CHAPTER 11

Public Charities

- 11.1 Distinctions between Public and Private Charities

- 11.2 “Inherently Public Activity” and Broad Public Support: §509(a)(1)

- 11.3 Community Foundations

- 11.4 Service-Providing Organizations: §509(a)(2)

- 11.5 Difference Between §509(a)(1) and §509(a)(2)

- 11.6 Supporting Organizations: §509(a)(3)

- 11.7 Testing for Public Safety: §509(a)(4)

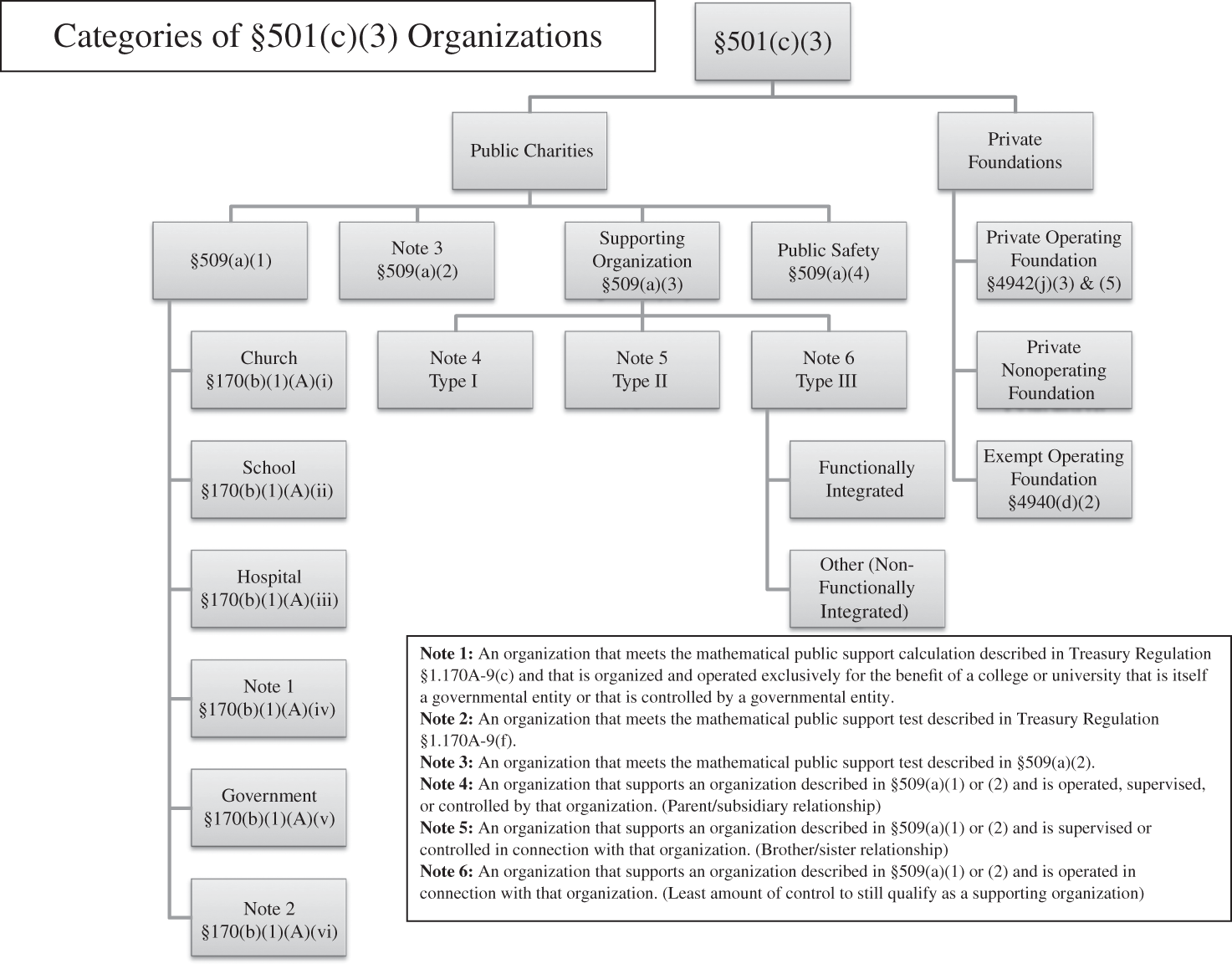

The significance of “public charity” status for organizations tax exempt under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §501(c)(3) is multifaceted and is of utmost importance to both private and public exempt organizations. Knowing the meaning of the four parts of IRC §509 is the key to understanding public charities. All §501(c)(3) organizations, other than those listed in §509(a)(1), (2), (3), and (4), are private foundations and are subject to the operational constraints outlined in Chapters 12 through 17. The specific requirements of each of the §509 categories are described in this chapter. Briefly, the four categories of public charities are:

- §509(a)(1) organizations engaging in inherently public activity and those that receive revenues from the general public.

- §509(a)(2) organizations whose revenue stems primarily from charges for exempt function services.

- §509(a)(3) organizations that support another public charity.

- §509(a)(4) organizations that test for public safety.

11.1 Distinctions between Public and Private Charities

Private foundations (PFs) must comply with a variety of special rules and sanctions. The allowable contribution deductions for gifts to PFs are less than those afforded for public charities. It is useful for a charitable organization, when possible, to obtain and maintain public status. The important attributes of PFs, compared to public charities, are summarized in Exhibit 11.1. Exhibit 11.2 illustrates the different categories of organizations exempt under §501(c)(3). The comparison between public charities and private foundations is reflected therein.

- The deduction for contributions by individuals to PFs is limited to 30 percent of the donor's adjusted gross income (AGI) for cash gifts and 20 percent for appreciated property gifts.1 Up to 60 percent of a donor's AGI can be deducted for cash gifts to public charity, and 30 percent for gifts of appreciated property. To illustrate, assume that a generous taxpayer with an income of $1 million wants to annually give $500,000 in cash for charitable pursuits. Only $300,000 of the annual gift is deductible if it is given to a private foundation. The full $500,000 is deductible if it is given to a public charity.)

- The value of appreciated property, such as land, closely held company stock, artworks, or a partnership interest, is not deductible when the property is donated to a private nonoperating foundation. Only the basis of such property may be deductible.2 The full fair market value of stocks for which market quotations are readily available on an established securities market is deductible. The maximum amount of the deduction, however, is limited to 20 percent of the donor's adjusted gross income.3 (A full 30 to 60 percent of income can potentially be sheltered with gifts of most types of property to a public charity and private operating foundation.)

EXHIBIT 11.1 Differences Between Public and Private Charitable Organizations

Charitable Deduction Excise Tax Activities Minimum Distribution Requirements Annual Filings Private Foundations Limited to 30% of AGI* for cash and qualified appreciated stock gifts

Other property limited to 20% and donor's tax basis2% of investment income

5–15% of amount of disqualified transactions

UBI** taxedGrants to other organizations

Limits on grants to other PFs

Self-initiated projects

No lobbying5% of average fair market value of investment or nonexempt function assets All must file Form 990-PF Private Operating Foundations Limited to 30% for appreciated property, 60% for cash gifts Same as for PFs Spends MRQ† on self-initiated projects

(but may also make grants)3⅓% fair market value investment assets or 85% of adjusted net income Same as for private foundations Public Charities Same as for private operating foundation No tax on income (except UBI)

Excise tax on excess lobbying and intermediate sanctionsCan lobby

Grant-making or carry out own projectsNone, unless excess accumulation of surplus File Form 990-N if gross revenue < $50,000

Form 990-EZ if < $250,000 or Form 990 if $250,000 or above* Adjusted gross income.

** Unrelated business income.

† Required minimum distribution

EXHIBIT 11.2 Different Categories of Organizations Exempt Under §501(c)(3)

- An excise tax of 1 or 2 percent must be paid on a PF's investment income.4 (There is no tax on investment income for a public charity.)

- A PF cannot buy or sell property, nor enter into financial transactions (called self-dealing) with its directors, officers, contributors, or their family members, under most circumstances.5 (Public charities can have business dealings with their insiders, within limits, subject to reasonableness standards. If excessive salaries or purchase prices are paid to an insider, intermediate standards may be imposed.)6

- Annual returns must be filed by all PFs regardless of support levels and value of assets. (Public organizations with gross annual revenue less than $50,000 merely file an electronic Form 990-N with six items of information.)7

- Fund-raising between PFs is constrained by expenditure responsibility requirements that prohibit one private foundation from giving to another without contractual agreements and follow-up procedures.8 (No such similar restrictions are imposed on grants paid from one public charity to another.)

- Absolutely no lobbying activity by PFs is permitted.9 (A limited amount of lobbying is permitted for public charities under two different systems for measuring permissible amount.)10 Absolutely no political activity is permitted for either public or private charities.

