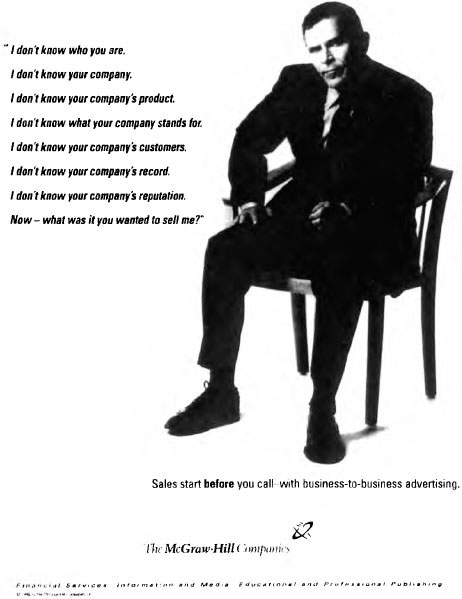

“The man in the chair”—that poster I described in the first chapter—jogged me out of my mindset as a programmer and turned me into a salesperson. The more time I spent with sellers, the more I realized that selling was not actually new to me; it was what I did every day.

Selling had already been a valuable tool for me. I used selling to convince a woman to marry me. I received a commission on performance of my radio station because I had sold the boss on my abilities. I had sold an auto dealer on a better price for that green Pontiac with the white racing stripes. (Don’t laugh; it was the 1960s. Racing stripes were groovy. Pontiacs were, too.)

Who sells? Once again, here are the words of one of the nation’s leading sales motivators, Zig Ziglar: “Everyone sells and everything is selling.”

To demonstrate, Zig uses the story of a shoe-shine stand at Lambert Field in St. Louis. One man called himself a “shoeologist” because he was so proud of the work he did. When Zig stopped by the stand, he knew that Johnny (the “shoeologist”) could convince Zig to buy the best shine.1

“Nice shoes,” Johnny would say, and he’d get Zig into conversation about how comfortable they were. Then Johnny would brush against Zig’s pants leg. “This is one of the most unusual pieces of cloth I’ve ever felt,” he’d say, and Zig explained about the rare fabric in his suit.

“You know, it just seems like a shame!” Johnny told Zig. “A man will spend over a hundred dollars for a pair of shoes; he’ll spend several hundred dollars for a suit of clothes, and all he’s trying to do is look his best. And then he won’t spend another dollar to get the best shine in the world to top everything off!” Zig, of course, upgraded his shine.

But selling is more than shoe shines or advertising messages. Selling is involved in all of human activity. Your first date was a sale: making a presentation, showing the benefits of the evening, delivering what was promised, and building the relationship beyond the first sale.

Ask your boss for a day off, and you’re making a sale. You’re presenting the facts (“It’s been a long time. …”), explaining the benefits (“Boss, you’ll get a renewed, energized employee. …”), and asking for the order (“Is Friday good for you, boss?”). After the payoff, you as the salesperson are obligated to deliver on the promises made so that the relationship grows.

Even though everybody sells, not everybody has the temperament needed to be successful at selling. All of the electronic media sellers I talked to in preparation for this book had a similar response when I asked them what makes a successful salesperson: drive and desire. More than money, it’s that desire to win on a personal level.

Some salespeople put their emphasis on researching their customers. Others make lots of calls, increasing their opportunities for more sales. Still others are closing specialists who know how to ask for the order and get it. Whatever their individual strengths in the selling process, the common thread among successful sellers is a belief in themselves and the will to win. If you don’t have it, you can’t be successful in selling.

Most lists of attributes for winning salespeople begin with the word “attitude.” Make that “positive attitude,” and you’ve found an essential quality for any salesperson. There are so many variables in selling—distractions and disappointments on the road from prospecting to closing—a positive frame of mind is essential.

Call the Dallas-based offices of the Ziglar Corporation, and you’ll hear nothing but positive remarks and can-do attitudes. Ask “How are you today?” and Zig’s assistant Laurie Magers bubbles, “I’m terrific and getting better.” That upbeat attitude is infectious.

Ziglar associate Jim Savage was a scout for the Washington Redskins in the 1970s, looking for football superstars, in his words, “someone who can play immediately and can be a great player in the league.” To make his scouting job easier, he created a ratings sheet to score each player. For the Ziglar Corporation, Savage adapted his scorecard for sales “superstars.”2

The first score on Savage’s list is attitude. You’ll hear from most successful sales trainers and recruiters that attitude is the little thing that makes the big difference. Other attributes of the effective seller are discipline, attention to detail, organizational skills, ability to listen, and persistence. See Figure 2–1.

“Most people are under the impression that knowledge will lead directly to success or that to have the ‘better mousetrap’ is tantamount to having a lock on the market,” says television sales trainer Martin Antonelli. When he cites attributes needed for selling, discipline is at the top of his list.3 Persistence and positive attitude are not far behind:

On discipline: “Without it, especially self-discipline, there can never be a maximization of potential. There are too many variables and distractions to make success likely without the aid of a plan of action and execution of that plan.”

On persistence: “Winners look for ways to get the job done. If one approach doesn’t work, another will. The loser looks for reasons to rationalize failure to him/herself and to superiors.”

On positive mental attitude: “This involves the individual suggesting to him/herself that things are going to go well. It is a frame of mind, an attitude. It sets the stage for success.”

The Antonelli Media Training Center in New York conducts 8-week courses to prepare salespeople to sell spot advertising for national television and cable networks and for the syndication marketplace.

You read Lee Masters’ comments in Chapter 1 that sales of a national network like E! Entertainment Television requires analytical skills to present schedules to buyers who are “highly sophisticated.”4 Sellers at that level need all the attributes you’ll read about in this chapter and then some: tenacity, flexibility, exacting preparation. In addition, they need a thorough knowledge of the national network business and of advertising nuances like pricing and scheduling. And of course they need to be skilled negotiators.

New selling strategies make us redefine phrases like “product knowledge,” which used to mean “knowledge of the product being sold” but in the new selling environment means, “the advertiser’s product.”

The new message of selling is that the customer is the center of the selling relationship. The newest sales and motivation books have less to say about clever closing techniques than they do about mutual respect, collaboration, trust, and honor. Words like “partnering” and phrases like “Zen selling” make it clear that there’s a new mindset to selling. The “ask for the order” paradigm is a thing of the past. No longer is sales a matter of coercion, manipulation, or out-thinking the prospect.

That philosophy underscores the definition of sales that I’m using as the theme of this book: Selling must be profitable for both the seller and the buyer.

Sharon Drew Morgen’s Selling with Integrity adds a step to the selling process, suggesting that salespeople should act as “buying facilitators.” Morgen urges salespeople to carry their personal values—including spiritual values—to work with them. In the buyer facilitation method, the seller takes responsibility for supporting the buyer in discovering the best solution to his or her problem, whether or not that solution is what the seller is selling.5

In a now-classic 1964 article in the Harvard Business Review, “What Makes A Good Salesman,” David Mayer and Herbert Greenberg call “empathy” and “drive” the two essential qualities for a salesperson.6 Empathy is the ability to feel what another person feels. As Mayer and Greenberg explain, “A salesman simply cannot sell well without the invaluable and irreplaceable ability to get powerful feedback from his client through empathy.” Zig Ziglar calls this moving “from your side of the table to the prospect’s side. Realistically that is where the sale is going to be made.”

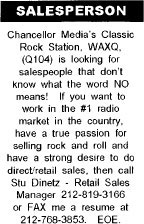

FIGURE 2-1 The words in these four classified ads indicate what it takes to be a seller: “Born salespeople.” “Highly motivated.” “Makes things happen.” “Entrepreneur.” Is it you? You’ll find out in this chapter. Courtesy WBEB, One On One Sports, WXYV, and WRCX. Used with permission.

SUPERIOR SELLERS

Here are the factors that make truly superior salespeople, according to Martin Antonelli, president of the Antonelli Media Training Center in New York City:

Discipline

Organization

Persistence

Positive mental attitude

Independence

Self-confidence

Self-control

Resilience

Hard work

High energy

Product knowledge

Anticipation and planning

Constant learning

Understanding why people buy

COVEY’S SEVEN HABITS OF HIGHLY EFFECTIVE PEOPLE

A popular book among salespeople is Steven Covey’s The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. The Covey Leadership Center serves Fortune 500 companies and smaller operations, too, with training and seminars in leadership.8

Part of the Covey Center thesis is what he calls the “character ethic”: integrity, humility, fidelity, temperance, courage, patience, industry, simplicity, modesty, and the Golden Rule. These are basic elements, but they are not seen in the success literature of the last 30 to 50 years.

Covey’s “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People” are as follows:

1. Be proactive, moving from “There’s nothing I can do” to “Let’s look at alternatives.” This step involves taking control of our feelings and our choices.

