CHAPTER

5

SEE IT FOR YOURSELF

Customers, Colleagues, and Outsiders

One of my clients grumbled soon after being promoted, “I am booked back-to-back in meetings day after day. These are typically conversations that others want to have with me, often to promote what they believe I need to do. They are controlling my time versus what I assumed would happen once I moved into the corner office.” He is not alone in that many leaders feel less power than they felt would be the case on moving up in their companies, particularly in regard to managing their schedules. Internally, time is consumed in dealing with a range of important topics such as developing long-term strategies and solving operational issues. Externally, particularly for those in senior roles, there are obligations to industry groups, institutional shareholders, financial analysts, and the media. Executives can, as a result, work for months without leaving the confines of their headquarters building. Customers and frontline employees easily fade into the background. Leaders rising within a company encounter a number of forces that work to isolate them from their own organizations.

A second reason that leaders become isolated and find their power diffused is that they are largely dependent on the information and recommendations delivered by others. Organizational hierarchies work in a manner that encourages individuals and groups at each level to consolidate data, which they escalate to the next level, if needed, for review and decision making. Each strata of leadership adds value by responding to work done by others at lower levels. The downside, however, is that leaders are making decisions on information that is at best incomplete and at worst biased. That is, information moving up an organization's hierarchy is inevitably screened and, in some cases, distorted. This may not be done intentionally, but it is an ongoing risk. For that reason, some leaders believe it is essential to get out into their operations to see for themselves what is happening. The CEO of Caterpillar has a sign posted on the floor of his firm's executive offices that reads, “A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.”1

Leaders can assume they are aware of what is occurring around them when, in fact, they have partial, sometimes inaccurate, and often outdated views.

Leaders also find themselves out of touch simply as a result of the scale and complexity of their organizations. Jamie Dimon leads a firm that operates in more than sixty countries with 240,000 employees. JPMorgan Chase, with more than $2 trillion in assets, is involved in a range of activities including investment banking, financial services, commercial lending, transaction processing, and asset management. Being aware of emerging risks in a firm of this size, as Jamie Dimon painfully learned, is a daunting task. Moving up in an organization ultimately means that you stop experiencing your businesses directly—instead, you get most of your information secondhand and in packaged form. Leaders must trust much of what is presented to them, as it is impossible to have direct exposure to, or even a detailed understanding of, many areas of their companies. Dimon, after the London Whale trading losses, argued that he had every reason to trust his chief investment officer. He had worked with her for years and she had a stellar track record. He took what she told him at face value: namely, that everything was under control and that he didn't need to worry about the problem escalating. His board concluded that Dimon was at fault for not probing further and determining for himself the nature of the risk facing his bank. The sobering reality of this case is that Dimon is known as a hands-on leader who immerses himself in necessary details.

One way to view the dilemma facing leaders is to consider the difference between watching a movie and personally experiencing events portrayed in that movie. Leaders, particularly as they become more senior, are in effect forced to watch a movie created by others. It may be a well-made movie, but it is still a movie. Although many organizations strive to make the upward flow of information more robust through required analyses, leadership decisions come down in many cases to trusting those below you and the story they present. Some leaders make the mistake of believing that the movie is reality or, as is sometimes stated, believing that the map is the territory. When this occurs, leaders can assume they are fully aware of what is occurring around them when, in fact, they have partial, sometimes inaccurate, and often outdated views of the opportunities and threats facing them and their firms.

In an interview conducted when he was still CEO of Schlumberger, Andrew Gould argues that to be a leader is to be alone. Despite all the talk of teamwork, many of the toughest decisions are ultimately made by one individual. Gould believes that he must work hard to get the information he needs to make quality decisions, as various organizational factors limit or distort the flow of data to him. Toward that goal, he might call a country manager for details on how a market is performing and progress on a particular corporate initiative. He does not call the member of his leadership team who has formal authority over that country manager. He wants to hear directly from the individual responsible and not a more senior leader who might filter what Gould is told:

I have a rule in my team that I can contact any level of the organization, provided I don't contradict … what the intermediate levels of management have said…. My team hates it…. But actually, I think it's extremely important, the fact that I contact people much farther down in the organization. Everybody knows that, and it makes you more human to them. I think that it's very easy to become inhuman in a glass tower in an office, with all sorts of people protecting you from information.2

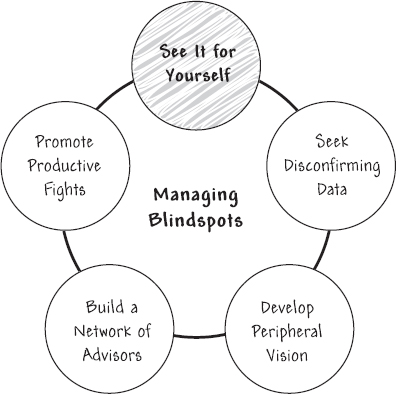

In order to see what is going on for themselves, leaders need to develop practices that increase their awareness in four areas:

- Customers and markets

- Frontline colleagues

- High-potential talent

- Outsiders

AWARENESS OF CUSTOMERS AND MARKETS

The retired former CEO of IBM, Sam Palmisano, told an interviewer that he learned from his predecessor in that role that the best way to analyze problems was by looking at them from the viewpoint of customers and markets. Palmisano believed that leaders sometimes overlook shifts in their marketplace because they are too internally focused.3 This is not to suggest that customers are always right in their views, particularly when it comes to innovative ideas and breakthrough products. In some cases, they are limited by what they know and have difficulty seeing beyond their current needs. Shortly before Apple's tablet went on sale, Steve Jobs revealed his new “magical” device to a group of journalists. One of them asked what consumer and market research Apple had conducted in developing what was being described as a revolutionary device. “None,” Jobs replied. “It isn't the consumers’ job to know what they want.”4 This is an extreme perspective but one to keep in mind as a leader seeks to learn from customers.

