CHAPTER 3

Governing Innovation in Practice: The Role of the Top Management Team

Companies that compete through new products or services have, of necessity, a new product development system, organization, and process. These have generally been in place for a decade or more and are regularly updated as conditions change and new practices and processes are developed and adopted. As part of these updates, senior functional and business managers may change the allocation of responsibilities for the planning, design, production, and introduction of new offerings. They also invest in new tools and work approaches, and they regularly introduce new targets in terms of new product quality, cost, and lead times. In many companies, this process now works reasonably well and smoothly. Relying on the second line of command to supervise all these activities, the top management team of large companies may not be involved directly, except when there are significant changes, which can include both new opportunities and failures.

But despite having a good product development process in the company, CEOs often complain about the relative lack of market and financial impact of innovation efforts, at least given the investments. New products are developed, for sure, but the results are often disappointing when compared to the predictions and promises of product managers and others responsible for the introduction of innovations. New products may provide a benefit to customers and help to maintain the company's profitability, but too few are real “game changers.” How many of these CEOs, reading constantly about Apple's series of market hits, ask themselves how they can emulate the success of the Silicon Valley giant? And reflecting on the fate of Nokia, that troubled innovation star – at least in the eyes of the business media – how many wonder about what suddenly happened to the mobile phone pioneer's top management team? How can one explain why these brilliant Finnish leaders, who could launch new phones with amazing frequency, somehow took their eye off the ball and missed a deep turn in the smartphone market?

Well, these questions highlight the fact that even if a company has a competent new product development process, this does not mean that it will be able to develop a range of market-winning innovations and sustain a high level of creativity and productivity over time. Neither does it guarantee that the company will be able to detect and react adequately to all opportunities and threats. As we stressed earlier, although the new product development process was designed to enable product developers to work across the company's functions and activities, the scope of innovation is both richer in results – for example, when it leads to the creation of new business models – and more complex because it involves a combination of “hard” and “soft” elements. Because of this complexity, because innovation affects the entire company, no process or set of processes can be sufficient to meet all the demands. However, the existence of satisfactory new product development processes makes it possible to implement a comprehensive innovation management system – steered by the C-suite – which is conducive to generating streams of market-leading innovations and avoiding competitive pitfalls.

Setting up a formal innovation management system requires proactive, personal engagement by the top team. Unfortunately, the C-suite is often simply too busy with strategic, financial, and operational issues to devote time to steering innovation on a day-to-day basis and creating that unique environment and culture. The system in place generally reflects past legacies that are seldom challenged by management. Occasionally, a new CEO or CTO will launch an “innovation revival” campaign, but it is often limited in scope and duration. Old habits tend to survive!

It is therefore healthy practice for the top management team to regularly engage in a comprehensive reassessment of the company's innovation system – how it is organized, its processes, environment, and culture – and to introduce new innovation governance guidelines. The role of the top team in this effort is critical. It goes beyond making minor structural changes and appointing new people in charge of existing departments. Governing innovation effectively involves at least six priorities:

- Setting an overall frame for innovation by clarifying a vision and mission for innovation, proposing a set of values to guide innovation activities and auditing current performance.

- Defining how the company will identify sources of value from innovation, how it will create value, and how it intends to capture value.

- Choosing organizational models for the allocation of primary and supporting governance responsibilities for innovation, and setting up dedicated process management mechanisms.

- Establishing priorities and allocating resources for innovation as part of an explicit innovation strategy and plan in support of the company's objectives.

- Identifying and overcoming current obstacles in the company's organizational system and sources of resistance in order to build a lasting innovation environment.

- Monitoring and evaluating results on an ongoing basis, and setting up a process to address conflicts of interest within the top management team in order to make innovation sustainable.

We shall now explore each of these six innovation governance areas in more detail.

Setting an Overall Frame for Innovation

In some companies, the innovation tradition and culture seems almost like a magic potion that is part of their DNA and ensures that all activities focus on innovation – think of Apple, Google, P&G, or 3M. But even in such companies, it is useful for top management to reflect at regular intervals on how innovation can contribute to the realization of the company's overall mission and vision. This requires a willingness to align business and innovation visions, to propose and enforce a set of values that are conducive to innovation, and to conduct comprehensive innovation audits.

P&G convincingly illustrates the link its management sees between its overall vision of innovation and its culture. Its motto “the consumer is boss”1 (see box) shows that visions and missions are not something ethereal. They can lead to very concrete actions in favor of innovation and shape the values and culture of the company. In framing innovation in this way, P&G's top management team, under the inspired leadership of A.G. Lafley, demonstrated an innate sense of innovation governance.

Aligning Business and Innovation Visions

Aligning visions means discussing and agreeing on what management wants to achieve business-wise and how innovation can help achieve it. This is vital to ensure that innovation is closely tied to the company's overall mission. The company's vision – how it wants to see its future – can generally be expressed in the form of three basic questions:

- Who do we want to be? What kinds of activities do we want to pursue and what do we want to stand for as a company vis-à-vis our stakeholders? (This defines the company's desired identity.)

- What business do we want to be in? Which segments and customers do we want to serve as a priority? (This delineates the company's desired business boundaries and focus.)

- What do we want our offerings to mean to our customers? How do we intend to become the preferred supplier for our customers? (This provides a set of competitive values for the company.)

Similarly, the company's innovation vision – hence the scope of management's innovation governance mission – can be expressed in the form of the three questions on the content of innovation that we proposed in Chapter 1:

- Why innovate? What concrete benefits are we trying to achieve given our current market and competitive position?

- Where to innovate? In what areas should we concentrate our efforts beyond our traditional product renewal activities?

- How much to innovate? How ambitious and open to risk should we be, and indeed can we afford to be, and for what objective?

