Chapter 10

![]()

The Long Journey to a Customer-Focused Learning Organization

Transformation is a process, and as life happens there are tons of ups and downs. It’s a journey of discovery—there are moments on mountaintops and moments in deep valleys of despair.

—Rick Warren, theologian

INTRODUCTION

We organized our service excellence principles around my 4P model of the Toyota Way—philosophy, process, people, and problem solving. We described in great detail how these four simple ideas work for service excellence organized around seventeen principles. We illustrated these principles with many case examples, some real and some fictional, some manufacturing and most from services.

We do not expect these principles to translate directly into a things-to-do list or into a road map where you can plot out your transformation over the next five years. That would be contrary to the models we have presented of improvement. Improvement is an individual and organizational journey and requires skill development over time. You need to learn your way, not “implement” principles.

This presents a conundrum because you would like some advice. We decided that instead of a laundry list of implementation tips, we will use stories to illustrate how these principles apply in several situations, beginning with a start-up service company that Karyn has been joyfully advising. She is using all the principles in this book to coach taxi drivers, who have a lot of driving experience but little previous business experience. During weekly meetings, Karyn has been coaching them as they work their way through the process of building an exceptional taxi business focused on collaboration and 100 percent customer satisfaction. We will then revisit our fictional cases of NL Services and Service 4U one last time to address the question: How can we engage and develop leaders at all levels in a journey to become a high-performance, customer-focused organization?

These examples will leave you with a vivid picture of what is possible when serious people dedicate themselves to excellence with the help of compassionate and experienced coaches. It will be difficult to conclude that lean does not apply to services. It will be difficult to argue that it takes super people who are Japanese to follow this model. Ordinary people with extraordinary vision and persistence are doing remarkable things throughout the world following the simple guidance of the Toyota Way—respect for people and continuous improvement. Let’s listen in while Karyn tells us the story of NTL’s journey in light of the 4Ps and 17 principles.

NATIONAL TAXI LIMO AND THE 4Ps

I travel a lot so I take a lot of taxis. That’s how I met Joe Draheim, one of the owners of National Taxi Limo, a new personal transportation service near Chicago. Joe is in his early thirties, and when I first met him, he was dressed in jeans and a hoodie. The little bit I knew of Joe’s background came from clues from other drivers: “Joe’s a great guy, but he doesn’t seem to want to work really hard. He likes to ‘hang out,’ and he’s not always reliable.”

One day, when Joe picked me up at O’Hare Airport, he excitedly told me about his new venture: “I’m working with a couple of other guys to start our own personal transportation company. We know it’s going to be hard, but we have an idea that we think is pretty different. Taxi drivers live ride to ride. And they’re always worried that someone is going to steal their ride. If customers ride with another company, even once, they’ll probably never come back. So if you own your own cab, you can never take a day off. And drivers sometimes answer the phone while they’re driving so they don’t miss a customer’s call, and that’s not safe. What we want to do is create a network of ‘driver partners’ that will work together. We’ll have an app, like Uber, so customers can book, track, and pay for their ride through the app, but we’re going to combine that with an actual taxi dispatch service. And we’re only going to work with licensed taxi drivers who have their own cars and commercial insurance. That way we can help small, independent taxi company owner-operators support each other so that they can grow their businesses cooperating and helping each other out. We also want to help them become better businesspeople. Right now they’re so busy driving, they don’t have time to work on their own development as business owners.”

As Joe and I continued to talk, Joe told me more about the vision for the new company: “Taxi drivers are a pretty independent lot—that’s probably why they’re driving taxis! They don’t like being told what to do. Funny thing is, though, they don’t seem to mind telling other people what to do, so there’s often a lot of bad communication going on. We don’t want our company to be like that though. We want to create a different culture, a culture where we work together with our driver partners. That way we can take care of our customers and take care of each other. Problem is, it all seems good in theory, but we’re having a little trouble really getting it all going.”

That’s how I got started working with National Taxi Limo. Could the principles of the Toyota Way—respect for people and continuous improvement—apply and work for a personal transportation company? How could someone like Joe, a 32-year-old taxi driver with a spotty track record and no previous leadership experience, develop himself and develop others? And how would the typical lean tools work? How could something like visual management be creatively adapted for taxi drivers who need to keep their eyes on the road driving? How could I help Joe and his partners use the Toyota Way to develop themselves professionally and personally so that they could help other taxi drivers improve their circumstances by continuously delivering service excellence to ensure that their customers were satisfied? It helped that Joe was on fire with passion for the business, and reading The Toyota Way, which I gave him, just fueled the fire even further.

Philosophy: Long-Term Systems Thinking

Principle 1. Passionately Pursue Purpose Based on Guiding Values

Like all journeys, NTL’s began with a single, very important step: the definition of its purpose for existing in the world. Joe and his partners Todd VanderSchoor and Ken Kaiser determined that their purpose was to create a personal transportation service that actively worked with their driver partners to help them become better businesspeople so that they could grow their businesses while offering all customers the best in personalized, personable service at a reasonable price. This was a mouthful, but it did provide a starting direction.

“This all sounds good,” said Joe during a meeting with the partners and me. “However, how do we actually do that? And how do we make sure that we are on track to reach our goals? The app isn’t ready, and we’re not even dispatching yet. How are we going to make sure we get to where we want to go and don’t get sidetracked? If only we had a map to get us there.”

“Funny you should bring that up,” I said, pointing to the large piece of blank paper taped to the wall. “What we’re going to do today is create a way for us all to see where NTL is now and where you need to be in the next year, so that you’re making the right progress toward your purpose. If we had not taken the time to identify the purpose, we would not even know what direction we want to go.”

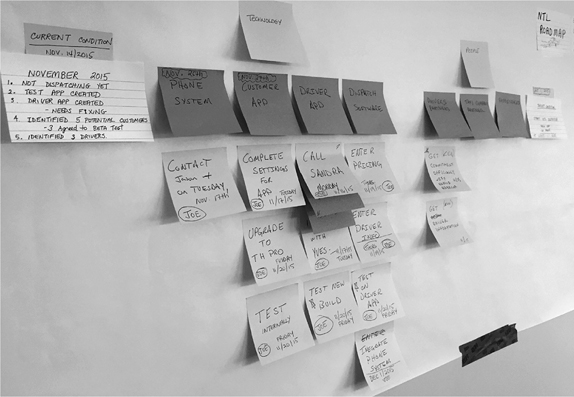

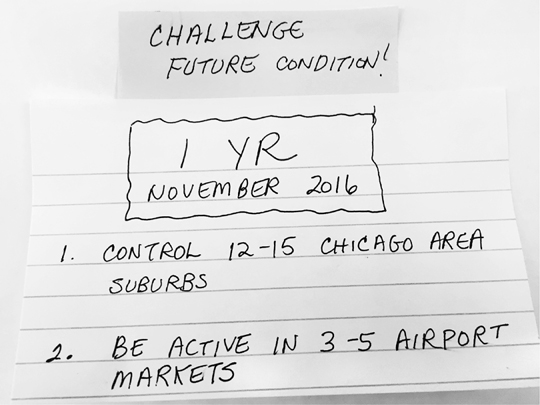

“We’ll call it the ‘NTL road map’!” Joe exclaimed. After working together for a few hours, Joe, Ken, and Todd had drawn out the path for NTL’s first year in business (see Figure 10.1). The ‘road map’ was not a detailed action plan with dates and assignments, but rather a set of milestones to work towards, quarter by quarter. Each milestone was written on a Post-it. For example, one Post-it read “Dispatch First Ride.” Joe and his partners then worked to figure out how to overcome the obstacles needed to make that happen. As well as having a good idea of their current state (see Figure 10.2), where they were right now, they also defined where they wanted to be at the end of their first year (see Figure 10.3).

Figure 10.1 NTL road map

Figure 10.2 NTL road map, current condition

Figure 10.3 NTL road map, future condition

Finally, they created a challenge statement to reflect how they wanted to get to their future condition: “Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together.” Now Joe and his partners would have a yardstick against which they could measure all ideas, decisions, and solutions. Any investments or ideas that would not move them closer to their challenge of “Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together” would be a distraction. At first Joe was concerned about the challenge and could not see how a taxi company could possibly achieve it. He was uncomfortable with the uncertainty. But as he and I continued to talk about how important it was to have a challenge to strive toward, he started warming up to the idea.