- A PF's annual spending for grants to other organizations and charitable projects must meet a “minimum distribution” requirement.11 (A public charity has no specific spending requirement, other than those imposed by its funders.)12

- Holding more than 20 percent of a business enterprise, including shares owned by board members and contributors, is prohibited for PFs, as are jeopardizing investments.13 (No such limits are placed on public charities by the tax code, although fiduciary responsibility standards apply.)14

11.2 “Inherently Public Activity” and Broad Public Support: §509(a)(1)

A wide variety of organizations qualify as public charities under IRC §509(a)(1). The (a)(1) category includes all those organizations tax exempt under IRC §501(c)(3) that are described in IRC §170(b)(1)(A)(i)–(vi), which lists organizations eligible to receive deductible charitable contributions. The definition is complicated and rather unwieldy because it includes six distinctly different types of exempt entities. Because of the code's design, the categories are labeled according to the IRC section subdivisions (e.g., (c)(3)).

The first five categories include those organizations that perform what the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) calls “inherently public activity.”15 The first three achieve public status because of the nature of their activities without regard to sources of the funds with which they pay their bills—even if they are privately supported. The fourth and fifth are closely connected with governmental support and activities. Last, but certainly not least, because it includes a wide variety of charities, the sixth category includes those organizations balancing their budgets with donations from a sizeable group of supporters, such as the United Way, American Red Cross, governmental bodies, and many donors. They must meet a mathematically measured and contribution-based formula and can be referred to as donative public charities. A consideration of the rules that pertain to both donative public charities and service provider entities is important to understanding public charities. A comparison of the differences between the categories can be found in §11.5.

(i) 60-Month Termination Issues

A private foundation (PC) that seeks future recognition as a public charity can request a 60-month termination period to achieve that goal by filing Form 8940.[1] This change is appropriate and possible when the PC begins to receive support from a sufficient number of donors that is can satisfy the 33-13% support test for donative public charities.[2] This type of change is not an “advance ruling” described above in §11.1(f). For any year during the 60-month conversion in which the PF fails to meet the public support test, the private foundation sanctions will apply, including the §4940 excise tax on its investment income and the § 4941 sanctions on self-dealing transactions as discussed in Chapter 18.3.

(a) Churches

The first category includes a “church, convention, or association of churches.”16 Churches are narrowly defined, and not all religious organizations are eligible to be classified as churches. Chapter 3 is devoted to these distinctions. Perhaps due to the need to separate church and state, neither the Internal Revenue Code nor the IRS regulations define a church.17

(b) Schools

Although the title of the IRS category does not say “school,” the second category basically includes formal schools. A school is an “educational organization that normally maintains a regular faculty, has a regular curriculum, and normally has a regularly enrolled body of pupils or students in attendance at the place where its educational activities are regularly carried on.”18 The IRS very strictly scrutinizes what are referred to as the “four regulars” in granting classification as a school. Note that the world of educational organizations for purposes of IRC §501(c)(3) is much broader.19

(c) Hospitals and Medical Research Organizations

This class of public charity includes hospitals, the principal purpose or function of which is to provide medical or hospital care, medical education, or medical research. An organization directly engaged in continuous, active medical research in conjunction with a hospital may also qualify if, during the year in which the contribution is made, the funds are committed to be spent within five years.

Medical care includes the treatment of any physical or mental disability or condition, on an inpatient or outpatient basis. A rehabilitation institution, outpatient clinic, or community mental health or drug treatment center may qualify. Convalescent homes, homes for children or the aged, handicapped vocational training centers, and medical schools are not considered to be hospitals.20 An animal clinic was also found not to be a hospital.21 The issues involved in qualifying for tax exemption as a hospital may evolve, and close attention must be paid to the latest information.22

Medical research is the conduct of investigations, experiments, and studies to discover, develop, or verify knowledge relating to the causes, diagnosis, treatment, prevention, or control of physical or mental diseases and impairments of human beings. Appropriate equipment and qualified personnel necessary to carry out its principal function must be regularly used. The disciplines spanning the biological, social, and behavioral sciences, such as chemistry, psychiatry, biomedical engineering, virology, immunology, biophysics, and associated medical fields, must be studied.23 Such organizations must conduct research directly. Granting funds to other organizations, while possible, may not be a primary purpose.24 The rules governing a research organization's expenditure of funds and its endowment levels are complicated, and the regulations must be studied to understand this type of public charity. A participant in a joint venture is considered to conduct the activity of the venture. Tax-exempt participants in a whole-hospital joint venture may be treated as providers of hospital care for purposes of qualification as a public charity under IRC §170(b)(1)(A)(iii).25

(d) College and University Support Organizations

An entity operating to receive, hold, invest, and administer property and to make expenditures to or for the benefit of a state or municipal college or university qualifying under §170(b)(1)(A)(ii) is a public charity. Such entities must normally meet the 33⅓ percent test, which means they receive a substantial part of their support from governmental grants and contributions from the general public, rather than from exempt function and investment revenues.

(e) Governmental Units

The United States, District of Columbia, states, possessions of the United States, and their political subdivisions are classified as governmental units. They are listed as qualifying as public charities, although they are not actually tax exempt under §501(c)(3). They are, in essence, public charities because they are responsive to all citizens. The tax code, in §170(c)(1), permits a charitable contribution deduction for gifts to governmental units. The regulations contain no additional definition or explanation of the meaning of this term, but IRS rulings and procedures and the courts have provided some guidance.26

(f) Donative Public Charities: §170(b)(1)(a)(vi)

