Chapter 2

Playing Lead

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Learning scales, arpeggios, and lead patterns

Learning scales, arpeggios, and lead patterns

![]() Reading notation

Reading notation

![]() Practicing riffs

Practicing riffs

![]() Improvising good solos

Improvising good solos

![]() Access the audio tracks at

Access the audio tracks at www.dummies.com/go/guitaraio/

Lead guitar is the most spectacular and dazzling feature of rock guitar playing. Lead guitar can embody emotions that run the gamut from mournful and soulful to screaming, frenzied abandon — sometimes in the same solo. Whereas riffs are grounded, composed, and can manifest their power through their unflinching solidity, lead is beckoned by the music to launch into divinely inspired flights of fancy, to be forever soaring.

The greatest lead guitarists, from Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix to Eddie Van Halen and Steve Vai, have all been able to soar, but they have also all been disciplined masters of their instruments. They resolved the ultimate artistic paradox: total freedom through total control.

As you begin developing the basic technique for playing lead, never forget that your playing possesses the potential for evoking enormous emotional power. And kick over a few amplifiers while you’re at it too!

Taking the Lead

You must play many before you can play one, Grasshopper.

This probably fake saying certainly applies to rock guitar playing, because you need to learn to play chords (note groupings of at least three notes) before you can learn single-notes — the stuff of leads.

Actually, you don’t have to learn chords before lead, but in rock guitar it’s a good idea, at least from a technical standpoint, because when playing rhythm you don’t have to be as precise with your right-hand motions. Most beginning guitarists find striking multiple strings easier than plucking individual ones.

But the time has come to venture into the world of single-note playing, where you pick only one string at a time, and which string you play is critical. Single-note playing also involves a lot more movement in the left hand.

Single-note playing provides a variety of musical devices. Four of the most important ones for playing rock include:

- Melody: A major component of single-note playing on the guitar is melody. Melody can be the composed tune of the song played instrumentally, or it can be an improvised break or solo, using the melody as the point of departure.

- Arpeggio: An arpeggio is when you play a chord one note at a time, so, by definition, it’s a single-note technique. You can use arpeggios as an accompaniment figure or as lead material, as many hard rock and heavy metal guitarists have done. Lead guitarists burn up many a measure just by playing arpeggios in their lead breaks, and the results can be thrilling.

Riff: A riff is a self-contained musical phrase, usually composed of single notes and used as a structural component of a song or song section. A riff straddles the line between melody and rhythm guitar, because it contains elements of both. A riff is typically repeated multiple times and serves as a backing figure for a song section.

Think of the signature riffs to the Beatles’ “Day Tripper” and “Birthday,” the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction,” Aerosmith’s “Walk This Way,” Cream’s “Sunshine of Your Love,” Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love” and “Black Dog,” Ozzy Osbourne’s “Crazy Train,” and Bon Jovi’s “You Give Love a Bad Name.” These are all songs based on highly identifiable and memorable riffs.

Riffs aren’t always composed of just single notes. Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water” and Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man” are actually composed of multiple-sounding notes (power chords) moving in unison. And two or more guitars can play riffs in harmony too. The Allman Brothers and the Eagles are famous for this.

- Free improvisation: This isn’t a recognized technical term, but a descriptive phrase of any lead material not necessarily derived from the melody. Free improvisation doesn’t even have to be melodic in nature. Wide interval skips, percussive playing, effects used as music, and melodic note sequences (such as patterns of fast repeated notes, or even one note) can all contribute to an exciting lead guitar solo or passage.

The terms lead, melody, single line, riff, solo, and improv are all types of single-note playing and are often used interchangeably. The phrase “single-note playing” is a little cumbersome, so you can refer to any playing that is not rhythm playing as lead playing, even if it’s to indicate playing a riff.

Sometimes the featured guitar can consist of a strummed chordal figure. The guitar break in Buddy Holly’s “Peggy Sue” and the opening riff to the Who’s “Pinball Wizard” are two standout examples of the rhythm guitar taking a featured role.

Holding the pick

You don’t need to hold the pick any differently for lead playing than you do for rhythm playing. Have the tip of the pick extending perpendicularly from the side of your thumb, and bring your hand close to the individual string you want to play.

You may find yourself gripping the pick a little more firmly, especially when you dig in to play loudly or aggressively. This is fine. In time, the pick becomes almost like a natural extension of one of your fingers.