Joe lamented, “But we’ll never really be able to pick up and deliver every ride on time . . . in reality, that would just be impossible, wouldn’t it? There are so many things that can go wrong. Cars breaking down, road construction—too many to name,” said Joe.

“Really?” I challenged. “You’re pretty committed to caring for your customers and driver partners. If you don’t pick up every ride on time, what’s the consequence? What’s going to happen to your business?”

“You’re right,” said Joe. “We won’t be here long.” Thinking for a moment he added, “Maybe we don’t know how to do it now, but working together we’ll have to learn to solve the problems that we know are going to occur. We’ll simply figure out how to get to ‘every ride on time.’ We’ll just have to strive toward that goal.” Joe and NTL now had a challenging future-state vision to work toward together, for as Joe said, “Now you see it. Now you do it.”

Process: Flow Value to Each Customer

Principle 2. Deeply Understand Customer Needs

Joe and his partners had worked for a variety of taxi companies over the years. Having spent countless hours talking with customers as they drove them for other companies, they started out with a pretty deep understanding of customer needs and what service excellence meant to them:

1. Safety first—a safe ride was always most important.

2. On time, every time—customers want to be picked up and dropped off on time.

3. Clean cars and personable, friendly drivers—delightful in-car experience.

4. Reasonable price.

With that understanding, NTL could begin to form some hypotheses about what delivering that service excellence would look like. For example:

1. Drivers won’t text or answer the phone while a customer is in the car. Ever.

2. Drivers will use the app to give real-time status updates to customers and dispatch about pick-up and drop-off times.

3. Drivers will wear suits and tuck in their shirts.

4. Cars will be cleaned—inside and out—on a regular schedule.

As well as having a good understanding of their customers’ needs and the opportunity to gather feedback from them on an ongoing basis, each and every ride, Joe and his team also used their taxi driving experience to start thinking about how to keep all the rides “flowing” and to work on leveling their workload.

Principle 3. Strive for One-Piece Flow

Think about it; although it may not seem obvious at first, taxi drivers actually have an innate understanding of flow! They are on the road every day, so both flow and barriers to flow—which the partners decided to call “roadblocks”—are a huge part of a taxi driver’s everyday experience. Anything that stops or slows down the ride once it’s started is a roadblock and a barrier to flow. And taxi drivers know how important flow is: neither they nor their customers want to stop moving once they get going! So finding ways to keep the ride moving, from the moment the customers are picked up to the moment they are dropped off, is of the utmost importance in delivering service excellence in the world of taxi driving.

They also know that, in general, Monday mornings and Thursday nights will be busiest for airport drop-offs and pick-ups, as that is when the majority of business travelers are heading to the airport and coming home. Striving to be on time, every time, would mean paying careful attention to ride patterns and determining the right number of drivers during those times. In order to do this, the partners decided to track each day’s ride destinations and times on a visual board so that they could identify patterns and trends. And they started a spreadsheet to track ride “target” and “actual” times: what time was a customer supposed to have been picked up, what time was she actually picked up, and if she wasn’t picked up on time, what was the cause? In this way, Joe, Ken, and Todd would be able to begin to identify the roadblocks and barriers to flow. Once they identified them, they would be able to start to use PDCA to figure out the causes and identify potential countermeasures that they could experiment with daily.

Principle 4. Strive for Leveled Work Patterns

After a month of keeping close tabs on what was happening day in and day out, Joe and his partners realized that they needed to set up separate drivers and systems for airport rides and local rides. Most airport rides were booked in advance by “regulars,” business travelers, on a fairly predictable schedule; however, local rides tended to come from customers “pulling” for immediate pick-ups: they wanted to go to the grocery store or to their friend’s house, and they wanted to do it right now. It simply took too long to get drivers from the airport back to local, suburban destinations to be able to have on-time pick-ups. And it was difficult and stressful for the drivers.

Separating “airport” drivers and “local” drivers substantially improved “traffic flow” and reduced driver stress from having to rush back from the airport to pick up a local ride. Joe and NTL learned that it was possible to take a positive step toward leveled work patterns, even in a business of erratic customer demand. The flow of work became much smoother for the drivers. And customer satisfaction improved too. “Having a whole separate set of drivers and processes wasn’t what we had envisioned when we started out, but having our challenge statement of ‘Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together’ really helped us to think differently about how to solve the problem,” said Joe. “It’s a lot easier for us to cover every ride this way, and customers get picked up when they want to be picked up.”

Principle 5. Respond to Customer Pull

Just as they have an understanding of one-piece flow, taxi drivers also have an innate understanding of customer pull. In fact, customers pull for their services 24 hours a day. “It’s important that our customers are able to reach us whenever they want to and however they want to,” Joe told me when we started working together. To that end, NTL customers can pull for airport or local rides by booking in advance through the app (which is what most regular business travelers do), using the online booking function on NTL’s website (used most often by customers booking rides to the airport for vacations), calling NTL on the phone (customers wanting local rides usually call), or sending an e-mail directly (customers who have questions about timing of rides or who have special requests). As Joe said, “Making sure our customers can reach us anytime using whatever method works best for them is one of the most important parts of delivering service excellence. If they can’t reach us immediately, they’ll just call another company. Then we’ll lose the ride. And that will be bad for our customers, as we won’t have the opportunity to wow them with our service, and it’s bad for our business too.”

Principle 6. Stabilize and Continually Adapt Work Patterns

“I think we’re having a problem,” Ken said during our weekly meeting. “Some customers have said they’re frustrated because they haven’t been getting text messages when they land, so they don’t know if their driver is at the airport and available to pick them up.”

“I’ve heard that too,” said Joe.

“And I’ve had that experience,” I chimed in.

“Do you think that everyone is following the same process using the app and in picking up our airport customers?” asked Joe. Ten minutes later, after they polled each driver partner about his process, it was obvious that everyone was doing things differently. “We need to have a standard way to use the app when we’re picking up customers so that they get the information that they need,” said Joe. So, working together, the guys created a first-version standard to try (see Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 NTL app used for airport rides, version 1, standard work

“This makes perfect sense to us, but how can we make sure that all our drivers are aware of the standard and will use it?” Todd asked. After a few minutes of discussion, the partners decided that they would try the simplest solution first—experimenting on themselves. They would photocopy the piece of paper and keep it in the car with them. That way they wouldn’t have anything electronic that they would have to use their phone to reference, and they could jot down notes on the page if something didn’t work well or if they had another idea.

“And since it’s written in pencil, on a piece of paper, it’s really easy to change as we find better ways,” said Ken.

“Gentlemen, try it out next week, and let’s see what happens. We can discuss what happened during next week’s meeting,” I suggested.

“And,” said Joe, “we can look at the problem log for airport rides and see if we had any customers who didn’t get the text message at the right time. We’ll have a great opportunity to learn.”

Principle 7. Manage Visually to See Actual Versus Standard

Joe gushes about visual management and how it has helped National Taxi Limo. Since taxi drivers spend a lot of time driving, it is sometimes difficult for them to have time to stop and “see” the big picture. Just like their rides, their business is coming at them 24 hours a day, 65 miles per hour! However, as in many other service businesses, if they can’t see what is actually happening, everything seems to be random. And if everything seems to be random, how can it be managed so that customers receive the service they need and the business reaches its targets?