The leader who was a model of “outside in” thinking for Sam Palmisano was Lou Gerstner. IBM lost a record $5 billion in 1992, and Gerstner was made CEO with a mandate to turn the company around. Some faulted his appointment at the time because he did not have a technology background. Gerstner noted that as a leader in other firms he was a customer of IBM and other technology firms. To his credit, he initiated a process on coming into his role that allowed his team to better see the world from the vantage point of customers and move beyond what had become a culture of insular arrogance within the firm. He didn't come into his role with preordained answers but, instead, with a process to surface the information needed to improve the firm in the near term while also developing a vision of how it would position itself for long-term success.

One of his early actions as CEO was to reach out directly to customers and ask their views on IBM—what it did well and what needed to change. Gerstner also required that his top fifty executives do the same, visiting five customers each over a three-month period. His executives submitted a short report to Gerstner about their visits, summarizing what they learned. They also contacted leaders and groups at IBM who could help them deliver what each customer wanted. Through this process, Gerstner determined that IBM's customers wanted integrated solutions. This was in contrast to what some analysts and consultants believed was necessary—namely, breaking IBM up into separate and highly focused business groups to unlock shareholder value. Gerstner decided not to split up the company.

A more recent example of someone who exemplifies this type of thinking is Jeff Bezos of Amazon. He strives to ensure that key decisions in his company are driven from the perspective of the customer. “We innovate by starting with the customer and working backwards,” he says. “That becomes the touchstone for how we invent.”5 In fact, he wants his people thinking more about how to please customers than how to beat Amazon's competition. One well-known illustration of his “outside-in” mentality is Amazon's one-click ordering, which drastically reduces the information required of customers to place an order. Bezos wanted to make ordering online as easy as possible and, in so doing, bring customers back to Amazon for a wide variety of products. Amazon also provides customer reviews of the products it sells, including negative reviews. Some manufacturers argued that Bezos should not post reviews because negative reviews would result in fewer sales. He noted one critic who said, “ ‘You don't understand your business. You make money when you sell things. Why do you allow these negative customer reviews?’ And when I read that letter, I thought, we don't make money when we sell things. We make money when we help customers make purchase decisions.”6 Again, Bezos thought like a customer—which resulted in his firm's practice of providing honest feedback about its products.

Amazon's Bezos uses a range of approaches to focus his team on customers, including symbolic acts, hard performance metrics, and management requirements.

These innovations are the result of Bezos's tenacious, almost obsessive, approach to focusing on customers—in both symbolic and tangible ways. He will sometimes conduct company meetings with a seat open at the conference table. He informs those who don't already know that they should consider the seat as being occupied by an Amazon customer, who happens to be the most important person in the room. Bezos backs up these symbolic acts with formal processes such as a detailed set of customer metrics that his leadership team tracks religiously. The following are but a few of the metrics his firm uses to assess its performance:

- Perfect order percentage (POP). The percentage of orders that are perfectly accepted, processed, and fulfilled.

- Order defect rate (ODR). The percentage of orders that have received negative feedback, a guarantee claim, or a service credit card chargeback. The ODR allows the firm to measure overall performance with a single metric.

- Late ship rate. On-time shipment is a promise Amazon makes to customers who order through Amazon. Orders ship-confirmed three or more days beyond the expected ship date are considered late.

- Percentage of orders refunded. High refund rates are viewed as an indicator of item stock-outs.7

One interesting element of Bezos's leadership style is that he uses a range of approaches to focus his team on customers, including symbolic acts (such as the empty chair), hard performance metrics (such as the perfect order percentage), and management requirements (team members must periodically take customer calls in Amazon's service center, for example). His approach is more systematic and rigorous than what occurs in most large corporations, where actions intended to promote customer focus are often insufficient.

The tendency to become insular is evident in many headquarters groups. A. G. Lafley, CEO of Procter & Gamble, had been working in a regional P&G office before his promotion. On coming into the firm's Cincinnati headquarters, he observed that “many employees were glued to their computers and how much of each day people spent mired in internal meetings with other P&Gers. We were losing touch with consumers. We were not out in the competitive pressure cooker that is the marketplace. Too often we were working on initiatives consumers did not want and incurring costs that consumers should not have to pay for.”8

Lafley made a number of changes in how the company operated, seeking to change what he saw as an increasingly detached and isolated culture. He was worried that people in headquarters ran the risk of “talking to themselves” and not fully understanding how consumers thought about and used the products P&G was selling. Like Jeff Bezos at Amazon, he created a number of high-impact programs that forced people to be more aware of their customers’ point of view. This included making his own field visits, where he spent time in the homes of consumers who were using P&G products and in stores interacting with those buying products. He also supported corporate programs wherein executives and employees made prolonged visits to observe consumers using products in their homes—asking his team to act as anthropologists by studying the thinking and practices of the people they needed to understand at a deep level. P&G's executives also joined shoppers on trips to supermarkets or worked a shift behind a checkout counter to observe consumer behavior.

One of my clients brings customers into his leadership team meetings on a quarterly basis to discuss the customers’ business strategies and to listen to feedback on the products and services their customers are receiving. These ninety-minute sessions serve to strengthen the firm's relationship with important customers while surfacing real areas of opportunity to better meet customer needs. The customers in these meetings may be senior or midlevel managers in their own companies. The meetings are informal but structured around a few general questions for the customer:

- What are your strategies for growing your business?

