![]()

CHAPTER 4

![]()

Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), especially those from smaller or emerging nations, can be enigmas to many fund managers. SWFs are large pools of investment capital that are owned, managed, or supervised by a state for its own interest, as well as for its citizens’ benefit. Usually, these vehicles are created to invest fiscal surpluses, excess capital from its balance of payments, proceeds from the sale of state assets, or income from commodity exports. Some participants also include state-owned pension funds, enterprises, and development banks in this category.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines sovereign wealth funds rather broadly as “pools of assets owned and managed directly or indirectly by governments to achieve national objectives.”1 The US Department of Treasury’s definition is narrower: it is “a government investment vehicle which is funded by foreign exchange assets, and which manages those assets separately from the official reserves of the monetary authorities (the Central Bank and reserve-related functions of the Finance Ministry).”2 Regardless how one defines SWFs, they are among the largest investors in alternatives and on their way to becoming the biggest (see Figures 4.1 and 4.2).

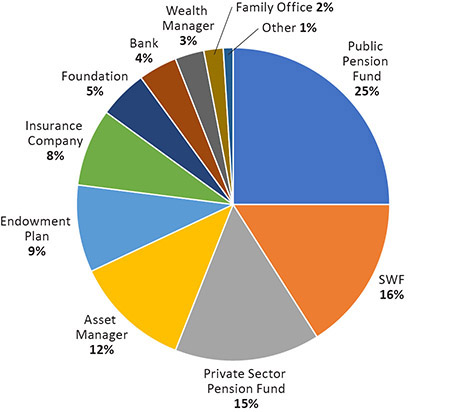

FIGURE 4.1 $1 billion club investors: capital-weighted breakdown by investor type

Source: The $1bn Club: Largest Investors in Hedge Funds, May 2015

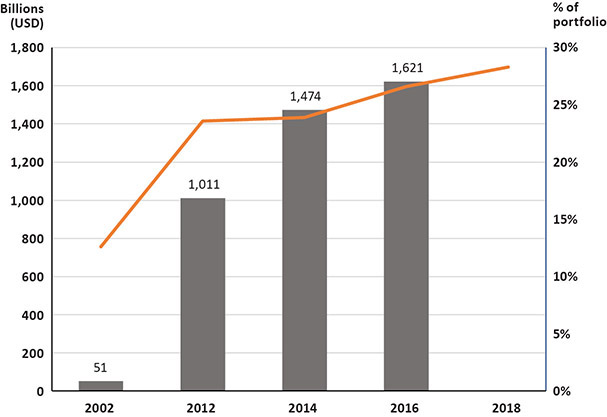

FIGURE 4.2 Allocation to alternatives by SWFs

Source: SSGA Research, using data from the Sovereign Wealth Center, and SWFC and SSGA data

Not all SWFs invest in alternatives. State-owned enterprises and state-owned development banks by their nature generally do not. We will focus on other SWF entities that do, differentiating among the various types of SWFs, their investment objectives, processes, investment considerations, the strategic roles they play nationally, and how these fit in with their investment mandates. We also will discuss the specific risks and the regulatory treatment of SWFs, including differentiating them from other government holdings such as central bank assets.

A BRIEF HISTORY

Before the formation of modern SWFs, government surpluses were exclusively invested in gold and short-term debt instruments. That changed in 1953 with the establishment of the first SWF: the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA).3 It was tasked to provide a stabilizing mechanism to cushion against the fluctuating prices of oil (a commodity whose revenues Kuwait was dependent on), invest the surplus and reduce its reliance on a finite commodity. In 1956, the Republic of Kiribati would be the second to create a SWF, for the investment of phosphate mining revenues.4

In the United States, the first SWF was established by New Mexico in 1957.5 The New Mexico State Investment Council managed the state’s permanent funds for the benefit of its citizens by maximizing distributions to the state’s operating budget while preserving the real value of the funds for future generations. The funding originally came from minerals and natural resources on public lands first granted to New Mexico upon reaching statehood. Later, funding would encompass other sources such as tax surpluses, tobacco litigation settlements, and other government revenues and wealth proceeds.

