![]()

CHAPTER 12

![]()

Due Diligence

Allocating capital to a fund manager is a complex decision for an investor. The cost of a wrong decision is quite high. Unlike a physical product, which comes with an actual product to test and review with performance guarantees, professional services affords no such assurance and LPs rely on due diligence prior to making an investment decision.

Allocating capital holds risks for the LP. While the GP must abide by certain expectations and boundaries, they manage investor capital without any real supervision from LPs. Alternative assets show the highest dispersion of returns compared to other asset classes, and obviously returns cannot be ascertained a priori. A GP is not required to hold a certification or license to ensure adeptness in managing LPs’ money. While the pedigree of a GP can be a substitute for skill certification, there is no measure for integrity.

This makes it difficult for an LP to determine which GPs can generate the best returns in the future, so in-depth due diligence provides some assurance that the GP’s performance is likely to meet expectations and that risks are well understood. It is the modern-day equivalent of looking a horse in the mouth; LPs will rightly follow the maxim “trust, but verify.” GPs should not only understand the reasons for investor due diligence, they should invite the scrutiny to build a strong relationship based on mutual trust.

The 2008 global financial crisis put the spotlight on issues of governance and performance volatility in alternatives. Additionally, instances of fraud perpetrated by principals and employees of alternative investment funds—Bernie Madoff, Sam Israel, Daniel Kamensky, to name a few—have led LPs to demand adequate risk controls prior to investing.

DUE DILIGENCE PROCESS

Every LP follows its own process for due diligence, measuring GPs on a set of criteria that can change based on how appropriate an investment is for their portfolio. However, there are some common checks that most investors will do.

Desktop Due Diligence (DDD)

The usual first step in the due diligence process is desktop due diligence (DDD). Past the initial screening of a GP and after ascertaining interest, LPs want to further understand the fund’s strategy, process, terms, regulations, and risks. They also want to conduct a quick initial vetting of the investment management team. This is done from the comfort of an LP’s desk with access to multiple data sources, supplemented by a few quick phone calls. DDD could be further separated into three broad and overlapping buckets: document review (a review of documents and/or data room access for confidential information); confirmation of claims by analyzing fund performance and its fit with the investor’s portfolio, and by cross-referencing public and private databases for information verification; and preliminary investigation into the track record, team, and background, and by using online searches about the team and its investments to verify claims.

Many LPs will first ask prospective GPs to fill out a due diligence questionnaire (DDQ) asking a broad set of questions to help them make a decision. Most LPs rely on popular DDQ formats, such as ILPA,1 AIMA,2 or MFA3 questionnaires. To address common LP concerns, funds typically create a standard DDQ to share with prospective clients. The practice of using standardized DDQ templates has opponents, who believe GPs use DDQs as a marketing tool. A standardized document from a respectable entity such as ILPA or AIMA could potentially lull LPs into accepting ill-suited answers to legitimate questions. While that could be true, sophisticated LPs will use a DDQ as a starting point that covers relevant topics, and a review of the DDQ can actually prompt more important questions to explore with the GP.

Access to a data room4, 5 that houses important LP documents and confidential information is usually provided right after confirming investor interest. Sometimes, this would entail the LP signing a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) to review documents. Most data rooms have built-in NDA requirements during an initial log-in.

Almost all data room providers feature access tracking and reporting—information that would be valuable in marketing to nudge LPs if they have not accessed the information or follow up with investors who have spent a lot of time reviewing materials. GPs should also keep data access current and revoke access for LPs who no longer need it. It is good practice to connect with the LP before any access is revoked; this also provides an additional opportunity to confirm or rekindle investor interest.

After reviewing documents, LPs may send follow-up questions to GPs. Some LPs prefer a surprise call to confirm information on sensitive topics or to hear impromptu responses that they may deem more credible. GPs and their representatives must handle such impromptu calls with an appropriate level of diligence. If junior staffers are asked questions they cannot answer well or are requested to comment on sensitive topics, they should be encouraged to include senior partners in the conversation, as investors appreciate hearing directly from the partners.

Many LPs will also conduct online searches for publicly available information on the GP, the fund, past and current investments, the team, prior employers, and other public records relevant to their investment decision. This preliminary search serves to confirm claims presented by the GP and uncover any intentional omissions. Only after a positive outcome from DDD will LPs allocate further resources for the task.

