Chapter 4

Going Up the Neck and Playing the Fancy Stuff

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Playing up the neck and playing in position

Playing up the neck and playing in position

![]() Playing the movable pentatonic scale

Playing the movable pentatonic scale

![]() Playing hammer-ons and pull-offs

Playing hammer-ons and pull-offs

![]() Getting expressive with slides, bends, and vibrato

Getting expressive with slides, bends, and vibrato

![]() Access the audio tracks at

Access the audio tracks at www.dummies.com/go/guitaraio/

To sound like a true rock and roller and to share the stratospheric heights frequented by the legions of wailing guitar heroes, you must learn to play up the neck. Actually, you need to learn how to think up the neck.

Playing up the neck requires both a theoretical approach and a technical adjustment. In fact, it’s probably a little harder on the brain (at least at first) to figure out what to play than it is for the fingers to fall in line. Those smart-alecky digits, which acclimate very quickly, just prove the old saying, “the flesh is willing but the spirit is weak.” Or something like that.

Rock players play up the neck a lot — a whole lot. Many rock players play way, way up the neck, higher than any folk-based music would dare venture, and beyond the usual range of many jazz players. In many folk-based and singer-songwriter-type songs, you often don’t have to play beyond open position at all. In rock, though, playing up the neck is essential, especially for lead playing. Playing up the neck also allows you to play the same notes many different ways. Barre chords also allow you to use chords of the same name but which appear in different parts of the neck. To suddenly glimpse what it’s like to have a command of the entire fretboard is a very exciting and empowering feeling.

Playing the guitar expressively — with passion, feeling, and an individual voice — is how you evolve from merely executing the correct pitches and rhythms to actually playing with style. In rock guitar playing, the technical approach to expressive playing involves varied approaches to articulation, or the way in which you sound the notes. Hammer-ons, pull-offs, slides, and bends are all different articulations to connect notes together smoothly.

In addition to attacking, or sounding, the notes, you can add expression to already-sounded notes with vibrato, which adds life to sustained notes that would otherwise just sit there like a head of brown lettuce. You can also apply muting, where you shape the envelope (the beginning, middle and end) of individual notes, giving them a tight, clipped sound.

Applying varied articulations is how you play and connect notes on the guitar. It’s what gives music a sense of continuity and coherence. If you master articulations and can weave them seamlessly into an integrated playing style, you can convince your guitar to do almost anything: talk, sing, cry, and even write bad checks.

Going Up the Neck

You are now leaving the relatively safe haven of open position for the great unknown — that vast uncharted sea of wire and wood they call (cue dramatic music) … the upper frets! It’s time to unbolt those training wheels, cut the apron strings, loose the surly bonds of earthbound music, and fly high. You’re going up the neck into the wild blue yonder.

Playing up the neck opens up a whole new world of possibilities for playing rock guitar music. If you know only one way to play an A chord — or to play a riff one way when you hear an A chord — then all your music will have a certain sameness about it. But if you have the entire neck at your disposal, can play A chords in several different places, can form lead lines in four or five places, and have opinions and associations on what effect you’ll produce when you choose one over the other — then you’re tapping the true potential of the possibilities the guitar neck has to offer.

Choking up on the neck

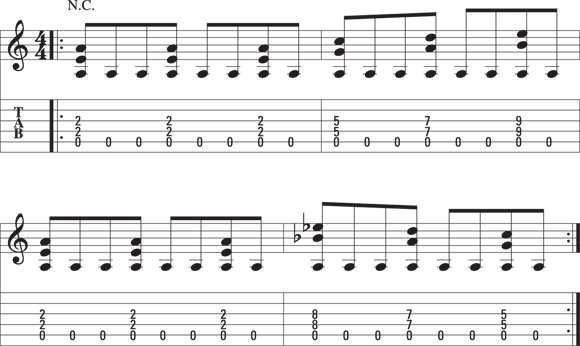

Let’s start with some known chord forms that you can move up and down to good musical effect over an open-D-string pedal (see the explanation of pedal in Book 4 Chapter 3).