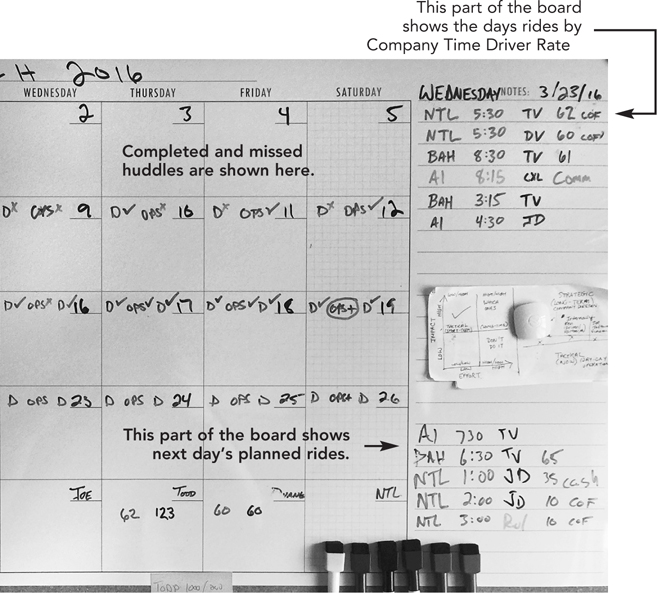

NTL’s visual management systems helps Joe, Todd, and Ken see what is happening on a day-to-day basis so that they can make sense of it and visualize any problems in real time during the day. Joe updates rides, drivers, pick-up times, and revenue throughout the day on a whiteboard in the office. Color coding makes it easy for everyone to see the source of the ride: green is an NTL direct customer, and blue is a ride sent to NTL by another company (see Figure 10.5).

Figure 10.5 NTL daily visual management board

Since NTL is working to grow its own customer base, it’s important for the partners to be able to see how close they are to their target of “NTL-generated” rides each day. If there’s a dropped or canceled ride its noted in red. Beside each dropped or canceled ride is the “reason code.” During the three daily huddles, Joe and the team can quickly review any dropped or canceled rides and make sure that they have countermeasures in place to prevent the problem from recurring. The team is experimenting with three-times-a-day huddles (remember, NTL is a 24-hour-a-day operation), and there is a green check mark or red X beside each, noting whether the huddle took place and whether the standard was followed.

“Being able to see whether we are huddling or not has really helped us get better at it,” says Joe. “And what we’ve found out is that if we don’t huddle, rides don’t get covered or aren’t picked up on time, so huddling is a really important part of our process. Being able to see which ones we’re completing and which ones we’re not has helped us change what we do. Like I said before, ‘now you see it, now you do it!’”

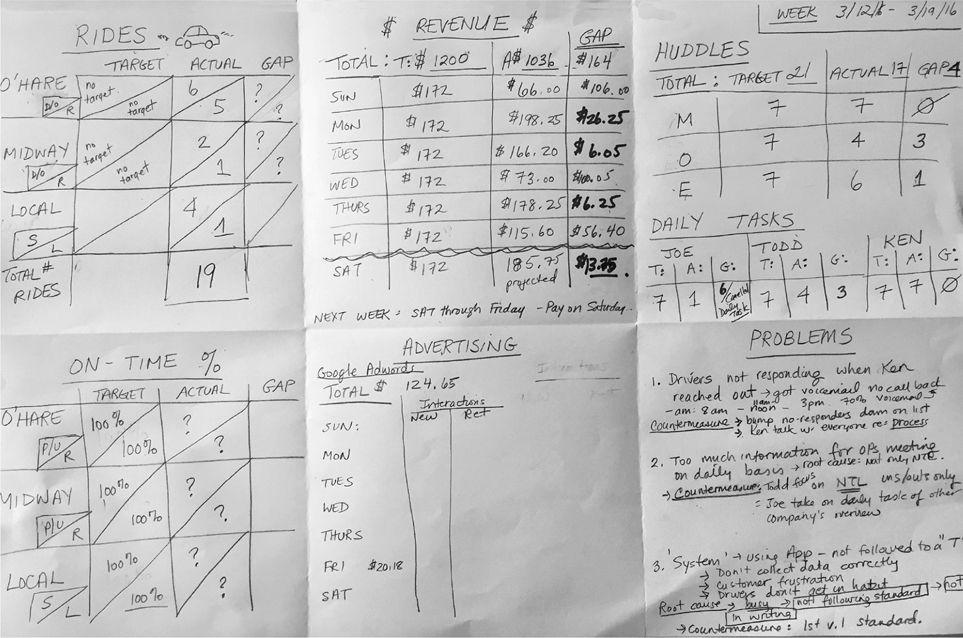

As well as using visual management to understand and manage on a daily basis, Joe, Todd, and Ken also use it during their end-of-week partner meeting to check to see that they are making progress toward their road-map goals (see Figure 10.6). Each week, targets for number of rides, revenue, huddles, and advertising for the next week are set. These targets roll up to the longer-range NTL road map goals. During the meeting, the partners review whether they reached each target, and they go over the problems that occurred during the week. They review the effectiveness of countermeasures that were put in place, and if targets are missed, countermeasures are created for the next week. Everyone can easily see where NTL is compared with where it wants to be. “It’s really easy,” says Joe. “And it will change over time. You don’t have to have a complicated system. You just have to see where you are and where you want be. Then you can figure out how to get there.”

Figure 10.6 NTL weekly summary documen

Principle 8. Build in Quality at Each Step

A few weeks ago, during the weekly partner meeting, Joe said, “I think that we need to talk about jidoka.”

“Jidoka?” said Todd, with a puzzled look on his face. “What’s jidoka?”

Now perhaps you wouldn’t think that taxi drivers would be using terms like jidoka; however, as Joe explained, “The idea of jidoka is really simple, Todd. We have to have a way for all our drivers to recognize a problem right away and tell us about it so we can figure out what went wrong and how to fix it before it happens again. If we don’t do that, our flow is going to stop.”

“I don’t know,” said Todd. “Seems to me that if we stop driving to report a problem, then that is what is going to stop our flow. We’re not a manufacturing company. We can’t just ‘stop the line’ in the middle of driving down the highway!”

“You’re both right,” I said. Then I explained to them that when a problem is detected on the line at Toyota and a team member pulls the andon cord, the whole line doesn’t immediately come to a stop. What happens is that the team leader rushes over to see what the problem is and works to understand the cause and contain it immediately, so the production line doesn’t have to stop.

“How do you think that we could do something like that while safely driving customers?” I asked. After thinking for a while, Todd, Ken, and Joe came up with a plan. “Since on-time pick-up is the most important for our customers, let’s find a way to figure out what is preventing us picking up customers on time first,” suggested Ken.

“Good idea,” said Joe. “If drivers are using the app correctly, as soon as they pick up a customer, whoever is dispatching should be able to see the time in the system. As long as the dispatcher is monitoring the rides as he should, he should be able to see right away if there is a problem or not.” Joe continued, “Then whoever is dispatching can contact the driver and ask why the pick-up was late after the ride is dropped off. That way we don’t have to have people stop driving or use their cell phone to text or answer the call in the car. Then we could discuss what happened during our next huddle in the day so we can make sure the problem is fixed for that day.”

“What if we also created a problem log for late rides?” asked Ken. “Then we could collect all the data about the late rides and the reasons why for the week. We could review the data during our weekly partner meeting and figure out what to try next week to prevent those problems from happening again.”

“And we will know what we need to work on in our standard work too,” said Joe. “When we can see the problems, we’ll be able to fix them and get better at preventing them from ever happening in the first place.”

As Joe, Ken, and Todd have found out, if the customer experience is your top priority, with a little creativity it’s always possible to find ways to build in quality at each step.

Principle 9. Use Technology to Enable People

“Since Uber came on the scene, everyone expects a taxi company to have an app,” said Joe. “Problem is, many of our driver partners aren’t comfortable using all that technology, as they just haven’t used it before. Our customers want it, though, and it’s a great way for us to keep track of our regular rides, so it’s really important that we get everyone used to it and using it regularly.”

Like many other companies in this day and age, NTL is finding that it’s very important to consider the effects of all choices about technology, both for customers and for those working in the business. To make sure that NTL’s technology is enabling both customers and drivers, Joe and the team have a process for testing each piece of technology with a select group of customers and driver partners. All information on the website is available on a single page, so customers don’t have to click through many screens to book a ride. And after gathering feedback from a number of customers who used the website, changes were made in how the booking screens worked.

In addition, any changes made to the customer interface of the app are tested with a select set of customers, and changes to the driver interface are tested with a set of driver partners. If the functionality of the app doesn’t support NTL’s challenge statement of “working together,” then it’s back to the drawing board! “We control what technology does for our customers and our company,” says Joe. “The technology works for us. Not the other way around.”