Investment Due Diligence (IDD)

After conducting DDD, what follows is a series of calls, emails, and in-person meetings, including a visit to the GP’s office, and perhaps even the portfolio companies. Investment and operational due diligence (IDD, ODD) can be simultaneous or separate streams depending on the LP and the topics could also be overlapping. Information that LPs seek in this phase may include general fund and firm information, investment strategy and philosophy, investment process review and analysis (research, selection, due diligence, portfolio addition, performance monitoring, eventual exit), fund terms, fund oversight (IC, LPAC, board of directors including independent directors), and so on.

Due diligence on a new GP necessitates an additional level of scrutiny and assessment of risks specific to that particular firm. These include determining whether the GP’s experience and track record are appropriate for the fund strategy. Seasoned LPs are aware that the conditions responsible for their track record may not be replicable due to shifting investment environments and other “environmental” factors such as access to a specific data set, infrastructure, supervision, and proprietary networks that helped generate those returns. Some factors that are considered in making that determination include market conditions during the same time period, actual portfolio risk relative to benchmarks and comparatives/competition, use of leverage, and consistency of returns. GPs will be better served to critically examine these conditions and be confident in their ability to bridge any gap ahead of a due diligence meeting. Furthermore, if the LP worked with a prior GP that had shortcomings, strive to present how your firm can add value without speaking badly of the predecessor. A “lessons learned” section is usually well received by LPs.

While a fund’s track record and performance are important, what is even more relevant are qualitative assessments of the GP. For example:

• Was the performance achieved while staying true to the investment strategy and philosophy?

• Does the GP have a well-defined, documented process for the team? How does the GP address deviations from that process?

• Does the GP track and adequately correct missteps, mistakes, and inadequacies? Is there a concerted effort to learn from mistakes and prevent them from recurring?

• While the portfolio manager is ultimately responsible for the investment decisions and performance of the fund, is there a process where decisions are scrutinized and challenged to ensure that complacency and overconfidence do not cloud investment judgment?

• Is there a reasonable basis to expect the GP to continue performing in a similar fashion during different market conditions (or perform directionally in a specific market condition for a cyclical strategy)?

• Is the performance due to chance, or a result of the strategy and the GP’s skill?

• Are outliers contributing disproportionately to the performance of the GP, and is there an expectation such outliers would exist in the foreseeable future?

• Is the GP actively engaged with the investee company, and do they address underperformance appropriately? Does the track record show they are able to exercise control and prevent investment losses at underperforming companies?

• Is there an abundance of investment opportunities to choose from? In PE funds, has the GP developed an active and broad deal pipeline (including an emphasis on proprietary deal flow) that is sustainable and of high quality? Is the GP entering into an investment with thoughtful and specific plans to create or unlock value, and is that plan fully executed through an eventual exit?

One common question LPs focus on is scalability of the strategy. How much capital can the strategy easily deploy without impacting performance, and does total AUM currently deployed under this strategy (including by competing firms) remain under the upper limit? Not only do GPs need to have a clear and compelling response to LPs, they should also ensure the rest of the investment team buys into the AUM limits strategy.

For first-time funds, LPs are typically interested in the growth of the firm and future fund sizes. GPs should be thoughtful with their answers—for example, future fund sizes can be determined by investment staffing levels and expected exit timelines will depend on their strategy and process. A response that includes a plan, process, and commitment to stay devoted to the strategy and philosophy for the foreseeable future is seen as more convincing as it takes away one more portfolio uncertainty for the LP.

While it is impractical for a portfolio manager to meet with every prospect, you should ensure LPs who have progressed in the due diligence process are able to secure a meeting before deciding. LPs will also interview members of the team to ascertain their roles and experience and judge their service quality. LPs might view any reluctance as a sign that “something is off.”

