9

Equity Financing

Introduction

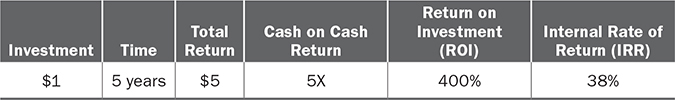

Equity capital is money provided in exchange for ownership in the company. The equity investor receives a percentage of ownership that ideally appreciates in value as the company grows. The investor may also receive a portion of the company’s annual profits, called dividends, based on his ownership percentage. For example, a 10% dividend yield or payout on a company’s stock worth $200 per share means an annual dividend of $20. The typical equity investor wants the following minimum returns.

Thus, the investor expects a minimum return of 5 times his money in 5 years, which results in a cash on cash return of 5X, a Return on Investment (ROI) of 400%, and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) of 38%. Cash on cash return is a multiple times the investment. The formula is Total Return divided by Investment. The Return on Investment is the profit generated from the original investment. Every entrepreneur should know the ROI for every product he sells or service he provides. The formula is

The Internal Rate of Return is the average compounded annual return on the original investment. This is tough to manually calculate. I recommend the use of the “IRR Calculator” that can be found online. Equity investors always want IRRs that are greater than their cost of capital. Thus, it is not an attractive investment if a deal generates an IRR of 38%, but the investor’s annual cost of capital, in the form of interest expense, was 40%.

Pros and Cons of Equity Financing

Before deciding to pursue equity financing, the entrepreneur must know the positive and negative aspects of this capital.

Pros

• No personal guarantees are required.

• No collateral is required.

• No regular cash payments are required.

• There can be value-added investors.

• Equity investors cannot force a business into bankruptcy.

• Companies with equity financing grow faster.

Cons

• Dividends are not tax-deductible.

• The entrepreneur has new partners.

• It is typically very expensive.

• The entrepreneur can be replaced.

Sources of Equity Capital

Many of the sources of debt capital can also provide equity capital. Therefore, for those common sources, what was said about them elsewhere in the book also applies here. When appropriate, a few additional issues might be added in this discussion of equity.

Personal Savings

When an entrepreneur personally invests money in the company, it should be in the form of debt, not equity. This will allow the entrepreneur to recover her investment with only the interest received being taxed. The principal will not be taxed, as it is viewed by the IRS as a return of the original investment. This is in contrast to the tax treatment of capital invested as equity. Like interest, the dividend received would be taxed; however, so would the entire amount of the original investment, even if no capital gain is realized.

The entrepreneur’s equity stake should come from her hard work in starting and growing the company, not her monetary contribution. This is called sweat equity.

Friends and Family

Equity investments are not usually accompanied by personal guarantees from the entrepreneur. However, such assurances may be required of the entrepreneur when he receives capital from friends and family members in order to maintain the relationship if the business fails.

But this may be a small price to pay in order to realize an entrepreneurial dream. Start-up capital is difficult to obtain except through friends and family. Dan Lauer experienced this firsthand when he was starting his company, Haystack Toys. He raised $250,000 from family and friends after quitting his job as a banker. He went to family and friends after 700 submission letters to investors went unanswered.1

Angel Investors

Wealthy individuals usually like to make their investments in the form of equity because they want to share in the potential growth of the company’s valuation. There is at present and has always been a dearth of capital for the earliest stages of entrepreneurship—the seed or start-up stage. Angel investors have done an excellent job of providing capital for this stage. Their investments are typically between $150,000 and $300,000. In exchange, they expect high returns (ranging from 25 to 38% IRR),2 similar to that expected by venture capitalists.3 Jeff Bezos raised $981,000 from 20 to 23 angel investors before he received money from venture capitalists to fund Amazon. Since angels are investing at the earliest stage, they usually also get a large ownership position in the company because the valuation is so low.

Many angel investors are former successful entrepreneurs. One of the prominent former entrepreneurs who has gone on to become an angel investor is Mitch Kapor, who in 1982 founded Lotus Development, the producer of Lotus 1-2-3 software, which he sold to IBM in 1995 for $3.5 billion. Kapor became an angel investor, placing 18 investments annually in a range of $100,000 to $250,000; among his recent investments are Uber, Mozilla, and Twilio.4 He was also an early investor in UUNet, the first Internet access provider.

Jeff Bezos not only received angel investments during the early stages of Amazon, but he also “paid it forward” as an angel investor. For example, he invested $250,000 in the earliest stages of Google. Today, that investment is estimated to be worth over $3.1 billion. But angel investing has never been limited to entrepreneurs. In fact, Apple Computer got its first outside financing from an angel who had never owned a company. He was A. C. “Mike” Markkula, who gained his initial wealth from being a shareholder and corporate executive at Intel. In 1977, he invested $91,000 in Apple Computer and personally guaranteed another $250,000 in credit lines. When Apple went public in 1980, his stock in the company was worth more than $150 million.5

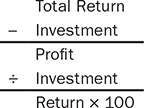

This is one of several reasons why the number of angel investors has increased so dramatically: returns. The publicity surrounding successful entrepreneurial ventures often includes stories about the returns that investors received. These stories, coupled with research, have led many wealthy individuals to the private equity industry. And while the anecdotal stories themselves are quite impressive, the more seductive story is empirical research that compares the returns of private equity firms with returns on several other investment options. Table 9-1 shows that overall investment windows, average annual returns for private equity firms were greater than those for all other investment options.

TABLE 9-1 Average Annual Returns, 1987–2012

The second reason for the increase in angel capital was an increase in the number of wealthy people in the country who had money to invest. For example, in 2018 there were a record 11.8 million US households with a net worth of a million dollars. This was the tenth consecutive year that the number of millionaires has increased.6 Many of these millionaires gained their wealth through successful technology entrepreneurial ventures.

The final reason for the explosion in angel capital was the change in federal personal tax laws. In May 1997, the statutory capital gains tax rate on long-term gains was decreased from a maximum of 28% to 20%; this rate was further reduced to 15% starting in May of 2003. The Small Business Jobs Act of 2010 eliminated long-term capital gains taxes for venture capital and angel investors who held stock investments for at least 5 years. The most recent government policy change that positively impacted angel capital was the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Thus, people were able to keep more of their wealth, and some used it to invest in entrepreneurs.

Interestingly, it was rumored that one of the groups that lobbied strongly against reductions in the long-term capital gains tax rate was institutional investors. These are private equity firms, not individual investors. They challenged the change because they correctly predicted that it would hurt their business. They believed that as more money became available to entrepreneurs, a company’s valuation would inevitably increase, and there would be more competition. Rich Karlgaard, the publisher of Forbes magazine, made this observation:

In my cherubic youth, I used to wonder why so many venture capitalists opposed a reduced capital gains tax. Then I woke up to the facts. Crazy as it sounds, even though venture capitalists stand to benefit individually by reduced capital gains taxes, the reduced rates would also lower entry barriers for new competition in the form of corporations and angels. That might lead to—too much venture capital.7

Beginning in January 2013, this group got its wish when the maximum long-term capital gains tax rate was increased to 25%. In 2019, the highest tax rate for long-term investments is 20%.

Even though the amount of capital invested by venture capitalists and angel investors is traditionally on a similar scale, according to the Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire, the angel investor market in 2018 experienced an increase in market participation in more companies, albeit at smaller amounts, according to the Center for Venture Research at the University of New Hampshire. Total angel investments in 2018 were $23.1 billion. A total of 66,110 entrepreneurial ventures received angel funding in 2018, an increase of 7.4% over 2017 investments. The number of active investors in 2018 rose to 334,565 as compared to 288,380 in 2017, a robust increase of 16%. The change in total dollars and the number of investments resulted in a deal size for 2018 that was smaller than in 2017, reflecting lower valuations. The increase in number of investments likely offsets a decline in activity by institutional investors in seed and start-up deals, and the smaller deal size may have partially contributed to the increase in angel investors.8 Healthcare Services/Medical Devices and Equipment regained its dominant sector position with 23% of total angel investments in 2018, followed by Software (20%), Retail (13%), Biotech (9%), Financial Services/Business Products and Services (8%), and Industrial/Energy (6%). Industrial/Energy investing is predominately in clean tech.9

Despite private equity firms’ complaints, the increase in available capital was clearly a huge positive for entrepreneurs. A few other positive aspects of angel equity capital for entrepreneurs are as follows:

• Seed capital is being provided. Most institutional investors do not finance this early stage of entrepreneurship.

