ENGAGEMENT

To win in the marketplace, you must first win in the workplace.1

—DOUG CONANT, FORMER CEO OF CAMPBELL’S SOUP

In March 2020, at the very beginning of the global pandemic, models developed by staff at the Cleveland Clinic estimated that 8,000 patients would be hospitalized with COVID-19, necessitating 1,700 ventilators. This number did not include serious non-COVID-19 illnesses such as heart attacks and strokes. Disaster planning based on this worst-case scenario identified that these issues needed to be resolved by May 2020.

To be able to accommodate the surge of COVID-19 patients, elective surgeries were canceled and outpatient visits fell as patients wrongly thought that hospitals were unsafe. Though many hospitals instituted layoffs and issued furloughs in an attempt to survive, Cleveland Clinic CEO Dr. Tom Mihaljevic took a different tack. Despite the financial pressures facing the Cleveland Clinic, like every hospital in the United States, he announced at the outset of the pandemic that clinic caregivers would go through this as a team—there would be no layoffs and no furloughs.

The result? Employee engagement scores from items such as “I would recommend the Cleveland Clinic as a good place to work” and “Executive leadership provides open and honest communication” soared from already high baseline values established in 2017. Although a global pandemic robs us of our control over much in our lives, it does not control how we treat each other.

The Clinic promised their staff that they would keep their jobs, jobs that were about to become very physically and emotionally challenging, with the possibility of exposure to a deadly virus with no pay raise. And yet, engagement went up. Why?

BELONG, MATTER, AND MAKE A DIFFERENCE

The leaders who have developed their noncognitive abilities are successful in making people feel like they belong, matter, and make a difference. As a by-product, engagement goes up. This point is not widely understood. And, based on Gallup’s reporting that 70 percent of employees are not fully engaged, these insights are not widely practiced. Whether times are calm or chaotic, and despite countless leaders of good faith investing millions to boost sagging morale, the engagement needle is consistently stuck at 70 percent disengaged. If company picnics, casual dress, Ping-Pong, more volunteering, and clear career paths did the job, engagement would be easy and soaring. While these might all be good things to do, they are all unlikely to budge engagement.

How about pay? Researchers like Edward Deci synthesized results from 128 controlled experiments that showed that pay incentives had a consistent negative effect on intrinsic motivation. These effects were especially strong when the tasks were interesting or enjoyable rather than boring or meaningless. Deci’s conclusion was that extrinsic rewards run the risk of restraining, rather than enhancing, intrinsic motivation.2 Another meta-analysis of 92 quantitative studies that included over 15,000 individuals showed that the correlation between pay and job satisfaction was very weak. Furthermore, job satisfaction is not related to nationality or whether a person holds an entry-level, middle management, or senior-level position.3

Just so there is no misunderstanding about compensation, let’s be clear that job satisfaction doesn’t pay the mortgage. People must be paid a living wage or better yet, offered bonus pay when the organization does well financially. Just understand that the relationship between pay and performance is like a sugar high that fades quickly. Over the long term, money can be more a source of dissatisfaction than satisfaction. If engagement could be bought, plenty of financially secure organizations would have solved this problem long ago. The biggest cause of disengagement is underinvestment in leadership—something to which we will return.

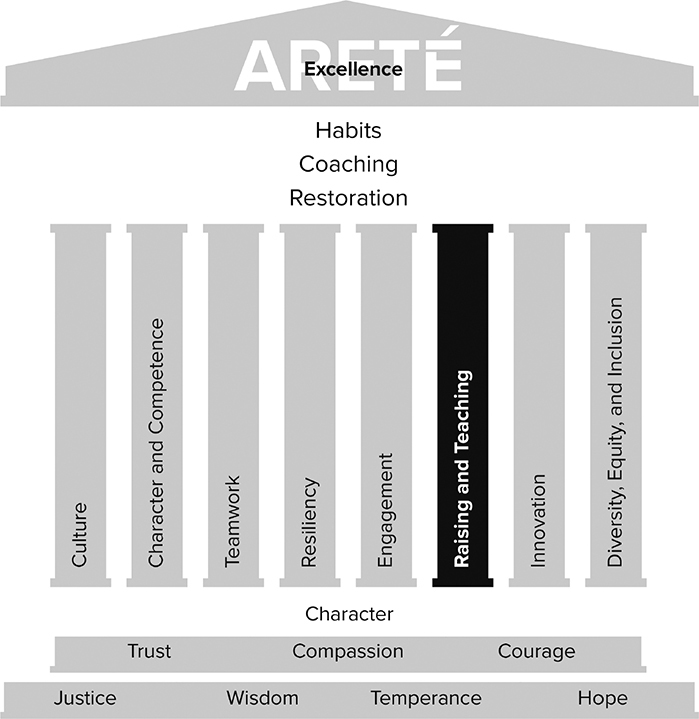

The evidence is in. Most approaches currently used to increase engagement simply don’t work. The main point of this chapter is that engagement is largely an intrinsic issue that cannot be solved with extrinsic tools, such as pay. Engagement is affected by three drivers (the 3Rs we discussed in Chapter 6, as they are also the cornerstones of resilience):

1. Do I feel like I belong?

![]() I feel included and supported.

I feel included and supported.

2. Do I feel like I matter?

![]() I understand why my role matters to my organization and my strengths are leveraged.

I understand why my role matters to my organization and my strengths are leveraged.

3. Do I feel like I make a difference?

![]() I feel valued and I add value.

I feel valued and I add value.

We need to feel appreciated to contribute. Appreciation without contribution is narcissism. Contribution without appreciation is discouraging. To matter is to contribute to the organization in a way that leverages my strengths. To make a difference is about doing meaningful work and contributing to helping other people create meaningful work.

The “eureka moment” is to understand that engagement or morale is actually a moral issue. This point becomes clear once we understand that moral is the root word of morale. How people treat each other is core to morality. Compassion is an especially important engagement ingredient. For example, Gallup research has repeatedly demonstrated a clear link between having a best friend at work and engagement.4 If engagement is really low, there is good reason to suspect the absence of compassion.5

A strong moral culture deepens the bonds between us, so people feel connected. In contrast, an amoral or toxic culture is characterized by teammates feeling disconnected, resulting in poor performance or worse—teammates actively working against the goals of the enterprise.

At Parker Hannifin, virtue has been practiced both because it is worthy in and of itself and because it affects engagement. Over a 12-month period, when leaders and teams consciously practiced virtue, engagement scores consistently increased between 10 and 20 percent. Should this come as a surprise? Well, let’s invert the case for virtue. If virtue doesn’t affect engagement, then what does? We know that carrots and sticks—reward for doing good work and punishment for not—don’t increase engagement. Would we bet that distrust, callousness, cowardice, and despair would favorably affect engagement over trust, compassion, courage, and hope?

The hopeful outcome is that we don’t have to practice virtue perfectly. But we do need to try. The moral life defined by virtue isn’t about a purity code. In fact, practicing virtue involves setbacks, tensions, and misunderstandings. However, when we get it right—or even try—we continually exercise our altruistic muscles and, accordingly, deepen trust that results in the higher levels of engagement that all leaders seek.

WHAT IS ENGAGEMENT?

If you ask your teammates what engagement is, answers will likely range from blank stares to work ethic to motivation and more. While everyone is for engagement, we often don’t know what it is. Organizations can’t affect something that is ill defined. Truth be told, there isn’t a single definition of engagement. However, defining engagement as giving “discretionary effort” gets us off to a good start. People who exhibit discretionary effort act like owners rather than employees. They are committed to the organization’s success.

People who demonstrate discretionary effort work with others to create solutions to make things better. They do the right thing and fix problems, even when no one is looking. Discretionary effort happens best when people trust and care about their teammates, when leaders leverage teammates’ strengths, and when people find purpose in their work.

Why Is Engagement Important?

One way to answer this question is 70 percent × 4:

1. 70 percent or more of a typical workforce is disengaged.6

2. 70 percent of the variance in return on investment is attributed to the leader and the team, not the strategy.7

3. 70 percent of teammates report to a frontline leader.

4. 70 percent of the variance in engagement scores is attributed to the direct leader.8

Point 1

Let’s start with 70 percent disengagement levels. Gallup’s research shows that the distribution of engagement is about 30/50/20. This means that about 30 percent of a typical organization is fully engaged—loads of discretionary effort. About 50 percent will do what you ask, but not much more—limited, if any, discretionary effort. Sadly, about 20 percent are disengaged, with some percent of those actively working against the goals of the enterprise. Worse still, the 30/50/20 engagement distribution has been largely static for years. The key insight of this distribution isn’t to disparage the disengaged. At some point in your career, have you been disengaged? Are there times when you mailed in your effort? The best engagement cure for all of us is to feel like we belong, matter, and make a difference.

Point 2

About 70 percent of the variance in return on investment is attributed to the leader and the team, not the strategy, according to MIT. An organization’s strategy will and should change. A great leader and/or team will fix a bad strategy. A middling leader and/or team combination will mess up even a brilliant strategy. The implication is clear. Ultimately, return on investment is a bet on the leader and the team more than on the strategy.

Point 3

About 70 percent of teammates report to a frontline leader, not to senior leaders. These leaders go to work every day wanting to do a good job. They are frustrated by working with disengaged teammates. Disengaged teammates spin (waste effort and talent on tasks that don’t matter); settle (lack commitment though not dissatisfied enough to leave); and split (they quit).9 Disengaged teammates view their jobs as an exchange of time for a paycheck. They arrive and leave on time, take their breaks, and offer minimal effort. The actively disengaged teammates are the most destructive. They undermine their teammates’ performance by sharing their unhappiness in words, attitudes, and actions.

Point 4

About 70 percent of the variance in engagement scores is attributed to the direct leader. The business literature is chock-full of advice on how leaders can motivate teammates. Yet, the reality is that organizations don’t have to motivate their teammates. They have to stop demotivating them! Leaders inadvertently make it difficult for teammates to do their jobs. Endless paperwork, micromanagement, fuzzy strategy, and most important, lack of trust and care—all contribute to frustrated teammates. People don’t leave organizations. They leave their leaders.

To be clear, a 70 percent disengagement level is not an indictment of leaders. It is an indictment of putting leaders into their positions without educating them on what engagement is, why it is important, and how it can be strengthened. One study showed that 58 percent of leaders received no training at all, never mind insights about engagement.10 As a result, few leaders are aware of the 40/20/1 disengagement distribution. This 40/20/1 calculus means that leaders achieve the highest level of disengagement (40 percent) by simply doing nothing! Apathy is a killer for engagement. When leaders focus on teammates’ weaknesses, then 20 percent are disengaged, so criticism beats apathy. However, when leaders focus on teammates’ strengths, only 1 percent are disengaged. Now that’s good math.11 This observation suggests that we should look for strengths and teach leaders to do so.

An effective engagement strategy is focused on leadership development, the cost of which is well worth the investment. Study after study has found a strong correlation between engagement and organizational performance, such as increased profitability, customer satisfaction, and growth, and decreases in safety incidents, turnover, and absenteeism. These results are consistent across different organizations from diverse industries and regions of the world. In other words, these are human issues, not industry or nationality issues. These findings make it clear that taking care of teammates—being pro-social—is the best way to take care of organizational performance.

The punch line is this: the most powerful drivers of engagement have to do with creating a sense that we belong, a feeling that we matter, and a belief that we are making a difference. With these three ends in mind, we offer an engagement playbook.

Engagement Playbook

While surveys have their role, the goal is not to chase engagement scores. Asking someone to sit down for a cup of coffee to share their experiences and their aspirations is far more powerful for understanding an organization than reporting survey results. When we start asking people how they are doing, what is getting in their way, or how we can help them, we begin enhancing engagement. When we actively take an interest in someone, engagement scores are a happy by-product.

DO I BELONG?

A sense of belonging is a basic human need that acts as an effective buffer against economic and health uncertainty. In contrast, when people feel excluded, their ability to focus and engage declines during uncertain times.

Employees with a strong sense of belonging are over six times more likely to be engaged than those who don’t feel like they belong.12 A sense of belonging builds grit and boosts motivation to persist in the face of challenging work.13 A study of people exposed to rejection showed a drop in their ability to reason by 30 percent and a decline in their IQ by 25 percent.14

Our sense of belonging underscores our desire to be “with”—with family, friends, colleagues, and teammates. We want to belong to a community and be part of a culture that nurtures the sense of belonging among all members. We know that certain behaviors enhance our sense of belonging, community, and engagement. These behaviors are related to achieving trust, compassion, stability, and hope.

Now here’s the evidence. Between 2005 and 2008, about 10,000 followers from 16 different countries were asked to name what they wanted from their leader. The answers: trust, compassion, stability, and hope. Three of the four qualities sought by followers in their leaders are virtues. The fact that followers seek virtue and stability, rather than strategy and pay, can leave some leaders scratching their heads. As a leader, you are paid to deliver results. You might say, “Look, we don’t have time to get to know people. We have work to do. If they want a friend, they should get a dog.” Besides, leaders feel it is risky to form emotional ties with teammates who have to be held accountable. Yet, it is very unlikely that people will be engaged when no one cares about them. So, the reluctant leader who manages the downside risk of a relationship going south misses the upside of engagement going north.

Here are hard facts on trust, compassion, stability, and hope. When followers trust their leaders, 50 percent are engaged compared to 13 percent when they view their leaders as untrustworthy. When people feel either their leader or someone at work cares about them, they are more likely to be engaged with customers and more profitable to their employers. When followers believe they work for an organization with a secure financial future, they are nine times more likely to be engaged. Infusing hope was especially powerful: 69 percent of followers were engaged when their leader made them “feel enthusiastic about the future,” compared to only 1 percent of those who disagreed with that statement.15

So, what is hope? Hope isn’t wishful thinking. It is about realistic optimism fueled by courage to accept the brutal facts that confront the team. Hope is a function of a struggle to focus on resolutions within the team’s control. Without hope, uncertainty and paralysis can take the upper hand. With hope, teams come to grips with their collective fear to get out of a jam. Einstein said, “It’s not that I’m so smart. It’s just that I stay with problems longer.”16 That is hope in the face of challenge embodied.

How do we have this happen more often? Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize–winning behavioral economist, believes that the key to behavior change is understanding driving forces and restraining forces. Driving forces push us in a particular direction, and restraining forces prevent change. Kahneman says, “It turns out that the way to make things easier is almost always by controlling the individual’s environment, broadly speaking. Is there an incentive that works against change? Then let’s change the incentives. If there is social pressure, then let’s reframe the pressure.”17 Though counterintuitive, Kahneman reminds us that the key to achieving behavior change is to weaken what restrains us

Despite this insight, we tend to do the opposite. We often start with the question, “How do I get this person to do something?” The driving force toolkit includes incentives and threats—sweeter carrots and sharper sticks. In contrast, a focus on eliminating restraining forces starts by asking, “Why is the person not already doing something?” Instead, we can start from the perspective of the individual and ask what restrains her. By weakening or perhaps removing restraining forces, the new behavior emerges with less tension and change is more sustainable. But when we rely on driving forces, the behavior is likely to snap back to what it was.

We start by asking questions about driving forces that push us in a particular direction, which might include these:

1. Is the pressure to achieve metrics limiting a sense of meaning?

2. How do teammates respond to pressure and time limitations?

3. Is there a practice of keeping emotional distance from teammates whom you need to hold accountable?

We ask what restrains people from feeling they belong, which might reveal forces such as these:

1. We may not be sure how to start conversations that increase a sense of belonging.

2. We may not be sure how to integrate conversations into standing meetings.

3. We may not be sure if these conversations would be viewed as cheesy and disingenuous.

We then explore ways to weaken or remove restraining forces that might yield ideas such as these:

1. Listen more, talk less. Ask more, tell less.

2. Select a learning partner to help each other listen and ask more.

3. Practice conversations that matter to contribute to a sense of belonging.

Listening is more than being quiet while others speak. Listening is about presence as much as hearing; it’s about connection more than observing. Real listening is powered by curiosity, vulnerability, and a willingness to be surprised. Deep listening leads to deep conversations. These are the kind of conversations that build trust, which is the oxygen of a healthy organizational culture. Admittedly, not everyone is necessarily curious, though curiosity can be cultivated.

For example, in medicine, caregivers learn to listen actively by paraphrasing when taking a medical history: “This is what I heard you say. Did I get that right?” The caregiver listens carefully to affirm to the patient that they and their symptoms have been understood. As much as active listening is a mainstream reflex for seasoned clinicians taking medical histories, caregivers and leaders have a long way to go to make active listening a routine part of their everyday interactions with colleagues. There is the opportunity to enhance a sense of belonging in medicine and in all organizations. We have more control over this reality than we might think. We also have more responsibility than we might realize.

DO I MATTER?

Peter Drucker said, “The task of leadership is to create an alignment of strengths in ways that make a system’s weaknesses irrelevant.”18 To this end, appreciative inquiry is an evidence-based way to leverage strengths to effect positive organizational change.

Have you ever heard of a business, university, or hospital trying to compete based on weakness? Let’s take our worst products and services and see if anyone will buy this junk! We compete based on our strengths, not on our weaknesses.

Does this mean that we ignore weaknesses? Of course not. That’s called “narcissism,” which annoys people and undermines teamwork. In fact, leveraging strengths and managing weaknesses requires that we are forthright about both our strengths and our weaknesses. So, of course, we need to deal with weaknesses. The debatable part is, how?

If we can increase the amount of time that each person uses their strengths, then performance increases. If we can offset one teammate’s weakness with another’s strength, then performance increases. If the leader integrates a strengths-based approach into the business, then performance increases. We all have to do things we don’t like or things that don’t play to our strengths. Let’s just see if we can do a better job of using our strengths more often.19

Switch from the individual to the team. A good teammate attempts to address the better part of all teammates, hopefully through subtle diplomacy, rather than heavy-handed judgment. Good teammate relationships are built on mutual forgiveness, since we inevitably annoy even people we like. All teammates are capable of saying and doing the wrong thing at the wrong time, and yet they forgive each other. Good teammates help us see ourselves through another person’s perspective and are gracious when, not if, we act like a dunce. Since teams are composed of imperfect people, without graciousness, teamwork declines. Good teammates encourage the best in each other less by judging our limitations and more by leveraging our strengths.

But strengths-spotting isn’t as easy as it seems. As deficit-based thinkers, we are more skilled at defining weaknesses than strengths. For example, organizations use green, yellow, and red colors to measure progress on their key performance indicators (KPIs). Green means goal achieved or exceeded. Yellow means caution—more work to do. Red means expectations not met. Typically, teams start with red numbers, since these areas demand attention. We ask, who is accountable and when will results be achieved? A strengths-based approach differs in two ways. First, we visibly write the virtues above the list of KPIs, including those coded as green, yellow, and red metrics. Second, we ask which virtues were present that made the green results possible. After all, can you imagine green results being achieved in the presence of distrust, cowardice, and despair? The goal is to start by defining what the team did right to achieve green results, including practicing virtue, so they can make progress on red results.

A strengths-based approach isn’t about self-esteem booster shots. Its purpose is to move an organization closer to “creating an alignment of strengths that makes a system’s weaknesses irrelevant.” The hard part is shifting from a focus on deficits to strengths. Deficit-based thinking is particularly difficult to change in work that centers on diagnosing and fixing problems, such as the work done by physicians, lawyers, car mechanics, and plumbers. Anyone whose livelihood is about diagnosing and fixing a problem is at risk for being a deficit-based thinker.

A strengths-based approach to engagement starts by making your strong stronger. Study your version of the 30 percent highly engaged, and find out what they are doing right. This doesn’t mean that you ignore your version of the most highly disengaged. Just don’t lead with your chin. Start with the people who are engaged, and apply those lessons to the disengaged. Besides, organizational success is tied directly to the retention and support of your best performers.

What doesn’t work is studying divorce to understand happy marriages. Studying low morale doesn’t teach us about cultures where people flourish. Studying disease doesn’t teach us about fitness. Referencing healthcare again, doctors especially need to work on adopting an appreciative approach to engaging teams. Why? The reason is that the entire process of figuring out what is wrong with the patient in front of you is based on a time-honored, highly effective, but deficit-based process called differential diagnosis. Patients tell us their story and their symptoms, and doctors generate a list of possible causes—the “differential diagnosis”—which informs what other questions to ask or tests to recommend in order to figure out the cause of the patients’ problem.

