Chapter three

How to say what you really want

| What you’ll learn in this chapter: | This will help you to be more confident in any work situation, especially: |

|

|

Do you ever come away from a meeting annoyed with yourself because you didn’t get your point across the way you wanted? Or perhaps you regret the things you meant to say but didn’t? Then there are questions still unanswered and decisions still unmade. If you feel like this more often than you would like, a good way to make a real difference is to be more ‘assertive’. And by that I definitely don’t mean ‘aggressive’. This is a common misconception. Assertiveness is absolutely not about being self-centred or aggressive. Many people still think it is, but it is not so. Assertiveness is about being firm but fair, quietly confident and having respect for yourself and for others. It’s about clear and direct communication, and knowing how and when to say ‘no’.

How assertive are you at work?

Take a moment to think about assertiveness and you. How much of the time do you feel you succeed in communicating clearly, directly and confidently? Here is a short questionnaire that will assess your level of assertiveness at work.

What to do

Rate whether you agree or disagree with each of these statements and enter your ratings in your journal, in a column, using the scale below. Base your answers on how you are most days, in typical working situations. Don’t think too long or deeply about your answer. Your first reaction is likely to be the most accurate.

1 = completely agree

3 = agree somewhat

5 = neither agree nor disagree

7 = disagree somewhat

10 = completely disagree

When you’ve finished, add up your score. Write this in your journal.

What does your score mean?

- Check out how assertive you are from this scale:

- 86-100 almost always assertive

- 61-85 assertive much of the time

- 26-60 assertive some of the time

- 10-25 hardly ever or never assertive

- Find out even more about yourself:

- All of the statements were weighted in the same direction, so those on which you scored 1 show up the areas that you are the least likely to be dealing with assertively.

- If you’ve given any statements a score of 10, you are probably behaving assertively in these situations.

So what is assertiveness?

Can you think of a colleague who shouts, pressurises and throws their weight around? And do you know someone who is the opposite: very quiet, rarely draws attention to themselves, does what everyone else wants all the time, apologises a lot and hardly ever expresses an opinion? If you think of these as the two extremes, then ‘assertiveness’, and an assertive person, will sit halfway between these two.

You can’t fail to notice the domineering, noisy, aggressive person and you are likely to be aware of the passive, apologetic person, too. But the assertive person is often less noticeable. They go about their business in a way that gets results, but doesn’t draw attention, upset others, or make a fuss. How do they do this? The strength of assertiveness is its core idea that everyone has the same rights and that we should have respect for ourselves and for each other. And it’s this attitude, translated into your everyday dealings with colleagues, the public and clients, that has this effect.

Despite having been around for a long time, assertiveness is still often confused with aggression (as I flagged up earlier). But assertiveness is not about being aggressive, stern, severe, harsh, or all the other similar behaviours it can be wrongly mistaken for. What it is about is being able to express your views and needs calmly and effectively and (here is the big difference) in a way that respects both you and the other person involved. So mutual respect is paramount.

What is different about assertiveness is that it’s not about special behaviour, or clever words and tactics. What it is about is your attitude, how you see the world and the other people in it. If you can get that right, the rest will follow naturally. Assertiveness is simply the ability to deal with others in a calm, confident, respectful and effective way, whilst remembering that you have needs and rights, too. The persistence of the confusion between assertiveness and aggression comes about because of a commonly held misconception that the best way to have a view or suggestion heard is to speak loudly and forcefully.

Six key ways to be more assertive at work

Assertiveness is not what you do, it’s who you are!

Shakti Gawain, American bestselling author, b. 1948

This chapter will provide constructive suggestions and tips on how you can effect a major impact on your assertiveness through fairly straightforward means. Begin by aiming to be more assertive, more of the time than you are right now, and in the situations you can tackle most easily. You can tackle the more delicate situations, such as that awkward team member, or your line manager, when you feel ready. So what exactly is assertive behaviour? This is sometimes difficult to pin down but, bearing in mind it’s based on attitude, here are some pointers.

