Chapter 1

Exploring Mindfulness in the Workplace

In This Chapter

![]() Identifying what mindfulness is and is not

Identifying what mindfulness is and is not

![]() Retraining your brain

Retraining your brain

![]() Getting started

Getting started

In tough economic times, many organisations are looking for new ways to deliver better products and services to customers while simultaneously reducing costs. Carrying on as normal is not isn’t an option. Organisations are looking for sustainable ways to be more innovative. Leaders must really engage staff, and everyone needs to become more resilient in the face of ongoing change. For these reasons, more and more organisations are offering staff training in mindfulness.

Major corporations in the USA, like General Mills, and major employers in the UK, such as the National Health Service, have offered staff mindfulness training in recent years. Google and eBay are among the many companies that now provide rooms for staff to practise mindfulness in work time. Business schools including Harvard Business School in the USA and Ashridge Business School in the UK now include mindfulness principles in their leadership programmes.

So what is mindfulness, and why are so many leading organisations investing in it?

Becoming More Mindful at Work

In this section you will discover what mindfulness is. More importantly, you’ll also discover what mindfulness is not! You’ll find out how mindfulness evolved and why it’s become so important in the modern day workplace.

Clarifying what mindfulness is

Have you ever driven somewhere and arrived at your destination remembering nothing about your journey? Or grabbed a snack and noticed a few moments later that all you have left is an empty packet? Most people have! These examples are common ones of ‘mindlessness’, or ‘going on automatic pilot’.

Like many humans, you’re probably ‘not present’ for much of your own life. You may fail to notice the good things in your life or hear what your body is telling you. You probably also make your life harder than it needs to be by poisoning yourself with toxic self-criticism.

Mindfulness can help you to become more aware of your thoughts, feelings and sensations in a way that suspends judgement and self-criticism. Developing the ability to pay attention to and see clearly whatever is happening moment by moment does not eliminate life’s pressures, but it can help you respond to them in a more productive, calmer manner.

Learning and practising mindfulness can help you to recognise and step away from habitual, often unconscious emotional and physiological reactions to everyday events. Practising mindfulness allows you to be fully present in your life and work and improves your quality of life.

Mindfulness can help you to:

- Recognise, slow down or stop automatic and habitual reactions

- Respond more effectively to complex or difficult situations

- See situations with greater focus and clarity

- Become more creative

- Achieve balance and resilience at both work and home

Mindfulness at work is all about developing awareness of thoughts, emotions and physiology and how they interact with one another. Mindfulness is also about being aware of your surroundings, helping you better understand the needs of those around you.Mindfulness training is like going to the gym. In the same way as training a muscle, you can train your brain to direct your attention to where you want it to be. In simple terms, mindfulness is all about managing your mind.

Taking a look at the background

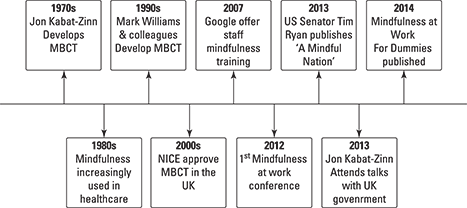

Mindfulness has its origins in ancient Eastern meditation practices. Jon Kabat-Zinn developed Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) in the USA in the late 1970s, which became the foundation for modern-day mindfulness. Figure 1-1 shows how it developed.

Figure 1-1: Mindfulness timeline.

In the 1990s Mark Williams, John Teasdale and Zindel Segal further developed MBSR to help people suffering from depression. Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) combined cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) with mindfulness. In 2004, MBCT was clinically approved in the UK by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) as a ‘treatment of choice’ for recurrent depression.

Since the late 1970s, research into the benefits of mindfulness has steadily increased. Recent studies have examined, for example, the impact of practising mindfulness on the immune system and its effects on those working in high pressure environments.

Advances in brain scanning technology have demonstrated that as little as eight weeks of mindfulness training can positively alter brain structures, including the amygdala (the fear centre) and the left prefrontal cortex (an area associated with happiness and well-being). Other studies show benefits in even shorter periods of time.

Busy leaders who practise mindfulness have long extolled its virtues, but little research has existed to back up their claims. Fortunately, researchers are now increasingly focusing their attention on the benefits of mindfulness from a workplace perspective.

MBSR and MBCT are taught using a standard eight-week curriculum, and all teachers follow a formalised development route. The core techniques are the same for both courses. Most workplace mindfulness courses are based around MBCT or MBSR, but tailored to meet the needs of the workplace.

Although MBSR and MBCT were first developed to help treat a range of physical and mental health conditions, new applications for the techniques have been established. Mindfulness is now being taught in schools and universities, and has even been introduced to prisoners. Many professional education programmes, such as MBAs, now include mindfulness training.

