THE SEVEN CLASSICAL VIRTUES

Virtues are not the stuff of saints and heroes. They are tools for the art of living.1

—KRISTA TIPPETT

HIDDEN IN FULL VIEW: NEUROLOGY CATCHES UP TO EVOLUTION AND ARISTOTLE

For 10,000 years, it has been only humans who have learned to thrive in diverse climates that range from the Artic to the Amazon even though we aren’t faster and stronger than other species. Physician, sociologist, and Yale professor Nicholas Christakis has asserted that human progress results from cultures defined by components of the “social suite”: friendship, cooperation, and social learning. Christakis’s research on shipwrecks between 1552 and 1855 illustrates this point. When virtues such as compassion and trust were present among those stranded and their leaders, shipwrecked crews tended to survive. When virtue was absent among the shipwrecked crews, the shipwrecked sailors died.2

Our negativity bias can blind us to the point that it is pro-social behavior such as collaboration and teamwork that makes human progress possible. This isn’t to suggest that human nature’s dark side of tribalism, cruelty, and violence has been eradicated. With the wrong conditions, evolution takes us where we do not want to go.3 The best that humans can do, no matter how dire or desperate our circumstances, is to practice virtue. In Greek mythology, Areté, the goddess of virtue, embodied what it meant to live right. At a crossroads, Areté appeared as a young maiden to Heracles. She offered Heracles a choice: glory earned from a life struggling against evil or comfort and pleasure made possible by wealth. Heracles chose struggle over comfort by achieving the moral agility of a hero to move quickly and easily to excel.

In the West about 2,500 years ago, this moral agility was achieved, according to Aristotle, by our habits: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.” In the East also about 2,500 years ago, Confucius said, “All people are the same; only their habits differ.” That said, it is incredibly demanding to create a habit of virtue in the face of pressure, uncertainty, and injustice.

Fast-forward 23 centuries. In the late nineteenth century, philosopher William James was one of the founders of psychology. This quote from James makes it clear that virtue preceded psychology, not the other way around: “We are spinning our own fates, good or evil, and never to be undone. Every smallest stroke of virtue or of vice leaves its ever so little scar. . . . Nothing we ever do is, in strict scientific literalness, wiped out.”4

In the twentieth century, psychology focused primarily on mental disorders. Emphasizing ill-being has helped millions to cope with mental health challenges. At the same time, it has become clear that the absence of ill-being does not ensure well-being, any more than the absence of illness ensures fitness. In contrast, Abraham Maslow stressed focusing on positive qualities in people, rather than treating them as a “bag of symptoms.” Maslow suggested that the healthiest societies are those in which “virtue pays.” He thought that this could start with early education that rewarded kindness and learning for learning’s sake, rather than focusing on doing well on external metrics like standardized test results.

In the 1960s, behaviorism ruled the day. The environment was emphasized as the primary cause of our behavior with no attention given to the brain or biology. Then, the pendulum swung to emphasize genetics, which suggested there wasn’t much we could do about behavior. In 2004, virtue made a comeback with positive psychology when Martin Seligman and Christopher Peterson comprehensively showed that virtues are considered a positive good by the vast majority of cultures. The essence of positive psychology is that it is the scientific study of life worth living.5 Once again, we fall forward toward the ancient Greeks.

At the end of the twentieth century, neuroscience caught up to Aristotle, revealing that we become what we practice—again, excellence is not an act, but a habit. Thanks to several decades of research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we now know that the brain is highly malleable. Neuroplasticity means that the brain has the ability to change constantly, grow, and remap itself over the course of our life. Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to modify its connections or rewire itself, which is important for learning, memory, and motor skill coordination. Each time you learn something new and practice it, your brain changes the structure of its neurons or increases the number of synapses between your neurons.

Once upon a time, we thought that one part of the brain was for emotions and the other for reason. Neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist makes clear that this is not true. The difference between the right and left hemispheres is attention. The right side of the brain pays attention to whether someone is friend or foe. It sacrifices accuracy for quickness. The left side pays attention to clarity of thought. It sacrifices quickness for clear thinking.

Once upon a time, we debated the issue of nature versus nurture. We now know that this debate is an outdated choice. The field of epigenetics makes clear that our behavior influences our genes and, conversely, our genes influence our behavior. In other words, the relationship between genes and behavior is fluid, not fixed.6

Virtue also isn’t fixed. Virtue is fluid and can be learned. And virtue is best learned through guided self-discovery. This highlights the brilliance of the Socratic method. Questions uncover insights about virtue and excellence that individuals and teams already know to be true. Virtue as a common language works because the concepts, like compassion, trust, and hope, are deeply engrained in all of us. Sheer ignorance is rarely our moral problem. More likely, our moral challenge is to act in concert with the knowledge that we already have. Our conscience faces an uphill battle against self-deception, immediate gratification, and fear. This is why the practice of virtue requires intentionality, skill, and support. No matter our age, every thought and action changes us ever so slightly in a direction that either elevates us or degrades us. While we can seek good with every action, we are equally capable of cultivating a habit for being self-centered through a series of callous or cruel acts that debase who we are and who we become.

