Chapter 4

Your Communication Comfort Zone

Esteem and Acceptance

The Birkman starts with the two Components that best express your tendencies regarding communication, the bedrock of effective leadership and of good business in general, no matter where you are in the hierarchy. It is hard for people to develop trusting relationships without good communication skills. But even the most articulate employee or boss may come across as uncommunicative when clashing with the styles of others at work. Most people are well intentioned, but without some assistance, it’s hard for them to see something from another person’s perspective. In this way, an objective metric such as the Birkman can be helpful.

The assessment takes an analytical look at your communication style by measuring two Components that relate to our social styles. Birkman calls these our

- Need for Esteem (relating to individuals)

- Need for Acceptance (relating to groups)

With this pair, as with Components in general, scores will trend toward either extroverted behavior (on the Life Style Grid it is represented in the area at the top) or introverted (bottom of the grid). In terms of communication, the Component rankings for extroversion would show a low Esteem score and a high Acceptance score. Conversely, those with higher Needs for Esteem and lower Needs for group Acceptance or sociability will trend toward introversion and show up in the lower part of the Life Style Grid.

The Esteem Component can be the harder of the two to interpret, and the word itself may throw some readers because it has nothing to do with the notion of self-esteem. What it does address is how diplomatically and respectfully you prefer to deal with another person one-on-one. Other words might be candor or frank directness to describe the low scores and careful and cautious sensitivity for the high scores.

The Acceptance Component addresses overall sociability. It is Birkman’s measure of your desire and tolerance for larger group gatherings. Conversely, it suggests how much alone time you need to recharge. You may show up as outgoing, gregarious, and highly entertaining in group social interaction, for example, yet you need to restore your energies by being alone or relaxing with just one or two people close to you.

Vancouver consultant Jonathan Michael has a sky-high Usual Behavior score for Acceptance of 99, coupled with a 10 ranking for Need. “I look like a people animal, but I’d rather spend alone time with my wife,” he says. “I need my cabin in the woods and being by myself or with my wife.”

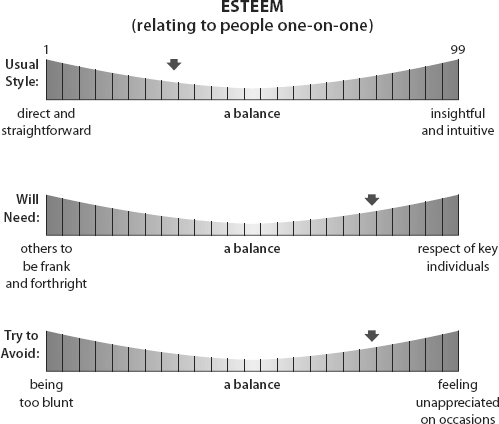

The low Usual Behavior/high Need combination is a common Esteem score pattern (figure 4.1). It represents people who tend to be direct in their speech but prefer a response that is tactful and respectful. In other words, they can dish it out, but they can’t take it. This can be a sticky combination if the person who is dishing it happens to be the boss. If a direct report abides by the Golden Rule and assumes the boss likes it back just like he gave it—frank and direct—the report may get in trouble for his candor, which the boss will likely hear as blunt and disrespectful.

Figure 4.1 The Esteem Component

Thus, the Esteem score also shows just how hard it can be to send out the right signals as to how we need to be treated. Speaking bluntly to someone may not be the best way to get that person to speak gently and tactfully to you if you have a higher Need for Esteem. At the other end of the spectrum, a person with a lower Need for Esteem may prefer a direct, candid delivery and will get uncomfortable, even a little suspicious, if the message is communicated with an especially soft sell.

One senior-level professional in health care in Houston had a typical low Usual Behavior score (31) in Esteem with a high Need score (79)—the “can dish it out, but can’t take it” score. He had always worked independently, but after going through a series of promotions had ended up in charge of a team of five direct reports and working on a huge project. It was his first management post. “He was a nice guy with a good heart but very exacting,” says his consultant, Phillip Weiss, also of Houston. “He continued to deliver high-quality work, but with a team, he felt he lost control over quality.”

Phillip says much of his consulting work is helping executives set out on a leadership path to get “from point A to point F” at a higher position and at a higher level of functioning. The questions these executives typically ask are: “What behaviors do I have to do to get there? What behaviors will trip me up?” In this case, the executive was acting out under stress, poisoning the work climate, and tarnishing his hard-earned reputation. He would get angry and snap at his reports—behavior he had never been known for before this latest promotion. “It got really bad,” Phillip remembers.