Researchers have linked the practice of mindfulness to skills that are highly valuable in the workplace. Research suggests that practising mindfulness can enhance:

- Emotional intelligence

- Creativity and innovation

- Employee engagement

- Interpersonal relationships

- Ability to see the bigger picture

- Resilience

- Self-management

- Problem solving

- Decision making

- Focus and concentration

In addition, mindfulness is valuable in the workplace because it has a positive impact on immunity and general well-being. It has been demonstrated to relieve the symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress. See www.mawt.co.uk for a list of some of the research papers on mindfulness at work.

Recognising what mindfulness isn’t

Misleading myths about mindfulness abound. Here are a few:

Myth 1: ‘I will need to visit a Buddhist centre, go on a retreat or travel to the Far East to learn mindfulness.’

Experienced mindfulness instructors are operating all over the world. Many teachers now teach mindfulness to groups of staff in the workplace. One-to-one mindfulness teaching can be delivered in the office, in hotel meeting rooms or even via the web. Some people do attend retreats after learning mindfulness if they wish to deepen their knowledge, experience peace and quiet or gain further tuition, but doing so isn’t essential.

Myth 2: ‘Practising mindfulness will conflict with my religious beliefs.’

Mindfulness isn’t a religion. For example, MBSR, MBCT are entirely secular – as are most workplace programs. No religious belief of any kind is necessary. Mindfulness can help you step back from your mental noise and tune into your own innate wisdom. Mindfulness is practised by people of all faiths and by those with no spiritual beliefs. Practising mindfulness won’t turn you into a hemp-clad tofu eater, a tree-hugging hippie or a monk sitting on top of a mountain – unless you want to be one of these people, of course!

Myth 3: ‘I’m too busy to sit and be quiet for any length of time.’

When you’re busy, the thought of sitting and ‘doing nothing’ may seem like the last thing you want to do. In 2010 researchers at Harvard University gathered evidence from a quarter of a million people suggesting that, on average, the mind wanders for 47 per cent of the working day. Just 15 minutes a day spent practising mindfulness can help you to become more productive and less distracted. Then you’ll be able to make the most of your busy day and get more done in less time. When you first start practising mindfulness, you’ll almost certainly experience mental distractions, but if you persevere you’ll find it easier to tune out distractions and to manage your mind. As time goes on, your ability to concentrate increases as does your sense of well-being and feeling of control over your life.

Myth 4: ‘Practising mindfulness will reduce my ambition and drive.’

Practising mindfulness can help you become more focused on your goals and better able to achieve them. It can help you become more creative and to gain new perspectives on life. If your approach to work is chaotic, mindfulness can make you more focused and centred, which in turn enables you to channel your energy more productively. Coupled with an improved sense of well-being, this ability to focus helps you achieve your career ambitions and goals.

Myth 5: ‘If I practise mindfulness, people will take me less seriously and my career prospects will be damaged.’

Some of the most successful and influential people in the world practise mindfulness. US Senator Tim Ryan, Goldie Hawn, Joanna Lumley and Ruby Wax are all keen advocates of mindfulness. Practising mindfulness doesn’t involve sitting cross-legged on the floor – an office chair is fine. If you find it impossible to sit quietly and focus because you work in an open-plan office, or you’re concerned about what others think, plenty of other everyday activities are available that can become opportunities to practise mindfulness that nobody will notice. Walking, eating, waiting for your computer to boot up or even exercising at the gym are all good opportunities to practise mindfulness. Mindfulness can be practising with your eyes open, whilst you’re moving around during the day.

Myth 6: ‘Mindfulness and meditation are one and the same. Mindfulness is just a trendy new name.’

Fact: Mindfulness often involves specific meditation practices. Fiction: All meditation is the same. Many popular forms of meditation are all about relaxation – leaving your troubles behind and imagining yourself in a calm and tranquil ‘special place’. Mindfulness helps you to find out how to live with your life in the present moment – warts and all – rather than run away from it. Mindfulness is about approaching life and things that you find difficult and exploring them with openness, rather than avoiding them. Most people find that practising mindfulness does help them to relax, but that this relaxation is a welcome by-product, not the objective!

Training your attention: the power of focus

Are you one of the millions of workers who routinely put in long hours, often for little or no extra pay? In the current climate of cutbacks, job losses and ‘business efficiencies’, many people feel the need to work longer hours just to keep on top of their workload. However, research shows that working longer hours does not mean that you get more done. Actually, if you continue to work when past your peak, your performance slackens off and continues to do so as time goes on (see Chapter 5).

Imagine your job is to chop logs. After a while, your axe needs sharpening and your muscles need resting. If you keep going, you’ll become very inefficient and are more likely to have an accident. By taking a break, and sharpening your axe, you can return to the job and get more done in less time. You’ll probably enjoy the job more too. Mindfulness practice is like taking that break – you both re-energise yourself and sharpen your mind, ready for your next activity.

