Chapter 8

How Your Emotions Can Help or Hurt a Decision

Empathy and Thought

The stereotype of corporate America is that it is a sterile environment that turns its denizens into robots going about their daily routines with extraordinary efficiency. Anyone who works in an office knows, of course, that it is an emotional, political, and volatile landscape where productivity and efficiency can be derailed by any number of problems.

Understanding how much emotion and how much thought people put into their decision making can help us navigate many of the land mines in that perilous landscape. Empathy and Thought are two critical Components that show us some of the give-and-take that go into how choices are made.

Empathy is about how you are seen expressing your feelings, and it helps you understand how others will express theirs. It can measure how we process emotion, the degree to which we enjoy being emotionally expressive, and how we ultimately are energized by our emotions. The Need score for the Empathy Component is an important window on our behavior and offers a useful way to help us see some critical differences in how we relate to each other. We pair it with the Need for the Thought Component, which measures the speed of our decision making and the amount of detail we want before we are comfortable in coming to a decision.

You may be thinking that you have finally stumbled across what could potentially be a “bad” score! After all, no one wants to be seen in the workplace as a drama queen. But by now you have learned to appreciate the advantages of being at any point on the 1–99 Birkman scoring span. And so it is with Empathy: there is no better or worse way to be. Six decades and several million people in the Birkman database confirm that people fall all along the Empathy continuum and that having a wide variety of emotional responses provides enormous social benefit to us as a society. You can easily understand how having empathy can be seen as a virtue in any setting.

Obviously we all care, and we all have feelings. The Empathy Component is not about whether we have feelings; it is about recognizing our comfort levels with expressing our emotions and how much we enjoy emotional demonstrativeness. The significance here is to be aware of whether a person chooses to heighten and express his or her emotions or would rather minimize and play down those emotions. Our contrasting styles and needs in this area matter greatly in our self-management, relationships with others, and selection of careers.

The Need for Empathy spectrum can describe the more nuanced aspects of our feelings so we can recognize, acknowledge, and understand these contrasts. As with every other Birkman Component, the majority of us fall somewhere toward the center of extremes, but it is easier to talk about black and white than shades of gray. We will look at some extreme examples of Empathy scores to help describe the significance of the Component and point out where the most intense scores might open the potential for tripping up, especially in dealing with people with sharply contrasting tendencies.

ONCE WITH FEELING

High Empathy people are deeply connected to and keenly aware of their emotionality. Employees who rank high on the Component are seen as expressive, enthusiastic, passionate, and more likely to use emphasis and colorful language than is typical. In other words, they can be fun to be around! Any industry can reap the rewards of having such a person on staff who is able to make an emotional connection with clients or enthusiastically warm up a room. In particular, high Empathy qualities can pay huge dividends in activities that are intuitive and performance-based, including writing, singing, speaking publicly, and arguing a legal case.

A high Empathy style also can be volatile, especially when it combines with a high Authority style in Stress mode. Then we are likely to hear a message delivered with a great deal of emotional force and in a loud voice. What is important is to find productive ways to acknowledge the real emotional Needs of the higher Empathy types who want to be heard without compromising the work and goals of others.

The Birkman has the ability to show a deeper view of behavior on multiple levels: Usual Behavior, Needs, and Stress. The potential downside of this gift of emotionality is that in a Stress mode, high Empathy people can feel discouraged or even become depressed. They can more easily find themselves stalled in Stress mode, swamped by their own feelings and finding it difficult to take action. Ironically, taking action or doing positive activity such as physical exercise or helping someone else can be an antidote. It is one of the most effective ways to overcome this kind of emotional inertia.