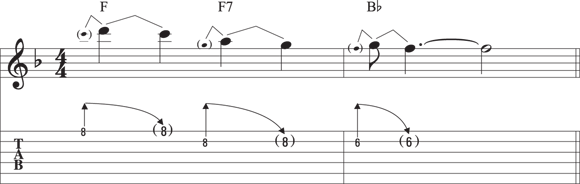

FIGURE 4-1: Open-position chord forms played up and down the neck.

Playing double-stops on the move

Because Figure 4-2 creates an interplay between the open A string and the moving double-stops, try increasing that sense of delineation by applying palm mutes (stopping the ringing of the strings with your right hand) to the open A string and accents to the fretted double-stop notes. You can hear this effect on the audio track.

After you’ve gotten a feel for what it’s like to move around the neck, you can see that not only won’t you get hurt, but also it’s kind of cool to do. The next section shows some movable lead patterns that will get you sounding and thinking like a pro in no time.

FIGURE 4-2: Moving double-stops over an A pedal.

Playing in Position

Guitarists don’t just go up the neck because it’s higher up there (although that’s sometimes a desired result — to produce higher-pitched notes), they do so because a certain position gives them better access to the notes or figures they want to play. Going to a certain zone on the neck, to better facilitate playing in a given key, is called playing in position. Book 2 Chapter 5 also discusses playing in position.

Positions defined

A position is defined as the lowest-numbered fret the left-hand index finger plays in a given passage. So to play in 5th position, place your left hand so that the index finger can comfortably fret the 5th fret on any string. If your hand is relaxed and the ball-side of the ridge of knuckles on your left-hand palm is resting near the neck, parallel to it, your remaining fingers — the middle, ring, and little — should be able to fret comfortably the 6th, 7th, and 8th frets, respectively. Figure 4-3 shows a neck diagram outlining the available notes of the C major pentatonic scale in 5th position.

FIGURE 4-3: The available frets in 5th position.

A firm position

The next question is what specific benefits playing in position brings — other than allowing you access to higher-pitched notes not available in open position? The answer is that certain positions favor certain keys, scales, figures, or styles, better than other positions do. Following are the three most common criteria for determining the best position in which to play a given passage of music:

Key and pitch class: The chief way to determine which position to play a certain piece of music in is by its key. To use the example in Figures 4-3 and 4-4, 5th position favors the major keys of C and F. If you have melodic material in the key of C or F, you’d be well advised to first try playing it in 5th position. Chances are, you’d find the notes fall easily and naturally under your fingers. Their relative minors A minor and D minor also fall very comfortably in 5th position. This is no accident, because these minor keys share the same key signature, which means they use exactly the same pitch class (a term you learn in music school for collection of notes, not necessarily in any given order) as their major-key counterparts.

The pitch class of the C major and A minor pentatonic scale is A C D E G. The order of the notes changes depending on the context. For example, in the key of C, where the root is C, the notes read C D E G A. In A minor, A is the root, so the notes are ordered as A C D E G. After you start to play, however, the order becomes unimportant.

- From a scale: A scale can be derived from a key, but often the scale you want isn’t extracted from a traditional major or minor key. For example, the blues scale is one of the most useful scales in rock, but it’s not pulled from an existing, major or minor key. So C blues is better played out of 8th position, not 5th.

- From a chord: Sometimes you may not care anything about scales or keys because you find a chord whose sound you can manipulate by pressing down additional fingers or lifting up existing fingers to create a cool chord move. The technical term for this is a cool chord move, and often the movement doesn’t involve melodic or scalar movement, just a neat way to move your fingers that results in a nice sound.

Using the Moveable Pentatonic Scale

Probably the greatest invention ever created for lead rock guitarists is the pentatonic scale. Its construction and theory have spawned countless theoretical discussions, but for rock guitar purposes, it just sounds good.

