CHAPTER

8

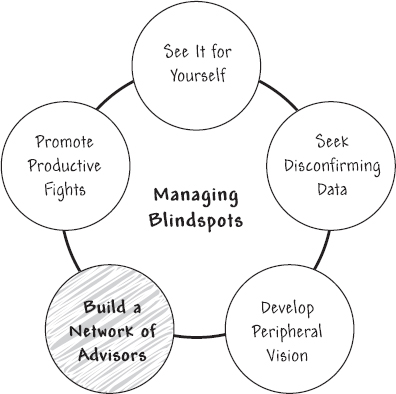

BUILD A NETWORK OF TRUSTED ADVISORS IN CRITICAL AREAS

Some individuals, on being promoted into senior leadership roles, experience a distinct sense of being on their own. They are now responsible for decisions that will determine the fate of their companies or groups—with implications not only for themselves but also for their colleagues, customers, and shareholders. I worked with a leader who pushed his firm to make a game-changing acquisition that resulted in a multibillion-dollar investment. He had a stable of business development staff, banking professionals, and legal advisors advising him on the acquisition. Still, when congratulated on closing the deal, he noted with a degree of unease, “We will know in three years if I made the right call.” He knew that his decision, despite all the advice and support he had received and the approval of his board, was his alone. His personal reputation was at stake as well as the future of his firm. His legacy would be determined by the outcome of this one decision.

Leaders also realize that many of those who provide them with advice on key decisions have their own agendas—including in some cases a desire to enhance their power and position within the company. This is not to say that people are inevitably self-serving. However, their views are influenced by how they view a situation, given where they sit, and what they gain from one course of action over another. Successful leaders learn to discern the extent to which the advice they are given is limited by the knowledge or motives of those offering it. A senior executive told me that he fully trusts very few people because most came to him either with a limited perspective of the challenges he faces (they view the business only from the vantage point of their own role or group) or with agendas of their own (they want a particular outcome that would benefit them or their groups). He took input from a variety of people but always screened their advice to determine the factors that were influencing it. For example, he saw the advantages of using large consulting firms for tasks that they performed better than his internal staff. Yet he thought these firms slanted their advice to him because they wanted to ensure future revenue for themselves. In particular, he believed they were less honest in their recommendations when they were trying to avoid alienating him or jeopardizing potential assignments.

Leaders, in most cases, also receive less supervisory feedback advice as they move up in a company. The chairman of a company, for instance, sees the CEO primarily in board meetings. The chairman rarely if ever observes the CEO working with his or her own team or with others inside the company. Robert Kaplan, an executive coach, notes, “While you may be ‘overseen’ by a board of directors or very senior boss, your superiors probably no longer closely observe your daily behavior. Instead, they now form their opinions of you based on your presentations in relatively formal settings or on secondhand reports from your subordinates. As a result of this, many executives find that as they become more senior, they receive less coaching and become more confused about their performance and developmental needs.”1

Dan Ciampa, an executive coach, suggests that selecting and using advisors wisely is a trait of great leaders.2 Astute leaders, understanding both the benefit and risk of using advisors, work hard to surround themselves with people who have the knowledge and skill needed to be useful sources of feedback and advice. They also want people around them who are strong enough to tell them when they are wrong.3 They realize that others, when carefully selected, can compensate for their own blindspots and weaknesses. Less effective leaders surround themselves with people who are supportive but do not challenge a leader's thinking and behavior when needed.

A vivid example of what can happen if you don't have a strong advice network is the case of former Hewlett-Packard chairman Patty Dunn. In an effort to find the source of a boardroom leak at HP, she approved a surveillance program run by an external security group. Dunn believed insiders were providing confidential company information to journalists. The security firm gathered private information about HP's board members and also the journalists who were writing the stories about HP's strategies. Dunn viewed the leaks as undermining the firm's credibility and personally embarrassing to her as the leader of the firm's board. A scandal erupted when it became public that the security firm she hired to investigate the leaks had obtained phone records and other personal information using illegal tactics. Dunn claimed she was unaware of the techniques being used but was ultimately forced to resign because of her role in the investigation.

Dunn didn't have anyone around her with the judgment or power to stop her from heading down a dangerous path.

