4 Living in the Cloud: The Place to Hide and Store Mobile Data

The first thing to know about the mysterious Cloud is that it is really not that mysterious. Understanding the Cloud comes down to understanding the simple concept of cloud computing. In a nutshell, the Cloud is essentially a server, large or small, that is remotely accessed by another device—a computer or terminal that sends information to and receives information from the remote server.

The first “cloud computing” scenario was created in the 1950s; it simply allowed access to large servers and computers (mainframes) in data centers by dumb terminals on users’ desks, so that users and businesses did not have to purchase complex computers for every employee. This progressed into using a single server in the 1970s, with multiple instances of an operating system and storage area using virtual machines instead. In this scenario, an entire company could have an instance of a virtual computer running on a single remote server, and even different types of operating systems. Quite honestly, this concept from the ’70s with server space to run software, provide storage, and offer data reception and transmission is what we see today in everyday apps like WhatsApp, Facebook, Line, Snapchat, and more. Data transmitted to the remote server (on the Cloud) is stored and accessed by the app on the mobile device, as well as the data transmitted to the remote server from the mobile device. Instead of cloud computing, this is often termed cloud services or cloud storage.

A recent document showed the data center storage capacity worldwide in 2018 was 1450 exabytes (www.statista.com/statistics/638593/worldwide-data-center-storage-capacity-cloud-vs-traditional/). If you’re not sure what an exabyte (EB) is, it’s large: an EB is 1 quintillion bytes, or a 1 followed by eighteen 0’s: 1,000,000,000,000,000,000. (To put that in perspective, Mars is 34 million miles away and Jupiter is 353 million miles away. That means a person could take 14,705,882,353 round trips to Mars from Earth, or 1,416,430,595 round trips to Jupiter, before they reached 1EB—let alone 1450EB!) A mind-blowing number of 0’s and 1’s are stored in data farms around the world. The storage of third-party data from applications on a mobile device is similar, and to save space, store data, and make the user experience better, the Cloud provides the answer.

The problem posed by the Cloud to the investigator is simple: What legal grounds does the investigator have to access the information from a cloud service? Chapter 5 discusses a legal argument that can be made when discussing search warrants and who really owns data. Investigators must understand how relevant the data from cloud services can be to their investigations. Moreover, they must comprehend the various methodologies of collecting information from cloud services, the types of protection used, the accessible data, and the tools available.

Clouds and Mobile Devices

Storage on a remote service is nothing new in the computing world. What brought the concept to the forefront was not the 2014 movie Sex Tape or the 2018 movie In the Cloud, but the use of mobile devices. In 2008, Gartner predicted that the Cloud would be mainstream in two to five years in its hype cycle diagram, posted by TechCrunch (https://tctechcrunch2011.files.wordpress.com/2008/08/gartner-hype-cycle1.jpg). As people began to use more and more software and services via the Internet, the use of mobile devices has brought this concept to the masses (sometimes without them even knowing it).

Most people understand how Dropbox, Google Docs, OneDrive, or any other file storage/saving service operates in the Cloud. If a file can be stored off a local device and in the Cloud, it must be a cloud application or service. But what about apps such as Chrome, Telegram, WhatsApp, Viber, and Messenger? Should these be considered cloud applications, even if they do not offer storage services like Dropbox or Google Drive? Of course, they should! Messaging apps store and offer their services via remote servers (aka the Cloud) to users.

If the discussion is about native mobile app or cloud mobile app, however, there is a difference between the two, which comes down to development particulars. A native mobile app’s running environment is the mobile device, while a cloud mobile app uses a cloud server as its environment. The native app does not have to utilize a built-in browser to display the contents of the app, while the cloud-built app must rely on a built-in browser to display the app by using HTML 5, JavaScript, Cascading Style Sheets version 3 (CSS3), and a server-side code base. However, both types of app development styles can, and do, use the Cloud for user data storage, computations, and other needs.

If you’re unsure about whether an app uses cloud services, here’s an easy test: If the app is installed to another device, or even uninstalled from the device, when it’s reinstalled, are all the app data, settings, and other user information still visible in the app? If so, the app is using the Cloud to store data. Furthermore, if a login and password or other authentication is used to start the app, or if the user must log into a web-based system, chances are the data is stored on the Cloud.

What Does This Mean to Investigators?