Staying at home position

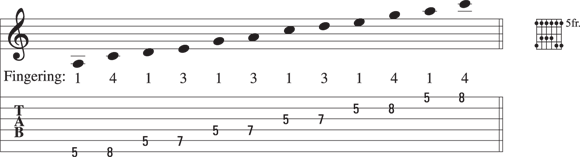

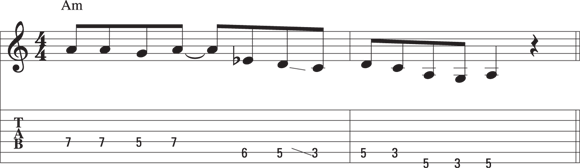

The main position for the pentatonic scale is in 5th position. This is the home position of the pentatonic scale in C major or A minor. For simplicity’s sake, this section uses one scale, A minor, for pentatonic studies for the remainder of this chapter. Most of the same qualities discussed can be applied to C major as well. Figure 4-4 is the A minor pentatonic scale in 5th position, shown in tab and a vertically oriented diagram.

FIGURE 4-4: The A minor pentatonic scale in its home, or 5th, position.

Although this scale looks to be positioned fairly high up the neck, only two of its notes — the 8th-fret C and 5th-fret A, both on the 1st string — are out of range in open position. The rest of the pitches can be found in other places in open position. For example, the 8th fret on the 2nd string is a G, which is the same G as the 1st string, 3rd fret — a note that’s easily played in open position. So as you step through these notes in 5th position, be aware that you can play almost all of those same pitches in an open-position location as well.

The next step is to learn the various ways to play the same scale but in a different position, starting on a different note. This is known in music as an inversion. An inversion of something (a scale, a chord) is a different ordering of the same elements.

Going above home position

After the home position, you may feel restless and yearn to break out of the box. To extend your reach, learn the pentatonic scale in the position immediately above the home position. Figure 4-5 is a map of the A minor pentatonic scale in 7th position.

FIGURE 4-5: Notes of the A minor pentatonic scale in 7th position.

Dropping below home position

To apply some symmetry in your life, learn the pentatonic scale form immediately below the home position. Figure 4-6 shows the scale form immediately below the home position. It’s played out of 2nd position and has one note on the bottom that the 5th position doesn’t have, the low G on the 6th string, 3rd fret.

FIGURE 4-6: The 2nd-position A minor pentatonic scale.

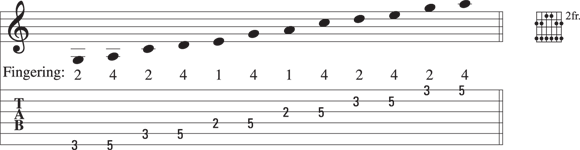

Take a moment and see what you’ve accomplished so far. You can now play one scale, the A minor pentatonic, in three different positions: 2nd, 5th (the home position), and 7th. If you look at the neck diagram with all three patterns superimposed on the frets, it looks like Figure 4-7. It’s presented in two ways: as three separate but interlocking patterns (triangles, dots, and squares), and the union of those patterns, the notes available (as just dots).

FIGURE 4-7: Three pentatonic scale forms presented as interlocking patterns and as the actual available notes.

Note how the patterns “dovetail,” or overlap: The bottom of the 5th position acts as the top of the 2nd position, and the top of the 5th position acts as the bottom of the 7th position.

Changing Your Position

What’s cool about playing up the neck is how often you get to shift positions while doing it. And make no mistake, shifting is cool. You get to move your whole hand instead of just your fingers. That looks really good on TV.

You’re ready to try some real licks.

Licks that transport

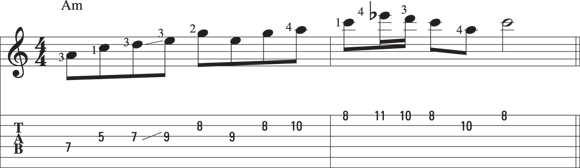

FIGURE 4-8: A short blues lick starting in 5th position and ending up in 8th position.

1♭3 4♭5 5♭7

The ♭5 can also be written as a ♭4, the ♭5’s enharmonic equivalent. So applying this formula to a C major scale (C D E F G A B) produces C E♭ F G♭ G B♭, the C blues scale.

FIGURE 4-9: A lick that dips down to 2nd position to get some “big bottom.”

