![]()

CHAPTER 5

![]()

Other Major Investor Categories and Gatekeepers

The preceding chapters covered groups of investors that form a majority of the investment capital allocated to alternatives. This chapter focuses on other very large groups of investors, who together have as significant an allocation of capital to alternatives as the ones we have explored up to now. This group includes insurance companies, funds of funds, registered investment advisors and wealth managers, and feeder funds.

1. INSURANCE COMPANIES

Insurance companies are among the largest holders of assets globally, with more than $33 trillion in assets at the end of 2020, making them an important investor group for fund managers to target.1 However, this market is quite fragmented. There were nearly 6,000 insurance companies in the United States alone in 2019, according to the Insurance Information Institute.2

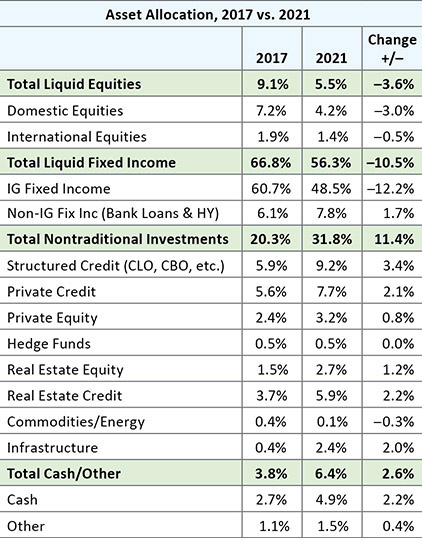

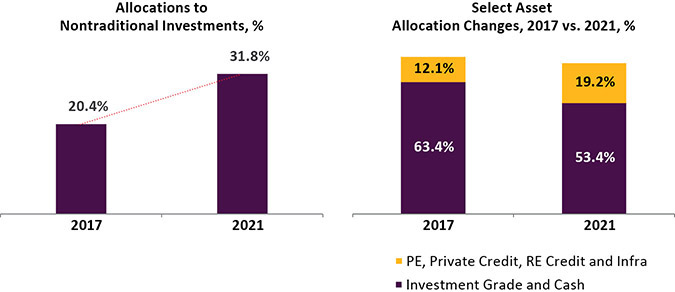

Insurance companies assume investment risk on behalf of their policy holders in return for premiums collected. Traditionally, the premiums collected were allocated to near-risk free assets—US Treasury bills, notes, and bonds. In 2020, bonds and other debt instruments accounted for nearly 77 percent of all investments by insurance companies worldwide.3 However, the ultra-low interest rates over the past two decades, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, pushed insurance company investment managers to look elsewhere for allocation of their risk capital. Nearly 75 percent of insurance companies considered interest rates the primary risk to their portfolios.4 One solution was to increase allocation to alternative investments in search of better returns in a low-yield environment (see Figures 5.1 and 5.2).

FIGURE 5.1 Nontraditional investments have gained market share in recent years

Source: KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation.

Note: May not equal 100 due to rounding. Data as of August 31, 2021.

FIGURE 5.2 Insurers have had to shift their asset allocations in recent years to protect returns—with private credit, real estate credit, infrastructure, and private equity benefiting mightily

Source: : KKR Global Macro & Asset Allocation.

Note: Data as of August 31, 2021.

In the United States, approximately 22 percent of insurance portfolios were allocated to alternatives and structured notes in 2020.5 However, the allocation within alternatives is skewed toward private equity (PE) and private debt, and insurance companies in the United States and Europe have been increasing their geographical diversification in recent years.

Complicating matters is that insurance is a heavily regulated industry across the globe. In the United States, they are regulated at both the federal and local levels. The primary goal of regulation is to ensure that insurers stay solvent. Ironically, this strict oversight can hamper the ability of insurers to invest in higher risk assets such as alternatives, whose potentially higher returns could help them meaningfully cover their liabilities over time. In addition, the inertia from regulatory constraints often leads to the slower allocation of resources—for example, in matters such as recruiting experienced staff to build and manage an effective alternatives strategy—further slowing their path to alternatives.

For fund managers or GPs, it would help to look at insurance companies in a similar fashion as pension funds, but with a much stricter regulatory environment that impedes their allocation to alternative assets. While the allocation may be smaller compared to their size, there are still trillions of available investment dollars for GPs to seek an allocation. Some insurance companies also have in-house fund management teams that GPs are competing against for allocation. Outsourcing is common for their alternatives allocation, with emerging market, high-yield, and structured debt allocation going to external managers.