If a personnel change means the team would lack depth to pursue the fund strategy, LPs need to account for such risks. Another issue LPs focus on is the “culture” of the team. They want to see a positive work environment, an ethos that focuses on investment results, and “doing the right thing.” LPs have walked away when they felt the firm’s employees were not treated well, working conditions were poor, or simply no one other than the founder had a voice. Small gestures, subtle nuances, and the tenor or cadence of interactions within the team can convey a lot to an experienced investor. GPs should understand that culture cannot be faked, and experienced LPs are quite good at identifying incongruities between words and action. A positive culture is not just a due diligence checklist item, it is often the reason for a firm’s continued success.

Additionally, LPs will seek terms that are offered to other investors who have made similar capital allocations to a fund. GPs should expect such questions and be prepared to answer them candidly. This would include any side-letter agreements, most-favored-nation (MFN) agreements (meaning if some other investor is offered terms that are better than their current terms, the better terms will be offered to the investor as well), or preferential terms entered with any other LP; when check sizes are in the same range, the LP will often ask for a similar agreement. If offering such terms to a new investor is an impediment, GPs should be prepared to explain the situation carefully to new LPs or risk losing a potential investment.

One consistent investor due diligence request is for full disclosure of conflicts of interest. GPs are expected to invest alongside LPs at levels that are meaningful to them, and at liquidity terms that favor LPs. Related persons6 serving in key positions in the firm or with authority over client funds is seen as a conflict. Such responsibilities are best assigned to outsiders, including a preference for regulated third parties (such as custodians, administrators, etc.) to be solely in-charge of actual client assets. Sometimes the conflict may be unavoidable, especially at a small or new firm with limited assets, but GPs should be prepared to defend it during due diligence and potentially still be at a loss due to the conflict.

Operational Due Diligence (ODD)

Alternative managers enjoy an extremely high level of autonomy in their investment process, and LPs want to ensure their capital is safe and performance is on par or better than expected. Due diligence of alternative managers tends to be broad, detailed and robust. In addition to investment issues, good LPs will look into noninvestment-related points of failure during this stage. Operational due diligence (ODD) is necessary not only to prevent a collapse due to fraud or poor risk management, but also to ascertain proper functioning of a fund and an ability to fully execute a proposed strategy.

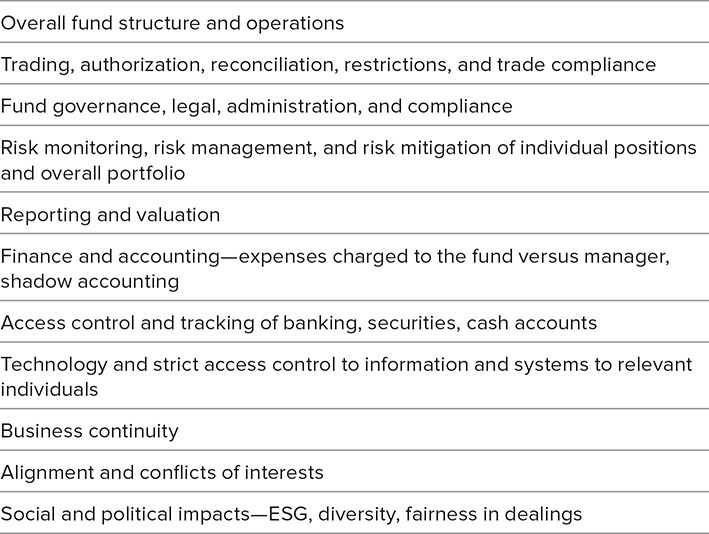

Even as early as 2003, operational issues were the cause for failures of half of the hedge funds analyzed by consulting firm Capco.7 Problems included improper representation or valuation of investments, lack of proper controls around cash movement, improper trading or trade processing, and other operational issues. As a result of past fund failures, there is a growing emphasis on operational excellence by GPs and LPs, especially in a technology-dependent world that grapples with technical glitches and nonavailability of critical infrastructure such as power, telecommunications, and internet connectivity (see Table 12.1). Due diligence will focus on middle- and back-office functions of the firm and occasionally on the service providers that perform the function on behalf of the fund.

TABLE 12.1 Major Operational Topics for Assessment and Confirmation During Due Diligence

Most often, ODD is conducted on-site, with some amount of preparatory work done up front so that shortcomings can be identified and remedies may be recommended by the due diligence team. Rarely is an investment turned down immediately unless the GP is unwilling to accommodate changes and remedies sought by the LP.