Discovering how to focus and concentrate better is the key to maintaining peak performance. Recognising when you’ve slipped past peak performance and then taking steps to bring yourself back to peak is also vital. Mindfulness comes in at this point. Over time, it helps you focus your attention to where you want it to be.

Focus your full attention on your chosen object, sound or sensation and nothing else. Then consider these questions:

- Did you manage to focus your complete attention for the full 90 seconds, or did your mind wander and random thoughts arise?

- Did you become distracted by a bodily pain or ache?

- Did you find yourself getting annoyed with yourself, or annoyed with a sound such as a ticking clock or traffic?

You’re not alone! Most people find this activity really difficult at first. In truth, you’re unlikely to ever be able to shut out all of your mental chatter, but you can turn the volume right down. Doing so enables you to see things more clearly, reduce time wasted on duplicated work and stop your mind wandering. Mindfulness offers you a way of getting more done in less time without burning yourself out.

Applying mindful attitudes

Practising mindfulness involves more than just training your brain to focus. It also teaches you some alternative mindful attitudes to life’s challenges. You discover the links between your thoughts, emotions and physiology. You find out that what’s important isn’t what happens to you, but how you choose to respond that matters. This statement may sound simple, but most people respond to situations based on their mental programming (past experiences and predictions of what will happen next). Practising mindfulness makes you more aware of how your thoughts, emotions and physiology impact on your responses to people and situations. This awareness then enables you to choose how to respond rather than reacting on auto-pilot. You may well find that you respond in a different manner.

By gaining a better understanding of your brain’s response to life events, you can use mindfulness techniques to reduce your ‘fight or flight’ response and regain your bodies ‘rest and relaxation’ state. You will see things more clearly and get more done.

Mindfulness also brings you face to face with your inner bully – the voice in your head that says you are not talented enough, not smart enough or not good enough. By learning to treat thoughts like these ones as ‘just mental processes and not facts’, the inner bully loses its grip on your life and you become free to reach your full potential.

These examples are just a few of the many ways that a mindful attitude can have a positive impact on your life and career prospects.

Finding Out Why Your Brain Needs Mindfulness

Recent advances in brain scanning technology are helping us to understand why our brain needs mindfulness. In this section you discover powerful things about your brain – its evolution, its hidden rules, how thoughts shape your brain structure and the basics of how your brain operates at work.

Evolving from lizard to spaceman

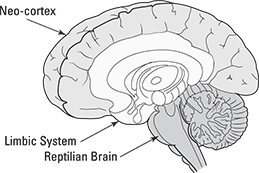

In order to understand how mindfulness works, you need to know some basics about the human brain. Over millions of years, the human brain has evolved to become the most sophisticated on the planet (see Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2: Evolution of the human brain.

The oldest part of the brain is known as the reptilian brain. It controls your body’s vital functions such as heart rate, breathing, body temperature and balance. Your reptilian brain includes the main structures found in a reptile’s brain: the brainstem and the cerebellum.

The middle part of your brain is known as the limbic brain. It emerged in the first mammals. It records memories of behaviours that produced agreeable and disagreeable experiences for you. The limbic system is responsible for your emotions and value judgements. The reptilian brain and limbic system are quite rigid and inflexible in how they operate. We call these two areas the primitive brain.

The newest part of our brain consists is the neo-cortex. It has deep grooves and wrinkles that allow the surface area to increase far beyond what could otherwise fit in the same size skull. It accounts for around 85 per cent of the human brain’s total mass. Some say that the neo-cortex is what makes us human. The neo-cortex is responsible for your abstract thoughts, imagination and consciousness. For simplicity, we call it the ‘higher brain’. The higher brain is highly flexible and has an almost infinite ability to learn.

The primitive brain deals with routine tasks and needs little energy to operate quickly. The higher brain is incredibly powerful, but requires a lot of energy to run and operates more slowly than the primitive brain. These differences in the different parts of the brain explain why you often experience strong emotions or take action long before logic starts to kick in. It also explains the human tendency to work on auto-pilot (based on responses stored in the primitive brain) for much of the time.

Because you spend much of your time work on auto-pilot, you’re often unaware of your thoughts, emotions and physiology in the present moment. The short activity below is designed to help you recognise your routineresponses and how changing them just slightly can make you more aware of them.

Sit in a different chair from usual in a meeting, park in a different spot in the car park, sleep on the other side of the bed or use a different hand to write with.

Sit in a different chair from usual in a meeting, park in a different spot in the car park, sleep on the other side of the bed or use a different hand to write with.- Observe your thoughts, emotions and bodily responses.