These are all questions worth asking regularly, even if nothing special is happening in the company and its markets. This can be done, for example, as part of an annual top management off-site strategy retreat. Formally reviewing the mission and purpose of innovation and its desired focus may generate interesting new perspectives. But even if it only confirms current management views, it will at least ensure that all members of the C-suite are aligned behind common beliefs and a shared innovation vision and can therefore speak with one voice to the rest of the organization.

Expressing Innovation-enhancing Values

These innovation-specific management discussions may also be useful for reaffirming a set of specific values concerning innovation. It is therefore the role of the CEO, and his/her direct reports, to regularly review and specify the values they want to promote, values that can then be broadcast through management publications, speeches, and individual performance reviews. Of course, values should not be changed too often. However, they deserve to be clarified if they are too simplistic.

For example, including “innovation” or “innovativeness” in the company's core values – as found frequently in annual reports and other company publications – does not really say much. Management needs to express in a concrete and explicit fashion what this means practically in terms of personal attitudes and interactions.

Some of these values can be expressed as short, punchy sentences that can do a lot to promote the kind of culture management aspires to create. P&G's “the consumer is boss” motto, noted earlier, indeed conveys a clear and simple message about the company's main focus. The same can be said about Steve Jobs' early slogan at Apple – “Let's Be Pirates” – which called for a rebellion against the dominance of the WinTel PC.2 Similarly, Andy Grove's famous book title – Only the Paranoid Survive – was effective in conveying to all at Intel the importance of humility and the conviction that no innovation battle is won forever.

Google provides a good example of a number of innovation-oriented values because they sustain its unique environment and culture – that is, unique in the type of people the company hires, as well as in their attitudes and ambitions. And each of these values, including its most famous one – “don't be evil” – is broken down into concrete elements.3

When a company has developed a strong innovation culture and supporting values, keen external observers of that company are generally able to highlight the main elements of the culture, even though management may not have specifically broadcast them as such. This is the case with Apple's culture as viewed by management expert Gary Hamel, who adds: “I can't even be sure whether the values I've outlined [see box] are the ones that really drive Apple – but if they aren't, they should be! For me, the case of Apple is just a convenient and plausible vehicle for driving home a fundamental truth: You can't improve a company's performance without improving its values.”4 This last statement is so crucial, particularly in terms of innovation performance that it should be posted in gold letters in the CEO's corner office, in the C-suite meeting room and in the boardroom.

Auditing and Improving Innovation Performance

Finally, setting the frame for innovation includes conducting a thorough innovation audit to establish the starting base before launching improvement programs. This allows management to understand how the process currently works in reality, what its deficiencies are, and what general obstacles – whether organizational or cultural – are hindering the company's innovation effectiveness.

A thorough audit generally includes some benchmarking of the company's current innovation practices against those of companies with a great innovation track record. The results of this benchmarking may be instrumental in convincing management, and the wider organization, that the company needs to change and in indicating major areas where such change is warranted. It is also a good way to silence the skeptics and proponents of the status quo. Innovation audits can be outsourced – a number of specialized consultants offer their benchmarking services. But it can also be carried out internally using an established framework,5 ideally focusing on the whole value creation process – business design, value identification, and value realization. Maximizing value creation is indeed one of the most important management priorities in innovation governance, as we will see below.

Many companies participate in peer-to-peer benchmarking through membership in organizations such as the Product Development and Management Association (PDMA) and the International Association for Product Development (IAPD). These organizations have helped innovators to learn from one another and in many cases have provided a venue for the adoption of new and emerging practices. They have also enabled members to create a network within which more formal benchmarking visits have taken place as workshop participants identify peers with whom they can explore specific practices.

Tetra Pak, the world's leader of packaging systems for liquid food, provides a good illustration of the power of benchmarking. The company, whose innovation governance system will be presented in Chapter 11, was founded on a radical innovation, Tetra-Brik®, an effective carton packaging system using aseptic technology for long-life milk and juices. The company was managed for many years by its charismatic owner, Ruben Rausing, and later on successively by his two sons, Hans and Gad. Each of them promoted a creative environment, particularly in R&D. But for years Tetra Pak was unable to translate its superb R&D capabilities into successful new products because it lacked adequate processes to sense the market, select the best ideas, and manage new product development projects time- and cost-effectively.

So, in 1996 management set up a small steering group of four senior managers whose mission was to recommend steps to improve the company's innovation performance. This small group was directed by the very senior vice president in charge of European operations, Bo Wirsén. As a group, they knew, from having experienced them, many of the deficiencies of their innovation process, but they lacked references about best practices. This prompted Wirsén to visit a number of companies that had impressed him.6

What was unique in Tetra Pak's initial audit was that such a senior member of the top management team took the initiative to conduct these benchmarking visits himself. This gave him strong personal credibility when improvement targets were decided. It also provided him with new insights into critical innovation success factors that an outsourced benchmarking exercise would not necessarily have provided. For example, through his benchmarking visits Wirsén realized that the company might benefit from creating two new functions with a strong role to play in innovation – chief technology officer and strategic marketing officer. At Tetra Pak, this initial benchmarking exercise was used to kick off an innovation improvement program. But it was not referred to later or used as a formal auditing system.