Most LPs will want independent verification of financials and performance information provided in a marketing pitch (such as audited financial statements or a direct message from the fund administrator providing the fund’s NAV, performance, and explanations for any restatements). By making a directory of independent service providers available to LPs and setting up service level agreements with them, verification can become less of a hassle during fundraising. In addition, valuation of assets and procedures for valuing illiquid or infrequently traded assets must be established and documented for LP and auditor verification.

Adequate staffing is necessary for the proper functioning of a fund. High turnover is a red flag for most LPs. LPs will seek information on the size of the staff, their experience, capability, and any redundancies and contingencies. Many investors seek compensation history and variable compensation related to investment performance. Funds where the economics, especially carry or performance incentive, is concentrated on certain individuals instead of being adequately shared with the broader investment team, should not expect to gain favor from LPs.

In addition, some LPs will demand a staffing history and information on any outsourced support. They may request to speak with past employees and ask about compliance with stated employment policies (including clear segregation between investment and operations functions, related party employment, background files, and internal actions against any employee). While staffing adequacy poses a challenge for smaller and newer funds, it is an essential element for investment protection, and many GPs find hiring qualified outside consultants offers assurance to potential LPs.

On-site ODD will involve multiple interviews with those in the middle- and back-offices, a review of policies and policy compliance, demonstration of critical systems (trading, reconciliation, order management, portfolio management/DSS, and others), access management, and key person dependencies or deficiencies of proprietary systems. GPs who have invested in conducting an internal review of their operations are well positioned to meet this scrutiny, and these reviews also prepare the operations team to respond to LP queries during due diligence.

Access to assets (cash, securities, brokerage, lines of credit, etc.) is an important part of ODD, especially after past instances of fraud and self-dealing have left LPs without adequate recourse. Prime brokerages, administrators, auditors, and banks are familiar with these confirmation requests, but the GP should document the entire cash movement process and make it available to LPs when requested. Establishing adequate access and authorization controls and providing a robust process on who is able to establish or change access for banks, prime brokers, and custodians is a must for all GPs.

Astute LPs look at the size of the investments to see if they match up with what is in the investment documents and analyze whether the size of investment is warranted by the nature and promise of the opportunity. GPs will do well to proactively analyze their investments and be intimately familiar with the data, process, history, investment thesis, and outcome. Familiarity with the portfolio and past investments provides investors with confidence at a time when they look to identify problems.

Most LPs view strategy drift as a real concern. A drift makes it very difficult for LPs to manage their own portfolio allocation and control risk exposure. The reason for investing in a GP is to tap their experience and expertise in a certain realm and with confidence in the strategies they are implementing. This may not be possible when the GP drifts away from the tried-and-true process, opening up the portfolio to risks of underperformance. GPs should be prepared to present their rationale if that drift was due to changing circumstances—and highlight skills they were able to leverage to mitigate transition risks and dispose the fund to a favorable performance.

Reference and Background Checks

Given the fund’s autonomy, limited regulatory oversight, and potential for severe loss or fraud, the quality and character of the team are of paramount importance. Positive background and reference checks are necessary for any investment. GPs should add to this process by conducting background checks on all senior personnel prior to each fundraise for private equity funds, and on a regular basis for hedge funds. Any issues should be flagged and addressed immediately; these could include unforeseen or long forgotten problems that crop up in due diligence. It is better to address any reference issues proactively, with your side of the story.

Common checks and references conducted by investors during due diligence include:

• Background check for partners/CEO/COO/CCO/IR personnel (including lawsuits, criminal or civil actions, personal finances, education or professional credentials and experience verification)

• References from previous and current LPs

• References from senior leadership of portfolio companies (past and present)

• Discussions with interested investors who did not commit capital

• References from service providers and professional acquaintances

• Background checks for unknown service providers such as auditors and fund administrators

• Interviews with past employees

After reference checks and office visits are completed, there may be additional meetings, calls, or email communication necessary prior to deciding whether to invest with a manager. A courtesy call from an LP, even if the decision is unfavorable to the GP, is customary to continue an ongoing relationship after completing a comprehensive due diligence process. If there is no follow-up from an LP within a reasonable time, GPs may benefit from proactively seeking a response without rushing them or appearing too eager.