• Many of the angels have great business experience and therefore are value-added investors.

• Angel investors can be more patient than institutional investors, who have to answer to their limited partner investors.

But there are also a few negative aspects to raising money from angels:

• Potential interference. Most angels want not only a seat on the board of directors but also a very active advisory role, which can be troublesome to the entrepreneur.

• Limited capital. The investor may be able to invest only in the initial round of financing because of limited capital resources.

• The capital can be expensive. Angels typically expect annual returns in excess of 25%.

Regarding this final point, here is what an angel investor said about his expectations:

I expect to make a good deal of money—more than I would make by putting my capital into a bank, bonds, or publicly traded stocks. My goal, after getting my principal back, is to earn 33% of my initial investment every year for as long as the business is in operation. My usual understanding is that for my investment I own 51% of the stock until I am paid back, whereupon my stake drops to 25%. After that, we split every dollar that comes out of the business until I earn my 33% return for the year.10

Despite the drawbacks, most entrepreneurs who raise angel capital successfully do not regret it. As one entrepreneur said, “Without angel money, I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish what I have. Giving up stock was the right thing to do.”11

Gaining access to angel investors is not an easy task. Cal Simmons, an Alexandria, Virginia–based angel investor and coauthor of Every Business Needs an Angel, says, “You need to have networks. If someone I know and respect refers me, then I’m going to always take the time to take a meeting.” Angel groups are another mechanism for getting access to angel investors. There are currently 14,000+ angel groups registered with the Angel Capital Association (www.angelcapitalassociation.org), an angel capital industry trade group supported by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Many of these groups accept applications to present to their angels. Some of them charge entrepreneurs a nominal fee of $100 to $200 to present.12

There are forums in almost every region of the country similar to the Midwest Entrepreneurs Forum in Chicago. At this event, held the second Monday of each month, entrepreneurs make presentations to angel investors. There are also several angel-related websites, including AngelList in Silicon Valley (angel.co), SeedInvest (seedinvest.com), and OnStartups (onstartups.com).

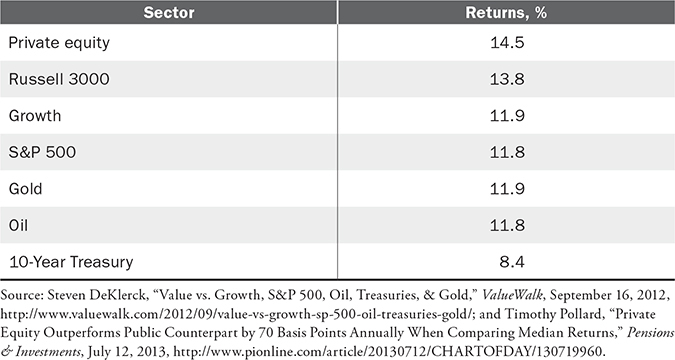

Private Placements

When entrepreneurs seek financing, be it debt or equity, from any of the sources mentioned up until now, that financing is called a private placement offering. That is, capital is not being raised on the open market via an initial public offering, which will be discussed later in this chapter. The capital is being raised from specific individuals or organizations that meet all the standards set by Section 4(2) of the US Securities Act of 1933 and Regulation D, an amendment to this act that clarified the rules for those seeking a private placement exemption. The rule says, “Neither the issuer nor any person acting on its behalf shall offer or sell the securities by any form of general solicitation or general advertising. This includes advertisements, articles or notices in any form of media. Also, the relationship between the party offering the security and the potential investor will have been established prior to the launch of the offering.”13 All of this simply means that an entrepreneur cannot solicit capital by standing on the corner trying to sell stock in his company to any passerby. He cannot put an ad in a newspaper or magazine recruiting unaccredited investors. He must know his investors, either directly or indirectly. Potential investors in the latter category are known through the entrepreneur’s associates, such as his attorney, his accountant, or his investment banker.

Fund-raising efforts must be restricted to “accredited investors only.” These investors are also known as “sophisticated investors.” Such an investor has to meet one of the following three criteria:

• An individual net worth (or joint net worth with a spouse) that is greater than $1 million

• An individual income (without any income of a spouse) in excess of $200,000 in each of the two most recent years and reasonably expects an income in excess of $200,000 in the current year

• Joint income with a spouse in excess of $300,000 in each of the two most recent years and reasonably expects to have joint income in excess of $300,000 in the current year

Prior to accepting investments, the entrepreneur must get confirmation of this sophisticated investor status by requiring all the investors to complete a form called the Investor Questionnaire. This form must be accompanied by a letter from the entrepreneur’s attorney or accountant stating that the investors meet all the accreditation requirements.

Violation of any part of Regulation D could result in a six-month suspension of fund-raising or something as severe as the company is being required to return all the money to the investors immediately. Therefore, the entrepreneur should hire an attorney experienced with private placements before raising capital. Figure 9-1 summarizes the Regulation D rules and restrictions.

FIGURE 9-1 Regulation D Rules Restrictions

As stated earlier, sources of capital for a private placement are angel investors, insurance companies, banks, family, and friends, along with pension funds and private investment pools. There are no hard-and-fast rules regarding the structure or terms of a private placement. Therefore, private placements are ideal for high-risk and small companies. The offering can be for all equity, all debt, or a combination of debt and equity. The entrepreneur can issue the offering or use an investment banker.

The largest and most prominent national investment banks that handle private placements are Bank of America/Merrill Lynch, JPMorgan Chase, and Credit Suisse. These three banking firms raise a total of more than $30 billion for entrepreneurs each year. Regional investment bankers are better suited for raising small amounts of capital.

When hiring an investment banker, the entrepreneur should expect to pay either a fixed fee or a percentage of the money raised (which can be up to 10%), and/or give the fund-raising professional a percentage of the company’s stock (up to 5%). One important piece of advice is that the entrepreneur should be extremely cautious about using the same investment banker to determine the amount of capital needed and to raise the capital. There is a conflict of interest when the investment banker does both for a variable fee. Whenever only one investment banker is used for both assignments, the fee should be fixed. Otherwise, use different companies for each assignment.

Shopping a Private Placement

After the private placement document has been completed, it must be “shopped” to potential investors. The following describes the process of shopping a private placement:

1. Make an ideal investor profile list (those who have met the net asset requirement).

2. Identify whom to put on the actual list:

• Former coworkers with money

• Industry executives and salespeople who know your work history

• Past customers

3. Call the candidates and inform them of the minimum investment amount.

4. Send a private placement memorandum outlining the investment process only to those who are not intimidated by the minimum investment indicated during the call.

5. Contact other companies in which your investors have invested.

Corporate Venture Capital

In the late 1990s, large corporations embraced entrepreneurship with the same interest as individuals. This was surprising because it was assumed that corporations, with their reputations for stodgy bureaucracy and conservatism, were “anti-entrepreneurship.” Their primary relationship with the entrepreneurship world came as investors. This began to change in the late 1990s, as corporations began to realize the opportunities associated with investing in companies that had products or services related to their industry. Such strategic investments became a part of corporations’ research and development programs as they sought access to new products, services, and markets. For example, cable television operator Comcast Corp. established a $125 million fund to invest in companies that would “help it understand how to capitalize on the Internet.” Comcast wanted to bring its cable TV customers online, and saw the potential to put its QVC shopping channel on the Internet.14

The final reason that such prominent corporations as Salesforce, Intel, Cisco, Google, Microsoft, and Reader’s Digest created their funds was to find new customers. As one person described it, “Corporations are using their venture-backed companies to foster demand for their own products and technologies.”15 Two companies implementing that strategy were Andersen Consulting and Electronic Data Systems. Both companies invested in customers that used their systems integration consulting services.