People: Challenge, Engage, and Grow

Principle 10. Organize to Balance Deep Expertise and Customer Focus

When I first started working with NTL, the partners’ roles and responsibilities were vague at best—everyone would do everything. And this seemed like it might work . . . until . . . NTL actually started dispatching. Once it began, Joe realized that he and Todd and Ken needed to have a better division of company responsibilities. As noted earlier, the taxi business is a 24-hour-a-day one, and in order to make sure that rides weren’t missed because the person who was scheduled to answer the phones fell asleep, the partners needed to create a daily schedule of who was responsible for intake and who was responsible for dispatch.

They also realized that they needed to each take primary responsibility for a business area, so that tasks such as bookkeeping and marketing were completed in a timely manner. Joe became the VP of Operations, Todd became the treasurer and VP of Finance, and Ken became the president. Ken, who has the greatest access to potential driver partners from his long tenure in the taxi industry, is responsible for working with the driver partners to make sure they have the correct airport and local coverage; Todd, who has a background in business, is responsible for keeping all the finances in order, including ensuring that NTL is reaching its daily “ride”’ goals so that all the driver partners and the business are taken care of financially. Joe, who enjoys analytics and web design, takes care of the app, website, and advertising and is in charge of finding ways to get new customers for the business. Joe is often the dispatcher, as well.

The three daily huddles came out of this division of labor. To make sure that the partners were communicating and “working together,” they determined that they would have three quick daily check-ins, or huddles, two “dispatch huddles” to make sure their driver partners were organized and on track to pick up all customers on time, and one midday “operations huddle” with all three partners to make sure that revenue and other goals were being met each day.

Each partner is also responsible for completing a standard set of daily tasks as well as updating the visual management spreadsheet at the weekly partner meetings. So far, this has been working well to balance customer needs and ensures that each partner is working in an area that is his strength. As Joe says, “Once we decided to split out our organization this way, it really helped us to make sure that ‘every ride is on time, every time’ and that we’re working together.”

Principle 11. Develop a Deliberate Culture

“Taxi culture isn’t always the most pleasant one,” Joe said to me when I first started working with NTL. “There can be a lot of yelling and bad communication, and people don’t trust each other because they think other drivers are going to steal their rides. That’s not what we want our culture to be like at NTL, though. But I’m not sure how to make sure that doesn’t happen to us. I really want us to be successful at creating a different kind of culture, where people care about each other and work together to take care of the customer, but I’m not sure how to do that.”

“It’s not going to be easy,” I said. “The people that you are working with are used to the old taxi culture. But it can be done. Remember your challenge statement: ‘Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together.’ You are going to have to make sure that every decision you make and every interaction you have will support that challenge statement. And you are going to have to make sure that Todd and Ken understand that as well. When problems happen—and they are going to happen all the time—you’re going to have to create your culture of ‘working together’ by working together to solve those problems.” Joe smiled and nodded, but I wondered if he really understood.

Luckily, a day or so later, we had an opportunity to turn theory into deliberate practice when I got a text message from Joe about a situation that had happened earlier that day. A customer had complained to one of NTL’s suppliers about one of NTL’s drivers. The customer hadn’t liked the way the driver partner was driving, and the supplier was threatening to stop sending its overflow rides to NTL.

“I’m not sure how to handle this,” Joe said to me when I gave him a call. “I’m not used to having this kind of conversation. In the past, I would just ignore the problem or yell. That never really helped anyone though, and it’s definitely not the kind of culture we want.” So, for the next half hour, Joe and I talked through the different strategies he could take to deal with the driver partner and the supplier so that they could work together. Once Joe settled on the approach, talking first with the driver partner and then with the supplier, Joe and I practiced both conversations until he felt comfortable that he knew what he was going to say. Joe then decided that he would have both conversations the next day when everyone was fresh and some time had passed, so that any initial anger would have dissipated.

You can imagine how happy I was when Joe called me the next evening. “Everything went great,” he said. “The driver partner was certainly happy that no one yelled at him, and he was very open to take the suggestions about how to improve. He really wants to continue to work with us and make sure our customers are satisfied. It was a really great experience. And our supplier was even happier. He really felt we cared about him and his customers. Instead of not sending us any more of his overflow rides, he decided to send us more! This is what I dreamed of when we started NTL: everyone working together so our customers can be satisfied!”

Since then, Joe and the team have had many other opportunities to create their culture deliberately, as problems occur constantly. And for each problem that they have to solve, and for each decision that they have to make, if they aren’t sure what to do, they reflect on whether it is going to get them closer to the goal of “Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together.”

Principle 12. Integrate Outside Partners

Just like every other decision NTL makes, the choice to work with an outside business partner is made through the lens of NTL’s purpose. I was so proud when Joe, Ken, and Todd parted ways with an auto dealer because the dealership did not fit their values.

A few weeks earlier, Joe had called me on my cell. “I’m really excited,” he said. “We’re about to buy a car for NTL. Todd and I have spent a lot of time looking, and we think we’ve finally found the one that our customers will really like and that’s within the budget. I’ll text you a picture after we buy it.”

I didn’t receive any picture, so the next day I gave Joe a call. “Just want to say congratulations on the new car!”

“Oh,” said Joe. “We decided not to buy it. The longer we stayed at the car dealership, the more we realized that the people there just didn’t have the same values that NTL does. It seemed fine at first, but then we realized that they didn’t really understand what we meant by ‘working together.’ And they didn’t seem to be interested in solving problems either. Since we plan to buy a lot of cars as our business grows, we want to make sure that we are working with a dealer that shares our values. If the dealer doesn’t, how will we be able to reach our challenge of ‘Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together’? What if we need a new car and the dealer can’t get us one quickly enough? Or what if the quality isn’t good and it breaks down, and so we miss rides? Problems are always going to happen, so if the people at the dealership didn’t want to work on solving problems during this first transaction, what’s going to happen later on? If we want to be sure to satisfy our customers, we’re going to have to make sure that all the people we work with understand and share our values and philosophy—or are willing to learn!”

Principles 13 and 14. Develop Fundamental Skills and Mindset and Develop Leaders as Coaches of Continually Developing Teams

“We’ve missed a couple of rides this week, and I think I’ve figured out why,” Joe said at the beginning of one of our weekly meetings. “I think that there are a couple of things going on. First is that we don’t really have a set plan about who is going to contact our driver partners to schedule the rides. Sometimes Ken does it, and sometimes I do it, but sometimes one of us thinks the other is going to do it, and then nobody does.

I think I’ve come up with a plan to test this week: Ken and I will split the driver partner list in half, and each of us will call the driver partners on our list first thing every morning. Then, when we get together for the morning dispatch huddle, we’ll know that each driver partner has received a call. The other problem is that Todd hasn’t dispatched before, so he’s just learning. He’s doing a good job, but I think that he needs more training so that he can be more confident. I’ve already set up some time for him and Ken, who’s really the dispatch guru, to get together.”

“Both ideas sound great,” I said. “You, Todd, and Ken all have different skills and a different amount of experience driving taxis and dispatching. It’s going to take some time to understand and then help each other develop skills in the areas that you need to learn more about. Then, as you get more driver partners on board, each of you will be able to help develop them as well.”

Joe agreed and then said, “It’s interesting. I never realized how much of running a company was about teaching and developing people. But each of us is good at some things and less good at others. We’re all helping each other learn and grow, and that’s what’s helping our business develop and helping us solve the problems that come up.”

In order for NTL to grow and develop, Joe has learned that his role as a leader is to coach and develop—and be coached and developed by—his business partners.

Principle 15. Balance Extrinsic-Intrinsic Rewards

“I’ve never been happier in my life,” Joe said to me the other day. “And it doesn’t have to do with money, because there have been times when I made more money just doing straight taxi driving. And I’m working harder than I’ve ever worked in my whole life. I used to really look forward to just ‘hanging out,’ but now if I have any spare time, I use it to do something for NTL. It’s not what I expected.”

“Interesting,” I said. “Why do you think that is?”

“Well,” said Joe, “I think that it is because, before, I was making money and taking care of myself, but now I’m responsible for lots of other things: for our driver partners earning a living so that they can take care of their families; for our customers, making sure that they are having the service experience they deserve; and for Todd and Ken, my business partners, making sure that they are getting what they need. It’s not easy turning our vision of ‘On Time. Every Time. Every Ride. Working Together’ into reality, but it’s a lot more rewarding than I ever expected it to be.”