- Identify how you felt. Did you find changing your behaviour difficult? Did you feel awkward?

Doing things differently can be hard because your mental programming is probably screaming, ‘You’ve got it wrong; that’s not how you do it.’ Carrying out an activity in a new way involves conscious thought, and thus engages your higher brain, which needs more energy to function. This explains why even small changes can feel difficult or uncomfortable.

Discovering your brain’s hidden rules

Imagine yourself as one of your ancient ancestors – a cave dweller. In ancient times you had to make life or death decisions every day. You had to decide whether it was best to approach a reward (such as killing a deer) or avoid a threat (such as a fierce predator charging at you). If you failed to gain your reward, in this example a deer to eat, you’d probably live to hunt another day. But, if you failed to avoid the threat, you’d be dead, never to hunt again.

As a result of facing these daily dangers, your brain has evolved to minimise threat. Unfortunately, this has led to the brain spending much more time looking for potential risks and problems than seeking rewards and embracing new opportunities. This tendency is called ‘the human negativity bias’.

Think of six bad things that have happened recently.

Think of six bad things that have happened recently.- Think of six good things that have happened recently.

- Identify which task you found easiest.

Most people readily conjure up six bad things, but struggle to think of six good things. The bad things dominate because the brain is primed to expend more energy looking for potential threats (bad things) than looking for opportunities (good things).

When your brain detects a potential threat, it floods your system with powerful hormones designed to help you evade mortal danger. The sudden flood of dozens of hormones into your body results in your heart rate speeding up, blood pressure increasing, pupils dilating and veins in skin constricting to send more blood to major muscle groups to help you sprint away from danger. More oxygen is pumped into your lungs, and non-essential systems (such as digestion, the immune system and routine body repair and maintenance) shut down to provide more energy for emergency functions. Your brain starts to have trouble focusing on small tasks because it’s trying to maintain focus on the big picture to anticipate and avoid further threat.

Threat or risk avoidance is controlled by the primitive areas of your brain, which operate fast. This speed explains why, when you unexpectedly encounter a snake in the woods, your primitive brain decides on the best way to keep you safe from harm with no conscious thought and you jump out of the way long before your higher brain engages to find a rational solution.

This process is great from an evolutionary perspective, but can be bad news in modern-day life. Many people routinely overestimate the potential threat involved in everyday work such as a critical boss, a failed presentation or social humiliation. These modern-day ‘threats’ are treated by the brain in exactly the same way as your ancestor’s response to mortal danger. This ‘fight or flight’ response was designed to be used for short periods of time. Unfortunately, when under pressure at work it can remain activated for long periods of time. This activation can lead to poor concentration, inability to focus, low immunity and even serious illness.

Mindfulness training helps you to recognise when you’re in this heightened state of arousal and be able to reduce or even switch off the ‘fight or flight’ response. It also helps you develop the skill to trigger at will your ‘rest and relaxation’ response, bringing your body back to normal, allowing it to repair itself and increasing both your sense of well-being and ability to focus on work.

Recognising that you are what you think

For many years it was thought that once you reached a certain age your brain became fixed. We now know that the adult brain retains impressive powers of ‘neuroplasticity’; that is, the ability to change its structure and function in response to experience. It was also believed that, if you damaged certain areas of the brain (as a result of a stroke or other brain injury), you’d no longer be capable of performing certain brain functions. We now know that in some cases the brain can re-wire itself and train a different area to undertake the functions that the damaged part previously carried out. The brain’s hard wiring (neural pathways) change constantly in response to thoughts and experiences.

Neuroplasticity offers amazing opportunities to re-invent yourself and change the way you do and think about things. Your unique brain wiring is a result of your thoughts and experiences in life. Blaming your genes or upbringing; saying ‘it’s not my fault, that’s how I was born’ isn’t no longer a good excuse!

In order to take advantage of this knowledge, you need to develop awareness of your thoughts, and the impact that these thoughts have on your emotions and physiology. The problem is that, if you’re like most people, you’re probably rarely aware of the majority of your thoughts. Let’s face it; you’d be exhausted if you were! Mindfulness helps you to develop the ability to passively observe your thoughts as mental processes. In turn, this allows you to observe patterns of thought and decide whether these patterns are appropriate and serve you well. If you decide that they’re not, your awareness of them gives you the opportunity to replace them with better ways of thinking and behaving.

For example, if you arrive at work and think ‘Oh no, I’ve got so much to do on my to-do list. I’m never going to get them all done! I’m so inefficient …’ and so on, your brain is on a negative thought stream. Mindfulness helps you to catch yourself doing that, and instead, simply and more calmly move your attention to the first priority on your list of things to do.

