CHAPTER 12

Private Foundations—General Concepts

- 12.1 Why Private Foundations Are Special

- 12.2 Special Rules Pertaining to Private Foundations

- 12.3 Application of Taxes to Certain Nonexempt Trusts

- 12.4 Termination of Private Foundation Status

- (a) Involuntary Termination

- (b) Voluntary Terminations

- (c) Transfer of Assets to a Public Charity

- (d) Conversion of Private Foundation into a Public Charity

- (e) Mergers, Split-Ups, and Transfers Between Foundations

- (f) Conversion to a Taxable Entity

- (g) Conversion of Public Charity to Private Foundation

- (h) Notifying the IRS

- APPENDIX 12-1: Brief Description of Tax Sanctions Applicable to Private Foundations

12.1 Why Private Foundations Are Special

Private foundations were segregated by Congress in 1969 from public charities—the latter being those organizations that traditionally receive their contributions from a wide range of supporters, rather than from a limited set of individuals. In the exempt organization community and throughout this book, private foundations are sometimes referred to as PFs. The persons who create, contribute to, and manage PFs are “disqualified persons” sometimes referred to as DPs.

Private foundations are viable and valuable types of nonprofit organizations, and the rules applicable to them warrant the six chapters.1 A PF is often the best tool to accomplish an individual's philanthropic goals. Unfortunately, some professional advisors discourage the formation of PFs because of the sanctions outlined in Exhibit 12.1.

EXHIBIT 12.1 Private Foundation Excise Taxes

| Tax Imposed On | Initial Tax | Additional Tax | ||||

| Sanction | Private Foundation | Managers | 1st Tier Rate | Amount Imposed | 2nd Tier Rate | Assessed |

| Section 4940 | X | 1.39 | of investment income annually on Form 990-PF | N/A | not applicable | |

| Investment Income Tax | X | 1% | tax reduced to 1 percent for PFs increasing grants annually | N/A | not applicable | |

| Section 4941 Self-Dealing | on self-dealer X | 10% | of “amount involved” for each year transaction outstanding | 200% | if self-dealing not “corrected” | |

| on PF manager X | 5% | of “amount involved” for each year transaction outstanding; participating managers jointly and severally liable; can agree to allocate among themselves; maximum for managers $20,000 | 50% | if manager refuses to agree to part or all of correction. Maximum tax = $20,000 | ||

| Section 4942 Underdistribution | X | 30% | of “undistributed income” for each year undistributed | 100% | for each year income remains undistributed | |

| Section 4943 Excess Business Holdings | X | 10% | on fair market value of excess holdings each year | 200% | of excess holdings at end of “taxable period” | |

| Section 4944 | X | 10% | on amount so invested for each year of “taxable period” | 25% | of amount not removed from jeopardy | |

| Jeopardizing Investments | X | 10% | on amount so invested for each year of investment; participating managers jointly and severally liable for maximum tax of $10,000 per investment | 5% | of amount on managers who refused to agree to part or all of removal from jeopardy; maximum for management $20,000 | |

| Section 4945 Taxable Expenditures | X | 20% | of each taxable expenditure | 100% | of uncorrected expenditure at end of “taxable period” | |

| X | 5% | of each taxable expenditure for any manager who knew of and agreed to the expenditure; maximum for all managers $10,000 | 50% | on expenditure manager who refuses to correct all or part of taxable amount; maximum amount $20,000 | ||

Rate reduced from 1 or 2% effective for tax years beginning after December 20, 2019 by Taxpayer Certainty and Disaster Tax Relief Act of 2019.

Granted, the rules are a bit more complicated than those for publicly supported charities, but they can be mastered and become easier once their logic is understood. All organizations qualifying for exemption under §501(c)(3)—private and public—are technically subject to a requirement that they not provide private benefits to those who create and manage them.2 For years, some suggested that all charities should be subject to rules similar to the self-dealing prohibitions applicable to private charities. For reasons more thoroughly described in Chapter 20, in 1996, Congress added penalties, called intermediate sanctions, for public charities that pay excess benefits to certain individuals.

The penalties imposed on violations of the PF sanctions were doubled by the Pension Protection Act of 2006; the initial rates are:3

- IRC §4941 (self-dealing): 10 percent

- IRC §4942 (mandatory payout): 30 percent

- IRC §4943 (excess business holdings): 10 percent

- IRC §4944 (jeopardizing investments): 10 percent

- IRC §4941 (taxable expenditures): 20 percent

A private foundation is a perfect vehicle for philanthropists who want total control over their charitable funds. A charitable trust or corporation whose sole trustee/director/member is also the creator can qualify for exemption. Commonly, the donor and his or her children constitute the board members of a private foundation. Although financial transactions with the creators, and certain other activities, are strictly constrained by the PF rules, nothing prevents absolute control of the organization by founders and their families.

Funders who wish to be flexible in their grant-making programs may prefer a privately controlled foundation for a similar reason. A modest (compared to that spent by most public charities) grant payout requirement, annually equal to approximately 5 percent of the value of the PF's investment assets,4 must be maintained. The private operating foundation5 is a perfect example of this latitude. The funder can establish a PF to further his or her own charitable purposes and hire a staff to manage genuine public interest programs studying the somewhat simple rules in this IRC chapter that must be followed.

Another positive attribute is the fact that family members or other disqualified persons6 can be paid reasonable compensation for work they genuinely perform in serving on the organization's board. Disqualified persons can also be paid salaries for services rendered in a staff capacity. Those who learn the rules and plan well to adhere to them need not allow sanctions to discourage creation of a private foundation.

Finally, a private foundation can serve as a perfect income and estate tax-planning tool for taxpayers with charitable interests. The classic example is a philanthropist who is ready to realize a large capital gain on the sale of readily marketable stock. A PF can be created in the year of sale, gifting the shares to the foundation before the sale is finalized, thereby avoiding tax on the gain. As much as 30 percent of the philanthropist's income can be given to an operating foundation (up to 20 percent to a normal PF) to substantially reduce his or her income tax burden.7 The best part is that the proceeds from selling the shares8 given to create the foundation need not be given away immediately. The foundation must essentially spend only a minimum of 5 percent of the value of the capital gift for its charitable purposes.

Philanthropists who make charitable bequests under their wills can create private foundations to begin to receive a portion of the bequests as donations while they are still living, and thereby obtain a double deduction. Current gifts to the PF are deductible and increase the estate by reducing income tax. The property gifted to the PF and the undistributed income accumulating in the PF are not subject to estate tax. The foundation can also serve as the beneficiary of a charitable remainder trust created during one's lifetime. Such plans usually result in more after-tax money for the charity and for other beneficiaries. There are many possibilities for the charitably minded taxpayer, though a detailed discussion of the giving rules is beyond the scope of this book.

12.2 Special Rules Pertaining to Private Foundations

Private foundations are defined negatively, by what they are not. Any domestic or foreign charity qualifying for exemption under IRC §501(c)(3) is presumed to be a private foundation unless it is a church, school, hospital or affiliated medical research organization, donative or service-providing charity, supporting organization, or an entity that tests for public safety.9

Those charities not able to qualify as public are those most often supported by a individual, family group, corporation, or endowment. They accomplish their charitable purposes by making grants to public organizations of the types listed in the previous paragraph and, less frequently, by spending money directly for charitable projects. It is interesting to note, however, that the first four categories of public organizations listed are public, even if they are privately supported, because of the nature of their activities.

Throughout this part of the book, note the importance of public charities to PFs, both as the usual recipients of their annual gift-giving bounty and as potential recipients of “terminating distributions.” Exhibit 12.1 charts some of the distinctions between public and private charitable organizations, and may make it easier to recall the differences. Publication 4221-PF, Compliance Guide for 501(c)(3) Private Foundations,10 is also a useful source of information. The burden of proving non-PF status rests with each exempt organization. A charitable exempt organization cannot qualify as a §501(c)(3) entity and is presumed to be a private foundation until proper notice is filed with the IRS on Form 1023.11 If the exempt organization fails to file its notice for determination on time, it is treated as a taxable entity until the date of filing. The IRS does not count support received during the delinquency period in determining qualification as a public charity, and only an advance ruling can be obtained.