2. Begin with the end in mind. “The course of least resistance gradually wastes a life,” Covey says.

3. Put first things first, Peter Drucker said, “First things first and one at a time.”

4. Think WIN/WIN. This is another way to express the definition of “sales.”

5. Seek first to understand, then to be understood. This is another reminder of the word “empathy” in the selling process. Covey recommends “empathetic listening.”

6. Synergize. “Creative cooperation,” Covey calls it. “The essence of synergy is to value differences—to respect them, to build on strengths, to compensate for weaknesses.”

7. Sharpen the saw. This idea includes clarification of personal and spiritual values; service to the community; reading, planning, and other mental upgrades; and exercise, nutrition, and physical health.

Covey calls Habits 1 through 3 “private victories” and Habits 4 through 6 “public victories.” Habit 7 is the principle of “balanced self-renewal.”

In his book The Radio Station, Michael Keith quotes radio sales manager Charles Friedman on the subject of empathy:

You really must be adept at psychology. Selling really is a matter of anticipating what the prospect is thinking and knowing how best to address his concerns. It’s not so much a matter of out-thinking the prospective client, but rather being cognizant of the things that play a significant role in his life. Empathy requires the ability to appreciate the experiences of others. A salesperson who is insensitive to a client’s moods or states of mind usually will come away empty-handed.7

With these thoughts in mind about the qualities that make a winning salesperson, are you the person? Can you identify enough of these attributes in yourself to achieve success selling electronic media?

The good news, as Zig Ziglar says, is that everyone has every one of the qualities to be successful. How much of each quality you have will determine how much success you’ll meet in selling (or any field, for that matter).

Just to make sure you’re right for the job, the company that hires you is likely to give you a test that yields a psychological profile. Some of the tests yield catchy, even silly, marketing department-generated names for the high-performance sellers they identify:

• One company uses a list of 60 words and phrases to separate “power runners” (good sales candidates) from “walkers” (not so good).

• Another developed a “Comprehensive Personality Profile” to separate “race horses” from “plow horses.” “Race horses,” they claim, make nearly three times the average monthly sales commissions.

There are so many testing services, it’s not practical to list them all. I’ve encountered sales organizations that used handwriting analysis as a testing procedure, with pretty good results. All the testing systems have merit because they help the employer know how well suited you are for the job.

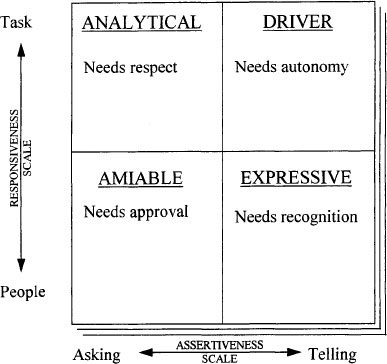

Wilson Learning, of Eden Prairie, Minnesota, was the first service I became familiar with, thanks to radio’s master seller, Ken Greenwood. Wilson Learning pioneered consultant selling for the insurance industry with its “Counselor Salesperson” program. The success of that approach enabled Wilson Learning to profile and train sellers in many fields. Greenwood added dimensions to the Wilson Learning concept and applied the systems to electronic media.

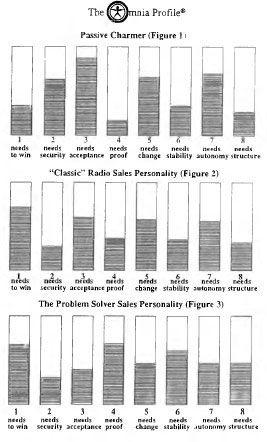

To give you a feel for the testing procedure, I’ve chosen two profiling tests, one from the Omnia Group of Tampa, Florida; the other from the H. R. Chally Group of Dayton, Ohio.

The Omnia Profile

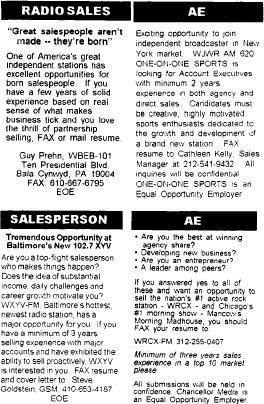

The Omnia profiling system has been adopted by electronic media companies such as Cox Television and Saga Communications. Omnia has processed more than 150,000 profiles for industries of all kinds, and they claim 93% accuracy. The service rates 14 behavioral characteristics and displays the results as a graph and as text. See Figure 2–2.

Using the data, Omnia separates sellers into two easily definable groups and then further subdivides each group (again using catchy names).

True Sales Personalities

1. The Persuasive, also known as the Entrepreneur, is an aggressive competitor who sells through relationship-building, persuasion, and charm. (See Figure 2–3).

FIGURE 2-2 “Check all the words you think other people at work use to describe you” is the first instruction in the test that yields these Omnia profiles. The candidate chooses from 82 words, then faces another list of 82 for self description. There are more than three types of sellers, but you can see that the scores for each of these three examples are radically different. ©1997, The Omnia Group, Inc. Used with permission.

2. The Problem Solver, also known as the Operations Personality, is an aggressor who needs to win (like the Persuasive), but who sells by providing a practical solution to a client’s technical problem.

3. The Persistent, also called Patient, has the qualities found in Persuasives and Problem Solvers, but adds superior listening skills, team orientation, and the patience that gives this title its alternate name.

Faux Sales Personalities

1. The Passive Charmer, also known as the Professional Interviewer, has all the friendly, outgoing charm that a salesperson needs, but is too cautious and security-conscious.

2. The Technician, also known as the Researcher, is well-informed but needs to have things right more than to win.

Mary Ruth Austin, Omnia’s vice president for marketing and communication, claims that a third of sellers in broadcasting lack the need to win that defines the true sales personality. When the best salespeople are profiled, she says, the results show high marks in the need-to-win column and low marks for needing security.9

“The most common ‘faux sales person’ on the job today is the Passive Charmer,” Austin says in a report that Omnia uses as a sales tool. “Poised, articulate, impatient, independent, and impressive, the Passive Charmer looks and sounds exactly like your best billers during the interview. The sales director becomes convinced that this candidate can sell airtime to aliens.” But it won’t happen, she says.

The problem? Austin explains that the Passive Charmer “loves making calls and meeting new people but just can’t ask for the order.” Passive Charmers fear that customers won’t like them if they try to make the sale. “No” is a personal affront to the Passive Charmer.

In Austin’s words, “There are only two ways to tell whether that glib, good-looking guy in your office is a Passive Charmer or a real salesperson—profile him before you hire him or hire him and see if he can sell.”

The H. R. Chally Group

The H. R. Chally Group is unique because they were established through a 1973 U.S. Justice Department grant to measure candidates for law enforcement. Early in their work, they realized that the same testing could be applied to sales and management people.

Every three years, Chally compiles a “World Class Sales Benchmarking Study” to document what customers want from sellers and what skills are critical for salespeople to possess. They use the database of their own clients (AC Delco, Johnson & Johnson, Pepsi, UPS, and an impressive list of more than 250 others) to classify sales types and to develop measurable standards for improvement.

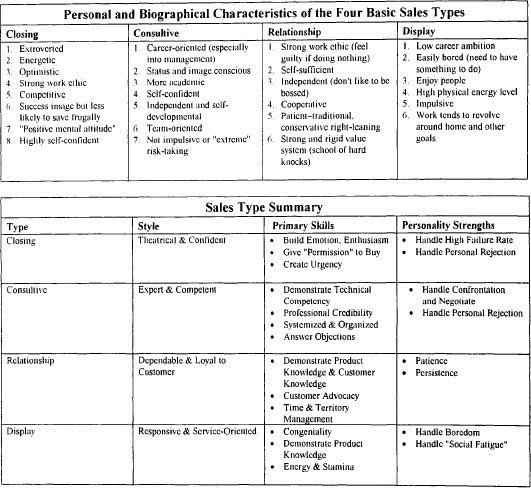

In 1991, Chally chairman Howard Stevens and writer Jeff Cox published The Quadrant Solution, a “business novel” based on customer and sales types uncovered by H. R. Chally testing.10 As the title suggests, there are four quadrants that customers and sellers fit into. A customer from a specific quadrant is best served by a salesperson who fits the same profile.

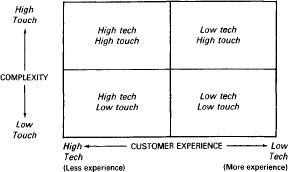

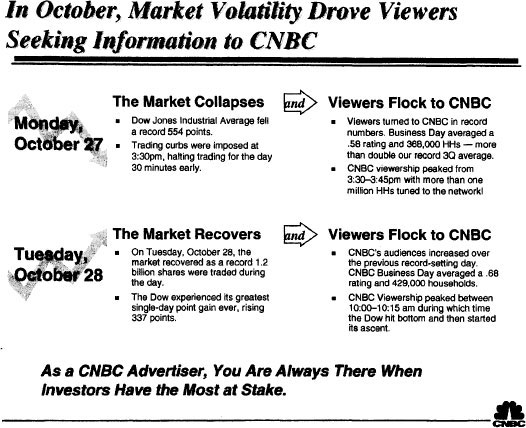

The novel’s central character, David Kepler, is manager of product development for a company in sales trouble. In a classic use of the fictional device, Kepler unfolds a cocktail napkin to demonstrate his quadrants. On the left is a measure of complexity of the customer from “low touch” at the lower left to “high touch” at the upper left. See Figure 2–4.

