Chapter 3

Combining Arpeggios and Melody

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding how arpeggios combine with melodies

Understanding how arpeggios combine with melodies

![]() Combining arpeggios with melodies in the bass and in the treble

Combining arpeggios with melodies in the bass and in the treble

![]() Shifting the melody between the thumb and fingers

Shifting the melody between the thumb and fingers

![]() Practicing pieces with arpeggios and melodies

Practicing pieces with arpeggios and melodies

![]() Access the audio tracks at

Access the audio tracks at www.dummies.com/go/guitaraio/

Perhaps nothing is more satisfying to a classical guitarist than a composition that deftly combines arpeggios (chords played one note at a time) and melodies. And the reason is simple: To a listener, the piece sounds intricate and advanced (sometimes even virtuosic), yet typically, it’s not very difficult to play. So, with such pieces, you can amaze (or at least impress) your friends — without being a Segovia.

This chapter shows you how melody and arpeggios work together quite simply to create beautiful pieces, and we show you how to play them with ease.

Grasping the Combination in Context

Combining a melody with an arpeggio is often a matter of simply playing the notes you’re already fingering (rather than having to play additional notes) — the melody’s notes are usually contained within the arpeggio itself. Also, when you play an arpeggio, all or many of the chord’s notes are either open strings or are already held down (as a chord) by your left hand. Your right-hand fingers, too, are already in position — each resting in preparedness against its respective string. In other words, your hands hardly move for the duration of each chord!

How, you may wonder, can you simultaneously play notes with various values (that is, quarter notes, whole notes, eighth-notes, and so on) and keep them from sounding like a blur of overlapping pitches while also letting them all ring out as long as possible in each measure? The answer is that you actually play the notes at different levels of loudness — or, perhaps, different levels of emphasis. You do that by giving more oomph to some notes than to others.

The human touch (your touch, as determined by your understanding of the notes’ roles and interactions) imparts the proper textural feel to the listener — and that’s what makes playing such pieces so exciting. If you give the right amount of emphasis to the respective notes (even merely psychologically), the effect comes across to the listener, who hears the music not as just a blur of overlapping pitches but as a melody, an accompaniment, and a bass line. The technique for doing that varies, depending on whether you play the melody with your thumb or fingers.

The sections that follow present exercises that allow you to combine arpeggios with melodies in the bass (played by the thumb) and the treble (played by the fingers), and explores ways to draw the melody out of the background and into the limelight, where it belongs.

Going Downtown: Melody in the Bass

The melody of a classical guitar piece, though usually played by the fingers on the high strings (in the treble), is sometimes played by the thumb on the low strings (in the bass). (This concept applies to the piano, too, by the way. The right hand plays the melody of most pieces, though for a different effect, the melody can be placed in the left hand.)

You may find it easier to combine arpeggios with a melody played by your thumb than by your fingers. For one thing, your thumb usually plays on the beat (rather than between the beats, as the fingers do). For another, you have no decisions to make about which finger plays the melody; that is, your thumb, acting alone, plays nothing but the melody notes while your fingers play nothing but the accompaniment (the higher notes of each arpeggio).

Don’t worry about having to hunt down the melody in a piece. The melody usually reveals itself soon enough when you start to play, just in the way the composer or arranger wrote the notes. (Sometimes the written music itself even offers clues, such as giving the melody its own stem direction.) After you’re able to hear where the melody falls, you can work to bring it out further, using slightly stronger strokes on the melody notes themselves. Or, if the piece has no melody at all (which sometimes happens in short passages between melodic phrases), you hear that, too, and give no emphasis to any particular notes.

Playing a bass melody within arpeggios

How do you bring out the notes when the melody is in the bass line? Just play them a little louder (striking them a little harder) than the other notes, and make sure the other notes are consistent with each other in loudness.