- How can our firm best contribute to your success?

- Do you have unmet product or service needs that we could address?

- What is working well in our partnership with you?

- What do we need to change (start, stop, or modify) to enhance our value to you?

This same firm also has customers come into larger management meetings—such as the meeting of the top one hundred leaders in the firm, who gather on an annual basis. A benefit of these visits is that the attendees see that the leadership team is interacting directly with customers and values their feedback. This has a beneficial impact in modeling what the leadership team wants to occur at each level of the organization in focusing on customers and their needs.

A slightly different approach is followed by Mickey Drexler, CEO of the clothing company J. Crew. Drexler will frequently answer customer e-mails himself and is well known for calling customers when they contact the company with concerns. One customer was shocked that she received a call from Drexler just twenty minutes after she sent an e-mail complaining about pricing discrepancies (with different prices appearing for the same product in the firm's catalogues, website, and stores). Another example of his customer obsession occurred during one of his leadership team meetings in his New York headquarters. Drexler read to his team an e-mail from a customer complaining that no one, including J. Crew, sold leggings that were worth buying. Drexler then signaled for a woman standing nearby to introduce herself. She was the sender of the e-mail, and she took a few minutes to describe her concerns and what she wanted. She further noted how J. Crew's product had failed to meet her needs. Drexler's team then debated, in front of the customer, what they could do to meet an underserved need.9 At a CEO summit, Drexler commented on his willingness to get into these types of discussions: “Pay attention to details. I micromanage. I used to feel badly about it. People say you shouldn't micromanage because the textbooks say it or the business schools say it. Ask your customers if they'd like you to micromanage.”10 While Drexler has some unusual leadership techniques that would not work in some firms (such as regularly making announcements that are broadcast throughout the J. Crew headquarters building on an intercom system), he is notable in acting in a manner that reinforces for his staff the need to respond quickly and effectively to customer input.

Some firms go further by assigning key customer accounts to each member of the senior leadership team. In these cases, leaders take responsibility for customer accounts (in partnership with those inside the firm in sales who are working directly with those customers). The firm's chief financial officer might be assigned a customer account that requires both direct and indirect support for that customer and, more generally, the account. That executive then reports out to the leadership team at least once a year on progress being made with his or her customer account and also presents more general insights gleaned from the account regarding marketplace opportunities and threats. The intent is to create a customer ownership mentality and experience across the entire cadre of leadership team members, in contrast to what is found in many firms where only the commercial leaders have direct contact with customers. Xerox was known for doing this when Anne Mulcahy was the CEO of the company.

Another technique that allows you to see it for yourself is spending time with frontline employees making customer calls. Some firms use what they call ride-alongs to make this happen. The approach has leaders spending an entire day in the field with a sales representative seeing customers. The executive shadows the sales representative in every interaction he or she has that day with customers and colleagues. These ride-alongs are particularly important for leaders who have recently joined the firm as it gives them the look and feel of the business from a frontline point of view. They can see for themselves how the business operates, without the formality and “packaging” typically found when customer-facing groups make presentations to senior leaders about their business plans and results.

Leaders also need to understand how well their competitors are meeting customer needs. As noted in Chapter Three, some leaders underestimate their competitors, either ignoring them or seeing only the weaknesses. Steve Ballmer's initial dismissal of Apple's tablet as having fatal flaws (such as no keyboard and no Microsoft Office–like software) is a classic case of failing to see an emerging threat and to anticipate how customers would welcome this device. BlackBerry did the same in its first response to the newly introduced iPhone, which it viewed as trying to do the impossible in putting a computer in a phone. One way to overcome a natural tendency to demean a competitor is to go out and personally experience what your competitors have to offer and watch customers using their products and services. Sam Walton was known for going into the stores of the then much larger Kmart, clipboard in hand, and looking for what Kmart was doing right. Walton would carefully study his competition, identify the ideas that would make a difference, and then experiment with a similar approach in his own stores. He told his team to study the competition and focus on what could be learned, not from competitors’ weaknesses but from their strengths.

Some leaders are also using new technologies to understand their customers. Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz spends a great deal of time in his coffee shops around the world—in some cases working behind the counter as a barista. But he saw the need for more systematic customer feedback on how customers view his company. He launched a corporate blog called MyStarbucksIdea that has the feel of an online social network or blog. It offers three options for customers wanting to express their views—sharing an idea for a new product or service, voting on the merits of the ideas that others have submitted, or discussing an idea in some detail. There is also information on the blog about the ideas Starbucks has put into action. MyStarbucksIdea highlights the most popular ideas based on the number of votes a suggestion receives as well as comments on those suggestions. Some of the ideas the company has acted on are offering free wireless access in stores and providing drink rewards for regular customers. The Starbuck's website now has 180,000 users. They have submitted over 80,000 ideas, of which 50 have been implemented.11

A more recent and powerful approach is to mine big data to reveal customer interests and unmet needs. Although this is getting away from the personal contact with customers noted above, it is another tool leaders can use to understand customers and guard against the trap of becoming isolated from those using their products and services. NASCAR recently created the NASCAR Fan and Media Engagement Center to collect and analyze data from digital and social media (Facebook, Twitter, blogs, and so on), print and video sources, television, and radio. The amount of data being analyzed is enormous. NASCAR's center acquired up to sixty thousand fan tweets per minute during the Daytona 500 race. The content is broken out in a variety of ways to assess how fans are responding to a range of factors. A race team, for instance, may have painted its car a new color and wants to see how fans are responding. The team may change the color for the next race depending on the reaction. Or the center may see that fans are confused about a ruling on the track of a race in progress and, as a result, call the network covering the race and let staff there know that they should address this on the air.12