At the bottom is a measure of customer experience. On the left is “high tech” (a customer with less experience with the product or service) and on the right is “low tech” (more experience). Using the cocktail napkin as a visual aid, the hero explains customer orientation, marketing, and, of course, how to turn the fictional company around.

While the novel is an interesting and refreshing approach to the business book, a better source for our purposes is Chally’s How to Select a Sales Force That Sells.11 It demonstrates more clearly than the novel how the purchase quadrant, the customer quadrant, and the seller quadrant relate to each other.

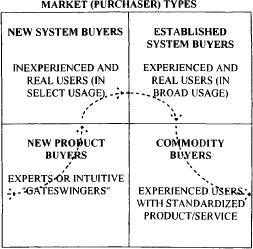

Truly new products are typically purchased by technical experts who need the newest technology to remain expert or by what Chally calls “gateswingers” who have never used the product. The gateswinger needs the product to be simple to understand yet exciting enough to be on the cutting edge. New product buyers are in the lower left quadrant. See Figure 2–5.

FIGURE 2-3 “Pat Smith” is not her real name, but the profile reproduced here is real. This is how The Omnia Group reports on sales candidates after their testing. ©1997 the Omnia Group, Inc. Used with permission.

FIGURE 2-4 This is the first in a series of quadrant diagrams that actually should be overlaid. Read the text and check the next few figures and may be you can do the overlay mentally. From The Quadrant Solution by Howard Stevens et al. ©1991 H. R. Chally Group. Published by AMACOM, a division of American Management Association (www.amanet.org). All rights reserved. Excerpted by permission of the publisher.

A “new system buyer” is a real user but an inexperienced buyer. Once this buyer becomes knowledgeable, the buyer moves from the upper-left quadrant to the upper-right quadrant of the purchaser matrices.

Commodities buyers are in the lower right quadrant. These customers are so totally experienced with a product or service that purchase and usage are standardized and routine. The example the H. R. Chally Group uses is: “When was the last time you asked how to use an electric pencil sharpener?”

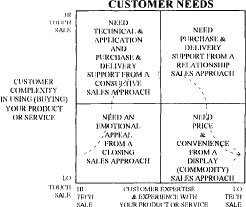

Combine the complexity/experience chart (Figure 2–4) with the purchase type chart (Figure 2–5), and you have Figure 2–6.

Finally, the seller is matched to the individual needs of the customer. In a section on understanding the four types of salespeople, Chally reminds us that there is no “universal” salesperson. “Every pro baseball player must throw, catch, and hit. Yet what it takes to be a great hitter or a 20-game-winning pitcher are dramatically different.”

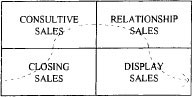

Matching the right salesperson to the right customer requires four types of sellers, and Chally divides them this way: closer, consultative, relationship, and display sellers.

• Closer. All salespeople must use closing techniques. But the “closer” term used here describes a personality type, not closing skills. The closer must quickly establish a prospect’s emotional desire and need for the product or service. Closers are good at demonstration sales and hightech vanity sales, according to Chally.

• Consultative. Some people call this “IBM selling” because it’s the approach taken by big-ticket and high-technology sellers. It also works best for intangibles like media. The sales environment requires patient, interpersonal contact, or “consultation,” with the customer.

FIGURE 2-5 Now you see the purchaser type and how each relates to the “complexity” and “experience” matrices in Figure 2–4. The dotted line through the middle represents the product life cycle from introduction to maturity. From How to Select A Sales Force That Sells, ©1997, The H. R. Chally Group. Used with permission.

FIGURE 2-6 A pattern begins to emerge as you look at these quadrants. The “customer needs” are outlined on the same matrices used in Figures 2-4 and 2-5. ©1997, The H. R. Chally Group. Used with permission.

• Relationship. The sale is largely dependent on the relationship between the seller and the customer. A “good” relationship will generate some business eventually. This type of seller can move to a competitor and take a client list along. Stock brokers are good examples.

• Display. There’s little personal involvement in display selling. Most display sellers (retail clerks, bank tellers, catalog order takers) get paid even if they don’t make the sale.

Figure 2–7 shows how the four sales types match the purchase types and customer needs in quadrant segmentation. You can imagine overlaying each chart on the previous one to arrive at how certain types of sellers match with customers. An outline of the personal characteristics of each type of seller appears in Figure 2–8. The profile from testing by the H. R. Chally Group is several pages long. You’ll find a sample in Appendix C.

As a seller of electronic media, your primary objectives are

1. Developing new business

2. Maximizing revenues

3. Retaining current business

That’s not a job description, but an overview of your job goals.

There’s no simple list of duties that will cover every sales job, but here are typical examples:12

• To prospect for potential advertisers

• To provide solutions to advertisers

• To create value for your medium

• To create a competitive advantage for your medium

• To process orders

• To assure schedules are run as ordered

• To assure that billing is handled properly

• To monitor other media in your marketplace

• To understand customers’ industries and their goals

• To execute your organization’s sales strategies

• To answer to management

• To set personal goals as well as company goals

• To work on goal-getting as well as goal-setting

You’ll work within a sales department under a person whose title may be sales manager, director of sales, or marketing manager. There are other titles you’ll encounter, depending on the organization you’re working for. Your manager will outline your job specifically and set the strategies for your selling effort. Those decisions may be made as part of a team that includes corporate leaders, or with you and your colleagues in the sales department. Often it’s a two-step process: first, corporate management and local sales managers set strategy, then the selling staff adds plans for tactical implementation of the strategy.

FIGURE 2-7 Matching the right salesperson to the needs of the customer requires understanding of the four types of sellers identified by the H. R. Chally system. ©1997, The H. R. Chally Group. Used with permission.

FIGURE 2-8 Here’s a quick overview of each of the four basic sales types profiled by the H. R. Chally Group. It’s from How to Select a Sales Force That Sells, ©1997, The H. R. Chally Group. Used with permission.

There is no single structure that works for every electronic media selling team, so you’ll find each sales department is slightly different. Structural differences are based on a variety of factors: the medium itself, the company that owns the facility, specific needs of the advertising community, the size of the market, and choices made by local sales management. (We will further discuss sales management in Chapter 4.)

Writing in High Performance Selling, sales trainer Ken Greenwood outlines four stages of a salesperson’s career:

1. The Novice. New sellers are faced with learning their own product and the industry in general. This is the point at which presenting, planning, and prospecting are most important. Novices learn to keep good records, to set a high activity level, and to believe in what they sell. “All basic, fundamental things,” Greenwood says.

2. The Learner. This is the level at which salespeople begin to listen rather than talk, to explain the presentation rather than simply make it. They understand buying criteria. They gain confidence and a better understanding of the selling process.

3. The Competent. Sellers at this level become less product-oriented and more aware of solving problems for the buyer. They are able to find options and alternatives. They begin to negotiate. This is also the point at which their versatility becomes more apparent.

4. The Professional. The account is a customer, not just a sale. Salespeople at this level know their accounts well enough to forecast buyer needs and to combine accounts in promotional activity. They have a commitment to being professional and a deep belief that their services are needed. At this stage, the salesperson thinks like an independent contractor or a private business person.13

“Someplace between the learner stage and the competent stage,” Greenwood says, “high performers make a transition. At first they are very much like the fiddler on the roof, scratching out a living and balancing on the ridgepole. On one side are their ego and their ego strength—what they want. On the other side are empathy and an understanding for what the buyer wants.”

There’s that word “empathy” again. Understanding what the buyer wants makes the customer the center of the selling process. As we saw in Chapter 1, focusing on the customer blurs the traditional lines between selling and marketing.

“Dear Ed Shane: One of the secrets of doing business profitably—and doing more of it—is selling yourself first.” The letter was designed to introduce me to a special price on Hewlett Packard printers. The premise was that my letters have to look good in order for me to sell myself. When I saw “sell yourself first” at the top of the letter, I thought how ironic it was that such a message would arrive as I was writing this chapter on personal marketing, which is, in effect, selling you as a product.

Before you sell any product, you have to sell yourself. You sell yourself as a product when you pitch the sales job. You sell yourself as product when you make the appointment with a prospect to show that big presentation. Politicians do it. Entertainers do it. CEOs do it. No matter what business is involved, everybody can take advantage of a personal marketing plan.