Six key ways to be more assertive at work:

- Be aware of your rights as a person and as a member of staff.

- Know your own needs.

- Have genuine respect for yourself.

- Have genuine respect for others.

- Be clear, open and direct with others.

- Be able to compromise.

Sounds simple and obvious put like that, doesn’t it? But all this can be easy to say, yet more difficult to achieve in the real world. It can be especially difficult if you have past experiences that have given your self-confidence a knock. Here are some examples:

- Previous criticism from a manager, colleague, your team, a trainer or teacher.

- Overly critical partner, parents or siblings.

- Your cultural or social background.

- Unpleasant previous experience when expressing your point of view.

Chill time

String puppet

- Take in a really deep breath, fill your lungs, hold it for a second or two, then let it go with a sigh of relief, dropping your shoulders and allowing all your muscles to relax, just like a puppet whose strings have been cut.

- Repeat (once only).

Four non-assertive ways people behave

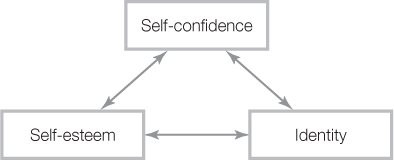

Assertiveness or, to be more precise, the lack of it, has far-reaching effects. It has a major impact on your dealings with the great diversity of people you interact with every day and, in turn, this will have significant consequences for your confidence, identity and self-esteem.

Here are four ways of behaving that are not assertive:

- Aggressive. Angry, rude, noisy, verbally abusive, threatening, domineering, violent, in your face, competitive, using ridicule, dogmatic, insisting on having own way, winning, talking over other people, not listening to colleagues, insisting on being right …

- Over-confident or arrogant (minor aggression). Nothing is a problem, loud, knowing best, full of ideas, interrupting colleagues all the time, knowing everything, one-upmanship, knowing everyone …

- Manipulative (or indirect aggression). Getting your own way by making colleagues feel guilty or by childish behaviour, plotting, sulking, sarcasm or put-downs …

- Passive. Dropping hints, making excuses, being unable to say ‘no’, the dogsbody, difficulty making decisions, the doormat, a push-over, being unable to say what they want, apologising all the time, putting other colleagues or clients first all the time …

KEY POINT

What does ‘passive-aggressive’ mean?

People often use the term ‘passive-aggressive’ in everyday conversation to describe behaviour such as sulking, put-downs or sarcastic behaviour, when this is used to get what you want or to criticise someone. But there is a personality disorder called ‘passive-aggressive personality disorder’, which can be serious and require treatment, so I feel it’s better to stick with the terms ‘indirect aggression’ or ‘manipulative behaviour’ when describing that kind of everyday behaviour.

Let’s pretend

If you’re presenting yourself with confidence, you can pull off pretty much anything.

Katy Perry, American singer-songwriter, b. 1984

So, if you want to be more assertive, where is the best place to start? Change your attitude? Learn how to deal with typical scenarios? Memorise phrases and responses to use? Actually, no. The easiest place to start is with the impression you give with your body and physical behaviour. So, before we go on to think more about attitudes, and about the sort of things assertive people say, let’s take time to gain a better understanding of the silent language that speaks volumes about us in the blink of an eye - our body language.

The good thing is, you don’t actually have to be confident to look confident. The acting profession pretends to be something they’re not every day - and, alright, an Oscar or BAFTA may be beyond your abilities, but just looking confident is not too difficult. You can be like an actor and you can take on the body language of a confident person. You can practise this when no one’s about, until you get a feel for it. A couple of practices, like the previous activity, and you’re good to go. A bit more practice, and it will almost feel real, not pretend, and you won’t even need to think about it. The best of it is, it’s a win-win situation. Because if you stand and walk confidently, you will actually feel and be more confident. People will immediately react to you in a more attentive and interested way, reinforcing your confidence, and so on. The next section will tell you how to do this (and there’s more about body language in Chapters 4 and 5).

