CHAPTER 1

THE SERVICE AND RELATIONSHIP IMPERATIVE: MANAGING IN SERVICE COMPETITION

“Everyone faces service competition. By providing service, firms make themselves meaningful for their customers.”

INTRODUCTION

In this introductory chapter the logic of service as a business perspective and the relationship between service and customer interactions are discussed, and the concept of service competition is introduced. Service as a strategy in comparison with other strategic approaches is considered in detail. Strategic and tactical implications of a service strategy and of a relationship approach to customers are outlined. The concept of service logic and its implications for the value generation process and value co-creation are then presented. Further, the meaning of a customer relationship approach and a number of aspects of customer relationships are discussed. Finally, some central aspects of the book are presented as guidelines for the reader. After having read this chapter the reader should understand the logic of service and the characteristics of a service strategy, and know which strategic and tactical implications follow from such a strategy. It should also be clear how value evolves for customers as value-in-use and what roles the firm and customer have in the value process.

ONCE UPON A TIME: A CASE OF SERVICE AND CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS

In a village in ancient China there was a young rice merchant, Ming Hua.1 He was one of six rice merchants in that village. He was sitting in his store waiting for customers, but business was not good.

One day Ming Hua realized that he had to think more about the villagers, what they were doing, their needs and desires, and not just distribute rice to those who came into his store. He understood that he had to provide the villagers with something that was more valuable for them, and something different, from what other merchants offered. He decided to develop a record of his customers’ eating habits and ordering periods and to start delivering rice to them. To begin with Ming Hua walked around the village and knocked on the doors of his customers’ houses asking:

• how many members there were in the household;

• how many bowls of rice they cooked on any given day; and

• the size of the rice jar in the household.

Then he offered every customer:

• free home delivery; and

• a service to replenish the household’s rice jar automatically at regular intervals.

For example, in one household with four persons, every person would consume on average two bowls of rice a day, and therefore the household would need eight bowls of rice every day for their meals. From his records Ming Hua could see that the rice jar of that particular household contained rice for 60 bowls, or approximately one bag of rice, and that a full jar would last for 15 days. Consequently, he offered to deliver a bag of rice every 15 days to this house.

By establishing these records and developing this new service, Ming Hua managed to create more extensive and deeper relationships with the villagers; first with his old customers, then gradually with other villagers. Eventually the size of his business increased and he had to employ more people: one person to keep records of customers, one to take care of book-keeping, one to sell over the counter in the store, and two to take care of deliveries. Ming Hua spent his time visiting villagers and handling contacts with his suppliers, a limited number of rice farmers whom he knew well. Meanwhile his business prospered.

THE NATURE OF SERVICE AND CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIPS

The story of Ming Hua, the rice merchant, demonstrates significant aspects of a service perspective on business, and includes all basic elements of a relationship approach to customers. Key aspects of service are:

• Service is support for customers’ individual processes in a way that facilitates their value creation,2 and this support is enabled when knowledge and skills are used on resources.3

• The ultimate goal of service-based business is to facilitate value creation for the customer, which in return enables the service provider to capture value from the relationship,4 with service as a mediator.

• Service is a process, where the service provider’s resources and the customer often interact to some extent.

• To become a service provider, the resources of the firm’s offering can be of any kind, such as physical goods (e.g. rice), service activities (services), information, or combinations of these and other types of resources.

Key relationship-based characteristics are:5

• The service provider and customer engage in long-term business contact.

• The relationship requires that the service provider gains insight into the customer’s everyday processes.

• The goal of the relationship is mutual value creation, i.e. a win–win situation.

As demonstrated, Ming Hua created a process for supporting the villagers’ cooking, which made their cooking process easier and acquiring rice more convenient, thus increasing value in their life. At the same time, the rice merchant’s business improved, i.e. he managed to capture more value than before from serving the villagers. For this to take place, he had to gain enough knowledge about the villagers’ cooking habits and cooking equipment, such as the size of each family and their rice bowls and jars. Once he had this insight, he could develop long-term contact with the villagers and engage them with his new service process. Finally, this arrangement became a win–win situation for both parties.

The story about the rice merchant, shows how, through what today would be called a relationship marketing strategy, he changed his role from a transaction-oriented channel member to a service-providing, value-supporting relationship manager. In that way he created a competitive advantage over rivals who continued to pursue a traditional strategy. Three important strategic requirements of a relationship strategy can distinguished:6

Redefine the business as a service business and the key competitive element as service competition (competing with service and a total service offering, not just the sale of rice alone).

Look at the organization from a process management perspective and not from a functionalistic perspective (to manage the process of supporting and facilitating value creation for the villagers, not only to distribute rice).

Establish partnerships and a network to handle the whole service process (close contacts with well-known rice farmers).

As can be seen from the story, three tactical elements of a relationship strategy are included:7

Seek direct contacts with customers and other business partners (such as rice farmers).

Build a database covering necessary information about customers and others.

Develop a customer-centric service system.

The three strategic requirements set the strategic base for the successful management of relationships. The three tactical elements are required to successfully provide service and implement customer management.

Later on in this chapter, strategic requirements and then the tactical elements will be discussed in some detail. However, using Ming Hua’s new service-based relational business as an example, an analysis of the commercial focus of service providers and product distributors will first be made and discussed.

A COMMERCIAL ANALYSIS: FROM PRODUCT-FOCUSED TO SERVICE-FOCUSED MANAGEMENT

A first customer satisfaction-based analysis of a service strategy, Ming Hua’s tale, clearly shows that the customers were satisfied, the customer base grew, and the business prospered. However, a customer satisfaction analysis is not enough to understand the effect of a service approach and the implementation of a service strategy. We also have to do a commercial analysis. Basically, the commercial outcome of a business can be described with three elements, namely revenues, costs and capital. A firm’s profitability is a function of all three elements, whereas the profit level is a function of the revenue generation capability and the cost level. Finally, the revenue generation capability is dependent on how well the firm understands its customers and their processes, and how well it manages to gear its resources, such as skills and knowledge, technologies, systems, products and service activities, towards supporting its customers’ processes and goals in life (consumer markets) or business (business-to-business markets). In the continued analysis, we exclude the influence of capital, and analyse the impact on the profit equation of various management approaches.

In Chapter 3 on the service profit logic and service management principles, the profit logic in service is analysed in detail. At this point we only note that a service provider’s revenue generation capability is not only dependent on sales and traditional marketing of a more or less standardized product. Because the customer interface is much broader than that, the customers’ interest in paying for the firm’s service is influenced by a whole host of other activities and processes managed by the service provider. For example, in the rice merchant’s story, selling rice is not enough for the new service strategy to succeed; the rice delivery system supported by the customer information system as a service process is the most important reason why customers wanted to buy from Ming Hua.

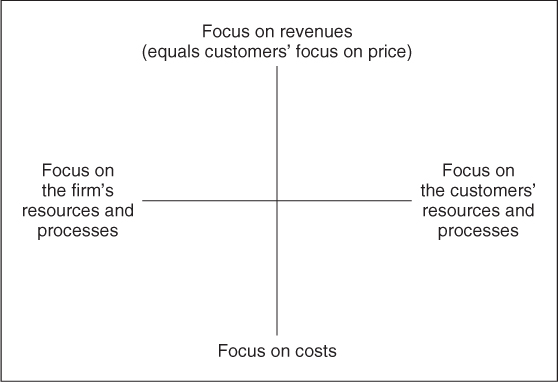

For understanding the business from a commercial point of view, therefore, two variables are enough, namely the profit variable and the process variable. A chart for analysing the business from a commercial perspective based on these two variables is illustrated in Figure 1.1, with the profit variable as the vertical scale and the process variable as the horizontal scale.

The end points of the profit and resource variables, respectively, are the following:

• Dominating focus on revenues and revenue generation, or dominating focus on costs.