DSM, a global life sciences and materials sciences company, whose governance system will be described in Chapter 10, provides another good example of the importance of starting an innovation improvement program with a thorough audit. When top management decided to change the company's innovation governance system in 2006 and set up a corporate innovation center, it entrusted responsibility for the center to a high-level chief innovation officer (CIO), Rob van Leen, a former group vice president for food and nutrition. Starting from scratch – the company had thus far managed innovation in traditional ways, through R&D – Van Leen felt the need to build a common language and set a base through a company-wide auditing exercise. Some of DSM's groups had a good innovation track record, others less good. All had to go through a thorough benchmarking exercise structured around a number of critical processes and capabilities, an initiative that some of them resented as being too administrative. The outcome of this exercise was a mind opener to all, as Van Leen noted (see box).7

Interestingly, this audit was turned into a real management tool. First, Van Leen distributed the results widely, including to the company's board of management, which forced some of the skeptics to take it seriously. He also decided to redo the assessment at regular intervals to measure progress. But the most powerful use of the tool was to initiate regular review meetings around this audit between the controller of the innovation center and members of the management teams of each business group. During these meetings, progress and remaining obstacles were discussed, together with some of the business group's most meaningful innovation projects. The review meetings were then documented in a detailed and widely distributed report. These practices have created a propensity for emulation among business group managers – the better performing groups want to stay on top and the poorer ones feel the need to show progress.

Defining How to Generate Value from Innovation

It is a truism that innovation is about turning market opportunities into value. In established management theories, this means identifying, evaluating, creating, and – arguably the most difficult step – capturing value.

Without a clear mandate from top management, most companies will naturally search for value within their current industries and markets. In this way, value is most usually generated by developing and introducing new products or services that replace or complement existing product lines. Some of these products or services will be incrementally better or cheaper; others will be more radically new. But their common denominator is that they remain, for the most part, within the company's existing industry value chain and keep converging toward the same competitive arena, the same “red ocean” as Kim and Mauborgne put it.8 This is why the potential value created by most new products is seldom fully captured.

In fact, it is not rare to hear CEOs complain that the new products or services generated by their organization are often less profitable than the original ones on which the company built its growth. These new products or services may revitalize current market segments, but they do not lead to a sustainable competitive advantage since they are quickly imitated or superseded by competitors' entries. An important element of top management's innovation governance mission is therefore to stop this “new product merry-go-round” and initiate new ways to redefine value.

Redefining value requires broadening the scope of the search for opportunities, as we proposed in Chapter 1. This can be done by introducing a totally new basis of competition, as well as by creating new market space using previously neglected yet critical attributes – Kim and Mauborgne's “blue ocean strategy.”9 It can also result from a systematic exploitation of opportunities to redesign the industry value chain – some authors call it the “value constellation” or “value network” – to one's advantage, or in some cases to create a totally new value chain. Such a move requires a thorough understanding of industry value chain dynamics, alternative business models and competitors' blind spots.

Charlie Fine of MIT, author of the best-seller Clockspeed,10 emphasizes the need to understand the dynamic relationships between suppliers, partners, and other industry value chain players to identify opportunities to take over parts of the value chain and therefore increase total profits. In his seminar Driving Strategic Innovation, conducted jointly with IMD, he encourages senior managers to identify strategic opportunities in their industry value chain through a systematic three-step approach:

- Your industry's technologies (S-curves) and its innovation pattern?

- Your customers?

- Your competitors?

- Your industry structure?

- Your governmental and regulatory agencies?

- Your environment?

- What are the key elements in your industry value chain?

- Who has power in the chain?

- Who makes the profits in the chain?

- What are the sources of power and profit in the chain (technology, brand, etc.)?

- What are the key dynamic processes influencing the power structure in the chain?

- Where is the locus of innovations in the chain?

- What is the clock speed of each element in the chain and what are the drivers?

- Review your insourcing/outsourcing options and decisions (make/buy choices and/or vertical integration).

- Analyze your partner selection options and decisions (e.g. choice of suppliers and partners for the chain).

- Evaluate your contractual relationship options and decisions (arm's length, joint venture, long-term contract, strategic alliance, equity participation, etc.).

Apple provides a striking example of this value creation strategy. Its financial success is in large part the result of having recognized – before any of its hardware competitors – the importance of content for sustainable value creation and of having cornered this value through its novel and proprietary iTunes system and its focus on smartphone applications. Apple's winning value identification strategy consisted of controlling the marketing, sales, and distribution of other companies' content by making its customers and suppliers captive, thus capturing a large part of the value of the content. This strategy is largely attributed to Steve Jobs and his top management team. They fully exercised their innovation governance role, which was to steer the company toward greener pastures – integrating hardware, software, and content – rather than leaving it to compete against the conventional pure hardware business model of its early competitors.

Choosing an Innovation Governance Model

As we stated earlier, steering, promoting, and sustaining innovation in the broadest sense of the term – not just the new product development process – is a major task that spans all company functions and organizational units. As such, it needs to be handled directly by the CEO or entrusted explicitly by the top team either to a very senior leader or to a group of managers fully empowered to exercise that responsibility. That assignment must be public, i.e. everyone in the organization should know who is in overall charge of innovation and how that overall responsibility is redistributed across the organization. Any change in the allocation of responsibilities – because changes are bound to happen over time – must also be explained and broadcast.

In our research, we have identified nine models for the primary allocation of overall responsibility for innovation. Some companies also use one or another of the same nine models to support the primary model. As we shall describe in Chapter 4, in some of these models overall responsibility for innovation is assigned to a single individual. The CEO may hold this responsibility, which is most likely to be the case if he/she is the company founder. Other individuals who may hold this role are the chief technology or research officer (CTO or CRO), a dedicated chief innovation officer (CIO) – whose actual title can be quite fancy like ‘Chief Yahoo’ – or a high-level innovation manager. In the financial industry the chief information officer can play this role; in other non-manufacturing sectors another CXO or a business unit manager can assume this responsibility. There are also models in which a group of leaders takes on responsibility for innovation collectively, whether they represent a subset of the top management team or constitute a high-level cross-functional steering group or a network of “champions.”