Unless state law effectively does so automatically, the charter or instrument creating a PF must contain language that prohibits violation of the private foundation sanctions. Every state except Arizona and New Mexico has passed such a statute.12 Without proper organizational restraints, the PF cannot be exempt, nor is it eligible to receive charitable contributions.

If circumstances change or if its creators, for whatever reason, wish it, a PF can terminate its status. For example, its public support might have increased to the point that it can qualify as a public charity. It can also distribute all of its assets to a public charity, or to another private foundation, and go out of business. It can split itself into two or more parts. Voluntary and involuntary termination of PF status are discussed in §12.4.

(a) Types of Private Foundations

Most private foundations are grant-making organizations that devote their assets to supporting public charities and can be thought of as standard, or normal, private foundations. They meet a minimum distribution requirement essentially equal to 5 percent of the value of their assets13 and must adhere to all of the special sanctions listed in the next subsection. Some different rules and privileges are afforded to the following special types of private foundations:

- Private Operating Foundations. A private foundation that actively conducts its own charitable programs has somewhat lower distribution requirements. Though it may make grants to public charities, it must devote its income to its own programs. The allowable income tax deduction for gifts to a private operating foundation is more favorable than that for a normal private foundation.14

- Exempt Operating Foundation. This category of foundation customarily applies to museums, libraries, and other quasi-public charities that meet very specific requirements.15 They are not required to pay the excise tax on investment income.

- Foreign Foundations. These may be subject to tax on their U.S.-based income. A foreign organization is treated as a private charity unless it seeks recognition of its public charity status from the IRS.16 A foreign charity would also seek classification as a public charity to be eligible to receive grants from a domestic private charity.17

- Conduit Foundation. A private foundation becomes a conduit foundation during a year in which it makes qualifying distributions that are treated as distributions out of corpus in an amount equal to 100 percent of the contributions it receives during the year.18 A conduit foundation is sometimes referred to as a “pass-through” foundation because it receives, but does not keep, and instead redistributes donations to allow its donor(s) to receive a higher deduction limitation for contributions to the foundation.19 The status as a conduit foundation applies on a year-by-year basis. The election to treat the gifts as being made out of corpus does not affect the succeeding or-prior-year distributions.

(b) Special Sanctions

When Congress segregated privately funded charities and gave them special status, it was in an anti-foundation mood, resulting in the following sections being added to the Internal Revenue Code. These sections have operational constraints to govern the conduct of private foundations and impose excise taxes for failures to adhere to the rules. Private foundations were scrutinized again by Congress during 2003 in view of complaints that some foundations paid excessive compensation to their disqualified persons. Among the issues of discussion was the fact that the IRS, in view of its very limited resources, seldom examines private foundations. A proposal to eliminate administrative expenses as qualifying distributions, essentially treating them as noncharitable expenditures, would have correspondingly increased the required annual charitable disbursements. A long-suggested reduction of the excise tax rate to 1 percent was also considered. The first section is imposed on all private foundations—an annual tax of 2 percent of the foundation's investment income.20

This tax is calculated annually on the foundation's Form 990-PF.21

- IRC §4940 Excise Tax Based on Investment Income (Chapter 13)

- IRC §4941 Taxes on Self-Dealing (Chapter 14)

- IRC §4942 Taxes on Failure to Distribute Income (Chapter 15)

- IRC §4943 Taxes on Excess Business Holdings (Chapter 16)

- IRC §4944 Taxes on Investments Which Jeopardize Charitable Purpose (Chapter 16)

- IRC §4945 Taxes on Taxable Expenditures (Chapter 17)

- IRC §4946 Definitions and Special Rules (§12.2)

- IRC §4947 Application of Taxes to Certain Nonexempt Trusts (§12.3)

- IRC §4948 Foreign Private Foundations

Appendix 12-1 contains capsule definitions of these provisions to use as a reference guide. Sanctions for failure to comply with the PF rules of IRC §§4941 through 4945 potentially include a tax (called the “Chapter 42 tax”) on both the PF and its disqualified persons, loss of exemption, and repayment of all tax benefits accrued during the life of the PF. Exhibit 12.1 tabulates the excise tax rates and the entity(ies)—sometimes several—subject to the tax. The standards for imposing the penalties on taxable events are somewhat different for each section, as described in Chapters 14 through 17. Form 4720, Return of Certain Excise Taxes on Charities and Other Persons Under Chapters 41 and 42 of the IRC, is filed to report the incidents and calculate any taxes due.

The penalty provisions of IRC §§4942, 4943, 4944, and 4945 originally contained no exception, or excuse, for imposition of the penalty on the private foundation itself for failure to comply with the specific provisions of these code sections. The regulations under these sections do contain relief for those foundation managers who do not condone, or participate in the decision to conduct, a prohibited action. Until 1984, the penalties were very strictly applied.22 In 1984, Congress added IRC §§4961, 4962, and 4963 to permit abatement of the penalties23 imposed on both the foundation (not including self-dealing) and its managers if it is established to the satisfaction of the secretary (by the IRS under responsibility delegated by the Treasury Department) that:

- The taxable event was due to reasonable cause and not to willful neglect.

- The event was corrected within the correction period for such an event.

To allow abatement, the actions of the responsible foundation officials are considered. Although IRC §4962 is entitled “Definitions,” neither it nor the regulations define the terms reasonable cause or willful neglect. There have been no court decisions concerning abatement of these penalties and only a few private rulings construing their meaning for this purpose. In a ruling concerning a taxable expenditure penalty for failure to seek advance approval of a scholarship plan, there was no mention of abatement.24 The congressional committee report says, “A violation which was due to ignorance of the law is not to qualify for such abatement.”25 The regulations pertaining to the penalties imposed on self-dealers and on managers approving of self-dealing, jeopardizing investments, and taxable expenditures, however, do contain definitions that one hopes can be applied to justify abatement of the penalties. The definitions of reasonable cause and willful neglect are the same as those discussed earlier. The PF officials must show that they used good business judgment exercised with ordinary business care and prudence. They must show that they made a good-faith effort to follow the rules by seeking the advice of qualified professionals. The facts and circumstances of the foundation's activities must be fully disclosed to such advisors.

(c) Definitions of Special Terms

The special sanctions applicable to private foundations contain unique and specific definitions of those persons whose actions are curtailed and of those who will be held responsible when violations of the rules occur.

Disqualified Persons. To determine who is in control of a private foundation and thereby subject to restraints against self-dealing and other sanctions, persons and entities in certain relationships to a foundation are treated as disqualified persons (DPs).26 Individuals, corporations, trusts, partnerships, estates, and other foundations can be DPs. The list of DPs encompasses substantial contributors to the foundation; foundation managers; entities that own more than 20 percent of a “substantially contributing” business; family members; and corporations, trusts, or estates that are more than 35 percent owned by disqualified persons.

Substantial Contributors . Using the cumulative total of all contributions and bequests received during the private foundation's existence, a substantial contributor (SC) is a person who has given more than $5,000 or 2 percent of the total aggregate contributions the organization has ever received, whichever is greater. The term person for this purpose is defined to include individuals, fiduciaries, partnerships, corporations, associations, trusts, and exempt organizations, but not governmental units.27 For self-dealing purposes only, this term does not include any charitable organization including a private foundation.28 The creator of a trust is also a substantial contributor, regardless of support level. However, for purposes of §§170(b)(1)(E)(iii), 507(d), 508(d), 509(a)(1) and (3), and Chapter 42, public charities defined by Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §509(a)(1), (2), and (3) are generally not treated as SCs.29 It is important to notice that there is no provision for exclusion of unusual grants to calculate aggregate contributions for purposes of identifying SCs.30 See Exhibit 12.2.