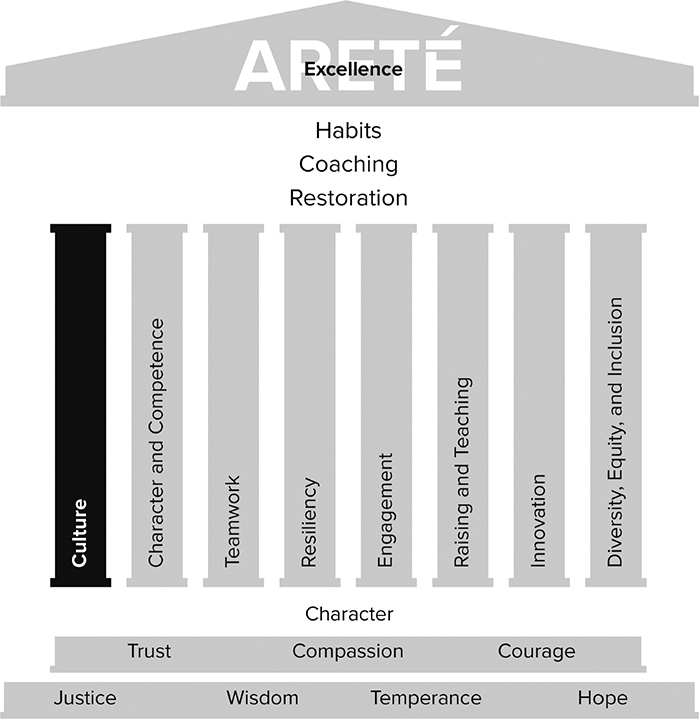

This chapter presents the seven classical virtues that have stood the test of time for as much as three millennia or longer. As the name “classical” would suggest, these virtues are universal, and, therefore, can be applied in any part of the world. This critical benefit means the virtues are our moorings to navigate changing markets and political forces. The virtues were the foundation of a 2,500-year-old leadership model known as Plato’s Academy. The mission of Plato’s Academy was to develop leaders of character, who would create a “good” society. You were not permitted to graduate from Plato’s Academy until you were 50! The conclusion was clear: society dare not put someone in a responsible leadership role before they had had sufficient time to “know thyself” and to demonstrate their ability to put virtue into action.

In real life, we usually do not explicitly unpack how individual virtues inform any human action. But in order to get a sense of each virtue and how it manifests itself in our lives and work, we will break them down and look at each one individually. Having this in mind should make the basic premise of the book understandable—that when we get better at who we are (that is, we practice virtue), we will get better at what we do (that is, we will achieve better performance).

TRUST: TRUST IS EFFICIENT

The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them.7

—ERNEST HEMINGWAY

For each of us, virtue operates along a spectrum. Virtue in general and trust in particular are far more complicated than thinking you have them or you don’t. So, the answer to the question of whether you are virtuous or not is yes.

So, what makes up trust? We use the words trust and faith as synonyms. They are rooted in the Latin words fides and fiducia, which means “faith.” Thus the root of the legal word fiduciary is faith. Fiduciary is also a moral word that means that leaders look out for the interests of others as if their interests were their own. Leaders who fulfill their legal and moral fiduciary commitment earn people’s trust. This is trust in action.

At an organizational level, trust makes us efficient, fast, and nimble. Trust is the basis of high-performing teams. We all have been on teams of bright, but egotistical people who can’t get out of their own way. We all have been on teams where people trust each other. Distrustful teams move slowly and cost a lot of money. Trusting teams move fast and save a lot of money. We can lead change more easily when trust is high. Trust can bind diverse teams to a common good.

Here’s a bit of evidence that trust is the foundation of high performance. Alex Edmans, finance professor at the London School of Economics, completed a four-year study on the 100 Best Companies to Work for in America. His research revealed that high trust cultures had delivered stock returns superior to peers by 2 to 3 percent a year over a 26-year period. In addition, turnover rates were 50 percent lower than competitors, and innovation, customer and patient satisfaction, employee engagement, and organizational agility were higher. In brief, Edmans found that the greater the trust, the greater the performance.8