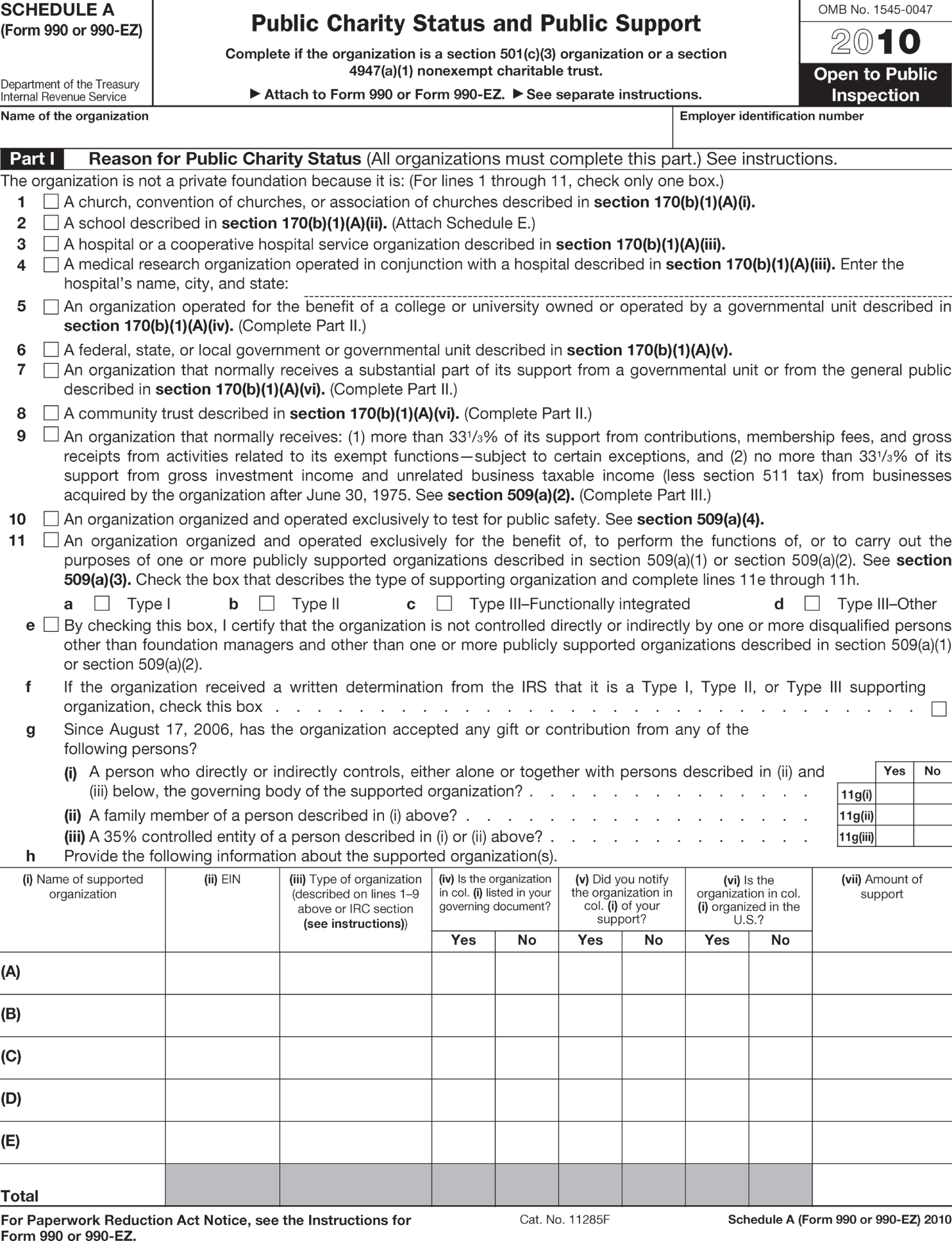

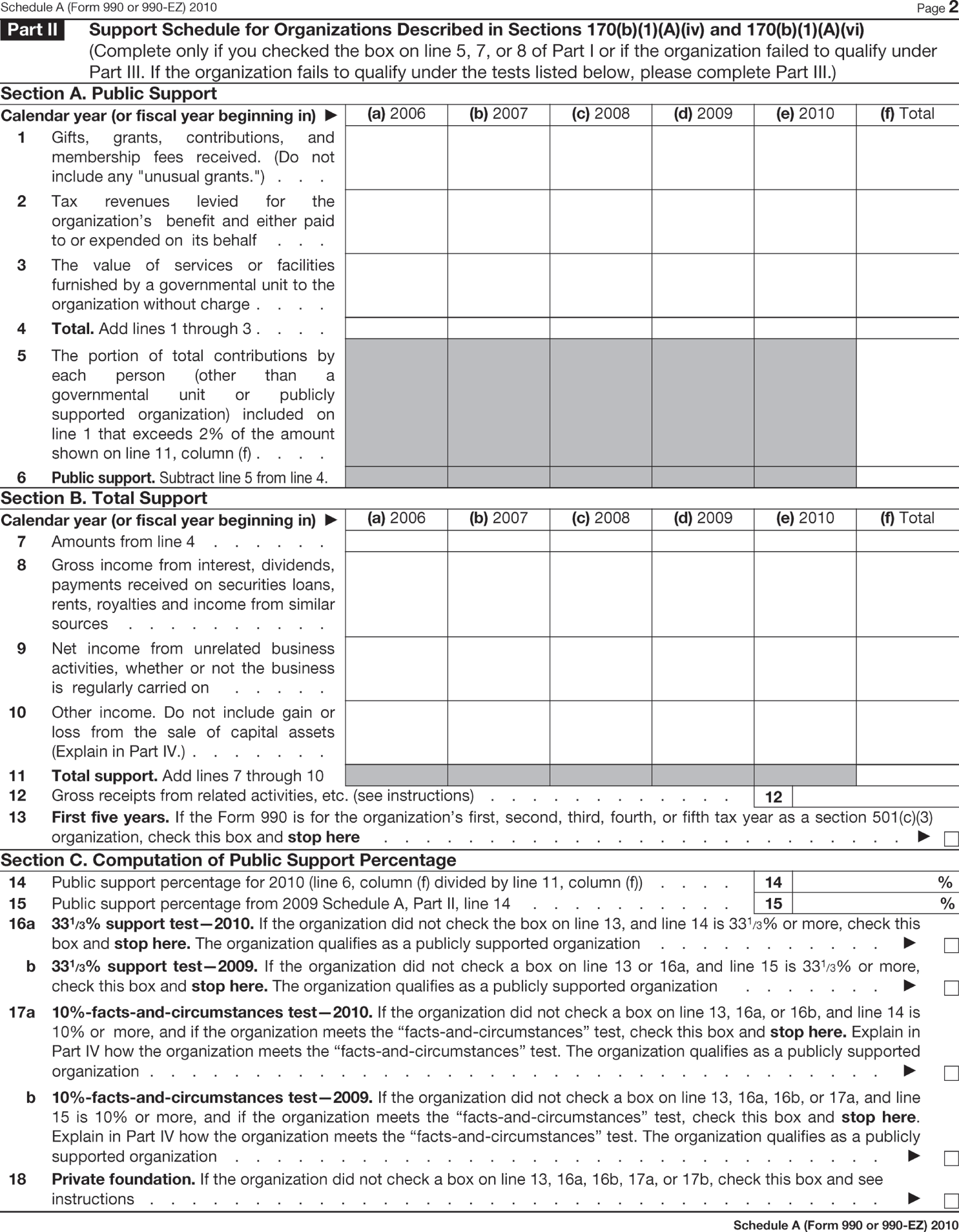

Public charities in this category are called “donative public charities” because to qualify they must receive at least 33⅓ percent of their annual support in the form of donations from members of the general public (not including fees and charges for performing exempt functions).27 The calculation is based on a five-year period including the current and past four years; before 2008, the test covered four years. If the organization achieves at least 33⅓ percent public support for the current year, it is treated as a public charity for that year and the following year. If it fails this test in the current year but passes it in the following year, it can continue to be treated as public. If it fails the test two years in a row, the organization is reclassified as a private foundation for the second year and must file Form 990-PF rather than Form 990. Checkboxes on lines 14 and 15 of Part II of Schedule A (shown in Exhibit 11.3) request the percentage to indicate whether the entity passed or failed. An entity with a lower than 33⅓% result can consider seeking qualification under the “facts-and-circumstances” test28 or by excluding unusual grants.29

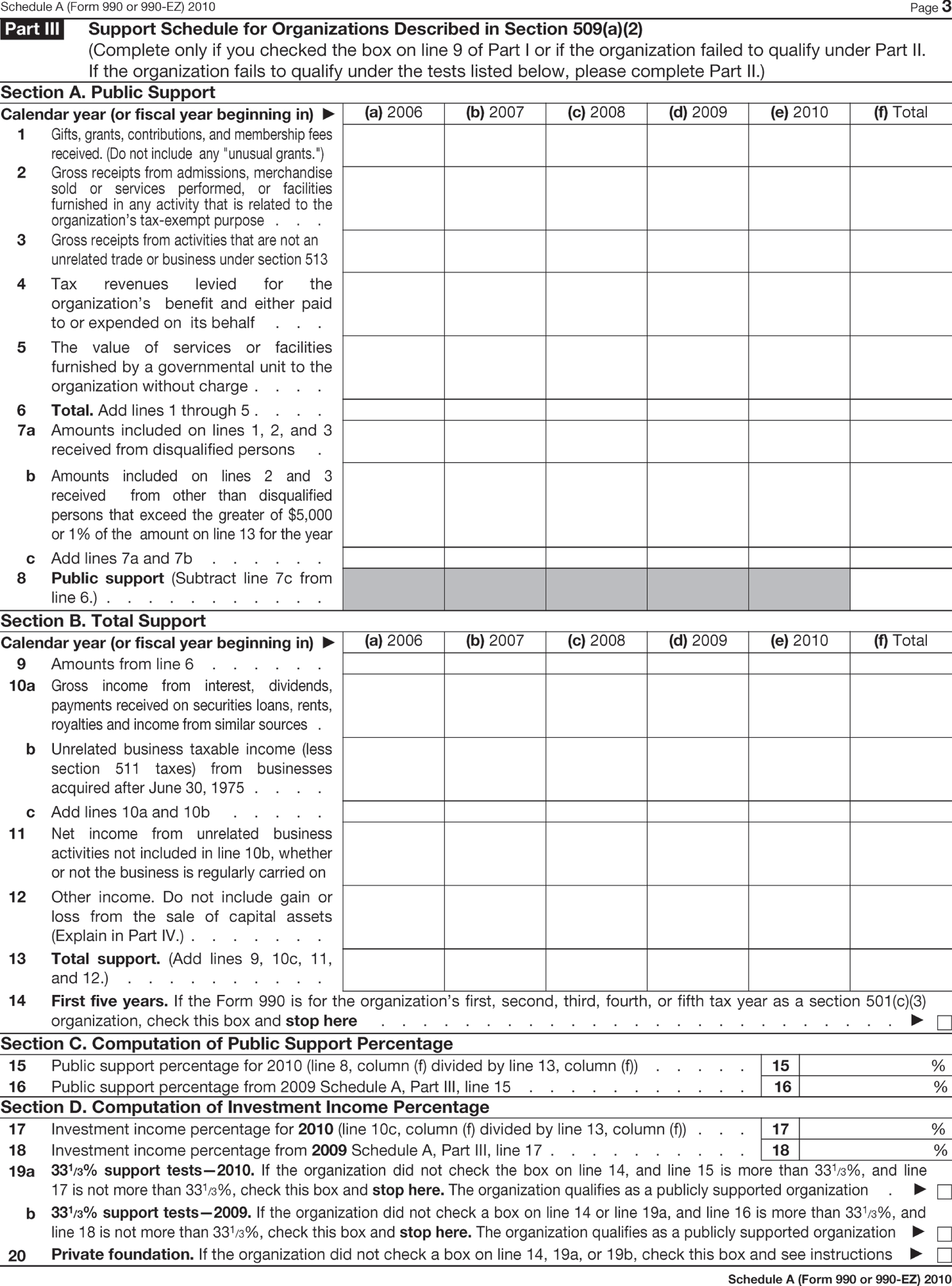

EXHIBIT 11.3 Form 990 Schedule A

To implement the five- rather than four-year public support test, effective October 9, 2008, new standards were adopted.30 The mathematical tests are calculated following the organization's regular accounting method: either cash or accrual. Organizations that report on an accrual basis for tax purposes faced a major challenge that year to correctly convert cash-basis revenue reported for 2006 and 2007 to accrual.

In another significant change intended to streamline the IRS approval processes, the advance-ruling-period system under which new organizations were issued a tentative five-year period of classification as a public charity was eliminated. If the information submitted in the initial application for exemption, Form 1023, establishes to the satisfaction of the IRS that the organization can reasonably be expected to meet a public-support test, the IRS will issue a determination letter stating that the organization qualifies as publicly supported for its first five years as a §501(c)(3) organization and is classified as a public charity. This status continues for the entity's first five years, regardless of the level of public support it in fact receives during this period. The filing of Form 8734 is no longer required. Instead, information provided in Schedule A is the support information used to determine ongoing qualification as a public charity.

