CHAPTER TEN

UNDERSTANDING PEOPLE IN PUBLIC ORGANIZATIONS

Values, Incentives, and Work-Related Attitudes

The internal and external impetuses that arouse and direct effort—the needs, motives, and values that push us and the incentives, goals, and objectives that pull us—obviously play major roles in motivation. Every theory of work motivation discussed in Chapter Nine includes such factors in some way. Classic debates have raged, however, over what to call them; what the most important needs, values, goals, and incentives are; and what roles they play. These debates raise serious challenges for both managers and researchers. This chapter discusses these topics, and also describes important work-related attitudes, such as job satisfaction, that OB researchers have developed. These work attitudes provide valuable insights that help us to analyze and understand the experiences that people have in their work. All these topics are related to work motivation, but differ from it in important ways. They are covered here separately not only because they are distinct from motivation and motivation theory, but also because discussing all these topics together would make for a very long chapter!

For a long time, the concepts of values, motives, and incentives have been prominent in the theory and practice of management, including public management. If anything, they have become even more prominent in recent years. Studies of leadership, change, and organizational culture—topics covered in later chapters—have increasingly emphasized the importance of shared values in organizations. Writers and consultants exhort leaders to learn to understand the values of the members of their work groups and organizations, and the incentives that will motivate them. DiIulio (1994) showed how particularly important this can be in public organizations by describing how members of the Bureau of Prisons display a strong incentive to serve the organization’s values and mission, in part because some of the bureau’s long-term leaders have effectively promoted those values. Goodsell (2010) describes the motivating effects of the missions of government organizations that appeal to the values and motives of the members of those organizations.

As described in Chapter Nine, people in all types of organizations, including government organizations at all levels of government and in many different nations, have responded to surveys that ask about their work attitudes and the value they place on various rewards or incentives. In 2005, a consortium of researchers administered the International Social Survey Program in many nations in Asia, Europe, and North America. The survey asked numerous questions about the respondents’ lives, including about their work. These included questions about how important to them were each of a list of work rewards, and about the rewards that attracted them to their jobs. Two of the questions asked whether the respondent regarded his or her work as providing the ability to help others, and whether it was useful to society. Additional questions asked the respondent to rate the importance she or he attached to having a job that helps others and that is useful to society. On such questions, respondents in twenty-nine out of thirty nations were higher in agreement, to a statistically significant degree, than respondents who worked in the private sector. The public sector respondents also rated work that is useful to society and helpful to others as more important to them, as compared to the private sector respondents. Very consistently across the nations, people who worked for government were more likely to say that they consider it important to have work that helps others and benefits society and that they felt that their work does benefit society and help others (Stritch, Bullock, and Rainey, 2013).

Exactly what these responses mean, and how important they are as influences on the respondents’ work behaviors, is not entirely clear. Yet remember the “generic” view of organizations that Chapters One and Two discussed, that assumes or contends that there are no important differences between public and private organizations? If that is so, how do we get such internationally consistent responses from people that appear to contradict that generic perspective in important ways? More generally, the example of this survey illustrates the challenges practicing managers and researchers face in analyzing and understanding the needs, values, and motives of people in organizations.

How can managers and scholars understand values, motives, incentives, and related concepts? This chapter approaches the problem by reviewing many of the efforts to specify and define important needs, values, motives, and incentives. This review provides a complex array of approaches to the problem, but it also gives a lot of examples and suggestions from which managers can draw.

Motivation theorists use the terms we have been using—such as need, value, motive, incentive, objective, and goal—in overlapping ways. We can, however, suggest definitions for them.

- A need is a resource or condition required for the well-being of an individual.

- A motive is a force acting within an individual that causes him or her to seek to obtain or avoid some external object or condition.

- An incentive is an external object or condition that evokes behaviors aimed at attaining or avoiding it.

- A goal is a future state that one strives to achieve, and an objective is a more specific, short-term goal, a step toward a more general, long-term goal.

- Rokeach (1973), an authority on human values, offered an often-quoted definition of a value as “an enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state of existence” (p. 5).

Many people would disagree with these definitions and switch some of them around. The challenge for public managers, however, is to develop a sense of the range of needs, values, motives, incentives, and goals that influence employees. The research on motivation tells us to expect no simple list, because these factors always occur in complex sets and interrelationships. The next section provides a description of some of the most prominent conceptions of these topics.

Attempts to Specify Needs, Values, and Incentives

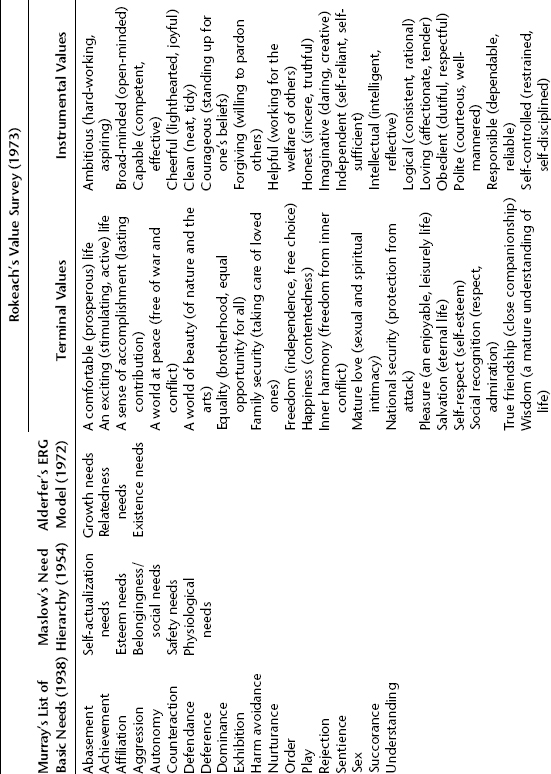

Tables 10.1 and 10.2 present some of the prominent lists and typologies of needs, motives, values, and incentives. These lists illustrate the diversity among theorists and provide some of the most useful enumerations of these topics ever developed. Murray’s typology of human needs (1938), for example, provided one of the more elaborate inventories of needs ever attempted, but even so, it failed to exhaust all possible ways of expressing human needs and motives. Maslow’s needs hierarchy (1954), described in Chapters Two and Nine, proposed five categories of needs, arranged in a “hierarchy of prepotency” from the most basic physiological needs through safety needs, social needs, and self-esteem needs, and up to the highest level, the self-actualization needs.