It appears that Dunn didn't have anyone around her with the judgment or power to stop her from heading down a dangerous path. She and her team seemed to have been caught in the vortex of dealing with what they saw as a threat to the company and their own authority. Possibly, her team surfaced the risk but were still unable to influence her to take a different approach. Dunn's mistake, at a broader level, was in not building a group of advisors who could protect her from her own anger over the behavior of board members who were clearly working to undermine her authority.4

The leaders who select the wrong people to provide input to them or to act on their behalf in the organization face an equally problematic situation. Being “captured” by the wrong person is an all too common mistake, particularly for new leaders who are still assessing the team around them.5 Consider the CEO who made the mistake of selecting as his closest advisor an HR leader who created a toxic and highly political environment within the firm's leadership team. The CEO empowered this individual to act on his behalf in forcing change in the team and company. By the time the CEO realized his mistake, it was too late—key members of his leadership group had either withdrawn their support from him or left the firm. His choice of the wrong person to trust ended up eroding his credibility in the company and with his board and was one factor in his eventual departure from the firm.

Leaders will want to consider the following steps as they work to build a network of trusted advisors:

- Target the areas where you need advice.

- Match the type of advisor to your need.

- Maximize the advice you receive.

TARGET THE AREAS WHERE YOU NEED ADVICE

Dan Vasella, former CEO of Novartis, suggests that every leader needs a close confidant who can listen to his or her concerns—a board member or advisor whom the leader respects and can speak to in total candor.6 These people have a deep understanding of the leader's strengths and weaknesses and the challenges he or she faces. They show good judgment and can be trusted to keep conversations confidential. A leader, for instance, needs someone who can hear that he or she is fed up with the meddling of board members or the infighting among members of the executive team, or that the leader is tired after being on the job for six or seven years and is feeling worn out. This person plays a critical role in listening to concerns that the leader can express to very few people. However, leaders also need other advisors in a wide range of areas and are best served by identifying people who can provide value in each area, given their particular strengths and backgrounds. The following are areas in which advice is often needed by those in leadership roles:7

- Markets and strategy

- Technological innovation

- Organization and people

- Political dynamics

- Crisis management

- Personal impact

Markets and Strategy

Many executives are superb in regard to operational management and build their reputations as they move up by delivering on strategies that others develop. Fewer leaders are effective in thinking through long-term growth opportunities and risks. It is the single largest gap that I see at the top of companies. Leaders need to assess their own abilities in this area and determine what level of support they need. This support can come from both individuals inside a company and external resources (such as consultants, academics, and industry experts). Ideally, a leader wants support from those who understand his or her business in some depth but who at the same time are not limited by holding assumptions about markets and competitors that were true in the past but will not necessarily be true in the future. In other words, the advisors need to understand a firm's current business model but also must be able to think creatively about emerging opportunities and threats.

When looking inside the company for strategic support, you will want to search not only within your own team but also at the next level of management for those who can think strategically about the future. Assignments focused on strategic opportunities can both develop and test the capabilities of individuals to play a strategic role in charting the firm's future direction. You may also use more creative approaches, such as creating one or multiple workgroups of high-potential leaders to look at strategic challenges. These individuals should look at the business and ask open-ended questions of the type, “If you had to start our company from scratch today, what markets would we serve? What changes should we make, given your recommendations?” Other questions can be specific, such as “If we were to move into India in an aggressive manner, what key success factors would enable us to capture a necessary share of the market?” You should explain that while the firm might not adopt all of their proposals, you want to hear their point of view and recommendations.

External advisors can also help in making strategic choices. However, leaders need to take the time to assess their ability to extract the most from what outsiders have to offer. But it is clear that some leaders are better than others at understanding what these people can or can't provide, thus enhancing the value they gain from working with them. For example, some leaders expect their strategy consulting group to actively partner with company leaders to implement a new competitive strategy. As logical as this seems, many strategy groups are better at analysis than change management. In addition, they often focus on the senior leader and are not good at partnering with those at the next levels who need to execute a strategy. This becomes a problem only if the leader attempts to use them in a manner that does not play to their strengths, which are primarily in the analysis of market dynamics and options.