These findings make clear that leaders who cultivate trust will thrive despite pressure and uncertainty. If you are looking for insights on how to do this, here is a good example that will surprise you. In 2018, Lesley McKenzie was selected to coach the Japanese women’s rugby team. She had played on the Canadian 2006 and 2010 women’s rugby World Cup teams. She had coached rugby in New Zealand. So, how did a westerner earn the trust of young Japanese women to compete against teams that were often bigger and stronger? She put the interest of her players first and led from the back. She led from a position of vulnerability, and she asked questions and focused on their learning. She asked players to describe in their own words the rugby skills and teamwork they were learning. She asked players to describe how they could strengthen their performance. Most important of all, she took a personal interest in them as people.9

McKenzie’s story illustrates how leading from the rear involves vulnerability because trust comes with no guarantees. Vulnerability means that someone could get hurt here—me! Vulnerability comes with a trust tax, and like any tax, we have to pay. We don’t get to opt out of paying the trust tax. We do get to decide how much we trust others along the naïve-to-wary continuum. Sometimes we get burned for trusting when we shouldn’t. Other times, we lose opportunities when we should have trusted but didn’t.

When we make it clear that we don’t trust others, others pick up on it and don’t trust us. If we never trust anyone, then we guarantee that we never will have strong, deep, meaningful relationships. We will get stuck on our own little island of individual solitude. The trust tax is often higher for losing opportunities because we distrusted others than it would have been if we had paid the tax for getting burned. This isn’t an argument for naïveté. It is to suggest that where we come down on how much we trust others defines our relationships and our character.

What doesn’t ensure trust is a fancy job title. In fact, it is a voluntary act for each teammate to decide whether they trust a leader. The only outcome that the leader controls is whether they are trustworthy. In other words, trust is a by-product of being trustworthy. Trustworthiness depends on past experience with the person or organization. Trust can be limited to a formal agreement or contract. Trust can be based on giving someone a chance and then waiting to see what that person does with that chance. When trust is high, we are more understanding about mistakes. Unconditional trust happens when people rely on each other’s word without question. Restoring trust is especially impressive since it depends on forgiveness, righting our wrongs, and putting aside our pride.

Lastly, what we place our trust in or how we perceive the world is a more powerful predictor of performance and life satisfaction than our circumstances. We only derive 10 percent of our happiness from our circumstances. So, the world we create is disappointing when we trust that happiness is “out there” in external events but just beyond our reach. This means that the odds are low that receiving a raise or buying a new car or home will bring enduring happiness. A better bet is trusting in how we develop our character. As our character develops, we will see the world in a new way. The important point is this: how we perceive the world is more important than what happens to us.

There are five enduring elements to creating a world in which we want to live:

1. Trust in practicing virtues and relying on our strengths

2. Trust in gratitude for what we have rather than focusing on what we don’t have

3. Trust in reflection by slowing down and paying attention to our life

4. Trust in being engaged by enjoying the process of getting better

5. Trust in creating a meaningful life, which almost always means serving others10

COMPASSION: SERVICE BEFORE SELF

Cure sometimes, treat often, comfort always.11

—HIPPOCRATES

Again, we all operate along a compassionate-indifferent continuum. When we do practice compassion, we are more likely to have good health, better employment options, and stronger families. This is why it is in our self-interest to be compassionate since altruistic people receive more favors from others. When you give often, you receive often.

But don’t just take our word for it. Research in neuroscience has proven that compassion has benefits. When we give, the area of our brain associated with positive feelings activates, lighting up on an MRI scan. Acts of compassion encourage a more positive perspective, reduce stress, and increase satisfaction. When we’re out to get one another, our stress soars and relationships cannot flourish. When we look out for each other, the stress of extreme competitiveness dissolves, and we can better work together.

In Greek, love or passion is eros, which means energy, drive, and all that gets us moving forward. Compassion means that I have eros—energy and concern—for someone else. In brief, I care.

A leadership team at a factory in Tijuana, Mexico, asked employees what could be done to improve their lives. The workers’ surprising request was not that the leaders focus on them but rather, that they help their neighbors who were living in dire poverty. The factory workers, who were paid well and lived middle-class lives, daily drove past poverty-stricken neighborhoods, and they wanted to improve their neighbors’ quality of life. As a result, engineers started tutoring students in math and teaching school administrators about sustainability practices that saved the school money. Teammates purchased supplies for teachers and students.

It is a nice warm and fuzzy story, but what does it have to do with business? The Tijuana facility is part of Parker Hannifin, and this location was listed among the best places to work in all of Mexico. At the time of this compassionate community outreach, the Tijuana location had among the highest engagement scores and financial results in a company with operations in 50 countries. While increased profitability cannot be absolutely attributed to practicing virtue, there is a statistically significant (p < 0.05) relationship between virtue and engagement. A virtuous culture alone won’t succeed when leaders are unable to craft and execute a competitive strategy. That said, strategy without virtue fails when leaders try to execute competitive advantages inside a dysfunctional culture.12

Compassion might seem like a loaded word, but Bishop Desmond Tutu argued that in order to be compassionate, you simply must act. This is exactly what medical students in Cleveland and, separately, in Minneapolis did during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. They developed a Google Docs signup sheet to volunteer for tasks that would help interns, residents, and fellows who were on the front line of COVID-19 care. Students signed up for grocery shopping, childcare, and organizing teaching syllabi as their institutions prepared to take on the surge.

