meal, one dish was put on the table before the rest were ready, and it was cold by the time the other dishes arrived.

“It happened even though I warned them it would,” Wilson says. “It was one of the worst meals I ever had.”

Afterward they discussed how their Structure scores had played into the problem. In particular, he told the leader that he had broad ideas but no organization, no suggestions, and no coordination, which created overlap and lots of gaps.

A year later, Wilson led another team-building session with the group and asked them to cook a more difficult meal. This time they talked and planned before they started to cook. The team leader had a clipboard with a time line and assignments for each participant. The work was well paced, and the leader, clipboard in hand, kept control over every step. The resulting meal, Wilson reports, was delicious. The culture of the unit changed so profoundly, the consultant says, that when he checked in on the team leader two years later, his team was still functioning well despite some turnover.

THE BIRKMAN AT WORK: CORPORATE TRANSITIONS

Orchestrating Change

When a couple nearing retirement, Tom and Carolyn Porter, brought a young couple, Richard (“Jeff”) and Amelia Jeffers, into their prestigious fine-arts auction house in central Ohio, a generation gap was threatening to bog down the transition. The Porters had joined Garth’s Auctions in 1967 when the original owner wanted to take the thirteen-year-old company, then specializing in antique auctions, to the next level. Over the next two decades, the Porters helped the business gain a national reputation. By the mid-1990s, they began to think about a further expansion and, for the longer term, an exit strategy. They entered a partnership agreement with Jeff and Amelia after the company had grown to about thirteen employees. “It was going to be a huge transition,” said Amelia. The original owner had died in 1973, so the Porters had been independent for twenty-three years. “There were issues involving roles and decision making.”

The young couple joined in overseeing the day-to-day operations, but it was tough going. No one knew what roles to play in the new concern, deciding that in fairness, everyone was going to participate in every decision. But this system slowed progress. Amelia heard about the Birkman from one of the Porters’ daughters, herself a certified Birkman consultant. They decided to ask consultant Celia Crossley in Columbus, Ohio, for help. Amelia’s question for Celia: “How do we use our time, talent, and treasure in the company to ensure we have equal ownership and decision-making roles?”

“They kept saying that it was the age difference,” Celia recalls, because the owners were in their sixties and the new couple in their twenties. “They were different, but it wasn’t age.”

The consultant helped them see just how tangled the relationships were: “It complicated the partnership that we had four distinct independent entrepreneurial personalities and two sets of married couples,” says Amelia. “So it wasn’t only the partnership—our marriage partners also were our business partners.”

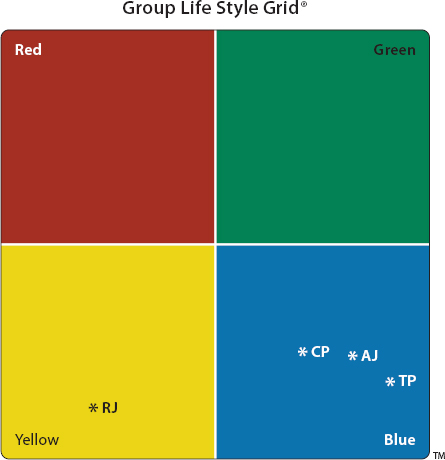

The four took the Birkman assessment and waited for the results. Each got individual reports, but to bring the group dynamics into sharp focus, Celia included group Life Style Grids that plotted their Usual Behavior styles, their Interests, and their Needs and Stress behavior. The good news was in plain sight: each of the four had clear strengths that were different from the others (figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 The Birkman Tracked Each Employee’s Main Interest

Jeff Jeffers was the only one with his Interest asterisk in Yellow, so he was tagged to act as chief financial officer. Carolyn Porter showed high Structure scores and a strong Scientific Interest, so she did the research. Tom, with a Persuasive score of 75, took on sales. Amelia, a Blue, used her creative talents to help develop new marketing strategies and groupings of collections for sale.

The Birkman also flagged some Stress points. Jeff’s results showed he was able to help plan a course of action with the group, but afterward would likely prefer to go into his office to work alone. Amelia learned she had to modify her behavior and communications style to be more patient and accepting of others’ work habits.

Amelia and Jeff took their reports with them as they headed out of town. She drove while he read the report. “Ah, it says you’re a little dictator,” she remembers her husband saying with a laugh. Her Esteem scores for one-on-one communication were relatively low (Usual Behavior, 28; Need, 49) and her Authority was the highest of the four: 66.

