CHAPTER 18

IRS Filings, Procedures, and Policies

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is an important player throughout the life of an exempt organization (EO). Eligibility to receive tax-deductible donations and member dues, the privilege of receiving tax-free income, and other special advantages granted by federal, state, and local governments give significant economic value to exempt organizations. Tax-exempt status typically begins with recognition of qualification by the IRS and continues with the annual filing and potential scrutiny of the entity's Form 990, making it important to understand how that division of the IRS functions.1

The IRS Tax-Exempt and Government Entities (TE/GE) Division serves exempt organizations, employee plans, and government taxpayers. TE/GE matters are handled by the following centralized offices:

- Cincinnati, Ohio, office responsible for determination of exempt status by handling Forms 1023 and 1024 and subsequent issues involving changes in exempt status.

- Ogden, Utah, office responsible for processing Forms 990 and other tax compliance forms filed annually.

- Dallas, Texas, office responsible for examinations.

- Washington, D.C., office responsible for technical guidance, training, and overall supervision of the exempt organization matters.

Personnel in the IRS TE/GE Division are well trained, cooperative, and knowledgeable. Their attitude is normally supportive. They assume that EOs operate in good faith as they are supposed to: to benefit the public or their members. Their customary approach is to be helpful and to explain, the publications and handbooks are well written, and they offer good telephone assistance, as a rule. Increasingly, IRS guidance, publications, forms, and plans are available on its website.2

The publication titled Exempt Organizations Continuing Professional Education Technical Instruction Program, issued annually from 1979–2004, is still available (search for “EO tax training”) on the website. These CPE Texts contain extensive discussions of tax issues, with citations, and provide excellent history and context for many significant issues facing tax-exempt organizations.

18.1 IRS Determination Process

A nonprofit organization's first association with the Internal Revenue Service usually begins with the filing of an application—either Form 1023 or 1024—to request recognition of its qualification as a tax-exempt organization under Internal Revenue Code (IRC) §501(c) (hereinafter code section numbers are simply identified with the symbol “§”). Form 1023, Application for Recognition of Exemption under §501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, is submitted electronically on Pay.gov effective January 31, 2020. A 90-day grace period was permitted to obtain IRS approval for tax-exempt status as a charity. Careful study of the exemption application procedures outlined in the Internal Revenue Manual3 and the IRS instructions to the Form 1203 and 1023-EZ can contribute to success in receiving positive recognition. Once accepted, the applicant receives a Determination Letter and its eligibility is entered into the IRS Business Master File, the searchable databases listing qualified charities.

Form 1023-EZ and its instructions, originally released in 2015, were revised. It is available for modest nonprofits with expected annual gross receipts of $50,000 or less and assets of $250,000 or less. A seven-page eligibility checklist should be carefully used to evidence entities qualified to use the form, which excludes foreign, successors, LLCs, churches, schools, hospitals, and other types of applicants. Some state officials and professionals view the form negatively, saying it encourages fraud. The IRS examination of 1,000 random organizations found that nearly half weren't properly organized.

New Form 1024-A must now be used to seek recognition from exemption for a §501(c)(4) social welfare organization.

(a) Successful Application for Exemption

Form 1023, effective as this edition is prepared, uses a question-and-answer format designed to help a preparer anticipate issues that might cause the proposed organization not to qualify for tax exemption. Monitoring the results of Forms 1023 prepared and submitted by my office, plus experience with stalled applications brought by other professionals for help, reinforces the need to prepare Form 1023 with great care. A search for the title, Where Is My Exemption Application? on the IRS website on February 26, 2020, revealed that applicants could expect to be contacted within 90 days from submission of Form 1023-EZ and 180 days for Forms 1023, 1024, and 8940. After that time, one should call 877-829-5500 to check on status. They disclosed receiving more than 70,000 applications each year.

It is imperative that the application be prepared carefully so that the first reviewer in Cincinnati can approve the application without additional questions—a condition called “merit closing.” A second screening to address nontechnical issues like those in the following list is a stage that adds a month or two to the processing. About 50 percent or so are set aside to be assigned for technical review, which takes three to four additional months for completion.

The IRS website reports the following “top-ten tips” to shorten the tax-exempt application process:4

- Send user fee (check for latest on current instructions).

- Provide complete copy of organizing documents with any amendments and evidence of filing and approval by the state. Provide enough information about the organization's activities to show us how it will achieve the exempt purpose. Give the who, what, when, where, why, and how and explain past, present, and planned activities.

- Complete all required pages.

- Attach all required schedules.

- Include the month the organization's annual accounting period ends.

- Include the necessary financial data listed in the instructions.

- Don't forget to submit a copy of adopted bylaws, code of regulations, or any other document that sets out the organization's rules of operation.

- Be sure a director, trustee, principal officer, or other authorized individual in a similar capacity signs the form.

The IRS, reputedly because of concerns about terrorists, gives enhanced scrutiny to applications with plans to do foreign grant-making or to conduct programs overseas. Although not required, such applicants are well advised to state that the voluntary best practices regarding foreign activity will be followed.5

Another reason for diligence in preparing Forms 1023 and 1024 is that the highest scrutiny many organizations ever receive occurs during the determination process. The preparation of the forms is a healthy exercise for a new organization's creators. All aspects of the organization's structure, purposes, finances, and relationships are explored in the process of answering the questions. The gathering of the necessary information provides a good opportunity for strategic planning for the proposed organization and allows the organizers to focus on realizable goals and discard any ill-conceived or potentially nonexempt projects. Future activities that are imagined, but not fleshed out yet, should not be mentioned.

Applications subject to “Mandatory Review”6 are given extra scrutiny or delayed based on the character of activity proposed and cannot be closed. The list of applications that will also get special scrutiny include those of applicants whose primary activity is:

- All proposed adverse determinations.

- Determinations subject to IRC §6110 disclosure, including IRC §4945(g) advance approvals, unusual grant determinations, etc.

- Foreign organizations (not including those formed in U.S. territories).

- Group ruling approvals (not including declinations).

- An organization whose recognition of exemption was previously revoked or denied, except those revoked for failure to file returns.

- Religious and apostolic organizations under IRC §501(d).

- Applications that indicate actual or potential political campaign intervention activities (not including IRC §501(c)(4) approvals based on signed Letter 5228 representations).

- Management requests (senior manager's approval required).

It is extremely important that technical issues be considered, such as the relationships with the creators, board members, and employees. The reasonableness of salary or fees the organization plans to pay officials should be evident in relation to amount of revenue and expenditures reported on Part IX. Fund-raising activities that go beyond simply soliciting voluntary contributions7 must be analyzed for the possibility that the revenue will be considered to be unrelated business income or that private inurement might be given to the fundraisers.8

A common error in applications we see that are not readily approved is the submission of too much information and a failure to connect the information in various parts. It is critical to recognize that the terms used to define organizations qualifying for exemption connote different meanings to different persons. What is religious to one may be sacrilegious to another. The IRS specialist responsible for approving or denying an application construes the meaning of a proposed organization's exempt purpose within the context of his or her understanding of the rules and personal experiences. The length of Chapters 2 through 10 indicates the vagaries of the rules and different standards applicable to each type of exempt activity. Although the IRS specialists are knowledgeable and cooperative, they may not perceive a proposed organization in the same light as its creators. IRS Publication 557, Tax-Exempt Status for Your Organization, contains sample documents and provides a comprehensive resource for issues the IRS deems important in this regard.

(b) Timely Filing Critical

Qualification as a charitable organization under §501(c)(3) is not effective until the nonprofit organization properly notifies the IRS of its qualification by filing Form 1023.9 Additionally, a newly created charitable organization is presumed to be a private foundation unless its properly completed Form 1023 furnishes information reflecting its ability to qualify as a public charity. Organizations that qualify under other subsections of §501(c) are exempt without filing such notice, although the IRS may not accept a Form 990 unless Form 1024 is filed to establish the entity's qualification for exemption.10

Due Date . The application seeking exempt status is due 27 months from the organization's date of legal formation. If the filing is made before the IRS discovers the failure to file timely and the following factors apply, the IRS may extend the due date:

- Organization establishes it acted reasonably and in good faith.