Problem Solving: Continuous Organizational Learning

Principle 16. Continuously Develop Scientific Thinking

“Tell me again what it stands for?” Joe asked.

“P is for ‘plan,’ D is for ‘do,’ C is for ‘check,’ and A is for ‘act,’” I said.

“And it’s a circle, right?” said Joe. “It just keeps going, and it’s never ending.”

“Yes,” I answered. “It’s never ending. It’s the way we can solve every problem and make sure that we reach our goals. When we have a challenging goal, we don’t know how to reach it. That’s okay. We need to learn our way toward the goal and figure it out as we go.”

“And we do that by spinning the PDCA wheel over and over again!” exclaimed Joe. “I get it! Makes total sense to me,” he said as he reviewed the Post-it note I’d given him. “I’m going to keep this and put it where I can see it every day.”

Joe and I have been working together for the past six months. And during that time, Joe has been learning to use PDCA to solve a variety of problems that have gotten NTL up and running and progressing toward its goals. Getting the app completed and in customers’ and drivers’ hands, finding new customers, figuring out how to balance local and airport rides are just a few. To make sure that Joe is learning and making progress, we have weekly coaching meetings—and Joe can always reach out in between if needed! During our coaching meetings, I ask him questions and listen as he struggles thinking the answer through. When the need arises, based on the challenge being worked on, I teach him a tool or concept. During the meeting we review progress toward goals and deal with any roadblocks. Then we set the challenge for the next week. And Joe’s daily huddles with his partners are an opportunity to rapidly spin the wheel as problems arise that day.

Spinning the PDCA wheel daily, Joe is learning through doing, with me as his coach, and he is also learning through coaching others. He has explained and taught PDCA to his business partners and driver partners, and he coaches them through solving problems that they are having. We have not approached this strictly following the practice routines of the improvement kata and coaching kata, but we use a similar pattern of improvement, and it is working.

Principle 17. Align Improvement Objectives and Plans for Enterprise Learning

Every improvement that any of the guys at NTL undertakes is prioritized against the original NTL road map that they created to see where they are going. As they progress along the road map, sometimes forward and sometimes sideways or backward, they are figuring out how to overcome the obstacles that are keeping them from reaching their next target condition.

And with every ride, every day, they are solving problems for their customers. One customer asked about booking a ride from a regional airport to a suburb. When Joe saw that the suburb was over two hours from the airport, he called the customer back and asked if she had the right airport. The ride would be exceptionally long and expensive. The customer then realized she could make a different airport choice and was extremely grateful to Joe and NTL for helping her avoid a potential problem. What Joe and the guys at NTL understand is that solving problems for customers, with each and every ride, is simply the business that they are in.

What Did We Learn from NTL?

There is no doubt that Joe and the guys at NTL are actively and “passionately pursuing their purpose” based on the guiding values that support our service excellence 4P model.

Challenge

As the partners in a new start-up company, Joe, Ken, and Todd don’t know how to reach their goal of “Every Ride. On Time. Every Time. Working Together.” There is a lot of competition in the personal transportation industry from established regular local taxi companies as well as from other models such as Uber and Lyft. In order to differentiate themselves and consistently deliver service excellence while keeping prices low and competitive, Joe and the guys have to challenge themselves to think—and do—in new and different ways, every single day.

Systematic Improvement

The partners of NTL embrace continuous improvement. “Everything is constantly changing,” says Joe. “As we get more and more new customers, each of them wants different kinds of things, and new problems keep coming up. And I just read an article that said that Lyft and Google are going to have self-driving car services in the next few years. We’ve got to make sure we keep up with what our customers are going to want in the future. And we’ve got to start thinking about that now. It’s like Henry Ford said, ‘If we’d asked our customers what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.’ We want to be around and helping our driver partners grow for a long time. And if we don’t keep improving our service and our service offerings, we’re never going to be able to keep up.”

And continuous improvement starts with each leader. Previously, Joe struggled to finish things—now he isn’t having that problem anymore. Now he wears a suit and is reading books and is totally engaged. He has a vision of himself as an entrepreneur and is looking forward to starting and owning more businesses!

Workplace (Gemba) Learning

Although Joe, Ken, and Todd all have experience in the taxi industry, NTL is new. And although they can rely on some of the experience they have from the past, in order to create NTL, they need to learn, one ride at a time, what their customers want and how to solve the unique problems NTL faces on its journey to fulfilling its purpose. NTL is not Uber, it’s not Lyft, and it’s not any of the taxi companies that Joe, Ken, and Todd have worked for in the past. It’s NTL, and the only way it will be able to become the unique company that NTL’s customers and driver partners want is to learn what works and what doesn’t, through experimentation, in the gemba, on the job.

Teamwork and Accountability

Taxi culture is not one that is often associated with teamwork or accountability. Many people become taxi drivers because they like and want the independence, and they don’t want to have to answer to anybody else. Before starting NTL, Joe shied away from what he called “tough conversations.” Now, however, he’s having them regularly with software companies, driver partners, and vendors. Customer needs are first, so he has to be accountable and make sure that others are accountable as well. The “working together” part of the NTL challenge statement is the glue that holds the rest together. If the solution to an “every ride, on time, every time,” problem doesn’t involve “working together,” the NTL guys don’t do it.

Respect and Develop People

This is right in the company vision of working together for 100 percent customer satisfaction. Every time the partners solve a customer problem, or solve an internal team problem, or learn to deal with outside partners, they are referring to this vision. Collectively this learning brings them a step toward the ideal of respecting and developing everyone in and affected by the enterprise.

WHY LIMITED LEADERS PRODUCE LIMITED RESULTS

It would be a wonderful world for consultants if all of our clients were as open-minded and eager to learn as Joe and his partners. Unfortunately, that is just not so. Leaders generally get to where they are because they have drive and passion, which often means they have egos and can be a bit stubborn. They know what made them successful and they want to keep on doing that. As we have learned, habits can be replaced with better habits, but it takes a lot of work.

NL Services: Training Classes with PowerPoint Don’t Change Leadership Behavior

It was Monday evening. It had been a long but satisfying day at Service 4U. Sam McQuinn was in the car heading out to meet Mike Gallagher, who had taken the position of EVP of Corporate Lean Strategy for NL Services after Sam had moved over to Service 4U. Mike had texted that he would be a few minutes late; a last-minute phone call from corporate was putting him a little behind schedule.

“Funny how things work out,” Sam thought to himself as he swung his car into a parking space. “A year-and-a-half ago that’s exactly where I would have been.” As he walked into the restaurant (coincidentally, the same one where he and Sarah Stevens had met before he worked at Service 4U), he realized how long ago and far away those frantic Mondays at NL Services seemed to be. Sam was looking forward to seeing Mike. They had kept in contact for a little while after Sam had left but then lost touch. Sam had been a little surprised when Mike gave him a call out of the blue and asked if they could meet for dinner, but he had to admit to himself that he was quite interested in hearing how NL Services was doing.

“Sorry I’m late,” Mike apologized as he reached out to shake Sam’s hand.

“No problem, Mike,” said Sam. Laughing wryly Sam said, “I know it’s been a while, but I guess I haven’t quite wiped from my memory all those crazy Mondays at NL Services.”

“Yeah,” said Mike, shaking his head and sitting down heavily in his chair, “I guess not much has really changed since you left. Still fighting with corporate about those numbers every Monday and spending more time on the phone begging and pleading with the regional managers than I would like. It’s exhausting! And since we haven’t been doing any lean work over the past six months, things have gone backward real fast.”

“Sorry to hear that,” Sam said. “I didn’t realize that NL Services has stopped doing lean. Last I had heard, the work with that consulting company, Lean Mechanics, was moving right along. They’re a big, well-established company. I’m surprised to hear that you aren’t working with them anymore.”