There are therefore a number of models to choose from, each with its own advantages and shortcomings. It is top management's responsibility to weigh up the pros and cons of each model and how it suits the company's position and leadership resources. The choice will indeed depend on the personal preferences of the top team – do they want to remain involved personally or do they prefer to delegate responsibility to the level below? It will also reflect the type of innovation that is pursued – for example, if technology is the main driver, this would justify allocating overall responsibility to the chief technology or research officer – and of course the availability of suitable candidates for the job. Given that choice is available, top management would be well advised to refrain from sticking to the model they adopted years ago, or choosing the one most frequently found in their industry, for example the CTO model in the engineering industry.

Choosing a suitable organizational model is essential, but it is equally important to realize that conditions change. It is therefore good practice to review regularly the adequacy of the model in use given the company's changing market situation, leadership structure, and strategy.

In Chapter 4 we will explain the nature and purpose of these organizational models and in Chapters 5 and 6 we will describe these models individually and discuss how effective they seem to be, at least in the perception of companies that have adopted them.

Establishing Innovation Priorities and Allocating Resources

Steering innovation, i.e. deciding on the company's priorities concerning where, how much, and in what domain to invest in innovation, is one of the key governance missions of top management. It is generally done, at least indirectly, through project portfolio decisions. Managers understand the value of seeing the portfolio as a way of distributing resources across incremental, platform, and “radical” projects.

Going Beyond Traditional Portfolio Management Approaches

Business units typically identify their most attractive projects and management can then consolidate the various portfolios to check whether, once combined, they provide the right balance of growth, margin, and risk. Such a bottom-up approach is sometimes complemented by the addition of a few corporate projects resulting from a proactive and ambition-led, top-down innovation push. The sum of business projects included in the consolidated portfolio reflects the company's implicit innovation strategy.

The limitation of this approach is that it allocates corporate resources on the basis of the perceived attractiveness of projects as seen by business units, since business portfolios tend to weigh heavily in the company's total resource allocation. This business project attractiveness often reflects the perceived level of competitive urgency of the projects and their impact on short-term business performance in terms of sales and profitability. In other words, unless the portfolio includes proper guidelines for investment, “game-changing” projects with a long-term impact on the company are at risk of being short-changed, thus weakening the implementation of the company's vision.

To offset that risk and ensure that the strategy will meet the company's innovation priorities, and to provide investment guidelines, it is useful for top management, as a first step, to decide on how much the company should and can afford to spend on innovation in general and on innovative projects in particular. This will determine an overall “envelope” of resources for innovation, which can then be compared with other investment funding needs. This envelope should cover not only R&D – as a total amount and as a percentage of sales – and other product development expenses (the upstream investments) but also investments in manufacturing capacity and commercialization (downstream investments).

Allocating Resources between Different Innovation Thrusts

This broad “innovation envelope” should then be allocated among the different types of innovations being pursued, and this is the second step in the resource allocation process. To do so, it is necessary to characterize the main innovation thrusts being pursued. The book Innovation Leaders11 proposed to do so by combining broad options derived from the questions listed in Chapter 1:

- Why innovate? (Innovation objective)

Innovations can be pursued for two broad objectives: to energize and expand a current business in its existing markets or to create a totally new business. These objectives can be combined. - Where to innovate? (Innovation scope or focus)

Innovations can focus on products or services – introducing a new “black box” or stand-alone service – or, alternatively, on developing a new business model or business system. - How much to innovate? (Innovation intensity level)

Innovations can be incremental in the changes brought to current products, services, or processes, or they can be more radical, leading to completely new product and service concepts. - With whom to innovate? (Innovation boundaries)

Innovations can be developed and implemented internally, using the company's capabilities and resources, or externally through deliberate collaboration with partners.

Note that both innovation intensity and boundaries – if restricted to an either/or option (incremental or radical; internal or external) – are always subject to debate. An innovation that is radical in one company may be characterized as incremental by a competitor. The level of innovation is relative to the reference models of the beholder. Also, innovations are rarely conducted only internally – external factors like suppliers are usually involved – which means most innovation projects fall somewhere between the two extremes.

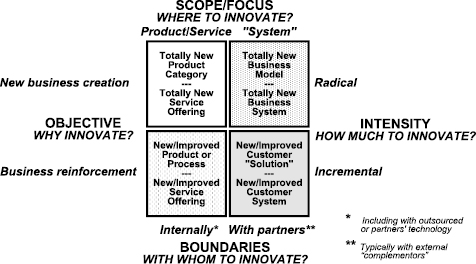

These four dimensions can be combined, as shown in Figure 3.1, into four entirely different innovation thrusts. Top management should recognize them explicitly, choose the ones that it will pursue as a priority, and use them to characterize and communicate its innovation strategy and investments, which will usually come from a combination of the chosen thrusts.

Figure 3.1: Typology of Innovation by Strategic Focus

These four thrusts propose a simple typology of innovation choices:

- The internal development and launch of a new and/or improved product, process, or service offering, typically to grow and reinforce the current business in an incremental innovation mode.

- The internal development of a totally new product category or service offering, typically to grow and create a totally new business, next to the existing ones, in a radical innovation mode.

- The development and launch, together with selected partners, of a totally new business model or integrated system, typically to grow and create a new business in a radical innovation mode.

- The development and launch, together with partners or complementors, of a new and/or improved customer solution or customer system, typically to grow and reinforce the current business in an incremental innovation mode.

This classification reflects the fact that, from a management point of view, developing a “black-box” product or service is very different – and carries a different type of risk – than introducing a new business model or business system, or even a complex product solution. Indeed, whereas the development of a new product or service is often the result of an internal process, even though it may involve the use of outsourced technology and suppliers, the development of a radically new business model or system often requires the cooperation of several external partners, outsourcing suppliers, or complementors.

