Selling Television Advertising

The TV commercial is the most pervasive form of communication known, with a profound ability to influence both habit and thought.

TV commercials are so much a part of the American culture that they are often considered as entertaining as the programming during which they appear. A well-crafted national commercial often takes on an aura of its own, with stories and characters that viewers come to know and talk about in casual conversation.

Neil Postman estimates that “an American who has reached the age of 40 will have seen well over one million television commercials in his or her lifetime, and has close to another million to go before the first Social Security check arrives.”1

In Broadcast and Cable Selling, Warner and Buchman call America’s response to television “a passionate affair.” They speak in both reverent and rhapsodic tones about the pageantry, intimacy, and escapism that makes America love television for its “vast mirrored mosaic of ephemeral reflections of ourselves and our dreams.”2 That’s the kind of power that advertisers pay billions of dollars to tap.

The percentage of households with at least one TV set was at 98.3% in 1998, according to the Television Bureau of Advertising (TVB). (See Table 6-1) Of those households, 99.3% have color sets and 72.2% have two or more sets. The average number of sets is 2.32. The typical American household spent 7 hours and 17 minutes a day with the television on in 1995, down by only 5 minutes in 1997.

TVB documents the public’s perception of television as the most influential, authoritative, exciting, and believable advertising medium, based on a proprietary 1995 Bruskin-Goldring study.3 For example, think of commercials in the annual Super Bowl telecast: by November 1997, NBC had sold out advertising time during Super Bowl XXXII at an average rate of $1.3 million for 30 seconds. The previous year, the Fox broadcast of the game had sold out early and approached the same unit cost.

The final episode of Seinfeld in May 1998 was such an event that the cost of commercials set records for prime time—more than $2.0 million for 30 seconds. Advertising Age reported that buyers told NBC-TV salespeople during the 1997 upfront buying season that if 1997–1998 were to be the last year of Seinfeld, they wanted to advertise during the finale. That was almost a year before comedian Jerry Seinfeld announced the end of the show.4

Table 6.1 Television Households

In 1950 television penetration of U.S. households was only 9.0%. It didnit take long to grow, however, and within five years it was up to 64.5%. By 1965 it reached 92.6%, and has grown steadily to its current 98.3% level.

Year |

Total U.S. Households |

TV Households |

%HH with TV |

1950 |

43,000 |

3,880 |

9.0 |

1955 |

47,620 |

30,700 |

64.5 |

1960 |

52,500 |

45,750 |

87.1 |

1965 |

56,900 |

52,700 |

92.6 |

1970 |

61,410 |

58,500 |

95.3 |

1975 |

70,520 |

68,500 |

97.1 |

1980 |

77,900 |

76,300 |

97.9 |

1985 |

86,530 |

84,900 |

98.1 |

1990 |

93,760 |

92,100 |

98.2 |

1995 |

97,060 |

95,400 |

98.3 |

1996 |

97,540 |

95,900 |

98.3 |

1997 |

98,610 |

97,000 |

98.4 |

1998 |

99,680 |

98,000 |

98.3 |

Source: Nielsen Media Research, January each year.

The advantage of big-event programs like the Seinfeld finale or the annual Super Bowl broadcast is that they get big ratings across all demographic groups. Day-to-day selling at the network level is based on demos, that is, how many 18–49s or 25–54s you can deliver.

The conflict between demos and ratings is a key part of the narrative in Ken Auletta’s Three Blind Mice, a detailed look at the battle that the three original networks fought against declining share.5 Auletta followed each of the “old” networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) through the launch of the 1984–1985 season. The shows introduced then are long forgotten, but the pattern is the same: you need to sign new programs, re-sign previous programs, and convince the local affiliated stations that you’ve got hits on your hands that will make money for them. Then you must sell advertisers on the same idea.

The importance of demographics is widespread and well-known today, but that was not the case when Three Blind Mice was written. Auletta observed an NBC affiliates’ meeting in Burbank where NBC programming chief Warren Littlefield (later president of NBC’s entertainment division) announced, “The message loud and clear is demographics,” only to be followed by NBC research chief William Rubens, who said, “If you don’t have good ratings, good demos don’t matter. … It’s a mistake for us to think of unmass appeal.”

“This mini-debate,” Auletta writes, “was but one of many [the president of NBC Entertainment, Brandon] Tartikoff would adjudicate this week—between Sales, which cared about ratings but was preoccupied with urban-oriented demos, and Research, which cared about demos but first thought of ratings.”

YOUTH IS SERVED

The following table shows the median age of TV network viewers in the fourth quarter of 1996, and the first quarter of 1997, from BJK&E Media Group.

Network |

Median Age |

WB |

24.8 |

Fox |

32.3 |

UPN |

34.3 |

ABC |

40.7 |

NBC |

41.1 |

CBS |

51.5 |

How things have changed from the mid-1980s to the twenty-first century! What Rubens called “unmass appeal” is exactly what the networks now sell, especially against encroaching cable and direct satellite operations that can focus demographics for optimum advertiser impact. The “Big Three” became the “Big Four” when Fox entered the race. The Big Four then became the less-than-big six (or so) with the launch of UPN (United Paramount Network) and “The WB” (Warner Bros. Network). Paxson Communications’ Pax TV further complicates the count.

Fox led the way with targeted programming, showing the other networks how to make a living with 18–34 and 18–49 numbers, not the whole universe. Following suit were UPN and WB networks.

As Business Week put it, “Viewers are increasingly abandoning the Big Three for more interesting fare elsewhere. And where viewers go, so go advertisers—eventually.” While the audience eroded, television kept selling, increasing network revenues by just over 6% a year, according to TVB.

Business Week attributed that revenue increase to “snobbery surrounding the broadcast networks [that] still holds with advertisers, which continue to pay huge premiums to place ads on broadcast versus cable. Even with sharply reduced market share, the lure of reaching a huge audience in one shot still propelled the networks to $6 billion in advertising sales for the upcoming [1998] season.”6

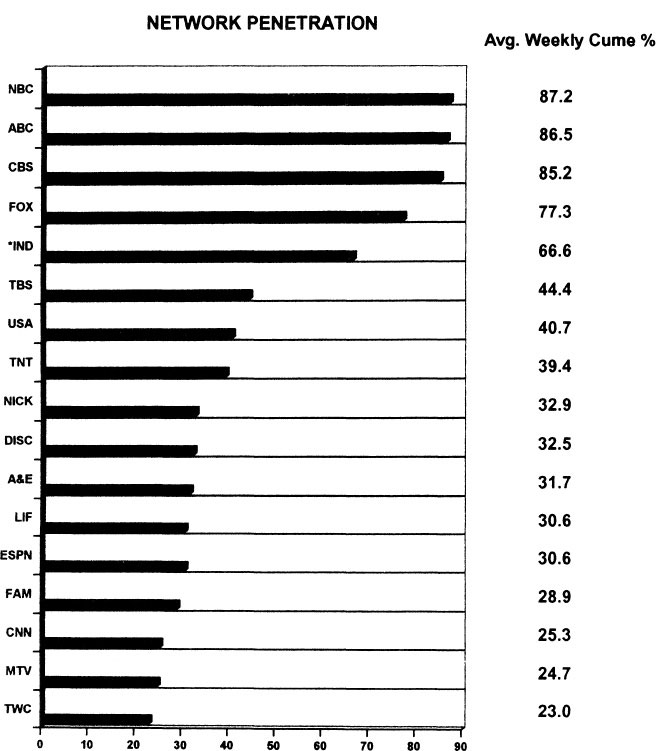

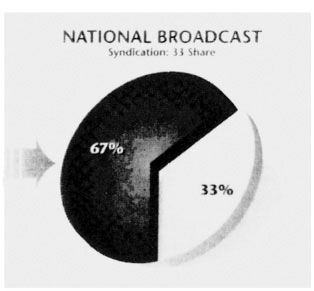

In 1997, basic cable edged out the major networks in shares during the summer rerun season. Basic pulled a combined 40 share in prime time versus a combined 39 share for the Big Three. TVB countered with information about television’s average weekly cume, which showed broadcast affiliates with percentages more than double the individual cable networks. See Figure 6–1.

TVB also created an advertising campaign called the “TV Boxscore” which compared broadcast and cable ratings on a monthly and cumulative basis. To target national advertisers, TVB placed the comparisons in the Ad Age Daily Fax and later turned it into full-color, full-page ads in Advertising Age. In an announcement coinciding with the TV Boxscore campaign, TVB said, “With highly selective use of Nielsen data, the cable industry has misled the advertising community into believing cable has a larger audience than broadcast. [TV Boxscore] clearly demonstrates how Nielsen numbers, computed fairly, shows the Broadcast ‘Airways’ consistently beating the Cable ‘Nets’ in overall ratings.”