The organization will not owe any §4940 tax or §507 termination tax with respect to its first five years regardless of whether it eventually qualifies as publicly supported.31 Beginning with the organization's sixth year, a lack of adequate support or governance structure to qualify as a public charity will cause it to become a private foundation and liable for the §4940 excise tax and other Chapter 42 sanctions applicable to private foundations for that year and any future year for which it cannot establish that it is not a private foundation.32

During an organization's first five years, a box is checked to indicate no support percentages need be reported. Filing of Form 8734 was eliminated; the last filers were those organizations with advance ruling periods ending before June 9, 2008. A new determination letter is not provided, but can be requested by calling 1-877-829-5500. The IRS admits that donors may not be willing to accept a determination letter reflecting an advance ruling period, but advises that such donors should refer to IRS Publication 78; alternatively, the FAQ section advises that donors can call the same Customer Account Services number.

Because an organization that cannot meet a public support test for the current taxable year is at risk of private foundation classification as of the first day of the subsequent taxable year (if it fails the test for that year), organizations should carefully monitor their public support calculations. The IRS and the Treasury Department recognize that an organization may not be able to compute its public support for the current taxable year until sometime in the subsequent taxable year.

Organizations that believe that the imposition of private foundation excise taxes and/or penalties against them for all or part of the first year in which they are reclassified as a private foundation would be unfair or inequitable should contact the IRS, Exempt Organizations, Rulings and Agreements, Washington, DC, at 1-202-283-4905. An organization will be required to provide to the IRS all of the relevant facts and circumstances establishing that imposition of private foundation taxes would be unfair or inequitable due to events beyond the organization's control.

Many agree that the public support test is overly complex and should be simplified. The level of noncompliance is significant, and there is often a lack of awareness of the need to maintain historic donor information. At a minimum, keeping a list of the names of and amount given by donors of more than 2 percent of the total contributions for each five-year rolling average period is necessary for a §509(a)(1)/§170(b)(1)(a)(vi) public charity. For §509(a)(2) entities, a permanently updated list should be maintained for substantial contributors and vendors.33 This is particularly true for modest organizations that file Form 990-N, which has no display of public support to be prepared for a future year in which Form 990-EZ or 990 must be filed and support information reported.

Support. The 33⅓ percent support formula for donative public charities does not include revenue the organization receives from performing its exempt activities (student tuition or patient fees, for example), unlike the formula for §509(a)(2) service-providing organizations, which does include such revenue.34 Donations of services for which a contribution deduction is not allowed35 are also excluded. Grants from other donative (§509(a)(1)) public charities and governmental entities are fully included in the numerator and denominator for this test, but other types of donations are partly or fully excluded, as next explained. An organization that is primarily dependent on exempt function revenues may qualify as a donative public charity,36 but only if it receives more than an insignificant amount of donations from governmental units and the general public.

Sponsorship payments that are acknowledged by the tax-exempt organization with no quantitative and qualitative information to avoid classification as advertising revenue can be treated as contributions for public support purposes.37

The amount reported as a contribution of noncash property, such as an art object or real estate, is the fair market value of the property for both financial and Form 990 tax purposes.38 The charitable contribution standards limit the deduction for gifts of certain property to the donor's tax basis if it is less than the value.39 Gifts of inventory, intellectual property, food, and more have varying limitations. In a ruling regarding a donation of software, the IRS said that “notwithstanding that a donor's charitable contribution deduction is limited by §170(e)(3),” the full fair market value of such gifts is includible in calculating the public charity support test.40

Two Percent Gifts. There is a 2 percent ceiling for donations treated as public support under this test. Contributions from each donor, whether an individual, corporation, trust, private foundation, or other type of entity (after combining related parties), during each five-year period are each counted only up to 2 percent of the charity's total support. For example, say an organization receives total support of $1 million during the five-year test period. In such a case, contributions from each donor (including gifts from his or her related parties) of up to $20,000 could be counted as public donations. If one person gave $20,000 each year for a total of $100,000 for five years, only $20,000 is counted as public. The organization must receive at least $333,333 in public donations of $20,000 or less from each donor to satisfy the one-third support test. It could receive $666,666 from one source and $10,000 from 33 sources or $20,000 from 17 sources, for example.

A question arises when the charity receives a donation from a partnership. Is the donor the partnership or the partnership's individual partners? There is no explicit guidance in the code regulations under IRC §509. The partnership rules41 do not allow the partnership to take a charitable contribution deduction, so, logically, a distributive share of the gift should be allocable to each partner.

All contributions made by a donor and by any person or persons standing in relationship to the donor, including businesses, that are described in the code definition of disqualified persons42 must be combined and treated as if made by a single person.43 Under §4946(a)(1)(E), IRC § 4946 stipulates combination of “a corporation of which persons described in subparagraph (A), (B), (C), or (D) own more than 35 percent of the total combined voting power.” An unanswered question in this regard is whether a donation from a private foundation must be combined with donations of that foundation's disqualified persons for this purpose. The regulations don't follow the same alpha labels but indicate:

§ 53.4946–1(a)(5) For purposes of subparagraph (1)(iii)(a) and (v) of this paragraph, the term “combined voting power” includes voting power represented by holdings of voting stock, actual or constructive (under § 4946(a)(3)),but does not include voting rights held only as a director or trustee.

IRC §4946(a)(1)(H) says “only for purposes of § 4943, a private foundation which is (i) effectively controlled directly or indirectly by the same person or persons … or (ii) substantially all of the contributions to which were made by the same person, or members of their families.” The authors expect that a gift by the donor and her PF should be combined for the IRC §509(a)(1) 2 percent limitation purposes, as has been our practice in the past, but do not find guidance on the matter.

For IRC §509(a)(2) purposes, there is no 2 percent test; instead, support from all disqualified persons (DPs) is excluded entirely. There is no requirement that all DPs be combined; rather, the family member of a substantial contributor is also deemed to be a disqualified person.

Grants from Other Charities. Voluntary grants and donations received by a donative public charity from other charities listed in §170(b)(1)(A)(i)–(vi) and from governmental units, not including foreign governments,44 are not subject to the 2 percent limit and instead are fully counted as donations from the general public,45 unless the gift was passed through as a donor-designated grant over which the donor has control.46

It is important to note that the 2 percent limitation on inclusion in the public support test does not apply to grants from organizations described in IRC §170(b)(1)(A)(vi): in other words, such grants are fully counted.47 A grant from those organizations described in §170(b)(1)(A)(i)–(iv) that have sufficient public support to also qualify as donative public charities under §170(b)(1)(A)(vi) is likewise fully counted as public support.48 It is sometimes the case that a service-providing organization classified as a §509(a)(2) public charity is also eligible for classification as a public charity under §170(b)(1)(A)(vi). If this fine distinction makes or breaks an organization's qualification as a publicly supported one, the Forms 990 (or for a church not required to file one, a financial statement) of grantors can be evaluated to ascertain their dual qualification as a donative charity.

A grant from a service-providing entity49 and a grant from a supporting organization are subject to the 2 percent inclusion limitation.50

(g) Facts-and-Circumstances Test

When the percentage of an organization's public donations falls below the precise 33⅓ percent test, it may be able to sustain public charity status by applying the facts-and-circumstances test. The history of the organization's fund-raising efforts and other factors are considered as an alternative method to the strict mathematical formula for qualifying for public support under (a)(1). This test is not available for charities qualifying as public under §509(a)(2). An organization can seek to apply this test to prove it qualifies for public status by submitting the information in the following lists when originally filing Form 1023 or subsequently in submitting the Form 990.

The revised public support test displayed in Schedule A contains a box to check if the organization's public support percentage falls below 33⅓ percent, but is more than 10 percent and the organization can otherwise qualify under the facts-and-circumstances test. Detailed information demonstrating qualification under the facts-and-circumstances exception must provided. To measure ongoing qualification as a public charity, the percentage for the preceding year is shown. The applicant should spare no details evidencing that it meets the test. Brochures, board lists, program descriptions, and fund solicitations can be furnished.

When reviewing Form 1023, the IRS will scrutinize the facts and issue its approval or disapproval. When an organization needs to apply the test later in its life because its support has fallen below the 33⅓ percent level, it submits the calculation and information required by Schedule A of its annual Form 990. It can also choose to file a formal request with the IRS to acknowledge qualification. The problem with only submitting information with Schedule A is that the IRS does not customarily respond to such a filing. Though prior IRS approval is not required, an organization might choose to seek overt approval by submitting the information to the Cincinnati office responsible for determinations, particularly if support has fallen below 33⅓% and the facts- and-circumstances or unusual grant exceptions are used.51

For the facts-and-circumstances test to apply, the following series of factors must be evidenced.52 The first two factors in the following list must be present, and a sufficient number of the other favorable factors must indicate that the organization is responsive to public interests. In the author's experience, control of the board by major contributors or their family members is a major flaw. The factors that are considered are fully explained in the regulations, which should be carefully studied during preparation of information evidencing satisfaction of the test.

- Public support must be at least 10 percent of the total support, and the higher the better.