- Interests of the government are not prejudiced by the extension.

- Failure was caused by intervening events beyond the EO's control.

- EO exercised reasonable diligence and was not aware of the filing requirements.

- Organization reasonably relied on written advice from the IRS or advice of a qualified tax professional.11

Effective Date of Exemption. A nonprofit's tax-exempt status is effective retroactively to its date of legal formation if the application is timely filed and accepted by the IRS. Applications not treated as timely filed are effective only from the date of submission to the IRS. A late-filing organization can request tax-exempt status as a (c)(4) organization for the period between formation and the effective (c)(3) exemption date; otherwise, income taxes may be due on income received prior to the effective date of exemption. To prove timely filing, the application should be sent by certified mail, return receipt requested, or a designated commercial delivery service. The postmark stamped on the envelope or delivery receipt transmitting the application determines the date of filing. Absent such a postmark, the date the application is stamped as received by the IRS is the receipt date.12 If the application is simply dropped into a postbox and is subsequently lost, the EO has no way to prove that it was timely sent.

Date Organization Formed. Timely filing is measured from the date the organization is formed, or the date it becomes a legal entity.13 The date of formation is the date on which the organization comes into existence under applicable state law. For a corporation, this normally will be the date the articles of incorporation are approved by the appropriate state official. For unincorporated organizations, it is the date the trust instrument, constitution, or articles of association are adopted.

Successful Applications. The IRS site says it may take up to 180 days for a Form 1023 application to be processed. (See the previous list of reasons for delay.)

If an applicant organization does not respond to an information request by the designated due date, EO Determinations will close the case without making a determination and will not refund any user fee paid. The concept is that an applicant who does not provide the requested information on time fails to establish that it meets the requirements for tax-exempt status. An organization whose case is closed under this procedure will have to submit a new application package and pay another user fee.

(c) Organizations that Need Not File

Two types of organizations are excused from filing Form 1023 to achieve tax-exempt status because they are automatically treated as tax exempt.14 Despite the exception, some such organizations find it desirable to file for a number of reasons. They may need written IRS approval of their exempt status to evidence eligibility to receive tax-deductible donations. Exempt status in some states is dependent on federal approval. Nonprofit mailing privileges, foundation grants, and other benefits of exempt status are most readily obtained by organizations that can furnish a federal IRS determination letter.

Churches. The first type of nonprofit organization excused from seeking recognition of its exempt status is a church,15 including local affiliates and integrated auxiliaries, and conventions or associations of churches. Even though filing is not required, IRS determination may be desirable to remove uncertainty in the case of an unrecognized sect or a branch of a church established outside the United States. Churches are generally granted favorable status; for example, they need not file an annual Form 990 and may receive more liberal local tax exemptions. Employment tax-reporting rules for ministers are also favorable.16

Modest Organizations. The second type that does not need to file is an organization with gross revenue normally under $5,000 that is not a private foundation. The term normally means that the organization received $7,500 or less in gross receipts in its first taxable year, $12,000 or less during its first two tax years combined, and $15,000 or less total gross receipts for its first three tax years combined. If an organization has gross receipts in excess of these minimal amounts during any year after its formation, it should file Form 1023-EZ within 90 days after the close of that year.17

Subordinate Nonprofits. A third type of organization that may not need to file Form 1023 is the subordinate organization covered by a group exemption, for which the parent annually submits the required information, as explained in the next subsection.

Change in Domestication. The IRS settled a long-standing controversy and abandoned its requirement that an organization exempt under IRC § 501(c)(3) that moves its state of domestication or incorporation to a different state had to submit a new Form 1023 to retain its tax-exempt status. The change to its state of domicile won't be considered a substantial change in the corporation's character, purpose, or methods or creation of a new entity. Additionally, the change in state of domicile was not deemed a substantial change in character, purposes, or methods of operation for the organization.18

§501(c)(4), (5), and (6) “Self-Declarers.” In fiscal year (FY) 2012, the IRS developed a project focusing on §501(c)(4), (5), and (6) organizations. These entities, which include social welfare organizations, labor, agricultural, horticultural groups, and trade associations, can declare themselves tax-exempt without seeking a determination from the IRS. The IRS wanted to learn more about whether such organizations have classified themselves correctly and are complying with applicable rules.

Non-§501(c)(3) organizations are now required to file Form 1024 within 27 months to ensure retroactive status.19 Reasons for this change include the new revocation procedures for failing to file Form 990 for three years and the difficulty in being certain of the operations of an organization for years in the past. The unanswered question is whether this new rule will be applicable for years prior to the date the new IRC §6033(j) became effective.

The IRS addressed the filing requirements for this group of organizations that were self-declarers, now subject to IRC §506 added to the tax code with the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015.20 A §501(c)(4) qualifying organization had not previously been required to seek approval for tax-exempt status. A newly formed (c)(4) entity is now required to notify the IRS of its existence no later than 60 days following its formation. Similarly, an existing (c)(4) that did not file Form 1024 or Form 990 before December 2015 was to send notice its name, address, date of formation, and purpose. No form is provided; the IRS expects that the Treasury Department will issue regulations. No notice is required until after that time. However, to allow time for issuance, the IRS is delaying its implementation of these rules. In June 2016, the IRS announced that §501(c)(4) organizations will not have to send the required notification to the IRS until 60 days after the regulations are issued, and advised that organizations should not send the notices until then. No failure to file penalties will be imposed on organizations that provide the notice by the due date in the regulations.21

(d) Group Exemptions

IRS Publication 4573 expands on the exemption and filing requirements and should be studied by prospective and existing group exemption holders. Helpful instructions on what to include in an application and subsequent annual filings are outlined.22

To reduce overall compliance efforts, the parent organization of an affiliated group of organizations centralized under its common supervision or control can obtain a group exemption letter recognizing tax-exempt status for itself and members of its group.23 A central organization may be a subordinate itself, such as a state organization that has subordinate units and is itself affiliated with a national organization. Subordinate chapters, posts, or local units of a central organization, such as the Girl Scouts of America or the National Parent–Teacher Association, need not separately seek recognition by filing separate applications if they are covered by the group letter. All of the subordinate EOs in the group must qualify for the same category of exemption (for example, §501(c)(3) for an educational group), although the parent can have a different category from its subordinates. The group may not include private foundations or foreign organizations. Form 14414, Group Rulings Questionnaire, was sent to 2,000 randomly selected central organizations in 2012, but results are not available.24 It was expected that the results of this survey might bring new guidance regarding the role and responsibilities of the central organization in relation to its subordinates. The parent organization files Form 1023 to obtain recognition of its own exemption. Then, it separately applies by letter to the IRS Key District for approval of its group.25 Subordinates created after issuance of the IRS group determination letter report only to the central EO for recognition of exemption, not to the IRS. Annually, the central organization submits information to update the master list of its subordinates with the IRS. The central organization must file its own Form 990. Affiliates may either file their own returns or be included in a group return. Look for a report of conclusions the IRS reached after compiling the data submitted on Form 14414, Group Rulings Questionnaire.