Another common problem you may encounter is that, although you may think that your decisions and actions are always based on present-moment facts, in reality they rarely are. Making decisions based on your brain’s prediction of the future (which is usually based on your past experiences and unique brain wiring) is common. In addition, you see with your brain; in other words, your brain acts as a filter to incoming information from the eyes and picks out what it thinks is important. The problem with all the above is that you routinely make decisions and act without full possession of the facts. What happened in the past will not necessarily happen now; your predictions about the future could be inaccurate, leading to inappropriate responses and actions.

So, going back to the above example of the long to-do list, if you’re mindful, you can choose to do what’s most important, rather than just automatically reacting to the last email that pings you.

Practising mindfulness helps you to see the bigger picture and make decisions based on present-moment facts rather than self-generated assumptions and fiction.

Here’s another example. When you’re under pressure, falling into a thought spiral, with one thought driving the next, is all too easy. In the process, you develop your own story of what’s going on around you, which can be wildly different from reality. For example, if you fail to get an invite to a meeting at work you think you should be at, your thoughts might follow this pattern:

- Why haven’t they invited me?

- They obviously think that my team and I have nothing to contribute.

- Maybe they’re discussing redundancies.

- Maybe they haven’t invited me because they’re discussing making me redundant!

- At my age I’ll never get another job!

- How will I pay off the remainder of the mortgage?

- This may mean my son has to drop out of university.

- I’ll ruin my son’s life. I’m a dreadful father.I’m such a loser.

In reality, the failure to invite you was an administrative error, but your mind has created a detailed story, which your brain has treated as reality. As a result your brain has triggered emotions (anger or fear), your body has become tense and your heart rate has speeded up. Your emotions and physiology have a further impact on your thoughts and behaviour, and so on.

Many people fall into this trap. Mindfulness helps you to notice when your thoughts begin to spiral and to take action to stop them spiralling down even further. You can observe what’s going on in the present moment, and separate present-moment facts from self-created fiction. This ability gives you choices and a world of new possibilities.

- Observe what’s going on in your head. Identify patterns of thoughts, as if you were a spectator observing from the outside. What is it specifically that has triggered your primitive brain?

- Acknowledge your emotional response without judgement or self-blame. Try to observe from a distance and see if you can reduce or prevent a strong emotional reaction by observing the interplay of your thoughts and emotions as if you were a bystander.

- Be kind to yourself. You’re human, and just responding according to your mental wiring. Observe both your thoughts and emotions as simply ‘mental processes’, without the need to respond to them. Regarding them as ‘thoughts not facts’ and being kind to yourself helps to encourage your primitive brain to let go of the steering wheel and allow your higher brain to become the driver once more.

When developing new neural pathways, practice makes perfect. Changing your behaviour or learning to do something new takes awareness, intention, action and practice – no short cuts exist! Understanding a few simple facts about how your brain works and making small adjustments to your responses can help you to create new, more productive, neural pathways.

Exploring your brain at work

Before diving into more detail about mindfulness, and how it could be of benefit to your work, you need to discover a little more about how your brain processes everyday work tasks.

Let’s look at a real-life example. A friend of mine (Juliet) – let’s call her Jen – is a senior manager working within a police training organisation, where she is responsible for leading a team who develop doctrine (guidance and standards) for police forces across the UK. Her job description includes the following desirable characteristics:

- Organisational skills

- Communication skills

- Ability to manage conflicting priorities

- Problem-solving skills

- Decision-making skills

- Relationship building skills

- Ability to manage change

One of the most challenging aspects of Jen’s work is managing multiple, often conflicting, demands. As her role is national, she is responsible to multiple stakeholders working in different police forces and affiliate organisations across the UK. Problems sometimes arise when stakeholders think that their project is more important than other projects, and completion of that project by a certain date takes on an almost ‘life or death’ importance in their minds. This elevated importance is often compounded by senior stakeholders taking sides and applying pressure. When this situation arises, Jen uses negotiation skills to try to resolve the issue. She gives the stakeholders a reality check, often along the lines of, ‘If I prioritise this, then I can’t do that’ or ‘If I do this first, that will be late’.

At times like these, Jen notices her body tensing. She sometimes wakes at 2 a.m. trying to find a solution that resolves the conflict for all concerned. Emotionally she sometimes experiences irritation and frustration at the inability of others to see the bigger picture. Her thoughts run along the following lines: ‘Either I’m not explaining it right or they’re being obtuse’; ‘We’re all supposed to be professionals, why can’t they behave as such?’; ‘No one will die if we’re a few days late with this project’; ‘Why are they acting so selfishly?’

