Chapter 4

Right-Hand Rhythm Guitar Techniques

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Strumming with your right hand

Strumming with your right hand

![]() Using your palm to mute and accent

Using your palm to mute and accent

![]() Exploring different rhythm feels

Exploring different rhythm feels

![]() Access the audio tracks at

Access the audio tracks at www.dummies.com/go/guitaraio/

The right hand marshals the chords and notes you form in the left hand into the syncronized sounds you actually hear. The right hand is the engine that drives rhythm guitar, which weaves together the bass and drums and provides the underpinning for the singer, lead guitar, or other melodic instruments.

Whether it’s playing in a steady eighth-note groove, a funky 16 feel, or a hard-swinging shuffle, the rhythm guitar and the right-hand strumming that propels it forge the chords and riffs you learn into a moving musical experience.

This chapter shows you different ways you can strum the guitar to make the rhythm fit a bunch of different styles and feels. These variations help keep your music vital-sounding, and help you to develop your skills as a rhythm guitarist — one who provides the backing and the foundation to support the melody, and who can act as the glue between the other rhythm instruments such as the bass and drums.

Strumming Along

Strumming is defined as dragging a pick (or the fingers) across the strings of the guitar. In doing that, you create rhythm.

FIGURE 4-1: Playing an E chord in one bar of four quarter notes.

After you learn to play consistently, you can then deviate from the established pattern you lay down and work on your own variations, as long as they’re tasteful, appropriate, and not too numerous. Like a rock and roll rebel once said, “You have to know the rules before you can break them.”

Downstrokes

A downstroke (indicated by the symbol ![]() ) is the motion of dragging the pick toward the floor in a downward motion, brushing across multiple strings on the guitar in the process. Because you execute a downstroke quickly (even on slow songs) the separate strings are sounded virtually simultaneously. Playing three or more notes this way produces a chord.

) is the motion of dragging the pick toward the floor in a downward motion, brushing across multiple strings on the guitar in the process. Because you execute a downstroke quickly (even on slow songs) the separate strings are sounded virtually simultaneously. Playing three or more notes this way produces a chord.

Strumming in eighth-note downstrokes

To get out of the somewhat plodding rhythm of a quarter-note-only strumming pattern, you turn to eighth notes. As the math implies, an eighth note is one half the value of a quarter note, but in musical terms that equates to twice as fast, or more precisely, twice as frequently.

So instead of playing one strum per beat, you now play two strums per beat. This means you must move your hand twice as fast, striking the strings two times per beat, instead of once per beat as you did to produce quarter notes. At moderate and slower tempos, you can do this easily. For faster tempos you use alternating upstrokes and downstrokes (explained later in this chapter). For playing the progression in Figure 4-1, however, simply using repeated downstrokes is easiest.

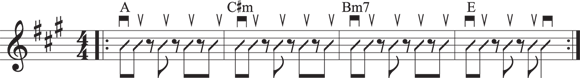

FIGURE 4-2: An eighth-note progression using right-hand downstrokes.

Reading eighth-note notation

Notice that instead of the previously used slashes, you now have slashes with stems (the vertical lines coming down from the note head) and beams (the thicker horizontal lines that connect the stems). Quarter notes have single stems attached to them; eighth notes have stems with beams connecting them to each other. An eighth note by itself, or separated by a rest, will have a flag instead of a beam: ![]() .

.

Upstrokes

An upstroke (indicated by the symbol ![]() ) is just what it sounds like: the opposite of a downstroke. Instead of dragging your pick down toward the floor, you start from a position below the strings and drag your pick upward across them. Doing this comfortably may seem a little less natural than playing a downstroke. One reason for this is that you’re going against gravity. Also, some beginners have a hard time holding on to their pick or preventing it from getting stuck in the strings. With practice, however, you can flow with the ups as easily as you can with the downs.

) is just what it sounds like: the opposite of a downstroke. Instead of dragging your pick down toward the floor, you start from a position below the strings and drag your pick upward across them. Doing this comfortably may seem a little less natural than playing a downstroke. One reason for this is that you’re going against gravity. Also, some beginners have a hard time holding on to their pick or preventing it from getting stuck in the strings. With practice, however, you can flow with the ups as easily as you can with the downs.