After a lull in activity for a few decades, the 1970s saw the start of a proliferation of SWFs that continues to this day. While some question the categorization of Temasek Holdings (1971) of Singapore as a SWF, other large SWFs like the Permanent Wyoming Mineral Trust Fund, Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA), Alaska Permanent Fund Corporation, Alberta Heritage Saving Trust Fund, Oman State General Reserve, and Brunei Investment Agency were all formed during the 1970s and 1980s, coinciding with a spike in energy prices. The majority of the SWFs can trace their funding to revenues from commodities.

The first non-commodity SWF was established by Singapore in 1981 with the formation of the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (now called GIC Private Limited) to manage its surplus foreign reserves with a mandate to preserve and enhance the country’s international purchasing power over the long term.6 Today, the number of non-commodity SWFs remain dwarfed by commodity SWFs; nonetheless, they still characterize most of the Asian SWFs, which are funded by national and balance-of-payment surpluses. Indeed, 5 of the top 10 SWFs globally are non-commodity.

As of 2020, 155 SWFs worldwide managed $9.1 trillion in assets, according to the “2021 Global SWF Annual Report.”7 Most SWFs are based in Asia (41.7 percent) or the Middle East (32.8 percent).8 The only major funds outside of the region are in Norway, Russia, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. The primary catalyst for SWF growth was the exponential increase of crude oil prices from $11.22 per barrel in 1998 to $140 per barrel in 20089 that created a surplus for oil-exporting nations and the need to manage that wealth. The second was the strong GDP growth among export-driven economies such as China and South Korea. One silver lining: proliferation of SWFs in the years leading up to the financial crisis in 2008–2009 enabled many countries not only to mitigate the economic impact of the Great Recession, but also deploy excess capital as “shareholders of last resort” to companies trapped in a liquidity and credit crunch.10

The sources of funding, reasons for inception, and investment objectives can vary widely. Some countries might have more than one SWF—such as Singapore’s Temasek and GIC, and Abu Dhabi’s ADIA and Mubadala. The purpose of a country having multiple SWFs is either to have a specific mandate for each entity or to encourage competition among them. Some SWFs are exclusively focused on foreign investments (KIA, Government Pension Fund Global of Norway), others are restricted to domestic investments (1Malaysia Development Berhad, FSI of Italy), or have no geographic limits (Khazanah Nasional Berhad of Malaysia).

SWF GOALS

Unlike other institutional investors, SWFs have very little in common with each other when it comes to investment and existential goals. Such heterogeneity, which sometimes can come across as incongruent within the same SWF, make this investor type among the most difficult to generalize. We recommend that marketers take a bespoke approach specifically tailored to each individual SWF. Hemali found it beneficial to utilize regional placement agents (PAs) with deep, long-term relationships to specific SWFs. Such PAs are well versed in the nuances and needs of these funds and are at times able to provide unique access that a marketer new to the region may not be able to get.

SWFs do share some common objectives. The International Monetary Fund grouped them into the following five categories based on their principal goals:11

1. Stabilization funds

Purpose: To insulate economies from volatility in prices of commodities whose revenue the countries depend on

2. Savings funds

Purpose: Intergenerational wealth transfer

3. Reserve investment funds

Purpose: Invest surplus reserves in pursuit of higher returns

4. Development funds

Purpose: Allocate resources to socioeconomic projects, such as infrastructure

5. Contingent pension funds

Purpose: Funding the pension or other contingent liabilities of the nation

While this categorization is a good starting point, most funds have a mix of these objectives. Furthermore, objectives change over time due to policy considerations or accumulation of capital beyond what is necessary for achieving the objective.

