Chapter 4

Dividend and Interest Income

Dividends and interest that are paid to you are reported by the payer to the IRS on Forms 1099.

You will receive copies of:

- Forms 1099-DIV, for dividends

- Forms 1099-INT, for interest

- Forms 1099-OID, for original issue discount

Dividends paid by most domestic corporations and many foreign corporations are subject to the same preferential tax rates as net long-term capital gains (4.2).

Report the amounts shown on the Forms 1099 on your tax return. The IRS uses the Forms 1099 to check the income you report. If you fail to report income reported on Forms 1099, you will receive a statement asking for an explanation and a bill for the tax deficiency. If you receive a Form 1099 that you believe is incorrect, contact the payer for a corrected form.

Do not attach your copies of Forms 1099 to your return. Keep them with a copy of your tax return.

4.1 Reporting Dividends and Mutual Fund Distributions

Dividends paid to you out of a corporation’s earnings and profits are taxable as ordinary income. The corporation will report dividends on Form 1099-DIV (or equivalent statement). Mutual fund dividends and distributions are also reported on Form 1099-DIV (or similar form). Corporate dividends and mutual fund distributions of $10 or more are reported on Form 1099-DIV (or equivalent) whether you receive them in cash or they have been reinvested at your request.

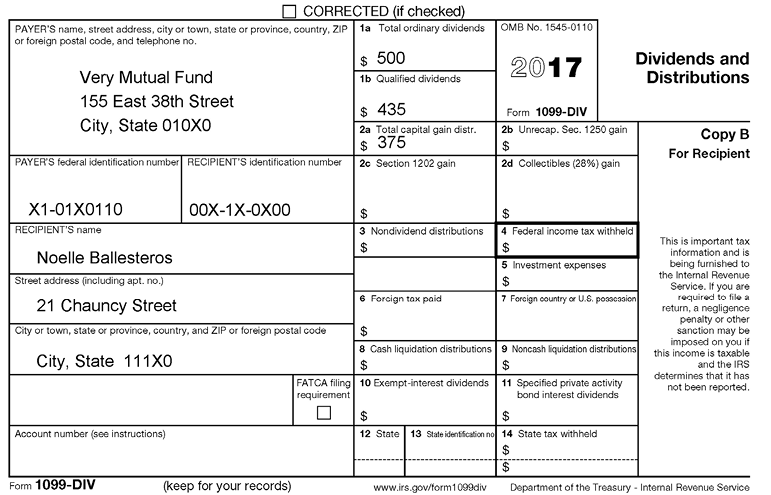

Form 1099-DIV. Form 1099-DIV for 2017 gives you a breakdown of the dividends and distributions paid to you during the year. A mutual fund or real estate investment trust (REIT) dividend paid to you in January 2018 will also be reported to you on the 2017 Form 1099-DIV if it was declared in and payable to you as a shareholder of record in October, November, or December of 2017. The company or fund may send a statement that is similar to Form 1099-DIV. You do not have to attach the Form 1099-DIV (or similar statement) to your tax return.

Box 1a. Ordinary dividends taxed to you are shown in Box 1. These are the most common type of distribution, payable out of a corporation’s earnings and profits. Your share of a mutual fund’s ordinary dividends is also shown on Form 1099-DIV; short-term capital gain distributions are included in the Box 1a total.

Box 1b. Part of the Box 1a amount may be qualified dividends. Qualified dividends reported in Box 1b are generally taxed at the same favorable rates (zero, 15% or 20%) as net capital gains. See 4.2 for further details on qualified dividends.

Boxes 2a–2d. Capital gain distributions (long term) from a mutual fund (or real estate investment trust) are shown in Box 2a. Box 2b shows the portion of the Box 2a amount, if any, that is unrecaptured Section 1250 gain from the sale of depreciable real estate. Box 2c shows the part of Box 2a that is Section 1202 gain from small business stock eligible for an exclusion (5.7). Box 2d shows the amount from Box 2a that is 28% rate gain from the sale of collectibles. If any amount is reported in Box 2b, 2c, or 2d, you must file Schedule D with Form 1040 (5.3).

Box 3. Nontaxable distributions that are a return of your investment are shown in Box 3; see “Return of capital distributions” below.

Box 4. If you did not give your taxpayer identification number to the payer, backup withholding at a 28% rate (26.10) is shown in Box 4.

Box 5. Your share of expenses from a non–publicly offered mutual fund is shown in Box 5 and may be deductible as a miscellaneous itemized deduction subject to the 2% floor (19.16). This amount is included in Box 1a.

Boxes 6 and 7. The foreign tax shown in Box 6 (imposed by the country shown in Box 7) may be claimed as a tax credit on Form 1116 or as an itemized deduction on Schedule A (36.13s).

Boxes 8 and 9. Cash and noncash liquidation distributions are shown in these boxes.

Nominee distribution—joint accounts. If you receive dividends on stock held as a nominee for someone else, or you receive a Form 1099-DIV that includes dividends belonging to another person, such as a joint owner of the account, you are considered to be a “nominee recipient.” If the other owner is someone other than your spouse, you should file a separate Form 1099-DIV showing you as the payer and the other owner as the recipient of the allocable income. For 2017 dividends, give the owner a copy of Form 1099-DIV by January 31, 2018, so the dividends can be reported on his or her 2017 return. File the Form 1099-DIV, together with a Form 1096 (“Transmittal of Information Return”), with the IRS by February 28, 2018; the deadline is April 2, 2018, if filing electronically.

On your Schedule B (Form 1040 or 1040A), you list on Line 5 the ordinary dividends reported to you on Form 1099-DIV. Several lines above Line 6, subtract the nominee distribution (the amount allocable to the other owner) from the total dividends. Thus, the nominee distribution is not included in the taxable dividends shown on Line 6 of Schedule B or Schedule 1.

Return of capital distributions. A distribution that is not paid out of earnings is a nontaxable return of capital, that is, a partial payback of your investment. The company will report the distribution in Box 3 of Form 1099-DIV as a nontaxable distribution. You must reduce the cost basis of your stock by the nontaxable distribution. If your basis is reduced to zero by a return of capital distributions, any further distributions are taxable as capital gains, which you report on Schedule D of Form 1040. Form 1040A or Form 1040EZ may not be used.

4.2 Qualified Corporate Dividends Taxed at Favorable Capital Gain Rates

Dividends paid out of current or accumulated earnings of a corporation are taxable (4.5). Stock dividends on common stock (4.6) are generally not taxable, but other types of stock dividends are taxed (4.8).

Dividends from most domestic corporations and many foreign corporations are treated as “qualified dividends,” which are subject to the same favorable rates as net capital gain (the excess of net long-term capital gains over net short-term losses (5.3) ). The rate on your qualified dividends is either zero, 15% or 20%, depending on the rate that would otherwise apply to the dividends if they were taxed as ordinary income (5.3) . More than one of the reduced rates may apply to your qualified dividends depending on their amount and your other income. The benefit of the reduced rates is obtained as part of the computation of tax liability on the “Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet” in the instructions for Form 1040 or Form 1040A, or, if required, on the Schedule D Tax Worksheet (5.3).

Generally, the zero rate applies to taxpayers whose top bracket is 10% or 15%. Such taxpayers are not taxed at all on their qualified dividends and net capital gain. However, the zero rate is generally not available for qualified dividends (or net capital gain) earned by children and students under age 24 who are subject to the “kiddie tax” rules (24.2); their dividends and gains are taxed as if earned by their parents, who likely are subject to the 15% or 20% (rather than zero) rate on dividends/gains. Although the zero rate is intended to benefit taxpayers with modest incomes, taxpayers with substantial dividends/gains whose top bracket would be 25% or higher (assuming there were no capital gain rates) may pay no tax (zero rate) on a portion of their qualified dividends/net capital gains, provided their ordinary income (such as salary and interest) is low; see the Examples in 5.3.