As mentioned earlier, these four thrusts are not mutually exclusive – innovations can be pursued simultaneously across several of these areas. Once displayed on a two-by-two matrix (refer to Figure 3.1), they provide a useful framework and lens for examining the complex reality of innovation thrusts.

Ideally, once the overall innovation envelope has been established, management should propose how the envelope should be split between the four quadrants:

- How much the company should spend internally on incremental projects to reinforce the current businesses.

- How much it should invest, again internally, in radical projects to create a totally new business next to the existing ones.

- How much it should commit to attempts to introduce a radical new system or business model with partners.

- How much it should devote to the creation of incrementally innovative customer solutions, once again with partners.

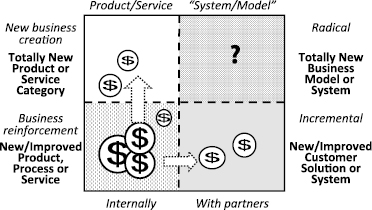

Management can now go back to the original project portfolio and position specific innovation projects in the four quadrants to see whether the investments that they represent add up to the predetermined envelopes (refer to Figure 3.2). If they do not – if some quadrants lack projects – then management can indicate where additional efforts are expected (see arrows on Figure 3.2) and how much they represent in terms of new resources to be committed, thus starting a search for new opportunities.

Figure 3.2: Portfolio of Innovation Projects by Type

This approach allows management to introduce an innovation dimension in the traditional project portfolio approach by: (1) indicating how the various objectives of the company's innovation strategy will be funded; (2) specifying how much management plans to spend on innovation in general, and on activities that will reinforce current businesses vs. innovative efforts to create entirely new activities; (3) providing guidelines on how much should be spent on each main type of innovation; and (4) suggesting new market domains that need to be explored as a priority for these new activities.

Three general remarks can be made on this definition of priorities and management allocation of resources.

First, in their effort to reinforce their current market position, most business management teams tend to focus on only a few areas where innovation can make a difference, i.e. new better and cheaper products, new technologies, and new production processes. It is therefore useful for the C-suite to stress the importance of other reinforcing innovations, for example in new business models, in the supply chain and/or value chain, in service, in marketing and channel distribution, and the like. These could stimulate business managers to look more broadly at innovation, as recommended in Chapter 1.

Second, deciding how much to invest by type of innovation, i.e. incremental vs. radical, determines how much risk the company is willing to take (or avoid). By addressing this issue directly – for example, by setting up specific envelopes by quadrant – management can establish a general company policy that may be helpful when the company is leaning too far to one side or the other. For example, some managers always seem to look for breakthroughs. They behave as if incremental innovations such as product derivatives are not worth their efforts, with the result that they miss major market and profit opportunities. Other managers, in contrast, stay permanently within their comfort zone and shy away from risky developments. In each case, it will help if management specifies, for each business, what it considers as the right balance between incremental and radical innovation.

Third, and finally, defining a policy on open innovation is an important element of an innovation strategy, particularly in the new social network environment and with the growing importance of crowdsourcing. It goes beyond a simple exhortation to build upon external ideas and competencies. A policy on open innovation ought to specify:

- the domains where external cooperation is desirable;

- the boundaries of cooperative deals and the types of partners to be considered off-limits;

- considerations on the protection of intellectual property; and

- indicators to measure the level of achievement of the policy.

By specifying this type of broad resource allocation – covering not only R&D but also other upstream and downstream investments – management can achieve three important benefits of good governance:

- Send a clear message regarding the company's priorities.

- Set the frame for the development of its new business activities.

- Ensure that these activities will be adequately funded.

Overcoming Obstacles and Building a Favorable Innovation Environment

As Gary Hamel suggested, there is generally a strong correlation between innovation culture and innovation performance. The success of Google, for example, cannot be separated from the emphasis the company puts on its “can-do” entrepreneurial culture or from the concrete steps management takes to sustain it. Google's famous rule – modeled on 3M's “15% rule” – that allows people to pursue their own ideas for up to 20% of their time, is just one example of the company's innovation-enhancing environment. By contrast, some excellent companies with huge technological resources never seem to reach the status of top performers in their industry, largely because of an internal culture that stifles innovation.

Innovation calls for openness, experimentation and risk taking, and, above all, cooperation and constructive challenges across functions and organizational units, and all of these aspects need to be explicitly encouraged by management. In a seminal article, two Harvard Business School professors12 summarized the lessons learned from a two-day colloquium held at their school on “Creativity, Entrepreneurship, and Organizations of the Future.” The colloquium gathered over a hundred people who were “deeply concerned with the workings of creativity in organizations,” including research scholars and business leaders from companies whose success depends on creativity – such as design consultancy IDEO, technology innovator E-Ink, internet giant Google, software specialist Intuit, and pharmaceutical leader Novartis among others. Even though the colloquium focused on creativity, it provided a number of lessons that apply more generally to innovation. The lessons can be summarized in a number of concrete exhortations to senior management to:

- Draw on the right minds:

- Tap ideas from all ranks

- Encourage and enable collaboration

- Open the organization to diverse perspectives.

- Bring process to bear carefully:

- Map the phases of creative work

- Manage the commercialization hand-off

- Provide paths through the bureaucracy

- Create a filtering mechanism.

- Fan the flames of motivation:

- Provide intellectual challenge

- Allow people to pursue their passions

- Be an appreciative audience

- Embrace the certainty of failure

- Provide the setting for “good work.”

But creating this type of open and creative environment may not be sufficient. Management must also address several organizational and cultural obstacles that hinder innovation. We have observed them – the seven vicious innovation killers – in a wide range of companies and propose a number of antidotes to each below.