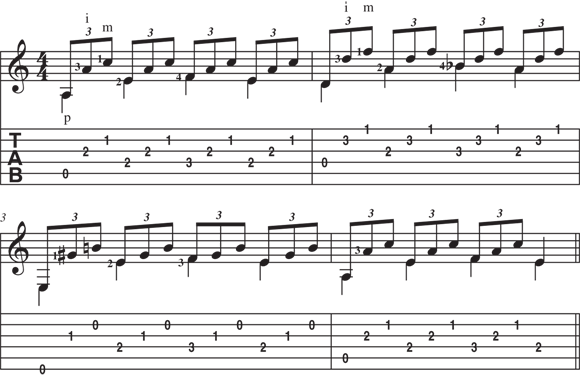

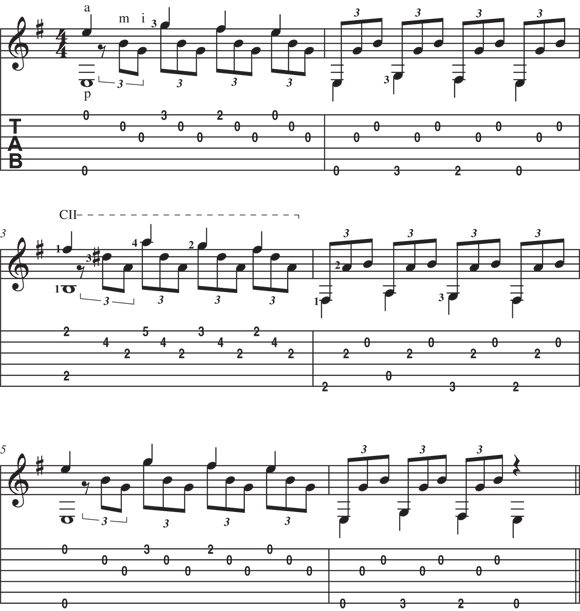

Figure 3-1 is an exercise that offers you an opportunity to practice the basic technique of combining arpeggios with a bass melody without having to worry about any of the complicated rhythms or unusual left-hand fingerings that real-life pieces may contain.

Note that the first note of each triplet group has a downward stem (in addition to an upward stem). Those downward stems tell you not only to play those notes with your thumb but also to play them as quarter notes; in other words, to let them ring throughout the beat.

Now, alert reader that you are, you may point out that one of the rules of arpeggio playing is that all the notes of an arpeggio should ring out (rather than be stopped short) — so all those bass notes would sound as quarter notes anyway. And you’re right. So in reality, those downward stems on the first note of each triplet group tell you not only to play them with the thumb and to let them ring out but also to bring out those thumb notes so that a listener hears them as an independent melody.

Measure 2 presents an interesting right-hand fingering dilemma. Normal, or typical, right-hand position has the index finger assigned to the 3rd string, the middle finger to the 2nd, and the ring finger to the 1st. Also, you generally try not to move the right hand itself, if at all possible. For those reasons, you’d expect to use fingers m and a to play the top two notes of the D minor arpeggio.

But another rule of arpeggio playing says that you should use the strongest fingers whenever possible — and the combination of i and m is stronger than that of m and a. So, according to that rule, you should use i and m for the top two strings (even though you have to move your right hand across the neck a bit). Hence the dilemma.

FIGURE 3-1: Arpeggio exercise with melody in bass.

Practicing making a bass melody stand out

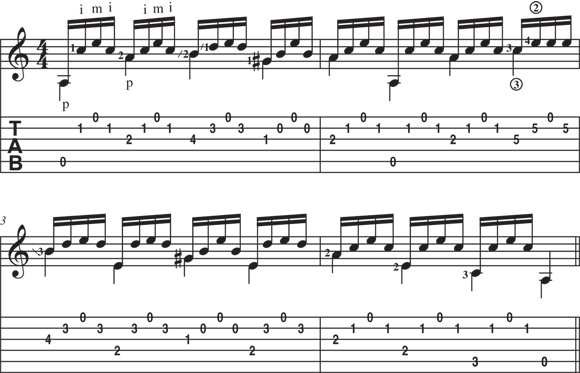

FIGURE 3-2: Study in A Minor, with the melody in the bass.