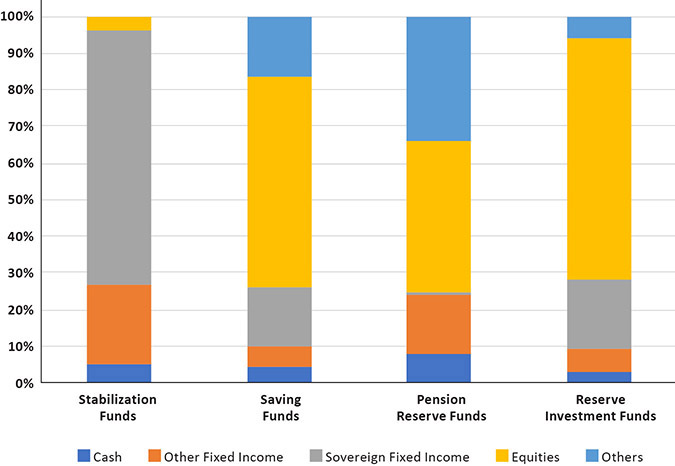

It follows that an SWF’s purpose largely determines its investment objectives, investment horizon, risk tolerance, and asset allocation (see Figure 4.3). Stabilization funds, for one, will need to have sufficient resources invested in assets that are inversely correlated with the economic risk they intend to mitigate—and must be liquid enough to fund the need when it arises. Therefore, it is prudent for them to consider lower-risk investments, often with shorter holding periods. One example is the Russian Oil Stabilization Fund, which invests mostly in fixed-income assets in US dollar, euro, and the British pound denominations. Given its aversion to higher-risk options, this and other such SWFs will not be good prospects for alternative investments.

FIGURE 4.3 Asset allocations at sovereign wealth fund, by type of fund

Source: IMF, Global Financial Stability Report (April 2012)

Savings funds are better suited for longer-term investments, and by extension, alternative assets. They capitalize on market disruptions by investing in and increasing exposures to depressed assets during turbulent times, with the full expectation that they can wait for the conditions to return to normal over time.

Given the multiplicity of SWF objectives, there is significant dispersion of asset allocation among these funds. As such, GPs and fundraisers should avoid a “birds of a feather” approach when soliciting SWFs, customizing their marketing pitch to specifically address the needs of each fund.

While you could say this about any institutional investor, there are two main differences: (1) SWFs’ investment objectives and mandates are the most dispersed among institutional investors, and (2) SWFs have extremely large AUM; so there is a larger return on investment to the GP in creating bespoke strategies.

The average SWF allocation to alternatives is skewed toward private equity, but remains below the target allocation. As such, SWFs present a promising opportunity for GPs that can display their prowess in helping these funds reach their portfolio objectives.

SWF SPENDING POLICY AND ITS INVESTMENT IMPLICATIONS

Unlike endowments, foundations, and pension funds, SWFs do not have a predictable spending pattern. Their expenditures are usually quite volatile. This unpredictability and volatility might be a problem for any institutional investor’s strategic asset allocation and liquidity management, but extremely large SWFs can handle it. Given their size, they can afford to keep a portion of their assets liquid.

Therefore, even in severe market declines (such as during the 2008 financial crisis and the Covid-19-induced bear market in 2020), SWFs have the wherewithal to opportunistically invest in distressed assets, often as a “white knight” for companies in financial distress. Some notable examples are ADIA’s investment in Barclays, Kuwait Investment Authority and GIC’s investment in Citigroup during the financial crisis, and the Saudi Arabia Public Investment Fund’s investment in cruise operator Carnival during the Covid-19 pandemic.

However, most SWFs have clear guidelines, if not explicit rules, for the transfer of funds between the SWF and the ownership entity. Such clarity is essential for the SWF to practice and adhere to an effective strategic asset allocation.

SWF PERFORMANCE

Annual returns for SWF portfolios from 2016 to 2020 have ranged from 4 to 9.4 percent. Since most savings and development SWFs are not pressured to meet spending requirements, they can afford to take a very long-term view compared to other investors—to their great advantage. SWFs have been more than willing to take the illiquidity of long lock-up investment vehicles such as private equity, real assets, and hedge funds, so long as they are adequately compensated for the risk. A large asset base also gives SWFs the freedom, and perhaps even the necessity, to make direct investments, more than any other institutional investor.