EXHIBIT 12.2 Cumulative List of Substantial Contributors

| Cumulative Donations | 2% Floor | ||

| All years to date | $12,000,000 | $240,000 | |

| Current year | $1,000,000 | ||

| New cumulative amount | $13,000,000 | $260,000 | |

| Updated | |||

| Cumulative by Donor | Donations This Year | Cumulative Donations | |

| Donor ABC | $5,000,000 | $1,000,000 | $6,000,000 |

| Donor DEF | $100,000 | $200,000 | $300,000* |

| Donor GHI | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | |

| Donor JKL | $50,000 | $50,000 |

* Under IRC §507(d)(2), this donor became a substantial contributor.

Note: This report is updated annually to maintain historic data needed to identify donors who have become substantial contributors.

One becomes a substantial contributor the moment after the transaction in which he or she (or it) makes the substantial gift, as a result of the transaction.31 Thus, self-dealing does not occur with respect to the transaction in which one becomes an SC. Importantly, the cumulative contributions forming the basis of the calculation are tallied at the close of each year. A testamentary bequest causes the testator to become an SC, so her or his children and ancestors become disqualified persons upon the testator's death.

With one exception, once one becomes an SC, one remains an SC, regardless of changing PF support levels or death. The exception is this: If, for 10 years, an SC has made no contribution to the PF, is not himself or herself a manager (or related to one), and his, her, or its aggregate contributions are insignificant, that person ceases to be treated as an SC.32

Foundation Managers. A private foundation's officers, directors, and trustees, and individuals having similar powers or responsibilities are its managers.33 If an employee has actual or effective responsibility or authority for the foundation's action or failure to act, he or she is a manager. A person is considered an officer if he or she is specifically so designated under the certificate of incorporation, bylaws, or other constitutive documents of the PF, or if he or she regularly exercises general authority to make administrative or policy decisions on behalf of the PF. Advisors, engaged as independent contractors with no direct legal authority, are not managers. However, employees of a bank that serves as a PF trust officer—although employees of the bank, not the PF—are treated as PF managers for accounts over which “they are free, on a day-to-day basis, to administer the trust and distribute the funds according to their best judgment.”34

Twenty Percent Owners. An owner of more than 20 percent of a substantially contributing business is a DP. Ownership is measured differently for different businesses.35

- For a corporation, it means ownership of more than 20 percent of the “combined voting power.”

- For a partnership, it means ownership of an interest of 20 percent or more of net profits.

- For an unincorporated business, the distributive share of profits determines ownership. If there is no fixed agreement, the portion of the entity's assets receivable upon dissolution is determinative.

- For a trust, ownership is actuarially calculated.

Voting power is determined by attributing stock owned directly or indirectly by or for a corporation, partnership, or estate or trust, as owned proportionately, to its shareholders, partners, or beneficiaries.36 Shares or other economic ownership held by family members described in the next subsection are also attributed. A right to vote dependent on exercising some option, converting shares, or the occurrence of some event, is not treated as voting power.37

Family Members. A family member of any of the aforementioned persons—a disqualified person, a substantial contributor, a foundation manager, or a 20-percent-plus business owner—is also considered a disqualified person. The term “family member” includes the following:38

- Spouse

- Ancestors

- Children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren

- Spouses of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren

- Legally adopted children39

Not defined as family members for this purpose are siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, and any more-distant relatives. If the family member ceases to be a disqualified person, the relative also loses that status the day after the family member loses the status.40 Conversion of a nongrantor trust to a grantor trust was not considered a transfer of property subject to self-dealing rules.41

Thirty-Five-Percent-Plus Business. A corporation of which more than 35 percent of the total combined voting power is owned by one or more disqualified persons is disqualified itself, as is a partnership of which more than 35 percent of the profit interest is owned by a DP. If a disqualified person owns more than 35 percent of the beneficial interest of a trust or estate, then the trust or estate is also considered a DP.42

Other Disqualified Persons. For two limited purposes, other private foundations and government officials are treated as disqualified persons.

The self-dealing prohibition extends to transactions or other arrangements between a corporate foundation and the for-profit business that is related to it, except that the positive public recognition accorded a for-profit company due to the charitable activities of its corporate foundation is not the type of private benefit that is a transgression of the self-dealing rules.

The directors and officers of a for-profit organization that control a corporate foundation are not, by statute, disqualified persons (for that reason) with respect to the foundation. If, however, employees of the for-profit organization are significantly involved in the management of a related corporate foundation on a day-to-day basis, the IRS might assert that officers and/or employees of the company are foundation managers with respect to the foundation.43

Related Private Foundations. For the sole purpose of calculating excess business holdings,44 another private foundation that is effectively controlled, either directly or indirectly, by the PF in question is treated as a DP. The related PF's stock ownership is therefore attributed to the other PF. A PF that, for its entire existence, has received at least 85 percent of contributions from the same persons contributing to another PF is also related for this purpose.45

Government Officials. For self-dealing purposes only, a government official is a DP with whom financial transactions are generally prohibited. A person who, at the time of the act of self-dealing, holds one of the following offices is a governmental official:46

- An elective public office in the executive or legislative branch of the government of the United States.

- An office in the executive or judicial branch of the United States government that is appointed by the president.

- A position in the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the government of the United States that is listed in schedule C of rule VI of the Civil Service Rules, or the compensation for which is equal to or greater than the lowest rate of compensation prescribed for GS-16 of the General Schedule under IRC §5332 of Title 5 of the United States Code.

- A position under the House of Representatives or the Senate of the United States held by an individual receiving gross compensation at an annual rate of $15,000 or more.

- An elective or appointive public office in the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the government of a state, possession of the United States, or political subdivision or other area of any of the foregoing, or of the District of Columbia, held by an individual receiving gross compensation at an annual rate of $20,000 or more.

- A position as personal or executive assistant or secretary to any of the foregoing.

12.3 Application of Taxes to Certain Nonexempt Trusts

Wholly Charitable Trust. Section 4947(a)(1) provides that a nonexempt charitable trust will be treated as a private foundation unless it is a public charity. A nonexempt charitable trust is a trust whose assets are dedicated wholly to charitable purposes but which has not applied for recognition of exempt status under §501(c)(3). Though a nonexempt trust cannot qualify as recipient of an income-tax-deductible charitable contribution, it can escape income tax itself by paying out all of its income to §501(c)(3) organizations. To prevent the creation of trusts for the purpose of avoiding the PF rules, a wholly charitable trust is treated as a private foundation despite the fact that it does not have formal recognition as an exempt charitable organization.47 To be so classified, “all of the unexpired interests of the trust” must be devoted to charitable purposes48 and income, estate, or gift tax deductions must have been allowed for gifts made to the trust.

The tax on investment income and all the other PF sanctions are imposed on a wholly charitable trust and Form 990-PF is filed annually. If such a trust has taxable income under Subtitle A of the Code, it must also file Form 1041.49 Trusts and estates are permitted an unlimited charitable deduction against their otherwise taxable income for donations made pursuant to their governing instrument.50 There are circumstances in which the unlimited deduction may not apply. IRC §642(c)(6) says: “In the case of a private foundation which is not exempt from taxation under §501(a) for the taxable year, the provisions of this subsection shall not apply and the provisions of §170 shall apply” (the deduction would be limited to 50 percent of trust income).51 The regulations, however, say that “§642(c) and this section do not apply to a trust described in §4947(a)(1) unless such trust fails to meet the requirements of §508(e).”52 IRC §508(e) requires that the governing instrument of the trust contain the same language outlined earlier53 and required for qualification to receive a charitable contribution under IRC §170(c). Therefore, an unlimited charitable deduction should be available to those nonexempt trusts located in states that automatically impose the organizational requirements.

Split-Interest Trusts. Split-interest trusts, or those holding property devoted to both charitable and noncharitable beneficiaries, are subject to some of the PF rules.54 For example, such a trust might have a remainder interest payable to a named charity with the current income payable to the creator's son. Such a trust cannot formally seek tax-exempt status because of its unexpired noncharitable interests, but a deduction is allowable for the value of the charitable interests placed in them. The sanctions against self-dealing (Chapter 14), taxable expenditures (Chapter 17), and excess business holdings and jeopardizing investments (Chapter 16) apply to such trusts as if they were private foundations. Forms 5227 and 1041 (to report any taxable income from an unrelated business activity) are filed for a charitable lead trust. A §664(d) charitable remainder trust should file only Form 5227. It is not permitted to earn unrelated business income. If it has such income, Form 1041 is filed to pay income tax and Form 4720 is due to report the penalty.