ALL I KNOW

Allen Shaw’s career took him from radio programmer to leader of several major broadcast companies. He formed Centennial Communications to operate his own stations. When I asked him to contribute to this book, he sent me a note that said, “This is all I know!” Here is his input.14

The basics of selling:

1. Know what your product can do for the buyer.

2. Know how the buyer will benefit from your product.

3. Prepare your presentation with thought, logic, and personal charm.

Qualities of a successful salesperson:

1. Desire to succeed.

2. High degree of empathy with potential clients.

3. Integrity and credibility.

4. Hard work ethic.

5. Optimism—nonreactive to rejection.

If that’s all Allen knows, it may be enough!

Today’s customer-oriented, service-driven marketplace demands personal marketing—positioning yourself the way you’d position a product. That means attention to packaging and sampling, just like a product. Being good at selling your product and being good at selling yourself are two different aspects of selling. You need to master both.

Your public image will be either enhanced or diminished in everything you do, whether you’re on a golf course, at a restaurant, in a meeting, or doing charity work. In Personal Marketing Strategies, Mike McCaffrey writes that by actively participating in a charitable organization, you will be perceived as a doer, and that will transfer to your image as a seller. “Having already ‘established’ yourself in their minds as competent and easy to work with, their perception of you can easily be transferred over into business concerns.”15

McCaffrey suggests that a seller becomes an activist or a doer in charitable, civic, social, or political organizations. From my own experience, it’s important to find activities or outlets you enjoy. If you’re giving your time, you’ll want to be with pleasant people and working for an organization you truly believe in, something in line with your personal values. Once you’ve found the right fit, you can look for people who can help—contacts to enhance your selling.

One of the pioneers of electronic media, David Sarnoff, founder of RCA, left us a powerful quotation about the effects of goal-setting: “A life that hasn’t a definite plan is likely to become driftwood.”

If you want to succeed in any endeavor, you must have a plan. You need to know what you want to accomplish so you’ll know you’ve done it. That’s what goal-setting is all about. Most people spend more time planning their vacations than they do their lives. When it comes to life goals, they substitute wishes instead. “I want to be happy” or “I want to be rich” is as close as many get to the idea.

For the seller, only the most specific goal-setting works. Goals that are vague or poorly developed yield vague or poorly developed results. Break your broad view into short-term goals—daily, weekly, monthly, yearly—to provide benchmarks of your successes.

“If it’s not in writing, it’s not a goal,” says Tom Hopkins. “The day you put your goal in writing is the day it becomes a commitment that will change your life.”

Hopkins calls the sellers who take his training “champions.” For his sales Champions, he outlines these rules for goal-setting:

1. Put your goals in writing. “An unwritten want is a wish, a dream, a never-happen.”

2. Make your goals specific. “If it’s not specific it’s not a goal,” Hopkins says, “Broad desires and lofty aims have no effect. Until you translate your vague wishes into concrete goals and plans, you aren’t going to make much progress.”

3. Goals must be believable. Hopkins quotes his mentor, sales trainer Doug Edwards: “If you don’t believe that you can achieve a goal, you won’t pay the price for it.” Let me take that a step further: If you don’t believe you can achieve a goal, then you won’t.

4. An effective goal is an exciting challenge. If your goal doesn’t push you beyond where you’ve been before, it isn’t going to provide a challenge or change your lifestyle.

5. Adjust your goals to new information. “Set your goals quickly and adjust them later if you’ve aimed too high or too low,” Hopkins advises. Goals are often set in unfamiliar territory. As we learn more about realities, we adjust goals down if they’re unbelievable or up if they’re too easy.

Here are ten strategies for marketing yourself from Shane Media’s Power Selling Tactics.16

1. Become the CEO of your own career. Develop your own strategic plan—short-term and long-term goals for yourself. Where are you now? Where do you want to be in 1 year, 5 years, 10 years? Set up a logical, meaningful way to measure each goal.

2. Make connections. Some people can help you achieve your goals, while others cannot. Learn who belongs to which group and target your personal marketing campaign to those who can help. Depending on your goals, these people may include the president of your company, the mayor, or the head of a civic group.

3. Get things done. Be the person who people rely on to take an additional assignment or to volunteer on weekends. Achievers move forward because they make everybody else’s job easier.

4. Make the boss look good. This strategy is a corollary to number 3. Getting things done and getting ahead mean doing it within the system. Personal marketing means treating the boss like a client.

5. Be visible. Be seen where your clients and connection list are seen. Go outside your organization into professional, civic, and cultural circles. High visibility keeps the caliber of your performance high, because you’re being watched by high-caliber people.

6. Make appearances. The local service clubs (Rotary, Exchange, Lions) need panelists and speakers. Offer topic ideas and volunteer to address local groups about your medium specifically and advertising in general. The most important part of a speech is the 15 minutes immediately afterward when you make contacts and collect business cards.

7. Publish. It sounds daunting, but it’s not. Industry trade publications regularly look for fresh perspectives. Your local paper accepts editorial essays (often called “Op/Ed” for “Opinion and Editorial”). Don’t overlook the weekly suburban papers and the entertainment freebies. Letters to the editor get recognition, too.

8. Get third-party support. Ask for introductions or testimonials from your connection list and from groups you’ve served or addressed. People like to help. They also like to hear reports of how valuable their help really was.

9. Offer help. You should reciprocate—provide introductions and offer leads. In marketing terms, this exchange is called giving free samples. Offer information to newcomers to the business. Share your skills.

10. Research your personal packaging. It’s “dress for success” and more. Your clothing should fit your target audience and give them confidence in you as a product. Even before they see your clothing, however, they see your face. In marketing terms, the face is your “label.” You may not be able to change its features, but you’re in charge of its expressions. Make sure your face communicates what you want to say about your self-esteem.

6. Dynamic goals guide your choices. If you’ve set your goals properly, they’ll show you which way to go on most decisions.

7. Don’t set short-term goals for more than 90 days. Once you’ve developed experience in setting short-term goals, you might set them for a longer or shorter time. To begin, use 90 days as the limit so you can keep your interest high and see measurable results in just three months.

8. Balance long-term and short-term goals. Create enough short-term goals so you can measure progress while waiting for the payoff period of the long-term goal.

9. Include your loved ones. Let the family know what you’re trying to achieve so they can cheer you on.

10. Set goals in all areas of your life. Goals are not just about money and new cars. Set goals for your health, for your exercise plan, for your family life, and for your spiritual life. Goals work when they’re used, so make good use of them in all areas of your life.

11. Goals must harmonize. If your goals fight with each other, you lose. As Hopkins says, “Use your goals program to get rid of frustration, not to create it.”

12. Review your goals regularly. Long-term goals can only be achieved if they are the culmination of your short-term goals. New goals should rise out of previous goals that you’ve achieved.

13. Set vivid goals. I like Hopkins’ use of the word “vivid,” because it conjures a clear and concise picture of something concrete. He tells the story of seeing a corporate jet parked next to the commercial airliner he was on, so he wrote in his book, “Ten-year goal—jet.” Sure enough he achieved the goal, ten years to the day.

14. Don’t chisel your goals in granite. Be ready to change if you have to. Hopkins followed the story of the jet with a story of his first fuel bill, for $882.00. At that rate, his jet would cost him $30,000 a month, so he sold it immediately.

15. Reach into the future. “The whole idea of setting goals is to plan your life rather than to go on bumbling along, muddling through, taking it as it comes,” Hopkins says.

16. Have a set goal for every day and review results every night. This discipline will save you a lot of frustration. You’ll find yourself able to feel good about little events. My wife, Pam, attended a seminar whose leader suggested using a Post-It® note to write one key accomplishment each day, then stick it on the mirror so it’ll be there to motivate you the next morning.

17. Train yourself to crave your goals, which reinforces the earlier point about making goals vivid. By visualizing what you want, you make the possibility real and motivate yourself to achieve it.

18. Set activity goals, not production goals. “How many prospecting calls will I make today?” not “How many packages will I sell?” Even if your sales slump, your activity will be stimulated by your goal-setting.

19. Make luck work for you. “Winners understand that luck is a manufactured article,” Hopkins writes. “They think in terms of good things happening to them and make themselves good-luck-prone.”

20. Start now. The only way to elaborate on those two important words is to repeat them: start now.

Hopkins recommends setting aside 10 minutes a day for 21 days to work on goals and to revise them. After that, he says, “Two minutes a day plus one hour a week will keep you flying toward the immensely greater and richer future that the goal-setting system will deliver.”17

Goal setting is a process: setting, reaching, and revising goals. Dennis Conner, the skipper of several U.S. entries in the America’s Cup sailing race, says, “I don’t know if this process ever becomes automatic. You have to keep working it out. When you get good at the process of setting goals and meeting them, you get good at the art of winning.”

