CHAPTER

2

HOW TO SPOT BLINDSPOTS IN YOURSELF AND OTHERS

One sign of self-awareness is realizing when you are getting in your own way. Consider the pharmaceutical firm that ran into problems with a regulatory agency. The R&D leader of the company thought the government was being unfair and even punitive in the restrictions it was placing on one of the firm's products (resulting in a more narrowly defined scope of use). The conflict, to him, had become personal. He was angry to the point of wanting to take the agency to court to fight its ruling—which would damage the longer-term relationship with an agency the firm needed to be successful. To his credit, the R&D leader came to understand that his emotional reaction to the situation was one-sided and he was no longer acting in a helpful manner to resolve the problem. He knew that he was too emotionally invested to be involved in the detailed negotiations. He delegated the task of negotiating with the regulatory agency to his general counsel and one of his team members. The company and the regulatory agency eventually reached a settlement that was satisfactory to both parties. The R&D leader then committed to fixing the problem so that his company would not find itself in a similar situation in the future with that agency. This is an example of a weakness that was not a blindspot because the leader identified his shortcomings and acted effectively to do what was in the best interests of his company. People often think of blindspots as weaknesses, but they are a special type of weakness—one that is unrecognized. That is, there is a difference between a weakness we recognize and a weakness we don't recognize. These unknown areas often pose the greatest risk because no corrective action is possible without awareness of the need to act.1 The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead made this point when he stated that what we need to fear is “not ignorance, but ignorance of ignorance.”2 A central theme of this book is that leaders get into trouble when they don't know what they don't know in the areas that matter.

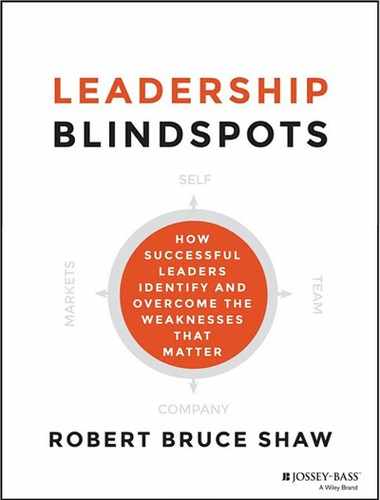

THE BLINDSPOT MATRIX

Four types of leadership awareness are outlined in the accompanying figure, what I call the blindspot matrix.

Blindspot Matrix

Known Strengths: You Know What You Know

Known strengths are areas in which a leader excels and has a proven track record (upper-right box of the matrix). Appropriately self-confident, the leader leverages his or her knowledge and skills to the benefit of his or her business and organization. I worked, for instance, with a business leader who rose through the sales and marketing functions of his company. In these roles, he learned how to engage others during sales meetings and conferences, as well as on sales calls to senior-level customers. As a result of his personal charisma and years spent refining his communication skills, he became the best public speaker in his company. He knows this is a unique strength and leverages it fully in communicating his firm's strategies and initiatives to groups inside and outside of his firm.

Known Weakness: You Know What You Don't Know

Known weaknesses are areas in which the leader lacks capability and has a weak or uneven track record (upper-left box of the matrix). Weaknesses are not blindspots if a leader is fully aware of them and their potential consequences. He or she manages these vulnerabilities, in some situations, by developing necessary skills in the area of weakness. In other situations, the leader finds and empowers others who possess the knowledge or skill that the leader is lacking. For example, I work with a leader who is one of the best at empowering her people. She provides clear direction and then gives her team members the autonomy they need to effectively manage their own areas of responsibility. She views herself as a resource that team members can use as a sounding board. But she doesn't solve their problems for them or make their decisions. Her weakness is that she can sometimes give underperformers too much autonomy. In one case, she waited too long to remove an underperforming member of her team who lacked the capabilities needed to deliver what the business needed. However, she was not interested in changing her management approach because, in her words, “Failing to trust people is not how I am wired.” She is honest in knowing that she doesn't like micromanaging or even providing hands-on performance coaching to those who are struggling. She also knows this is an area in which she is vulnerable. To compensate, she brought into her team a tough second in command who holds the firm's line leaders accountable and does so in a skillful and culturally appropriate manner. The leader describes the benefit of this arrangement as, “I trust. He verifies.”