Amelia admits: “I don’t like to be sold on something. I want the facts: ‘Here’s what I’m offering, no beating around the bush.’ I put that out there, and it’s not always good, but it’s not mean or malicious.”

Carolyn and Jeff both needed to have people speak gently and respectfully to them before delivering any news. The couples, it turns out, weren’t pitted against each other. If there was any divide, it was Tom and Amelia on one side and Jeff and Carolyn on the other.

“Tom and I were quick to make decisions,” Amelia offers as one example on the Birkman profiles. “Jeff and Carolyn needed time to think. The Birkman opened my eyes not only to what I could contribute to my business relations with my three business partners, but it allowed me to look at my marriage and say, ‘Here’s what I’m putting out and what I’m expecting back.’”

One area in which they were all similar and in sync was in Structure, showing high Usual Behavior scores ranging from Carolyn’s 61 to Tom’s 90, with both Amelia and Jeff at 79. Their Needs in the Component were all relatively low—including Amelia’s rock-bottom 5. “All appeared fairly organized and planful,” says Celia. “None of them needed direction and preferred to follow their own course of action. As long as they each had their respective responsibilities and followed what they felt was the correct path while keeping flexible for changes, it worked.” They did that, and it did work. Today Garth’s Auctions has all its new employees take the Birkman. It isn’t used to filter candidates, Amelia says, but it saves time in helping new employees get placed in the company once they are hired. Most people, she says, can’t bring themselves to say to a new boss: “This is what I need you to give me for me to get my job done.” But that is just what the auction house management wants to hear—and what other bosses need to hear.

Amelia feels the Birkman made all the routine work in her company more diplomatic and more democratic. For example, although she owns the company, she shares an office so her bookkeeper can have her own space. The Birkman showed that the accountant needed it to focus (low Acceptance scores suggesting a need for time alone and very low need for Change).

In January 2006, the Jefferses took full ownership of the company. “We lost zero employees” during transition into sole ownership, Amelia says proudly. “I think the Birkman is a huge factor. You can’t overstate how the self-awareness made us better managers.” As of 2013, Garth’s Auctions has a large presence in the United States and a budding one internationally.

“The bottom line,” says Celia, “is that once they all recognized their behavior differences, and the ‘why,’ they could successfully move the business forward because they shared the same vision, hopes and dreams.”

Hire Variety

The Birkman helped guide a U.K. search-engine-optimization company through a whipsaw series of transitions from 2005 to 2010: a rapid expansion from 20 to 275 employees, its purchase by a U.S. concern, and the subsequent restructuring of its senior management team.

When the eight-year-old company began its accelerated growth in 2005, riding an explosion in online-search marketing, management wasn’t sure where to begin hiring. They knew they needed people at every level, especially to lead design, sales, and project implementation. And they aimed to create a competent and nurturing atmosphere for the new talent that would be coming on board.

Before recruitment began, they wanted to take an objective look at what strengths they had and what they lacked. Barbara Robinson, who was working in the United Kingdom at the time, gave nine members of the senior management team Birkman assessments. When the team saw the results, they laughed: every one of them was in the far right-hand corner of the Blue quadrant, maybe with some Green sprinkled in, pointing to the strong, creative talent that made them a hot start-up. “They immediately got the picture,” she says. “The founder kept hiring people like himself!”

That one simple and very typical mistake upper management makes is at the core of many corporate woes—from a stubborn lack of diversity in company hierarchies to the kind of stagnant thinking that threatens to sink a business. The one-hire-fits-all mentality is hard to recognize amid a staff of people who tend to understand each other and get along. It can be even harder to correct.

The discussion that followed led them to begin looking first for a chief financial officer. Barbara helped them find a talented candidate who brought to the office some Yellow—a passion for accounting along with a systematic approach to the work. The new employee also had a lot of Blue in her profile, so she could find common ground with her senior management colleagues.

The purchase by the U.S. company allowed a wider expansion, and the recruitment process eventually resulted in a staff of 275. Once the new owners were in place, the founder, who was chief executive officer, left the company, and Barbara worked with the new CEO to reshape the senior-management team.

Notes

1. Shannon Woolard, e-mail to Steve Cornwell, March 2011.