In The Art of Winning, Conner advises, “Make your goals central to everything you do, so everything else shapes itself around them. You become so committed to your goals that, finally, you become committed to the commitment itself.”18

If “time management” is a misleading title, I apologize. We cannot actually manage time; we can only manage ourselves and, therefore, use the time at our disposal effectively. Effective self-management enhances relationships and achieves results. We tend to call it “time management” anyway, most likely to give us the sense of controlling time.

No one has enough time, yet every one of us has as much as there is. It’s the one resource that is distributed equally no matter who you are. The great paradox is that I can’t think of one of my friends or acquaintances who hasn’t said, “Where does the time go?”

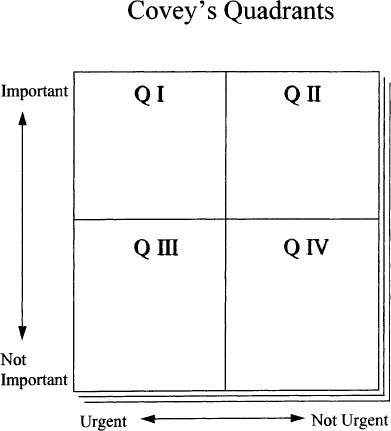

Steven Covey captures time management with one phrase: “Organize and execute around priorities.” That’s in line with the third of Covey’s “Seven Habits of Highly Effective People”: “Put first things first.”

There are four generations of time management, according to Covey, each building on the one that came before. First, there were notes and checklists, an effort to recognize the many demands placed on our time and energy. Second came calendars and appointment books, an attempt to look ahead and schedule the future. Third was adding priorities, clarifying values, and comparing the relative worth of activities to those values.20

Watch a major league pitcher closely. First he checks the runner on first base. Then he checks the signs given by the catcher: Fast ball? Change up? Then the pitcher withdraws into himself until the windup and the pitch.

Most pitchers could probably get the ball over the plate with their eyes closed. They’ve practiced so much. They’ve measured that 60-foot, 6-inch space so often in their mind and in reality.

If you’re a basketball fan, think of a player at the top of the key with a shot open. There’s no time to measure distance, trajectory, or velocity. The best players know how to sink a shot from the top of the key, from the free-throw line, and from virtually any place on the court. Even with their eyes closed, they have a good chance of hitting the hoop.

Athletes work on that kind of visualization regularly. They win the mental game long before they take the field for the physical equivalent. Every pitch, swing of the bat, forward pass, or backhand stroke accomplished in practice hones the skill needed for the game.

Salespeople, too, have a powerful tool in visualization. When you see yourself as a successful seller, when you see yourself reaping the rewards of your work, you condition your mind to accept the skills you have. Visualization allows you to move effortlessly through the sales process, because you’ve already covered that territory in your mind.

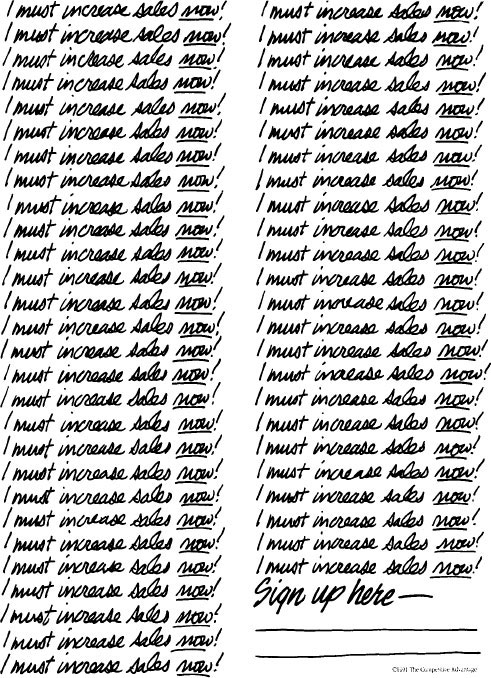

Coupling visualization with positive self-talk gives you an even stronger psychological make-up. You can create a positive, successful attitude for yourself that permeates your entire being by using affirmations. As the word suggests, “affirmation” involves “affirming” or reinforcing your positive thoughts. The idea is to use repetition of positive messages to your subconscious in order to purge negative or self-defeating messages.

An affirmation consists of three elements:

1. Statement. It’s called “self-talk” because you’re saying positive things to yourself.

2. Imagery. Visualization of a scene in a positive, successful way.

3. Emotion. Experiencing the scene and hearing the self-talk in a way that is felt deeply.

“When you use affirmations,” former NBC public relations expert Mike McCaffrey says, “you are providing your subconscious with positive inputs. Your subconscious accepts that input, your self-image changes and grows, and your comfort range expands.”

Things that once seemed overwhelming or out of reach come into your control because you’ve conditioned your response mechanism to accept positive outcomes.

Affirmations are visualizations of the future, but expressed in the present tense. Your subconscious works only in the present, so your communication with it must be there, too.

Let’s say your goal is to drive a new sports car within a year. Your affirmation would not be to say “I want” or “I will.” Rather, you tell yourself, “I enjoy driving the Jaguar XK8.” You visualize yourself in the car, driving the streets you drive today. See yourself squeezing the wheel, adjusting the seat for your comfort. In other words, experience it in your own mind.

Don’t do it once. Do it every day for several minutes a day until the thought of the car becomes part of you. That makes your goals not only alive on your planner, but also alive in the deepest reaches of your subconscious.

This isn’t daydreaming. It’s an effective exercise in positive mental conditioning.

Here are other affirmations:

“I like meeting new people and making friends.”

“I’m very proud to be a salesperson.”

“I produce $_______________ sales volume annually.”

“I consistently earn $___________ every year.”

The sales volume and income affirmations should state your goals, not your actual volume or salary. Remember, use future outcomes stated as present-tense facts for your subconscious.19

“While the third generation has made a significant contribution,” Covey writes, “people have begun to realize that ‘efficient’ scheduling and control of time are often counterproductive. As a result, many people have become turned off by time management programs and planners that make them feel too scheduled, too restricted …”

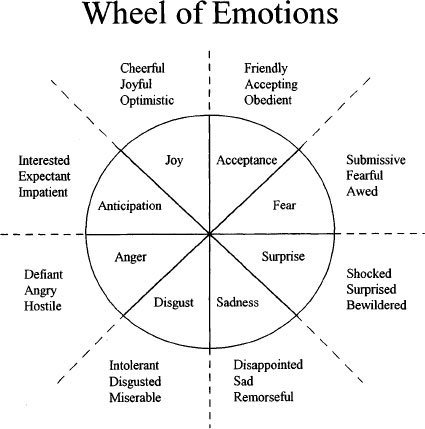

That led Covey to the fourth generation of time management, which focuses on results, not on time. He developed the time management matrix I’ve adapted for Figure 2–9. The two factors that define any activity are urgency and importance. “We react to urgent matters,” Covey says. “Important matters that are not urgent require more initiative, more proactivity. We must act to seize opportunity, to make things happen.”

His point, of course, is that we are easily diverted into responding to the urgent, not the important. As long as you focus on the urgent and important matters in Quadrant I, they dominate your life.

Covey notes that people overwhelmed by Quadrant I often escape to Quadrant IV: “That’s how people who manage their lives by crisis live.” Others spend time in the “urgent, but not important” activities of Quadrant III. Covey concludes that people who spend time almost exclusively in Quadrants III and IV “basically lead irresponsible lives.”

In Covey’s mind, Quadrant II is the heart of effective personal management: things that are not urgent, but are important. “It deals with things like building relationships, writing a personal mission statement, long-range planning, exercising, preventive maintenance, preparation—all those things we know we need to do, but somehow seldom get around to doing, because they aren’t urgent.” The things that make a difference in your life will most likely fit into Quadrant II.

One of my favorite remarks in management literature is Peter Drucker’s categorization of activities into “priorities and posteriorities.” Priorities are generally set by pressures to get things done. Drucker says that pressures favor yesterday. “They always favor what has happened over the future, the crisis over the opportunity, the immediate and visible over the real, and the urgent over the relevant.” He advises, that in addition to setting priorities, you set “posteriorities,” that is, decisions about what not to do.21

Drucker reminds us of the circus juggler who keeps many balls in the air, but for only 10 minutes at a time. Most people can do two tasks at once, but few, he says, can do three tasks simultaneously. (He calls Mozart the only exception.)

There are a number of time management systems that contain day planners, calendars, priority lists, and other aids to assist the seller in keeping first things first. Most started as paper-based calendar books like Franklin Planner,™ Day-Timer,® and Day Runner.® Many have been adapted to computer software. (Franklin and Covey Leadership merged their companies to offer “life leadership products” as opposed to “time management systems.”)

One thing I’ve noticed is that no one system fits every need. Some sellers use the Franklin system with a fervor approaching religion. They begin with seminars on time management and follow with a ritualized use of Franklin planners, note pads, and reminder cards to capture ideas and check off accomplishments. Others can’t stand the Franklin system and opt instead for the Day-Timer system.