TABLE 10.1. THE COMPLEXITY OF HUMAN NEEDS AND VALUES

TABLE 10.2. TYPES OF INCENTIVES

| Incentive Type | Definitions and Examples |

| Barnard (1938) | |

| Specific Incentives | Incentives “Specifically Offered to an Individual” |

|

Material inducements |

Money, things, physical conditions |

|

Personal, nonmaterialistic inducements |

Distinction, prestige, personal power, dominating position |

|

Desirable physical conditions of work |

|

|

Ideal benefactions |

“Satisfaction of ideals about nonmaterial, future or altruistic relations” (pride of workmanship, sense of adequacy, altruistic service for family or others, loyalty to organization, esthetic and religious feeling, satisfaction of hate and revenge) |

| General Incentives | Incentives That “Cannot Be Specifically Offered to an Individual” |

|

Associational attractiveness |

Social compatibility, freedom from hostility due to racial or religious differences |

|

Customary working conditions |

Conformity to habitual practices, avoidance of strange methods and conditions |

|

Opportunity for feeling of enlarged participation in course of events |

Association with large, useful, effective organization |

|

Condition of communion |

Personal comfort in social relations |

| Simon (1948) | |

| Incentives for employee participation | Salary or wage, status and prestige, relations with working group, promotion opportunities |

| Incentives for elites or controlling groups | Prestige and power |

| Clark and Wilson (1961) and Wilson (1973) | |

| Material Incentives | Tangible rewards that can be easily priced (wages and salaries, fringe benefits, tax reductions, changes in tariff levels, improvement in property values, discounts, services, gifts) |

| Solidary Incentives | Intangible incentives without monetary value and not easily translated into one, deriving primarily from the act of associating |

|

Specific solidary incentives |

Incentives that can be given to or withheld from a specific individual (offices, honors, deference) |

|

Collective solidary incentives |

Rewards created by act of associating and enjoyed by all members if enjoyed at all (fun, conviviality, sense of membership or exclusive-collective status or esteem) |

| Purposive incentives | Intangible rewards that derive from satisfaction of contributing to worthwhile cause (enactment of a law, elimination of government corruption) |

| Downs (1967) | |

| General “motives or goals” of officials | Power (within or outside bureau), money income, prestige, convenience, security, personal loyalty to work group or organization, desire to serve public interest, commitment to a specific program of action |

| Niskanen (1971) | |

| Variables that may enter the bureaucrat’s utility function | Salary, perquisites of the office, public reputation, power, patronage, output of the bureau, ease of making changes, ease of managing the bureau, increased budget |

| Lawler (1971) | |

| Extrinsic rewards | Rewards extrinsic to the individual, part of the job situation, given by others |

| Intrinsic rewards | Rewards intrinsic to the individual and stemming directly from job performance itself, which satisfy higher-order needs such as self-esteem and self-actualization (feelings of accomplishment and of using and developing one’s skills and abilities) |

| Herzberg, Mausner, Peterson, and Capwell (1957) | |

| Job “factors” or aspects, rated in importance by large sample of employees | In order of average rated importance: security, interest, opportunity for advancement, company and management, intrinsic aspects of job, wages, supervision, social aspects, working conditions, communication, hours, ease, benefits |

| Locke (1969) | |

| External incentive | An event or object external to the individual which can incite action (money, knowledge of score, time limits, participation, competition, praise and reproof, verbal reinforcement, instructions) |

Researchers trying to determine whether individuals rank their needs as the theory predicts have found that Maslow’s five-level hierarchy does not hold. Instead, the evidence points to a two-step hierarchy: lower-level employees show more concern with material and security rewards, while higher-level employees place more emphasis on achievement and challenge (Pinder, 2008). Analyzing the results of a large survey of federal employees, Crewson (1995b) found this kind of difference between the employees at lower General Schedule (GS) salary levels (GS 1–8) and the highest GS levels (GS 16 and above). He found that respondents at the lower salary levels rated job security and pay as the most important job factors, while executive-level employees gave the highest rating to the importance of public service and to having an impact on public affairs. The executive-level employees also gave their lowest ratings to job security and pay. This suggests that the self-actualization motives among public sector executives focus on public service, a point to which we will return later.

Alderfer’s typology of existence, relatedness, and growth needs (1972) provided still another example of an effort to specify basic human needs. On the basis of empirical research, Alderfer reduced Maslow’s categories to this more parsimonious set.

As Crewson’s analysis shows, this distinction between higher- and lower-order motives holds in public organizations. Other surveys have also shown that lower-level public employees attach more importance to job security and benefits than public managers and executives, who say they consider these factors less important than accomplishment and challenging work. Managers coming into government often say they are attracted by the opportunity to provide a public service and to influence significant events. At the same time, as discussed shortly, prominent motivation theorists argue that employees at all levels can be motivated by higher-order motives and should be treated accordingly.

Human values are also basic components of motivation. Rokeach (1973) developed two corresponding lists of values—instrumental values and terminal values (see Table 10.1)—and designed questionnaires to assess people’s commitment to them. Sikula (1973a, 1973b) compared government and business executives using the Rokeach instrument, compiling responses from managers in twelve occupational groups. Six of the groups consisted of managers from industry, education, and government, including fifty-four executives in the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW, now the Department of Health and Human Services). The other six groups consisted of people in nonmanagerial roles. The value profile of the HEW executives was generally similar to that of the other managerial groups, whose members all placed a higher priority on values related to competence (being wise, logical, and intellectual) and initiative (imagination, courage, sense of accomplishment) than the members of the other groups. Among the six managerial groups, the HEW executives placed the highest priority on being responsible, honest, helpful, and capable. They also gave higher ratings than any other group to the terminal values of equality, mature love, and self-respect, and they were lower than the other groups on the terminal values of happiness, pleasure, and a comfortable life. Sikula’s limited sample leaves questions about whether the findings apply to all public managers. Yet the emphasis on service (helpfulness) and integrity and the de-emphasis on comfort and pleasure conform with other findings about public managers described later in this chapter and in the next one.

Researchers continue to use the Rokeach concepts and methods to study values among people in government and the nonprofit sector. Simon and Wang (2002), for example, used this approach to assess value changes over time in Americorps volunteers. Among other changes, they found increases in the ratings of freedom and equality among the volunteers after their service, compared with their expressed values prior to their service.

Incentives in Organizations

Other researchers have analyzed incentives in organizations as a fundamental aspect of organized human activity. As described in Chapter Two, some very prominent theories about organizations have depicted them as “economies of incentives.” Organizational leaders must constantly maintain a flow of resources into their organization to cover the incentives that must be paid out to induce people to contribute to the organization (Barnard, 1938; March and Simon, 1958; Simon, 1948). In analyzing these processes, these theorists developed the typologies of incentives outlined in Table 10.2, which provides about as thorough an inventory as anyone has produced (although Barnard used some very awkward terms). The typologies reflect the development across the twentieth century of an increasing emphasis in management theory on incentives besides material ones, such as personal growth and interest and pride in one’s work and one’s organization. Barnard, March, and Simon implied that all executives, in both public and private organizations, face these challenges of attaining resources and providing incentives.

Clark and Wilson (1961) and Wilson (1973) followed this lead in developing a typology of organizations based on the primary incentive offered to participants—material, solidary (defined as “involving community responsibilities or interests”), or purposive (see Table 10.2). Differences in primary incentives force differences in leadership behaviors and organizational processes. Leaders in solidary organizations, such as voluntary service associations, face more pressure than leaders in other organizations to develop worthy service projects to induce volunteers to participate. Leaders in purposive organizations, such as reform and social protest organizations, must show accomplishments in relation to the organization’s goals, such as passage of reform legislation.

Subsequent research on this typology of primary organizational incentives has concentrated on why people join political parties and groups; it has not specifically addressed public agencies. The concept of purposive incentives has great relevance for government, however. For many public managers, a sense of valuable social purpose can serve as a source of motivation. In addition to the Crewson (1995b, 1997), DiIulio (1994), and Goodsell (2010) examples described earlier, large surveys of federal employees have found that high percentages of them agree that the opportunity to have an impact on public affairs provides a good reason to join and stay in government service, especially at higher managerial and professional levels, and especially in certain agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency.