“Yeah,” said Mike. “I’m kind of surprised too. Everything seemed to start out so well with them. We were really impressed with their sales pitch, including all the other examples of companies like ours that they had worked with who claimed great successes with their Standard Implementation Program. The whole thing seemed so easy on paper. Their senior lean experts would come in, they’d run twoday training classes at our corporate officers for the execs and senior managers on lean tools, and then the senior managers would each get one of Lean Mechanics’s lean experts to help them implement the program in their area. Lean Mechanics supplied us with everything they said we would need, and they had great-looking PowerPoint decks on all the tools: 5S, value-stream mapping, standard work, and problem solving. We licensed all the training materials so that once our people were trained, they could take the material back with them for reference when their lean expert wasn’t around to help.”

Sam could see that Mike was getting more and more uncomfortable as he told the story. “Well,” said Sam, “seems like they were very organized and had everything well laid out. Lean Mechanics really seemed to have a plan. What happened?”

Shaking his head, Mike said, “It’s like the old saying goes, I guess—even ‘the best laid plans’ . . . As I said, the plan really did look great on paper. The problem is that after all the senior managers finished their training classes and went back to their areas, they just didn’t stick to the plan, and they just led the implementation however they felt comfortable. Once they got back to their areas, they said that the material in the PowerPoint decks didn’t apply to what their business unit did and that they didn’t have any time to work on their leader standard work.”

As Mike stopped for a minute to drink some of the wine that he had ordered, Sam thought to himself, “Sounds so different from the work we did with Leslie. Doesn’t seem like Lean Mechanics even cared about any of the problems each of the areas might be having. This just sounds like a cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all kind of thing. How could anyone expect that it could fit every area of NL Services—or any company for that matter? They are quite different, and the problems they have are different as well.”

Just as Sam was about to ask Mike to tell him more, Mike started up again. “And to make matters worse, the senior managers didn’t want to pay any attention to the lean experts that Lean Mechanics assigned to coach them after the training program was finished. The senior managers complained that the lean experts didn’t know anything about NL Services’ business and that the huddle boards, dashboards, and metrics that they designed for the teams to use didn’t make any business sense at all. No matter what the lean experts said or did, the senior managers just did whatever they wanted and didn’t seem to change at all. And since they didn’t buy in to the whole lean implementation, no one else did either.”

Mike sighed, leaned back in his chair, and took another drink of his wine. Then he went on, “Finally, after arguing with the senior managers for months, getting very poor results on our annual Employee Engagement and Experience Survey, and coming to the conclusion that we weren’t getting any real business results for our shareholders either, we decided to let Lean Mechanics go. After all the time and money we put into it, it certainly was an expensive lesson for all of us at NL Services.”

Sam thought for a moment and then asked, “And what do you think that the lessons were?” Mike finished his glass of wine, frowned, and concluded, “When we started the whole lean thing, we had such high hopes. After the work that you and Leslie did, all the managers and leaders in the other regions really seemed excited to give it a try. I thought it would be easy to get them to all do what they were supposed to do and put Lean Mechanics’s plan in place, but I guess it wasn’t as easy to get them to change after all. The biggest lesson was that deploying a plan is not like spreading peanut butter on bread. One size certainly doesn’t fit all in our case. The approach has to be tailored in order to grow competency in lean.”

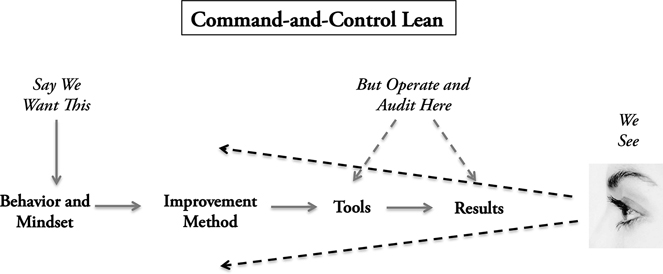

Why Changing Leadership Behavior and Thinking Is Difficult

Karyn has been a lean consultant for firms like NL Services, Inc., more times than she would care to remember. Her main contributions as a professional have been working to shift executives in service organizations from managing by command and control to leading the development of people. Over the years, she has found some common threads that seem to underlie the difficulties of changing leadership behavior. Let’s pause, look through the eyes of successful senior leaders who grew up in careers in command and control cultures, and consider what it is that would make them seem so insulated and hard to change.

1. Lack of Understanding of the Work Area That They Are Leading

Many of the executives and managers haven’t actually had any work experience in the area that they are leading; for example, one executive Karyn worked closely with (we’ll call him Bob) was promoted to a very senior leadership position, overseeing the operations of a number of regions. Bob had previously been in leadership roles in a variety of different support functions for the company, but the promotion was to lead a functional group that worked directly with the company’s most important customers. Bob had only a theoretical understanding of the department and the customers’ needs from his experiences in other departments. Although this might seem daunting, to Bob it wasn’t! There was never an expectation, by him or his superiors, that his leadership role depended on a deep understanding of how the work was done. His job was to make sure that his unit got the results it was supposed to . . . end of story. As long as he got results, nobody higher up asked or cared how those results were achieved, nor did anyone ask or care whether or not he had an understanding of how the work was done to achieve those results.

Karyn started as a worker in a call center and, and as a result of her experiences, always believed that as a consultant it was critical to understand her customers and the work their unit did. It seemed rather obvious. Yet it was anything but obvious to the leaders of the companies. In one company she worked with, ignorance of the work was almost considered a virtue: “Leadership is leadership.” If people had the potential to become a leader and aspired to it, they would be rotated broadly to get exposure to the company and would be expected to take any opportunity in any area of the company, regardless of their experience or understanding of the work of that area—and they would then be held accountable for results. It was common to hear executives say, “I don’t know how the work gets done, but it doesn’t matter, as long as we’re getting the results our shareholders need each quarter.”

Although this attitude might be acceptable in a command-and-control environment, in a lean organization developing people’s capability through the work they do is the primary responsibility of a leader. Executives with no experience doing the work find it extremely difficult to develop their people’s skills through doing, as they themselves do not know how to “do.” As our sensei, Dr. Deming, reminds us: “Management should lead, not supervise. Leaders must know the work that they supervise. They must be empowered and directed to communicate and to act on conditions that need correction.”

Karyn has been asked to support many executives like Bob. One might wonder how she could possibly move the needle to convince them to invest in understanding the work, let alone the customer. How can she get them to the gemba—to where the service representatives are creating the services that customers want and need? It is important to empathize. They are worried that the people they are supposed to be leading will see their lack of deep knowledge as a weakness. They may be embarrassed that it could become obvious that a frontline worker might know more than they do. After all, if they are the leader—and especially an executive—shouldn’t they be the one who knows everything? Karyn has seen many top-down, command-and-control leaders who are afraid that they will lose “control” if the people they lead can see their lack of knowledge about how value is created for customers. As we will see later, “convincing” is not a matter of telling them things, but rather creating a safe place where they can experiment and learn for themselves.

2. Command-and-Control Thinking Is Reinforced by the Executive’s Isolation from the Masses

Over the years, Karyn has noticed that many executives and senior leaders are physically located far from the people that do the work to satisfy customers and create results in their area. Their offices are in distant home office locations, or if they are actually located in the same building as the people they are leading, their office is still far removed from the gemba. Take Bob, for example. Although he sat in the same building as the people he led, his office was in a separate, walled-off, high-security area of the complex, labeled “Executives Only.” This may appear to protect him from the danger posed by the riffraff workers. In reality it is to provide an aura of power and control. Think about kings and their castles and the moats that surround them.

In Bob’s case, like many of the executives in services, he had always had a person reporting to him, such as an “operations manager,” whose job was to understand the work and manage the people who did it. Bob did not actually lead an entire organization. He led a small number of subordinates who acted as his eyes, ears, and hands. Bob’s main job was to hobnob with other executives in “important” meetings. This isolation provided Bob with comfort and affirmation—he was one of the chosen ones who were too busy to be involved with routine operations. Bob struggled when lean was brought into the company, and there now seemed to be an expectation that he learn the daily work that he had mostly bypassed in his own rise to the top. This was actually scary—leaving the safety of his walled-off “Executives Only” area to go and see at the gemba!