I found that neither of those suited me personally, but somehow portions of the Day Runner system did, so I mixed and matched to suit my airplane and briefcase lifestyle. There are a few systems that are designed specifically for media and advertising professionals, but that’s still no guarantee they’ll fit your specific needs.

Most of the prepackaged time management systems available offer a variety of formats, from pocket-sized to ![]() binders. They also allow you to mix and match to accommodate your specific needs. Some add touches like pictures of polar bears, mountains, beaches, and golf courses that not only personalize the planner but also remind the user of goals or motivators.

binders. They also allow you to mix and match to accommodate your specific needs. Some add touches like pictures of polar bears, mountains, beaches, and golf courses that not only personalize the planner but also remind the user of goals or motivators.

FIGURE 2-9 “We react to urgent matters,” says Steven Covey. That’s why most people tend to live in Quadrant I. If you don’t have important and urgent matters nagging you, then you might live in Quadrant III, because urgency will get you. The ideal is life in Quadrant II, taking care of long-term, important issues.

It comes down to personal taste. The key is to use some system and make it your one-stop reference for goal-setting, goal-getting, scheduling, and personal record keeping.

“There is no fool who is happy, and no wise man who is not,” said the Roman philosopher Cicero. In the centuries since, there has been considerable study of the plight of the unhappy fool, but little attention given to what makes us happy.

The magazine The Futurist published a special report called “The Science of Happiness” and noted that psychological literature between 1967 and 1995 included 5,119 abstracts mentioning anger, 38,459 mentioning anxiety, and 48,366 mentioning depression. In the same period there were only 1,710 mentioning happiness, 2,357 mentioning life satisfaction, and 402 mentioning joy–a 21:1 ratio of negative to positive.

In the report, authors David G. Myers and Ed Diener cite four traits of happy people:

1. Happy people like themselves. They have high self-esteem.

2. Happy people feel personal control. They feel empowered rather than helpless.

3. Happy people are optimistic.

4. Happy people tend to be extroverted.

As sellers, we might equate money with happiness, but money is simply a means to an end, not an end in itself. If we create an appropriate environment for our clients’ messages, our clients get results, our advertising is paid for, we receive a commission, then we use that income for “life management” or “life leadership,” as the time management people call it.

In How to Master the Art of Selling, Tom Hopkins admits that money is important, so much so that it’s first among his “six motivators” and is related to many of the others. Here’s a rundown of those six motivators:

1. Money. “Money is good as long as what you earn is in direct proportion to the service you give,” says Hopkins. “All that money can do is give you opportunities to explore what will make you happy.”

2. Security. Abraham Maslow tells us that the average human being strives daily to supply physical needs. Hopkins equates this with security, but he relates it also to money: “In a primitive society, security might be a flock of goats; in our society, security is something bought with money.” (For more on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, see the discussion of needs analysis.)

Enhancing Happiness22

When people are asked to describe the best part of their favorite activity, the surprising answer is “designing or discovering something new.”

In his book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi of the University of Chicago says that people as diverse as dancers, rock climbers, and composers “all agree that their most enjoyable experiences resemble a process of discovery.”

Csikszentmihalyi is considered a pioneer in “happiness research” and offers these suggestions for enhancing your own personal creativity and happiness:

1. Try to be surprised by something every day.

2. Try to surprise at least one person every day.

3. Write down each day what surprised you and how you surprised others.

4. When something strikes a spark of interest, follow it.

5. Recognize that if you do anything well it becomes enjoyable.

6. To keep enjoying something, increase its complexity.

7. Make time for reflection and relaxation.

8. Find out what you like and what you hate about life.

9. Start doing more of what you love and less of what you hate.

10. Find a way to express what moves you.

11. Look at problems from as many viewpoints as possible.

12. Produce as many ideas as possible.

13. Have as many different ideas as possible.

14. Try to produce unlikely ideas.

These tips on happiness were part of a special report, “Science Pursues Happiness” in The Futurist, September–October 1997.

3. Achievement. Hopkins divides people into two groups: achievers and nonachievers. He claims that “almost everyone wants to achieve, but almost no one wants to do what’s necessary to achieve.” That’s why achievers make up only 5% of the world, according to Hopkins. No salesperson can succeed without a desire for achievement.

4. Recognition. Hopkins feels people will do more for recognition than for anything else, even money. That’s why, he says, kids do cartwheels in their back yards—so their parents will pay attention.

5. Acceptance by others. Everyone wants to be liked, but that’s not quite what Hopkins is saying here. The key, he says, is to “surround yourself with the people most like the person you want to become.” Work to gain their acceptance. Remember that you’ll demand more approval from the world than the world is willing to give.

6. Self-acceptance. More important than the acceptance of others is self-acceptance—what Hopkins calls “calcium for the bones of our personalities.” Self-acceptance is “the state of being your own person. You have arrived exactly where you want to be.”

You’ll be put in a position to do the work long before you’re paid for it. Sellers may start with a draw or salary, but they soon shift to commission. The trend in electronic media is toward spending more on commission than on salaries. (There’s more on salary and commission in Chapter 4.)

Before the commission comes, you’ll make presentation after presentation, you’ll do the consulting, you may write the advertiser’s commercial message—all for free. Closing simply affirms the work you’ve already done.

First-year salespeople spend more time learning than earning. You learn the medium you’re selling, then you learn about the prospect’s business. High-learn equals low-earn.

Chris Lytle of the Lytle Organization calls sales “a series of defeats punctuated by profitable victories.” In school, an “A” grade might be 90 to 95%. In sales, it’s more like 25%. Successful salespeople learn to handle rejection. “No” is not personal. Successful sellers tell themselves that every “no” is just a way of getting closer to a “yes.”

The good news is that hard work is rewarded.

It was July, and I had been given my first assignment as a salesperson in Houston. This was my opportunity to show what I could do as a seller, moving beyond the sales support role I played as head of the programming departments at radio stations. Where should I start? Or, better yet, how could I start with a win? I’d rather come home with my first sale to build my own confidence and to show the station they’d made a good investment in me as a seller.

I remembered talking a few months earlier with Buddy Brock, a Houston band leader who also ran a talent agency. In passing, he had said to me how he wished he could start booking Christmas parties in the summer so he’d know how his year would end. Nobody in Houston, Texas, thinks about Christmas in July, but I called Buddy and reminded him of the conversation. Yes, he would be interested in a radio campaign that sold Christmas bookings in the heat of summer. My first close!

“If You Can’t Close, You Can’t Sell” is the title of a chapter in Charles R. Roth’s Secrets of Closing Sales, a classic in the sales field.23 The premise of the book is that a salesperson should try for closing from the beginning of every sale. “Make every call a sales call,” it says, and describes a seller who asks for the order on first handshake.

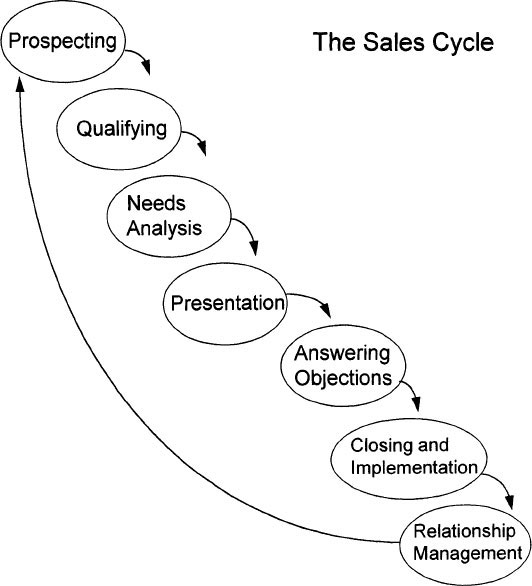

There’s no denying that every sale must have a close. That’s the moment when the prospect becomes a customer by saying “Yes!” To understand the dynamics of closing (and to use Roth’s “Master Closing Formula,” which I’ll describe later), you have to begin at the beginning and follow the steps toward closing:

1. Prospecting

2. Qualifying

3. Needs analysis

4. Presentation

5. Answering objections

6. Closing

7. Relationship management

Those seven steps are the sales cycle. At any one time, you’ll have a number of clients at a variety of points in the sales cycle. This is why salespeople are looked upon as independent managers of their own jobs. Only the salesperson knows for sure where each customer is in the cycle. So you must take charge of the process personally.

So much has been written about the sales cycle that you’ll find lots of different words to describe those seven basics. Here are a few examples:

• Selling Power magazine combines “prospecting” and “qualifying” under “call preparation.” I prefer to keep them separated.

• Michael Keith, writing in Selling Radio Direct, equates “prospecting” with “list building.” I agree and have adapted some of his ideas on the subject.