Upstrokes don’t get equal time with their downwardly mobile counterparts. You typically use upstrokes only in conjunction with downstrokes. Whereas you can use downstrokes by themselves just fine — for entire songs, even — very rarely do you use upstrokes in isolation or without surrounding them on either side with downstrokes. (Some situations, such as the “Reggae rhythm” shown in Figure 4-21, do call for just upstrokes.)

So you should first tackle upstrokes in their most natural habitat: in an eighth-note rhythm figure where they provide the in-between notes, or offbeats, to the on-the-beat downstrokes.

Combining downstrokes and upstrokes

At this easygoing tempo, you can probably play Figure 4-3 with all downstrokes. If you try that, however, you discover that it introduces a tenser, more-frantic motion in your own strumming motion, which is not in character with the song’s mellow feel. Frantic motion can be a very good thing in rock, though. (Figure 4-14, for example, shows you how an all-downstroke approach on a faster song is more appropriate than the easy back and forth of alternating downstrokes and upstrokes.)

FIGURE 4-3: An easy 4/4 strum in eighth notes using downstrokes and upstrokes.

Playing a combination figure

FIGURE 4-4: Strumming in quarter and eighth notes for different intensity levels.

Strumming in sixteenths

Sixteenth notes come twice as fast as eighth notes, or four to the beat. That can seem pretty twitchy, so sixteenth notes are almost always played with alternating downstrokes and upstrokes. Some punk and metal bands play fast sixteenth-note-based songs with all downstrokes, but their songs are usually about pain and masochism, so it’s understandable, given the circumstances. The acoustic guitar part in the Who’s “Pinball Wizard” is a classic example of sixteenth-note strumming.

FIGURE 4-5: A medium-tempo progression using sixteenth notes.

If the rhythmic notation seems like it’s getting a little dense, don’t worry too much about understanding the notation thoroughly or being able to play it at sight. What’s important is to learn the figure, memorize it, and play it correctly and with confidence. Listening to Track 19 repeatedly to learn this figure is okay, too.

Reading sixteenth-note notation

Sixteenth notes are indicated with two beams connecting their stems (or if they’re by themselves, two flags (![]() ).

).

Getting a shuffle feel

An important rhythm feel used extensively in rock is the shuffle. A shuffle is a lilting eighth-note sound where the beat is divided into two unbalanced halves, a long note followed by a short. Think of the riffs to such songs as Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog,” the Beach Boys’ “California Girls,” Fleetwood Mac’s “Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow,” and the Grateful Dead’s “Truckin’.” These are all based on a shuffle feel.

Rather than thinking about it too much, try this simple exercise, which can help you hear the difference between straight eighth notes (equally spaced) and triplet eighth notes (the first held twice as long as the second):

Tap your foot in a steady beat and say the following line, matching the bold syllables to your foot taps:

Twink-le twink-le lit-tle star.

That’s the sound of normal, equally spaced, straight eighth notes.

Now in the same tempo (that is, keeping your foot tap constant), try saying this line, based in triplets:

Fol-low the yel-low brick road.

That’s the sound of triplets. In both cases you should keep your foot tap at exactly the same tempo and change only how you subdivide the beat.

Create shuffle eighth notes by sounding only the first and third notes of the triplet.

Do this by sustaining the first note through the second or by leaving out that second note entirely. The new sound is a limping, uneven division that goes l-o-n-g-short, l-o-n-g-short, and so forth.

A good way to remember the sound of triplet eighth notes (the basis of a shuffle feel) is the song “When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again.” If you tap your foot or snap your fingers on the beat and then try saying the lyrics in rhythm, you get:

When John-ny comes march-ing home a-gain, hur-rah

The bold type represents the beat, where the syllables coincide with your foot tap or finger snap. The phrase “Johnny comes” is in triplets, because each syllable falls on one note of the three in between two beats. The rest of the phrase, “marching home again, hurrah,” divides each beat into two-syllable pairs, the first syllable longer than the second. This is the sound of eighth notes in a shuffle feel.

FIGURE 4-6: Eighth-note shuffle in G. Play the three new chord forms by moving one finger from the chord it’s derived from.

Actually, the chords aren’t so much new as they are a one-finger variation of chords you already play. These “new” chords are easily executed by moving one and only one finger, while keeping the others anchored. It’s the first step to getting both hands moving on the guitar, a really exciting accomplishment that makes you feel like a real guitar player. Have fun with this one!