SWF STRUCTURE AND STAFFING

There are very few SWFs worldwide, which makes this terrain more navigable for marketers. This is not an easy mission, by any means, because SWFs have the most disparate objectives and operations among institutional investors. Their organizational structures are dispersed and constantly evolving. While some of that evolution is due to the nascency of SWFs, the rest is intrinsic to any organization that has an outsized influence in the marketplace.

Broadly speaking, there are three main legal structures for SWFs:

1. Separate legal entity (e.g., GIC, KIA, ADIA)

These structures usually invest through a mix of direct investments and allocations to external managers. They may occasionally act as an outsourced CIO to manage assets for other entities of the sovereign.

2. State-owned corporations (e.g., Temasek)

This structure is similar to a holding company setup, where the SWF takes an active role in the company in which it has an investment; these SWFs tend to have a very concentrated portfolio.

3. As an account of the central bank or other sovereign entity (e.g., Chile, Botswana)

Typically, the investment mandate is carried out by multiple external managers or funds to implement its portfolio objectives.

Many large direct investments come from SWFs that are structured as separate legal entities or as state-owned investment corporations. They generally have dedicated staff responsible for asset allocation, manager search, due diligence, performance monitoring, portfolio risk management, and reporting. Some of them also have internal fund managers—which makes them a multimanager fund. The bottom line: it is important for a fundraiser to understand the SWF’s investment strategy to see if the manager’s fund will compete with internal fund managers or complement their activities. In this case, marketing efforts should center around the parameters of value proposition and negotiations.

Most SWFs have asset-class-based team structures: private equity, venture capital, real estate, real assets, infrastructure, or public equities, and so on. Those that are private-equity-like with fixed-time structures may be grouped together. Sometimes, there are geographically focused teams, especially among the Middle East SWFs that have large allocations to specific regions. These teams often operate with relative autonomy within the boundaries of the asset allocation policy limits.

These asset-class-based teams also have an operational management group responsible for implementing strategic asset allocation, as set by the fiduciary board of trustees (or an equivalent entity). Operational management is responsible for administration functions, in addition to portfolio management. Investment decisions flow through in a similar fashion to other institutional investors—with investment staff researching and recommending an investment within their teams, which is then rolled up to an operational management group.

While it is common for an investment team and operational management to make investment decisions, in many cases these can be vetoed by the board. The board is usually composed of representatives of the ruling affiliation and sovereign powers, who are aligned with the dispensation of the nation’s rulers and their strategic and political objectives.

Governance, supervision, and operating structures of SWFs are complex. The structural construct underpinning the SWF might seem similar to any large institutional investor, given that decisions appear to be made at the lower levels with approvals sought at higher rungs of management. Reporting structures can be rigid and are subject to heavy bureaucracy. Practically all fundraisers and a large proportion of current and former employees of SWFs voice concerns about red tape they encounter in the asset allocation and investment management processes.

Decisions can be vetted and challenged throughout the process, and the interests and concerns of different actors can be as varied as the number of people associated with it. Given this robust, laborious, and time-consuming process, decisions are usually not swift, nor are they changed once finalized. Therefore, SWFs take relationships with GPs very seriously, and these relationships tend to be long term. GPs and marketers must have patience and perseverance. They should also understand an SWF’s decision constraints before allocating significant fundraising resources behind the effort.

ASSET ALLOCATION AND MANAGER SELECTION

As with other institutional investors, SWFs’ criteria for manager selection follow a similar track of finding a portfolio fit, alignment with the strategic asset allocation, and risk allocation. Given the diversity of SWFs and multiplicity of complex and intermingled objectives, it is difficult to generalize asset allocation considerations or processes. However, larger SWFs do share common factors in allocating to GPs.