The good news, of course, is that network television is still a viable—and valuable—medium for advertising. Like any other “mass medium,” television is slowly becoming demassified not only by cable, but also by new and emerging interactive forms of media that nip away at time formerly used for watching television.

New networks like the WB are helping television keep dollars in the family, so to speak. The WB’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer broke the $100,000 mark for 30-second spots in the 1997–1998 season. That was encouraging news for network managers. It meant ad dollars shifting away from the Big Four were staying in broadcast and not moving to cable.

But will there ever be a world without ABC, CBS, and NBC? “Don’t count on it,” says Digital Home Entertainment magazine.7 “For all the doom and gloom forecasts, the majors have proven surprisingly nimble through the years and there’s no reason to think they won’t adjust to the new terrain.” The magazine quoted CBS senior vice president Martin Franks, “The news of the networks’ demise is always premature.”

FIGURE 6-1 In 1997, cable edged out the traditional TV networks in summer ratings. That prompted TV sellers to look for good news. They found it in the average weekly cume of the traditional networks against cable networks.

Add Dawson’s Creek to Buffy the Vampire Slayer and you have the makings of a network, if the early performance of The WB is any indicator. Those two shows helped WB edge out UPN for the first 21 weeks of the 1998 TV season. “Edged” is the right word, too. WB’s victory party came because of a lead of only two-tenths of a rating point. UPN immediately announced a full week of programming for the 1998–1999 season and launched an updated version of the TV classic Love Boat, hoping to float its rating higher than WB’s.8

Executives of the two networks were constantly sparring. The two launched onto the TV scene at approximately the same time and were seen as bitter rivals for the “Number Five” network spot behind Fox. WB CEO Jamie Kellner was quoted (in Broadcasting & Cable) as saying that only five networks could survive.

In an effort toward branding and imaging, WB created the animated character Michigan J. Frog to act as both a logo and a host for the network. Mr. Frog, dressed in top hat and tails, introduces programming and even delivers commercial messages for sponsors. He also introduced the phrase, “Dubba-Dubba-Dubba-Bee” to reinforce the name of the network.

By comparing affiliate lists online, I noted that some WB affiliates were also UPN affiliates during the first few years of each network’s existence. I imagine that must have added to the rivalries in the executive offices.

Broadcasting & Cable’s annual survey of TV GMs showed in 1998 that WB was expected to be the long-term winner in the battle of the new networks.9 The survey asked the following questions:

1. WB and UPN have now been on since 1995. Do you believe that both of them will survive and expand in a manner similar to Fox?

Yes |

45% |

No |

48% |

2. Do you believe that at least one of them will survive and expand in a manner similar to Fox?

Yes |

80% |

No |

17% |

3. If you believe only one will survive, which one is more likely to survive?

UPN |

32.5% |

WB |

60.0% |

(In 1997, WB had a 52% to 48% lead over UPN.)

4. Bud Paxson plans to launch his new network, Pax Net, in August 1998. Do you believe it will succeed?

Yes |

30% |

No |

57% |

Here’s the network affiliation of each participant, so you can put the answers into perspective:

ABC |

23 |

CBS |

22 |

Fox |

17 |

NBC |

19 |

UPN |

8 |

WB |

2 |

Independent |

9 |

The study is conducted each year before the National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE) convention, with 100 TV GMs interviewed by Cahners Research.

“Can a TV network based on godliness and infomercials get good ratings?”

That question, posed by The Wall Street Journal, greeted the announcement of the proposed launch of Pax Net, the national family-oriented network created by Lowell “Bud” Paxson. Described by the Journal as “a minor player in TV for decades,” Paxson established the Home Shopping Network in the 1970s and operated a Christian cable channel that scrolled Bible verses on the screen while inspirational music played in the background.10

Paxson assembled a collection of UHF stations in large markets, all bought at low prices and operated on shoestring budgets. Revenues were generated from airing infomercials. When the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that cable systems were required to carry Paxson’s local stations, the seeds of the new Pax Net network were sown.

Paxson contracted with CBS to air Touched By An Angel and Promised Land in syndication. Rights for Touched were almost $1 million per episode, which raised eyebrows at other networks and in the financial community. (Wall Street was undecided on Paxson, at one time calling him “the toast of TV” and at other times questioning his financial prowess.) Paxson also bought rights to Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman and Dave’s World.

Pax Net’s infomercial roots were showing: the original schedule included The Mike Levey Show, featuring the founder and board chair of Positive Response Television (PRTV). As host for the infomercial program “Amazing Discoveries” (on Paxson’s stations and others), Levey was known in the industry as the “infomercial king.” His company found likely products for sale on televison and developed the selling and marketing concepts.

Paxson’s personal philosophy was underscored by an agreement with Focus on the Family Productions, headed by Christian radio personality Dr. James Dobson.

Ads announcing the launch of Pax Net read:

It’s about entertainment.

It’s about drama.

It’s about family.

It’s about life.

Get the spirit.

The 1998 launch was slowed by a lack of affiliates in some large markets. Paxson’s owned, operated, and affiliated stations combined reached only 68.2% of U.S. TV homes. To complete the coverage needed to qualify as a network, Paxson agreed to pay Tele-Communications, Inc. up to $27 million to carry Pax Net programming on its cable systems, calling the move “cheaper than buying stations.”11

The deal was similar to one that WB entered with both TCI and Warner Cable to fill in “white areas”—locations where consumers cannot receive Grade B television signals off the air. (There was debate in Congress in 1997 to determine just how to judge picture quality of “white areas.”) Broadcasting & Cable reported that Paxson agreed to a fee of $6 per subscriber for each cable system carrying his network on an analog tier to all subscribers and $2 for digital-tier carriage.

Weeks before the official launch of Pax Net, the company decided on a name change to “Pax TV” and retooled its logo and color scheme. The logo began as a white dove and cross against a sky blue background. At kickoff the new network called itself “the red, white, and blue Pax TV” both on the air and in its advertising.

The Benefits of Television as an Advertising Medium

Here’s a run-down of the environment for selling TV advertising:

1. Total advertising volume in the United States in 1997 was $187.529 billion, a 7% increase over 1996. (See Table 6-2)

2. All U.S. TV advertising (including cable) totaled $44,519 billion in 1997, up 10.5% from 1996. Television accounted for 23.8% of advertising dollars.

3. There were 1,204 commercial TV stations on the air at the beginning of 1998, 642 UHF stations, and 562 VHF stations.

4. Seven-hundred-fifty advertisers and 3,496 brands used network television in 1995 (the last year for which I could get figures).

5. The same year (1995), 1,893 advertisers and 12,002 brands used spot television: national commercials bought on local stations.

TABLE 6-2 Advertising Volume

Advertising volume in the United States reached $187.5 billion in 1997 with televison accounting for $44.5 billion, almost one quarter of the total, the largest share of any medium. Total ad volume has increased about 75% every 10 years since 1955, except for the 240% jump between 1975 and 1985.

In Millions

Year |

Total Volume |

TV Ad Volume |

% In TV |

1950 |

$5,700 |

$171 |

3.0 |

1955 |

9,150 |

1,035 |

11.3 |

1960 |

11,960 |

1,627 |

13.6 |

1965 |

15,250 |

2,515 |

16.5 |

1970 |

19,550 |

3,596 |

18.4 |

1975 |

27,900 |

5,263 |

18.9 |

1980 |

53,570 |

11,488 |

21.4 |

1985 |

94,900 |

21,287 |

22.4 |

1990 |

129,590 |

29,073 |

22.4 |

1995 |

162,930 |

37,828 |

23.2 |

1996 |

175,230 |

42,484 |

24.3 |

1997 |

187,529 |

44,519 |

23.8 |

Source: McCann-Erickson annual report on U.S. advertising volume assembled by Robert Coen.

The primary attraction of television as an advertising medium is its visual appeal, its ability to grab the audience’s attention with pictures and motion. Among advertising agency executives, television is often the first choice for product imaging and demonstration.

As chief creative officer for D’Arcy Masius Benton & Bowles (DMB&B) in Chicago, Gary Horton says, “There’s no question that television provides an advantage because the viewer is able to see the product.” At DMB&B, TV advertising comes first, followed by print, then radio.

Rick Berger, account supervisor at New York’s Jordan, McGrath, Case & Taylor, offers a specific example: “I worked in skin care for some time, where the proof is in the face. You have to show that the product works by showing a beautiful woman. This is true of other categories as well, where you have to visualize your point.”

For another example, Dick Halseth, media manager at Ford Motor Company, says the “vast majority” of Ford’s advertising dollars are spent on television and print. “An automobile tends to be an action-oriented product, as opposed to say a tube of toothpaste. You can really demonstrate the product very nicely in television. Then, when we use the magazine, it gives us the opportunity to reinforce what we’ve said on television and really hone in on an audience.”12

Berger says his agency’s decisions are influenced by the competitive environment: “If you have 12 competitors and they’re all doing television only, then obviously you’re missing something there. Now, while you don’t have to be where everybody else is, there is a school of thought that that’s probably a good place to be.”