PLAYING IT COOL

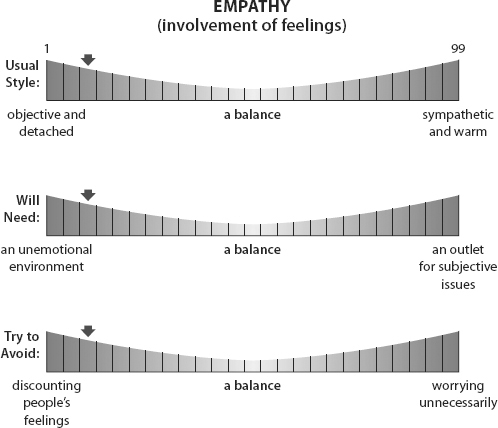

The Birkman also can crack the facade to find where a low Empathy person might be hiding a need for more emotion, that is, a desire for a warm and sympathetic response. You may exhibit a low Usual Behavior Empathy style in your workplace environment, for example, but when you go home, you find you’re able to process your higher Empathy Needs by relying on the sympathetic ear of a spouse or a friend. In figure 8.1, the person would tend to show little emotion with others and would prefer that people also treat him or her in a direct and practical way, leaving emotions aside. Problems could arise if this person were under Stress and became too dismissive of what others are feeling, demanding they just “get over it.”

Figure 8.1 The Empathy Component

Low Empathy people come across as matter-of-fact, logical, and in control of their emotions, sometimes to the point of a certain cool detachment, preferring to avoid what they view as excessive drama. Birkman consultants and other researchers have noted the generational shift over the decades toward more detached outward behavior among those with an MBA, at least in their Usual Behavior but not necessarily in their Needs. Also, although women are often thought to be more emotional, Birkman research shows there is no gender connection with respect to this Component trait.

The gift of the low Empathy approach is the ability to choose to get on with it by offering practical solutions and immediate action to remedy a situation. The lower your score is, the less you need verbal sympathy. In fact, that approach may annoy you and even make you suspicious. For you, it is “just the facts, ma’am,” with little need for sympathy or histrionics. You can see how this quality is essential for those doing work that requires objective responses and quick, level-headed action, especially for, say, airline pilots and neurosurgeons. Most paramedics and emergency medical technicians are low Empathy because they have to detach, even though they are certainly caring, helpful people.

Low Empathy people may clash with someone who isn’t seeking such immediate action but is craving a sensitive ear to hear them out without offering a solution. They may frustrate their higher Empathy colleagues by saying, “Just fix it,” or, “Come back when you’re better.”

HIDDEN FEELINGS

Low Empathy people also care deeply about others and have strong emotions. What Birkman is measuring with this Component is how they choose to deal with those emotions, and the extent to which they let them play a role in their interactions.

One consultant was surprised by how Empathy turned around discussions when she gave the Birkman to six top executives at a Kansas construction company. She was working with the members of the leadership team to ensure their goals and plans of action for the company were aligned so they could work together effectively. Suddenly, during a feedback session, one of the men seemed thrown off by his very low Empathy score—10 in his Usual Behavior and the same for Need. His concerns were separate from anything going on at work, but could be critical to how he kept up his energy and motivation for the job. He had just finished what he referred to as “an ugly and bitter divorce” in which he had partial custody of his sons and was worried this score meant he would have a hard time connecting with them, the consultant says. “He was on the verge of tears,” says Stacey Mason, an Arkansas-based consultant. “If I would have had the stereotypical idea about construction workers, I would have been wrong.”

She explained to the group that the low score was more about how the executive was showing his feelings than it was about what he actually felt. “To have a low score, whether in Usual Behavior or Need, means we show Empathy in a very practical way,” she says. His low scores also meant that he saw himself as “just as emotional as the average person—no more or less,” and, moreover, he wouldn’t stay down if he got a little down.

The man’s colleagues all chimed in and told him that they saw him as kind and considerate. “He got a lot of love,” says Stacey. “They were a close group, but the Birkman gave them the opportunity to have something measurable to guide the conversation.”

They used the Birkman as a jumping-off place rather than as a tool for baring their souls. They reached a level where they got to say what they wanted to say without either posturing or using emotional language.