On Form 1099-DIV for 2017, the amount of qualified dividends eligible for the capital gain rate will be shown in Box 1b. To be eligible, the dividend must be received on stock you held at least 61 days during the 121-day period beginning 60 days before the ex-dividend date. The ex-dividend date is the first date following the declaration of a dividend on which the purchaser of the stock is not entitled to receive the dividend (4.9). When counting the number of days you held the stock, include the day you disposed of the stock but not the day you acquired it. You cannot count towards the 61-day test any days on which your position in the securities was hedged, thereby diminishing your risk of loss.

Some dividends from a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) may be reported as qualified distributions on Form 1099 although they are not actually qualified distributions and cannot be reported as such on your return. Both you and the fund must hold the underlying security for the required 61-day period. The fund may report a dividend as qualifying without taking into account whether you purchased or sold your shares during the year, so you must determine whether you have met the 61-day holding period test for the shares on which the dividends were paid. When counting the number of days you held the shares, include the day you disposed of the shares but not the day you acquired them.

Generally, distributions on preferred stock instruments do not qualify for qualified dividend treatment because the instruments are hybrid securities that are treated as debt and not stock. Payments on such hybrid instruments are considered interest rather than dividends and thus are not eligible for the reduced tax rate. If the preferred instrument is treated as stock, the reduced rate does not apply to dividends attributable to periods totaling less than 367 days unless the 61-day holding period (discussed above) is met. If the dividends are attributable to periods of more than 366 days, the stock must be held at least 91 days in the 181-day period starting 90 days before the ex-dividend date.

Some dividends are actually interest. Distributions that are called dividends but are actually interest income, such as payments from credit unions and mutual savings banks, are not eligible for the reduced dividend rate. Similarly, certain dividends from exchange-traded funds (ETFs) and from mutual funds represent interest earnings and are not eligible for the reduced rate. Dividends paid by a real estate investment trust (REIT) generally are not eligible, but the reduced rate does apply to REIT distributions that are attributable to corporate tax at the REIT level or which represent qualified dividends received by the REIT and passed through to shareholders.

Dividends from foreign corporations qualify for the reduced rate if the corporation is traded on an established U.S. securities market, incorporated in a U.S. possession, or certain treaty requirements are met.

If your broker loans out your shares as part of a short sale, substitute payments in lieu of dividends may be received on your behalf while the short sale is open. Such substitute payments are not considered dividends and should be included in Box 8 of Form 1099-MISC and reported by you as “Other income” on Line 21 of Form 1040.

Tax-deferred retirement accounts such as traditional IRAs and 401(k) plans do not benefit from the reduced dividend rate. Distributions from such retirement plans are taxable as ordinary income even if the distribution is attributable to dividends that otherwise meet the tests for qualified dividends.

4.3 Dividends From a Partnership, S Corporation, Estate, or Trust

Dividends you receive as a member of a partnership, stockholder in an S corporation, or as a beneficiary of an estate or trust may be qualified dividends eligible for the reduced capital gain rate of zero, 15%, or 20%(4.2).

A distribution from a partnership or S corporation is reported as a dividend only if it is portfolio income derived from nonbusiness activities. Your allowable share of the dividend will be shown on the Schedule K-1 you receive from the partnership or S corporation.

4.4 Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Dividends

Dividends from a real estate investment trust (REIT) are shown on Form 1099-DIV. Ordinary dividends reported in Box 1a are taxable at ordinary income rates except for the portion, if any, shown in Box 1b that qualifies for the zero, 15% or 20% capital gain rate. Dividends designated by the trust as capital gain distributions in Box 2a are reported by you as long-term capital gains regardless of how long you have held your trust shares. A loss on the sale of REIT shares held for six months or less is treated as a long-term capital loss to the extent of any capital gain distribution received before the sale plus any undistributed capital gains. However, this long-term loss rule does not apply to sales under periodic redemption plans.

4.5 Taxable Dividends of Earnings and Profits

You pay tax on dividends only when the corporation distributing the dividends has earnings and profits. Publicly held corporations will tell you whether their distributions are taxable. If you hold stock in a close corporation, you may have to determine the tax status of its distribution. You need to know earnings and profits at two different periods:

- Current earnings and profits as of the end of the current taxable year. A dividend is considered to have been made from earnings most recently accumulated.

- Accumulated earnings and profits as of the beginning of the current year. However, when current earnings and profits are large enough to meet the dividend, you do not have to make this computation. It is only when the dividends exceed current earnings (or there are no current earnings) that you match accumulated earnings against the dividend.

The tax term “accumulated earnings and profits” is similar in meaning to the accounting term “retained earnings.” Both stand for the net profits of the company after deducting distributions to stockholders. However, “tax” earnings may differ from “retained earnings” for the following reason: Reserve accounts, the additions to which are not deductible for income tax purposes, are ordinarily included as tax earnings.

4.6 Stock Dividends on Common Stock

If you own common stock in a company and receive additional shares of the same company as a dividend, the dividend is generally not taxable (see Chapter 30) for the method of computing cost basis of stock dividends (30.3) and rights and sales of such stock (30.4).

Exceptions to tax-free rule. A stock dividend on common stock is taxable (4.8) when (1) you may elect to take either stock or cash; (2) there are different classes of common stock, one class receiving cash dividends and another class receiving stock; or (3) the dividend is of convertible preferred stock.

Fractional shares. If a stock dividend is declared and you are only entitled to a fractional share, you may be given cash instead. To save the trouble and expense of issuing fractional shares, many companies directly issue cash in lieu of fractional shares or they set up a plan, with shareholder approval, for the fractional shares to be sold and the cash proceeds distributed to the shareholders. Your company should tell you how to report the cash payment. According to the IRS, you are generally treated as receiving a tax-free dividend of fractional shares, followed by a taxable redemption of the shares by the company. You report on Form 8949 and Schedule D (5.8) capital gain or loss equal to the excess of the cash over the basis of the fractional share; long- or short-term treatment depends on the holding period of the original stock. In certain cases, a cash distribution may be taxed as an ordinary dividend and not as a sale reported on Form 8949 (and Schedule D); your company should tell you if this is the case.

Stock rights. The rules that apply to stock dividends also apply to distributions of stock rights. If you, as a common stockholder, receive rights to subscribe to additional common stock, the receipt of the rights is not taxable provided the terms of the distribution do not fall within the taxable distribution rules (4.8).

4.7 Dividends Paid in Property

A dividend may be paid in property such as securities of another corporation or merchandise. You report as income the fair market value of the property. A dividend paid in property is sometimes called a dividend in kind.

Corporate benefit may be treated as constructive dividend. On an audit, the IRS may charge that a benefit given to a shareholder-employee should be taxed as a constructive dividend. For example, the Tax Court agreed with the IRS that a corporation’s payment for a license that gave the sole shareholder the right to buy season tickets to Houston Texans football games was a constructive dividend to the shareholder.

4.8 Taxable Stock Dividends

The most frequent type of stock dividend is not taxable: the receipt by a common stockholder of a corporation’s own common stock as a dividend (4.6).

Taxable stock dividends. The following stock dividends are taxable:

- Stock dividends paid to holders of preferred stock. However, no taxable income is realized where the conversion ratio of convertible preferred stock is increased only to take account of a stock dividend or split involving the stock into which the convertible stock is convertible.

- Stock dividends elected by a shareholder of common stock who had the choice of taking stock, property, or cash. A distribution of stock that was immediately redeemable for cash at the stockholder’s option was treated as a taxable dividend.

- Stock dividends paid in a distribution where some shareholders receive property or cash and other shareholders’ proportionate interests in the assets or earnings and profits of the corporation are increased.

- Distributions of preferred stock to some common shareholders and common stock to other common shareholders.

- Distributions of convertible preferred stock to holders of common stock, unless it can be shown that the distribution will not result in the creation of disproportionate stock interests.

Constructive stock dividends. You may not actually receive a stock dividend, but under certain circumstances, the IRS may treat you as having received a taxable distribution. This may happen when a company increases the ratio of convertible preferred stock.