Traditional venture capitalists love it when their portfolio companies receive financing from corporate venture capitalists. The primary reason is that the latter are value-added investors. In fact, three of the most successful venture capital firms—Accel Partners, Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB), and Battery Ventures—have wholeheartedly endorsed the use of corporate funds. This point was made by Ted Schlein, a partner with KPCB, who said, “Having a corporation as a partner early on can give you some competitive advantages. The portfolio companies are after sales and marketing channels.”16

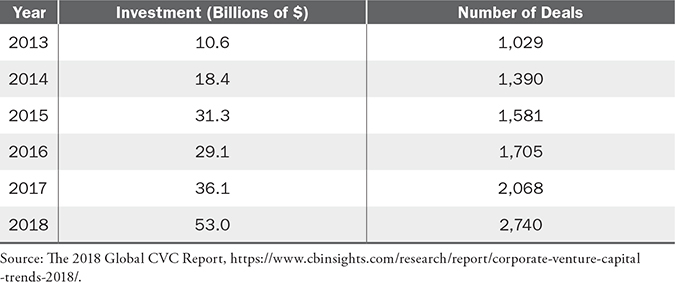

When the stock market crashed in 2000, corporate venture capital dried up. Total investment dollars dropped from $16.8 billion in 2000 to under $2 billion in 2002. This 88% drop was faster than the 75% drop in the overall markets. This faster rate of decline makes sense. Venture capital is not the primary business of corporations, and it can be expected that, in times of economic hardship, these firms will pull back their financing. Moreover, many of these firms need to manage short-term earnings expectations, so investment funding gets cut when quarterly earnings figures are threatened. Table 9-2 shows corporate venture capital investments from 2013 through early 2018.17 In 2017, 75% of the Fortune 100 have corporate venture capital investing practices. And they invest in almost a third of venture deals in the country.18

TABLE 9-2 Corporate Venture Capital Investment, 2013–2018

Private Equity Firms

Many of the sources of equity financing that have been discussed up to this point are individuals. But there is an entire industry filled with “institutional” investors. These are firms that are in the business of providing equity capital to entrepreneurs, with the expectation of high returns.

This industry is commonly known as the venture capital industry. However, venture capital is merely one aspect of private equity. The phrase private equity comes from the fact that money is being exchanged for equity in the company and that this is a private deal between the two parties—investor and entrepreneur. For the most part, all the terms of the deal are dependent on what the two parties agree to. This is in contrast to public equity financing, which occurs when the company raises money through an initial public offering. In that case, all aspects of the deal must be in accordance with Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules. One rule is that the financial statements of a public company must be published and provided to the investors quarterly. Such a rule does not exist in private equity deals. The two parties can make any agreement they want; for example, financial statements can be sent to investors every month, quarterly, twice a year, or even once a year.

Private Equity: The Basics

It is important to note that the owners of private equity firms are also entrepreneurs. These firms are typically small companies that happen to be in the business of providing capital. Like all other entrepreneurs, they put their capital at risk in pursuit of exploiting an opportunity and can go out of business.

Legal Structure

Most private equity firms are organized as limited partnerships or limited liability companies. These structures offer advantages over general partnerships by indemnifying the external investors and the principals. They also have advantages over C corporations because they limit the life of the firm to a specific amount of time (usually 10 years), which is attractive to investors. Furthermore, the structures eliminate the double taxation of distributed profits.

The professional investors who manage the firm are the general partners (GPs). The GPs invest from 1 to 5% of their personal capital in the fund and make all the decisions. External investors in a typical private equity partnership are called limited partners (LPs). During the fund-raising process, LPs pledge or commit a specified amount of capital for the new venture fund. For most funds formed today, the minimum capital commitment from any single LP is $1 million; however, the actual minimum contribution is completely at the discretion of the firm. The commitment of capital is formalized through the signing of the partnership agreement between the LPs and the venture firm. The partnership agreement details the terms of the fund and legally binds the LPs to provide the capital that they have pledged.

Getting Their Attention

GPs rely on their proprietary network of entrepreneurs, friendly attorneys, limited partners, and industry contacts to introduce them to new companies. They are much more likely to spend time looking at a new opportunity that was referred to them by a source they find trustworthy than one referred to them by other sources. A business plan that is referred through their network is also less likely to be “shopped around” to all the other venture capitalists focused on a particular industry segment. GPs want to avoid getting involved in an auction for the good deals because bidding drives up the valuation. In the course of a year, a typical private equity firm receives thousands of business plans. Less than 10% of these deals move to the due diligence phase of the investment.

Choose Investors Wisely

It is very important that you choose potential investors carefully—you will be establishing an important long-term relationship with them. Do your research on each potential investor before sending your business plan to ensure a better rate of acceptance. Find out what types of deals the investor pursues. What is the firm’s investment strategy, and what are its selection criteria? What is its success rate? How have the investors reacted during critical situations, such as a financial crisis? Do the investors just bail out, or are they in for the long haul? One good source of information in this regard is other companies that have received backing from that particular investor. Will the “value-added” investors provide useful advice and contacts, or will they provide only financial resources?

It is extremely important that you know your audience so that you can limit your search to those who have an affinity for doing business with you. If your company is a start-up, then you should send the plan to those who provide “seed” or start-up capital rather than later-stage financing. For example, it would be a waste of time to send a business plan for the acquisition of a grocery store to a technology-focused lender, such as Silicon Valley Bank.

It is always advisable to get what venture capital professional Bill Sutter calls “an endorsed recommendation,” preferably from someone who has had previous business dealings with the investor, before submitting your business plan. John Doerr at KPCB stated, “I can’t recall ever having invested in a business on the basis of an unsolicited business plan.”19 This endorsement will guarantee that your business plan will be considered more carefully and seriously. If a recommendation is not possible, then an introduction by someone who knows the investor will be helpful. In most instances, unsolicited business plans submitted to venture capital firms without a referral have a lower chance of getting funding than those submitted with one. If you are submitting an unsolicited business plan, it is important that you write it so that it is consistent with the investor’s investment strategy.

A good example of someone who did this correctly is Mitch Kapor, the founder of Lotus Development Corporation, who sent his business plan to only one venture capital firm. Recognizing that his business plan was somewhat different—it included a statement saying that he was not motivated by profit—he knew himself and his company well enough to know that not all venture capitalists would take him seriously. He carefully selected one firm—Sevin and Rosen. Why? Because this firm was used to doing business with his “type”—namely, computer programmers. They knew him personally, and they knew the industry. It was a good decision. He got the financing he sought, even though he had a poorly organized, nontraditional plan.

Investor Screening Process

Most firms use a screening process to prioritize the deals that they are considering. Generally, associates within a firm are given the responsibility of screening new business plans based on a set of investment criteria, developed over time by the firm. These criteria are communicated in the partnership agreement submitted by the fund manager to their LPs, and to which fund managers must strictly adhere. LPs rely on fund managers to stay within the proposed “investment thesis” or investment characteristics, so that the LPs can measure and manage financial risk down to the portfolio level at each of their fund investments. Straying from the thesis leads to significant criticism by the LPs.

Several of the parameters used to screen investments are:

• Management: financial acumen, integrity, and experience

• Market size

• Growth expectations

• Phase in the industry life cycle

• Differentiating factors

• Terms of the deal

An entrepreneur can expedite the process by creating a concise, accurate, and compelling 2- to 3-page executive summary or 15-page maximum “Pitch Deck” investment brief that addresses an investor’s key concerns. The entrepreneur’s ability to communicate her ideas effectively and succinctly through a written, oral, or, in some instances, video format is critical to receiving funding for the project.