The upstrokes still come at the in-between points — within the beats — but because of the unequal rhythm, it may take you a little time to adjust.

Mixing Single Notes and Strums

Rhythm guitar includes many more approaches than just simultaneously strumming chords. A piano player doesn’t plunk down all her fingers at once every time she plays an accompaniment part, and guitarists shouldn’t have to strike all the strings every time they bring their pick down.

In fact, guitarists borrow a technique from their keyboard-plunking counterparts, who separate the left and right hands to play bass notes and chords, respectively. When guitarists separate out the components of a chord, they don’t use separate hands, but combine both aspects in their right hand. Playing bass notes with chords is called a pick-strum pattern.

The pick-strum

Separating the bass and treble so that they play independently in time is a great way to provide rhythmic variety and introduce different chordal textures. Guitarists can even set up an interplay of the different parts — a bass and treble complementarity or counterpoint.

Boom-chick

The simplest accompaniment pattern is known by the way it sounds: boom-chick. The boom-chick pattern is very efficient because you don’t have to play all the notes of the chord at once. Typically you play the bass note on the boom, and the all the notes in the chord except the bass note on the chick — but you get sonic credit for playing twice.

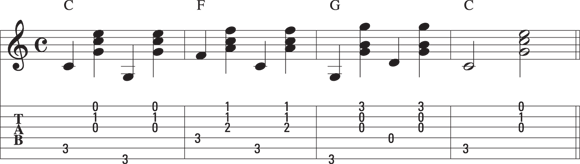

FIGURE 4-7: A bass-chord pattern in a typical country-rock groove.

FIGURE 4-8: The bass-note-and-chord treatment makes things more varied and interesting.

Moving bass line

Another device available to you after you separate the bass from the chord is the moving bass line. Examples of songs with moving bass lines include Neil Young’s “Southern Man,” Led Zeppelin’s “Babe, I’m Gonna Leave You,” the Grateful Dead’s “Friend of the Devil,” and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s “Mr. Bojangles.” A moving bass line can employ the boom-chick pattern.

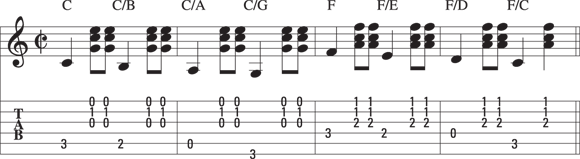

FIGURE 4-9: A moving bass line over a chord progression.

Disrupting Your Sound: Syncopated Strumming

After you develop a feel for strumming in different combinations of quarters, eighths, and sixteenths, you can increase the rhythmic variation to these various groupings by applying syncopation. Syncopation is the disruption or alteration of the expected sounding of notes. In rock and roll right-hand rhythm playing, you do that by staggering your strum and mixing up your up- and downstrokes to strike different parts of the beats. By doing so, you let the vehicles of syncopation — dots and ties — steer your rhythmic strumming to a more driving and interesting course.

Syncopated notation: Dots and ties

A dot attached to a note increases its rhythmic value by half its original value. For example, a dot attached to a half note (two beats) makes it three beats long. A dotted quarter note is one and a half beats long, or, a quarter note plus an eighth note. A tie is a curved line that connects two notes of the same pitch. The value of the note is the combined values of the two notes together, and only the first note is sounded.

Figure 4-10 shows some common syncopation figures employing dots and ties. The top part of the table deals with dots and shows note values, their new value with a dot and the equivalent expressed in ties, and a typical figure using a dot with that note value. The bottom part of the figure deals with ties and shows note values, their new value when tied to another note, and a typical figure using a tie with that note value.

FIGURE 4-10: Common syncopation features.

Playing syncopated figures

So much for the music theory behind syncopation. How do you actually play syncopated figures? Try jumping in and playing two progressions, one using eighth notes and one using sixteenth notes, that employ common syncopation patterns found in rock.

FIGURE 4-11: A common rock figure using eighth-note syncopation.

FIGURE 4-12: A common rock figure using eighth- and sixteenth-note syncopation.

Giving Your Left Hand a Break

If you listen closely to rhythm guitar in rock songs, you’ll hear that strummed figures are not one wall of sound — that minute breaks occur in between the strums. These breaks prevent the chord strums from running into each other and creating sonic mush. The little gaps in sound keep a strumming figure sounding crisp and controlled.