12.4 Termination of Private Foundation Status

A private foundation may wish either to terminate its existence or to change its PF classification for many reasons. Some foundations have charter provisions requiring that they terminate after a designated number of years. Second-generation trustees may choose to divide a PF's assets into several foundations so each can manage its own.55 A foundation's mission may be accomplished by spending its assets to buy a historic building and donating the site to a preservation society. An existing private foundation or a public charity reclassified as private because it was unable to sustain the requisite public support levels56 can seek IRS approval for its conversion to a public charity because it plans to seek public support.57 In a rare circumstance, there could be some action58 that would be impermissible if the organization remained a private foundation. Such organizational changes are referred to as voluntary terminations.

The IRS can also cause an involuntary termination of a foundation for reasons of repeated violations of the PF sanctions. For either type, a PF must carefully follow the rules for terminating its existence because missteps can be costly. Unfortunately, the tax code begins with the following draconian language:

Internal Revenue Code §507(a) entitled “Termination of Private Foundation Status,” says as a general rule—except as provided in §507)(b), the status of any organization as a private foundation shall be terminated only if:

- Such organization notifies the Secretary… of its intent59 to accomplish such termination, or

- (A) With respect to such organization, there have been either willful repeated acts (or failures to act), or a willful and flagrant act (or failure to act), giving rise to a liability for tax under chapter 42, and

(B) The Secretary notifies such organization that … it is liable for the tax imposed by §507(c).

The amount of the termination tax is equal to the lower of (1) aggregate tax benefits resulting from the §501(c)(3) status of the foundation, or (2) the value of the net assets of the foundation.60 As quoted here, the statute starts with the pronouncement that a private foundation can terminate—commonly meaning “to cease to exist”—only if it gives advance notice to the IRS of its intention to do so. Additionally, it must either pay back all the tax benefits it and its donors ever received or secure IRS abatement of such tax through a private ruling.

The fact that these steps are not required for most types of PF terminations is buried deep in the long and complicated regulations. It is with good reason, therefore, that during the 30-plus years since PFs were created as a special subset of charitable organizations, professional advisors have recommended that a foundation file a private letter ruling to seek IRS approval for its termination and to determine that the termination tax is not due.

To understand the reason the new guidance was possible, it is useful to focus on the words “except as provided in subsection (b).” The termination tax is imposed by §507(a) in only two situations: (1) The foundation itself voluntarily gives notice of its intention to terminate and seeks abatement of any tax, or (2) what the regulations refer to as an “involuntary” termination61 occurs because the foundation has consciously and intentionally disregarded the special constraints placed on the conduct of PF affairs by §§4941 through 4945.

Happily, intending to discourage unnecessary ruling requests, the IRS allows the following voluntary termination requests:

- Transfer of all assets to a public charity [§507(b)(1)(A)].

- Conversion to a publicly supported charity based on plans to raise revenues sufficient to achieve the 33⅓ percent support level [§507(b)(1)(B)] (which is essentially an advance ruling for conversion due to public support).

- Transfer to or merger with another private foundation(s) [§507(b)(2)].

The requests are filed with the EO Determinations office in Cincinnati, Ohio.62 Very helpful guidance was issued to verify that IRS notice is not required for several types of terminations. Rules applicable to transfers of assets between commonly controlled private foundations were the subject of a 2002 ruling.63 Then, in 2003, the IRS issued guidance for transfers of assets to public charities.64

(a) Involuntary Termination

The ultimate penalty for failure to play by the excise tax rules that Congress designed to curtail PF operations is involuntary termination, also called the third-tier tax. When a PF has willfully repeated flagrant act(s) or failure(s) to act, giving rise to imposition of the sanctions set out in IRC §§4941 through 4945, the IRS will notify the PF that it is liable for a termination tax.65 The termination tax equals the lower of the aggregate tax benefit resulting from §501(c)(3) status or the foundation's net assets.

Aggregate Tax Benefit. The sum of the tax benefits resulting from the PF's exempt charitable status is potentially due to be paid—all of the income, estate, and gift taxes saved by the PF's contributors. The amount equals the total tax that would have been payable if deductions for all contributions made after February 28, 1913, had been disallowed. The aggregate increase in income tax that would have been due in respect of income earned by the foundation during its existence is added. Lastly, interest is due on the increases in tax between the day the taxes would have been due and the date of termination.

Repeated Acts. At least two acts or failures to act, which are voluntary, conscious, and intentional, must be committed.66 The offense must appear to a reasonable person to be a gross violation of the sanctions, and the managers must have “known” that they were violating the rules. The “knowing” rules are discussed in §16.2(c).

Foreign Private Foundations. The termination tax does not apply to termination of a foreign private foundation that has received substantially all of its support, other than gross investment income, from sources outside the United States.67

(b) Voluntary Terminations

When the directors or trustees decide for whatever reason that they cannot continue to operate a private foundation, they can dissolve or terminate the foundation's existence in the following ways:

- All of the foundation's assets can be given away to a public charity (§12.4(c)).

- The foundation can convert itself into a public charity by virtue of the activities it will begin to conduct—operate as a church, school, or hospital—or by seeking public funding that will equal at least one-third of its annual revenues (§12.4(d)).

- A private foundation can merge with, split itself up into, or contribute its assets to one or more other private foundations (§12.4(e)).

(c) Transfer of Assets to a Public Charity

A private foundation that wishes to cease to exist, or terminate, can transfer or donate all of its assets to one or more public charities qualified under IRC §509(a)(1). Such a terminating foundation must not have had any flagrant or willful acts or failure to act giving rise to penalty taxes. A foundation terminating in this fashion is not required to notify the IRS in advance and does not incur a termination tax.

Eligible Public Charity Recipients. The recipient organization must have been in existence for at least 60 continuous months.68 The statute is somewhat confusing because it mentions only “organizations described in §170(b)(1)(A) (other than in clauses (vii) and (viii)).” That would mean only churches, schools, hospitals, and donative public charities would qualify as recipients, to the exclusion of a symphony society, theater, or scientific research organization, for example. Public charities that support one or more other public charities are also not mentioned. The regulations69 and private rulings70 expand qualifying public charity recipients to include service-providing public charities described in §509(a)(2)71 and supporting organizations described in §509(a)(3), as more fully explained later in this section.72 A published ruling clarifies the eligibility of all public charities classified under §§509(a)(1), (2), and (3).73 The ruling takes into account the basic fact that situations involving this type of transfer may occur. The four situations discussed in this ruling are predicated on the following assumptions:

- The private foundation has not committed either willful repeated acts (or failures to act), or a willful and flagrant act (or failure to act), giving rise to tax liability under the private foundation rules.

- The foundation is not a private operating foundation.

- The transferee organization or organizations are not controlled, directly or indirectly, by the foundation or by one or more disqualified persons with respect to it.

- The foundation has not previously terminated its private foundation status (or had it terminated).

- The transferee organization is a public charity (an entity described in IRC §§509(a)(1), (2), or (3)) that retains its public charity classification for at least three years following the date of the distribution.

- The foundation does not impose any material restrictions on the transferred assets.

- The foundation retains sufficient income or assets to pay any private foundation taxes, such as the tax on investment income for the portion of the tax year prior to the distribution, files a final Form 990-PF, and pays these taxes when due.

Situation 1. A private foundation (PF) distributes, pursuant to a plan of dissolution, all of its net assets to a public charity (PC). PC is a public charity by reason of classification pursuant to IRC §509(a)(1), because it is an entity described in IRC §170(b)(1)(A)(i)–(vi).74 PC has been in existence and a public charity for a continuous period of at least 60 calendar months immediately preceding the distribution. After PF completes the transfer, it files articles of dissolution with the appropriate state authority.