First, the notes are sixteenth, which means that they move along rather briskly. So start out by practicing slowly, then gradually increase the tempo. Second, the bass notes — because they’re all chord tones that occur at the beginning of each four-note group — have a tendency to sound like nothing more than simply the first note of each arpeggio. So it’s your job to make them especially melodic; that is, bring them out forcefully — but smoothly and sweetly — so that a listener hears a “tune” in the bass. Finally, you play some of the notes on strings you may not expect. Check out measure 2, beat 4, for example, where, in order to preserve the right-hand pattern (and flow), you play the C on the 3rd string, and the repeated E’s alternate between the 2nd and 1st strings.

For ease of playing, pay special attention to the left-hand fingering (and especially to the guide finger indications). And for an effective performance, keep the rhythm as even as possible.

Moving Uptown: Melody in the Treble

Melodies in the bass are a bit easier to combine with arpeggios than are melodies in the treble. However, arpeggio pieces with melodies in the treble are actually more common than those with melodies in the bass, and in this section we look at the technique you use to play such pieces.

Playing arpeggios with the melody in the treble rather than the bass can be a bit trickier for a few reasons, as the following list explains:

- Question of fingering: Technically, any given melody note can be taken with any available finger — i, m, or a — and it’s often up to you to decide which to use. (See nearby sidebar for a refresher on the p-i-m-a system.)

- Use of the ring finger: Because the i and m fingers usually play accompaniment notes on the inner strings, the a finger takes many melody notes. The problem is that the melody notes must be emphasized, but the ring finger is the weakest.

- Question of right-hand technique: As explained in the sections that follow, you have more than one way to bring out a treble melody from an arpeggio, and it’s up to you to decide which technique to use.

- Use of rest strokes: Whereas you play arpeggios with a melody in the bass with free strokes only, you generally combine rest strokes and free strokes when you play arpeggios with a melody in the treble.

Complexity of notation: Standard music notation for arpeggio pieces with a melody in the treble often requires the indication of three separate parts, or voices — one each for the melody, the accompaniment (usually filler notes on the inner strings), and the bass. Normally, stem directions tell you which notes belong to which part (for example, notes with stems up are melody and notes with stems down are bass). Depending on the musical context (or sometimes simply on the amount of available space), the accompaniment notes may be stemmed either down (sometimes making them hard to distinguish from bass notes) or up (sometimes making them hard to distinguish from melody notes). Sometimes, at the whim of a composer or arranger, the melody and accompaniment notes are combined into a single voice (as a continuous flow of upstemmed eighth notes, for example), and it’s up to you, using your ear, to discover the real melody.

Complexity of notation: Standard music notation for arpeggio pieces with a melody in the treble often requires the indication of three separate parts, or voices — one each for the melody, the accompaniment (usually filler notes on the inner strings), and the bass. Normally, stem directions tell you which notes belong to which part (for example, notes with stems up are melody and notes with stems down are bass). Depending on the musical context (or sometimes simply on the amount of available space), the accompaniment notes may be stemmed either down (sometimes making them hard to distinguish from bass notes) or up (sometimes making them hard to distinguish from melody notes). Sometimes, at the whim of a composer or arranger, the melody and accompaniment notes are combined into a single voice (as a continuous flow of upstemmed eighth notes, for example), and it’s up to you, using your ear, to discover the real melody.

To bring out the melody in the treble, you have to make it either louder than, or different in tone from, the other notes. You can do this simply by:

- Making the melody notes sound stronger than the others by playing them with rest strokes (and the accompaniment notes with free strokes). You can also try the techniques in the following bullets, but this technique — the use of rest strokes for melody notes — is generally used by classical guitarists, and it’s the one you should strive to perfect.

- Striking the melody notes harder than the others (as you do when you bring out a bass melody with the thumb).

