Chapter 3

The Components

Eleven Personality Markers

The Birkman addresses the vast sophistication of the human personality by looking at each individual as a puzzle. Picture a jigsaw puzzle that is a portrait of your face. No one piece of the puzzle gives us all your features, but added together, piece by piece, we begin to see a complete picture. The Birkman divides our behavioral patterns into manageable pieces that make our personalities easier to comprehend. The most critical of these pieces are the eleven relational Components.

In a full Birkman report, the responses to the assessment you took as part of this book are analyzed and your scores are placed on a spectrum for each of the Component aspects. Taken as a whole, these aspects will help you put in priority order your strongest attributes and motivations. These strengths have to be well defined and nurtured, and you have to recognize what they are and when they are not performing at their best, or your strongest talents can be your undoing.

Birkman assessment takers who pursue the full report find themselves keeping their Component results at their desks as a reference for self-management for the length of their careers.

Regardless of whether you pursue your own full Birkman Component profile, however, you will find in the following chapters useful information about how some critical parts of your personality can affect your relationships inside and outside the workplace.

The eleven Components named as relational Needs are

This spectrum (ranging from 1 to 99) provides a view of the overall continuum of normal socialized behavior. No single Birkman Component should be viewed in isolation. Two or more Components can combine to ramp up and intensify certain behaviors, or they may combine in such a way that they will tamp down certain tendencies. For that reason, the relational Components in this book are mostly paired by topic, although an experienced consultant knows how to analyze the interplay between all of the Components. Looking at the Component scores we ask: Are the scores low? Are they high? Which are higher? How wide is the gap between the scores? Viewed together they give an accurate personality portrait.

We provide examples of various combinations throughout the chapters that follow. Our purpose here, however, is to give you a basic understanding of the characteristics observed and how awareness of them can make your work life easier; it is not to train you to become expert in analyzing the assessment results.

Components can be invaluable tools in hiring and promotion. They are used to match candidates’ attributes to job requirements as a way to bolster, but not replace, the résumé and interview process. Is it a position that requires high activity? Would it need a deep thinker? Would it require regular communication with groups of people?

Peter Capodice of Sarasota, Florida, posed those and other questions when he was asked to help fill a top seat in the restaurant franchise industry in Tampa, Florida. He was aiming to use Components to find the best possible candidate but also to be more predictive about whom he hired. The bigger question he was considering was: Is there a way to identify someone as a likely successful choice that would stay in the position for the long term?

Retention is one of the most critical issues in business, especially in big corporations, which can spend hundreds of thousands of dollars searching for an executive and then find themselves spending the same amount again when the person doesn’t work out. “In hiring, some people are great at putting on the show, but ninety days later, the show changes,” Peter says. “We wanted to learn how to strip away interview behavior and drill down to see what really moves the individual.”

The Components helped him to go beneath and beyond Usual Behavior that is visible to the public, to show relational Needs and work motivations. For the client, he crafted a model designed to predict and prevent hiring an incompatible candidate. If there were more than ten differences between a candidate and the job requirements, the hiring team deemed the application unworkable. Let’s say the candidate is direct in communication but the job demands more indirect communication. That’s difference number 1. Then it happens that the manager that the new employee would have to deal with is extroverted and the candidate is introverted. That’s difference number 2. The job duties require someone who is highly organized and the applicant is spontaneous. That’s difference number 3. And so on.

Some differences, of course, can be easily solved and therefore tolerated. Peter recalls one instance during work with a company in Boston in which he was comparing the chief development officer, who had a high Artistic Interest score of 91 and was a stickler for presentations that were aesthetically pleasing, with his vice president in charge of franchise sales, who was “a bullet-point kind of guy” with a mere 18 Artistic Interest. The company made it work by teaming the vice president with someone who could turn his PowerPoint “into something presentable.”

For the top restaurant franchise post, Peter turned to his firm’s large database of a few thousand franchise executives garnered over his years of consulting, which he used as a kind of matchmaking service between major franchises and possible candidates. He found a successful candidate, who was a highly experienced executive, he says. This person showed no significant Component differences between himself and the CEO, and at most two differences with any of the four other executives on the hiring team. He also had the unique qualities of being a strategic thinker and had the ability to execute a plan—both attributes the Birkman highlighted. As of 2012, this person was doing well in his new post. “The beauty of the Birkman,” says Peter, “is that it shows that people are all very different and that some can fit into a culture and give the organization what they need to learn and grow.”