The underlying questions during manager selection are: Why this asset class? Why this strategy? Why this manager? SWFs are public entities and national assets. It is important, as with political decisions, to ensure there is broad consensus—allowing no unilateral or unchallenged decisions by the participants in the decision process. Every decision needs to be seen as thoroughly vetted. This starts from the setting of an investment policy and strategic asset allocation.

SWFs set investment policies with input from the board. During this process, they may speak to domestic stakeholders, external consultants, multinational bodies like the IMF, and even other SWFs from friendly countries to get their perspective and learn from their experience. The fund’s objective and ruling affiliation’s risk tolerance determine investment policy and strategic asset allocation. Implementation of strategic asset allocation is delegated from the board to operational management and the investment teams. Typically, a benchmark portfolio is established at the onset of implementing a strategic asset allocation for both compliance and performance measurement.

Historically, before SWFs were established, countries needed to invest “temporary” surplus to preserve the purchasing power and shield the domestic economy from the so-called Dutch disease or resource curse—the notion that abundant resources may be a curse rather than a blessing.12 There was a bias toward liquid, fixed-income investments. That changed with the formal establishment of SWFs and delegation of investment activities to professional investors. Today, most SWFs are global investors with a strategic asset allocation weighted toward equities and alternatives, with allocation to alternatives increasing since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Between 2002 and 2016, SWF allocation to private markets increased from $61 billion to $1.66 trillion.13 However, since then, asset allocation has not increased and remains significantly below their own target allocation. Fund size is a good predictor of asset allocation, with larger funds allocating more to private markets, given that they can endure illiquidity for longer periods in search of higher returns.

One clear trend among SWFs is that the incremental capital they received has gone disproportionately to alternatives, especially private markets, after the fund has reached a threshold liquidity through their fixed-income allocation. This means allocation to private markets has come at the cost of that for fixed income.

Similarly, 34 percent of SWFs globally are actively investing in hedge funds.14 Average allocation of SWFs to hedge funds increased from 7 percent of AUM in 2016 to 8.2 percent in 2017. Not only are they direct investors in hedge funds, but they also invest through funds of hedge funds—tapping into existing relationships and expertise of the fund of hedge funds during the SWF’s initial foray into hedge-fund investing, and later to concentrate on relationships with fewer outsourced managers.

SWFs have been active direct investors in domestic companies, sometimes as a lender or stockholder of last resort—as seen during the 2008 financial crisis when the Chinese SWF (especially Central Huijin Investment) injected liquidity into three of the largest Chinese banks (ICBC, Bank of China, and China Construction Bank) to stabilize the Chinese banking system during a challenging time. SWFs also can act as a holding company for domestic investments of government-owned or linked companies such as Temasek’s stake in Singaporean companies like SingTel, DBS, Singapore Airlines, and CapitaLand. However, such investments will not necessarily be of interest to GPs and fundraisers, except to understand the competition they face for a SWF’s investment dollars and to recognize the impact of SWFs in markets where they operate.

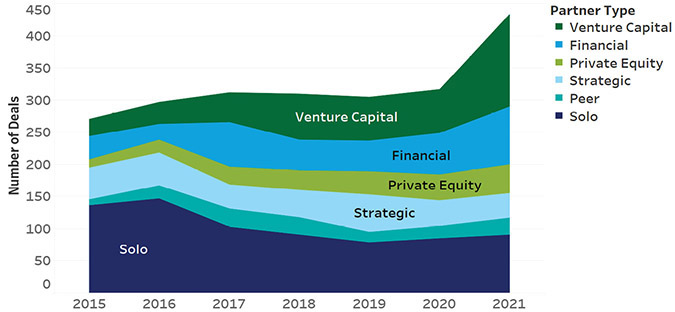

SWFs have shown a higher affinity for co-investments and direct investments compared to other institutional investors (see Figure 4.4). While private equity managers have customarily offered co-investments, it is becoming common for hedge fund managers to offer co-investments as well to entice reluctant large institutional investors, including large SWFs, to allocate significant capital to them. SWFs are not only able to invest copious amounts of capital on a low-fee or no-fee basis, which reduces their investment costs, but they are also able to selectively allocate capital to deals that are expected to generate higher returns without being restricted by the limitations of the fund’s terms.