Killer # 1: Excessive Operational Pressure

The first innovation killer, present in most companies, is the excessive pressure put on managers as a result of their operational and organizational responsibilities and of a constant fire-fighting atmosphere within the business. These pressures tend to be reinforced by a management performance evaluation system that encourages short-term results. Managers may be willing to spend time on innovation, but there may simply not be enough time for these innovative undertakings in many organizations.

Management can counteract this pressure in two ways, which have proved to be effective antidotes.

First, the pressure can be alleviated if management identifies, appoints, and guides dedicated and passionate innovation coaches to motivate, challenge, and support local innovation teams. These champions are generally found among younger high-potential managers. To be effective, these coaches or champions should be highly energetic as well as socially skilled so that they are not viewed as interfering in the business or “bossing” the local managers. They should also be practical and resourceful in identifying bottlenecks, suggesting solutions, proposing best practices and tools, and generally helping business managers move forward with their innovation agenda and projects.

Second, management can create a counter-pressure in favor of innovation, for example by introducing specific innovation performance measures in every manager's balanced scorecard. This assumes, of course, that management is true to the very principle of balanced scorecards – in other words that it judges managers on all dimensions of the scorecard and not just on financial or budget performance. Once managers are penalized in their personal performance review for letting their innovation activities lag behind, even if they make their budget, it is probable that they will revive their interest in these undertakings and find a better balance of their time and efforts.

Killer # 2: Fear of Experimentation and Taking Risks

This second innovation killer usually results from unrealistic financial benchmarks or from a culture that does not tolerate failure. Financial benchmarks – for example, assigning unreasonably high hurdle rates of return on totally new and innovative projects – are an innovation killer because they may discourage people from undertaking uncertain projects. Note that full-blooded entrepreneurs will often pay lip service to these financial goals – be it in terms of net present value created or payback time – and they will provide whatever numbers management expects to see, knowing full well that such kinds of number games are irrelevant at the early stage of risky innovation projects. But circumventing the existing benchmarks can only work sometimes. After a failure or two the real true-blue entrepreneurs will soon find it more attractive to find a company that really values innovation.

Risk averse innovation cultures exist in many companies, particularly those with a strong focus on operational excellence and performance predictability. Even though management may encourage risk taking in their speeches, managers are quick to sense what the top team really means. Most companies carry a whole cemetery of failed projects and ventures, and managers are quick to find out what fate befell their promoters. This often kills early desires to take risks.

There are two powerful antidotes to the fear, which can convince managers that top management values and actively seeks risk taking.

First, management can set the example at the top by asking senior leaders to personally coach high-risk/high-reward projects. Often, this means making themselves regularly available to the project team – for example, after normal hours – for informal reviews and problem solving.

When this is done – and this is the first benefit – the whole organization quickly learns that (1) risky projects are perceived as acceptable and management is ready to back them, even if they end up failing, and (2) a high mortality rate for such projects is considered normal and nobody should be penalized for trying and failing.

A second benefit of this approach is that within the top management team innovation discussions become more concrete as policy decisions can be tested on real projects.

If every member of the top team personally sponsors a project, the third benefit is that the decision to pull the plug on a given project is taken collectively without undue pressure on the sponsoring leader who does not risk losing face.

The second antidote is for management to adopt the philosophy of venture capitalists (VCs) regarding investments, resource allocation, coaching and return expectations, as recommended by Gary Hamel in his famous article on Silicon Valley (see box).13 Hamel advocates creating an internal market for ideas, talent, and capital, and making projects compete for resources. Knowing that only a small proportion of projects will be successful, VCs look for the upside and not the downside of projects, and they will do their utmost to support the projects that have the highest chances of winning. In cases of failure, they move fast to start new ones.

Killer # 3: Insufficient Customer and User Orientation

Relying on superficial market knowledge or outdated knowledge or, worse, believing that the company “knows better” than customers – the typical arrogance of established market leaders – are also innovation dampers. Note that the reverse – taking customers' expressed wishes at face value – can also be misleading, since customers are often unable to talk about their latent or future needs – the needs that, if well addressed, can build competition-crushing, or disruptive, innovation. Who would ever have thought that we “needed” and would pay for a telephone that holds an entire address book and calendar! Insufficient customer and user orientation can also lead companies to neglect to define and target specific customer groups. Companies that launch a new product concept without clearly identifying a specific target group beforehand – at least initially – and without understanding how that customer group will benefit from it are likely to waste resources. The approach of “raising-the-flag-and-seeing-if-anyone-salutes” is a costly way to bring innovations to market. It is only valid if the company is very agile, learns fast from the initial launch, and quickly reorients and relaunches to target a specific customer group.

Once again, there are at least two types of antidotes to this lack of customer intimacy.

First, management can overcome this deficiency, not by multiplying ad nauseam the amount of traditional market research done by the company, but by making staff temporarily share the life of various customers to understand their total experience.14 The point is not so much to search for what customers say they want – they may often trail behind the times – but to become immersed in their environment in order to understand what they do, how they feel, what frustrates and delights them, thus being able to anticipate what they might need and want in the future. Customer-oriented companies encourage a significant proportion of their staff – and not just marketing specialists – to conduct such customer immersions at regular intervals.

Second, management can also encourage staff to engage selected customers to join them in their idea searches and innovation projects. Some industries, like aerospace, do this as a matter of routine. No new aircraft could be developed and commercialized without the active involvement of lead customers, for example airlines, from the very early stages onward. But this habit, which some companies refer to as organizing “customer clinics,” is not always encouraged, for fear of losing confidentiality on new products or for lack of trust in the wisdom of customers, or often because selecting customers for such tasks is not easy. Whatever their actual contribution to the company's projects, this habit of involving customers in idea searches and projects creates strong customer intimacy.