Attacking the problem

The sounding or striking of a note, in musical terms, is called an attack. It doesn’t necessarily mean you have to do it aggressively, it’s just a term that differentiates the beginning of the note from the sustain part (the part that rings, after the percussive sound).

To attack an individual string, position the pick so that it touches or is slightly above the string’s upper side (the side toward the ceiling) and bring it through with a quick, smooth motion. Use just enough force to clear the string, but not enough to sound the next string down.

This motion is known as a downstroke (see Book 2 Chapter 4 for more on downstrokes and upstrokes). When playing lead, you usually strike only one string. To play an upstroke, simply reverse the motion. In rock guitar, rhythm guitarists tend to favor downstrokes. Downstrokes are more forceful and are generally used to accentuate notes to play even, deliberate rhythms. Alternating downstrokes and upstrokes is called alternate picking (covered later in this chapter) and is essential for playing lead guitar.

Playing Single Notes

Single-note playing requires less arm movement than playing chords does, because most of the energy comes from the wrist. You may be tempted to anchor the heel of the right hand on the bridge, which is okay, as long as you don’t unintentionally dampen the strings in the process.

As you move from playing notes on the lower strings to notes on the higher strings, your right-hand heel will naturally want to adjust itself and slide along the bridge. Of course, you don’t have to anchor your hand on the strings at all, either; you can just let your hand float roughly in the area above the bridge.

Even when you play loud and aggressively, your right-hand movements should remain fairly controlled and contained. When you see your favorite rock stars on stage flailing away, arms wildly windmilling in circular motions of large diameters, that’s rhythm playing, not single-note playing.

You’ll start with some easy exercises for learning to play single notes on the guitar. Then the chapter moves on to things that actually sound cool and are fun to play.

Single-note technique

Using all downstrokes, play the music in Figure 2-1 (if you need a refresher on reading music, see Book 1 Chapter 4). These are six passages, each on separate strings that require you to play three different notes. All the melodies are in quarter notes, which means the notes come one per beat, or one per foot tap if you’re tapping along in tempo.

The trick here is to play single notes on individual strings accurately, without accidentally hitting the wrong string. You don’t have to play any fancy rhythms or down- and upstroke combinations, you just have to hit the desired string cleanly. Obviously, it’s harder to do that on the interior strings (2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th) than on exterior ones (1st, 6th).

FIGURE 2-1: Quarter-note melodies on each of the guitar’s six strings in open position.

FIGURE 2-2: A quarter-note melody played across different strings.

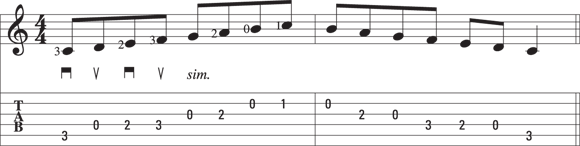

Alternate picking in downstrokes and upstrokes

Let’s double the pace, shall we, by introducing eighth notes into your playing. Keep in mind that in rhythm playing, you can often play eighth notes by just speeding up your downstroke picking. But in lead playing, you must always play eighth notes using the technique called alternate picking.

The alternate-picking technique doesn’t care whether you have to cross strings or not. In an eighth-note melody, the alternate-picking technique requires that the downbeat notes take downstrokes and the upbeat notes (the ones that fall in between the beats) take upstrokes.

Using scales

By definition, a scale proceeds in stepwise motion. Scales are the dreaded instruments of musical torture wielded by Dickensian disciplinarians (like your fourth-grade piano teacher), but they do serve a purpose. They are a great way to warm up your fingers within a recognizable structure and they reveal available notes on the fingerboard within a key.

Plus, playing scales provides a familiar-sounding melody (do re mi fa sol la ti do) that yields a certain satisfaction upon correct execution — at least until you’ve done them two or three billion times and you can’t stand it anymore.

But for now, try an ascending, contiguously sequenced set of natural notes in the key of C beginning on the root (the first degree of the scale or chord) — a C major scale.

Playing in the majors

FIGURE 2-3: A one-octave C major scale, ascending and descending.

Left-hand fingerings are also provided in the standard music notation staff. The idea is not that you sight read all this stuff — the notes, the right- and left-hand indications, and so forth — but that you learn this passage and play it whenever you feel like warming up, playing a C scale. Or you can just play the scale when inspiration waits in the wing space of your mind, mute and mocking, and you can’t think of anything else musically cohesive to play.