- Making the melody notes brighter-sounding than the others by using more nail when you strike them (that is, if you play with a combination of flesh and nail, use more nail than flesh on the melody notes, and more flesh than nail on the accompaniment notes).

Playing a treble melody within arpeggios

Practice Figure 3-3 using rest strokes on all the melody notes. Start out playing slowly (but evenly), then gradually increase your speed. Follow the left-hand fingerings to ensure that you can hold down each chord with your left hand for as long as possible. If necessary, listen to Track 107 to hear how the piece works rhythmically and how the separate voices interact.

FIGURE 3-3: Arpeggio exercise with melody in treble.

Practicing making a treble melody stand out

Note that the bass notes sustain throughout each arpeggio, but in measure 3, fingering requirements force you to stop the bass from ringing one beat early (as the finger that plays the bass note, the first finger, is suddenly needed on the 1st string to play the last melody note of the measure).

FIGURE 3-4: Study in C, with the melody in the treble.

Mixing Up Your Melodic Moves: The Thumb and Fingers Take Turns

Not all arpeggiated passages are as straightforward as those you encounter earlier in this chapter — where the melody occurs consistently in either the treble or bass part. In some cases the melody moves back and forth between the treble and bass, and in others the treble and bass parts contain melodic motion simultaneously. Fortunately, the playing of such pieces requires no new techniques, but it does require a heightened awareness (on your part) of where the melody is and how to bring it out.

Playing a shifting treble-and-bass melody within arpeggios

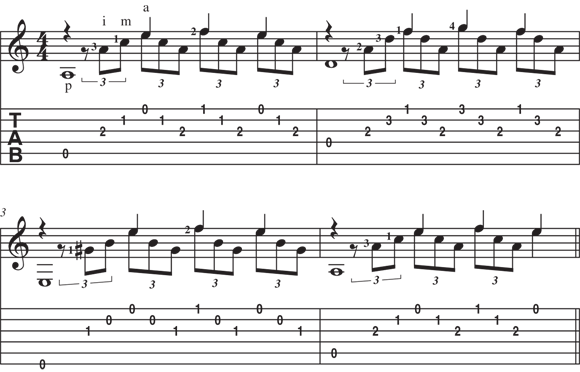

FIGURE 3-5: Arpeggio exercise with melody alternating between treble and bass.

Practicing making a shifting melody stand out

FIGURE 3-6: Waltz in E Minor, with the melody alternating between the bass and treble.

In measures 3 and 4, note that in the written notation, for the sake of simplicity, the composer combined the melody (the upstemmed notes on the beats: F♯-G-F♯, G-F♯-G) and the accompaniment notes (the open B’s) into a single voice. What you need to realize is that although the melody notes are written as eighths, you render them in performance as quarters.