- The organization must have an active “continuous and bona fide” fund-raising program designed to attract new and additional public and governmental support. Consideration can be given to the fact that, in its early years of existence, the charity limits the scope of its solicitations to those persons deemed most likely to provide seed money in an amount sufficient to enable it to commence its charitable activities and to expand its solicitation program.

- The composition of the board is representative of broad public interests (rather than those of major contributors).

- Some support comes from governmental and other sources representative of the public (rather than a few major contributors).

- Facilities and programs are made available to the public, such as those presented by a museum or symphony society.

- Programs appeal to a broadly based public (and, in fact, the public participates).

- An organization is an educational or research institution that regularly publishes scholarly studies that are widely used by colleges and universities and the public.

- Members of the public having special knowledge or expertise, public officials, or civic or community leaders participate in or sponsor the programs of the organization.

- For a membership organization, the solicitations for dues-paying members are designed to enroll a substantial number of persons in the community or area and the dues amount makes membership available to a broad cross-section of the interested public.

In the author's experience, the IRS seldom questions a claim that fact and circumstances exist to allow a public support percentage of less than 33⅓ percent to qualify for continued qualification as a public charity. Facts to support the position (listed earlier) are submitted with Form 990. No advance approval is required.

A factor not contained in the preceding listed, which appeared in a private letter ruling about application of the facts-and-circumstances test, may cause some confusion. The ruling stated, “You have previously met the one-third support test without the exclusion of any unusual grants. You have never benefited from the use of the exclusion of unusual grants to meet the one-third support test.”53 The regulations clearly permit exclusion of unusual grants from both the numerator and denominator for purposes of making this calculation. This statement may indicate that ongoing claims for different donors will be questioned.54

(h) Unusual Grants

When inclusion of a substantial donation(s) causes an organization to fail the 33⅓ percent public support test, public charity status may still be sustained by excluding such gift(s) for both (a)(1) and (a)(2) purposes. A grant is unusual if it is an unexpected and substantial gift attracted by the public nature of the organization and received from a disinterested party. Factors evidencing “unusualness” follow. No single factor is determinative, and not all factors need be present. The eight positive factors are shown in the following list, along with their opposites in parentheses:55

- The contribution is received from a party with no connection to the organization. (The gift is received from a person who is a substantial contributor, board member, or manager, or is related to one.)

- The gift is in the form of cash, marketable securities, or property that furthers the organization's exempt purposes. (The property is illiquid, difficult to dispose of, and not used or to be used for mission activities.) A gift of a painting to a museum or a gift of wetlands to a nature preservation society would be useful and appropriate property.56

- No material restrictions are placed on the gift. (Strings are attached.)

- The organization attracts a significant amount of support to pay its operating expenses on a regular basis, and the unusual gift adds to an endowment or pays for capital items. (The gift pays for operating expenses and is not added to an endowment.)

- The gift is a bequest. (The gift is an inter vivos transfer.)

- An active fund-raising program exists and attracts significant public support. (Fund solicitation programs are unsuccessful or nonexistent.)

- A representative and broadly based governing body controls the organization. (Related parties control the organization.)

- Prior to the receipt of the unusual grant, the organization qualified as publicly supported. (The unusual grant exclusion was relied on in the past to satisfy the test.)

If the grant is payable over a period of years, it can be excluded each year, but any income earned on the sums would be included.57 The IRS has provided a set of “safe harbor” reliance factors to identify unusual grants. If the first four factors just listed are present, unusual grant status can automatically be claimed and relied on. As to item 4, the terms of the grant cannot provide for more than one year's operating expense.58

A proposed substantial grant by a new donor (Factor #1) to an IRC §509(a)(1) publicly supported organization to enrich lives of at-risk youth and foster children by providing programs that restore and increase self-esteem, self-worth, self-sufficiency, and opportunity for long-term success constituted an “unusual grant” under Reg. §1.170A-9(f)(6)(ii) and related provisions.59

A bequest from an estate (Factor #5), the size of which was unusual compared with the foundation's support levels, would have adversely affected the foundation's status as a public charity. The decedent had not previously contributed a substantial part of the foundation's support (Factors #1 and #8 on the preceding list). The bequest was not burdened with any material restrictions other than the establishment of a fund to benefit public charities (Factor #3).60

A grantor in another ruling did not exercise control over the grantee and was not a disqualified person with respect to it (Factor #1); the prospective grantee had a public solicitation program and a representative governing body (Factors #6 and #7).61

A private foundation operating a sculpture garden, park, and museum had previously used the unusual grant exception (Factor #8). Nonetheless, its request for unusual treatment again (meant not counted in calculation) was approved for a significant donation amount of artwork. It was a public charity (Factor #8) and had an active fund-raising program (Factor #4) and a representative governing body (Factor #7).62

An unusual grant occurred when it was higher than the typical level of support from a new donor (Factor #1) not in a position of authority and in the form of a bequest (Factor #5) without any material restrictions other than that the funds were to benefit specific designated charities (Factor #3). The contribution was in the form of securities, cash, and properties, which were to be sold and the earnings used to benefit the designated charities. The board of directors consisted of 18 community leaders, and the organization had previously met the public support tests (Factors #7 and #8).63

In one last example, the ruling concerned an expected endowment fund bequest in the form of cash or investments. The grant was to be used to benefit community residents at the discretion of the board of directors. One small grant from the testator had been received several years ago. The testator was the organization's creator and did not stand in a position of authority in the organization. The entity had a successful public solicitation program to attract public support and consistently met the public support test. Last, the entity had a large board that included an elected county official, an elected member from the local board of education, and an officer/employee of a local bank from the community, as well as three directors elected at large.

Form 8940, reproduced in §18.4 and issued June 2011, can be submitted to seek approval for claiming that a major grant is an unusual grant. This application requires a fee that readers should verify on instructions to the form. Previously, this recognition required a costly letter ruling. Responses to this form usually come in a month or two, which is also helpful. An organization may not realize it wishes to make a claim that a grant is unusual until it tallies up its finances after year-end and finds that its public support ratio is below 33⅓ percent. Nonetheless, there is potential that the request will not be approved prior to the return filing deadline. This possibility should be anticipated as soon as the gift (cash or pledge) is received.

11.3 Community Foundations

Billions of dollars in charitable assets are held in the United States by public charities called community foundations (CFs) or community trusts. The first such organization was created in 1914 in Cleveland, Ohio—The Cleveland Foundation. Now there are more than 800. The primary purpose of a CF is to raise funds and maintain endowments to support projects benefiting a local community or area. A prototypical CF is controlled by a governing body representing the city or area it serves. It receives a broad base of support from many sources, enabling it to meet the mechanical 33⅓ percent support test or the facts-and-circumstances test.64 The typical CF solicits and receives lifetime and testamentary gifts. It may collect donations in the form of modest gifts from individuals and businesses and from major donors. Some affluent philanthropists want to avoid the administrative costs and the labyrinth of rules applicable in creating and operating an independent private foundation. They instead choose to establish a fund within a community foundation. Such donors often wish to maintain some control over their funds and to designate and restrict the expending of funds. As CFs have evolved through the years, two very different organizational structures are typically used, although a combination of the following may be used:

- Single-Entity: Sole or single nonprofit corporation or trust.

- Component Parts: Composite organization of otherwise taxable trusts, corporations, or unincorporated restricted funds that are treated as a single entity for exemption purposes. New York Community Trust, for example, has several banks acting as its trustees, each holding one or more of its trusts and funds. The IRS says that CFs “are akin to holding companies.”65

The regulations governing CFs create the legal fiction of a single entity and were designed to limit donor control. When more stringent rules were imposed on privately funded charities in 1969, some existing private foundations were collapsed into community foundations.66 CFs also became an attractive vehicle for new entities seeking to avoid the PF rules. Two different regulations refer to such conversions and affect the establishment of a new community foundation.67

Interestingly, the §509 regulation governing CFs refers to community trusts without mention of a corporation. The IRS has addressed qualification of a CF in a combined corporate/trust form.68 In its training literature, the IRS says that “many CFs combine both forms of organization,” but it also admits that the issue is unsettled.69 The IRS fought recognition of one corporate CF, the National Foundation, in 1987 because it felt donors had too much control over their funds.70 Donors were allowed to recommend charitable projects subject to National's acceptance. The standard agreement forms, though, provided that once the donor committed the funds, National fully controlled them and was free to use or not use them as the donor suggested. The IRS argued that National was merely a conduit and provided evidence that National ordinarily honored requests for redistribution of funds without exercising independent judgment about the needs most deserving of support. The court disagreed and approved National's recognition as a charitable and “unitary” organization without mention of the regulation. The Fund for Anonymous Gifts fought a similar challenge because it gave donors not only discretion over grants but also control over investment of assets they contributed.71 Philanthropic Research Inc. (PRI), however, received approval of public charity status for a new donor-advised fund.72 PRI proposed to use the fund to encourage donations to charities appearing on its Guidestar.org website. PRI planned to use due diligence to review recommendations made by donors and retain dominion and control over the donations. This criterion is also used for accounting purposes to determine whether the revenue belongs to the fund or whether the fund simply serves as a pass-through, or agent, for the donations to the suggested recipient charity.73 Although the IRS has recognized their exempt status, funds created by financial institutions, such as the Fidelity Gift Fund, have been carefully scrutinized. Fidelity has imposed an annual distribution requirement on its accounts equivalent to the 5 percent minimum distribution required of private foundations.