Once, investigators had to deal with data coming only from the physical mobile device. Data such as messages, contacts, call logs, images, apps, and more was retrieved from the mobile device by following a process and procedure (such as isolate, attach, extract, examine, report) to complete the task. Investigators had what they needed to finish the investigation and close the case. Training teams from various companies taught the in’s and out’s of processing the device in a forensic manner so that the information could later be used in testimony.

In 2011, when Apple brought to market the ability to store a device backup in the Cloud via iCloud, the world changed. Android, in an effort to keep up with security and Apple, released version 6.0, which forced the device’s user data to be encrypted. Devices became more secure by increasing security with passwords, biometrics, PINs, and so on, and app developers began to impose security on their apps, eliminating the inclusion of the main app database from the backups. Since creating a backup of a mobile device for iOS via iTunes protocols and Android via Android Debug Bridge (ADB) protocols was the primary way commercial tools conducted an extraction, things became a little more difficult.

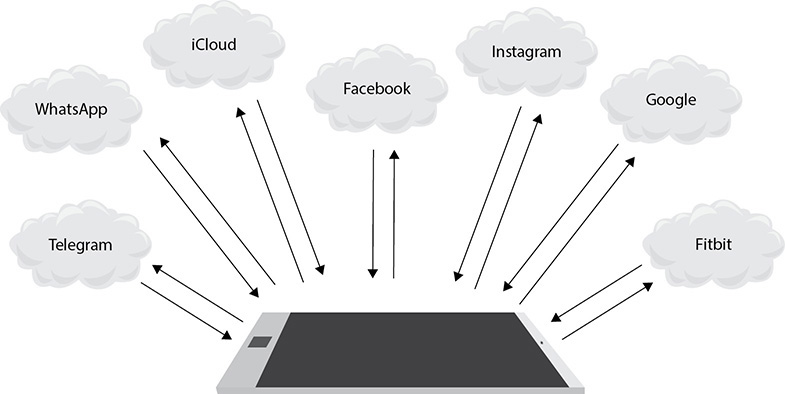

For Android, trying to obtain a complete physical extraction of the user data is futile if the device is fully encrypted. Today, the importance of cloud data in mobile device examinations cannot be overlooked. A single device can have multiple connections to various cloud sources simultaneously (Figure 4-1). Most apps on today’s devices use cloud storage, as do the device manufacturers.

FIGURE 4-1 Smart phones today have many simultaneous connections to various cloud services.

![]()

As with all other methods discussed throughout this book, any investigation should be conducted in a lawful way that abides by all state, local, federal, and international laws. Utilizing tools or methods for the invasion of privacy, or accessing cloud services without legal paperwork or consent, is illegal.

Today’s digital investigators should not ignore the significance of the data stored in various cloud services. Without cloud data, the information that can be gathered from traditional sources (such as mobile device, flash media, or computer) is limited, inconclusive, or simply unobtainable.

No Device Needed

One of the immediate benefits when performing a cloud investigation is the fact a mobile device is not even needed in many cases. All that is needed, other than legal authority, are authentication credentials to the various cloud accounts. Think of the benefit the Cloud offers when a device has been damaged so badly that no customary method can be used to extract data from the device. Also, if the device cannot be located, is lost, or has been stolen, access to the cloud backup or apps is still available. How about if a device owner is missing, lost, or kidnapped, with the mobile device in his or her possession but it’s disabled or out of power? By extracting data via the cloud services of the user’s various accounts, investigators can obtain location information or other data, which offers immediate benefit to the investigator—and the victim.

Encrypted or Locked Device

With devices from Apple, to the entire Android line of more than 25,000 devices, investigators can encounter several problematic issues. The device can be locked, encrypted, or both. If an Apple device is locked with a PIN, some current options using GrayKey devices can unlock the device, but with Apple’s insistence on shutting down these methods, this advantage might be a short-lived win for investigators, as standard mobile forensic methods will no longer work. With Android devices, investigators face the same conundrum: if the device is locked with a PIN and a locked bootloader, or the device data is encrypted, traditional methods and standard mobile forensic extraction may not work.

Access to the data within the Cloud, however, is still available and accessible by the investigator independent of the status or configuration of the mobile device. Essentially, whether or not the device security or encryption is enabled, investigators can extract data from the cloud services used by the mobile device, third-party apps, or the actual device backup process.

Corroborate and Collaborate

Often in investigations, an examination offers two sides of a story. One side may be a person who is using a mobile device to stalk, harass, intimidate, and bully another person; the other side is the person being stalked, harassed, intimidated, and bullied by means other than a mobile device, such as via desktop Facebook or desktop Messenger, who does not own a mobile device (yes, it can happen). By accessing the data from the cloud services of both subjects, along with the mobile device data, the investigator can paint the entire picture. Having the ability to extract information from cloud services for today’s investigations is critical.