To form these breaks, or slight sonic pauses, you need to stop the strings from ringing momentarily. Talking very small moments here — much smaller than those pauses on a greeting card commercial when the daughter realizes she’s just like her mother as they sip cocoa and look out the window. Controlling the right hand’s gas pedal with the left hand’s brake pedal is a useful technique for cutting off the ring-out of the strings.

Left-hand muting

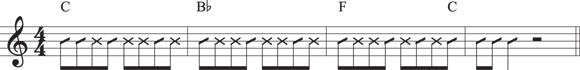

To get the left-hand to mute the in-between sound between any two chords, just relax the fretting fingers enough to release pressure on the fretted strings. These strings will instantly deaden, or muffle, cutting off sound. What’s more, if you keep your right-hand going along in the same strumming pattern, you produce a satisfying thunk sound as the right hand hits all these deadened strings. This percussive element, intermixed among the ringing notes creates an ideal rock rhythm sound: part percussive, part syncopated, and all driving. If you relax the left hand even further so that it goes limp across all six strings, then no strings will sound, not just the ones the left hand fingers cover. Also, allowing your left-hand to do the muting means you can keep your right hand going, uninterrupted, in alternating down- and upstrokes. The notation indicates a left-hand mute with an X note head.

Implying syncopation

FIGURE 4-13: A strum employing left-hand muting to simulate syncopation.

Left-hand muting is one of those rhythm techniques that guitarists just seem to develop naturally, so obvious and useful is its benefit. And like riding a bicycle, left-hand muting is more difficult to execute slowly. So don’t analyze it too much as you’re learning; just strum and mute in the context of a medium-tempo groove. Your hands will magically sync up, and you won’t even have to think about it.

Suppressing the Right Hand

You can also mute with your right hand (using the heel of the palm), but this produces a different effect than left-hand muting. In right-hand muting, you still hear the sound of the fretted string, but in a subdued way. You don’t use right-hand muting to stop the sound completely, as you do in a left-hand mute; you just want to suppress the string from ringing freely. Like left-hand muting, right-hand muting keeps your tone from experiencing runaway ring-out, but additionally it provides an almost murky, smoldering sound to the notes, which can be quite useful for dramatic effect. You sometimes hear this technique referred to as chugging.

Right-hand muting

You perform a right-hand mute by anchoring the heel of your right hand on the strings just above the bridge. Don’t place your hand too far forward or you’ll completely deaden the strings. Do it just enough so that the strings are dampened (damping is a musical term which means to externally stop a string from ringing) slightly, but still ring through. Keep it there through the duration of the strum.

FIGURE 4-14: A rhythm figure with palm mutes and accents.

Left-hand Movement within a Right-hand Strum

When you begin to move the left-hand in conjunction with the right, you uncover an exciting new dimension in rhythm guitar: left-hand movement simultaneous with right-hand rhythm. This “liberating of the left hand” is also the first step in playing single-note riffs and leads on the guitar (see Book 4 Chapter 4 for more on the glories of lead guitar).

Figure 4-15 (Track 28) features a classic left-hand figure that fits either a straight-eighth-note groove or a shuffle feel (although it’s placed here in a straight-eighth setting). The changing notes in this example are the 5th degrees of each chord, which move briefly to the 6th degree. So in an A chord, the E moves to F♯; in a D chord the A moves to B; and in an E chord the B moves to C♯. You can find this “5-6 move” in songs by Chuck Berry, the Beatles, ZZ Top, and plenty of blues-rock tunes. The 5-6 move fits over any I-IV-V progression. In Figure 4-14 it’s in the key of A.

FIGURE 4-15: An eighth-note 5-6 progression using all downstrokes and a moving left hand.

Note that to more easily accommodate the 5-6 move, alternate chords and fingering are supplied to satisfy the A, D, and E chords. In each case the chords use only three strings, all adjacent to each other.

And even though it’s in steady eighth notes, this progression should be played using all right-hand downstrokes. If you can throw in some palm muting (as is done on Track 28), so much the better!

Giving Your Fingers Some Style

Although more than 99 percent of all rock playing is played with a pick, occasions for fingerstyle do pop up from time to time. Fingerstyle, as the name implies, means that you pluck the strings with the right-hand fingertips. For these times you can put the pick down, stick it between your teeth, or tuck it in your palm, whichever allows you to grab it the fastest after the fingerstyle passage is over.