Fundamentally, the IRS will apply slightly different tests to determine whether a new CF can qualify for tax-exempt status:

(a) Single-Entity Test

All legally separate entities operating under the aegis of the community foundation and meeting the criteria outlined here are treated as part of a single entity, rather than as separate funds. The individual funds associated with a CF—whether trusts, not-for-profit corporations, unincorporated associations, or a combination thereof—are not treated as separate legal entities for tax purposes. Essentially, they are considered as part of a consolidated group and do not separately apply for recognition or exemption.74

- Name The organization must be commonly known as a community trust, fund, foundation, or other similar name conveying the concept of a capital or endowment fund to support charitable activities in the community or area it serves.

- Common Instrument All funds of the organization must be subject to a common governing instrument or a master trust or agency agreement, which may be embodied in a single or several documents containing common language. Making the component fund subject to the CF's governing instrument in the transfer documents is acceptable.

- Common Governing Body A single or common governing body or distribution committee must control all components. Any restricted funds dedicated to a particular purpose or organization must be monitored by the governing body.

- Power to Modify or Remove The CF's governing body must generally have the power—in the governing instrument, instrument of transfer, bylaws, or other controlling documents—to modify any restriction or condition on the distribution of funds. Particularly when a restriction or condition becomes, in effect, unnecessary, incapable of fulfillment, or inconsistent with the charitable needs of the community or area served, the CF must be able to prevail in disbursing the funds or income therefrom.

- Exercise of Powers There must be a written resolution to replace any participating trustee, custodian, or agent for breach of fiduciary duty under state law. A breach would result when the charitable purposes are jeopardized due to improper disbursements of funds or a failure to produce a reasonable return on assets, for example.

- Common Reports The periodic financial reports must be presented in a consolidated manner treating all funds as CF funds.

The variety of funds cited by the IRS as acceptable examples of component funds that can be offered or maintained within a CF include the following:75

- Unrestricted Funds The CF has unfettered use of these funds—both the income and the principal. No restrictions or conditions on the management or distribution of the moneys can exist. The CF, not the donor, is expected to identify community needs and distribute funds according to those needs.

- Memorial Funds Funds can be named after a particular person, family, private foundation, or historic event or catastrophe.

- Field-of-Interest Funds These funds can be dedicated to a particular charitable need or concern: the arts, the poor, the homeless, higher education, religion, or similar charitable and social concerns. The types of interests for which funds are made available may be broad or narrow and can be designated or requested by the donors. The manner in which the interest is pursued, however, is up to the CF itself (whether to directly conduct a program or re-grant the funds to another organization serving the interest).

- Advised Funds The donor is given the right to make nonbinding suggestions as to the specific organization or projects to receive funding. The CF retains final authority to determine use of its income. See further discussion later in this section regarding limitations on donor designations.

- Designated Funds The donor may specify the charitable purpose(s) or organization(s) to be supported with his or her funds.

- Agency Endowments A designated fund supporting a particular local charity may be established within the CF. The charity solicits donations made payable into the fund for its benefit. Such an agency arrangement may be advantageous to the local charity from an investment management standpoint.

- Pooled-Income Funds The income is paid to the donors during their lives, and upon the donors' death the principal and income are distributed to the CF.

(b) Component-Part Test

Each qualifying component must be created by a gift, bequest, legacy, device, or other transfer to a community trust treated as a single entity, and the gifts may not be directly subjected by the transferor to any material restriction or condition.76 Even if the donor is not a private foundation, the rules applicable to private foundations that make transfers to CFs upon termination apply. A donor may not encumber a fund with a restriction that prevents the CF from “freely and effectively employing the transferred assets, or the income derived therefrom, in furtherance of its exempt purposes.”77 Essentially, the regulations are intended to prevent the creation of pseudo-private foundations under an umbrella CF. The following donor-imposed restrictions are not considered material and are therefore allowed:

- Name The fund may take the name of a private foundation, the fund's creator, or the creator's family.

- Purpose The donor may designate that the income and principal be used for specified charitable purposes or one or more §509(a)(1), (2), or (3) organizations. The CF's governing body must be given the power to stop distributions and recover any funds that were not used for the CF's exempt purposes.

- Administration A separate or identifiable fund may be required by the donor. Distribution of some or all of the principal can be delayed in time.

- Required Retention of Gift A donor may require the CF to keep the property if, because of the property's peculiar features (such as a historic property or wildlife preserve), its retention is important to accomplishing the exempt purposes of the community.

(c) Donor Designations versus Donor Directions

Donors may designate the purposes for which their funds are to be expended before or at the time the gift is made—not later. Reservation of the right to choose grantees or programs (donor direction) is not permitted once the fund is established. Recognizing that moral suasion can be imposed by philanthropists even without written direction, the regulations provide a list of factors indicating that donors have not reserved a right to designate:78

- The CF investigates the donor's advice and its investigation shows that the advice is consistent with specific charitable needs most deserving of support in the community.

- The CF has published guidelines listing the specific charitable needs of the community and the donor's advice is consistent with those guidelines.

- The CF has begun an educational program advising donors and other persons of its guidelines that list the specific charitable needs most deserving of support. These needs must be consistent with its charitable purposes.

- The CF disburses other funds to the same or similar organizations or charitable needs as those recommended by the donor. Other funds are from sources other than, and in excess of, those distributed from the donor's fund.

- The CF's solicitation for funds specifically states that it will not be bound by any advice the donor offers.

Impermissible donor retention of control is evidenced, according to the regulations, by the presence of two or more of the following factors:79

- The only criterion considered by the CF in making a distribution of income or principal from the donor's fund is the donor's advice.

- Solicitations of funds by the CF state or imply that the donor's advice will be followed. Also considered is a pattern of conduct by the CF that creates an expectation that the donor's advice will be followed.

- The donor's advice is limited to distributions of amounts from his or her fund and the CF has not (1) done an independent investigation to evaluate whether the donor's advice is consistent with the charitable needs most deserving of support in the community, or (2) established guidelines that list the specific charitable needs of the community.

- The CF solicits advice regarding distributions from the donor's fund only from the donor, and no procedure is provided for considering advice from others.

- The CF follows the advice of all donors concerning their funds substantially all the time.

A bequest to a community foundation to establish a designated fund to support public charities following the CF's customary procedures was found to be an unusual grant excludable from the calculation of its public support test.80 Of the eight factors listed on this page, the ruling particularly noted that the exclusion was generally intended to apply to the following type of substantial contributions or bequests from disinterested parties:

- Bequest was attracted by reason of the publicly supported nature of the CF.

- Size of the contribution is unusual compared to CF's typical level of support.

- Contribution may, by reason of its size, adversely affect CF's status as normally being publicly supported.

The particular factor noted in the ruling that would have brought a negative ruling was a donor's prior relationship to the organization, evidenced by one of the following facts:

- Donor created the organization,

- Donor had previously contributed substantial support or an endowment,

- Donor stood in position of authority with respect to the organization,

- Donor directly or indirectly exercised control over the organization, or

- Related party of donor possessed the aforementioned characteristics.

Additionally, the ruling noted that the gift was a bequest without any material restrictions other than that the funds were to benefit specific designated charities, that the gift was in the form of marketable securities, that the CF's board of directors consisted of 18 community leaders, and that the CR had previously met the public support tests. In other words, most of the factors on the list were positive.

This ruling is of interest because the regulations refer to the list as a “set of safe-harbor reliance factors” to identify unusual grants without the need for a private ruling.81 See §11.2(h) for discussion of such grants.

(d) Public Support Test

A community foundation must submit each year, on Form 990, complete financial information to calculate its percentage of public support. Part I of Schedule A contains a separate box to identify an organization as a “community trust.” The regulations specifically say that a CF must meet the 33⅓ percent public support test or, if not, the facts-and-circumstances test.82

(e) Impact of Pension Protection Act of 2006

The Pension Protection Act of 2006 (PPA) essentially imposes private foundation–type constraints on advised funds, referred to in the legislation as “donor-advised funds (DAFs).” A DAF is defined, for the first time in the tax code, as a fund or account that:83

- Is separately identified by reference to contributions of a donor or donors.

- Is owned and controlled by a sponsoring organization.

- Is one with respect to which a donor (or any person appointed or designated by such donor) has, or reasonably expects to have, advisory privileges with respect to the distribution or investment amounts held in such fund or account by reason of the donor's status as donor.