Technological Innovation

The role of technology varies depending on the industry and even the history of a particular company. Most leaders, however, need to have better insight into how technology is changing and its potential impact on their firm's competitive opportunities and risks. Predicting the future evolution of new technology is extremely difficult and requires input from a variety of sources—both internally and externally. Leaders also need to enhance their own understanding of newer technologies. GE's former CEO Jack Welch knew years ago that the Internet would be important to his firm's future success. He also knew that he had little knowledge in this area. As a result, he hired a personal mentor more than twenty-five years his junior to coach him on the Internet and encouraged his top five hundred managers to do the same.8 This technology advisor role can be filled by a variety of people, including a chief information officer or outside advisors from firms such as IBM, SAS, or Oracle or from the smaller, more focused technology consulting groups.

Organization and People

Leaders need a few people who can offer an independent view about how well the leader's organization or group is operating and, in particular, the amount of progress being made on key initiatives. Leaders are often overly optimistic and need someone who can give them the straight story on how corporate strategies are progressing. More generally, leaders need input on how the structure and culture of the firm is operating, and any misperceptions they hold in this area need to be corrected. As noted in Chapter Four, the leader can do this directly but also needs a confidant who can provide a second set of eyes on what is occurring. A related area in which a leader needs an independent perspective is the talent in the leader's team and at the next levels of the firm. Some of the most significant decisions a leader will make involve staffing, and it is easy for a leader to have blindspots about particular individuals. Senior leaders also need help with identifying high-potential leaders who are working lower in the organization. Often, the person offering advice on talent is the senior HR leader in the company or group, but others can also play this role. The key for the leader is to find those who are a keen judge of talent and willing to provide honest feedback regarding the performance, potential, and behavior of people on the leadership team as well as the next levels of the organization.

Political Dynamics

As leaders move into more senior-level roles, political dynamics become more pronounced. A case in point is Patty Dunn's conflicts with her own board at HP, described earlier, which became so severe that she took actions that eventually forced her to resign. Another example is destructive behavior among some leaders on an executive team as they compete for promotions and power. Leaders need an advisor who can offer advice on how to best manage through this political infighting, which can escalate to the point where it hurts a company and ruins careers. At points in most executive teams, members are positioning themselves on the question of who should be the next CEO (particularly when the current CEO is nearing retirement). Some members will seek to make their preferred candidate look better in the eyes of the board and the current CEO. Some will also seek to influence others on the team to back—often subtly but with clear intent—the person they believe should become CEO. The CEO needs input on how to manage this dynamic and on the actions needed to prevent political posturing from escalating to a level that damages the company.

Crisis Management

Leaders need a few people to whom they can turn for advice when they encounter a crisis either internally or externally. For example, a number of years ago Pepsi-Cola faced allegations that some of its cans had been found to contain syringes, and some people called for the CEO of Pepsi-Cola, Craig Weatherup, to pull his product off the shelves until the cause of the problem was identified.9 Some pointed to the example of Johnson & Johnson doing so after the fatal Tylenol tampering incident years earlier. Weatherup consulted with his internal public relations leader and then the senior corporate leadership at PepsiCo. He took in their advice on the best path forward. Weatherup decided not to conduct a recall—knowing that his firm's manufacturing process made it 99.9 percent sure that no foreign objects were in its beverage products. Instead, he personally went public with full disclosure of what his company knew about the tampering claims and his confidence that consumers were safe. Over time, not one of the hundreds of filed reports of syringes in soft drink cans turned out to be authentic.

One of the burdens of moving up is that the complexity of the decisions leaders face increases at the same time as their ability to reveal their vulnerabilities decreases.