TOO TOUCHY-FEELY?

It isn’t always the case that your colleagues will be open to discussing your home life in the office or seek to strengthen personal ties. A newly assembled team for a luxury-homes service in Atlanta discovered after taking the Birkman that five of the seven group members had similar Empathy scores: low in both Usual Behavior and Need. One member had low Usual Behavior and moderate Need. The newest member of the team stood out from the pack, scoring high on both.

The overall culture in the workplace was informal, but also rather impersonal in conducting daily work, says consultant Steve Cornwell. They cut to the chase on issues, big and small, typically acting in an objective and practical way.

The one high Empathy team member, in contrast, was very personable, and being new, she went out of her way to be nice to the others. “She would send thank-you cards for little things and never missed bringing a birthday card or making a big deal about special events,” says Steve. “She was the first to say, ‘Good morning’ and ‘Good night.’”

Her extreme cheerfulness rubbed the others the wrong way. They were suspicious of the new employee’s motives and felt her actions were at worst fake and at best showed that she was trying too hard. She could hardly say a word without the rest of the group rolling their eyes, the consultant says. “We don’t like that warm and fuzzy stuff here!” one team member said in a separate meeting with the consultant. “We are all here to do a job, and that’s it. We’re not looking to be everyone’s best friend.”

Steve called a team meeting to review the Birkman scores of each member. He had plotted a group graph that showed each individual’s Needs scores for every Component as a dot labeled with his or her initials. He went through each of the eleven Component scores one by one.

“When we landed on the Empathy Component, it was amazing to see the team’s reaction,” Steve says. They were shocked by how much of a difference there was between the average score and the new employee’s ranking. They also quickly realized how much they had ganged up on her.

“When I explained how this played out, the high Empathy team member exclaimed, ‘Finally!’ with tears in her eyes—no surprise,” Steve says with a laugh. “For the first time, the group could see what she had been up against.”

The team members agreed that they had been too harsh with her on many occasions. They never gave a thought about how their treatment must have felt to her and what the collective impact that had had on her. And because the Birkman always seeks balance, the high Empathy team member also was instructed on how she escalated the problem by not staying objective and practical when interacting with team members who clearly didn’t appreciate her special efforts.

“We were able to talk through how to best work together moving forward,” the consultant says. “By the end of the team session, the group was joking about the differences, and even a few hugs were shared—instigated by you know who!”

THINK ABOUT IT

Low Thought people are speedy decision makers and tend to be proud of that skill. In many aspects of business and government work, the ability to make a decision quickly is highly prized. It is vital for functioning in a just-in-time economy and in times of crisis. But being too impulsive is a danger, especially to someone in a leadership position. It’s the ready-fire-aim mentality.

Meanwhile, due diligence is a good thing, but overthinking can shift from prudent caution to outright anxiety, especially in the workplace where a staff member is waiting for directions to proceed with the task at hand. If you rank in the middle of the spectrum, it means your decision making may be fast at times and slower at times—in other words, dependent on the situation or circumstances. Midrange scores in general tend to be less of an issue for most people. Sometimes you might overthink, and sometimes you’re quick.

One San Francisco employee found his job on the line when his boss viewed his rapid decision-making style as reckless. The man was a treasurer in a large mortgage firm. His boss, an executive vice president, was sure the controller wasn’t doing sufficient due diligence on important decisions and began to consider replacing him with someone who would be more careful.

The boss called in consultant Claire Carrison, who had experience coaching many executives away from the extreme edges of the Thought spectrum. She advised him not to make any final decision until both he and the treasurer took the Birkman. “Let’s see if we can get a better picture here of what’s going on,” she told the anxious executive.