IN THE ZONE

Be active

Let your hair down whenever you can. Join a drama group or take up bowling, yoga, tai chi, archery, dancing, kick-boxing or singing, anything you enjoy that involves using your physicality or your voice in a positive outgoing way.

How to walk the walk at work

- Aim for an open and relaxed posture, making good eye contact, and preferably with little or nothing in your hands. Smile if it’s appropriate (not too much if you’re a woman, as men can mistake this for sexual interest). Open posture means comfortably upright, shoulders back, head up, with no barriers formed by your hands or arms. Arms relaxed by your side or open hands resting easily on your lap when sitting convey quiet relaxed confidence. This overall picture is particularly helpful if you want to have more authority during meetings with colleagues or clients. Any kind of relaxation technique will make this posture easier to achieve, and you’ll find one in each chapter. So make sure to practise these, and choose those you like. They really do help.

- Make good eye contact, not too much so it is threatening to others, or too little, which appears nervous and uninterested.

- If seated, sit up well and lean forward a little towards others you might be talking to. This shows interest and encourages people. Slouching back into a chair or a corner can be comforting, but this will appear defensive and aloof or, worse still, apathetic to your colleagues or potential clients, and makes it harder to contribute to a discussion and put your point across.

- Don’t let your hands give the game away. Lack of confidence can make you form a fist with your hands or cling to a folder, briefcase or drink, like a comfort blanket. This will be noticed unconsciously or even consciously by those around you. Too many hand or arm gestures also distract and reduce your credibility. If your hands tend to tremble, use relaxation to ease tension - also, imagining your hands being very heavy and comfortably warm is very effective.

- Bring down barriers. Holding one or both arms across your body is a common way of reacting to nerves because you’re almost hiding behind them and giving yourself a comforting hug. But this creates a barrier, too, and can be interpreted by your manager or other team members as a lack of interest or, most commonly, as disagreement or disapproval.

- Pointing or staring at someone while you speak appears aggressive and threatening.

- Stop fiddling. Nerves and lack of confidence can make even the best of us fiddle with objects - pens, earrings, coins in your pocket, your hair, your paperwork.

- Try making a video-recording of yourself, or ask a trusted friend or colleague for their take on your body language.

In action

Keep a note of the really useful stuff

- Go right to the back of your journal and start a new page by writing a heading at the top, ‘Useful stuff’ (or any other title you prefer).

- As you work through the book, when you find a particularly helpful idea, thought or explanation, you can make a short note of this, along with the page it was on.

Do you know your rights?

One of the reasons for acting in a submissive or passive way and finding it difficult to assert yourself is not realising that it’s not just other people who have rights, but that you have them, too. It’s not legal rights or your rights as a member of staff I’m talking about here, just the everyday rights we all have as human beings. Lack of belief in these personal rights grows gradually if you’ve spent your childhood in circumstances that encourage a lack of belief in your rights. Your workplace environment, past or present, can do the same thing.

Here are some examples. Read them through slowly, one at a time, and make a note of any rights that you’re currently finding difficult to apply to yourself.

Your workplace bill of rights

I have the right to:

- my own point of view;

- have my own values;

- be treated as an equal;

- ask others to listen to me;

- express myself in my own way;

- make a mistake;

- say ‘no’;

- fail if I try;

- try again;

- be a leader;

- be treated with respect;

- ask for what I want.

Always remember:

- Each of us has all of these rights.

- We deserve these just like everyone else.

Talking the talk at work

Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice.

Steve Jobs, co-founder of Apple Inc., 1955-2011

With your body language sorted, and an awareness of your rights in place, you’re ready to talk the talk. Here are some of the basic assertiveness techniques that will be invaluable in helping you to do that. There is nothing particularly magical or clever about these. Other people use them all the time when communicating with you. Think of colleagues and managers you’ve found to be fair, respectful and approachable to you. They will be using assertive techniques like these without you even noticing.