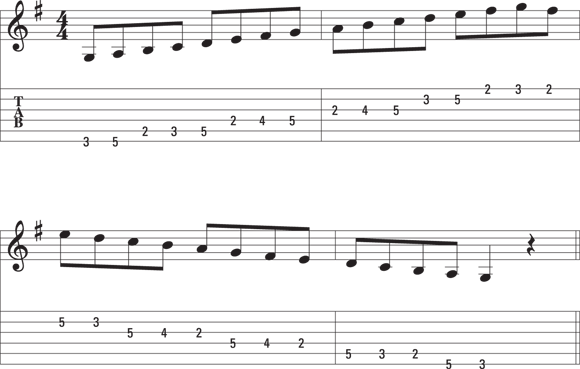

FIGURE 2-4: A two-octave G major scale, ascending and descending.

A minor adjustment

Every major scale has a corresponding minor scale, the relative minor, which you can play in its entirety using the same key signature. In any major key, the natural minor scale (so called because you can play it naturally, with no altering of the major-scale notes) begins at the 6th degree.

FIGURE 2-5: A one-octave A minor scale.

Skips

FIGURE 2-6: An Am7 arpeggio.

Combining steps and skips

Most melodies are composed of a mix of stepwise motion and skips, and sometimes melodies can include an arpeggio (such as in the army bugle calls “Taps” and “Reveille”). Scales are a series of notes organized by key, where you play the notes in order, ascending and/or descending. Arpeggios can be skips in any order, but are limited to the notes of the chord.

Starting at the Bottom: Low-Note Melodies

For some reason, all traditional guitar method books start with the guitar’s top strings and work their way down to the low strings. But in the true rebellious spirit of both rock and roll and the For Dummies series, this section starts at the bottom.

The impetus for so many of the world’s greatest melodies, riffs, and rock rhythm figures have low-born origins (from a guitar perspective, anyway). Think of all the classic riffs already mentioned in this chapter — “Smoke on the Water,” “Iron Man,” “Day Tripper” — and how many of them are low-note riffs.

FIGURE 2-7: A rocking low-note melody, exploiting the low strings of the guitar.

FIGURE 2-8: A low-note melody in moving eighth notes.

Going to the Top: High-Note Melodies

FIGURE 2-9: A high-note melody in open position.

Playing in Position

So far you’ve played all of your melodies and exercises in the lower regions of the neck, between the 1st and 4th frets. This is where it’s easiest to place the notes that you see written on paper onto frets of the guitar neck.

But the guitar has many more frets on the neck than just the first four. Playing in the lowest regions of the neck is where you play most of your low-note riffs, a lot of chords, and some lead work, but the bulk of your lead playing takes place in the upper regions of the neck for two reasons:

- The higher on the neck you are, the higher the notes you can hit. The guitar is sort of a low instrument, because the notes you read on the treble clef actually sound an octave lower on the guitar. For this reason, it’s a good idea to get as far up the neck as possible if you want to distinguish yourself melodically, above the low end rumble of basses, drums, and, of course, other guitars playing rhythm in the lower range.

- The strings are more flexible and easily manipulated by the left hand on the higher frets, which means you have better expressive opportunities for bends, vibrato, hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides and other expressive devices (all of which are covered in Book 4 Chapter 4).

Open position

Playing in open position is where you’ve spent your time thus far — by design. When you have complete command of the entire neck and you can play anywhere you can find the note, playing in open position will be a choice. In other words, you’ll play in open position only because you want to, because it suits your musical purpose.

Rock guitar uses both open position and the upper positions (the positions’ names are defined by where the left-hand index finger falls) for the different musical colorings they offer. By contrast, jazz guitar tends to avoid open position completely, and folk guitar uses open position exclusively. But rock uses both, and so you need to understand the strengths offered by both open position and the upper positions.

Moveable, or closed, position

Playing in a moveable position allows you to take a passage of music and play it anywhere on the neck. If you play a melody on all fretted strings, as in a barre chord (incorporating no open strings), it doesn’t matter if you play it at the 1st fret or the 15th. The notes will preserve the same melodic relationship. It’s sort of like swimming: After you learn the technique of keeping yourself afloat and moving, it doesn’t matter if the water is five feet or five miles deep — except five-mile deep water is probably colder.

A moveable position is also called closed position, because it involves no open strings. After you play anything on all-fretted strings, you have created a great opportunity to slide it anywhere on the neck and have it play exactly the same — except of course that you’re apt to find yourself in another key. (Book 2 Chapter 3 has more on open, movable, and barre chords.)