4.9 Who Reports the Dividends

Stock held by broker in street name. If your broker holds stock for you in a street name, dividends earned on this stock are received by the broker and credited to your account. You report on your 2017 return all dividends credited to your account in 2017. The broker is required to file an information return on Form 1099 (or similar form) showing all such dividends.

If your statement shows only a gross amount of dividends, check with your broker if any of the dividends represented nontaxable returns of capital.

Dividends on stock sold or bought between ex-dividend date and record date. Record date is the date set by a company on which you must be listed as a stockholder on its records to receive the dividend. However, in the case of publicly traded stock, an ex-dividend date, which usually precedes the record date by several business days, is fixed by the exchange to determine who is entitled to the dividend.

If you buy stock before the ex-dividend date, the dividend belongs to you and is reported by you. If you buy on or after the ex-dividend date, the dividend belongs to the seller.

If you sell stock before the ex-dividend date, you do not have a right to the dividend. If you sell on or after the ex-dividend date, you receive the dividend and report it as income.

The dividend declaration date and date of payment do not determine who receives the dividend.

Nominees or joint owners. If you receive ordinary dividends on stock held as a nominee for another person, other than your spouse, give that owner a Form 1099-DIV and file a copy of that return with the IRS, along with a Form 1096 (“Transmittal of U.S. Information Return”). The actual owner then reports the income. List the nominee dividends on Schedule B (Form 1040 or Form 1040A) along with your other dividends, and then subtract the nominee dividends from the total.

Follow the same procedure if you receive a Form 1099-DIV for an account owned jointly with someone other than your spouse. Give the other owner a Form 1099-DIV, and file a copy with the IRS, along with a Form 1096. The other owner then reports his or her share of the joint income. On your return, you list the total dividends shown on Forms 1099-DIV and subtract from the total the nominee dividends reported to the other owner.

4.10 Year Dividends Are Reported

Dividends are generally reported on the tax return for the year in which the dividend is credited to your account or when you receive the dividend if paid by check.

Dividends received from a corporation in a year after the one in which they were declared, when you held the stock on the record date, are taxed in the year they are received; see Example 4 below.

4.11 Distribution Not Out of Earnings: Return of Capital

A return of capital or “nontaxable distribution” reduces the cost basis of the stock. If your shares were purchased at different times, reduce the basis of the oldest shares first. When the cost basis is reduced to zero, further returns of capital are taxed as capital gains on Schedule D. Whether the gain is short term or long term depends on the length of time you have held the stock. The company paying the dividend will usually inform you of the tax treatment of the payment.

Life insurance dividends. Dividends on insurance policies are not true dividends. They are returns of premiums you previously paid. They reduce the cost of the policy and are not subject to tax until they exceed the net premiums paid for the contract. Interest paid or credited on dividends left with the insurance company is taxable. Dividends on VA insurance are tax free, as is interest on dividends left with the VA.

Where insurance premiums were deducted as a business expense in prior years, receipts of insurance dividends are included as business income. Dividends on capital stock of an insurance company are taxable.

4.12 Reporting Interest on Your Tax Return

You must report all taxable interest. Forms 1099-INT, sent by payers of interest income, give you the amount of interest to enter on your tax return. Although they are generally correct, you should check for mistakes, notify payers of any error, and request a new form marked “corrected.” If tax was withheld (26.10), claim this tax as a payment on your tax return. The IRS will check interest reported on your return against the Forms 1099-INT sent by banks and other payers. If you earn over $1,500 of taxable interest, you list the payers of interest on Part I of Schedule B if you file either Form 1040 or Form 1040A. Form 1040EZ may not be used if your taxable interest exceeds $1,500. You must also list tax-exempt interest on your return even though it is not taxable.

You must report interest that has been shown on a Form 1099-INT in your name although it may not be taxable to you. For example, you may have received interest as a nominee or as accrued interest on bonds bought between interest dates. In these cases, list the amounts reported on Form 1099 along with your other interest income on Schedule B (Form 1040 or Form 1040A). On a separate line, label the amount as “Nominee distribution,” or “Accrued interest” (4.15), and subtract it from the total interest shown. Accrued interest is discussed below. Nominee distributions are discussed below under “Joint Accounts.”

If you received interest on a frozen account (4.13), include the interest from Form 1099 on Schedule B if you file Form 1040, or on Schedule 1 if you use Form 1040A. On a separate line, write “frozen deposits” and subtract the amount from the total interest reported.

You generally do not have to list the payers of interest if your interest receipts are $1,500 or less. However, complete Part I of Schedule B if you have to reduce the interest shown on Form 1099 by nontaxable amounts such as accrued interest, tax-exempt interest, nominee distributions, frozen deposit interest, amortized bond premium, or excludable interest on savings bonds used for tuition.

Joint accounts. Form 1099-INT will be sent to the joint owner whose name and Social Security number was reported to the bank (or other payer) on Form W-9 when the account was opened. If you receive a Form 1099-INT for interest on an account you own with someone other than your spouse, you should file a nominee Form 1099-INT with the IRS to indicate that person’s share of the interest, together with Form 1096 (“Transmittal of Information Return”). Give a copy of the Form 1099-INT to the other person. When you file your own return, you report the total interest shown on Form 1099-INT and then subtract the other person’s share so you are taxed only on your portion of the interest; see the Example below.

Do not follow this procedure if you contributed all of the funds and set up the joint account merely as a “convenience” account to allow the other person to automatically inherit the account when you die. In this case, you report all of the interest income.

Savings certificates, deferred interest. The interest element on certificates of deposit and similar plans of more than one year is treated as deferred interest original issue discount (OID) and is taxable on an annual basis. The bank notifies you of the taxable OID amount on Form 1099-OID. If you discontinue a savings plan before maturity, you may have a loss deduction for forfeited interest, which is listed on Form 1099-INT or Form 1099-OID (4.16).

Tax on interest can be deferred in some cases on a savings certificate with a term of one year or less. Interest is taxable in the year it is available for withdrawal without substantial penalty. Where you invest in a six-month certificate before July 1, the entire amount of interest is paid by the end of the year and is taxable in that year (the year of payment). However, when you invest in a six-month certificate after June 30, only interest actually paid or made available for withdrawal before the end of the year without substantial penalty is taxable in the year of issuance. The balance is taxable in the year of maturity. You can defer interest to the following year by investing in a six-month certificate after June 30, provided the payment of interest is specifically deferred to the year of maturity by the terms of the certificate. Similarly, interest may be deferred to the following year by investing in longer term certificates of up to one year, provided that the crediting of interest is specifically deferred until the year of maturity.

Accrued interest on a bond bought between interest payment dates. Interest accrued between interest payment dates is part of the purchase price of the bond. This amount is taxable to the seller as explained in 4.15. If you purchased a bond and received a Form 1099-INT that includes accrued interest on a bond, include the interest on Line 1 of Schedule B, Form 1040, and then on a separate line above Line 2 subtract the accrued interest from the Line 1 total.

Custodian account of a minor (Uniform Transfers to Minors Act). The interest is taxable to the child if his or her name and Social Security number were provided to the payer on Form W-9. However, if the child has net investment income for 2017 over $2,100, the “kiddie tax” (24.2) probably applies, in which case the excess over $2,100 is subject to tax at the parent’s top tax rate.

4.13 Interest on Frozen Accounts Not Taxed

If you have funds in a bankrupt or insolvent financial institution that freezes your account by limiting withdrawals, you do not pay tax on interest allocable to the frozen deposits. The interest is taxable when withdrawals are permitted. Officers and owners of at least a 1% interest in the financial institution, or their relatives, may not take advantage of this rule and must still report interest on frozen deposits.

On Part I of Schedule B (Form 1040 or Form 1040A), report the full amount shown on Form 1099-INT, even if the interest is on a “frozen” deposit. Then, on a separate line, subtract the amount allocable to the frozen deposit from the total interest shown on the Schedule; label the subtraction “frozen deposits.” Thus, the interest on the frozen deposit is not included on the line of your return showing taxable interest.