Situation 2. The facts are the same as in the first situation, except that PC has been in existence for fewer than 60 calendar months immediately preceding the distribution. Moreover, it was not formed as a result of a consolidation of other public charities of the same classification that would have been in existence for a continuous period of 60 calendar months prior to the distribution had they continued in existence.

Situation 3. The facts are the same as in the first situation, except that PC is a public charity by reason of classification pursuant to IRC §509(a)(2). This type of public charity is usually a service-providing organization.

Situation 4. The facts are the same as in the first situation, except that PC is a public charity by reason of classification pursuant to IRC §509(a)(3). This type of public charity is a supporting organization.

IRS Conclusions. In Situation 1, the distribution was made in accordance with the rules concerning favored terminations. This means that PF's status as a private foundation is terminated at the time of the distribution to PC. PF is not subject to the termination tax. PF is not required to give notice to the IRS to terminate its foundation status.

The distributions in Situations 2, 3, and 4 were not made in accordance with the favored termination rules. Thus, the status of PF as a private foundation is not terminated until it gives notice to the IRS. If PF does provide the notice (and thus terminates), it must ask for abatement of, or become subject to, the termination tax. If, however, PF does not have any net assets on the day it provides the notice (for example, because it gives the notice the day after it distributed all of its net assets), the tax is zero.

In all four situations, the distributions do not constitute an investment by PF for purposes of the investment income tax.75 Therefore, the distributions do not give rise to net investment income. In these four situations, the distributions are to tax-exempt charitable organizations, which are not disqualified persons. Thus, the self-dealing rules are not implicated.76 In these instances, the payments are made in accomplishment of charitable purposes and are not to organizations controlled by PF. Thus, the transfers are qualifying distributions. These distributions do not cause PF to have excess business holdings, nor are they jeopardizing investments. Further, the distributions are to public charities and thus are not taxable expenditures; therefore, expenditure responsibility is not required. Complete details should be included in Form 990-PF for the year of the termination. Proof of public status of the recipient organization(s) should be maintained in the files of the terminating PF.

Restrictions and Conditions. All right, title, and interest in and to all of the net assets must be transferred. No material restrictions or conditions can be imposed preventing free and effective use of the assets by the public charity. The following questions are used to find restrictions:77

- Does the public charity become owner in fee of the transferred assets?

- Are the assets used by the public charity for its exempt purposes?

- Are the assets subject to liabilities, leases, or other obligations limiting their usefulness?

- Does the public charity's governing body have ultimate authority and control over the assets?

- Is the public charity operated separately and independently of the PF?

- Were members of the public charity board chosen by the PF?

As illustrated by the acceptable and unacceptable conditions outlined in the preceding list, the transfer of private foundation assets must be complete. The recipient public charities must have absolute dominion and control over the use of the assets they receive. Similar to terms allowed for donor-designated funds, however, the foundation officials can ask that they be allowed to advise, or make suggestions, about the use of its funds.

Acceptable Terms. It is permissible for the public charity to name a fund to hold the assets after the donor foundation or its founders. The charitable purpose for which the transferred funds are to be used can be designated. Finally, the transferor can require that the property be retained and not sold when it is important to the charitable purpose, such as a nature preserve or historic property. Such a restriction cannot be placed on investment assets that are not part of the charity's exempt function activities.

Unacceptable Terms. The private foundation, its disqualified persons, or others designated by it cannot retain a right, directly or indirectly, to name the persons to which distributions are made by the recipient public charity, nor the timing of the distributions. The transfer agreement cannot require that the recipient public charity perform some action that the private foundation transferee was not permitted to perform. The recipient public charity must not receive the PF's assets subject to some obligation or liability inconsistent with its own purposes or best interests. The transferee must not agree to give a first right of refusal to purchase or sell transferred property to persons connected with the transferor PF. An irrevocable agreement to continue a management and maintenance relationship with a bank, brokerage firm, or other advisor is not permitted. Essentially, the agreement cannot impose any action on the recipient organization that would restrict and limit its ultimate control over the assets for its own tax-exempt purposes. The regulations contain a long list of factors that might suggest that the agreement results in the reservation of impermissible rights.78

(d) Conversion of Private Foundation into a Public Charity

A private foundation (PF) can file Form 8740 to request a reclassification as a public charity when it plans to change its method of operation or sources of support and become a public charity.79 This form is also used by a public charity seeking reclassification to a different category or public charity. The form in Item (g) facilitates a request for “Reclassification of foundation status, including a voluntary request from a public charity to private foundation status.”80

Basically, a PF can adopt plans to qualify under IRC §509(a)(1), (2), or (3) and submit an application for approval to the EO Determinations office.81 Beware, as timing here is very important: the termination notice must be filed in advance of the year in which it is to begin. A foundation anxious to begin the termination period is permitted to change its accounting period in order to have the termination period begin sooner.82 Last, information evidencing its success or failure in achieving attributes to qualify as a public charity must be submitted to the IRS at the end of the 60 months.

Form 8940, Request for Miscellaneous Determination, was issued in July 2012. This form is used to request approval for a 60-month termination of private foundation status (Item (h)). This form is filed again at the end of the 60-month termination period to submit information evidencing the organization's successful receipt of sufficient public support to maintain public charity status or instead its failure to do so.83 As a condition to receiving the advance ruling, the organization must consent to extend the period of limitations to assess §4940 tax, for any tax year within the period. Form 990-PF is filed during this five-year period, except for the final year in the period, for which an organization that successfully achieves public status files a Form 990 instead.

60-Month Termination. A private-foundation-to-public-charity conversion is called a 60-month termination because the requirements are to be met throughout and by the end of the continuous period of 60 months. The foundation does not have to qualify as publicly supported at the beginning of the termination period; it merely presents financial projects and plans to demonstrate the ability to do so cumulatively by the end of the period. Form 990-PF is filed during the 60-month period84 because parts of that form provide information necessary to monitor adherence to the private foundation sanctions. Although the self-dealing, mandatory payout, excess business holdings, jeopardizing investments, and taxable expenditure rules of IRC §§4941–4945 do not apply85 in which the requisite public support level is achieved, they do apply if it is not achieved ultimately. Subject to an extension of time for its assessment for any year during which the support is insufficient, the excise tax assessed under §4940 is not required to be paid during the 60 months, although it can be paid and then a request for refund filed upon a successful termination. Within 90 days after the end of the termination period, information must be filed with the IRS to demonstrate qualification as a public charity.86 If the information submitted evidences public charity qualification, then the organization is treated as a public charity for the entire 60-month period regardless of whether it met the test in any individual year during the period.87

Consequence of Failure. If at the end of the 60-month period, the organization does not meet the criteria to be treated as a public charity, it is treated as a private foundation for any year in the 60-month period in which it did not qualify as a public charity.88 This means that the foundation is responsible for paying the tax under §4940 (if deferred during the 60-month period as permitted) plus interest; if there were any violations under §§4941–4945, those penalties would be due as well. A foundation in this circumstance would tally up the §4940 tax that should have been paid on previously filed returns during the termination period and pay that amount plus interest. The IRS provides no specific instructions; however, the appropriate pages of Form 990-PF on which the tax calculation is made should accompany the payment. Similarly, Form 4720 must be filed to report any violation and pay any related penalty incurred during the termination period. Fortunately, grantors to a foundation that has an advance ruling of public charity status can rely upon that ruling regardless of the ultimate outcome, as long as the grantor was not responsible for or aware of an act or failure to act that resulted in the foundation's failure to qualify.89

Reasons to Convert. A variety of circumstances could arise to make conversion to a public charity desirable. For example, because of a delay in start-up of operations and attendant fund-raising programs, an organization classified as public during its first five years of existence90 might mathematically fail to receive more than one-third of its support from the public. The current-year support levels might qualify it as public, but the cumulative totals for the first five years do not. Thus, it becomes classified as a private foundation during its sixth year. In a timely fashion, this organization could request a continuation of its public status with a new 60-month termination. The possibility of using the facts-and-circumstances test or unusual grant rules to retain public status during the original period should also be explored.91

Another example is a privately endowed operating foundation—say, a museum—that plans to undertake a major public campaign to expand its operations. It is privately funded in the early years but converts as soon as possible to public status. Sometimes a private foundation ceases grant-making and converts its operations to a type that qualifies for public status, such as a hospital or school.