A final approach to addressing known weaknesses is to do nothing. Consider the leader who gets feedback that he is not very effective as a public speaker. The leader agrees with the feedback but believes that other members of his team can represent the firm in public forums. His interest and skill is ensuring that his firm executes at a high level and delivers on its financial commitments. As a result, he does not invest time to improve his speaking skills. In this case, he acts with full awareness of a potential weakness and the consequences of not acting to address it.

Unknown Strengths: You Don't Know What You Know

Unknown strengths are counterintuitive because it is hard to believe that people don't know what they know. There can be, however, areas in which a leader excels but is not fully aware of his or her strengths (bottom-right box of the matrix). These are typically strengths that a leader may take for granted or doesn't view as exceptional. As a result, these strengths are not fully leveraged because the leader fails to recognize their potential impact. For instance, I worked with a CFO who is skilled at developing his people and building a high-performing team. He does this naturally and doesn't think of it as a differentiating capability. It is simply something he does because he feels it needs to be done. Over time, he came to appreciate that few leaders in his firm could match his skills in this area. He is now taking more time to provide coaching and mentoring to lower-level leaders in his own group and in others’ groups. He is also making it a point to let potential hires know that he is invested in developing his team members and, in doing so, increases the likelihood of attracting and retaining top talent to his function.

Robert Kaplan and Robert Kaiser, in their book Fear Your Strengths, make another argument for the need to be aware of your strengths. They make the case that weaknesses are often overused strengths.3 The idea that strengths can become liabilities is initially counterintuitive.4 How can a leader, for instance, be too strategic? Or have too much integrity? Yet blindspots can arise and become a liability when a strength, particularly a towering strength, blocks awareness of other factors important to a leader's success. A leader who is most comfortable in the strategic arena can ignore necessary operational details or the need to surround himself with those who have the operational skills he lacks. An individual with absolute integrity runs the risk of believing that everyone on her team is like herself—and is blindsided when a member of her group acts in a highly unethical manner. Or a leader with superior influencing skills may push too hard to win the day and fail to appreciate when a more collaborative approach is needed. This doesn't mean that a leader should stop using his or her strengths or that strengths always have a downside. An effective leader is self-aware to the point of knowing when his or her strengths pose a risk and, as a result, uses those strengths in a more skillful manner.

Blindspots: You Don't Know What You Don't Know

Blindspots are the areas of unrecognized weakness, described in Chapter One, that place a leader at risk because corrective action can't be taken without an awareness of a need to do so (bottom-left box of the matrix). An example is the leader who is constantly highlighting negatives in his team's behavior and performance—to the point where team members believe that they will never be able to meet his standards and are demoralized. He is unaware of the negative impact he is having on his team and, in fact, views himself as doing his job in holding people to a high standard of performance.

Blindspots can arise when a strength, particularly a towering strength, blocks awareness of other factors important to a leader's success.

A point to note in this matrix is that it doesn't differentiate between what others know about you and what you know about yourself. This approach is different from what is found in a well-known model called the Johari Window, which contrasts how others see us with how we see ourselves.5 My focus is a leader's level of awareness of his or her strengths and weaknesses—which may or may not be related to what others see in the leader. In some cases, the perceptions of others, while important to understand, are not accurate or even helpful. Perception may be important but it is not reality. Each leader needs to determine which perceptions merit attention and which need to be ignored.

