7

Raising Capital

Introduction

As Gene Wang, a successful business owner, noted, for the entrepreneur who is in the capital-raising stage, there are four important things to do:

1. Never run out of money.

2. Really understand your business or product.

3. Have a good product.

4. Never run out of money.1

These are great words of advice, but for many entrepreneurs, accomplishing points 1 and 4 is easier said than done.

Several of the most common complaints about entrepreneurship concern money. Entrepreneurs repeatedly lament the fact that raising capital is their greatest challenge because there seemingly is never enough and the fund-raising process takes too long. These are not groundless complaints. Thomas Balderston, a venture capitalist, said, “Too few entrepreneurs recognize that raising capital is a continuing process.”2 Also, it is extremely tough to raise capital, be it debt or equity, for start-ups, expansions, or acquisitions. The process typically takes several years and multiple rounds called Series. Each series is identified in order of the alphabet such as Series A, Series B, Series C, and Series D.

The founding and funding of Google is a classic example of this process. Initially, college friends Sergey Brin and Larry Page maxed out their credit cards to buy the terabytes of storage that they needed in order to start Google. Next, they raised $100,000 from Andy Bechtolsheim, one of the founders of Sun Microsystems, and another $900,000 from their network of family, friends, and acquaintances. Subsequently, Google raised $24 million from two venture capital firms and $1.67 billion from its initial public offering (IPO). The company was 3½ years old when it raised venture capital, and 8½ when it had its IPO.3 But the company that broke the record for quickest IPO from start-up was Netscape, the browser that was founded in the same year that it went public. While that was an aberration in the mid-1990s the norm today is something closer to the Google story. In 2018, six software companies went public. They were Docusign, Smartsheet, Zuora, Zscaler, Dropbox, and SurveyMonkey. On average, these companies raised four rounds of capital (Series D) and operated for 13 years before going public.4

Why is it so difficult to raise capital? The most obvious reason is that capital providers are taking major risks when they finance entrepreneurial ventures. Roughly 50% of businesses fail within the first four years, and more than 7 out of 10 fail within 10 years.5 Over a long time window, the success rate is low. Given this fact, capital providers are justified in performing lengthy due diligence to determine the creditworthiness of entrepreneurs. It may seem sacrilegious for me to say this, but it must be said: those who become entrepreneurs are not entitled to financing simply because they joined the club.

One of my objectives for this book is to supply you with information, insights, and advice that will, I hope, increase your chances of procuring capital. Here are some words on the advice front: since it is so tough to raise capital, the entrepreneur must be steadfast and undeviating in this pursuit. Successful high-growth entrepreneurs are not quitters. They are thick-skinned; hearing the word no does not completely deter or terminate their efforts. A great example of an entrepreneur with such perseverance is Howard Schultz, the CEO of Starbucks. When he was in search of financing for the acquisition of Starbucks, he approached 242 people and was rejected 217 times. He finally procured the financing and acquired the company.6

Value-Added Investors

Howard Schultz and all other successful high-growth entrepreneurs know not only that it is important to raise the proper amount of capital at the best terms, but that it is even more important to raise it from the right investors. There is an old saying in entrepreneurial finance: whom you raise money from is more important than the amount or the cost. The ideal is to raise capital from “value-added” investors. These are people who provide you with insights in addition to their financial investment. For example, value-added investors may give the company legitimacy and credibility because of their upstanding reputation.

Value-added investors also include those who can help entrepreneurs acquire new customers, employees, or additional capital. A great example of an entrepreneur who understands the importance of value-added investors is the founder of eBay, Pierre Omidyar, who accepted capital from the famous venture capital firm Benchmark. Ironically, eBay did not really need the money. It has always been profitable. It accepted $6.7 million from Benchmark for two reasons. The first was that it felt that Benchmark’s great reputation would give eBay credibility. The second was that it wanted Benchmark, which had extensive experience in the public markets, to help eBay complete an IPO. When eBay went public, Benchmark’s investment was worth $5 billion, making it the best investment by a Silicon Valley private equity fund.7

Another great example of an entrepreneur who understood the importance of a value-added investor is Jeff Bezos of Amazon.com. When pursuing venture capital financing, Bezos rejected money from two funds that offered a higher valuation and better terms than Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB), which he accepted. When asked why he took KPCB’s lower bid, he responded, “If we’d thought all this was purely about money, we’d have gone with another firm. But KPCB is the gravitational center of a huge piece of the Internet world. Being with them is like being on prime real estate.”8

In addition to investing $8 million, KPCB also helped persuade Scott Cook, the chairman of Intuit at the time, to join Amazon.com’s board. KPCB also immediately helped Bezos recruit two vice presidents and helped him take Amazon.com public, over two decades ago.

While these two examples highlight only venture capitalists, it must be made perfectly clear that there are several other sources of value-added capital.