(e) Mergers, Split-Ups, and Transfers Between Foundations

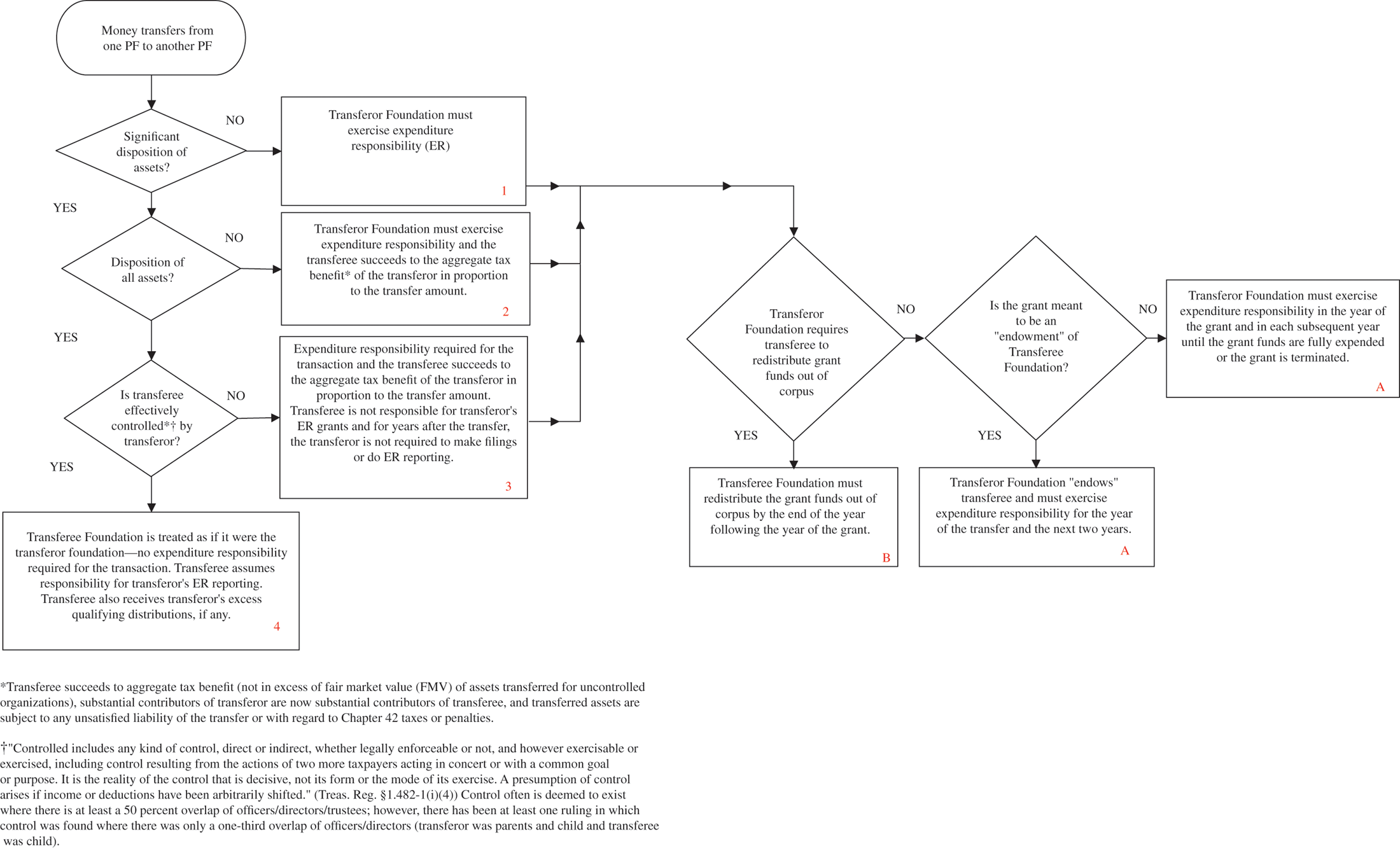

When one private foundation transfers all its assets to another private foundation, pursuant to any liquidation, merger, redemption, recapitalization, or other adjustment, organization, or reorganization, the transferee (recipient) foundation is not treated as a newly created organization.92 Furthermore, the transferor foundation has not terminated its private foundation status under §507(a)(1)93 and need not have notified the IRS in advance of its intentions.

When 25 percent or more of a foundation's assets are transferred (called a “significant disposition of assets”) to one or more other private foundations, the recipient private foundation(s) “shall be treated as possessing those attributes and characteristics of the transferor which are described in [Reg. §§1.507-3(a)(2), (3), and (4)].”94 When assets are distributed to commonly controlled foundations, the transferee foundations succeed to certain other tax attributes of the transferor if they are effectively controlled by the transferor.95

IRS Road Map for Reforming a Foundation. In 2002, the IRS addressed three specific types of private foundation reorganizations involving commonly controlled private foundations.96 The ruling describes the filing obligations and excise tax issues that arise when a private foundation transfers assets to one or more other private foundations. The ruling is based on the following presumptions, the last of which limits the applicability of the ruling to commonly controlled foundations:

- All of the foundations involved are classified as tax-exempt §501(c)(3) organizations, are treated as private foundations under §509, and are not private operating foundations according to §4942(j)(3).

- None of the foundations involved have committed willful and flagrant acts, or failures to act, giving rise to tax under IRC Chapter 42 so as to be subject to the termination tax under §507(a).

- The private foundations have not terminated under §§507(a)(2) or (b)(1).

- The transferor foundation has outstanding expenditure responsibility grants requiring future monitoring and reports.

- All of the foundations, both the transferor(s) and transferee(s), are effectively controlled, either directly or indirectly, by the same persons. Effective control of the transferee foundation is determined within the meaning of §482, which essentially refers to all forms of control, direct or indirect, whether legally enforceable and however exercisable or exercised.97

The ruling considers the reporting requirements and factors that carry over to the successor foundations in the following three situations:

- Situation 1: PF P splits into PFs X, Y, and Z.

- Situation 2: PF T (a trust) transfers assets to PF W (a nonprofit corporation).

- Situation 3: PF J and PF K merge to create PF V.

Situation 1. A private foundation, due to the divergent interests of its current directors, distributes all of its remaining assets in equal shares to three other private foundations. Pursuant to the plan of dissolution, the foundation satisfies all of its outstanding liabilities; causes the recipient foundations to satisfy its expenditure responsibility reporting requirements; and, after all of its assets are transferred, files articles of dissolution with the appropriate state authority.

Situation 2. The trustees of a private foundation trust create a not-for-profit corporation to carry on the trust's charitable activities, which the trustees have determined can be more effectively accomplished by operating in corporate form. All of the trust's assets and liabilities are transferred to the new not-for-profit corporation.

Situation 3. Two private foundations that confine their grant-making activities to programs in the particular city in which they are located transfer all their assets and liabilities to a newly formed private foundation.

Questions Answered in Ruling. The IRS poses and answers the following four questions. Quotation marks indicate where the exact words of the ruling are reprinted.

Question 1. If a private foundation transfers all of its assets to one or more private foundations, is the transferor foundation required to notify the IRS of its plans to terminate its private foundation status and pay the termination tax?

Answer. The IRS answer is no to both parts of the question. Advance IRS notification is not required when a private foundation voluntarily disposes of a significant portion of its assets to one or more private foundations.98 A transfer of all of a private foundation's assets to one or more private foundations constitutes a significant disposition.99 In Situations 1, 2, and 3 (described earlier), no termination has occurred.100

This conclusion is simple, making one glad the IRS has provided this guidance: Finally there is clarity that the §507(a) language that prompted so many unnecessary private letter ruling requests in the past 30 years does not always apply. Plain and simple, the transfer of assets from one private foundation to another does not constitute a termination unless the private foundation voluntarily provides notice of its intent to terminate. According to the ruling, the fact that the foundation dissolves under state law has “no effect on whether it terminated its private foundation status for federal tax purposes.” If the foundation chooses to provide notice, and thereafter voluntarily terminates, it is potentially subject to the §507(c) tax, unless it requests and achieves abatement of the tax. If the foundation has no assets on the day it provides notice (e.g., it provides notice at least one day after it transfers all of its assets), the §507(c) tax will be zero. The answer is true even if the ruling does not apply because the foundations involved are not commonly controlled.