Refund opportunity. If you reported interest on a frozen deposit on a tax return for a prior year, you generally have three years to file a refund claim for the tax paid on the interest (47.2).

4.14 Interest Income on Debts Owed to You

You report interest earned on money that you loan to another person. If you are on the cash basis, you report interest in the year you actually receive it or when it is considered received under the “constructive receipt rule.” If you are on the accrual basis, you report interest when it is earned, whether or not you have received it.

See 4.31 for minimum interest rates required for loans and 4.18 when OID rules apply.

Where partial payment is being made on a debt, or when a debt is being compromised, the parties may agree in advance which part of the payment covers interest and which covers principal. If a payment is not identified as either principal or interest, the payment is first applied against interest due and reported as interest income to the extent of the interest due.

Interest income is not realized when a debtor gives you a new note for an old note where the new note includes the interest due on the old note.

If you give away a debtor’s note, you report as income the collectible interest due at the date of the gift. To avoid tax on the interest, the note must be transferred before interest becomes due.

4.15 Reporting Interest on Bonds Bought or Sold

When you buy or sell bonds between interest dates, interest is included in the price of the bonds. If you are the buyer, you do not report as income the interest that accrued before your date of purchase. The seller reports the accrued interest. Reduce the basis of the bond by the accrued interest reported by the seller. The following Examples illustrate these rules.

Redemptions, bankruptcy, reorganizations. On a redemption, interest received in excess of the amount due at that time is not treated as interest income but as capital gain.

Taxable interest may continue on bonds after the issuer becomes bankrupt, if a guarantor continues to pay the interest when due. The loss on the bonds will occur only when they mature and are not redeemed or when they are sold below your cost. In the meantime, the interest received from the guarantor is taxed.

Bondholders exchanging their bonds for stock, securities, or other property in a tax-free reorganization, including a reorganization in bankruptcy, have interest income to the extent the property received is attributable to accrued but unpaid interest; see Internal Revenue Code Section 354(a)(2)(B).

Bonds selling at a flat price. When you buy bonds with defaulted interest at a “flat” price, a later payment of the defaulted interest is not taxed. It is a tax-free return of capital that reduces your cost of the bond. This rule applies only to interest in default at the time the bond is purchased. Interest that accrues after the date of your purchase is taxed as ordinary income.

4.16 Forfeiture of Interest on Premature Withdrawals

Banks usually impose an interest penalty if you withdraw funds from a savings certificate before the specified maturity date. You may lose interest if you prematurely withdraw funds in order to switch to higher paying investments, or if you need the funds for personal use. In some cases, the penalty may exceed the interest earned so that principal is also forfeited to make up the difference.

If you are penalized, you must still report the full amount of interest credited to your account. However, on Form 1040, you may deduct the full amount of the penalty, forfeited principal as well as interest. The deductible penalty amount is shown in Box 2 of Form 1099-INT sent to you. You may claim the deduction even if you do not itemize deductions. On Form 1040, enter the deduction on Line 30, marked “Penalty on early withdrawal of savings.”

Loss on redemption before maturity of a savings certificate. If you redeem a long-term (more than one year) savings certificate for a price less than the stated redemption price at maturity, you are allowed a loss deduction for the amount of original issue discount (OID) reported as income but not received. The deductible amount is shown in Box 3 of Form 1099-OID. Claim the deduction on Line 30 of Form 1040. The basis of the obligation is reduced by the amount of the deductible loss.

Do not include in the computation any amount based on a fixed rate of simple or compound interest that is actually payable or is treated as constructively received at fixed periodic intervals of one year or less.

4.17 Amortization of Bond Premium

Bond premium is the extra amount paid for a bond in excess of its principal or face amount when the value of the bond has increased due to falling interest rates. The premium is included in your basis in the bond but if the bond pays taxable interest, you may elect to amortize the premium by deducting it over the life of the bond. Amortizing the premium annually is usually advantageous because it gives an annual deduction to offset the interest income from the bond. Basis of the bond is reduced by the amortized premium. If you claim amortization deductions and hold the bond to maturity, basis is reduced by the entire amortized premium and you have neither gain nor loss at redemption.

You may not claim a deduction for a premium paid on a tax-exempt bond. However, you must still reduce your basis in the bond by the annual amortization amount. The amortized amount also reduces the amount of tax-exempt interest that you report on your return (4.24).

Dealers in bonds may not deduct amortization but must include the premium as part of cost.

Capital loss alternative to amortizing premium. If you do not elect to amortize the premium on a taxable bond, you will realize a capital loss when the bond is redeemed at par or you sell it for less than you paid for it. For example, you bought a $1,000 corporate bond for $1,300 and did not amortize the $300 premium; you will realize a $300 capital loss when the bond is redeemed at par: $1,000 proceeds less $1,300 cost basis ($1,000 face value plus $300 premium). You could realize a capital gain if you sell the bond for more than the premium price you paid.

Determining the amortizable amount for the year. For a taxable "covered" bond issued by a corporation, the amount of premium amortization allocable to the interest payments will be reported by the payer in Box 11 of Form 1099-INT unless (1) the interest reported in Box 1 has been reduced to reflect the offset of the interest by the allocable premium amortization, or (2) you provided written notice to the payer that you did not want to amortize the bond premium. For example, if the taxable interest from a "covered" corporate bond is $40 and the amount of bond premium amortization allocable to the interest is $4, the payer may either report the net interest of $36 in Box 1 and $0 in Box 11, or report the $40 of interest income in Box 1 and the $4 of allocable premium amorization in Box 11.

For a U.S. Treasury bond that is "covered," Box 12 of Form 1099-INT will show the amount of bond premium amortization allocable to the interest paid during the year, unless the net amount of interest is reported in Box 3 to reflect the offset of the interest by the allocable amortization.

If a taxable bond is "noncovered," the payer is required to report only the gross amount of interest in Box 1 of Form 1099-INT.

The annual amortizable premium is based on the constant yield method (this has been the method for all bonds issued after September 27, 1985). The constant yield method is also an option for reporting market discount (4.20). See IRS Publication 550 for details on figuring the amortizable premium or consult a tax professional for making the complex computations.

For taxable bonds subject to a call before maturity, the amortization computation is based on the earlier call date if that results in a smaller amortization deduction.

Electing amortization—either in or after the year you acquire a bond. An election to amortize premium on a taxable bond does not have to be made in the year you acquire the bond. Attach a statement to the tax return for the first year to which you want the election to apply. If the election is made after the year of acquisition, the premium allocable to the years prior to the year of election is not amortizable; the unamortized amount is included in your cost basis for the bond and will result in a capital loss when the bond is redeemed at par or sold prior to maturity for less than basis.

How to deduct amortized premium on taxable bonds. The premium amortization for such bonds offsets your interest income from the bonds; see the Filing Tip in this section. Any excess of the allocable premium over interest income may be fully deducted as a miscellaneous deduction (not subject to the 2% floor) on Line 28 of Schedule A (Form 1040). However, the miscellaneous deduction is limited to the excess of total interest inclusions on the bonds in prior years over total bond premium deductions in the prior years.

Effect of amortization election on other taxable bonds you acquire. If you elect to amortize the premium for one bond, you must also amortize the premium on all similar bonds owned by you at the beginning of the tax year, and also to all similar bonds acquired thereafter. An election to amortize may not be revoked without IRS permission. If you file your return without claiming the deduction, you may not change your mind and make the election for that year by filing an amended return or refund claim.

Callable bonds. On taxable bonds, amortization is based either on the maturity or earlier call date, depending on which date gives a smaller yearly deduction. This rule applies regardless of the issue date of the bond. If the bond is called before maturity, you may deduct as an ordinary loss the unamortized bond premium in the year the bond is redeemed.

Convertible bonds. A premium paid for a convertible bond that is allocated to the conversion feature may not be amortized; the value of the conversion option reduces basis in the bond.