Phillip used the Birkman to look at the major categories of behavior the executive needed to consider, with a focus on communication. He told his client to think of the Birkman as an iceberg: Usual Behavior is the part we see, Needs are what are under water and so not always known, and Stress is a poke of the iceberg that sticks out of the water and becomes visible when Needs are not met.

The Birkman revealed a low-high Esteem score coupled with high Usual Behavior (74) and high Need (92) scores in Acceptance that made the health care executive feel the pressure to confront his team aggressively and in an effort to hold them to his high standards and please his senior managers.

As soon as Phillip handed his client the Birkman, the executive began to feel relief, he recalls. “It seemed to give him permission to be who he was and own it,” says Phillip. “But he also knew that some of these tendencies were not helping him.”

After the executive got a clear view of his behavior, he started to treat his staff better. He went so far as to apologize to several key individuals and then began to calm himself, becoming less demanding and more supportive of those who were delivering good work.

GLUED TO COLLEAGUES

Having a high Esteem Need score (90) and an equally high Acceptance Need score (90) was keeping one woman in New Jersey stuck in her job as director of information services, which she felt she had outgrown. As her Birkman scores would suggest, she had developed a strong attachment to a few of the individuals at work, as well as to her team, and she couldn’t bring herself to move on. The big pharmaceutical company where she worked, however, had a culture that was completely antithetical to what she needed, which was appreciative and respectful recognition of the contributions of her and her team. The conflict was putting her in constant stress, especially because, as her Birkman also pointed out, she was very self-critical: she blamed herself for her problems and so was insisting on trying to make the job work against all odds.

The Birkman helped her see what was holding her back. “She didn’t want to lose the one-on-one relationships she built in the office,” says her consultant, Barbara Robinson, of Washington, “or the strong relationships she had made with her staff and her division. She also wanted to achieve the ambitious goals that she had worked hard to put in place for her staff, but the changes in the company made it clear that she would not be able to do so.”

After three years of coaching, she finally came to terms with the fact that she could never change the organization to suit her needs or get it to value the goals she wanted to achieve. Instead, she landed a new job, in a more senior position at a comparable company that built on her strengths and valued her commitment to teamwork.

NO DRAMA, PLEASE

Todd Uterstaedt had a client at the opposite end of the Esteem spectrum, a manager who had been executive director at a Cincinnati, Ohio, hospital for fifteen years. She was feeling increasingly frustrated at work and had begun to break down in tears in front of her colleagues. She complained that her strengths weren’t fully leveraged or appreciated, and she didn’t feel she was getting adequate resources to do her job. The organization, in fact, saw her as highly competent. Her superiors wanted her to assume a greater leadership role if she could resolve what was troubling her about her job. Todd was hired to help her find what her next level of work might be.

Surprisingly, her Birkman revealed that her outbursts weren’t because she was overly sensitive. In fact, the opposite was the case: she had an intense need for an emotionless and objective response from the people around her. Her high Usual Behavior score for Esteem (79), and the caring rapport with individuals that suggests, led those who had to deal with her personally to see her as diplomatic and understanding. They felt comfortable opening up to her about everything that bothered them on and off the job. Her low Needs score (9) in the same Component, however, told Todd that the executive just wanted people to do their jobs, skip the drama, and not bother her with “the messiness of all these emotions” they had been pouring out to her. Too much overt sensitivity didn’t mesh with her Needs and, in fact, kept her stressed. When the manager got upset, others—as might be expected—took it as a signal that she needed to be coddled and “that just made matters a thousand times worse,” says the consultant. The response pushed her to ever more emotional outbursts.

“Can’t everyone just do what I tell them to do?” the director joked when she read her Birkman report. Some months later, the woman moved into a significantly more responsible position at another hospital and told Todd that the new culture was “meeting her needs” and offering her the opportunity to grow professionally. She was happy, she said, and making an impact at her new job.

NO CHIP OFF THE BLOCK

When two opposing Esteem and Acceptance profiles have to work together, they can be a good complement for the other’s style, but things also can get complicated when they don’t realize how different they are and how to approach the other. It can get more complicated still when the difference happens to be generational as well. Consultant Dana Scannell was called in to help a father and son in business together work out their opposite Esteem and Acceptance scores.

The business was a successful family-run real estate company in California, and the father, the head of the company, needed help with his heir apparent. The son thought of himself as a chip off the old block, but the father knew the truth: they were direct opposites.