Playing Pieces That Combine Arpeggios and Melodies

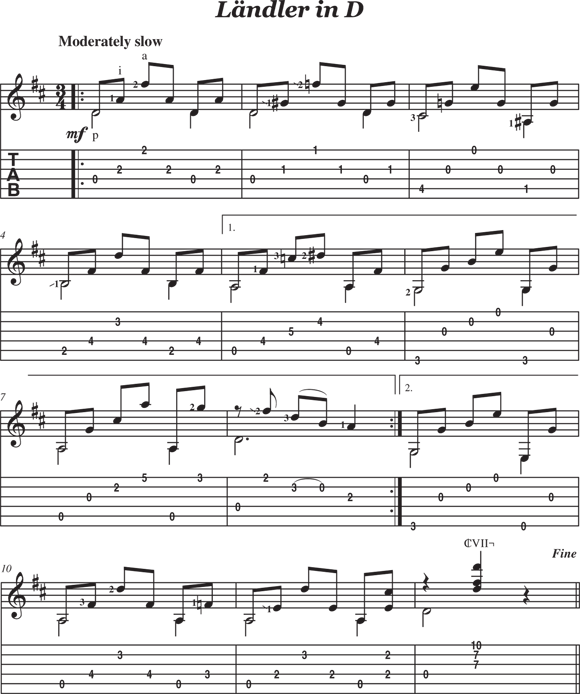

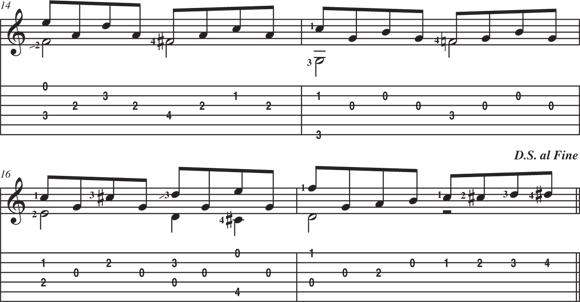

Ländler in D (Track 111): A ländler is an Austrian folk dance in 3/4 time (or a musical piece to accompany such a dance), and this one was composed by 19th-century Hungarian guitar virtuoso Johann Kaspar Mertz.

Play notes with stems both up and down (generally on beats 1 and 3 in the first section and on each beat in the second) with the thumb, and bring them out as a melody (and remember to hold down all the notes of each measure as a chord whenever possible).

In measures 13 through 20, you play only a single note after each bass note, and so the patterns aren’t true arpeggios. That is, an arpeggio is a “broken chord,” and a chord, by definition, contains three or more notes. However, in that section, if you think of each beat as a two-note “chord,” then you can see that you’re still playing in arpeggio style (meaning that the thumb and fingers alternate).

In measures 13 through 20, you play only a single note after each bass note, and so the patterns aren’t true arpeggios. That is, an arpeggio is a “broken chord,” and a chord, by definition, contains three or more notes. However, in that section, if you think of each beat as a two-note “chord,” then you can see that you’re still playing in arpeggio style (meaning that the thumb and fingers alternate). In two-note arpeggio figures (as in measures 13 through 20), your thumb, of course, plays all the bass notes. You play the treble notes, if they change pitch from beat to beat, by alternating between i and m. But if the pitch of the treble notes remains constant, as in this instance, you usually play the notes with just one finger — either i or m (depending on which strings your thumb plays and how close they are to the treble string in question). Try measures 13 through 20 first using i for all the open E’s and then using m, and see which fingering you prefer.