Disposal of Evidence

Many investigations today involve the subject wiping the device in an effort to remove the “smoking gun” on their mobile device. The devices of today, unlike devices of the past, do a good job of permanently removing data from flash memory with a factory reset and new OS installation. However, as mentioned, third-party app developers want their users to be able to reset their devices and subsequently persist their data. To the investigator, this means that the data that was on the device at the time of the crime could possibly be located in a backup on the cloud storage for the device and/or the app. Of course, accessing the cloud store and services often takes the cooperation of the owner of the device or the cloud service provider. This limitation, however, should not preclude the investigator from attempting to access this valuable data.

Additional Data

App cloud storage as well as cloud backups can contain additional data not available on a standard mobile device extraction completed by an available commercial tool, including physical invasive acquisitions. As an example, Apple iCloud backups can include three backups of a single device—the current backup and two historical backups. Imagine a scenario in which a subject resets the device and the device is backed up to iCloud, but unbeknownst to the subject, the backup performed the night before still is available to be retrieved. Apple indicates that the backup is an incremental backup, but using commercial tools to extract iCloud devices proves otherwise. Additionally, services such as Samsung Cloud, Dropbox, Google Services, WhatsApp, and several other apps cache and store deleted records, including messages and pictures in the cloud store, which is not synced or stored on the physical device. Conducting a robust extraction of the physical device is a must, but what might be missing or additional to the data stored in the devices are multiple cloud storage services.

Accessing the Cloud

Once the investigator decides to access the data from a cloud account and proper authority has been obtained, several considerations remain. For example, the investigator must determine the appropriate date or date range of the data, as well as the types of record he or she needs to investigate. The investigator must also understand the security methods of the cloud account, which can be user driven, a cloud service set, or a combination of both. These methods vary per service, app, and device at times. Finally, an investigator must be aware of the notification settings of the cloud services being accessed.

Date Ranges and Types of Records

In most investigations, the event in question and under investigation occurred at a certain time and on a certain date or range of dates. Having a tool in which the investigator can enter the range of appropriate dates will enable the data to be within the scope of legal paperwork and limit the amount of data that is extracted. Consider a WhatsApp cache of 300,000 messages, which would take about eight hours with most commercial tools to download. Many services store a variety of records (such as images, videos, audio, documents, and text). If the investigation is based upon a particular date range and involves only images, messages, or videos, a tool can be used to select the appropriate date range and type of data. Using a date range or data type to limit the number of records to be extracted can dramatically minimize extraction time and better serve the investigation requirements.

Notifications

Accessing a cloud service as part of an investigation is not as straightforward as entering a few usernames and passwords. Cloud services, particularly Google, can notify users of access to accounts that are deemed suspicious, not from a recognized device or based on time elapsed. In 2008, Google began notifying its users of IP variations in access to their accounts. If multiple devices are connected to a Google account in Alexandria, Virginia, but an IP address is used in Frankfurt, Germany, the owner of the account is notified. The owner can accept or deny this access. The device and operating system, along with the IP, are displayed to the user via the Google account. Investigators must take notifications into consideration when using tools to access the cloud account. If the investigator is attempting to access a subject’s account covertly as part of an investigation, he or she must understand whether the subject will receive service notifications from the app.

Security

Cloud accounts can use various forms of security, such as authenticating via a username and password combination, using tokens or biometrics, and data encryption. To access the data within the Cloud, the investigator needs to offer authentication, and in some instances a second type of authentication in two-factor authentication (2FA). The encryption of the data on the server that is extracted can often be decrypted with the authentication method once the investigator identifies the type of encryption in use. The type of authentication used by the cloud extraction tool will also determine whether a secondary authentication type is required by the app.

Two-Factor Authentication

Two-factor authentication uses two types of authentication to “positively” identify the person requesting access. It has become the de facto authentication type in many mobile apps. Google introduced 2FA in 2011, and today the easiest form of 2FA with mobile devices involves receiving a Short Message Service (SMS) or phone call to the phone on which the app is installed.

Multifactored authentication adds security to a user’s login by requesting additional information, which can include the following:

• Something you know A password, PIN, or other knowledge-based question only the user would know. This would be the simplest form of authentication and is often the easiest to bypass.