Sellers should take note of that: “Your competitor’s on television” is a strong selling point. Let’s examine other strong points of advertising on television,

Visual: Television (both broadcast and cable) grabs the audience’s attention and creates appeal by combining full-color pictures, sound, and motion.

Lifestyle: Almost everyone born after 1948 grew up with television and sees it as part of life, spending an average of 8.5 hours a day with television, cable, or a VCR. Women spend the most time with television, averaging 4 hours and 33 minutes a day.

Mass Appeal: Television reaches huge mass audiences with a single exposure and allows delivery to multiple household members simultaneously.

Ubiquitous: Over-the-air television reaches virtually all households in the United States. (98.3%). Television reaches people who are not exposed to other media.

Intrusive: Television does not require the viewer to seek the advertising.

Reach: Television is capable of producing high levels of reach into generalized consumer segments, (e.g., children, teens, women, men, adults 18–49, etc.) and of combining reach with high-frequency levels.

Immediacy: Television provides immediate and simultaneous delivery of advertiser messages 24 hours a day.

Variety: There’s a broad array of program types, which allow ads to reach viewers while they’re in a specific state of mind, creating a positive environment for advertising messages.

Multilevel: Advertising time can be purchased nationally, regionally, or locally.

Agency Interest: The creative environment of TV production offers revenue opportunity for advertising agencies, production companies, and creative directors.

Entertainment Value: TV commercials are part of the culture and are often as entertaining as the programs that carry them.13

The Case Against Television Advertising

Video rules Americans’ leisure time, but over-the-air television does not. Shrinking shares at the major networks, channel surfing, and taping favorite programs for later viewing are all factors that complicate the sales of TV time.

In addition to audience erosion, there are some inherent downsides to TV advertising that as a seller you may hear from your prospective advertiser, including:

Clutter: The average network prime time hour contained eight minutes of commercials—as many as 24 commercial units—in 1993, and the numbers have increased since then. The average nonprime hour contained 13 minutes. Television’s cluttered environment can affect viewer retention of messages.

Nonmobile: Over 90% of TV viewing is done in the home, making it difficult to reach consumers directly at the point of purchase.

Poorly Targeted: Television is not as demographically selective as other forms of media and is not cost-efficient for reaching narrowly defined target groups.

Not Upscale: U.S. adults who earn more than $60,000 watch 26% less television than the average viewer.

Zipping, Zapping, and Surfing: Commercials can be easily avoided by changing channels or by fast-forwarding a VCR after recording a program.

Limited Avails: In spite of clutter, there is a limit to television’s inventory, which could preclude the purchase of specific programs.

Production Costs: In 1995, a typical 30-second national commercial cost more than $268,000 to produce.

Fragmentation: The average TV household could receive 43 channels of broadcast and cable in 1996, up from 11 in 1980. That adds to the declining share of the major networks and makes advertising choices more difficult.

The FCC defines a TV network as an entity providing more than 14 hours per week of prime time entertainment programming to interconnected affiliates on a regular basis.14 In addition, to qualify as a network, the programming must reach at least 75% of the nation’s TV households. Until 1990 Fox was a “syndicator,” not a “network,” even though it had a schedule of daily programs. Its national penetration was not enough to fit the “network” definition.

Salespeople at the network level are a small group, the best in the business. Because they deal with the largest dollars amounts, they face the most knowledgeable buyers in advertising. Since the buyers are usually at the top level of their agencies, they often demand to negotiate with people at the highest levels of network hierarchy.

Buyers stay up-to-date on the network marketplace on a daily basis. They know each network’s inventory, demographics, and rates. They also have to be savvy enough about programming to evaluate new pilots for their advertisers and to estimate the potential audience and demographic reach.

Often buyers and sellers move from one side of the table to the other. A network seller might have agency experience while an agency buyer might have a background in network selling. Because of this association, they know each other well and learn to trust each other. Trust is important in an environment that uses verbal orders that often total hundreds of millions of dollars.

“Network sales people must be skilled negotiators who have built up solid reputations,” say Warner and Buchman. “Their writing and research skills are not as important as their negotiating skills, because the television networks give their sales people in-depth sales support.” That means researchers are available to analyze ratings and demographics, as well as proposal writers to dress up presentations.

The sellers are responsible for offers and counteroffers, in other words, negotiation. As Warner and Buchman write: “Due to the limited amount of network inventory and the great demand for it, there is a constant and complicated juggling process that sales people go through to get advertisers the schedules they want.”

There are three markets for network television: the upfront market, the scatter market, and the open or opportunistic market.

“Upfront” is the annual purchase of TV commercial time well in advance of the telecast time, usually for a one-year schedule. It’s a relatively common practice among large advertisers for the purchase of prime time as well as other TV dayparts.

Ken Auletta calls upfront sales “a mating dance which begins sometime in March, when the networks invite the ad agency representatives out to Los Angeles for their first taste of the programs being developed for the new season.”15

Erwin Ephron is not so kind. He calls upfront sales “Dodge City media. Pull the trigger and count the bodies later.” Ephron is a partner in the New York agency Ephron, Papazian & Ephron, and is front and center as a buyer each year when the TV networks open what some agency people call a “feeding frenzy.”16

The first of the upfront markets involves selling children’s programming because of the limited amount of inventory. After children’s upfront comes prime time, followed by daytime, news, and late night.

TABLE 6.3 Top 25 Agencies by U.S. Network TV Billings

Source: Advertising Age.

Prime time gets the most attention, because big money is involved. In the 1996–1997 season, for instance, one ad agency spent over $1 billion in national network TV and syndication time, leading the industry. That was Tele-Vest, the media buying unit of the MacManus Group.

The following season the stakes became even higher. Tele-Vest was eclipsed by an alliance between agency giants J. Walter Thompson and Ogilvy & Mather Worldwide. That combination was responsible for $1.8 billion of time on network TV alone, says Advertising Age. The publication quoted Arnold Semsky, executive vice president of BBDO Worldwide: “Bigger is better. You get the best prices.” BBDO spent $941.4 million on network TV advertising in 1996, an increase of 25% over the previous year. Those figures get the attention of the networks. See Table 6-3.

The clout of big expenditures does no good, however, if the client’s product doesn’t get appropriate exposure. Irwin Gotlieb, president of Tele-Vest, says it’s more than a matter of money: “The bulk of the work is how you translate your client’s objectives to actual buys,” he told Advertising Age.

Gene DeWitt of New York’s DeWitt Media, a buying service, agrees, saying, “The guys who proclaim clout don’t really negotiate with the networks. They make ‘agency deals,’ and then the networks buy the programs for them. Then they can go back to their clients and say, ‘Yes, I got you a few ‘Seinfelds,’ but we had to take some other stuff.’”

The “other stuff” he refers to is less valuable programming. That means smaller audiences or demos that are not quite on target. But the lower prices help to balance the high cost of the premium shows. That balance comes with skillful negotiation on the part of the network sellers and sales management.

As I said before, the enormous sums involved in upfront buying prompt ad agencies to use their highest level people to negotiate. That means the network sellers are also selected from the highest level of management. As Warner and Buchman point out in Broadcast and Cable Selling, “Because these major network advertisers spend in the hundreds of millions of dollars, they prefer a high level, tightly controlled buying process to make sure nothing falls through the cracks—a 5% mistake could cost Procter & Gamble $20 million!”

Upfront buyers take the biggest risks, because they buy so far in advance. They also make the biggest commitments—usually a year’s budget in one buy. About 70% of a network’s prime time inventory and about 50% of the other dayparts is sold in the upfront market. In the days before the explosion of options for advertisers, the networks would sell as much as 90% of their inventory in the upfront market.

By pouring money into buying in the upfront market, an advertiser gambles that the early cost will be less than it would be when the season begins. The network guarantees that the advertiser will reach a specified minimum audience level.

Once upfront selling is finished, the scatter market begins. “Scatter” is the sales of the rest of network inventory not accounted for in upfront. Inventory is generally tight; therefore, rates go up. In the 1995–1996 selling season, scatter prices were 50% higher than upfront.

Advertisers usually buy about 60 days before the quarter in which they expect their commercials to run. Scatter buys are bought in shorter flights than upfront buys, and the buyer generally pays a premium rate compared to upfront’s negotiated rate structure. There are no audience guarantees in the scatter market, and the advertiser could end up paying an even higher price if a show succeeds.