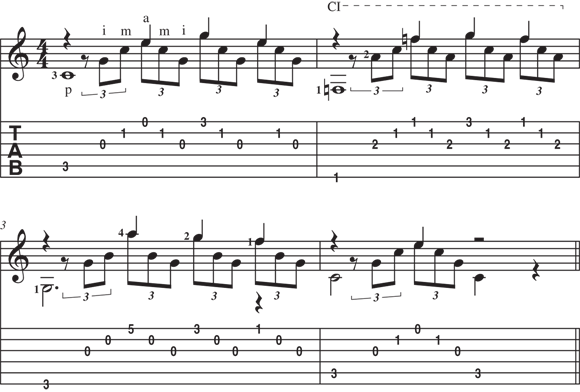

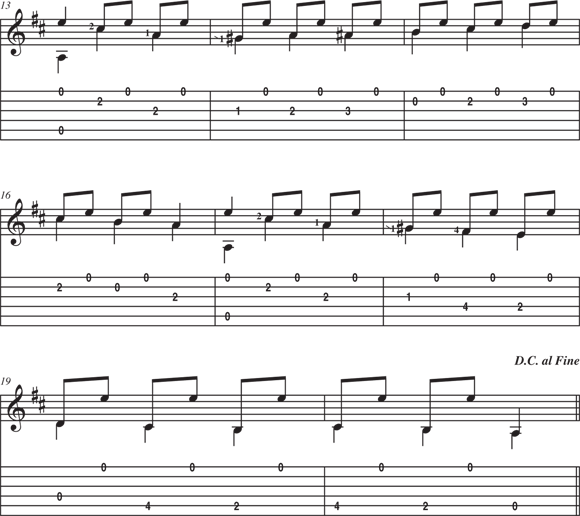

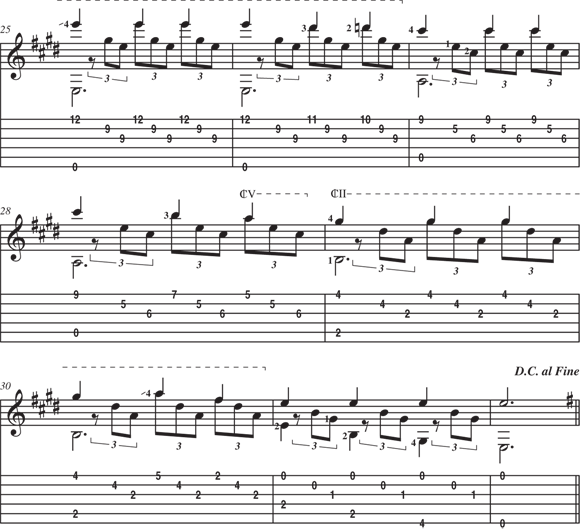

In two-note arpeggio figures (as in measures 13 through 20), your thumb, of course, plays all the bass notes. You play the treble notes, if they change pitch from beat to beat, by alternating between i and m. But if the pitch of the treble notes remains constant, as in this instance, you usually play the notes with just one finger — either i or m (depending on which strings your thumb plays and how close they are to the treble string in question). Try measures 13 through 20 first using i for all the open E’s and then using m, and see which fingering you prefer.“Romanza” (Track 112): This is one of the all-time most famous classical guitar pieces; virtually every classical guitarist encounters it and plays it at some time or another. It is known by several titles, including “Romanza,” “Romance,” “Spanish Romance,” and “Romance d’Amour.” In most collections that include it, the composer is said to be anonymous, which may lead you to believe that the piece was written hundreds of years ago. Actually, the piece isn’t nearly that old, and the identity of the composer isn’t so much unknown as it is in doubt, or in dispute; a number of composers have claimed authorship of this piece.

As indicated, play all the melody notes with the a (ring) finger, and bring them out by emphasizing, or accenting, them slightly. Even though a may be the weakest finger, it’s charged with the important work of carrying the melody here.

What makes this piece relatively easy is the great number of open strings (as is typically the case with pieces in the key of E minor). What makes it difficult (besides the many barre chords) are the left-hand stretches in measures 10, 27, and 28. Isolate those measures and practice them separately, if necessary. And what makes the piece interesting (besides its inherent beauty) is the shift from the minor to the major key in the second section (at measure 17), and then the return to the minor key after measure 32. Note the double-sharp in measure 20, which tells you to play the note two frets higher than the natural version.