What Jen is unaware of is the impact of one of the foundations of mindfulness training: non-judgemental observation of the interplay between her thoughts, emotions and physiology. Her thoughts are triggering emotions, which are triggering a bodily response. Her bodily response (which she is largely unaware of) is having a tangible impact on her thoughts and decisions. Although she thinks that she’s fully rational and in control when making decisions, in reality her emotions are also impacting on her thoughts. If Jen was practising mindfulness, she’d be much more aware of what’s going on, and able to choose alternative strategies that were better for her well-being and that may lead to wiser decisions.

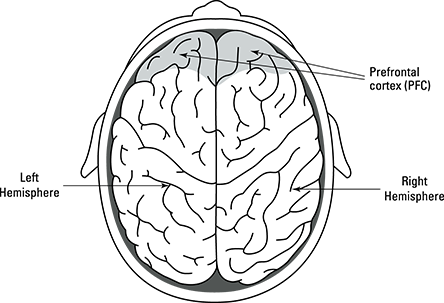

Despite the fact that Jen is an experienced leader, calm, organised and highly intelligent, her primitive brain has detected a possible threat to her social and professional status. Status – your place in the pecking order – is important to humans. Jen’s amygdala (part of the limbic system in her primitive brain) triggers a fight or flight response. Her primitive brain is now in charge. Hijacked by emotions, her higher brain becomes helpless. In an attempt to keep her safe from harm, her primitive brain hijacks the driver’s seat and she is reduced to being a passenger sitting in the back seat, hanging on for dear life. Jen is in this position because her primitive brain switches off her higher brain, including the prefrontal cortex (PFC), shown in Figure 1-3. This vital part of your brain plays a huge role in decision making. The prefrontal cortex allows you to plan ahead and create strategies, pay attention, learn and focus on goals.

Figure 1-3: Image of the brain showing the prefrontal cortex.

When finding out about mindfulness, you discover the interplay between your primitive brain’s desire to keep you safe from harm, and the impact of your sympathetic nervous system (which mobilises your parasympathetic fight-or-flight response) on both your body and ability to think clearly.

At times like this, Jen would benefit from a mindfulness exercise. She should focus her full attention on taking slow, deep breaths for a few minutes. Focusing her attention fully on the sensation of breathing will slow down or stop her mental chatter, which in turn will reduce the feeling of threat and trigger a lessening of her fight-or-flight response. In addition, her brain’s PFC will get the oxygen it needs to regain control, and her primitive brain will hand back control to her PFC.

Of course, the rational PFC can’t always prevent the primitive brain from engaging. This inability is because the primitive brain is more evolved and responds much more quickly than the highly powerful, but slower, less-evolved higher brain. Mindfulness does not stop your rational higher brain from getting hijacked by your primitive brain, but it does make you much more aware of what’s going on, much earlier. This awareness gives you choices in how to respond. You won’t be forced to unconsciously default to primitive brain auto-pilot responses and actions. You have a choice!

Now, we need to look at other elements of the brain that impact on Jen’s work and explore how mindfulness could be beneficial.

At times Jen feels as if she’s hitting a brick wall when she’s trying to find new solutions to old problems. When under pressure, defaulting to well-used, comfortable ways of doing things stored in the primitive brain is all too easy. Giving ‘stock’ answers to questions may result. Mindfulness teaches you the benefits of taking time out to calm your mind and centre yourself. Doing so can take as little as three minutes and can produce dramatic results. Allowing the brain to relax and let go of its frantic activity to solve the problem can deactivate the primitive brain’s grip, and allow the higher brain to apply creativity and innovation to the problem.

Jen often multi-tasks, flitting from one project to another and juggling project work with phone calls and emails as they arise. She often finds herself becoming tired and having difficulty concentrating. The ability to multi-task is a myth. Many research studies show that regular multi-taskers get less done than those who focus on one thing at a time – even the people that think they’re good at mulit-tasking. Multi-tasking actually means that the brain is switching backwards and forwards from task to task, which wastes a huge amount of valuable energy, and details are invariably lost with each switch. No wonder that Jen feels tired! She’s making her life much harder than it needs to be.

Mindfulness shows you how to mentally stand back and observe what’s going on around you and in your brain. It also helps you to develop different approaches to life that are kinder to you and usually more productive. Mindfulness helps you observe and reduce the mental chatter that distracts you from your work, allowing you to focus on it more fully. By intentionally taking steps to recognise and avoid distractions and focusing your full attention on one task at a time, you can get things done more quickly, with fewer mistakes and less repetition. Using mindfulness techniques when you feel your attention waning can help you to restart work feeling refreshed and focused.