In some years, the scatter market can save an advertiser money. For instance, Elise Lawless of Atlanta’s Fahlgren agency told Advertising Age that she had a client who wanted to make sports buys upfront in the 1995–1996 season. Since her client was on a calendar fiscal year, “we waited until January to make the buys.” Lawless’ client had not participated in upfront buying before, so “the networks really wanted our money,” she said. “Since the market had softened somewhat since the upfront, I know we got some better buys than some advertisers who made upfront deals last year.”

Scatter also refers to a commercial schedule that rotates the message through multiple dayparts. Most scatter plans are designed to meet an advertiser’s specific audience target, such as men 18–49, women 18–49.

The opportunistic market is the last-minute buying involving commercial inventory that has been created by programming changes or changes in an advertiser’s planning, like a move to another daypart.

Programs with controversial themes or plot lines make advertisers uneasy and anxious to disassociate themselves from that material. That also opens avails in the opportunistic market. Two examples from the 1997–1998 season that made advertisers skittish were ABC-TV’s Ellen, featuring an openly gay lead character, and the same network’s Nothing Sacred, about a Catholic priest who wanted his church to relate to contemporary needs instead of dogma.

The 30-second rate for Ellen that season was $180,000, much lower than the rates for the shows immediately before it on ABC: Spin City, $200,000; Dharma & Greg, $210,000; and Drew Carey, $275,000. Nothing Sacred had the least expensive 30-second rate among all the season’s network programs at $55,000.17

When advertisers avoid programs like these, the commercial positions can go vacant unless the network sells them at bargain rates to recoup the loss.

Most network orders, once placed, are non-cancelable. If an agency commits to an upfront buy and its marketing strategy changes or it faces financial problems, it’s the advertiser’s responsibility to sell off the unused time, not the network’s responsibility. Network sellers generally try to help, but they’re not required to do so.

The networks, on the other hand, cancel programs with no notice to the advertiser, but with the provision that commercials will run in another program that delivers the same audience profile.

In spite of audience erosion, time on network television is a valuable commodity, and the prices increase each year. Only the national networks can deliver a truly national audience; therefore, gross rating points (GRPs) become commodities. The demand for network GRPs has not diminished even in the face of declining shares. That creates a negotiating point for buyers and sellers, so the cost of network time is based on guarantees of price against audience, computed in cost per thousand (CPM).

As you remember from the discussion of research and ratings in Chapter 3, cost per thousand is calculated this way:

![]()

(The following numbers are way too low for network spot rates and audiences, but they’re easier to use as examples.) If a spot costs $200 and is aired on a program seen in 40,000 TV households, the household CPM is $5.00 (200 divided by 40,000 and multiplied by 1,000).

If the program reaches only 30,000 households, the CPM is $6.67. Let’s say that the network guaranteed the advertiser the $5.00 CPM in the first calculation. That means the network will have to run the spot in other programs to accumulate the additional audience required to bring the CPM down to the promised level.

For example, a friend of mine who runs a regional sports network cautioned a small TV station about running his programming. The station’s audience was so limited that the commercials would have to run in all the station’s programming in order to satisfy the audience guarantees that the station had made. My friend feared that the TV station would have no time to sell its own commercials because it would be running the sports network’s inventory 24 hours a day in order to satisfy the guarantees.

Delivering enough households (or persons) to make the buys efficient is a product of two things: the popularity of the network’s programming and the number of network affiliates that carry the program. When an affiliate carries a network program, it is said to “clear” the program, hence the term “clearance.”

TABLE 6-4 Television Dayparts in 1997

Daypart |

Households Viewing Minutes |

Cost per 30 CPM |

CPM |

Daytime |

3,830,000 |

$14,800 |

$3.85 |

Early evening |

8,390,000 |

46,600 |

5.55 |

Nighttime |

9,530,000 |

106,500 |

11.18 |

Late evening |

3,270,000 |

24,500 |

7.48 |

Household viewing is expressed as “numbers viewing in the average minute of the average program.”

Advertisers who buy network time rely on clearances that deliver a huge combined audience of all the network’s affiliated stations. The stations, however, are not required to clear the programs. If local management feels a program does not suit the local marketplace, they may make a local substitution, a preemption. That decreases the potential audience for a program and reduces the advertiser’s reach, and therefore the cost.

The prices for an average 30-second commercial on network television in prime time have generally risen over the years. For example, the cost in the 1965 season was $19,700, or $1.98 per 1000 homes. In 1979, the average cost was above $50,000 for the first time. By 1984, it had risen to its all-time high, $107,500. Averages in 1996 and 1997 were $101,400 and $106,500, respectively. The CPM rose to $11.18 in 1997. Table 6-4 shows how network television looked in 1997 in cost per thousand.

The same year that Seinfeld broke records for the price of 30-second commercials, the show also broke records for single-episode pricing in syndication. Columbia TriStar Television sold Seinfeld in the New York market for $300,000 per episode. WNYW, New York’s Fox-owned and operated station, paid the price in 1998 for programming that it could not air until spring 2001. The station paid record prices knowing that its competitor, WPIX, would broadcast Seinfeld episodes in the years before 2001. WPIX had bought the program for its first run in off-network syndication. WNYW’s purchase was for the second run.

“By the time Seinfeld goes through a third, fourth, and possibly fifth run in syndication (a la I Love Lucy) it will likely wind up in the $2 billion range,” wrote Broadcasting & Cable after the 1998 convention of the National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE), where syndicated shows are usually sold.

The $2 billion figure represents the combined license prices for all stations buying Seinfeld over the life of the series in syndication. Given the program’s strong showing as a first-run sitcom on NBC and the demand for commercial time in the program’s final episode, syndicators and station executives alike were confident about its future. “I don’t think there is a station that doesn’t want Seinfeld, said Michael Eigner, the general manager of WPIX.19

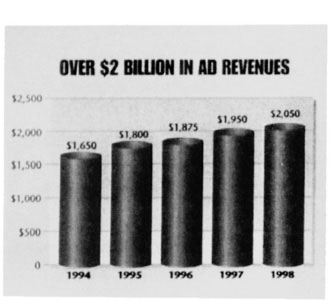

Before the Seinfeld pricing, the Advertiser Syndicated Television Association (ASTA) valued its industry at $4 billion, including sales per episode to stations and cable networks plus advertising sales. Half of syndication revenues come from advertising, which is just under $2.1 billion with expectations of continued increases. (See Figure 6–2.) The potential for additional revenues caused syndicators to change the structure and the name of their organization. In 1998, ASTA became SNTA, the Syndicated Network Television Association.

FIGURE 6-2 Half of television syndication revenues come from advertising (the other half come from selling rights to programs). Advertising revenues are on the rise because of “broadcastsized ratings,” according to the SNTA.

Syndication is the sale of programs on a station-by-station, market-by-market basis. Syndicated programs are those not produced by the local station or sent to the station via one of the networks (although some syndicated programs may have originated as network fare). Syndicated programs are sold to the stations on a market-exclusive basis for a certain length of time and for a certain number of broadcasts per episode. Once the syndicator has cleared a group of stations to carry its program, it sells advertising time in the program to national advertisers.20

Advertisers use syndication in combination with network buys to maximize their use of broadcast television against the declining shares of the networks. The biggest customers for syndication are the nation’s big spenders in all electronic media: Procter & Gamble, General Motors, and Kraft General Foods.

“Syndication’s use is on the rise because of what it delivers to advertisers,” says Jon Barovick of Tribune Entertainment. “We’ve proven time and time again that we can develop fantastic programming that rivals what the networks have—and hands-down what cable has—in terms of original programming, U.S. coverage, daypart appeal, and demographic delivery.”

Both the increase in the number of cable outlets and the opening of lucrative time periods in broadcast television have contributed to the boom in syndication. In 1996, the Federal Communications Commission eliminated the prime time access rule, which had prevented ABC-, CBS-, and NBC-owned or -affiliated stations from running off-network syndication in prime access (the period immediately before prime time, 7 p.m. to 8 p.m. Eastern).

In addition, that same year saw the end of financial interest and syndication rules, known in the industry as “fin/syn.” Fin/syn forbade a TV network from owning or syndicating its own programming. The end of those rules meant that a network could now enter the syndication market. The first to capitalize on this situation was the Walt Disney Company, which bought Cap Cities/ABC (owner of the ABC-TV network) without having to divest its profitable syndication division.

The result of the rules changes was larger entities in both production and distribution of syndication. Some had feared that first-run programming would be pushed out of prime access in favor of off-network programming, but that did not happen, owing to the strength of first-run programs like Wheel of Fortune, Entertainment Tonight, and Access Hollywood.

Programs like Seinfeld, Home Improvement, and The X-Files, which originally ran as network series, are called “off-network syndication.” Syndication also includes original programs like Tribune’s Geraldo Rivera Show, Universal’s Xena: Warrior Princess, and Warner Bros.’ The Rosie O’Donnell Show, which are “first-run syndication.” (See Figure 6–3.)