Highly engaged teams are led by compassionate leaders—people who think less about themselves and more about others.

This theme was present in Parker’s Tijuana story and the medical student story. Highly engaged teams are led by people who advocate for the teams’ development and success. Highly engaged teams are led by people who reframe their jobs to foster engagement, satisfaction, and resilience. This is the kind of leadership that helps teammates feel like they belong, matter, and can make a difference. Those feelings increase commitment to the leader, to the team, and to the organization, and they help drive high performance.

COURAGE: DO THE HARD RIGHT RATHER THAN THE EASY WRONG

Success is not final; failure is not fatal. It is the courage to continue that counts.13

—WINSTON CHURCHILL

Like all the virtues, courage is not some absolute characteristic that either we have or we don’t. We are human, so achieving virtue waxes and wanes, ebbs and flows. Indeed, our pursuit of virtue is iterative, borrowing from the Latin word for journey: iter. Sometimes, we are closer to achieving virtue by pushing through our fear to do what we know is right. Or, at the other end of the continuum, we don’t admit or address our shortcomings.

Virtues must meet two conditions. They must be acted upon, and they must aim at the good. So, while skydiving might be gutsy, dangerous, and an exhilarating action to take, minus a moral quality, it is not courageous. In addition to confusing danger with virtue, we can limit our view of courage to heroism. We are impressed with the courage of a hero such as Mother Teresa or Abraham Lincoln. Heroes inspire, but a big remarkable life that lives beyond time and crosses national borders is out of reach for us mere mortals. Courage does not have to be a life-threatening or heroic act. Rather than limit our notion of courage to extraordinary acts of bravery in the face of danger, we can expand our understanding of courage to something that fits all of us—for example, to resolve a conflict effectively or take an intelligent risk.

Courage could stand at the headwaters of all the virtues. Courage is rooted in the French coeur, which means “heart.” To have courage means taking heart and jumping in. Often it means to try something that we are not sure we can do. Courage usually feels risky.

There is a perfectly good neurological explanation for why we invest more in fear than hope: our primitive brain. Early humans were constantly threatened by wild animals or other tribes. Our primitive brain is an automatic response to physical danger that allows us to react quickly without thinking to avoid being skinned alive. The primitive brain is also known by its less interesting neurological term: the amygdala. This is the part of the brain that processes strong emotions like fear.

The trouble is that our primitive brain does a lousy job distinguishing between a meeting when our ego took a beating in front of our peers and real life-and-death situations. Hurt feelings generate the same emotion as physical danger, even though the threat is very different. An activated amygdala can lead to loads of regret—such as the time in a public meeting when we said our boss was a moron. When the amygdala disables our ability to reason, irrational over-reaction follows.

Two hormones give an activated amygdala its power: cortisol and adrenaline. These powerful hormones do things that you may not notice:

![]() Relax your airways to take in more oxygen

Relax your airways to take in more oxygen

![]() Increase blood flow to your muscles to increase speed and strength

Increase blood flow to your muscles to increase speed and strength

![]() Increase blood sugar for more energy

Increase blood sugar for more energy

![]() Dilate pupils to improve vision

Dilate pupils to improve vision

The executive function of the brain can override the amygdala when a threat is moderate, but when a threat is strong, the amygdala can hijack our brain and overpower our executive functions. While you cannot eliminate an activated amygdala, you can learn to manage it by kicking your prefrontal cortex into overdrive. We will return to exploring this neurological backdrop throughout the book.

Here is the important insight about courage. It does not involve the absence of fear. Courage is pushing through our fears to do the hard right rather than the easy wrong. This is why courage is a fundamental measure of character. To act with courage means that we have chosen a greater benefit than individual comfort and achievement. Courage also means doing what is right even when pressured by others to do the wrong thing. Courage can involve overcoming self-pity or feelings of having been victimized. Courage is needed to overcome our shortcomings. All of these qualities of courage are why all cultures lift up courage as noble. Can you imagine a culture idolizing cowardice?

Let’s turn to a story from medicine to illustrate courage as virtue. A three-year-old with a low platelet count and risk of bleeding was admitted to a children’s hospital. The child was fussing and complaining of a headache. The doctor provided a cursory exam and reassured the mother, Mrs. Tom, that everything was all right. No tests were ordered or performed. Less than an hour later, the child had a seizure and developed a fatal brain herniation, the obvious result of bleeding in the brain.