From the depths to the heights

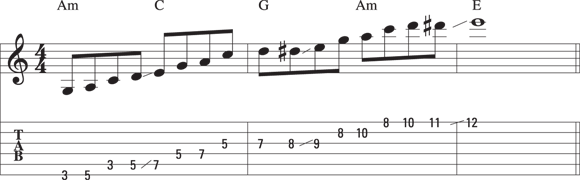

FIGURE 4-10: An ascending line that progresses through three position shifts.

Remember that although you’ve gone through different positions, various ways to shift, and five versions of the pentatonic scale, you’ve never left the key of C major/A minor.

Knowing Where to Play

After you get your hand moving comfortably around the neck, and you have a solid foundation in the A minor pentatonic scale and its different positions, try playing the pentatonic scale in its various forms in different keys. To do that, you must know how to place the scale patterns on the different regions of the neck.

Associating keys with positions

Some keys just fall more comfortably in certain positions than in others, so this section starts with the obvious, default positions for three common keys. Remember, any pentatonic scale satisfies two (related) keys: a major and its relative minor, or a minor and its relative major, depending on your orientation.

G positions

FIGURE 4-11: A riff in 7th-position G major pentatonic.

F positions

FIGURE 4-12: An F major lick with an added flat 3 in 7th position.

Note that even though this lick is in 7th position, it’s in F, not G, and so uses a different pentatonic scale form than the 7th-position form designated for G or E minor.

F minor positions

The key of F minor (and its relative major, A♭) is the interval of a major 3rd (4 frets) lower than our dearly beloved A minor, so all of its pentatonic scale positions are shifted down four frets, relative to A minor. Its home position falls in 1st position, which means all subsequent positions are up from that. So even though the A minor example had a position lower than the home position, in the F minor example, that lower position gets “rotated” up the neck to the 10th position.

FIGURE 4-13: A low riff in 1st-position F minor pentatonic.

Placing positions

One great advantage to the guitar is that after you learn one pattern, in any key, you can instantly adapt it to any other key without much thought at all. Unlike piano players, flute players, and trombonists — who have to transpose and remember key signatures to play the same phrase in another key — guitarists just have to shift their left hand up or down the neck a few frets. But the pattern — what you actually play — remains the same.

It’s as if you wanted to learn a foreign language, but instead of learning new words for all the nouns and verbs you know in English, you simply had to raise or lower your voice. Speak in a high, squeaky voice, and you’re talking French. Say the same words in a deep, booming voice and you’re conversing in Chinese. That’s what transposing is like for the guitarist. That’s how lucky you are.

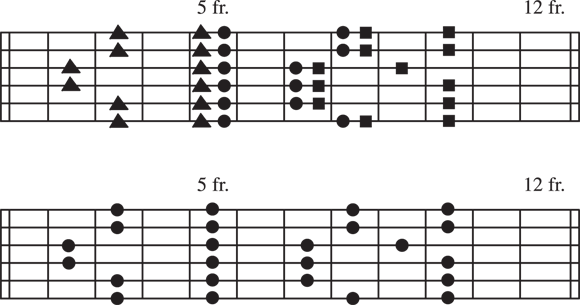

To help you know which positions are good for which keys, look at Figure 4-14. This table is by no means exhaustive and by no means the final word on where to place your pentatonic positions. It merely gives you a jumping off point to know in what general vicinity to put your hands to improvise in, say, the key of A♭.

Putting the five positions into play

After you learn the pentatonic scale in five positions, you are more than 90 percent there, technically. The next hurdle is more mental than anything else. You simply have to be able to calculate where to play any given key, and which pentatonic pattern best suits your mood. Here are some exercises you can do to limber up your brain, learn the fretboard, and become acquainted with the differing characteristics offered by the five pentatonic positions:

- Work out in different keys, spot transpose. Don’t just always play in A minor and C. Jam along to the radio, which often has strange (at least for guitarists) keys.

- Arpeggiate the chords you’re playing over. All scale positions have associated chord forms. Try arpeggiating (playing one at a time) the notes of the chord whenever that chord comes up in the progression. This is a great way to break up linear playing, and it forces you to think of the notes of the chord, rather than playing memorized patterns.