3. Being in the Same Old Environment Promotes and Reinforces the Same Old Habits

The lean initiatives that Karyn has supported have almost always started at the bottom or “service floor” level. Someone hears about how lean has worked in manufacturing or a similar service environment and decides to give it a try. It is robust enough that even the basic use of tools can produce initial results that get the attention of higher levels, who then decide to make lean a corporate program to be spread across the company. In these cases, although workers and managers who are closer to the front line develop some experience of working in the new, lean culture, senior leaders, and especially executives, are the last to go through the cultural change. And because senior leaders don’t directly provide customer service, there is often confusion about how lean applies to their roles.

This isolation is further reinforced by the way leaders are selected. In many organizations, executives and senior leaders have reached their positions by being promoted through the old boys network, or else they have been brought in from the outside by the old boys because they got results in a similar management culture. We talk about the “old boys club,” and like any club, the members identify with each other and reinforce their shared values and beliefs. This reinforces the same old habits, which gets the leaders rewarded since those giving the rewards think as they do. These habits are extremely entrenched and very hard to break. One senior executive who was determined to change himself as he learned about lean expressed his own frustration:

How can I change when I am in the same environment that encouraged these bad habits? Habits are so hard to change. As a leader, I know that I need to focus on our customers—theoretically—and I try to practice that—but then I spend the majority of my time in an environment that is the “old culture,” so I revert back to the old habits of how I thought and did things before. Then I do my best to pull myself out of that and I do something to try to get new habits started. Every day I have to work in the old culture environment, so the new habits just never seem to get going enough to get strong enough to overcome the old ones.

4. Most Old-Style, Command-and-Control Leaders Are Not Systems Thinkers

Most of the executives that Karyn has worked with over the years are not systems thinkers. They have developed a mechanistic mindset that seeks to optimize results, not interrelated people and processes. They are paid and promoted to make their numbers, and they look for the most direct path to getting there. Since these results are almost always financial, the most direct path is efficiency in their area, which leads to cost reduction. Simple formula; systems thinkers stay away! However, as we know, that siloed view is not good for the service organization as a whole, or for customers.

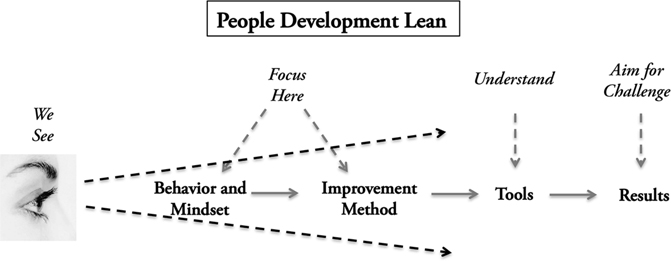

CHANGING LEADERSHIP BEHAVIOR AND THINKING

Some of the questions that we are frequently asked are about how to begin the process: “Where should our lean efforts start? Should we start with the executives right at the top?” Should we start with the supervisors and service providers in the gemba working directly with our customers where value is created? Or with middle managers? Which level of leadership should we start with first?” In our experience, the best answer, as we shall see, is to take a systems view and begin all together in one relatively self-contained area, as all parts of the system need to function together. The higher the level of leader you can engage in that pilot the better. To see how that can work, let’s check back in on Sam McQuinn and Mike Gallagher as they continue their dinner discussion.

Service 4U: Learning Lean Leadership by Self Development and Developing Others

“Mike,” Sam said, “sounds like you and NL Services have been going through a really rough time. And you’re right. It’s not as easy to get leaders to change their thinking or their behavior as it seems that it should be. You’d think that with all the money we pay them and all the skills that they seem to have, change would be easier for them. But it just doesn’t seem to be. We’ve noticed that some of our leaders are having problems changing and that some aren’t. It’s really interesting.

First we spent a lot of time trying to figure out if some of them are just more natural lean thinkers or if it was the environment they were in. Were the leaders that were involved from the beginning having an easier time changing? After a while, though, we realized that we couldn’t really figure it out, and that instead of spending more time trying, we just needed to find a better way to get all our leaders on board. Improving for our customers is the most important thing for us at Services 4U, so we need all our executives and managers to be able to lead in a way that helps the whole organization improve.”

Mike nodded and laughed, “I agree. You’d think with all that money we’re paying them, our execs would be really motivated to change to the new way. But obviously they aren’t! And I’m tired of trying to figure out why. If you don’t mind my asking, have you made any progress with Service 4U’s leaders?”

“Actually we have,” said Sam. “And I don’t mind sharing how. It’s not a secret. After Sarah Stevens and I determined that the areas that were really surging ahead in satisfying our customers and improving business performance were the same areas that had leaders who were acting in the new lean way, we realized that we had to try something new. So we reached out to Leslie Harris, who recommended we work with a colleague of hers, Dennis Garrett. Dennis is really into something called Toyota Kata, and since we’ve started working with him, our leaders have made remarkable progress developing themselves and others. And the progress is showing in their business results too. Funniest thing is that many of them have even started calling themselves what Dennis refers to himself as—a kata geek!”

Mike was impressed by the enthusiasm and excitement that he heard in Sam’s voice. “Wow,” he said, “there really must be something special in what Dennis is doing with your execs if he’s getting that kind of response from them. As I said, we couldn’t get ours to give the Lean Mechanics’s lean experts the time of day. What’s Dennis doing that’s so different?”

Sam thought for a moment, and answered, “At first, we were a little skeptical about his approach, but Dennis has really gotten our executives thinking in a different way by actually having them do things differently right away. Dennis doesn’t have people go to training classes, and he doesn’t use long PowerPoint decks. In fact, he doesn’t usually use PowerPoint at all. Just simple charts and graphs that people can fill out with pencil and paper, right in the area where the work is being done on a kata storyboard. He’s simply teaching our executives how to act differently by getting them to act differently. And that seems to be changing how they are thinking. I know it sounds strange, but it’s really not as complicated as it sounds.”

Mike Gallagher shook his head. “I don’t really understand,” he said. “Changing execs’ thinking by changing what they’re doing? What are they doing that is so new and different?”

“I’ll tell you,” said Sam. “During our first meeting, Dennis explained to Sarah and me that one of the problems that a lot of lean consultants have is that they try to get the whole organization going all at once. Just like Lean Mechanics. In Dennis’s experience, though, that doesn’t work because leaders don’t know how to lead in the new way. Dennis suggested that we start working in one of the regions that wasn’t progressing as well, with one of its leaders. Dennis went to visit some of our leaders and took a look at their sites, and then we decided that we would start with Maria Diaz, the service leader for the Northeastern Region, since that region seemed to be lagging the farthest behind.

Dennis insisted that Maria go with him to visit the operation’s site and explained that they would choose one small part of the operation to work on: the part that was having the most difficulty, and they’d set a challenging goal for this one part to work toward. Dennis explained that he would be teaching Maria a very basic method of improvement and wanted her to personally lead the effort.

At first Maria was hesitant. She complained that she was too busy to personally lead such an effort, especially in such a small area with such a limited pay-back. Dennis explained that to lead a transformation in leadership she needed to go first and develop her own capabilities. Learn to do before you learn to teach others. Dennis explained that he would be playing the role that he eventually wanted Maria and all her managers to play—coaching Maria to lead improvement toward a challenging goal. Dennis and Maria went to the site at least once every two weeks and, step by step, Maria led the team onsite toward the goal she needed them to achieve. The improvement kata itself is pretty straightforward: set a direction, understand the current condition, set your next short-term target condition and then go crazy experimenting! But following it without skipping a step takes a lot of discipline.

At first, it was hard to get Maria to go, but once they got into a routine and Maria realized that Dennis was going to be right beside her helping her learn how to lead in this new way, things really took off. In fact, she says that she can’t remember having so much fun at work in decades. Now she and Dennis are working on a plan for teaching other managers at that site how to coach their teams to improve.”

Sam stopped there. He could see from the perplexed look on Mike’s face that Mike was confused about something. “Sam,” said Mike, “that all seems well and good, and it’s great that Maria’s behavior really seems to be changing. But doesn’t it seem like it’s going to take a long time to get all parts of the company going? And that’s going to slow down the results. How are you going to get the CEO and shareholders to buy into that?”