As she suspected, the Birkman showed the vice president had very high Thought scores—in the 90s—for both Usual Behavior and Need and took his time in reaching every decision. That made him suspicious of any one of his reports who didn’t go through the same long and detailed process. His treasurer had lower-than-average Thought scores. In Claire’s deeper discussions with them, she learned the treasurer hadn’t actually made any wrong decisions, but simply had created that suspicion because of his style of working. “Once the EVP saw the numbers proved their decision-making styles were at polar opposite ends, he understood it was not about wrong—it was about different,” says Claire. The treasurer’s job was spared.

ANALYSIS PARALYSIS

Many bosses are plagued with extreme behavior at the other end of the spectrum—being stymied by anxious overthinking of every decision. Nancy Thompson, a Birkman-certified coach at Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati, learned how disruptive the analysis-paralysis executive can be when her company was consolidating job responsibilities for its logistics group.

She conducted Birkmans with the whole logistics leadership team. One member was known to be a foot dragger at meetings and the Birkman showed why: he had a high Usual Behavior score of 92 for Thought, whereas the rest of the team ranged between 6 and 18. The high scorer liked to talk—and talk and talk—through all the details before making a decision.

“I had observed many times how Alex [not his real name] would derail a meeting with long, circular discussions of what everyone else had already said,” says Nancy. “His reputation was known to most people, and they would disengage immediately when he started talking” despite the fact that he was knowledgeable and had concrete and valuable contributions to make to the discussions.

Nancy decided to use a visual exercise as an icebreaker. She had the team use exercise stretch bands to illustrate just how different Alex’s thought process was from everyone else’s. She wasn’t that optimistic about how the session would play out, she says, given the entrenched habits of the team and the hostility that had already built up. But the visual device worked. Alex’s colleagues saw the sharp contrast and became suddenly sympathetic to the nature of their colleague, and Alex saw just how taxing his process was to the office environment.

Alex was quiet for much of the day during the Birkman sessions, resisting his usual urge to restate everything everyone else said. Finally, he held up his hand and asked, “I know I am usually the ‘hitch in the get-a-long’ and I promise not to do that, but could I just step in here and say a few words?”

Everyone stopped writing and put pens down and turned to face him. The room listened courteously and attentively while Alex spoke.

“Those with the low Usual scores had recognized how to be respectful of Alex’s style,” says Nancy. “I am going to guess that this was the first time in years that Alex was able to command that kind of attention.”

After several minutes, Alex said, “Okay. That is what I wanted to say.”

From that point on, the consultant says, he never again resorted to his former, painfully detailed speechmaking.

ROOM TO PONDER

The Thought Component was also significant for Bayley Kessler, a Lacey, Washington, entrepreneur who had been trying to launch her own florist and jewelry-making business for some years. Her Birkman revealed clues as to why she was having such a hard time advancing: her Thought score topped the charts with a high 99 in Usual Behavior, and her Need score was also high: 84. “Such a high score is super-thoughtful—not demanding a decision,” says Jenny Capella, a consultant who also happens to be Bayley’s sister and welcomed the opportunity to use the process to strengthen family bonds.

Whenever Bayley had to ponder a question or respond to a request, she often would fall silent. Jenny would mistake the silence for confusion and begin to offer more and more information, which drove her sister into deeper stress and even more analysis paralysis.

After getting her Birkman feedback, Bayley realized she needed plenty of room to think and began to ask for the time she needed to make a decision. “Now we have an agreement,” she says. “When Jenny asks me a question, I say I am “99-ing it (because of my high Thought score). She now knows that I am thinking and doesn’t feel compelled like before to give more information because I am not answering her right away.”

Both sisters were surprised that Bayley also had a very high Usual Behavior score for Empathy and a much lower score for Need. The Usual Behavior made sense because of her empathetic nature. But when Jenny tried to support her by being strongly sympathetic if anything went wrong, Bayley would get frustrated.

“What she needed was logic—grounded, practical logic,” says Jenny. “All those years of misinterpreting her actions!”

With those pieces of information, Bayley has become more confident about her business acumen. “Knowing so much more about my process, I can talk about my business with greater confidence,” she says.