Mindfulness can also be useful in high-level meetings when emotions can sometimes be charged. Training in mindfulness would help Jen to observe the dynamics at play in such meetings more clearly. She’d probably recognise that in this situation people are commonly motivated by the need to avoid potential threat (to status and social standing) and are unlikely to approach the task with an open mind and look for the best possible solution. Jen would also be aware of the two possible states of mind that people could be operating in. In avoidance mode, people are motivated by the desire to avoid something happening. With their threat system activated, they may fail to see the bigger picture, be less able to think clearly and be less creative in their ideas and solutions. Avoidance mode tends to be associated with increased activation of the right PFC. Excessive right PFC activation is associated with depression and anxiety. Mindfulness cultivates an approach state of mind. Often the effort taken to avoid something happening is disproportionate to dealing with the thing you seek to avoid. An approach mode of mind is associated with increased left brain PFC activation, which is connected with positivity and an upbeat approach to life. In approach mode, you’re able to explore new possibilities and opportunities with an open mind.

When working in avoidance mode, cognitive thinking resources are diminished, making it harder to think and work things through. You’re also likely to feel less positive and engaged. If Jen applied mindfulness to her work life, she’d be able to better manage her own emotions and subtly take steps to help reduce the sense of threat often permeating business meetings.

The brain can have a significant impact on how you work. Finding out about and practising mindfulness gives you the tools you need to harness this knowledge to manage your mind better.

Starting Your Mindful Journey

Congratulations! The fact that you’ve picked up this book and started reading it means that you’ve already started your mindful journey. The chapters in this book describe lots of ways to learn mindfulness, one of which is sure to suit your learning style and fit in with your busy life. You’ll also discover that mindfulness involves much more than sitting down and focusing on your breath. In this book, you should find a number of mindfulness techniques that work for you.

A good book is a great starting point, but nothing can replace experiencing mindfulness for yourself. As with learning anything new, you may find it difficult to know where to start. Learning mindfulness from an experienced teacher who can help you to overcome obstacles and guide your development is advisable. The idea behind this book is to demonstrate how and why mindfulness can benefit you at work, and provide suggestions of how to apply simple mindfulness techniques to everyday work challenges.

Being mindful at work yourself

Getting caught up in the manic pace of everyday work life is common. You, like many workers, may feel under pressure to deliver more with fewer resources. You may also be keen to demonstrate what an asset you are to your company by working longer and longer hours, and being contactable round the clock.

Being mindful at work can involve as little or as much change as you’re able to accommodate at this moment in time. At one end of the scale, you may simply apply knowledge of how the brain works and some mindful principles to your work. To gain maximum benefit, you need to practise mindfulness regularly and apply quick mindfulness techniques in the workplace when you need to regain focus or encounter difficulties. The choice is yours! The benefits you gain increase in line with the effort you put in. You should see a real difference after practising mindfulness for as little as ten minutes a day for about six weeks.

At times, being mindful at work can involve an act of bravery – swimming against the tide by doing things differently. If the way you’re currently working is leading to stress, anxiety, tiredness or exhaustion, then maybe you need to try something different. If you’re tasked with being innovative and finding new ways of doing things, what makes you think that carrying on as you’ve always done will make this creativity possible? As this book constantly reiterates, humans dislike uncertainty and crave certainty. Defaulting to doing things as you’ve always done them is always easier, especially if they’ve become stored as habits in the primitive brain and can be repeated with little or no conscious thought.

As you discover in Chapter 7, changing habits takes time and effort. For this reason, most mindfulness courses are taught weekly, over a five- to eight-week period. Each week you learn something new, practise it for a week and then build new knowledge onto it the following week. When first learning to be mindful, most people find it easier to practise at home than at work. Practising at home is simpler because controlling noise and disturbances at home is obviously easier.

Following these initial practice sessions, most people then introduce a few short mindfulness techniques at work. Over time, as mindfulness becomes second nature to you, you’ll develop the ability to practise wherever and whenever the opportunity arises. As your confidence builds and you apply mindfulness to your work further, others will probably notice changes in you. You may appear calmer, more poised and better focused. Possibly your work relationships have improved. If you’re lucky enough to be offered mindfulness sessions in work time, don’t be surprised if people are curious, and ask you for tips and techniques to try out for themselves. Organisations that offer mindfulness classes often have a long waiting list of staff eager to attend.

Overcoming common challenges

Probably the most common challenges you face when learning mindfulness are: concerns about what others think; finding the right time and place to practise; and breaking down habits and mindsets in order to do things differently.

You now need to address each of these challenges in turn.

Dealing with concerns about what others think

In the past mindfulness was often associated with Buddhism, spirituality and new age ideas. This association was compounded by the fact that mindfulness was often only taught in Buddhist centres or local village halls. And, although MBSR had existed for over 40 years, and MBCT and ACT for about 20, they were only used in clinical settings and the general public was unaware of them. In addition, the media often confused mindfulness with other forms of meditation. Articles about mindfulness were often accompanied by pictures of people sitting cross-legged in the lotus position, their hands in prayer. This misleading image was almost certainly one of the reasons behind professionals’ reluctance to ‘come out of the mindfulness closet’.