The revised code contains rules to prohibit transactions between the DAF and its donors. The fact that the donor did not technically control the advised-fund sponsor previously shielded private benefit transactions between the fund creator and his or her designated fund from intermediate sanction penalties.84 Those rules now provide that an automatic excess benefit occurs as a result of “any grant, loan, compensation, or other similar payment from such fund to a donor and his or her related parties and controlled companies.”85 Note that an automatic excess benefit does not occur with a “payment pursuant to bona fide sale or lease of property.”86 The transaction would, however, have to occur for no more than fair market value to avoid the normal excess benefit penalties.87

A donor-advised fund now makes a “taxable distribution” if it makes a payment to a “natural person,” for a noncharitable purpose, or to a Type III non-functionally integrated supporting organization, private foundation, or other organization that is not a permitted public charity without exercising expenditure responsibility.88 In addition to imposing automatic excess benefit penalties on transactions with donors, the code also prohibits a distribution that provides a more-than-incidental benefit as a result of such distribution to the DAF's donors and imposes a 125 percent tax on such a transaction.89

A benefit is more than incidental if, as a result of a distribution from a DAF, such person receives a benefit that would have reduced or eliminated a charitable contribution deduction if the benefit was received as part of the transaction.90 The private foundation rules on self-dealing provide some clues.91 The tax does not apply if a tax has already been imposed with respect to such distribution under IRC §4958. In addition, a 10 percent excise tax applies to a fund manager who makes a taxable distribution knowing that it is a taxable distribution.

Excess business holding rules also apply to donor-advised funds.92

A payout requirement has not yet been imposed on donor-advised funds. Based on a congressional mandate, the IRS in late 2007 conducted a compliance study of organizations holding DAFs. Statistical information, including number of funds, grants paid out, total assets, type of investments held, nature of policies indicating the organization has dominion and control of the funds, and other operational details were requested and are being compiled. Readers should watch for proposals for new rules based on the results of the study. The questions the IRS must answer are:

- Whether the values of charitable income, estate, and gift tax deductions allowed are appropriate in view of the charitable use of those assets compared to use of assets for the benefit of the donor.

- Whether a minimum distribution requirement is needed for DAFs.

- Whether gifts to DAFs should be treated as “completed gifts” eligible for charitable deduction.

A Guide Sheet was issued August 19, 2008 (exactly two years after the effective date of the Pension Protection Act of 2006) that contained new IRM 7.20.8 on donor-advised funds, which should be carefully studied by persons managing such funds. Issues the IRS will consider in granting exemption to a DAF are addressed. Exhibit 11.4 compares the attributes of donor-advised funds, supporting organizations, and private foundations. Readers should be alert for new developments on proposed regulations issued in Notice 2017-73.

EXHIBIT 11.4 Comparing the Attributes of Donor-Advised Funds, Supporting Organizations, and Private Foundations

| Private Foundation | Donor-Advised Fund | Type III* Supporting Organization | |

| Tax Penalty Provision Issues: | |||

| §4940 Excise Tax on Investment Income | Yes | No | No |

| §4941 Self-Dealing Prohibitions | Yes | Yes** | Yes |

| §4942 Mandatory Annual Spending | Yes | No | Yes*** |

| §4943 Excess Business Holdings | Yes | Yes | Yes**** |

| §4944 Jeopardizing Investments | Yes | No | No |

| §4945 Taxable Expenditures | Yes | Yes***** | No |

| Other Tax Compliance Issues: | |||

| Annual tax return | Yes | No | Yes |

| Anonymity for donor (Sch. B disclosure) | No | Yes | Yes |

| Record-keeping responsibility | Yes | No | Yes |

| Tax deduction 20/30% of AGI | Yes | Higher | Higher |

| Tax deduction 30/60% of AGI | Lower | Yes | Yes |

| Grants to individuals | Yes | No | Yes |

| Expenditure responsibility for grants to non-501(c)(3) organizations | Yes | Yes | No |

* Non-functionally integrated.

** §§4958 and 4967.

*** Prop. Reg. §1.509(a)-4.

**** §4943.

***** §4966.

Notice 2017-73 outlines IRS proposals regarding three important aspects of activity for a donor-advised fund under §4958(f)(7), with a view to defining “incidental benefit” similar to concepts and rules for private foundations,93 also referring to §4958(f)(7) which imposes a tax on excess benefit transactions. Comments included in the notice look at both sides of the issue of “incidental benefit.”

Gala Tickets. Distributions from a DAF that pay for the purchase of tickets that enable a donor, donor advisor, or related person to attend or participate in a charity-sponsored event do result in a more-than-incidental benefit to such person. The Treasury and IRS view of such purchases deems that such payments should be prohibited.

Donor Advisor or Related Person Pledges. Somewhat surprisingly, distributions from a DAF that the distributee charity treats as fulfilling a pledge made by a donor, donor advisor, or related person do not result in a more-than-incidental benefit under §4967. This result was based on a commentator's94 suggestion that determining whether a pledge is legally binding “may unduly complicate charitable giving.” Also, some said that determining whether a pledge is enforceable under state law is inherently difficult with different results in different states. Others noted that determining whether a pledge is enforceable is impractical and imposes an undue administrative burden on the IRS. Thus, in this notice, the Treasury and IRS state their view that, in the context of DAFs, it is best left to the distributee charity which has knowledge of the facts surrounding the pledge.95

Distributions. The Treasury Department and the IRS are “considering developing proposed regulations that would change the public support computation for organizations described in § 170(b)(1)(A)(vi)/§ 509(a)(1) and in § 509(a)(2) to prevent the use of DAFs to circumvent the excise tax rules applicable to private foundations.” DAF-holding organizations, customarily referred to as “community foundations,” receive a broad base of support from many sources, enabling them to meet the mechanical 33⅓ percent public support test.96 A 2 percent test limits inclusion of an individual and his or her related and controlled parties97 in the calculation of public support. Due to the public charity status of the DAF-holding entity, grants from DAFs are treated as unlimited public gifts. The suggestion is whether DAF grants should be attributed to their creators and not treated as a public donation. The suggestion is to combine DAF gifts with those of individual substantial contributors, which would deprive the ultimate recipient of the funds of the ability to qualify as a public charity.

The notice stated that the Treasury Department and the IRS continue to develop proposed regulations that would, if finalized, comprehensively address donor-advised funds. The notice is intended to provide interim guidance on the three specific issues and to solicit additional comments in anticipation of issuance of further guidance.

11.4 Service-Providing Organizations: §509(a)(2)

Like those organizations said to conduct “inherently public” activities—churches, schools, and hospitals—the second major category of public charity includes entities that also provide services to the public: museums, libraries, low-income housing projects, and the like. Unlike churches, schools, and hospitals, which qualify without regard to their sources of support, these service providers must meet public support tests. Also unlike donative public charities that disregard fee-for-service revenue in calculating public support, service providers count exempt function revenues and donations and grants as support. Thus, this category usually includes organizations receiving a major portion of their support from fees and charges for activity participation, such as day care centers, animal shelters, theaters, and educational publishers. If the organization achieves at least support for the current year, it is treated as a public charity for that year and the following year A two-part support test98 must be met to qualify under this category:

- Investment income cannot exceed one-third of the total support. (Total support basically means the organization's gross revenue except for capital gains.) Program-related investments, such as low-income housing loans, do not produce investment income but rather exempt function gross receipts for this purpose.99 Interest income earned on a portfolio of microloans that pay dividend and interest income is gross receipts from exempt function activity, not investment income.100

- More than one-third of the total support must be received from exempt function sources (called “gross receipts”) made up of a combination of the following:

- Gifts, grants, contributions, and membership dues received from nondisqualified persons. Unusual grants can be excluded.101

- Admissions to exempt function facilities or performances, such as theater or ballet performance tickets, museum or historic site admission fees, movie or video tickets, seminar or lecture fees, and athletic event charges.

- Fees for performance of services, such as school tuition, day care fees, hospital room and laboratory charges, psychiatric counseling, testing, scientific laboratory fees, library fines, animal neutering charges, athletic facility fees, and so on.

- Merchandise sales of goods related to the organization's activities, including books and educational literature, pharmaceuticals and medical devices, handicrafts, reproductions and copies of original works of art, byproducts of a blood bank, and goods produced by handicapped workers.

- Exempt function revenues received from one source are not counted if they exceed $5,000 or 1 percent of the organization's support for the year, whichever is higher.

- Unrelated revenue from activity not operated like a “trade or business” is treated as public support including work performed by volunteers, carried on for benefit of members, and sale of donated merchandise.102

This limitation on inclusion of service fees means that an organization performing services for a few contractors may not reach the required 33⅓ percent support level under this test. Consider an organization that studies child abuse cases and receives most of its revenue from two state agencies. Because only 1 percent of each agency's support can be counted, the organization may have as little as 2 percent qualifying support. Such an organization dependent primarily on gross receipts from related activities is precluded from qualifying instead as a §509(a)(1) organization if “it receives an insignificant amount of its support from governmental units and contributions made directly or indirectly by the general public.”103 A second limitation treats payments from disqualified persons as private, rather than public, support.104 This means that gifts and other payments from the organization's trustees and directors, its managers, and substantial contributors cannot be counted as public support. Correct reporting for this test requires identification of substantial contributors.105 To do so, one adds up all the donations given by a person and his or her immediate family throughout the entire life of the organization.