Extrinsic and Intrinsic Incentives.

The distinction between extrinsic and intrinsic incentives described in Table 10.2 figures importantly in research and practice related to motivation in organizations. Since the days of Frederick Taylor’s pay-them-by-the-shovelful approach to rewarding workers (see Chapter Two), management experts have increasingly emphasized the importance of intrinsic incentives in work.

The “Most Important” Incentives.

The variety of incentives presented in Table 10.2 shows why we can expect no conclusive rank-ordered list of the most important needs, values, and incentives of organizational members. There are too many ways of expressing these incentives, and employees’ preferences vary according to many factors, such as age, occupation, and organizational level. Herzberg, Mausner, Peterson, and Capwell (1957) compiled the importance ratings shown in Table 10.2 from sixteen studies covering eleven thousand employees. Other studies have come to different conclusions, however. Lawler (1971), for example, disagreed with the Herzberg ratings, indicating that a wider review of research suggested that people rate pay much higher (averaging about third in importance in most studies). He argued that management scholars have often underestimated the importance of pay because they object to managerial approaches that rely excessively on pay as a motivator. He pointed out that pay often serves as a proxy for other incentives, because it can indicate achievement, recognition by one’s organization, and other valued outcomes. Pay can serve as an effective motivating incentive in organizations, if pay systems are designed strategically (Lawler, 1990).

Anyone interested in public management and public organizations should be aware of theories and research results about the importance of certain motives and incentives in public organizations. Downs (1967) and Niskanen (1971), two economists who developed theories about public bureaucracies, proposed the inventories of public managers’ motives listed in Table 10.2. They made the point that for public managers, political power, serving the public interest, and serving a particular government bureau or program become important potential motives.

Downs developed a typology of public administrators on the basis of such motives. Some administrators, he argued, pursue their own self-interest. Some of these people are climbers, who seek to rise to higher, more influential positions. Conservers seek to defend their current positions and resources. Other administrative officials have mixed motives, combining concern with their own self-interest with concerns for larger values, such as public policies and the public interest. They fall into three groups of managers who pursue increasingly broad conceptions of the public interest. Zealots seek to advance a specific policy or program. Advocates promote and defend an agency or a more comprehensive policy domain. Statesmen pursue a more general public interest. As public agencies grow larger and older, they fill up with conservers and become rigid (because the climbers and zealots leave for other opportunities or turn into conservers). Among the mixed-motive officials, few can maintain the role of statesmen, and most become advocates. In the absence of economic markets for outputs, the administrators must obtain resources through budget allocation, and they have to develop constituencies and political supports for their agency. This pushes them toward the advocate role and discourages statesmanship.

For years, Downs’s book (1967) was a widely cited work on government bureaucracy, but researchers have seldom tested his theory in empirical studies. Its accuracy remains uncertain, then, but it does make the important point that public managers’ commitments to their agencies, programs, and the public interest become important motives for them. They also face difficult decisions about the relative importance of these motives and the relationships among them.

Niskanen (1971) also was interested in how bureaucrats “maximize utility,” as economists put it. He theorized that, in the absence of economic markets, bureaucrats pursuing any of the incentives listed in Table 10.2 do so by trying to obtain larger budgets. Even those motivated primarily by public service and altruism have the incentive to ask for more staff and resources and hence larger budgets. Government bureaucracies therefore tend to grow inefficiently. Public managers clearly do defend their budgets and usually try to increase them. Yet many exceptions occur, such as when agency budgets increase because of legislative adjustments to formulas and entitlements that agency administrators have not requested. Some agencies also initiate their own cuts in funding or personnel or accept such reductions fairly readily (Golden, 2000; Rubin, 1985). In the 1980s, the Social Security Administration launched a project to reduce its workforce by seventeen thousand, about 21 percent of its staff (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1986). As part of the National Performance Review, the major federal government reform initiative during the Clinton administration, federal agencies eliminated over 324,000 jobs in the federal civilian workforce (Thompson, 2000). For reasons such as this, Niskanen’s more recent work focused on discretionary budgets—those parts of the organizational budget over which administrators have some discretion (see Blais and Dion, 1991). An increasing body of research finds mixed support for many of Niskanen’s basic assumptions about the motives and capacities of bureaucrats to engage in budget maximizing (Bendor and Moe, 1985; Blais and Dion, 1991; Dolan, 2002).

Both of these theories reflect some theorists’ tendency to argue that public bureaucracies incline toward dysfunction because of the absence of economic markets for their outputs (see, for example, Barton, 1980; Tullock, 1965). The theories may accurately depict problems to which public organizations are prone. Later chapters discuss the ongoing controversy over the performance of public organizations and point out that in fact they often perform very well.

Attitudes Toward Money, Security and Benefits, and Challenging Work.

Government does not offer the large financial gains that some people make in business, although civil service systems have traditionally offered job security and well-developed benefits programs. One might expect these differences to be reflected in public employees’ attitudes about such incentives. We have increasing evidence that they do. Numerous surveys have found that government employees place less value than employees in business on money as an ultimate goal in work and in life (Houston, 2000; Jurkiewicz, Massey, and Brown, 1998; Karl and Sutton, 1998; Khojasteh, 1993; Kilpatrick, Cummings, and Jennings, 1964; Lawler, 1971; Porter and Lawler, 1968; Rainey, 1983; Rawls, Ullrich, and Nelson, 1975; Siegel, 1983; Wittmer, 1991). Some studies have found no difference between public and private employees in the value they attach to pay (Gabris and Simo, 1995). Such variations in research results probably reflect the way such attitudes vary by time period, organizational level, geographical area, occupation, and type of organization. Gabris and Simo used a sample containing only two public and two private organizations, so the sample may not be representative of the two sectors. Yet this possibility reminds us that we have to be careful, in designing research and drawing general conclusions, to take into account such factors as the organizational and professional levels of the individuals.

Organizational level figures importantly in comparisons of attitudes about pay because, obviously, at top executive levels and in certain advanced professions, public sector salaries are usually well below those in the private sector. Below the highest organizational levels, however, pay levels are often fairly comparable in the public and private sectors (Donahue, 2008). Studies have sometimes found that federal white-collar salaries were lower than private sector salaries for similar jobs, by about 22 percent according to one study (U.S. General Accounting Office, 1990).

For such reasons, analyzing the comparability of pay between the two sectors can be complicated. Public employee unions often emphasize studies showing lower levels of pay in the public sector, but economists and other analysts often respond by pointing out that even when such differences exist, superior benefits in the public sector, such as greater job security and security of health and retirement benefits, eliminate the difference in total compensation. Differences between the two sectors tend to be concentrated at certain levels and in certain occupations and professions, and when all forms of compensation are taken into account, public sector compensation levels often appear comparable or superior to those in the private sector at lower organizational levels (Donahue, 2002). Gold and Ritchie (1993), for example, pointed out that average salaries for state and local government employees tend to be higher than average salaries for private sector employees in the same state. Yet public sector workers with higher skill levels and those at higher levels make less than comparable private sector employees. These differences are due to a different skill mix in the two sectors. The private sector has a higher proportion of blue-collar workers, and the public sector has a higher proportion of technical and professional workers, who tend to get higher pay than blue-collar workers. So the higher average in the public sector is apparently due to the employment of a larger proportion of higher-paid technical and professional employees, although these same employees may make less than comparable employees in the private sector (Gold and Ritchie, 1993).