Can’t say ‘no’ to colleagues?

One of the most common difficulties about being assertive is being able to say ‘no’ to people. And, although there will be many times at work when you can’t say no, depending on your job, there will be many occasions, day to day, when you will have a degree of choice. At the very least, there should be the possibility of reaching some kind of compromise, perhaps agreeing on more time for a piece of work. Think of it this way - if you don’t say ‘no’ when you should, you are putting the other person’s needs before yours. Is that really your intention? Even in the workplace, there are so many situations when a colleague’s needs will be of the same importance as yours and, on some occasions, yours could even be more important. Think about how often colleagues say ‘no’ to you. You just accept this and don’t get annoyed. So why should you worry that they will be upset if you behave the same way?

The real problem is that saying ‘yes’ all the time can easily become a habit, and changing your behaviour when it’s been established like this is really hard. Think about the people around you at work. Do you have a pretty good idea of what to expect from each of them? You probably have. Likewise, colleagues may learn that you tend not to say ‘no’, so you’re likely to attract more requests than you can handle. So, constantly saying ‘yes’ when you want to say ‘no’ to requests at work, leads to overload because you’ll take on more than you can cope with, or is your fair share. This leads to stress, frustration, ill-feeling, conflict and mistakes and all this entails.

So saying ‘no’ when you want to is an important skill to crack. This is not about being selfish. There will be times when you decide that you want to say ‘yes’, even though this might be inconvenient for you. Remember assertiveness means respecting your needs and rights, as well as those of others, and compromising when necessary.

DON’T FORGET

One change at a time

As with everything in this book, take things steadily and don’t try everything at once. This is especially true of assertiveness. Try one new skill at a time and practise it till you become fairly good at it. Be ready for the odd setback along the way. You’re learning new skills and there are always ups and downs when learning something new.

Different levels of ‘no’

Many people find it hard to say no because they think there is just the one way of doing it, the straight ‘no’. And this can feel like being rude and aggressive. That isn’t usually the kind of impression you want to give in your workplace. You are aiming for good communication, good rapport. But you still have to be able to refuse some requests, to safeguard your own health and well-being. This means being able to say no, but in a way that expresses respect for the other person’s needs. But there are different levels of saying no, suited to different situations. Here are the three main options:

- A straight ‘no’ is the most uncompromising and is rarely suited to the workplace. It is most likely to be used when your rights are being abused in some way. You can add a loud and firm, ‘Didn’t you hear me, I said “no”’, in some cases at work or elsewhere.

- Asking for information or giving a ‘rain check no’ opens up a discussion, but still leaves a ‘no’ of some kind on the table as an option.

- A reflective ‘no’ is the most sensitive, as you show you’ve listened to the other person.

I’ll explain exactly what these are in the next section, but which one you choose will depend on the situation, how you feel about it and who is doing the asking - it could be a mentor, your line manager, another team member or a colleague you really want to help. But, as mentioned already, don’t attempt too many changes in your behaviour all at once - this is especially true for saying ‘no’, however it is done, because this may come as an unexpected shock to colleagues who don’t expect the leopard to suddenly change its spots. Starting small, practising and building up gradually, works best.