Once a deal passes the first screen by meeting a majority of the initial criteria, a private equity firm begins an exhaustive investigation of the industry, the managers, and the financial projections for the potential investment. Due diligence may include hiring consultants to investigate the feasibility of a new product; doing extensive reference checking on management, including background checks; and undertaking detailed financial modeling to check the legitimacy of projections. The entire due diligence process from initial pitch to money in the bank can take six to nine months.20

Management

Most GPs list management as their most important criterion for the success of an investment. This validates the axiom that the investment is in the jockey not the horse. For example, venture capitalist Andrew Braccia from Accel told the founder of Slack, Stewart Butterfield, “The reason we invested was because we were investing in the team. If you want to be an entrepreneur and build something then I’m with you.” When Slack went public in 2019, Accel’s stock was worth $2.6 billion.21

The management team is evaluated based on attributes that define its leadership ability, experience, and reputation, including:

• Recognized achievement

• Teamwork

• Work ethic

• Operating experience

• Commitment

• Integrity

• Reputation

• Entrepreneurial experience

GPs use a variety of methods to confirm the information provided by an entrepreneur, including extensive interviews, private detectives, background checks, and reference checks. During the interview process, the entrepreneur must provide compelling evidence of the merits of the business model and of the management team’s ability to execute it. Therefore, the management team must clearly and concisely articulate the product or service concept and be prepared to answer a series of in-depth questions about it. In addition, the interview process provides an indication to both sides of the fit between the venture capitalist and the entrepreneur. A good fit is critical to the potential success of the investment because of the difficult decisions that will inevitably need to be made during the life of the relationship.

Some firms believe in the strength of management so much that they invest in a management team or a manager before a company exists. Often, these entrepreneurs have successfully brought a company to a lucrative exit and are looking for the next opportunity. Some venture firms give these seasoned veterans the title “entrepreneur in residence” and fund the search for their next opportunity.

Ideal Candidate

Again, private equity from institutional investors is ideal for entrepreneurial firms with excellent management teams. These companies should be predicted to experience or be experiencing rapid annual growth of at least 20%. The industry should be large enough to sustain two large, successful competitors. And the product should have:

• Limited technical and operational risks

• Proprietary and differentiating features

• Above-average gross margins

• Short sales cycles

• Repeat sales opportunities

Finally, the company must have the potential to increase in value sufficiently in five to seven years for the investor to realize her minimum targeted return. Coupled with this growth potential must be at least two explicit discernible exit opportunities (sell the company or take it public) for the investor. The entrepreneur and the investor must agree in advance on the timing of this potential exit and the strategy. For example, an ideal entrepreneurial financing candidate is one who knows that he wants to raise $10 million in equity capital for 10% of his company and expects to sell the company to a Fortune 500 corporation in five years for 7 times the company’s present value. This tells the investor that she can exit the deal in Year 5 and receive $70 million for her investment.

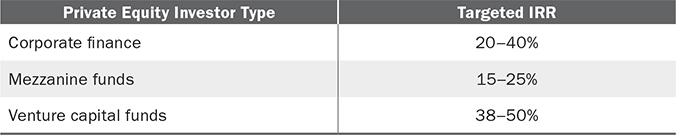

When an entrepreneur goes after private equity funding, he should know what kind of returns are expected. The targeted minimum internal rates of return for the institutional private equity industry are noted in Table 9-3 (see next page).

TABLE 9-3 Targeted IRR for Private Equity Investors

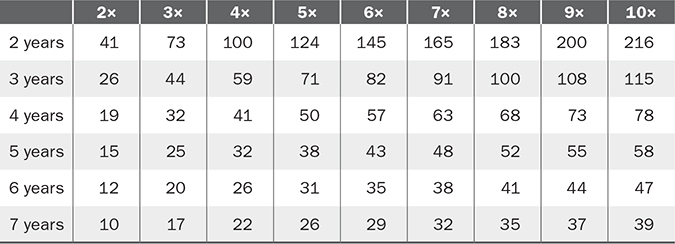

Again, private equity investors make their “real” money when a portfolio company has a liquidation event: the company goes public, merges, is recapitalized, or gets acquired. Depending on the equity firm and its investment life cycle, the fund’s investors typically plan to exit anywhere between 3 and 10 years after the initial investment. Among other things, investors consider the time value of money—the concept that a million dollars today is worth more than a million dollars five years from now—when determining what kind of returns or IRR they expect over time. Table 9-4 provides an approximate cheat sheet for the entrepreneur. As the table shows, an investor who walks away with 5 times her initial investment in five years has earned a 38% IRR.

TABLE 9-4 Time Value of Money—IRR on a Multiple of Original Investment over a Period of Time

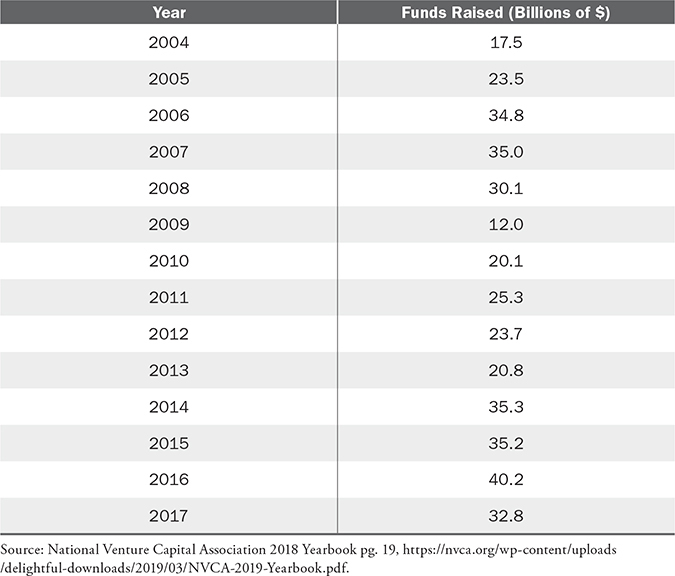

During the 1990s, there was an explosion in the number of private equity funds formed. According to the National Venture Capital Association, the total number of private equity funds (venture capital, mezzanine, and buyout) in the United States increased substantially, going from 150 in 1990 to 805 in 2000. Why? You know the answer: returns! In 2003, after the dot-com crash, this number had fallen to only 282. As private equity fund-raising returned in the mid-2000s, the number of funds climbed back to 499 in 2007, then fell again to 400 in 2012. As of January 2018, a record 2,296 private equity funds were active in the market, seeking to raise an aggregate $744 billion.22 Table 9-5 shows venture capital fund-raising from 2004 to 2017.23

TABLE 9-5 US VC Fund-Raising by Year

International Private Equity

Over the last decade, private equity has exploded around the globe. While North America still represents 41% of all private equity dollars, other regions are catching up, and fund-raising is increasing around the world. While much of the capital comes from US investors, foreign investors, including governments such as those of China and Kuwait, have allocated assets to private equity investing. Within the venture capital world, the United States is still dominant. With a staggering 71% of the venture capital raised by G7 nations, the United States remains the center of entrepreneurial activity.

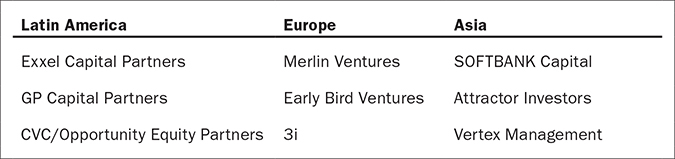

Both the number of funds and the amount of capital that has been raised in Europe, Latin America, and Asia have dramatically increased each year. Most of the money, estimated to be 60 to 70%, has come from investors in the United States, including pension funds, insurance companies, endowments, and wealthy individuals. Several of the international funds are highlighted in Figure 9-2. The amount of capital raised in 2018 was $9.4 billion in Europe,24 $76 billion in Asia,25 $8.7 billion in Latin America and the Caribbean, and $2.8 billion in Africa.26

FIGURE 9-2 Various International Private Equity Firms

Advice for Raising Private Equity

Derrick Collins, a former general partner at Polestar Capital and currently dean of the School of Business at Chicago State University, gives the following advice to entrepreneurs who are interested in obtaining equity capital:

• Do your homework. Seek investors who have a proclivity for your type of deal. Approach only those who are buying what you are selling. Pursue capital from firms that explicitly state in their description an interest in your industry, the size of the investment you want, and the entrepreneurial stage of your company.

• Get an introduction to the investors prior to submitting the business plan. Find someone who knows one of the general partners, limited partners, or associates of the firm. Ask that person to call on your behalf to give you an introduction and endorsement. This action will maximize the attention given to your plan and shorten the response time.