AWARENESS OF FRONTLINE COLLEAGUES

Another type of insularity occurs when leaders become detached from frontline employees. In particular, leaders need to personally see how effectively their strategies are being implemented across their organizations and at the front lines. My experience as a consultant is that most leaders are overly optimistic in that they believe their initiatives are being implemented more effectively than is actually the case. Years ago, I worked with a leader of a large corporation who sponsored a quality improvement effort to reduce errors in all areas of his business. He was passionate about the initiative and put ample time and money behind the effort. As part of the process, he would periodically meet with his top twenty-five leaders and talk about the need for improvement on the firm's quality metrics and leadership's role in making that happen. Two years into the process, he received data indicating that the improvement rate was much slower than he thought. He met one-on-one with a few of his team members to ask what was causing the lack of progress. Two of his direct reports asked if the initiative was really necessary and questioned whether it would produce the desired results. The leader was surprised that even members of his own team had doubts about a program that he thought was uniformly supported and being effectively implemented.

A second case of being out of touch with the front line involves a manufacturing company with an aggressive growth plan based in part on building new and very costly plants in emerging markets. The leader of the company came from a strategy and marketing background and had little experience with managing major construction projects. He had, however, a very senior leader heading up his construction group and delegated authority to him to manage these projects. As a result, the company leader spent little time visiting the various construction projects or going through the details of each project's progress. He felt that he was doing the right thing by empowering his construction project leader. He also didn't want to show his lack of knowledge in this area. This behavior carried over to his team meetings, where little group time was spent assessing progress on the key construction projects. Several of the key projects began to run behind schedule and experience major cost overruns. The construction leader had indicated he had everything under control when, in fact, he didn't. The company leader eventually had to intervene and replace him, but only after significant damage was done to the company and the leader's reputation.

There are several reasons why leaders don't spend more time interacting directly with frontline colleagues beyond the obvious constraints on their time. First, some leaders would rather spend time with members of their own headquarters team than with frontline employees. These executives are most comfortable working with a small inner circle of hand-selected and talented people whom they know and trust, typically the members of their leadership team or even a subset of that team. While it is politically incorrect for them to say so, they would just as soon skip interacting with customers and frontline employees. Clearly, there are leaders who enjoy interacting with people on the front lines, with notable examples in the past being Sam Walton at Wal-Mart and Herb Kelleher at Southwest Airlines. With these types of leaders, one gets the feeling that they would rather interact with frontline employees than do just about anything else. But some in leadership roles are uncomfortable talking with those at the lowest levels of their organizations. I recall one CEO who had a computer behind his desk with his firm's stock price showing on the monitor. As he was talking with people who came to meet with him in his office, he would periodically stop and look at the monitor to note any significant movement in his firm's share price or volume of trades. He was largely unknown to the frontline employees in his company and was seen by most as someone who was more comfortable with numbers than with people.

While it is politically incorrect for them to say so, some leaders would just as soon skip interacting with customers and frontline employees.

Another reason some leaders don't spend a great deal of time on their firms’ operations is that they don't want to appear to be micromanaging the next level of management, which some will see as the senior leader looking to get into details best left to others. I have also found that senior leaders want to avoid going into the organization and unknowingly contradicting what lower-level employees have heard from their immediate supervisors—potentially causing confusion in regard to the firm's strategies or progress in particular areas. A related issue is the distraction caused at the lower levels in a company when a senior leader arrives for a visit. In some firms, preparing for the leader's visit becomes more important than running the business. To avoid these potential problems, some senior leaders simply stay out of operations and, in so doing, become further isolated.

One leader who did stay in touch with those on the front lines is Admiral Mike Mullen, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff for the US military. Soon after being promoted to the position of senior military leader in the United States, he received a letter that said, in part, “Congratulations—Just remember one thing—from now on you will always eat well and you will never hear the truth again.” Mullen took this advice to heart and spent approximately 30 percent of his time visiting with soldiers on the front lines in hot spots around the world. His approach was to tell the troops he met, “You see it in a way that I can't. So I need help from you in seeing what's really going on. My life is full of information being provided to me that, you know, ‘Life is grand,’ as if I have forgotten that problems are tough.”13 Mullen made of point of asking his troops to give him an honest portrayal of what was happening on the front lines, knowing that his own staff would be likely to put a positive slant on the information they provided him. Another example of a leader reaching out to colleagues is Chip Bergh, who was appointed CEO of Levi Strauss & Co. after spending twenty-eight years with Procter & Gamble. On his arrival at Levi Strauss, he went on a listening tour, meeting with the top sixty-five people in his new company. He wanted to learn what he needed to know to take Levi Strauss, a company that had struggled after a period of rapid growth, to the next level. Bergh asked the same questions of each individual with whom he met:

- What three things must we preserve?

- What three things must we change?

- What do you hope I will do?

- What are you most concerned I will do?

- What advice do you have for me?