• Something you have Represents a physical item such as a fob, hardware token, RFID card, smart phone, and so on. Think of a chipped credit card: the PIN is known to the user, and the card is in his or her hand. The PIN must be entered along with the card and chip.

• Something you are Represents something that is integral to the person, such as biometric data—the person’s iris, fingerprint, palm print, or retina, for example. This represents one of the most secure forms of security when used in conjunction with something the user has.

Multifactor authentication can present problems with cloud extraction utilities, but there are ways to create a backup if it is enabled. In fact, in 2018, a report in the Verge claimed that 90 percent of people using Google services still did not use 2FA (www.theverge.com/2018/1/23/16922500/gmail-users-two-factor-authentication-google), so perhaps lots of data can be extracted without a second form of security.

Username/Password

Username and password combinations make up the most common method of logging into app and cloud services. Many commercial tools can be used to extract username and password information from the mobile device (such as Apple Key Chain, Android Accounts.db, Android apps), and these can be used to access the user’s cloud services. There are, however, disadvantages to using only a username and password to access user data, including notification to the account owner, as well as triggering 2FA.

Authentication Token

When a user authenticates successfully to an app or cloud server, the service returns a token, which is used to enable the user to access the service without having to enter his or her username and password again. A token is like a pass, and it is used, for example, when you open your Gmail account and it logs you in without requiring any interaction from you. Most tokens have an expiry set at the time of authentication, which varies per app or cloud server. Some are good for a single session only, others for two weeks, some for 30 days, and some forever if the user uses the app on the same mobile device.

Commercial tools enable not only the collection of usernames and passwords but also authentication tokens used during the extraction process of a mobile device. The advantage to using the authentication token rather than the username and password is that the account owner will not be notified of the access and 2FA is bypassed.

Methods of Bypassing Cloud Services Security

An investigator can access a cloud account with built-in services by accessing the account directly. As in any investigation, all processes and access to the mobile device, computers, and cloud storage must be backed by legal documentation. Without the required legal documentation, any information that has been extracted will be considered tainted and unusable in court. Discussed in the following sections are some methods the investigator can use to obtain credentials to bypass the requirements of a username, password, and 2FA.

iCloud Bypass

Apple iCloud is used for the backup of both the Mac and associated devices such as an iPhone and iPad. The devices that share iCloud are termed “trusted devices” and can receive a code for the 2FA requirement to access the devices’ iCloud account. The investigator can also use a code generated on one of the trusted devices to satisfy this requirement and start the extraction.

If the investigator chooses to send the code to the trusted device, the device must be online and not in an isolated state. This must be documented by the investigator, because allowing the device on the network could cause the device to receive data (such as iMessages, app updates, and so on), to remote wipe, or to perform some other operation. There is perhaps a better way to get the code, however.

Apple allows the user of the device to obtain a code for the device either online or offline. To access this setting on an unlocked, trusted iOS device, go to Settings | [UserName] and Passwords & Security. When the phrase “Account Details Unavailable” is shown, select Get Verification Code. If the trusted iOS device is not available, a trusted Mac in the ring of trust can also be used. On the Mac, click the Apple icon at the top left, and then choose System Preferences | iCloud | Account Details. If the device is offline, select Get Verification Code; if it’s online, select Security | Get Verification Code. This code can be used for the 2FA request.

Google Bypass

Like Apple, Google can use several types of forms when 2FA is enabled. The Google account holder can create app-specific passwords or use the Google Authenticator to bypass the 2FA requirement completely, and a user can even create a set of one-time use codes. An investigator can also receive a SMS message onto the device, which of course would mean the device has to be online—or, if using a UICC card, the investigator can place the card in another unlocked mobile device or in one with the same service carrier.

Within the Google account (myaccount.google.com), go to Sign-in & Security | App Passwords (required to enter password), and then under Select App, select Custom and then the device in Select Device. Tapping Generate Code will create a unique password that you can use along with the username within the cloud extraction application. This will bypass 2FA, even if it’s enabled. All changes within the account are logged to include the event, date/time, and location.

Also, Google allows the use of one-time backup codes to be generated. Once a backup code is used, however, it becomes inactive and cannot be used on subsequent extractions. To obtain backup codes from an account, go to the Google account (myaccount.google.com), and then Sign-in & Security | 2-Step Verification (required to enter password), and then Backup Codes and click Show Codes. Enter the code in the cloud extraction tool when requested.

Google Authenticator is available for both iOS and Android devices. An investigator should determine whether the app is installed on the device, which will indicate that the user has already set up Google Authenticator in the 2-Step Verification area. If the app has been installed on the device, simply open the app, and use the six-digit number in the cloud extraction application when it is requested.