Insurance companies not only want their managers to have an excellent track record but also to be cognizant of the regulatory environment in which they operate and the constraints they face. The necessary conditions include a track record of generating superior returns across market conditions, diversification benefits, defined investment philosophy and strategy, investment discipline, strong controls and governance, team capability and working relationships, stability of the team (low attrition or churn), and a focus on superior returns.

In most firms, the strategic asset allocation decisions are made by the portfolio management group, which is separate from teams that focus on asset classes and that make investment decisions. Before a deal closes, the decision must be approved by a pricing committee (or equivalent supervisory structure) at the insurance company. Most larger insurance companies have dedicated teams for each asset class. Insurance companies, similar to institutional investors, do not seek to time the market in alternatives. While capital allocation can increase or decrease as a function of various factors, including internal constraints and external investment environment (risk/reward proposition), there is a steady flow of investment dollars from insurance companies to alternative investments irrespective of the conditions.

It is difficult for larger companies with a substantial amount of investment dollars to implement tactical asset allocation decisions quickly. Therefore, they are more likely to keep up a steady flow, even as they move toward longer-term desirable allocations. Given the importance of capital adequacy ratios to protect against insolvency as a result of inadequate risk controls (e.g., AIG during 2008), there is a bias toward assets that have a lower equity requirement. While some insurance companies are comfortable working with a placement agent, others avoid them in favor of internal deal sourcing and due diligence. RFPs are not a common occurrence in the insurance industry for finding new managers or for making a substantial outsourced asset allocation for alternative investments.

Offering a co-investment opportunity, even before an investment is made into the manager’s fund, is a favorable way for GPs to get the attention of insurance companies in the alternatives bucket. Insurance companies find that such “date before you marry” processes give the investment team great insight into the workings of a GP, and the ability to assess quality of deals and depth of their due diligence and value addition to the company before making a substantial allocation to the manager’s fund(s). Some of the primary reasons for declining a manager include lack of transparency, dishonesty, performance volatility in the track record, sizing of deals not commensurate with the opportunity set, self-dealing, and conflicts of interest.

As insurance is a highly regulated industry, insurers rate GP transparency quite high on their list of IR requirements. The composition of Limited Partner Advisory Committees (LPACs) and ensuring that members execute their responsibilities—such as assessing GP conflicts of interests, compliance with LPA provisions, LPAC consent and approval, regulatory awareness, and access to appropriate professional assistance, among others—are extremely important for insurance companies.

Industry insiders expect a trend toward separately managed accounts for larger investments. These would provide transparency and improve control over assets. However, these accounts are only viable for larger insurance companies with expansive assets, due to the need for better infrastructure and back-office support, and allowance for incremental accounting overhead.

Another trend is consolidation among asset managers. Midsize insurance companies that are able to allocate capital to GPs who are not “front page names” will find it challenging, as consolidation results in larger GPs and propensity for bigger checks. In addition, if consolidation involves an existing manager, the resulting culture and process evolution will require a reassessment of the manager and a need to find new GPs similar to the one that was consolidated. Consolidation also results in the crowding out of smaller and midsize LPs in favor of larger checks. This opens opportunities for managers of alternatives funds who want to establish or expand their relationships among insurance companies.

2. FUND OF FUNDS

Fund of funds (FoFs) are commingled pools of capital that invest in other funds (usually around 15 to 20 other private equity or hedge funds). FoFs are essentially portfolios of other funds. There are primarily three different types of FoFs based on their portfolio—fund of mutual funds, fund of hedge funds (FoHF), and private equity fund of funds (PE FoF). We will focus on FoHFs and PE FoFs in this chapter. While some FoFs have a mixed asset portfolio, their importance is largely insignificant to most managers. The need for FoFs is amply substantiated by some of the larger asset managers and wealth management firms, who are responsible for allocating client assets to GPs, as they set up in-house FoFs that cater to the needs of their clients.

The value FoFs bring to the alternative assets industry include gaining access to top-tier GPs, diversification, due diligence capability, entry into nascent markets where information or expertise is scarce (such as frontier markets investments), or exposure to niche or specialist strategies (such as secondaries). They serve as an outsourced allocator for investors who lack internal resources to build and manage a portfolio in a noncore asset class.