INVESTORS: PREPARING FOR DUE DILIGENCE

During due diligence, an investor’s primary goal is to seek evidence and corroborate positive assessments of the team and strategy that initially got them interested in allocating to the fund. At the same time, they seek to uncover any red flags to help prevent embarrassment, loss of capital, fraud, or professional harm. LP representatives would want to gather enough information and evidence for their investment committee or senior managers and supervisors.

Investors want to ensure the strategy they were interested in is actually the strategy that is being executed; there are no discrepancies between what is expected and what is being delivered. They seek to uncover any deficiencies in strategy, implementation, or execution, not just with the investment process but also in the fund and firm operations and management.

They also want to ensure compliance with all regulations, norms, and policies as laid out in the fund documents. This is the right time to identify risks investors are not getting paid to undertake, including succession issues, inadequate operational infrastructure, lax regulatory compliance, and inadequate fraud prevention.

The process will be more efficient, productive, and meet the goals of the LP and fund manager only if both spend adequate time preparing for it. Even when due diligence is exploratory, it is an opportunity for the GP to re-emphasize messages, provide evidence to back up claims in the pitch, and convert an LP’s interest to an investment. Some GPs do not put in the requisite effort when they know an LP is conducting exploratory due diligence, but this is a serious mistake and a lost opportunity to forge a long-term partnership with LPs. Exploratory due diligence is a confirmation of LP interest in the fund. One critical issue LPs should pay more attention to is the long list of exceptions that the GP has made in agreements—such as restricting redemptions, in-kind redemptions, fees, and placing other obstacles to investor liquidity in hedge funds or setting a low bar for extensions and changes to the LPA while adding a high bar for manager removal in private equity funds.

Sometimes, an LP might deem it necessary to seek written responses from GPs to critical questions instead of raising them during a meeting. By allowing GPs adequate time to respond, LPs can ensure their answer is complete, accurate, and documented as compared to impromptu responses during a meeting. GPs might also want to avoid responding immediately to questions for which they do not have a complete or accurate answer.

Most successful LPs do not rely solely on the data shared by the GP, but also on their judgment and intuition honed over time through experience and picking up clues. This may involve reference checks and cross-references that go beyond the list provided by prospective GPs. In one instance, Hemali had provided an LP 10 references for a GP; the LP went on to conduct more than 60 reference checks through its own network. Whenever possible, LPs seek feedback from other investors who walked away after due diligence. Most larger institutions engage outside investigators and conduct background checks on key individuals. Even smaller LPs can find a lot about the GP and key personnel by conducting an online and social media search.

MANAGERS: PREPARING FOR DUE DILIGENCE

The most important things a GP can do is to ensure consistency in messaging, provide evidence, and demonstrate actual implementation. There should not be incongruity or inconsistency, even if it is tangential, for a smooth due diligence. GPs need to check through their documents thoroughly to ensure data is consistent and accurate before they are presented to investors. Even if a GP is willing to correct inconsistencies, it reflects poorly on the quality of output from the manager and will raise questions about attention to detail. LPs will rightly doubt the GP’s ability to focus on complex investment details when they are unable to do so in an easily reviewable document.

GPs should set up internal DDQ review processes before any information is shared with LPs. This means there should be a dedicated group of individuals, or a team, within the organization with adequate seniority, experience, knowledge, and responsibility to thoroughly review all information and data within DDQ documents and other marketing and fund documents for consistency and accuracy. It is equally important to have documents vetted by the fund’s counsel for regulatory and legal compliance before external dissemination.

A good practice is to ensure the DDQ is factual, without being overly stylistic or verbose, and is focused on answering relevant questions succinctly. The language should be acceptable in a professional communication. The intent of the document is to be transparent and should seek to gain the trust of the investor and strengthen the relationship. A coherent and transparent DDQ goes a long way in building investor confidence and establishes that the manager is willing to and capable of answering difficult questions candidly. It will also portray the team as a competent entity who can be trusted with investor capital.

Some LPs have their own DDQs and would seek to have that completed instead of accepting the GP’s standard DDQ, to ensure all questions and topics they care about are addressed and to ensure consistency in the way they consider multiple GPs. While the bespoke DDQ does help the LP, it adds work and complexity to the due diligence process and marketing workload. It would be helpful to have your responses to LPs’ questions, including those in a DDQ, cataloged and stored for future reference and dissemination. This creates a modular approach where you are picking and choosing from existing answers, instead of redoing work.

A comprehensive FAQ based on LPs’ questions should be maintained and updated. The FAQ is useful in onboarding new team members and effective for internal education and knowledge sharing. It is also a valuable tool in ensuring sensitive or difficult questions are consistently addressed by any team member. Many fund managers find the exercise of educating the entire investment team and relevant operating team members, and conducting mock interviews for team members, to be of tremendous value.

A scout’s motto applies here: be prepared. A junior staff member may be called on for an impromptu due diligence interview or might find themselves engaged in a conversation with an LP during an annual general meeting or investor conference. For marketing purposes, the staffer becomes the face of the firm at that moment and could affect the LP’s decision to invest or continue investing. Hemali has seen many LPs ask junior team members the same question, “What are the partners’ strengths and weaknesses?”

Most LPs provide an agenda for an on-site due diligence visit to improve productivity and efficiency of the process. If there is not an agenda, marketing teams may create one and submit it to the LP for prior approval. LPs usually drive the due diligence process; GPs will be better served by making it collaborative, stepping in if the process is not moving forward or in a direction unfavorable to an investment.

SECRETS OF EFFECTIVE DUE DILIGENCE

GPs with a robust strategy, dependable process, reliable infrastructure, strong team, and superior track record should view due diligence as an opportunity to uncover any inefficiencies or deficiencies that are not apparent, so they can strengthen themselves for the future. It is similar to receiving free consultation from their LPs on how to improve the strategy, process, people, and the fund in general. LPs who are conducting due diligence have already shown their willingness to put in time and resources in pursuit of an allocation to a GP’s fund. By being transparent and open to suggestions and recommendations from investors, the GP is showing a desire to listen and learn, which helps LPs overcome minor objections or concerns that may impede an investment.

Effective due diligence involves collecting information from multiple sources and cross-referencing them to ensure they fit together, not signaling inconsistencies or foreseeable red flags. LPs will not, and should not, take the DDQ as complete and accurate. In fact, nothing in the due diligence process is sacrosanct. They will approach it with skepticism that to some GPs might appear excessive. While it is important to have mutual respect and trust between the LP and GP, it is the LP’s responsibility to ensure suitability of the investment, a GP’s trustworthiness, and the likelihood that this strategy would succeed and fit their investment objectives. GPs should expect skepticism and react appropriately to questions that seem to cast aspersions on the information or the intent. A GP is unlikely to face the same treatment once the initial “kicking the tires” phase is completed and the LP makes a commitment to the fund.

“ONCE AND DONE” VERSUS COMPREHENSIVE PERIODIC DUE DILIGENCE

Some LPs understand the value of periodic due diligence to ensure material changes are discovered promptly, before it is too late to prevent a loss. This process does not need to be as involved as the original visit; it just needs to reverify assumptions and stress test factors critical to the success of the fund. Periodic due diligence confirms compliance with regulations and with stated processes for investment research, execution, and risk management. While it is additional work for a GP who believes heightened scrutiny is unnecessary since processes and philosophy remain unchanged, this exercise builds LP confidence and promotes a stronger relationship. Both can work out a schedule that will have a minimal impact on the team’s investment activities and operations—while providing value to both parties in the long run.

Experienced LPs typically ask for all communication from a GP, including investor letters and news announcements from the past few years. GPs should have due diligence packets ready to share with investors, including relevant investor presentations, memos, and newsletters. This packet will help set baseline expectations of what kind of communication transparency LPs should expect, and chronicle the evolution of the GP’s thoughts and reactions to market conditions over time. Following up an LP’s query must be timely; there is simply no excuse for delays.

When it comes to information sharing, LPs in any fund do not like disparate treatment, despite larger LPs pushing for more transparency and involvement. While LPs understand there will be preferential treatment of larger clients and seed investors, they will only accept it if that preferential treatment does not infringe on the rights or performance of their own investment. Most LPs will not object to the GP cutting fees or charging a lower carry that does not impact other LPs in the fund, to attract desirable LPs. However, even the appearance of impropriety in sharing of information with the fund’s LPs would be viewed with disdain and can harm the GP’s ability to market the fund.