Bypassing the security for cloud services often goes against the guidelines of device isolation in some instances. Investigators may need to receive a text message or call on the device if multifactor security is in use. In these cases, the investigator must document the steps that have been taken as well as any data that was delivered to the device. Similarly, the investigator should document the process and procedure regarding how a verification code or authentication code was used to bypass 2FA.

Accessible Cloud Data

The information an investigator can extract from a cloud store depends on the app data being extracted and also the product that is used to conduct the extraction. Tools that extract data from cloud store rely on the APIs that are used by the actual apps. To support online cloud storage, commercial tool companies rely on research and development of the communication between the app and server as well as documented research online. This is a slow process and is often hampered by app development teams that continue to change API and data stores to combat the access. It is truly a cat-and-mouse game between the forensic tool developers and the app development teams. Add 2FA to the mix, and access becomes even more difficult for the examiner.

Again, what data is accessible in cloud store will be based upon the available cloud storage API that the software extractor uses. Tools are continually updating the service to keep up with changes by app developers and newly identified access points.

The next sections cover accessible data and extraction information from iCloud, WhatsApp, Fitbit, Facebook, and Google My Activity.

iCloud

The accessible data for iCloud includes the following, as listed in Apple Support (https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT207428):

• App data

• Apple Watch backups

• Call history

• Device settings

• HomeKit configuration

• Home screen and app organization

• iMessage, text (SMS), and MMS messages (11.4)

• Photos and videos on the iPhone, iPad, and iPod touch

• Purchase history from Apple services, such as music, movies, TV shows, apps, and books

• Ringtones

• Visual Voicemail password (requires the SIM card that was in use during backup)

Within the iCloud backup is app data, which is often extracted separately from the main iCloud backup, typically because the data is encrypted by the third-party app and must be decrypted with another 2FA code. For example, WhatsApp data within iCloud is extracted using the username and password for the iCloud account, and then a verification code must be entered for the extraction. However, after a successful extraction, the investigator will receive a call or SMS message to obtain another authentication code that must be used to decrypt the data that was extracted.

Fitbit

Accessible data from the Fitbit cloud store includes the following:

• Activity logs (daily, lifetime, recent, favorite, goals)

• Body composition (fat, weight, goals)

• Device (devices, alarms)

• Food and water logging (meals, recent, custom)

• Friends

• Heart rate

• Sleep

• User information

• Subscriptions

• Dates and times of measurements

Many commercial tools can be used to obtain some of the information from the apps on the device with few actually accessing the data from the Fitbit cloud service.

Data that can be collected from the cloud accounts of Facebook users includes the following:

• Groups (participants, posts)

• Profile

• Friends

• Albums

• Time line

• Messages (attachments)

If a user authorizes Google to authenticate his or her Facebook account, the user’s Google credentials can also be used to extract the data from the Cloud. Furthermore, any account connected to Facebook, such as Instagram, Map My Run, or Endomondo, can also be accessed with the Facebook credentials to extract their cloud data. The caveat to this type of login to a different cloud store is that only the data Facebook has permission to access will be available to be extracted.

![]()

You can use another method to download all of the user’s data if access to their account is available. In General Account Settings, choose Download A Copy Of Your Facebook Data. The output is more tedious to wade through, but this is still a viable option.

Google My Activity

In 2016, Google launched My Activity. This cloud service captures a tremendous amount of data and can provide a wealth of information for any investigation. My Activity can be disabled by the user. The data that can be collected includes the following:

• Web searches

• Web sites visited

• Time line with GPS coordinates (any signed in device tracks via pictures, known location)

• Map data (routes, viewed area in map)

• Device information (calendar, contacts, battery level, music)

• Applications (Google Play)

• Call and Message information (if using Google FI or Google Voice service)

• Voice and audio

• Gboard (Google Keyboard) voice input (entire phrase from any app can be found as well as audio)

• Google Assistant (Google Home, app) stores entire phrase in activity as well as audio

• YouTube (searched, watched, comments)

• Preferences (news, orders, movies, books)

• Casts to Chromecast (what was viewed)

The cloud service, and the items listed here, are available with authentication of a Google account. The Google Home device’s activity is also available within the Activity module, which was covered in Chapter 3 and will be further discussed in Chapter 16. The information that is stored within this cloud store is unbelievably verbose and a complete treasure trove for investigators. Some investigators have utilized Google Takeout to extract the user’s Google activity. Using this method should be conducted cautiously, however, as the user is notified immediately of the collection of the data.