The quality officer of the children’s hospital, Dr. Ireland, was on call that night, and she became aware of the tragic events. Dr. Ireland visited the weeping mother, and she explained that by failing to order a CT scan of the head, the hospital had made an egregious mistake. Though Dr. Ireland was not involved in the child’s care, she owned the error, and she explained to Mrs. Tom what could have been done that might have saved her child. Dr. Ireland courageously risked the wrath of a parent who had just experienced the inconsolable loss of a child. She risked feeding a lawsuit. She risked making an unpopular decision that could have negatively affected relationships with her colleagues.

Three months later, the hospital asked the mother if she would help prevent similar occurrences and invited her to make a videotape about what had happened. Mrs. Tom could have been enraged and refused the invitation. Instead, she made an impassioned video about speaking up and working with caregivers, so that this would never happen to another child. The video was posted on the hospital’s website, and it has been viewed by hundreds of thousands of people. As an aside, no lawsuit was filed. One way to learn from Dr. Ireland’s courage is to ask the question:

“What would I do if I weren’t afraid?”

We conclude this section on courage with a word that is not often considered related to courage: vulnerability. Consider for a moment whether you have observed an act of courage that didn’t involve vulnerability. Once we understand that courage is about taking prudent and intelligent risks, it makes sense that vulnerability is a part of that. The word vulnerable comes from the Latin vulnerabilis, meaning “to wound.” Vulnerability means that we might get hurt. Cowardice, on the other hand, means “to cover up,” or “to turn” or “back away.” Vulnerability equals risk, uncertainty, and exposure. That is why vulnerability is not an act of weakness; rather, it is an act of strength.

Vulnerability is especially important when it comes to innovation. In fact, creativity is an act of courage precisely because we must put our neck out to try something new. It isn’t exactly life-threatening to have our ideas or work rejected. Yet, brain scans show that experiencing rejection activates the same regions of the brain associated with physical pain.

How can you innovate without fear? You can’t. Innovators who persevere understand that success often follows in the wake of painful mistakes.

When we fear failure more than we desire innovation, we play it safe—and thus the boldest and best ideas may never surface. Our fear of failure is outweighed by our distaste for not trying. Credit goes to those who are inside the arena trying, even if they fail. Ernest Hemingway put it this way: “Courage is grace under pressure.”14 Pressure is almost always found at the junction requiring courage. When life is easy and decisions are no-brainers, courage is not needed. Where there is pressure, we must take heart because the next virtue, justice, is often a real challenge.

JUSTICE: LIVE BY CONVICTION, NOT CIRCUMSTANCE

If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.15

—DESMOND TUTU

What if we inspired trust by operating a marketplace based on a commitment to virtue rather than rules, while recognizing that the rule of law can’t be ignored?

One of the main goals of justice is to treat everyone with respect, regardless of how they treat us. This is far from easy, requiring strength and practice. Character can seem quaint when we are threatened or disrespected. Indignation and rage can easily take over. Bloated egos cause us to take things personally. And when things get personal, our judgment gets fuzzy. Slaying our ego is difficult to do, but it is essential if we hope to treat others—all others—with respect and dignity. Doing so is just.

Justice involves the rule of law and virtue embodied in the iconic figure Lady Justice. She stands as a moral force in our judicial system. She instills trust by relying on a blindfold, a balance, her foot, and a sword. The blindfold signifies impartiality, and the balance weighs evidence objectively. Her right foot holds down a snake, embodying triumph over corruption, bias, and intimidation.

The sword is doubled-edged, suggesting reason can be used for good and ill. One edge of the sword makes clear that no one is above the law. If we were all angels, we wouldn’t need rules. This is why rules have a place in society. In fact, the rule of law is the foundation of a civilized society. Compliance can be an effective way to enforce rules when our goal is to restrict choices and decisions related to medical records, money management, or driving practices that put truckers, as well as the drivers around them, in danger.

The other edge cautions against swinging the sword of compliance too broadly. Doing so can discourage what we want to encourage—moral will and skill. When rules are excessive, filling out paperwork comes at the expense of teaching students, caring for patients, and coaching teammates. When rules are excessive, creativity and innovation are reduced because by its very nature, innovation requires that rules are loose, not tight. Rules are often designed for a stable world. But much of our world today is dynamic and changing.

In 1996, Marines Jack Hoban and Robert Humphrey formed the Ethical Protectors program to teach Marines to use their powers to protect people by deescalating rather than escalating a conflict. This program combines the martial arts with character training to teach both Marines and police officers what it means to be an “ethical protector”—that is, a person who protects life, self, and others, all others, including the enemy.

Hoban started with the Marines’ core values of honor, courage, and commitment. While these values are noble in purpose, without care, honor can become conceit, courage can become martyrdom, and commitment can become zealotry. The difference between Marines and the enemy, then, is a universal commitment to protect life. This protection extends to the enemy (all others) as long as they have stopped taking life.

Hoban’s first hurdle was to redefine a warrior as a person who kills only to protect others. The second hurdle was to demonstrate that protectors are far more ferocious than killers. A mother lion protecting a warthog dinner from a pack of hyenas will fight up to a point. However, a mother lion protecting her cubs will fight to the death. The third hurdle was to stop the practice of dehumanizing the enemy by calling them “trash” or using racial slurs. Hoban wanted to be clear that killing people just because they disagree with our beliefs is indefensible.

Some Marines struggled to accept Hoban’s thinking. They reminded him that they were facing a ruthless enemy that terrorized civilians and beheaded soldiers. Being soft against a callous adversary would get innocent people killed. In response, Hoban argued that treating people with respect and dignity is not going to make a Marine less capable of doing what needs to be done.

Everyone deserves to be treated with respect and dignity, even the enemy. This is justice embodied. Law follows society’s vision of justice, not the other way around. This means that we decide what is just and then pass a law. However, what is legal and what is ethical can be quite different. The rule of law ensures that contracts are binding, ensuring supposedly just business practices. But those same laws have allowed executives to walk away with millions, even when customers were deceived, wealth was destroyed, and employees lost jobs. So, the distinction between law as rule and ethics as an exception to the rule is important to understand. Law is what we have to do. Ethics is what we should do.

The University of California at Berkeley Psychology Department used cookies to distinguish between what leaders have to do and should do. Students were organized into teams of three, one team member randomly selected to lead the group. The team was then asked to brainstorm solutions to problems, such as cheating and binge drinking. After 30 minutes, researchers brought each team a plate of four cookies, one more than the number of team members. In each case, the randomly selected leader quickly ate the fourth cookie and without any discussion. The leader was neither more virtuous nor more valuable to the team. The person simply believed that rank had its privileges.

Author and former investment banker Michael Lewis thought that this simple experiment captured what he observed on Wall Street. Leaders who were lucky to receive extra cookies believed that they deserved them, grabbing excessive compensation and leaving crumbs for shareholders, employees, and taxpayers. Lewis concluded that their morality was corrupted by the power of their position.

Let’s consider one more point that implicates all human beings, namely, how we sometimes react when we are treated unjustly. There is an alternative to being ticked off. Epictetus notes, “If you do not wish to be prone to anger, do not feed the habit; give it nothing which may tend to its increase.”16 We know that people who learn to grow from injustice have less stress, less depression, better health, and better relationships with others. This is because exercising forgiveness helps them to repair their relationships—especially if the offender has also apologized and tried to make amends. Research shows that forgiveness helps coworkers rebuild positive relationships following conflict. Forgiveness reduces the desire for revenge, which is a major cause of negative behaviors in the workplace.

If we are not careful, power can replace compassion with inattention to the concerns of others and in the process, undermine justice. This is why we immediately follow justice with a look at wisdom. And when it comes to wisdom, we give the last word on justice to Mahatma Gandhi: “The weak can never forgive. Forgiveness is the attribute of the strong.”17

WISDOM: STRIVE TO UNDERSTAND RATHER THAN TO BE UNDERSTOOD

The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control. Where then do I look for good and evil? Not to uncontrollable externals, but within myself to the choices that are my own.18

—EPICTETUS

Edie, the remarkable holocaust survivor described in Chapter 1, has achieved hard-won wisdom. For example, she greets people by telling them she misses them and how good it is to see them rather than asking them how their day was. She suggested that we not fight with someone who disagrees with us. Instead ask, “How can I be useful to you? Let me know if you are interested in my perspective.”

The kind of wisdom that Edie embodies is sorely lacking despite living in a world that can access so much knowledge so easily. The mere tap of a phone or computer keyboard gives us more knowledge than we can ever consume. Yet, knowledge alone does not teach us to act wisely by doing the right thing, in the right way, for the right reasons.

Being wise allows us to navigate complicated workplaces and situations. Being wise includes knowledge, but it is more than that. Wisdom adds the dimension of practical skill to knowledge and information. Wise people like Edie become more pragmatic rather than idealistic or self-righteous. With wisdom, we clarify who we want to be, train our emotions, and engage in a journey of self-cultivation.

Like all virtues, wisdom is learned. First, we make our habits, then our habits make us. By training our emotions and focusing on habits and behavior, we can make a lasting change. Wisdom is not a matter of high IQ or formal education. Sometimes, in fact, people with common sense lack a formal education, while well-educated people may have little or no common sense. Because wisdom requires experience, age is often associated with being wise. As people age and realize that they are vulnerable and that life can be swept away in a heartbeat, they are better able to see what is important and what is not.