If these steps result in a meeting with a private equity investor, Tom Cox, a general partner of Cascade Partners, puts it this way:

Be alert to the behavior of a venture capitalist who “SITS” on your presentation, which means they “Show Interest Then Stall.” This will be obvious from the pattern of calls you make to them, and whether those calls are returned in a timely manner, as well as to the detailed content of the conversations. A slow “maybe” feels much worse, but is more common than a fast “no.”

Increasing Specialization of Private Equity Firms

There has been an increasing trend toward private equity firms specializing in a particular industry or stage of development. Firms can be categorized as either generalists or specialists. Generalists are more opportunistic and look at a variety of opportunities, from high-tech to high-growth retail. Specialized firms tend to focus on an industry segment or two, for instance, software and communications. Notice that these are still very broad industries.

Specialization has increased for several reasons. First, in an increasingly competitive industry, venture capitalists are competing for deal flow. If a firm is the recognized expert in a certain industry area, then it is more likely that this firm will be exposed to deals in this area. Additionally, the firm will be better able to assess and value the deal because of its expertise in the industry. Finally, some specialized firms are able to negotiate lower valuations and better terms because the entrepreneur values the industry knowledge and contacts that a specialized firm can provide. Entrepreneurs should keep this in mind when raising funds. As important as it is for them to target the correct investment stage of a prospective venture capital firm, it is equally important that they consider the firm’s industry specialization.

Identifying Private Equity Firms

One of the best resources for finding the appropriate private equity firm is Pratt’s Guide to Private Equity and Venture Capital Sources, which lists companies by state, preferred size of investment, and industry interests. Several additional resources are available online:

1. The National Venture Capital Association at https://nvca.org/

2. University of New Hampshire, Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics Center for Venture Research Capital Locator at https://paulcollege.unh.edu/center-venture-research

3. Crunchbase at https://www.crunchbase.com/search/organizations/field/organizations/categories/finance

The final suggestion is to pursue the opportunity to make a presentation at a venture capital forum such as the Springboard Conference for female entrepreneurs or the Mid-Atlantic Venture Fair, which is open to entrepreneurs in all industries and at all stages of the business cycle. These are usually two-day events in which entrepreneurs get a chance to present to and meet local and national private equity providers. Typically, the entrepreneur must submit an application with a fee of approximately $200. If the investor is selected to make an 8- to 15-minute presentation, an additional fee of $500 or so may be required. The National Venture Capital Association should be contacted to find out about forums and their locations, times, and dates.

Small-Business Investment Companies

The federal government, through the Small Business Administration (SBA), also provides equity capital to entrepreneurs. Small-business investment companies (SBICs) are privately owned, for-profit equity firms that are licensed and regulated by the SBA. SBICs invest in businesses employing fewer than 500 people and showing a net worth not greater than $18 million and an after-tax income not exceeding $6 million over the two most recent years. As of December 31, 2018, there are more than 300 licensed SBICs in the country. The SBIC program currently has invested or committed about $30.3 billion in small businesses, with the SBA’s share of capital at risk about $14.5 billion. In fiscal year 2018, the SBA committed to guarantee $2.52 billion in SBIC small business investments. SBICs invested another $2.98 billion from private capital for a total of $5.50 billion in financing for 1,151 small businesses. Investments ranged from $ 250,000 to $5 million.27

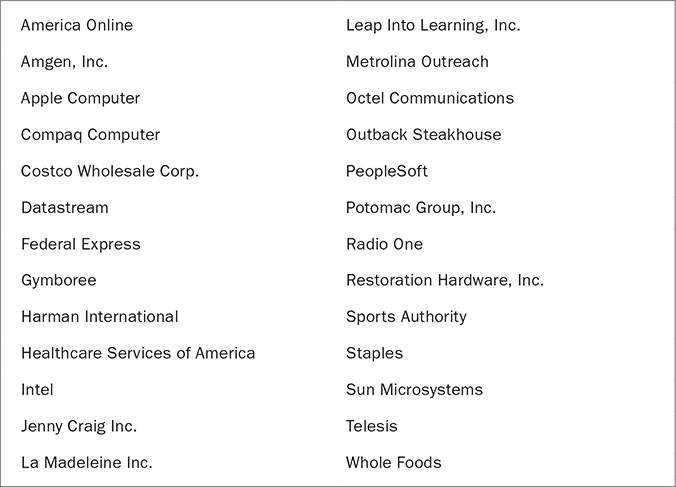

SBICs were created in 1958 for the purpose of expanding the availability of risk capital to entrepreneurs. Many of the first private equity firms were SBICs. And many of the country’s successful companies received financing from an SBIC. These include Intel, Apple, Whole Foods Market, Costco, and Outback Steakhouse.

In most ways, SBICs are similar to traditional private equity firms. The primary differences between the two are their origination and their financing. Anyone can start a traditional private equity firm as long as he can raise the capital. But someone who is interested in starting an SBIC firm must first get a license from the SBA. Interest in creating a Standard Debenture SBIC comes from the attractive financing arrangement: for every dollar the general partners raise for the fund, the SBA will invest $2 at a very low interest rate, with no payments due for either 5 or 10 years. Therefore, if the general partners obtain $25 million in commitments from private sources, the SBA will invest $50 million, making it a $75 million fund. Standard Debenture SBICs tend to focus on growth-stage companies rather than pure start-ups. The Early Stage Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) Initiative was created under the Standard Debenture model to commit up to $1 billion in SBA-guaranteed leverage over a five-year period (2012–2016) to selected early-stage venture funds. The difference is that the match is 1-1 (not 2-1) up to $50 million.28

Also included under the SBIC program are Impact Investment SBICs. They are similar to SBICs in every way, except that they tend to make smaller investments and, most important, they are created specifically to provide investments in companies owned by socially and economically disadvantaged entrepreneurs.

Although they are not technically part of the SBIC program, the New Markets Venture Capital Program and the Rural Business Investment Program are modeled on the SBIC program. The two programs combined provide equity capital to entrepreneurs with companies in rural, urban, and specially designated low- and moderate-income (LMI) areas.29

Overall, the SBIC program has clearly been a strong contributor to the emergence and success of entrepreneurship in America. It has increased the pool of equity capital available for entrepreneurs, and made this capital obtainable by underserved entrepreneurs. The general private equity industry has a reputation for being interested only in investments in technology entrepreneurs. In contrast, SBICs have a reputation for doing “low-tech” and “no-tech” deals. Both reputations are unfounded. Traditional private firms such as Thoma Cressey Equity Partners invest in later-stage “no-tech” companies, and SBICs such as Chicago Venture Partners invest in technology companies. In fact, the SBIC program currently has invested or committed about $30.1 billion in small businesses, with the SBA’s share of capital at risk about $13.9 billion. In FY2018, the SBA committed to guarantee $2.52 billion in SBIC small business investments.30 Figure 9-3 lists a sample of successful SBIC-backed companies.

FIGURE 9-3 SBIC-Backed Companies

Source: Small Business Administration, www.sba.gov/aboutsba/sbaprograms/inv/INV_SUCCESS_STORIES.html.

A free directory of operating SBICs can be obtained by calling the SBA Office of Investments or going online at http://www.sba.gov/content/sbic-directory. There is also a national SBIC trade association at www.Sbia.Org.

Initial Public Offerings

Every year, hundreds of entrepreneurs raise equity capital by selling their company’s stock in the public market. This process of selling a typical minimum of $5 million of stock to institutions and individuals is called an initial public offering (IPO) and is strictly regulated by the SEC. The result is a company that is “publicly owned.” For many entrepreneurs, taking a company public is the ultimate statement of entrepreneurial success. They believe that entrepreneurs are recognized for one of two reasons: having a company that went bankrupt or having one that had an IPO. Timing is everything with an IPO issue. The late 1990s were record-breaking days of glory, the early 2000s were miserable, and IPOs then began to rebound through 2007. In 2018, there were 190 IPOs.