(e) Determination of Public Charity Status

Since 2006, a prospective §501(c)(3) organization is identified from its inception as either a private or public charity. Churches, schools, hospitals, and certain other types of charities qualify as public due to their proposed activities, without regard to their support sources.26 Those organizations classified as public charities for reasons of their sources of support, demonstrated in their Form 1023 with projections of revenue and descriptions of fund-raising plans, can also be treated as public from their inception. The former Advance Ruling Period system was eliminated.27 Effective for 2008 returns, a five-year public support calculation is submitted on Form 990, Schedule A, to evidence ongoing qualification as a §509(a)(1)/§170(b)(1)(A)(vi) or §509(a)(2) organization. The percentage of public support for the immediately past year and the current year is reflected. If the required 33⅓ percent support level is not sustained for both years, the entity may become a private foundation and Form 990-PF must be filed.28

(f) Reliance on IRS Determination Letter

After a positive determination letter is issued, the exempt organization can rely on the IRS's approval of its exempt status if there are no substantial changes in its purposes, operations, or character. This reliance is not necessarily available as an organization matures, adds new programs, or otherwise evolves. The IRS Form 990 instructions request disclosures to update any changes in activity and mission. The fact that an entity was dormant for a period after recognition may not prevent ongoing qualification.29

Checking Current Status. The current IRS status of an exempt organization can be found in two different IRS publications. The status of a (c)(3) organization is in IRS Publication 78, Cumulative List of Organizations Described in IRC §170(c) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 (Pub 78), now referred to as IRS Tax Exempt Organization Search. Three designations are provided. The IRS site says, “Click on one of the buttons below to search for:

- Organizations eligible to receive tax-deductible charitable contributions (Pub. 78 data),

- Organizations whose federal tax exemption was automatically revoked for not filing a Form 990-series return or notice for three consecutive years, or

- Form 990-N (e-Postcard) filers and filings.”

Note that an entity that is eligible to receive tax-deductible contributions may be either a public or a private charity, and a public charity may be a supporting organization. Caution is required because the income tax rules limiting the percentage of one's income that can be deducted and other rules that limit nonmarketable assets and “ordinary income assets” cause significantly different deductions. See §17.4(b) for more information regarding a private foundation's inability to rely on Tax Exempt Organization Search.

Names Missing from Publication 78. Absence from the list does not necessarily mean that the entity has lost its exempt status. Subordinates under a group exemption are not listed. The IRS, in 2010, purged the list of some 275,000 organizations that did not file required Forms 990.30 This policy omits a significant group of charities, including churches and their affiliates, and state colleges and universities that are not required to file Form 990. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and some state universities, among others, have specifically sought group exemption or individual recognition, despite the fact that filing is not required, to ensure their inclusion in Publication 78.

Lastly, a call to the IRS EP/EO Group in Cincinnati, Ohio, at 877-829-5500, may yield an answer, though not necessarily updated for IRB revocations. This number reaches a customer service representative who has the ability to look up an organization on the master list. Knowing the federal identification number of the organization makes the process easy. Name searches don't always yield the right answer due to the alphabetizing method or some change in the name since recognition.

(g) Exemption for State Purposes

Many states allow exemption from some or all income, franchise, licensing fees, property, sales, or other taxes to religious, charitable, and educational organizations and other §501(c) organizations. The process for obtaining such exemptions varies with each state and locality. Each new exempt organization should obtain current information and forms directly from the appropriate state or local authorities. Some municipalities and states also require registration by organizations that plan to solicit donations.

In Texas, by way of example, the state filing schedule starts when a nonprofit charter is filed with the secretary of state. There is no filing or registration for trusts or unincorporated associations. State exemption is automatically granted once the federal exemption is approved and a copy of that letter is furnished to the Comptroller's office. The organization may choose to furnish a copy of its completed Form 1023 and a letter requesting state exemption prior to receiving the federal approval. For a new organization expecting significant expenses subject to the sales tax, such as construction of facilities and furnishing of new classrooms, submitting Form 1023 and requesting Texas exemption may be very important.

18.2 Annual Filing of Forms 990

Almost all tax-exempt organizations must file a Form 990-N, 990-EZ, 990, or 990-PF each year. The 990 series of tax compliance forms is designed to accomplish many purposes that go far beyond simply reporting to the IRS. Accurate and complete preparation of the forms should be given top priority by a nonprofit organization. For most §501(c) organizations, the forms have entered the electronic age and are accessible for all to see on the websites of Guidestar or Foundation Center. The IRS implemented an electronic filing system for 990s for the 2004 filing season that is mandatory for organizations that otherwise file more than 250 electronic returns annually (W-2, W-2, 1099s, and the like) and have more than $10 million of assets.31 It plans to require electronic filing for all in coming years. Forms N and 990-EZ must be filed electronically. With data available in electronically searchable form, the IRS's ability to scrutinize 990 filers is significantly enhanced.

(a) Public Disclosure

In essence, and now in fact, Forms 990 are public documents. Yet another reason for a tax-exempt organization to pay careful attention to completion of the Forms 990 is the requirement that copies of the three most recent years’ returns be given upon request to those who pay a modest fee. Beginning in 1984, an organization had to allow anyone who knocked on its door to look at its Forms 990, 990-EZ, and 1023 or 1024 in its office. Beginning in 1999, a copy of the forms has to be furnished.32 Different response times and price apply depending on whether the request comes in the mail, with or without payment, or from a person physically appearing on the doorstep.33 The names of an entity's donors can be extracted from the public disclosure copy of tax-exempt organizations other than private foundations and 527 political organizations.34 Form 990-T, Exempt Organization Business Income Tax Return, must also be made available for public inspection by §501(a)(3) organizations.35 Part VI of Form 990 asks (but does not require) if the organization makes not only its Form 990 or 990-T available on its website, but also its audited financial statements and its organizational documents. The information can be posted on the organization's website in printable format. Penalties can be imposed for refusal to follow the disclosure requirements. Readers should verify the current status of these disclosure rules, including the Montana court challenge to the IRS policy of allowing 990 filers to omit names and addresses of donors from Schedule B.

Forms 990 are also used for a variety of state and local purposes. In many states, an EO satisfies its annual filing requirement by furnishing a copy of Form 990 to the appropriate state authority. Many grant-making foundations review Forms 990 in addition to or in lieu of audited financial statements, to verify an organization's fiscal activity. Open-records standards of some states also require that financial reports and records be open to the public.

(b) Design of Forms 990

Forms 990 provide a wealth of information. An organization's basic financial information—revenues, expenses, assets, and liabilities—is classified into meaningful categories to allow the IRS to evaluate the nonprofit's ongoing qualification for federal tax exemption under §501(c). The returns are also used by funders, states, and other persons to evaluate the scope and type of a nonprofit's activity. Information pertaining to the accomplishment of the organization's mission is presented: how many persons are served, papers researched, reports completed, students enrolled, and the like. Extensive details are reported for grants paid to support other organizations and disbursed as aid to the poor, sick, students, and others in need. Details of compensation paid to officials and key and highly paid employees and contractors and loans to or from persons who run and control the organization are reported, and affiliations with other nonprofit and for-profit entities are reported. The program accomplishment reports should be prepared particularly with a view to presenting the organization to funders and other supporters. Some use the information to compare nonprofit organizations statistically.

The returns also include a list of questions that fish for failures to comply with the federal (and, to some extent, state) requirements for donor and member disclosures, political and lobbying activity, transactions with nonexempt organizations, insider transactions, employment taxes, and more. In sum, the returns are designed to show that a nonprofit organization is entitled to maintain its tax-exempt status and provides a wealth of other information of interest to funders, constituents, and regulators.

Form 990 was significantly redesigned in 2008 to materially expand the information submitted. The IRS said its goal for the redesign (the first since 1979) was based on three guiding principles: enhancing transparency, promoting tax compliance, and minimizing the burden on the filing organization. To enable 990 filers to achieve this goal, however, the time needed to gather the information for the return increased for most. Those with complicated compensation arrangements, related entity structures, and other activities that raise compliance concerns must spend more time providing meaningful information to the public.

Form 990 consists of a 12-page core form and a series of 16 schedules designed to require reporting of information for only specific types of activities, such as lobbying, that the IRS wants to monitor. The following recommendations consider a few parts of the form that deserve special attention.

Mission and Program Accomplishments. On page 1, the form provides a choice to describe either the mission or the most significant activities, whichever the organization wishes to highlight. On page 2, a “brief description of the mission” is requested. We see 990s that disclose the same information on both page 1 and page 2. The instructions for page 2 say that the “mission articulated in the mission statement or otherwise adopted by the governing body” is to be entered, and suggests entering “none” if the governing body has not adopted or ratified the mission. This choice is clearly unacceptable. We recommend expressing the mission in words that fit on page 2 (no continuation attachment). The front page should briefly highlight significant accomplishments.