A crisis is an opportunity to assess the strength of the advisors around a leader. Take as an example the CEO who wanted to make a highly visible acquisition, one that was at risk of failing due to a number of regulatory and financial obstacles. As the deal unfolded, he saw that some of his team members, most of whom he had known for years, were offering him poor advice on the action he needed to take to close the deal. He concluded that the stress of the deal had resulted in behaviors that he had not seen previously, and he altered his view of his team's ability to be of help during a crisis. Jamie Dimon commented in a similar manner when reflecting on the fallout from the London Whale crisis. After the trades became public knowledge, he observed that some members of his team acted “like children…. Instead of helping, they were running around with their heads chopped off, ‘What does this mean for me personally? How's my reputation?’” He noted that in these situations you learn the good and the bad about your team and whom you can count on.10

Personal Impact

A final area where advice is helpful involves a leader's impact. This area touches on all the previous areas but is more personal in dealing with the challenges facing a leader. In many situations, the leader's spouse can be helpful in that he or she knows the leader's personality, including strengths and weaknesses, and can talk with the leader knowledgeably about the more personal challenges of leading. A problem arises, however, when the spouse provides advice without having full access to the business. He or she is giving advice without necessary information and, in some cases, business experience. A spouse may also be less objective than needed in providing feedback to the leader. When I conduct developmental 360 assessments with leaders, I sometimes suggested that the leader discuss the results with his or her spouse. They want feedback on the feedback—in particular, what is on the mark. There are two likely outcomes when this occurs. The first is that the spouse is helpful in confirming at least some of the areas needing development (“I agree that you are condescending with those you don't respect,” or “The feedback is right—you do constantly interrupt people before they finish their point, jumping to your own conclusion”). The second, equally common, outcome is that the spouse becomes protective of the leader and finds fault with those suggesting that the leader needs to change. In these situations, the spouse makes it more difficult for the leader to recognize blindspots and the areas needing change. As a result, a leader often needs another person to provide more objective input on challenges of leading. Take the leader who gets input that he or she is conflict-averse. This leader needs someone with whom to discuss this feedback, its validity, and the options for addressing the problem. This individual, often an external coach or mentor, can provide a helpful point of view and recommendations on the areas that need to be addressed.

MATCH THE TYPE OF ADVISOR TO YOUR NEED

One of the burdens of moving up in a company is that the complexity of the decisions leaders face increases at the same time as their ability to reveal their vulnerabilities decreases. Leaders typically have only a few people on their teams with whom they are completely open. However, a leader takes risks in disclosing some opinions or personal information to subordinates, who may in turn disclose the information to others or use it in a manner the leader didn't intend. As noted earlier, each leader needs to carefully identify one or two people with whom he or she can be especially candid—people who know the leader and also have superb judgment. In addition, leaders may need several types of advisors in each of the preceding targeted areas (in areas such as strategy development); these include experts, coaches, mentors, and sponsors—people who can fill different roles for a leader, as described in the following pages.11

Experts

Experts are individuals who have deep knowledge in targeted areas, such as strategy or technology. They are important in providing information and recommendations based on their experience and knowledge. A consultant may have extensive experience in building productive relationships with the Chinese government and can provide advice to a CEO seeking to expand his business in that country. Another example of seeking expert advice is Joseph Jimenez, now CEO of Novartis, who remembers the time when he was promoted to head of a pharmaceutical division. His mandate was to bring a fresh perspective to the business. But he was not a scientist or physician and thus had a potential credibility gap with those he was leading. To get up to speed, Jimenez identified a lower-level scientist in his division who could teach him what he needed to know in regard to science and technology. Each week the two would meet and discuss the division's drug portfolio and the compounds in its R&D pipeline.12

Coaches

Coaches are individuals who observe the leader in action and have knowledge of best practices in organizational and leadership behavior. They provide feedback to the leader on his or her strengths as well as developmental areas. They suggest specific actions that the leader can take to improve his or her effectiveness. Andrew Gould, former CEO of Schlumberger, believed that leaders needed a coach who saw the leader in action and would be honest with him or her on what needed to change:

One of the first questions I ask senior executives is, “Who is your coach?” Many respond with a list of mentors who are outside the company or perhaps on the board of directors. These are “mentors” (versus coaches) because they do not directly observe the executive. Unfortunately, their advice is only as good as the narrative provided and often doesn't adjust for blind spots or the mentor's lack of professional familiarity with the executive. My follow-up question—“Who actually observes your behavior on a regular basis and will tell you things you don't want to hear?”—is often met with silence.13

Mentors

Mentors are individuals who have been in a role similar to the one occupied by the leader or a role to which the leader aspires. They are typically five to ten years older than the leader and as a result have more experience in the areas in which a leader needs to develop. In many cases, they are in the same company, although in some cases they work in different firms or industries. They offer both general advice and support in targeted areas (depending on the leader's needs). They view themselves as personally supporting the leader's ongoing development.