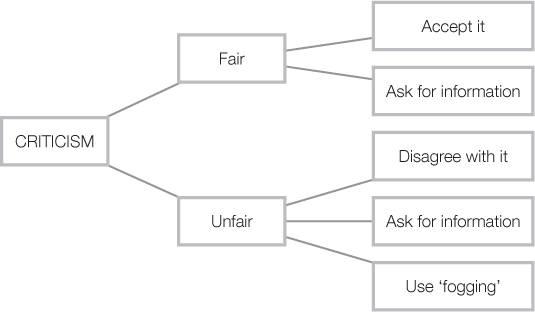

Handling direct criticism

Criticism can be one of the hardest things to cope with in an assertive way. It can hurt your feelings and dent your self-esteem. Sometimes, you can be so fazed by it, that you’ll even accept unfair criticism and take it to heart, too. The thing is, there is criticism that is realistic and fair comment and criticism that is unfair and unfounded. And criticism can be made sensitively, and insensitively, in private or in public. You’re likely to find yourself at the wrong end of the more upsetting of these at some point in the workplace. That’s because not everyone knows how to be assertive, and doesn’t always remember to give respect to everyone. And, in some cases, it can be the accepted way of doing things. Let’s look at some assertive ways to respond to fair and unfair criticism.

How to react to a criticism that’s fair

This can be a difficult one to do but, if you can remember from Chapter 2 that absolutely everyone makes mistakes and that there’s always room for improvement, it becomes easier to do. Look out for colleagues doing it. It happens all the time. Here are two ways to handle it.

1. Accept it

The simplest response is to accept the criticism without expressing guilt, giving excuses or making apologies. We all make mistakes and the best thing is to hold your hand up, correct the situation, learn from it and move on. It has been said that the person who never made a mistake never did anything.

Your line manager: ‘You didn’t make a very good job of that.’

You: ‘No, I didn’t did I? I’ll have another go at it.’

2. Ask for information

Another way of coping is to immediately accept the criticism but, in the same breath, go on to ask for more information about it, from the person doing the criticising. Ask a question, any question, about what they’ve said. It won’t matter what you actually ask about, you’ll still dilute the criticism and, at the same time, appear confident and still in control.

Your team leader: ‘You didn’t facilitate that meeting very well.’

You: ‘No, it wasn’t too good, was it? Was it the first part, or was it later on that was the problem?’

What if a criticism is unfair?

Criticism is often unfair. This happens to us all, and for many different reasons, and it can really hurt even more than a fair criticism. Think back to Chapter 2 and the unhelpful belief that ‘Life should be fair’ - that’s why it hurts more. So, remember that life isn’t fair to any of us, but here are three ways to deal with unfair criticism, which may make it hurt a bit less:

1. Disagree with it

Make sure you stay calm and friendly. Think for a few moments, then warmly disagree with the criticism. Here’s an example:

Your colleague: ‘You’re always late for these meetings.’

You: ‘No, I’m not always late … I may have been late once or twice, but I’m definitely not always late.’

2. Ask for information

You can warmly ask questions and for more information with enthusiasm, until the criticiser wishes he hadn’t raised the subject!

3. Use ‘fogging’

Fog the issue, making the picture very unclear, by neither agreeing nor disagreeing, giving the criticiser nothing substantial to get a hold on, so that the criticism doesn’t hit home. This makes it seem as though the criticism is accepted, but is actually having little impact. This will also put the criticiser off criticising you unfairly again. A bit of practice, and you can become quite skilled at fogging. Including words like possibly, maybe, perhaps, or probably fogs any issue. Or, try responding with phrases like:

- ‘Perhaps you are right, these things can happen …’

- ‘It’s hard to say for sure …’

- ‘You could be right …’

- ‘There could be some truth in that …’

What about those subtle ‘put-downs’?

Sometimes colleagues, managers or team leaders can be openly critical, and that can be hard enough to cope with. But, now and then, you can find yourself at the receiving end of a ‘put-down’. This is a more manipulative and veiled form of criticism. A kind of indirect aggression. Sometimes people don’t even realise that they are being insulting and hurtful. You know the kind of thing. Here are some examples:

- ‘Don’t worry, that will do like that. I’ll take care of it now.’

- ‘Are you sure that’s the best way to do that?’

- ‘Haven’t you finished that report yet?’

These kinds of comments are usually said in a friendly voice, and maybe even with a bit of a smile, but they leave you with a vague feeling that you’ve been criticised, but you’re not quite sure. A ‘smiling assassin’, if you like. So you’re left not really knowing what to say, and the moment passes. Or maybe you react angrily because you feel instinctively that you’re being attacked in some way. But, if you do, the perpetrator just looks bemused and says something like:

- ‘What? What did I say?’

- ‘I didn’t mean it that way… you’re over-reacting.’

- ‘You’re … imagining things … too sensitive … you have an attitude problem.’

Put-downs like these can make you feel small and can undermine your self-confidence. They can become a habit if you let them slip by, and they’re difficult to pin down as harassment or bullying. So how do you deal with them?

The foremost tactic is to let the person know in a calm, dispassionate and non-threatening way that you are fully aware of what they’ve actually implied. Once faced with this reaction, most people will then back down and won’t put you down like this again. Colleagues do this to you only if you let them. As ever, practise doing this before trying it for real and only use it if you’re sure there will be no unwanted repercussions.

Here are two ways to respond to a put-down:

- You can acknowledge the criticism, openly, but fairly dispassionately, and follow this up with a positive comment, as in the response to number 1 in the following table.

- You can reply to an unclear statement with another one - by ‘fogging’ the issue. So vaguely acknowledge the implied criticism as in numbers 2 and 3. ‘Fogging’ of this kind can be quite disarming, and disappoints the perpetrator, who then doesn’t know if his put-down has hit home or not.

Here are examples of how to respond to the three put-downs mentioned earlier.

| Put-down | Your response | |

| 1. | ‘Don’t worry, that will do like that. I’ll take care of it now.’ | ‘Yes, you’re right. It wasn’t up to my usual standard, but I was pushed for time because my planning meeting with my new major client over-ran.’ |

| 2. | ‘Are you sure that’s the best way to do that?’ | ‘Yes, I suppose your way of doing it would probably have been better, but Jerry asked me to do it this way today.’ |

| 3. | ‘Haven’t you finished that report yet?’ | ‘Yes, maybe it has taken me a bit longer than usual to finish it. But I’m not sure.’ |

What about criticising others?

You are likely to be involved in giving criticism to others at some point in your career. Most of us exist for the majority of our working life in a sandwich between those who criticise us and those we criticise. Either process can be a source of problems, as both can raise negative and unpleasant feelings if not carried out assertively. Here are some tips:

- Praise the positive, too, on a regular basis. That way criticism will become a lesser part of the feedback you give, and more in proportion. It’s common to feel that all you receive is criticism in today’s working environment. Give criticism as part of more general and positive feedback, not in isolation, and it will just be a routine event for all concerned.

- ‘You’ve done a great job. On time, and ticks the boxes. Well done. To make it even better here’s a quick suggestion.’

- ‘You’ve done a great job. On time, and ticks the boxes. Well done. To make it even better here’s a quick suggestion.’

- The right to criticise carries responsibilities. You may be a line manager, with the right to criticise, but this should only ever be used to improve performance, and not for its own sake. Your responsibility is to criticise without being aggressive, attacking or belittling the person. Your responsibility is to criticise assertively, with mutual respect.

- Criticise the specific behaviour, not the person or their personality.

- Be considerate - imagine yourself in the person’s shoes. Give criticism in private. Remember, everybody makes mistakes and none of us is perfect.

- Keep the big picture in mind. Be aware of the circumstances surrounding the person, and take this into account. See the situation as a whole, and keep the criticism in proportion.

- Criticism shouldn’t be a first resort. Sometimes, just asking someone how the relevant task is going can turn things into a discussion, or even a request for advice or help. This can make criticism unnecessary.

- Be sure of your facts before criticising someone.

- Only criticise when you are calm. If you are angry or upset, wait until you’ve cooled off before giving criticism.

- Don’t waffle and wander round the subject. Come to the point.

- Have confidence in what you are saying. If you aren’t sure of yourself or your ground and appear nervy or embarrassed, it makes the whole thing seem bigger and more of an issue to the person being criticised. This rebounds on how you feel and can escalate a minor error into a major catastrophe for you both.

- Four typical steps:

- Your step 1: ‘Donna, can we meet this week sometime? I’d like to talk about how your training sessions are going.’

- Your step 2: ‘I’ve noticed that some of the participant evaluations have not been up to your usual high standard - have you noticed this? Why do you think this might be?’

- Your step 3: ‘What ideas do you have about making changes to improve things?’

- Your step 4: ‘So will we agree that before the next session we can …’

When disagreement spills over into conflict

In today’s world of work and business, there is inevitably going to be conflict, and this is often seen as damaging. There is certainly evidence to support that view, especially if it has gone beyond what you might describe as everyday workplace conflict and has progressed into a situation moving towards grievance and disciplinary action.

But before that level of conflict has been reached, something positive can often come from it, provided it is dealt with carefully. Here are just a few positive outcomes, which can come from conflict, meaning that avoidance it is not always the best strategy:

- Increased knowledge and understanding of a situation.

- Deeper insight into people.

- Stronger mutual respect.

- Improved communication and ability to work together.

- More knowledgeable about yourself.

There are too many possible scenarios to list here, but the way to approach any conflict is very similar, whether you are involved in it yourself or you have the responsibility of dealing with the situation, and whether two or more people are involved.

Having your say in a conflicting situation

Your aims

- Reach an agreement, which has not been forced on anyone, approved by all involved, even if this takes more than one session. Focus on solutions, not on problems.

- The best way to do this is probably the win-win approach: aiming for all sides to leave with their head held high, and with a deeper understanding of the other’s position.

- No matter how difficult it gets, stay objective, and don’t get personal.

General guidelines for dealing with conflict

- Create some space. Start by introducing a break and creating enough space for tempers to calm and negative emotions to disperse. During this break, make it possible for those in disagreement to have the opportunity to understand what the problem is. Then clear the way to move forward and resolve things amicably.

- Talk about it. Only when people have reached an awareness of what the problem is, bring those concerned together to talk about it. Think positively from the start, be calm, use positive language and, when needed, the assertiveness skills from earlier in this chapter.

- Ground rules. The first thing to do at the meeting is to discuss and agree some ground rules such as:

- Everyone treats each other with respect.

- Anyone who becomes angry or aggressive takes time out to calm down.

- Stick to the issue in hand.

- Don’t bring up previous history or other issues.

- Keep personalities out of the discussion.

- Separate the problem from the people involved.

- Listen carefully. Try to look behind the words and behaviour to allow yourself to see the other person’s needs and interests - these will help to explain why there is a problem.

- Objective third party. Sometimes an objective or knowledgeable third party, brought in with everyone’s agreement to give information, or act as a neutral arbiter, can shorten the whole process.

- Hear each other out. Make sure each side listens to what the other side is saying, without interrupting; if necessary, give each a set time to speak without interruptions.

- Break to cool off if needed. If at any point, things are not working, and tempers are rising again, be prepared to call a halt, and set another time to talk about things when people have had time to cool off.

- Summarise where you are. When the time seems right, summarise and restate the different points of view.

- Think about solutions. Now invite both (or more) sides to offer possible solutions and come to some agreement.

In short

- Being assertive is a key part of saying what you want to say.

- Assertiveness is clear and direct communication coming from a position of respect for the other person as well as for yourself.

- Assertiveness lies midway between passive behaviour and aggressive behaviour.

- Manipulative behaviour is a form of indirect aggression.

- Ways to be more assertive include knowing what you need or want, being able to say this clearly, saying ‘no’ when you want or need to and being prepared to compromise.

- It’s best to start small and practise with less important situations.

- Skills that are useful include: upright and open posture, steady warm voice, good eye contact, not being distracted from your point, reflection and fogging.

- It’s usually best to address conflict before it gets out of hand, by letting tempers cool, and then talking things through in an assertive and structured way.