- Work out in different positions. It’s one thing to work out in different keys. It’s another to work out in different positions. Make sure you mix it up with respect to positions as well as keys.

We’re all human and we tend to favor routines and like to tread familiar ground. With pentatonic scale patterns, the comfort zone lies in the home position and the ones immediately above and below. Make an effort to treat all positions equally, however, so you can breeze through them on an ascending or descending line, without hesitating about where the correct notes are.

FIGURE 4-14: A table showing the 12 keys and their relative minors, the fret number, appropriate pentatonic pattern, and chord form.

Bringing Down the Hammer-ons

A hammer-on is a left-hand technique where you sound a note without picking it. This makes a smoother, more legato connection between the notes than if you picked each note separately. In the notation, a slur (curved line) indicates a hammer-on.

FIGURE 4-15: A hammer-on from a fretted note.

FIGURE 4-16: Various hammer-ons in a blues-rock groove.

The opening lick to Eric Clapton’s “Layla” features a series of hammer-ons that gives the passage a facility and fluidity not possible if each note were to have been individually picked. Open strings help make this lick ring out and, along with the hammer-ons, give it an ultra-legato sound.

Having Pull with Pull-offs

FIGURE 4-17: Two kinds of pull-offs to fretted notes.

Like hammer-ons, you can apply pull-offs in several different situations: You can pull off to either an open string or a fretted one; you can pull off two notes at a time (a double-stop pull-off); or you can have consecutive pull-offs (one after the other, with no picked note in between). You can even pull-off in a chordal context, in a reciprocal motion to hammering on within a chord position.

FIGURE 4-18: Several different types of pull-offs.

Slippin’ into Slides

FIGURE 4-19: A slide lets you connect two notes without picking the second one.

In addition to using slides to connect two notes, you can also employ them to enter into and slide off of individual notes, for a horn-like sound.

In addition to slides that connect two notes, you can play two other types of slides, known variously as indeterminate slides, and scoops (for ascending, and going into a note) and fall-offs (for descending and going out of a note). These slides decorate single, individual notes, and imbue them with the vocal- and horn-like characteristics where notes begin and end with a slight pitch scoop and fall-off.

FIGURE 4-20: Various slide techniques in a musical passage.

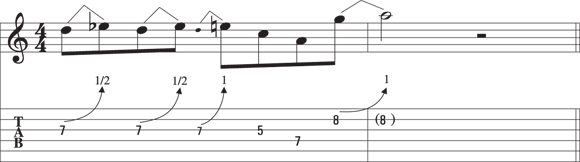

Bending to Your Will

Bending strings is probably the most important of all the articulation techniques available to a rock guitarist. More expressive than hammer-ons, pull-offs, and slides, a bend (the action of stretching the sounding string across the fretboard with a left-hand finger, raising its pitch) can turn your soloing technique from merely adequate and accurate to soulful and expressive.

Because the pitch changes in a truly continuous fashion in a bend (rather than in the discrete, fretted intervals that hammers, pulls, and slides are relegated to), you can really access those “in-between” notes available to horns, vocalists, and bowed stringed instruments. What’s more, you can control the rhythm, or travel, of a bend — something you can’t do with a hammer-on or pull-off. For example, you can take an entire whole note’s time to bend gradually up a half step; or you can wait three and a half beats and then bend up quickly during the last eighth note’s time; or you can do any of the infinitely variable ways in between. How you bend is all a matter of taste — and your personal expressive approach.

FIGURE 4-21: Two ways to bend on the 3rd string, 7th fret.

FIGURE 4-22: An immediate bend and a bend in rhythm.

Bend and release

In addition to the standard bend, where you push or pull a string to raise its pitch, you can play other bends to create different effects, such as a continuous up-and-down pitch movement through a bend and release.