Limit Descriptions. The many parts of the form that request descriptions present a challenge because the space is limited. We prefer to avoid descriptions that carry over to Schedule O, which often appears at the end of what can now be a more than 50-page return. Whenever possible, carefully limiting the words to fit on the main body of the form can result in better communication of the organization's achievements, financial facts, and governance procedures.

Use Part III to Highlight Details of Accomplishments. Painting a picture of achievements with nonfinancial statistical information (such as the number of students taught, patients treated, books published, and other tally of persons served and goals reached) is requested in the bottom half of the second page. Remembering that the 990 is open for public inspection and is often carefully reviewed by donors, this data can be very important. Donated services or use of facilities not allowed to be reported in Parts VIII and IX should be disclosed here to evidence that additional source of public support.

Schedules—What to Attach. Pages 3–4 contain 38 questions that prompt attachment of Schedules A–R (there is no P or Q). Differing thresholds for providing more details on a schedule vary. Exhibit 18.1 contains a list to guide correct checking of “yes” or “no.”

Question 1 must be answered “yes” by all §501(c)(3) organizations, and Schedule A must be submitted to report public charity status, including those based on sources of revenue satisfaction of the 33⅓ percent threshold. A business league (c)(6) or any other type of 501(c) tax-exempt entity would enter “no.” A §501(c)(3) organization must answer Question 3 “no” to reflect that it did not engage in direct or indirect political campaign activities on behalf of or in opposition to candidates for public office. Similarly, Question 5 asks—and in this case the answer should be “yes”—whether a (c)(4), (5), or (6) filer did provide lobbying expense disclosures to its members.

Compensation Confusion. Part VII and Schedule J of the return reflect compensation as reported on Form W-2 or 1099.

EXHIBIT 18.1 FORM 990 Part IV—Chart of Thresholds/Time-Sensitive Answers

| Question | Schedule | Title | Threshold | Anytime during Year | At Year End |

| 1 | A | Public charity status | n/a | X | |

| 2 | B | Contributions received | $5,000 or 2% | X | |

| 3 | C | Political campaign activity | Any amount | X | |

| 4 | C | Lobbying activity | Any amount | X | |

| 5 | C | Lobby disclosure/proxy tax | Of any amount | X | |

| 6 | D | Donor-advised fund | Of any amount | X | |

| 7 | D | Conservation easements | Of any amount | X | |

| 8 | D | Art and collectibles | Of any amount | X | |

| 9 | D | Credit counseling/escrows | Of any amount | X | |

| 10 | D | Endowment funds | Of any amount | X | |

| 11 | D | Investments/other assets | Of any amount* | X | |

| 12 | D | Audited statements | n/a** | X | |

| 13 | E | School | n/a | X | |

| 14b | F | Foreign activities | $10,000 rev/exp $100,000 of assets | X | |

| 15 | F | Foreign grants—organizations | $5,000 | X | |

| 16 | F | Foreign grants—individuals | $5,000 | X | |

| 17 | G | Professional fundraising fees | $15,000 | X | |

| 18 | G | Fundraising revenue/events | $15,000 | X | |

| 19 | G | Gaming revenue | $15,000 | X | |

| 20 | H | Operate hospital | n/a | X | |

| 21 | I | Grants to organizations | $5,000 | X | |

| 22 | I | Grants to individuals | $5,000 | X | |

| 23 | J | Compensation of former officials Officials/highly paid |

Of any amount $150,000 |

X | |

| 24 | K | Tax-exempt bonds | $100,000 | X | |

| 25 | L | Excess benefit transactions | Of any amount | X | |

| 26 | L | Loans to officials | Of any amount | X | |

| 27 | L | Grant to related party | Of any amount | X | |

| 28 | L | Business relationships | Relative—$10,000 Business—see instructions |

X | |

| 29 | M | Noncash contributions | $25,000 | X | |

| 30 | M | Art/collectible gifts | Of any amount | X | |

| 31 | N | Liquidate/terminate organization | n/a | X | |

| 32 | N | Dispose/sell >25% assets | Of any amount | X | |

| 33 | R | Disregarded entity | Owned 100% | X | |

| 34 | R | List related entities | X | ||

| 35 | R | Controlled business entity | |||

| 36 | R | Transfers to controlled entity | See instructions |

* For line 13, program-related investments, only if amount exceeds 5 percent of assets.

** Answer is optional for organizations whose financials are included in consolidated audited statements.

Certified Public Accountants

Independent Board Members

A member of the governing body is considered “independent” only if all three of the following circumstances applied at all times during the organization's tax year:

- Member was not compensated as an officer or other employee of the organization or of a related organization (see Schedule R instructions), except as provided in the religious exception discussed below.

- Member did not receive total compensation or other payments exceeding $10,000 during the organization's tax year from the organization or from related organizations as an independent contractor, other than reimbursement of expenses under an accountable plan or reasonable compensation for services provided in the capacity as a member of the governing body. For example, a person who receives reasonable expense reimbursements and reasonable compensation as a director of the organization does not cease to be independent merely because he or she also receives payments of $7,500 from the organization for other arrangements.

- Neither the member, nor any family member of the member, was involved in a transaction with the organization (whether directly or indirectly through affiliation with another organization) that is required to be reported in Schedule L for the organization's tax year, or in a transaction with a related organization of a type and amount that would be reportable on Schedule L if required to be filed by the related organization.

Factors NOT Causing Lack of Independence

A member of the governing body is not considered to lack independence merely because of the following circumstances:

- Member is a donor to the organization, regardless of the amount of the contribution;

- Member has taken a bona fide vow of poverty and either (A) receives compensation as an agent of a religious order or a 501(d) religious or apostolic organization, but only under circumstances in which the member does not receive taxable income, or (B) receives financial benefits from the organization solely in the capacity of being a member of the charitable or other class served by the organization in the exercise of its exempt function, such as being a member of a section 501(c)(6) organization, so long as the financial benefits comply with the organization's terms of membership.

The numbers for compensation expense for officials reported on Part VII for the fiscal year will not necessarily agree with Part IX. Reporting of employee benefits for the purposes of the two different parts may differ due to calendar versus fiscal year reporting. Correspondingly, getting the amount right for officials who might be subject to the intermediate sanctions rules36 is critical. The instructions for Part VII have 11 pages and contain an amazing 2½-page detailed list of various benefits and where and if they must be included in the compensation reporting. Correct completion of these parts is important and can be challenging.

Tax Compliance Violations. The many questions on pages 3–5 contain potential for missteps regarding required tax compliance. Some questions, like number 5 in Part IV and number 6 in Part V that pertain to noncharitable organizations, give no clue as to the compliance obligation to which they apply. A “yes” response to the 14 questions in Part V can be positive or negative. For example, reporting the filing of 50 1099s on line 1a (independent contractors) and zero W-2 s on line 2a (no employees) for an organization that has an executive director and programs that indicate a sizeable paid staff is likely a red flag. Chapter 25 contains checklists and discussion of standards for distinguishing an employee from an independent contractor.

Areas for Potential IRS Scrutiny. The front page Questions 3 and 4 and Part VI, Questions 1 and 2 ask for the total number of board members and the number that are independent. The IRS concern for challenges to the exempt status of entities without independent directors is discussed in §2.2(k).

The IRS admits in the parenthetical phrase for Section B that the policies it recommends with questions in Part VI are not required by the tax code. Nonetheless, the IRS judges the ongoing tax exemption of an entity with a view to the quality of its governance.

The columns on Part VIII, Statement of Revenue, are designed to alert the IRS with column C reporting when a Form 990-T is required. Revenue from fund-raising events must be fragmented between the portion that is reportable as a contribution (line 1c of Part VIII) and the nondeductible amount (line 8a) that reflects the value of benefits provided and payments for auction or similar items in connection with the event. A negative amount, or loss, on line 8c indicates that the deductible portion might have been overstated.