Fingerstyle is especially suited to playing arpeggios, or chords played one note at a time in a given pattern. Fingerstyle is a much easier way to play different strings in rapid succession, as you must do for arpeggiated passages. Generally speaking, the thumb plays the bass strings and the fingers play the upper three strings. Think of the opening figure to Kansas’s “Dust in the Wind,” Fleetwood Mac’s “Landslide,” or Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer,” and imagine trying to play those patterns with your pick hopping frantically around the strings.

Position your right hand just above the strings, so your fingers can dangle freely but in reach of the individual strings. In Figure 4-16, the thumb plays the downstem notes and the right-hand fingers play the upper notes. (For you classical guitar aficionados out there: The standard way to notate the right-hand fingers is with the letters p, i, m, and a, for the Spanish words for the thumb, index, middle and ring fingers — see the chapters in Book 6 for much more on classical guitar.)

Of course, you don’t have to play an arpeggiated passage fingerstyle, if it’s slow and there’s relatively little string skipping involved. But for longer passages, or if the tempo is fairly rapid and the string skipping is relentless, work out the passage as a fingerstyle exercise.

FIGURE 4-16: Fingerstyle arpeggios played with the right-hand thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers.

Getting Into Rhythm Styles

To close out this chapter and your study of the right-hand rhythm styles, this section tackles some song-length exercises that illustrate many of the characteristics, both chordal and rhythmic, of standard grooves or feels in rock music.

Rhythm section players often talk to each other in terms of feel, and standard terms have developed to describe some of the more common rhythmic accompaniment styles. Table 4-1 provides a list of different feels by their popular name, what time signature they’re in, what their characteristics are, and some classic tunes that illustrate that feel.

TABLE 4-1 Classic Songs in a Variety of Grooves

Name |

Time Signature |

Characteristic |

Tunes |

|---|---|---|---|

Straight-four |

4/4 |

Easy, laid-back feel |

Tom Petty: “Won’t Back Down,” Eagles: “New Kid in Town,” The Beatles: “Hard Day’s Night” |

Heavy back-beat |

4/4 |

Like straight-four, but with a heavier back-beat (accent on beats 2 and 4) |

Bachman Turner Overdrive: “Taking Care of Business,” Bob Seger: “Old Time Rock and Roll,” Spencer Davis/Blues Brothers: “Gimme Some Lovin’” |

Two-beat |

|

jumping boom-chick |

Creedence Clearwater Revival: “Bad Moon Rising,” The Beatles: “I Feel Fine,” Pure Prairie League: “Amie” |

16-feel |

4/4 |

Funky or busy accompaniment |

James Brown: “I Feel Good,” Sam and Dave/Blues Brothers: “Soul Man,” Aerosmith: “Walk This Way” |

Metal gallop |

4/4 |

Driving sixteenth-note sound like a horse’s gallop |

Metallica: “Blackened,” Led Zeppelin: “The Immigrant Song” |

Shuffle |

4/4 |

Limping lilting eighth notes; swing feel |

Fleetwod Mac: “Don’t Stop,” ZZ Top: “La Grange” and “Tush,” The Beatles: “Can’t Buy Me Love” and “Revolution” |

Three-feel |

3/4, 6/8, 12/8 |

Meter felt in groups of three |

The Eagles: “Take It to the Limit,” The Beatles: “Norwegian Wood” (6/8) and “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” (6/8) |

Reggae/ska |

4/4 |

Laid-back with syncopation |

Eric Clapton: “I Shot the Sheriff,” Bob Marley: “No Woman, No Cry,” Johnny Nash: “Stir It Up” |

Straight-four feel

FIGURE 4-17: A straight-ahead 4/4 groove in the style of The Eagles.

Two-beat feel

FIGURE 4-18: A two-beat country groove with bass runs.

16-feel

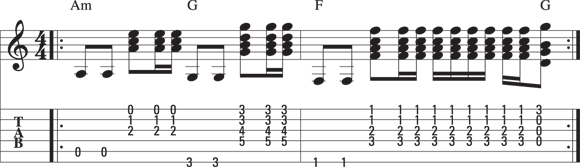

FIGURE 4-19: A medium tempo funky groove in a 16-feel.

Heavy metal gallop

FIGURE 4-20: A heavy metal gallop using eighths and sixteenths.