TABLE 6.5

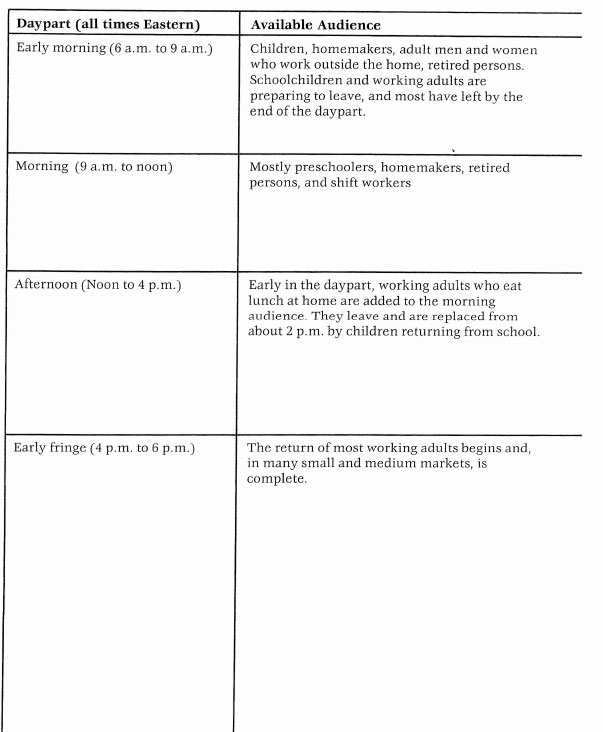

Whether you sell on a national or a local level, you need to be familiar with standard TV dayparts. Table 6–5 lists each daypart and outlines the available audience and the typical programming strategy based on that daypart.18

FIGURE 6-3 Syndication once meant reruns. Now 88% of TV syndication is first-run programming like The Rosie O’Donnell Show and Entertainment Tbnight. From 1998 Guide to Advertiser Supported Syndication. Used with permission.

Syndication is done on a “barter” basis. The local TV station agrees to run commercials sold by the syndicator within the program in exchange for the program itself. The more popular the program, the more likely the station will have to pay cash for each episode, as well as provide the syndicator with commercial positions, an arrangement called “cash-plus.” The local station generally gets commercial time within the program, too. Whether pure barter or cash-plus, the term generally used is “barter syndication.”

Warner Bros. Domestic Television’s Jenny Jones, The Rosie O’Donnell Show, and The People’s Court are examples of cash-plus syndication. The distribution company takes 3![]() minutes of commercial time for its national advertisers, and the local station gets 10

minutes of commercial time for its national advertisers, and the local station gets 10![]() minutes to sell to local sponsors.

minutes to sell to local sponsors.

TV sales trainer Martin Antonelli calls barter syndication “one of the fastest-growing areas of the TV industry. It has created a marketplace for original programming as TV stations and cable networks seek to fill openings in their program schedules. Typically, a syndicated program appears in at least 70% of the country,” Antonelli says, making it attractive to national advertisers.21

The Rosie O’Donnell Show claimed 99% coverage of Nielsen households in the 1997–1998 season, and the science fiction series Babylon 5 claimed 95%.

A special report in both Advertising Age and Electronic Media described the impact of syndication:

Broadcast television has long been the primary marketing tool of major national advertisers, because it can deliver large audiences, national coverage and broad reach. But fragmentation has been eroding the broadcast networks’ ability to deliver these key benefits.

But “broadcast” doesn’t just mean “network.” Advertiser-supported syndication is the other part of the national broadcast medium—a very major part, comprising about a third of the national broadcast audience, and dominating some key dayparts.

The daypart in which syndication has been most successful is daytime, driven by the proliferation of syndicated talk and entertainment shows. Syndicated programming generally reaches women 18–49 and 25–54 in daytime, and 66% of the audience is reached over a 4-week period.

National advertisers pay hefty unit prices for 30-second spots in syndication. Through 1997, Home Improvement was the most expensive of the programs offered in syndication, with a 30-second rate of $105,000. The X-Files was second and Seinfeld was third. Table 6-6 shows the top 25 prices for syndicated programming that year. Note that six of the top ten programs are off-network.

Syndicated TV buyers told Advertising Age that the prices paid in 1997 were somewhat below 1996 levels because of ratings slippage. Most talk shows, for example, dropped “dramatically” (Advertising Age’s word) in ratings and in revenues. Not one of the major advertising agencies surveyed for a special report in Advertising Age acknowledged buying the Jerry Springer Show or the Maury Povich Show, and only one said it bought Jenny Jones at an estimated average unit rate of $17,000 per 30-second spot. The exceptions to the talk show trend were The Oprah Winfrey Show and The Rosie O’Donnell Show.

Like the networks in upfront selling, the syndicators make audience delivery guarantees to their advertisers. If a program delivers less than the projected rating, the syndicator adjusts the rate with cash back to the advertiser. The prices in Table 6-6 reflect that adjustment.

Media buyers claim that syndication historically has the biggest “spread,” or gap, between audience estimates forecast by buyers and those projected by the sellers.

Syndication finds a warm welcome at national cable networks as well as at broadcast TV stations. TBS paid $100 million for the rights to Seinfeld for its WTBS superstation. TNT agreed to pay $1.2 million per episode for ER in syndication. Warner Bros. sold the first-run rights to the hour-long emergency room drama to TNT for Monday through Friday programming and to local broadcast TV stations for weekend programming.

FIGURE 6-4 Syndication has 13% of total viewing, according to SNTA, and a third of national broadcast, as shown in this pie chart. In early fringe, syndication takes 77% of the pie. Courtesy SNTA. Used with permission.

Why did a syndicated show command such a high price from cable? NBC-TV established value for ER in the wake of the end of Seinfeld. In order to keep its Thursday night lineup as stable as possible, NBC agreed to an unprecedented $13 million dollars per episode for the first run of ER. In turn, the network charged advertisers $565,000 per 30-second commercial during the 1998–1999 season, the highest price ever charged for airing in a prime time program. In addition, there were very few dramas available. Supply and demand drove prices up. Twentieth Television licensed its two top off-network dramas to the FX network. The X-Files and NYPD Blue were sold to FX for $600,000 and $400,000 respectively. The result was a doubling of its 18–49 ratings for the new network.

SPECIAL FX

Like the networks, syndicators vie for the attention of national advertisers with costly and elaborate presentations.

Rysher Entertainment, the company that syndicates the very successful Entertainment Tonight magazine-style TV show, rolled out a new series called FX about a movie special effects expert teamed with a “tough-talking, head-banging, street-hustling” detective. The presentation materials themselves had “special effects” built in:

• Open the spiral-bound booklet to the picture of special effects man Rollie Tyler (actor Cameron Daddo), and there’s a magnifying glass to distort his face.

• Open to the page just after the detective with the hyperbolic description, and there’s a mirror to turn a backwards “FX” title so it can be read properly (or to distort the advertising buyer’s face).

• And speaking of distorted faces, peel off a plastic overlay and what looks like an elderly, bald, and bristle-bearded street person turns into the lead character’s winsome and hazel-eyed girlfriend (actress Lucinda Scott).

• The last effect in the booklet is a page of temperature-sensitive paper. Place your palm in the center, and you’ve made a hand print to cover the pouting face of Rollie Tyler’s assistant and office manager (actress Christina Cox).

Cable also captured the rights to Party of Five (Lifetime), Chicago Hope (Lifetime), Walker, Texas Ranger (USA), and New York Undercover (USA).

Doug McCormick, president of Lifetime, told Broadcasting & Cable that the reason cable became a major player in off-network syndication was the lack of “real estate” (that is to say, air time) on broadcast stations:

Years ago you had Kojak, Cannon, and all those shows in early fringe on stations, but that was pre-“Rosie,” pre-“Oprah,” pre-“Jerry Springer.” So there’s a crowding out in the syndication marketplace, and cable has become the best outlet. What we have done is make it impossible or very difficult for syndicated hours to be profitable on stations.22

Except for the largest TV markets like New York and Los Angeles, local stations cannot pay $500,000 for individual episodes of programs and expect to recoup that money from advertisers.

Advertisers on Syndicated Television

Food and food products were the leading advertising category in syndicated television in the mid-1990s. The total expenditures for food commercials in 1997 was $368.5 million, which is $70 million ahead of that year’s number-two category, toiletries and toilet goods. The grand total for advertising on syndicated television in 1997 was $2,515 billion. The rankings were as follows:

TABLE 6-6 Top 25 Syndicated Shows Ranked By Ad Price

This table shows the cost of a 30-second commercial among the top barter syndicatd TV series.