Access is extremely important, since many funds have capacity constraints but will accept money from existing investors even if they are “closed,” including from FoFs that have contributed to their earlier funds. In many cases, investors can shorten the time frame required for a new alternatives program (PE or HF) to mature by investing in an FoF that provides access to the underlying GPs at once, instead of having to cultivate these relationships over several years.

LPs eventually migrate to direct investing as their program matures. One other value addition, specifically for illiquid strategies such as private equity or venture capital through a secondaries FoF, is to shorten investment duration. The greatest disadvantage is the double layer of fees—paying underlying funds and the FoF. Furthermore, since allocation is outsourced to the FoF manager, the underlying portfolio construction depends on the manager’s decision. This is less than ideal for portfolio management and risk control by larger LPs who could have had direct access to underlying funds. The investment term is extended beyond the longest duration offered by the underlying funds, since additional time is needed for the FoF to raise capital and source and select managers to make the investment.

According to Preqin’s PE FoFs report, aggregate AUM of the PE FoFs was $381 billion as of 2017.6 By far the largest number of PE FoFs are based in the United States, followed by Europe and China. The popularity of FoFs has been waning over the past decade (capital raised fell from $55 billion in 2007 to $26 billion in 2016), due to investor concerns about double-layered fees. FoFs make up less than 5 percent of the capital raised by private equity worldwide—but that could be a skewed number.

Many emerging managers benefit from FoF allocations. In addition, a larger portion of alternatives allocation from smaller LPs flow through FoFs. For most midsize institutions, the allure of FoFs is due to their access to top-quartile managers who are selective about their investor composition. Given the average size of PE FoFs is $250 million to $300 million, it is easy to see why midsize managers will have better success getting an allocation from FoFs, compared to larger managers for whom checks from FoFs are not meaningful.

PE FoFs also have a longer fundraising cycle, about 1.6 times the time taken by direct private equity funds. Since FoFs must ultimately market their portfolio of underlying managers to end investors, fund managers seeking an allocation from FoFs will find better success by accommodating terms that in turn make the FoF more attractive to the FoF’s investors. These include guaranteed access to successor funds, increased portfolio transparency, fee accommodation for larger checks, and acknowledging the FoF as a conduit for absorbing larger investors from the FoF’s investor base.

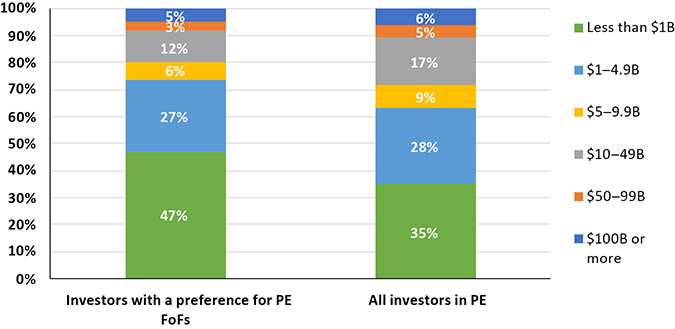

On the investor side, FoFs will have better success with smaller investors (lower than $1 billion AUM) who form the bulk of the potential market for FoFs (47 percent of FoF investors have lower than $1 billion AUM) (see Figure 5.3).

FIGURE 5.3 Investors with a preference for PE FoF by assets under management versus all investors in private equity

Some FoFs have a lower minimum investment requirement compared to the underlying funds, which helps smaller investors diversify their exposure across asset classes and provides better liquidity terms than underlying investments (although at times it ends up hurting FoF performance, due to a focus on liquidity as opposed to performance potential).

Given the large number of private equity and hedge funds globally, it is difficult for most investors (LPs) to have the resources to fully cover the market on their own. FoFs can act as the outsourced arm in sourcing, selecting, and monitoring investments for resource-constrained investment offices or high-net-worth individual (HNI) investors. The cost of outsourcing is weighed against developing an internal program, considering both direct costs (FoF fees versus staffing costs) and indirect expenses (e.g., opportunity cost of denied access to managers, a steep learning curve, and cost of missteps).

FoFs have begun to address the cost obstacle by lowering their fees (from 1.2 percent in 2020 to 0.8 percent in 2017), and carry. They further add value by seeking a fee rebate from underlying managers for larger checks they write, compared to their own investor pool. FoFs have also succeeded in backing emerging managers more amenable to lower fees and gaining access to successor funds, provided strong investment performance by the manager.

Venture capital (VC) FoFs should emphasize that in a sector dogged by “performance persistence” and “high dispersion of returns,” the ability of FoFs to provide continued access to strong managers more than compensates for the additional fee layer with superior portfolio returns in excess of the fee paid.7 Similarly, FoFs seeking an allocation from LPs will find better success by reducing the additional FoF layer fee, increasing transparency, involving FoF LPs in broader decision-making, and providing bespoke portfolio solutions for larger LPs.

3. REGISTERED INVESTMENT ADVISORS AND WEALTH MANAGEMENT FIRMS

Registered investment advisors (RIAs), financial planners (FPs), and other wealth managers are responsible for investment and asset management of primarily the financial assets of an HNI or institutional investor. They are regulated both by the SEC at the US federal level, and by state authorities where they operate. Their typical fees are between 0.5 percent and 2 percent of assets managed. Each individual client portfolio is managed separately, with some characteristics of mass customization applied to the whole group or subgroups as classified by a set of factors, including risk tolerance, liquidity, and investment horizon. These portfolios can be a mix of equity, fixed income, mutual funds, ETFs, and alternatives. RIAs are best suited for investors who want to have an outsourced bespoke or semi-bespoke portfolio compared to an FoF/FoHF, but with the ability to discuss decisions with people managing the portfolio. This can be particularly important for HNIs who want to manage their tax burden, unlike investments in a commingled FoF pool.

Many HNIs and smaller investors who outsource their portfolio management to RIAs are also attracted to alternatives due to the higher returns they achieve compared to traditional investments. Demand from such investors has been a primary driver of RIAs allocating capital to alternatives in recent years. A third of the RIAs offered private equity investments to their clients,8 and that number has been growing in line with client demand.9 While only 10 percent of RIA client portfolios have private equity exposure,10 more than two-thirds are interested in private equity, which points to a large gap between investor interest and allocations by RIAs. There is an opportunity for GPs to close this gap in coming years.

Alternative fund managers should approach RIAs not as a client but as a distribution channel with a strong influence on the client. Alternative funds get allocation from RIA clients in two ways. One is through the HNI for whom the RIA conducts manager due diligence and checks compatibility with portfolio objectives. The second is to be empaneled among the RIA product offerings. This approach includes signing agreements with broker-dealers to make investments available to the agents on the platform.

However, agents are restricted by what their home office allows them to sell. There is a lot of education and business development work, including some market cultivation, that will have to be undertaken by interested GPs. In recent years, unlisted real estate investment trusts (REITs) have taken this approach and have been richly rewarded: monthly aggregate RIA and wire house allocations topped billions of dollars.

The other big reason for advisor reluctance to invest client capital is the time commitment and labor-intensive nature of manager selection and the tedious subscription process. For RIAs who process electronic trades, the lack of “click and subscribe” is an impediment. One would expect, given the long duration of private equity and hedge fund commitments, that RIAs who facilitate these investments and offer them on their platform will also benefit from asset stickiness over the long run. These become differentiating factors for larger clients who will be the most suitable for an alternatives allocation, further increasing their attractiveness and contributing to their revenues. A tangential benefit is that all the allocation to alternatives is outsourced, which improves revenue efficiency for RIAs. By highlighting the benefits of offering the right alternative fund (yours), fund managers can find long-term partners with a growing pool of capital.

Obstacles to working with RIAs include the high minimum investment or commitment amounts of each individual fund, lack of a central repository to source funds, transparency, asset safety, and lack of familiarity with alternatives. Larger funds can afford to invest the resources to educate individual RIAs or groups, prepare educational material for client usage, and create bespoke investment vehicles, including feeder funds structured to accept lower individual minimums. They also can persuade RIAs to make their funds a gateway to other alternatives in the future and can negotiate long-term deals with RIAs in consideration of the substantial investment up front to forge the relationship.

For smaller GPs with limited resources available for marketing, there are other avenues. Some RIAs have created their own alternative investment platforms, and there are third-party platforms that serve RIAs, providing services such as custody (including no fee or low fee) and due diligence to assist them with their alternatives allocation. Technology is rapidly evolving to enable digitized subscription and confirmation.11 Some RIAs have also established unlisted interval or tender offer funds that address issues with lower individual minimums, avoid capital call hassles, remove tax-filing complexity by using 1099s instead of K1s, and boost client confidence by complying with the 1940 Act.12 One key reason GPs should join the RIA pipeline is that these agents become de-facto marketers for empaneled funds without an additional placement fee. This can be substantial savings for assets gathered through the channel.