He spoke with each person for one hour, taking notes and probing for detail as needed. He found that some of the most useful feedback to his questions came when speaking with those who had a broad view of the company, such as his chief financial officer or senior human resource leader.14 One aspect of Bergh's approach that is worth emulating is his desire to obtain input from a wide range of people while at the same time being comfortable with the authority he had to make decisions. This was made somewhat easier by the fact that he was new to Levi Strauss. However, many leaders come into new roles thinking that they are expected to have “the answers,” and so they push ahead without taking into full account the views of those who are closest to the business. Of course, people's input will vary in how insightful or even accurate it is, but the leader benefits from at least understanding their points of view. Other leaders, such as Kevin Johnson, CEO at Juniper Networks, use an approach similar to Bergh's but in a group setting. In Johnson's case, he asked a similar set of questions of his leadership team and then left the conference room and let the group, with the help of a facilitator, discuss and then summarize their feedback. Johnson then came back into the room and heard what the group had to say.15

The founder of Staples, the office supply store, believed that leaders needed to immerse themselves in the front lines of their business. He wanted to reinforce this value by making it part of the integration of new senior-level hires. Those reporting to him were required, on joining the firm, to work their first week in one of the firm's retail stores, performing the basic tasks needed to operate a store—from unloading trucks to working with customers on the sales floor. The power of this practice was not only that it signaled the importance of understanding the business at a detailed level but also that it imprinted this understanding on executives when they were most impressionable. A leader's first weeks in a company are an opportune time to emphasize customer and operational awareness as well as other cultural values that are important to a firm's success.16

Some leaders make spending time with frontline colleagues part of their regular routine. Macy's CEO Terry Lungren devotes time each week to shopping in one of his stores. “I just go and pop into a store. And so we walk through the floor, and they have no time to prepare for my questions, they've had no time to prepare the store…. I learn as much by walking through a store as anything I do…. Much more than sitting in my office at my computer or holding a big meeting.”17 Mickey Drexler, mentioned above, is another leader who believes in getting out to his stores on a regular basis. His most enjoyable days include a store tour—what he calls a drop by. Drexler looks for ideas on each visit to a store and in his daily interactions with J. Crew's employees. His firm's entry into the wedding industry came after a telephone operator in J. Crew's catalogue division told Drexler that women were buying one of his firm's sundresses in lots of five or six to use as bridesmaids’ dresses. Drexler acted on the feedback, and J. Crew now has a pilot New York store focused exclusively on bridal wear. “This is what I love,” Drexler noted. “The business is small enough that we can easily make a difference. The customers want bridal; we do bridal. It's an experiment. Let's see if it works.”18

The leaders discussed in this chapter are constantly looking for information that will allow them to first see and then address weaknesses and opportunities. They also scan their organizations to determine how well their strategies are being implemented. One of my clients makes frequent visits to his operations and asks very direct questions that test individuals’ degree of knowledge of the strategies he is using to drive growth. He will ask such questions as, “How are the new iPads working with our sales force?” “Do the representatives like using them?” “Can you see an impact on our business?” and “How can we improve how they are being used?” He then goes one step further and asks his leadership team members to be his “scouts” and report back what they are seeing to him after they have visited the local offices. They know he expects them to be collecting information when they are in the operations, not only in regard to their own functional areas but also on the broader strategies being taken by the group in total. He uses the input to adjust his approach, both strategically and operationally. He also uses this process to assess the degree of insight about the business that each team member demonstrates in his or her reports to him.

Some leaders take a more informal approach, following what the founders of HP made famous decades ago: management by walking around. This approach is as simple as periodically walking the floors of the company office or building and spending time on discussions with those closest to the work. A few leaders go even further; they abandon their offices altogether, instead working in open spaces on the floor of their operations. Amancio Ortega, founder of a company that has revolutionized the way clothes are designed and produced, is reported to have never had an office. In many cases, he would sit at the workbenches with those making design decisions, discussing clothing colors and style trends with his staff. Other leaders work in open cubicles, seeking to maximize their daily interactions with colleagues and ensure that they are on top of the issues of the day.

Other leaders call their teams together frequently for a quick run-down of key issues. These are versions of the precinct meetings that occur each morning in many police departments, with the intent of ensuring that everyone is on the same page in regard to important information and what needs to be done that day. In companies, this is typically a weekly meeting where issues are surfaced and actions planned. The most famous of these may be the Saturday morning meetings that Sam Walton conducted in the early years when he ran Wal-Mart. He would pull together his team of managers to review key sales figures and competitor actions. The meeting would also lead to agreement on necessary actions for the following Monday, seeking to maximize performance during the following week. Walton initiated these meetings when Wal-Mart was just a single store in rural Arkansas. The firm continued these Saturday morning meetings in its headquarters building long after Wal-Mart had grown to dominate the retail landscape in the United States.

Technology also provides opportunities to collect necessary information about what is occurring in an organization. Wal-Mart has experimented with technology-based approaches to engage colleagues. A blog called Lee's Garage was set up by former Wal-Mart CEO Lee Scott to improve communications within the company after a wave of bad publicity about the firm's hiring and work practices. He wanted a direct channel to speed information up and down the hierarchy. Scott told the employees that he wanted to “[k]now what's on your mind and [I] will do my best to answer as many questions as I can. With more than a million associates in this country, answering each question personally would be a taller order than I can fill…. What I will do is answer questions where I see a common theme or questions that address culture, current reputation issues, retail issues or the overall business operation.”19 At first the site was accessible only to salaried managers, but it eventually was opened to all 1.3 million Wal-Mart employees in the United States. The questions posted on the website ranged from specific personal concerns (When will managers receive a raise?) to strategic issues (Will the merger of Sears and Kmart hurt Wal-Mart?). While most of the attention focused on the CEO's responses, the questions coming to him from people across Wal-Mart were as important in giving this CEO a better understanding of the issues that his colleagues wanted to discuss.

AWARENESS OF HIGH POTENTIALS

Leaders also benefit from increasing their awareness of high-potential individuals at various levels of the organization. These individuals often see things differently as a result of being, in most cases, younger than leadership team members and working at levels below that team. They can surface issues or inconsistencies that may be blindspots not only for the leader but also for his or her leadership team. Spending time with high-potential individuals also gives a leader an opportunity to personally assess the next generation of leadership in his or her firm.