TV Show |

1997–1998 |

Home Improvement |

$105,000 |

X-Files |

92,000 |

Seinfeld |

81,000 |

Entertainment Tonight |

72,000 |

Wheel of Fortune |

65,000 |

The Simpsons |

65,000 |

Frasier |

62,000 |

Star Trek: Deep Space 9 |

58,000 |

Mad About You |

58,000 |

Jeopardy! |

57,000 |

The Oprah Winfrey Show |

52,000 |

Grace Under Fire |

47,000 |

Xena |

40,000 |

Hercules |

40,000 |

Rosie O’Donnell Show |

37,000 |

Extra |

36,000 |

Living Single |

30,000 |

Access Hollywood |

29,000 |

NYPD Blue |

29,000 |

Martin |

29,000 |

Pensacola |

26,000 |

Inside Edition |

26,000 |

Earth: Final Conflict |

25,000 |

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids |

24,000 |

Source: 1998 Advertising Age/Electronic Media survey of national barter syndication buyers, based on Nielsen Media Research’s 50 top-rated shows through November 11, 1997. Unit rates are based on average price paid for a 30-second unit, after audience adjustments are factored in for cash refunds.

FIGURE 6-5 This ad from Warner Bros. Domestic Television shows one company’s diversity. Multiply that by 14 member companies of SNTA and you find lots of syndicated programming available.

2. Toiletries and toilet goods

3. Proprietary medicines

4. Confectionery, snacks, and soft drinks

5. Restaurants and drive-ins

6. Automotive

7. Sporting goods and toys

8. Movies

9. Consumer services, including telephone companies

10. Household equipment and supplies

11. Soaps, cleaners, and polishes

12. Home electronics

13. Personal services

14. Department stores

15. Apparel, footwear, and accessories

16. Pet foods and supplies

17. Jewelry, optical goods, and cameras

18. Publishing and media

19. Computers and office equipment

20. Loan and mortgage companies

21. Anti-smoking materials

22. Shoe stores

23. Insurance

24. Leisure time activities and services

25. Beer and wine

The biggest gainers in the list were loan and mortgage companies, up 255% from 1996 to 1997, and jewelry, optical goods, and cameras, up 113%. Sporting goods and toys were off by 29%.23

The top five advertisers in syndication were Procter & Gamble, General Motors, Johnson & Johnson, Diageo PLC, and Unilever.

A family on vacation demonstrates the ways each member uses their credit card. Not just any card, the Discover Card. On its tenth anniversary, Discover discovered the infomercial. It was the first credit card company to do so.24

Discover’s entry into the infomercial field in 1996 demonstrated that long-form commercials were capable of selling more than exercise machines, contour pillows, and food choppers that slice and dice. The company chose the “storymercial” format, dramatizing the family’s vacation in a playlet called “Give Me Some Credit.”

In addition to the storymercial, infomercial formats include the “programercial,” almost a documentary approach, but dramatized for the production, not collected from existing sources as a documentary would be. The Sled Dogs Company of Minneapolis used the programercial to demonstrate snow skates, which are a cross between inline skates and snow board boots. Their half hour followed a skating champion as he tried to escape an angry Rottweiler. Footage was edited MTV-style with spoofs of the Sled Dogs board of directors trying to decide how to market the new product.

Don’t confuse the programercial with the “documercial,” which is produced just like a documentary. For example, behind-the-scenes footage of the rock band the Grateful Dead on tour was used in an infomercial called “The Long Strange Trip Continues,” which sold Dead videos, CDs, T-shirts, and screen savers. The seemingly laid-back Dead were one of the most aggressive database marketing organizations and used the infomercial to add names to their database.

Next, there’s the “brandmercial,” designed to deepen the image of a national brand. For example, Lexus introduced the 1997 LS 400 luxury car with a brandmercial titled, “Lexus Presents: Driven to Perfection.”25

(The suffix, “-mercial,” gets out of hand: Cruise Holidays International of San Diego called its scenes of happy vacationers a “cruise-mercial,” which is not an official designation).

The original infomercial format was the “talk show,” which for some reason escaped that “mercial” suffix. As its name indicates, the talk show walks a fine line between a typical TV talk show and a commercial. There’s also an infomercial format called “demonstration,” for obvious reasons. Sometimes, the demonstration includes an audience in order to simulate a typical talk show format.

Peter Spiegel, president of Kent & Spiegel Direct in Culver City, California, suggests letting the product decide the format: “Housewares are normally done in a demonstration format. Vanity/sex are generally done in talk-show or documentary styles, but, again, if it is an image piece, it could be done as a storymercial. Financial opportunities, personal improvement, and entertainment products are generally documentaries.”26

Most of the early infomercials were seen late at night and featured books, seminars, and tapes from real estate consultants, and gadgets like juicers, vegetable slicers, and paint applicators. In his book, The Age of Multimedia and Turbonews, Jim Willis addresses the infomercial’s nocturnal placement:

Possibly the secret of these newly formatted infomercials is that they combine elements of popular talk shows featuring well-known faces in beautiful settings and direct-market home television shopping, where ordering products and services of fered is as easy as picking up the phone. Like other types of late-night media programming, such as radio call-in shows, these social gabfests greet insomniacs and other night people with friendly faces and urge the viewer to join in the fun by using the telephone.27

The infomercial grew up, so to speak, when major advertisers took advantage of TV’s audience and their willingness to respond immediately. In addition to Discover and Lexus, Hoover Vacuum Cleaners, Phillips-Magnavox, Quaker State Motor Oil, MGM Home Entertainment, Nissan Motors, Apple Computer, and many others produced and aired long-form commercials.

In the 1996 presidential campaign, candidate Ross Perot raised the visibility of the half-hour infomercial format by airing programs in prime time on national networks.

Timothy Hawthorne, known in the field as “The Father of the Modern Infomercial,” founded Hawthorne Communications in Fairfield, Iowa, in 1986. Since then the name has changed to “hawthorne direct”, and revenues have risen to $50 million a year. Here’s Hawthorne’s definition of “infomercial”:

In essence, an infomercial, or long-form television commercial, is a 28![]() -minute program designed to motivate viewers to request more product information, place an immediate order, or purchase the product at a retail outlet. The program informs, entertains, builds credibility, explains product benefits and addresses anticipated objections. Spaced within the program are several ads running 2 or 3 minutes that further explain the product, demonstrate the benefits, present the offer, and encourage viewers to call a toll-free number.28

-minute program designed to motivate viewers to request more product information, place an immediate order, or purchase the product at a retail outlet. The program informs, entertains, builds credibility, explains product benefits and addresses anticipated objections. Spaced within the program are several ads running 2 or 3 minutes that further explain the product, demonstrate the benefits, present the offer, and encourage viewers to call a toll-free number.28

There are also short-form infomercials, elongated commercials that usually run 2 minutes in length, although some are 60s and 90s. They are called “direct response television” (DRTV) because they ask the viewer to call a toll-free number and place an order.

Hawthorne says DRTV is “ideal for products generally under $30 that are easily and quickly understood such as CDs, videos, Ginsu knives. … Infomercial products, usually above $30, are those that require more time to fully explain the product’s features and benefits or to create an emotional bond.” An exception to the $30 rule was a DRTV campaign from Xerox Corporation in 1995 to introduce a line of digital copiers. (See Figure 6–6.)

In the early 1990s, infomercials accounted for $750 million in sales, according to Direct Marketing. By 1997, revenues were at $1.56 billion, according to Hawthorne, up from the $1.4 billion in 1996 and $1.1 billion in 1995, as reported by NIMA International, the trade association of infomercial producers.

“Infomercials give the buying public what it wants in an entertaining and interesting form that sells,” Hawthorne says. However, he does not advocate replacing spot buys or print ads with infomercials:

In our experience the media mix works well together, complementing one another. Infomercials bolster consumer awareness of your product and share the product story with millions of additional prospects at a cost per lead or cost per order that usually matches or beats other direct marketing channels such as direct mail or print ads.

Myrna Gardner, president of Hudson Street Partners, the New York–based infomercial unit of Saatchi & Saatchi advertising, produced the Lexus “brandmercial” as well as long-form commercials for Fidelity Investments, Florida Citrus, and Toyota.29 She takes a practical approach to infomercials: “Advertisers are searching for the best way to deliver information about their products to consumers. If we want consumers to find out about our products, we have to present the information in an entertaining manner.”

Jim Willis underscores Gardner’s comments: “One way to avoid the viewer’s predisposition to escape commercials is to make those commercials as interesting as other programming.”

The more sophisticated the programming in the infomercial, the less relegated the shows are to late nights and odd hours. An infomercial for the New England Patriots football team broadcast on Boston’s WCVB, the ABC-TV affiliate, and other New England TV stations earned a 5.3 rating (better than basketball’s Celtics and hockey’s Bruins combined on that same day). The “Patriots Insider” infomercial highlighted Patriot and Pro Bowl star David Megget, beginning with him waking early in the morning and following him through a day. It also featured former Patriot Andre Tippet, who offered “Tippet’s Tips for Kids.” The athletes were portrayed as role models. Interspersed throughout the program were “great moments in Patriots’ history.” The remainder of the program sold NFL merchandise.