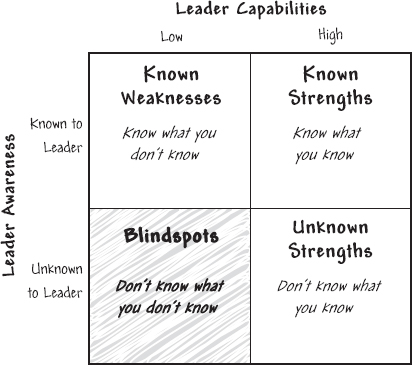

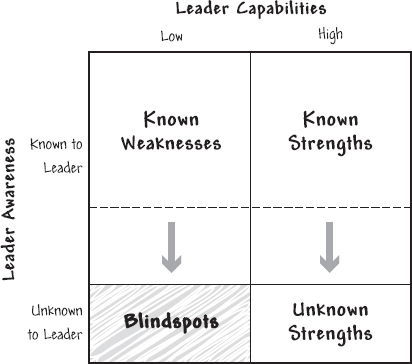

The blindspot matrix at the beginning of the chapter is portrayed as four equally sized quadrants. In reality, the size of each quadrant varies, with one or more of the four areas often being larger than the others for a particular leader. Some leaders, for example, are well aware of their weaknesses (being self-critical) but less aware of their strengths. Others are the opposite, with full awareness of their strengths but possessing only a limited awareness of their weaknesses. The matrix is useful in illustrating potential areas for improvement. The first improvement occurs when a leader becomes more aware of his or her blindspots as well as unknown strengths (as represented in the blindspot matrix titled “Increasing Leader Awareness”). The second improvement occurs when a leader develops new capabilities in targeted areas and replaces weaknesses with strengths (as represented in the “Increasing Leader Capacity” blindspot matrix). The goal is to increase awareness of both weaknesses and strengths and then more fully leverage one's strengths while reducing areas of weakness.