Premium on tax-exempt bonds. You may not take a deduction for the amortization of a premium paid on a tax-exempt bond. However, you must still reduce your basis in the bond each year by the amortized amount. The amortization for the year also reduces the amount of tax-exempt intetrest otherwise reportable on Line 8b of Form 1040. If the tax-exempt bond is a "covered" security, the payer of the bond must report in Box 13 of Form 1099-INT the amount of premium amortization that is allocable to the annual interest payments, unless the tax-exempt interest reported in Box 8 of the Form 1099-INT is the net amount (Box 9 if the tax-exempt interest is subject to alternative minimum tax), reflecting the offset of the interest paid by the allocable premium.

When you dispose of the bond, you reduce the basis of the bond by the amortized premium for the period you held the bond amount. If the bond has call dates, the IRS may require the premium to be amortized to the earliest call date.

4.18 Discount on Bonds

There are two types of bond discounts: original issue discount and market discount.

Market discount. Market discount arises when the price of a bond declines because its interest rate is less than the current interest rate. For example, a bond originally issued at its face amount of $1,000 declines in value to $900 because the interest payable on the bond is less than the current interest rate. The difference of $100 is called market discount. The tax treatment of market discount is explained in 4.20.

Original issue discount (OID). OID arises when a bond is issued for a price less than its face or principal amount. OID is the difference between the principal amount (redemption price at maturity) and the issue price. For publicly offered obligations, the issue price is the initial offering price to the public at which a substantial amount of such obligations were sold. All obligations that pay no interest before maturity, such as zero coupon bonds, are considered to be issued at a discount. For example, a bond with a face amount of $1,000 is issued at an offering price of $900. The $100 difference is OID.

Generally, part of the OID must be reported as interest income each year you hold the bond, whether or not you receive any payment from the bond issuer. This is also true for certificates of deposit (CDs), time deposits, and similar savings arrangements with a term of more than one year, provided payment of interest is deferred until maturity. OID is reported to you by the issuer (or by your broker if you bought the obligation on a secondary market) on Form 1099-OID (4.19).

Exceptions to OID. OID rules do not apply to: (1) obligations with a term of one year or less held by cash-basis taxpayers (4.21); (2) tax-exempt obligations, except for certain stripped tax-exempts (4.26); (3) U.S. Savings Bonds; (4) an obligation issued by an individual before March 2, 1984; and (5) loans of $10,000 or less from individuals who are not professional money lenders, provided the loans do not have a tax avoidance motivation.

Bond bought at premium or acquisition premium. You do not report OID as ordinary income if you buy a bond at a premium. You buy at a premium where you pay more than the total amount payable on the bond after your purchase, not including qualified stated interest. When you dispose of a bond bought at a premium, the difference between the sale or redemption price and your basis is a capital gain or loss (4.17).

If you do not pay more than the total due at maturity, you do not have a premium, but there is “acquisition premium” if you pay more than the adjusted issue price. This is the issue price plus previously accrued OID but minus previous payments on the bond other than qualified stated interest. The acquisition premium reduces the amount of OID you must report as income; see 4.19.

4.19 Reporting Original Issue Discount on Your Return

The issuer of the bond (or your broker) will make the Original Issue Discount (OID) computation and report in Box 1 of Form 1099-OID the OID for the actual dates of your ownership during the calendar year. In most cases, the entire OID must be reported as interest income on your return. However, the amount shown in Box 1 of Form 1099-OID may have to be adjusted if you bought the bond at an acquisition premium and generally must be adjusted if you bought the bond at a premium, the bond is indexed for inflation, the obligation is a stripped bond or stripped coupon (including zero coupon instruments backed by U.S. Treasury securities), or if you received Form 1099-OID as a nominee for someone else. Your basis in the bond is increased by the OID included in income.

If you did not receive a Form 1099-OID, contact the issuer or check IRS Publication 1212 for OID amounts.

Treasury inflation-indexed securities. You must report as OID any increase in the inflation-adjusted principal amount of a Treasury inflation-indexed security that occurs while you held the bond during the tax year. This amount should be reported to you in Box 1 of Form 1099-OID, but this amount must be adjusted if during the year you bought the bond after original issue or sold it. The adjusted amount of OID must be computed using the coupon bond method discussed in IRS Publication 1212.

Periodic interest (non-OID) paid to you during the year on a Treasury inflation-indexed security may be reported to you either in Box 2 of Form 1099-OID or in Box 3 of Form 1099-INT.

Premium. If you paid a premium (4.18) for a bond originally issued at discount, you do not have to report any OID as income. Report the amount shown on Form 1099-OID and then subtract it as discussed in the Filing Tip in this section.

Acquisition premium. If you pay an acquisition premium (4.18) and the payer reports the gross amount of OID in Box 1 of Form 1099-OID, that amount will not be correct because such premium reduces the amount of OID you must report as interest income. However, for a newly acquired bond, the payer may either (1) report in Box 1 a net amount of OID that reflects the offset of OID by the amortized acquisition premium for the year, or (2)report the gross amount of OID in Box 1 and show in Box 6 the acquisition premium amortization for the year; the Box 6 amount reduces the OID that you must report as interest income.

If you are reporting less than the full Box 1 amount of OID, report the full amount and then reduce it, as discussed in the Filing Tip in this section.

Stripped bonds or coupons. The amount that is shown in Box 1 of Form 1099-OID may not be correct for a stripped bond or coupon (4.22). If it is incorrect, adjust it following the rules in Publication 1212.

Nominee. If you receive a Form 1099-OID for an obligation owned by someone else, other than your spouse, you must file another Form 1099-OID for that owner. The OID computation rules shown in IRS Publication 1212 should be used to compute the other owner’s share of OID. You file the other owner’s Form 1099-OID and a transmittal Form 1096 with the IRS, and give the other owner a copy of the Form 1099-OID. On your own tax return, report the amount shown on the Form 1099-OID you received and then reduce it, as discussed in the Filing Tip in this section.

Periodic interest reported on Form 1099-OID. If in addition to OID there is regular interest payable on the bond, such interest will be reported in Box 2 of Form 1099-OID. However, for a Treasury inflation-indexed security, the interest may be reported in Box 3 of Form 1099-INT. Report the full amount as interest income if you held the bond for the entire year. If you acquired the bond or disposed of it during the year, figure the interest allocable to your ownership period (4.15).

REMICS. If you are a regular interest holder in a REMIC (real estate mortgage investment conduit), Box 1 of Form 1099-OID shows the amount of OID you must report on your return and Box 2 includes periodic interest other than OID. If you bought the regular interest at a premium or acquisition, the OID shown on Form 1099-OID must be adjusted as discussed above. If you are a regular interest holder in a single-class REMIC, Box 2 also includes your share of the REMIC’s investment expenses. These expenses should be listed in a separate statement and are deductible on Schedule A as a miscellaneous itemized deduction subject to the 2% of adjusted gross income floor (19.1).

4.20 Reporting Income on Market Discount Bonds

Market discount arises where the price of a bond declines below its face amount because it carries an interest rate that is below the current rate of interest.

When you realize a profit on the sale of a market discount bond, the portion of the profit equal to the accrued discount must be reported as ordinary interest income rather than as capital gain. Alternatively, an election may be made to report the accrued market discount annually instead of in the year of disposition; see below for “Reporting discount annually”.

These rules apply to taxable as well as tax-exempt bonds bought after April 30, 1993. However, there are these exceptions: (1) bonds with a maturity date of up to one year from date of issuance; (2) certain installment obligations; and (3) U.S. Savings Bonds. Furthermore, you may treat as zero any market discount that is less than one-fourth of one percent (.0025) of the redemption price multiplied by the number of full years after you acquire the bond to maturity. Such minimal discount will not affect capital gain on a sale.