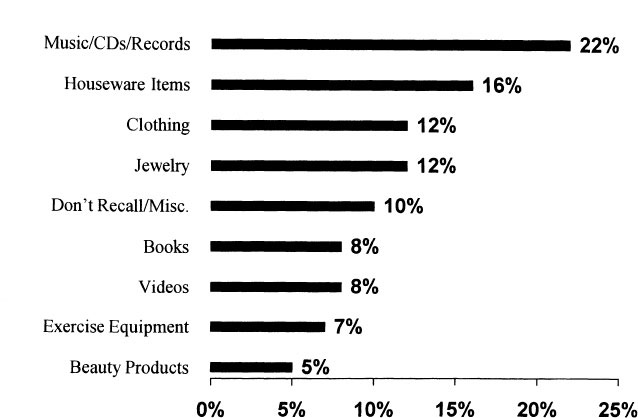

FIGURE 6-6 The father of the modern infomercial, Timothy H. Hawthorne says the infomercial is unparalleled in its ability to generate consumer demand. Here’s what sells in infomercials. The data was collected from Direct Marketing, January 1998.

Rising media costs for infomercial placement created a new type of network—the infomercial network.

• Before Paxson Communications launched Pax TV, the company called its collection of TV stations “in TV, The Network of Infomercials.” It was the largest of the infomercial broadcasters, airing infomercials for 15 hours on the average day and covering 59% of U.S. TV households.

• Access Television Network (ATN) fed programming on two unduplicated channels to cable systems covering about 37 million homes. Cable operators were able to plug ATN feeds into open time slots on networks or on public access channels.

• Guthy-Renker, a producer of infomercials, also owns GRTV Network, which buys unused time on cable systems owned by Tele-Communications, Inc., Time-Warner, and MediaOne. GRTV is also available on DirecTV satellite channels. Their ad in Broadcasting & Cable was headlined “Got Money?” The answer: “We do! We’ll help you identify the underutilized airtime in your lineup and turn it into cash … today!”

Broadcasting & Cable’s 1998 survey of TV GMs showed that 92% of TV stations carried infomercials. Survey questions included the following:

1. Do you run infomercials of at least a half-hour length on your station?

Yes |

92% |

No |

8% |

2. Yes respondents only: How much of your total revenue do they account for?

5% or less |

79.3% |

6% to 10% |

12.0% |

Over 15% |

3.3% |

3. All respondents: Are you projecting more, less, or about the same revenue from infomercials in 1998?

More |

13% |

About the same |

57.6% |

Less |

28.3% |

The study is conducted each year in time to be released at the National Association of Television Program Executives (NATPE) convention in January. One hundred TV GMs are interviewed by Cahners Research.

• Product Information Network (PIN), owned by Jones Intercable, Cox Cable, and Adelphia Communications, covers 10.2 million homes and operates 24 hours a day.

“As more cable channels appear, the need for innovative programming increases,” says Andrew Miller, who hopes his company, MarkeTVision Direct, will be asked to fill it. “The key is to provide these channels with a program that looks like good network television and also incorporates the proper elements which make the consumer respond and buy the products being offered.”

Miller’s Boston-based operation produced “Patriots’ Insider” and the Grateful Dead’s “The Long Strange Trip Continues.” Infomercials from MarkeTVision have a twist: they sell commercial time in the program as well as selling products directly to the viewer.30 Miller calls it “revenue enhanced programming” (REP).

When General Cinema opened two theaters in the Chicago area, Miller produced an infomercial (i.e., a REP) to tell the story. Traditional movie marketing focuses on the stars and the action, not on the specific theater, so General Cinema was “breaking the mold,” in Miller’s words. The infomercial featured a tour through the state-of-the-art theater with behind-the-scenes looks at everything from the acoustics to the projection booth. Along with direct response pitches for gift certificates and ticket coupon books were commercials for Pepsi Cola products and M&M/Mars candies. “The direct response spots afford General Cinemas a revenue stream from the paid program and the placement of commercials from their vendors helps defray the production costs,” Miller says. “By using direct response television and REP, a company can promote both its name and specific products and brands. As media time and general advertising become more expensive, REP becomes a viable and effective way of marketing that can actually bring a return on an investment.”

Production costs for MarkeTVision’s Grateful Dead program were paid by Maxell Corporation of America. Maxell’s Scott Fain told Advertising Age that his company had a “long-standing relationship with the Grateful Dead and we have a very loyal following among their fans. It makes all the sense in the world to be a sponsor of programming that revolves around the Grateful Dead and reaches the band’s fans.”

I didn’t realize that television was already learning from radio until I got deep into the interviews for this book. Honestly, I anticipated a lot of questions. Specifically, “Why was a radio guy assigned to this project?”

Like a good seller, I was ready with information about myself and my background to answer any objections I encountered. Selling is selling, I was ready to say, whether it’s selling radio time, cable insertions, banners on Web pages, or products and services. (There’s more about neutralizing objections in Chapter 2.)

INFOMERCIAL FAQS

Peter Spiegel is president of Kent & Spiegel Direct in Culver City, California. Here are some questions his potential clients ask him about infomercials.

1. How much does it cost to produce an infomercial?

There is a very broad range here—$75,000 to $1 million—however, most fall in the $150,000 to $250,000 category. A typical demonstration show tends to fall in the lowest range of the spectrum. A typical talk-type show might cost $250,000, while an elaborate storymercial with actors and a story line would probably fall in the upper range.

Guard against budget overruns. You don’t want to find that you have spent all your money on production and have nothing left for media or inventory. Location shoots, high-priced talent, special effects, reshoots, and overtime can all drive a budget out of control. The best advice is not to let your ego rule your pocketbook.

2. How much does it cost to air an infomercial?

Media is generally broken into two categories: the test and the rollout. Media tests run anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000. We usually get our feet wet with about $10,000 and start doubling it every week. You pretty much know what you have after you spend $50,000. A decent test should include a mix of broadcast and national cable.

The rollout is another story. Our bare minimum for a successful infomercial is $50,000 per week—generally we spend between $100,000 and $500,000 per week. … If we were to use baseball as an analogy, $100,000 is a single while $500,000 is a home run.

3. Do I need a celebrity?

When you hire a celebrity, you are entering the alien world of the entertainment industry. As I like to say, enter at your own risk. It is a world inhabited by agents, managers, and lawyers. Need I say more?

Once again, look at the categories:

• Housewares never require a celebrity.

• Financial opportunities and personal development depend on the charisma of the spokesperson and the credibility of the testimonials and also do not require a celebrity.

• Vanity/sex-appeal products may benefit from celebrities whose lives depend on vanity or sex appeal.

• Entertainment products generally feature celebrity-driven products and therefore don’t necessarily require the additional panache of a celebrity host.

©1996 Direct Marketing Association

As I pursued interviews of expert sellers, I was surprised that those questions in fact did not arise. I came to realize how lucky I was to approach the new environment of electronic media from a radio perspective.

Cable salespeople reminded me they had been emulating radio for quite a while by selling tight demographic niches or specific geographical areas. Sellers in broadcast television had recently discovered the need to change their approach, moving from transactional selling to creative, customer-focused sales.

Radio had been a scrappy, niche seller since the rise of television in the 1950s. Radio salespeople typically sold listener lifestyle, specific target audiences, and—most important—creative ideas.

In 1997, CBS paid tribute to radio when they named radio sales veteran Mel Karmazin to head the 14-station CBS TV group as well as the CBS radio group.31 Karmazin had led Infinity Broadcasting to the prominence that made it a fit partner with Westinghouse and CBS in a three-way merger. Karmazin made immediate and dramatic changes in the way CBS sold time on its owned-and-operated stations, including a change in compensation structure from salary-plus-commission to commission-only. I use the word “dramatic” without hyperbole: the changes brought both an immediate jump in the price of CBS stock and positive reaction from Wall Street investment houses.

In a rare interview (in Broadcasting & Cable), Karmazin explained the move: “The reason to pay people a salary is to control the costs. My view is, if the sales person is making a ton of money at 3 percent, then I’m making a zillion dollars at 97 percent.”

Karmazin felt his radio roots would serve him well at CBS-TV: “There are television people who look at a 12 rating and say, ‘Oh my God, it’s only a 12 rating.’ I look at a 12 rating and say, ‘Wow, it’s a 12 rating!’ I’ve never seen such big ratings. So there’s a mindset where you’re able to deal with marketing and sell a lot more competitively than people in television historically have, where there are six competitors versus 30 in radio.”