In recent years, mindfulness has been discussed in the White House and 10 Downing Street. Mindfulness has been sampled at the World Economic Forum and is taught by major business schools. The press now feature mindfulness on a regular basis, and the pictures that accompany the articles are slowly becoming more representative of real-life mindfulness practice! As a result, more and more people are giving mindfulness a try, and integrating it into their work day.

Finding the right time and place to practise

If you’re lucky enough to be offered mindfulness training by your organisation, you quickly discover that mindfulness is unlike any other courses you’ve attended. Unlike most courses that employers routinely offer to staff, simply attending isn’t enough. Classes help you understand the principles that underpin mindfulness and how mindfulness techniques work. They also provide you with a safe environment and guidance to try out different mindfulness techniques. However, the real learning usually happens outside work, as you practise it. You can’t get fit without exercising, can you? The same applies to mindfulness. Think of mindfulness as a good work out for your brain; the more you practise, the easier it becomes.

On a typical workplace mindfulness course, you’re taught a different technique each week, which you need to practise for at least six days before moving on to the next one. This process can prove to be one of the most challenging aspects of learning mindfulness. For many busy workers, their entire day is scheduled, and sometimes extends into their home life. With a mindset of ‘so much to do and so little time’, even finding 15 minutes a day can feel daunting. The question to ask yourself is, ‘Why am I doing this?’ For many people, the answer is ‘because I cannot continue working in the way I do’. If this is your reply, re-arranging your life to make time for mindfulness is certainly worthwhile. Try not to think about mindfulness as just another thing that needs to be fitted into your busy life; rather, view it as a new way to live your life. Think of the time you spend practising mindfulness as ‘me time’ – after all, this time is one of the rare moments in which you have nothing to do but focus on yourself. Chapters 6 and 7 take you through a five-week mindfulness at work course to try at home.

Breaking down habits and mindsets in order to do things differently

Habits are formed when you repeat the same thoughts or behaviours many times. Habits are highly efficient from a brain perspective because they’re stored in the primitive brain, which can repeat them quickly without any conscious thought, using very little energy.

Learning mindfulness may take effort, especially if you start to challenge your habits and patterns of thinking. Make sure that you remember that, just as it takes time to form habits, so it takes time to replace old habits with different ways of thinking and being. With a little time and perseverance you can find new ways of working that are more productive and better for your health and sense of well-being.

Creating a mindful workplace

Every great journey starts with just one step. A young single mother of three I (Juliet) know was once given the opportunity to climb Mount Everest. Three-quarters of the way up the mountain she became exhausted, felt overwhelmed by the whole journey and declared that she could go no further. The trek leader calmly stood in front of her and asked whether she could see his footsteps in the snow ahead. She nodded in agreement. He told her that all she needed to do was put one foot in front of another, following his footsteps. By focusing on the present moment action of her feet, she was able to avoid worrying about the remainder of the journey. She made it to the summit – one of the greatest achievements of her life.

Getting caught up in planning the journey ahead is common and at times you may feel overwhelmed by all the things you need to do and think about. When finding out about and practising mindfulness for the first time, focus only on the next footstep, rather than the journey as a whole, is often the best approach. Try to let your mindful journey unfold, day by day, moment by moment. If you truly want your organisation to become more mindful, you need to start by focusing on yourself. As you gain a deeper understanding of what mindfulness is, and start to experiment with integrating mindfulness into your life and work, you discover for yourself what works and what doesn’t. Only then are you equipped to make a real difference to your organisation. The building blocks of a mindful organisation are mindful employees who start to transform their organisations one step at a time. Chapter 15 deals with mindful organisations.

Living the dream: Mindfulness at work

Sometimes the hardest part of a journey is taking the first step. In this book, you can find a wealth of information about mindfulness. You also discover mindful techniques for different situations that you may encounter at work and for different occupations (see Chapter 10).

The potential of mindfulness to transform the way you work and live your life is immense. The extent to which you benefit from it is entirely up to you and the effort that you’re able to put into it.

- A is for awareness – becoming more aware of what you’re thinking and doing and what’s going on in your mind and body.

- B is for ‘just being’ with your experiences – avoiding the tendency to respond on auto-pilot and feed problems by creating your own story.

- C is for choice – by seeing things as they are you can choose to respond more wisely – by creating a gap between an experience and your reaction you can step out pilot which opens up a world of new possibilities.

As with all new skills, the more you practise mindfulness, the easier it becomes. Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb coined the phrase ‘neurones that fire together, wire together’. In other words, the more you practise mindfulness, the more you develop the neural pathways in the brain associated with being mindful.

When discovering how to become more mindful, remember ABC:

When discovering how to become more mindful, remember ABC: