11

Taking a Job with an Entrepreneurial Firm

Introduction

One of the unexpected discoveries resulting from staying in touch with students several years after they graduate has been that a large percentage of those who indicate that they are involved in entrepreneurship as employees in, not cofounders of, an entrepreneurial firm. They had resigned from their safe job with a successful investment banking, consulting, or manufacturing company and had taken a job with a start-up firm. How does a person make such a decision to leave the security of a well-established, in many instances Fortune 500, company to work for a high-risk venture in its embryonic stages of development?

The following case study, followed by an analysis of the situation, should be used as a template for answering these questions: Should I leave my job to take a job with a start-up? How should I do a financial analysis of the decision?

Case Study: Considering a Job Offer from an Early-Stage Company

In her Chicago home on a warm Friday afternoon in June, Nailah Johnson hung up the phone. She was happy. John Paul, founder of AKAR and Johnson’s potential future employer, had said as their conversation ended, “Tell me what it would take to get you on board.”

For many reasons, Johnson was excited about joining an entrepreneurial firm and possibly much later even buying her own business. She recalled including this goal in the essays that had helped her gain admission to her MBA program two years earlier. The role that Paul wanted Johnson to have at AKAR was appealing: a director of sales and marketing position with significantly more responsibility than she currently had, and with a possible promotion to vice president in less than 12 months. Johnson had heard about the many downsides and upsides of positions with an early-stage company. If the company failed, she could face a direct financial loss because employees at start-ups were paid low salaries. On the other hand, the financial rewards could be lucrative if the employees owned part of the company and its value increased.

Johnson had joined Motorola Solutions, a Fortune 1000 company, in 2015 as a director of operations. She had recently been promoted to a senior director of sales role. She and her husband enjoyed comfortable professional and social lives in Chicago. Just two days earlier, Johnson had informed her husband that she was pregnant with their first child. They expected this new addition to their family to increase their annual budget by $19,000. Early in their marriage, they had envisioned her becoming a full-time mother when the time came.

Still giddy from Paul’s call, Johnson sat at her kitchen table, thinking about what he had said, “The sooner we can start you, the better.” Until that moment, Johnson would have predicted that she would accept the position with AKAR on the spot, on almost any terms that sounded reasonable; after all, she had invested many months and a great deal of energy in making the offer happen. Now, as the costs and benefits of the position swirled through her mind, she felt unsure about what terms to request. Johnson owed Paul an answer in five days, but she was not sure that she could determine what she wanted even if she had three months. She also considered rejecting this opportunity because the risk was too high and the timing was poor. Finally, she wondered, if she took this or any other job, would she ever become an actual entrepreneur, or would she always be simply someone’s employee? Should she pursue acquiring her own company instead?

In many ways, Johnson’s career was typical for an MBA student. Thus, despite her interest in entrepreneurship, seriously considering an offer from an early-stage company was new territory for her. As Johnson reflected on the offer’s pros and cons, she thought back to the path that had led her here.

Walking the Straight and Narrow

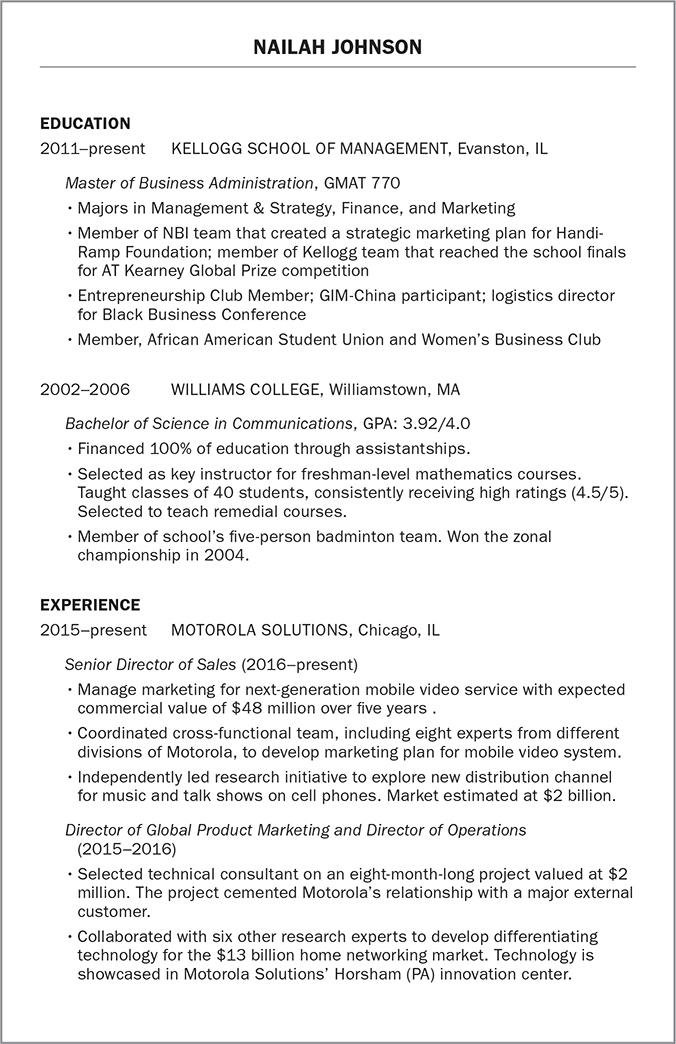

Johnson had attended Williams College, graduating near the top of her class (see Figure 11-1 on next spread for Johnson’s résumé). Immediately after college, she began her career at Sun Microsystems and later moved to Motorola Solutions. Although she enjoyed working on mobile solutions, she found the business issues related to them even more interesting: Who were their target segments? What were the best ways of distributing and marketing the products? What kinds of new products were most likely to survive?

FIGURE 11-1 Nailah Johnson’s Résumé

These interests led to Johnson’s application to the MBA program. Because she had always had an interest in start-ups, she took several courses in entrepreneurship and joined the entrepreneurship club. As part of these student activities, Johnson enjoyed discussing entrepreneurship, especially the potential for new high-tech products, but her career goals remained focused on larger-company opportunities. In line with this, she pursued a marketing manager position at Motorola and was pleasantly surprised to receive an offer. The new position came with a salary of $115,000 (a 30% raise that put her in the 28% tax bracket), bonus potential of approximately 25% of her salary, and responsibilities for marketing a next-generation mobile video device. Johnson loved the work and was already in line for a promotion to business development manager.

Taking on the new position had not been the only change in her life: she had married Naeem, her classmate, soon afterward. They had purchased a $400,000 two-bedroom condominium in Chicago. The Johnsons made a 20% down payment (their entire savings) and secured a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage at 6% interest. The mortgage and their school loans were their only debts. Their monthly assessment, taxes, and insurance were approximately 40% of the mortgage. All other household expenses, including telephone, electricity, cable, gas, and groceries, were approximately 35% of the monthly mortgage. They owned two cars, which were paid in full.

By the time Johnson was considering a position with AKAR, Naeem had also been promoted at Kraft; his salary was $105,000, with a bonus of approximately 20%. His company’s health, medical, dental, and vision care insurance were all free. Together, the couple led a busy but enjoyable life, building their career experience, earning their MBAs, and taking vacations. They spent approximately 25% of Naeem’s monthly salary on recreational activities. Despite some tuition reimbursement from their companies, they had amassed significant student debt.

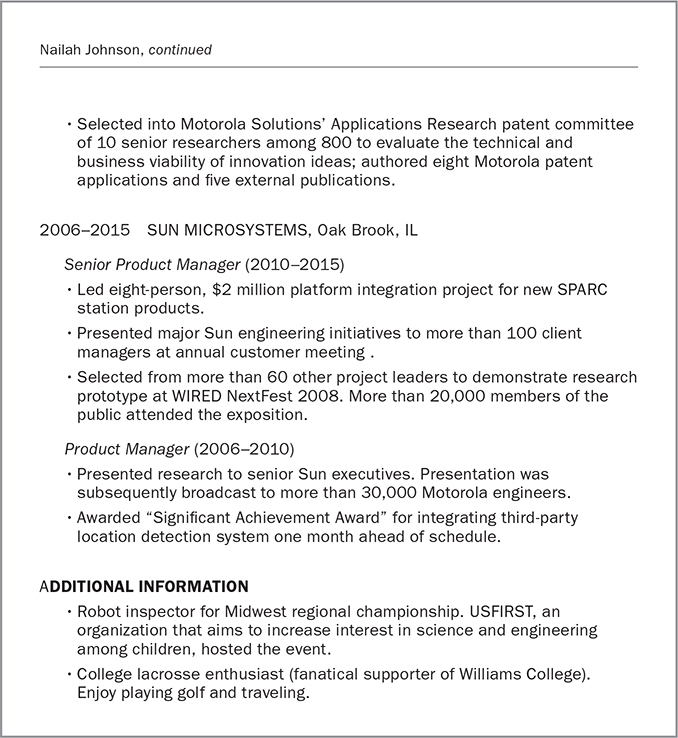

Figure 11-2 (see next page) is a summary of all of Nailah’s loans processed by the financial aid office as of June 14, 2018. The principal amounts listed are the original principal balances. These amounts do not reflect any payments made on these loans. Loans from other institutions are not included on this form.

FIGURE 11-2 Loan Summary

The Search for More

While she had been successful in her career path to date, for the last several months, Johnson had found that several questions were frequently on her mind: Is this all there is, career-wise? How can I keep more of the value that I am creating for myself? How can I become a millionaire without risking everything? These questions also arose when she recalled how much she had enjoyed her entrepreneurship classes or heard news of others’ entrepreneurial accomplishments.

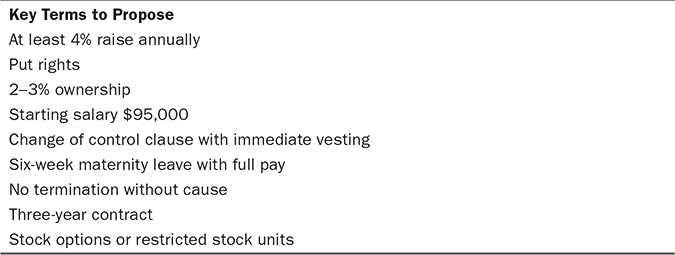

According to her alumni magazine, Ariel Grant, a recent alumna had raised $4 million in angel and early-stage venture capital for the company she founded, which provided software that allowed computers to search automatically for information related to documents that the user was working on. Grant gave “put rights” to some of her managers who owned stock in the company. She had originally given these employees restricted stock units (RSUs) when they were hired.

Raymond Robinson, a friend of Johnson’s, was already a vice president with a 2% ownership stake after exercising the stock options given to him when he was hired by a wireless technology company that had just completed a successful initial public offering (IPO). Robinson was now a multimillionaire. His stock options had originally been scheduled to vest 20% annually after his second year of employment. However, the IPO triggered the “change in control” clause, resulting in the immediate full vesting of 100% of his options. “That could be me,” Johnson thought when she heard such stories.

Four months ago, after the completion of a very challenging project at work, Johnson had decided to stop sitting on the sidelines of entrepreneurship. She began reading entrepreneurship magazines and books, reaching out to friends who she thought would know of opportunities with early-stage companies, scouring the business school’s alumni database for people in small firms, and setting up as many informational interviews as she could. Johnson also connected with a recruiter who specialized in placements at early-stage firms and a business broker who could show her businesses for sale. The time she spent on the search, on top of her responsibilities at work and at school, left Johnson with almost no space in her weekly schedule for fitness, social activities, or spending time with Naeem. But it felt like the right thing to do.

Despite Johnson’s enthusiasm for the search, months passed without major progress. If anything, like a corporate Goldilocks, she discovered many of the things she was not seeking in a new opportunity: she rejected several positions that had initially appeared to be promising—they were too risky (a five-person software company in the initial fund-raising stage), not exciting enough (a firm that provided marketing solutions to the paper industry), or too strange (a venture that developed software so proprietary that the founders asked all employees to sign nondisclosure agreements—daily).

But two months earlier, Johnson’s luck had changed when she met John Paul. Johnson had signed up to meet him through the entrepreneurship center’s Entrepreneur-in-Residence program (EIR), through which entrepreneurs and principal investors spent a full day meeting in 30-minute sessions with individual students to answer questions and provide experience-based insights.

AKAR: The Opportunity

John Paul was only 46 years old, but he had already sold two companies. According to an article Johnson had read, AKAR, Paul’s most recent venture, was very promising and had received significant industry attention. The article also characterized Paul as a “gambler with great judgment—or maybe great luck.”

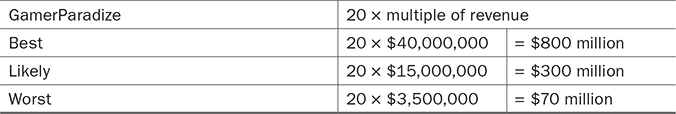

After dropping out of Grambling University, a historically black university, in 1989, Paul had worked as a computer programmer for a series of video game manufacturers before moving into roles in operations and database design. He prided himself on being self-taught in most aspects of business, from finance to marketing: “Best teachers I ever had? Trial and error,” he often said. Paul had sold his first company, GamerParadize (launched out of his apartment six years earlier), one of the first online gaming portals, to Midway Games for $40 million (20 times its revenues) in its third year of operations. Paul owned 60% of the company, and the top two levels of management (vice presidents and managers), consisting of nine people, owned 20%. At closing, the four vice presidents shared $4 million. The remaining 20% went to the investors, who had invested $2 million five years earlier.

Paul was much more ambitious for his second company: to fund X-Cell, an Internet design and security firm, he had obtained venture backing of $15 million. He had “call rights” agreements with all managers who owned stock in the company, giving him the option to buy back the stock at any time at 3 times the original price. Unfortunately, because of a patent-related lawsuit, X-Cell had to stop marketing its main security product, and Paul and the investors decided to sell off all the firm’s assets in 2016, losing a portion of their investment.

AKAR was Paul’s current company. Based in Chicago, the tech company had been built around a simple idea that Paul had developed with his chief technology officer (CTO), who had worked with Paul at X-Cell: distributing digital information across several geographically dispersed storage sites to store it more securely, reliably, and cost-effectively. AKAR was commercializing this idea as an online data storage service while offering commercial software for firms that were seeking to build their own storage capabilities. With this value proposition, AKAR was trying to capture a share of the $43 billion global data storage management services market, with an initial focus on the $3.3 billion US market for automated data backup services.

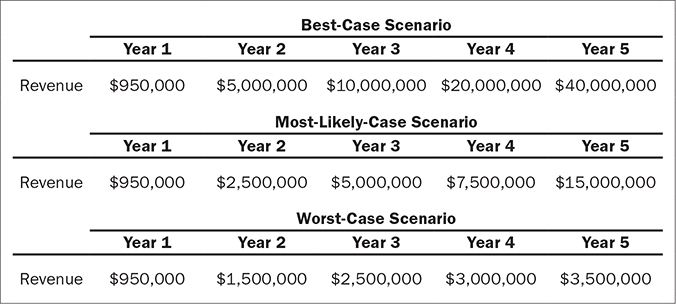

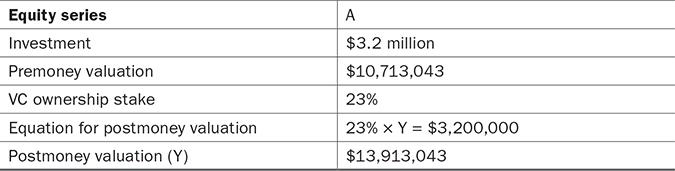

At the time that Johnson met Paul, AKAR had just launched the commercial version of its backup services. With only a few loyal customers in place, the firm’s revenues were minimal, but Paul—and many observers—was confident that that would change soon (see Figure 11-3 for AKAR’s pro forma financials). Paul had self-funded much of AKAR, but he had also received Round A financing of $3.2 million from a venture capital group in return for 23% of AKAR.

FIGURE 11-3 AKAR Financials (Pro Forma)

In addition to CEO Paul, AKAR had 14 employees; most of these were engineers with hardware and/or software experience, and several of them had come to AKAR directly from college. None of them, including Paul, was paid a six-figure salary. Paul believed that everyone should sacrifice salary for annual performance bonuses and company stock. The only other senior manager at AKAR was Mark Chin, the CTO. Chin had helped Paul build X-Cell. “My right- and left-hand man,” Paul often called him.

From the moment Johnson met Paul, she described the recruiting process as “casual, but intense.” For example, the day after the event where they first met, Paul called Johnson and told her how impressed he had been by her qualifications. “You’d make a heck of a marketing director,” Paul said numerous times. In the weeks that followed, they kept in close contact: three phone calls that lasted late into the night, several strings of e-mail correspondence, and two dinners. During these interactions, they discussed technology trends, the fit between Johnson and AKAR, sports, and Paul’s personal life. Johnson learned that Paul had been divorced and remarried (“Second time’s the charm, so far”) and had two elementary school–age stepchildren, a 132-foot yacht (“Want to sail her around the world—hopefully after selling this company”), and Type II diabetes (“For me, they’re not doughnuts, they’re dough-nots”).

One month ago, Paul had invited Johnson to meet the CTO and tour AKAR’s office, a hip loft space in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. The meeting with CTO Chin was similar to Johnson’s encounters with Paul: casual but intense. For almost two and a half hours, Chin discussed AKAR’s products, mission, and culture, rarely pausing to ask Johnson questions. When he did, it was typically to probe Johnson’s level of commitment to AKAR’s vision and mission. During the marathon interview, Chin used the phrase “John’s way” often, endowing it with an almost mythical quality. After the interview, Paul and Chin introduced Johnson to several of the other employees and took her out to dinner with a customer. On her way home, an exhausted Johnson called Naeem. “It’s like I already work there,” she told him.

Four days after the meeting, Paul called Johnson with good news: the team wanted to make her an offer. “But first,” Paul said, “it would mean a lot to us if you and Naeem came to ‘Shut Up and Sing’ in two weeks.” Johnson thought she had misheard Paul, until he explained: Shut Up and Sing was a party for all AKAR employees and their spouses or partners that Paul threw twice a year at his house. The two main ingredients were homemade sangria and karaoke.

Two weeks later, Johnson and her husband attended the party. Paul stayed by Johnson’s side most of the night, guiding her around his large lakefront home and introducing her as “guest of honor and future marketing director.” For Johnson, the night was a blur of smiling faces, handshakes, and her singing “Girls Just Wanna Have Fun” in front of about 50 people she barely knew. She also could not help but feel that the party had been a final test for her, to see how well she would fit at AKAR.

Four days later, Paul called, as enthusiastic about Johnson as ever. Johnson had expected an offer from Paul, even if only verbal. Instead, Paul had said, “Tell me what it will take to get you on board.”

Decisions, Decisions

As Johnson sat at her kitchen table, thinking about Paul’s words and the position with AKAR, Naeem returned from work. She smiled at him. “They want to hire me,” she said.

“Great news!” Naeem hugged her. “What’s their offer?”

Case Study Analysis

The following questions illustrate key items for Nailah to consider as she evaluates the opportunity with AKAR.

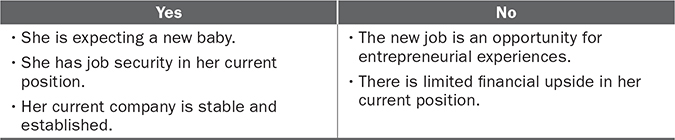

QUESTION 1: Should Nailah keep her job?

QUESTION 2: Should Nailah pursue the AKAR employment opportunity?

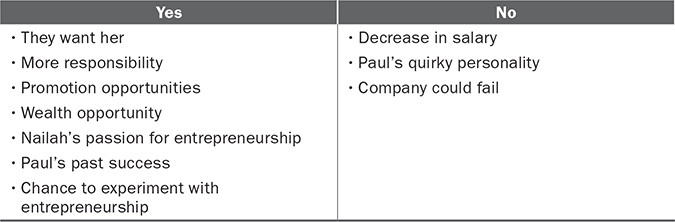

QUESTION 3: What are Nailah’s personal strengths and weaknesses?

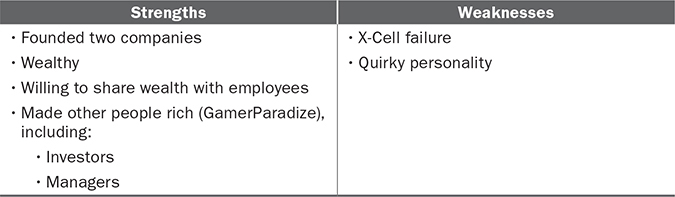

QUESTION 4: What are John Paul’s strengths and weaknesses?

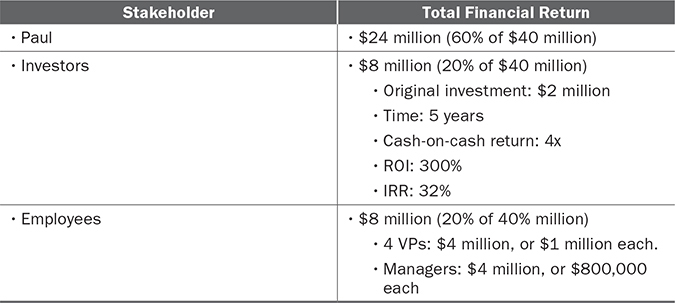

QUESTION 5: What was the value of GamerParadize to each stakeholder?

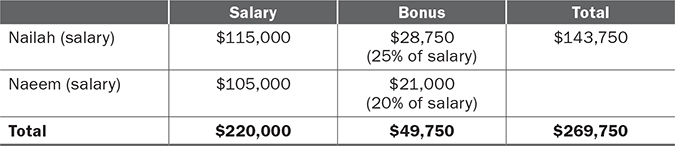

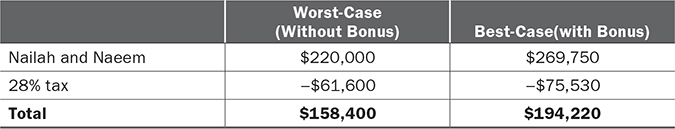

QUESTION 6: What is the Johnson family’s current maximum income?

QUESTION 7: What is the Johnson family’s after-tax cash flow?

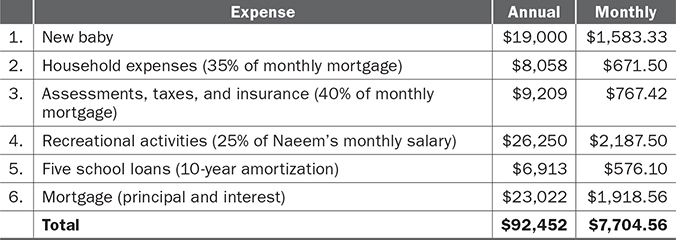

QUESTION 8: What is the Johnson family’s current budget?

QUESTION 9: What is the minimum amount of cash that Nailah needs to bring home if the Johnson family is to pay its expenses?

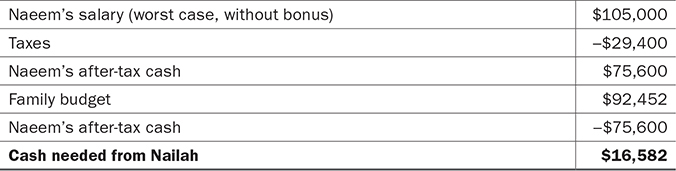

QUESTION 10: What should Nailah propose?

QUESTION 11: What is the difference between stock options and restricted stock units?

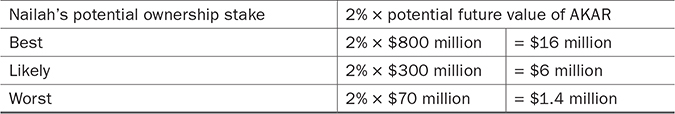

QUESTION 12: What is the potential future value of AKAR?

QUESTION 13: How much could Nailah make?

QUESTION 14: Is she entitled to 2% of the company or 2% of the new value of the company?

![]()

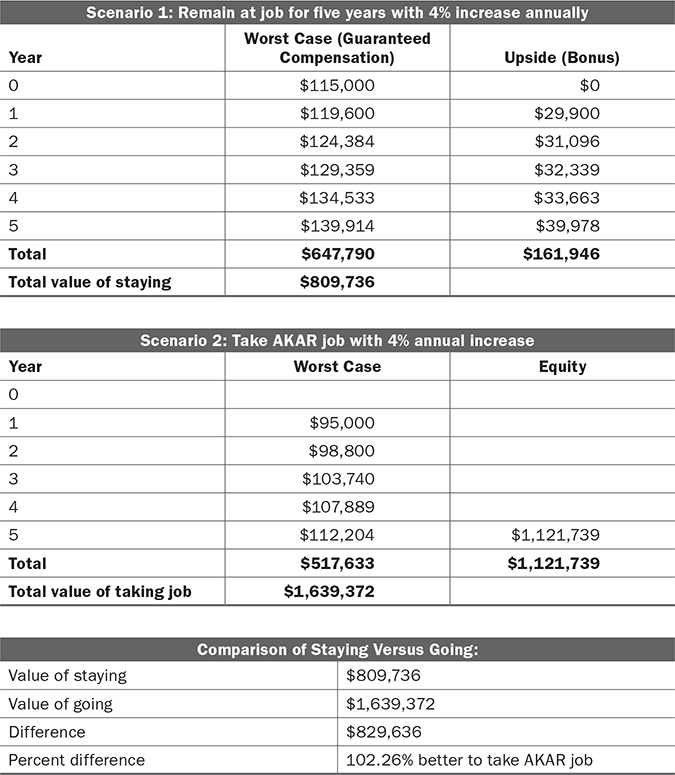

QUESTION 15: What is the starting point for Nailah’s value?

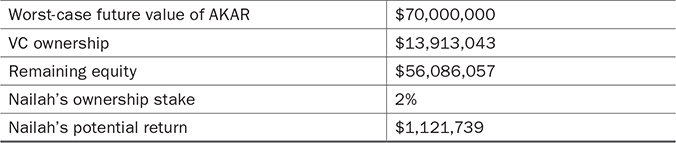

QUESTION 15A: What is the worst case for Nailah?

QUESTION 15B: What is the financial difference between staying and going?