The results after one year of Karmazin’s tenure at CBS prompted the company to name him president and chief operating officer responsible for CBS radio stations (there were 150 of them at the time of his appointment), CBS TV stations (there were 14 of those), the outdoor advertising company TDI, and the CBS TV network.32

Karmazin delivered a 12% gain in cash flow for CBS in the first quarter of 1998, his first as chief operating officer. Announcing those figures, he asked his managers for $1 billion in cash flow by the end of 1999. “Not an analyst we could find thinks he won’t get it,” said Inside Radio. Karmazin later rose to the top at CBS when the company’s chairman, Michael Jordan, announced his retirement.

Karmazin was so well known in the radio industry that Inside Radio called him only by his first name. Crain’s New York Business underscored that by saying, “In the world of radio, when they talk about a guy named Mel, there is little doubt who they mean.” To those in the industry, the letters M-E-L were as well-known as the letters C-B-S.

When CBS-TV reclaimed the rights to NFL football’s AFC games through the year 2005, salespeople from CBS radio properties were asked to work with network and station sellers on the TV side. The feeling was that radio’s history of creative selling would help CBS recoup its $4 billion investment.

That idea is supported by Ron Aldridge, publisher and editorial director at Electronic Media. “If I were a TV GM, I’d find the best radio salespeople in my market and teach them TV. They already know how to compete. All media are converging and merging,” he says. “The means of distribution is much less important.”

Diane Sutter of Shooting Star Broadcasting refers to the first TV station she owned, KTAB in Abilene, Texas, when she says, “TV has to compete the way radio did before. Increased competition means (local) TV sales people have to become marketing consultants for their advertisers. They’re problem-solvers instead of commodity brokers.”33 (See Figure 6–7.)

Local TV advertising dollars were $11.436 billion in 1997, according to Mc-Cann Erickson figures prepared for Advertising Age. That figure is virtually double the dollar level of just 10 years before. Still, some advertisers are reluctant to commit more than a fixed percentage of their budgets to television.

That’s the mission of TVB, according to its president, Ave Butensky: “TVB’s concern … is advertising and we try to talk to [clients] about the values of television, why they should use television and how it will work for them. There still is a major naivete insofar as this business is concerned. Television is 52 years old. Its ad revenues passed newspapers for the first time only in 1995; it took 50 years to get there and not by a lot.”

Butensky cites specifics: “[W]e still have a lot of people who don’t know how to use television. The May Company, as an example, allegedly has a rule that says, thou shall not put more than 14% of your money in electronic media. Something we suspect was written some time during the Grant administration and never changed.”34

While Butensky has his tongue in his cheek when he says that, it’s true that some advertisers refuse to give in to electronic media. For example, the newspaper remains a formidable competitor to television, cable, and radio. See the discussion about selling against newspaper in Appendix A.

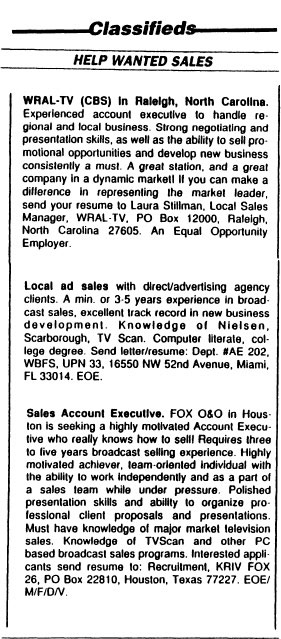

FIGURE 6-7 These ads for TV sellers reinforce the skills needed: negotiating, new business development, and motivated, team-oriented, polished presentation skills. Thanks to WRAL-TV, Raleigh; to UPN-33, Miami; and to Fox 26 in Houston for permission to use their ads.

Networks are the most important source of programming in television, based on the number of hours scheduled in the typical week. Affiliated stations rely on their networks to fill important daytime and prime time programming slots. To cement an image in the local community, local broadcast television relies heavily on news. A strong news image allows the station to maintain overall visibility and to support advertising rates.

As you saw in the outline of TV day-parts, many affiliates program early-morning news broadcasts before the network morning shows, and a noontime newscast as well. They use the programming for its own merit and to promote their “big newscasts” (6 p.m. and 11 p.m. Eastern and Pacific time, 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. Central and Mountain).

In broadcast television, the lower the channel number, the better the signal and coverage area. Channels 2 through 6 are low-band VHF (very high frequency) stations. Channels 7 through 13 are high-band VHF stations. The low-band stations have a 100,000-watt power limit while the high-band stations are allowed 316,000 watts to accommodate for the differences in signal quality.

Channels 14 through 69 are UHF (ultra high frequency). These stations are subject to more interference than VHF channels. Even with transmission power up to 5 million watts, UHF signals tend to require special antenna treatment when received over the air.

The early evening daypart (6 p.m. to 7 p.m.) may include a 30-minute local newscast and a 30-minute network newscast. In many larger markets, stations produce an hour or more of local news, adjusting the time of the network newscasts as needed.

A stable, well-liked news team is one of the strongest selling points for local TV salespeople. The longer an anchor stays on the air with positive reaction from local viewers, the more the station’s image and advertising rates are enhanced. The opposite is also true: a revolving door at the anchor desk reduces viewer confidence and, therefore, advertiser confidence.35

New York’s Channel 7 News (WABC-TV) has featured anchor Bill Beutel for the adult lives of most of the station’s viewers. At Channel 4 (WNBC-TV), anchor Chuck Scarborough has been a fixture at his station for almost as long. At the same time, Channel 2 (WCBS-TV) constantly churned anchors, reporters, and other on-air personnel for years. That left the station with the fourth-ranked local newscast at 6 a.m. (of four on the air at the time), third at 6 p.m. (of three), and third at 11 p.m. (of three). That’s the performance that led CBS to put radio’s Mel Karmazin in charge of the TV station group.

I use New York as an example, but the principle applies to any market size. A well-loved local newscast is difficult to beat without long years of building a news image to counter. Working for a client in Savannah, Georgia, I saw firsthand how long-time and beloved Channel 11 anchor Doug Weathers outlasted many a challenger at the other stations. Local news is a franchise for local television.

The key to effective use of the news franchise is understanding the psychographic of the news viewer. Only in the late 1980s and early 1990s did television begin to research its product as thoroughly as other consumer products did. The pressure of competition and the decline of shares at the network level caused TV operators to employ positioning studies to learn more about news viewers.

Which stories are demographically driven? Which are driven psychographically? The answers allow stations to target more precisely with stories that attract older listeners at 6:00 p.m., for example, and younger females at 11:00 p.m..

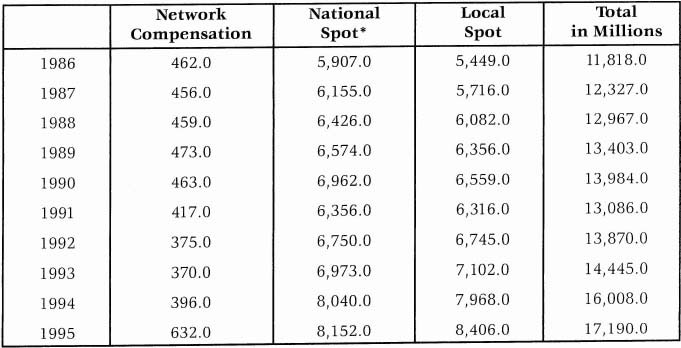

The first buyer of local TV time is the network, if the local station is an affiliate. Networks provide compensation to their affiliates at the rate of $200 million each for ABC, CBS, and NBC. Each local station gets some portion of the compensation pool based on the contractual agreement between the station and the network and how many clearances the local affiliate provides. (See Table 6-7.)

Network compensation is in jeopardy, however. CBS affiliates were expected to return a total of $50 million in cash and advertising inventory to help the network cover the costs of acquiring NFL football rights. In markets smaller than the top 100, ABC-TV reduced compensation payments to affiliates that carry Monday Night Football. NBC network president Neil Braun proposed to his affiliates that instead of traditional compensation, the affiliated stations would be offered the chance to buy into programming and reap the profits of those investments.

Compensation plans are subject to change as the affiliates play tug-of-war with money that has flowed to local stations since the inception of the TV network concept. It’s important to note that the sellers at local television stations will be asked to make up some of the difference if the compensation packages evaporate.

A range of buyers exists for local television.36 At one end of the spectrum are bulk buyers. They demand that the TV station delivers x number of demo points by day-part, because their needs are driven by cost per point. If your points do not fit in a given week, they will be moved to another week or to another flight to match the points needed.

Bulk buyers cannot assure their advertisers about what part of the schedule will run until after it’s on the air. If there’s a need for make-goods, it’s up to the TV station to find them and match them to the original points purchased.

Bulk buys are often made by advertising agencies that buy large blocks of time without a specific client in mind. They buy based on a favorable rate, then spread the opportunities among their clients once individual advertiser strategies are established.