Also giving her confidence were her art and mechanical scores—both very high—showing that her combination floral and jewelry designer business made perfect sense.

The transformation, says Jenny, was startling. “It was dramatic, and it remains dramatic to this day . . . She is flourishing, doing things with her own steam and on her own time.” That transformation also helped the sisters nurture their own relationship.

FAMILY TIME

The Thought process as measured by the Birkman Component can play a role in everyday activities and relationships. Ron Baker of Ontario was able to show a couple—Dr. Ervis Duardo Perez and his wife, Tamara Pina—in a social setting how the Thought Component works.

“How he makes a decision was a main point,” says Tamara. “In a crisis, I have an idea, or a decision, for the moment. Ervis takes a long time to make a decision, but once he does, nothing can move him. I’m quicker, but I can change my mind.”

In Birkman language, that meant he scored high for Thought in both Usual Behavior and in Need. “It’s behind-the-scenes deep thinking,” Ron says of Ervis. His wife was low Thought.

Ron laughs about going out to dinner with the couple after one session. “In sixty seconds [Tamara and I] had our order ready,” recalls Ron. “Ervis sent away the waitress when she came. Then he sent her away again. Then he sent her away again. I said, ‘Do you see how this works?’”

THE BIRKMAN AT WORK: THE GLOBAL WORKPLACE

The Birkman Method is helping to change the discussion on integrating the global workplace, aiming to focus less on cultural differences and more on individual similarities. People are more alike than they are different. Put another way, the differences among individuals in any particular nationality are much greater than any differences among nationalities.

Yet issues of diversity get complicated on a global level because of the sheer breadth of diversity and because we have to recognize and be respectful of different customs and learned behavior. Failing to factor in these differences can trip up people trying to do business or get a job in places that are unfamiliar.

Birkman’s database of more than 3 million test takers in twenty-two languages from fifty countries confirms that test results aren’t that different from country to country. The differences that we expect to see and that show up in results tend to be in the visible, Usual Behavior, more than in Needs, Interests, or Stress. The differences we have to acknowledge are how those results are interpreted. We have discussed the “easier to dish out than to take it” score (low Usual Behavior, high Need in the Esteem measure of one-on-one communication). That score is more common in North American profiles, where being candid is taught and direct language is prized. In other cultures, where people might be expected to speak more carefully and respectfully to others, Usual Behavior typically shows up as less direct, though Needs will be the same. There are many such cultural differences.

A Focus on Culture

Tasneem Virani, a consultant in London, likes to coach “people as people,” she says. She believes the variety of experiences and cultures that so many people are exposed to in today’s increasingly connected world makes it harder than ever before to label people. To understand how complex personality and culture can get, she uses the example of her own family: she is an ethnic Indian born in Kenya who studied in England, where her children were born. But the family then lived in the United States, where the children continue to reside. “I can’t say they are like me,” she says of her children, “because they have more the culture of the United Kingdom, Europe, and the United States, so they are the third culture. If you look at all that, you just have to look at them as human beings.”

It gets just as complex in her work. About 75 percent of the coaching she does involves people who have settled in the United Kingdom after living elsewhere in the world—sometimes making more than one stop along the way. “Their values are different, but their personalities speak the same language,” she says.

That is, she can verify that few differences among cultures show up on the Birkman, with the exception of some similarities within nationalities in people’s Usual Behavior—their learned expressions of certain values and traditions. She finds, for example, that people of Indian, Pakistani, and Middle Eastern backgrounds, among others, tend to have Advantage scores that are low Usual Behavior. They are relieved when their personal demands appear to be modest, Tasneem says. In the same vein, they can be self-conscious when they get a high Need for Advantage score and have to own up to wanting material rewards for their work. To break the news to them about their high score, Tasneem says, she explains to them: “You want to be acknowledged for your work and to know that there are other opportunities for growth.”