Sponsors

Sponsors are individuals who see a leader's potential and support his or her career advancement. They provide backing when needed but don't provide ongoing mentoring or coaching. They are not mentors in the manner described above but can be helpful to a leader moving up in a company or industry. This could be, for instance, a board member who provides support in helping a talented individual move into higher-level roles within a particular industry or firm.

MAXIMIZE THE ADVICE YOU RECEIVE

Building a robust network of advisors is an important first step in surfacing and managing your blindspots. A related step is effectively screening and using the advice offered by the individuals and groups discussed earlier. The best leaders ask the right questions to determine the quality of the advice they are getting. They could be looking to surface assumptions that might be inaccurate or to obtain the next-level details needed to ensure the accuracy of what they are being told. The best leaders also interact with others in a manner that makes these others better at giving advice. In particular, I have noticed over my years of consulting to senior leaders that some of my clients work with me in a manner that makes me better as a consultant. On some days, I see two or three clients, and I can feel the difference in how I work with them. My job is to adjust to their styles and needs in a manner that increases the value of my work with them. But in some cases they are the key to effectively using what I have to offer. Some leaders understand the areas in which I can add value and use me in ways that leverage my strengths relative to their needs. This doesn't mean they act on everything I recommend, but they get more value out of my advice than leaders do who are less adept at assessing what others can provide and then working with them in a manner that extracts that value.

The following offers some guidelines on how to maximize, in general, the value of the advice you receive:

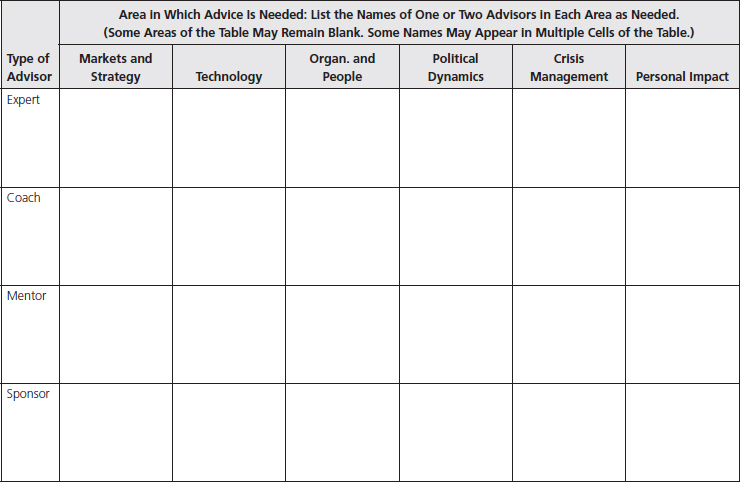

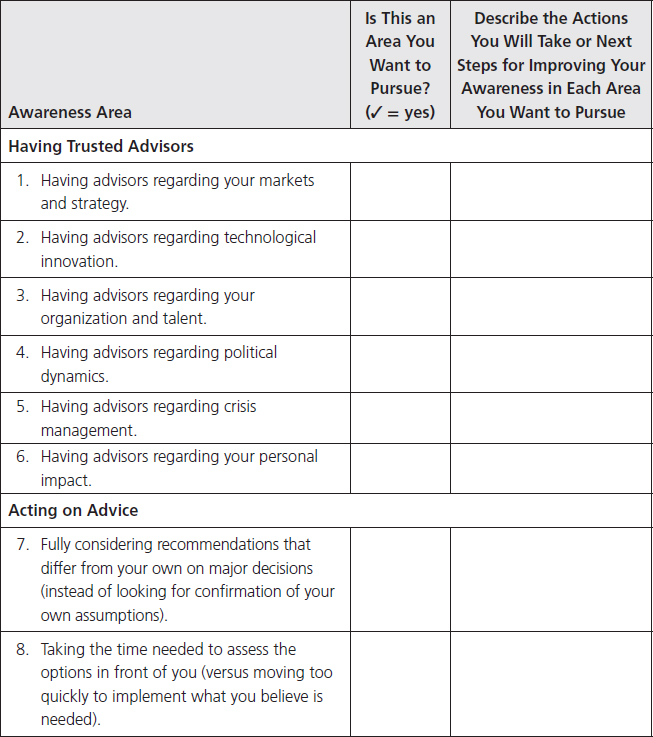

- Assess the breadth and quality of your support network. Using the “Network of Advisors” table is one way to assess the adequacy of the relationships you have in areas that are critical to your success. In each of these areas, you will want to determine if you have people who have good judgment and will be honest with you. You may also want a number of people who can offer second opinions in each area, to ensure that you don't become overly dependent on a single source of counsel. You want to ensure sufficient diversity in the views of those providing advice, to decrease the likelihood of overlooking key concerns. In the areas where you need advisors but have none, you will want to develop a plan to identify and build the relationships you need. Most useful is a twelve- to eighteen-month plan that targets areas of need (strategy, technology, and so forth) and potential individuals or groups who can provide necessary advice in those areas.

- Determine your criteria for selecting advisors. Each of the advice areas should be targeted as needed, depending on your specific challenges as well as your strengths and weaknesses. It is also helpful to be clear on the qualities you want in an advisor, which can vary depending on the level of advice needed—are you seeking an expert, coach, mentor, or sponsor? That said, several qualities are important in most situations. The first is appropriate expertise and deep experience in the area in which you want advice (strategy, technology, and so on). Second, they should have a good understanding of your company and its strategic priorities. Third, you want someone who is good at listening to your particular issues, doesn't jump to conclusions, and operates without a conflict of interest (or, if there is a potential conflict, puts your interests first). A fourth consideration is the chemistry between the two of you, although that should not necessarily mean that your conversations are free of tension. As noted earlier, many leaders make the mistake of surrounding themselves with those who provide support but will not push back on specific issues or offer critical feedback when needed. The advisor should be willing to challenge you with an in-depth understanding of your capabilities and personality quirks, which is important in knowing how to effectively provide you with what you need to hear in a given situation.14

- Invest in building your network.15 A network of advisors takes time to build, and savvy leaders pursue this before they have a need for advice or support. The need to do this well in advance is illustrated in the story of a sports promoter negotiating a deal with a client who wanted to develop a television package that would promote his company and its products. The client stipulated what he wanted and then asked what fee the promoter would charge for this service. The promoter stated the fee would be a million dollars. The customer agreed to the arrangement. The promoter then picked up his phone and made two quick calls to partners whose support he needed to make the arrangement happen. He then turned to the client and told him that everything was in place to move forward. The client, surprised at how quickly the arrangement was made, complained that the fee that he had just agreed to was excessive, given that the promoter had to make just two brief phone calls to put the TV promotion in place. The promoter looked at the client, handed him his cell phone, and said, “Then you make the calls.” The point of the story is that relationships that one builds before they are needed are invaluable and are a competitive advantage in that they can't easily be replicated by others.

- Test your advisors. Part of developing a robust network is qualifying the judgment of those on whom you rely for analysis and recommendations. You want to assess their competence as well any agendas or biases that may influence their recommendations. Many leaders do this only after a mistake is made. This was what occurred with President John F. Kennedy after the Bay of Pigs fiasco in 1961. Kennedy relied on a range of people in his government (CIA leadership, political advisors, and the like) who failed to alert him to the risks of the operation intended to oust the government of Fidel Castro. His father, Joseph Kennedy, commented after the operation failed that it was a blessing in that it taught his son how to better use those providing advice when he faced a crisis and, in particular, determine whom he could trust in a tough situation.16 The goal is to find opportunities (assignments, in-depth discussions, and so forth) that provide this level of insight before a major mistake is made.