Cloud Tools

A variety of tools can be used by the investigator to extract cloud data. Like any other tool, each has its particular pros and cons. Most of the competitive commercial mobile forensic tools provide cloud extractors usually as additional tools that must be purchased in addition to the main tool. In this section, both commercial tools and open source tools will be covered.

As a mobile phone investigator working with today’s devices, you need a clear understanding of the capabilities in obtaining cloud data by each service. As mentioned, 2FA and even multifactored authentication are not supported by all available tools, which could pose a limitation. Also, the breadth of coverage for the cloud stores, and the type of data that is extracted from a cloud service, can pose particular issues.

In addition, it’s important to know whether the cloud extraction tool allows for a subset of the data, as well specific data based on dates, to be extracted. Think of the importance of allowing an investigator to extract only a subset of the data. Suppose, for example, that the scope of a search warrant dictates that only images can be recovered from a cloud service. The ability of the investigator to select only images during extraction should be a consideration when choosing a tool. Or perhaps an investigator must extract data based upon a particular time period; this can also be critical when selecting a cloud tool. By setting date parameters for the data within the cloud store, the investigator can accomplish a couple of things in a variety of use cases: this would allow an investigator to receive and view only the data specified in a search warrant, and with large data sets, an investigator could target the event time and extract and view only this data, saving valuable time.

The following sections are dedicated to discussions of various commercial tools from Oxygen Forensics, Cellebrite, and Magnet Forensics. The information provided does not cover how to use the tools, but covers their functionalities and some of their limitations.

Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor

The Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor is built into Oxygen Forensics Detective. The benefit of this solution is that the cloud tool is built into the software—it’s not an additional product that must be purchased separately. This enables the investigator to build cases not only from just the data on the mobile device and removable media but also data from the cloud that is related to the examined mobile device.

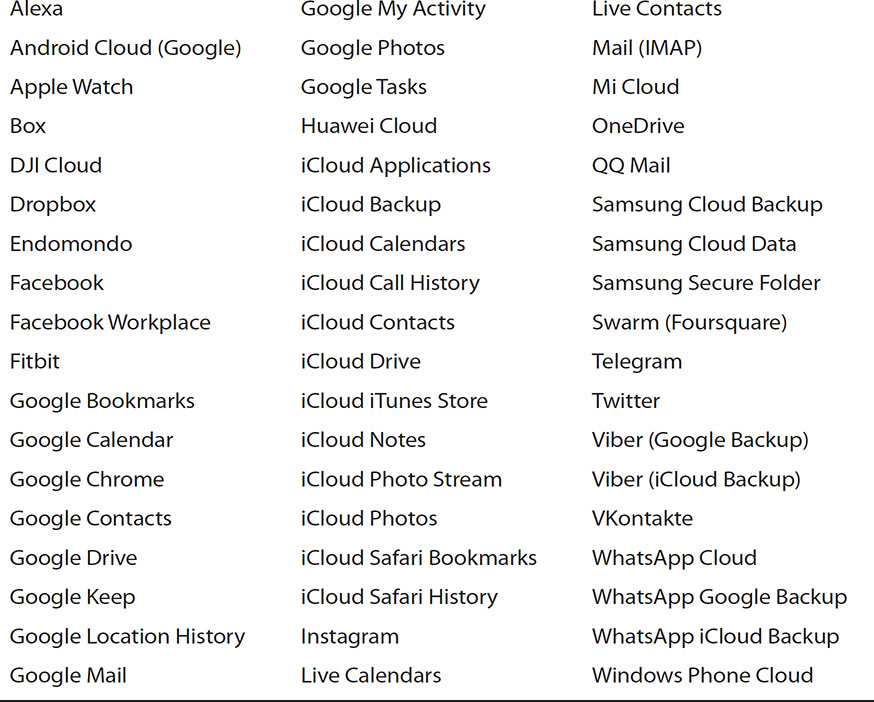

Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor supports, at the time of writing, 54 different types of cloud services, ranging from file storage, to messengers, drones, health apps, and social media. The main software, Oxygen Forensics Detective, extracts usernames and passwords during the mobile device extraction from iOS and Android devices that can later be used to attempt to validate the credentials to extract the cloud service data. The investigator can export a credential package from Oxygen Forensics Detective to be used in the Cloud Extractor on a computer that is online, or simply launch the Cloud Extractor from Oxygen Forensics Detective with the credentials that have been extracted.