When a company “goes public” in the United States, it must meet a new standard of financial reporting, regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. All the financial information of such a company must be published quarterly and distributed to the company’s shareholders. Therefore, because of the SEC’s public disclosure rules, everything about a publicly owned company is open to potential and present shareholders. Information such as the president’s salary and bonus, the company’s number of employees, and the company’s profits are open to the public, including competitors.

Going public was extraordinarily popular during the 1990s. From 1970 to 1997, entrepreneurs raised $297 billion through IPOs. More than 58% of this capital was raised between 1993 and 1997.31 In 1999 and 2000, entrepreneurs were the highly sought-after guests of honor at a record private equity feast. The money flowed, and entrepreneurs could, in essence, auction off their business plans to the highest bidders. Average valuations of high-tech start-ups rose from about $11 million in 1996 to almost $30 million in 2000.32 But by the summer of 2000, as the Nasdaq began to crash, venture capital investments began to slow dramatically. As Table 9-6 (see next page) shows, the boom began to end in 2000 when the public markets became less interested in hyped technology companies that had no foreseeable chance of making profits. According to research by PricewaterhouseCoopers, in the first three months of 2001, venture capitalists reduced their investments in high-tech start-ups by $6.7 billion—a 40% drop from the previous quarter. In the first quarter of 2001, only 21 companies went public compared with 123 in the same quarter a year earlier.

TABLE 9-6 Number of Initial Public Offerings

For firms that are still committed to going public with an IPO issue, patience had better be a core competency. Venture Economics, a research firm that follows the venture capital industry, studied the time it takes a company to go from its first round of financing to its initial public offering. In 1999, a company took an average of 140 days; two years later, that average had surged to 487 days—a jump of 247%. There was more than 10 years between the time Lyft received its first round of capital and its IPO in 2019.

1990s IPO Boom

The stock market boom of the 1990s was historic. In 1995, Netscape went public despite the fact that it had never made a profit. This was the beginning of the craze for companies going public even though they had no profits. In the history of the United States, there has never been another decade that had as many IPOs or raised as much capital. Barron’s called it one of the greatest gold rushes of American capitalism.33 Another writer called it “one of the greatest speculative manias in history.”34

The frothy IPO market was not limited to technology companies. On October 19, 1999, Martha Stewart took her company public, and the stock price doubled before the end of the day. Vince McMahon, the onetime owner of the World Wrestling Federation, took his company public the same day. Disappointingly, the results were not as good as Martha’s. The stock increased only a puny 48.5% by the day’s end! In 2000, when many Internet companies were canceling their initial public offerings, Krispy Kreme was the second-best-performing IPO of the year.35

Because the public markets were responding so positively to IPOs in the 1990s, companies began racing to go public. Before 1995, it was customary for a company to have been in business for at least three years and have shown four consecutive quarters of increasing profits before it could do an IPO. The perfect example was Microsoft. Bill Gates took it public in 1986, more than a decade after he had founded it. By the time Microsoft went public, it had recorded several consecutive years of profitability.

But as stated earlier, the Netscape IPO in August 1995 changed things for the next five years. In addition to having no profit, Netscape was very young, having been in business for only 16 months. By the end of 1999, the Netscape story was very common.36 The absurdity was best described by a Wall Street analyst, who said, “Major Wall Street firms used to require four quarters of profits before an IPO. Then it went to four quarters of revenue, and now it’s four quarters of breathing.”37

This IPO euphoria created unparalleled wealth for entrepreneurs, especially those in Silicon Valley’s technology industry. At the height of the boom in 1999, it was reported that Silicon Valley executives held $112 billion in stock and options. This was slightly more than Portugal’s entire gross domestic product of $109 million.38

As all this information shows, entrepreneurs were using IPOs to raise capital for the company’s operations as well as to gain personal wealth.

Public Equity Markets

After a company goes public, it is listed and traded on one of several markets in the United States. More than 13,000 companies are listed on these markets. The three major and most popular markets are the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the NYSE MKT LLC (formerly known as AMEX/American Stock Exchange), and the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations (Nasdaq). Let us look at each in detail.

NYSE

With its start in 1792, the New York Stock Exchange is the oldest trading market in the world. It also has the largest valuation. These two facts are the reason that the NYSE is called the “Cadillac of securities markets.” Companies listed on this market are considered the strongest financially of the companies on the three markets. In order to be listed on the NYSE, the value of the company’s outstanding shares must be at least $40 million, and its annual earnings before taxes (EBT) in the most recent year must be at least $5 million.39 Companies listed on this market are the older, more venerable companies, such as General Electric, and McDonald’s. In 2018, the total market value of all companies listed on the NYSE was $28.5 trillion.40

NYSE MKT LLC

The NYSE MKT LLC Exchange is the world’s largest market for foreign stocks and the second-largest trading market. The market value of a listed company must be at least $3 million, with an annual EBT of $750,000. Formerly known as the AMEX, the NYSE MKT exchange trades in both a human and an electronic format. The companies whose securities trade on the NYSE MKT are primarily those with smaller market capitalization.

Nasdaq

The Nasdaq market opened in 1971 and was the first electronic stock market. More shares (an average of 6.4 billion per trading day)41 are traded over this market than over any other in the world.42

The minimum market value for companies listed on this market is $1 million. There is no minimum EBT requirement. That is why this market, with more than 5,000 listings, is the largest in the world. The Nasdaq is heavily filled with tech, biotech, and small-company stocks. Trading on this market is done electronically. All the technology companies that went public in the 1990s did so on the Nasdaq market. But that has now changed. The NYSE has been the choice for IPOs like Pinterest, Uber, and Slack.

Reasons for Going Public

Entrepreneurs take their companies public for several reasons. The first is to raise capital for the operations of the company. Because the money is to be used to grow the company rapidly, the equity capital provided through an IPO may be preferred over debt. In the cases of the tech companies of the 1990s that had negative cash flow, they could not raise debt capital. Only equity financing was available to them.

Even if a company can afford debt capital, some entrepreneurs prefer capital from an IPO when it is relatively cheap. Historically, the cost of IPO capital has been lower than the cost of debt. (Recently, however, debt capital has been less expensive.) Let us look at the math. Over the history of the Dow Jones Industrial Average, the average P/E ratio has been 15.5.43 This means that investors have been willing to pay $15.50 for every $1 of earnings. Therefore, the cost of this capital has been 6.5% ($1/$15.50). The cost of debt to an operating company in the United States during the period 1947–2014 has been 9.84%,44 indicated by the US prime rate, an index of the most common interest rates offered at a given time by US banks to their commercial clients. Since 2015, the prime rate has decreased to 5.50 in December 2018.45

Another reason for going public is that it can be easier to recruit and retain excellent employees by giving them publicly traded stock as part of their salaries. This allows employees to benefit personally when the value of the company increases as a result of their hard work.

Still another good reason is that an IPO provides the entrepreneur with another form of currency that can be used to grow the company. In the 1990s, companies’ stock was being widely used as currency. Instead of buying other companies with cash, many buyers paid the sellers with their stock. The seller would then hold the stock and benefit from any future increases in its value. In fact, many deals did not close or were delayed in closing because the seller wanted the buyer’s stock instead of cash. This was the case when Disney purchased the ABC network. Disney wanted to pay cash, but the members of the ABC team held out until they received Disney stock. Their reasoning was that $1 worth of Disney’s stock was more valuable than $1 cash. They were willing to make the assumption that, unlike cash, which depreciates as a result of inflation, the stock would appreciate.

The final reason for going public is to provide a liquidity exit for the stockholders, including employees, management, and investors.

Reasons for Not Going Public

Taking a company public is extremely difficult. In fact, less than 20% of the entrepreneurs who attempt to take a company public are successful.46 And the process can take a long time—as long as two years. Also, completing an IPO is very expensive. The typical cost is approximately $500,000. Then there are additional annual costs that must be incurred to meet SEC regulations regarding public disclosure, including the publication of the quarterly financial statements.

By the time most companies go public, they have received financing from family and friends, from angels, and at least two rounds from institutional investors. As a result, most founders will be lucky if they retain 10% ownership. The exception to this rule is Jeff Bezos, who owned 16.2% of Amazon.com. In the fall of 2018, that stake was worth $130.7 billion.47

One of the greatest problems with going public is that most of the stock is owned by large institutional investors, which have a short-term focus. They exert continual pressure on the CEO to deliver increasing earnings every quarter.