The best part is that you can move closed-position melodies around — instantly transposing their key, something that no piano player, trumpet player, or flute player can do easily, and they will be eternally jealous of you.

FIGURE 2-10: A two-octave G major scale in 2nd position.

Try sliding your hand up and down the neck, playing the scale in different positions. Doing so will transpose your G major scale into other keys.

Jamming on Lower Register Riffs

The best thing about the lower register of the guitar is its powerful bass notes. You simply have no better arsenal for grinding out earth-shattering, filling-rattling, brain-splattering tones than the lower register of the guitar, and so this is where 99 percent of all the greatest riffs are written.

FIGURE 2-11: A classic walking-bass boogie-woogie riff in G.

Making It Easy: The Pentatonic Scale

The major and minor scales may be music-education stalwarts, but as melodic material they sound, well, academic when used over chord progressions. Rock guitarists have a much better scale to supply them with melodic fodder: the pentatonic scale.

As its name implies, the pentatonic scale contains five notes, which is two notes shy of the normal seven-note major and minor scales. This creates a more open and less linear sound than either the major or minor scale. The pentatonic scale is also more ambiguous, but this is a good thing, because it means that it’s harder to play “bad” notes — notes that, although they’re within the key, may not fit well against any given chord in the progression. The pentatonic scale uses just the most universal note choices.

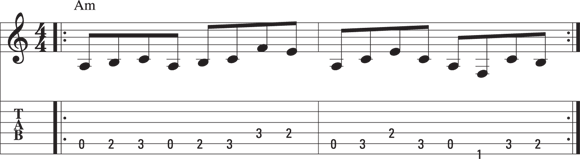

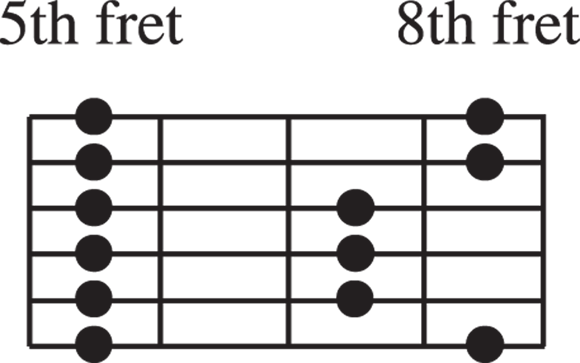

The first scale you’ll learn here is the A minor pentatonic. A minor pentatonic can be used as a lead scale over chord progressions in A minor, C major, and A blues (“blues” can imply a specific, six-note scale, as well as a chord progression). It also works pretty well over A major and C blues. Not bad for a scale that’s two notes shy of a major scale.

FIGURE 2-12: A neck diagram showing the pentatonic scale in 5th position.

Playing the Pentatonic Scale: Three Ways to Solo

In this section you learn to play one pentatonic scale pattern in three different musical contexts:

- A progression in a major key

- A progression in a minor key

- A blues progression

You can use just one pattern to satisfy all three musical settings. This is an unbelievable stroke of luck for beginning guitarists, and you can apply a shortcut, a quick mental calculation, that allows you to instantly wail away in a major-key song, a minor-key song, or a blues song — simply by performing what is essentially a musical parlor trick. This is a great quick-fix solution to get you playing decent-sounding music virtually instantly.

As you get more into the music, however, you may want to know why these notes are working the way they do. But until then, it’s just time to jam.

Place your index finger on the 5th fret, 1st string. Relax your hand so that your other fingers naturally drape over the neck, hovering above the 6th, 7th, and 8th frets. You are now in 5th position ready to play.

Work to play each note singly, from top to bottom, so that you get your fingers used to playing the frets and switching strings. Don’t worry about playing downstrokes and upstrokes until you’re comfortable moving your left-hand fingers up and down the strings, like a spider walking across her web.

FIGURE 2-13: A descending eighth-note C pentatonic major scale.

This particular pentatonic pattern allows you to keep your left hand stationary; all the fingers can reach their respective fret easily without stretching or requiring left-hand movement.

Now that you’ve played the scale, try it in a musical context. This is where you witness the magic that transpires when you play the same notes over different feels in different keys. Let the games begin!

Pentatonics over a major key

Pentatonics over a minor key

FIGURE 2-14: Solo in C major over a medium-tempo 4/4.