• I prefer to separate “qualifying” from “needs analysis,” even though one begins to dissolve into the other. I tend to take the word “qualifying” literally and remind myself that there are some prospects we just shouldn’t sell. (I’ll explain that idea later.)

• In Charles Warner’s classic textbook, Broadcast and Cable Selling, “prospecting and qualifying” are termed “researching and targeting.” That also assumes the step of “answering objections,” which I prefer to separate out so you can see how objections are a natural part of the sales process.

• You might see “negotiation” as a separate element of the sales cycle. I include it as part of closing. If you’re at the point of negotiation, the sale is emotionally closed. Only the terms of the sale are still in question.

• I feel the same way about “servicing” accounts. Getting the paperwork done, the order processed, and the commercial copy prepared is part of closing. Otherwise sellers of electronic media could not deliver their product, and, technically, there’d be no close. Servicing and implementation is a bridge between closing and relationship management.

• “Relationship management” begins the process all over again by helping us retain clients. Repeat business keeps us all gainfully employed.

You’ll find that the seven points I’ve listed are contained in every list, regardless of what they’re called and regardless of how many entries there are in the list. The specific words I have chosen to use are the result of letting electronic media selling experts guide me. (See Figure 2–10.)

“In sales, you get the customers you deserve,” says Mark McCormack, author of What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School.24 If you don’t believe this, McCormack suggests you look at your company’s top producers. Who do they sell to? Who are their prospects? How do their customers stack up against yours in terms of power, friendship, integrity, and decisiveness?

McCormack describes the perfect customer as (a) a friend, (b) a decision-maker, and (c) someone who likes what is being proposed and will form an alliance with you as the salesperson to overcome the forces of resistance. That description reinforces the definition of selling presented in Chapter 1: when the buy is right, the customer needs no convincing. Closing has to be profitable both for your company and for the customer.

FIGURE 2-10 The steps of the sales cycle in order. I’ve tried to indicate that each flows into the next. The line from Relationship Management back to Prospecting means you should follow the arrows, then start again.

How can you identify “the perfect customer”? Here are Mark McCormack’s guidelines:

1. The customer talks, you listen. The customer describes the problems and the solutions. From the beginning, you know if there’s an internal conflict that affects the sale. The sure sign the customer is a friend is if you are included in the solution.

2. The customer needs you; you don’t abuse it. Not only are you needed, but you’re trusted, too. You don’t over-promise. You don’t overspend. In McCormack’s words, “You have to bend over backwards to be less fair to yourself” (McCormack’s words, my emphasis.)

3. When the customer says no, you still feel good. If there’s no interest, that’s clear immediately. The customer respects your time. If there’s interest but rejection follows, that’s also clear. The perfect customer prepares you for rejection so you don’t lose face. You never feel that you’ve been stiffed.

4. The customer makes you better. If the customer has high visibility or exalted status in the community, the prestige rubs off on you. The fringe benefits of associating with some customers often outweigh the commissions, especially if you learn to do your job better or to reach a personal goal.

Perfect customers or not, you can separate your prospects into five categories:

1. Those who don’t believe in advertising.

2. Those who believe in advertising but don’t believe in the medium you’re selling.

3. Those who believe in your medium but not specifically in your outlet—your station, system, or network.

4. Those who have used your outlet in the past and were dissatisfied with the results.

5. Those who’ve had no problems at all with your outlet.

Your sales manager or sales director will advise you to limit the time you spend trying to convince the people in category 1 to change their minds. It can be done, but it’s a long, frustrating process. You’ll have more success selling category 2 than you do category 1, more selling, 3 than 2, and so forth. You find yourself longing for prospects in category 5, but those are few and far between.

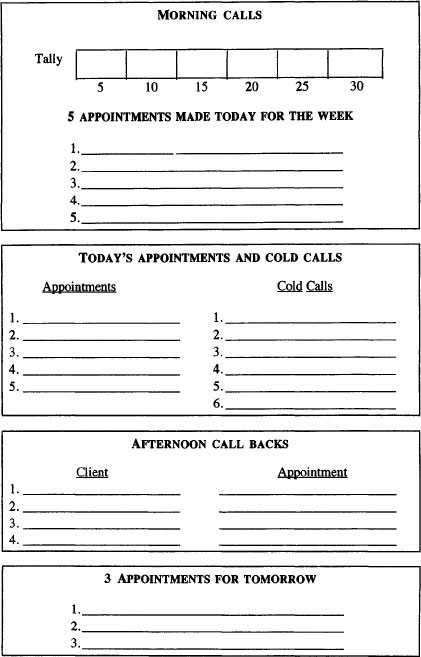

First and foremost, sales is a numbers game. A seller in the insurance business needs the names of 40 friends, friends of friends, coworkers, and relatives in order to get ten appointments. From ten appointments, an insurance salesperson is likely to get four sales. If that sounds like a lot of contact for little return, Tom Hopkins tells us that in all of selling, the average is closer to 10 to 1. Ten prospects yield one appointment. Ten appointments yield one sale.25

In baseball, a batter with 30 hits is not very good, unless that’s measured against 100 at-bats. Now you’ve got a .300 hitter! That’s how big league managers decide whom to send to bat against an opposing pitcher.

Direct marketing experts declare victory with a 2% response rate to a database mailing. They know response is the first step to conversion. The statistics help them know what to expect.

You can look at the percentages in one of two ways: as daunting because they tell you there’s lots of work to be done, or as an incentive because you know that once you’ve made the fourth call, your chances of closing are higher on the fifth. Like the baseball manager, you play the percentages.

All successful businesses use percentages to guide decision-making. Mutual funds lure your money with projected annual yield. You’d rather establish an account that yields 18% than one that pays 5%, right?

Percentages are an easy-to-grasp way of expressing ratios, where one number divided by another gives each a perspective. As Tom Hopkins explains in How to Master the Art of Selling, ratios that help you manage your selling business are serious stuff. Here are the ratios Hopkins urges sellers to track:

• Prospecting calls/hours spent prospecting

• Prospecting calls/appointment made

• Appointment/sales

• Hours worked/money earned

• Prospecting calls made last month/income this month

In Hopkins’ words: “If you’re not keeping track, you’re not steering your ship.” He looks at the selling process as a constant increase in the numbers in your ratios:

By making one call a day, you’re meeting about 30 people a month, so you’re closing about three sales a month. Now what’s going to happen if you decide to make two calls a day?

Your sales go up to six a month, and your income doubles.

Suppose you elevate your performance level again, and start making four calls a day?

Your sales go to 12 a month and your income doubles again. So if you were making $1,000 a month off three sales before, now you’re making $4,000 a month off 12 sales—and feeling very good about yourself.

Hopkins doesn’t ask us to double our effort immediately, only to add one call a day. He knows that every prospecting call does not yield a sale. Yet more calls equals more chances for closing. What Hopkins is telling us is that we must set our goals high enough to keep ourselves challenged, yet solidly rooted in reality so we can have a reasonable chance to achieve them. He’s also telling us to constantly raise the bar to achieve the next level of success.

Your sales director or sales manager sets goals for you each week, each month, and each quarter. For each of the steps in the selling cycle, be ready to set specific goals for yourself, too.

SALES IS A CONTACT SPORT

Make 12 phone calls a day, averaging 5 minutes each, and you spend about one hour per day talking to clients and prospects. Increase daily contacts to 20 or 25, and business will pick up fast.

Here are five practical steps to getting your contact rate up. They’re from Phil Broyles, a sales consultant to the financial industry:

1. Have a daily contact goal—keep score. Set a goal of 25 contacts per day, outgoing and incoming, both current clients and prospects. Use a daily worksheet or your calendar to keep score. Daily tabulation of calls completed will quickly help you develop the habit of meeting daily call goals.

2. Prepare a “call today” list. Before you leave each day, make a list of people to call the next day. Arrive at the office at least an hour before you start making calls. Use that time to decide which names you’ll call. To contact 25, you’ll need a list of at least 50. Your list should include people you didn’t reach on previous days, ongoing clients, and fresh prospects.

3. Use your calendar aggressively. Your calendar is a basic prospecting tool; with your daily call log added, it helps you create each day’s call list. In addition to appointments, you should schedule follow-up calls. As soon as you reach a prospect, note the next step on your calendar. Don’t wait until the end of the day.

4. Block out contact time. Schedule specific blocks of time, 60 to 90 minutes, that are reserved only for contacting prospects and clients. Then you can get on a roll and stay on it. In the same way, reserve afternoons or mornings that you will use only for in-person calls. Working with blocks of time lets you meet daily contact goals because you’re focused on accomplishing a specific task in a specific time frame.

5. Avoid distractions. Use the contact time you’ve scheduled for that purpose only. Have your calls held. Schedule other time for paperwork, presentations, and so forth. If you must attend to something while calling, use the time you’re on hold to scan, sign, or discard papers. In a normal day, you’ll save and use 20 to 30 minutes this way.