Line 22 on Part X, Balance Sheet, can also be a hot button for “Liabilities due to current and former officers, directors, trustees, key employees, highest compensated employees, and disqualified persons.” Details reported in Schedule L provide fodder for scrutiny.

Standards for Issues Addressed on Certain Schedules. Guidance and discussion of technical standards and rules for content of various schedules can be found in the following chapters of this book.

- Schedule A—Chapter 11

- Schedule B—Chapter 24

- Schedule C—Chapter 23

- Schedule E—Chapter 5

- Schedule G—Chapters 20 and 24

- Schedule H—Chapter 4

- Schedule I—Chapter 17

- Schedule J—Chapter 20

- Schedule L—Chapter 20

- Schedule M—Chapter 24

- Schedule N—Chapter 26

(c) Who Files What

The numerous categories of exempt organizations are reflected in types of returns to be filed. Most, but not all organizations are required to file annual reports with the Internal Revenue Service. Churches and their affiliated organizations, in keeping with the Form 1023 rules for churches and divisions of states, or municipalities, do not file Forms 990, except possibly 990-T.37

Failure to file a required Form 990 for three consecutive years will result in revocation of tax-exempt status as of the filing due date of the third year.38 A new application for exemption, Form 1023, must be filed to reinstate exemption after this automatic revocation occurs, unless the organization shows reasonable cause for its failure to file the required notice or returns. The IRS adopted a lenient choice for modest organizations that had gross receipts less than $25,000.39 The IRS conducted an extensive educational effort to inform organizations of this requirement, urging organizations to sign up for its Exempt Organization Update e-mails by going to www.irs.gov/eo and clicking on EO Newsletter. More than 300,000 exempt organizations listed on the IRS database lost exempt status. In the author's practice, we continue to be asked to assist with this revocation problem during 2019 and 2020.

Another question that arises is when exempt status should be revoked for lack of activity. Assuming that the EO continues to file returns and its status isn't automatically revoked, the IRS may still revoke its exemption because it is not conducting activity described in its exemption application or prior returns. The “Dormancy” paragraph in §2.2 addresses this important issue.40

The types of EO returns and requirements follow:

- Form 990-N. All organizations, except for private foundations, exempt under §501(c) with gross receipts normally $50,000 or less must submit an e-Postcard (Form 990-N), Annual Electronic Filing Requirement for Small Exempt Organizations.41 The notice must be filed electronically and will contain the following information:

- Organization's legal name, plus any other names the organization uses

- Mailing and website address

- Employer identification number

- Name and address of principal officer

- Verification that gross receipts are still normally $50,000 or less

- Notification if the organization is no longer in business.

- Form 990-EZ. All exempt organizations, except for private foundations, whose gross annual receipts equal between $50,000 and $200,000 and whose total assets are normally less than $500,000 file Form 990-EZ electronically.

- Form 990. All other exempt organizations, including certain political organizations but not including private foundations; public charities also file Schedule A.

- Form 990-PF. This form is required for all private foundations annually, regardless of annual receipts or asset levels (yes, even if the PF has no gross receipts).

- Form 990-T. Any organization exempt under §501(a), including churches, state colleges and universities, and §401 pension plans (including individual retirement accounts) with $1,000 or more gross income from an unrelated trade or business must file Form 990-T.42

- Form 990-BL. Black lung trusts, §501(c)(21), file an annual Information and Initial Excise Tax Return for Black Lung Benefit Trusts and Certain Related Persons.

- Form 4720. Form 4720 is filed to report excise taxes and to claim abatement of such taxes imposed on §501(c)(3) charities and their insiders for conducting prohibited activities.

- Form 5500. One of several Forms 5500 may be due to be filed annually by pension, profit-sharing, and other employee welfare plans. Form 5500-EZ is filed for one-participant pension benefit plans and 5500 C/R is filed for organizations with fewer than 100 participants in their employee plans, among others.

- Form 5578. This form reports the nondiscriminatory policies of a tax-exempt school that does not file Form 990 (usually schools affiliated with churches).

- Form 5768. The form is filed to elect or revoke an election by a public charity to measure its permissible lobbying expenditures under §501(h).43

- Form 8940, Request for Miscellaneous Determination. Nine types of requests for public and private charities described in §18.3(a).44

- Forms 941, 1099, W-2, W-3, and other federal and state compensation reporting forms are filed to report payments to workers who perform personal services for tax-exempt organizations.45

(d) Federal Filing Not Required

The list of organizations required to file and those not required to file is reproduced each year in the instructions to Forms 990.46 For 2018, the descriptions and instructions regarding this matter covered 1¼ pages. The most recent version should be consulted if there is any question about filing requirements. The majority of nonfilers include governmental and state entities, churches, and disregarded entities.

(e) Filing Deadline

The due date for Forms 990 gives tax practitioners and exempt organizations a reprieve. Forms 990 are due to be filed within 4½ months after the end of the organization's fiscal year, rather than the 2½ months allowed for Form 1120 (for-profit corporations) and the 3½ months for Form 1040 (individual) and Form 1041 (trusts). An extension of time can be requested if the organization has not completed its year-end accounting soon enough for timely filing. For Forms 990-T and 990-PF, an extension of time to file does not extend the time to pay the tax.

The penalty for late filing is $20 a day (up from $10) for organizations with gross receipts of less than $1 million a year, not to exceed the lesser of $10,000 or 5 percent of the annual gross receipts for the year of late filing.47 The penalty can also be imposed if the form is filed incompletely. The penalty for a large organization (with more than $1,046,500 of annual gross receipts) is $100 a day, up to a maximum penalty of $52,000. There are penalties for filing failures for returns on which tax may be due (Form 990-T and Form 4720):

- §6651(a)(1) imposes a penalty for failure to file a tax return of 5 percent of the tax on the return for each month, not exceeding 25 percent in the aggregate.

- §6651(a)(2) imposes a penalty for failure to pay tax due on a return of 0.5 percent of the tax on the return for each month, not exceeding 25 percent in the aggregate.

These two penalties are mutually calculated so that the total penalty for failure to file a tax return and failure to pay the tax cannot exceed 25 percent of the tax.

- §6651(f) increases the percentages to 15 (instead of 5) and 75 (instead of 25) in cases of fraudulent failure to file.

- §6684 provides that if a person becomes liable for Chapter 42 tax and the cause is not reasonable, then he or she is subject to a penalty equal to the amount of such tax.

- §7203 provides that in the case of willful failure to file a return or pay tax, there is a maximum $25,000 ($100,000 for a corporation) penalty and imprisonment for up to one year.

(f) Group Returns and Annual Affidavit

The parent organization in general supervision or control of a group of subsidiary exempt organizations covered by a group exemption letter may assume the burden of filing a consolidated Form 990 for its subordinate organizations. The parent files its own separate 990. The subordinate member organizations of the group must each file separate 990-Ts.48 However, a group Form 990 can be filed for two or more consenting subordinate member organizations with the following attributes:

- Affiliated with the central organization at the time its annual accounting period ends.

- Subject to the central organization's general supervision or control.

- Exempt from tax under a group exemption letter that is still in effect.

- Uses the same accounting period as the central organization.