• Dominating focus on the firm’s resources and processes, or dominating focus on the customers’ resources and processes.

It is important to realize the customers’ focus is always, with few exceptions, in the upper right quadrant of Figure 1.1, ‘focus on revenues (and revenue generation)/focus on the customers’ resources and processes’. The reason for this is simple. Customers are interested in the price they are requested to pay for a solution, and of course also in their own processes which they want to have supported: for example, in what life or business processes are they involved and what do they wish to achieve, what skills and knowledge to make use of a solution offered to them do they hold and what complementary resources required to make use of the solution offered do they have access to? Hence, a firm’s customers are always interested in the firm’s revenues and revenue generation capability. It is ironic that far too often firms are more interested in their cost level and in focusing on cost efficiency, and consequently, a clash with the customers’ interests occurs.

Frequently, another clash between firms and their customers also happens. The customers are, of course, more or less only interested in their own resources and processes. Firms, on the other hand, are often predominantly focused on their own resources and processes, and gather only too-superficial market research data about their customers, but limited insight into the customers’ processes, goals, and thoughts which steer their buying and usage/consumption behaviour.

FIGURE 1.1

Chart for analysing commercial focus.

If these conflicts occur, a firm – its management and the whole organization – is mentally positioned in the lower left quadrant of Figure 1.1, whereas its customers are mentally positioned in the upper right quadrant. First of all, it is a mental positioning, which reflects, respectively, the dominating thoughts and dominating focus of interest of a firm and its management, and of the customers. However, this mental focus influences how the firm is managed and how its processes are implemented, and it reflects the customers’ buying behaviour as well.

SERVICE MANAGEMENT REQUIRES AN OUTSIDE-IN MANAGEMENT APPROACH

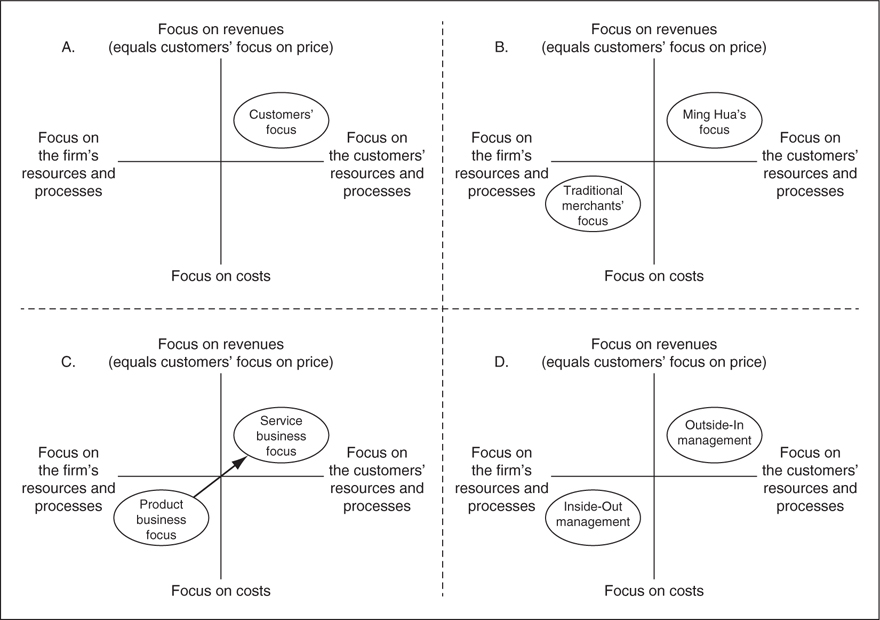

In the four parts of Figure 1.2, various positions of firms in the commercial analysis chart of Figure 1.1 are depicted, depending on their mental managerial and operational foci. In the upper left corner of Figure 1.2 (Part A) customers’ typical mental focus is positioned in the upper left quadrant, with a dominating interest in their own resources and processes as well as in the price they are required to pay, and therefore also, indirectly, in the firm’s revenue generating capability.

In Part B of the figure, in the upper right corner, the different mental foci and the corresponding business approach of the rice merchants in the village are illustrated, as examples of typical firms’ positions. The focus of the traditional merchants is in the lower left quadrant, where the businessis based on an interest in the firm’s own resources (rice) and processes (rice-selling shops), and a focus on the costs of running the business is dominatant, i.e. the business is based on selling the product (rice). Ming Hua, however, moved his focus towards the upper right quadrant by turning to a strategy of developing relationships with his customers and providing service to them. Doing this required a shift of interest from his old processes of selling rice from a shop to understanding the customers’ relevant processes and resources, such as their cooking routines and sizes of rice cups and jars. Based on this customer insight, he adjusted his own processes from selling rice from a shop to servicing the customers by delivering rice to their homes according to a customized schedule, and to creating a network of rice farmers to make sure that he had products to deliver. To make his business prosper, which it did, he of course also had to adjust his cost level to the revenue generation capability of the new service strategy.

FIGURE 1.2

From product-focused inside-out management to service-focused outside-in management.

In the lower left corner of Figure 1.2 (Part C) the two strategies described above are summarized. If, as illustrated by the lower left quadrant of Part C, management’s and the organization’s mental focus is dominated by an interest in the firm’s own resources (e.g. technologies and products) and processes, and by an overwhelming concern for costs and cost efficiency, the firm’s business approach will be driven by its resources, and overly focused on delivering such resources to its customers. This can be characterized as a product business focus, regardless of whether the core of the offering is a physical good or a service activity, such as rice or, say, transportation. In the upper right quadrant of Part C, a service business focus is positioned. Such a business approach is characterized by a dominating focus on gaining in-depth insight into the customers’ processes and resources (e.g. skills, capabilities and access to complementary resources) and on how revenues are generated for the firm.

Firms are often mentally in the lower left quadrant and take a product business focus. This applies equally to so-called service firms, such as banks, insurance companies, airlines and those in hospitality industries, and organizations in the public sector, and to goods manufacturers. It is not the core of the offering that determines what kind of business a firm is conducting; it is the mental focus of management and the organization that counts. A firm that wants to move towards adopting a service strategy and pursuing a service perspective in its business performance must follow the black arrow in Part C of the figure, and change its mental focus and corresponding behaviour accordingly. In this way any firm, regardless of its business or industry, can transform itself into a service business.

Finally, in Part D of Figure 1.2, in the lower right corner, the underpinning logic of, respectively, a product business and a service business is characterized. A service business logic is basically grounded in a dominating interest in thoroughly understanding the processes and resources of the firm’s customers, and in its revenue generation capabilities. Of course, this does not mean that a focus on the firm’s own resources and processes and on cost efficiency would be less important than otherwise. In absolute terms they are equally important as before but, relatively speaking, focus on the customer and revenues is more important. Hence, service business management can be characterized as outside-in management. In contrast, product business management with its dominating interest in issues internal to the firm, such as the firm’s resources, processes and costs, can be characterized as inside-out management.

In conclusion, service management requires a mental focus on customers and revenues, and an outside-in management approach. In Table 1.1 fundamental differences between a service-focused outside-in management approach and a product-focused inside-out approach are summarized.

In view of the preceding discussion, the two first rows of the table – core competence and core process – are self-explanatory. However, the two sales-related issues require some clarification. In conventional product selling based on an inside-out approach, the technical specifications qualify the offering. However, as there often are several competitors offering similar technical solutions, price becomes the distinguishing sales argument. In service selling, regardless of whether the core of the offering is a physical good or a service concept, the aim of the total offering is to provide value-creating support for the customers’ processes and thereby contribute to their goal achievement. Hence, the offering’s value-creating support becomes the qualifying characteristic. As price is only one element of customer value (this is developed further in Chapter 6 on return on service and relationships), other sacrifice-related or revenue-related elements may well compensate for a high price. For example, an unattractive price can be balanced by lower operational and/or administrative costs in the long run, and also by the prospect of growing sales and/or increasing revenues. Therefore, long-term value is the determinant sales argument.