FIGURE 2-15: An A minor solo over a heavy backbeat 4/4.

Pentatonics over a blues progression

In the next section, you don’t have to master any music at all. You get to make up your own.

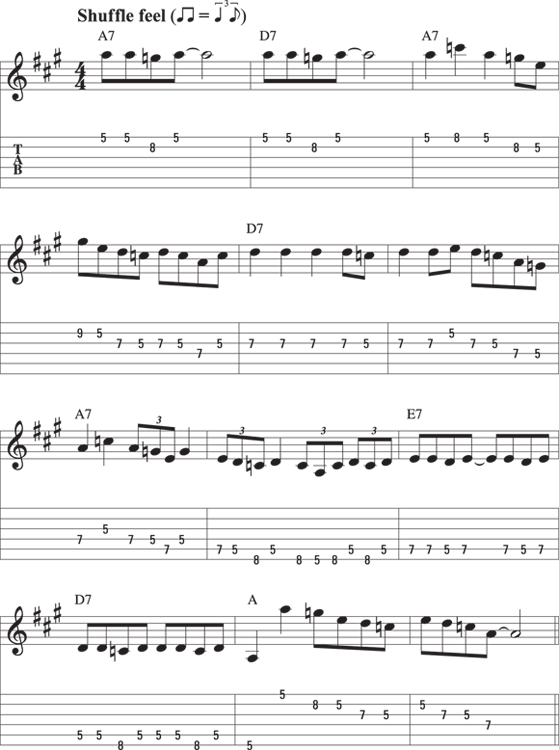

FIGURE 2-16: An A blues solo over an up-tempo shuffle.

Improvising Leads

In rock, jazz, and blues, improvisation plays a great role. In fact, being a good improviser is much more important than being a good technician. It’s much more important to create honest, credible, and inspired music through improvisation than it is to play with technical accuracy and perfection.

The best musicians in the world are the best improvisers, but they are not necessarily the best practitioners of the instrument. About the only thing that competes with the ability to improvise a good solo is the ability to write a song.

FIGURE 2-17: A slow blues shuffle in A.

Improvising is, at the same time, one of the easiest things to do (just find your notes and go) and one of the hardest (try to make up a meaningful melody on the spot). The more note choices you have, the more vocabulary you’ll be able to pull from to express your message.

The pentatonic scale is a great way to start making music immediately, but plenty of other scales exist to help you in your music making. And you still have to listen to other guitarists for ideas. Go outside any scale you use to get unusual notes, and learn passages of classic solos on recordings to see what makes them tick. Above all, you must develop you own sense of phrasing and your own voice.

Strictly speaking, lead playing is the featured guitar, which is usually playing a single-note-based line. But it doesn’t always have to be playing only single notes; it could be playing double-stops, which are two notes played together. Also, the designation lead guitar helps to distinguish that guitar from the other guitar(s) in the band playing rhythm guitar.

Strictly speaking, lead playing is the featured guitar, which is usually playing a single-note-based line. But it doesn’t always have to be playing only single notes; it could be playing double-stops, which are two notes played together. Also, the designation lead guitar helps to distinguish that guitar from the other guitar(s) in the band playing rhythm guitar. Try playing the music by yourself (without listening to Track 51, starting at 00:00), counting (and tapping) out a bar of tempo before you begin to play. After you think you’ve mastered the exercise and can play it without stopping or making a mistake, try playing it along with Track 51.

Try playing the music by yourself (without listening to Track 51, starting at 00:00), counting (and tapping) out a bar of tempo before you begin to play. After you think you’ve mastered the exercise and can play it without stopping or making a mistake, try playing it along with Track 51. Each exercise is written in a different feel (as evidenced by the recording on Track 51), but don’t let that throw you. As long as you count out the quarter notes with the count-off on the audio track (heard as the percussive click of the struck hi-hat cymbals, as a drummer would do when counting off a song) and focus on playing smooth, one-note-per-foot-tap notes, you should do fine.

Each exercise is written in a different feel (as evidenced by the recording on Track 51), but don’t let that throw you. As long as you count out the quarter notes with the count-off on the audio track (heard as the percussive click of the struck hi-hat cymbals, as a drummer would do when counting off a song) and focus on playing smooth, one-note-per-foot-tap notes, you should do fine. As a guitarist, you not only have to focus on keeping the rhythm steady between bars, but also when switching strings.

As a guitarist, you not only have to focus on keeping the rhythm steady between bars, but also when switching strings.