Blindspot Matrix: Increasing Leader Awareness

Blindspot Matrix: Increasing Leader Capacity

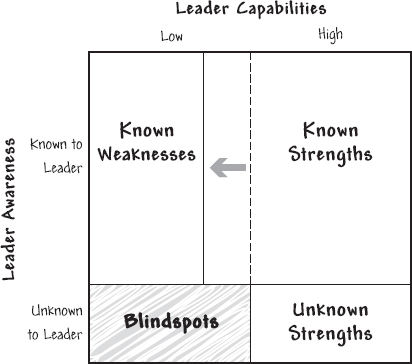

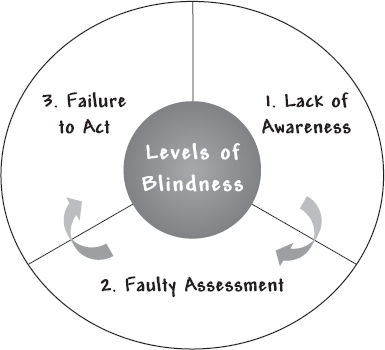

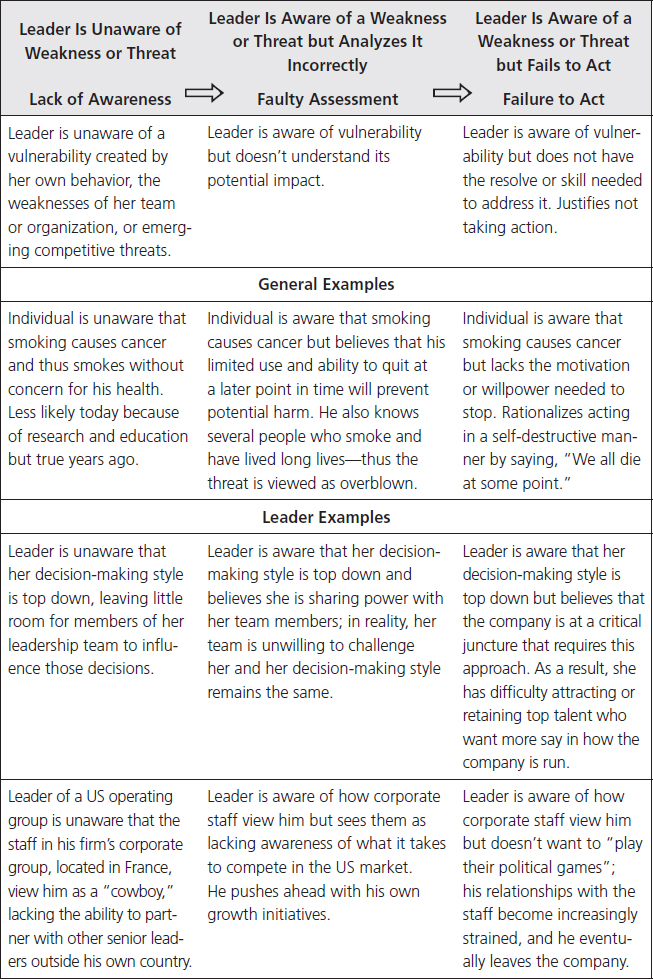

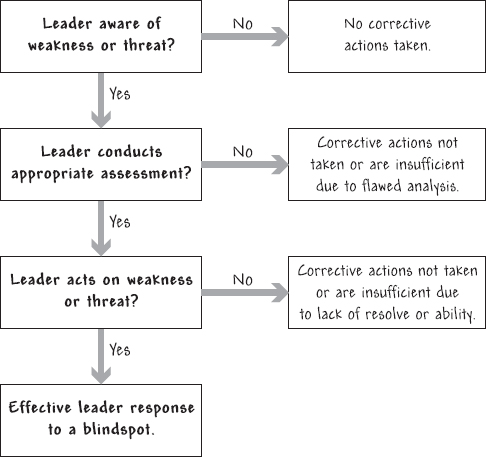

DEGREES OF BLINDNESS

One of the complexities of blindspots is that they can include gray areas where leaders both know and don't know that which threatens them. While it is illogical to believe that someone can both know and not know something at the same time—that they are both the deceiver and the deceived—this is what occurs. The following discussion examines different types of blindspots (see the figure “Blindspots: You Don't Know What You Don't Know”) and the implications of each.

Blindspots: You Don't Know What You Don't Know

Lack of Awareness

The most extreme form of a blindspot is a complete lack of awareness regarding a weakness or threat. These are the cases where the leader is said to be blindsided—surprised by events that he or she doesn't see coming. An example of this is found in the recent leadership turmoil during the merger of two electrical utility companies. Duke Energy and Progress Energy agreed to form the largest electrical utility in the country, with over seven million customers. The boards of both firms approved the $26 billion deal, with an agreement that the CEO of Progress Energy, Bill Johnson, would become the CEO of the newly combined company. The CEO of Duke Energy, Jim Rogers, would become executive chairman. The day the deal closed, the new firm's board met for the first time and made a change in CEOs. This swift turn of events was described as follows: “At 4:30 PM the Duke board elected Johnson CEO. Then, after Johnson left to celebrate, the board took another vote and ousted him. He served as chief executive for two hours, give or take a few minutes. The Duke board awarded him an exit package of $45 million in deferred compensation, severance, and other benefits. To finish an eventful afternoon, the Duke board reinstalled Rogers in the top job.”6

The terms of the merger gave Duke a majority of members on the newly formed board. Once they fulfilled the merger agreement by making Johnson CEO, they were fully within their rights to fire him. Warned in advance of the plan, the entire group of legacy Duke directors endorsed the change. The Progress directors, in contrast, had no idea of the planned firing and were powerless to stop it. The announcement of the change included an explanation that the board had concluded that Johnson's management style was a poor fit with what the new company needed and thus removed him from his position.

The Progress directors on the board were shocked by the change and felt betrayed by Duke, indicating that they never would have approved the deal if they had known what was to occur post-merger. One of the Progress board members called it an “incredible act of bad faith” and “the most blatant example of corporate deceit that I have witnessed during a long career on Wall Street and as a director of ten publicly traded companies.”7 Bill Johnson was as surprised as the Progress board members. He had no idea of what was going on behind the scenes, which is curious given that he had operated in senior corporate roles for decades and was well versed in the complexities of corporate politics. He was, nonetheless, completely surprised by the turn of events.8

Faulty Assessment

People who are smart and self-assured are often very skillful at justifying their thinking and behavior—to the point of being in denial about their weaknesses and the threats they face.

The second level of blindness can be described as denial, which is the refusal to fully face unwelcome realities that pose a risk to a leader and his or her firm. In this case, a leader may be aware of a weakness or threat but doesn't analyze it in sufficient depth to understand its causes and potential impact. The vulnerability is seen by the leader as “not being a big deal” or “not my problem.”9 A tragic example of denial is found in the 2003 space shuttle Columbia disaster. The Columbia was launched for a two-week mission with a crew of seven astronauts. On takeoff, a large piece of white foam came off the shuttle's external fuel tank, striking the left wing of the spacecraft and creating a shower of particles, known as a debris field. Although foam strikes had plagued the shuttle from the beginning of the program, no catastrophic damage had occurred. On this mission, however, one piece of foam that struck the shuttle was approximately a hundred times larger than normal (about the size of a briefcase). The engineers responsible for monitoring the launch wanted to collect more data to determine if they had a major safety issue with Columbia. While a shuttle is in orbit, only a robot camera or a spacewalk can conclusively determine the extent of the damage to the skin of the spacecraft, but Columbia had no camera, and sending an astronaut on an unscheduled spacewalk was not an operation to be undertaken lightly. As a first step, the engineers monitoring the launch requested a visual inspection of the shuttle via the US Department of Defense's high-resolution, ground-based cameras, which had the ability to take images of the Columbia in orbit.10