When the parent, or controlling member, of the group takes responsibility for filing a consolidated Form 990, each affiliate member covered by the group exemption must annually give written authority for its inclusion in the group return. A declaration, made under penalty of perjury, that the financial information to be combined into the group Form 990 is true and complete is included. A schedule showing the names, addresses, and employer identification numbers of included local organizations is attached to the group return. An affiliate choosing not to be included in the group return files its own separate return and checks a block on page 1 of Form 990. Each year, 90 days before the end of the fiscal year, the parent organization separately reports a current list of subsidiary organizations to the Ogden, Utah, Service Center.49

According to the Internal Revenue Manual (IRM), which contains directions for revenue agents, a taxpayer's reliance on the advice of a tax advisor is limited to issues that are generally considered technical or complicated. A taxpayer's responsibility to file, pay, or deposit taxes is generally not excused by reliance on the advice of a tax advisor. The IRS states:

When an accountant or attorney advises a taxpayer on a matter of tax law, such as when a liability exists, it is reasonable for the taxpayer to rely on that advice. Most taxpayers are not competent to discern error in the substantive advice of an accountant or attorney. To require the taxpayer to challenge the attorney, to seek a “second opinion,” or to try to monitor counsel on the provisions of the Code himself would nullify the very purpose of seeking the advice of a presumed expert in the first place… . By contrast, one does not have to be a tax expert to know that tax returns have fixed filing dates and that taxes must be paid when they are due… . It requires no special training or effort to ascertain a deadline and make sure that it is met. The failure to make a timely filing of a return is not excused by the taxpayer's reliance on an agent, and such reliance is not “reasonable cause” for late filing under §6651(a)(1).50

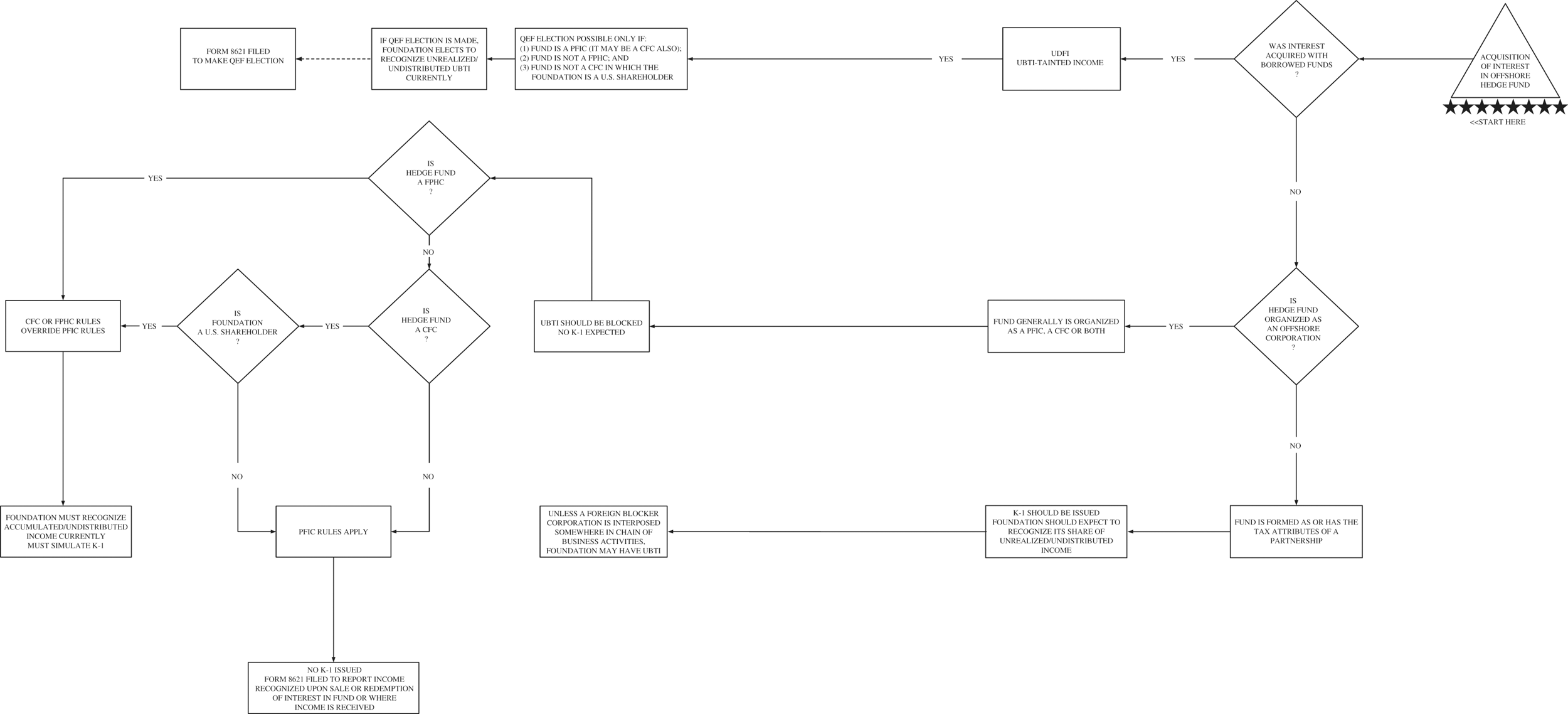

(g) Reporting Requirements for Offshore Investments

Exempt organizations have increasingly invested in offshore entities in recent years. In diversifying their portfolios, they are advised to purchase international securities, often through U.S.-based mutual funds.51 The tax reporting for such domestic funds and outright purchase of marketable securities of an international company through a U.S. financial institution do not bring any unique reporting requirements. The dividends, interest, and resulting capital gains from such passive security investments are reported on Forms 990 or 990-PF and subject to the excise tax on investment income of a private foundation.52

Some of these passive investments are made in the form of so-called offshore hedge funds organized in either partnership or corporate form. Income of a hedge fund organized as a partnership is treated as being earned proportionately by and reportable by each partner, including those that are tax-exempt.53 Therefore, the exempt investor receives and must report on Forms 990 an allocated part of the dividends, interest, capital gains, and other income from derivatives, options, notional contracts, and the like. The partnership reports the income and must furnish the organization a Form K-1 that contains details necessary for correct tax reporting.

Additional tax reporting obligations can arise from hedge fund investments. Most costly is normal income tax that may be due on part or all of the fund income that is classified as unrelated business taxable income (UBTI). The taxable income usually results when the fund uses margin or other borrowed funds, called acquisition indebtedness, to leverage the investments.54 When UBTI is realized, the exempt must report it on Form 990-T and pay the normal income tax as if it were a nonexempt corporation or trust. In order to offer protection to their investors, fund sponsors many times create a “blocker” structure to keep any taxable income from passing through the offshore hedge fund to the investor.

There are numerous variations on the theme of blocker structures, but the essence is that for the investment activities potentially producing UBTI, the corporate form shields UBTI from flowing through to the exempt investor. Most of these corporate offshore hedge funds are controlled taxwise by U.S. antideferral regimes for controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) and passive foreign investment companies (PFICs).

Exempt organizations coming under CFC rules must report income currently even if the income is merely accumulated instead of being distributed. A CFC is a foreign corporation in which significant “U.S. shareholders” own more than 50 percent of the total combined voting power or value on any day during the corporation's tax year.55 To be classified as a “U.S. shareholder,” the exempt must own at least 10 percent of the voting stock of the corporation. Of course, if the exempt has no UBTI from “debt-financing” its stock purchase, these antideferral rules merely affect the timing of reporting dividend income subject only to the 1 or 2 percent excise tax.

The foreign corporation tax rules under which an offshore hedge fund is most likely to qualify, assuming it accepts U.S. investors, is the PFIC. Like the CFC rules, the PFIC tax laws were established as an antideferral regime—or, at the least, a regime that would make income deferral an “expensive” proposition. A foreign corporation will be a PFIC if 75 percent or more of its gross income for the tax year consists of passive income, or 50 percent or more of the average fair market value of its assets consists of assets that produce, or are held for the production of, passive income.56

The general rule for a PFIC is that no taxes are due until there is an actual distribution of accumulated dividends or until the shareholder disposes of shares it owns. This allowable deferral of income is of little significance to exempts that have not “debt-financed” their purchase of PFIC stock, except to be concerned about proper reporting and timing of the dividend income subject to §4940 excise taxes. If an organization does have debt-financed stock, deferring the UBTI produced comes at a high price.