Deferral of interest deduction and ordinary income at disposition if you borrow to buy or carry market discount bonds. If you do not elect to report the accrued market discount annually as interest income (see below for “Reporting discount annually”), and you took a loan to buy or carry a market discount bond, your interest deductions may be limited. If your interest expense exceeds the income earned on the bond (including OID income, if any), the excess may not be currently deducted to the extent of the market discount allocated to the days you held the bond during the year. The allocation of market discount is based on either the ratable accrual method or constant yield method; see below.

In the year you dispose of the bond, you may deduct the interest expenses that were disallowed in prior years because of the above limitations.

You may choose to deduct disallowed interest in a year before the year of disposition if you have net interest income from the bond. Net interest income is interest income for the year (including OID) less the interest expense incurred during the year to purchase or carry the bond. This election lets you deduct any disallowed interest expense to the extent it does not exceed the net interest income of that year. The balance of the disallowed interest expense is deductible in the year of disposition.

How to figure accrued market discount. If the election to report market discount annually is not made, gain on a market discount bond is taxed as ordinary interest income to the extent of the market discount accrued to the date of sale. There are two methods for figuring the accrued market discount. The basic method, called the ratable accrual method, is figured by dividing market discount by the number of days in the period from the date you bought the bond until the date of maturity. This daily amount is then multiplied by the number of days you held the bond to determine your accrued market discount; see Example 1 below.

Instead of using the ratable accrual method to compute accrual of market discount, you may elect to figure the accrued discount for any bond under an optional constant yield (economic accrual) method. If you make the election, you may not change it. The constant yield method initially provides a smaller accrual of market discount than the ratable method, but it is more complicated to figure. It is generally the same as the constant yield method used in IRS Publication 1212 to compute taxable OID (4.19). For accruing market discount, treat your acquisition date as the original issue date and your basis for the market discount bond (immediately after you acquire it) as the issue price when applying the formula in Publication 1212.

Reporting discount annually. Rather than report market discount in the year you sell the bond, you may elect, in the year you acquire the bond, to report market discount currently as interest income. You may use either the ratable accrual method, as in Example 3 below, or the elective constant yield method discussed earlier. If you notified the payer that you are electing to report the market discount currently, the payer may include the annual accrued discount in Box 5 of Form 1099-OID. Attach to your timely filed return a statement that you are making the election and describe the method used to figure the accrued market discount. Your election to report annually applies to all market discount bonds that you later acquire. You may not revoke the election without IRS consent. If the election is made, the interest deduction deferral rule discussed earlier does not apply. Furthermore, the election could provide a tax advantage if you sell the bond at a profit and you can benefit from lower tax rates applied to net long-term capital gains.

Partial principal payments on bonds acquired after October 22, 1986. If the issuer of a bond (acquired by you after October 22, 1986) makes a partial payment of the principal (face amount) and you did not elect to report the discount annually, you must include the payment as ordinary interest income to the extent it does not exceed the accrued market discount on the bond. See IRS Publication 550 for options on determining accrued market discount. A taxable partial principal payment reduces the amount of remaining accrued market discount when figuring your tax on a later sale or receipt of another partial principal payment.

Market discount on a bond originally issued at a discount. A bond issued at original issue discount may later be acquired at a market discount because of an increase in interest rates. If you acquire at a market discount a bond with OID, the market discount is the excess of: (1) the issue price of the bond plus the total original issue discount includible in the gross income of all prior holders of the bond over (2) what you paid for the bond.

Exchanging a market discount bond in corporate mergers or reorganizations. If you hold a market discount bond and exchange it for another bond as part of a merger or other reorganization, the new bond is subject to the market discount rules when you sell it. However, under an exception, market discount rules will not apply to the new bond if the old market discount bond was issued before July 19, 1984, and the terms and interest rates of both bonds are identical.

4.21 Discount on Short-Term Obligations

Short-term obligations (maturity of a year or less from date of issue) may be purchased at a discount from face value. If you are on the cash basis, the discount on short-term obligations other than tax-exempt obligations must be reported as interest income in the year the obligations are sold or redeemed unless you elect to include the accrued discount in income currently.

Discount must be currently reported by dealers and accrual-basis taxpayers. Discount allocable to the current year must be reported as income by accrual-basis taxpayers, dealers who sell short-term obligations in the course of business, banks, regulated investment companies, common trust funds, certain pass-through entities, and for obligations identified as part of a hedging transaction. Current reporting also applies to persons who separate or strip interest coupons from a bond and then retain the stripped bond or stripped coupon; the accrual rule applies to the retained obligation.

For short-term nongovernmental obligations, OID is generally taken into account instead of acquisition discount, but an election may be made to report the accrued acquisition discount. See IRS Publication 550 for details.

Basis in the obligation is increased by the amount of acquisition discount (or OID for nongovernmental obligations) that is currently reported as income.

Interest deduction limitation for cash-basis investors. A cash-basis investor who borrows funds to buy a short-term discount obligation may not fully deduct interest on the loan unless an election is made to report the accrued acquisition discount as income. If the election is not made, the interest you paid during the year is deductible only to the extent it exceeds (1) the portion of the discount allocated to the days you held the bond during the year, plus (2) the portion of interest not taxable for the year under your method of accounting. Any interest expense disallowed under this limitation is deductible in the year in which the obligation is disposed of.

The interest deduction limitation does not apply if you elect to include in income the accruable discount under the ratable accrual method or constant yield method (4.20). The election applies to all short-term obligations acquired during the year and also in all later years.

Gain or loss on disposition of short-term obligations for cash-basis investors. If you have a gain on the sale or exchange of a discounted short-term governmental obligation (other than tax-exempt local obligations), the gain is ordinary income to the extent of the ratable share of the acquisition discount received when you bought the obligation. Follow the computation shown in the discussion of Treasury bills (4.27) to figure this ordinary income portion. Any gain over this ordinary income portion is short-term capital gain; a loss would be a short-term capital loss.

Gain on short-term nongovernmental obligations is treated as ordinary income up to the ratable share of OID. The formula for figuring this ordinary income portion is similar to the formula for short-term governmental obligations (4.27), except that the denominator of the fraction is days from original issue to maturity, rather than days from acquisition. A constant yield method may also be elected to figure the ordinary income portion. Gain above the computed ordinary income amount is short-term capital gain (Chapter 5). For more information, see IRS Publication 550.

4.22 Stripped Coupon Bonds and Stock

Brokers holding coupon bonds may separate or strip the coupons from the bonds and sell the bonds or coupons to investors. Examples include zero-coupon instruments sold by brokerage houses that are backed by U.S. Treasury bonds.

The U.S. Treasury also offers its version of zero coupon instruments, with the name STRIPS, which are available from brokers and banks.

Brokers holding preferred stock may strip the dividend rights from the stock and sell the stripped stock to investors.

If you buy a stripped bond or coupon, the spread between the cost of the bond or coupon and its higher face amount is treated as original issue discount (OID). This means that you annually report a part of the spread as interest income. For a stripped bond, the amount of the original issue discount is the difference between the stated redemption price of the bond at maturity and the cost of the bond. For a stripped coupon, the amount of the discount is the difference between the amount payable on the due date of the coupon and the cost of the coupon. The rules for figuring the amount of OID (4.19) to be reported annually are in IRS Publication 1212.

If you strip a coupon bond, interest accrual and allocation rules prevent you from creating a tax loss on a sale of the bond or coupons. You are required to report interest accrued up to the date of the sale and also add the amount to the basis of the bond. If you acquired the obligation after October 22, 1986, you must also include in income any market discount that accrued before the date you sold the stripped bond or coupons. The method of accrual depends on the date you bought the obligation; see IRS Publication 1212. The accrued market discount is also added to the basis of the bond. You then allocate this basis between the bond and the coupons. The allocation is based on the relative fair market values of the bond and coupons at the date of sale. Gain or loss on the sale is the difference between the sales price of the stripped item (bond or coupons) and its allocated basis. Furthermore, the original issue discount rules apply to the stripped item which you keep (bond or coupon). Original issue discount for this purpose is the difference between the basis allocated to the retained item and the redemption price of the bond (if retained) or the amount payable on the coupons (if retained). You must annually report a ratable portion of the discount.