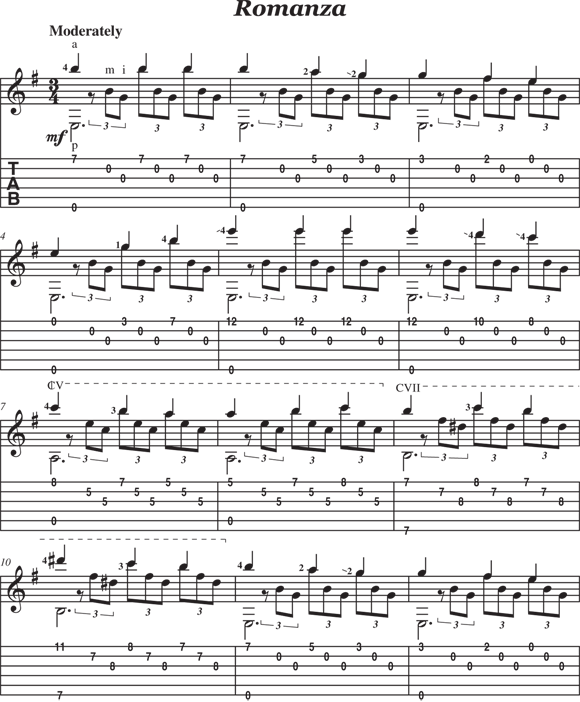

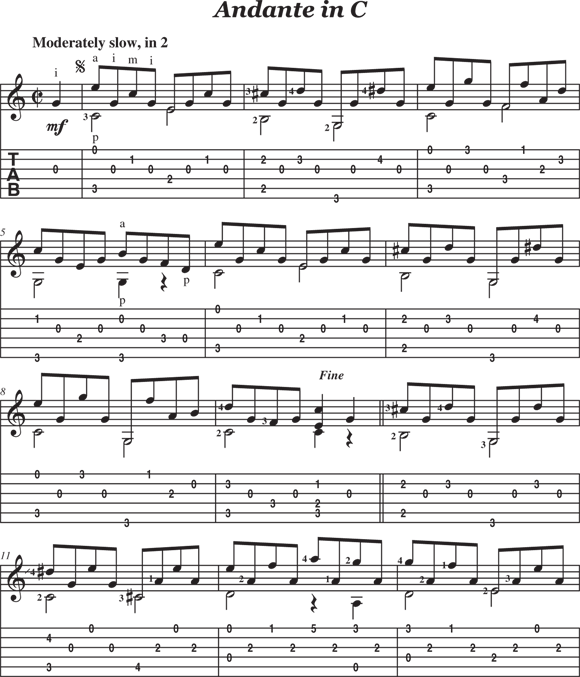

Andante in C (Track 113): Just as Carulli did with Waltz in E Minor in Figure 3-6, so too did early 19th-century Italian guitar virtuoso Matteo Carcassi combine the melody and accompaniment notes into a single part. But whereas in the Carulli piece it’s obvious which notes are melody and which are accompaniment, this piece has a certain amount of ambiguity. Sometimes, as in the first two full measures, it’s easy to discern the melody: It’s made up of the notes that occur at beats 1, 2, and 4 (and which you should render in performance as a quarter note, a half note, and a quarter). But in the next measure, is the A on beat 4 melody or accompaniment? And in the measure after, are the final three notes (G, F, and D) melody or accompaniment? Only Carcassi could answer definitively, but because you can’t ask him, it’s up to you, the performer, to answer such questions by bringing out (or not bringing out) those ambiguous notes accordingly.

If you look at the piece’s second section (measures 10 through 17), you see that the upper voice contains a melody (albeit intermingled with accompaniment notes in the same voice) and that the bass part also moves melodically. This really gives you an opportunity to practice your melody/arpeggio chops (or to display them, as the case may be). All at once you have to decide which of the upstemmed notes you consider the real melody notes, to bring out those notes from the notes that function merely as accompaniment, and to also bring out the separate melody that occurs in the bass!

Because Carcassi’s notation leaves some unanswered questions, you may wonder why he didn’t employ three separate voices in his notation — one for the upper melody, one for the filler (accompaniment) notes, and one for the bass line. He could have, and some pieces are so notated. However, the risk is that the notation is so complicated that it’s counterproductive. That’s why Carcassi chose to notate the piece as he did. But that doesn’t mean a different composer may have notated it as three separate voices.

Because Carcassi’s notation leaves some unanswered questions, you may wonder why he didn’t employ three separate voices in his notation — one for the upper melody, one for the filler (accompaniment) notes, and one for the bass line. He could have, and some pieces are so notated. However, the risk is that the notation is so complicated that it’s counterproductive. That’s why Carcassi chose to notate the piece as he did. But that doesn’t mean a different composer may have notated it as three separate voices.

The important point is that when you have a situation in which those right-hand fingering rules conflict, the “strong fingers” rule takes precedence over the “minimize motion” rule, and thus we indicate in measure 2 that you play the top two notes of the D minor arpeggio with i and m.

The important point is that when you have a situation in which those right-hand fingering rules conflict, the “strong fingers” rule takes precedence over the “minimize motion” rule, and thus we indicate in measure 2 that you play the top two notes of the D minor arpeggio with i and m.