Meetings with high-potential individuals typically focus on the following areas:

“I learn as much by walking through a store as anything I do…. Much more than sitting in my office at my computer or holding a big meeting.”

- What do you see as our firm's greatest opportunities for growth?

- What is the greatest threat or strongest competitor that we face in the marketplace? What actions do you suggest to address these threats?

- Overall, what is working well in the company today that we need to sustain?

- Overall, what needs to change in how we operate to improve our performance as a company? What is getting in the way of our performing at a high level?

- Do you have any feedback for me as a leader in the company (things I should continue, stop, or start)?

One risk in reaching out to high potentials is that the supervisors of these individuals can feel “exposed” when the senior leader is getting information directly from the next level of management (rather than going through the chain of command). They may believe they are being informally evaluated when their boss is indirectly obtaining information on their group and perhaps even their personal leadership effectiveness. This potential issue can be managed by setting an expectation that the senior leader is not striving to uncover incriminating information about a group or its leader but wants to learn directly how the business is operating and what the opportunities are for growth. A related risk is that the high-potential individuals may also feel vulnerable because they might say something that would contradict what their immediate bosses would want them to convey upward. My experience is that this concern is minor as long as the information obtained by the senior leader is handled with appropriate skill and not used in a manner that results in damaging the relationship between people and their bosses.

A leader with whom I worked had a “get to know” list that contained the names of the twenty highest-potential individuals working at the two levels of his organization immediately below his direct leadership team. This list is known to his leadership team but not publicized within the company or even communicated to the people who are on the list. It is kept private for two reasons. First, the senior leader doesn't want to create an inner group that is viewed as being above other groups and as excluding those who are not on the list. Second, the names on the list will change over time (as individuals and their achievements become better known). This leader meets informally with each individual on his list at least twice a year, often during his visits to the firm's local company offices. He sends an e-mail to the individual in advance, naming the topics that he would like to discuss, in order to reduce anxiety and prevent confusion regarding the purpose of the meeting. During the one-hour meeting, he engages the individual in an informal conversation about the opportunities and threats facing the business and the specific areas on which he would like input (in particular, the effectiveness of important corporate programs). He is also open to questions or input from the individuals on areas of importance to them, such as the growth opportunities in newer areas of the business or advice about the best way to develop as a leader.

A variation on the above approach is suggested by Gary Hamel, an author and consultant best known for his work on strategy. He recommends that CEOs develop a shadow cabinet of younger talent in their organizations. The senior leader meets with this group periodically to solicit their views on the strategic and operational challenges facing the business.20 The goal of the meetings, in part, is to determine whether the senior leader is hearing the same message from his or her own team as he or she is receiving from the members of this shadow cabinet. Another variation is to rotate membership in the group and make each get-together more of an informal meeting between the senior leader and the future generation of leaders in a company. The group then becomes more of an internal focus group, with the leader selecting topics on which he or she wants input and advice.

Approaches to getting to know the high potentials in a firm are as diverse as leaders themselves. Jeff Immelt, chief executive officer of GE, meets about twice each month with one of his firm's “Top 25” leaders in a Saturday session where they talk about their company and get to know each other as individuals. Immelt notes, “At that session, we are ‘two friends talking.’ I encourage an open critique of each other. Listening in this way has built trust and commitment. My top leaders want to be in a company where their voice is heard.”21 Immelt's approach is interesting in that he deliberately makes the meeting more informal by conducting it on a Saturday morning and making clear to the more junior leader that it is designed to be a conversation with a mutual sharing of views and ideas.

In every organization, there are people who are more knowledgeable than others about what is going on within a firm. Some refer to these people as the connectors who informally tie together an organization. Typically, these people have an extensive informal network of colleagues they know well across groups and levels. Some leaders identify and reach out to these individuals, asking them to update the leader on particular company-wide projects or emerging issues in the firm. One leader I know meets two or three times a year, one-on-one, with five or six selected individuals (some of whom he knows from earlier in his career within the firm). These informal discussions focus on the business and its level of progress in implementing key imperatives. Other leaders, using the same concept, identify a person who is very well connected, and is typically highly credible, and place him or her in a chief of staff role or some equivalent position. In this role reporting to the leader, they can provide ongoing feedback on what is going on in the company and become sentinels for issues that warrant the leader's attention. They become a regular source of valuable information on a variety of organizational issues, including the impact the leader has on those lower in the organization. Note, however, that these individuals should not become gatekeepers who filter information in a manner that further isolates the leader.

AWARENESS OF OUTSIDERS

One of the most common traps for a leader is to become a prisoner of his or her own industry or firm, with a corresponding diminution of awareness. Many individuals spend their entire careers in one industry and, in some cases, in one firm. These leaders know how to operate effectively in that context but run the risk of being out of step if their environment changes and the business model they know becomes outdated. They don't know what they don't know because they have seen only one way of doing things. In particular, they can take for granted assumptions about their markets and how their industry is evolving. These assumptions were most likely valid in the past but may have become obsolete over time with changes in the marketplace. One way out of this trap is to gain exposure to outside views, including those from other groups or industries. Gary Hamel notes that he once began a speech to a group of utility executives by saying:

“You guys have nothing to teach each other…. Now, if I could draw a third of this group from financial services, a third from utilities and a third from telecommunications, then we could have an interesting conversation.” That's because the utilities industry needs to understand how to price and manage risk, which is what they have learned how to do in financial services. And the telecommunications industry has already been confronting the issues of deregulation—splitting the network from the distribution…. My fundamental belief is that if a company wants to see the future, 80 percent of what it is going to have to learn will be from outside its own industry.22