4.23 Sale or Retirement of Bonds and Notes

Gain or loss on the sale, redemption, or retirement of debt obligations issued by a government or corporation is generally capital gain or loss.

A redemption or retirement of a bond at maturity must be reported as a sale on Schedule D of Form 1040 (5.8) although there may be no gain or loss realized.

The accrued amount of OID is reported annually as interest income (4.19) and added to basis; this includes the accrued OID for the year the bond is sold. If the bonds are sold or redeemed before maturity, you realize capital gain for the proceeds over the adjusted basis (as increased by accrued OID) of the bond, provided there was no intention to call the bond before maturity. If at the time of original issue there was an intention to call the obligation before maturity, the entire OID that has not yet been included in your income is taxable as ordinary income; the balance is capital gain.

Market discount on bonds is taxable under the rules in 4.20.

Tax-exempts. See 4.26 for discount on tax-exempt bonds.

Obligations issued by individuals. If you hold an individual’s note issued after March 1, 1984, for over $10,000, accrued OID must be reported annually (4.19) and added to basis. Gain on your sale of the note is subject to the rules discussed above for corporate and government OID bonds.

If the note is $10,000 or less (when combined with other prior outstanding loans from the same individual), OID is not reported annually provided you are not a professional lender and tax avoidance was not a principal purpose of the loan. On a sale of the note at a gain, your ratable share of the OID is taxed as ordinary income; any balance is capital gain. A loss is a capital loss.

4.24 State and City Interest Generally Tax Exempt

Generally, you pay no tax on interest on bonds or notes of states, cities, counties, the District of Columbia, or a possession of the United States. This includes bonds or notes of port authorities, toll road commissions, utility services activities, community redevelopment agencies, and similar bodies created for public purposes. Bonds issued after June 30, 1983, must be in registered form for the interest to be tax exempt. Interest on federally guaranteed obligations is generally taxable, but see exceptions in 4.25.

Check with the issuer of the bond to verify the tax-exempt status of the interest.

Tax-exempt interest must be reported on your return. If you are required to file a federal return, you must report the amount of your tax-exempt interest although it is not taxable. On Form 1040 and on Form 1040A, you list the tax-exempt interest on Line 8b. On Form 1040EZ, you write “TEI” and then the amount of tax-exempt interest to the right of the last word on Line 2, but do not include it in the taxable interest shown on Line 2.

Private activity bonds. Interest on so-called private activity bonds is generally taxable (4.25), but there are certain exceptions. For example, interest on the following “qualified bonds” is tax exempt even if the bond may technically be in the category of private activity bonds: qualified student loan bonds; exempt facility bonds, including New York Liberty bonds, Gulf Opportunity Zone bonds, Midwestern disaster and Hurricane Ike area bonds, and enterprise zone facility bonds; qualified small issue bonds; qualified mortgage bonds and qualified veterans’ mortgage bonds; qualified redevelopment bonds; and qualified 501(c)(3) bonds issued by charitable organizations and hospitals. Check with the issuer for the tax status of a private activity bond.

AMT treatment. Tax-exempt interest on qualified private activity bonds issued after August 7, 1986 and before 2009, or on bonds issued after 2010, is generally treated as a tax preference item subject to alternative minimum tax (AMT, 23.2), but there are exceptions. The AMT does not apply to interest on qualified 501(c)(3) bonds, New York Liberty bonds, Gulf Opportunity Zone bonds, Midwestern disaster and Hurricane Ike disaster area bonds, and exempt facility, qualified mortgage, and qualified veterans’ bonds issued after July 30, 2008.

The interest on any qualified bond issued in 2009 or 2010 is not subject to AMT.

4.25 Taxable State and City Interest

Interest on certain state and city obligations is taxable. These taxable obligations include federally guaranteed obligations, mortgage subsidy bonds, private activity bonds, and arbitrage bonds.

Federally guaranteed obligations. Interest on state and local obligations issued after April 14, 1983, is generally taxable if the obligation is federally guaranteed, but there are exceptions allowing tax exemptions for obligations guaranteed by the Federal Housing Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, Bonneville Power Authority, Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, Federal National Mortgage Association, Government National Mortgage Corporation, Resolution Funding Corporation, and Student Loan Marketing Association.

Mortgage revenue bonds. Interest on bonds issued by a state or local government after April 24, 1979, may not be tax exempt if funds raised by the bonds are used to finance home mortgages. There are exceptions for certain qualified mortgage bonds and veterans’ bonds. Check on the tax-exempt status of mortgage bonds with the issuing authority.

Private activity bonds. Generally, a private activity bond is any bond where more than 10% of the issue’s proceeds are used by a private business whose property secures the issue, or if at least 5% of the proceeds (or $5 million if less) are used for loans to parties other than governmental units. Interest on such bonds is generally taxable, but there are exceptions (4.24). Check on the tax status of the bonds with the issuing authority.

4.26 Tax-Exempt Bonds Bought at a Discount

Original issue discount (OID) on tax-exempt obligations is not taxable, and on a sale or redemption, gain attributed to OID is tax exempt. Gain attributed to market discount is capital gain or ordinary income depending on whether the bond was purchased before May 1, 1993, or on or after that date; see below.

Original issue discount tax-exempt bond. This arises when a bond is issued for a price less than the face amount of the bond. The discount is considered tax-exempt interest. Thus, if you are the original buyer and hold the bond to maturity, the entire amount of the discount is tax free. On a disposition of a tax-exempt bond issued after September 3, 1982, and acquired after March 1, 1984, you must add to basis accrued OID before determining gain or loss. OID must generally be accrued using a constant yield method; see IRS Publication 1212.

Market discount tax-exempts. A market discount arises when a bond originally issued at not less than par is bought at below par because its market value has declined. If before May 1, 1993, you bought at a market discount a tax-exempt bond which you sell for a price exceeding your purchase price, the excess is capital gain. If the bond was held long term, the gain is long term. A redemption of the bond at a price exceeding your purchase price is similarly treated.

However, for market discount tax-exempt bonds purchased after April 30, 1993,market discount is treated as ordinary income (4.20). If you do not report the accrued market discount as taxable interest income each year you own the bond, any gain when you sell the bond is treated as interest income to the extent of the market discount (4.20).

Stripped tax-exempt obligations. OID is not currently taxed on a stripped tax-exempt bond or stripped coupon from the bond if you bought it before June 11, 1987. However, for any stripped bond or coupon you bought or sold after October 22, 1986, OID must be accrued and added to basis for purposes of figuring gain or loss on a disposition. Furthermore, if you bought the stripped bond or coupon after June 10, 1987, part of the OID may be taxable; see Publication 1212 for figuring the tax-free portion.

4.27 Treasury Bills, Notes, and Bonds

Interest on securities issued by the federal government is fully taxable on your federal return. However, interest on federal obligations is not subject to state or local income taxes. Interest on Treasury bills, notes, and bonds is reported on Form 1099-INT.

Treasury bonds and notes. Treasury notes have maturities of two, three, five, seven or 10 years. Treasury bonds have maturities of 30 years. Interest on notes and bonds is paid every six months and is taxable when received on your federal return. Treasury bonds and notes are capital assets; gain or loss on their sale, exchange, or redemption is reported as capital gain or loss on Form 8949 and Schedule D (Chapter 5). If you purchased a federal obligation below par (at a discount), see 4.19 for the rules on reporting original issue discount. If you purchased a Treasury bond or note above par (at a premium), you may elect to amortize the premium (4.17). If you do not elect to amortize and you hold the bond or note to maturity, you have a capital loss.

Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS). These pay interest semiannually at a fixed rate on a principal amount that is adjusted to take into account inflation or deflation. The interest is taxable when received and any increase in the inflation-adjusted principal amount while you hold the bond must be reported as original issue discount (OID) (4.19). Your basis in the bond is increased by the OID included in income. On a sale or redemption before maturity, any gain is generally capital gain, but if there was an intention to call before maturity, gain is ordinary income to the extent of the previously unreported OID(4.23).