Fundamental differences between outside-in and inside-out management.

Outside-in management |

Inside-out management |

|

Core competence |

Understanding customers’ everyday processes and how they affect their life/business goals. |

Understanding technology, products and production processes. |

Core process |

Providing value-creating support to the customers’ everyday processes, which contributes to their life/business goals. |

Production of goods and/or services. |

Major sales pitch |

Value-creating support. |

Product (goods or services) specifications. |

Determining sales argument |

Long-term value for customers relating to their life/business goals. |

Price. |

In the following sections, the strategic and tactical requirements of a service strategy based on customer relationships referred to above will be discussed in some detail. The three strategic requirements – redefining the firm as service business, taking a process management perspective, and developing partnerships and networks – set the strategic base for the successful management of relationships. The three tactical elements – seeking direct contacts with customers, building customer insight, and developing a customer-focused service system – are required to successfully implement customer management.

DEFINING THE FIRM AS A SERVICE BUSINESS

A key requirement in a service and relationship strategy is that a manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, service firm or supplier has a thorough insight into the customers’ everyday processes, and into the relationship between them and the customers’ life or business processes, and the long-term needs and desires of their customers. Another requirement is that value-supporting service is offered based on the technical solutions imbedded in consumer goods and industrial equipment, or in service activities. The core of a service firm’s offering is by definition a service activity, but if it takes an inside-out management approach, such a firm may nevertheless operate as a product business.

The service approach to customers applies to any type of firm, and if they choose to do it, any firm – so-called service firms and goods manufacturers alike – can adopt a service strategy. Customers do not only look for goods or services, they demand a much more holistic service offering, including everything from information about how best to use a product, to delivering, installing, updating, repairing, maintaining and correcting solutions they have bought. Moreover, they demand all this, and much more, to be delivered in a friendly, trustworthy and timely manner.

In a customer relationship that goes beyond a single transaction of goods or services, the product itself as a technical solution involving goods, service activities or industrial equipment becomes just one element in the holistic ongoing service to the customers. For a goods manufacturing firm, the physical good is a core element of the service offering, because it is a prerequisite for a successful service. For a service firm it is the service concept. In today’s competitive situation this core is very seldom sufficient to produce successful results and a lasting position in the marketplace. What counts is the ability of the firm, regardless of its position in the distribution channel, to manage the additional elements of the offering better than its competitors. Moreover, the core physical product or service concept is less often the reason for dissatisfaction than the elements surrounding the core. For example, when buying a car, the car is seldom the reason for customer dissatisfaction; the after-sales service is the main reason. Or in a restaurant, the meal may be good but poor service is the reason for dissatisfaction. In other words, competing with the core product or service concept is not enough; competing with the total offering, where the core of the offering is only one element of a total service offering, is what counts. The transition from the product or service concept as the dominating element of the offering to management of human resources, technology, knowledge and time in order for the firm to create successful market offerings is evident.

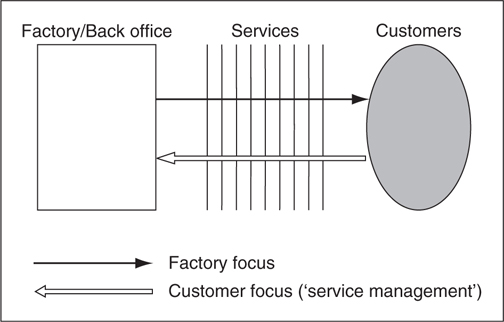

In Figure 1.3 the thick black arrow from the factory or back office of a service firm out towards the customer demonstrates the traditional product-oriented approach, where the factory (and the management of what takes place in the factory) is considered the key to success in the marketplace. For a manufacturing firm, services are considered add-ons to the factory output. In service firms interactions in the service process are often considered less important to the customer than what is produced in the back office. This management approach is based on a factory or back office focus. Although this approach to management may have been highly successful in the past, it does not reflect the current competitive situation, where a new management perspective is needed. As indicated by the second arrow in the figure, from the customer towards the factory or back office, the various service elements of the firm are the first elements of the output of the firm that the customer encounters and experiences. These service processes support the customer’s perception of value, whereas the factory or back office output is only a prerequisite for value.

FIGURE 1.3

A customer focus: the firm as a service business.

Source: Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing logic. Asia–Australia Marketing Journal, 4(1); 1996: p. 13. Reproduced by the permission of the ANZMAC (The Australasia and New Zealand Marketing Academy).

A growing number of industries, manufacturers and service firms now face a competitive situation for which we have coined the term service competition. They have to understand the nature of service management as a management approach geared to the demands of the new competitive situation. The solution to customer problems seen as a total service offering thus becomes service, and this total offering becomes service provision, instead of mere delivery of a physical product or a service. When service competition is the key to success for everybody, the firm has to offer service, irrespective of its traditional business, and consequently every business is a service business.

A PROCESS MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE

An ongoing relationship with customers, where customers look for value support by the total service offering, requires internal collaboration among departments that are responsible for different elements of the offering, such as the core product (goods or services), advertising the product, delivering the product, taking care of complaints and rectifying mistakes and quality faults, maintaining the product, billing routines, product documentation, etc. The whole chain of activities has to be co-ordinated and managed as a total process. Moreover, from profitability and productivity perspectives only activities that support value for customers should be carried out. Other resources and activities should be excluded from the process. In a traditional functionalistic organizational setting this cannot be achieved. Therefore, a service and relationship approach to customers requires a process management approach.

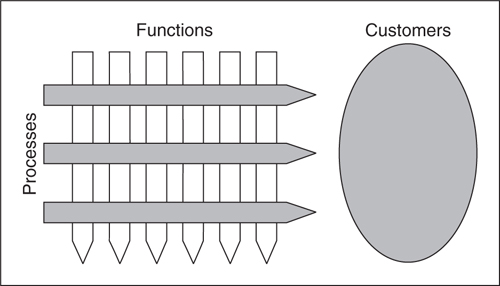

FIGURE 1.4

A process focus: the firm as a value-generating operation.

Source: Grönroos, C., Relationship marketing logic. Asia–Australia Marketing Journal, 4(1); 1996: p. 14.

Reproduced by permission of the ANZMAC (The Australasia and New Zealand Marketing Academy).

A process management perspective is very different from the functionalistic management approach. A functionalistic organization allows for sub-optimization, because every activity and corresponding department within a company is more oriented towards specialization within departments than collaboration between them. As indicated in Figure 1.4, the various departments do not necessarily direct their efforts towards the demands and expectations of the customers. This does not necessarily support customers’ total requirements. Customers do not look for a combination of sub-optimized outputs of different departments of a firm that is not supporting total value for them. For example, an outstanding technical solution and a cost-effective transportation system may be optimal from the supplier’s point of view, but for the customer it is often equivalent to an unreliable supplier. An unreliable supplier equals low value for the customer.

Project and task force organizations are first attempts to break free from the strait-jacket of a functionalistic organization, so that the various departments are geared towards working according to the horizontal arrows in the figure. However, in order to be able to create maximum total value in a coordinated relationship with customers, the firm should strive to go further. A process management approach should be taken. In such an approach traditional departmental boundaries are torn down and the workflow (including, for example, traditional sales and marketing activities, production, logistics, general administration and distribution activities with a host of customer contact activities involved) is organized and managed as a value-supporting process that enables and strengthens relationship-building and management.