This is all in service of figuring out the best treatment to make the patient well because identifying the best treatment requires accurately understanding the underlying cause. As much as this process works for clinical practice, deficit-based thinking can poison the way that physicians lead. If they apply the same deficit-based thinking to their organizational lives, like figuring out how to improve quality or eliminate wrong-side surgery, the solutions are less imaginative and more limited than if they frame the question appreciatively—for example, “When we are at our best, what are we doing? And how do we do more of that?” Physicians must be mindful of which mindset they are in—clinical (where deficit-based thinking works) or organizational (where appreciative thinking is recommended)—and be able to pivot nimbly between the two in order to deploy the best listening approach.

DO I MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

For 30 years, Susan was a waitress at a university restaurant for campus leaders, faculty, and special events. She served drinks and meals, laid linen and cleaned tables, and slogged heavy piles of dishes to the dishwasher. Yet, Susan viewed her job as hospitality. The word hospitality originates from the Latin hospes, meaning “guest” or “stranger.” In Spanish, the word for “guest” is huesped. Hospes is the root of words such as hospice, hostel, hotel, and hospital. Susan embodied hospitality. She befriended faculty, their spouses, and their kids. She taught international students about American culture and helped them improve their English. She comforted homesick students, so they would stay focused on their studies. In brief, she made people feel like they belonged.

Annually, the university selected an Employee of the Year to honor at its holiday party. Usually, senior leaders and faculty were selected, but this year Susan’s name was called for recognition. About 800 people spontaneously rose to give her a standing ovation. She accepted her award with a clear statement about hospitality: “I may not be on the faculty, but that doesn’t mean I don’t know how to teach.”

There is a name and process for how Susan defined her work: job crafting. This term was an outcome of a study on hospital janitors. Interviews with janitors showed that some defined their job as a paycheck, others as a way to get ahead, and others viewed their job as caregivers. All janitors had the same job description. What differed was how they did their job. The “caregiver” janitors paid attention to patients who were upset because no one had visited, and they took time to talk and listen to them. They walked elderly patients to their cars so they wouldn’t get lost. They paid attention to those who were in a coma by moving pictures around in the room with hope that changing the environment might spark recovery. When one janitor was asked if this was part of his job, the answer was, “No, but this is a part of me.”

Finally, one more real-world example. At the Cleveland Clinic, a consistently top-rated healthcare organization, all employees of all types—doctors, nurses, health science workers, bus drivers, environmental service workers, secretaries, and others—are called “caregivers” because each has an opportunity to touch the patient in profound ways. Imagine your experience when you are confused by trying to navigate your way to your appointment in a big medical center and any one of the more than 72,000 caregivers at the clinic sees your con-fused look and stops to ask you how they can help. Imagine your experience then when they offer to guide you to your destination! When everyone is a caregiver and sees their role through a caregiver lens, the patient experience skyrockets. That is what the “hospitality” in “hospital” should do! Who wouldn’t want that patient experience?

PALEOLITHIC EMOTIONS, MEDIEVAL INSTITUTIONS, AND GODLIKE TECHNOLOGY

According to social biologist Edward O. Wilson, the real problem of humanity is the following: “We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.”20 COVID-19 laid bare the normal human folly of “Paleolithic emotions,” such as fear, greed, and hubris. Some refused to wear masks or take the vaccines despite the evidence that it protects others. Others put their lives at risk to take care of the rest of us, including the infected who didn’t wear masks.

In 2020, our “medieval institutions” were not always up to the task of fighting a pandemic that killed millions of people globally. Some institutional leaders argued for personal rights over washing hands, social distancing, and wearing masks. Other institutional leaders actively shared clinical evidence to reduce the percentage of patients who died from COVID-19. Their efforts saved lives, including the lives of those who claimed that COVID-19 was a hoax.

Our “godlike technology” produced and tested multiple vaccines with efficacy rates of about 95 percent. Miraculously, effective vaccines were created in record time—tested and ready to be distributed in less than one year. This was an unprecedented achievement in the history of developing vaccines.

We are more skilled at producing “godlike technology” than managing our “paleolithic emotions.” We are still humans seeking to cure our human failings. We can limit, but not eliminate, human folly by choosing to live our twenty-first-century life in accordance with the virtues that emerged more than 2,000 years ago.