Treasury bills. These are short-term U.S. obligations with maturities of four weeks, 13 weeks, 26 weeks, or 52 weeks. On a bill held to maturity, you report as interest income the difference between the discounted price and the amount you receive on a redemption of the bills at maturity.

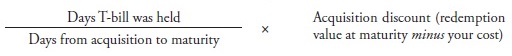

Treasury bills are capital assets and a loss on a disposition before maturity is taxed as a capital loss. If you are a cash-basis taxpayer and have a gain on a sale or exchange, ordinary income is realized up to the amount of the ratable share of the discount received when you bought the obligation. This amount is treated as interest income and is figured as follows:

Any gain over this amount is capital gain; see the Example below. Instead of using the above fractional computation for figuring the ordinary income portion of the gain, an election may be made to apply the constant yield method. This method follows the OID computation rules shown in IRS Publication 1212 for obligations issued after 1984, except that the acquisition cost of the Treasury bill would be treated as the issue price in applying the Publication 1212 formula.

Accrual-basis taxpayers and dealers who are required to currently report the acquisition discount element of Treasury bills using either the ratable accrual method or the constant yield method (4.20) do not apply the above formula on a sale before maturity. In figuring gain or loss, the discount included as income is added to basis.

Interest deduction limitation. Interest incurred on loans used to buy Treasury bills is deductible by a cash-basis investor only to the extent that interest expenses exceed the following: (1) the portion of the acquisition discount allocated to the days you held the bond during the year; and (2) the portion of interest not taxable for the year under your method of accounting. The deferred interest expense is deductible in the year the bill is disposed of. If an election is made to report the acquisition discount as current income under the rules for governmental obligations (4.21), the interest expense may also be deducted currently. The election applies to all future acquisitions.

4.28 Interest on United States Savings Bonds

Savings Bond Tables: The e-Supplement at www.jklasser.com will contain redemption tables showing the 2017 year-end values of Series EE bonds and Series I bonds.

EE Bonds. Series EE bonds may be cashed for what you paid for them plus an increase in their value over their 30-year maturity period. See the discussion of the interest accrual and redemption rules for U.S. Savings Bonds (30.12).

The increase in redemption value is taxable as interest, but you do not have to report the increase in value each year on your federal return. You may defer (4.29) the interest income until the year in which you cash the bond or the year in which the bond finally matures, whichever is earlier. But if you want, you may report the annual increase by merely including it on your tax return. If you use the accrual method of reporting, you must include the interest each year as it accrues. Savings bond interest is not subject to state or local taxes.

If you initially choose to defer the reporting of interest and later want to switch to annual reporting, you may do so. You may also change from the annual reporting method to the deferral method. See 4.29 for rules on changing reporting methods.

Series I bonds. “I bonds” are inflation-indexed bonds issued at face amount (30.13). As with EE bonds, you may defer the interest income (the increase in redemption value each year is interest) until the year in which the bond is redeemed or matures in 30 years, whichever is earlier (4.29).

Education funding. If you buy EE or I bonds to pay for educational expenses and you defer the reporting of interest (4.29), you may be able to exclude the accumulated interest from income when you redeem the bonds (33.4).

Bonds registered only in name of child. Interest on U.S. savings bonds bought for and registered in the name of a child will be taxed to the child, even if the parent paid for the bonds and is named as beneficiary. Unless an election is made to report the increases in redemption value annually, the accumulated interest will be taxable to the child in the year he or she redeems the bond, or if earlier, when the bond finally matures. The kiddie tax (24.2) may apply to a portion of the annually reported interest or to interest on redeemed bonds. For example, if a child under age 18 has 2017 investment income over $2,100, the excess is taxed at the parent’s top tax rate on the child’s 2017 return (24.2). To avoid kiddie tax, savings bond interest may be deferred (4.29).

Bonds must be reissued to make gift. Assume you have bought I or EE bonds and had them registered in joint names of yourself and your daughter. The law of your state provides that jointly owned property may be transferred to a co-owner by delivery or possession. You deliver the bonds to your daughter and tell her they now belong to her alone. According to Treasury regulations, this is not a valid gift of the bonds. The bonds must be surrendered and reissued in your daughter’s name. For the year of reissue, you must include in your income all of the interest earned on the bonds other than interest you previously reported.

If you do not have the bonds reissued and you die, the bonds are taxable to your estate. Ownership of the bonds is a matter of contract between the United States and the bond purchaser. The bonds are nontransferable. A valid gift cannot be accomplished by manual delivery to a donee unless the bonds also are surrendered and registered in the donee’s name in accordance with Treasury regulations.

Series E bonds. There are no Series E bonds still earning interest. The last E bonds, those issued in June 1980, reached final maturity in June 2010, 30 years from the date of issue.

Series HH. These bonds were available after 1979 and before September 1, 2004, in exchange for E or EE bonds, or for Freedom Shares. They were issued at face value and pay semiannual interest that is taxable when received. They mature in 20 years.

Series H. These bonds were available before 1980 and they reached final maturity 30 years later. If you obtained Series H bonds in an exchange for Series E bonds, and you did not report the E bond interest annually, the accumulated interest on the E bonds became taxable when the H bonds were redeemed or, if earlier, when the H bonds reached final maturity 30 years from issue.

4.29 Deferring United States Savings Bond Interest

You do not have to make a special election on your tax return in order to defer the interest on Series EE or I savings bonds. You may simply postpone reporting the interest until the year you redeem the bond or the year in which it reaches final maturity, whichever is earlier. If you choose to defer the interest, you may decide in a later year to begin reporting the increase in redemption value each year as interest, but this election applies to all the EE and I bonds you own. You may also switch from annual reporting to the deferral method. You must use the same method—deferral or annual reporting—for all of your EE and I bonds. These options are discussed in this section.

Changing from deferral to annual reporting. If you have deferred reporting of interest (the annual increases in redemption value) and want to change to annual reporting starting with your 2017 return, you must report on your 2017 return all interest accrued through 2017 on all your EE and I bonds. Then, starting in 2018, you report the interest accruing each year on all of your bonds, including bonds you acquired after the 2017 election. Suppose you do not change from the deferral method to the annual method on your 2017 return and later wish you had. If the due date of the return has passed, it is too late to make the election. You may not file an amended return for 2017 to report the accrued interest. You have to wait until next year’s return to make the election.

Changing from annual reporting to deferral. If you have been reporting annual increases in redemption value as interest income, you may change your method and elect to defer interest reporting until the bonds mature or are redeemed. You make the election by attaching a statement to your federal income tax return for the year of the change; see IRS Publication 550 for details.

Co-Owners. How to report interest on a Series EE or I bond depends on how it was bought or issued:

- You paid for the entire bond: Either you or the co-owner may redeem it. You are taxed on all the interest, even though the co-owner cashes the bond and you receive no proceeds. If the other co-owner does cash in the bond, he or she will receive a Form 1099-INT reporting the accumulated interest. However, since that interest is taxable to you, the co-owner should give you a nominee Form 1099-INT, as explained in the rules for joint accounts in 4.12.

- You paid for only part of the bond: Either of you may redeem it. You are taxed on that part of the interest which is in proportion to your share of the purchase price. This is so even though you do not receive the proceeds.

- You paid for part of the bond, and then had it reissued in another’s name. You pay tax only on the interest accrued while you held the bond. The new co-owner picks up his or her share of the interest accruing afterwards.

Changing the form of registration. Changing the form of registration of an I or EE bond may result in tax. Assume you use your own funds to purchase a bond issued in your name, payable on your death to your son. Later, at your request, a new bond is issued in your son’s name only. The increased value of the original bond up to the date it was redeemed and reissued in your son’s name is taxed to you as interest income.

As shown in the Examples below, certain changes in registration do not result in an immediate tax.