PARTNERSHIPS AND NETWORKS

A service and relationship approach to customers is based on cooperation. Service providers and customers will not view each other from a win–lose perspective but will rather benefit from a win–win situation, where the parties involved will be best off as partners. Furthermore, frequently manufacturing and service firms will find that they cannot by themselves supply customers with a total offering needed, and that it is too expensive to acquire the necessary additional knowledge and resources to produce the required elements of the offering themselves. Hence, it may be more effective and profitable to find a partner who can offer the complementary elements of the offering needed to develop a successful relationship with a customer. Partnerships and networks of firms are formed horizontally and vertically in the distribution channel and in the supply chain. Although firms compete with each other, they may sometimes find it effective and profitable to collaborate in some areas to serve mutual customers. This of course demands the existence of one key ingredient of relationship marketing; trust between the parties in a network. Otherwise they will not feel committed to the mutual cause.

The next sections turn to the tactical elements of relationship marketing.

SEEKING DIRECT CONTACTS WITH CUSTOMERS

A service and relationship approach to customers is based on a notion of trusting cooperation between the business partners. Hence, firms have to get to know their customers much better than has normally been the case. In an extreme situation, which is quite possible in many consumer service markets such as household insurance and industrial markets such as merchant banking and industrial equipment provision, a firm can treat each customer individually. At the other extreme of consumer goods and mass markets, customers cannot be identified in the same way. However, the manufacturer or retailer should develop systems that provide them with as much insight about their customers’ processes and behaviours as possible so that, for example, advertising campaigns, sales contacts and every interaction with customers can be made as relationship-oriented as possible. Modern information technology provides the firm with ample opportunities to develop ways of showing a customer that he is known and valued. Also, traditional advertising campaigns become too expensive and ineffective if they are not directed towards customers so that a dialogue can be initiated. One-way market communication costs too much and produces too little.

Regardless of how close a firm can get to the situation of knowing and treating customers as individuals, one should always use face-to-face contacts with customers or means provided by information technology to get as close as possible to customers. In every face-to-face service encounter, regardless of whether there is a mass market of customers or not, the firm interacts with each customer as an individual and should treat the customer as an individual and not as a member of a mass. In addition, each such encounter is a source of insight into the customer’s processes, thoughts, needs, wishes and values. This is a source of customer information which most often is unused.

DEVELOPING A CUSTOMER DATABASE

Traditionally, marketing operates with limited and incomplete information about customers. In order to pursue a relationship marketing strategy, a firm cannot let such ignorance last. A customer information database must be established, which can be turned into actionable knowledge about the customers. If such a database does not exist, customer contacts will only be handled partially in a relationship-oriented manner. If the person involved in a particular interaction with a customer has first-hand information about the customer and knows the person he is in contact with, the interaction may go well. However, in many situations – for example, employees who answer customers’ phone calls, meet customers at a reception desk or make maintenance calls – they will not personally know the customer. A well-prepared, updated, easily retrievable and easy-to-read customer information file is needed in such cases to make it possible for the employee to pursue a relationship-oriented customer contact. In addition, a good database will be an effective support for cross-sales and new product offerings.

In addition to their primary use to maintain customer relationships, databases can be used for a variety of marketing activities, such as segmenting the customer base, tailoring marketing activities, generating profiles of customer types, supporting service activities and identifying likely purchasers.

A customer information database should also include profitability information, so that one knows the long-term profitability of customers in the database. If such long-term profitability information is lacking, the firm may easily include segments of unprofitable customers in its customer base.

CREATING A CUSTOMER-ORIENTED SERVICE SYSTEM

Successful customer management demands that the firm defines its business as a service business and understands how to create and manage a total service offering, i.e. it adopts a service strategy. The organization’s processes thus have to be designed to make it possible to serve customers and produce and deliver a total service offering. In other words, the firm has to know and practise service management. The philosophy and principles of service management are in many respects different from those of a traditional management philosophy. In Chapter 3 we will discuss such differences. Four types of resources are central to the development of a successful service system: customers, technology, employees and time.

Customers take a much more active role than they normally do. The perceived quality of the service offering partly depends on the impact of the customer. The service system is increasingly built upon technology. Computerized systems and information technology used in design, production, administration, service and maintenance have to be designed from a customer-oriented perspective, and not only from internal production and productivity-oriented viewpoints. The success of relationship marketing is highly dependent on the attitudes, commitment and performance of the employees. If they are not committed to their role as true service employees and are not motivated to perform in a customer-oriented fashion, the strategy fails. Hence, success in the external marketplace requires success internally in motivating employees and making them committed to the pursuit of a relationship marketing strategy. Marketing based on a service and relationship strategy is, therefore, highly dependent on a well-organized and continuous internal marketing process. Internal marketing will be discussed in some detail in Chapter 14. Time is also a critical resource. Customers have to feel that the time they spend on their relationship with a supplier or service firm is not wasted. Badly managed time creates extra costs for all parties in a relationship.

CUSTOMER VALUE AND VALUE CREATION

Value is an elusive concept, and it has been approached and defined in many different ways. In some situations, especially but not only in business-to-business markets, it can be measured in monetary terms. In other contexts, mostly in consumer markets, value is merely a perception. However, even when value is calculated in monetary terms, there is often this element to it, for example perceived ease of doing business with a firm, or trust in a firm. A value perception can be based on experiences with a service provider in a variety of different ways.8 Here we do not go into the various ways value can be calculated or perceived. Instead we define value in a simple but practical way as ‘being better off’. More value means that a customer, after having been supported by a service provider, is or feels better off than before.9 What ‘better off’ means in any given situation must be analysed and, if possible, calculated. In Chapter 6, Return on service and relationships, how to calculate value for both a customer and the service provider is discussed and appropriate metrics presented. It should be observed that a customer does not always have positive experiences, and sometimes the customer may also be ‘worse off’, which means that value deterioration has taken place, at least temporarily.

Service management requires a customer-focused outside-in approach. Value for customers, and the service provider’s capability to support its customers’ processes in a way that enables the customers to create value and achieve their goals, are key aspects of outside-in service management. In marketing, value for customers has for decades been considered a key aspect of service management,10 which has been re-emphasized during the past few decades.11

Traditionally, value creation is seen as a value chain,12 which is dominated by various activities of a supplier, whereas the role of customers is marginalized and often neglected. This model of value creation is based on a labour theory view of value, according to which value is gradually worked on in the supplier’s processes, or in a wider context in a supply chain’s different processes. As a result, value is considered embedded in the supplier’s output, and materializes when customers pay money for this output. Therefore, this value concept is labelled value-in-exchange. Normann and Ramírez, suggesting a value constellation model,13 were the first to criticize this view as being provider-centric, excluding the important impact on value by other parties in the supplier-customer ecosystem, and by the customers as users of the output.

As we have demonstrated, all kinds of resources can be offered as service, and as Gummesson14 points out, are used by customers as service that renders value for them. This is supported by Normann and Ramírez,15 who emphasize that a defining aspect of a service perspective is ‘. . . the role (or roles) that the seller plays in helping customers to create value for themselves’. According to the contemporary view, value for customers is created by the customer in the customer’s processes, supported by the resources and processes of service providers. This notion leads to an alternative value concept based on utility theory labelled value-in-use, meaning that value for a customer is created during usage. Another notable difference between value-in-use and value-in-exchange is that value-in-exchange materializes at one particular point of time, i.e. when a sale is concluded and money is paid for the resource, whereas value-in-use evolves over time during the usage or consumption process.16

Another important difference between the two concepts is that value-in-exchange is always positive on some level determined by the price paid, whereas the evolvement of value-in-use can be both positive, ‘value creation; better off’, and negative, ‘value destruction; worse off’.17