An organization that is primarily dependent on exempt function revenues may also qualify as a donative public charity106 if it receives the required amount of donations from governmental units and the general public.107

11.5 Difference Between §509(a)(1) and §509(a)(2)

Some publicly supported organizations, including most churches, schools, and hospitals, can qualify for public status under both §§509(a)(1) and (a)(2). In such cases, the (a)(1) class may be assigned by the IRS to identify the organization's category of public status. For purposes of annual reporting, unrelated business, limits on deductions for donors, and most other tax purposes, the two categories of public charity are much the same, with two important exceptions. To receive a terminating distribution from a private foundation upon its dissolution and for a grant from it to another charity to be fully counted for public support purposes, the charity must be an (a)(1) organization.108 Additionally, only a grant from another §509(a)(1) organization is treated as public support for a §509(a)(1) organization. The major differences between these two types of public charity will be eliminated if suggestions for simplification of the calculations are implemented.109

(a) Definition of Support

The items of gross income included in the requisite “support” are different for each category and do not necessarily equal total revenue under either class. Calculations for both categories are made on a five-year moving aggregate basis using the organization's normal method of accounting.

For (a)(1) purposes, certain revenues are not counted as support and are not included in the numerator or the denominator:110

- Exempt function revenue, or that amount earned through charges for the exercise or performance of exempt activities, such as admission tickets, patient fees, tuition, and similar fees.

- Capital gains or losses.

- Unusual grants.

- Donations of in-kind services and facilities (do count facility and service donations from governmental units).

For (a)(2) purposes, total revenue, including exempt function revenue, less capital gains or losses, unusual grants, and in-kind service and facility donations equals total support. An increase or decrease in the equity value of an organization's for-profit subsidiary is recognized as revenue for financial statement purposes. Such revenue is essentially capital in nature. The author finds no guidance on the subject and suggests that such revenue is excluded from total support for both §509(a)(1) and §509(a)(2) organizations, but she invites comments.

Schedule A creates two separate five-year calculations for §509(a)(1) and (2) that should eliminate mistakes in the future. Accrual-reporting organizations may be delighted that the calculation no longer requires revenues reported on a cash basis.111 A box to be checked during the advance ruling period instructs the filer to stop short of making the “Public Support Percentage.” For (a)(1) filers, the form also provides a box for the facts-and-circumstances test.

(b) Donations/Grants Not Counted

Contributions received are counted as public support differently for each category. For planning purposes, these rules are extremely important to consider. Under the (a)(1) category, a particular giver's donations are counted only up to an amount equal to 2 percent of the total “support” for the five-year period.112 Gifts from §170(b)(1)(A)(vi) public charities and governmental entities are not subject to this 2 percent floor; some say grants from those classified as public under §170(b) (1)(A)(i)–(v) are to be counted only up to 2 percent.113

For (a)(2) purposes, all gifts, grants, and contributions are counted as public support, except those received from disqualified persons.114 Such a person may be a substantial contributor or current board member and the close relatives of such persons. A substantial contributor is one who has given more than $5,000, if such amount is more than 2 percent of the aggregate contributions received by the organization throughout its life.115 For (a)(2) purposes, gifts from these insiders are not public support. Subject to the 2 percent ceiling, their gifts are counted for (a)(1) purposes. Grants from other public charities classified under §509(a)(1) are fully counted. Although they are excluded from the definition of substantial contributors under IRC §507, another §509(a)(2), a §509(a)(3), or other category of §501(c) organization is treated as a disqualified person and its grants are subject to limitations on their inclusion in public support for this purpose.116

(c) Types of Support

New accounting standards effective in 2018 may significantly impact the public support test for some nonprofits. Readers should study new subsection (g) for a report on the changes.

Not all revenue is counted as support. The basic definition of support for both categories excludes capital gains from the sale or exchange of capital assets, but other types of gross revenue are counted differently under the two categories.

- Individual contributions Volunteer payments motivated by the desire to help finance the exempt activities of both types of public charities are treated as contributions.117 Such payments are made with the intention of making a gift with no expectation of return or consideration other than intangible recognition, such as inclusion of a name on a sponsor list or on a church pew.

- Business donation Grants from corporations or other businesses are similarly reported as direct public support by both types. Proceeds of a cause-related marketing campaign, also referred to by the IRS as commercial co-ventures, are treated as contributions.118 No value is assigned to the fact that purchase of business products is encouraged by use of the charity's name in such a sales promotion. Sponsorship payments that are acknowledged by the tax-exempt organization without quantitative and qualitative information and are not classified as advertising revenue can be treated as contributions for public support purposes by both categories.119

Membership fees for both categories may represent a charitable donation or fee for services depending on “commensurate rights and privileges” provided to members. A pure donation exists when the benefit is merely the personal satisfaction of being of service to others and furthering the charitable cause in which the members have a common interest.120 When the payment purchases admission, merchandise, services, or the use of facilities, an exchange transaction occurs and service revenue is realized. In some cases, a combined gift and payment for services may be present. The facts in each circumstance must be examined to properly classify the revenue. Under the enhanced scrutiny of the IRS's Special Emphasis Program on deductibility of charitable gifts, some organizations realized that their members are not necessarily making contributions.121 In such cases, the donor disclosure rules must be studied.122 Particularly for (a)(1) purposes, this distinction is very important, because exempt function fees are not included in the public-support calculations.

Government grant awards that represent support for the recipient organization to carry on programs or activities that further its exempt purposes are treated as contributions.123 Such grants are said to give a direct benefit primarily to the general public rather than an economic or physical benefit to the payor of the grant. Instead, some grants are payments in exchange for services to serve the needs of the government agency.124 Government support for an organization that produces a television program aired on government and local access channels; that conducts forums for educating citizens and communities on issues of local interest; that produces and coordinates training programs for city officials and local government employees, businesspeople, and interested citizens; that promotes city government month; and that encourages local governments to develop new ways to improve services and operations was found to be a contribution.125 The language used in the ruling expands the regulation description of the condition under which a government grant is treated as a donation as follows:

A grant is normally made to encourage the grantee organization to carry on certain programs or activities in furtherance of its exempt purposes. It may contain certain terms and conditions imposed by the grantor to insure the grantee's programs or activities are conducted in a manner compatible with the grantor's own programs and policies and beneficial to the public. The grantee may also perform a service or produce a work product which incidentally benefits the grantor. Because of the imposition of terms and conditions, the frequent similarities of public purposes of grantor and grantee, and the possibility of benefit resulting to the grantor, amounts received as grants for the carrying on of exempt activities are sometimes difficult to distinguish from amounts received as gross receipts from the carrying on of exempt activities. The fact that the agreement, pursuant to which payment is made, is designated a contract or a grant is not controlling for the purposes of classifying the payment under §509(a)(2).

When a sale of goods, performance of a service, or admission to or use of a facility must be delivered or provided specifically to the grantor, exempt function revenue is received. Money a health-care provider collects from the state for treatment of indigent patients is referred to under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) as exchange transactions. The terms of the grant agreement indicating gross receipts from a service contract, as contrasted to those terms identifying a contribution, might include the following:

- Specific delivery of services is required within a specific timeframe (time for performance at discretion of grantee).

- Penalties beyond the amount of the grant can be imposed for failure to perform (the only penalty is return of the grant for not conducting a specific program or some other restriction).

- Goods or services are furnished or delivered only to the grantor (program recipients are other than the grantor).

Under both categories, this distinction is important to determine amounts qualifying as contributions. For (a)(2) status, the distinction has yet another dimension. The amount of service fees included as public support from a particular person or organization is limited to 1 percent of gross revenue or $5,000, whichever is higher.126 This limitation on inclusion of service fees means that an organization performing services for a small number of contractors cannot reach the required 33⅓ percent support level under §509(a)(2). Say, for example, that an organization that studies child abuse cases receives most of its revenue from two state agencies. Because only 1 percent of each agency's support can be counted, the organization may have as little as 2 percent qualifying support. Such an organization, dependent primarily on gross receipts from related activities, is precluded from qualifying instead as a §509(a)(1) organization if “it receives an insignificant amount of its support from governmental units and contributions made directly or indirectly by the general public.”127 Moneys received from a third-party payor, such as Medicare or Medicaid patient receipts128 or charges collected by a hospital as agent for a blood bank,129 are considered as gross receipts from the individual patients for services rendered.

In-kind gifts are counted differently for each category. For (a)(1) purposes, the regulation specifically says that support does not include “contributions of services for which a deduction is not allowable.”130 For (a)(2) purposes, the regulation says that support includes the fair market or rental value of gifts, grants, or contributions of property or use of such property on the date of the gift.131 Under (a)(1), the regulations and the IRS instructions to Form 990 are silent about gifts of property that are deductible. It is not stated whether the full fair market value of property whose deductibility is limited to the donor's tax basis,132 such as a gift of clothing to a charity resale shop, is counted at full value or at basis. For accounting purposes, the organization would count such gifts at their full value.

Supporting organization grants and split-interest trust gifts to an (a)(1) public charity are subject to the 2 percent limit. Importantly for (a)(2) entities, such gifts also retain their character as investment income for purposes of limiting the amount of investment income it is allowed to receive.133

(d) Funds Received as Agent

Grants received from another public charity are counted totally toward public support unless the gift represents an indirect grant expressly or implicitly earmarked by a donor to be paid to a subgrantee organization. In that case, the donor for public support purposes is the individual.134 Donor-designated grants therefore require careful scrutiny. The basic question is whether the intermediary organization received the gift as an agent or whether it can freely choose to re-grant the funds. Donations received by donor-advised funds and community foundations qualify as public support to the initial recipient organization (and again to the ultimate recipient) if the fund retains ultimate authority to approve the re-grants.135