Sources of Capital

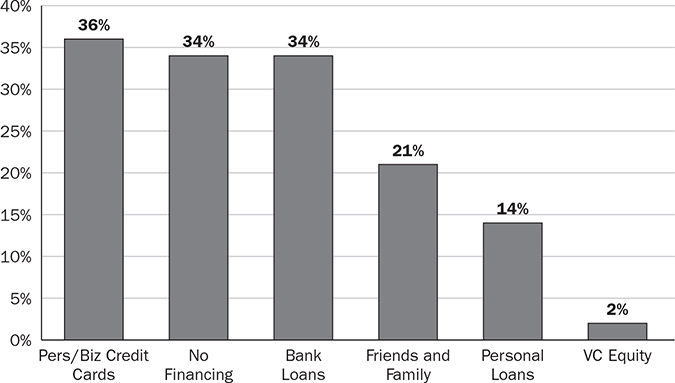

The source of capital that gets the most media attention is venture capital funds. But in reality, as Figure 7-1 shows, these funds have been a small contributor to the total annual capital provided to entrepreneurs. According to the 2018 Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project, current financing comes from multiple sources mixed together. Venture capital is the least common at 1%! The most common are the combinations of personal and business credit cards at 39%, but the most common single source of funding comes from bank loans at 34%. Notably, over one-third (35%) of small business owners have no financing at all.9 The former director of this annual research project on US private capital, Dr. John Paglia, made it clear in a verbal summary of his findings: “Basically, American Express cards are the most common source of start-up capital in America!”

FIGURE 7-1 Sources of Small-Businesses’ Financing

Adapted from Pepperdine Private Capital Markets Project, Private Capital Markets Report 2019, pg. 103, https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=gsbm_pcm_pcmr.

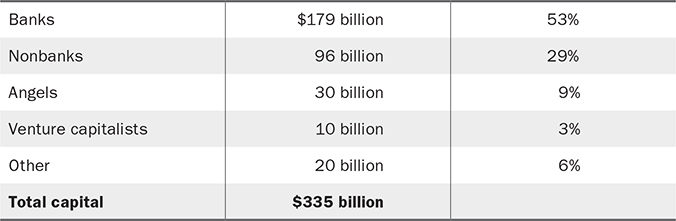

According to a Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) United States report on financing entrepreneurship, eliminating venture capital would not make a perceptible difference in entrepreneurial activity overall because fewer than 1 in 10,000 new ventures has venture capital in hand at the outset, and fewer than 1 in 1,000 businesses ever have venture capital at any time during their existence. According to the GEM, across the world, 73% of start-up funds come from the entrepreneurs themselves, with the remaining 27% coming from external sources.10 Money from friends, family, and the owners themselves is a bit more difficult to track. Table 7-1 shows data from a study conducted a few years back that examines the more formal sources of financing for entrepreneurs, and it shows that banks, with $179 billion in annual loans to small businesses at that time, were the most active backers of entrepreneurs. The number 2 providers, with $96 billion, were nonbank financial institutions such as GE Capital and Prudential Insurance. Venture capital was less than one-tenth of the amount of capital provided by banks. These relative levels have not changed drastically today.

TABLE 7-1 Sources of Outside Capital for Entrepreneurs

The fact that banks are more important to entrepreneurship than venture capitalists can be further highlighted by the fact that even the most active venture capitalist will finance only 15 to 25 deals a year after receiving as many as 7,000 business plans. The result is that in 2018, after receiving over 8 million business plans, the entire venture capital industry invested in a total of 9,000 companies,11 of which fewer than two-fifths (1,174) were new ventures; most were reinvestments in known entrepreneurs and later-stage ventures.12 This is akin to a pebble in the ocean compared with banks.

For a business loan, business owners approached on average 2.4 banks and achieved a 69% success rate. Owners approached 4.8 VC funds and only 19% were successful. Business credit cards provided the best success as owners approached 1.6 sources with an 83% success rate.13

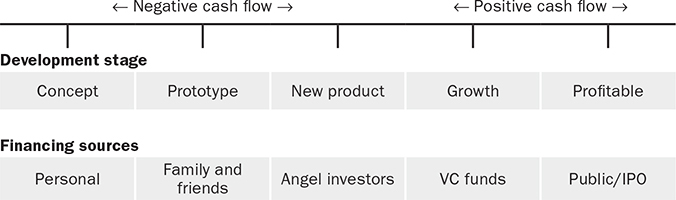

The financing spectrum in Figure 7-2 best depicts the financing sources typically used by start-up entrepreneurs. In Chapter 8, “Debt Financing,” and Chapter 9, “Equity Financing,” we will discuss each of these sources in greater detail. And at the end of Chapter 9, we will show how one entrepreneur became successful by using almost all the sources. Using all the sources is quite common among successful high-growth entrepreneurs.

FIGURE 7-2 Financing Spectrum