In conclusion we may state that customers do not buy goods or services, or any other resources or resource constellations as such, but instead the service the resources can provide them with, which enables value creation in their processes.18 Resources provided to customers over time in a relationship are only facilitators of value. As service providers get in touch with their customers and direct interactions between the provider’s resources and the customer occur, the service provider will engage with the customer’s processes and have opportunities to influence them. Consequently, we can conclude that value for customers is created throughout the relationship by the customer, partly in interactions between the customer and the supplier or service provider.19 The focus is not on the resources, such as goods or services, but on the customers’ processes where value creation occurs.20

VALUE CREATION AND THE VALUE-GENERATING PROCESS

In 1993 Normann and Ramírez pointed out that several parties, such as a supplier, subcontractors to the supplier, financing institutions and the customer itself, contribute to the value that in the end emerges for the customer.21 Some ten years later, Vargo and Lusch stated the same conclusion in their service-dominant logic of value creation and marketing by claiming that customers and firms are always co-creators of value.22 However, as service-dominant logic is more of a systemic approach on a societal level, discussing value co-creation in a metaphorical manner, it is less applicable for management practice. Here we use the management-oriented view of value creation of the service logic approach instead. It provides concepts and instruments that help managers to understand the different roles and goals in value creation of service providers and customers, respectively.23 In Appendix 1, similarities and differences between service logic and service-dominant logic are summarized.24

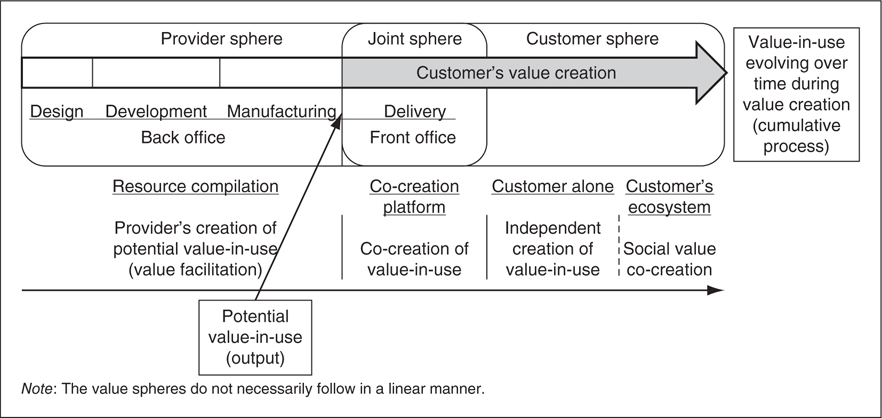

As value for a customer is defined as value-in-use and created by the customer, from a management point of view it is important to clearly define what the service provider does and what the customer does in the total process of creating value for the customer. This total process can be labelled value generation. The value-generation process and its sub-processes are illustrated in Figure 1.5.

As the figure demonstrates, the value generation process can be divided into three spheres: a customer sphere, a provider sphere, and a joint sphere. From a management point of view, keeping these value creation spheres apart is important, because the roles and goals of the service provider and customer respectively differ between spheres.

The customer’s creation of value-in-use takes place in the customer and joint spheres. In the customer sphere two types of value creation take place:

• The customer creates value independently from the service provider.

• The customer engages in social value co-creation with members of his ecosystem, such as family, friends, business associates, or social media connections.

Independent value creation means that the customer makes use of acquired resources, such as goods or services or combinations of these and other resources, and integrates them with other available and needed resources in a usage process. The customer interacts only indirectly with the firm through its products and non-interactive systems which do not respond in more than one way when operated on by the customer. Most products and systems, but of course not all, are like that.

FIGURE 1.5

Value generation process: value creation and co-creation according to the service logic.

Source: Adapted from Grönroos, C. and Voima, P., Critical service logic: making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2); 2013: p. 136. With kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media.

Social value co-creation means that a customer interacts with people in his social ecosystem, and during these interactions the value that evolves for the customer from using goods and services may change in any direction. The customer may become better off or worse off.25

The joint sphere refers to the part of the service process where the customer directly interacts with the service provider. During these direct interactions the provider’s process and the customer’s process do not run in parallel but merge into one interactive, collaborative and dialogical process. In this merged process the two parties relate to each other, work together and communicate in a dialogical fashion. The two parties in the process engage with each other’s processes.26 Hence, they may directly influence each other’s perception of value created in the interactions through communication, actions and reactions. During this merged interactive process a co-creation platform is formed. On this co-creation platform such interactions occur, and they enable the service provider to engage with the customer’s value-creating process and influence this process, and thus co-create value together with the customer.

From a management standpoint, value co-creation between the customer and the service provider occurs only when a co-creation platform has been formed and direct interactions between the two parties take place. Furthermore, it should be observed that it is the customer who drives and is in charge of the value creation process. On the co-creation platform the service provider can be invited to join this process as a value co-creator, but if the customer does not want to listen to the provider, and to communicate and work with the provider, no co-creation takes place. It is the customer’s decision.27 For example, in a restaurant, a guest may choose to listen to the waiter’s explanation about why an item on the menu is missing, and based on a dialogue with the waiter moderate a negative feeling of value, or he may choose not to listen and his value experience will remain negative. In the former situation, the customer invites the provider to co-create value with him, but in the latter situation he does not allow co-creation.

Other than value co-creation in such direct interactions, what is the service provider’s role and goal in the value generation process? In the provider sphere the firm compiles resources, such as products, services, information and other types, or resource constellations, which are offered to customers. These offerings include potential value-in-use as an output from the firm’s resource compilation process. The service provider’s goal is to facilitate the customer’s creation of value-in-use by providing value-supporting resources as potential value-in-use, which this customer may convert into realized value-in-use in their own sphere.28 If and only if a co-creation platform of direct interactions exists or can be established, in addition to the role of value facilitator the service provider may also co-create value-in-use with its customers.29

In conclusion, according to a service logic:

• The customer is the value creator (of value-in-use) in the customer sphere and in the joint sphere (if such a sphere has been established).

• The service provider is fundamentally a value facilitator in the provider sphere through resource compilation aimed at provision of potential value-in-use.

• Provided that direct interactions between the firm and the customer occur or can be created, a co-creation platform is formed, and the service provider has an opportunity to engage with the customer’s value-creating process and co-create value with the customer as well in the joint sphere.

• If interactions between the customer and people in his ecosystem occur, social value co-creation takes place in the customer sphere.

In the following section the co-creation platform will be discussed and two models of value co-creation presented.

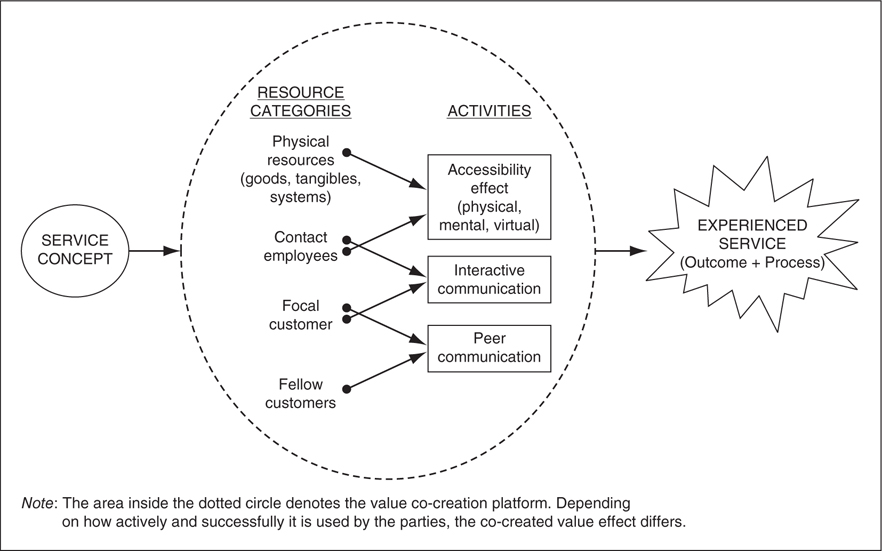

MODELS OF VALUE CO-CREATION

There have been some attempts to develop models of value co-creation, but this has turned out to be difficult, probably because co-creation has been considered an omnipresent phenomenon in the relationship between a firm and a customer, where everything is co-creation. In this section we present models of value co-creation, which are based on the service logic view, according to which co-creation of value requires a co-creation platform of direct interactions between a service provider and a customer. Value co-creation is a reciprocal process. On the co-creation platform it is not only the firm that may influence the customer’s value creation; it works the other way as well. In addition to the price paid for service, the customer may also provide other value-supporting service in return, such as feedback about how the provider’s systems function and information about how to improve them to make them more competitive.