Tasneem found, however, that even strong cultural values can take a backseat in a workplace environment that is seen as falling short of expectations. She was hired in 2012 to help 4C Hotels Group, a family business based in London, through its corporate relaunch and planned expansion. The family is ethnic Indian; the founding partner was born in Tanzania, and his son was born in the United Kingdom.

Most of the staff of 150 UK employees were recent immigrants from around the European Union and Southeast Asia. Their entry-level jobs in the company, as in the industry as a whole, tended to be low paying, and the employees were getting frustrated over a lack of opportunity. “You could see the problem in recruitment and retention,” says Al-karim Nathoo, associate director at 4C Hotel. Turnover was high.

As might be expected, of the twenty who took the Birkman—most from India, Pakistan, and Romania—eighteen showed low Usual Behavior scores in their Advantage Component, which Tasneem says made it easy for them to work for the benefit of all rather than for themselves. But far from being apologetic about their high Needs scores, the employees embraced their wish for rewards for their work. And they let it be known in subsequent discussions that they needed a clearer path to job advancement. Tasneem also saw through the Birkman that many staffers ranked high on the Empathy Component in Need for emotion and expressiveness; in fact, they told her they felt they weren’t getting enough feedback from management about their work and didn’t have outlets to express their opinions.

While some of the employees wondered if their experience was because of their status as new arrivals in the country, the real issue turned out to be related to corporate culture and had nothing to do with nationality. “There was not a defined culture in the company,” says Al-karim. He didn’t want such issues to weigh on the future growth of the business. His family was hoping to expand their ten-year-old company into East Africa, he says, and to build new properties. His father, a founding partner in the company, already had expanded the business from a small bed-and-breakfast concern to one that owns ten budget and midmarket hotels—brands such as Holiday Inn Express and Comfort Inn—with shares in similar concerns. “But our processes are still toward mom-and-pop business, and we want to strengthen operations, and focus on human resources and leadership development,” says Al-karim.

Tasneem says Al-karim’s high Interests in Social Service told her he was sincere about wanting to help his employees and improve their career development, as well as to boost his customer-service performance. The other top managers’ Birkman profiles showing a desire to work for the good of the whole, she adds, meant they also could take the steps needed to change the core business culture.

They acknowledged they had to address the company’s narrow bench at the upper ranks in terms of variety of work strengths. “We are very numbers oriented, but we don’t have a lot of strategic thinkers except for my father and me,” says Al-karim. “To grow, we need to bring in other types of people, especially in the sales and marketing side and the softer skills in communication and sales.”

To the director, it was clear what the next stage should be: development for those identified on the Birkman as needing training. With Tasneem’s help, they began to outline training goals aimed at improving leadership and management skills. “We defined the values and mission of the company, which includes them being more customer focused,” Tasneem says. “The key is really to help us all to become more emotionally intelligent by increasing our self-awareness of cultures, of values, but also of personality. Then you understand what I’m feeling and get to know me, my values, and my culture.”

Same Score, Different Meaning

Stephan Altena, a Munich-based Birkman consultant and executive trainer, tells of when he gave Birkmans to an Italian team. As they went over the feedback reports, he pointed out someone in the group who preferred working alone. In the United States, such a preference would barely be noticed, he says. Colleagues would think, “That person likes to work alone. Okay.” But in Italy, the employee’s teammates were puzzled. It raised suspicion, and the employee’s closest colleagues were a little hurt, if not insulted. They asked Stephan to explain: “Why does he want to work alone? Doesn’t he like us? Is something wrong?” It was a score that could offend in a culture that emphasizes community and close personal relationships. Scores can be identical, but how they are seen and accepted may change with the cultural context.