When identifying outsiders from whom you would like to learn, consider the learning potential from each one relative to future challenges facing your firm. Possible target groups and individuals include those from

- Outside industries that are addressing challenges that your company is facing today or will encounter in the future

- Other regions of the world than those in which your industry or company has typically worked

- Academic institutions or think tanks that specialize in areas likely to become increasingly important to your company

- Consulting practices with expertise and experience in areas likely to become increasingly important to your company

A key attribute that underlies a leader's awareness of outsider groups and issues is curiosity. There are a myriad of leadership capability models, but many fail to highlight the importance of having a curious mind. Steve Jobs believed that his strength, and by extension Apple's strength as a company, was exploring the intersection between technology and the humanities. One early sign of this ability was evident in the development of the different fonts that Apple made available to customers, which were based on Jobs's interest in calligraphy. He felt that making great products required a broad sense of culture, a sense he believed was lacking in some of his competitors, such as Microsoft and Dell. Leaders need to master the details of their business but also need to remain curious about a broader range of topics that can enrich their ability to seize opportunities and recognize threats. Take, as an example, the experience of John Lasseter, who became one of the driving forces at Pixar Animation Studios. Lasseter's first job was with the Walt Disney Company, which hired him out of college, and he eventually found his way into the Disney animation studio. He was given permission to experiment with early forms of computer animation and eventually produced a short film demonstrating the possibilities of the new medium. He understood, before others, that computer animation was the future of the industry—offering new creative opportunities that would entertain people beyond what was currently being used. Lasseter presented this test clip to his supervisors, along with a proposal for making it into a full-length movie. His supervisors were interested in his new technology but only to the degree that it made Disney's existing approach to animation cheaper. After the meeting, Lasseter was told that his project was over and his job terminated. It turns out that his immediate supervisors at Disney were upset with him because he had lobbied for support for his project in a manner that they thought violated the firm's chain of command. He soon joined Pixar and made history as the creative force behind computer-animated blockbusters such as Toy Story. In an ironic twist, Disney eventually bought Pixar for $7.4 billion and made Lasseter the head of animation at both Disney and Pixar.23

I work with a leader who is among the most curious people I know. He is constantly seeking out people in different but useful areas to him and conducting general conversations where he seeks to understand how they view the world and what knowledge they have that might be useful to him. He deliberately seeks out people in academia, government, and those industries with competencies that may be useful to him. Each year, he targets areas of interest and then deliberately builds personal contacts in those areas. He is currently interested in accelerating organizational culture change and is talking with people in a variety of disciplines about their views on this topic. Or he may want to understand what is occurring in a company operating in a key regional market in which he and his firm have little experience.

Curiosity can also be an organizational trait. Samsung is viewed today as the primary competitor of Apple for dominance in a variety of markets, including smartphones, tablets, and computers. The story of this firm's success includes a decision made decades ago to place the company's most talented junior leaders in markets around the world on yearlong sabbaticals. The cost of the program created a number of internal critics within the firm, but the chairman at the time, Lee Kun-hee, was afraid that his company was too inward looking and was producing bland products that could not command higher margins. Initially, those in the program were given free rein to do what they thought was necessary to immerse themselves in the culture of their host country, including getting to know key figures in industry and government who might have some influence over Samsung's future success. At the end of the year, they had to write a report that summarized what they had learned. The program is now more structured than in the past, with a specific project that participants are expected to complete. Over five thousand employees have now gone through the program, which senior leadership has continued to support even though the cost is upward of $100,000 per employee.24

Another approach is to use outside experts to provide a different point of view on a firm's strategies or practices. A multinational industrial firm with whom I work has a strategy consulting group come in every two years to present its views on how the firm's industry is evolving and, more specifically, provide a critique of the firm's strategy, including the potential opportunities and weaknesses the consulting group sees. The leadership team then debates this input and determines whether additional analysis and work, often done internally, is needed.

Some leaders also want their team members to stretch their thinking by reading two or three books a year; they then discuss these as a team. In some cases these are business books, such as Good to Great or Blue Ocean Strategy. In other cases, leaders select biographies of business or political leaders, such as Walter Isaacson's book on Steve Jobs.25 Team members are given several months to read the book and think about the implications in regard to the future of their firm. A set of questions is developed for each book and sent to the team members for consideration. A facilitated discussion then occurs, led by an internal or external consultant. The goal is to explore different views of the book and lessons that can be applied within the firm. As an example, some teams debate the merits of Steve Jobs's leadership style—with a range of views, good and bad, regarding his effectiveness. The intent of the discussion is not to force team members to agree on one interpretation but, instead, to determine what they can collectively learn and apply in their own organization.