The final reason for not going public is that while funds that the company receives when stock is sold can be used for operations right away, stock owned by the key management team cannot be sold immediately. SEC Rule 144 says that all key members of the company (officers, directors, and inside shareholders, including venture capitalists) cannot sell any of their stock. These key members own “restricted stock,” or stock that was not registered with the SEC. This is in contrast to the shares of stock issued to the public at the IPO, which are unrestricted.

The holding period for restricted stock is two years from the date of purchase. After that period, the restricted stockholders may sell their stock as long as they do not sell more than 1% of the total number of shares outstanding in any three-month period.48 For example, if the entrepreneur owns 1 million of the 90 million shares of outstanding common stock, she may not sell more than 900,000 shares of the stock in a three-month period.

Control

One negative myth about going public is that if the entrepreneur owns less than 51% of the company, he loses control. This is not true. Founders including Sergey Brin, Larry Page, Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, and Michael Dell own less than 51% of their companies, but they still have control. The same is true of the Ford family, which owns only 2% of Ford Motor Company. However, this ownership is in the form of Class B shares, which provide them with 40% of the voting power. Bill Ford, the current executive chair, is the company’s largest shareholder and a descendant of company founder Henry Ford.49

The key to having control is having influence on the majority of the voting stock. In some firms, some of the stock may be nonvoting stock, also known as capital stock. The entrepreneur, his family, and board members may own virtually none of the nonvoting stock but a majority of the voting stock. This fact, along with the entrepreneur being in a management position and being the one who determines who sits on the board of directors, keeps him in control.

The IPO Process

As has been stated earlier, taking a company public can be expensive and time-consuming for the entrepreneur. But when it is done right and for the correct reasons, it can be very rewarding.

While it can take up to 24 months to complete an IPO, investment-banking firm William Blair & Company said that 52 to 59 weeks is the norm.

Bessemer Venture Partners, a leading venture capital firm, accurately described a simplified step-by-step IPO process:

1. The entrepreneur decides to take the company public to raise money for future acquisitions.

2. He interviews and selects investment banks (IBs).

3. He meets with the IBs that will underwrite the offering.

4. He files the IPO registration with the SEC.

5. The SEC reviews and approves the registration.

6. The IBs and the entrepreneur go on a “road show.”

7. The IBs take tentative commitments.

8. IPO.

Let us discuss these steps in more detail.

The IPO Decision

The entrepreneur’s decision to do an IPO can be made almost the day she decides to go into business. Some entrepreneurs articulate their plans for going public in their original business plan. In starting the business, one of their future objectives is to own a public company. Others may decide to go public when they get institutional financing. For example, a venture capitalist may provide them with financing only if they agree to go public in three to five years. In such a case, the entrepreneur and the investor may make the decision jointly.

Other entrepreneurs may decide to go public when they review their three- to five-year business plan and realize that their ability to grow as fast as they would like will be determined by the availability of outside equity capital—more than they can get from institutional investors.

Interviews with and Selection of Investment Banks

Once the decision to go public has been made, the entrepreneur must hire one or more investment banks to underwrite the offering. This process of selecting an IB is called the “bake-off.” Ideally, several IBs that are contacted by the entrepreneur will quickly study the company’s business and then solicit, via presentations and meetings, the entrepreneur’s selection of their firms. The IB’s compensation is typically no more than 7% of the capital raised.

Underwriter(s) Meetings

After the IBs are selected, the entrepreneur will meet with them to plan the IPO. This process includes determining the company’s value, the number of shares that will be issued, the selling price of the shares, and the timing of the road show and the IPO.

In typical public offerings, the underwriters buy all of the company’s shares at the initial offer price and then sell them at the IPO. When underwriters make this type of agreement with the entrepreneur, this is called a firm commitment.

There are also underwriters that make “best-efforts” agreements. In this case, they will not purchase the stock, but will make every effort to sell it to a third party.

IPO Registration

The entrepreneur’s attorney must file the registration statement with the SEC. This is a two-part document. The first part is called a prospectus and discloses all the information about the company, including the planned use of the money, the valuation, a description of management, and financial statements. The prospectus is the document given to potential investors.

The first printing of this prospectus is called a red herring because it contains warnings to the reader that certain things in the document might change. These warnings are printed in red ink.

The second part of the document is the actual registration statement. The four items disclosed are:

• Expenses of distribution

• Indemnification of directors and officers

• Recent sales of unregistered securities

• Exhibits and financial statement schedules50

SEC Approval

The SEC reviews the registration statement in detail to determine that all disclosures have been made and that the information is correct and easy to comprehend. The reviewer can approve the statement, allowing the next step in the IPO process to commence; delay the review until changes are made to the statement that satisfy the reviewer; or issue a “stop order,” which terminates the statement registration process with a disapproval decision.

The Road Show

Once approval of the registration statement has been obtained, the entrepreneur and the IB are free to begin the process of marketing the IPO to potential investors. This is called the road show, where the entrepreneur makes presentations about the company to the potential investors that the IB has identified.

Investment Commitments

During the road show, the entrepreneur makes a pitch for why the investors should buy the company’s stock. After each presentation, the IBs will meet with the potential investors to determine their interest. The investors’ tentative commitments for an actual number of shares are recorded in the “book” that the IB takes to each road show presentation.

The IB wants to accumulate a minimum number of tentative commitments before proceeding to the IPO. IBs like to have three tentative commitments for every share of stock that will be offered.51

The IPO

On the day when the IPO will occur, the investment bank and the entrepreneur determine the official stock selling price and the number of shares to be sold. The price may change between the time the road show began and the day of the IPO, as a result of interest in the stock. If the tentative commitments were greater than a 3-to-1 ratio, then the offering price may be increased. It may be lowered if the opposite occurred. That is exactly what happened to the stock of Wired Ventures, which attempted to go public in 1996. Originally the company wanted to sell 4.75 million shares at $14 each. By the date of the IPO, it made the decision with its IB, Goldman Sachs, to reduce the offering to 3 million shares at a price of $10 per share. One of the reasons for this change was the fact that hours before the stock had to be officially priced for sale, the offer was still undersubscribed by 50%. Even at this lower price, though, the IPO never took place. Wired Ventures was not able to raise the $60 million it sought, and it incurred expenses of approximately $1.3 million in its attempt to go public.

Choosing the Right Investment Banker

As the preceding information shows, the ability to have a successful IPO is significantly dependent on the IB. The most critical features of an IB are its ability to value the company properly, assist the attorney and the entrepreneur in developing the registration statement, help the entrepreneur develop an excellent presentation for the road show, access its database to reach the proper potential investors and invite them to the presentation, and sell the stock. Therefore, the entrepreneur must do as much as possible to select the best IB for his IPO. Here are a few suggestions:

• Identify the firms that have successfully taken companies public that are similar to yours in size, industry, and amount to be raised.

• Select experienced firms. At a minimum, the ideal firm has underwritten two deals annually for the past three years. The firms that are underwriting eight deals per year, or two each quarter, may be too busy to give your deal the attention it needs. Also eliminate those whose deals consistently take more than 90 days to get registration approval.

• Select underwriters that price their deals close to the stock’s first-day closing. If an underwriter prices the stock too low, so that the stock increases dramatically in price by the end of the first day, then the entrepreneur sold more equity than she needed to. For example, if the initial offering was 1 million shares at $5 per share and the stock closed the first day at $10 per share, then the stock was underpriced. Instead of raising $5 million for 1 million shares, the entrepreneur could have raised the same amount for 500,000 shares had the underwriter priced the stock better.

• Select underwriters that file planned selling prices that are close to the actual price at the initial offering. Some underwriters file at one price, then try to force the entrepreneur to open at a lower price so that they can sell the stock and their investors can reap the benefits of the increase. This maneuver, when it is done, usually takes place a day or so prior to the IPO, with the underwriter threatening to terminate the offering if the price is not reduced. To minimize the chances of this happening, the entrepreneur should select only underwriters that have a consistent pattern of filing and bringing the stock to the market at similar prices.