Hence, two models of value co-creation are presented, one about value for the customer, and a reverse model about value for the service provider. In Figure 1.6 a model of co-creating value for the customer, based on the servuction model by Eiglier and Langeard and the interactive marketing model by Grönroos, is illustrated.30 The servuction model provides the resource categories to the left in the circle in the middle of the figure. The different activities to the right in this circle are suggested in the interactive marketing model.

FIGURE 1.6

Value co-creation: value for the customer.

Source: Grönroos, C., Conceptualising value co-creation: a journey to the 1970s and back to the future. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(13–14); 2012: p. 1528. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis.

The model moves from the left to the right. The starting point is a governing service concept, which states what the service provider attempts to do for its customers. There are four resource categories: physical resources, including goods, other tangible elements and systems, and of course also IT-based technologies,31 contact employees interacting with the customers, the focal customer, for whom service is provided, and fellow customers simultaneously present in the service process.

In the direct interactions between the resources on the co-creation platform, three types of influence on the focal customer’s value creation may take place. The physical resources and contact employees create an accessibility effect in the service process, which makes the service easier or more complicated to access and use, and therefore influences the customer’s perception of the service. This effect may be physical, mental, or even virtual. The contact employees and the focal customer engage in a dialogical interactive communication, which also influences the focal customer’s perception of the service. Finally, the focal customer and fellow customers may communicate with each other (peer communication), which can have a similar effect. These influences on the service have a continuous separate and/or combined effect on the focal customer’s service experience, both with the outcome of the service process and with the process itself (in Chapter 4, Service and relationship quality, the quality effects of the outcome and the service process will be further discussed). The focal customer’s co-created value perception is grounded in this experience, and may continue to evolve during an independent value creation and social value co-creation phase that may follow.

As an example, we can think about a restaurant. The waiter (contact employee) and the various physical resources and systems, such as the food, tables and chairs, atmospheric artefacts, menus and serving and paying systems, and other resources, together make the restaurant service accessible both from a physical and mental standpoint. In the interactions between the restaurant guest as the focal customer and the waiter, the guest asks, for example, clarifying questions about items on the menu, the waiter responds and makes suggestions, and on top of that non-task related communication may take place. These discussions form interactive communication between the guest and the contact employee. If there are fellow customers in the restaurant, the guest may discuss the restaurant or the menu with them, or the behaviour of fellow customers may in many other ways communicate something, good or bad, about being in the restaurant. For example, too noisy a company at a nearby table may create negative communication. All this is peer communication.

The various activities exemplified above in a restaurant context form a co-creation platform with direct interactions. These various types of interactions form the restaurant guest’s, the focal customer’s, experience with the restaurant service. This experience makes the customer better off in various degrees, or in a negative situation, worse off. Hence, value-in-use co-created by the resources on the co-creation platform emerges. After the customer has left the restaurant, this value may evolve further, for example, when he continues to think about it or about an element of it, such as the excellent food or impeccable service.

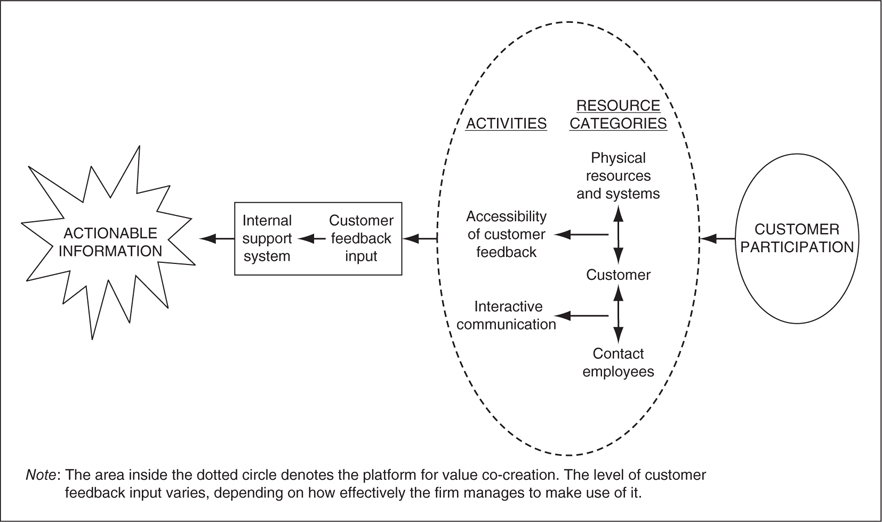

However, continuing the restaurant example, value is not only co-created for the customer. Co-created value may flow in the other direction as well, forming a reverse value co-creation model. Figure 1.7 includes a model of co-creating value for the service provider.

In this model, as illustrated by the figure, the value process moves from right to left. The starting point is the customer’s participation in the restaurant’s service process. In this reverse value co-creation model there are three resource categories: physical resources and systems, the customer, and contact employees. The activities in the value co-creation process are accessibility of customer feedback and interactive communication. The output of this reverse model is actionable information which the firm can use for developing its resources, systems and processes, and even its service concept. The amount of information depends on how prepared the firm is to register customer feedback. There must be some kind of internal support system – either formal or informal, but still supporting an internal flow of customer feedback – for registering feedback and analysing it and turning it into actionable information and knowledge.

FIGURE 1.7

Value co-creation in service: value for the service provider.

Source: Grönroos, C., Conceptualising value co-creation: a journey to the 1970s and back to the future. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(13–14); 2012: p. 1530. Reproduced by permission of Taylor & Francis.

In the restaurant example, the customer interacts with the waiter and other employees, and interactive communication occurs. This communication may include either direct complaints or direct suggestions about improvements, or it may in a more subtle way include ideas for future use. If the contact employees are encouraged to gather such information, and have the skill to do it, and if there is a system for registering it for management use, this is co-created value for the restaurant.

Furthermore, in addition to interactions with the waiter, the customer also interacts with and perceives the many physical resources and systems of the restaurant. Sometimes the customer does not voice his perceptions of these interactions with contact employees and physical resources and systems in interactive communication with employees, but still he wants to make them known to the service provider. In order to make such feedback information accessible to the restaurant, or any firm, an easily usable system for customer complaints and feedback through various means should be used. Internet-based systems for gathering customer feedback are frequently used, but old-fashioned paper-based systems can also exist. The important thing is that customers who did not want to give feedback directly, for example in the restaurant, or who later came to think about something to communicate, should be offered an easily accessible feedback system, which in turn makes the feedback information accessible to the firm.32

If the firm manages to register customer feedback information either based on interactive communication during the service process or from a feedback system that makes it easy to give feedback after the service process, then actionable information to be used to change or improve the service process or some part of it, or to develop the service concept, is accessed. This is a reverse value co-creation process, which gives the provider valuable means for improving its operations.

THE SERVICE PERSPECTIVE

Here and in the following sections we will discuss in more detail what a service perspective on business means, and contrast this perspective with three other strategic perspectives.