Langbein and Lewis (1998) analyzed results of a survey of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and compared the engineers in the public sector and in defense contractor firms to those in the nondefense-related private firms. They found evidence that the engineers in the public and defense contractor organizations had lower levels of productivity than the engineers in the nondefense-related firms, but the public and defense contractor engineers were significantly underpaid compared with the private sector engineers, even after controlling for productivity.

As this suggests, at the highest executive levels and for professions such as law, engineering, and medicine, the private sector offers vastly higher financial rewards, and the differences in these areas have been increasing (Donahue, 2008). Studies of high-level officials who entered public service have found that most of them took salary cuts to do so. Compensation did not influence their decision, however; challenge and the desire to perform public service were the main attractions (Crewson, 1995b; Hartman and Weber, 1980). In sum, many people who choose to work for government do not emphasize making a lot of money as a goal in life, even though at lower organizational levels many public employees do not work at markedly lower pay than people in similar private sector jobs. Because top executives and professionals in government work for much lower salaries than their private sector counterparts, they must be motivated by goals other than high earnings.

Nevertheless, pay issues can still have a very strong influence on the motivation of public sector employees. As pointed out earlier, pay can have a symbolic meaning, as a recognition of an employee’s skill and performance (Lawler, 1990). Studies with limited samples have also found that some public managers attach higher importance to increases in their pay than do private sector managers. Apparently these midlevel public managers felt that they had little impact on their organizations and turned to pay rather than responsibility as a motive (Schuster, 1974).

Research also indicates that security and benefits serve as important incentives for many who join and stay with government, although the research results on this point are mixed. Decades ago, a major survey by Kilpatrick, Cummings, and Jennings (1964) found that vast majorities of all categories of public employees, including federal employees, cited job and benefit security (retirement, other protective benefits) as their motives for becoming a civil servant. Sixty-two percent of their sample of federal executives (GS 12 and above) held this view. A survey of about seventeen thousand federal employees by the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (1987) found that 81 percent considered annual leave and sick leave benefits as reasons to stay in government, and 70 percent saw job security as a good reason to stay. Houston (2000) and Jurkiewicz, Massey, and Brown (1998) also reported surveys in which public employees placed higher value on job security or on security and stability in general than did private sector respondents to the surveys.

As described earlier, however, a version of the Maslow needs hierarchy tends to apply. Compared to employees at lower salary levels, smaller percentages of the public sector executives, managers, and professionalized employees (such as scientists and engineers) responding to surveys attached a high level of importance to benefits and job security (Crewson, 1995b), and at least one study found that they placed lower value on job security than private sector respondents did (Crewson, 1997). It appears reasonable to conclude that job security and other forms of security such as stable health and retirement benefits have served as significant incentives and attractive work factors for many public sector employees, although employees at higher salary, managerial, and professional levels tended to attach less value to them in their responses to surveys.

As compared with employees at lower salary levels, managers and executives generally attach more value to intrinsic incentives, in that they report more attraction to opportunities for challenge and significant work. Some evidence indicates that public sector employees—especially managers, executives, and those at professional levels—give higher ratings of the importance of intrinsic incentives than do their private sector counterparts (Hartman and Weber, 1980). The large Federal Employee Attitude Surveys of the late 1970s and early 1980s asked newly hired employees to rate the importance of various factors in their decision to work for the federal government. Virtually all of the executive-level employees (97 percent of GS 16 and above) rated challenging work as the most important factor. Employees at lower GS levels rated job security and fringe benefits more highly than did the executives, but about 60 percent of them also rated challenging work as the most important factor. Rawls, Ullrich, and Nelson (1975) found that students headed for the nonprofit sector—mainly government—showed higher “dominance,” “flexibility,” and “capacity for status” ratings in psychological tests and a lower valuation of economic wealth than did students headed for the for-profit sector. The nonprofit-oriented students also played more active roles in their schools. Guyot (1960) found that a sample of federal middle managers scored higher than their business counterparts on a need-for-achievement scale and about the same on a measure of their need for power. We have some evidence, then, that government managers express as much concern with achievement and challenge as private managers do—or express even more concern.

Khojasteh (1993) found that intrinsic rewards such as recognition had higher motivating potential for a sample of public managers than for a sample of private managers. Crewson (1997) analyzed two large surveys that indicated that public sector employees placed more importance than private employees on intrinsic incentives such as helping others, being useful to society, and achieving accomplishments in work. Gabris and Simo (1995) found no differences between public and private employees on perceived importance of a number of extrinsic and intrinsic motivators, but they did find that the public sector employees placed more importance on service to the community. Karl and Sutton (1998) reported survey results showing that workers in both the public and the private sectors appear to be placing more importance on job security than in the past, but public sector workers report that they value interesting work more than private sector workers do, whereas the private sector workers place more importance than public sector respondents do on good wages. Jurkiewicz, Massey, and Brown (1998) reported that public sector employees gave higher ratings than private employees to having the chance to learn new things and the chance to use their special abilities. Comparing a large sample of federal executives to a large sample of business executives, Posner and Schmidt (1996) found that the federal executives placed greater importance on such organizational goals as quality, effectiveness, public service, and value to the community. The business executives, however, attached more importance to morale, productivity, stability, efficiency, and growth than did the federal executives.

These studies suggest that challenging, significant work and the opportunity to provide a public service are often the main attractions for public managers. Perceptions of public service vary over time, however, with changes in the political climate, the economy, and generational differences. Surveys of career preferences among top students at leading universities have found that these students place a high priority on challenging work and personal growth. They see government positions as less likely than positions in private industry, however, to provide challenging work and personal growth (Partnership for Public Service, 2002; Sanders, 1989). They see government employment as providing superior opportunities for service to society, but they rated that opportunity as intermediate in importance.

On the other hand, researchers have found that younger workers in the public sector are expressing higher levels of general job satisfaction than younger workers in the private sector (Steel and Warner, 1990) and that employees entering the public sector show higher levels on certain measures of skill and quality than do those entering the private sector (Crewson, 1995a). These findings appear to apply to all of the broad populations of workers in the public and private sectors. They may indicate that, overall, government does provide working conditions that are generally superior to those in the private sector, because private employers can more readily fire, lay off, and otherwise impose difficulties on workers. The differences may not hold, however, for highly talented young people considering the public service as a career. Yet if the public sector can indeed attract high-quality employees, the challenge of providing them with challenging work becomes all the more important.

The Motive for Public Service: In Search of the Service Ethic

The need to provide challenging work in the public service and the motives for pursuing such work brings us to the motive that should make people want to work for government—the service ethic, the desire to serve the public. Remember the international survey, described earlier, that found that in dozens of nations, government employees give higher importance ratings than private sector employees to work that benefits society and that helps others? In the past two decades, scholars have begun to refer to this topic as public service motivation (PSM).

In a sense, the topic is many centuries old, and evidence of a motive for public service has been appearing for years. Public executives and managers tend to express motivation to serve the public, as shown by Sikula’s survey (1973a), described earlier. Similarly, Kilpatrick, Cummings, and Jennings (1964) found that when they asked federal executives, scientists, and engineers to identify their main sources of occupational satisfaction, the respondents gave higher ratings than their counterparts in business to the importance of doing work that is worthwhile to society, and to helping others. Surveys of federal employees have found that high percentages of managers and executives entering the federal government rated public service and having an impact on public affairs as the most important reasons for entering federal service, with very low percentages of these groups rating salary and job security as important attractions (Crewson, 1995b). Findings such as these suggest the common characteristics of persons motivated by public service: they place a high value on work that helps others and benefits society, involves self-sacrifice, and provides a sense of responsibility and integrity. Public managers often mention such motives (Crewson, 1997; Hartman and Weber, 1980; Houston, 2000; Kelman, 1989; Lasko, 1980; Sandeep, 1989; Wittmer, 1991).

As indicated in Tables 10.1 and 10.2, many analyses of values, motives, and incentives in organizational research and the social sciences do not focus directly on PSM. Many pay no attention to such motives. This suggests the need for a distinct concept of PSM. While it is by no means restricted to government employees, PSM should play a major part in the development of theories of public management and behavior in public organizations. But the surveys and findings mentioned earlier use general questions about benefiting society and helping others. This leaves questions about what we mean by PSM. Can we define such a pattern of motivation clearly? Can we measure and assess how much of it a person has? These questions have both intellectual and practical importance. Earlier chapters and sections have cited examples of how such motives can stimulate and energize people in their work. Such a pattern of motivation can serve as a source of incentives alternative to pay and other rewards that are often constrained in government.

For these reasons, researchers began to pursue the meaning and measurement of PSM. Perry and Wise (1990) suggested that public service motives can fall into three categories: instrumental motives, including participation in policy formulation, commitment to a public program because of personal identification, and advocacy for a special or private interest; norm-based motives, including desire to serve the public interest, loyalty to duty and to government, and devotion to social equity; and affective motives, including commitment to a program based on convictions about its social importance and the “patriotism of benevolence.” They drew the term patriotism of benevolence from Frederickson and Hart (1985), who defined it as an affection for all the people in the nation and a devotion to defending the basic rights granted by enabling documents such as the Constitution.

Drawing on these ideas, Perry (1996) provided evidence of the dimensions of a general public service motive and ways of assessing it. He analyzed survey responses from about four hundred people, including managers and employees in various government and business organizations, and graduate and undergraduate students. He analyzed the responses to the survey questions in Table 10.3 to see if the respondents answered them in ways that supported the conclusion that their public service motives fall into these dimensions. Perry’s dimensions and questions present a conception of public service motivation that challenges researchers, practicing managers, and professionals to consider whether this is a conclusive answer to the question of what we mean by PSM and how we measure it. We will return later to the point that responding to this challenge has become a very international process, drawing in researchers from many different nations.

TABLE 10.3. PERRY’S DIMENSIONS AND QUESTIONNAIRE MEASURES OF PUBLIC SERVICE MOTIVATION

Source: Perry, 1996.

| Dimension | Examples of Questionnaire Items |

| Attraction to public affairs | The give and take of public policymaking doesn’t appeal to me. (Reversed)a |

| I don’t care much for politicians. (Reversed) | |

| Commitment to the public interest | I unselfishly contribute to my community. |

| Meaningful public service is very important to me. | |

| I consider public service a civic duty. | |

| Compassion | I am rarely moved by the plight of the underprivileged. (Reversed) |

| Most social programs are too vital to do without. | |

| It is difficult for me to contain my feelings when I see people in distress. | |

| To me, patriotism includes seeing to the welfare of others. | |

| Self-sacrifice | I believe in putting duty before self. |

| Much of what I do is for a cause bigger than myself. | |

| I feel people should give back to society more than they get from it. | |

| I am prepared to make enormous sacrifices for the good of society. |

a“Reversed” indicates items that express the opposite of the concept being measured, as a way of varying the pattern of questions and answers. The respondent should disagree with such statements if they are good measures of the concept. For example, a person high on the compassion dimension should disagree with the statement, “I am rarely moved by the plight of the underprivileged.”

In addition to developing definitions and measures, researchers have found evidence linking PSM to other important factors in public organizations. Brewer and Selden (1998) analyzed the results of a large survey of federal employees about whistle-blowing (exposing wrongdoing). They found more public-service-related motives among employees who engaged in whistle-blowing than among those who did not. Naff and Crum (1999) found that the respondents to another large survey expressed higher levels of PSM, expressed higher job satisfaction, and had higher performance ratings from their supervisors, and otherwise expressed more positive attitudes toward their work. Alonso and Lewis (2001), analyzing the results of two surveys of very large samples of federal employees, also found that one of the surveys indicated that employees with higher levels of PSM received higher performance ratings from their supervisors. Complicating matters, however, the other survey showed a negative relationship between the supervisor’s performance ratings and the respondent’s expression of PSM.

Much of the research has used questionnaire surveys of government employees and social service volunteers, such as Perry’s PSM questionnaire or similar questions. Researchers have assessed the Perry questionnaires’ reliability and conceptual structure, and have developed shorter or alternative versions of the Perry instrument (for example, Coursey and Pandey, 2007; Vandenabeele, 2008). Recent research has identified antecedents and influences that relate positively to PSM, including a strong religious orientation, a family background that encourages altruistic service to others, gender, organizational factors such as positive leadership, low levels of red tape, and other sociodemographic and organizational factors (DeHart-Davis, Marlowe, and Pandey, 2006; Pandey and Stazyk, 2008; Park and Rainey, 2008). Wright (2007), for example, finds that when government employees express higher levels of “mission valence,” they report higher levels of PSM; that is, when they consider their organization’s goals important and when their job goals are specific and difficult, they report higher service motivation. Studies in PSM also show positive relations to important work and organizational attitudes, such as organizational commitment, work satisfaction, self-reported performance, intent to turn over (that is, to leave the organization), interpersonal citizenship behavior (helpful and supportive behaviors toward other employees), perceptions of leadership and organizational mission, and charitable activities (Bright, 2007, 2011; Frank and Lewis, 2004; Houston, 2006; Leisink and Steijin, 2009; Pandy and Stazyk, 2008; Pandey, Wright, and Moynihan, 2008; Park and Rainey, 2008; Vandenabeele, 2007, 2009; Wright, Moynihan, and Pandey, 2012). Adding a distinctive contribution to this stream of research and theory, Francois (2000) proposed a formal model that postulates that public sector organizational activities can operate as efficiently and effectively as private business organizations, when PSM acts as a basic incentive.

Perry’s index of PSM implies that it is a general motive on which people are higher or lower. What if people vary in the way they perceive and approach public service? Brewer, Selden, and Facer (2000) analyzed the responses concerning PSM from about seventy government employees and public administration students and concluded that the respondents fell into four categories of conceptions of public service: samaritans express a strong motivation to help other people, communitarians are motivated to perform civic duties, patriots work for causes related to the public good, and humanitarians express a strong motivation to pursue social justice. This differentiation of conceptions of PSM makes the important point that PSM is likely to vary among individuals and organizations.

Researchers have also found evidence that the beneficial effects of high levels of PSM depend on the fit between the person and the job and work environment. The environment and job need to have characteristics that fit the person’s needs and skills (Stijn, 2008; Vigoda and Cohen, 2003). Persons with high levels of PSM tend to attain jobs in the public sector, but those jobs must provide conditions that will fulfill public service motives.

Grant (2008) reports a particularly interesting experimental analysis of undergraduate students who were employed as telephone fundraisers for their university. One randomly assigned group received communication from the recipient of a fellowship based on the funds raised. The recipient told the fundraisers that their work had made a beneficial difference in her life. Another group of fundraising students served as a control group and received no communication from a fellowship recipient. The group that heard from the fellowship recipient afterward attained a significantly higher number of donation pledges and a higher total amount of money donated than was attained by the control group during the same period. The results indicate the performance-enhancing potential of showing people with prosocial motives the beneficial impact of their work. Bellé (2013) also reports experimental evidence showing that Italian nurses involved in a humanitarian project showed higher levels of performance when they had contact with the beneficiaries of their efforts and when they engaged in “self-persuasion” activities in which they reflected on the importance of their work.

An interesting issue in the analysis of PSM concerns the “motivation crowding” hypothesis; this proposes that pay can diminish intrinsic motives, such as PSM, under certain conditions. Ryan and Deci (2000a, 2000b) analyze the conditions under which extrinsic rewards such as money can diminish intrinsic motives such as enjoyment of the work itself. This crowding out of intrinsic motivation depends on the level of a person’s perceived self-determination. Intrinsic motivation depends on self-determination. If a person feels under the control of another person, intrinsic motivation diminishes. Frey and Reto (2001) suggest that a person’s PSM can go down when pay or salary is administered to the person in a way that reduces self-determination. Andersen and Pallesen (2008) provide an analysis of this hypothesis in a study of 149 Danish research institutions implementing new financial incentives for research productivity. Researchers received pay supplements for academic publication. Andersen and Pallesen report that the more the researchers perceived the incentives as supportive, as opposed to reducing self-determination, the more the incentives encouraged researchers to publish.

One important aspect of recent research on PSM is the international attention to the concept. Recent studies, cited in earlier paragraphs, report empirical analysis on data from Australia, Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United States. These studies indicate that measures of PSM generally show relations to other important variables in different nations, and thus indicate an international application and significance of PSM. Vandenabeele and Van de Walle (2008) employ an international social science survey to test whether there are differences in manifestations of public service motivation across nations and regions. They find that public service motivation has a universal character, but only to a certain extent. Patterns of public service motivation are different for various regions across the world. For example, because the Perry scale was developed for use with American respondents, Vandenabeele (2008) conducted a survey of Flemish civil servants with a scale developed with an orientation toward European society. He found that despite differences in questions and terms, the new scale confirms the dimensional structure of the Perry scale, except that the Flemish results include an additional dimension of “democratic governance.” These studies vary in the way that they conceive and measure PSM, and this accounts for some of the variations in their findings and directions.

Seeking to address this variation in a project that epitomizes the international character of this research, Kim, Vandenabeele, Wright, Anderson, and eleven other authors (2012) developed a questionnaire about PSM that they used to survey local government employees in twelve nations. They sought to develop an index of PSM that would be applicable in different nations. They developed questions that asked about dimensions similar to those of the Perry questionnaire, but modified; the dimensions included attraction to public service, compassion, self-sacrifice, and commitment to public values. The results indicated that the questions did not provide a common measure of PSM that applied in the same way in all the nations. There were similarities among nations that have similar political cultures, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The evidence indicates, however, that while PSM plays an important role in the motivation of public employees in many nations, it can have different meanings and will require different measures in different cultures.

This discussion includes only a portion of the research on PSM, which now includes at least sixty published studies (Sassler, 2013). As just described, the research involves complexities and variations about the meaning and measurement of PSM. Still, the stream of research and theorizing has sufficient consistency and momentum to establish PSM as a viable topic in public administration as well as in related fields, one that has significance for both research and practice. People interested in public service in many settings, both as employees and researchers, have a role in deciding how to define, identify, and reward the motive to engage in public service.

Motives, Values, and Incentives in Public Management

In spite of the complexities in analyzing all the possible motives, values, and incentives in organizations, the research has produced evidence of their patterns among public sector employees and the differences between public sector and private sector employees. The evidence in turn suggests challenges for leaders and managers in the public sector. Even though many public employees may value intrinsic rewards and a sense of public service, often more highly than private sector employees value them, other chapters in this book describe some experts’ concerns that the characteristics of the public sector context can impede leaders’ efforts to provide such rewards. Yet other chapters also present examples and evidence of how public organizations and their leaders can and do provide rewarding experiences for employees and enhance their motivation.

In addition, while motivation is obviously very important, motives, values, and incentives also influence other work attitudes and behaviors that are related to motivation, but not the same as motivation. The rest of this chapter describes and discusses important work-related attitudes.

Other Work-Related Attitudes

As noted earlier, motivation as a general topic covers numerous dimensions, including a variety of work-related attitudes such as satisfaction, roles, involvement, commitment, and professionalism. Motivational techniques often aim at enhancing these attitudes as well as work effort. Researchers have developed many of these concepts about work attitudes, often distinguishing them from motivation in the sense of work effort. Increasingly, in the United States and in other nations, business, government, and nonprofit organizations have encouraged their employees’ positive work-related attitudes. Part of this process has involved conducting surveys of the members of an organization (Brief, 1998; Gallup Organization, 2003; Stritch, Bullock, and Rainey, 2013; U.S. Office of Personnel Management, 2013). Many government agencies regularly measure the work satisfaction of their people.

These work-related attitudes have importance in their own right, but they are also interesting because researchers have used some of them to compare public and private managers. The following sections define and discuss major concepts of work attitudes. Later sections then describe the research on their application in the public sector and in comparisons to the private sector.

Job Satisfaction

Thousands of studies and dozens of different questionnaire measures have made job satisfaction one of the most intensively studied variables in organizational research, if not the most studied. Job satisfaction concerns how an individual feels about his or her job and various aspects of it (Gruneberg, 1979), usually in the sense of how favorable—how positive or negative—those feelings are. Job satisfaction is often related to other important attitudes and behaviors, such as absenteeism, the intention to quit, and actually quitting.

Years ago, Locke (1983) pointed out that researchers had published about 3,500 studies of job satisfaction without coming to any clear agreement on its meaning. Job satisfaction nevertheless continues to play an important role in recent research. The different ways of measuring job satisfaction illustrate different ways of defining it. Some studies use only two or three summary items, such as the following:

- In general, I like working here.

- In the next year I intend to look for another job outside this organization.

General or global measures ask questions about enjoyment, interest, and enthusiasm to tap general feelings in much more depth. They often employ multiple-item scales, with the responses to be summed up or averaged, such as the following from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss, Dawis, England, and Lofquist, 1967):

- I definitely dislike my work [reversed scoring].

- I find real enjoyment in my work.

- Most days I am enthusiastic about my work.

Specific, or facet, satisfaction measures ask about particular facets of the job. The following examples are from Smith’s “Index of Organizational Reactions” (1976):

This index also includes scales for kind of work, amount of work, coworkers, physical work conditions, financial rewards, and career future. The Porter Needs Satisfaction Questionnaire (Porter, 1962) asks respondents to rate thirteen factors concerned with fulfillment of a particular need, rating how much of each factor there is now and how much there should be. The degree to which the “should be” rating exceeds the “is now” rating measures need dissatisfaction, or the inverse of satisfaction. The need categories are based on Maslow’s need hierarchy, including, for example security needs, social needs, and self-actualization. This method has been used in some of the research on public sector work satisfaction described later.

Determinants of Job Satisfaction.

Different measures of job satisfaction use different definitions of it. Studies using different measures—and hence different definitions—often come to conflicting conclusions about how job satisfaction relates to other variables. Partly because of these variations, researchers do not agree on a coherent theory or framework of what determines job satisfaction. Research generally finds higher job satisfaction associated with better pay, sufficient opportunity for promotion, consideration from supervisors, recognition, good working conditions, and utilization of skills and abilities.

It is obviously unrealistic to try to generalize about how much any single factor affects a worker’s satisfaction. Any particular factor in a given setting contends with other factors in that setting. Various studies suggest the importance of individual differences between workers: level of aspiration, level of comparison to alternatives (whether the person looks for or sees better opportunities elsewhere), level of acclimation (what a person is accustomed to), educational level, level in the organization and occupation, professionalism, age, tenure, race, gender, national and cultural background, and personality (values, self-esteem, and so on). The influence of any one of these elements, however, depends on other factors. For example, tenure and organizational level usually correlate with satisfaction. Those who have been in an organization longer and are at a higher level report higher satisfaction. This makes sense. Unhappy people leave; happy people stay. People who get to higher levels should be happier than those who do not. Yet some studies find the opposite. In some organizations, longer-term employees feel undercompensated for their long service. Some people at higher levels may feel the same way or may feel that they have hit a ceiling on their opportunities. Career civil servants sometimes face this problem.

Researchers also look at job characteristics and job design as determinants of job satisfaction. The most prominent approach, by Hackman and Oldham (1980), also drew on Maslow’s need-fulfillment theory. These researchers report higher job satisfaction for jobs higher on the dimensions measured by their Job Diagnostic Survey, which includes the following subscales: skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, feedback from the job. Measures of these dimensions are then combined into a “motivating potential score” that indicates the potential of the job to motivate the person holding it. Hackman and Oldham’s findings conformed to a typical position among management experts—that more interesting, self-controlled, significant work, with feedback from others, improves satisfaction. The U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board (2012) used questions representing these job dimensions in their survey of over forty-two thousand federal employees. They used the results to draw conclusions about the motivating potential of federal jobs and to make recommendations about ways of improving the way jobs are designed to enhance their motivating potential.

Consequences of Job Satisfaction.

Job satisfaction has received a lot of attention for years, because it has very serious consequences. For years authors regularly pointed out that job satisfaction showed no consistent relationship to individual performance (Pinder, 2008). They typically cited Porter and Lawler’s interpretation of this evidence (1968), which pointed out that the relationship between satisfaction and performance depends on whether rewards are contingent on performance. A good performer who receives better rewards as a result of his or her good performance experiences heightened satisfaction. Yet a good performer who does not get better rewards experiences dissatisfaction, thus dissolving any positive link between satisfaction and performance. The link between performance and rewards, they concluded, plays a key role in determining the performance-satisfaction relationship. Some meta-analytical studies—analyses of many studies to look for general trends in their results—suggest that the relationship of job satisfaction to performance is generally stronger than this typical interpretation suggests (Petty, McGee, and Cavender, 1984).

Researchers have also pointed out that satisfaction shows fairly consistent relationships with absenteeism and turnover. Some studies have also found work satisfaction to be related to life satisfaction, general stress levels, and physical health (Gruneberg, 1979). These behaviors and conditions cost organizations a lot of money, and they obviously can impose hardship on individuals. Job satisfaction thus figures very importantly in organizations. Distinct from motivation and performance, it can nevertheless influence them, as well as other important behaviors and conditions in organizations.

Role Conflict and Ambiguity

In an influential book, Kahn and his colleagues (1964) argued that characteristics of an individual’s role in an organization determine the stress that the person experiences in his or her work. These ideas about organizational role characteristics are meaningful for anyone working in an organization or profession. A number of “role senders” seek to impose expectations and requirements on the person through both formal and informal processes. These role senders might include bosses, subordinates, coworkers, family members, or anyone else who seeks to influence the person’s role. If these expectations are ambiguous and conflicting, the stress level increases. Researchers developed questionnaire items to measure role conflict and role ambiguity (House and Rizzo, 1972; Rizzo, House, and Lirtzman, 1970). Role ambiguity refers to a lack of clear and sufficient information about how to carry out one’s responsibilities in the organization. The role ambiguity questionnaire asks about clarity of objectives and responsibilities, adequacy of a person’s authority to do his or her job, and clarity about time allocation in the job.

Role conflict refers to the incompatibility of different role requirements. A person’s role might conflict with his or her values and standards or with his or her time, resources, and capabilities. Conflict might exist between two or more roles that the same person is expected to play. There might be conflict among organizational demands or expectations, or conflicting expectations from different role senders. The survey items about role conflict ask whether there are adequate resources to carry out assignments, and whether others impose incompatible expectations.

The two role variables consistently show relationships to job satisfaction and similar measures, such as job-related tension (Miles, 1976; Miles and Petty, 1975). They also relate to other organizational factors, such as participation in decision making, leader behaviors, and formalization. Individual characteristics such as need for clarity and perceived locus of control (whether the individual sees events as being under his or her control or as being controlled externally) also influence how much role conflict and ambiguity a person experiences. These concepts are important by themselves, because managers increasingly concern themselves with stress management and time management. Managing one’s role can play a central part in these processes.

Job Involvement

In observing increasingly technical, professional, and scientific forms of work, researchers find differences among individuals in their involvement in their work. For some people, especially advanced professionals, work plays a very central part in their lives. Researchers measure job involvement by asking people whether they receive major life satisfaction from their jobs, whether their work is the most important thing in their life, and similar questions. Job involvement is distinct from general motivation and satisfaction but resembles intrinsic work motivation. It figures importantly in the work attitudes of highly professionalized people who serve in crucial roles in many organizations. The concept has also played an interesting role in the research on public managers, as described further on.

Organizational Commitment

The concept of organizational commitment has also figured in research on public and private managers (discussed later in this chapter). Individuals vary in their loyalty and commitment to the organizations in which they work. Certain people may consider the organization itself to be of immense importance to them, as an institution worthy of service, as a location of friends, as a source of security and other benefits. Others may see the organization only as a place to earn money. Professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and scientists often have loyalties external to the organization—to the profession itself and to their professional colleagues.

Scales for measuring organizational commitment ask whether the respondent sees the organization’s problems as his or her own, whether he or she feels a sense of pride in working for the organization, and similar questions (Mowday, Porter, and Steers, 1982). Studies also show the multidimensional nature of commitment. For example, Angle and Perry (1981) showed the importance of the distinction between calculative commitment and normative commitment to organizations. Calculative commitment is based on the perceived material rewards the organization offers. In normative commitment, the individual is committed to the organization because he or she sees it as a mechanism for enacting personal ideals and values.

Balfour and Wechsler (1996) further elaborated the concept of organizational commitment in a model for the public sector based on a study of public employees. Their evidence suggested three forms of commitment. Identification commitment is based on the employee’s degree of pride in working for the organization and on the sense that the organization does something important and does it competently. Affiliation commitment derives from a sense of belonging to the organization and of the other members of the organization as “family” who care about one another. Exchange commitment is based on the belief that the organization recognizes and appreciates the efforts and accomplishments of its members.

Professionalism

For years, sociological researchers have studied the way in which highly trained specialists control complex occupations. Technological advances have made certain valuable types of work increasingly complex and difficult to apprehend. Specialists in these areas must have advanced training and must maintain high standards. Only specialists, however, have the qualifications to establish and police the standards. From the point of view of society and of large organizations, these factors raise problems involving monopolies, excessive self-interest, and mixed loyalties. Government and business organizations also face challenges in managing the work and careers of highly trained professionals.

Researchers have offered many definitions of the term profession, typically including these elements:

- Application of a skill based on theoretical knowledge

- Requirement for advanced education and training

- Testing of competence through examinations or other methods

- Organization into a professional association

- Existence of a code of conduct and emphasis on adherence to it

- Espousal of altruistic service

Occupational specializations that rate relatively highly on most or all of these dimensions are highly “professionalized.” Medical doctors, lawyers, and highly trained scientists are usually considered advanced professionals without much argument. Scholars usually place college professors, engineers, accountants, and sometimes social workers in the professional category. Often they define less-developed specializations, such as library science and computer programming, as semiprofessions, emerging professions, or less professionalized occupations.

In turn, management researchers analyze the characteristics of individual professionals, because they play key roles in contemporary organizations. They point out that, as a result of their selection and training, professionals tend to have certain beliefs and values (Filley, House, and Kerr, 1976):

- Belief in the need to be expert in the body of abstract knowledge applicable to the profession

- Belief that they and fellow professionals should have autonomy in their work activities and decision making

- Identification with the profession and with fellow professionals

- Commitment to the work of the profession as a calling, or life’s work

- A feeling of ethical obligation to render service to clients without self-interest and with emotional neutrality

- A belief in self-regulation and collegial maintenance of standards (that is, a belief that fellow professionals are best qualified to judge and police one another)

Members of a profession vary on these dimensions. Those relatively high on most or all are highly professional by this definition.

The characteristics of professions and professionals may conflict with the characteristics of large bureaucratic organizations. Belief in autonomy may conflict with organizational rules and hierarchies. The situation at the Brookhaven National Laboratory described at the beginning of Chapter Eight is an example of such conflict. The scientists chafed under the new rules and procedures imposed on them by administrators seeking to enhance safety and public accountability. Emphasis on altruistic service to clients can conflict with organizational emphases on cost savings and standardized treatment of clients. Identification with the profession and desire for recognition from fellow professionals may dilute the impact of organizational rewards, such as financial incentives and organizational career patterns. Professionals might prefer an enhanced professional reputation to salary increases, and they might prefer their professional work to moving “up” into management. Without moving up, however, they hit ceilings that limit pay, promotion, and prestige. Some studies in the past have found higher organizational formalization associated with higher alienation among professionals (Hall and Tolbert, 2004).

Conflicts between professionals and organizations do not appear to be as inevitable as once supposed, however. Certain bureaucratic values, such as emphasis on the technical qualifications of personnel, are compatible with professional values (Hall and Tolbert, 2004). For example, professionals may approve of organizational rules on qualifications for jobs. Professionals in large organizations may be isolated in certain subunits, such as laboratories, where they are relatively free from organizational rules and hierarchical controls (Bozeman and Loveless, 1987; Crow and Bozeman, 1987; Larson, 1977). Certain professionals, such as engineers and accountants, may want to move up in organizations in nonprofessional roles (Larson, 1977; Schott, 1978).

Golden (2000) describes how professionals in certain federal agencies during the Reagan administration disagreed with many of the policies of the Reagan appointees who headed their agency, but regarded it as their professional obligation to discharge those policies effectively, once they were decided and established. Berman (1999) found no major differences in the levels of professionalism expressed by public, private, and nonprofit managers, although he found indications of differences in the contexts that influence their professional orientations. This conception of professionalism among managers differs from the concept of highly professional occupations such as law and medicine, but Berman’s finding makes the point, as did Brehm and Gates (1997), that professionalism can be an important motivating factor among many managers and employees in the public sector.

Management writers offer some useful suggestions about the management of professionals. They prescribe dual career ladders, which add to the standard career path for managers another for professionals, so that professionals can stay in their specialty (research, legal work, social work) but move up to higher levels of pay and responsibility. This relieves the tension over deciding whether one must give up one’s profession and go into management. Some organizations rotate professionals in and out of management positions. Some government agencies have adopted the policy of rotating geologists in administrative positions back into professional research positions after several years. Some organizations also allow professionals to take credit for their accomplishments. For example, they allow them to claim authorship of professional research reports rather than requiring that they publish them anonymously in the name of the agency or company. Organizations can also pay for travel to professional conferences and in other ways support professionals in their desire to remain excellent in their field.

Motivation-Related Variables in Public Organizations

Researchers have made comparisons on a number of motivation-related variables between public and private samples, shedding some light on how the two categories compare.

Role Ambiguity, Role Conflict, and Organizational Goal Clarity

For some work-related attitudes, researchers have found few differences between managers in public and private organizations. This has been the case with the most frequent observation in all the literature on the distinctive character of public management: public managers confront greater multiplicity, vagueness, and conflict of goals and performance criteria than managers in private organizations do. There is a fascinating divergence between political economists and organization theorists on the validity of this observation. Political scientists and economists tend to regard this goal complexity as an obvious consequence or determinant of governmental (nonmarket) controls, whereas many organization theorists tend to regard it as a generic problem facing all organizations.

Little comparative research directly addresses this issue, however. Rainey (1983) compared middle managers in government and business organizations about the role conflict and role ambiguity items described earlier, asking questions about the clarity of the respondents’ goals in work, conflicting demands, and related matters. The government and business managers showed no differences on these questions nor on questions about whether they regarded the goals of their organization as clear and easy to measure. More recent surveys have confirmed these results (Bozeman and Rainey, 1998; Rainey, Pandey, and Bozeman, 1995). One explanation may be that public managers clarify their roles and objectives by reference to standard operating procedures, whether or not the overall goals of the organization are clear and consistent.

These findings point to important challenges for both researchers and practitioners in further analyzing such issues as how managers in various settings (such as public, private, and hybrid organizations) perceive objectives and performance criteria; how these objectives and criteria are communicated and validated, if they are; and whether these objectives and criteria do in fact coincide with the sorts of distinctions between public and private settings that are assumed to exist in our political economy. Wright (2004) reports evidence that state government employees who perceive greater clarity of work and organizational goals also report higher levels of work motivation, so the frequent generalizations about vague goals in public organizations do not mean that leaders and managers in government cannot and should not continue efforts to clarify goals for organizational units and employees.

Work Satisfaction