However, young people can acquire a wise perspective too. Those exposed to life-altering events, such as the terrorist attacks on September 11 in the United States or the SARS outbreak in Asia, demonstrated a similar reordering of priorities as older folks. Living through a serious illness or crisis puts life into focus, revealing new insights.

Wisdom is critical to effective leaders. A wise leader listens, is not defensive, and is quick to recognize the contribution of others. A wise leader seeks mentors and mentors others. When it comes to increasing engagement, wise leaders are well aware that money alone isn’t the only way to go. A good, competitive wage matters, but money is not sufficient to cultivate a passionate staff. Wise leaders start with the fully engaged people to understand what is going well and then figure out ways to do more of that with others. Wisdom starts with what is right, rather than what is wrong.

We are constantly changing as we reach different phases of life. The issue isn’t whether we can change, but rather how we will change. Character is learned, practiced, and cultivated. Virtue is developed best when we feel responsible for our own growth. We are more motivated and perform best when we leverage our strengths and manage our weaknesses. This is wisdom—realizing that there is always room for growth.

Wisdom is a means rather than an end. Wise people like Edie cultivate inner strength through disciplined reflection. The reflection that we can’t see cultivates acts of compassion and justice that we can see. Growing in wisdom is a wonderful way to get better. And when we get better at who we are (for example, we practice wisdom), we get better at what we do.

TEMPERANCE: CALM IS CONTAGIOUS

Calm is contagious.19

—ROARK DENVER, RETIRED NAVY SEAL

In a chaotic environment, the role of the leader is to lower anxiety. “Calm is contagious” is something you have to train for. Under pressure, people default to their training. Training alters our default setting. NASA trains its astronauts so thoroughly that what is learned becomes a default habit. Even the bravest of astronauts become terrorized when completing a spacewalk. Astronauts have reported that a spacewalk gives the sensation of experiencing a crushing free fall tumbling back to earth. Training does not eliminate this fear, but it can teach astronauts to cope. Habitual change is achieved by practicing until the trainees no longer need to think about the new habit. Under pressure, they will remain calm and default to the standard of their training.

Let’s apply to ethics the idea that under pressure, we default to our training. Compliance training presents ethics as “What should we do?” and “Why should we do it?” The harder question is this: “What does it take to make us virtuous, given all the distractions, temptations, and complexities that lie in our wake?” If ethics were as simple as compliance training suggests, then acting with justice and compassion would be easy. But it isn’t. Ethics is not simply knowledge. It is how we act, especially under pressure.

The compliance model of ethics is limited because it overlooks the fact that when rules collide with habits, habits win in a knockout. To overcome our habits, we have to practice. Just as bridge builders improve by building more bridges and surgeons provide higher surgical quality and better outcomes by performing more surgeries, we become more just by doing just acts.

When threats, either real or perceived, are triggered, the amygdala can shut down the thinking brain. When the brain is focusing on the threat, it’s difficult to change. After the amygdala is activated, it takes about 20 minutes for the thinking part of the brain to kick in. One simple technique to reset the brain is to pause and plan. This means that when adrenaline starts to flow, you take deep breaths for 60 seconds. Sit up straight in your chair, close your eyes, and rest your hands in your lap. As you calm your brain, you can think more clearly; make better, more rational decisions; and act with more self-control.

When it comes to work, people juggle multiple tasks at once, trying to get more done in less and less time. According to Clifford Nass, psychology professor at Stanford University, nonstop multitasking actually wastes more time than it saves. Multitaskers experience a 40 percent drop in productivity, take 50 percent longer to complete a single task, and have a 50 percent higher error rate.

To get the best out of technology, we have to practice temperance. This is why some organizations ban emails on the weekends. When it comes to resolving conflict or issues that are complex, technology is the wrong tool for the task at hand. Instead, consider this hierarchy:

1. Whenever possible, talk face-to-face.

2. If face-to-face or Zoom isn’t possible, then talk by phone.

3. When a phone call isn’t possible, text requesting time to talk face-to-face. A limited number of characters forces you to get straight to the point. Relationships are improved when we develop a habit to talk or phone first, and text and email last for issues that involve conflict or are complex.

We can practice temperance by making a concentrated effort to create new habits (see Chapter 13). We have to practice deliberately, devoting our full concentration and effort toward our goals. Learning to change our habits isn’t easy though. Habitual change takes time and effort. To practice temperance, start with a compelling purpose governed by intrinsic, rather than extrinsic, motivation. Next, seek feedback from a trusted source and reflect often.

Our knowledge will not save us from ourselves. Like eating right, exercising regularly, and getting adequate sleep, temperance is less what we know and more how we live.

HOPE: BETTER, NOT BITTER

We must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.20

—MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR.