One caveat: it takes a lot of sales effort to be accepted by RIAs. As such, smaller managers and GPs with less than 10 years in the business should explore other avenues before seeking distribution through RIAs. Real estate managers, however, will be better received, since RIA clients have a high affinity for real estate investments in their portfolio.13

4. FEEDER FUNDS

Feeder funds are special purpose investment funds whose primary goal is to “feed” capital to a master fund, which is ultimately responsible for investing and managing the portfolio. Feeder funds collect capital for investment into the master fund in a master-feeder structure or act as a sub-fund for the master fund.

The master fund can have multiple feeders for several reasons. One is to distinguish capital for tax or regulatory purposes (e.g., on-shore and off-shore structures, US and non-US investors, taxable and nontaxable investors, or for exclusion of certain investments that would otherwise be acceptable to the master fund). Another reason is to set up a structural tool to aggregate assets into a larger pool of capital, as in the case of commingled investments from smaller investors to make the fund large enough to entice a selective GP and simplify investor relations (IR) and operational management of the fund. Profits and losses are distributed in proportion to their investments in the master fund, except in cases where the feeder is meant to exclude certain types of investments. In this case, the feeder will receive allocation in other investments of the master fund (excluding prohibited investments), proportional to its investment in those alone.

Feeders can either be sponsored by a GP or an outside entity. In case of manager-sponsored feeders, there is no distinction between the master and the feeder as far as marketing is concerned, except for how the allocation is directed. We are more interested in the non-manager-sponsored feeders in this section, whose primary role is asset gathering for the master fund.

Here are key issues to consider while marketing feeder funds:

1. Feeder funds may be the only way for smaller investors to access a selective manager whose minimums for investment may be multiples of what they are able to prudently invest.

2. There is an additional layer of costs for setup and operating costs of the feeder.

3. In case of a wrap product, there are additional fees collected by the intermediary for creating the feeder and providing access to the investment.

4. GPs may prefer feeders to avoid dealing with too many investors directly, but this also creates distance between the manager and end investor. This would not be an issue for the larger managers with established brands; however, smaller managers dependent on small checks to collect a respectable AUM will find that the investor-manager distance can be detrimental to long-term growth unless an effective IR program is implemented. This could include open access to all investors in the fund. Whether or not they are directly investing in the fund or through a feeder, investors can be provided all investor communications, or are invited to special events such as webinars targeted at feeder fund investors.

5. LPs will not be able to conduct adequate due diligence but will be dependent on the manager of the feeder. This causes single investment feeders to be treated similar to FoFs, but lacks their diversification benefits. The manager of the feeder fund may, in some instances, procure access to the master fund’s data room for its own investors.

6. Investors have been skeptical about somewhat opaque feeders, after seeing multiple feeders in the Bernie Madoff scandal. The largest feeder was the Fairfield Sentry Fund, sponsored by the Fairfield Greenwich Group, which raised $1.7 billion for its Madoff feeder. The allure to retail investors was access to an exclusive manager like Madoff, so they glossed over the lack of transparency, inadequate due diligence, and additional fees charged by the sponsor. There is less concern about the master fund in the case of well-established, blue-chip managers, but investors can and should always conduct diligence on the provider of the feeder.

Managers of feeders should create as much transparency as possible and shorten the distance between the fund and investor, while also providing value-added services to make the fees worthwhile. This includes thorough due diligence of the master fund, similar to what is expected from a FoF manager. Investors today need concrete evidence and not just claims of adequate safeguards, in light of issues that surfaced during the Madoff fraud. A thorough documentation of the processes, policies, and execution, in addition to evidence of compliance with such processes and policies, will be crucial. Face-to-face meetings between the master fund’s manager and prospective LPs will go a long way toward winning over skeptical investors.

Feeder fund sponsors may be able to negotiate more favorable terms or qualify for better fee breaks in an aggregated feeder fund vehicle than investors would get on their own. LPs may also obtain the benefits of consolidated reporting across feeder funds in their portfolio by using the technology platform of a feeder fund sponsor. Feeder fund sponsors may be able to negotiate more favorable terms or qualify for better fee breaks in an aggregated feeder fund vehicle than investors would get on their own. Investors may also obtain benefits of consolidated reporting across feeder funds in their portfolio by using the technology platform of a feeder fund sponsor.