It didn’t help that they also had very different color personalities. The father was “Green, Green, Green—could sell ice to an Eskimo,” Dana says. He was self-made and old school, the type who could walk into a room and have everyone laughing at his (sometimes off-color) jokes. The son was Blue—artistic and sensitive and mild mannered, and embarrassed by much of his father’s patter. “He was the antithesis of what his father wanted him to be and what he [the father] was,” the consultant adds.

Both father and son had similar Esteem scores on Usual Behavior and Needs and did well in one-on-one situations. However, in Acceptance, while both had high Usual Behavior scores, seeming at ease in front of groups, their underlying Needs were totally opposite, and that led to conflicts in decision making. The son, with his high Acceptance Need, felt everything he was involved in required group consensus, and the father, low in Acceptance, was annoyed with what he interpreted as his son’s inability to make a decision on his own. The result was significant frustration for both of them. The problem was put in clear focus when the assessment exposed their contrasting underlying Needs. Once they understood that difference about each other, they were able to capitalize on their diverse styles, avoiding the misunderstandings that had characterized their work. By understanding and learning to appreciate their differences, they changed the tone in the office and, more important, saved their personal relationship. As a result, the father became such a fan of the assessment that he had all of his employees and candidates for jobs take it.

NOTHING PERSONAL

C-suite executives with across-the-board low sociability (Acceptance) scores were alienating their employees at one big multinational company because the bosses’ behavior came across as gruff and detached. Their staff thought they didn’t like them, which made the employees avoid any encounters with their bosses, creating a work atmosphere of exclusion, says consultant Philippe Jeanjean of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The consultant helped the employees see that the issue wasn’t personal. It was not about them or their performance. What it was all about was a difference of perceptions.

SEEKING ALONE TIME

Randi Gregoire of Orlando, Florida, learned how to negotiate her Acceptance score gap of a very high 99 in Usual Behavior and a low 11 Need, meaning that although she seems to be sociable and happy to be in large groups, she needs some significant time alone to recharge. “I show up as an extrovert, very friendly,” she says. “I go into a room and seek out the strangers and try to get to know them. But in my heart of hearts, I am an introvert.”

When she was working in East Asia, leading an English-language workshop, she always asked to have a room to herself, no matter what the cost. “I learned that if I wanted to be able to be with people all day, teaching and leading a team, then I had to retreat at night to regroup and reenergize,” she says. “I always knew that this was true about myself, but the Birkman explained why.”

It’s often hard for others to understand. In the evenings after work, when her colleagues began to socialize and play games, she would tell them she had to go home. “Why are you leaving?” they would always ask, perplexed. It worked the same way at home. Once her husband was preparing to go on a business trip, but at the last minute came home from the office and announced it had been cancelled. She couldn’t hide her disappointment and told him she had been counting on alone time. He told her: “I’ll go to the office and you can stay home and be alone.”

“He knows my score, so he didn’t take it personally,” she says, laughing.

To complicate the issue of a high Usual Behavior score with a low Need Acceptance score is the fact that many of the people with these profiles still want to be invited to join the party—even if they are choosing not to go—and sometimes push themselves to maintain their reputations as being outgoing. Because he was so gregarious at work, one Birkman client said he constantly got invited by his colleagues to go out after hours. He would tell everyone that he was going, but then he wouldn’t show up, says consultant Janice Bergstresser of Coatesville, Pennsylvania. “He actually wanted to be invited,” she adds, “but at the end of the day, he just wanted alone time. The Birkman showed his colleagues that he wasn’t being two-faced or difficult and that he wasn’t mad at them. It was just his personality.”

THE BIRKMAN AT WORK: COUPLES COUNSELING

The connection between our relationships at work and the ones we maintain outside the office is a strong one because we tend to repeat the same patterns of engagement with others. It isn’t unusual for Birkman takers to ask for the assessment to be given to their spouse and the rest of the family. Similarly, therapists of all types, from marriage counselors to life coaches, are making use of instruments like the Birkman Method. They see these as reliable in assessing a conflict and understanding the individuals involved, who are otherwise simply asked to self-diagnose their issues.

The Birkman has been used for work with couples since the 1960s, when Roger Birkman held small group sessions he called discovery groups for the First Methodist Church in Houston. The Birkman is not recommended for counseling troubled marriages, but it has been used by dating, engaged, and married couples to help them see potential trouble spots and “to make good marriages better,” says consultant Bob Bolling of Houston.