The various cloud services currently supported by Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor are listed in Table 4-1.

TABLE 4-1 Currently Supported Cloud Services in Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor

Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor enables the investigator to use usernames/passwords and tokens to validate the account. Also, if 2FA is enabled for supported cloud services, the investigator is notified and several options are provided to the bypass the additional step. The steps are determined by the settings for the cloud service. An SMS or a phone call, a validation code, backup codes, captcha, or even authenticator code can be requested after the first validation of credentials. Each service can be different and can use two distinct operations during the process: one to extract from the Cloud and another to decrypt the data.

Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor also enables the investigator to select the service subtype (such as images, messages, videos, and so on) within the settings of each service after the credentials have been validated. At this time, the investigator can enter a date range for all services or for individual services to provide a focused extraction the court demands or that time allows.

Cellebrite UFED Cloud Analyzer

The UFED Cloud Analyzer is available from Cellebrite for purchase when used with its platform UFED 4PC. Cellebrite offers different types of licenses—one public, one for non-law enforcement (private investigators), and a third for law enforcement only. Each can extract data from the Cloud, but each has separate pricing and requirements.

The public version allows only publicly accessible data to be extracted from cloud services, while the second tier, available to private investigators, includes the ability to obtain public data from cloud services, in addition to a module in which mobile tokens can be used, as can usernames and passwords. The difference, the extraction using usernames and passwords, is consent-based. The law enforcement version is sold only to members of law enforcement, the military, and intelligence agencies and includes the ability to import credential packages from their other solutions that contain usernames/passwords and tokens.

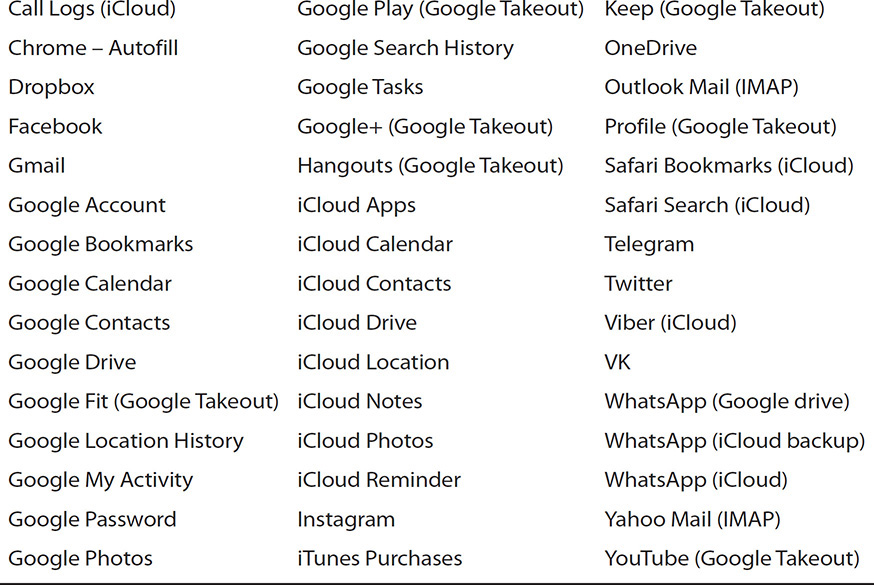

Cellebrite supports, at the time of this writing, more than 50 social media and cloud services. Like Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor, the services range from the most popular messengers to mail clients. Table 4-2 represents the currently supported cloud services by Cellebrite.

TABLE 4-2 Currently Supported Cloud Services in UFED Cloud Analyzer

Magnet AXIOM Cloud

The cloud extraction product Magnet AXIOM Cloud is built into the AXIOM tool. Like the other solutions, Magnet AXIOM Cloud supports the extraction of cloud data from various sources using username/password combinations and/or tokens acquired from data acquisitions of mobile devices and computers. Also, if a mobile device or computer does not contain the necessary information, the investigator can enter the needed credentials manually to conduct an extraction of the cloud service.