Killer # 4: Uncertainty on Innovation Priorities

Not knowing what management expects from innovation is often perceived by many in the organization as a major innovation obstacle, particularly if it is combined with a risk averse culture. It leads to ad hoc idea generation (where should we search for ideas?); difficult concept evaluations (against what objectives should we evaluate our ideas?); fuzzy screening and selection (on what basis should we favor one project over another?); and poor project justifications.

As we recommended earlier, this uncertainty can be overcome by clarifying the company's innovation strategy, which means defining and broadcasting why, where, how, and with whom to innovate.

Management can also beef up the project briefing process by requesting that projects be linked explicitly to the company's announced innovation objectives and strategy.

Killer # 5: Lack of Management Patience Regarding Results

Leaders who press their teams unduly for faster results – not so much for shorter lead times, which is understandable, but for quick returns on investment – can be strong innovation inhibitors. Indeed, if short payback is introduced as an important criterion for the selection of innovative project ideas, then staff will, of necessity, screen out all ideas with a long-term high-risk/high-impact profile, to focus exclusively on predictable, incremental innovations. The same leaders may also be tempted to pull the plug too soon on very attractive projects with a long incubation phase and payback outlook.

The top management team can fight this temptation in two ways.

First, it can earmark specific resources for long-term projects, alongside the company's “normal” R&D budget, and personally become involved in selecting these high-impact projects.

Second, it can ensure that hurdle rates of return, whatever the type, are not introduced as criteria in the initial screening process for innovative project ideas. Financial payback considerations should appear only at a much later stage, when big capital investments are being considered. Instead of payback criteria, management should emphasize the project's potential to create value, i.e. the superiority of the future product or service provided to the company's customers, as perceived by the market, and ideally the price these customers will be ready to pay for the product or service, which will make the project attractive. This potential to create a quantum leap in value should obviously be validated through customer contacts and early feedback. If positive, this should convince management to be patient!

Killer # 6: Functional and Regional Silos

Large, complex organizations are often characterized by the coexistence of communities of specialists, each with its own identity, values, and professional norms. These communities exist at headquarters at the functional level. They are also present in decentralized operations, manufacturing plants, or regional and national commercial organizations. Unless strongly unified under the same corporate culture banner, these various groups tend to develop an “us vs. them” mentality, which can be detrimental to a cross-functional and cross-disciplinary process like innovation.

There are multiple dangers:

- Organizational isolationism, which slows the process down by making functional project handovers complex since each function wants to keep full control over its own field of expertise.

- The inability to build on one another's ideas because of the lack of opportunities to work together on the project from the start. This often happens when regional organizations feel left out of the initial project specifications, which are decided upon at headquarters level “for the world.”

- Domineering attitudes of some departments, which claim to have the final say in all project matters. This can be the case with marketing dominating R&D in fast-moving consumer goods, or with engineering overpowering everyone in technology-intensive companies.

- Fights over ideas and budgets may also prevent people from cooperating across organizational boundaries. This can happen when a project team requires additional resources from functional departments.

The best and most classic antidote to this danger is the systematic adoption of A to Z cross-functional and/or cross-regional innovation project teams – from idea and concept to market launch – combined with a high degree of empowerment of the project leaders in relation to the functional organization. By working together on the same intense projects, people start building bridges across functions and geographical areas, and they are more likely to adopt a “we” attitude as opposed to an “us vs. them” mindset. In addition, because they share the same performance measures – it is the team that succeeds or fails, not individuals or functions – this helps create a strong sense of solidarity within the team.

Another way to fight silos and develop a “one company spirit” is to multiply opportunities for joint innovation training programs. When people from different functions and regions spend time together discussing current management issues, visions and perceptions do change and collaboration becomes easier.

Killer # 7: Rigid and Over-regimented Environment

Last but not least among the most widespread innovation killers is an overregulated environment. This situation exists in many large and traditional companies. Company policy, management rules, and standard operating procedures are definitely necessary to run operations but, by limiting the freedom of would-be entrepreneurs and slowing down teams with unnecessary paperwork and controls, they can discourage people and ultimately stifle innovation.

Management can overcome this risk in two steps.

First, it can make an explicit effort to review all the management rules that were designed primarily for conducting normal operations and generally controlling non-project expenses, and free the project teams from most of these rules. Among the rules to be eliminated are all those that (1) impose standard work processes; (2) limit or organize horizontal and vertical communications; (3) restrict the project team's free access to customers, suppliers, and partners; and (4) require considerable justifications for an authorization to travel or to spend small amounts of money, for example for information or tools.

But because a certain number of rules are necessary, management should ask the project team to define the process they intend to follow and the specific rules that they are willing to accept and apply in their work. Management could then check on how well team members abide by the process and rules that they themselves have chosen.

Monitoring and Evaluating Results

Finally, management needs to set up and monitor a range of performance indicators to track progress and identify new improvement targets as some of the initial goals are reached. At the very least, indicators ought to cover both input factors – how many resources the company pumps into innovation – and output measures – how much the company is getting out of its innovation investments. But advanced innovators will typically go beyond these two broad categories and introduce a pyramid of metrics with four types of carefully selected indicators:

- Lagging indicators measure process results, typically on the basis of market or financial performance. The percentage of sales that comes from products introduced in the past few years, depending on the industry life cycle, is a typical lagging indicator. So is “time to profit,” which measures the time it takes for cumulated profits to pass cumulated investments.

- Leading indicators measure process input quality and/or quantity or factors conditioning innovation. The number of patents issued and granted is an example of a leading indicator – and not an overall innovation performance indicator as some companies believe! Another example is the percentage of R&D spent on long-term, high-risk/high-impact projects.

- In-process indicators measure process quality in terms of deliverables and time or cost compliance. Classic indicators in this category include the number of non-value-adding changes in projects past a certain point, or the percentage of project review gates passed according to schedule.