Linda Ham, the mission management team chair responsible for Columbia's mission, was a fast-rising leader in the space agency. She viewed foam debris on the shuttle as a potential problem but did not think it constituted a safety-of-flight issue. Without compelling evidence that would raise the engineers’ imagery request to “mandatory,” there was no reason in her mind to ask for outside assistance. Besides, as Ham stated in an internal memo that surfaced later, “It's not really a factor during the flight because there isn't much we can do about it,” as the shuttle lacked any onboard means to repair its external thermal protection system.11 Linda Ham wrapped up the assessment of the foam strike issue by concluding, after input from several of her more senior technical advisors, that there was no safety issue. She then asked her team, in a critical meeting, “All right, any questions on that?” No one raised questions or concerns—including the engineers who knew a risk existed based on the launch film. They believed NASA's stated value of “safety first” was being severely compromised but did not want to challenge the higher-level authorities in the agency. No further assessment was conducted, and the shuttle began its descent as scheduled. On reentry, the gaping hole punched by the foam into the edge of shuttle's wing allowed superheated gasses to enter the spacecraft, breaking it apart as it descended over the southwestern United States.

To be fair, blindspots are not always a case of a leader ignoring the obvious. Events are almost always less clear as they unfold than they appear in hindsight. This is clearly evident in the case of the Columbia shuttle disaster. Linda Ham was facing literally hundreds of issues that needed to be resolved, and the foam strike was but one of many of her concerns. In addition, some of her most respected senior staff were telling her that she didn't need to worry—that there was no safety issue. In retrospect, she can be faulted for failing to follow up with those who were concerned with the damage caused by the strike and for not obtaining additional data that would have resolved the debate that was occurring within her organization. This is not to absolve her of accountability but, instead, to recognize the ambiguity and confusion that often permeates real-time decision making.

In particular, we are adept at crafting an explanation, and then believing in that explanation, when existing knowledge is insufficient. Nassim Taleb describes this as a narrative fallacy, where people take past events and available data to construct a storyline that they use to explain complex phenomena.12 This works in many cases, as the past is often the best predictor of the future, but it can also result in mistakes. This is what happened at NASA when its leadership took the agency's past experiences with foam strikes and determined that there was no in-flight issue with the Columbia shuttle. Psychologist Daniel Kahneman observes that “filling in the gaps” is a common occurrence in a wide range of decision-making situations:

You cannot help dealing with the limited information you have as if it were all there is to know. You build the best possible story from the information available to you, and if it is a good story, you believe it. Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little, when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.13

People who are smart and self-assured are often very skillful at justifying their thinking and behavior—to the point of being in denial about their weaknesses and the threats they face. Their intelligence can work against them when they convince themselves, and often others, that they are right even when they are wrong. Take the case of a charismatic and brilliant corporate leader who, early in his career, was trained as an engineer. His style was to confront others and their ideas with the zeal of one who knew his analytical capabilities were superior to others. He also immersed himself in a wide variety of minute details because of his training as an engineer. These traits served him well as he moved up into general manager roles and executed programs at a high level. But these same traits were debilitating once he became CEO. He was told that he needed to change his management style—delegate more and balance his confrontation style with an ability to inspire others. He intellectually understood the feedback but didn't alter his behavior. Under stress, he would revert to the approach that was most comfortable for him—a style that fit his personality and had propelled him throughout his career. As a result, a majority of his team, a group of talented and experienced executives, felt the he was overmanaging them and constantly attacking their ideas. Rather than change his approach, the leader told himself that he was a necessary force for change in a company stuck in the past. He wasn't the problem—they were the problem. He was right in that change was needed. His blindspot was not seeing the impact of his behavior and the consequences if he didn't change. This oversight eventually cost him his job. The firm's board concluded that he lacked the leadership skills needed to run a large company.

Failure to Act

The third level of blindness involves a leader's willingness or ability to act on a known weakness or threat. There are cases when a leader knows that trouble lies ahead but fails to take action due to a range of factors including a lack of skill. I refer to this as a type of blindness because the leader fails to fully appreciate the risk he or she is facing and the consequences of not taking action. Research indicates that people, in general, favor the status quo when making a decision that involves risk.14 More specifically, they view their current situation as a reference point against which other options are assessed. Actions that move an individual away from that reference point, the status quo, are seen as a loss. As a result, many in this situation follow the unspoken rules of “When in doubt, do nothing” or “When in doubt, wait and see how things unfold.”