Jan Brandenbarg, a senior consultant in the Netherlands, describes an instance in which he was sitting next to a Japanese man who had the same Birkman score as he did for candor and directness: low Usual Behavior for Esteem. He told the other man he was surprised because he seemed to be very careful in how he communicated. “He replied to me, ‘You should hear how my colleagues speak of me as being so direct; even my mother says so.’” The source of the differences is complex, Jan adds. “It has a lot to do with tradition, history, and also with things such as mental programming—which happens when we are young—and history and values. The range of scores is very similar, but the interpretation is not.” He sees Authority as one of the Components that has to be closely examined when dealing with multicultural issues, as he often does in his company. He has clients across Europe that can have a single C-suite line-up with nationals from the Netherlands, France, Germany, Belgium, and Poland. Different cultures generally have different levels of respect for Authority and different ways of showing that respect, he says.

Jan, who bases his opinion on the work of Geert Hofstede, the Dutch researcher on culture, considers the acceptance of authority a measure of the distance of a person to the center of power. For example, the distance between the power center and its people is much greater in China than in Northern Europe. The Dutch, Jan says, feel strongly about their standing in corporate and other hierarchies. They say, “You may be the manager, but as a person, we are equal.” So you get a strong sense of an egalitarian playing field. In China, a person may be less likely to see an authority figure as an equal. “I interpret the Birkman scores in that light,” Jan says.

Your New Boss

Some people are surprised to find that a corporation—an entity they think of as a place lacking in culture and custom—can be faithful to the culture and traditions of its own or its host country.

Tony Swift, general manager for human resources at Hyundai Motor Co. in Sydney, Australia, helped one employee who was having a hard time getting his career started in the marketing department of the Korean-owned company. The new hire, an Australian, was seen as uncooperative, “a cowboy,” Tony says. He wasn’t fitting in to the company culture, which is very hierarchical.

“Here, when things are asked for by a deadline, they are done. End of story,” says Tony. When he gave the employee the Birkman, it showed he had a very high 98 score for Freedom, signaling a strong need for individual expression, and his Structure Need was low, meaning he didn’t like to have a lot of rigid processes to follow.

“It was a light-bulb moment,” says Tony. “He said, ‘Now I get it and understand the problem.’” But it did raise the question: “What was he doing in a Korean organization that is very structured, process oriented, and hierarchical?” He was given a course of action and the opportunity to try to adjust to the corporate culture, but ultimately he decided to find a company culture better suited to his personality.

Seeing the Individual

Heifer International staffers were concerned about issues within one of its leadership teams in southern Africa. The global nonprofit, based in Little Rock, Arkansas, helps communities fight poverty and hunger by giving gifts of living animals along with training that families use to improve their lives.

On the team were four individuals from two different regions, says a manager, who asked that the country not be named. Heifer International had successfully used the Birkman to address differences between staff members in the United States, and it hoped it could be a valuable tool elsewhere.

When the four members of the team took the Birkman, results showed the team leader’s style was to be very frank and direct. In fact, he registered about as low on the Esteem scale as possible—a 3 Usual Behavior and a 3 Need! The rest of the team had much higher Needs (79, 79, and 44) for personal and supportive individual contact. “The team leader also tested a low Needs Acceptance style, or low sociability, so he saw no reason to extend personal encouragement to his staff. He thought it was fine to communicate only by e-mail,” said Heifer’s manager of talent development, who gave Birkmans to the team. “He meant well, but his detached impersonal style left his colleagues—with their significantly higher Needs for Esteem scores—feeling frustrated, unappreciated, and generally disconnected from him.”

Staff members at headquarters validated from personal knowledge that the Birkman reports were “right on.” The Birkman was able to highlight some of the reasons behind the problems within the team.

While ethnic and cultural differences may have complicated things, reported the talent development manager, “the team was also challenged by their communication habits and personal styles.” Identifying their needs early on may have helped them understand that their differences aren’t obstacles and that these different personal styles can actually be the foundation of a successful and productive team.

The Birkman gives people from different cultures and countries who must work together a good place to start to find common ground and a good way to reject simple labeling. The neutral language allows them to examine themselves and come to terms with behavior and expectations that aren’t their own.