FIGURE 4.4 SWF direct investments by number of transaction and type of partner

Source: https://ifswfreview.org/long-term-trends.html

As the population of senior citizens rises globally, SWFs will need to allocate more assets to alternatives in search of better returns to sustain wealth across generations. They are also cautious about not overallocating to alternatives, which can result in unintended consequences, such as not having enough liquidity to cash in on market disruptions.

With SWFs’ increased allocation to private investments globally, one question they grapple with is whether this asset class’s superior returns are sustainable, especially in an inflationary environment where yields on lower risk and liquid traditional assets (fixed income and listed equities) are extremely low. While these concerns have some basis, we do not see that as an impediment, much less a deterrent, to sustained higher allocations to alternatives—primarily infrastructure, real estate (including land banks in some cases), and private equity. Given the scale of capital to be invested and the sustained long-term returns needed by SWFs, alternatives are among their best options for the foreseeable future.

However, despite increasing allocation to alternatives, the SWF median allocation remains below their own strategic asset allocation target. “Preqin Sovereign Wealth Funds in Motion” report of May 2021 shows a shortfall of 4.1 percent in private equity, 3.3 percent for real estate, and 3.1 percent for infrastructure. Hedge funds saw median target allocations decreasing from a high of 8 percent in 2016 to 6.1 percent in 2020.15

There are several SWFs with an active and growing private equity allocation, but no hedge fund allocation. Lack of transparency is the primary impediment for state-sponsored funds adhering to specific policy restrictions. However, owing to pressure from SWFs, the Hedge Fund Standards Board and the International Forum of Sovereign Wealth Funds (IFSWF) signed an agreement in 2016 to ensure transparency and mutual exchange of information, which is expected to result in increased hedge fund allocations from SWFs.

Given the large checks SWFs write, they favor separately managed accounts for more control and flexibility. These accounts—in addition to offering negotiated fees (significantly far from the usual 2/20 model), offer full portfolio transparency, an ability to adapt the manager’s strategy to adhere to a specific mandate (e.g., ESG, Sharia-compliance), and place limitations on using leverage. They also let SWFs avoid co-investor risks on fund liquidity during difficult times, and allow allocation to a smaller but high-performing GP without running afoul of internal policy controls around maximum exposures to a commingled pool.

One key trend for fundraisers to note: like most other institutional investors, SWFs are increasingly paring down the number of GP relationships. This increases the inclination to deepen relationships with fewer managers, concentrating investments among multiple offerings of the same manager—which one could argue is itself a risk. Already, larger asset managers were favored to win SWF mandates due to their ability to absorb and invest the capital without affecting investment performance. This trend makes it more difficult for smaller and emerging managers.

SWFs are more willing to underwrite concentration risk, especially in allocations to emerging markets and alternatives, compared to other investors. Also, they view an inability to meet its investment objectives (such as stabilization, transfer of wealth to future generations) as a worse outcome than being weighed down by traditional investment risk metrics such as volatility and concentration. In fact, savings funds have a higher affinity for short-term volatility. They are able to hold on to investments for a longer duration and mitigate the impact of such volatility, while simultaneously generating higher returns as a compensation for assuming greater risk.

Another recent trend among SWFs is a focus on ESG policies. The heightened interest has resulted in SWFs excluding entire sectors, such as tobacco and polluting industries, from their universe of investments; instead, they are directing investments to poorer countries to aid in their development (e.g., Temasek and Qatar Investment Authority’s Africa-focused allocation) and favoring sectors viewed as beneficial to the country’s strategic and political objectives (renewable energy and healthcare). With their size, ability to take an activist role, and patient capital, SWFs can significantly influence companies, industries, and countries to improve their sustainability standards and shore up the governance of companies.