Question 2. What are a private foundation's tax return filing obligations after it transfers all of its assets to one or more transferee private foundations and (a) its legal existence is dissolved, or (b) it continues to exist in a dormant condition?

Answer. A private foundation that has disposed of all its assets must file a Form 990-PF for the tax year of the disposition and comply with any expenditure responsibility reporting obligations on the return. These filing requirements apply both for a private foundation that terminates by giving §507(a) notice and for one that does not terminate its private foundation status pursuant to the conclusion to question 1. The due date of the return is the fifteenth day of the fifth month following complete liquidation, dissolution, or termination.

The transferor foundation attaches a statement to its Form 990-PF for the year in which it has a “liquidation, dissolution, termination, or substantial contraction.”101 A certified copy of the liquidation plan or resolutions (if any), schedule of the names and addresses of all recipients of assets, and an explanation of the nature and fair market value of the assets to each recipient are requested.102 If the foundation has ceased to exist, the “Final” box on page 1 of the form is checked.

If the entity remains in existence as a dormant shell without equitable title to any assets and without activity, it does not need to file returns in the following tax years.103 If, in later years, it receives new assets or resumes activities, it must resume filing Form 990-PF. The ruling also says that such a shell foundation should remain qualified as a §501(c)(3) organization eligible to receive charitable contributions.

Any unfinished steps in the expenditure responsibility process, such as securing and reporting follow-up grantee reports, become the obligation of the transferee foundation(s) that are commonly controlled by the transferor foundation. As mentioned in the ruling, when multiple transferee foundations exist, a single transferee can assume this obligation. In the absence of a single transferee foundation accepting the obligation for expenditure responsibility reporting of the transferor foundation, all transferee foundations are obligated.

Question 3. If a private foundation transfers all of its assets to one or more private foundations that are effectively controlled,104 directly or indirectly, by the same person or persons who effectively control the transferor foundation, what are the implications under §§4940, 4941, 4942, 4943, 4944, and 4945?105

Answer. The IRS's answer to this question focuses on the fact that the successor foundation(s) inherit virtually all of the tax attributes of the transferor foundation. The recipient private foundation is not considered a newly created organization,106 whether it is commonly controlled or not. All tax obligations and attributes stemming from the code sections listed earlier—with one important exception noted in the answer to question 4—carry over to the successor foundations.

If a private foundation incurs liability for one or more of the taxes imposed under Chapter 42 (or any penalty resulting therefrom) prior to, or as a result of, making the asset transfer(s), in any case where transferee liability applies, each transferee foundation is treated as receiving the transferred assets subject to such liability to the extent that the transferor foundation does not satisfy such liability.107 Further, a substantial contributor with respect to the transferor foundation is treated as a substantial contributor with respect to each recipient foundation receiving its assets, whether or not such person meets the $5,000/2 percent test with respect to the transferee(s) at any time.108 The consequences of the transfers and resulting carryovers are described in Exhibit 12.4, Transfers between PFs.

EXHIBIT 12.3 Tax Attributes Transferred to Successor Private Foundation

The Trustees of the _______________________________________________ (Old Foundation) have determined that it is in the best interest of the Foundation for it to dissolve, and to distribute two-thirds (2/3) of its assets remaining after the payment of any liabilities to __________________________, a charitable trust (EIN: ______________________________) and one-third (1/3) of the assets remaining after the payment of any liabilities to _______________________, a Texas nonprofit corporation (EIN: ________________) effective as of the close of business on June 30, 2018. As explained below, the Old Foundation's transfer of all of its net assets to the two successor foundations will be governed by §507(b)(2) and the Treasury Regulations promulgated thereunder.

Such a transfer is described in Treasury Regulation §1.507-3(a)(9), which states: “If a private foundation transfers all of its net assets to one or more private foundations which are effectively controlled (within the meaning of §1.482-1(a)(3)), directly or indirectly, by the same person or persons which effectively controlled the transferor private foundation, for purposes of Chapter 42 (§4940 et seq.) and Part II of subchapter F of Chapter 1 of the Code (§§507 through 509) such transferee private foundations shall be treated as if they were the transferor.” Additionally, IRC §507(b)(2) provides that “in the case of a transfer of assets of any private foundation to another private foundation pursuant to any liquidation, merger, redemption, recapitalization, or other adjustment, organization, or reorganization, the transferee foundation shall not be treated as a newly created organization.”

In accordance with this Regulation and Code section, the Old Foundation has completed its 2018 Form 990-PF for the short year January 1, 2018, to June 30, 2018. The activity for the short period will be allocated two-thirds (2/3) to and one-third (1/3) to as if they were the Old Foundation for purposes of Chapter 42. The successor foundations will complete 12-month 2018 Form 990-PFs to report the six months of activity allocated to them by the Old Foundation in addition to the six months of activity each conducted directly. See the following summary by return part:

| Part I: | The successor foundations have picked up the Old Foundation's income and expenses for purposes of §4940. |

| Part V: | The successor foundations have reported the Old Foundation's historical distributions and asset averages for computation of the 1 percent rate calculation. |

| Part VI: | The successor foundations have applied the overpayment of excise tax of $115,964 from the Old Foundation's 2017 Form 990-PF as if it were their own. |

| For estimated tax purposes, 2220: | The successor foundations have reported the annualized amounts and tax payments attributable to the Old Foundation in addition to their own amounts. |

| Part X: | The successor foundations have calculated the average value of assets as if they held all of the Old Foundation's assets the entire year. |

| Part XII: | The successor foundations have included the qualifying distributions of the Old Foundation as if they were made by the New Foundation. |

| Part XIII: | The successor foundations have picked up the Old Foundation's undistributed income for 2017 of $6,428,340 as if the income were its own. |

| Part XV: | The successor foundations have picked up the Old Foundation's grants of $1,810,000 as if they were made by the successor foundations. |

Short Taxable Year Ending 6/30/202X

| Old Foundation | Successor Foundations | ||||

| IRC § 507(b)(2) Transfer | 100% | 66.67% | 33.33% | ||

| Part I, Line 11 | $9,741,747 | $6,494,498 | $3,247,249 | ||

| Part I, Line 23 | $815,320 | $543,547 | $271,773 | ||

| Part III, Line 5 | $134,807,678 | $89,871,785 | $44,935,893 | ||

| Part VI, Line 6a | $115,964 | $77,309 | $38,655 | ||

| Part XIII, Line 2a | $6,428,340 | $4,285,560 | $2,142,780 | ||

| Part XV, Line 3 | $1,810,000 | $1,206,667 | $603,333 | ||

| Form 990-T, Line 29 | $2,287 | $1,525 | $762 | ||

| Form 990-T—NOL | ($481,216) | ($320,811) | ($160,405) | ||

Section 4940. The transfers do not give rise to net investment income and are not subject to tax under §4940(a). The basis for this answer is the fact that the transferred assets do not represent taxable income.109 From an accounting standpoint, the value of the net assets received by the transferee(s) would be reported as a donation if the recipient foundation were not commonly controlled. When the recipient foundation is controlled by one or more of the same persons who controlled the transferor, the value of the assets transferred is not reported as revenue, but instead would be reflected as an extraordinary increase in net assets.110

The recipient foundations may use their proportionate share of any excess §4940 tax paid by the transferor to offset their own §4940 tax liability. This transfer could occur on the transferor's final return in the form of a special request that its tax credit be applied to its transferee(s). Since the IRS has acknowledged that the transferee is entitled to the funds, it might be preferable to simply request a refund. In the author's experience, a transfer of tax deposits from one entity to another is sometimes a flawed process. When underpayment penalties will not result, it would be preferable to avoid this issue by causing the final return to reflect a tax liability rather than an overpayment of tax.