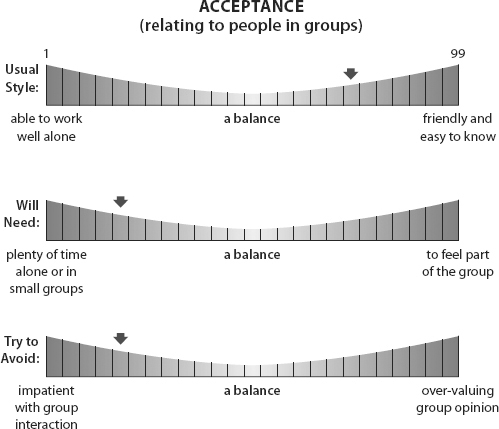

Figure 3.1 The Acceptance Component

USUAL BEHAVIOR, NEEDS, AND STRESS

In the previous chapter, we introduced your Interests and the three basic aspects of your personality that Birkman addresses. The Life Style Grid Report presents them as an overview and an overall summary of all your responses to the assessment. Now, as we look more closely at the Components, we come back to these three important dimensions and show you in greater detail how these relational Components influence our everyday lives.

Each Component result on a full Birkman report is illustrated as a point on three bars, scored from 1 to 99, and each is equally important. One numerical score is assigned for Usual Behavior and one for Needs with its counterpart Stress. The scores are presented on three levels. The Usual Behavior and Needs scores can be thought of as working together like a pair of lenses through which we see ourselves and what we expect from others. Then the third level describes what our Stress might look like when our Needs aren’t met. In this way, the Components will help you visualize the conundrum that the flip side of defining your strengths is recognizing your weaknesses. Unlike the scores for the Interest areas, these rankings are not comparative with a general landscape but instead show the intensity of the personality aspect. They signify

| 1–10 | Extremely intense |

| 11–39 | Moderately intense |

| 40–60 | Identify with aspects of both high and low scores |

| 61–90 | Moderately intense |

| 91–99 | Extremely intense |

We looked briefly at the multidimensional aspect of Birkman rankings as they related to the Life Style Grid. Here we review the three Birkman points of view as they relate to the eleven Components.

Usual Behavior

Our Usual Behavior describes how we show up to the public and interact productively in the workplace and in our daily arena. In other words, those around us can observe this behavior. It is the socialized behavior that we have learned to use to get along with others and that serves us well. This is always seen as positive in nature, because our Usual Behavior, being malleable, is the easiest way for us to adapt and modify as we navigate our days.

Needs

Others do not easily see these critical Birkman differentiators. The motivating qualities that Birkman calls Needs are unique to the Birkman among assessments, and they matter enormously. These are how we recharge and maintain our emotional equilibrium so that we stay productive. This is the reason that we begin to show signs of distress when our Needs go unmet over a period of time. Many psychological tools place people in a category of their Usual Behavior, but stop short of capturing these vitally important Needs. If we are to succeed in self-managing and cultivate a greater degree of emotional intelligence, however, we must be able to accurately identify our Needs in relation to how we interact with other people.

“If you can make sure that those closest to you understand your three most important Needs, it can be life-changing,” consultant Steve Cornwell of Atlanta says. We then have to go a step further to understand the Needs of the people who matter in our world, whether they are colleague, boss, family member, or significant other. That process can be difficult. The fascinating thing about people is that in our natural diversity, we often end up having diametrically opposite Needs from those around us with whom we deal on a daily basis. Yet we have to find a way to come together and understand each other so that we can get things done and be happy in the process. Birkman can move you past the frustration to do just that.

Stress

This includes all of the counterproductive ways we act out when, over time, we don’t get our Needs met. As with our Usual Behavior, our Stress behaviors are easy to see. And it isn’t pretty. We don’t always like to admit to this kind of behavior, but those around you will help you to understand how you look to the outside world under Stress.

Stress can be subtle but destructive. When it erupts in the workplace, it can alienate colleagues, derail teams, disrupt projects, and even sabotage a career. One major goal of the Birkman is to help you do a better job of minimizing the time you spend in Stress. By becoming aware of what happens, you can avoid getting stuck in self-defeating Stress behaviors. When you learn to recognize the early warning signs, you can quickly move away from Stress and back to productiveness. The Birkman offers in simple language what your Stress behavior will look like. It will even be able to tell you specifically—through your Component results—how your Stress behavior will look to the person you’re dealing with who has a different perspective from you. This is where the Birkman comparative reports can be valuable to coworkers. “Use the Birkman Stress pages to self-coach,” adds Steve. “When you are stressed, use the report to find solutions to what’s bothering you.” Talking to a Birkman consultant first will help to clarify the complexity that the Birkman profile reveals. But after the initial coaching sessions, most clients find it easy to refer back to the Component section of their reports and the narrative that accompanies it for self-tuning and everyday maintenance.

KEEPING POSITIVE

You can’t change a leopard’s spots, but you can learn how to handle the leopard. People will benefit when they leverage their attributes and stay in their productive zone. It is best for the company, but more important is that it is best for you as an individual. When you understand why you are frustrated, upset, or burned out, you can manage those pain points better and get back to the positive, productive aspects of your strengths. In Birkman language, the goal is to teach you and others how to manage the disparity between your positive outward behavior and your core recharging needs.

When the Birkman is introduced to a group that interacts with each other in the workplace or in any other setting, a new dialogue can begin that is more nurturing for each individual’s needs.