WHY DO SWFS PREFER TO INVEST ABROAD?

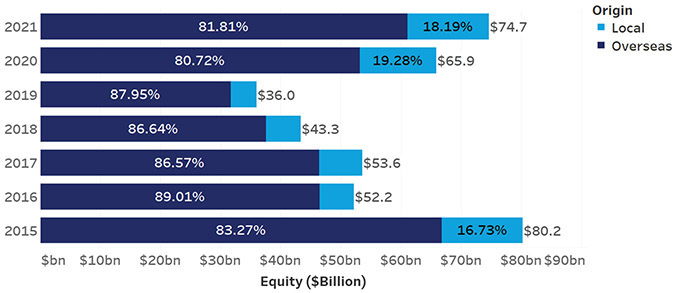

One characteristic of most major SWFs is their preferential allocation to foreign assets compared to home-country investments (see Figure 4.5). Primary reasons driving the preference include:

FIGURE 4.5 SWF direct investments by value ($bn): local versus overseas

Source: https://ifswfreview.org/long-term-trends.html, IFSWF Database 2021

• Most commodity-rich countries are overreliant on commodity revenues. They lack sufficient domestic investment options to adequately diversify risk away from commodity price fluctuation.

• During periods of elevated commodity prices, increased foreign currency receipts cause real currency appreciation. Appreciation hurts other domestic producers and exporters. Allocating to foreign assets helps mitigate the impact of commodity price-fueled currency appreciation. For commodity producers, establishing a SWF is a way to ward off the Dutch disease or resource curse.16

• The return on investment will fall when the domestic economy is shocked with a large infusion from surpluses. Foreign assets can be gradually and systematically repatriated to avoid such shocks.

• They are not limited to domestic options for risk allocation. SWFs can choose to invest in the best options globally, instead of being tied to the limitations of potentially suboptimal domestic risk/return trade-offs.

• SWFs seeking stable longer-term returns are predisposed to higher real estate and infrastructure allocations. The number of projects that can absorb large capital allocation without impacting stable returns or causing inflation at home is limited for any single nation. A global allocation mandate opens a wider and deeper pool of options.

• Investing in businesses whose risk factors differ from those of the domestic economy is a good diversification play.

DIRECT INVESTMENTS: COMPETITION OR COOPERATION?

Direct investments are an important part of the SWF investment strategy. They become as much a partner as they are a competitor to GPs on some of the larger deals worldwide, especially in real estate and infrastructure. Sometimes they syndicate with other managers and bid for the deals in consortium. However, much of the competition comes from larger SWFs, who have internal teams that function like any fund manager. While SWFs might appear as competitors for the same deals, GPs who can show superior investment acumen and generate excess returns will compel SWFs to channel their allocation to them instead.

REGULATIONS GOVERNING SWFS

SWFs are generally established by a legal or legislative mandate in their home countries and are governed by that specific regulation. However, the regulatory situation in the country being targeted for investment depends on several factors. SWFs that are structured as an account of the country’s central bank or other sovereign entity will be treated as sovereign entities by other countries and will enjoy the tax and immunity privileges they command. On the other hand, the tax treatment of SWFs not structured as an account of the central bank or another sovereign entity will depend on the bilateral tax treaties between the countries and are not accorded any immunity by foreign nations. Another issue is the ever-changing political disposition toward foreign investors, especially sovereign entities that are not transparent.

Despite the sometimes-negative response to foreign entities, SWF participation in equity and fixed-income markets brings benefits: SWFs increase that country’s market liquidity and reduce short-term volatility due to their comparatively long-term investment horizons. Indeed, when a foreign SWF announces an investment in a company, the company’s stock price typically reacts positively. Foreign SWFs have sometimes been viewed with concern, since they are presumed to be less transparent, their objectives are unclear, or they run afoul of a country’s FDI restrictions.