5. GATEKEEPERS

Gatekeepers are specialist advisors and consultants who assist investors with investment decisions and are a vital part of the alternatives investment process. They assist with creation of investment objectives and policies, portfolio construction and monitoring, and manager selection. As the name suggests, a manager’s path to the LP goes through the “gatekeeper.” Therefore, some fund managers and marketers wonder whether gatekeepers are obstacles or enablers during a fundraise—depending upon how well it is going. The better question for any GP is to ask, “How do you build a positive and constructive relationship with them, instead of a perfunctory, or inimical relationship?”

Gatekeepers play a large role in the asset allocation decisions of many different institutional investors and especially most pension funds—both public and, increasingly, private pensions. They are considered fiduciaries in the process. All gatekeepers conduct due diligence on GPs. Some offer services that goes beyond due diligence—essentially becoming an extension of the investor’s staff and serving as an unbiased and objective “prudent person” and a “second set of eyes” for the investor. What they look for in a GP should parallel what a capable LP would consider for investment. After all, they represent LPs and seek to meet their clients’ investment goals. Here are some of the primary metrics that gatekeepers evaluate a fund on:

1. Performance. Good track record, outperformance vis-à-vis risks, source of outperformance, consistency of returns, batting average, correlation with other asset classes, performance attribution to investments and team members (given their network, they can also parse out the source of performance and the attribution), deep and accurate understanding of the market.

2. Brand and reputation. Not just name recognition, but character and investment quality.

3. Team. Alignment of interests between the LP and GP, conflicts of interest, investment oversight and diligence, a stable and capable team.

4. Fund mechanics. Investment oversight and diligence, distribution of fund economics, disciplined investment process and execution, transparency, quality of IR and communication, alignment of pay and performance, robust bench strength of future leaders for the organization, adequate staffing, and other considerations.

Some gatekeepers act purely as advisors and others make investment decisions. Some institutions will not consider an investment without a recommendation by their consultant, while others seek confirmation after they have made decisions internally. Gatekeepers’ services range from being pure advisors and providers of independent, third-party opinions on the suitability of an investment (prudent person opinions) to providing quasi-investment and quasi-CIO services that include asset allocation, policy development, co-investment decisions, risk management, portfolio construction, performance monitoring, and ongoing due diligence. In every case, they act as a first screen for the investor.

For marketers, there is no good answer as to whether they should solicit the LP or the gatekeeper for an allocation. It depends on circumstance. The authors typically approach both simultaneously, creating a push-and-pull marketing strategy.

Building relationships with consultants is a one-to-many approach and can be extremely productive. For the right product and team, consultants can broaden your reach to their entire investor base. Typically, consultants are open to accepting meetings—or at least to review fund marketing materials—as they have a larger staff compared to most individual clients and the meeting is another opportunity to benchmark and gather information about competing opportunities in the market. Most consultants also maintain a database of managers and update this information regularly, including performance information coupled with their observations.

In some instances, managers may fail to get a response from a consultant, and hence soliciting investors directly is also important. In one example, Hemali was setting up an Asia road show for one of her managers and contacted a number of LPs in the region. Within days, a consultant who represented many of the investors she had approached reached out to her requesting an update meeting. While an investor might decline a meeting, they may ask the consultant to review and monitor the fund if it is interesting to them.

Consultants and advisors, like placement agents and other service providers, have a vantage point that straddles the GP and the LP world. Given the flow of information they receive from either direction, they can serve as conduits of information and also provide a “sanity check” on the GP’s market information and assumptions. Managers who develop a functional relationship and rapport with a group of consultants and engage them prior to fundraising can build relationships more easily, better understand their clients and their needs, and obtain valuable feedback on their strategy and competitive landscape.

CONCLUSION

While each group of investors (E&Fs, pensions, and others) has enough capital to incentivize a manager, we view it as an optimization problem. Managers who are building successful deal pipelines and executing are constrained by time and resource availability. Understanding investment objectives of different investor groups is a good starting point to assess if the product you are pitching would be an appropriate fit for an investor. Subsequently, you can construct a marketing strategy that is broad enough and not overly reliant on any one investor or investor group, and ultimately focus on obtaining allocations from a targeted list of investors with the highest probability of success. As with any marketing effort, the cardinal rule is to “first, know your customer,” which provides the critical foundation for successful fundraising.