EXHIBIT 18.3 Offshore Hedge Fund Analysis

Whenever the deferred income is reported, all of the income is taxed as ordinary income even though some capital gains may have been included. In addition to the taxes due on the debt-financed income, an “interest penalty” must be paid.57 To avoid the ordinary income classification for all income and to avoid the interest penalty, the organization may wish to make a qualified electing fund (QEF) election. If such an election is made, the organization currently includes its pro rata share of the offshore hedge fund's ordinary and long-term gains in income for each tax year, and pays tax thereon even though such income and gains are not actually distributed.58

In addition to the complexities noted, there are other tax reporting forms to be filed in connection with foreign investments, particularly when the investment exceeds $100,000. If the investment entity is a foreign corporation, Form 926 and/or Form 5471 may be required. For PFIC corporate forms, Form 8621 may have to be filed. For a partnership investment entity, Form 8865 may be required. See Exhibit 18.3 for a chart reflecting the complexities of the reporting requirements for such investments. Prudent organizations will take the additional costs of meeting the filing requirements into account in evaluating the potential return on such foreign investment vehicles.

18.3 Reporting Organizational Changes to the IRS

As an exempt organization grows and evolves over the years, changes must be described annually on Forms 990. The returns ask:

- Did the organization undertake any significant activities during the year that were not listed on the prior Form 990, 990-PF, or 90-EZ?

- Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services?

- Were any significant changes made in its governing documents since the prior 990 was filed (and made before year-end)?

If the answer to the questions is “Yes,” a description of the changes is requested. Before 2008, an EO had a choice of either submitting information with its Forms 990 or submitting a report to Cincinnati EO Determinations. The instructions to the form now say the Cincinnati office “no longer issues letters confirming the tax-exempt status of organizations that report new services or significant changes.” To preserve exempt status in the event the activity is questioned, it is extremely important that full disclosure be made on Form 990 to invoke the statute of limitations and avoid retroactive revocation.

The term significant is not defined as it regards activities. In Part III of the Form 990 page 2, it is prudent to provide full descriptions of current activities with a notion of those that are new or discontinued. Regarding organization documents, the instructions for the question (line 4 of Part VI) are helpful. A description of the changes—not the documents themselves (except for name change)—is provided on Schedule O for a 990 and simply attached for a 990-PF. Examples of significant changes include changes to exempt purposes or mission, and number, composition, qualification, authority, or duties of officers or key employees, among others.

(a) Form 8940: Reporting Changes

The IRS released a one-page form to seek approval for eight changes in tax classification in 2011, Form 8940. Various fees are imposed and attachments very specific to the change are requested. Careful study of the instructions is important. The form is sent to the Cincinnati Office that has responsibility for determining initial qualification for exemption59 and making determinations that fall short of formal ruling requests. Changes they consider include:

- Advance ruling of termination of PF status60

- Approval of 60-month termination of PF status61

- Reclassification of public or private charity status62

- Approval of set-asides63

- Recognition of unusual grants64

- Advance approval of scholarship and individual grant plans65

- Advance approval of voter registration activities.66

- Exemption from 990 filing requirements67

- Change in or determination of supporting organization type68

Letter Rulings. In terms of IRS procedures, the letter ruling process is not only the most expensive, but also the most challenging. The time needed to receive a private letter ruling can be quite lengthy, and often the IRS will not rule due to their uncertainty or changing policy about the matter involved. A ruling can be requested only to gain approval in advance of a change, not to seek sanction for a fait accompli. If there are no published rulings or clear authoritative opinions on the subject, the organization may file a request for advance approval by seeking a ruling from the Exempt Organizations Division in the IRS National Office. When significant funds are involved or if disapproval of the change would mean that the organization could lose its exemption, filing of a ruling request may be warranted.

After a change has occurred in the form of organization or a major new activity is undertaken, however, the organization's only choice is to inform the IRS on the Forms 990 as described earlier. The fee for IRS approval for changes is updated annually and is now $30,000.69 For 2018, a ruling request fee was $28,500; this fee does not, of course, include the professional fees to prepare, submit, and defend the request.

(b) Fiscal or Accounting Year

A change that commonly occurs during the life of an EO is a change in its tax accounting year. Although some commercial, tax-paying businesses must secure advance IRS approval under IRC §446(e) to change their tax year,70 a streamlined system is available for EOs. An EO simply files a short-period Form 990 (or 990-N, 990-EZ, 990-PF, or 990-T) in a timely fashion.71 If a short-period return is filed by the fifteenth day of the fifth month following the new year-end, approval for the change is not required and it is not necessary to submit Form 1128 to Washington.72

For example, a calendar-year EO wishes to change its tax year to a fiscal year spanning July 1 to June 30. By November 15, a six-month return is filed to report the financial transactions for the short-period year (the six months ending June 30 of the year of change). If the organization has not changed its year within the past 10 years (counting backward to include the prior short-period return as a full year), the change is automatic. The words Change of Accounting Period are simply written across the top of the front page. A private foundation that changes its tax year must prorate certain calculations.73

Form 1128, Application to Adopt, Change, or Retain a Tax Year, must be filed in two situations: (1) the organization has changed its year-end within the past 10 years or (2) the return for the short period is not filed in a timely way. When the organization has previously changed its year, the automatic procedure is still followed if the return is filed within five months of the new year-end. In that case, Form 1128 is attached to the short-period return.

When the filing is late, the organization files Form 1128 with the IRS Service Center in Ogden, Utah, to request permission to change its year. If the request is filed within 90 days after the new filing deadline (February 15 in the preceding example), the organization can request that the IRS consider it a timely filing. If possible, the organization should explain that it acted reasonably and in good faith.74

Effective on May 10, 2018, the IRS will allow a taxpayer that early adopted a method of recognizing revenues described in new financial accounting standards issued by the Financial Accounting Standards Board and the International Accounting Standards Board an automatic change in its accounting method for the recognition of income for federal income tax purposes.75 Form 3115 should be submitted with the annual return, according to details set out in the announcement.

(c) Accounting Method Change

Once an organization adopts either the cash or the accrual method for 990 reporting purposes, Form 3115 is filed to request permission to change the method. Customarily, this situation occurs for an organization that, in its initial years, used the cash method and has now engaged certified professional accountants (CPAs) to issue audited reports of its financial condition. If the change merely involves adoption of FASB no. 116 to report pledges receivable and payable, permission is not required.76 An organization that wishes to change its overall accounting methods—for example, inventory valuation or calculation of depreciation—must file Form 3115 to request permission for the change. Because an exempt organization is not commonly paying tax, it can follow the simplified change procedures to seek approval for an accounting method change. To essentially receive automatic approval, Form 3115 is included in a timely filing (including extensions) of a Form 990. A copy of the form is filed with the IRS in Washington, D.C. Late applications can be filed, but will be considered only upon a showing of good cause77 and if it can be shown to the satisfaction of the commissioner that granting the extension will not jeopardize the government's interests. As EOs typically do not pay tax, the possibilities for such approval are good.

A change of accounting method necessitates reporting deferred or accelerated income or expenses that would have been reportable in the past if the new method had been used. Items “necessary to prevent amounts from being duplicated or omitted are taken into account” over a period of years and to mitigate the burden to a tax-paying entity are calculated.78 In most cases, the change has no tax consequence for an organization filing its Forms 990. The income or expense adjustments are reported in the year of change. When the change affects the organization's tax liability for unrelated business income, the most current procedures for reporting the change should be studied.

(d) Amended Returns

When a mistake is discovered after a Form 990 has been filed, the question arises whether an amended return should be filed or whether the change can simply be reflected in the next year's fund balance section as a prior-period adjustment. Except for a private foundation, there is usually no tax involved, so—in accountants’ language—the change is not material. The extra efforts involved in preparing an amended return may not be necessary.