The widely used Linaburg-Maduell transparency index (LMTI)—used to rate the transparency of SWFs—and the accountability and transparency scorecard from the Peterson Institute of International Economics indicate that many of the large SWFs score poorly on their accountability and reporting transparency, especially in the Middle East.17 This lack of transparency may be a cause for concern for some recipient countries. The fear is that the governments controlling these SWFs might pursue political or economic power in the target nation through their investments (especially stakes in strategic and security-related companies).

The Santiago Principles are 24 generally accepted principles and practices—voluntarily endorsed by IFSWF members—that promote transparency, good governance, accountability and prudent investment practices among SWFs.18 The IMF has been a supporter of the Santiago Principles, which aim to maintain a stable global financial system, regulatory compliance in the nation targeted for investment, adequate risk management, and a transparent and sound governance structure.

In 2021, 34 full members and 6 associate members were part of the agreement. The idea is to demonstrate to recipient countries that such investments are carried out under strict economic and financial criteria. Despite the Santiago Principles’ voluntary compliance and lack of an enforcement mechanism, they are a step toward encouraging recipient countries to welcome SWF investment, and not to set up roadblocks under the cloak of national interest or national security considerations.

TARGETING SWF ALLOCATIONS

Fund marketers should understand some SWF-specific issues while seeking an allocation:

1. Check sizes are large. You should have the ability to absorb an allocation without an impact on investment performance. We have seen instances where a fund has had to turn away capital or pare the allocation to a SWF.

2. SWF marketing takes time. You need both patience and perseverance.

3. Location is a constraint. While SWFs are establishing offices globally in locations like New York City and San Francisco, to better understand opportunities worldwide, a GP might still have to gain the confidence of the final decision makers in their home countries. Some funds have opened satellite offices in Asia and the Middle East, where there is a concentration of SWFs.

4. In regions where high touch and personal connections are cultural expectations, local PAs can play a strong role in opening doors to potential SWF investors. While it is rare for PAs to act as advisors to SWFs, they might greatly assist in helping you get access to family offices and other investors in the same region that have similar expectations.

5. Using a regional specialist PA is also beneficial for teams not large enough to dedicate staff to a specific region, as they can serve as an extension of your team in the area and provide you with an assessment of the competitive landscape.

6. Each SWF has a unique set of needs and requirements. Separately managed accounts and bespoke investment strategies offer an avenue to cater to such differences, while also creating a stickiness to the relationship, given the investment of time, resources, and effort to build both the operating infrastructure and the professional trust necessary to succeed in such ventures.

7. Managers who are able to accept and appreciate large check sizes—through preferential terms and as true partners in the SWFs overall investment strategy—will forge better partnerships. Co-investments, facilitating direct investments as a syndicate, creating deal flows for direct investments—all of these will help strengthen relationships between GPs and SWFs.

More than a decade ago, a large SWF said this to the GP pitching for an allocation:

I don’t like funds telling me they treat all investors the same. That may sound catchy to the rest, but for me, I expect to be treated differently, as I have more invested in the fund than any other. The risk and trust I am placing by allocating $200 million to you should never be the same as the $2 million from someone else. So, if it requires you to put in 100 times more effort to service my account, it should be reasonable, and you should be happy to. I expect better terms and conditions for my investment than the rest. It is an absolutely fair expectation.

We agree with that assessment, although not all SWFs or even teams within the same SWF would share that attitude.

CONCLUSION

Given the heterogeneity of objectives, investment horizon, risk tolerance, and asset allocation, marketing to SWFs does confound and challenge fund managers and marketers. But the value of securing an allocation from an investor with deep pockets and longer-term orientation cannot be underestimated. The marketing process can be long and can run into bureaucratic delays even when there is an intent to invest; marketers should account for this in their fundraising plans. Thus far, SWF allocations tend to be skewed toward private equity, but that could change over time. If you understand the specific nuances of each SWF early in the marketing process and possess the necessary persistence and patience, you could potentially see a large payoff at the end of the process.