ACTIONS FOR INCREASING AWARENESS

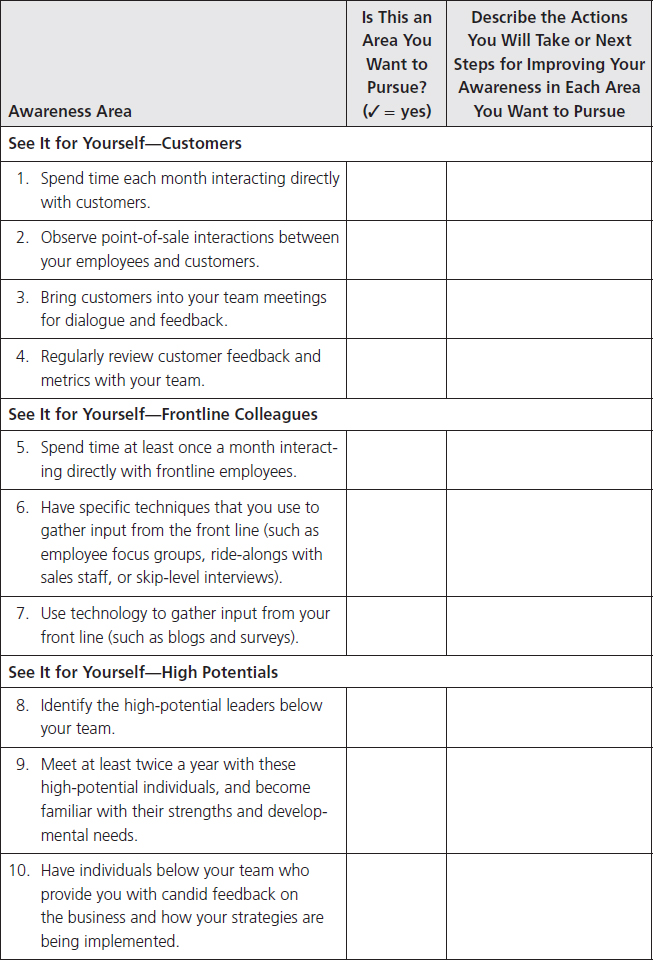

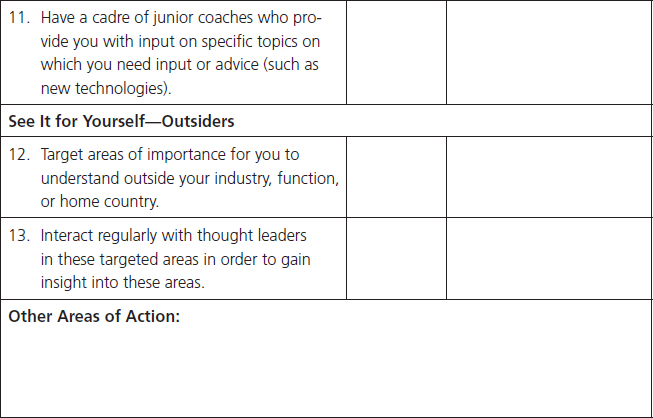

The following worksheet will help you target areas of opportunity for staying in touch with what is occurring in your team, organization, and markets.

SEE IT FOR YOURSELF: SUMMARY OF ACTIONS MOVING FORWARD

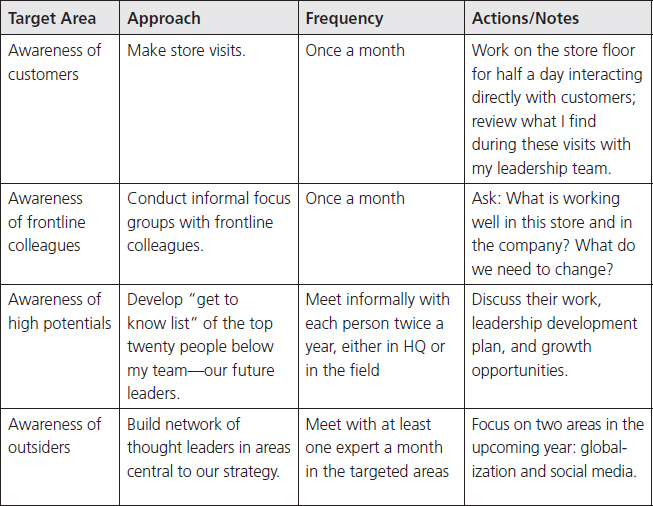

Once you have completed the worksheet, you will want to summarize your plan of action for the upcoming year, as shown in the example in the following table.

Increasing Awareness Plan of Action: Example

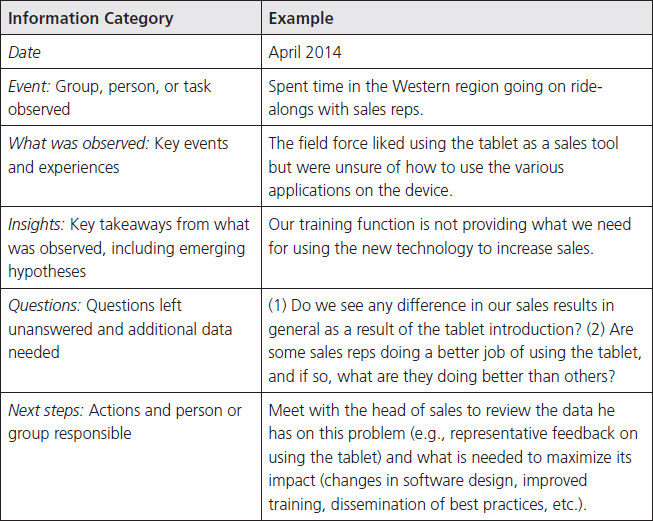

A final consideration is how best to use the information you gain from implementing your plan. Dorothy Leonard and her colleagues suggest that when you are acquiring new information, it helps to summarize it in a learning log.26 This tool helps leaders separate their observations from their interpretations of what is occurring and what needs to be done. In other words, it allows a leader to track his or her ideas and potential solutions in a more rigorous manner. The following table provides a modified and expanded example of what Leonard and her colleagues recommend. It illustrates how a leader might organize the firsthand information gathered during visits with frontline sales staff about their experiences with using newly issued tablet computers in their work.

Knowledge Gained from Seeing It for Yourself