- Ask for feedback on your overall effectiveness. A leader is well served by periodically asking for general input from advisors on how to improve his or her effectiveness. Some leaders, ensure that they go every year or so to four or five people who know them well and ask, “What can I do to improve my overall effectiveness?” The key is to select people who see the leader in action and to seek specific examples of what is missing or needed. For instance, a leader may hear that he or she needs to allow people more opportunity to voice their views on key issues in team meetings and exert less formal authority over the decision-making process. The leader then should ask, “To help me understand, give me an example of when I did or didn't do this in the past six months.” Then the leader needs to remain quiet and simply listen to the feedback, not offering any explanations or excuses for the behavior described.

- Ask for feedback on specific challenges. Another approach to maximizing the value of advisors is to ask for feedback in targeted areas and also actionable recommendations. I worked, for instance, with a CEO who heard, through one of his team members, that one of the firm's board members had commented that the leader needed to further clarify the strategy for the firm and more fully engage board members in strategic discussions. The leader asked me if I thought this feedback had any merit, given my exposure to him and the firm. I commented that during my work with the leader he had taken great pride in delivering quarterly results and also had expressed concerns that some of the board members did not understand the business in any detail. Thus it wouldn't surprise me if some of the board members viewed him as being more operational than strategic in his approach and didn't feel that he was fully engaging them in the larger strategic options he was considering. My history of working with the leader gave me the background that I needed to be useful to him in deciding how he wanted to handle this situation.

- Own the decision. Most leaders are comfortable making decisions and taking accountability for doing so (in fact, they enjoy being in that role). In some cases, they postpone making a decision and take time to think over potential options. There are, however, leaders who want others to make decisions for them. The Pepsi-Cola drink-tampering incident described earlier was personally managed by Craig Weatherup, who made the final call on how to handle what might have been a disaster for his firm had it proven true. Some leaders in that situation might have turned to the head of public relations and said, “You make the decision and I will back you up.” Leaders should delegate when possible but can't do so when a decision has such a broad impact on the success of a firm. Advisors offer advice—leaders make and own the decision.

Successful leaders have a strong belief in their own abilities … the best and brightest can easily come to believe that following anything other than their own convictions is foolish.

Successful leaders have a strong belief in their own abilities and often have a stubborn streak to match it. The best and brightest leaders can easily come to believe that following anything other than their own convictions is foolish. Michael Bloomberg, former mayor of New York and founder of a media empire, has said, ‘‘Stubborn isn't a word I'd use to describe myself; pigheaded is more appropriate. To a contrarian like me, constant advice not to do something almost always starts me quickly down the risky, unpopular path.”17 Most leaders can recall situations where people gave advice that they ignored and the leader's view turned out to be correct. Many can also recall situations in which they took what turned out to be bad advice from others and failed.

Leaders often view these prior instances as proof of their superior judgment and a reminder to themselves of the need to follow their own intuition. The issue here is that many people have a tendency to forget the situations in which their intuition led them down the wrong path. Instead, they blame others or larger situational factors that they view as being beyond their control. This results in a belief that “mistakes were made, but not by me.” In many of these cases, the leader has personalized the decision, has dug in on a preferred course of action, and has lost the ability to be objective.

Michael Maccoby calls some leaders productive narcissists. These are leaders whose self-belief and passion to “change the world” can produce benefits for their companies yet can also pose clear risks.18 In regard to advice, narcissistic leaders are often emotionally removed from others and inclined to be distrustful of advice offered by others. As a result, consciously or not, they don't view debates with their teams as an effort to explore different options. Instead, they view the process as a way to test their own ideas—which they then modify as needed. Some, when they do change their minds, come to believe that the newly accepted idea was in fact their original idea—a process that can cause disbelief in those who are seeing it for the first time. The risk for these leaders is that they will both outrun their own capabilities and fail to develop a group of people to whom they will listen, people who can counterbalance their weaknesses and warn them when they are about to make a major mistake.

ACTIONS FOR BUILDING A NETWORK OF TRUSTED ADVISORS

The following worksheets are designed to help you target and develop a network of advisors who can surface and address your blindspots.

BUILDING A NETWORK OF TRUSTED ADVISORS: SUMMARY OF ACTIONS MOVING FORWARD

The table that follows can be used to outline the network of advisors that you targeted in each area. Note that one person can appear in multiple cells of the table and that some cells in the table can remain empty (sponsors, for instance, are not needed in every area). Advisors can be external to your company as well as internal.