Blindness regarding the need to act and, more specifically, the consequences of not acting is evident in some leaders. Take the case of a leader who lacks executional skills and instead prides himself on his strategic and motivational capabilities. He is also less interested in the details of how things get done and prefers to delegate these matters to others. He knows this is a potential weakness, given some missteps in his past when he didn't pay attention to how his strategies were being executed and he suffered the consequences of missed milestones and cost overruns on several of his key initiatives. Still, he has risen within his company based on his strategic insights, and he reverts to his comfort zone in staying above the messy details in managing projects. His leadership approach works well when he has talented people reporting to him who compensate for his gaps in this area. But it creates problems for him and his company when he has people reporting to him who have executional shortcomings or are unwilling to confront him when problems arise. He knows he is vulnerable in this area and yet fails to modify his leadership approach, or create management review processes, to ensure that his initiatives are executed at a high level. In this case, his blindness is failing to see the consequences of not acting on a known weakness.

At a company level, the Xerox Corporation is a well-known example of a large and successful firm that failed to act. Xerox's R&D group, PARC, was at the forefront of many of the breakthroughs that were central to the early growth of the computer industry. These breakthroughs included the first development of pull-down menus, the mouse as a navigation device, computer-generated graphics, text-editing programs, laser printers, and the networking of computers for file sharing. The problem for Xerox was that its research group was estranged from the firm's headquarters and commercial group. The leaders in each group, one on the West Coast and the other on the East Coast, criticized the other group and blamed it for the failure to bring new products to market. The research leaders at PARC felt that their counterparts in sales and marketing had no real interest in the innovative products that were being developed in the firm's labs and, instead, were focused on short-term financial results in the core business. The sales and marketing leaders felt their research counterparts lacked business sense and had little discipline in their development processes. Senior corporate leadership, responsible to shareholders and for providing oversight to both groups, was aware of the problem but didn't act to deal with it. As a result of the firm's dysfunctional corporate culture, competitors such as Apple and HP seized the innovations developed by Xerox and created multibillion-dollar businesses that Xerox should have dominated. Xerox also faced competition in its core business. Canon was producing high-quality and low-cost copiers that took market share away from Xerox's core business. As that core business declined, a business that Xerox invented, there was no second act to drive the next phase of growth. An author who chronicled this period in Xerox's history called his book Fumbling the Future.15

Contrast the plight of Xerox with what has occurred at IBM over the past decade. As part of its strategic planning process, IBM's strategy office develops a ten-year outlook of its industry. The senior leadership of the firm then engages in heated debate about the trends suggested in the outlook. One of these trends was the shift in the technology industry from an emphasis on products to services, as clients wanted integrated solutions that met their specific needs (rather than stand-alone hardware that didn't address their unique business challenges). Through rigorous analysis and equally rigorous discussion, the senior leaders of the firm agreed that the trend was real and would significantly affect their business. The next step, however, was even more striking. IBM's leaders decided to take action on what they believed would occur in the marketplace. This resulted in selling the firm's PC business to Lenovo and purchasing the consulting business of PricewaterhouseCoopers to enhance IBM's service capabilities. The CEO at the time, Sam Palmisano, noted that what turned out to be a successful shift into services was due, in part, to IBM's long history of managing such transformations. In the past, some were handled well and other less so—resulting in an institutional memory of lessons learned. In particular, Palmisano noted that IBM had mismanaged the shift, decades earlier, from mainframe computers to personal computers because it did not want to undercut its dominant business model and associated revenue stream. Palmisano vowed that it would not repeat that mistake in making the shift to services:

Degrees of Blindness

I don't think it was anything in the technology that we were seeing that others weren't seeing. We just decided to act upon it. Others chose not to act upon it. … [A] lot of companies have a hard time seeing what I'll call Act Two because they get so wedded to the product, so wedded to the financial rewards of their business model if they've been successful, and they just don't see [the opportunity]. Or, if they see, they have a conservative view upon acting.16

The accompanying table, “Degrees of Blindness,” summarizes situations in which a leader lacks awareness of a weakness or threat, conducts a faulty assessment of its causes and impact, or fails to act on it.