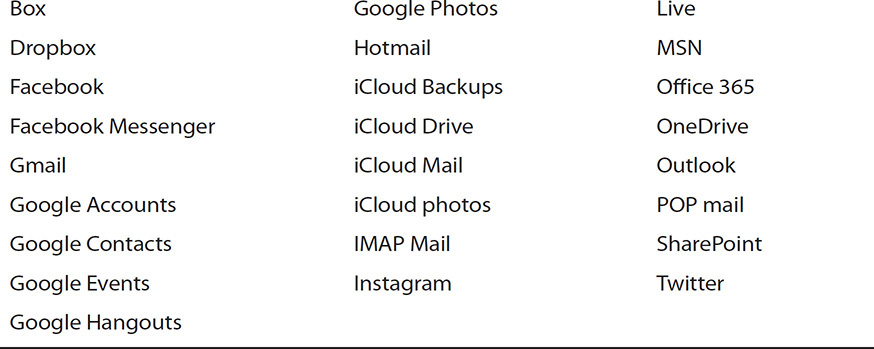

AXIOM Cloud supports approximately 25 cloud artifacts in nine parent services to include Apple Box, Dropbox, IMAP/POP, Facebook, Google, Instagram, Microsoft, and Twitter. Each service is broken down into different subservices.

Magnet AXIOM Cloud also supports the extraction if multifactored authentication is being used. In addition, username/passwords and/or tokens can be used to perform the extraction of the supported cloud services, but tokens are not supported for all cloud services offered. One difference from the other tools is the fact that if two-factor verification is enabled for Apple devices, Magnet is unable to obtain the backup.

The tool also enables the investigator to enter a date range for the cloud source. As mentioned, setting a date range can be an important step, and Magnet AXIOM Cloud offers several range types: before a date, after a date, and custom date ranges are available. An important difference from Oxygen Forensics Cloud Extractor is that with some sources, such as iCloud backups and Google, the date range is ignored by Magnet and all the data is acquired. This can be a problem with extraction of data that contains unopened e-mails or other data not covered in a search warrant.

Magnet also supports the ability to select the types of data that will be extracted from the cloud service (such as images, videos, docs, and so on). This is an important feature to allow for customization by the investigator as well as to satisfy the scope of a search warrant. Table 4-3 lists the various cloud services that, as of this writing, are supported in Magnet AXIOM Cloud.

TABLE 4-3 Currently Supported Cloud Services in Magnet AXIOM Cloud

Chapter Summary

Today’s investigations have transitioned to a new area: the Cloud. The many reasons for this transition include locked devices, encryption, missing devices, or, most importantly, additional data not found on the device. Another, often overlooked, reason for investigating cloud data is simply because the cloud server is the only place an investigator might find data.

The access to the Cloud using commercial tools must follow a process much like any other type of investigation. First, the investigator must have legal authority to conduct the cloud investigation. Second, the scope of the legal authority should dictate both the type of data and the date range of the data that will be collected. Third, with the various forms of authentication into cloud services, it is important that an investigator understand the role of multifactored authentication as it relates to cloud services. Furthermore, in instances such as WhatsApp, the data that is extracted from the cloud service can be completely encrypted and secondary steps must be undertaken to decrypt the collected data. Finally, the way to bypass the multifactor security of the Cloud varies per service. Google data access can be gained via the Google Authenticator, backup codes, and specialized app passwords, while Apple can use verification codes on trusted devices. An investigator should understand the various methods to bypass verification and should ensure that the tool used will comply with requirements.

Although plenty of data is accessible in the various cloud services, much of it often goes unexamined. Apple’s iCloud announced at version 11.4 that messages will be available for access, which is fantastic for investigators. Also, Google services such as My Activity often provide unbelievable caches of data, and having access to this data as an examiner can often complete an investigation. With information in Google My Activity, such as locations, searches, voice, audio, and more, which are unavailable from any other source (such as a mobile device or computer), examiners are sure to find the “smoking gun” evidence.

Many of today’s users are into health wearables, from the Fitbit to the Apple Watch, which includes information such as heart rate, location, food intake, messaging, and other valuable data that is often available only on the cloud service and not on the mobile device. By gathering the many artifacts from the Cloud and the mobile device, the investigator can create a collective view of the user’s digital footprint.

Commercial tools continue to advance in features to combat the massive amounts of data being stored on app cloud services. Tools such as Oxygen Forensics Detective, UFED Cloud Analyzer, and Magnet AXIOM Cloud all have their pros and cons. It is up to the investigator to look at the features and support before deciding on the type of cloud extractor to use. One of the most important aspects of any cloud extractor is how multifactored authentication is handled and how data from mobile devices and their cloud services can be examined within a single interface. Without these two features, an investigator can be dead in the water, with many of the cloud services enabling multifactored authentication.

As any investigator should know, a tremendous amount of data can be stored on a mobile device, but even more is in the Cloud. Chapter 16 will cover the locations and artifacts for many of the cloud services covered here.