Reggae rhythm

Reggae is a wonderfully laid-back rhythm style that features sparse chordal jabs from the guitar delivered on the offbeat. Reggae can exist either in a straight-eighth or shuffle feel. In Figure 4-21 (Track 34) it’s in a medium-slow shuffle. Pay particular attention to the upstroke indications — several of them occur in a row, resulting from the successive offbeat strums.

FIGURE 4-21: A typical Reggae backup pattern highlighting the offbeats.

Three feel

A song in a three feel is pretty easy to spot — it’s counted in groups of three (not the usual two and four), and you can do the waltz to it. If you played hooky from ballroom dancing lessons as a kid and don’t know how to waltz, you can usually hear a strong beat one, followed by the weaker beats two and three. The Eagles’ “Take It to the Limit” is in 3/4, and the Beatles’ “Norwegian Wood” is in 6/8. Technically, a song in 6/8 is felt in two, because it’s separated into two halves each receiving three eighth notes. But in the unfussy world of rock rhythm, anytime a guitarist has to strum in three — whether it’s in 3/4 or whether it’s in 6/8 or 12/8 (as in some doo-wop-type songs) — he just calls it a “three feel.” So “Norwegian Wood” and “House of the Rising Sun,” which are in 6/8, and “You Really Got a Hold on Me” and “Nights in White Satin,” which are in 12/8, can be described as “three feel” songs. Strum in groups of three or go boom-chick-chick, depending on the tempo (it’s sometimes easier on faster tempos to go boom-chick-chick).

FIGURE 4-22: A song in 3/4, featuring a moving bass line.

If you “pick-drag” in regular, even strokes, one per beat, adhering to a tempo (musical rate), you’re strumming the guitar in rhythm. And that’s music, whether you mean it to be or not. More specifically, you’re strumming a quarter-note rhythm, which is fine for songs such as the Beatles’ “Let It Be” and other ballads. For the record, strumming an E chord in quarter notes looks like the notation in

If you “pick-drag” in regular, even strokes, one per beat, adhering to a tempo (musical rate), you’re strumming the guitar in rhythm. And that’s music, whether you mean it to be or not. More specifically, you’re strumming a quarter-note rhythm, which is fine for songs such as the Beatles’ “Let It Be” and other ballads. For the record, strumming an E chord in quarter notes looks like the notation in  The hardest part of learning rhythm guitar is realizing — and then maintaining — all the repetition involved. It’s not what people expect when they pick up the guitar and want to learn a smorgasbord of cool licks and great riffs. But being able to play in time with unerring precision and rock-steady consistency is an essential skill and a hallmark of solid musicianship. Most rhythm playing in rock guitar involves a one- or two-bar pattern that gets repeated over and over, varying only where there are accent points that the band plays in unison.

The hardest part of learning rhythm guitar is realizing — and then maintaining — all the repetition involved. It’s not what people expect when they pick up the guitar and want to learn a smorgasbord of cool licks and great riffs. But being able to play in time with unerring precision and rock-steady consistency is an essential skill and a hallmark of solid musicianship. Most rhythm playing in rock guitar involves a one- or two-bar pattern that gets repeated over and over, varying only where there are accent points that the band plays in unison. The term sim. in the music notation tells you to continue in a similar fashion. It’s typically used for articulation directions, such as down- and upstrokes.

The term sim. in the music notation tells you to continue in a similar fashion. It’s typically used for articulation directions, such as down- and upstrokes. You use upstrokes for the upbeats (offbeats) in eighth-note playing as the strokes in between the quarter-note beats. And when you start playing, don’t worry about hitting all the strings in an upstroke. For example, when playing an E chord with an upstroke, you needn’t strum the strings all the way through to the sixth string. Generally, in an upstroke, hitting just the top three or four strings is good enough. You may notice that your right hand naturally arcs away from the strings by that point, to an area above the center of the guitar. This is fine.

You use upstrokes for the upbeats (offbeats) in eighth-note playing as the strokes in between the quarter-note beats. And when you start playing, don’t worry about hitting all the strings in an upstroke. For example, when playing an E chord with an upstroke, you needn’t strum the strings all the way through to the sixth string. Generally, in an upstroke, hitting just the top three or four strings is good enough. You may notice that your right hand naturally arcs away from the strings by that point, to an area above the center of the guitar. This is fine.