Amendment is appropriate when the correction would cause a change in public charity status or when unrelated business income79 would increase or decrease, having an impact on a tax liability. As a rule, for an insignificant correction with no effect on retention of exempt status or tax liability, complete disclosure on the following year's return, along with inclusion of the omitted amounts, is acceptable. Importantly for certain public charities, the correction to revenue should be reported not only in Parts I and VIII of Forms 990, but also in Schedule A if public support ratios change.80

(e) IRC §509(a) Class Issues

IRC §509(a)(1) to (a)(2) or Vice Versa. Exempt organizations recognized under §501(c)(3) that receive revenues from many sources can often qualify as publicly supported under either §509(a)(1) or §509(a)(2). Qualification is based on percentage levels of revenues calculated using a five-year moving aggregate of financial support received. The calculation is made annually when the organization completes Schedule A of Form 990.81 The distinctions between the categories involve the differences in counting revenues as public rather than private.82 Passage of either test avoids classification as a private foundation, and there is not necessarily an advantage to either category.83

Sometimes changes in an organization's sources of support and exempt function revenues cause it to qualify for the other subsection; in some situations, the character of support might change from year to year, further complicating the issue. All too often the (a)(1) blank is checked when the organization's determination letter reflects (a)(2), or vice versa. When a change is indicated or prior Schedule A's have been incorrect, the organization should submit the correct information in the currently filed Form 990 filed in Ogden, Utah. The IRS does not issue amended or new determination letters in response to Schedule A information, but Form 8940 could be filed to request a new letter.

Ceasing to Qualify as a §509(a)(3) Organization. Failure to maintain qualification under IRC §509(a)(3) as a supporting organization84 could occur for either of two reasons:

- The organizational documents are altered in a manner that removes the requisite relationship with one or more public charities and the organization becomes a private foundation choosing its own grantees.

- A sufficient level of public support is obtained to allow the organization to convert to a §509(a)(1) or (2) organization.

In the first case, conversion to a private foundation (PF) requires no IRS approval, though most would favor overt sanction for the change. Preferably, the conversion is timed to occur at the end of the fiscal year. If not, a short-period final Form 990 would be filed at the end of the §509(a)(3) classification. A short-period Form 990-PF would then be filed beginning with the date of the change. Required minimum distributions,85 excise tax on investment income,86 and other PF sanctions would apply as if the organization were newly created on the date of conversion. Full disclosure of the changes would be furnished to the IRS in filing both returns.

In the second situation, the organization would continue to file Form 990, and the change would again be fully disclosed with the return for the year the change occurred. The dilemma regarding a change from (a)(1) to (a)(2) or vice versa also applies in this situation. Form 8940 can be filed to request a new determination letter.

Ceasing to Qualify as a Public Charity. Lastly, an organization classified as a public charity may become reclassified as a private foundation for one of two reasons:

- Its sources of support might fall below the requisite amount of public support needed to qualify under IRC §§509(a)(1) or (2).

- It ceases to conduct the activity qualifying it as a public charity or changes its governance structure.

For an EO with public status based on revenues, the calculation is made at the end of each year and affects the next succeeding year. Say, for example, the 2019 Form 990 shows an EO's public support fell to 25 percent of its total support (based on revenues received from 2015 to 2019). Unless the facts-and-circumstances test applies,87 or support level rises above 33⅓ percent in 2020, the EO would be reclassified as a private foundation in 2020. Regulations provide that for the first year of reclassification as a private foundation, a former publicly supported charity will only be subject to §4940 (excise tax on net investment income) and possibly §507(c) (termination tax).88 For succeeding taxable years, it will be a private foundation for all purposes.

A church, school, or hospital qualifies as a public charity because of the activity it conducts without regard to its sources of revenue. When such an EO ceases to so operate, it potentially becomes a private foundation on the date the change occurs. As the health-care industry reformed itself during the 1990s, the assets of tax-exempt hospitals were purchased by for-profit hospitals. Typically, the proceeds of the asset sale were then invested to produce income to conduct charitable grant-making programs. For several years following the sale, it is possible for the hospital to reclassify itself as a public charity based on its sources of support during the time it operated the hospital. Subsequently, it would become a private foundation unless it reformed its organizational structure to qualify as a supporting organization.

18.4 Weathering an IRS Examination

After securing tax exemption from the IRS Key District office and filing Forms 990 annually with the Internal Revenue Service Center, a call may be received from the IRS Exempt Organization Office in the EO's area. The knock on the organization's door comes in the form of a phone call from the IRS agent assigned to the case to the person identified as the contact person on the Form 990.

(a) Examination Methods

The IRS TE/GE Division conducts two broad categories of examinations: compliance checks and audits. A compliance check is usually conducted with correspondence asking for information on specific issues, such as fund-raising disclosures, fees paid to fundraisers, or employee classification issues. The request might ask that the EO send a sample of its donor disclosures and receipts. During former exams of this sort, an inaccurate or deficient response resulted in the IRS providing educational information to indicate the proper fashion in which donors are disclosed.

An audit is a review of an organization's books and records to determine qualification for tax-exempt status and potential tax liability. Audits may be conducted either by correspondence (letter or phone call with questions sent to EO to provide information) or in the field (agent reviews information in response to questions at the EO's location). A field examination involves a thorough review of governing instruments, pamphlets, brochures, and other printed materials, Forms 990 for three years, minutes of board and standing committee meetings, financial books and records of assets, liabilities, receipts and disbursements, auditor's report (if any), and other returns filed, including employment tax returns.89

Major exams in recent years focused on large universities and hospital systems. Other exams were planned by topic (bingo one year and used car donations in another). There have been very few examinations of modest organizations.

EO revenue agents use a governance check sheet to conduct the examination. The questions are parallel to those found in Part VI of Form 990 but embellish those questions by asking for probing details. For example, after asking if the board contemporaneously documents and retains the documents from its meetings, the check sheet asks the agent to say whether the exam was hindered by lack of necessary documentation. The Form 990 does not ask how often a quorum of voting board members met during the primary year under examination, but the check sheet does. Although the 990 instructions to the governance part say federal tax law generally does not mandate management structures, operational policies, or administrative practices, every organization is required to answer each question in Part VI. Then, if under examination, it will be asked many more details about its governance policies, as shown on the check sheet.

(b) Who Handles the Examination?

The first question to ask in connection with a field examination is its location. If a professional firm or advisor is involved, the examination might take place in their office, depending on the sophistication of the EO's accounting staff and the volume of records to be examined. The IRS has the authority to choose the site, though they are cooperative in that regard. Whatever the examination site, the IRS agent customarily visits the physical location in which the EO's programs are conducted.

For an exam conducted in the EO's facilities, a private office should be provided as the examiner's workspace, rather than a nook near the coffee bar or copy machine. Affording some privacy may prevent organization staff from involving themselves in the examination and minimize distractions that would waste the examiner's time.

(c) How to Prepare for the Audit

Good judgment is needed to cull through an organization's records to prepare for the auditor's appointment. For example, the auditor will ask to see correspondence files. In the case of a United Way agency in a major city, this cannot possibly mean every single correspondence file. Perhaps the correspondence of the chief financial officer or the executive director would be furnished, with an offer to furnish more correspondence if issues dictate.

Too often, some of the requested records are not in appropriate condition to be examined. The most troublesome records are too often the board minutes. It is important that a transcript of minutes be available for each meeting of the board of directors. Optimally, such minutes reflect the exempt nature of the organization's overall concerns. If, for example, a commercial-type operation is undertaken because it helps to accomplish exempt purposes, the minutes should reflect that relationship. Why did the organization enter into a joint venture with a theatrical show producer? Was it because the business put up all the working capital so that the organization experienced no financial risk for producing an opera production? Proving the relatedness of the venture for purposes of avoiding the unrelated business income tax can be facilitated with carefully documented minutes.

For private foundations, public charities, and civic associations, it is extremely important that the minutes of director and committee meetings document the basis on which salaries, fees, and benefits of personnel are approved. What the IRS calls “contemporaneous documentation of process” is required to evidence that an EO is paying reasonable compensation and not excess benefits subject to sanctions or self-dealing penalties.90