• Select underwriters that have virtually no experience with failing to complete the offering. Companies that file for an IPO but do not make it are considered “damaged goods” by investors.

• Get an introduction to the investment banker. Never cold-call the banker. The company’s attorney or accountant should make the introduction.52

Direct Public Offerings

In 1989, the SEC made it possible for companies that are seeking less than $5 million to raise it directly from the public without going through the expensive and time-consuming IPO process described earlier. This direct process is aptly called a direct public offering, or DPO. In a DPO, shares are usually sold for $1 to $10 each without an underwriter, and the investors do not face the sophisticated investor requirements. Forty-five states allow DPOs, and the usual legal, accounting, and marketing fees are less than $50,000.

There are three DPO programs that have been used by thousands of entrepreneurs. The programs are:

1. Regulation D, Rule 504, which is also called the Small Corporate Offering Registration, or SCOR

2. Regulation A

3. Intrastate

The SEC has a free pamphlet entitled “Q & A: Small Business and the SEC—Help Your Company Go Public” available on its website at www.sec.gov. Let us discuss each DPO program in more detail.

• Small Corporate Offering Registration. In the Small Corporate Offering Registration, or SCOR, program, the entrepreneur has 12 months to raise a maximum of $1 million. Shares can be sold to an unlimited number of investors throughout the country via general solicitation and even advertising. One entrepreneur who accessed capital via a DPO was Rick Moon; the founder of Thanksgiving Coffee Co., Rick raised $1.25 million in 1996 for 20% of his coffee and tea wholesaling company, which had annual revenues of $4.6 million. He aggressively advertised the offering to his suppliers and customers on his website, in his catalog, on his coffee-bean bags, and on the bean dispensers in stores.53

• Regulation A Offering. Under the Regulation A program, an entrepreneur can raise a maximum of $5 million in 12 months. Unlike offerings under SCOR, where no SEC filings are required, offerings under Regulation A must be filed with the SEC. Otherwise, all the attributes of SCOR are applicable to Regulation A. Dorothy Pittman Hughes, the founder of Harlem Copy Center, with $300,000 in annual revenues in 1998, began raising $2 million under this program by offering stock for $1 per share. The minimum number of shares that adults could buy was 50; for children, the minimum was 25.54

• Intrastate program. The intrastate program requires companies to limit the sale of their stock to investors in one state. This program has other significant differences from SCOR and Regulation A. First, there are no federal laws limiting the maximum that can be raised or the time allowed. These two items vary by state. The other difference is that the stock cannot be resold outside the state for nine months.

DPOs are best suited for historically profitable companies with audited financial statements and a well-written business plan. Shareholders are typically affinity groups that are somehow tied to the company, such as customers, employees, suppliers, distributors, and friends. After completing a DPO, the company can still do a traditional IPO at a later date. Real Goods Trading Company did just that. In 1991, it raised $1 million under SCOR. Two years later, it raised an additional $3.6 million under Regulation A. Today, its stock is traded on the Nasdaq market.

DPOs have a few negative aspects. First, it is estimated that more than 70% of those companies that register for a DPO fail, for various reasons. But the greatest drawback is the fact that there is no public market, like the NYSE, for DPO stock. Such an exchange brings sellers and buyers together, and that does not exist for DPOs. Therefore, the ability to raise capital is negatively affected by the potential investors’ legitimate concerns that their investment cannot be made liquid easily. Another problem is that the absence of a market leaves the market appreciation of the stock in question. One critic of DPOs said, “There is no liquidity in these offerings. Investors are stepping into a leg-hold trap.”55 As a result, DPO investors tend to be long-term focused. Trading in the stock is usually arranged by the company or made through an order-matching service that the company manages. The shareholders can also get liquid if the company is sold, the owners buy back the stock, or the company does a traditional IPO.

Because this is a book about finance, not about law, we have intentionally avoided a long discussion of the legal aspects of entrepreneurship. That does not mean that you should ignore the legal ins and outs of running a business or getting one started. One great resource that comes highly recommended from my students is the book The Entrepreneur’s Guide to Business Law by Constance Bagley and Craig Dauchy.

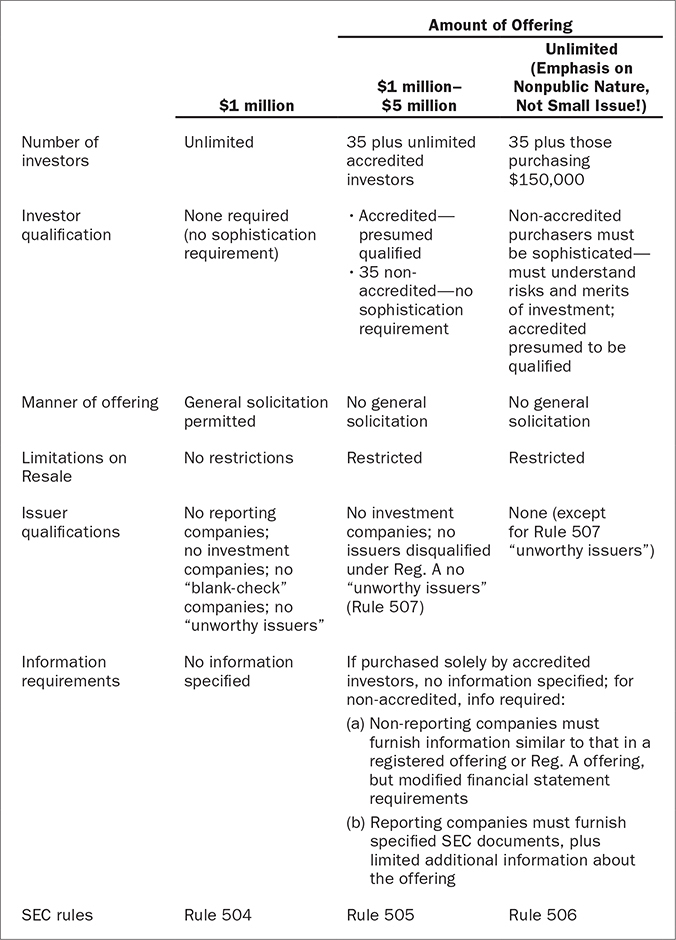

The Financing Spectrum

There is an old dog food commercial that features a frolicking puppy changing into a mature dog before our eyes. The commercial reminds pet owners that as their dogs grow, the food that fuels them needs to change too. Businesses are the same way with equity financing. As a business evolves from an idea into a mature company, the type of financing it requires changes.

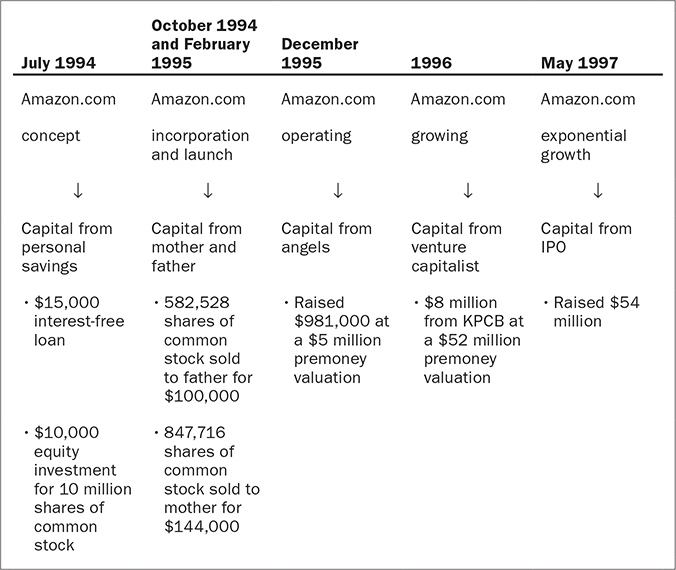

An actual entrepreneur who raised money from almost all the sources of capital on that spectrum was Jeff Bezos. Figure 9-4 shows when Bezos raised capital and from whom.

FIGURE 9-4 Jeff Bezos’s Financing Spectrum