Pre-bend

Another variation of the standard bend produces a “downward bend” effect through a pre-bend and release, where the pitch appears to drop. A pre-bend is where you bend the note and hold it in its bent position before picking it. This allows you to then release the note after it’s picked, creating the illusion that you’re bending downward. This is sometimes called a “reverse bend,” although that’s technically a misnomer. You can only bend in one direction, with regards to pitch: up. By letting the listener hear the pre-bent note first, however, and then executing the release, you give the impression that you’re bending (especially if you do it slowly) downward. Because pre-bends are a little trickier to set up, they are not as common as normal, ascending bends. But they are extremely powerful expressive devices and should be employed wherever you desire to create a “falling-pitch” effect.

FIGURE 4-23: A bend and release in rhythm, in sync to chord changes.

FIGURE 4-24: Three ways to use a pre-bend and release over chord changes.

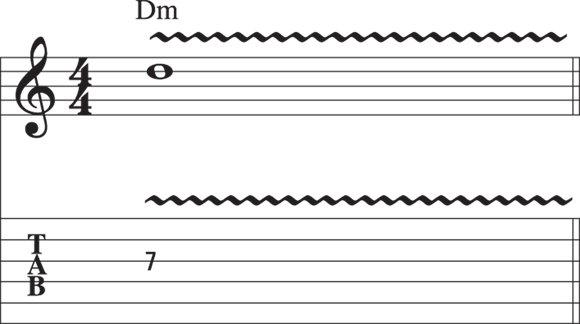

Sounding a Vibrato That Makes You Quiver

Vibrato is that wavering, quivering quality that an opera singer or a power-ballad vocalist adds to a sustained note to give it a sense of increased energy or life. Some guitarists, such as Eric Clapton, are renowned for their expressive vibrato technique. The notation indicates a vibrato by placing a wavy line over a note. You can create a vibrato several ways:

- By bending and releasing a fretted note rapidly (“fingered” vibrato)

- By giving your whammy bar a shake

- By applying electronic vibrato, through an external effect

The bend-and-release, fingered approach to vibrato is the most common, controllable, and expressive, because, naturally, you use your fingers to execute it. To play a vibrato this way, bend and release the fretted string rapidly, causing the note’s pitch to quiver. You determine the speed and intensity (how fast and how far you bend the note to achieve the wavering effect) by the context in which the vibrato appears. Slower music usually dictates a shallow and slow vibrato; faster music urges you to bend faster, so that the vibrato is detectable before the note changes pitch. The intensity of the vibrato is how subtle or obvious you want the effect to appear, independent of the speed.

FIGURE 4-25: A vibrato executed with the left-hand fingers.

Conveniently, you can refer to these forms by their open-position shapes: D, Dm, Dm7, and D7. But these forms don’t necessarily sound like those chords, because they’ve been moved or transposed. When they’re moved out of their original, open position, they produce a different-sounding chord. Be aware of the difference between a D shape and a D chord. A D shape played at the 7th position actually sounds like a G chord — because it is a G chord. Chords are named by their sound, not the shape used to create them.

Conveniently, you can refer to these forms by their open-position shapes: D, Dm, Dm7, and D7. But these forms don’t necessarily sound like those chords, because they’ve been moved or transposed. When they’re moved out of their original, open position, they produce a different-sounding chord. Be aware of the difference between a D shape and a D chord. A D shape played at the 7th position actually sounds like a G chord — because it is a G chord. Chords are named by their sound, not the shape used to create them. These are exactly the same notes (except the highest note, the 1st string, 10th fret, which is out of the home position’s range) as those found in 5th position.

These are exactly the same notes (except the highest note, the 1st string, 10th fret, which is out of the home position’s range) as those found in 5th position. You can play hammer-ons in a variety of ways: from an open string to a fretted string, as double-stops, and in succession, or multiple times, where a hammer-on follows another hammer-on. But the technique is the same; you always sound the hammered notes by slamming down a left-hand finger (or fingers) without re-picking them with the right hand.

You can play hammer-ons in a variety of ways: from an open string to a fretted string, as double-stops, and in succession, or multiple times, where a hammer-on follows another hammer-on. But the technique is the same; you always sound the hammered notes by slamming down a left-hand finger (or fingers) without re-picking them with the right hand.