An experienced consultant knows how to analyze the interplay of the thirty-three numbers that make up a complete Component report, and especially the significance of the Usual Behavior versus the Needs scores. The detail offered by the Birkman is remarkable, and the information is full of surprises, if only because most people don’t have such conversations with themselves, let alone with colleagues. It reveals truths and subtleties about workplace demands and performance that might never otherwise be articulated.

Is the best boss for you the one who is personable and asks you about your family and favorite films as they stop for an occasional chat? Or would you prefer a direct, no-nonsense boss who bullet-points instructions and e-mails you a clear plan of action? The type of boss you actually prefer might not be what you would typically view as the ideal boss. Alternatively, it might also not be the authority figure any particular boss wishes to be. The Birkman will point to what best suits you in the workplace, giving valuable information about productivity and how best to communicate between boss and direct report.

Every one of the myriad combinations of factors in your personality report is going to have its advantages and disadvantages. Seen as a whole, it will describe what you need for your own self-fulfillment, how you relate to colleagues and those closest to you, and how people in your environment see you. Showing people how their individual style affects others has opened a lot of eyes in workplaces worldwide, whether the employee is dealing with reports, customers, colleagues, or bosses. The assessment feedback offers a basis for a new kind of conversation.

THE BIRKMAN AT WORK: NEGOTIATIONS

The Birkman is often used to great advantage for every sort of negotiation, where a deep understanding of the motivations and mind-set of the people across the table can greatly aid talks. At the heart of the Birkman, after all, is learning to recognize differences and then create harmony where compromise seems most difficult.

Dana Scannell of Newport Beach, California, has used the Birkman with success since the late 1990s in his role as adviser to a large union doing business with a major U.S. airline. He facilitated the negotiation of a precedent-setting four-year contract between the carrier and the union, which represented several thousand employees. He was working for the union, and so had little information on the other side. But the union members had their Birkmans in hand and had become familiar with Birkman vocabulary; Dana helped them to use their own results to understand management’s thinking.

The mood in the small negotiating room at company headquarters had long turned grim over the two years that the talks dragged on, Dana recalls. There were some twenty participants, including four negotiators plus four attorneys on each side, crammed into the room, sitting around a table that formed an open square in the center of the room. Negotiations were formal, but jackets were shed at the door, so it was just shirts and ties for the mostly male group. The negotiators had grown cordial enough toward each other over the months, but the overall mood was contentious as management came under increasing pressure to stanch the damage done by the lack of a labor contract. Progress had proceeded at a snail’s pace, and there was little to show for the time invested. For months an outright logjam had formed over pay rates, protection from outsourcing, staffing levels, and overtime, among other big issues.

Dana, new to the job, had to do something to help jump-start the talks and lift the spirits of the union, which had taken a beating with its persistent demands for givebacks. For more than a month, he had near-daily meetings with the team, including some marathon sessions lasting late into the night. He would fly in to meet with the team on Monday; join the meeting with the other side Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday; and meet again with the union team on Friday. After each of the combined sessions, Dana and the union negotiators would huddle together to hash through what happened. That schedule went into overdrive the final three weeks of the negotiations when both sides met six days a week.

Then the strategy emerged. “We looked at each individual on the labor side and asked who they were most similar to on the management side,” Dana explains. “We could see who was bugging them—their opposites. So we said, ‘Let’s not provoke them but build a rapport.’” The old way, he says, might have been to start chatting about the person’s family: “Oh, you have three kids, so do I.” But the negotiators were beyond such clichés. “We went deeper to see what made them tick,” he recalls, in the manner of the Birkman strategy.

The union negotiating team would pick a strong Birkman element that seemed as if it could be related to one member of the other side, such as a high Numerical Interest, and play off it during talks with language such as, “I know we have to get to the bottom line here,” and, “This is where this would get us,” Dana recalls.

Another person was tagged as probably being a Blue with a Component score that suggested a strong Need to see the greater good of an action and a degree of individual freedom. “We’d start by saying, ‘I know you have to come up with numbers, but we have to do what’s right by the people and we have to make this look like it makes sense to the both of us. What does this feel like to you? Forget we’re on the opposite sides of the table. What would fit for you and be sellable for me?’”

Suddenly things started moving. Years of slogging gave way to lively debate and compromise. Within ten days, the group had an industry-leading contract hammered out that included record-setting concessions—all negotiated amid recession and painful economic realities for the company. The union had the contract that all similar unions wanted, getting more in terms of hourly rates, job protection, and retirement benefits than they had thought possible.

The CEO of the carrier walked into the room at the end and shook the negotiators’ hands and said, “We have a deal.” Dana had never before seen such a gesture in all his years of union work. What the CEO said next was even more of a surprise. He went up to Dana and said, “I know you’re on their side, but we need to talk.” He asked if the union would lend out Dana for a limited project to improve customer service. All sides agreed. The chief executive officer had figured out what had been going on, Dana says, and he was impressed by the results.