Broyles exhorts salespeople to take action. It’s characteristic of top producers to spend substantially more of their time talking with clients and prospects.

Another suggestion from Broyles: Follow the “10 before 10” rule. Contact at least ten people before 10 a.m. to ensure reaching your daily contact goal—and your monthly sales goals.

From Research magazine, April 1991.26

Where do potential customers come from? They start as prospects—potential advertisers. Just as the insurance seller starts with family, friends, co-workers, and others who might need insurance coverage, your first step is to cast the net to see who needs advertising.

First, every business needs to advertise. Not every business needs to advertise in electronic media, so your task is to develop lists of those who might and then to qualify them—see if they are, indeed, prospects for your medium.

If they already advertise on television, radio, cable, or interactive media, then they’re already prime prospects. They’ve been sold by somebody. Your job is to convert them to your specific service as part of their overall media mix. Start with the basics; for example:

• For sellers of local Web sites: Who’s already represented with banners on local city pages or click-throughs on regional home pages? Who’s on manufacturer sites of retail pages?

• For radio spot sellers: Who’s on the air at other stations?

• For TV time sellers: Who’s advertising on the other channels? On local cable? On radio?

Those are your first prospects, and they’re already predisposed to your message.

Now let’s look closer at competing media as prospecting tools.27

Newspapers still take the lion’s share of advertising from most markets. Newspapers not only tell you who’s in business, but also how much money they’re spending on advertising. The larger the ad, the more they spend. Big display ads are important qualifiers. When an advertiser can afford to buy one or more full pages in the newspaper, chances are there’s cash for other media, too.

The business section of the local paper is a perfect place to begin prospecting. What new deals have been cut? What land has been sold and to whom? Does it mean a new business is about to open?

National newspapers like The Wall Street Journal and USA Today carry regional and local news and advertising. Look especially in the Journal’s “Marketplace” section. Read the editorial copy and the advertising content. Read beyond the institutional ads and find the small displays about new openings, new assignments, and help wanted.

When reading your hometown paper, don’t stop reading at the business sections. Check real estate, food, entertainment, and sports sections, too, for advertisers who prefer to link themselves with a reader’s activities or specific lifestyle.

In the Sunday papers, look for coupons and coupon books (known as FSIs in newspaper language for “free-standing inserts”). Those four-color glossy coupons mean more to you than a few cents off at the grocery store. They could be a lead to a new promotional campaign or a new retailer. In other words, a prospect.

Local want ads are early indicators of pending openings. When a store begins to hire staff, the grand opening can’t be far behind. Look also for out-of-town companies soliciting personnel.

Suburban papers carry press releases from every new business in the community. You should subscribe to every weekly in your trading area. Don’t overlook the want ads.

Newspaper advertisers have long been considered targets for radio salespeople, because an advertiser can divert a portion of a newspaper schedule to radio and still see the ad in print.

Virtually everyone in America listens to the radio during the average week: 76.5% of persons aged 12 and over listen every day, 95.1 % listen every week. Radio’s ability to target demographically and geographically attracts businesses of all types.

It’s not as easy to go prospecting on radio as it is in the newspaper, because advertisers on radio are not so neatly compartmentalized. You can’t tear out a prospect’s advertisement to get the address, so you may have to do some research. By scanning the dial and making notes of all the commercials you hear, you can begin to create a list of potential clients who use the medium.

Local cable sellers target radio advertisers, arguing that commercials on cable cost about the same as radio and have the advantage of adding pictures to make the message more effective.

Cable reaches 68% of all U.S. homes and even more (81 %) of households with an annual income of $60,000 or more. Like radio, cable is considerably more targetable than over-the-air television because specific channels provide content that is geared to specific demographics, affinity, or lifestyle.

Because cable systems make their money on subscriber fees, not all local operators sell advertising. Most major markets have “interconnects” that sell advertising on several cable systems as one package. The Cable Advertising Bureau (CAB) lists 109 interconnects covering markets as large as New York and as small as Dothan, Alabama.

Even with interconnects, some markets cannot be covered with one buy. Baltimore, for example, requires several interconnects to reach both the city and suburban areas. Utica, New York, has one cable operator; its neighboring city, Rome, has yet another.

If the cable operator in your area does carry advertising, it’s another opportunity for prospecting. Area advertisers who buy cable might use inserts in CNN, TBS, or USA programming in place of local TV commercials because cable costs less.

Because of the low cost, cable has been called “discount television” by some national advertisers. So advertisers who use scrolling cable messages or banners may not be as lucrative as prospects, because they spend so little to get their exposure. The important point for you to consider is that they’ve shown a commitment to advertising in electronic media.

Over-the-air television reaches 98% of U.S. households, and the average viewer spends more than 7 hours a day with the TV turned on. The good news for sellers of TV advertising is that the medium reaches huge portions of the mass audience with a single exposure. Pictures, sound, and motion are all factors in television’s potential to attract attention for an advertiser.

The bad news is that TV shares are declining in the face of new competition from cable, new networks like Fox, UPN, and WB, and online usage that steals time once spent with TV. Production costs, too, create anxiety for TV advertisers. A typical 30-second spot for a national advertiser might cost more than $250,000 just to produce. Airtime increases that cost dramatically.

Advertisers on local television are good prospects for media salespeople who can demonstrate how to use the same dollars more efficiently, targeting consumers directly.

The phone company is kind to sellers. Not only do they give us our best tool for contact—the phone itself—but each year they issue an encyclopedia of local business, the Yellow Pages. Any business that has more than the standard listing of name, address, and telephone number pays for the privilege. That means when you see a display ad in the Yellow Pages, you’ve found a business willing to spend money on advertising.

To make things even easier, the Yellow Pages are organized by category, so you can identify immediately what a company does. In the Phoenix Metro Yellow Pages for 1997, there were 136 pages with the heading “automotive.” That included the dealers, the car washes, muffler shops, and wrecker services.

Stories abound about first-time sellers who are handed the Yellow Pages and told to sell something. I’ve been asked whether those stories are myth or reality. Believe me, they are reality. The Yellow Pages is called “the prospector’s Bible” for a reason.

I know salespeople who keep notebooks or recorders in their cars. When they see a sign announcing construction of a new business, they make a note. More importantly, they make a call, asking who’s building the new business and where the owner can be reached.

Any business that uses outdoor advertising is a prospect for electronic media. Billboards aren’t cheap, so even one outdoor board indicates a substantial commitment. The advantages of outdoor advertising include the ability to be seen by large numbers of consumers. The disadvantage is that those consumers are often traveling at high speeds, so the copy on a billboard must be brief to be effective. Electronic media sellers have the opportunity to demonstrate that their form of media can fill in the gaps in a cogent outdoor message.

Most companies have an online presence for public relations purposes. They want their customers to have access to information they cannot provide in brochures. By checking search engines like Yahoo! or In-foseek, you can discover categories of potential advertisers.

Look also for local and regional advertisers who sponsor banners on city guides like accessatlanta.com, sidewalk.com, bayinsider.com, and nbc-in.com, which creates local Web sites for broadcast TV stations affiliated with NBC.

Every industry has one or more trade publications. They offer a wealth of leads. They’re not only excellent for list-building, they also make you seem smarter to a retailer who knows you’ve been doing your homework on an industry other than your own. This is the customer focus that is so important in selling electronic media today.

Neighborhood “shopper” publications provide leads, especially for forms of media that target geographically—radio and cable, for example. Sellers of new interactive media create prospects from “local” advertisers who want to create a marketplace beyond the store on Main Street. Does it matter to the retailer where orders originate? An order and a valid credit card number are enough of a payoff in the new wired economy. A retailer shouldn’t care that customers come from another part of the globe via cyberspace.

While I’m on the subject of shoppers, don’t take the next trip to the supermarket for granted. After squeezing the produce and stocking up on prepared meals, scan the end-of-aisle displays and the “shelf talkers” (those little signs on the shelves). They may tell you about a selling opportunity, a new product, or a special promotion.

Stop at the grocery store bulletin board if there is one. Among the listings of babysitters and free kittens are often business cards, notices of hiring, and other possible leads.

That neon flyer placed under your windshield wiper at the mall may lead to a sale. Don’t throw it away until you pursue the potential. Could the business become an advertiser?

While I was waiting for a client to pick me up at a hotel in Midland, Texas, a man in the lobby handed me a flyer about job openings at the new Computer City store opening soon. No, I didn’t want to interview for a job, but I did want that flyer. I gave it to my client so one of his salespeople could use it as a lead.

A brochure or flyer at the cash register of a retailer you trade with might be your next appointment for a presentation.

Direct mail, the most targetable nonelectronic advertising medium, can zero in on geography, product affinity, previous purchases, potential interest, or lifestyle activities. The greatest advantage of the medium is that each consumer can be addressed as an individual.