RESPONSES TO BLINDSPOTS

Not all blindspots are destructive, and not all require action on the part of a leader. The question then becomes, Which weaknesses and threats, once surfaced and recognized, are important? An approach used by Bill Gore can help leaders determine what requires their attention. Gore was the founder of a firm best known for the development of Gore-Tex, a material used in water-resistant clothing. Gore believed in empowering his firm's ten thousand employees, whom he called associates. He wanted them to take responsibility for making decisions that would benefit the firm. He was equally clear that some decisions are potentially more damaging than others. He used the metaphor of a naval battle to convey when it is appropriate to act unilaterally and when it is necessary to gain the input of others. Shots fired by an enemy that strike a ship “above the waterline” will usually not sink the ship. However, shots that strike “below the waterline” will sink a ship, as water rushes in and rapidly fills the hull. Gore created a norm in his company that people needed to consult with others before taking a decision that might have effects below the waterline—that is, with the potential to cause serious damage to their company.17

Taking Gore's principle and applying it to blindspots, leaders need to question the relative importance of a weakness or threat once they become aware of it. While this seems obvious, I find the ability to prioritize weaknesses and threats varies widely among leaders. For example, some executives are given 360-degree assessment feedback on their leadership strengths and, of course, areas for improvement. After reading the report, some fail to see a key weakness that is clearly surfaced in the feedback—instead, they focus on areas that they find less troubling or less difficult to change. The question that a leader should ask about each weakness or threat is, “Will this weakness or threat, if not addressed, cause serious harm to me or my organization?” Or, stated differently, “If my thinking about the impact of this weakness or threat is incorrect, can I live with the potential consequences?”18 A second lesson from Gore's approach is the need to bring blindspots, once surfaced and identified as important, to the attention of others and ask for their advice on the appropriate course of action. In Gore's language, weaknesses or threats that are below the waterline need to be vetted with a broader group for additional feedback and advice. This increases the likelihood that the risk will be properly understood and appropriate action taken.

IDENTIFYING YOUR OWN BLINDSPOTS

There are several approaches that will help identify your own blindspots:

- Review your mistakes for reoccurring weaknesses.

- Solicit feedback from those with insight about you.

- Complete the Leadership Blindspot Survey.

Review Your Mistakes

While writing this book, I took a five-day backpacking trip in the Sierra Nevada mountains. Hiking for eight hours a day, I had ample opportunity to consider a range of topics, including my own blindspots (as much as I wished otherwise). In particular, I focused on the mistakes I have made over my career. I took the approach that mistakes are the royal road to understanding blindspots, particularly when repeated over time and in different situations. Mistakes often point to areas in which we lack self-awareness of a weakness or threat, including patterns in our thinking and behavior that get us into trouble. My “walking assessment” focused on a few questions:

- What are the most significant mistakes I have made over my career?

- What were the causes of each mistake?

- Are there patterns or common elements across these mistakes?

- Do the patterns suggest reoccurring blindspots on my part?

- What actions are needed on my part to prevent these mistakes from occurring again in the future?

Answering these questions, I identified several painful mistakes and an associated set of blindspots. For instance, I work closely with clients who are senior leaders in large corporations, providing advice on organizational and leadership effectiveness. Several years ago I was working with a leader who had recently moved into a new role in a pharmaceutical company. We decided to conduct an assessment to obtain feedback on how others viewed his performance after his first year in his role. He had three operating groups reporting to him, and I partnered with the internal human resource staff in each of those groups to conduct the assessment. The HR staff interviewed the teams in each operating group, asking for feedback on the senior leader (both in positive areas and in areas for improvement). They gave me their interview summaries, and I prepared a summary report.

In analyzing the feedback, it was clear that one of the divisions was much more critical of the leader's performance than the other two divisions. In collecting the input for the assessment, HR staff told the participants that I would not name any individuals or provide information that would reveal individual identities. In the report, I also didn't differentiate among the divisions because the HR partner from the “negative division” told me that this would create problems for him and his team. Thus, no individuals were identified and no divisional data was provided in the feedback report. However, I wanted the senior leader to know where he had an issue and needed to devote his energy. I made a compromise with the HR leader and said that I would not identify any groups or individuals in the report but would suggest to the leader, when personally reviewing the feedback with him, that he had more of an issue in one of his divisions than in the other two (naming the division that was more negative). The senior leader took the feedback and then met with each of the division leaders and reviewed the findings. In a private session, he was direct with the leader whose group was the most negative and indicated that they needed to be more open and transparent in working together. The leader of that division left the meeting feeling that he had been singled out by the leader and his group had been “thrown under the bus” by me. He then went to great lengths to portray me to his peers as untrustworthy and someone with whom others should not work.