Because an overpayment of tax is an asset, a foundation with such a receivable should specify in the transfer documents that it is donating the overpayment to the transferee. This step may protect it from an assertion that it has not transferred all of its assets. An unanswered question is the impact of the transfer on the estimated tax requirements for the transferee foundation(s). When the tax attributes carry over, theoretically it would be reasonable to allow the successor to base its safe estimate amount on the transferor's tax liability for the prior year. Absent guidance, the successor should follow the normal rules for newly created private foundations that require tax deposits based on its actual income received throughout the year using the annualization method provided in the instructions for Form 2220.

Another investment income issue not mentioned in the ruling or the regulations is the calculation of depreciation or depletion on investment properties, such as rental buildings, mineral interests, and assets utilized to manage such properties. Again due to the carryover of tax attributes, the foundation receiving such assets would continue to follow the tax methodology and basis used by the transferor for those assets. Similarly, the basis of transferred assets for purposes of calculating taxable gain or loss for an investment property subject to the excise tax on investment income would be the same as the tax basis for the transferor.

Before 2020 when the dual tax rate system applied, due to the statutory provision that a new foundation receiving 25 percent or more of a successor foundation's assets111 inherits all of the predecessor foundation's tax attributes, the new foundation had an opportunity to reduce its excise tax on investment income in its first year. Contrary to the general rule,112 the 1 percent tax was achieved by carrying over the percentages resulting from the predecessor's payout history in its first year. Exhibit 12.3 is an example of an attachment to Form 990-PF for the successor foundations. The Form 990-PF, on the front page, contains a box entitled “first year.” The author suggest consideration of not checking that box for the first return filed by the successor(s) because doing so implies that the Part IV tax reduction calculation does not apply.

Section 4941. The transfers do not constitute self-dealing.113 The reason for this conclusion is the fact that the foundations involved in such transfers are charitable organizations pursuant to §501(c)(3). Self-dealing occurs only in transactions between a foundation and its disqualified persons.

In planning for a transfer to another foundation, the possibility that relatives not currently treated as disqualified persons might become disqualified should be anticipated. Certain relatives—particularly aunts, uncles, nieces, and nephews—who are not treated as disqualified persons in respect to the transferor could have some connection to relatives of board members or businesses owned by the transferee foundation. This caution is indicated when the transfers involve excess business holdings or partial interests in property that might have to be disposed of as a result of the transfers.114

Section 4942. The transfers do not constitute qualifying distributions for the transferor foundation because the recipient foundations are not required to redistribute the full amount of the transfers and treat it as a distribution out of corpus. The transferee foundation assumes its proportionate share of the transferor foundation's undistributed income and reduces its distributable amount by its proportionate share of the transferor's excess qualifying distributions.115

To understand this conclusion, one must start with the fact that the transferor foundation is required to meet its own distribution requirements for the year in which the transfer occurs.116 Generally, this payout amount is equal to 5 percent of the average value of the transferor's investment (referred to as “nonexempt function”) assets for the year preceding the transfer, called its “minimum investment return.” Assume that a foundation has $10 million of investment assets; the distributable amount equals $500,000 less its excise tax on investment income for the year, plus returned grants previously claimed as distributions. This “undistributed income,” adjusted for over- or underdistributions from prior years, must be paid out before the end of the foundation's next succeeding year. The payout requirement is satisfied by payments of qualifying distributions: charitable grants, expenditures for the foundation's own charitable programs, and administrative expenses.

Final-Year Issues. The final year for the transferor foundation ends on the day it is dissolved. In many circumstances, the year will, therefore, be less than a full 12 months. A distributable amount is calculated for the transferor foundation as if it had continued in existence. If the recipient foundation(s) is commonly controlled, the distributable amount must be paid out by the transferee(s). That amount equals 5 percent of the average value of its assets for the months of the year it was in existence. For a tax year of less than 12 months, the payout percentage is apportioned for the number of days it was in existence. Assume that it is a calendar year in which a foundation distributes all of its assets to a successor foundation and dissolves its charter as a nonprofit corporation on June 30. The required payout percentage equals the number of days it was in existence (182 days) over 365 days times 5 percent, or 2.5 percent. If, for example, the average value of investment assets equals $10 million, a payout amount of $250,000, adjusted for over- or underdistributions, must be spent for charitable purposes by the transferee foundation because it inherits all of the tax attributes of the transferor foundation.

Multiple successor transferees, such as those in Situation 1, become proportionately responsible to distribute or succeed to any excess distributions. In Situation 2, the newly created nonprofit corporation would be solely responsible for, or accede to, any under- or overdistributions from the charitable trust. Lastly, in Situation 3, the new private foundation would inherit the remaining distribution requirement or excess distribution carryover of both of its transferors.

It is important to note that the ruling stipulating the results in the preceding paragraph applies to foundations that are effectively controlled. The definition of qualifying distributions includes any amount paid to accomplish a charitable purpose, other than a contribution to a private foundation that does not redistribute the amount within a timely manner and make a distribution out of corpus for such amount.117 The requirement that the transferee foundation(s) make qualifying distributions on behalf of the transferor necessitates good planning and attention to this detail and to timing details. Normally, newly created private foundations, such as the successors in Situations 2 and 3, have no distribution requirements in the first year. However, the next succeeding year of the transferor is the year the transferee receives its assets. Thus, the remaining distributable amount must be paid out in that year.

Consider Situation 2 and assume that charitable trust T transfers assets on June 30 and closes its six-month tax year with a remaining distributable amount to recipient nonprofit corporation W, as a calendar-year filer. Corporation W would be required, before December 31 of the transfer year, to complete the required distributions for Trust T. Similarly, the newly created foundation V in Situation 3 would be required to satisfy the remaining payout requirements for foundations J and K before the end of their first tax year.118 When the transferee foundation has already been in existence (as may be the case in Situation 1), the transferor's remaining distributable amount would be payable in addition to any requirement it had from its own succeeding tax year. Similarly, the transferor's excess distribution carryovers would be available to offset the transferee's distributable amount.119

It is important to note that the aforementioned provisions do not apply when a foundation transfers its assets to a private foundation(s) that its disqualified persons do not effectively control. In this case, the transferor foundation retains the requirement to distribute the amount calculated on its final return.120 Additionally, any excess distribution carryovers are not available to uncontrolled PF grant recipients. This result seems a bit inequitable and may explain one of the reasons the rulings apply only to controlled entities.

Section 4943. Whether the transfer causes a transferee foundation to have excess business holdings121 depends on the facts and circumstances of the combined ownership after the transfer. When the foundations involved in the transfers are effectively controlled, the disqualified persons, including substantial contributors, of both the transferor and the transferee foundations are treated as disqualified persons of the transferee in determining whether the transferee has excess business holdings. In addition, the transferee's holding period includes both the time that the transferred assets were held by the transferor(s) and the time they were held by itself. When the predecessor and successor foundation(s) are not commonly controlled, complete attribution of disqualified persons does not occur, although substantial contributors of the transferor foundation are treated as substantial contributors of the transferee foundation.122

Section 4944. The transfers of assets do not constitute investments jeopardizing the transferor foundation's exempt purposes. Whether or not an asset is a jeopardizing investment is determined at the time of its acquisition. The determination of jeopardy for an asset received by the transferee foundation would be based on the facts and circumstances existing when the transferor originally acquired it. If jeopardy is found to have existed, the transferee is responsible to remove the asset from jeopardy and pay the penalties due.

Section 4945. The transferor foundation is not required to exercise responsibility with respect to the transfers when all assets have been distributed to commonly controlled foundations.123 With respect to any outstanding grants it had previously made, the transferor foundation is required to exercise expenditure responsibility until the time it disposes of all of its assets and makes reports of such grants on its final Form 990-PF. Expenditure responsibility is an obligation that a private foundation incurs when it makes a grant to another private foundation, an organization exempt under a category of §501(c) other than (3), or to a nonexempt business for a charitable project or program-related investment.124