Many firms fall into the trap of competing with low prices, which may sometimes be effective, but most often is a way of giving away the revenue that is needed to create and maintain a sustainable advantage over the competition. Price is never a sustainable advantage. As soon as a competitor can offer a lower price, the customer will be gone. Every firm, regardless of whether its core product is a physical good or a service, or whether the firm is operating in consumer markets or business-to-business markets, has the option of taking a service perspective. A service perspective will enable management to see different opportunities to create a competitive advantage compared with other strategic perspectives, and more importantly, it forces the firm to get closer to its customers and acquire much more insight about the customers’ life and business than is normally the case. By adopting a service perspective and providing service, the likelihood that a firm becomes meaningful for its customers increases.

THE SERVICE PERSPECTIVE COMPARED WITH OTHER STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES

Firms can choose from a number of strategic perspectives, of which a service perspective is one. For example, four major strategic perspectives can be distinguished as follows:

• Service perspective.

• Core product perspective.

• Price perspective.

• Image perspective.

First, the three comparison perspectives will be described briefly, followed by the service perspective.

A core product perspective is a traditional scientific management-based approach,33 where the quality of the core solution is considered to be the main source of competitive advantage. A firm that, for example, has a sustainable technological advantage can benefit from applying such a perspective. The core product is supposed to be the sole or major carrier of potential value for customers. In such cases, services or singular service activities may be included as necessary elements in customer relationships, but their role is not strategic. A firm that adopts a core product perspective without having a technological advantage often falls into the price trap. In the long run, this is not a sustainable strategy. Such a core product perspective is often also adopted by service firms, such as banks and insurance companies, where the core service, for example a loan concept or an insurance policy, is considered the key source of competitive advantage. In a competitive situation, this seldom works well. Such a service firm reverts to being a product firm taking an inside-out management approach.

Taking a price perspective means that the firm considers a continuously low price to be the major means of competition. If a sustainable cost advantage can be achieved and maintained, this is a possible perspective to take. The firm may still obtain an acceptable profit margin so that it can invest in its future. However, if the cost advantage is lost, a strategic approach based on a price perspective becomes dangerous. Prices are pressed further down by the competition, and the firm loses its chance to develop for the future. Adopting a price strategy leads to an inside-out management approach. Such a strategy works if the customers accept the lower level of service which goes with the lower price.

An image perspective will make the firm use mostly marketing communications to create imaginary values in addition to the potential value of the core offering. For some types of goods and services – for example, fashion products such as designer clothes and perfumes, some consumer packaged goods such as soft drinks and some service such as fast-food restaurants – an image approach has been effective. Such a strategic approach requires there to be an attractive and functioning core product as a starting point. The offering also easily becomes very dependent on the imaginary extras created by the firm’s marketing strategy. If the firm stops reinforcing them, they may eventually deteriorate to just another physical product or service in the marketplace. Therefore, pursuing an image strategy demands continuous heavy investment in marketing communication. If the firm cannot afford this, the offering (consisting of a core physical good or service and a weakening image-boosting support) will lose its attractiveness, and competitors who can continue to invest extensively in marketing communication will take over. Also in an image strategy management is easily dominated by an inside-out approach.

A service perspective is based on an outside-in management approach, whereby the firm aims to support its customers’ everyday processes in a way that facilitates value creation in individual customers’ life processes and business-to-business customers’ business processes. The core solution, whether a physical good or a service, has to be good enough to provide a competitive advantage, but this is not enough for success in the marketplace, or in the digital marketspace. What creates a sustainable competitive advantage is the development of every element of the customer relationship, including all types of resources and processes, into one overall service offering. The driving force is the service perspective, according to which customers are served with a value-supporting combination of goods and services, additional separately billable services, such as repair and maintenance, and other non-billable services, such as invoicing, complaints handling, advice and personal attention, information and other value-supporting components. This situation can be described as service competition.34 This is a competitive situation where the core solution is the prerequisite for success, but where the management of a number of other required resources, together with the core solution, forms a total service offering, aiming at supporting customer processes. The total service offering determines whether or not the firm will be successful. This book is about how to manage an organization and its customer relationships in service competition.

The central requirement of management in service competition is to appreciate the service perspective as a strategic approach and understand how to manage the firm in order to develop a total service offering. This is called service management, and can be seen as an alternative management approach to scientific management,35 geared to the demands of service competition. Service management as a management focus will be discussed in detail in Chapter 3 on the service profit logic and service management principles and in subsequent chapters.

HIDDEN AND RECOGNIZED SERVICES

In order for firms to develop a total service offering successfully, they must observe that two kinds of service elements are included in such an offering:

• Recognized services.

• Hidden services.

Recognized services, such as repair and maintenance and consultancy, are thought of as service activities by management. Sometimes, but not always, they are billable, which means that a price can be put on them. These services form only a part of the service offered to customers. For example, all customers, individual consumers as well as organizations and business-to-business customers, note the way a firm handles invoicing, takes care of quality problems, mistakes and service failures, manages complaints, offers documentation and directions for the use of goods and services, offers customer training on how to use machines, equipment and software, handles queries and answers questions and e-mails, pays attention to customers and their special requests and wishes, keeps promises and delivers promptly, etc. The clarity and accuracy of invoices, speed and efficiency in managing failures and complaints, the attention that employees show customers and the promptness with which actions are taken all influence a customer’s perception of the value of being a customer of a given supplier or service provider. In addition, this also creates more or less costs for the customer, for example costs of processing invoices and following up on complaints, and corrections of the problems causing the need to complain. They either make it easier or more troublesome to be a customer and also frequently help the customer to save money. The way these services function contributes to making it worthwhile for customers to continue purchasing from the same firm, and prevents customers from considering alternative options. Hence, these normally non-billable types of service components also contribute to the creation of a competitive advantage.

The problem with hidden services such as invoicing, complaints handling, documentation and customer training is that they are seldom perceived as service by management, and therefore are frequently not designed and managed as value-supporting service to customers. Instead, they are managed as administrative, legal or operational routines with internal efficiency criteria and cost consideration as the main guidelines. As a result, customers generally do not perceive most of these as value-enhancing activities. However, the use of hidden services in customer relationships is a powerful way of setting apart a firm from its competitors and of supporting a sustainable competitive advantage.

CHOOSING STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVE

A firm can choose any one of the perspectives discussed above. Following this choice it will develop a strategic approach which differs from the approach that would have been taken if another strategic perspective had been adopted. Choosing one strategic perspective does not mean that aspects of the other perspectives are not important. However, the choice of a perspective determines the way a firm will develop resources and competencies. For example, choosing a service perspective as the main strategy does not mean that less attention than otherwise will be paid to production technologies and the technical quality of the core solution. Elements from perspectives other than the dominating one, however, have always to be geared to the requirements of the dominating perspective. The fine-tuning of a strategic approach varies, of course, but Table 1.2 shows in a simplified way the strategic orientation of the four strategic perspectives.

Characteristics of strategic perspectives.