- Learning indicators which measure the improvement rate on critical performance targets for the business. Examples include the product stabilization period (from launch until quality and performance meet expectations), or more generally the “half-life” of a specific improvement (the time it takes to improve a given performance by 50%).

The range of innovation performance indicators companies use varies from very few (typically reflecting sales and profit growth from new products) to too many! It is indeed difficult to find the right balance and mix.

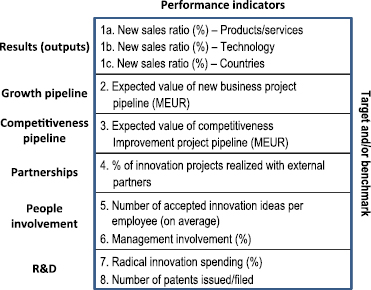

Solvay, the global chemicals and polymer group, provides a good illustration of a balanced innovation scorecard. It is impressive because it focuses on a manageable number of ratios, eight in total, but in the main categories of performance which reflect the company's innovation priorities: results, the growth pipeline, partnerships, ideas generated, people involvement, and R&D (refer to Figure 3.3 shown in Solvay's 2012 annual report).

Figure 3.3: Solvay's Innovation Scorecard

Reproduced with permission of Solvay SA. All rights reserved.

The merit of Solvay's approach is that it has set specific corporate targets in three key areas that have been selected as main innovation challenges within the Group, as indicated on its website:

- Growth objective: 30% of Group income should come from new products or technologies.

- Partnerships objective: 50% of projects should be developed in partnership with external partners (customers, universities, public authorities, start-ups, etc.) in the framework of structured agreements.

- People objective: 100% of executives should define their personal innovation objective every year and have the occasion to evaluate it at least once with their managers. All employees should produce at least one innovative idea every year.15

In Conclusion: A Call for Action

The six innovation governance areas described in this chapter highlight a number of responsibilities that will typically not be carried out by the second or third line of a company's hierarchy. These employees can be expected to manage processes and projects within a set of overall guidelines, not to come up with an overall framework for innovation.

The six domains essential for organizing and mobilizing for innovation are:

- setting an overall frame for innovation;

- defining value;

- choosing an innovation governance model;

- establishing innovation priorities and allocating resources;

- overcoming obstacles and building an innovation culture; and

- monitoring and evaluating results.

They condition the way innovation is carried out and sustained by the organization. They therefore belong to the prime innovation governance duties of the top management team. It is vital for the C-suite to address them collectively, broadcast their outcomes and include them as a regular topic on the top management agenda.

We conclude with one caveat: the mission of innovation leaders is to steer and support innovators. Governing innovation means making sure that innovators have as smooth a path as possible, that their commitment and hard work pay off as much and as often as possible. We have seen many cases where people work hard on projects that should have been successful, only to see their work side-lined, defeated, or disrupted by the kinds of “killers” outlined in this chapter. This problem is often caused by the leaders who should be in charge of smoothing the path to success. They fail to follow the kinds of practices we have discussed above. Problems lie in the way the system is designed and the way the work is organized. Now that companies have discovered increasingly better ways of designing and organizing the work of innovation, it is time for top management to take full responsibility for making sure that the design and organization are optimized so that the innovators have a chance to produce the value they are capable of delivering.

Notes

1 Lafley, A.G. and Charan, R. (introduction) (2008). P&G's Innovation Culture: How We Built a World-class Organic Growth Engine by Investing in People. Strategy+Business, August 26, http://www.strategy-business.com/article/08304?pg=all

2 Refer to Young, J.S. and Simon, W.L. (2005). iCon Steve Jobs, The Greatest Second Act in the History of Business. Wiley, p. 88.

3 For the full list of these values, refer to http://www.askstudent.com/google/list-of-google-core-values/

4 Hamel, G. (2010). Deconstructing Apple – Part 2. Wall Street Journal, March 8.

5 Refer to the framework proposed by Beebe Nelson and Valerie Kijewski. http://www.nkaudits.com/

6 Excerpt from a 2005 videotaped interview “Steering and Coaching an Innovation Project” with Nils Björkman and Bo Wirsén, members of the Group Leadership Team of Tetra Pak International by Prof. J.P. Deschamps, IMD, Lausanne, Switzerland.

7 Excerpt from a 2009 videotaped interview “DSM: Mobilizing the Organization to Grow through Innovation” with Rob van Leen, chief innovation officer at DSM, by Prof. J.P. Deschamps, IMD, Lausanne, Switzerland.

8 Chan Kim, W. and Mauborgne, R. (2005). Blue Ocean Strategy – How to Create Uncontested Market Space and Make Competition Irrelevant. Harvard Business School Press.

9 Chan Kim, W. and Mauborgne, R. (1997). Value Innovation: The Strategic Logic of High Growth. Harvard Business Review, January–February 1997.

10 Fine, C.H. (1998). Clockspeed: Winning Industry Control in the Age of Temporary Advantage. Perseus Books. Used with permission.

11 Deschamps, J.-P. (2008). Innovation Leaders: How Senior Executives Stimulate, Steer and Sustain Innovation. San Francisco: Wiley/Jossey-Bass, Chapter 6.

12 Amabile, T.M. and Khaire, M. (2008). Creativity and the Role of the Leader. Harvard Business Review, October.

13 Hamel, G. (1999). Bringing Silicon Valley Inside. Harvard Business Review, September/October.

14 Gouillart, F.J. and Sturdivant, F.D. (2009). Spend a Day in the Life of Your Customers. Harvard Business Review, March.

15 Innovation Scorecard, copyright Solvay 2013, source: http://www.solvay.com/EN/Innovation/innovationscorecard.aspx