Bob started couples coaching in 2007 when Chapelwood United Methodist Church in Houston allowed him to offer it to the congregation. Some forty couples signed up when the minister announced it. The consultant believes the assessments can work best for people married five to ten years. After that, he says, children and accelerated careers tend to make marital issues all about a lack of time, which also means there is little room to work on the marriage itself.

Bob finds that the Esteem Component often “is the biggie” in such counseling. If both people are low Usual Behavior and high Need in Esteem, they are going to be very frank in their speech to one another, yet each of them wants to be handled more gently. And although the Birkman doesn’t endorse anyone identifying a gender-specific trait, it’s safe to say that, anecdotally, many male clients have been overjoyed to have such Esteem scores explained. “If he says, ‘I don’t like that dress,’ and she says, ‘I don’t care,’ guess who gets their feelings hurt?” Bob asks.

Karyl White went through couples coaching with her boyfriend, Charles. They both had been married before and went to Bob to see what they could learn about building a successful relationship. She had taken the Birkman twice at work but said she didn’t really appreciate the breadth of the report until she took Bob’s six-week couples course. “It was fabulous for us, and it really accelerated our relationship,” she says, adding that they were married shortly afterward. “By having the results charted against each other, it took all the emotion out of the differences in our personalities.” Their sociability scores showed clearly Karyl’s tendency to be extroverted, while Charles is an introvert. Karyl’s Esteem scores are 6 Usual Behavior and 6 Need, while Charles’s are 21 Usual Behavior and 94 Need. Acceptance scores are also the opposite: Karyl is 98 Usual Behavior and 92 Need. Charles is 17 Usual Behavior and 17 Need.

With such high Acceptance scores, Karyl learned that not being able to interact with others could trigger Stress behavior, where she finds herself becoming overly sensitive. She even nicknamed her stressed-out personality: “‘Karyl Ann,’ which is what my mother called me when she was mad at me,” she says with a laugh. To avoid the stress, Karyl and Charles have agreed to plan one fun social event that involves other people over the weekend. Otherwise she socializes during the week. Her husband lets her know when he feels their social schedule is getting too full. “I respect his need for alone time because it is so obvious how much it revives him,” she says.

A Couple Once More

The Birkman also helps couples move into the phase of their lives where they are just a couple again, Bob says. Edward and Suzanne A. Davis were married thirty-seven years with grown children when they joined the consultant’s couples circle. Bob’s first impression of the two was that “they are polar opposites” because she was so extroverted and he was introverted—but their Birkman showed them to be very similar.

For both of them, the Birkman showed a high Outdoor Interest score. That was no surprise, but its importance as a way for them to recharge and restore themselves was. It came just as they were considering a possible second home. “So it gave us the confidence to buy a place along a river surrounded by nature and near our grandchild,” Suzanne says.

For many couples, discovering their partner’s likes and dislikes comes as a surprise. “You’d think after a number of years together, people would know their partner’s Interests,” Bob says. “I tell couples to guess the highest two and lowest two Interests off the Birkman list. I can count on one hand among hundreds of couples the number who got that right.”

And you might think the partner with the higher Numerical and Clerical ratings would handle the money, but that’s not true, Bob adds. “I often find couples determine whether the husband or wife does it because of their work schedules or something like that.” He then laments, “And doing the wrong tasks is always stressful in a marriage.”

Season of Happiness

Bob and Carleen Woods also were married thirty-seven years and joined Bob’s group in part, they say, “to erase the stigma” that entering counseling means a marriage is in trouble. “We tend to learn about family and careers, but marriage is something we don’t study,” says Carleen. “We are retired, and we thought if we’re in this season of our lives and if we’re not intentional about what the time will look like, we could be headed for something other than a season of happiness.”

Both agreed that the sessions helped them become more respectful of each other and each other’s wishes. The consultant says possibly the most valuable lesson couples learn is the simple fact that their spouses are different from them in many ways and that those differences don’t matter when understood.

It’s the Thought That Counts

Ron Baker, a senior Birkman consultant for the Western Ontario District Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada, finds that no matter how long a couple has been married, they can often misinterpret the motivation behind routine behavior. “I had a couple who wanted to get to know each other after being married for more than twenty years,” he says with a laugh. “After I did the ninety-minute debriefing, she said [to her husband], ‘You know, for the past seventeen years I thought you were being a jerk. Now I know it’s just your personality!’”

When individuals understand the other’s uniqueness, he says, they can compensate for these differences and even enjoy the humorous side to them.