Sam nodded. “I know what you mean, Mike,” he said. “We struggled with that too. We wanted to go faster, but Dennis convinced us that faster isn’t always better. He told us that if we didn’t spend the time to build up our leaders’ capability to lead improvement, then learn to coach others to do the same, we would resort to quick fixes that are not sustainable. We like to think we can change people’s minds by just telling them what to do, but Dennis showed us that the way to change leaders’ minds so that they do things differently is by teaching them how to do those things differently, through repeated practice. It is common sense that you can’t teach something that you yourself don’t understand. Yet we expect our leaders who have no skill in lean thinking to teach others how to be lean leaders.

Now Maria and the site manager of the Northeast service area are working with a couple of other ‘slices,’ what Dennis calls a process and its associated chain of people, in the Northeast. As those people learn, they’ll be able to branch out to other areas in the Northeast. And although it’s going a little more slowly, the business results are really improving, and the leaders are raving about how engaging it is to learn this way. Before this, we had trouble getting a lot of them to go to the gemba to see how the work is done, and now we’re having trouble getting them to stay away! I wouldn’t have believed it myself if I hadn’t seen leaders acting in new ways and seen the business results, with my own eyes!”

Mike leaned forward in his chair, gazing intently at Sam. “And let me guess,” he said. “I bet that they’re actually going to solve the problems each area is having specifically, not just setting up a cookie-cutter set of tools that the areas don’t want to use.”

“Absolutely right,” Sam answered. “Each of our business areas has its own set of challenges and obstacles to overcome. And now that their leaders are going to see how the work is done to get results, they are learning how to help coach and guide people to solve those problems. Things are improving for our people who do the work, our business, and, most importantly, our customers. And best of all, leading this way is becoming just what our leaders do now!”

“Sam,” said Mike, excitedly, “it seems like Service 4U is doing things the ‘right’ way for its customers and leaders. I’ve been so discouraged that ‘lean’ didn’t work out at NL Services. I was worried it couldn’t work anywhere. But what you’re doing is totally different—and I believe it’s got great potential for positive change for your customers and your people. You don’t suppose there’d be a place for me at Service 4U, do you?”

Coaching Tips for Executives (and Others!)

Over the years, Karyn has been able to go beyond finding some common threads that seem to underlie the difficulties of changing leadership behavior. Karyn has found ways of working with and coaching executives and other leaders that have been successful. It’s not easy, but with time, patience, and persistence, habits of even senior executives, can—and do—change! Here are some of the tips and tricks that Karyn has learned.

1. Start with a Plan, Then Adapt to Your Learner

In Karyn’s experience, there is a fatal flaw in the coaching philosophy of many of the companies she has worked with: letting the executives being coached choose what they want to work on and how they want to be coached. Lean coaches will go to the leaders and ask them to fill out a self-evaluation form and decide which lean tool they would like to focus on learning to use. The problem with this is that without any lean experience, and often without a real commitment to learning, there is no way for the leaders to be able to picture what it is they need to do differently or how to develop the different skills needed as lean leaders.

Think about a coach for a football team. Does the coach ask each player to decide what skill he would like to work on practicing? Or does the coach watch the individual players carefully, as they practice and as they play with the team, to determine where they need to improve? Some players might need to improve the percentage of time they catch passes. Others might need to improve their leverage in blocking the opposing players. Once the coach has determined what each player needs to work on, he tells the player and creates a plan so that the player can practice the needed skills, not the other way around!

If you are the lean coach for an executive (or other leader), you need to think of your role as if you were the coach of a sports team. First you have to spend time with the executive to understand where she is in her thinking and practice. You have to spend the time to clearly grasp the current situation: does she ever go to the gemba to see? If she does, is she really looking and seeing, or is she “checking the box” that she’s gone? Once you have determined what her “current condition” is, you need to decide the direction: where does she need to be in the next six months to a year. What’s the challenge statement for that particular executive? Then the statement has to be broken down into successive target conditions, and a plan needs to be put in place for what the executive needs to do to reach each successive target condition. This sounds like the improvement kata, but applied to developing a coach. This can and should be done collaboratively with the leader, but the coach must coach!

2. Do Something Differently with the Execs You Are Coaching

And a big part of that plan has to be how to get the executive you are coaching to do things differently. As explained earlier, most executives have deeply entrenched habits from being rewarded for doing things the same top-down, command-and-control way for many years. In order for them to start to develop new, lean leadership habits, it is imperative that you, as their lean coach, get them to do things differently—as soon as you possibly can. It’s not easy, but the sooner you find a way to get the executive you are coaching to do something differently, the sooner you will see his thinking start to change.

For example, one of the hardest things is simply getting executives to go to see how value is created for their customers. Over the years, Karyn has found that the best way to get executives to the gemba is by simply refusing to have coaching sessions in their office—or even in the executive area. Karyn schedules all coaching sessions in the gemba because she knows that if the coaching session takes place in the person’s office, where he is comfortable and familiar and old habits are in full force, no new learning is likely to take place. And if an executive refuses to come to the gemba and insists on meeting in his office, Karyn will lean against the door and invite him to go with her to the gemba. Once they are there together, Karyn will question the executive to guide him to grasp the current condition so that he can learn what she has planned for him to learn.

There is an old saying, “Learning hasn’t occurred until behavior has changed.” If you want your executives to learn—to change their thinking—then you have to get them to change what they are doing first.

3. It’s Okay if Your Execs Show Signs of Being Uncomfortable While They Are Learning

Just like any other person, executives feel uncomfortable learning new ways of doing things. Think about it. If someone asks you to do something in a way you aren’t used to, let’s say speak to someone in a foreign language you are just learning, you’re going to feel uncomfortable. You might argue with the person who asked you to practice your new language skills, or you might try to find a way out of speaking to the person. Feeling uncomfortable or scared usually causes us to behave in “fight-or-flight” ways. Because our brain wants us to stay safe, it makes us feel uncomfortable in situations where we might not know what to do. So if we are happy and know what to do, we are comfortable. The problem is, if we’re comfortable, we’re not learning. All learning takes place outside our comfort zone, past what Mike Rother calls the “threshold of knowledge,” in the uncomfortable “learning zone.” And since we need the executives to learn, although it might seem counterintuitive, the best thing we can do for them is make them feel uncomfortable.

In many of the organizations that Karyn works with, people do not want to make executives uncomfortable in any way. Karyn often hears complaints from lean coaches that a session didn’t go well because the executive was negative or grumpy. Karyn has even had executives shout at her when she has asked them to do—or even think about—something that is outside their comfort zone. And although it seems counterintuitive, when Karyn hears frustration or grumpiness in executives’ voices or sees that the execs are trying to leave the situation (yes, Karyn has actually chased down executives who are attempting to flee because they are feeling uncomfortable during a coaching session!), she is encouraged. She knows that they have left the comfort zone and are in the learning zone—where they are ready to learn—and exactly where she wants them to be! In Karyn’s experience, learning = uncomfortable.

4. Stay with Your Execs While They Are Learning so That You Support Them in the “Uncomfortable Zone”

Now, once you see, by their behavior, that your executives are in the learning zone, the most important thing is to stay with them while they are uncomfortable. Again, think about the coach of a sports team. Once the coach has determined what the players need to improve and creates the schedule for them to practice those new skills, does the coach leave the players to struggle through practicing on their own? No, the coach certainly does not. She stays with the players, running right beside them if necessary, encouraging them and supporting them as they learn—every step of the way. This is exactly what needs to happen when coaching an executive. Executives are, first and foremost, people; and like all people, when they do not have confidence—which can be gained only from mastery through doing—they need support.

In Karyn’s experience, many lean coaches do not understand this. And since they do not recognize the executives’ discomfort as a sign that they are in the learning zone and need support, the lean coaches often do exactly the opposite of what is needed: they leave their executives alone when they are most vulnerable! Again, although it seems counterintuitive, what Karyn has found works best is to stay with the executives once they are in the learning zone. Instead of reducing contact, find ways to increase contact time so that the execs feel supported and cared for while they are learning new ways to behave and think. Spending extra time with the executives, so that they can ask questions and try things out under the watchful eye of their coach—who already has experience and confidence—builds a relationship of trust and caring. And in Karyn’s experience, once that relationship is built, the executives will be more willing to try new things in the future because they know they will be safe, under the watchful eye of their coach, while they do!

5. “Whisper in the Leader’s Ear . . . ”