Strategic perspective |

Characteristic of a corresponding strategic approach |

Service perspective |

The firm takes the view that a service offering is required to support the customer’s value creation, and that the core solution (a physical product, service or combination of goods and services) is not sufficient to differentiate the offering from those of competitors. Physical product components, service components, information, personal attention and other elements of customer relationships are combined into a total service offering. Because it provides service to the customer, the offering is labelled a service offering, although the core solution may be based on a physical product, because all elements of the offering are combined to provide a value-supporting service for customers. Developing such a total service offering is seen to be of strategic importance and therefore given highest priority by management. Hidden services, both billable and non-billable, are considered part of this offering and supportive to the customer’s value-creating processes. Price is considered less important for customers than long-term costs. A firm that adopts a service perspective will consider itself a service business. |

Core product perspective |

The firm concentrates on the development of the core solution, whether this is a physical product or a service, as the main provider of value for the customer’s value-creating processes (the customer’s use of solutions to create value for himself or for an organizational user). Additional services may be considered necessary but not of strategic importance, and therefore they have a low level of priority. Hidden services, especially non-billable ones, are not recognized as value-enhancing services. The firm differentiates its package from others through providing an excellent core solution. |

Price perspective |

The firm takes the view that price is the dominating purchasing criterion of its customers, and that being able to offer a low price is a necessity for survival in the marketplace. Price is seen as the main contribution to the customer’s value-creating processes. The provision of additional services is not considered value-enhancing and is therefore of lower priority than the capability to offer a low-price solution. Price is considered more value-enhancing than the long-term cost effects of a solution. The firm is differentiating its offering by being the cheapest alternative available, or one of the cheapest. |

Image perspective |

The firm differentiates its offering by creating imaginary extras (a brand image) around its core product. Such extras are mainly created in the minds of customers by advertising and marketing communication. The core solution is seen as a starting point for the development of customer value, but the brand image that is created by marketing is considered to be the major contribution to the customer’s value-creating processes. |

A CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP PERSPECTIVE

Service as a perspective and service activities are inherently relational. A service encounter, where a customer, for example, is a restaurant guest or has a machine repaired, is a process. At some point in this process the service provider is normally present, interacting with the customer. Even a single encounter includes relational elements. If several encounters follow each other in a continuous or discrete fashion, and if both parties want it, a relationship may emerge. If a customer feels that there is something special and valuable in his contacts with a given firm, a relationship may develop. Perceived relationships are not enough to make customers loyal, but they are a central part of loyalty, and loyal customers are normally, but not always,36 profitable customers.

Relationship marketing has emerged, or rather re-emerged, as a marketing paradigm.37 Marketing and management based on customer relationships is seen as an alternative to focusing on transactions or exchanges of goods and services for money. Firms choosing a service perspective as their strategic approach almost inevitably have to focus on relationships with their customers and other stakeholders, such as suppliers, distributors, financial institutions and shareholders. Thus, understanding relationship marketing and how to manage customer relationships becomes a necessity for understanding how to manage a firm in service competition. Hence, the approach to managing in service competition taken in this book is geared towards a customer relationship-based view as a dominating marketing perspective.

THE LOGIC OF SERVICE COMPETITION

Service competition is nothing new. Service firms such as banks, hotels, restaurants and transportation companies have always faced such situations. They have not always realized what this requires of them, and therefore sometimes reverted to a product strategy and inside-out management. However, firms in more and more industries, regardless of whether they are traditionally categorized as service or manufacturing industries, now find themselves in a situation where the core product only offers a starting point for the development of a competing advantage, but does not guarantee it any more. In such a situation a service perspective offers an approach to the strategic reorientation. The development of the core product into a service offering, including product elements and recognized and hidden services, may make the firm competitive again. Service competition has become a reality for most firms.

There are at least three reasons for the need to focus on service. The demand for adopting a service perspective, and thus for learning how to cope with service competition, is partly customer-driven, partly competition-driven and partly technology-driven. First, customers in a greater number of markets demand more than a mere technical solution to a problem provided by a service firm or a manufacturer. Customers are gradually becoming more sophisticated, more informed and, consequently, more demanding. By and large, they are looking for more comfort, fewer problems, lower additional costs and less trouble caused by the use of goods and services; in short, they are looking for better value. Second, this demand by customers is constantly enhanced by competition, which is becoming increasingly global. In the pursuit of more valuable offerings for their customers, firms turn to service, and thus force competitors to appreciate the importance of service too. Third, technological developments, especially in the area of information technology and digital solutions, enable firms to create new service more easily. An early example of this was the just-in-time approach to logistics, which to be successfully implemented required high-powered computerized information systems. More recently, the development of the Internet and e-business and mobile commerce has also made it possible to create new service. The Internet is a highly relational tool, making it possible for firms to develop interactive and relationship-building contacts with their customers, thus enhancing the value support of their core solution. The emergence of mobile commerce reinforces this trend. By and large, new information technology often makes it easier to maintain relationships with customers, as well as creating new ways of doing so.38 At the same time electronic and mobile technologies make it possible for customers to maintain contact with service providers and use their service free from time and spatial restrictions, thereby providing the everyday activities of customers who appreciate this with additional value-creating support.39

When new elements are added to the goods and service components of customer relationships, these relationships are expanded. Traditionally, marketing and sales organized in marketing and sales departments have been responsible for customers. The other departments of the firm were involved only to a limited extent. As the relationship grows in scope, more functions are in immediate contact with customers: for example, bank tellers and ATMs, service technicians involved in the repair and maintenance of machines and equipment, telephone receptionists, call centre and contact centre systems, people in R&D departments. Responsibility for developing and maintaining customer relationships, which is normally called ‘marketing’, is no longer solely related to the marketing department and the marketing director. In the organizational structure this new shared responsibility for the customer has to be recognized and accepted.

As mentioned, in the literature there are two major ways of understanding the service perspective on business, service logic and service-dominant logic. Because the latter approach tends be basically systemic and societal and advances the understanding of the service perspective on a systemic level, in this book, which is about service management, we follow the service logic approach. Service logic takes a management-level approach to understanding and managing a service perspective.40 In Appendix 2 the managerial principles of service logic are summarized. Table 1.3 provides a comparison between some central elements of service logic and goods logic relating to, respectively, a service perspective and product perspective on business.

Finally, it is important to realize that although customers’ experiences with service and a service provider is considered important for value creation, most service situations are very ordinary and mundane, such as travelling on a bus, operating a vending machine or making a phone call. Although experiences sometimes can be enhanced and made exclusive, as suggested by Pine and Gilmore,41 the ordinary service situations must also be handled successfully, such that the customer’s processes are supported successfully.

WHAT IS A RELATIONSHIP?

Relationships occur between two or more parties. In much of the management and marketing literature on the subject the questions ‘what is a relationship?’ or ‘when do we know that a relationship has developed?’ are not discussed.

Service logic versus goods logic.

Service is a holistic process aiming at supporting customers’ processes. |

Goods are resources delivered to customers for their use. |

Value evolves over time during the customers’ use of resources. |

Value is embedded in resources. |

Direct interaction between the firm and its customers exist and form a co-creation platform. |

Customers interact only indirectly with the firm through their use of products and non-interactive systems. No co-creation platforms exist. |

The firm may co-create value with its customers on the co-creation platform. |

Firms cannot co-create value with its customers. |

By compiling resources to be used by its customers, the firm provides potential value-in-use for them. Through co-creational and independent value creation as well as social value co-creation, the value potential is realized by the customers as value-in-use which evolves during the value creation process. |

Value for customers is embedded in resources, and materializes as value-in-exchange at the point and time of purchase. |

The firm can go beyond promising value for its customers, and influence its customers’ value creation directly and actively on the co-creation platform, and thus marketing breaks free from its traditional restriction of only being able to make promises offered through value propositions. |

Because a co-creation platform is missing, the firm is restricted to making promises about customer value only, through offering value propositions. |

One thing is quite clear: a relationship with a customer has not been established only because the marketer has said it has, or believes it has. Far too often marketers state that they have turned to relationship marketing and believe that their marketing efforts are relationship-oriented, without making sure that the customers see it in the same way. In reality, if one asks the customers, much of what marketing practitioners call relationship marketing has very little to do with creating or maintaining customer relationships.42 A firm may provide more tailor-made direct mail, customized e-mail or mobile contacts, membership of a loyalty club or the like, but for the customer this may mean the same slow service and uninterested service personnel, no or late responses to e-mails or phone calls, or slow complaints handling. The customer may benefit from improved direct contacts and membership in a loyalty club, but this is not relationship-based customer management, and no relationship has developed. A relationship can develop only when all, or at least most, important customer contacts and interactions are relationship-oriented.