GPs with teams in multiple locations should expect to be quizzed about their functioning and value addition. While in theory, localized teams should provide an investment edge, LPs could be concerned about loss of efficiency and performance if the GP and team are unable to function effectively due to distance and dearth of effective supervision. LPs like to understand the levels of autonomy and process controls, to avoid situations like rogue trader Nick Leeson, who engaged in fraudulent derivative trades due to insufficient supervision and brought down Barings Bank in 1995. Recently, the pandemic has alleviated some of these LP concerns around remote and virtual work.

One creative solution to the problem of dealing with each LP doing their IDD/ODD at their own times—which results in duplication of work for the GP and drains on essential investment and operational resources needed for the functioning of the firm—is to conduct group due diligence. Potential LPs are invited to conduct due diligence on the GP at the same time, thereby crunching timelines and streamlining the process. One GP was able to complete a multibillion-dollar raise in excess of $5 billion within a short fundraising timeline of a few months by using group due diligence. LPs will also benefit from listening to and learning from the questions, concerns, and insights of other investors. At this time only in-demand GPs are able to exercise this approach.

AVOIDING COMMON MISSTEPS IN DUE DILIGENCE

It can be disheartening to see LPs rely on a boilerplate template for a process as critical as due diligence. Trying to force fit a predetermined process and questionnaire on a complex investment decision reduces the value of discovering uncommon but foreseeable issues that could determine the outcome of the investment during the investment horizon. In addition, overreliance on a fund’s track record during due diligence, or at any time during the investment decision, can be highly misleading. As every investment disclosure rightly states, “past performance is not an indicator of future results.” LPs should take that disclosure at face value—it is possible that parameters underlying such performance, including AUM, market conditions, and competition for similar deals, may have changed.

Analyzing a track record will inform an LP’s judgment about the likelihood and magnitude of replicating results in the future. LPs are also likely to develop a better understanding of the strategy and decide for themselves if a GP and fund is suitable for the investor’s portfolio. GPs need to make it easy for LPs to analyze their results. This will help avoid accumulating LPs who will face buyer’s remorse and depart at the most inopportune time, or who will impact re-up rates as your fund and strategy is no longer appropriate for them. As a bonus, the sooner LPs decide on unsuitability, the better it is for the GP. They avoid spending time on prospects who are unlikely to commit capital, so they can use their time and resources for those who are more likely to do so.

Many LPs and alternative investment professionals fail to fully comprehend business continuity risks, including key person risk, succession risk, fund termination, and capital return issues. Additionally, for new fund managers, they need to have financial backing to continue operations until they can raise capital and achieve breakeven. That should be part of every due diligence; though it is a rare occurrence, this low probability event has a high impact.

LPs will not allocate capital after a due diligence exercise unless the GP exhibits a comprehensive understanding of the strategy, the team is found to be capable and trustworthy, the infrastructure is robust, and risks are appropriate for the expected returns. It is incumbent on both the GP and the LP to make a sincere effort to understand each other and be completely transparent with information, views, and observations.

GPs should seek feedback from LPs who decide not to commit capital to the fund. By showing sincerity without engaging in egotistic debates, GPs can benefit from learning about the concerns of the LP and attempt to mitigate them wherever possible. The willingness to engage even after the investment fails to materialize enables a GP to build an ongoing and positive engagement with an LP for future allocation and cultivate a positive reference.

CONCLUSION

One effective risk mitigation tool an investor has at their disposal in alternatives is conducting adequate investment and ODD. While some investors adhere to a purely checklist-driven due diligence that fails to uncover hidden issues, astute investors understand due diligence can mitigate investment risks and help foster greater learning about the firm and team. Many managers should change their perception on due diligence as a necessary evil to a productive and constructive examination that can assist them in identifying potential uncompensated risks in operations, strategy, and implementation. In addition, thoughtful management of the due diligence process can limit impact on investment resources. Creative solutions, such as group due diligence, are gaining acceptance from LPs. Despite what form due diligence takes, the process must always be viewed as transparent and thorough.