Mistakes are the royal road to understanding blindspots, particularly when repeated over time and in different situations.

In reflecting on this experience, I realized that I had focused on what my client needed to improve his performance—but I had not fully considered the implications for the division that was highlighted in the feedback as being more negative. The leader of that division was worried that the feedback would anger his boss, with potential career implications. I was right in wanting to give my client the information he needed to act but ineffective in not seeing the broader picture, including the political reality of how his company operated. While this was an extreme case, I can recall several other consulting situations over the years where I didn't fully take into account the needs of some individuals or groups lower in the organization and, as a result, created problems for myself. The “aha” moment for me occurred when I realized that in several instances this issue hadn't even registered with me until it was too late. I was “wired” to focus almost exclusively on my client and needed to do a better job of focusing as well on those at the next level of management.

Solicit Feedback from Those with Insight About You

A second approach is to ask those who know you to give you feedback on your blindspots. Ideally, a leader will want to invite this type of feedback from others, but it can occur spontaneously. Meg Whitman, CEO of Hewlett-Packard, provided such feedback to her boss early in her career while working at Bain Capital. Whitman approached her boss and asked if he wanted feedback about his leadership impact. He agreed, and she told him that he was a steamroller forcing his views on others, and that the result of his style was a lack of shared ownership for the decisions being made. He was surprised by the feedback but saw its merit and changed his behavior. He commented, years later, “There was a real courage to her … Even though her feedback was negative and unsolicited, it left me liking Meg more.”19 Feedback of this type can be surfaced by a leader in a more formal manner in conversations with those whom you trust to give you useful and honest feedback. You want to explore their perceptions and ask for specific examples of when you acted without awareness of your blindspots. The following questions can help structure the discussion (which you will want to give them in advance of your discussion):

Questions for Feedback on Your Leadership Blindspots

- Do you see me as having any blindspots in how I operate?

- In particular, do you see me as lacking awareness in any of the following areas?

- Self: My own leadership behavior and impact

- Team: The strengths and weaknesses of my leadership team or particular leadership team members

- Company: The strengths and weakness of our company

- Markets: The changing nature of our markets (in terms of customers or competition) and the threats we face

- Do people in the organization have any misperceptions about me? If so, what are they? Why do you think they hold these views?

Avoid seeking to justify your behavior to the person providing you with feedback. Just listen to what he or she has to say and take notes on the key points. Thank the person for the input and tell him or her that you want to take a few days to think about the feedback and the actions needed.

You can also use these questions but ask a third party (such as an external consultant or human resource staff member) to collect input about you in these areas. You want to select people to provide feedback who know you well and will also be honest regarding your leadership impact. The third party collects the feedback through informal interviews and then provides you with a summary document, without identifying who said what. This can be done as a separate process or as part of a larger assessment including a 360-degree survey.

Complete the Leadership Blindspot Survey

A third way to gain insight into your own blindspots is to complete the survey included at the end of the book in Resource B (“Leadership Blindspot Survey”). It contains self-assessment questions in each of the four potential blindspot areas (self, team, company, and markets). The issue, of course, with such a survey is that it is difficult to see ourselves accurately, particularly when it comes to our own blindspots (which, by definition, are unrecognized). The survey is crafted to help you look at the behaviors that can indicate blindspots and, in so doing, avoid some of the bias that can influence self-perceptions. The survey is designed for corporate executives and managers with teams reporting to them. If you don't have a team reporting to you and you want to compile a total blindspot score, select “3” as your answer on any question that refers to a team or team members. In addition, you may find that the final set of questions, on market awareness, do not apply to your work if you are in a mid- or lower-level role; if so, you can use the survey but will want to exclude these questions. If you don't answer these questions, you will not have an overall score but can view your results for the other three areas (self, team, and company). You will want to tabulate your results on the scoring sheet that follows the survey (also in Resource B). Then, look for patterns in the survey results, particularly in regard to areas of vulnerability. In the following chapters, I offer suggestions on how to effectively surface and address blindspots by taking action in specific areas.