You don’t need to be a famous athlete, astronaut, or national leader like Martin Luther King, Jr., to make a difference. Interestingly, one way to make a difference is to focus on how we are the same. The virtues give us hope by focusing on what we share in common, rather than what divides us. As Maya Angelou wrote, “I note the obvious differences between each sort and type, but we are more alike, my friends, than we are unalike.”21

Having hope means viewing an adverse experience as an opportunity for growth. You can become better, not bitter, by letting go of a victim mentality and instead choosing to view yourself as a survivor.

In 1945, Rita (not her real name) was born to a Black father and a white mother in Cape Town, South Africa. Her story is about someone who replaced victimhood with growth. District 6, the neighborhood she lived in, was a multiracial, multireligious community. That is, it was until 1966, when the apartheid government, whose goal was to separate and segregate its citizens by race, declared the neighborhood white and then proceeded to bulldoze the homes of more than 60,000 residents.

Rita’s father died in the early 1960s, a death that was ultimately a blessing to a family living in the cruel world of apartheid. A mixed-race marriage violated apartheid immorality laws, and her family would have been forcibly separated had he lived. During the campaign to bulldoze District 6, Rita’s mother stood strong against those who would force her from her home. But in 1981, Rita’s mother was told the house would be bulldozed, whether or not she was inside. The very day after she moved, Rita’s mother died, another casualty to apartheid.

After all that she had suffered under the apartheid regime, losing both of her parents and her home, Rita was consumed by a hate so strong that she wanted to strangle her oppressors. Over the span of decades, Rita learned to let go of the hatred that gripped her. As she learned to forgive, Rita felt the dark emotional burden lift. It took years, but Rita put herself on the path to becoming better, not bitter, transforming all she had experienced into an opportunity to grow. One way to understand how Rita managed this is to understand that in spite of it all, she was realistically optimistic. Her form of optimism wasn’t Disneyland.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Martin Seligman wanted to find out whether optimism and pessimism are genetic traits. In his research, Seligman found that people who had learned to be helpless viewed negative events as personal, permanent, and pervasive. They held these views even against evidence to the contrary. If they flunked a math test, they told themselves they had never been good at math and never would be and that this was the kind of failure that always happened to them. A single, negative experience became a general negative viewpoint that led to pervasive helplessness.

While the pessimist views failure as permanent, the optimist sees events as impersonal, temporary, and challenging. For example, optimists who have not been able to grow an organization are deeply disappointed, but they learn from mistakes, so they can improve performance next year. They understand that past failure does not preclude future success and that economic downturns happen to every-one. The good news is that realistic optimism can be learned, just as helplessness is learned. Thoughts are malleable, which means that hope can be taught, especially realistic optimism that involves boundaries and agency. Boundary conditions include events that we cannot change, such as economic downturns, global pandemics, and political polarization. Within the boundary conditions rests optimism. We have agency to respond to situations in our control, or at least we can control how we choose to respond to circumstances beyond our control.

In addition to realistic optimism, we can also learn to be grateful. We know from research that gratitude is a key ingredient in the virtue of hope. The root word of gratitude is grace, or a gift that we didn’t necessarily earn. We can learn to appreciate people and experiences that make our life better and worthwhile. Gratitude involves humility. So, it is at odds with the idea of building a “personal brand,” which is often touted as the basis for a successful life, and that makes practicing gratitude challenging. By practicing gratitude, you can learn to be humble rather than prideful. You can avoid the arrogance that can be so damaging to team relationships as well as homelife. Gratitude isn’t a weak word. Research makes clear that gratitude is a muscular word. Research finds that practicing gratitude improves health, increases energy levels, and encourages optimism and empathy.

Hope is animated by courage and acknowledges that possible solutions exist. William Lynch, a New York Times reporter who became a priest, wrote how hope and courage are linked by “the fundamental knowledge and feeling that there is a way out of difficulty, that things can work out, that we as humans can somehow handle and manage internal and external reality, that there are ‘solutions.’”22

Few people have lived by this statement more than Viktor Frankl, the Nazi death camp survivor mentioned in the previous chapter. In his book Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl described the horrific treatment of prisoners. Faced with humiliation, torture, and death, many prisoners became selfish and self-serving, but a small number of prisoners gave up food and blankets to those in need, even as they themselves suffered. Frankl wondered at the difference between the prisoners who gave and those who took. He concluded that neither wealth nor status, education nor any one religious tradition made the difference. The commonality among those who sacrificed was that they had a deep sense of purpose. They believed that even when they couldn’t control their circumstances, they could always control their response. Knowing their fate might be sealed, these prisoners accepted their reality with integrity. Paradoxically, these were the individuals most likely to survive the death camps. According to Frankl, hope is a decision, a response to a choice, as is despair. Frankl asserted that the most powerful motivator sought by humans is meaning:

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.23